Abstract

Overnutrition is a poor dietary habit that has been correlated with increased health risks, especially in the developed world. This leads to an imbalance between energy storage and energy breakdown. Many biochemical processes involving hormones are involved in conveying the excess of energy into pathological states, mainly atherosclerosis, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. Diverse modalities of regular exercise have been shown to be beneficial, to different extents, in overcoming the overnutrition comorbidities. Cellular exercises, hormesis, are triggered by dietary protocols that could underlie the cellular mechanisms involved in modulating the deleterious effects of overnutrition through activation of specific cellular signal pathways. Of interest are the oxidative stress signaling, Nuclear factor erythroid-2, Insulin-like growth factor-1, AMP-activated protein kinase as well as Sirtuins and Nuclear factor Kappa N. Therefore, the value of intermittent fasting diets as well as different diets regimens inducing hormesis are evaluated in terms of their beneficial effects on health and longevity. In parallel, important effects of diets on the immune system are explored as essential components that can undermine the overall health outcome. In addition, the subtle but relevant relation between diet and sleep is investigated for its impact on the cardiovascular system and quality of life.

Keywords: Caloric excess, cellular exercise, Cardiovascular risks, Diets, Hormesis, Oxidative stress

I. Introduction

Which health condition is killing most people in the world today? According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the top two causes of death in the world are heart disease and stroke [1]. Together, ischaemic heart disease and stroke make up more deaths than the rest of the top 10 causes of death combined [1, 2]. What are the most prominent prognostics for heart disease and stroke? Poor dietary habits [3] and physical inactivity [4]. The American Heart Association 2018 statistic estimates that 45.5% of US deaths caused by heart disease, stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in 2012 were attributable to poor dietary habits [3]. The WHO recognized regular physical activity as a prominent pillar in the prevention of noncommunicable disease such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer [4]. The Framingham Heart Study has since identified that the leading modifiable risk factors for heart disease and stroke are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, overweight and obesity, and smoking [5]. Note that genetics also influences disease development as a non-modifiable risk factor [5]. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) explains that the risk of Americans developing and dying from cardiovascular disease would be substantially reduced if major improvements were made in diet and physical activity, control of high blood pressure and cholesterol, and smoking cessation [6]. With the exception of cigarette smoking, all of these risk factors – hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes – may stem from one cause: Overnutrition. What can we do about it? Eat less and exercise.

The main killers in society today, heart disease and stroke, are both intrinsically linked to overnutrition – a result of caloric excess and lack of energy expenditure. When our bodies process energy we either store excess energy or breakdown energy stores. In the developed world, there is a trend of increasing energy storage, and much less energy breakdown. There is a biochemical process involving hormones behind this link between energy storage and heart disease and stroke.

The aim of this review will focus on how caloric restriction triggers multiple molecular pathways that ultimately lead to hormetic effects resulting in cell longevity and resistance to cardiovascular disease, stroke and cancer. There are many brilliant sources in literature pointing to diverse molecular mechanisms, each strongly pointing to a specific pathway by which this hormetic effect is achieved. By culminating the results of research across all minute molecular mechanisms the cumulative effect on health is demonstrated in this review, resulting in cell longevity, longevity of life. This review hopes that by further demonstrating a molecular rational of the powerful effect of caloric restriction and physical activity, to spur on the motivation and growth of the societal shift toward change establishing habits of health that can prevent insidious habits of harmful inactivity.

II. Risk Factors Related to Caloric Excess

A. Diabetes

First, it is important to distinguish the definition of “sedentary” and physically “inactive” and between “physical activity” and “exercise.” Sedentary behavior refers to activities that do not increase energy expenditure beyond 1.5 metabolic equivalent units which include sleeping, sitting, lying down, and watching screen-based entertainment [7]. In contrast, “inactive” behavior is defined as that which is using insufficient amounts of moderate to vigorous physical activity [8]. The definition of “physical activity” is movement carried out by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure, while “exercise” is a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured and repetitive with the objective of improvement or maintenance of physical fitness [9].

Overeating and an inactive lifestyle results in an increase in net energy and inevitably the leading causes of death in the world, heart disease and stroke. In a state of overconsumption combined with lack of exercise (energy expenditure), the body stores this excess energy in glycogen and adipose tissue. Chronic energy excess leads to constant high levels of glucose and lipid in blood. Excess energy triggers free fatty acids which activate the G protein-coupled receptor GPR40, where acute exposure stimulates the receptor to mediate insulin secretion and chronic exposure impairs insulin secretion [10] as well as increased expression of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase 1 and fatty acid synthase in the liver, as well as insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and isoproterenol-stimulated lipolysis in adipocytes [11]. Many complex cascades lead to hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, and these molecular mechanisms separately could not comprehensively explain these pathological conditions causing hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia that results. Hyperglycemia leads to constant use of insulin, insulin resistance, and eventually breakdown of insulin producers such as the β-cells of the pancreas [12]. The insufficient insulin secretion that the worn down β-cells manifest as chronic hyperglycemia, resulting in elevated HbA1c, Fasting Plasma Glucose, and Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests. These are the tests used to diagnose Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. In summary, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus is a consequence of chronic hyperglycemia. Other than genetic predisposition, the source of all high levels of glucose in blood in Type 2 Diabetes mellitus is intake of too many calories with inadequate caloric expenditure.

B. Atherosclerosis and Hypertension

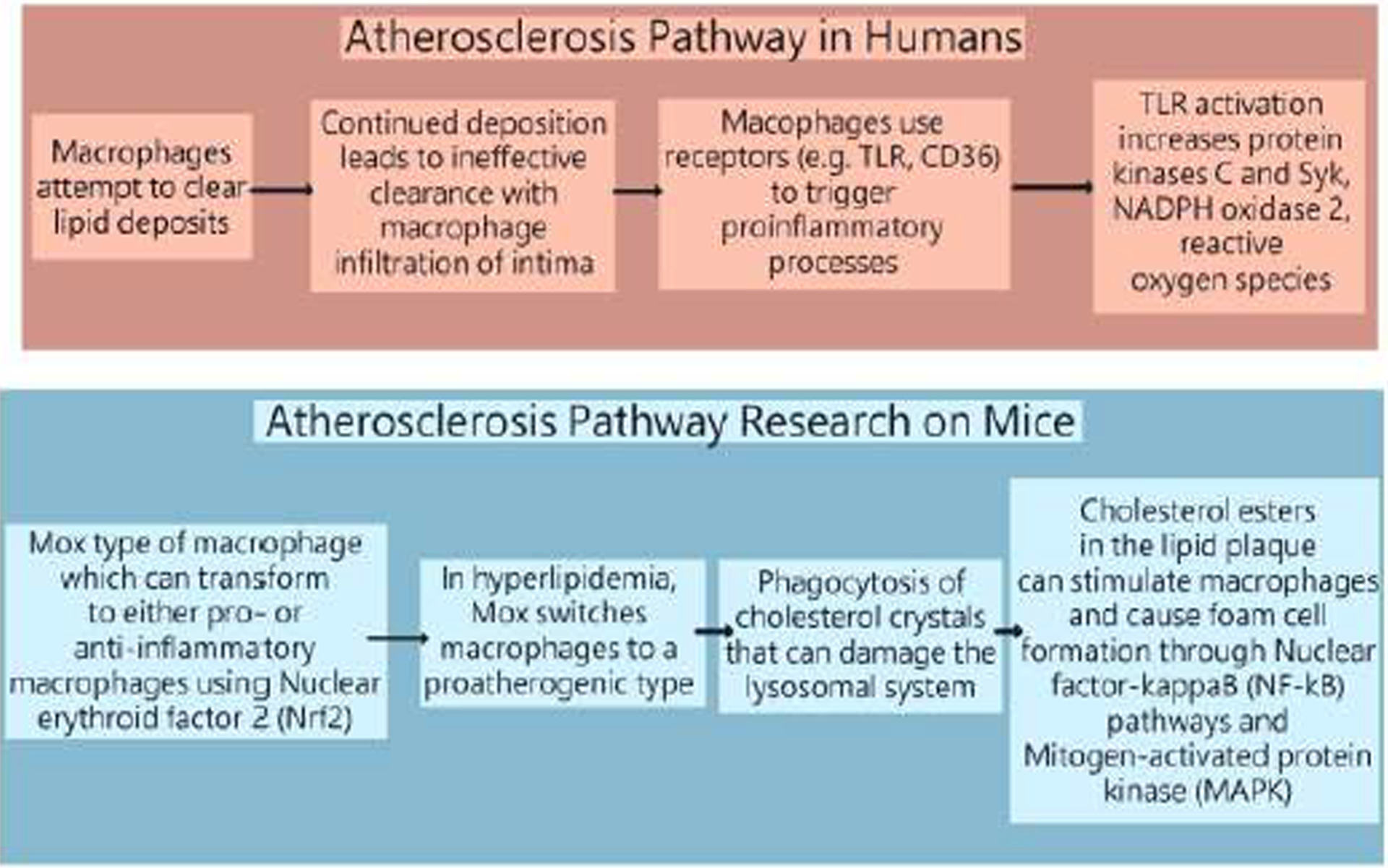

Similarly, atherosclerosis may also stem from the intake of excess calories. Constantly high levels of specific lipids in blood leads to lipid deposition in the arterial wall of large and medium sized vessels [13]. The particular lipids in the blood that can lead to deposition are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and other apo B-containing lipoproteins that include smaller triglyceride-rich very low-density lipoproteins that become modified by aggregation, acetylation or oxidation while they freely flux across the endothelial barrier, interacting with proteoglycans and can retain in the extracellular matrix [14, 15]. Lipid deposition drives influx of macrophages to clear the lipid deposits, but continued elevations leads to ineffective clearance and extracellular lipid pools with macrophage infiltration of the arterial intima [15, 16]. Macrophages use Toll-like Receptor (TLR) and scavenger receptors such as CD36 to trigger proinflammatory processes [16]. TLR activation triggers upregulation of protein kinases C and Syk, activation of NADPH oxidase 2, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [17]. Previous research on mice has discovered a Mox type of macrophage which can transform macrophage phenotypes to either pro- or anti-inflammatory macrophages through Nuclear erythroid factor 2 (Nrf2) [18]. In a state of hyperlipidemia, Mox switches macrophages to a proatherogenic type, resulting in phagocytosis of cholesterol crystals that can damage the lysosomal system [19, 20]. The cholesterol esters in the lipid plaque can stimulate macrophages and cause foam cell formation through Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways [21] and Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling [22] per graph below.

This atheromatous plaque may rupture and form a thrombus [23]. After the rupture of the plaque, the injured vessel undergoes a healing process during which there will be an increased calcium and fibrous material deposition, contributing to stenosis of the lumen with a constrictive, inward remodeling of the vessel. The stenosis and eventual non-compliant stiffening of the vessel is the etiology for hypertension secondary to atherosclerosis. According to the Merck Manual, 80% of hypertension is secondary to atherosclerotic changes [23]. At times, the thrombus caused by the lipid deposition can cause complete occlusion or can dislodge and cause thromboembolism of the coronary arteries or neurovascular system, causing heart disease, vessel dissection, and/or stroke [24].

C. Communities of Empowerment

Therefore, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, in addition to obesity, overweight, the aforementioned foremost risk factors of heart disease and stroke- are all intrinsically linked to our food intake and expenditure and physical inactivity. Consequently, the top two “organic” killers of humans, heart disease and stroke, are mainly caused by overnutrition; while, physical inactivity, which has been dubbed “the new smoking”, is the silent contributor to these diseases.

What can we do about it? Public education has been one of the most powerful tools of prevention [25]. The public demand for cultural changes has affected many restaurants and grocery stores to provide more healthful lifestyles and options. The need for increased access to healthier options are clear- as we can assess in these following studies. In a 30 year cohort study on cardiovascular disease etiology, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) [26], found that fruit and vegetable requirements were 30% more likely to be met with African Americans living in neighborhoods with one supermarket and 200% more likely with African Americans living in neighborhoods with two or more supermarkets [27]. Wealthier communities have 3–4 times more large chain supermarkets compared to low income neighborhoods [28]. The same low-income residents have a health equivalent which is 10 years older in terms of cardiovascular mortality risks [29]. Public health awareness has driven consumers to demand transparency through Nutrition Fact labelling and healthier options such as organic food and menu items higher in fruits and vegetables [30, 31]. Availability of grocery stores in neighborhoods of all income levels are one of the key steps in developing access to preventive health care. Grocery stores provide healthier choices which also should be corroborated with specific diets that balance energy intake and expenditure. This includes increasing opportunities for exercise as well.

III. Cellular to Physical Exercise

A. Cellular Exercise

Health is defined by the WHO as a “mental, social and physical well-being, not merely the absence of illness or disease”. In essence, we should advocate activities that improve well-being while avoiding or delaying disease progression. The aspects of our physical well-being that we can control are diet and exercise. These are both powerful tools to create well-being. Recent research has shown that by modifying our eating habits, we will allow our bodies to perform “cellular exercise,” a workout that may be more and more neglected in developed countries.

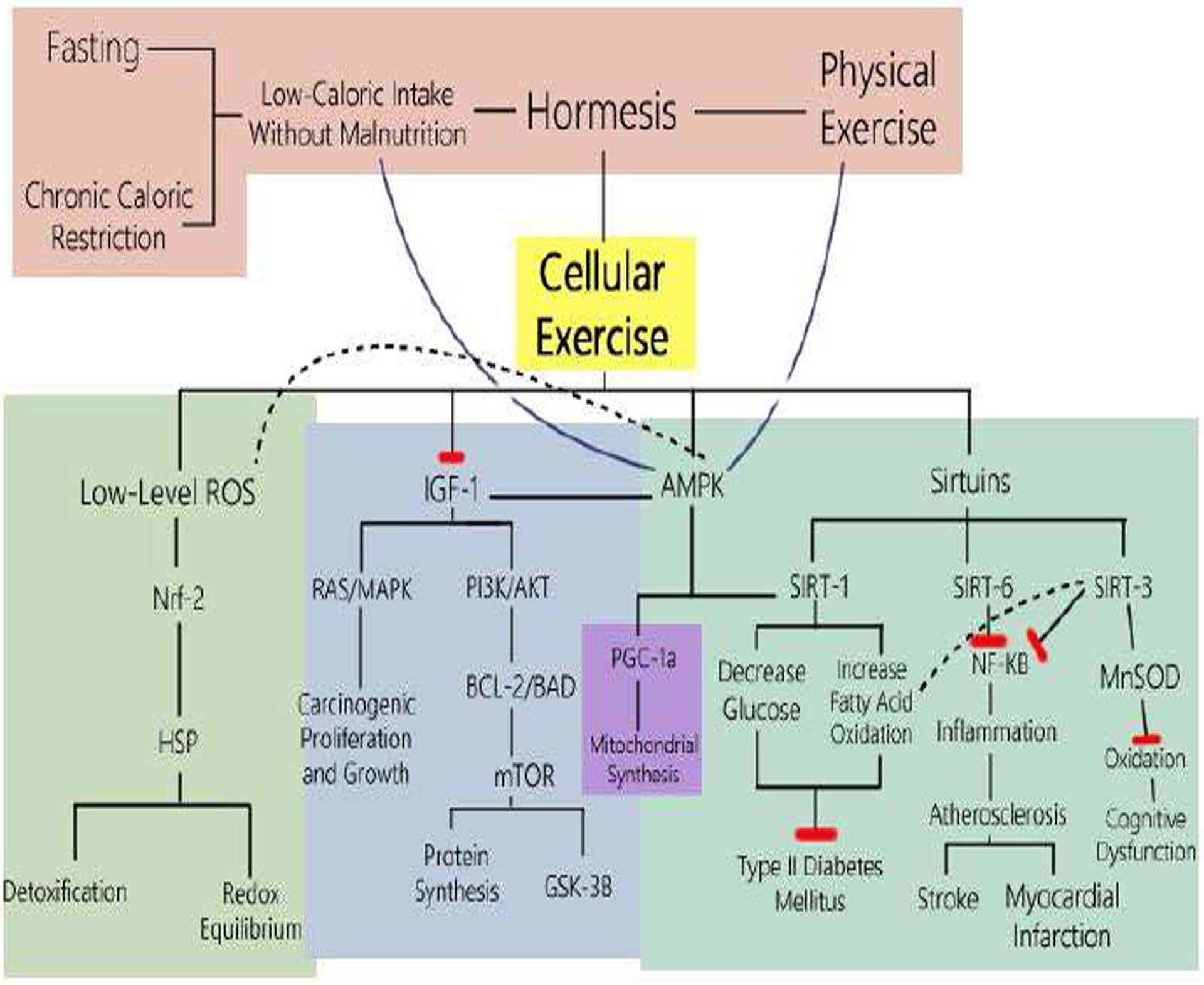

What is “cellular exercise”? It is a term the authors of this paper have coined to describe the interplay between molecular pathways caused by the stimuli of chronic caloric restriction and physical exercise that lead to physical well-being. These stimuli cause cellular stress that form adaptive hormetic effects which eventually translate to cell longevity and longevity of life [32]. The concept of cellular exercise is manifested by the interplay of multiple molecular mechanisms induced by caloric restriction and physical activity that strengthen the cell. Low levels of oxidative stress induce Nrf2 to increase production of heat shock proteins which regulate oxidative damage, transcription of Nrf2 is also upregulated to attenuates inflammation induced by NF-κB, AMPK upregulates genes through PGC-1α to prevent sarcopenia and induce lipolysis, and the sirtuin family attenuates inflammation, and oxidative stress. This molecular melody is the complex composition that explains the cellular adaption that occurs to strengthen the body from cognitive dysfunction, cardiometabolic failure and carcinogenic implantation and metastasis via mechanisms of redox equilibrium, oxidative protection, attenuation of inflammation, and attenuation of carcinogenic proliferation and growth. Before we go into detail on the cellular level, we will take a look at whole-organism physical exercise.

In 1943, Southam and Ehrlich coined the word “hormesis,” from the Greek word “hormaein” which means to excite, stimulate or spur into action [33]. Southam and Ehrlich [33] described a biphasic dose-response curve where modest stimulatory effects cause hyperplasia or cell metabolism, whereas high doses may overwhelm and inhibit natural defenses leading to irreparable injury [34]. The first scientific study to demonstrate this biphasic phenomenon was a study on yeast metabolism in Germany by scientist Hugo Schulz in the late 19th century [35] where yeast metabolism improved upon low doses of disinfectant but was inhibited at high levels of disinfectant [35].

How can we perform cellular exercise? Research shows that physical exercise and chronic caloric restriction are two pillars on which we can prevent disease-related mortality.

B. Physical Exercise

Exercise is a powerful positive factor in modern health. While there are possible negative consequences of exercise, such as injury, there are incredible benefits to be gained. Exercise is part of our complete well-being; the following studies provide examples of mental, psychological and physical benefits of exercise. Regular physical exercise can improve glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, more so than the effects produced by pharmaceutical intervention [36]. In fact, obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases prevention and reduction with physical exercise has been demonstrated time and again.

Many different types of physical exercise- resistance, endurance, and concurrent resistance and endurance training all have distinctive but protective effects on the body, creating cellular change on the molecular level that prevents cardiometabolic disease and cancer.

Resistance training has been shown to improve anxiety symptoms in both healthy patients and those with physical or mental illness [37]. Resistance exercise counteracts loss of muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in patients suffering from prostate cancer and side effects from treatment [38]. Specific improved measurements observed in the prostate cancer study include: body composition (body fat percentage 95% CI [−0.79, −0.53] %; p < 0.001, lean body mass 95% CI [0.15, 1.84] %; p = 0.028, and trunk fat mass 95% CI [−0.73, −0.08] kg; p = 0.024) [37]. In fact, physical exercise has been shown to reduce cancer incidence and inhibit tumor growth by a direct effect on tumor-intrinsic factors, alleviation of cancer-related adverse events, and improvement of anti-cancer treatment efficacy [39].

Endurance exercise creates upregulation of oxidative pathways that lead to increased creation of mitochondrial capacity through mechanisms of mitochondrial biogenesis, described in detail in the latter part of this paper [40]. Compared with those who develop obesity and diabetes, who have developed insulin resistance as part of a metabolic inflexibility, endurance athletes who have trained their skeletal muscles with physical exercise demonstrated higher mitochondrial capacity and enhanced metabolic flexibility, preventing insulin resistance [41]. During physical exercise, the skeletal muscle utilizes glucose via insulin independent mechanisms, which lowers blood glucose in insulin resistant populations [42]. In a study with 161 individuals with Type 2 Diabetes who had nine months of exercise training, all showed significant improvements in HbA1c, waist circumference and body fat percentage [43]. In the Studies Targeting Risk Reduction Interventions through Defined Exercise (STRRIDE) trial, aerobic exercise training increased insulin sensitivity and VO2 peak [42, 44]. There also have been studies where a dose-response relationship has been demonstrated between physical exercise and reduction in blood pressure [44, 45] and inflammation [44, 46].

Combined resistance and aerobic training has shown to be most beneficial for glycemic control in those with Type 2 Diabetes [44, 47]. Mixed resistance and aerobic exercise is shown to improve cognitive function in adults aged > 50 years [48]. In a recent study in adolescent population with similar caloric intake concluded that the primary determinants of body composition and weight were the amount of physical exercise, daily energy expenditure and the basal metabolic rate expressed by body weight, which had a stronger correlation that macronutrient daily intake [49]. Concurrent training of strength and aerobic training have shown to have even more efficacious results increasing O2max and explosive strength in prepubescents [50]. Protein synthesis is important in regenerating unhealthy or necrosed tissue such as repairing the cardiac muscle after a myocardial infarction. Molecular pathways of protein synthesis help to regenerate tissue more efficiently and effectively. Enhanced mitochondrial biosynthesis also provides protective attributes to ischemia. An abundance of oxidative pathways prevents cardiovascular and cerebral hypoxia, thereby reducing the incidence of cardiometabolic and cerebral accidents.

Even those with identical DNA are shown to have longer lifespans according to the amount of exercise performed. An example of these benefits is shown in the Finnish twin cohort study [51]. Groups of identical twins with identical DNA were followed according to level of exercise versus all-cause-mortality. The inactive exercise group of twins were shown to have the highest rates of death, while the occasional exercisers had 36% less death and the group with the most exercise had 43% less death [51]. In contrast to the benefits of physical exercise, there is evidence that an inactive lifestyle without exercise can actually be harmful instead [52]. Taking deep vein thrombosis (DVT) as an example, frequent muscular movement throughout the day is the most direct way to prevent this disease [53]. In the same way, the frequency and duration at which our lifestyles are without physical activity may affect the longevity of our lives in the long run. In a research study, prolonged TV watching resulted in doubling the rate of Type 2 Diabetes [54].

As mentioned earlier, exercise is beneficial mentally, socially, and physically. But could these benefits be applied at the cellular level? To conceptualize this, we can use the principle of homeostasis: The body seeks to maintain a state of physiological balance. Exercise disturbs this balance, and the body must then adapt to return to the state of balance. The overload principle states that if the activity is too mild, it will fail to disturb the body’s natural balance. For example, gently clicking the mouse to watch another online video will fail to build sufficient muscle mass. Conversely, if the exercise is too extreme, not only will it disturb the balance, it could also cause damage to the cells and tissues of the body. For example, an athlete could tear the gastrocnemius or the Achilles tendon during exercise, weakening instead of strengthening. During normal exercise, the moderate stress and damage is expressed as a feeling of exhaustion, or perhaps weakness or tightening of muscles. After that period of weakness, the body undergoes a period of rest and repair. Once this is completed, the body is strengthened and better equipped to handle the stress of exercise. This cycle can be repeated, and generally noticeable performance improvements can be observed in as little as a few weeks, but as exercise is normally a dose-response relationship, continued exercise will lead to even more benefits. Each time this cycle occurs, physical changes are made at the cellular level. The specific molecular pathways in which this occurs will be discussed hereafter.

C. Caloric Restriction

Caloric Restriction has been shown to prevent cancer, increase longevity, and prevent metabolic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes [24]. Caloric restriction is defined as a reduction in caloric intake, short of malnutrition, typically about 20–50% reduction compared to ad libitum, which is eating without restriction [24]. Caloric restriction causes a low-dose stress response for the cell which causes a hormetic effect, in which cellular adaptation results in cardiometabolic protection. Methods for caloric restriction can be long-term caloric reduction, intermittent fasting, and other methods- all of which would end in an overall decrease in calories compared to ad libitum. Research shows that consuming less calories and/or fasting with variable frequencies, we can exercise the gluconeogenesis pathway that is normally only used during periods of hunger.

The smiling, energetic and vigorous centenarians of Okinawa, Japan are living testaments to how caloric restriction can lead to longevity [55]. Centenarians appear in approximately 10–20 per 100,000 people in most industrialized countries but as high as 40–50 per 100,000 people in Okinawa, Japan [56]. An autopsy of a “typical” centenarian woman would display absence of coronary artery disease, cancer, stroke with only signs of years of use such as compression fractures of the spine, scoliosis, scarring of the lungs, and amyloidosis in major organ systems [57]. This exceptional longevity has been attributed to low-caloric density, plant-based diet with abundant and consistent physical exercise [20]. Okinawans are known to eat around 1,300 calories a day, and have a concept of hachiwari where eating ends when they are 80% full, instead of 100% [55]. However, caloric restriction has been demonstrated to lead to longevity in more than just one human sub-population. Decades of studies across species- yeast, protozoa, nematodes, insects, fish and mammals have consistently and reproducibly demonstrated that caloric restriction is the only known intervention to prolong lifespan [58, 59]. Modest to significant caloric restriction without starvation in these organisms was demonstrated to extend lifespan by 1.5–3 times the lifespan of an ad libitum eater [60]. In a 20-year longitudinal study on adult rhesus monkeys who were fed a calorically restricted diet and compared to control fed animals, caloric restriction was found to lower the incident of aging-related deaths and pathologies. Rhesus monkeys were chosen as one of the most closely related primates to humans. The Wisconsin National Primate Research Center reported a 50% survival of control-fed monkeys compared to 80% survival of monkeys fed a calorically restricted diet [57]. Therefore, caloric restriction without malnutrition was shown both in a human subpopulation and in a monkey study to consistently reduce age-related mortality and morbidity.

IV. Molecular pathways of Hormesis via Physical Exercise and Caloric Restriction

A. Oxidation

What is happening on the cellular level? The caloric restriction performed an attenuation of age-associated increases in rates of mitochondrial O2 and H2O2 generation [61] and accumulation of oxidative damage [62]. The highest degree of attenuation of oxidative damage occurred in the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle, which are primarily composed of long-lived post-mitotic cells [63]. Caloric restriction was demonstrated to decrease the in-vitro susceptibility of tissues to acute oxidative stress [57]. A reduction in oxidative stress leads to cellular longevity, which may reverse the functional involution of cells, tissues and organisms caused by excess oxidation on biomolecules [64]. One of the most accepted theories in the development of these age-related diseases is the damage accumulation theory [65]. Damage accumulation is thought to be driven by oxidative stress among other processes, causing cellular senescence on the molecular level and disease on the level of the organism as a whole [65].

Dietary restriction can result in a beneficial hormetic stimulus. The “mitohormesis” hypothesis suggests that reactive oxygen species cause beneficial effects at low levels. The hypothesis asserts that ROS escape from the mitochondrial electron transport chain and act as signaling molecules to promote cellular fitness and extend lifespan [66]. The cell undergoes stress, caused by caloric restriction or physical exercise, and these stress-induced increases in reactive oxygen species are thought to activate Nuclear factor erythroid 2, and evoke phase II enzyme-directed improvements in redox equilibrium [34]. Therefore, stress adaptation, or cellular exercise, ultimately results in a stronger, more adaptive, more capable cell.

a). Nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2)

In atherosclerosis pathogenesis, Nuclear factor erythroid 2 has the potential to either transform macrophages into pro- or anti- inflammatory phenotypes [17]. This means that Nrf2 can transform macrophages into harmful, atherosclerosis-causing cells or into macrophages who do not cause inflammation and therefore do not contribute to cardiovascular disease, and instead transform macrophages into a health asset. In this manner, Nrf2 acts as a hormetic-like pathway transcription factor [67]. The concept of hormesis is similar to Nrf2 can provoke a moderate stress response, resulting in health benefits and prolonged lifespan [68], whereas excessive long-term Nrf2 stimulation may lead to pathophysiological outcomes.

A complex and integrated defense mechanism regulated by Nrf2 encodes for the heat shock protein (HSP) family such as heme-oxygenase-1 and HSP 72, thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase and sirtuins [69]. Nrf2 transcriptionally upregulates heme-oxygenase, theioredoxin, and thioredoxin reductase to counteract damaging effects of oxidant and electrophile molecules [69]. In the activation of Nrf2, reactive cysteine residues react with reactive oxygen species or electrophiles to induce conformational changes in a protein called Klech-like ECH associated protein 1 (Keap1) [62]. These conformational changes cause Nrf2 to dissociate and the ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2 is arrested [68]. Then, the dissociated Nrf2 that is now activated binds to the nuclear antioxidant responses elements that promote the transcription of detoxification and the redox equilibrium [62]. This Nrf2 triggered induction of HSP family leads to expression of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant genes, which leads to stablizing redox homeostasis [69]. In this way, a low-level oxidative stress on a cell causes it to strengthen itself by triggering mechanisms that promote its fight against oxidative stress via Nrf2.

Nrf 2 and NF-κB axis regulate the physiological homeostasis of cellular redox status and response to inflammation [69]. The complex mechanism and interplay between these two pathways are still to be discovered. However, the some aspects of the cross-talk between these two pathways have been uncovered. NF-κB, further mechanisms interplaying with this signaling will be discussed, competes with Nrf2 where NF-κB antagonizes Nrf2-induced gene transcription [69]. Inflammatory responses that activate NF-κB, can raise Nrf2 pathways to produce a protective anti-inflammatory response. NF-κB activation can activate small GTPase Rac1, which stimulates induction of Nrf2 which upregulates HO-1 expression, which in turn reduces NF-κB inflammatory response and shifts the cells to a more reducing environment [70]. Thereby, the inflammatory impetus causes a molecular balancing between Nrf2 and NF-κB to ultimately result in decrease of inflammation at the cellular level.

b). Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1)

Insulin-like growth factor is influenced in both directions by the mechanisms of diet and exercise. Caloric restriction decreases activation of IGF-1 causing downstream apoptosis of harmful cancer cell growth, while physical exercise upregulates IGF-1 synthesizing proteins and mitochondrial biosynthesis increasing healthy muscle growth and strengthening vital muscle growth against ischemia.

Chronic caloric restriction inhibits growth of protein synthesis through insulin-like growth factor 1. This receptor, which is activated by insulin postprandially, has a negative effect with chronic caloric restriction or intermittent fasting [71]. Insulin-like growth factor 1 is a nutrient-responsive growth factor that activates two major signaling pathways- Ras/MAPK and PI3K/AKT [71]. The Ras/MAPK pathway leads to promotion of transcription factors that express genes for proliferation and cellular growth [61].

Initiation of PI3K/AKT pathway inhibits harmful cellular growth. Insulin receptor proteins are phosphorylated by IGF-1, which recruits PI3K [71]. PIP3 is then produced, which activates PDK-1, which phosphorylates AKT. AKT then promotes cell survival, disrupts the BCL2-Bad complex, which decreases apoptosis, and also deactivates mTOR, which decreases protein synthesis and inhibits GSK-3, decreasing glucose metabolism [71]. The negative regulation of PI3K-AKT is accomplished by mTOR, which induces insulin receptor serine phosphorylation and degradation [71]. Activation of IGF-1 and systemic glucose is reduced in diets with caloric restriction without malnutrition [72]. Reduction in these growth-promoting, anti-apoptotic pathways inhibits carcinogenic cells that utilize this pathway for proliferation [61]. Carcinogenic motility and migration are also inhibited by inhibition of this pathway caused by caloric restriction or fasting. Cross-talk between IGF-1, integrins, FAK, and RACK1 scaffolding protein, activates Rho-A which leads to actin reorganization and actin/myosin contractility, which is instead inhibited [71]. Chronic caloric restriction would also decrease Insulin-like Growth Factor expression of matrix metalloproteinases, which would cripple invasion of tissue, and decreases stimulation of angiogenesis by downregulating expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and vascular endothelial growth factor [71]. Therefore, through caloric restriction, the cell inhibits certain molecular pathways that can prevent proliferation of harmful growth in cancer cells and these cells become more vulnerable to apoptosis because of the attenuation of IGF-1.

On the contrary, physical exercise activates Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 to induce muscle hypertrophy, protein synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis [50]. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 is activated by mTOR, which is upregulated by AKT through PI3K [50]. Physical exercise promotes glucose uptake, which activates Insulin-like Growth Factor (49org). Signaling via insulin receptor proteins and AKT2 promotes GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane and inhibits GSK3, leading to the activation of glycogen synthase (49org). Insulin-like Growth Receptor also performs a similar function, by inducing glucose uptake in brain and skeletal muscle (49org). Although attenuation of IGF-1 can prevent cancer proliferation, it is the same pathway through which healthy muscle also grows. In fact, muscle regeneration in the myocardium is activated by AKT through this pathway and also modulated by Serum Response Factor (SRF) regulated by muscle ring finger 2 (MuRF)-2 [73].

Not only does physical exercise have a role in protein and muscle synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis, it also acts through IGF-1 to strengthen bone and prevent bone related illness. Mechanical loading signals periosteal bone formation and enhances responsiveness to in vivo mechanical loading in mice [74]. In the embryonic skeleton, IGF-1 and its receptor play a determinant role in the development and acquisition of peak bone mass during postnatal growth in mammals as well [74]. IGF-1 expression up-regulates the PI3K/Akt pathway, thereby increasing osteoblast differentiation [74]. Mice in which the IGF-1 receptor is specifically deleted in mature osteoblasts have a mineralization defect which leads to decreased bone mass and loss of trabecular bone [75]. Physical exercise also co-activates IGF-1 when there is mechanical load to transduce the mechanical stimulus to regulate signaling cascades that involve integrins, the estrogen receptor, and wnt/β-catenin [74].

c). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), PGC-1α

AMP-activated protein kinase also plays a key role in cellular exercise. AMPK activation is regulated by cellular energy deficit, and cellular stresses that deplete ATP or increase the AMP/ATP ratio such as glucose deprivation or oxidative stress also activate AMPK [76]. AMPK is activated in circumstances of both chronic caloric restriction and physical exercise, through the mechanism of cellular energy deficit. AMPK is a molecular sensor that increases catabolism and inhibits anabolic metabolism, which works in opposition to IGF-1 activation of mTOR [77]. AMPK activation acts to conserve ATP by inhibiting anabolic pathways (76). In skeletal muscle, acute AMPK activation suppresses glycogen synthesis and protein synthesis, and promotes glucose transport and lipid metabolism [76]. AMPK induces expression of Sirtuin1, a family of metabolic control genes, resulting in a downstream increased fatty acid oxidation and glutaminolysis [78]. AMPK is induced by caloric restriction or physical exercise increases apoptosis in brain tumors while protecting normal cells from stress [79]. Hence, AMPK amplifies catabolic processes and enhances Sirtuin 1, which is the cell “strengthening” which is exhibited downstream as apoptosis of brain tumors and protection of normal cells from stress.

Endurance exercise induces transcriptional upregulation of genes through AMPK and calcium signaling through transcriptional co-activator PGC-1α [80]. Evidence toward the multiplicative and enhancing of mitochondria caused by physical exercise is demonstrated in muscle-specific knockout of AMPK resulting in impaired exercise capacity and dysfunctional mitochondria [40].

Exercise-induced AMPK activation is accompanied by an increase in PGC-1α protein [40]. PGC-1α enhances oxidative mitochondrial transcription for electron transport chain proteins, mitochondrial genome-encoded genes and mtDNA replication [81]. Chronic AMPK activation alters metabolic gene expression and induces mitochondrial biogenesis through modulation of DNA binding activity of transcription factors NRF-1, MEF2, and HDACs [82]. Specifically, AMPK is activated by Apelin, a protein secreted from muscle during physical exercise. Apelin was found to prevent age-associated sarcopenia and increased insulin action in overweight males [83].

Skeletal muscle also releases Interleukin-6 during physical exercise, which stimulates lipolysis and has been shown to reduce visceral adipose tissue mass [84]. In the presence of IL-6 blockade using tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor antibody), the effect of exercise reducing visceral adipose tissue mass was abolished [84]. Thus, IL-6 is required for exercise to reduce visceral adipose tissue mass [84].

In pregnant mothers who are obese, PGC-1α is hypermethylated at CpG-260, which causes reduced mRNA expression and eventual early onset insulin resistance in offspring [85]. In contrast, pregnant mothers who exercise can completely prevent PGC-1α hypermethylation, thereby preventing early onset age-dependent insulin resistance in offspring skeletal muscle [85]. Thereby, physical exercise induces AMPK activation and PGC-1α, enhancing mitochondrial adaptation and preventing age-associated sarcopenia and insulin resistance in the parent and even has the power to affect the offspring as well.

Molecular pathways of both strength and endurance training seem to show similar or enhanced signaling converging on the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivators (PGC-1α) [86]. Using short-term concurrent training is the most favorable method to use as it avoids interference of muscle hypertrophy [87]. It is important to circumvent interference caused by long-term concurrent training of strength and endurance exercise wherein endurance exercise promotes AMPK activation and activates REDD1 which downregulates protein synthesis and inhibits anabolism induced by resistance exercise [88]. In essence, AMPK activation is triggered by cellular energy deficits such as chronic caloric restriction and cellular stresses such as physical exercise to induce gene expression that is favorable to cell longevity, and thereafter longevity of life via protection from cardiovascular disease and cancer.

d). Sirtuins and Nuclear factor Kappa B (NF-κB)

Sirtuins are a group of NAD+-dependent enzymes involved in regulation of apoptosis, cell differentiation, DNA repair, energy transduction, inflammation, and neuroprotection [89]. Caloric restriction attenuates the expression of transcription factor NF-κB through the overexpression of SIRT6, a member of the sirtuin family of NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases [90]. In a rodent study, cultured cells from mice with caloric restriction showed resistance to cell senescence and enhanced SIRT6 expression compared to normal mice [32]. This SIRT6 overexpression was demonstrated to delay replicative senescence by attenuating NF-κB, while SIRT6 knockdown results in accelerated cell senescence and overactive NF-κB signaling. The NF-κB attenuation explains one pathway through which caloric restriction leads to longevity and decreased mortality. During contraction, skeletal muscle generate ROS through superoxides, which then activate MAPK signaling and NF-κB [76]. As aforementioned, NF-κB plays a key role in inflammation, and consequent atherosclerosis and mortality [19]. Therefore, caloric restriction and physical exercise causes SIRT6 upregulation, leading to attenuation of NF-κB, inflammation, and thus prevents atherosclerosis. Anti-inflammatory drugs, specifically IL-1 antagonists demonstrate improved β-cell function and glycemia in prevention of cardiovascular disease and heart failure.

Physical exercise and dietary restriction also activate SIRT1 [55], which amplifies anti-atherosclerotic effects of SIRT6 and is also demonstrated to lower glucose in diabetics [56]. In addition, caloric restriction and physical exercise also induce neuronal expression of SIRT3, which hyperacetylated mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 and cyclophilin D, resulting in healthful changes in oxidation, excitotoxicity, and bioenergy [57]. The deacetylase activity of SIRT1 and SIRT3 on lysine residues and mitochondrial enzymes allows the coupling of alterations in the cellular redox state to the adaptive changes in gene expression and cellular metabolism [76]. In a study comparing athletes and physically inactive constituents, a higher content of SIRT3 proteins were found (90). SIRT3 proteins were found to deacetylate acyl-CoA dehydrogenase to control metabolism of fatty acids as well as deacetylate FOXO1 to increase the expression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) [91]. The activity of SIRT3 is to carry out antioxidant function by deacetylation of MnSOD [92]. A high fat diet was found to alter this pathway by modifying the acetylation of MnSOD in the hippocampus to increase levels of oxidative stress, whereas aerobic interval training attenuated oxidative stress levels and decreased neuronal apoptosis and improved cognitive function [93]. SIRT activity is associated with adaptive skeletal muscle metabolism, enhanced exercise performance and protection against obesity [94].

The resulting inflammation mitigation, lowered glucose levels, DNA repair and delay in cell senescence links why caloric restriction and physical exercise can lead to cellular exercise and resulting cell resilience and longevity. Figure 1 shows the molecular pathways in which caloric restriction and physical exercise trigger sirtulin overexpression which ultimately results in anti-aging properties such as the decreased organ damage seen in Okinawan centenarians and the rhesus monkey study [64, 65].

Figure 1. Cellular Exercise:

The Molecular Pathways of Caloric Restriction and Physical Exercise

Figure 1 shows the mechanisms whereby Physical Exercise and Fasting (whether Intermittent, Periodic or Mimicking) and Chronic Caloric Restriction without malnutrition are two methods which result in low-calorie intake. Low-calorie intake without malnutrition and physical exercise both induce hormesis, where low levels of stress such as diet deficiency and physical exertion can result in beneficial effects. In this case, these types of hormesis result in “cellular exercise” where the cell can encounter a low-level stress and adapt mechanisms to make them stronger and more resilient. One method starts with caloric restriction resulting in low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), triggering Nuclear factor erythroid 2 (Nrf2) to bind to nuclear antioxidant response elements that enhance detoxification and the redox equilibrium transcription. Nrf2 also transforms macrophages into anti-inflammatory phenotypes that prevent atherosclerotic changes. Another pathway affected by caloric restriction is the inhibition of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1). Inhibition of IGF-1 thereby curtails its activation of Ras/MAPK, intercepting growth promoting pathways that carcinogenic cells use to proliferate. Inhibition of IGF-1 also suppresses the BCL2-Bad complex, mTOR activation, resulting in hinderance of carcinogenic protein synthesis and promotion of GSK-3β, which in turn increases glucose metabolism. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is enhanced in caloric restriction, enhancing the inhibition of IGF-1, while upregulating the expression of Sirtuin 1. The sirtuins (SIRT) are NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases activated by caloric restriction and physical exercise. SIRT1 is enhanced thereby promoting SIRT6, and lower glucose and increase fatty acid oxidation in diabetics. SIRT6 is overexpressed, contributing to attenuation of NF-κB signaling, resulting in delay of cell senescence and mitigation of inflammation, and thereby prevention of atherosclerosis. SIRT3 hyperacetylates mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 and cyclophilin D, resulting in healthful changes in oxidation, excitotoxicity, and bioenergy. The NLRP3 inflammasome, through the SIRT3-mediated control, attenuates the inflammasome associated with metabolic dysfunction [20]. A polyunsaturated fat diet also decreased inflammation in the liver, gained less lipid and more protein upon refeeding, gained a lower amount of visceral and epididymal white adipose tissue and increased interscapular brown adipose tissue [20]. Therefore, caloric restriction and physical exercise, results in upregulation of Nrf-2, AMPK, and Sirtuins and downregulation of IGF-1 resulting in an increase in stress resistance, promoting “cellular exercise,” ultimately decreasing age-related morbidity and mortality like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Recent research has shown that caloric restriction leads to potential beneficial effects, protecting the body from cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases [95]. How does it do so? Low-level stresses produce downstream molecular effects “exercising” the cell to upregulate AMPK and sirtuins while downregulating IGF-1 and NF-κB to create protective tolerance to reactive oxygen species and apoptosis [96]. Armoring the cell to recognize and cause apoptosis if the DNA is dysregulated, and at the same time, protecting the cell to be strengthened against becoming oxidatively damaged in normal states. There is increasing evidence that superoxide, among the most abundant reactive oxygen species (ROS) of mitochondria, is not only apoptotic, but also may play an important role in cellular signaling and in the regulation of beneficial gene expression. Accordingly, the cell becomes stronger by “cellular exercise” undergone by hormetic stresses and can protect against DNA damage and metabolic syndrome.

B. Caloric Restriction and Intermittent Fasting

With our concept of three meals a day, snacks in between and dessert on top – we may be failing to exercise the energy breakdown cycle on a cellular level. That means our bodies don’t get a break when it comes to storing food as energy. And our bodies need that break to start breaking down fat stores. Specifically, this involves the breakdown of fat into acetyl-coA, which is turned into ATP through the Krebs cycle. It also involves gluconeogenesis, the process of generating new glucose molecules out of constituent parts so the body can use it as energy. This process is also mediated by hormones such as increased glucagon levels and lowered insulin levels, which in the long term, will decrease the incidence of the development of diabetes and thereof reduce morbidity.

Research on fasting studies in rodent models can be broken down into 2 main groups: intermittent fasting (IF) and periodic fasting (PF) [97]. Intermittent fasting involves little to no calories over a 24-hour period followed by 24–48 hours of normal diet [97]. Periodic fasting involves little to no calories over a 48-hour period, followed by a normal diet for at least a week before starting another fast (96). Researchers knew that a complete fasting diet would be difficult to maintain for the population, so they devised a diet that mimicked fasting. This diet, called the Fasting Mimicking Diet (FMD), used a low-protein, low-carb, high-fat content diet of only 10–50% of the normal daily calories and had similar results to a periodic fasting diet [98]. Cancer incidence was found lowered by 45% in these trials (97). Subjects that were positive for cancer had less metastasis. A study compared fasting rodents on fasting cycles of 1 day in 4, 1 day in 3, and 1 day in 2 [98]. The optimal results showed fasting of 1 day in 3, which increased lifespan by 15–20% [98]. A 4-day fasting mimicking diet could induce metabolic changes similar to those caused by prolonged fasting and reduce insulin and glucose levels [99]. In fact, fasting mimicking diet rescued mice from late stage Type 2 Diabetes by restoring insulin secretion and reducing insulin resistance, leading to increased survival rate [100]. Nonetheless, a review of all relevant clinical trials assessing both chronic calorie restriction (CR) in the 20–50% range and intermittent fasting (IF), concludes that CR is superior in causing loss of body weight compared to IF, but both interventions have similar effects on the reduction of visceral fat, insulin and insulin resistance [98–101]. If our breakfasts really did involve “breaking a fast” of at least 12–16 hours, like the aforementioned fasting mimicking diet, it could make a great difference in longevity and quality of life. This new field of research is showing great promise [98–101]. A 2013 study measured weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers in Intermittent fasting involves little to no calories over a 24-hour period followed by 24–48 hours of normal diet, while periodic fasting involves little to no calories over a 48-hour period overweight women using intermittent energy and carbohydrate restriction versus daily energy restriction and found that in the short term, intermittent energy restriction has improved insulin sensitivity and body fat reduction [101]. Even with refeeding ad libitum, there remains some lasting beneficial effects of lowering glucose and decreasing inflammation. Perhaps, side by side with physical exercise, we need to practice cellular exercise to achieve optimal health.

V. Comparative Synthesis of Different Diets

Overall, the current research concludes that eating less- ranging from 60–80% of our ad libitum diet- whether it be through the method of Intermittent fasting or caloric restriction in general-decreases mortality [66]. Composition of diet has also been a controversial topic with diverse results.

A. Caloric Restriction

In the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term effects of reducing intake of energy (CALERIE) study, two years of sustained 25% caloric restriction demonstrated protection against age-related cardiovascular disease risk, insulin sensitivity and secretion, immune function, neuroendocrine function and quality of life [102, 103].

B. High Protein Diet

1. High Animal Protein Diet (Atkins Diet, Paleo Diet)

In short-term randomized controlled trials, low carbohydrates with relatively higher protein diets have demonstrated weight loss, decreased blood pressure, improved cardiac biomarkers such as blood lipid and lipoprotein levels as well as glucose regulation [103]. However, this evidence has been contradicted in other studies, such as this one [104]. In this study, short-term hypocaloric high-protein diets lead to negative results in metabolic and inflammation/muscle-damage indices.

2. High Plant Protein Diet

When comparing animal protein to plant protein, mortality was positively associated with animal protein intake, whereas plant protein was inversely related [105]. When animal protein was replaced with plant protein, mortality was also lowered. Interestingly, less animal protein compared to plant protein is weakly associated with increased longevity. Also, less protein overall benefits middle aged individuals [105]. To that effect, middle aged participants (50–65 years old) with high protein intake had a significant 75% increase in overall mortality and a 4-fold increase in cancer death risk during the following 18 years. These alarming associations were either eliminated or weakened when the proteins were plant derived. On the contrary, after the age of 65, a high protein diet was associated with reduced cancer and overall mortality. Nevertheless, high protein intake leads to a 5-fold increase in diabetes mortality across all ages. Accordingly, a progressive increase from low to moderate protein intake from middle to older age seems to optimize health span and longevity [105].

C. DASH

In the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, 459 adults were divided into three groups- one control, one fruit and vegetable diet, and one “combination DASH diet” composed of high vegetable, fruits, low-fat fermented dairy products, whole grains, poultry, fish and nuts, were compared. Eight weeks later, it was found that the combination of low-fat, fruit and vegetables lowered hypertension the most dramatically [106]. The fruits-and-vegetables diet reduced systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 2.8 mmHg (p < 0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) by 3 mmHg (p = 0.007); while the combination diet reduced SBP by 5.5 mmHg and DBP 3 mmHg [107]. Among participants with established hypertension, the combination diet reduced even more efficaciously, SBP reduced 11.4 mmHg and DBP reduced by 5.5 mmHg compared to controls (p < 0.001 each) [106]. The combination diet was also found to reduce total cholesterol by 13.7 mg/dL and LDL by 10.7 mg/dL (p < 0.001 each) [108].

D. Mediterranean Diet

The wide difference in cardiovascular disease prevalence between Mediterranean populations and western countries prompted Ancel Keys, American biologist to point to the Mediterranean diet [109]. The Mediterranean Diet (MED) is a dietary pattern rich in whole grains, fruit, vegetables, low in meat, with a considerable amount of monounsaturated fat derived from olive oil and nuts (108). In a large population based prospective study on 22,043 Greeks enrolled in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), where a higher adherence to the MED diet was associated with a 25% increase in overall survival every 2 points increase on the MED score (p < 0.001), which was associated with mortality from coronary artery disease (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.47–0.94) and cancer (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.98) [110].

E. Okinawan Diet

Okinawa is a chain of islands on the southern tip of Japan, where the subpopulation there has an extraordinary longevity in their lifespan, even compared to their Japanese cohorts [55]. Okinawans eat hachiwari, which means 80% in Japanese, where they finish their meal after they are 80% full, but not yet completely full [56]. Their diets are, on average, around 1,300 calories/day. The composition of their meals consists of many vegetables with low levels of lean protein, fruit, sugar and saturated fats. Their combination of overall caloric restriction with this diet may make Okinawans the overall most long-lived sub-population of the modern day.

F. Discussion of Diets

In the CALERIE study sustained 25% caloric restriction demonstrated protection against age-related cardiovascular disease risk, insulin, and immune function. Fasting diets demonstrate lowered insulin levels and decreased cancer incidence [98–101]. The high protein diet, especially proteins resulting from plants instead of animals, as well as the DASH diet of low-fat fruits and vegetables both exhibit weight loss, and lowered blood lipid and lipoprotein levels [105–108]. The Mediterranean Diet, rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, low in meat with monounsaturated fat results in an increase in overall survival associated with decreases in coronary artery disease and cancer [109, 110]. The Okinawan diet is composed of many vegetables with low levels of lean protein, fruit, sugar and saturated fats, with an overall low caloric intake resulting in Okinawans being one of the most long-lived sub-population of the modern era [111]. All in all, the resounding similarity of the different diets throughout is that a diet rich in vegetables, fiber, plant protein, and low in saturated fat and animal protein is beneficial to cardiovascular health. In parallel, an overall caloric intake that is moderately lower than ad libitum without malnutrition is also demonstrably beneficial to lowering cardiovascular disease risk, cancer, and overall mortality.

VI. Diet and the immune system

Similar to any other cell in the body, an immune cell’s health and function is highly affected by the nutrient a body receives through its diet. For example, certain dietary plans may increase the body’s ability to defend itself against microbial attacks or excess inflammation. A healthy and optimally functioning immune system is crucial in fighting off infections, including viral infections like COVID-19. Nevertheless, these immune reactions cannot be attributed to a single type of food, rather to a cocktail of micronutrients from a well varied diet. Some of the vital nutrients involved in the growth of immune cells include vitamins like C and D, some metals like zinc and iron, and proteins like the amino acid glutamine [112, 113].

Another key micronutrient found in Mediterranean and Okinawan diets is the omega-3 fatty acids which are polyunsaturated fatty acids including EPA and DHA that have immunomodulatory effects, and can promote optimal immune support. There is a severe lack of omega-3 fatty acids in the Western diet, which is noted to have high levels of omega-6 fatty acids as opposed to omega-3 fatty acids. This disproportionate ratio has been linked with the pathogenesis of multiple diseases that include inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [114]. The effects of omega-3 have recently been studied in patients with COVID-19, a virus which causes multi-organ inflammation, and supplementation showed some positive improvement in respiratory and renal function in these patients [115]. These nutrients can be found in animal and plant-based foods. With the trend of highly limited diets being based on ultra-processed foods, many nutrients are being foregone, in turn negatively affecting the immune system. In fact, chronic gut inflammation and reduced immunity can be traced back to a Western diet filled with refined sugars and red meats while bearing a low capacity of fruits and vegetables [116].

Human intestines are home to over a trillion microorganisms that flourish in an environment we call the microbiome. This heavily researched area has scientists claiming that the body’s immune functions are highly dependent on a healthy microbiome since most antimicrobial proteins are produced there [117, 118]. Given that a microbiome feeds directly from the food we eat, it can be expected that a healthy diet plays an integral role in the health of a microbiome. A plant-based diet with a high fiber content tends to aid in the growth and support of beneficial microbes. These fibers, also called prebiotics, can be broken down into short fatty acid chains with the help of some microbes, thus allowing for the stimulation of the immune system. Similar to the prebiotics, probiotics help the gastric microbiome by injecting helpful bacteria in the mix. Probiotic foods include Kefir, kimchi, and miso, while prebiotic foods include garlic, onions, and bananas. Nevertheless, eating a variety of fruits and vegetables along with beans and whole grains can be a general rule for a prebiotic diet [119].

Just as expected in all forms of life, an active state requires more energy than a passive state. Similarly, an active immune system defending against an infection requires a greater basal energy spending and thus optimal nutrition is required to sustain this activity. The best nutrition in this case would target immune cells and supplement them with all required nutrients to shorten the recovery period. When the body’s exogenous energy source, the diet, gets depleted, it moves to use body stores, also known as the body’s endogenous energy source. For that reason, it is important to constantly supply the body with dietary sources full of micronutrients which support the immune system to store as its endogenous energy source [120]. When the body runs out of energy sources, it suddenly loses the ability to support its immune system which is overworked compared to other systems during infections. For that reason, undernutrition is considered to impair immune functions. The immune system impairment is also affected by the subject’s age, and whether or not there are nutrient interactions to consider [121].

Some nutrients can play multiple roles that affect the immune system. For example, Vitamin E acts as an antioxidant, a protein kinase C activity inhibitor, with a potential to interact with enzymes and transport proteins. On the other hand, an over consumption of micronutrients can be detrimental to the body’s immune responses. In fact, subjects in malaria endemic regions can face increased morbidity and mortality with high supplements of iron [122].

VII. Relation between Diet, Sleep and Cardiovascular Diseases

The relation between Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease is a subtle but relevant one. Epidemiological studies have shown that a Mediterranean diet (which includes a high intake of fruits and vegetables, up to 7–10 servings/day, along with a preference to unsaturated fats rather than saturated fats) encourages healthier sleep and may thus reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease through changes in tryptophan intakes. In fact, a diet rich in plant foods - which are rich in tryptophan, which in turn are a precursor to melatonin and serotonin - helps induce longer and better sleep. The improved sleep quality and duration act to reduce cardiovascular disease [123]. According to a study by Noorwali et al. in 2018 [124], people sleeping less than 7h/night (short sleepers) usually consume less fruits and vegetables and more saturated fats than people who sleep longer (adequate sleepers). For instance, the study reveals a 12% increase in the intake of fruits in adequate sleepers compared to short sleepers [124]. Another research done by Al Khatib et al. in 2017 [125] conducted a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled sleep restriction studies showed that partially sleep-deprived individuals (sleeping between 3.75 and 5.5 hours a night) consume an average of 385 kcal/day compared to adequate sleepers. This increase can be linked to a higher frequency of consuming fatty snacks [125]. In 2011, Jaussent et al. [126] were the first to study the correlation of a Mediterranean diet and sleep outcomes. Results showed an approximate reduction of 20% of self-reported insomnia symptoms in women, but not in men [126]. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) later verified those findings in 2018, indicating a lower probability of experiencing insomnia symptoms when adhering to a Mediterranean diet. The MESA study was also the first to objectively measure a link between sleep duration and a Mediterranean diet by showing a 43% higher chance of achieving 6–7 hours of sleep/night rather than 6 hours/night [124].

VIII. Conclusion

Our review concludes that longevity can be increased through moderation of diet and exercise. Research shows that a concoction of the diverse diets modernly popularized- Mediterranean diet, DASH, High-Protein Diets- tempered by overall caloric restriction through periodic fasting or chronic caloric restriction will provide protection against cardiovascular disease, cancer and aging. Exercise has also shown to increase longevity in the general population, can lower incidence of diabetes and cancer, and has psychological benefits.

Nutritional discipline and dietary restriction results in resistance exercise for our cells. Triggered by caloric restriction or physical exercise, our cells end up producing transcription factors that lead to protection against oxidation, inflammation, atherosclerosis, and carcinogenic proliferation. In the long term, this results in longevity and a decrease in cancer, Type II Diabetes Mellitus, myocardial infarction, and stroke. Since centuries past, studies on humans, rhesus monkeys, and multi-level organisms have demonstrated the benefits of caloric restriction without malnutrition. Periodic fasting and caloric restriction show increases in regeneration markers and decreases in biomarkers for diabetes, CVD, cancer and aging.

The review of research indicate that incorporating a moderate caloric restriction or fasting regimen could provide substantial benefits at low risk. Cellular exercise through caloric restriction and physical exercise can increase longevity and prevent the greatest killers of human society today – stroke and heart disease.

IX. Future Studies

Future studies that can more accurately define the boundaries of hormesis – at what point does exercise begin to be more harmful than beneficial – will help us better define guidelines for exercise recommendations. A molecular and physiological approach for the mechanisms underlaying hormesis and exercise will definitely be of future reaserch importance that will reflect on our clinical guidance for healthy living and treatment of obesity. Cellular exercise is also a complex topic with many molecules currently being researched. For example, ROS were previously seen as only damaging, but now are understood to be important for signaling within myocytes. Thus, ROS are known to be both destructive and useful, depending on the specific circumstances and amounts. As we better understand these molecular interactions, we will be able to more accurately assess whether our patients are at the correct level of nutrition and exercise.

Figure 2.

Intermittent fasting alternates days of eating and fasting on a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio, while periodic fasting follows a 2:7 ratio.

Graph 1:

A comparative graph between the atherosclerosis pathway in humans versus rodents.

Highlights.

Poor dietary choices and physical inactivity are the heart of to the leading causes of death in the world, namely stroke, heart disease, and cancer. Chronic overnutrition triggers can lead to diabetes, atherosclerosis, and hypertension through mechanisms triggered by chronic glycemic and lipid overload. In the same way physical inactivity is harmful to health, physical exercise can trigger molecular pathways that can lower glucose levels and increase oxidative protection via mitochondrial biogenesis that prevent diabetes and strengthen the body against oxidative damage.

“Cellular Exercise” is a concept where low levels of cellular stress, induced by chronic caloric restriction or physical exercise, can lead to molecular adaptations on the cellular level that can protect the body from cancer and cardiovascular disease.

An increase in reactive oxygen species induced by caloric restriction and physical exercise can activate Nuclear factor erythroid and phase II improvements in redox equilibrium that can result in a more adaptive capable cell. Low levels of oxidative stress induce Nrf2 to increase production of heat shock proteins which regulate oxidative damage. This cellular exercise can attenuate acute oxidative damage that may have led to inflammatory damage leading to atherosclerosis and myocardial damage in the long run.

Insulin-like growth factor 1 has a dual effect wherein caloric restriction downregulates IGF-1 inhibiting pathways of carcinogenic proliferation and metastasis and physical exercise can upregulate IGF-1 to promote mitochondrial biogenesis and protein synthesis thereby strengthening healthy muscle against hypoxic ischemic damage and muscular regenerative properties.

Transcription of Nrf2 is also upregulated to attenuates inflammation induced by NF-κB, AMPK upregulates genes through PGC-1α to prevent sarcopenia and induce lipolysis. The sirtuin family attenuates inflammation and oxidative stress.

This molecular melody is the complex composition that explains the cellular adaption that occurs to strengthen the body from cognitive dysfunction, cardiometabolic failure and carcinogenic implantation and metastasis via mechanisms of redox equilibrium, oxidative protection, attenuation of inflammation, and attenuation of carcinogenic proliferation and growth.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported (in part) by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number G12MD007597. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- [1].Organization WH. The top 10 causes of death. December 9, 2020. ed: W.H.O.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rana JS, Khan SS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Sidney S. Changes in Mortality in Top 10 Causes of Death from 2011 to 2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2517–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Organization WH. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva, Switzerland: W.H.O.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes J 3rd. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease--six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wright JS, Wall HK, Ritchey MD. Million Hearts 2022: Small Steps Are Needed for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. JAMA. 2018;320:1857–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pate RR, O’Neill JR, Lobelo F. The evolving definition of “sedentary”. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36:173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) - Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Steneberg P, Rubins N, Bartoov-Shifman R, Walker MD, Edlund H. The FFA receptor GPR40 links hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and impaired glucose homeostasis in mouse. Cell Metab. 2005;1:245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Burgeiro A, Cerqueira MG, Varela-Rodriguez BM, Nunes S, Neto P, Pereira FC, et al. Glucose and Lipid Dysmetabolism in a Rat Model of Prediabetes Induced by a High-Sucrose Diet. Nutrients. 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lebovitz H Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Medscape. June 14, 2019. ed. New York: Medscape LLC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yurdagul A Jr., Finney AC, Woolard MD, Orr AW. The arterial microenvironment: the where and why of atherosclerosis. Biochem J. 2016;473:1281–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ference BA, Graham I, Tokgozoglu L, Catapano AL. Impact of Lipids on Cardiovascular Health: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1141–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Parthasarathy S, Steinberg D, Witztum JL. The role of oxidized low-density lipoproteins in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Libby P Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:155–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran AC, Johnstone SR, et al. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res. 2010;107:737–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Freigang S, Ampenberger F, Spohn G, Heer S, Shamshiev AT, Kisielow J, et al. Nrf2 is essential for cholesterol crystal-induced inflammasome activation and exacerbation of atherosclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rajamaki K, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Valimaki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Huang Z, Li W, Wang R, Zhang F, Chi Y, Wang D, et al. 7-ketocholesteryl-9-carboxynonanoate induced nuclear factor-kappa B activation in J774A.1 macrophages. Life Sci. 2010;87:651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Huber J, Boechzelt H, Karten B, Surboeck M, Bochkov VN, Binder BR, et al. Oxidized cholesteryl linoleates stimulate endothelial cells to bind monocytes via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bakris GL. Renovascular Hypertension. Cardiovascular Disorders. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corporation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Elena R Ladich RVFK, Fumiyuki Otsuka. Atherosclerosis Pathology. Drugs & Diseases. Kenilworth, NJ: Medscape; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Prevention CfDCa. Safer and Healthier foods. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Bethesda MD: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. p. 905–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Savoca MR, Steffen LM, Bertoni AG, Wagenknecht LE. From Neighborhood to Genome: Three Decades of Nutrition-Related Research from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1881–6 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Rose K, Catellier D, Clark BL, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities S. Neighbourhood characteristics and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Market WF. Our Core Values. Whole Foods Market Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [31].McDonald’s. Nutrition Calculator. About our food. June 13, 2019. ed: McDonald’s Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Calabrese EJ. Hormesis: a fundamental concept in biology. Microb Cell. 2014;1:145–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].EJ SC. Decay Resistance and Physical Characteristics of Wood. Journal of Forestry. 1943;41:666–73. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Leak RK, Calabrese EJ, Kozumbo WJ, Gidday JM, Johnson TE, Mitchell JR, et al. Enhancing and Extending Biological Performance and Resilience. Dose Response. 2018;16:1559325818784501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Calabrese E Hormesis: a revolution in toxicology, risk assessment and medicine. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:S37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Richter LSaEA. Current advances in our understanding of exercise as medicine in metabolic disease. Current Opinion in Physiology. 2019;12:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Lyons M, Herring MP. The Effects of Resistance Exercise Training on Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Med. 2017;47:2521–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Keilani M, Hasenoehrl T, Baumann L, Ristl R, Schwarz M, Marhold M, et al. Effects of resistance exercise in prostate cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:2953–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hojman P, Gehl J, Christensen JF, Pedersen BK. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Exercise to Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Cell Metab. 2018;27:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Drake JC, Wilson RJ, Yan Z. Molecular mechanisms for mitochondrial adaptation to exercise training in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2016;30:13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Methenitis S A Brief Review on Concurrent Training: From Laboratory to the Field. Sports (Basel). 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].AbouAssi H, Slentz CA, Mikus CR, Tanner CJ, Bateman LA, Willis LH, et al. The effects of aerobic, resistance, and combination training on insulin sensitivity and secretion in overweight adults from STRRIDE AT/RT: a randomized trial. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;118:1474–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Pandey A, Swift DL, McGuire DK, Ayers CR, Neeland IJ, Blair SN, et al. Metabolic Effects of Exercise Training Among Fitness-Nonresponsive Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: The HART-D Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sparks LM. Exercise training response heterogeneity: physiological and molecular insights. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Johannsen NM, Swift DL, Johnson WD, Dixit VD, Earnest CP, Blair SN, et al. Effect of different doses of aerobic exercise on total white blood cell (WBC) and WBC subfraction number in postmenopausal women: results from DREW. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boule NG, Wells GA, Prud’homme D, Fortier M, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:357–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KL, Smee DJ, Rattray B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Papadopoulou SK, Feidantsis KG, Hassapidou MN, Methenitis S. The Specific Impact of Nutrition and Physical Activity on Adolescents’ Body Composition and Energy Balance. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2020:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Alves AR, Marta CC, Neiva HP, Izquierdo M, Marques MC. Concurrent Training in Prepubescent Children: The Effects of 8 Weeks of Strength and Aerobic Training on Explosive Strength and V[Combining Dot Above]O2max. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30:2019–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M. Relationship of leisure-time physical activity and mortality: the Finnish twin cohort. JAMA. 1998;279:440–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]