Abstract

Background

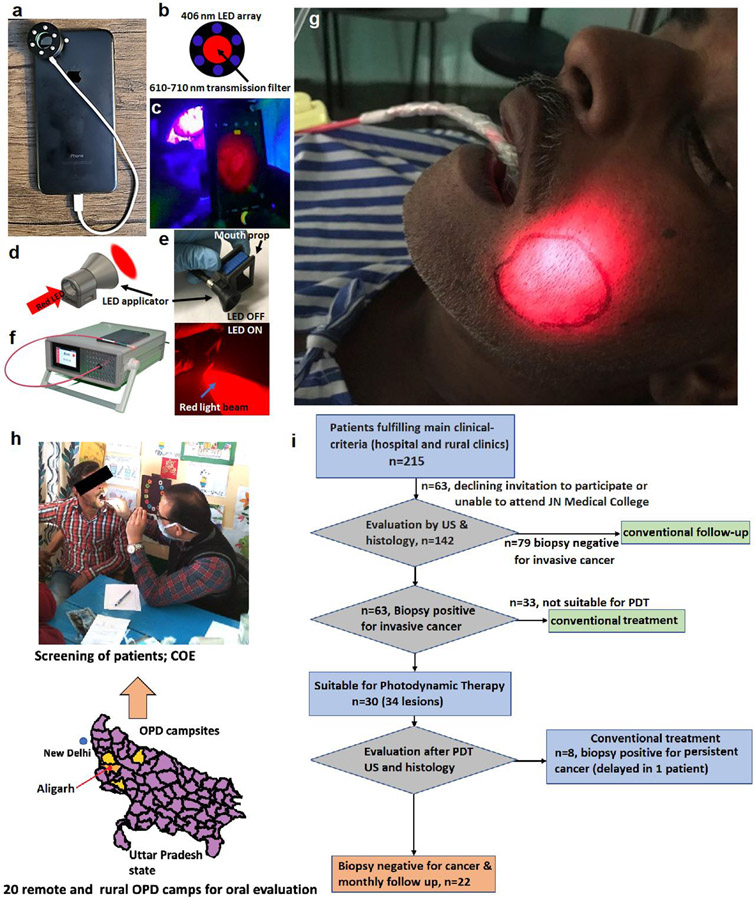

Morbidity and mortality due to oral cancer in India are exacerbated by a lack of access to effective treatments among medically underserved populations. We developed a user-friendly low-cost, portable fibre-coupled LED system for photodynamic therapy (PDT) of early oral lesions, using a smartphone fluorescence imaging device for treatment guidance, and 3D printed fibreoptic attachments for ergonomic intraoral light delivery.

Methods

30 patients with T1N0M0 buccal mucosal cancer were recruited from the JN Medical College clinics, Aligarh, and rural screening camps. Tumour limits were defined by external ultrasound (US), white light photos and increased tumour fluorescence after oral administration of the photosensitising agent ALA (60 mg/kg, divided doses), monitored by a smartphone fluorescence imaging device. 100 J/cm2 LED light (635 nm peak) was delivered followed by repeat fluorescence to assess photobleaching. US and biopsy were repeated after 7-17 days. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03638622, and the study has been completed.

Findings

There were no significant complications or discomfort. No sedation was required. No residual disease was detected in 22 out of 30 patients who completed the study (26 of 34 lesions, 76% complete tumour response, 50 weeks median follow-up) with up to 7.2mm depth of necrosis. Treatment failures were attributed to large tumour size and/or inadequate light delivery (documented by limited photobleaching). Moderately differentiated lesions were more responsive than well-differentiated cancers.

Interpretation

This simple and low-cost adaptation of image-guided PDT is effective for treatment of early-stage malignant oral lesions and may have implications in global health.

Funding:

US National Cancer Institute

Keywords: Early Oral Cancer, PDT, Low cost treatment, India

Background

Oral cancer represents more than 30% of cancers in India, where an exceptionally high incidence of oral disease is driven by widespread chewing of carcinogenic products.1, 2 Conventional management of advanced disease with surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy is expensive and often not available.3 This programme set out to identify and treat these cancers at an earlier stage in low resource areas, so reducing the number of patients progressing to advanced disease.

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) provides local treatment of cancers with light after prior administration of a photosensitising drug. It is minimally invasive and repeatable4, and achieves some degree of tumour selectivity.5 With no increase in tissue temperature, collagen is preserved and treated tissues like oral mucosa heal with remarkably little scarring. It was first reported for oral cancer in 1984 using the photosensitiser HPD (haematoporphyrin derivative).6 For low resource regions, the photosensitising agent ALA (5-aminolaevulinic acid, metabolised in vivo into the photosensitiser protoporphyrin 9, PpIX) is much more convenient as it can be administered orally or topically, the drug light interval is a few hours (rather than days) and there is no prolonged skin photosensitivity. Used topically, ALA PDT is well established for premalignant lesions on the skin and in the mouth.7 ALA given systemically was first reported for oral cancer in 1993.8 The only comparable report since showed that the depth of necrosis in early oral cancers was limited to 1.3 mm.9 Detailed review of this study suggested that the results might be improved by refinements of the protocol, particularly related to light delivery. Separate laboratory studies on transplanted pancreatic cancers in hamsters showed that ALA PDT could produce necrosis to a depth of 8mm,10 so it was considered appropriate to think again on its potential for early oral cancer and to proceed with the present study, focusing on light delivery.

Most work on PDT for oral cancer has used lasers,5 equipment not available in low resource areas, where the disease is most prevalent. In 2014, the NCI funded this development of a low cost PDT platform for early oral cancer in India. If successful, it is envisaged that this approach could be extended to other conditions with high prevalence in low resource areas, such as CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia). The non-laser light source developed, based on a high power LED (output centred on 635 nm, for activation of PpIX), is powered by a conventional electricity supply or a lithium-ion polymer rechargeable battery. With either, the output is stable, appropriate for clinical use, and shown experimentally to produce the same biological effect as a laser centred at the same wavelength. The output is coupled to a 1mm flexible fibreoptic delivery system with fibre tip adaptors designed for intra-oral light delivery.11-13

The extent of a lesion to be treated must be defined to ensure adequate light delivery. Tumours sensitised with systemic ALA fluoresce in the red more than adjacent tissue on activation with blue light, a simple way to estimate the extent of surface disease.14 This can be done using a smartphone.15, 16 For the present study, a standard smartphone has been modified to observe and quantify this fluorescence and the photobleaching after light delivery that acts as a surrogate marker to monitor PDT light dose. Fluorescence is excited by an array of 405 nm LED’s mounted around the phone camera, and viewed and recorded through a 610-710 nm emission filter over the camera lens (Fig. 1a,b,c,d,e,f).17 Assessment of this device was undertaken in parallel with the present report, which describes the first clinical validation study.

Fig. 1.

(a) Modified smartphone with fluorescence attachment, (b) Ring of blue LED’s (to activate fluorescence) with a red filter over lens, (c) Imaging oral mucosa, showing fluorescence image on camera, (d) Light applicator for fibre tip, (e) Emitted red light beam from mouth prop attached light applicator, (f) LED light source and delivery fibre for PDT, (g) Treatment of buccal mucosa carcinoma. (h) Clinical oral evaluation (COE) of early oral cancer and flow chart for 215 patients selected as potentially suitable for the trial on clinical grounds. There are 20 rural screening camps spread over 4 districts of Western Uttar Pradesh state of India, shown in yellow (Administrative map data file taken from Global Administrative Areas or gadm.org. The file was executed in R.). These camps were up to 200 km./124miles away from JNMC, Aligarh. (i) Flow chart for patients considered for trial.

Methods: clinical validation

Recruitment and Procedures

The study was based in the Departments of Radiotherapy and Clinical Oncology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India. This hospital treats around 400 oral cancer patients per year. All patient studies were conducted according to local institutional guidelines. Approval was given by the Dana Farber /Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and by the India Council of Medical Research. Permission was given to treat 30 patients (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT03638622).

Participants were recruited from patients referred to the ENT clinic of the JN Medical College and from outreach camps, screening for oral cancer in rural areas. Inclusion was limited to buccal mucosa lesions, stage T1N0M0, in easily accessible sites.18 Other key inclusion criteria were HPV negative, no active infections (HIV, Tuberculosis, hepatitis, oral herpes), and no serious or systemic illnesses considered to render the patient unsuitable (details in supplementary data S1). Ultrasound examination of the mouth (puffed cheek technique) measured the mucosal extent of disease and depth of invasion. The guidelines for inclusion were depth up to 5 mm and width up to 20 mm. Patients meeting these criteria and willing to participate were given written, audio, and video information and asked for written consent. The ultrasound measurements defined the area of mucosa to be treated and were used to evaluate the smartphone-based fluorescence imaging approach which was evaluated as part of this study.

PDT Procedure

Patients were admitted to hospital the afternoon before PDT for intravenous rehydration to minimise the risk of hypotension after administration of the photosensitizer precursor ALA (DUSA Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Wilmington, MA), which leads to accumulation of the photoactive product protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). The next day the patient was given an antibacterial mouth wash to reduce bacterial flora (which may fluoresce and overlap with the ALA-induced PpIX fluorescence)19 together with a prophylactic antiemetic and analgesic. No sedation was required. Photos of the lesion were taken in white light and autofluorescence of the area including the lesion imaged, both using the smartphone, followed by the first dose of ALA, 20 mg/kg, dissolved in fruit juice. Two further doses were given at hourly intervals (total dose 60 mg/kg over 2 hours) and fluorescence imaging repeated 15-30 minutes after the 3rd dose.

Light delivery started shortly after acquiring the second fluorescence image. Only buccal mucosa lesions were treated using a 3D printed applicator with appropriate positioning piece depending on lesion position, as described previously,18 to hold the fibre between the teeth adjacent to the treatment site. During light delivery, patients were seated in a dental chair and closed their mouth around the optical fibre. A small sucker was made available to aspirate saliva, if required. The applicator was positioned so the full extent of the lesion and a surrounding rim of at least 5 mm of normal tissue was covered (Fig.1g).

Treatment time was calculated based on the LED power available (maximum 170 mW) and the area to be treated to deliver a total dose of 100 J/cm2 at an irradiance of 33 to 54 mW/cm2 at the lesion surface for all patients. During illumination, a break of 2 minutes every 10 minutes gave the patient a rest and enabled a check on the applicator positioning. This break likely also gave tissue an opportunity to reoxygenate.20-22 The total duration of light delivery varied from 30-50 minutes (depending on the irradiance achieved) requiring 3, 4, or 5 fractions. Eye safety goggles are not required for LED light sources.

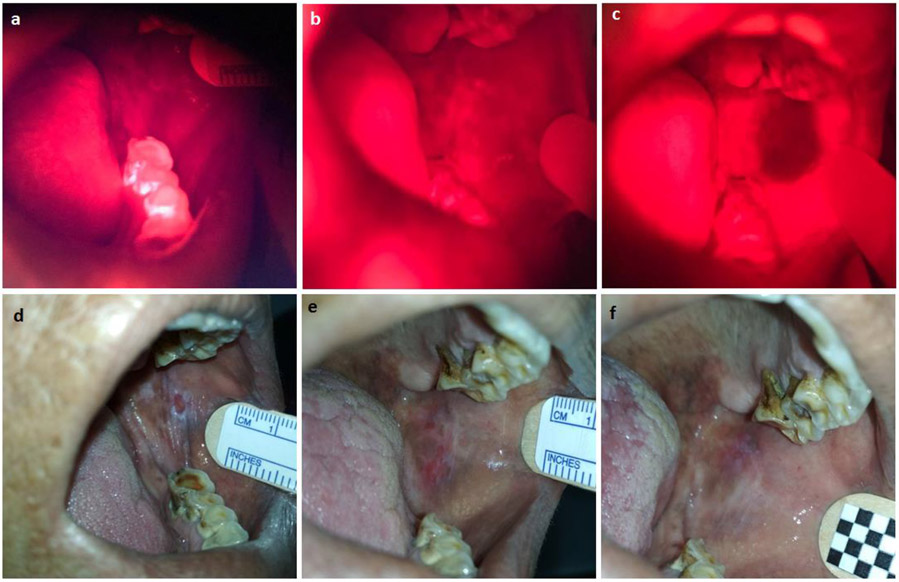

When light delivery was complete, the fibre and applicator were removed, and a further smartphone fluorescence image was obtained. The three fluorescence images for each patient, before ALA, after ALA, and after light delivery, were later analysed to map the areas where fluorescence had increased after ALA administration for correlation with ultrasound and white light measurements and to document photobleaching after light delivery, as a measure of the adequacy of the light dose delivered (Fig. 2). (image analysis and statistical method details in supplementary material S2).

Fig. 2.

White light and fluorescence images of a patient with successful PDT (follow up 81 weeks without recurrence). Fluorescence images: (a) Auto-fluorescence (prior to administration of ALA), (b) 15 mins after 3rd dose of ALA, before light, (c) Immediately after completion of light delivery (56% reduction in fluorescence due to photobleaching). White light images: (d) Before PDT, (e) 10 days after PDT, (f) 3 months after PDT.

Post-treatment management

Patients stayed in the hospital overnight, protected from bright light for 24 hours. Liver and renal function tests were checked the following day and the patient was discharged, to return after 7-15 days for repeat ultrasound, biopsy, and blood tests. Those with persistent disease were offered conventional treatment outside the trial. Those with no evidence of persistent disease were followed up in the outpatient clinic.

Results

Patient recruitment and presenting symptoms

A total of 215 patients were considered potentially suitable based on reviewing clinical notes related to their buccal lesions, but many were excluded due to other exclusion cirteria, as described above. Many from rural outreach clinics lived too far from Aligarh to be able to participate due to the cost, lack of help to look after family at home etc and reluctance to go to a big city for what many patients with early disease thought was a minor problem and a potentially uncomfortable, procedure. Further data is shown in the (Fig.1.h) and flow chart (Fig1.i). Many patients first seen in Aligarh had disease too advanced for consideration for this trial. 30 patients were recruited, 25 from the Hospital ENT clinic, 5 from rural outreach clinics (26 men, 4 women). All had been chewing tobacco and/or related carcinogenic products (bidi, gutka, khaini, katechu) for many years (range 7-42 years, median 21, mean 22). At diagnosis, they had had symptoms for 2-48 months (median 6, mean 9). The main symptoms were ulceration, white patches (suspicious of pre-malignant change), and nodules or induration of the buccal mucosa. In addition, 11 patients complained of pain from the lesion or a burning sensation on eating spicy food, nine had trismus (five requiring a Heister gag to enable light delivery), two had pain in the ear, one had tinnitus and one had a discharge from an ulcer.

Clinical results

34 buccal mucosal lesions were treated in 30 patients. 13 were located anteriorly, 16 posteriorly, four near the RMT (retromolar trigone), and one near the buccal sulcus. 27 lesions had no evidence of cancer in biopsies taken 7-17 days after PDT. One of these patients presented 28 weeks later with a swollen cheek and induration in a white patch adjacent to the treated area, confirmed as invasive cancer with local and lymphatic spread. No patient had nodal spread at presentation. It is likely that the post PDT biopsy had been too superficial. No recurrent cancer was detected in the other 26 lesions during a mean follow up of 54 weeks (range 14-141, median 50) although 18 patients still had evidence of dysplasia in these first post-PDT biopsies, warranting careful follow-up.

Patients had remarkably little discomfort during or after the procedure. Two had discomfort during light delivery; two had difficulty holding the applicator in their mouth (both related to limited mouth opening); one became hypotensive, rapidly reversed by intravenous rehydration; four had nausea and vomiting after PDT; one had a mild headache. The other 20 had no problems. No patient had any photosensitivity. Some had discomfort due to inflammation in the treated area for a few days, readily controlled with oral analgesics. Minor abnormalities were noted in the liver and renal function tests after ALA, which rapidly returned to normal without intervention. Although some mild collagenization was seen, no patients noticed any restrictions of jaw movement related to the PDT. A few patients showed mild scarring in the treated area soon after PDT, which had resolved in subsequent examinations.

The additional presenting symptoms resolved in all patients who had successful PDT (eight of 11 with mouth pain, six of nine with trismus (some with help from a Heister gag and mouth opening exercises), one of two with ear pain, one with tinnitus. The one with a discharging ulcer failed PDT. Failed PDT cases went on to have conventional treatment.

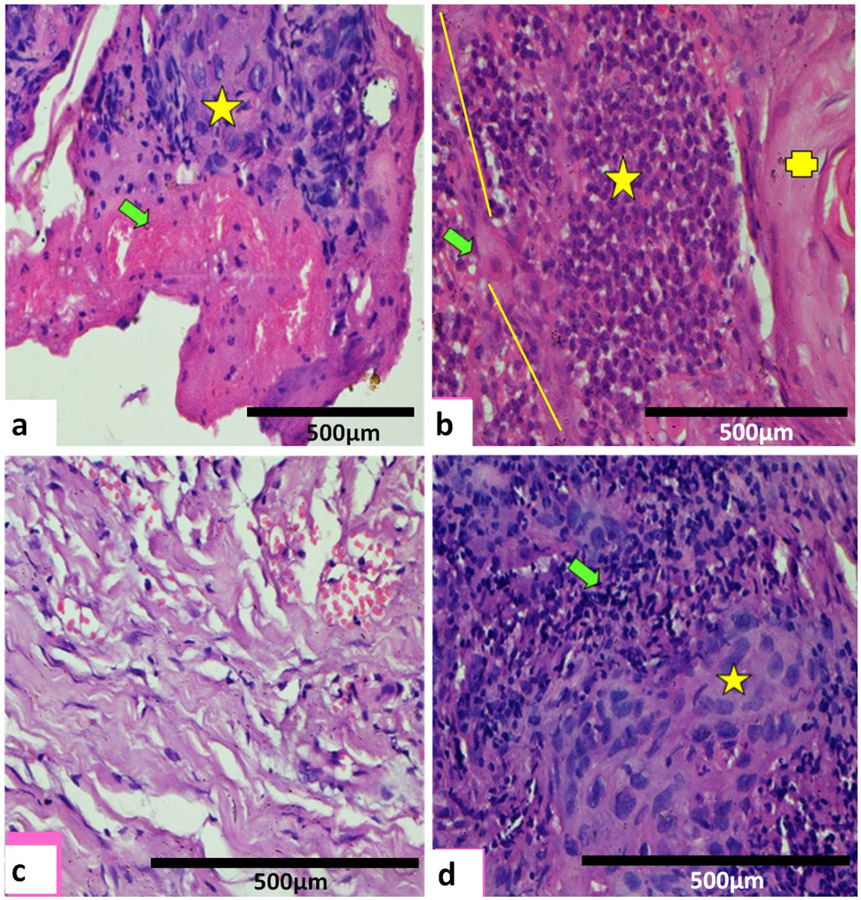

Seven patients had persistent tumour in the first post-PDT biopsy. The patient with persistent disease at 28 weeks is also included in this group as it is likely that cancer was missed in his first post PDT biopsy. These lesions were located anteriorly one (of 14), posteriorly five (of 16), and near the RMT two (of four). One was lost to subsequent follow up, two had excisional biopsies with complete clearance of tumour, one had radiotherapy and is doing well, two had wide local excisions (one with clear resection margins, one requiring further treatment). Two (including the 28-week recurrence) had progressive disease, with limited response to further treatment, for whom ultimately only palliative treatment could be offered (see the supplemental details of treatment failure patients, S3). Histology findings are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

(a) 10 days after PDT. Zonal necrosis with necrotic foci (green arrow) adjacent to viable tumour (yellow star) with clearly defined margin. Lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with mildly congested vessels. H & E x100). (b) 8 days after PDT. Marked lymphocytic cell infiltrate (yellow star) at the junction (yellow line) with necrosed moderately differentiated carcinoma. A few apoptotic bodies (green arrow) and normal keratinized tissue (yellow cross). No evidence of viable tumour. (H & E x100). (c)14 days after PDT. No evidence of persistent carcinoma. Healing seen with mild to moderate scarring by collagenisation (H & E x100). (d) Six months after PDT. Persistent/recurrent moderately differentiated carcinoma not seen on 1st follow up after PDT. Viable tumour cells (yellow star) with dense pyknotic nuclei, intense eosinophilic cytoplasm with partial tumour necrosis, prominent apoptotic bodies and marked lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (green arrow). (H & E x100).

Correlation of diagnostic and monitoring techniques

Ultrasound (US)23-25 23-25 23-25 23-25

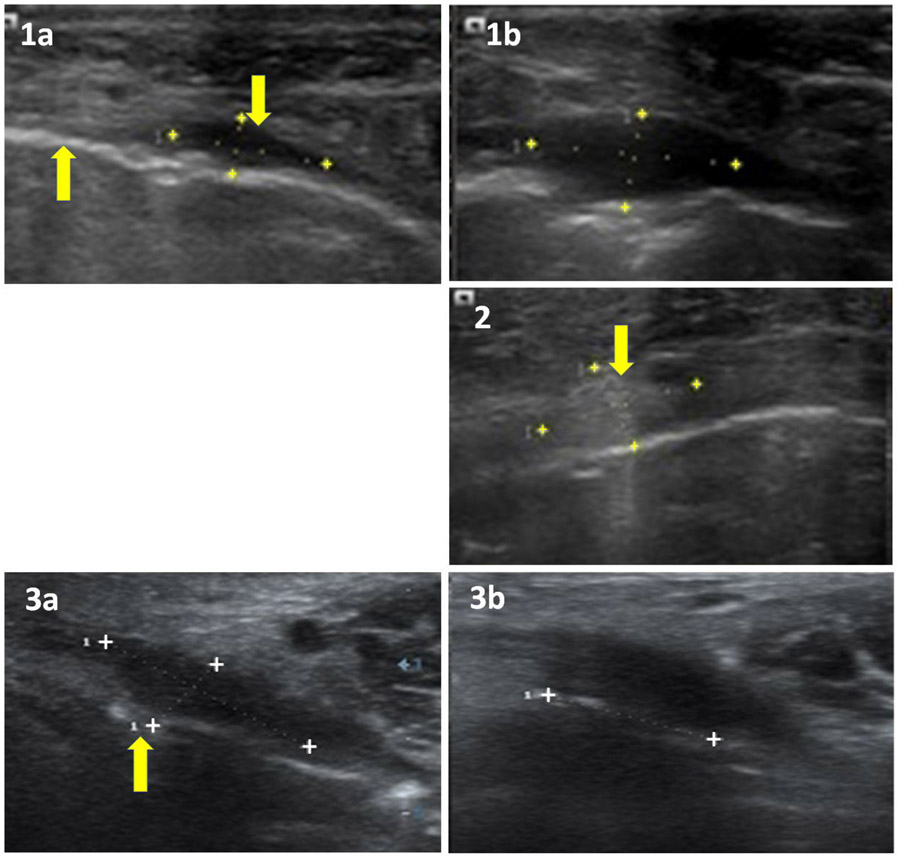

These US23-25 examinations were undertaken from outside the mouth through the cheek (puffed cheek technique), and the results used as the definitive measurements on which the area to be treated was decided (Table 1).

Table 1.

US lesion dimensions for successful and failed PDT.

| Depth (mm) | Length (mm) | Volume (mm3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDT Successful | 4.9 (range 2-7.2) | 10.9 (range 3.2-22) | 174 (range 17-473) |

| PDT Failed | 5.0 (range 3.1-8.6) | 12.4 (range 5.0-17.2) | 344 (range 75-568) |

In all successful cases, at least some changes were seen on post-PDT US (oedema, inflammation, and/or necrosis). One lesion healed completely. In contrast, on five of the failures, no changes could be identified, suggesting there had been no PDT effect. The scans of 3 of the failures were also markedly more echogenic than those on any other patients (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

US Scans (1a) before and (1b) 9 days after PDT. Maximum lesion dimensions increase from 9.8x8.3x3.6 mm to 13.1x13.2x6 mm due to necrosis and oedema and patient is well at 31 weeks. An arrow up: echogenic mucosa, arrow down: hypoechoic lesion in submucosa. (2) Scan before PDT: an arrow shows Echogenic lesion in submucosa, 10.6x9.7x5.9 mm, unchanged after PDT (Treatment failure). (3) Scan (3a) before and (3b) 4 weeks after PDT during healing. Maximum lesion dimensions have fallen from 14x13x5 mm initially to 11x11x5 mm 7 days after PDT (not shown) to 9x9x3 mm after 4 weeks. An arrow (3a) shows breech in echogenic mucosa below hypoechoic lesion and patient is well at 39 weeks.

Fluorescence monitoring

Lesion dimensions

Three measures were made of the surface extent of disease in the mouth prior to PDT: US, white light measurement, and the area of increased fluorescence after administration of ALA. The results from the three measures are compared in Fig. 5. Only US could also measure the depth of pathology.

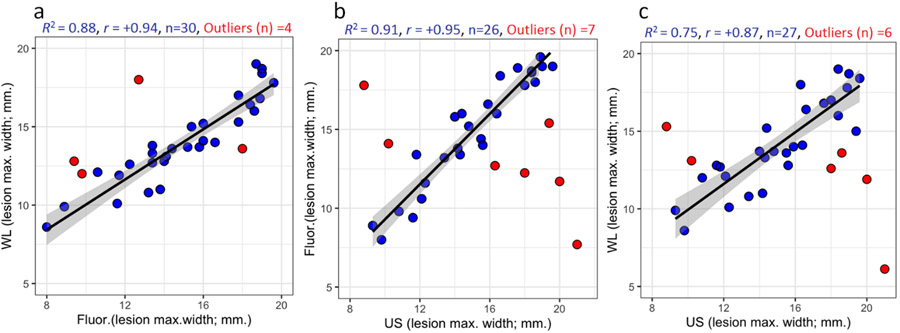

Fig. 5.

Regression-correlation of the maximum extent of cancer on the buccal mucosal surface as measured by white light and fluorescence with the maximum extent of disease measured by US in the buccal mucosal plane.26 (a) White light v Fluorescence, (b) Fluorescence v Ultrasound, (c) White Light v Ultrasound. (US scans not available for one lesion).

For 26 lesions, there was a remarkably good regression correlation between smartphone fluorescence and US measurements (regression coefficient of determination; R2 = 0.91, Pearson’s coefficient; r = +0.95). In seven cases, the correlation was unsatisfactory. These outliers were identified as reported previously using influence plot analysis based on a combination of Hat-values, Studentized residual values, and Cook’s value with R2 = 0.75 as a criterion for satisfactory correlation.17 In five of these (out of 20 patients who presented with an ulcerated lesion), the US showed a larger lesion than fluorescence, possibly because cells on the surface of an ulcer may be necrotic and so produce less PpIX or because the maximum extent of disease was below the mucosal surface and so only detected by US. In another two outliers (from ten lesions presenting with an ulcer and other white patches), the lesion was larger on fluorescence, most likely because the white patches were immediately adjacent to the main lesion and were neoplastic, so PpIX was generated over a larger area.26 Likewise, the correlation of white light measurements with US was good for 27 lesions (R2 = 0.75, r = +0.87) although not as strong as the correlation between fluorescence and US, with six outliers (four showing a larger lesion on US, likely due to submucosal disease and two with immediately adjacent white patches that would not be seen on US). Five of the outliers for the white light and fluorescence correlations with US were the same lesions. As expected, the correlation between white light photos (same smartphone camera without the fluorescence attachment) and fluorescence was also good (R2 = 0.88, r = +0.94).

Photobleaching

In all cases, the maximum diameter of tissue bleached27 was greater than the original maximum diameter of fluorescence from the tumour, as expected, as the area treated included a surrounding ring of normal tissue. However, on average, the difference between the maximum diameter of bleaching and the original lesion diameter was 13.8 mm (mean, range 8.3-18.9) in PDT failures, compared with 10.9 mm (mean, range 3.8-19.1), in successful cases, a difference of 60% in the area treated. Light scattered over a larger area, most likely due to poor positioning of the light applicator, meant less light absorbed in the tumour area, suggesting that inadequate light could have contributed to the treatment failures.

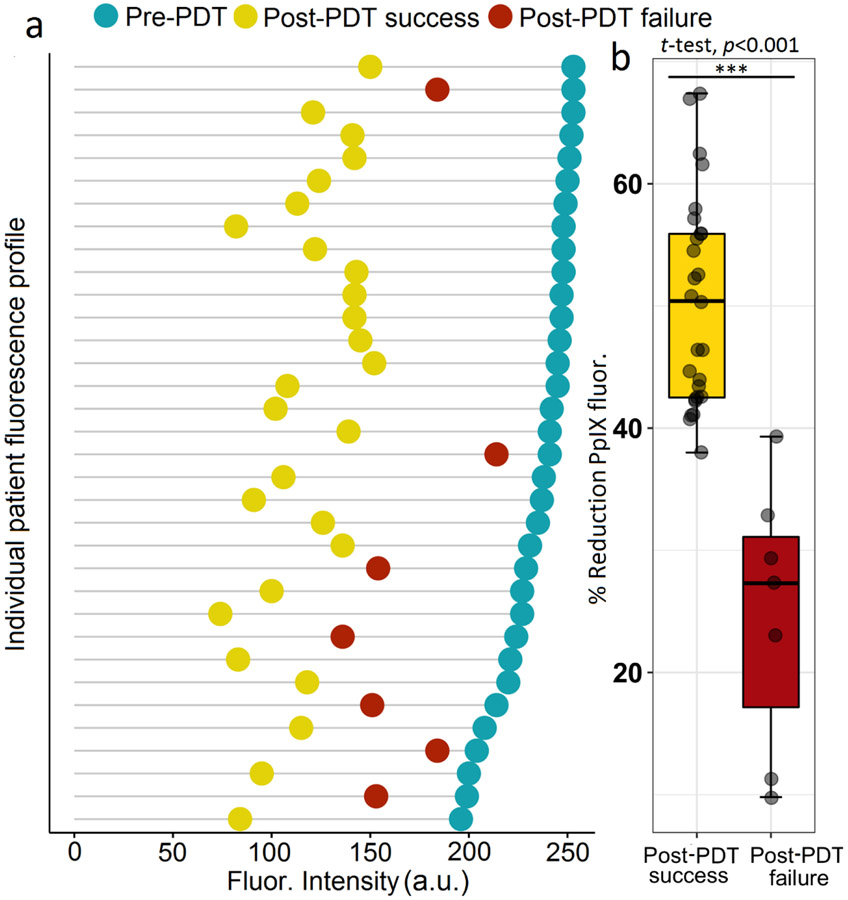

Measurements of the decrease in fluorescence in the tumour area (photobleaching) after light delivery support this explanation. The degree of photobleaching for all seven lesions that showed persistent tumour in the first biopsy after PDT was less than that of all but one of the lesions which exhibited successful complete tumor response. The percentage fluorescence change in the failed cases averaged 25 %, whereas in the successful cases, the average was 50 % (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6.

(a) Cleveland’s dot plot of Photobleaching. Each line shows the fluorescence before (blue) and after (yellow for PDT success and red for PDT failure) light delivery for individual patients (n=34 lesions, t =18.58, p < 0.001). (b)Box plot of PpIX fluorescence reduction. Analysis of the change in PpIX fluorescence from images acquired before and after PDT reveals a strong positive correlation between the extent of photobleaching and treatment outcome. (n=34, t=6.7, p<0.001). All PDT treatment failures had less photobleaching than all but one of those with successful PDT.

Reasons for failed PDT

Photobleaching data indicates that inadequate light delivery was the major factor in failed treatments. However, there are other factors. The depth of the tumour missed at the first follow-up was 8.6 mm, considerably above the guideline depth of 5 mm, so undoubtedly, this lesion was too large for ALA PDT. Partial necrosis of this lesion is seen in Fig. 3d. On two other failed lesions (3.1 and 3.2 mm thick) convincing evidence of a PDT effect was seen on US, but the reduction in fluorescence was only 23% and 27%, suggesting inadequate light.

For the other five failures, the photobleaching was limited in two (10% and 11%), so inadequate light undoubtedly contributed. However, no PDT changes could be observed on US on any of these five. Three of these lesions were more echogenic on US than those associated with responsive cases. All five were well-differentiated cancers at presentation, out of only seven well-differentiated cancers in the trial. In contrast, there were only three failures in the 27 other lesions (all moderately differentiated). Further, on post-PDT biopsy, four of these five lesions showed moderately differentiated cancers rather than the well-differentiated lesions reported prior to PDT.

The number of lesions treated was only 34, so it is difficult to draw firm conclusions on presentation as to which lesions are most likely to respond, but in addition to the comments above, this experience suggests that anterior and mid-buccal lesions do better than posterior and retromolar lesions (easier light delivery, as is also true for those without trismus); single lesions with mucosal irregularity (ulcer or nodule) fail PDT more frequently (6 of 11 cases) compared with those showing several discrete lesions or white patches. One of the 2 patients with ear pain failed PDT.

We conclude that treating the area of mucosal disease seen on ultrasound, with a depth no more than 5 mm, together with a 5mm rim of surrounding normal tissue and documentation of adequate light delivery (at least 50% reduction in fluorescence after light delivery) is appropriate. We cannot explain the relatively higher sensitivity to PDT of moderately differentiated compared to well differentiated lesions. That will require further study.

Discussion

Much clinical research has focused predominantly on new drugs and techniques (often of high cost) for disease management in advanced health services. This NCI funded project has shown firstly that ALA PDT for early oral cancer can be considerably more effective than has previously been reported (maximum depth of necrosis 7.2 mm compared with 1.3 mm)9 mainly due to improved light delivery with consequence of possible photodynamic priming28, and also that it can be delivered at low cost in areas with limited infrastructure.

PDT was approved in Europe for advanced oral cancer using mTHPC when all else has failed as early as 2001, and there has been evidence of its efficacy for early lesions for many years.29 The technique is straightforward and safe. PDT with ALA, as used in this study, is comfortable for the patient without the need for sedation and with minimal side effects. It avoids the prolonged cutaneous photosensitivity associated with photosensitisers like mTHPC, leaves little in the way of scarring and is repeatable, which is rarely possible after chemotherapy, surgery or radiotherapy. Surgeons, oncologists and radiotherapists in more affluent areas seem reluctant to add PDT to their armamentarium although the value of PDT in the overall management of oral cancer is being increasingly recognised.29

This study has opened new doors. It was an obvious development to use LED’s as the light source, but it required some ingenuity to develop a cheap, battery-operated device that could deliver enough light for clinical use via a flexible fibre and was small enough to be transported by bicycle to remote areas. A comparable LED device has been developed in Brazil but that does not have a fibre delivery system.20. The noted absence of pain in the present study may be attributed to the relatively low irradiance used (range 34-54mW/cm2). In the earlier oral cancer study9, the intensity varied from about 60-250mW/cm2 (K.Fan personal communication) and the pain increased from minimal to severe as the intensity increased. Pain is an important consideration if PDT is to be delivered in low resource areas. The problem has been reviewed recently.30 Our results are consistent with the results of previous studies of ALA PDT for actinic keratoses31 and superficial basal carcinomas32 in which pain was significant at 75 mW/cm2 but minimal at 60 mW/cm2 or below.

There are many millions of smartphones in India. Using a simple smartphone-mounted device to image photosensitiser fluorescence for delineation of lesions and treatment monitoring is a logical low-cost imaging option. The patient already has ALA on board for the PDT, so there are no additional drug costs. There was a good correlation between white light, fluorescence, and ultrasound for measuring the extent of disease. Empirically, estimation of lesion size from fluorescence, in which the lesion is simply a brighter spot against a dimmer background, was generally found to be more rapid and robust than size estimates from white light images, which required more subtle and subjective interpretation of local variations in tissue colour and texture. Further, being able to correlate more than one measurement of the surface area of tumour is reassuring, especially for less experienced clinical teams. The results of this study indicate that this simple smarphone-based fluorescence imaging approach is sufficiently reliable to guide light delivery in cases where lesions are not clearly visible from white-light imaging. Of course assessment of the depth of the lesion will still be important in identifying patients who are good candidates for PDT and ultrasound is likely to be the most convenient option. New basic and mobile ultrasound equipment may soon become available that can be used in remote areas.

Little change in treated areas is seen under white light until a day or two after PDT. Quantifying photobleaching is the only technique to give an immediate measure on the adequacy of the delivered light dose, so more light can be delivered during the same treatment session if required. Photobleaching has been widely explored as a way of monitoring PDT in real time27, but the smartphone is a particularly attractive way of doing this.17

Conclusions

Of the 30 patients in this study with T1N0M0 buccal mucosal cancers, 22 (26 lesions) had a complete response with good healing and without loss of function after a single PDT treatment. Eight failed, mainly due to inadequate light. Lesions in other parts of the mouth could be treated with appropriate light applicators.

It is anticipated that with increasing numbers of screening “camps” in rural areas, more early lesions will be identified. Chewing oncogenic agents produces field change effects. Treated patients will remain at risk of metachronous disease. Being able to offer screening and follow-up to be accompanied, when required, by a simple treatment associated with minimal discomfort, in their own village, should encourage patients with early symptoms to come forward rather than waiting until more advanced disease has developed. These results should stimulate larger clinical trials establishing low-cost PDT as a global health strategy, and expanding to cancers at other anatomical sites.33 For India, the next step is to see if these techniques can indeed be used safely and effectively in rural clinics. Overnight hospital stays can be avoided by rehydration on the treatment day and careful advice on photosensitivity. This approach has considerable potential to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer and the costs of managing this unpleasant disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Low-cost technology for photodynamic therapy (PDT) treatment of oral cancers

Complete tumor clearance following a single PDT treatment in 22 out of 30 patients.

Intraoral PDT suitable as a day case procedure in rural, resource-limited clinics.

PDT is well tolerated, with minimal pain and excellent healing of mucosa.

A simple smartphone-based imaging device was validated for treatment guidance.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded entirely from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grants UH2 CA1889901 and UH3 CA1889901 to Tayyaba Hasan and Jonathan P. Celli). This support is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Mumbai, India (via DUSA pharmaceuticals) for providing the 5-ALA used in this study. We are grateful for clinical investigation assistance and productive conversations with Dr. Sayema of the Department of Radiodiagnosis, together with Professor S. C. Sharma, Dr. Sheikh Abdul Zeeshan and Dr. Abdur Rahman of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology (E.N.T.), of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, AMU, Aligarh, India.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Data sharing

Protocol and deidentified participant data will be available after publication after approval of a proposal with a signed data access agreement.

References

- 1.Coelho KR. Challenges of the oral cancer burden in India. Journal of cancer epidemiology 2012; 2012: 701932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodu B, Jansson C. Smokeless tobacco and oral cancer: a review of the risks and determinants. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine 2004; 15(5): 252–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. Oral cancer prevention and control–the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral oncology 2009; 45(4-5): 454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Straten D, Mashayekhi V, De Bruijn HS, Oliveira S, Robinson DJ. Oncologic photodynamic therapy: basic principles, current clinical status and future directions. Cancers 2017; 9(2): 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant WE, Speight PM, Hopper C, Bown SG. Photodynamic therapy: an effective, but non-selective treatment for superficial cancers of the oral cavity. International journal of cancer 1997; 71(6): 937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wile AG, Passy V, Novotny J, Berns MW, Mason GR. Photoradiation therapy of head and neck cancer. American journal of clinical oncology 1984; 7(1): 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Dan H, Tang F, et al. Photodynamic therapy guidelines for the management of oral leucoplakia. International journal of oral science 2019; 11(2): 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant W, MacRobert A, Bown S, Hopper C, Speight P. Photodynamic therapy of oral cancer: photosensitisation with systemic aminolaevulinic acid. The Lancet 1993; 342(8864): 147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan KF, Hopper C, Speight PM, Buonaccorsi G, MacRobert AJ, Bown SG. Photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid for premalignant and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 1996; 78(7): 1374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regula J, Ravi B, Bedwell J, MacRobert A, Bown S. Photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolaevulinic acid for experimental pancreatic cancer–prolonged animal survival. British journal of cancer 1994; 70(2): 248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hempstead J, Jones DP, Ziouche A, et al. Low-cost photodynamic therapy devices for global health settings: Characterization of battery-powered LED performance and smartphone imaging in 3D tumor models. Scientific reports 2015; 5: 10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallidi S, Mai Z, Rizvi I, et al. In vivo evaluation of battery-operated light-emitting diode-based photodynamic therapy efficacy using tumor volume and biomarker expression as endpoints. Journal of biomedical optics 2015; 20(4): 048003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Daly L, Rudd G, et al. Development and evaluation of a low-cost, portable, LED-based device for PDT treatment of early-stage oral cancer in resource-limited settings. Lasers in surgery and medicine 2019; 51(4): 345–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celli JP, Spring BQ, Rizvi I, et al. Imaging and photodynamic therapy: mechanisms, monitoring, and optimization. Chemical reviews 2010; 110(5): 2795–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uthoff RD, Song B, Sunny S, et al. Point-of-care, smartphone-based, dual-modality, dual-view, oral cancer screening device with neural network classification for low-resource communities. PLoS One 2018; 13(12): e0207493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giller G Using a smartphone to detect cancer. SciAm 2014; 310(5): 28-. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan S, Hussain MB, Khan AP, et al. Clinical evaluation of smartphone-based fluorescence imaging for guidance and monitoring of ALA-PDT treatment of early oral cancer. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2020; 25(6): 063813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallidi S, Khan AP, Liu H, et al. Platform for ergonomic intraoral photodynamic therapy using low-cost, modular 3D-printed components: design, comfort and clinical evaluation. Scientific reports 2019; 9(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamad LO, Vervoorts A, Hennig T, Bayer R. Ex vivo photodynamic diagnosis to detect malignant cells in oral brush biopsies. Lasers in medical science 2010; 25(2): 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramirez DP, Moriyama LT, de Oliveira ER, et al. Single visit PDT for basal cell carcinoma–A new therapeutic protocol. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 2019; 26: 375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regula J, MacRobert A, Gorchein A, et al. Photosensitisation and photodynamic therapy of oesophageal, duodenal, and colorectal tumours using 5 aminolaevulinic acid induced protoporphyrin IX--a pilot study. Gut 1995; 36(1): 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curnow A, Mcllroy BW, Postle-Hacon MJ, MacRobert AJ, Bown SG. Light dose fractionation to enhance photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid in the normal rat colon. Photochemistry and photobiology 1999; 69(1): 71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakasugi-Sato N, Kodama M, Matsuo K, et al. Advanced clinical usefulness of ultrasonography for diseases in oral and maxillofacial regions. International journal of dentistry 2010; 2010: 639382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smiley N, Anzai Y, Foster S, Dillon J. Is Ultrasound a Useful Adjunct in the Management of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2019; 77(1): 204–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchi F, Filauro M, Iandelli A, et al. Magnetic Resonance vs. Intraoral Ultrasonography in the Preoperative Assessment of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in oncology 2020; 9: 1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betz CS, Stepp H, Janda P, et al. A comparative study of normal inspection, autofluorescence and 5-ALA-induced PPIX fluorescence for oral cancer diagnosis. International journal of cancer 2002; 97(2): 245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pogue BW, Sheng C, Benavides JM, et al. Protoporphyrin IX fluorescence photobleaching. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2008; 13(3): 034009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Silva P, Saad MA, Thomsen HC, Bano S, Ashraf S, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy, priming and optical imaging: Potential co-conspirators in treatment design and optimization—A Thomas Dougherty Award for Excellence in PDT paper. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines 2020; 24(11nl2): 1320–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meulemans J, Delaere P, Vander Poorten V. Photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer: Indications, outcomes, and future prospects. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery 2019; 27(2): 136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ang JM, Riaz IB, Kamal MU, Paragh G, Zeitouni NC. Photodynamic therapy and pain: A systematic review. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 2017; 19: 308–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apalla Z, Sotiriou E, Panagiotidou D, Lefaki I, Goussi C, Ioannides D. The impact of different fluence rates on pain and clinical outcome in patients with actinic keratoses treated with photodynamic therapy. Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine 2011; 27(4): 181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cottrell WJ, Paquette AD, Keymel KR, Foster TH, Oseroff AR. Irradiance-dependent photobleaching and pain in δ-aminolevulinic acid-photodynamic therapy of superficial basal cell carcinomas. Clinical cancer research 2008; 14(14): 4475–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillemanns P, Garcia F, Petry KU, et al. A randomized study of hexaminolevulinate photodynamic therapy in patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1/2. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015; 212(4): 465. e1–. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.