Abstract

Background

The dexamethasone (DEX)-sparing strategy, which limits administration of DEX to day one, is reportedly non-inferior to conventional antiemetic regimens comprising multiple-day DEX. However, the usefulness of the DEX-sparing strategy in triplet antiemetic prophylaxis (neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist [NK1RA] + serotonin receptor antagonist [5HT3RA] + DEX) for carboplatin and moderate emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) has not been clarified.

Patients and Methods

We systematically reviewed randomized controlled trials that examined the efficacy of antiemetics for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with carboplatin and MEC. We conducted a network meta-analysis to compare the antiemesis efficacy of three-day DEX with NK1RA (3-DEX + NK1RA) and one-day DEX with NK1RA (1-DEX + NK1RA). The primary outcome was complete response during the delayed phase (CR-DP). The secondary outcome was no nausea during the delayed phase (NN-DP).

Results

Seventeen trials involving 4534 patients were included. The proportion who experienced CR-DP was 82.5% (95% credible interval [CI], 73.9-88.6) and 73.5% (95% CI, 62.8-80.9) among those who received 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two regimens. However, 3-DEX + NK1RA tended to be superior to 1-DEX + NK1RA, with an absolute risk difference of 9.0% (95% CI, −2.3 to 21.1) in CR-DP and 24.7% (95% CI: −14.9 to 54.6) in NN-DP. 3-DEX + NK1RA also tended to be superior to 1-DEX + NK1RA in patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy, for whom the absolute risk difference was 12.3% (95% CI, −3.2 to 30.7).

Conclusions

Care is needed when administering the DEX-sparing strategy in combination with NK1RA to patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Keywords: antiemetics, neurokinin, 1 receptor antagonists, dexamethasone, nausea, vomiting, antineoplastic agents, carboplatin, network meta, analysis

Minimizing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is important to improve patients’ quality of life and ensure they continue chemotherapy. This meta-analysis compared one-day and three-day dexamethasone in combination with NK1RA for preventing CINV associated with carboplatin and non-carboplatin moderate emetogenic chemotherapy.

Implications for Practice.

This study demonstrated that a three-day dose of dexamethasone (DEX) with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) was nonsignificantly superior to a one-day dose of DEX with NK1RA as prophylaxis for delayed-onset nausea and vomiting. The absolute risk difference in complete response during the delayed phase was 9.0% among patients who received moderate emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC), and 12.3% among patients who received carboplatin. Therefore, we propose that the majority of patients, with the exception of patients who should receive minimal DEX, such as those intolerant to corticosteroids, should receive DEX beyond day one of treatment when receiving non-carboplatin MEC or carboplatin.

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) often reduces quality of life, treatment adherence, treatment efficacy, and curability in patients receiving chemotherapy. It is important to minimize the incidence of CINV to improve patients’ quality of life and ensure they continue chemotherapy.

Although dexamethasone (DEX) is effective for suppressing CINV, short-term steroid use as antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy can cause steroid-induced adverse events such as elevated blood glucose levels,1 reduced bone mineral density,2 and other symptoms.3 Several studies and meta-analyses have shown that, as an antiemetic prophylaxis, the DEX-sparing strategy, which involves limiting administration of DEX to day one, in combination with palonosetron is non-inferior to multiple-day DEX.4-10 In terms of high emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC), a randomized phase III trial showed a one-day dose of DEX is non-inferior to a three-day dose of DEX in combination with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) and palonosetron in patients receiving anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide therapy. On the other hand, a one-day dose of DEX was indicated to be insufficient to control CINV in patients receiving cisplatin-containing regimen.11 Thus, global guidelines recommend continuous administration of DEX in the delayed phase (DP) for patients receiving cisplatin-containing chemotherapy.12-15

Recent guidelines classify carboplatin from a moderate emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) to HEC,12-15 and recommend that patients receiving carboplatin area under the curve ≥ 4 mg/mL/min be offered triplet antiemetic prophylaxis, which combines a NK1RA with a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist (5HT3RA) and DEX.12-15 For patients receiving carboplatin, American Society of Clinical Oncology and Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend combining a one-day DEX dose with NK1RA and 5HT3RA.14,15 However, the recently updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline recommends the DEX-sparing strategy be limited to patients with few specific risk factors for CINV or intolerance to corticosteroids.12 A recent trial by Iihara et al. showed that CINV associated with carboplatin occurs in the DP rather than the acute phase.16 A propensity score matching retrospective cohort study (N = 56) using data from a prospective observational study in clinical practice showed that a three-day dose of DEX was significantly superior to a one-day dose of DEX in triplet antiemetic prophylaxis for preventing nausea in patients receiving carboplatin.17

However, no randomized controlled trial (RCT) to date has examined the usefulness of combining DEX-sparing strategy with NK1RA in patients receiving carboplatin. For patients receiving non-carboplatin MEC, global guidelines recommend adding NK1RA to DEX and 5HT3RA as one antiemetic prophylaxis option,12,13 while the usefulness of combining the DEX-sparing strategy with NK1RA has not been established for these patients either. It is necessary to clarify the role of DEX in preventing delayed-onset CINV in triple antiemetic prophylaxis for patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Therefore, we conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare one-day and three-day DEX in combination with NK1RA for preventing CINV associated with carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Patients and Methods

Objectives

The present study aimed to compare one-day versus three-day DEX in combination with NK1RA and 5HT3RA for preventing CINV associated with carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC described in the most recent NCCN guideline.12 The present NMA was prospectively registered (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021256346) and was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Randomized (phase II or III) clinical trials were included if they were published in English. Trials of interest were those that compared the efficacy of globally available antiemetics in adult patients with cancer receiving carboplatin or non-carboplatin MEC. Trials that compared two of the following antiemetic strategies were included: (1) three-day DEX with NK1RA (3-DEX + NK1RA), (2) one-day DEX with NK1RA (1-DEX + NK1RA), (3) three-day DEX (3-DEX), and (4) one-day DEX (1-DEX). Studies that used drugs other than DEX, 5HT3RA, and NK1RA for antiemetic prophylaxis, such as olanzapine or metoclopramide, were excluded.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was complete response (CR; no emesis and no rescue medication) during the DP (24-120 h after chemotherapy initiation). The secondary outcome was no nausea during the DP (NN-DP). For the primary outcome, subgroup analysis was performed in patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy and those who received a three-day dose of first-generation 5HT3RA or single dose of palonosetron (long 5HT3RA). All outcome variables were extracted in the first planned chemotherapy cycle.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

We systematically searched for eligible RCTs published through May 15, 2021 using PubMed and Ovid-MEDLINE. We used a combination of the terms “chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting,” “moderately emetogenic chemotherapy,” “steroid-sparing,” “neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists,” “fosaprepitant,” “ezlopitant,” “netupitant,” “rolapitant,” and “aprepitant” to find relevant articles (see Supplementary Table S1 for details). An additional search through the reference lists of relevant reviews and meta-analyses was also conducted. Two reviewers (D.W. and H.I.) independently assessed the abstracts of all relevant studies to confirm their eligibility and extracted details from the included studies, including the study design, study population characteristics, inclusion criteria, outcome measures, chemotherapy regimen, and details of the antiemetic regimen. Decisions made by each of the two reviewers were compared, and any disagreement was resolved through consensus between the two reviewers.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers (D.W. and H.I.) independently assessed the risk of bias due to the randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported results, and other biases of the included studies (Supplementary Table S2) using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) by The Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.de). Any disagreement was resolved through consensus between the two reviewers.

Statistical Analysis

An arm-based NMA using Bayesian methods was conducted to compare multiple antiemetic strategies. NMA enables the direct comparison of treatments in individual trials and indirect comparison between trials simultaneously.18 In particular, an arm-based approach can be used estimate the population-averaged treatment-specific event rate. The proportions of CR-DP and NN-DP in each antiemetic strategy were aggregated using the nma.ab.bin function in the R package, pcnetmeta.19 The statistical heterogeneity in each treatment arm was evaluated using the I2 statistic with the metaprop function in the R package, meta. An I2 > 50% indicated statistically significant heterogeneity (Supplementary Table S3). A random effects model was used to consider heterogeneity, and the correlations between treatments were assumed to be different. Final estimation routines used 3 chains of 10 000 burn-in iterations, with 50 000 estimation iterations without thinning, resulting in 120 000 iterations for analysis. The results of NMA were estimated using posterior median with corresponding 95% credible intervals (CIs), which can be interpreted in the same manner as 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was indicated when the lower limit of one 95% CI exceeded the upper limit of the other 95% CI.

Results

Eligible Studies and Characteristics

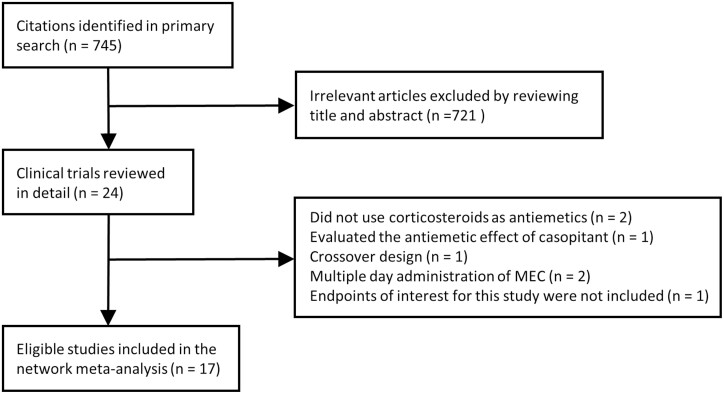

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection process. Among the 745 published papers on CINV identified by searching databases, we focused on 24 potentially relevant randomized control trials. We further excluded several trials because they did not use corticosteroids as an antiemetic prophylaxis (n = 2)20,21; used casopitant, which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, as an antiemetic prophylaxis (n = 1)22; used a crossover design and did not report the outcomes of the first chemotherapy (n = 1)23; examined chemotherapy including multiple day administration of MEC (n = 2)24,25; or did not examine the endpoints of interest for this study (n = 1).26 Ultimately, 17 trials were included in our analyses.5,27-42 One article43 was a post-hoc analysis of another eligible study38; the former was used for subgroup analyses.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all included trials. Eight trials compared 3-DEX + NK1RA and 3-DEX,27,30,31,33,34,36,39,40 five trials compared 1-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX,32,37,38,41,42 and four trials compared 3-DEX and 1-DEX,5,28,29,35 while no trials directly compared 3-DEX + NK1RA with 1-DEX + NK1RA (Supplementary Figure S1). Of the 4534 patients included this NMA, 11.0% (n = 499) received 3-DEX + NK1RA, 31.7% (n = 1438) received 1-DEX + NK1RA, 18.5% (n = 839) received 3-DEX, and 38.8% (n = 1758) received 1-DEX. The proportion of patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy was 49.6% (n = 2250). Among those administered NK1RAs, 57.5% (n = 1113) received aprepitant, 25.9% (n = 502) received fos-aprepitant, and 16.6% (n = 322) received rolapitant. Among those administered 5HT3RAs, 42.4% (n = 1923) received a first-generation 5HT3RA on day one only, 35.4% (n = 1603) received a first-generation 5HT3RA from day one to three, and 19.7% (n = 895) received palonosetron. The type of 5HT3RA administered to the remaining 2.5% (n = 113) was unclear.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and patient demographics of studies included in the network meta-analysis

| Study name | Major chemotherapy regimen | NK1RA | 5HT3RA | DEX | N (male/female) | Carboplatin-based regimen (%) | CR-DP | NN-DP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aridome_2016 | Oxaliplatin-based | APR | Any 5HT3RA | 3-day | 59 (34/25) | 0 | 47/59 | 38/59 |

| — | Any 5HT3RA | 3-day | 54 (30/24) | 0 | 43/54 | 37/54 | ||

| Celio_2011 | Carboplatin-based Oxaliplatin-based Irinotecan-based |

— | Palo | 3-day | 100 | 16 (16.0) | 76/100 | NA |

| — | Palo | 1-day | 111 | 21 (18.9) | 79/111 | NA | ||

| Furukawa_2015 | Carboplatin-based | — | Palo | 3-day | 39 (0/39) | 39 (100) | 30/39 | 25/39 |

| — | Palo | 1-day | 43 (0/43) | 43 (100) | 30/43 | 26/43 | ||

| Ito_2014 | Carboplatin-based | APR | First-generation 5HT3RA day 1 | 3-day | 67 (56/11) | 67 (100) | 54/66 | 35/66 |

| — | First-generation 5HT3RA day 1 | 3-day | 67 (54/13) | 67 (100) | 46/67 | 29/67 | ||

| Kaushal_2015 | Carboplatin-based | APR | Palo | 3-day | 30 (29/1) | 30 (100) | 25/30 | 23/30 |

| — | OND day 1-3 | 3-day | 30 (23/7) | 30 (100) | 16/30 | 13/30 | ||

| Kim_2017 | Carboplatin-based Oxaliplatin-based Irinotecan-based |

APR | OND day 1 | 1-day | 237 (129/108) | 156 (65.8) | 176/237 | NA |

| — | OND day 1-3 | 1-day | 243 (134/109) | 156 (64.2) | 173/243 | NA | ||

| Komatsu_2015 | Oxaliplatin-based Irinotecan-based |

— | Palo | 3-day | 154 (87/67) | 19 (12.3) | 100/154 | NA |

| — | Palo | 1-day | 151 (86/65) | 18 (11.9) | 101/151 | NA | ||

| Kusagaya_2015 | Carboplatin-based | APR | Palo | 3-day | 41 (29/12) | 41 (100) | 33/41 | NA |

| — | Palo | 3-day | 39 (28/11) | 39 (100) | 30/39 | NA | ||

| Maehara_2015 | Carboplatin-based | APR | GRA day 1 | 3-day | 11 (0/11) | 11 (100) | 11/11 | 10/11 |

| — | GRN day 1 | 3-day | 12 (0/12) | 12 (100) | 8/12 | 2/12 | ||

| Matsuura_2015 | Carboplatin-based | — | Palo | 3-day | 53 (0/53) | 53 (100) | 36/53 | NA |

| — | Palo | 1-day | 56 (0/56) | 56 (100) | 34/56 | NA | ||

| Nishimura_2015 | Oxaliplatin-based | APR | 5HT3RA day 1 | 3-day | 207 (126/81) | 0 | 159/187 | 124/187 |

| — | 5HT3RA day 1 | 3-day | 206 (126/80) | 0 | 138/183 | 113/183 | ||

| Rapoport_2010 | Carboplatin-based Irinotecan-based Oxaliplatin-based Other non-AC MEC |

APR | OND day 1 | 1-day | 226 | NAa | 172/226 | NA |

| — | OND day 1-3 | 1-day | 203 | NAa | 140/203 | NA | ||

| Schwartzberg_2015 | Carboplatin-based Irinotecan-based Oxaliplatin-based Other non-AC MEC |

ROL | GRN day 1-3 | 1-day | 322 | 191 (59.3) | 245/322 | NA |

| — | GRN day 1-3 | 1-day | 307 | 209 (68.1) | 196/307 | NA | ||

| Sugimori_2017 | Carboplatin-based | APR | Palo | 3-day | 39 (0/39) | 39 (100) | 38/39 | 27/39 |

| — | Palo | 3-day | 39 (0/39) | 39 (100) | 32/39 | 25/39 | ||

| Tanioka_2013 | Carboplatin-based | APR | GRN day 1 | 3-day | 45 (0/45) | 44 (97.8) | 28/45 | NA |

| — | GRN day 1 | 3-day | 46 (0/46) | 45 (97.8) | 24/46 | NA | ||

| Weinstein_2016 | Carboplatin-based Oxaliplatin-based |

FAPR | OND day 1 | 1-day | 502 (204/298) | 257 (51.2) | 396/502 | NA |

| — | OND day 1-3 | 1-day | 498 (205/293) | 256 (51.4) | 341/498 | NA | ||

| Yahata_2016 | Carboplatin-based | APR | First-generation 5HT3RA day 1 | 1-day | 155 (0/155) | 155 (100) | 96/151 | 61/151 |

| — | First-generation 5HT3RA day 1 | 1-day | 152 (0/152) | 152 (100) | 72/146 | 49/146 |

Data could not be extracted from among the other chemotherapy regimens.

Abbreviations: 5HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; APR, aprepitant; CR-DP, complete response during delayed phase; DEX, dexamethasone; FAPR, fos-aprepitant; GRN, granisetron; NA, not available; NK1RA, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist; NN-DP, no nausea during delayed phase; OND, ondansetron; Palo, palonosetron; ROL, rolapitant.

Proportion Experiencing CR-DP and NN-DP in Each Antiemetic Regimen

The proportion of patients who experienced CR-DP was 82.5% (95% CI, 73.9-88.6), 73.5% (95% CI, 62.8-80.9), 70.4% (95% CI: 63.3-76.3), and 65.5% (95% CI, 57.8-72.2) among those who received 3-DEX + NK1RA, 1-DEX + NK1RA, 3-DEX, and 1-DEX, respectively (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the proportion who experienced NN-DP was 67.9% (95% CI, 54.9-79.3), 42.8% (95% CI, 15.2-81.5), 51.6% (95% CI, 35.5-65.9%), and 35.4% (95% CI, 12.4-72.3) among patients who received 3-DEX + NK1RA, 1-DEX + NK1RA, 3-DEX, and 1-DEX, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients who experienced complete response during the delayed phase in each antiemetic regimen among the entire population.

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients who experienced no nausea during the delayed phase in each antiemetic regimen among the entire population.

Among patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy, the proportion who experienced CR-DP was 86.9% (95% CI, 75.5-93.3), 74.4% (95% CI, 57.8-85.2), 70.5% (95% CI, 59.3-79.3), and 61.6% (95% CI, 48.7-72.8) of those who received 3-DEX + NK1RA, 1-DEX + NK1RA, 3-DEX, and 1-DEX, respectively (Figure 4). Meanwhile, among patients who received long 5HT3RA, the proportion who experienced CR-DP was 86.9% (95% CI, 71.2-94.3), 75.1% (95% CI, 44.0-91.4), 71.0% (95% CI, 60.7-79.3), and 67.4% (95% CI, 59.9-74.0) of those who received 3-DEX + NK1RA, 1-DEX + NK1RA, 3-DEX, and 1-DEX, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients who achieved complete response during the delayed phase in each antiemetic regimen among those who received a carboplatin-based regimen.

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients who achieved complete response during the delayed phase in each antiemetic regimen among those treated with a three-day dose of first-generation 5HT3RA or single dose of palonosetron. 5HT3RA, 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist.

Pairwise Comparison of 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA

Figure 6 shows the results of a pairwise comparison of 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA in CR-DP, NN-DP, and CR-DP in patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy and in CR-DP in patients who received long 5HT3RA. While there were no significant differences in any outcome between 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA, 3-DEX + NK1RA tended to be superior to 1-DEX + NK1RA. The absolute risk difference between 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA was 9.0% (95% CI, −2.3 to 21.1), 24.7% (95% CI, −14.9 to 54.6), 12.3% (95% CI, −3.2 to 30.7), and 11.4% (95% CI, −10.1 to 42.4) in CR-DP, NN-DP, and CR-DP in patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy and in CR-DP in patients who received long 5HT3RA, respectively.

Figure 6.

Pairwise comparison of 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA. Absolute risk difference greater than 1 suggests that 3-DEX + NK1RA is more efficient than 1-DEX + NK1RA. 1-DEX + NK1RA, one-day dexamethasone with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist; 3-DEX + NK1RA, three-day dexamethasone with neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist.

Discussion

We performed a systematic review and NMA to indirectly compare the antiemetic effects of 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA in patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC. Although we found no statistically significant differences, 3-DEX + NK1RA showed a tendency toward being superior to 1-DEX + NK1RA, and the absolute risk difference between 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA was 9.0% and 24.7% in CR-DP and NN-DP, respectively. These results suggest that continuous administration of DEX beyond day one may increase the benefits of prophylaxis for delayed-onset CINV in patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Among patients who received carboplatin, we found that 3-DEX + NK1RA was nonsignificantly superior to 1-DEX + NK1RA in CR-DP, and that the absolute risk difference was 12.3%, which is clinically meaningful to the patient according to MASCC/ESMO.44 Tamura et al. reported that the CINV incidence and severity associated with cisplatin and MEC comprising mainly carboplatin and oxaliplatin peaked on days four to five.45 Iihara et al. reported that administration of carboplatin led to a high incidence of CINV that continued for more than seven days, with the severity peaking on days four to five with or without aprepitant.16 A propensity score matching retrospective cohort study that compared one-day versus three-day DEX with aprepitant and 5HT3RA for the prevention of CINV associated with carboplatin found that three-day DEX was significantly superior to one-day DEX for preventing nausea (82.5% vs. 44.4%). The study additionally found that the average severity of nausea was beyond “moderate” from day two in the one-day DEX group compared to day five in the three-day DEX group.17 Thus, CINV associated with carboplatin during the delayed phase may be more difficult to control than that in the acute phase, and continuous DEX dosing beyond day one may play an important role in preventing delayed nausea. These results support our findings, which suggest that three-day DEX with NK1RA and 5HT3RA may be preferable for patients receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy, even if they are receiving triplet antiemetic prophylaxis.

We were unable to perform subgroup analysis of patients who received non-carboplatin MEC among the 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA groups due to insufficient data; thus, the superiority of 3-DEX + NK1RA over 1-DEX + NK1RA in non-carboplatin MEC remains unclear. However, given the benefit of 3-DEX + NK1RA over 1-DEX + NK1RA among the total population, continuous administration of DEX beyond day one may increase the benefit of prophylaxis for delayed-onset CINV in patients receiving non-carboplatin MEC. In particular, because oxaliplatin is known to induce a high incidence of delayed-onset nausea,45,46 DEX-sparing regimens should be used with caution in patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy.

Delayed-onset nausea is an important part of CINV, and difficult to control.47-49 In this NMA, absolute risk difference between 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA in DP-NN was ≥20%. This result suggests extended DEX dose may play an important role to control delayed-onset nausea in triplet antiemetic prophylaxis with NK1RA. In previous phase III study, NK1RA did not significantly reduce visual analog scale for nausea compared to placebo.50 Thus the addition of olanzapine should be considered when limiting administration of DEX to day one in patients with identifiable risk factors for CINV because olanzapine is possibly more effective than NK1RA for preventing nausea.51-53

In this NMA, we classified patients who received a three-day dose of a first-generation 5HT3RA or single dose of palonosetron into the long 5HT3RA subgroup to examine them separately from patients who received single-day administration of 5HT3RA, and to set similar conditions for the effect of 5HT3RA on CINV in the delayed phase. In the long 5HT3RA group, 3-DEX + NK1RA showed a nonsignificant superior effect to 1-DEX + NK1RA, and the absolute risk difference between 3-DEX and 1-DEX in CR-DP was 11.4%. The results of a prior RCT suggested that a one-day dose of DEX in combination with palonosetron and NK1RA was an insufficient antiemetic prophylaxis for a cisplatin-containing regimen.11 In contrast, a recent study reported that the DEX-sparing strategy in combination with netupitant and palonosetron showed comparable antiemetic effects to four-day DEX in patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy.54 Future studies should examine the usefulness of the DEX-sparing strategy in combination with netupitant and palonosetron for carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Cost is an important factor when selecting antiemetic measures. DEX is less expensive than other antiemetic agents such as palonosetron and NK1RAs. Given that our results suggest there may be considerable benefits to continuous DEX administration, we propose that the majority of patients, with the exception of patients who should receive minimal DEX, such as those intolerant to corticosteroids, should receive DEX beyond day one of treatment.

This NMA has several limitations. First, many of our arguments are based on indirect comparisons between 3-DEX + NK1RA and 1-DEX + NK1RA, which cannot replace the direct comparisons obtained from randomized studies. Second, we could not examine the outcome for those using non-carboplatin MEC due to insufficient data. Further randomized studies are needed to determine the benefits of the DEX-sparing regimen in triplet antiemetic prophylaxis, especially those containing carboplatin and oxaliplatin, which have been shown to benefit from the addition of NK1RA and to lead to a high incidence of delayed-onset CINV.16,45,46,55 Third, individual studies in this population are relatively small, which significantly limits statistical power and sensitivity to detect differences. Despite these limitations, our findings, which were derived from available RCT data, highlight concerns related to using the DEX-sparing strategy in combination with NK1RA for the prevention of CINV in patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC.

Conclusion

Our NMA showed that a three-day dose of DEX with NK1RA tended to have greater antiemetic benefit than a one-day dose of DEX with NK1RA; the absolute risk difference between a three-day and one-day dose of DEX with NK1RA was 9.0% and 24.7% in CR-DP and NN-DP, respectively. Among patients who received carboplatin-based chemotherapy, the absolute risk difference in CR-DP between a three-day and one-day dose of DEX with NK1RA was 12.3%. Therefore, care is needed when choosing the DEX-sparing strategy with NK1RA for patients receiving carboplatin and non-carboplatin MEC. The strategy may be more suitable for selected patients, such as those with few identifiable risk factors for CINV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the participants for their contribution to this study. We are also grateful to Takuma Ishihara from Gifu University Hospital Innovative and Clinical Research Promotion Center, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan, for providing many suggestions on statistical analysis methods.

Contributor Information

Daichi Watanabe, Department of Pharmacy, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Hirotoshi Iihara, Department of Pharmacy, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Hironori Fujii, Department of Pharmacy, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Akitaka Makiyama, Cancer Center, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Shohei Nishida, Department of Pharmacy, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Akio Suzuki, Department of Pharmacy, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan.

Funding

This study was funded by a Gifu University Hospital Pharmacy Department Operation Grant.

Conflict of Interest

Akitaka Makiyama: Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. Ltd., and Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: D.W., H.I., H.F. Provision of study material/patients: D.W., H.I., S.N. Collection and/or assembly of data: D.W., H.I., S.N. Data analysis and interpretation: D.W., H.I., A.S. Manuscript writing: D.W., H.I., A.S., A.M. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Rowbottom L, Stinson J, McDonald R, et al. Retrospective review of the incidence of monitoring blood glucose levels in patients receiving corticosteroids with systemic anticancer therapy. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(2):70-77. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakamura M, Ishiguro A, Muranaka T, et al. A prospective observational study on effect of short-term periodic steroid premedication on bone metabolism in gastrointestinal cancer (ESPRESSO-01). Oncologist. 2017;22(5):592-600. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vardy J, Chiew KS, Galica J, et al. Side effects associated with the use of dexamethasone for prophylaxis of delayed emesis after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(7):1011-1015. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aapro M, Fabi A, Nolè F, et al. Double-blind, randomised, controlled study of the efficacy and tolerability of palonosetron plus dexamethasone for 1 day with or without dexamethasone on days 2 and 3 in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(5):1083-1088. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Komatsu Y, Okita K, Yuki S, et al. Open-label, randomized, comparative, phase III study on effects of reducing steroid use in combination with Palonosetron. Cancer Sci. 2015;106(7):891-895. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Celio L, Frustaci S, Denaro A, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(8):1217-1225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0941-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furukawa N, Kanayama S, Tanase Y, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone to prevent nausea and vomiting in patients receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(11):3317-3322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2760-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kosaka Y, Tanino H, Sengoku N, et al. Phase II randomized, controlled trial of 1 day versus 3 days of dexamethasone combined with palonosetron and aprepitant to prevent nausea and vomiting in Japanese breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1405-1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2905-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okada Y, Oba K, Furukawa N, et al. One-day versus three-day dexamethasone in combination with palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review and individual patient data-based meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2019;24(12):1593-1600. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Celio L, Bonizzoni E, Zattarin E, et al. Impact of dexamethasone-sparing regimens on delayed nausea caused by moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomised evidence. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ito Y, Tsuda T, Minatogawa H, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blinded phase III study comparing dexamethasone on day 1 with dexamethasone on days 1 to 3 with combined neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist and palonosetron in high-emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(10):1000-1006https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Antiemesis Version 1.2021. Accessed December 23, 2020.https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf.

- 13. Aogi K, Takeuchi H, Saeki T, et al. Optimizing antiemetic treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Japan: update summary of the 2015 Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antiemesis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-020-01818-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(24):2782-2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roila F, Warr D, Hesketh PJ, et al. 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(1):289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iihara H, Shimokawa M, Hayashi T, et al. A nationwide, multicenter registry study of antiemesis for carboplatin-based chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Japan. Oncologist. 2020;25(2):e373-e380. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayashi T, Shimokawa M, Mizuki F, et al. Efficacy of one-day versus multiple-day dexamethasone for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in lung cancer patients receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy: a propensity score–matched analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(9):5029-5035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06061-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang J, Carlin BP, Neaton JD, et al. Network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials: reporting the proper summaries. Clin Trials. 2014;11(2):246-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin L, Zhang J, Hodges JS, et al. Performing arm-based network meta-analysis in R with the pcnetmeta package. J Stat Softw. 2017;80:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Badar T, Cortes J, Borthakur G, et al. Phase II, open label, randomized comparative trial of ondansetron alone versus the combination of ondansetron and aprepitant for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving regimens containing high-dose cytara. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1-6. Article ID: 497597. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/497597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Di Renzo N, Melillo L, Porretto F, et al. Every-other-day palonosetron plus aprepitant for prevention of emesis following induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized, controlled study from the “Rete Ematologica Pugliese”. Cancer Med. 2020;9(1):170-178. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hesketh PJ, Wright O, Rosati G, et al. Single-dose intravenous casopitant in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of oxaliplatin-induced nausea and vomiting: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, two arm, parallel group study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(7):1471-1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1235-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kitayama H, Tsuji Y, Sugiyama J, et al. Efficacy of palonosetron and 1-day dexamethasone in moderately emetogenic chemotherapy compared with fosaprepitant, granisetron, and dexamethasone: a prospective randomized crossover study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(6):1051-1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0823-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmitt T, Goldschmidt H, Neben K, et al. Aprepitant, granisetron, and dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after high-dose melphalan in autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(30):3413-3420. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.55.0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xiong J, Zhao G, Yang S, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and pharmacokinetic impact of aprepitant in sarcoma patients receiving ifosfamide and doxorubicin chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2019;36(2):355-364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0862-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Inoue A, Yamada Y, Matsumura Y, et al. Randomized study of dexamethasone treatment for delayed emesis, anorexia and fatigue induced by irinotecan. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(8):528-532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-003-0488-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aridome K, Mori S-I, Baba K, et al. A phase II, randomized study of aprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapies in colorectal cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4(3):393-398. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2015.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Celio L, Frustaci S, Denaro A, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(8):1217-1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Furukawa N, Kanayama S, Tanase Y, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone to prevent nausea and vomiting in patients receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(11):3317-3322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2760-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ito Y, Karayama M, Inui N, et al. Aprepitant in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):259-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaushal P, Atri R, Soni A, et al. Comparative evaluation of triplet antiemetic schedule versus doublet antiemetic schedule in chemotherapy-induced emesis in head and neck cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:567. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2015.567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim JE, Jang JS, Kim JW, et al. Efficacy and safety of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting during the first cycle of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy in Korean patients with a broad range of tumor types. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):801-809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3463-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kusagaya H, Inui N, Karayama M, et al. Evaluation of palonosetron and dexamethasone with or without aprepitant to prevent carboplatin-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(3):410-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maehara M, Ueda T, Miyahara D, et al. Clinical efficacy of aprepitant in patients with gynecological cancer after chemotherapy using paclitaxel and carboplatin. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(8): 4527-4534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsuura M, Satohisa S, Teramoto M, et al. Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with gynecologic cancers: a randomized, multicenter, phase-II trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(10):1607-1613. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.12748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nishimura J, Satoh T, Fukunaga M, et al. Combination antiemetic therapy with aprepitant/fosaprepitant in patients with colorectal cancer receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy (SENRI trial): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(10):1274-1282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rapoport BL, Jordan K, Boice JA, et al. Aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with a broad range of moderately emetogenic chemotherapies and tumor types: a randomized, double-blind study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):423-431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0680-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schwartzberg LS, Modiano MR, Rapoport BL, et al. Safety and efficacy of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after administration of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy or anthracycline and cyclophosphamide regimens in patients with cancer: a randomised, active-controlled. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1071-1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00034-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sugimori Y, Ota T, Ujihira T, et al. A phase II randomised study to evaluate the efficacy of aprepitant plus palonosetron for preventing delayed-phase CINV associated with TC therapy in gynaecological cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(9):1454-1459. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.13378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanioka M, Kitao A, Matsumoto K, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of aprepitant in nondrinking women younger than 70 years receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):859-865. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weinstein C, Jordan K, Green SA, et al. Single-dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(1):172-178. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yahata H, Kobayashi H, Sonoda K, et al. Efficacy of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with a moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimen: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study in patients with gynecologic cancer receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(3):491-497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0928-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hesketh PJ, Schnadig ID, Schwartzberg LS, et al. Efficacy of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist rolapitant in preventing nausea and vomiting in patients receiving carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(15):2418-2425. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v232-v243. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tamura K, Aiba K, Saeki T, et al. Testing the effectiveness of antiemetic guidelines: results of a prospective registry by the CINV Study Group of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(5):855-865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0786-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsuji Y, Baba H, Takeda K, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in 190 colorectal cancer patients: a prospective registration study by the CINV study group of Japan. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(8):753-758. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2017.1317746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ng T, Mazzarello S, Wang Z, et al. Choice of study endpoint significantly impacts the results of breast cancer trials evaluating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;155(2):337-344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3669-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ng TL, Hutton B, Clemons M.. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: time for more emphasis on nausea? Oncologist. 2015;20(6):576-583. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hernandez Torres C, Mazzarello S, Ng T, et al. Defining optimal control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting-based on patients’ experience. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(11):3341-3359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2801-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Albany C, Brames MJ, Fausel C, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III cross-over study evaluating the oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant in combination with a 5HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone in patients with germ cell tumors receiving 5-day cisplatin combination chemotherapy regimens: a Hoosier Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(32):3998-4003. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tan L, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Clinical research of Olanzapine for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28(1):131. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-28-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chow R, Chiu L, Navari R, et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) as reported in phase I and II studies: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):1001-1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3000-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC, et al. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(5):188-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Celio L, Cortinovis D, Cogoni AA, et al. Dexamethasone-sparing regimens with oral netupitant and palonosetron for the prevention of emesis caused by high-dose cisplatin: a randomized noninferiority study. Oncologist. 2021;26(10):e1854-e1861. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hayashi T, Shimokawa M, Matsuo K, et al. 5HT3RA plus dexamethasone plus aprepitant for controlling delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(2):744-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.