Abstract

Background:

Medical care delivery has been substantially disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to delays in medical care, particularly among older adults. Less is known about how these delays have affected different segments of this population. Understanding the negative health consequences older adults face from delayed care will provide critical insights into the longer-term population health needs following the pandemic.

Methods:

We used data from a COVID-19 substudy embedded in a nationally representative longitudinal study of older adults, the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Data were collected between September 14, 2020 and January 27, 2021. 2,672 individuals responded to the survey. Using logistic and multinomial logistic regressions, we determined respondent-level characteristics associated with delayed medical care, experiencing a negative impact on physical health from delayed care, and with reporting worsening physical health during the pandemic.

Results:

Nearly one-third (32.8%) of older adults reported delayed medical care during the pandemic. Female sex, higher levels of education, greater concerns about the pandemic, and poorer self-rated physical health were associated with delayed medical care. Blacks and those who are 70 and older were less likely to report delayed care. Among those whose care was delayed, 76.5% reported having already recovered delayed care. Nearly one in five (17.6%) reported that delayed care negatively affected their health. Older adults with worse self-rated physical and mental health or who had not fully recovered delayed care were more likely to report perceived negative health impacts from the delay. Regardless of delayed medical care, 10.2% reported worse physical health during the pandemic.

Conclusions:

One-third of older adults experienced care delays during the pandemic. Despite high rates of care recovery, nearly one in five older adults who experienced delayed care reported being negatively affected. Strategies must be developed to reach these vulnerable patients to increase their healthcare utilization.

Keywords: COVID-19, medical care delay, older adults

Introduction

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant shift in medical care delivery and utilization. Many ambulatory visits and surgeries were temporarily canceled. There was a nation-wide migration to telehealth but with variable roll-out across medical facilities. There was also a concern that patients would electively avoid medical care due to worries about COVID-19 transmission risk.1,2 Subsequently, studies have documented reductions in emergency department visits,3,4 cancer screenings and treatments,5 elective and surgical procedures, regular check-ups, treatment for ongoing conditions, and preventive care.1 In a nationwide representative sample of U.S. adults aged 18 or older, it was estimated that about 41% of U.S. adults had electively avoided or delayed medical care during the pandemic because of concerns over the coronavirus.6,7 In these studies, racial/ethnic minorities, unpaid caregivers, and those with health insurance, disabilities, younger age, or chronic health conditions were more likely to delay care during the pandemic.7

While multiple studies have documented delays in medical care, key questions remain unanswered. First, we know less specifically about the experiences of older adults, a particularly vulnerable subpopulation that is both at high risk for COVID complications and from the negative consequences of delayed medical care. Second, while previous research have documented a rebound in emergency department visits8 and outpatient visits9, these data do not distinguish whether this rebound was due to recovery of delayed care or for new and acute medical issues; thus, it remains unknown whether delayed care was recovered at a later point in time and how care was recovered. Third, and most importantly, little is known about the degree to which older adults perceived that delayed medical care had negatively affected their health.

To address these questions, we use data from a cohort study on older adults. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) is an ongoing nationally representative longitudinal study of U.S. community-dwelling older adults. During the midst of the pandemic, NSHAP conducted a study to understand how older adults were impacted by the pandemic and incorporated a variety of questions about the overall experience of seeking medical care during the pandemic, including questions on delayed care, recovering delayed care, perceived health effects of delayed medical care, and current health status.

Using these data, we primarily aimed to characterize the extent of medical care delay among older adults as well as how much of the delayed care has since been recovered; we then estimated any perceived detrimental effect of delayed medical care on older adults’ health and wellbeing. We secondarily aimed to quantify the impact of the pandemic on self-rated physical health, regardless of medical care delays. Our study will provide a comprehensive overview of health care utilization among older adults during a global pandemic which may help us develop targeted interventions to address any unmet health needs. We also hope to understand the extent of perceived harm the pandemic has had on the older adult population beyond SARS-CoV-2 related illnesses and deaths to better prepare for these health consequences.

Data

We use data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP)’s COVID-19 study. NSHAP is an ongoing nationally representative longitudinal survey of community-dwelling U.S. older adults that began in 2005–06 with in-home interviews of a sample of 3,005 older adults aged 57–85. NSHAP conducts an additional round of data collection every five years. In 2010–11, surviving respondents were re-interviewed along with their spouses and cohabiting romantic partners. In 2015–16, NSHAP collected a third round of data with 4,777 respondents; surviving respondents were re-interviewed, and a second cohort of older adults aged 50–67 were enrolled in the study along with their partners and age-eligible household members.

In 2020–21, prior to the collection of NSHAP’s Round 4 data, a COVID-19 substudy was conducted to better understand U.S. older adults’ experiences during the pandemic. The sample for the COVID-19 study comprised of previous NSHAP respondents – 2,580 cohort 1 and 2,368 cohort 2 members. 96 cases determined to be deceased or hard refusals in prior rounds were removed from the sample, yielding a final eligible COVID-19 substudy sample of 4,852 respondents. Data for the COVID-19 study were collected between September 14, 2020 and January 27, 2021 using web, phone, and paper and pencil surveys. 2,672 individuals responded to the survey, resulting in a conditional response rate of 58.1% for both cohorts combined. Non-response rates were higher in those of older age, men, and poorer health, but did not differ by race/ethnicity. Additional details about sample recruitment and characteristics for each round of NSHAP data collection have been reported elsewhere.10,11,12

Methods

Primary Measures.

1) Delayed medical care: Medical care delay was measured by asking respondents whether they had experienced delays in needed medical, dental, or vision care since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Check all that apply: Yes, I delayed medical care; Yes, I delayed dental care; Yes, I delayed vision care; No). 2) Delayed care completion and mechanism: If respondents experienced delays in any type of care, they were then asked whether they had completed the care that was delayed (Yes, I completed all of it; Yes, I completed some of it; No, I completed none of it). If respondents had completed some or all their care, they were asked how they had completed their care (Check all that apply: By phone calls; By video calls; By emails, texts, or portal messages; By in-person visits to the doctor, dentist, or clinic; None of the above). 3) Impact of delayed care: Respondents who experienced delayed care were also asked whether they believed that the delayed care negatively affected their health (Yes; No; Don’t know). 4) Impact of the pandemic on health: To evaluate whether the pandemic had affected one’s physical health, all respondents were asked “Is your physical health currently better, worse, or about the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic?”

Covariates.

The sociodemographic variables gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, number of chronic conditions, and number of difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs) come from the NSHAP 2015–16 dataset. The age range for our analytic sample is 50–99; age was recoded into a categorical variable with age groups “<60,” “60–69,” “70–79,” and “80+.” The variable for race/ethnicity includes the categories “Non-Hispanic White,” “Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Black,” “Non-Black Hispanic,” and “Other.” Education was measured by highest degree completed using four categories (1 “Less than high school” 2 “High school/Equivalent” 3 “Vocational/Some college” 4 “Bachelor’s or more”). For the chronic illness measure, nine comorbid conditions (heart attack, stroke, dementia, coronary artery disease, arthritis, diabetes, cancer, congestive heart failure, emphysema) were totaled and recoded into “None,” “One,” “Two or more.” A score of one was assigned for any reported difficulty for each ADL, resulting in an ADL scale that ranged from 0–7.

Current self-rated mental and physical health, and levels of concern about the pandemic were assessed during the COVID-19 substudy. Reports of current self-rated physical and mental health include the categories “Excellent.” “Very Good,” “Good,” “Fair,” and “Poor;” “Fair” and “Poor” were recoded into a single category. Level of concern about the pandemic was assessed on a numeric rating scale ranging from 1 to 10, with higher numbers indicating more concern. Weighted descriptive statistics for all our measures appear in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics: Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics

| % | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <60 | 21.5 |

| 60–69 | 38.2 |

| 70–79 | 28.1 |

| 80+ | 12.3 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44.5 |

| Female | 55.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 79.8 |

| Black | 9.8 |

| Hispanic | 6.6 |

| Other | 3.8 |

| Education | |

| <High school | 6.6 |

| High school/Equivalent | 21.0 |

| Vocational/Some college | 36.0 |

| Bachelor’s or more | 36.4 |

| Self-rated mental health | |

| Excellent | 17.8 |

| Very good | 37.6 |

| Good | 32.5 |

| Fair/Poor | 12.2 |

| Chronic Illness | |

| None | 50.6 |

| One | 32.4 |

| Two or more | 17.1 |

| Self-rated physical health | |

| Excellent | 10.9 |

| Very good | 35.5 |

| Good | 36.8 |

| Fair/Poor | 16.8 |

| Mean (Range) | |

| Activities of daily living | 0.5 (0–7) |

| Concern about the pandemic | 7.5 (1–10) |

| N=2445 |

Table 2.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics: Medical Care Delay and Impact of Pandemic on Physical Health

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed medical care since pandemic started | 2,445 | |

| No | 67.2 | |

| Yes | 32.8 | |

| Has R completed care that was delayed?a | 762 | |

| Yes, I completed all of it | 29.6 | |

| Yes, I completed some of it | 46.9 | |

| No, I completed none of it | 23.5 | |

| Completed delayed care by phonea | 590 | |

| No | 73.9 | |

| Yes | 26.1 | |

| Completed delayed care by video calls/telehealtha | 590 | |

| No | 75.7 | |

| Yes | 24.3 | |

| Completed delayed care by emails, texts, or MyCharta | 590 | |

| No | 92.3 | |

| Yes | 7.7 | |

| Completed delayed care by in-person visitsa | 590 | |

| No | 12.2 | |

| Yes | 87.8 | |

| Did delayed care negatively affect health?a | 725 | |

| Yes | 17.6 | |

| No | 56.9 | |

| Don’t know | 25.5 | |

| Physical health currently better or worse as before the COVID-19 pandemic | 2,441 | |

| Better | 5.5 | |

| Worse | 10.2 | |

| About the same | 84.3 |

Note.

Respondents were only asked these questions if they reported they had delayed any type of care (medical, vision, and/or dental) during the pandemic.

Statistical Analysis.

We used a logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with delayed medical care (any medical care delays versus none). A multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with reporting perceived negative health effects from delayed medical care (no versus yes; and no versus don’t know). To determine characteristics associated with the likelihood of reporting worsened physical health during the pandemic, we used a logistic regression analysis (worse health versus about the same/better health). We included age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, current self-rated physical and mental health, level of concern about the pandemic, number of ADLs, and number of chronic conditions as covariates.

All analyses were conducted in Stata 15 (StataCorp., College Station, TX) using NSHAP’s round 3 survey weights, and statistical significance was determined with 95% confidence intervals. For the regression analyses estimating the odds of delayed medical care and of worsened physical health during the pandemic, the full sample was used; all other analyses were restricted to respondents who reported delayed medical care.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 provides weighted descriptive statistics of our full analytic sample (N=2,445). The mean age is 67.8; the largest age group in our sample was the 60–69 group (38.2%) while the 80+ group was the smallest (12.3%). There were more women (55.5%) in our sample than men (44.5%). 79.8% of our sample were White. A large proportion of our sample reported educational attainment of some college or more (72.4%). Only a minority reported fair/poor physical health (16.8%) and fair/poor mental health (12.2%). 50.6% reported having no chronic illness. The mean number of difficulties with ADLs was low (0.5) but mean level of concern about the pandemic was high (7.5).

Delayed Medical Care

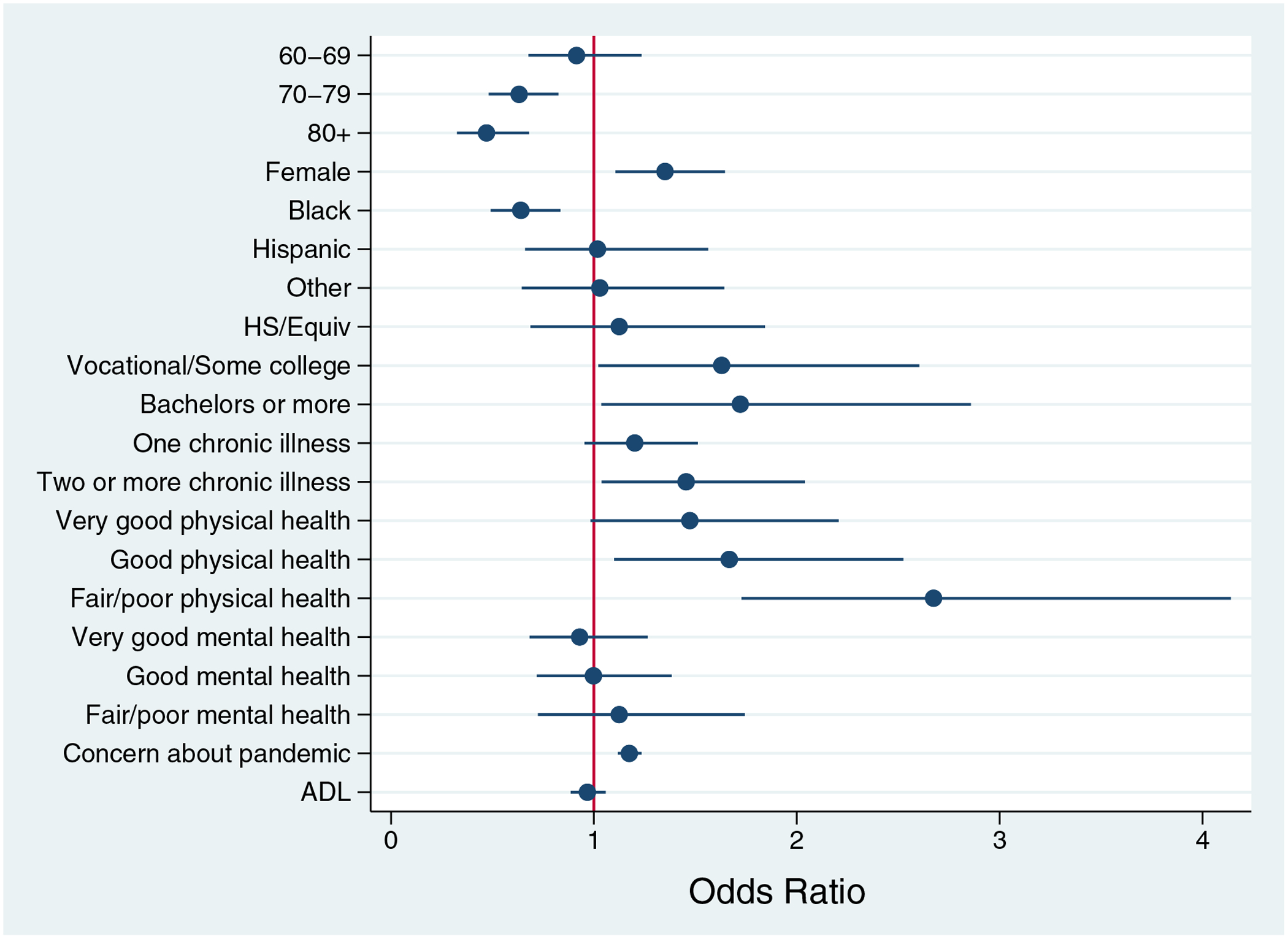

32.8% of older adults reported that their medical care had been delayed since the start of the pandemic (Table 2). Those who were in the 70–79 age group (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.48–0.83) as well as in the 80+ age group (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.33–0.68) were less likely to report delayed medical care than those younger than 60. Blacks (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49–0.83) were less likely to report delayed medical care than Whites. We found that women were more likely to report delayed medical care than men (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.11–1.65). Those with higher levels of education – having some college (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.02–2.60) and having bachelor’s or more (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.04–2.86) – were more likely to report delayed medical care than those with less than a high school degree. Older adults experiencing higher levels of concern about the pandemic (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.12–1.23), or have two or more chronic conditions (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.04–2.04) were also more likely to report delayed medical care. Those with worse self-rated physical health – good (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.10–2.53) or fair/poor health (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.73–4.14) – were more likely to report delayed medical care than those who had excellent health (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors Associated with Delayed Medical Care Among Older Adults, Odds Ratio

Note. Reference categories are: <60, Male, White, <HS, No chronic illness, Excellent physical health, Excellent mental health

Recovery of Delayed Medical Care

Among those who had experienced delayed medical care and responded to the question about care recovery (N=762), 23.5% reported that they still had not completed any of their medical care 6–10 months after the start of the pandemic. 46.9% reported that they had completed some of it, and only 29.6% had completed all their delayed medical care (Table 2).

Among older adults who completed at least some of their delayed medical care (N=590), an overwhelming majority of respondents (87.8%) completed their delayed care through in-person visits. Most older adults did not use remote health services to complete delayed care – only 26.1% reported completing delayed care by phone, 24.3% completed delayed care by video calls, and 7.7% completed delayed care by email, texts, or MyChart (Table 2).

Perceived Impact of Delayed Medical Care on Health

Among those who experienced delayed medical care and responded to the question about perceived negative health effects from delayed medical care (N=725), nearly one in five older adults (17.6%) believed that their delayed medical care had negatively affected their health and an additional 25.5% said they “don’t know” if delayed medical care had negative health effects (Table 2).

Those who had fair/poor self-rated physical health (RRR 5.51 95% CI 1.04–29.24) and fair/poor self-rated mental health (RRR 3.87, 95% CI 1.33–11.23) were more likely to report that delayed medical care had negatively affected their health in comparison to those with excellent health. Those who only completed some delayed medical care (RRR 4.29, 95% CI 2.28–8.06) or had completed none of their delayed medical care (RRR 4.83, 95% CI 2.21–10.57) were also more likely to report that delayed care had negatively impacted their health compared to those who were able to fully recover their delayed care (Table 3, Yes column).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Reporting Perceived Negative Health Impact from Delayed Care, Relative Risk Ratios

| Relative to No Perceived Negative Health Impact | Yes, RRR (95% CI) | Don’t know, RRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (ref. <60) | ||

| 60–69 | 0.99 (0.49 – 2.01) | 1.39 (0.83 – 2.32) |

| 70–79 | 1.05 (0.48 – 2.26) | 1.14 (0.64 – 2.04) |

| 80+ | 0.83 (0.37 – 1.86) | 0.71 (0.35 – 1.44) |

| Sex (ref. Male) | ||

| Female | 0.96 (0.59 – 1.57) | 1.22 (0.77 – 1.93) |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref. White) | ||

| Black | 1.62 (0.85 – 3.10) | 0.72 (0.30 – 1.69) |

| Hispanic | 1.38 (0.59 – 3.21) | 0.69 (0.28 – 1.72) |

| Other | 1.54 (0.39 – 6.09) | 0.59 (0.18 – 1.99) |

| Education (ref. <HS) | ||

| HS/Equivalent | 0.74 (0.22 – 2.44) | 1.31 (0.43 – 4.05) |

| Vocational/Some college | 0.86 (0.28 – 2.61) | 1.14 (0.40 – 3.30) |

| Bachelor’s or more | 0.57 (0.18 – 1.73) | 1.65 (0.55 – 5.00) |

| Self-rated mental health (ref. Excellent) | ||

| Very good | 1.12 (0.42 – 3.00) | 1.37 (0.66 – 2.83) |

| Good | 1.29 (0.55 – 2.98) | 1.53 (0.69 – 3.38) |

| Fair/Poor | 3.87 (1.33 – 11.23)* | 2.31 (0.83 – 6.44) |

| Chronic Illness (ref. None) | ||

| One | 1.07 (0.59 – 1.93) | 0.86 (0.51 – 1.44) |

| Two or more | 1.28 (0.68 – 2.39) | 0.88 (0.43 – 1.77) |

| Self-rated physical health (ref. Excellent) | ||

| Very good | 2.57 (0.46 – 14.24) | 1.06 (0.49 – 2.30) |

| Good | 3.80 (0.82 – 17.60) | 1.58 (0.66 – 3.74) |

| Fair/Poor | 5.51 (1.04 – 29.24)* | 2.42 (0.89 – 6.60) |

| Activities of daily living | 1.01 (0.86 – 1.18) | 0.91 (0.75 – 1.10) |

| Concern about the pandemic | 1.07 (0.92 – 1.23) | 1.06 (0.95 – 1.18) |

| Completed delayed care (ref. completed all delayed care) | ||

| Yes, I completed some of it | 4.29 (2.28 – 8.06)*** | 3.75 (2.24 – 6.28)*** |

| No, I completed none of it | 4.83 (2.21 – 10.57)*** | 5.73 (2.89 – 11.35)*** |

| N=718 |

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Additionally, we looked at factors that were associated with the likelihood of reporting uncertainty over whether delayed medical care had harmed one’s health (don’t know versus no). We found that older adults who had completed some (RRR 3.75 95% CI 2.24–6.28) or none of their delayed care (RRR 5.73 95% CI 2.89–11.35) were more likely to report that they do not know if delayed care negatively impacted their health in comparison to those who had fully recovered their care (Table 3, Don’t know column), indicating that incomplete delayed care either increased the risk of reporting perceived harm to health or increased the risk of reporting uncertainty about one’s health status.

Perceived Impact of the Pandemic on Physical Health

To further evaluate the effects of the pandemic on health, we looked at reports of self-rated changes in physical health during the pandemic compared to before it. 10.2% of all participants reported that their current physical health was worse than prior to the pandemic, 84.3% reported that physical health was about the same, and 5.5% reported that physical health was better (Table 2).

There were no differences in the odds of reporting worsened health between those who did not delay medical care and those who had delayed care but fully recovered delayed care. However, older adults who delayed care and had only recovered some delayed care (OR 1.93 95% CI 1.01–3.68) or delayed care and did not recover any delayed care (OR 2.55 95% CI 1.24–5.2) were more likely to report worsened physical health than those who had fully recovered their delayed care (Table 4). This suggests that delayed care itself does not necessarily negatively affect health – it is only when delayed care has not been fully recovered that leads to negative health consequences.

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Reporting Worse Physical Health (vs About the Same/Better) During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Odds Ratio

| OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Age (ref. <60) | |

| 60–69 | 0.79 (0.53 – 1.15) |

| 70–79 | 0.69 (0.41 – 1.13) |

| 80+ | 0.50 (0.27 – 0.91)* |

| Sex (ref. Male) | |

| Female | 1.16 (0.84 – 1.60) |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref. White) | |

| Black | 0.56 (0.34 – 0.91)* |

| Hispanic | 1.03 (0.49 – 2.18) |

| Other | 0.43 (0.13 – 1.44) |

| Education (ref. <HS) | |

| HS/Equivalent | 1.83 (0.84 – 4.00) |

| Vocational/Some college | 2.41 (1.06– 5.46)* |

| Bachelor’s or more | 3.05 (1.31 – 7.09)** |

| Self-rated mental health (ref. Excellent) | |

| Very good | 2.72 (1.24 – 5.96)* |

| Good | 3.32 (1.56 – 7.09)** |

| Fair/Poor | 4.95 (2.20 – 11.13)*** |

| Chronic Illness (ref. None) | |

| One | 1.04 (0.70 – 1.56) |

| Two or more | 0.89 (0.55 – 1.45) |

| Self-rated physical health (ref. Excellent) | |

| Very good | 1.22 (0.44 – 3.36) |

| Good | 2.75 (1.03 – 7.36)* |

| Fair/Poor | 6.96 (2.54 – 19.11)*** |

| Activities of daily living | 0.94 (0.82 – 1.07) |

| Concern about the pandemic | 1.11 (1.02 – 1.20)* |

| Compensated delayed medical care (ref. Delayed, fully compensated) | |

| No delay | 1.52 (0.81 – 2.88) |

| Delayed, partially compensated | 1.93 (1.01 – 3.68)* |

| Delayed, no compensation | 2.55 (1.24 – 5.22)* |

| N=2,430 | |

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Discussion

The unprecedented wide scale disruption of medical services during the COVID-19 pandemic has led to well-documented delays in medical care,6,7 which may have consequences for long-term population health. While a full accounting of the long-term health consequences of medical care delays due to the pandemic may require additional years of follow-up study, we believe that it is valuable to determine to what degree older adults believed that their delayed care had negatively affected their health and how many experienced worsened physical health during the pandemic.

First, in the NSHAP cohort, the risk of delayed medical care was not evenly distributed. Notably, having two or more chronic conditions and poorer self-rated health were associated with an increased likelihood of delayed medical care. It is concerning that older adults with worse objective and subjective measures of health were more likely to report delayed medical care. This particular group of older adults likely need more frequent health visits and perhaps are bearing the brunt of the consequences of the shift in medical care delivery during the pandemic. Because disturbed care could accelerate physical health declines among this group, it is imperative to target outreach to these older adults to increase their healthcare utilization.

Second, although delays in medical care during the pandemic has been widely reported, few studies have simultaneously examined the extent to which care has been recovered after an initial delay. Our results show that, reassuringly, 76.5% of older adults completed all or some of their delayed medical care 6–10 months into the pandemic. Although the rise of virtual care has been prominently reported during the pandemic, we found that most patients (87.8%) completed delayed care through in-person visits, and only about a quarter completed delayed care by phone or by video. Traditional forms of care may have played a more significant role during the pandemic than previously reported for this older segment of the population. Further research is needed to better understand if older adults prefer in-person visits over virtual care and whether the continued prominence of telemedicine during the pandemic hinders the ability of older adults to access healthcare.

Ultimately, the most important question is whether delays in care – recovered or not – have led to poor health outcomes; our evidence suggests that this appears to be the case for a minority of older adults. Among older adults who delayed medical care, 17.6% believed that the delayed care negatively affected their health and an additional 25.5% reported that they do not know if the delayed care had impacted their health. Having delayed care during the pandemic was not itself associated with reporting worsened physical health during the pandemic. However, delayed care that was not recovered was associated with increased odds of reporting worsened physical health during the pandemic. Our results highlight the importance of continuing to improve access to care recovery for older adults during the ongoing pandemic since it is the inability to complete delayed care, rather than the care delay, that is particularly worrisome.

Taken together, these subjective evaluations of declining health alert us to a potential increase in health problems among the older adult population. Unfortunately, we did not have clinical measures to examine whether there was an increase in specific types of health problems; further research using clinical measures could examine how delayed medical care and incomplete recovery for this care affect older adults’ trajectories of health, aging, and mortality, as well as whether they hasten physical and cognitive decline.

In sum, our study reveals that one-third of older adults had experienced delays in needed medical care during the pandemic but most have recovered these care delays, largely through in-person visits. However, a minority of older adults still had not recovered care 6–10 months into the pandemic. Those with lower physical and mental health and those with incomplete care recovery are the most likely to report experiencing negative effects from the delayed care. Furthermore, those with incomplete care recovery are also more likely to report worsened physical health during the pandemic. It is therefore imperative that we identify the minority of older adults who experienced care delays but have not recovered their medical care to increase access to health services among this group, as this group has experienced the largest negative health burden during the pandemic.

Limitations

While we were able to document the prevalence of and factors associated with medical care delay among a nationally representative sample of older adults, we did not have the data to identify the reasons why older adults delayed medical care. It is unknown whether older adults delayed medical care out of fear of exposure to the coronavirus, because appointments were canceled, or because health care facilities were overburdened by COVID cases and experienced reduced capacity; additionally, we did not have data to determine what types of medical services were delayed. Other studies should identify the reasons for and types of delayed care and whether health facilities have expanded their capacity to allow us to develop targeted strategies to increase the use of health services among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study is limited by data collection during a single time point in the pandemic, roughly 6–10 months into the pandemic. It is likely that older adults have continued to recover their delayed care as clinics have increased capacity. Subsequent follow-up on the status of care recovery needs of older adults would help to determine whether and when care recovery has been achieved.

The survey was fielded prior to the availability of vaccines; differences in vaccination status may shape the trajectory of health recovery, completion of delayed care, and further care delays as the SARS-CoV-2 virus continues to mutate and spread. Additional research assessing vaccination status may be needed to fully understand patterns of healthcare utilization among older adults.

Lastly, we use data from a sample of community-dwelling older adults, which excludes those who are institutionalized and in poorer health, so our results may underestimate the prevalence of delayed care and its potential negative health consequences among older adults. Moreover, because there was less participation from minorities in NSHAP’s COVID-19 substudy, our estimates of delayed care and patterns of recovery may not capture variations in access to healthcare by race during the pandemic. Further research is needed to understand the patterns of healthcare utilization among minority communities during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Understanding how older adults experienced the impact of delayed medical care during the global pandemic is crucial to promote effective healthcare delivery to this vulnerable population, especially since unrecovered delayed care can lead to negative health consequences. Healthcare systems have adopted telemedicine to provide medical services to the population during the pandemic, yet telemedicine may not be the most effective way of delivering care to older adults. To encourage healthcare utilization among older adults during the ongoing pandemic, clinics may need to increase availability of in-person appointments, provide options for in-home care, and to increase efforts to contact older adult patients for health services.

The U.S. has largely been able to help patients maintain access to healthcare during the pandemic and was able to limit delays; nonetheless, a small segment of older adults had persistently delayed medical care and reported perceiving a negative impact on their health. To mitigate potentially grave health effects, strategies must be developed to identify and reach vulnerable patients in the upcoming months.

Key Points.

One-third of older adults experienced medical care delays during the pandemic.

Nearly one in five older adults who experienced delayed medical care reported perceiving that their health was negatively affected by the care delay.

Older adults with worse self-rated physical and mental health or who had not fully recovered delayed care were more likely to report perceived negative health impacts from the care delay.

Why does this matter?

With most attention primarily directed at SARS-CoV-2 related illnesses and deaths, less is known about the health consequences of delayed medical care during the pandemic, particularly among older adults who may need additional healthcare services to maintain health and wellbeing. Understanding the extent of medical care delays and its potential health consequences can allow healthcare providers to prepare for the potential increase in health problems among this subpopulation following the pandemic.

Acknowledgements

Funding:

This work and the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (PI: Linda Waite) were supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01AG021487, R37AG030481, R01AG033903, R01AG043538, R01AG048511, R01AG060756, and K24DK105340). The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project COVID-19 study reported here (PI: Louise Hawkley) was conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number AG043538-08S1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts.

References

- 1.Findling MG, Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Delayed care with harmful health consequences—reported experiences from national surveys during coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Health Forum 2020;1:e201463. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whaley CM, Pera MF, Cantor J et al. Changes in health services use among commercially insured US populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2024984. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janke AT, Jain S, Hwang U et al. Emergency department visits for emergent conditions among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69:1713–1721. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun C, Dyer S, Salvia J, Segal L, Levi R. Worse cardiac arrest outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Boston can be attributed to patient reluctance to seek care. Health Aff 2021;40:886–895. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patt D, Gordan L, Diaz M et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: How the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2020;4:1059–1071. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson KE, McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Barry CL. Reports of forgone medical care among US adults during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2034882. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns — United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1250–1257. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannouchos TV, Biskupiak J, Moss MJ, Brixner D, Andreyeva E, Ukert B. Trends in outpatient emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic at a large, urban, academic hospital system. Am J Emerg Med 2021;40:20–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterji P, Li Y. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient providers in the United States. Med Care 2021;59:58–61. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Muircheartaigh C, Eckman S, Smith S. Statistical design and estimation for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64B:i12–i19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Kwok PK. Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69:S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Schumm LP. Sample design and estimation in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: Round 3 (2015–2016). J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2021;76:S207–S214. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]