Abstract

Background:

The association between body mass index (BMI) and adiposity differs by race/ethnicity.

Objective:

To examine differences in adiposity by race/Hispanic origin among US youth and explore how those differences relate to differences in BMI using the most recent national data, including non-Hispanic Asian youth.

Methods:

Weight, height, and DXA-derived fat mass index (FMI) and percentage body fat (%BF) from 6923 youth 8-19y in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2018 were examined. Age-adjusted mean BMI, FMI and %BF were reported. Sex-specific linear regression models predicting %BF and FMI were adjusted for age, BMI category and BMI category*race/Hispanic origin interaction.

Results:

%BF was highest among Hispanic males (28.2%) and females (35.7%). %BF was lower among non-Hispanic Black (23.9%) compared with non-Hispanic White (26.0%) and non-Hispanic Asian (26.6%) males. There was no difference between non-Hispanic Black females (32.7%) and non-Hispanic White (33.2%) or non-Hispanic Asian (32.7%) females. FMI was higher among Hispanic youth compared with non-Hispanic White youth. Among youth with underweight/healthy weight, predicted %BF and FMI were lower among non-Hispanic Black males (−2.8%; −0.5) and females (−2.0%; −0.3), compared with non-Hispanic White youth, and higher among Hispanic males (0.9%; 0.2) and females (2.0%; 0.5), while %BF but not FMI was higher among non-Hispanic Asian males (1.3%) and females (1.4%). Among females with obesity, non-Hispanic Asian females had lower %BF (−2.3%) and FMI (−1.7) than non-Hispanic White females.

Conclusions:

Differences in %BF and FMI by race/Hispanic origin were not consistent by BMI category among U.S. youth in 2011-2018.

Keywords: adiposity, percentage body fat, fat mass index, DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, NHANES

Introduction

Body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2) is commonly used to define obesity both clinically and in population-based studies. However, BMI is not a direct measure of adiposity and studies have shown differences in the association between BMI and adiposity by BMI category, age, race/ethnicity, and health risk.1-9 Among children and adolescents, BMI does not estimate adiposity well among children with lower BMI, when compared with direct measures of adiposity.10, 11 BMI has a stronger association with adiposity at higher levels of body fatness.4

Differences in obesity prevalence among U.S. youth by race and Hispanic origin have been well reported.12-17 Studies have found higher obesity prevalence among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black youth, compared with non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian youth.14, 15 There are fewer nationally representative studies of disparities among U.S. youth using directly measured adiposity, and none have included analyses that compared Asian youth to other groups. Previous studies have examined percentage body fat (%BF) and fat mass index (FMI; in kg/m2) measured with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) among youth by race and Hispanic origin using data from the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).1, 18, 19 Flegal et al. (2010) compared %BF and BMI-for-age by race and Hispanic origin among non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican American children and adolescents and found that the prevalence of high BMI, but not high adiposity, was significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black females compared with non-Hispanic White females.1 In a separate study, FMI z score was higher among Mexican American males than non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black males and higher among non-Hispanic Black than non-Hispanic White males.20 No difference in FMI z score by race and ethnicity was seen among females.20

The current study supplements previous analyses by using recently-released DXA data from NHANES 2011–2018, by including non-Hispanic Asian youth (who could not be analyzed separately in earlier nationally-representative NHANES data), and by examining differences in FMI; in addition to %BF and BMI. FMI is useful as an additional direct measure of adiposity because it directly compares fat mass adjusting for height, while differences in %BF between individuals may reflect differences in fat mass, fat-free mass, or both.21 Compared with FMI, the use of %BF alone may underestimate adiposity among those with high lean body mass.20 The objectives of this study were to examine differences in DXA-measured %BF and in DXA-measured FMI during 2011–2018 by race and Hispanic origin among U.S. children and adolescents aged 8–19 years, hereafter termed youth, and to explore how differences in adiposity relate to differences in BMI.

Methods

Analyses were conducted using data from NHANES. NHANES is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population, which includes both interview and physical examination components. NHANES uses a complex, multistage sampling design and has been conducted continuously since 1999 with data released in two-year cycles, most recently for 2017–2018.22 Recently-released DXA data from four survey cycles (2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018) were combined for this study in order to improve precision of the estimates.

The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved NHANES protocols. Youth aged 8–17 years provided written assent and parents or guardians provided written consent. Participants aged 18 years and over provided written consent. NHANES examination response rates for youth aged 6–19 were 76.8% during 2011–2012, 76.2% during 2013–2014, 64.7% during 2015–2016, and 54.3% during 2017–2018.23

Age was assessed as age in months at examination. Survey participants aged 8 years and over were eligible for whole-body DXA scans. Race and Hispanic origin were reported separately by participants or proxy respondents (such as parents) and categorized on the publicly-released NHANES data files as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic other race (including non-Hispanic persons who reported two or more races ).24 Non-Hispanic persons reporting another race or multiple races were included in the overall analysis by sex and age, but results for this group were not reported separately. Non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic persons were oversampled during 2011–2018 survey cycles to improve the stability and reliability of estimates for these subgroups.

Standardized measures of weight and height were obtained during the NHANES examination. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and rounded to one decimal place. BMI was categorized based on sex- and age-specific percentiles of the 2000 CDC growth charts as underweight/healthy weight (<85th percentile); overweight (≥85th percentile to <95th percentile); or obesity (≥95th percentile).25 Underweight and healthy weight youth were grouped due to the small number of participants with underweight (<5th percentile; n=234). A sensitivity analysis that excluded underweight youth was conducted to assess the possibility that comparisons were affected by different proportions of underweight youth within race and Hispanic origin groups. The estimates and overall conclusions were similar to the main analysis, so only results from the overall sample are presented.

Whole-body DXA scans were acquired on Hologic Discovery A densitometers (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts). All scans from 2011–2018 were analyzed with Hologic APEX version 4.0 software with NHANES Body Composition Analysis option. Quality control and data review procedures have been published previously.26 The weight limit for the DXA examination table was 450 pounds (204.1 kilograms).26 Percentage body fat (%BF) was calculated as total body fat mass divided by total mass (lean mass plus fat mass) and multiplied by 100. FMI was calculated as total body fat mass in kilograms divided by height (in meters)-squared.

Mean BMI, FMI and %BF are reported. Age-specific means are graphically displayed. Sex-specific means are reported graphically, accompanied by differences by race and Hispanic origin using pairwise t-tests. To account for possible differences in age distributions between race and Hispanic origin groups, overall age-adjusted estimates are presented. Means were adjusted by direct age standardization to the sex-specific age distribution of the overall analytic sample in six-month age groupings. In addition, sex-specific linear regression models for %BF and FMI were used to investigate how race and Hispanic origin differences in BMI relate to race and Hispanic origin differences in %BF and FMI. Interaction terms created with BMI category and race and Hispanic origin were included to test whether the association between race and Hispanic origin and %BF or FMI varied by BMI category, and Satterthwaite-adjusted F statistic p values were reported. Predicted marginal means of %BF and FMI are presented, adjusting for age, BMI category, and BMI category interaction with race and Hispanic origin. All analyses were stratified by sex due to known differences in body composition and pubertal developmental patterns.27-29

To further investigate differences in %BF, FMI and BMI by race and Hispanic origin across their range in the population, age adjusted, sex- and race and Hispanic origin-specific distributions of BMI, FMI, and %BF were calculated by kernel density estimation with the oversmoothing method.30

NHANES examination sample weights were used to account for differential probabilities of selection, nonresponse, and noncoverage.24 Taylor series linearization was used to estimate standard errors accounting for the complex survey design features. Differences between groups were tested using a univariate t statistic, and all differences noted were statistically significant at the alpha level of 0.05 or below. No adjustments were applied for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.4) and SUDAAN (version 11).

During 2011-2018, 87 examined youth aged 8–19 years were missing height, weight, or both, and were excluded from the analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). An additional 1279 youth did not have a DXA whole body scan completed or the scan was insufficient to calculate body fat percentage and were excluded, leaving a total sample size of 6923 (unweighted percent excluded 1366/8289 = 16.5%). Incomplete scans may be secondary to invalid scans, due to the presence of removable or nonremovable objects, noise, arm/leg overlap, body parts of the scan region, positioning issues, motion, missing limbs, other artifacts or secondary to nonparticipation, due to insufficient time, participant refusal, or medical concerns.26, 31 Sex-specific distributions by age group (8–11, 12–15, and 16–19 years), race and Hispanic origin, and BMI category among youth with a valid DXA %BF measurement were similar to the distributions among all examined youth.

Results

Unweighted sample sizes and weighted share of the population aged 8-19 years are shown in Table 1 by age group, BMI category, and race and Hispanic origin. Nearly 20% (19.8%) of the entire population had obesity.

Table 1.

Unweighted sample sizes and weighted percentage of total among children and adolescents aged 8-19 years, by sex, age group, race and Hispanic origin, and BMI category

| Males | Females | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size1 |

Percent2 | Sample size1 |

Percent2 | Sample size1 |

Percent2 | |

| All | 3584 | 100 | 3339 | 100 | 6923 | 100 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 8-11 years | 1387 | 32.7 | 1347 | 34 | 2734 | 33.3 |

| 12-15 years | 1164 | 35.1 | 998 | 33.5 | 2162 | 34.3 |

| 16-19 years | 1033 | 32.3 | 994 | 32.5 | 2027 | 32.4 |

| Race and Hispanic origin3 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 987 | 52.9 | 880 | 54.3 | 1867 | 53.6 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 897 | 13.7 | 788 | 12.8 | 1685 | 13.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 367 | 4.4 | 335 | 4.6 | 702 | 4.5 |

| Hispanic | 1090 | 23.7 | 1110 | 23.1 | 2200 | 23.4 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) Category | ||||||

| Underweight/healthy weight | 2223 | 63.7 | 2049 | 63.1 | 4272 | 63.4 |

| Overweight | 582 | 16 | 603 | 17.5 | 1185 | 16.8 |

| Obesity | 779 | 20.3 | 687 | 19.3 | 1466 | 19.8 |

Sample sizes are unweighted counts of examined youth aged 8-19 years at exam, with valid measured BMI and body fat percentage.

Weighted percent of the total

Non-Hispanic youth reporting other races or multiple races are included in the totals but not reported separately.

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018.

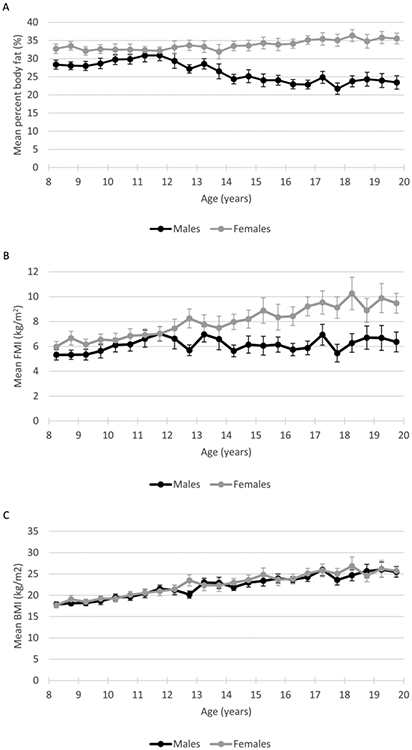

Figure 1 shows mean %BF (panel a), FMI (panel b), and BMI (panel c) by sex and age in six-month increments. Mean %BF was higher in females than males across the age range, with the gap increasing around age 12 years. Mean FMI was also higher in females than males, with a larger gap after about age 14 years. Mean %BF appeared relatively flat across adolescence among females but showed a decreasing pattern among males starting around age 12 years. Mean FMI showed an increasing pattern with age among females but was relatively flat among males. Mean BMI increased with age for both sexes, and mean age-specific BMI was similar between males and females.

Figure 1.

Mean percentage body fat, Fat Mass Index (FMI), and Body Mass Index (BMI) among children and adolescents aged 8-19 years, by 6-month age intervals and sex: United States, 2011–2018(A) Mean body fat percentage (%BF)(B) Mean fat mass index (FMI). (C) Mean body mass index (BMI) 95% confidence intervals are provided. SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018

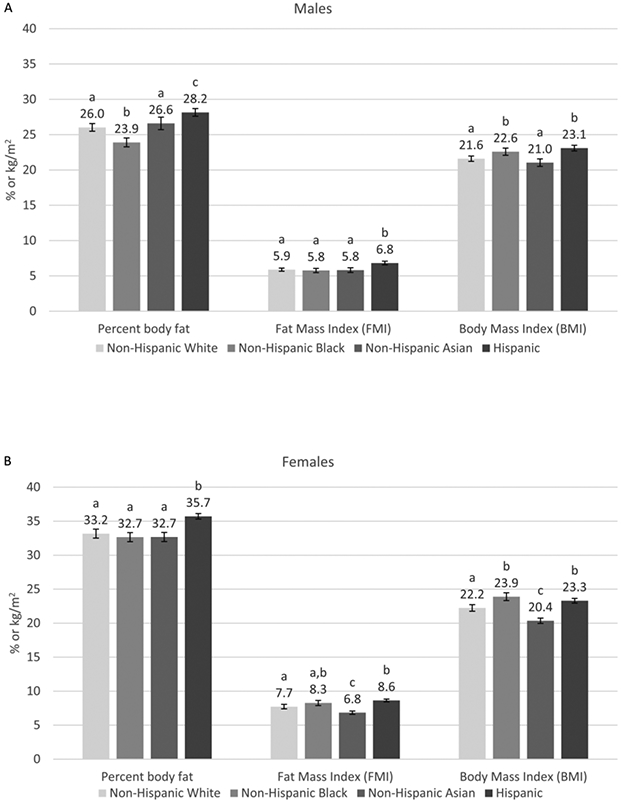

Age-adjusted mean %BF, FMI, and BMI by sex and race and Hispanic origin are shown in Figure 2. Among males (panel a), %BF was significantly lower among non-Hispanic Black males (23.9% [95% CI, 23.3 to 24.5]) and higher among Hispanic males (28.2% [95% CI, 27.6 to 28.7]) than among other race and Hispanic origin groups. FMI was also higher among Hispanic males (6.8 kg/m2 [95% CI, 6.6 to 7.1]) compared with all other race and Hispanic origin groups (5.8–5.9 kg/m2). In contrast, mean BMI was higher among non-Hispanic Black (22.6 kg/m2 [95% CI, 22.1 to 23.1]) and Hispanic (23.1 kg/m2 [95% CI, 22.7 to 23.5]) males compared with non-Hispanic White (21.6 kg/m2 [95% CI, 21.2 to 22.0]) and non-Hispanic Asian (21.0 kg/m2 [95% CI, 20.5 to 21.6]) males. Mean %BF, FMI, and BMI were not statistically different between non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian males.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted mean percentage body fat, FMI, and BMI among children and adolescents aged 8–19 years, by sex and race and Hispanic origin, 2011-2018(A) Males (B) Females Means are weighted and age-adjusted to the sex-specific age distribution of the sample in six-month age groups. 95% confidence intervals are provided. Means with no letter in common are significantly different (t-test; p < 0.05)SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018

Among females (panel b), mean %BF was significantly higher among Hispanic females (35.7% [95% CI, 35.3 to 36.1]) than among other race and Hispanic origin groups (32.7% – 33.2%), but there were no other significant differences in %BF between race and Hispanic origin groups. FMI was higher among Hispanic females (8.6 kg/m2 [95% CI, 8.4 to 8.9]) than among non-Hispanic White (7.7 kg/m2 [95% CI, 7.4 to 8.1]) and non-Hispanic Asian (6.8 kg/m2 [95% CI, 6.6 to 7.1]) females and lower among Non-Hispanic Asian females compared to other race and Hispanic origin groups. A similar pattern was observed for BMI, although mean BMI was higher among both Hispanic (23.3 kg/m2 [95% CI, 22.9 to 23.6]) and non-Hispanic Black females (23.9 kg/m2 [95% CI, 23.3 to 24.5]) compared with non-Hispanic White (22.2 kg/m2 [95% CI, 21.8 to 22.7]) and non-Hispanic Asian (20.4 kg/m2 [95% CI, 20.0 to 20.8]) females. Overall patterns by race and Hispanic origin for %BF, FMI and BMI differed from each other.

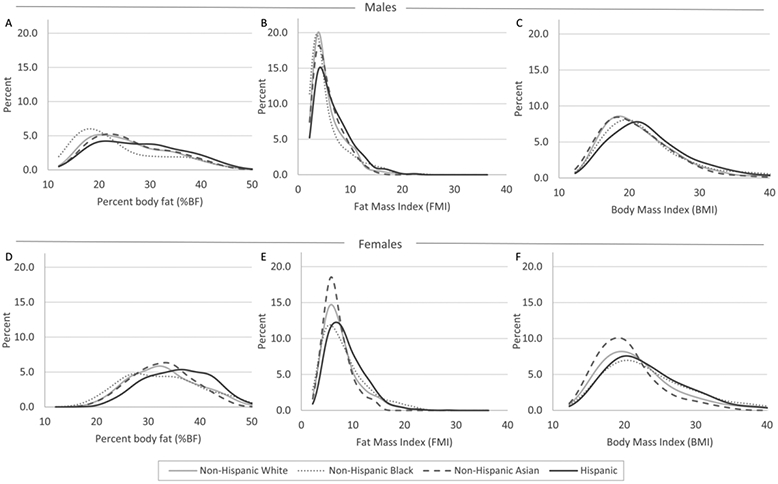

Figure 3 presents smoothed distributions of BMI, FMI, and %BF by sex and race and Hispanic origin for all youth in the study. These figures allow visual comparison of the different patterns in the distributions across race and Hispanic origin groups; statistical tests were not performed. Among both males and females, the distributions of BMI, FMI, and %BF for Hispanic youth appeared shifted rightward and more skewed, compared with other race and Hispanic origin groups of the same sex. Although the BMI distribution among non-Hispanic Black males appeared shifted rightward compared with non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian males, the distributions of FMI and particularly %BF among non-Hispanic Black males was shifted to the left compared with the other two groups. Distributions of BMI and %BF appeared similar between non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Asian males, although compared with non-Hispanic White males, the BMI distribution for non-Hispanic Asian males was slightly to the left and the %BF distribution was slightly to the right.

Figure 3.

Distributions of Body Mass Index, Fat Mass Index, and Percentage Body Fat among children and adolescents age 8 - 19 years, by sex and race and Hispanic origin: 2011-2018%"(A) Percent body fat among males (B) Fat Mass Index among males (C) Body Mass Index among males (D) Percent body fat among females (E) Fat Mass Index among females (F) Body Mass Index among females%"Distributions are weighted and age-adjusted to the sex-specific age distribution of the sample in six-month age groups.%"SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018

Among females, the distributions of BMI and FMI among non-Hispanic Asian females had a higher peak and appeared to be shifted leftward compared with other groups, but the distribution of %BF among non-Hispanic Asian females was shifted rightward and seemed more skewed compared with non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White females. Although the distribution of BMI among non-Hispanic Black females appeared to be shifted rightward and more skewed compared with non-Hispanic White females, the peak of the %BF distribution occurred at a lower %BF among non-Hispanic Black females compared with other race and Hispanic origin groups.

In sex-stratified regression models adjusting for age, race and Hispanic origin, and BMI category, interaction terms between race-Hispanic origin and BMI category were statistically significant, suggesting that the differences in %BF and FMI between race-Hispanic origin groups varied by BMI category (Table 2). Within each BMI category, predicted mean (i.e. estimated marginal mean adjusting for age, BMI category, and BMI category interaction with race and Hispanic origin) %BF was lower among non-Hispanic Black males compared with non-Hispanic White males in the same BMI category, and predicted FMI was lower among non-Hispanic Black males in the underweight/healthy weight and overweight BMI categories. Both %BF and FMI were lower among non-Hispanic Black females compared with non-Hispanic White females in the underweight/healthy weight and overweight BMI categories, but not among females with obesity.

Table 2.

Mean percentage body fat and fat mass index predicted by sex-specific, adjusted linear regression model among children and adolescents aged 8-19 years, by sex, race and Hispanic origin, and BMI category: United States, 2011-2018

| Sex, BMI Category and Race- Hispanic Origin1 |

Percent body fat (%BF) | Fat Mass Index (FMI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Mean (95% CI)2 |

Difference in predicted mean (95% CI)3 |

P value4 |

Predicted Mean (95% CI) 2 |

Difference in predicted mean (95% CI)3 |

P value4 |

|

| Males | ||||||

| Underweight/Healthy weight | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 22.2 (21.8 - 22.5) | Ref. | -- | 4.2 (4.1 - 4.3) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 19.4 (18.9 - 19.8) | −2.8 (−3.4 - −2.1) | 0 | 3.7 (3.6 - 3.8) | −0.5 (−0.7 - −0.3) | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 23.4 (22.7 - 24.1) | 1.3 (0.5 - 2.0) | 0.0011 | 4.4 (4.2 - 4.6) | 0.2 (−0.0 - 0.4) | 0.067 |

| Hispanic | 23.1 (22.6 - 23.6) | 0.9 (0.3 - 1.5) | 0.0043 | 4.5 (4.3 - 4.6) | 0.2 (0.1 - 0.4) | 0.0064 |

| Overweight | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 30.9 (30.1 - 31.8) | Ref. | -- | 7.4 (7.2 - 7.7) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 26.5 (25.4 - 27.7) | −4.4 (−5.8 - −3.0) | 0 | 6.3 (6.0 - 6.6) | −1.1 (−1.5 - −0.8) | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 31.9 (30.6 - 33.2) | 1.0 (−0.7 - 2.7) | 0.2585 | 7.6 (7.3 - 7.9) | 0.2 (−0.3 - 0.6) | 0.4263 |

| Hispanic | 30.3 (29.7 - 31.0) | −0.6 (−1.6 - 0.4) | 0.2163 | 7.3 (7.1 - 7.4) | −0.2 (−0.4 - 0.1) | 0.1758 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 36.7 (35.9 - 37.5) | Ref. | -- | 11.0 (10.6 - 11.4) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 35.6 (34.8 - 36.3) | −1.1 (−2.2 - −0.0) | 0.0449 | 11.5 (11.1 - 12.0) | 0.5 (−0.1 - 1.1) | 0.0871 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 36.7 (35.2 - 38.2) | 0.1 (−1.6 - 1.7) | 0.9454 | 10.7 (9.9 - 11.5) | −0.3 (−1.2 - 0.6) | 0.4982 |

| Hispanic | 37.3 (36.6 - 38.0) | 0.6 (−0.4 - 1.6) | 0.2325 | 11.5 (11.1 - 11.9) | 0.5 (−0.0 - 1.0) | 0.0605 |

| Females | ||||||

| Underweight/Healthy weight | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 29.7 (29.2 - 30.2) | Ref. | -- | 5.8 (5.7 - 6.0) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 27.7 (27.1 - 28.2) | −2.0 (−2.7 - −1.4) | 0 | 5.5 (5.3 - 5.6) | −0.3 (−0.5 - −0.2) | 0.0007 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 31.1 (30.5 - 31.8) | 1.4 (0.6 - 2.2) | 0.001 | 6.0 (5.8 - 6.1) | 0.2 (−0.1 - 0.4) | 0.1659 |

| Hispanic | 31.7 (31.3 - 32.2) | 2.0 (1.4 - 2.7) | 0 | 6.3 (6.2 - 6.4) | 0.5 (0.3 - 0.7) | 0 |

| Overweight | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 37.2 (36.5 - 37.9) | Ref. | -- | 9.2 (9.0 - 9.5) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 34.6 (34.0 - 35.2) | −2.5 (−3.4 - −1.6) | 0 | 8.7 (8.5 - 8.9) | −0.5 (−0.8 - −0.2) | 0.0007 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 38.3 (37.1 - 39.6) | 1.2 (−0.3 - 2.6) | 0.1185 | 9.5 (9.1 - 9.9) | 0.3 (−0.2 - 0.8) | 0.2639 |

| Hispanic | 38.5 (37.9 - 39.1) | 1.3 (0.4 - 2.2) | 0.0051 | 9.6 (9.4 - 9.7) | 0.3 (0.0 - 0.6) | 0.0322 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 42.8 (42.0 - 43.6) | Ref. | -- | 13.7 (13.2 - 14.3) | Ref. | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 41.9 (41.0 - 42.8) | −0.8 (−2.0 - 0.3) | 0.1608 | 14.0 (13.3 - 14.7) | 0.3 (−0.7 - 1.2) | 0.5531 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 40.5 (39.1 - 41.8) | −2.3 (−3.9 - −0.6) | 0.0072 | 12.0 (11.3 - 12.8) | −1.7 (−2.7 - −0.7) | 0.0017 |

| Hispanic | 42.5 (42.1 - 42.9) | −0.3 (−1.2 - 0.6) | 0.5167 | 13.3 (12.9 - 13.6) | −0.5 (−1.1 - 0.2) | 0.1384 |

Interaction term between BMI category and race-Hispanic origin was statistically significant (p<0.05) in sex-specific linear regression model adjusting for age, BMI category, and BMI category interacted with race and Hispanic origin

Predicted marginal from sex-specific linear regression model adjusting for age, BMI category, and BMI category interacted with race and Hispanic origin

Difference in predicted mean compared to reference group calculated as linear contrasts of predicted marginals, adjusting for age, BMI category and BMI category interacted with race and Hispanic origin

P-value for difference in predicted mean compared to reference group, adjusting for age, BMI category and BMI category interacted with race and Hispanic origin

SOURCE: NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018.

Among youth with underweight/healthy weight, predicted %BF was 1.3 percentage points (95% CI, 0.5 to 2.0 percentage points) higher among non-Hispanic Asian males and 1.4 percentage points (95% CI, 0.6 to 2.2 percentage points) higher among non-Hispanic Asian females, compared with non-Hispanic White youth, while predicted FMI was not significantly different between non-Hispanic White and Asian male or female youth. Among females with obesity, however, predicted %BF was 2.3 percentage points lower (95% CI, −3.9 to −0.6) and predicted FMI was 1.7 kg/m2 lower (95% CI, −2.7 to −0.7) among non-Hispanic Asian females compared with non-Hispanic White females.

Predicted mean %BF and FMI were significantly higher in Hispanic males with underweight/healthy weight and in Hispanic females with underweight/healthy weight or overweight, compared with non-Hispanic White youth of the same sex and BMI category.

Discussion

Race and Hispanic origin differences in %BF and FMI varied by BMI category in U.S. youth in 2011–2018. Among youth in the underweight/healthy weight category, %BF and FMI were lower among non-Hispanic Black males and females than non-Hispanic White males and females. Conversely, %BF was higher among non-Hispanic Asian and Hispanic males and females with underweight/healthy weight. There were fewer significant race and Hispanic origin differences among youth with obesity. Percentage body fat was lower among non-Hispanic Black males and non-Hispanic Asian females than their non-Hispanic White counterparts with obesity. Differences in BMI by race and Hispanic origin did not mirror differences in %BF and FMI, suggesting that BMI does not adequately capture all race and Hispanic origin differences in adiposity among children and adolescents.

Differences in body fat by race and Hispanic origin among children have been described in many studies.1, 2, 4, 5 This study builds upon a prior analysis by Flegal et al (2010), using NHANES 1999–2004 data, which found that differences in obesity based on BMI did not reflect similar differences in directly measured body fat, such that most non-Hispanic Black children in the overweight category did not have high adiposity.1 The patterns of differences in age-standardized mean %BF and BMI between non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black youth in the current study are similar to those observed by Flegal et al. Contrary to the prior study, non-Hispanic Asian persons were able to be analyzed separately in this study. In a prior non-nationally representative study, Freedman et al (2008) also examined differences in mean %BF by race stratified by BMI category using data from 1,104 healthy 5–18 year olds.5 They found that mean %BF varied by race/ethnicity among boys and girls in lower BMI categories, but there were no statistically significant differences by race/ethnicity among boys and girls with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) or girls with BMI-for-age between the 85th and 94th percentiles. However, there were fewer children with BMI ≥ 95th percentile than in the other BMI categories, which could have affected the ability to detect significant differences. Using stratified analyses, their study suggested that mean body fat was higher among Asian boys than among White boys within the 50th to 95th percentile of BMI-for-age, was higher among Asian girls compared to White girls within <85th percentile of BMI-for-age, and was lower among Asian girls compared to White girls within the ≥95th percentile of BMI-for-age.5 We found similar differences in percent body fat by BMI category among Asian youth. However, such differences in percent body fat did not extend to FMI, except among Asian girls ≥95th percentile of BMI-for-age.

Limitations of BMI as an indicator of adiposity have been well-characterized.4, 32 BMI is a measure of weight relative to height and cannot distinguish between fat mass and fat-free mass.32 Differences in BMI between race and Hispanic origin groups can thus be due to variations in both lean mass and fat mass.1 We show here differences in direct measures of adiposity by race and Hispanic origin in the context of BMI. Differences in adiposity among adults with normal weight may be associated with disease risk, though less is known for children and adolescents.33 For adults, given such limitations and evidence that disease risk among Asian adults is elevated at a lower BMI compared with non-Hispanic White adults, a WHO expert consultation advised that lower BMI cutpoints be used for populations of Asian adults.34

This analysis has some strengths. BMI, %BF and FMI were based on direct measurements of weight, height, and body fat. BMI cannot distinguish between lean and fat mass. However, FMI, a direct absolute measure of fat mass, and percent body fat, a direct relative measure of body fat, are useful when used together for distinguishing differences due to lean and fat mass.20 In addition, the NHANES sample is nationally representative of the civilian non-institutionalized population. Finally, because NHANES over-sampled the entire Hispanic population (instead of only the Mexican American population as in early cycles of NHANES) beginning in 2007 and the non-Hispanic Asian population beginning in 2011, this analysis was able to expand on previous comparisons that used earlier national data by including non-Hispanic Asian and all Hispanic youths. There are at least several limitations. First, despite oversampling, estimates are based on a relatively small sample of non-Hispanic Asian youth. Second, response rates for NHANES have been declining over time, along with those of other national surveys, and lower response rates increase the potential for bias. However, an extensive non-response bias investigation into the 2017–2018 NHANES showed that errors in representation from sample variation and nonresponse were minimized with weighting adjustments.35 Third, DXA-measured %BF or measured height or weight was missing for 16.3% of examined youth aged 8–19 in 2011–2018, although sociodemographic variables were not different among those with missing data. Fourth, although the regression model adjusted for BMI category, there may be residual confounding by BMI if there are racial-ethnic differences in the distribution of BMI within BMI categories. Additionally, there may be further differences by subgroup within the race and Hispanic origin categories used for this analysis; for example, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among non-Hispanic Asian youth varies by Asian ethnicity,36 and relationships between BMI, FMI, and %BF may vary by origin or ancestry subgroups within the race and Hispanic origin groups analyzed here.2

In this nationally representative sample of U.S. youth that included analysis of non-Hispanic Asian persons and direct measures of body fat, weight and height, differences in %BF and FMI between race and Hispanic origin groups varied by BMI category, providing further evidence that other measures besides BMI are important to consider when studying adiposity among children and adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows — NS: prepared the data; CBM: analyzed the data, wrote the paper, and has primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: designed the research, provided critical revision of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Yanovski reports grants from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, grants from Soleno Therapeutics, non-financial support from Hikma Pharmaceuticals, grants from NICHD intramural research grant, outside the submitted work.

Contributor Information

Crescent B. Martin, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC

Bryan Stierman, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC; Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC.

Jack A. Yanovski, Section on Growth and Obesity, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH

Craig M. Hales, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC; United States Public Health Service

Neda Sarafrazi, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC.

Cynthia L. Ogden, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Yanovski JA, et al. High adiposity and high body mass index-for-age in US children and adolescents overall and by race-ethnic group. Am J Clin Nutr. Apr 2010;91(4):1020–6. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Guricci S. Asians are different from Caucasians and from each other in their body mass index/body fat per cent relationship. Obes Rev. Aug 2002;3(3):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Berenson GS, Horlick M. Body mass index and body fatness in childhood. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8(6):618–623. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000171128.21655.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman DS, Sherry B. The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics. 2009;124 Suppl 1:S23–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman DS, Wang J, Thornton JC, et al. Racial/ethnic Differences in Body Fatness Among Children and Adolescents. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1105–1111. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman DS, Wang J, Thornton JC, et al. Classification of body fatness by body mass index-for-age categories among children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(9):805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels SR, Khoury PR, Morrison JA. The utility of body mass index as a measure of body fatness in children and adolescents: differences by race and gender. Pediatrics. Jun 1997;99(6):804–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deurenberg P, Bhaskaran K, Lian PL. Singaporean Chinese adolescents have more subcutaneous adipose tissue than Dutch Caucasians of the same age and body mass index. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12(3):261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanovski JA, Yanovski SZ, Filmer KM, et al. Differences in body composition of black and white girls. Am J Clin Nutr. Dec 1996;64(6):833–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.6.833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demerath EW, Schubert CM, Maynard LM, et al. Do changes in body mass index percentile reflect changes in body composition in children? Data from the Fels Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics. Mar 2006;117(3):e487–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Blanck HM, Borrud LG, Dietz WH. The abilities of body mass index and skinfold thicknesses to identify children with low or elevated levels of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-determined body fatness. J Pediatr. Jul 2013;163(1):160–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29(1):6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 Through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21)doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. Oct 2017;(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in Obesity Prevalence by Demographics and Urbanization in US Children and Adolescents, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(23)doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence by Race and Hispanic Origin-1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA. Sep 22 2020;324(12):1208–1210. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and uouth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. Nov 2015;(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dugas LR, Cao G, Luke AH, Durazo-Arvizu RA. Adiposity Is Not Equal in a Multi-Race/Ethnic Adolescent Population: NHANES 1999-2004. Obesity. 2011;19(10):2099–2101. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrud LG, Flegal KM, Looker AC, Everhart JE, Harris TB, Shepherd JA. Body composition data for individuals 8 years of age and older: U.S. population, 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11. Apr 2010;(250):1–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber DR, Moore RH, Leonard MB, Zemel BS. Fat and lean BMI reference curves in children and adolescents and their utility in identifying excess adiposity compared with BMI and percentage body fat. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):49–56. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.053611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells JCK. Measurement: A critique of the expression of paediatric body composition data. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(1):67–72. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.1.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Accessed February 28, 2020, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm

- 23.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES Response Rates and Population Totals. Accessed February 28, 2020, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ResponseRates.aspx

- 24.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Analytic Guidelines, 2011-2014 and 2015-2016. Updated December 14, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2021, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticguidelines/11-16-analytic-guidelines.pdf

- 25.Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Changes in terminology for childhood overweight and obesity. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;(25):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES Body Composition Procedures Manual. Updated July 2018. Accessed December 6, 2021, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/manuals/Body_Composition_Procedures_Manual_2018.pdf

- 27.Siervogel RM, Demerath EW, Schubert C, et al. Puberty and body composition. Horm Res Paediatr. 2003;60(Suppl. 1):36–45. doi: 10.1159/000071224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden CL, Li Y, Freedman DS, Borrud LG, Flegal KM. Smoothed percentage body fat percentiles for U.S. children and adolescents, 1999-2004. Natl Health Stat Report. Nov 9 2011;(43):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garn SM, Clark DC. Trends in fatness and the origins of obesity Ad Hoc Committee to Review the Ten-State Nutrition Survey. Pediatrics. Apr 1976;57(4):443–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terrell GR DW S. Oversmoothed nonparametric density estimates. J Am Stat Assoc. 1985;80:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Dual-energy Xray absorptiometry—whole body, 2017–2018, data documentation, codebook, and frequencies. Accessed December 13, 2021, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/DXX_J.htm

- 32.Kelly NR, Shomaker LB, Pickworth CK, et al. A prospective study of adolescent eating in the absence of hunger and body mass and fat mass outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). Jul 2015;23(7):1472–1478. doi: 10.1002/oby.21110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shea JL, King MT, Yi Y, Gulliver W, Sun G. Body fat percentage is associated with cardiometabolic dysregulation in BMI-defined normal weight subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Sep 2012;22(9):741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. Jan 10 2004;363(9403):157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fakhouri THI, Martin CB, Chen TC, et al. An investigation of nonresponse bias and survey location variability in the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 2020;185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asian and Pacific Islander American Health Forum. Obesity and overweight among Asian American children and adolescents. 2016. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://www.apiahf.org/resource/obesity-and-overweight-among-asian-american-children-and-adolescents/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.