Abstract

Background

Accumulating evidence indicates that behaviors in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias could result in incarceration. Yet, the proportion of persons diagnosed with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) before they were incarcerated is largely unknown. By leveraging a national sample of mid-to late-life adults who were incarcerated, we determined the prevalence of dementia and MCI prior to their incarceration.

Methods

In this current study, participants were Medicare-eligible U.S. veterans who transitioned from incarceration to the community in mid- to late-life from October 1, 2012 to September 30, 2018 after having been incarcerated for ≤10 consecutive years (N=17,962). Medical claims data were used to determine clinical diagnoses of dementia and MCI up to three years before incarceration. Demographics, comorbidities, and duration of incarceration among those with dementia and MCI were compared to those with neither diagnosis.

Results

Participants were >97% male, 65% non-Hispanic White, 30% non-Hispanic Black, and 3.3% had a diagnosis of either dementia (2.5%) or MCI (0.8%) prior to their most recent incarceration. Individuals with MCI or dementia diagnoses were older, were more likely to be non-Hispanic White, had more medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and experienced homelessness and traumatic brain injury at higher rates than those with neither diagnosis. Average duration of incarceration was significantly shorter among those with MCI (201.8 [±248.0] days) or dementia (312.8 [±548.3] days), as compared to those with neither diagnosis (497.0 [±692.7] days) (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

These findings raise awareness of the proportion of incarcerated persons in the US who have a diagnosis of MCI or dementia before they are incarcerated. Improved understanding of pathways linking cognitive impairment to incarceration in mid- to late-life are needed to inform appropriateness of incarceration, optimization of healthcare, and prevention of interpersonal harm in this medically vulnerable population.

Keywords: Dementia, Mild cognitive impairment, Incarceration, Prisoners, Jail

Introduction

On June 26, 2020, Karen Garner, a 73-year-old woman with dementia, was arrested in Loveland, Colorado for alleged shoplifting. During arrest, Ms. Garner sustained a broken arm and dislocated shoulder.1, 2 Ms. Garner’s story exemplifies the growing number of media reports detailing interactions between persons with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (hereafter dementia) and the U.S. justice system.3, 4

Beyond media stories, empirical research indicates dementia is associated with increased likelihood of engaging in law-violating behaviors.5 These behaviors manifest along a severity spectrum, from Ms. Garner’s shopping incident, to violent crimes (e.g., aggravated assault; attempted homicide).6 In a U.S. study of 2,397 persons with dementia, 8.5% had history of criminal behavior consequential to their illness.7 Given increase in the number of those with dementia over the next decade,8 more people will likely engage in dementia-related criminal behaviors. For some, incarceration will result.

Per the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 23% of state and federal prisoners report “cognitive disability”, i.e., “having serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions because of a physical, mental, or emotional problem.”9 This proportion is 30% among jail inmates,10 who likely experience shorter incarcerations. For older incarcerated persons (i.e., age ≥50) in the U.S., between 38% and 70% are estimated to be cognitively impaired.11, 12 Yet, estimates do not distinguish between impairment before incarceration versus cognitive impairment developed during incarceration. Understanding the proportion of incarcerated persons with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which may develop into dementia, prior to incarceration, would inform optimal management (e.g., implementing safety protocols to reduce victimization upon entry) and mitigation (e.g., considering alternate placement). Additionally, determining average duration of incarceration for those with a pre-incarceration MCI or dementia would have important implications for decarceration and/or long-term care planning efforts.

We conducted the first population-based study estimating prevalence of MCI or dementia prior to incarceration. We leveraged a national cohort of U.S. veterans in mid-to-late-life with recent incarceration history and determined the proportion of those with MCI or dementia prior to incarceration and evaluated duration of incarceration.

Methods

Data and Participants

We constructed a national cohort of Medicare-eligible veterans aged ≥50 who transitioned from incarceration to community (i.e., reentry) between 10/1/2012 and 9/30/2018 (N=18,439), with claims data available since 10/01/2000. We then limited the sample to the 98% incarcerated ≤10 years (N=17,962), thereby ensuring at least 3 years of pre-incarceration medical records data available for each reentry veteran. For example, by limiting the sample to those incarcerated for ≤10 years, veterans with the earliest reentry date (10/01/2012) but longest incarceration (10 years), would have pre-incarceration claims data available between 10/01/2000 and 9/30/2002. We then linked CMS data on medical claims, diagnoses, and prison admission/release dates to the VA’s National Patient Care Database (NPCD), which includes all VA in/outpatient services. Participant consent was waived because we analyzed secondary data. This study was approved by the San Francisco VA Health Care System and the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

As done previously by our group, we derived MCI and dementia diagnoses using ICD-9/10 codes in NPCD and CMS claims data13, 14 (Supplemental Table S1). Medical record data assessed demographics (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity); history of 14 (summed) chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, stroke, HIV/AIDS); psychiatric history (e.g., major depression, alcohol use disorder) with serious mental illness (SMI) considered bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or psychotic illness; history of homelessness; and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Duration of incarceration was determined via CMS data.

Statistical Analyses

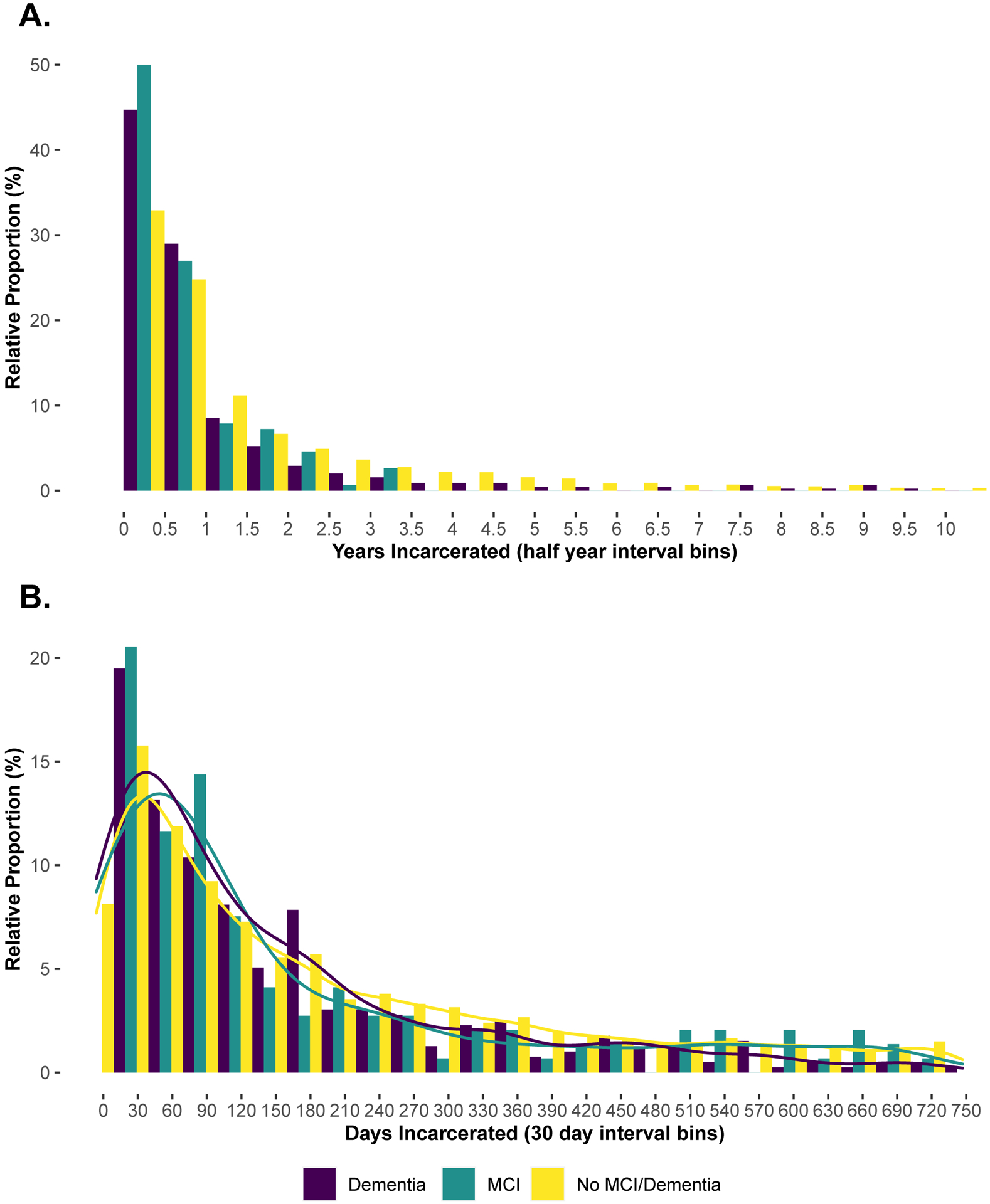

We reported sample characteristics using descriptive statistics, χ2 statistics, t-tests, and ANOVA comparing characteristics of those with versus without MCI or dementia; p <0.05 indicated statistical significance. We plotted distributions of incarceration duration in half-year intervals according to cognitive status. Furthermore, because most (80%) were incarcerated for ≤ 2 years, we plotted distributions of incarceration duration during this timeframe in 30-day intervals according to cognitive status. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and R15 version 4.0.3 to plot duration of incarceration.16, 17

Results

Overall, 597 (3.3%) veterans had MCI or dementia before most recent incarceration (MCI=152 [25.5%]; dementia=445 [74.5%]), prevalence 0.8% and 2.5%, respectively. Those with either diagnosis were mostly non-Hispanic White. Within racial groups, 1.0% of non-Hispanic Whites had MCI before incarceration. Proportion of dementia before incarceration was 2.7% in non-Hispanic Whites and 2.0% in non-Hispanic Blacks. Small numbers precluded presenting MCI percentages for other race/ethnicity categories (Table 1). Compared to veterans without either diagnosis, those with pre-incarceration MCI or dementia were older at incarceration start date (65.4 [±8.0] and 66.4 [±8.4] versus 62.3 [±7.6]), had, on average, more chronic medical conditions (3.1 [±1.9] and 3.9 [±2.1] versus 2.2 [±1.9]), experienced higher homelessness rates (18.4% and 22.7% versus 7.8%), and more had history of TBI (26.3% and 23.8% vs. 9.1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of reentry veterans in the 3 years prior to their most recent incarceration according to Dementia/MCI status (N=17,962)

| Characteristics n (%) or mean (SD) | No Dementia/MCI before most recent incarceration (N=17,365) | Dementiaa before most recent incarceration (N=445) | MCI before most recent incarceration (N=152) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at start date of most recent incarceration, years, mean (SD) | 62.32 (7.59) | 66.36 (8.36) | 65.36 (8.04) | <0.001 |

| Duration of incarceration, days, mean (SD) | 497.02 (692.66) | 312.78 (548.29) | 201.81 (248.04) | <0.001 |

| Duration of incarceration, days, mean (SD) (<= 2 years) | 193.80 (186.27) | 150.86 (155.61) | 168.40 (186.60) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 16,877 (97.2) | 434 (97.5) | 150 (98.7) | 0.494 |

| Race | 0.002 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 11,330 (65.3) | 323 (72.6) | 111 (73.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5,296 (30.5) | 110 (24.7) | …b | |

| Hispanic/Others | 739 (4.3) | 12 (2.7) | … | |

| Homelessness before most recent incarceration (within 3 years) | 1,355 (7.8) | 101 (22.7) | 28 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| Medical conditions before most recent incarceration (within 3 years) | ||||

| Hypertension | 9,823 (56.6) | 371 (83.4) | 125 (82.2) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,400 (8.1) | 92 (20.7) | 28 (18.4) | <0.001 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1,367 (7.9) | 93 (20.9) | 24 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1,779 (10.2) | 168 (37.8) | 35 (23.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4,202 (24.2) | 220 (49.4) | 56 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| Arthritis | 288 (1.7) | … | … | 0.608 |

| Hip fracture | 224 (1.3) | 31 (7.0) | … | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 4,573 (26.3) | 197 (44.3) | 54 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 1,515 (8.7) | 70 (15.7) | 23 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 1,336 (7.7) | 75 (16.9) | 34 (22.4) | <0.001 |

| HIV/AIDS | 352 (2.0) | 16 (3.6) | … | 0.007 |

| Hepatitis C | 2,220 (12.8) | 80 (18.0) | 24 (15.8) | 0.003 |

| Sexually transmitted disease | 227 (1.3) | 11 (2.5) | … | 0.013 |

| Tobacco dependence | 7,978 (45.9) | 297 (66.7) | 94 (61.8) | <0.001 |

| Sum of above 14 chronic medical conditions, mean (SD) | 2.15 (1.85) | 3.89 (2.10) | 3.10 (1.88) | <0.001 |

| Traumatic Brain Injury | 1,571 (9.1) | 106 (23.8) | 40 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric conditions before most recent incarceration (within 3 years) | ||||

| Major depression | 3,259 (18.8) | 168 (37.8) | 64 (42.1) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2,827 (16.3) | 144 (32.4) | 43 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 3,515 (20.2) | 133 (29.9) | 46 (30.3) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 6,472 (37.3) | 264 (59.3) | 93 (61.2) | <0.001 |

| Drug Use Disorder | 6,287 (36.2) | 223 (50.1) | 85 (55.9) | <0.001 |

| Schizophreniac | 2,317 (13.3) | 140 (31.5) | 32 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Psychotic Illnessesd | 2,100 (12.1) | 150 (33.7) | 25 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Any Serious Mental Illness (schizophrenia, bipolar, or psychotic illness) | 4,111 (23.7) | 214 (48.1) | 56 (35.3) | <0.001 |

Dementia includes Alzheimer’s disease, Frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, mixed dementia, presenile, senile and not otherwise specified dementia, alcohol/drug-induced persistent dementia, Pick’s disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Prion disease.

Ellipses, individual cell count too small to report based on data use agreement, but for medical conditions individual cell counts included in sum of 14

Schizophrenia includes schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (ICD-9 codes: 295.0–295.4 and 295.6–295.9; ICD-10 codes: F20.0, F20.1, F20.2, F20.5, F20.9, F20.89, and F25).

Psychotic illnesses include ICD-9 codes 297.1 (delusional), 295.9 (unspecified schizophrenia), 295.7 (schizoaffective), 295.4 (schizophreniform), 293.81 and 293.82 (psychosis due to medical condition); ICD-10 codes F28 (Other psychotic disorder), F29 (Unspecified psychosis), and F20.81 (Schizophreniform disorder).

Additionally, those with pre-incarceration MCI or dementia had greater prevalence of each psychiatric condition, and pre-incarceration prevalence of SMI was 35.3% in those with MCI and 48.1% in those with dementia versus 23.7% in those without either diagnosis (Table 1). Considering that percentages of several conditions were markedly higher among those with dementia versus MCI (i.e., congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, chronic lung disease, TBI, psychotic disorders, and SMI) we ran post-hoc analyses to explore differences. Dementia was associated with having a history of stroke, diabetes, psychotic disorders, and SMI (all P < 0.01).

Average duration of incarceration (days) was significantly shorter among veterans with MCI (201.8 [±248.0]) or dementia (312.8 [±548.3]), compared to those without these diagnoses (497.0 [±692.7] days) (Table 1) (all P < 0.001). Among veterans incarcerated for ≤2 years, average duration was significantly shorter for those with dementia (150.9 [±155.6] days) versus neither diagnosis (193.8 [±186.3]) (P < 0.001). Figure 1 presents distributions of incarceration duration by cognitive status for the entire sample (Panel A) and for veterans incarcerated ≤ 2 years (Panel B), with latter panel highlighting those with dementia and those with neither diagnosis comprise the largest proportions with durations <60 days and >210 days, respectively.

Figure 1. Distribution of incarceration duration by cognitive status.

Panel A: Distribution of the duration of incarceration in half-year intervals according to cognitive status for the entire sample (N=17,962). Panel B: Distribution of the duration of incarceration in 30-day intervals according to cognitive status for those incarcerated ≤ 2 years (N= 14,134).

Discussion

Leveraging a nationally-representative veteran sample who experienced incarceration in mid-to late-life, we emphasize 3 findings: (1) 3.3% had an MCI or dementia diagnosis prior to incarceration, most of whom were diagnosed with dementia; (2) those with MCI or dementia experienced higher rates of comorbidities and homelessness; and (3) those with MCI or dementia spent less time incarcerated.

Whereas 0.8% had an MCI diagnosis and 2.5% had a dementia diagnosis before most recent incarceration, we could not determine if detentions resulted from crimes due to dementia-related behaviors. Previous studies indicate higher likelihood of aggressive/antisocial behavior in persons with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)5, 7, 18 and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).7, 19 One recent study found 6.4% of persons with AD or FTD experienced police interactions initiated by behavior occurring before their diagnosis.20 A Finnish study found 12.8% and 23.5% of men with AD and FTD respectively, exhibited novel “criminal” behavior <3 years before diagnosis; 94% of behaviors were minor crimes (e.g., property/traffic offences).21 However, whether these behaviors resulted in incarceration is unclear. We also do not know from prior studies what proportion of incarcerated persons had these diagnoses before incarceration. Prospective studies are needed to determine incarceration risk among persons with MCI or dementia.

Possibly, our study under-estimates MCI and dementia prevalence. Because ICD-9/10 diagnosis codes link with healthcare encounters (e.g., doctor visit; outpatient procedure), diagnosis data was only available for those who accessed the healthcare system. Thus, the 3.3% prevalence estimate likely reflects those with symptoms severe enough to warrant a healthcare encounter. This may explain why dementia prevalence was higher than MCI prevalence; those experiencing mild symptoms may not have sought medical/psychiatric care.

Within non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black groups, the proportion of pre-incarceration dementia was 2.7% and 2.0%, respectively. Prevalence estimates from non-incarcerated populations indicate about twice as many Blacks than Whites have dementia, with social determinants of health implicated in these differences.22 In our study, similar proportions of dementia in Whites and Blacks suggests social determinants typically manifesting in race differences in dementia prevalence may be less pronounced among the incarcerated. These estimates may also reflect under-diagnosis among Blacks. More research in racial disparities of pre-incarceration diagnoses is needed.

We also found incarcerated persons with pre-incarceration MCI or dementia had more medical and psychiatric comorbidities than those without these diagnoses. Conditions including hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and chronic lung disease, all risk factors for dementia,23 were especially prevalent. Further, exploring differences between the dementia and MCI groups revealed a higher proportion of diabetes and stroke history among those with dementia. Because stroke and diabetes are indicative of vascular dementia, certain dementia subtypes may be more represented among those with dementia in our sample. The majority of those with dementia, as determined via ICD-9/10 codes, were diagnosed with “Dementia Not Otherwise Specified”. Therefore, we could not verify if certain dementia subtypes were over-represented. Future research should discern if specific dementia subtypes are over-represented among justice-involved persons as compared with the general population.

Recent studies suggest persons with SMI are more likely to be diagnosed with dementia than those without SMI.24, 25 Whereas mental illness is over-represented among incarcerated persons, in general,26 we still found the proportion of those with pre-incarceration SMI was significantly higher among those with MCI or dementia before incarceration. Moreover, comparing the dementia and MCI groups, those with dementia were significantly more likely to have history of psychotic illness and SMI. In fact, nearly half of those with dementia also had SMI. Persons with dementia or MCI and SMI entering carceral settings may be especially challenging to manage. Alternative settings, e.g., skilled nursing facilities adapted for people with psychiatric history, may better meet needs of this growing population.27 Results also indicated a considerably higher proportion of participants with MCI or dementia experienced pre-incarceration TBI and homelessness versus those without either diagnosis. Like mental illness, these conditions are disproportionately higher among incarcerated individuals and linked to increased risk of dementia and neurodegenerative diseases.13, 23, 28 Experiencing pre-incarceration TBI or homelessness may indicate an early-onset clinical phenotype of dementia.

Those in our study with pre-incarceration diagnoses of MCI or dementia had shorter durations of incarceration than veterans with neither diagnosis. In particular, a high proportion of persons with dementia had <60-day durations of incarceration. These relatively short stays likely reflect less severe, non-violent crimes. Amidst increasing efforts to decrease U.S. incarceration rates, improved understanding of behaviors leading to especially short durations (e.g, <1 week), may help determine avoidable incarcerations through interventions such as neurocognitive screening at time of arrest.

There are study limitations. Information regarding offenses leading to incarceration or severity of the MCI and dementia diagnoses was unavailable. Knowing diagnosis severity may improve understanding of the impact of cognitive decline on incarceration risk. Although we determined pre-incarceration diagnoses, the 3-year look-back period precluded our ability to confirm diagnosis date. Additionally, whether law enforcement, courts, or correctional departments were aware of pre-incarceration MCI or dementia diagnoses is unknown. Thus, we cannot comment on role of these diagnoses in establishing competency to stand trial. It is also unknown if illness progression was tracked among those with longer incarceration durations. Future studies should confirm whether progression from MCI to dementia occurs faster or more frequently in incarcerated versus community-living persons. Our sample did not include currently incarcerated persons. Therefore, proportion of pre-incarceration MCI or dementia is likely higher than reported. Because women comprised < 3% of the sample, given the relatively rare diagnoses of MCI and dementia, we lacked statistical power to evaluate sex differences. Finally, findings may be less generalizable to non-veterans.

As the number of persons with MCI or dementia increases, more individuals with these diagnoses will likely interact with the criminal justice system.29 Using a unique dataset, the first with national information on pre-incarceration diagnoses among those experiencing mid-to-late-life incarceration, we determined burden of MCI and dementia prior to incarceration. Improved understanding of pathways linking cognitive impairment to mid-to-late-life incarceration are needed to develop criminal justice reforms preventing unnecessary or unconstitutional incarceration, optimize healthcare and social services, and reduce interpersonal harm in this medically vulnerable group.

Supplementary Material

Key Points Box.

Key Points

In a national sample of incarcerated adults in mid- to late-life, >3% had mild cognitive impairment or dementia before incarceration, with high rates of medical/psychiatric comorbidity.

Why does this matter?

Understanding burden of MCI/dementia pre-incarceration has implications for optimizing services for this group.

Acknowledgements

Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004). We acknowledge that the original collector of the data, sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the U.S. government bear no responsibility for use of the data or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed otherwise.

Funding Source:

This work is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under award number RF1 MH117604-01S1 (PI: Dr. Barry & Dr. Byers). Dr. Barry is also supported by the UConn Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (NIA P30-AG067988). Dr. Byers is the recipient of a Research Career Scientist award (# IK6CX002386) from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Williams’ time was covered, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (the Aging Research In Criminal Justice Health Network), Grant #R24 AG065175

Sponsor’s Role

The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Paterson L The Violent Arrest Of A Woman With Dementia Highlights The Lack Of Police Training. National Public Radio (USA). June 15, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/15/1004827978/the-violent-arrest-of-a-woman-with-dementia-highlights-the-lack-of-police-traini. Accessed June 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slevin C Officer put on leave over arrest of woman with dementia. The Associated Press News Service. April 15, 2021. https://www.news10.com/news/national/officer-put-on-leave-over-arrest-of-woman-with-dementia/. Accessed June 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.“Doesn’t feel right:” Elderly patients with dementia handcuffed after caregivers call 911. FOX 6 Now Milwaukee. November 18, 2016. https://www.fox6now.com/news/doesnt-feel-right-elderly-patients-with-dementia-handcuffed-after-caregivers-call-911. Accessed July 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein R Legal System Struggles With Dementia Patients. The Washington post. July 28, 2003. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2003/07/28/legal-system-struggles-with-dementia-patients/abbc8ac7-e8b2-4bb2-b49b-3e41d54fc52f/. Accessed July 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu R, Topiwala A, Jacoby R, Fazel S. Aggressive Behaviors in Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(3):290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekstrom A, Kristiansson M, Bjorksten KS. Dementia and cognitive disorder identified at a forensic psychiatric examination - a study from Sweden. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0614-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liljegren M, Naasan G, Temlett J, et al. Criminal behavior in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(3):295–300. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruschak LM, Bronson J, Alper M. Disabilities Reported by Prisoners: Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2021. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/drpspi16st.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronson J, Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M. Disabilities Among Prison and Jail Inmates, 2011–12. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/dpji1112.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Miller BL, Rosen HJ, Barnes DE, Williams BA. Cognition and Incarceration: Cognitive Impairment and Its Associated Outcomes in Older Adults in Jail. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2065–2071. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15521 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez A, Manning KJ, Powell W, Barry LC. Cognitive Impairment in Older Incarcerated Males: Education and Race Considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021; S1064–7481(21)00329–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC, Seal KH, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K. Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury With and Without Loss of Consciousness With Dementia in US Military Veterans. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1055–1061. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunak MM, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Li Y, Byers AL. Risk of Suicide Attempt in Patients With Recent Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(6):659–666. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auguie B gridExtra: Miscellaneous Functions for “Grid” Graphics. 2017

- 17.Hadley W Ggplot2. New York: Springer International Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinagawa S, Shigenobu K, Tagai K, et al. Violation of Laws in Frontotemporal Dementia: A Multicenter Study in Japan. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(4):1221–1227. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liljegren M, Landqvist Waldo M, Rydbeck R, Englund E. Police Interactions Among Neuropathologically Confirmed Dementia Patients: Prevalence and Cause. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32(4):346–350. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talaslahti T, Ginters M, Kautiainen H, et al. Criminal Behavior in the Four Years Preceding Diagnosis of Neurocognitive Disorder: A Nationwide Register Study in Finland. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(7):657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. Mar 2021;17(3)(Special Report — Race, Ethnicity and Alzheimer’s in America; ):327–406. doi: 10.1002/alz.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):505–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown MT, Wolf DA. Estimating the Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness and Dementia Diagnoses Among Medicare Beneficiaries in the Health and Retirement Study. Res Aging. 2018;40(7):668–686. doi: 10.1177/0164027517728554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stroup TS, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Age-Specific Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia Diagnoses Among Older US Adults With Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(6):632–641. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Møller L, Stöver H, Jürgens R, Gatherer A, Nikogosian H. Health in prisons: a WHO guide to the essentials in prison health. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry LC, Robison J, Wakefield D, Glick J. Evaluation of Outcomes for a Skilled Nursing Facility for Persons Who are Difficult to Place. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2018;46(2):187–194. doi: 10.29158/JAAPL.003746-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pina-Escudero SD, Lopez L, Sriram S, Longoria Ibarrola EM, Miller B, Lanata S. Neurodegenerative Disease and the Experience of Homelessness. Front Neurol. 2020;11:562218. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.562218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barry LC. Mass Incarceration in an Aging America: Implications for Geriatric Care and Aging Research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2048–2049. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.