Abstract

Background

The prognosis of patients with metastatic malignant melanoma is very poor and partly due to resistance to conventional chemotherapies. The study’s objectives were to assess the activity and tolerability of apatinib, an oral small molecule anti-angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with recurrent advanced melanoma.

Methods

This was a single-arm, single-center phase II trial. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) and the secondary endpoints were objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), and overall survival (OS). Eligible patients had received at least one first-line therapy for advanced melanoma and experienced recurrence. Apatinib (500 mg) was orally administered daily.

Results

Fifteen patients (V660E BRAF status: 2 mutation, 2 unknown, 11 wild type) were included in the analysis. The median PFS was 4.0 months. There were two major objective responses, for a 13.3% response rate. Eleven patients had stable disease, with a DCR of 86.7%. The median OS was 12.0 months. The most common treatment-related adverse events of any grade were hypertension (80.0%), mucositis oral (33.3%), hand-foot skin reaction (26.7%), and liver function abnormalities, hemorrhage, diarrhea (each 20%). The only grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse effects that occurred in 2 patients was hypertension (6.7%) and mucositis (6.7%). No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Conclusion

Apatinib showed antitumor activity as a second- or above-line therapy in patients with malignant melanoma. The toxicity was manageable.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

Keywords: melanoma, targeted therapy, apatinib, progression-free survival, overall survival

Patients with metastatic malignant melanoma have a poor prognosis due in part to resistance to conventional chemotherapies. This article assesses the activity and tolerability of apatinib, an oral small molecule anti-angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with recurrent advanced melanoma.

Lessons Learned.

In this single-arm, phase II study involving pretreated metastatic malignant melanoma patients, apatinib yielded a clinically meaningful progression-free survival of 4.0 months with an acceptable toxicity profile.

Apatinib is worthy of continued investigation for clinical use in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma.

Discussion

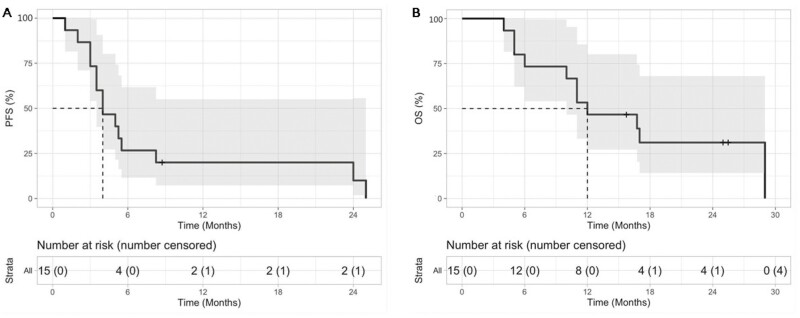

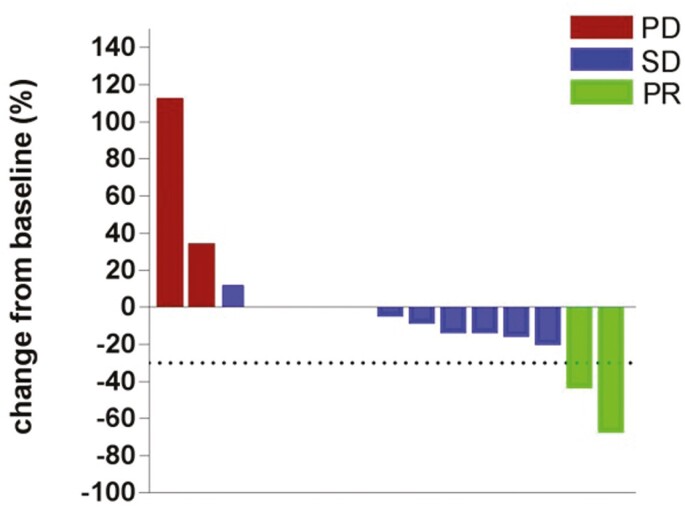

The prognosis of metastatic malignant melanoma after previous exposure to effective therapies remains poor with limited treatment options. In this study, apatinib showed antitumor activity in patients with malignant melanoma, with median PFS and OS of 4.0 and 12.0 months, respectively (Figure 1). In the univariate analysis, several baseline factors (sex, age, subtypes, lactate dehydrogenase level, number of organ sites, with metastasis, and treatment lines) were not associated with either PFS or OS (Table 1). No complete response was obtained, but a partial response was observed in 2 patients (Figure 2). The ORR was 13.3%, and DCR was 86.7%.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot for the best percentage change in target lesion size.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of several baseline factors

| Factor | Median PFS | Median OS |

|---|---|---|

| Subtypes | ||

| Cutaneous (3) | 3.5 months | 5 months |

| Mucosal or acral (12) | 4.5 months | 14.38 months |

| P value | .6058 | .6442 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.6913 (0.1701-2.81 | 1.525 (0.2544-9.139) |

| LDH level (n) | ||

| Normal value of LDH (1) | 3.75 months | 14.38 months |

| Beyond normal value of LDH (5) | 5.25 months | 11 months |

| P value | .4983 | .6370 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.488 (0.4712-4.1096) | 1.373 (0.3678-5.128) |

| Treatment lines (n) | ||

| Second-line treatment (9) | 5 months | 11 months |

| Third-line treatment or above | 4 months | 16.38 months |

| P value | .6198 | .4213 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.7319 (0.2132-2.512) | 1.645 (0.4891-5.53) |

| Number of organ sites with metastasis (n) | ||

| Three or less (5) | 5.5 months | 16.75 months |

| Four or more (10) | 3.75 months | 11.5 months |

| P value | .7258 | .9043 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.8158 (0.2616-2.544) | 1.083 (0.2934-4.001) |

| Sex (n) | ||

| Male (10) | 4 months | 17 months |

| Female (5) | 4.5 months | 10.5 months |

| P value | .4038 | .1815 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 0.4188 (0.1167-1.504) | 0.3886 (0.09711-1.555) |

| Age (n) | ||

| ≤60 years (7) | 4 months | 11 months |

| >60 years (8) | 4.5 months | 18.75 months |

| P value | .7191 | .3008 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.228 (0.401-3.76) | 1.963 (0.547-7.047) |

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of median PFS shown on the left (A) and median OS shown on the right (B). Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

The most common grade 1 adverse events were hypertension (40.0%), mucositis oral (20.0%), diarrhea (20.0%), hand-foot skin reaction (13.3%), hemorrhage (13.3%), anorexia (13.3%), and nausea (13.3%). The most common grade 2 adverse events were hypertension (33.3%), hand-foot skin reaction (13.3%), and liver function abnormalities (13.3%). Grade 3 adverse events included hypertension (6.7%) and mucositis oral (6.7%). No patient had a grade 4 adverse event (Table 2). No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Table 2.

Adverse events

| Event | Patients, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Hypertension | 12 (80) | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Oral ulceration | 5 (33.3) | 3 (20) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Hand-foot skin reaction | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Liver function damage | 3 (20) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hemorrhage | 3 (20) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (20) | 3 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anepithymia | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Apatinib efficacy and safety in this study were consistent with a prospective phase I study launched by Guo’s team.1 In that study, 12 patients were treated with various apatinib doses (250 or 500 mg daily) plus temozolomide (100 or 200 mg). Among them, 1 patient achieved PR and 9 achieved SD. The ORR was 8.3% and DCR was 83%. mPFS was 3.3 months and mOS 6.3 months. Regarding safety, dose-limiting toxicities were not observed even in the temozolomide 300 mg plus apatinib 500 mg daily group. In a retrospective analysis of 22 patients treated with 500 mg apatinib per day, ORR was 9.1% and DCR 59.1%, with a mPFS of 7.5 months.2 The common features of these 2 studies and ours is that the patients enrolled were Chinese, with mainly malignant melanomas of the mucosa and extremities. These 2 types of malignant melanoma have a low BRAF gene mutation rate; therefore, BRAF inhibitors and PD-1 antibodies may be less effective.3 Apatinib may thus have greater potential in this patient population.

Trial Information

| Disease | Melanoma |

| Stage of disease/treatment | Metastatic/advanced |

| Prior therapy | More than 2 prior regimens |

| Type of study | Phase II, single arm |

| Primary endpoint | Progression-free survival |

| Secondary endpoints | Overall survival, ORR, disease control rate |

| Additional details of endpoints or study design | The patients in this study were from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Inclusion Criteria: central-laboratory confirmed melanomas that were metastatic and refractory to first-line treatment (stage IV); age, ≥18 and ≤70 years; ECOG PS, 0 or 1; life expectancy, ≥3 months; adequate hepatic, renal, heart, and hematologic functions, ANC ≥ 1.5 × 109/L, PLT ≥ 100 × 109/L, HB ≥90 g/L, TBIL ≤1.5×ULN, and ALT or AST ≤2.5×ULN (or ≤5×ULN in patients, with liver metastases), serum Cr ≤1.5×ULN and Cr clearance ≥60 mL/min; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ lower limit of normal (50%). Exclusion criteria: uncontrollable hypertension, grade II above myocardial ischemia or infarction, poor arrhythmic control (including QTc interval: male ≥450 ms and female ≥470 ms); a variety of factors affecting oral absorption (such as inability to swallow, nausea, vomiting, chronic diarrhea, intestinal obstruction, etc.); patients with gastrointestinal bleeding risk; coagulation dysfunction (INR >1.5, PT >ULN + 4s, or APTT >1.5 ULN), with bleeding tendency or ongoing thrombolysis or anti-blood coagulation treatment; long-term unhealed wounds or fractures; active bleeding, within 30 days after major surgery; intracranial metastasis; pregnant or lactating women; allergic to apatinib; severe liver and kidney dysfunction; the investigators believe that there is any condition that may harm the subject or result in the inability to meet the research requirements or a concomitant disease that seriously endangers the patient’s safety or affects the patient in completing the study. |

| It should be noted that our trial was initially designed to enroll patients in second-line treatment. However, since the CFDA approved the PD-1 antibody in July 2018 to be used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma after failure of previous standard treatments, it was difficult to recruit patients again. Thus, the protocol was updated to allow patients above the second line to join the research. Finally, in this clinical trial, 9 patients were treated with apatinib as second-line treatment, 3 as third-line treatment, 2 as fourth-line treatment, and 1 as fifth-line treatment. All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University. | |

| Investigator’s analysis | Active and should be pursued further |

Drug Information

| Generic/working name | Apatinib |

| Company name | Jiangsu HengRui Medicine Co., Ltd |

| Drug type | Small molecule |

| Drug class | Angiogenesis, VEGF |

| Dose | 500 mg per flat dose |

| Route | oral (p.o.) |

| Schedule of administration | 500 mg, once daily |

Patient Characteristics

| Number of patients, male | 10 |

| Number of patients, female | 5 |

| Stage | Stage IV 15 (100%) |

| Number of prior systemic therapies | Median (range):2 (2-5) |

| Performance status: ECOG | 0—0 1—0 2—0 3—0 Unknown—0 |

| Cancer types or histologic subtypes | BRAF wild type 11 BRAF mutated 2 BRAF Unkown 2 |

Primary Assessment Method

| Title | Response assessment |

|---|---|

| Number of patients screened | 17 |

| Number of patients enrolled | 15 |

| Number of patients evaluable for toxicity | 15 |

| Number of patients evaluated for efficacy | 15 |

| Evaluation method | RECIST 1.1 |

| Response assessment CR | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response assessment PR | n = 2 (13.3%) |

| Response assessment SD | n = 11 (73.3%) |

| Response assessment PD | n = 2 (13.3%) |

| (Median) duration assessments PFS | 4.0 months, CI: |

| (Median) duration assessments OS | 12.0 months, CI: |

Adverse Events Cycle 1

| Name | *NC/NA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | All grades |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 20% | 40% | 33% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 80% |

| Mucositis oral | 67% | 20% | 7% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 33% |

| Rash: hand-foot skin reaction | 73% | 13% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 27% |

| Liver function abnormalities | 80% | 7% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 20% |

| Hemorrhage | 80% | 13% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 20% |

| Diarrhea | 80% | 20% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 20% |

| Nausea | 87% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 13% |

| Anorexia | 87% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 13% |

| Rash acneiform | 93% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 7% |

| Fever | 93% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 7% |

The most common grade 1 adverse events were hypertension (40.0%), mucositis oral (20.0%), diarrhea (20.0%), hand-foot skin reaction (13.3%), hemorrhage (13.3%), anorexia (13.3%), nausea (13.3%). The most common grade 2 adverse events were hypertension (33.3%), hand-foot skin reaction (13.3%), and liver function abnormalities (13.3%). Grade 3 adverse events include hypertension (6.7%) and mucositis oral (6.7%) (Table 2). No patient had a grade 4 adverse event. No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

| Completion | Study Completed |

| Investigator’s assessment | Active and should be pursued further |

For several decades, dacarbazine alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents was recommended as first-line treatment for patients with advanced melanoma. However, the resulting ORR has been shown to be only 15%, without improvement in survival.4 In recent years, the treatment has been revolutionized by advances in molecular-targeted therapy and immunotherapy. These treatments include targeted therapy with selective BRAF inhibitors vemurafenib and dabrafenib in combination with MEK inhibitors cobimetinib and trametinib. Further, immune checkpoint inhibitors including anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA4) ipilimumab and tremilimumab; and anti-programmed cell death protein 1 antibodies (anti-PD1) nivolumab and pembrolizumab among others, demonstrated excellent results in clinical trials.5–13 In BRAF V600E melanoma, combining BRAF inhibitors, with MEK inhibitors, showed clear synergistic activity which led to high response rates (70%), a rapid response induction, and symptom control. The PFS is approximately 12 months.14,15 Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are effective in BRAF inhibitor-resistant mutant melanoma.16,17 There is no recommended standard therapy for patients who do not respond to molecular-targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

In Asia, malignant melanoma is a rare disease and quite different in morphological subtypes compared with its Western counterparts.18 Acral melanoma (approximately 50%) and mucosal melanoma (20-30%), which are more common in China,19 often lack mutations in BRAF, RAS, or NF1,20 and these subtypes less frequently respond to anti-PD1 antibody.21 In China, the approved agents for the treatment of metastatic melanoma include vemurafenib, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy.19 However, ordinary patients with a limited financial situation cannot afford expensive targeted drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Moreover, the value of these treatments needs further study in Chinese acral and mucosal melanomas.19 The status quo shows that we need to explore the value of other drugs in the treatment of melanoma.

Apatinib is an oral, small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor-2 (VEGFR-2).22 It inhibits tyrosine kinases such as PDGFR-β, c-SRC, c-Kit, and MET, reducing tumor microvessel density and effectively blocking tumor cells.23,24 It can also upregulate the expression of cell cycle inhibitor p21 and p27 and downregulate cyclin B1 and cdc2.25 Apatinib has anti-tumor potential against many tumors types, including hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric, non-small cell lung, and breast cancers.26–28 To date, few studies on malignant melanoma treatment using apatinib exist. Therefore, our study investigated the anti-tumor effect of apatinib on malignant melanoma. Additionally, the treatment tolerability was evaluated.

As a BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib is superior to chemotherapy concerning PFS, OS, and ORR, in BRAF mutant advanced melanoma patients.29 A second BRAF inhibitor, dabrafenib, exhibited a way to improve PFS significantly, compared with chemotherapy.6 Compared with BRAF inhibitors, the MEK inhibitors trametinib and binimetinib had lower ORR (20% vs 50%); however, they were superior, when combined and when compared with chemotherapy, in patients with BRAF-mutant advanced melanoma.30,31 The majority of patients treated with BRAF or MEK inhibitors develop drug resistance. Combining BRAF and MEK inhibitors may overcome this limitation. The superiority of combining these 2 inhibitor categories, compared with single-agent inhibitor therapy, was confirmed in several randomized trials, with PFS rate of 19% and OS, 34% at 5 years of receiving dabrafenib plus trametinib32; mPFS, 14.9 months and mOS, 33.6 months receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib33; mPFS, 9.9 months and mOS, 22.5 months receiving vemurafenib plus cobimetinib34; and mPFS, 10-14 months and mOS, about 24 months.35 The BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination improves outcomes in melanoma patients, but resistance eventually occurs. Other molecular-targeted strategies are also being studied, including the use of small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors of VEGF.

A retrospective analysis of Chinese melanoma announced at the 2018 ESMO conference showed that the PFS of the first-line chemotherapy regimen (dacarbazine+cisplatin+ endostain) was 4 months, and the PFS of the second-line chemotherapy regimen (paclitaxel+carboplatin+bevacizumab) was 2 months.36 In the present study, disease progression or death occurred in 14 of the 15 patients (93%) at the time of data cutoff. The median PFS duration was 4.0 months. The median OS was 12 months. Univariate analysis showed that several baseline factors (sex, age, subtypes, lactate dehydrogenase level, number of organ sites, with metastasis, and treatment lines) were not associated with either PFS or OS. Although apparently not as effective as BRAF and MEK inhibitors, considering that the patients enrolled are on at least second-line treatment, apatinib has shown an efficacy signal and is worthy of large-scale clinical studies in malignant melanoma.

The toxicity profile was generally consistent with prior results using apatinib in a phase I study, with the safety data of other multi-kinase inhibitors of the same class. The adverse events were hypertension, hand-foot skin reactions, hemorrhage, diarrhea, sick, rash, and fever. Most of these adverse events were mildly graded. Only a small proportion of subjects reported grade 3/4 events. Among these, one patient (6.7%) had grade 3 hypertension and one (6.7%), grade 4 oral ulceration.

The present study had some limitations. When the IIT study was designed, vemurafenib or PD-1 mAb had not been approved for use in Chinese patients with melanoma, and dacarbazine-based chemotherapy was the first-line treatment. Therefore, the initial inclusion criteria consisted of treating chemotherapy-refractory melanoma patients with first-line therapy. However, with vemurafenib and PD-1 approval in melanoma in China subsequently, patients had more standard choices. It became difficult to enroll new patients who have received only the first-line treatment. After careful discussion, the study investigators and sponsor revised our regimen, according to the applicable regulations, protecting the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects. Consent was obtained from patients with second-line or above treatment. Eventually, 15 patients were analyzed in the study, among whom 9 had first-line treatment and 6 had second-line or above treatment before receiving apatinib. Additionally, the patients enrolled in this study were from China. The generalizability to other populations remains unclear. Finally, due to the small sample size of this study, the results we have obtained on patient prognosis are not significantly correlated, with baseline data and need to be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, apatinib had antitumor activity in patients with metastatic melanoma in the second-line setting or beyond. The toxicity was manageable and acceptable.

Contributor Information

Shumin Yuan, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Qiang Fu, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Lingdi Zhao, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Xiaomin Fu, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Tiepeng Li, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Lu Han, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Peng Qin, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Yingkun Ren, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Mingke Huo, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Zhimeng Li, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Chaomin Lu, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Long Yuan, Department of General Surgery, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Quanli Gao, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Zibing Wang, Department of Immunotherapy, Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81972690 and 81000914). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Yang L, Zhu H, Luo P, Chen S, Xu Y, Wang C.. Safety and efficacy of apatinib combined with temozolomide in advanced melanoma patients after conventional treatment failure. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:1155-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang L, Zhu H, Luo P, Chen S, Xu Y, Wang C.. Apatinib mesylate tablet in the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:5333-5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Kuk D, et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3354-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rastrelli M, Tropea S, Rossi CR, Alaibac M.. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. In Vivo. 2014;28(6):1005-1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):358-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C, et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):323-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):30-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smalley KS, Sondak VK.. Inhibition of BRAF and MEK in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):410-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):908-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1248-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):30-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mangana J, Cheng PF, Schindler K, et al. Analysis of BRAF and NRAS mutation status in advanced melanoma patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies: association with overall survival? PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. ; KEYNOTE-006 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bai X, Mao L, Guo J.. Comments on Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of melanoma 2018 (English version). Chin J Cancer Res. 2019;31(5):740-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. No authors listed. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of melanoma 2018 (English version). Chin J Cancer Res. 2019;31(4):578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161(7):1681-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klemen ND, Wang M, Rubinstein JC, Olino K, Clune J, Ariyan S, et al. Survival after checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic acral, mucosal and uveal melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tian S, Quan H, Xie C, et al. YN968D1 is a novel and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(7):1374-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tong XZ, Wang F, Liang S, et al. Apatinib (YN968D1) enhances the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutical drugs in side population cells and ABCB1-overexpressing leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(5):586-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geng R, Li J.. Apatinib for the treatment of gastric cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(1):117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang C, Qin S.. Apatinib targets both tumor and endothelial cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4570-4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gomila A, Carratalà J, Badia JM, et al. ; VINCat Colon Surgery Group. Preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa surgical site infections after elective colorectal surgery: a multicenter prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang L, Liang L, Yang T, et al. A pilot clinical study of apatinib plus irinotecan in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma: Clinical Trial/Experimental Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(49):e9053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. ; BRIM-3 Study Group. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507-2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. ; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ascierto PA, Schadendorf D, Berking C, et al. MEK162 for patients with advanced melanoma harbouring NRAS or Val600 BRAF mutations: a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robert C, Grob JJ, Stroyakovskiy D, et al. Five-year outcomes with dabrafenib plus trametinib in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):626-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, et al. Overall survival in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1315-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dréno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1248-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ugurel S, Röhmel J, Ascierto PA, et al. Survival of patients with advanced metastatic melanoma: the impact of novel therapies-update 2017. Eur J Cancer. 2017;83:247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cui C, Yan X, Liu S, Deitz A, Si L, Chi Z, et al. Treatment pattern and clinical outcomes of patients with locally advanced and metastatic melanoma in a real-world setting in China. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Suppl_8):1283. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.