Abstract

Leishmaniasis is a disease that represents a serious global health problem with a potentially fatal outcome in some cases. Leishmania spp. is transmitted by the bite of a sandfly and the disease is endemic in 98 countries. Treatment is carried out with toxic drugs and not consistently effective, so there is a need for new treatments. Oxadiazoles are five-membered heterocyclic compounds, and their antileishmanial activity is well documented in the literature. Specifically, n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b) was designed to obtain the simplified molecular data line entry system (SMILES). The approach for predicting pharmacokinetic properties used was pkCSM—Pharmacokinetics and ADME/TOX parameters were achieved. SMILES of 2b and Amphotericin B (ANF B) were submitted to the server and the results were compared. The cytotoxic action of 2b on host cells (LLC-MK2) was also evaluated, using MTT salt and antileishmanial activity against Leishmania infantum promastigotes at different concentrations for 24 h. The molecule 2b studied here demonstrated low toxicity in LLC-MK2 cells even at the highest concentration (1000 µM) with cell viability of 69%. Furthermore, it demonstrated anti-L. infantum action with cell viability of 13% at the highest concentration (1000 μM), while (ANF B) (16 μg/mL) demonstrated cell viability of 7%, justifying the need for further studies with n-cyclohexyl-1.2,4-oxadiazole employing experimental models of leishmaniasis.

Keywords: Leishmania infantum, Oxadiazoles, ADME/TOX, Cytotoxicity

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a tropical and subtropical disease caused by the parasite Leishmania spp., which is transmitted to man by the bite of a sandfly. It is one of the seven most critical tropical diseases representing a severe global health problem, presenting a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations with a potentially fatal outcome. It is found on all continents except Oceania and is endemic in circumscribed geographic areas such as Northeast Africa, Southern Europe, Middle East, Southeast Mexico, and Central and South America (Torres-Guerrero et al. 2017).

Due to the lack of up-to-date drugs, leishmaniasis is a neglected disease. There are three different clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis: cutaneous (skin), mucosal (mucous membrane), and visceral (the most severe form affecting the internal organs) (WHO 2020). The treatment of leishmaniasis has been carried out with pentavalent antimonials such as Glucantime®, which is the first-choice drug in Brazil. These drugs are toxic, not consistently effective, and can be used for long periods. The main side effect of Glucantime® is its action on the cardiovascular system, which may present repolarization disorders. For alternative treatments in Brazil, Amphotericin B, and its liposomal formulations, pentamidines and immunomodulators are used (BRASIL 2006; Neves et al. 2011).

Regarding the in silico pharmacokinetic prediction, optimization of ADME-Tox properties (absorption, distribution, excretion, metabolism, and toxicity) is a process in discovering and optimizing new pharmaceutical compounds. Some essential parameters of in vivo experiments, such as pharmacokinetics and specific toxic effects, can be estimated by these properties. (Wenzel et al. 2019).

Oxadiazoles are five-membered heterocyclic compounds containing one oxygen atom and two nitrogen atoms. Its high importance is highlighted by many applications in various scientific areas, for example, the pharmaceutical industry, drug discovery, scintillating materials, and the dye industry (Salahuddin et al. 2017). The antileishmanial activity of oxadiazole-based compounds is also well documented in the literature. Phenyl-linked oxadiazol-phenyl-hydrazone hybrids synthesized by Taha et al. (2017) were evaluated for in vitro antileishmanial potential. It was reported one of these compounds as the most potential candidate with an IC50 value = 0.95 ± 0.01 µM, being seven times more potent than the standard drug used, Pentamidine (IC 50 = 7.02 ± 0.09 µM), demonstrating the efficiency of compounds containing oxadiazole derivatives. Thus, more studies with molecules based on oxadiazole seeking an alternative treatment for leishmaniasis are necessary due to the worldwide public health problem that we face with this disease.

Materials and methods

Parasites

Promastigote forms of Leishmania infantum (MHOM/BR/1974/PP75) were donated by the Biological Collection of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC), Fiocruz, Brazil and kept in culture conditions for the in vitro experiments. The promastigotes were kept in supplemented Schneider medium (LGC Tecnologia) in a BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) incubator at 25 °C, following the growth curve of the logarithmic phase of the parasite.

Molecule used in the study

The n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole molecule (2b) used in this study was synthesized according to de Oliveira et al. (2018).

ADME/TOX in silico pharmacokinetic prediction

Initially, the oxadiazole 2b molecule was designed to obtain the SMILES (simplified molecular input line entry system) is a chain notation used to describe the nature and topology of molecular structures. Amphotericin B (ANF B) was used as drug control, and was obtained its Canonical SMILES through PubChem. The approach for predicting pharmacokinetic properties used was pkCSM—Pharmacokinetics, which is based on graphic-based signatures. The web server is available at http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/. The SMILES of each drug were presented to the server and compared to each other.

Effect of 2b molecule on promastigote forms

Different concentrations of 2b molecule (15.6 to 1000 μM) diluted in 1% Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) were used. The volume in each well of the 96-well plate was 200 µL (40 µL of each molecule and 160 µL of the parasite). Briefly, promastigote forms of the parasite in a culture bottle with Schneider medium were transferred to a sterile plastic tube and centrifuged for 15 min at 700×g. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 1 mL of supplemented Schneider medium. Parasite counting was performed in a diagonal Neubauer Chamber, diluting the samples in Trypan Blue and formalin. A concentration of 107 parasites was then plated and distributed in a sterile 96-well plate; then, 2b molecule was added and after 24 h the counts were carried out in the Neubauer chamber. Parasite’s viability was expressed as percentage (%) compared to the promastigotes incubated in medium (control). ANF B (16 μg/mL) was used as death positive control.

Viability on host cells

The evaluation of the cell viability of Rhesus monkey kidney epithelial cells (LLC-MK2 cell line) after incubation with the 2b molecule was performed using the MTT salt (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide). Confluent cultures were maintained in DMEM medium (Dulbecco MEM Medium) for 24 h, without Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), washed, trypsinized, and centrifuged at 1792 xg for 5 min. Cell density was adjusted to 105 cells/mL and transferred to a 96-well flat-bottom plate. Then the cells were further 24 h incubated (5% CO2, 37 °C) with oxadiazol 2b at different concentrations (15.6 to 1000 µM). After that, 100 μL were removed from each well, and 10 μL of MTT solution (2.5 mg/mL in PBS) was added. The plates were incubated for 4 h (5% CO2, 37 °C) and 90 μL of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) were added. After another incubation period (17 h) at room temperature, the plates were gently shaken and read at 570 nm in a spectrophotometric reader. As a negative control, only cells incubated in culture medium with 0.5% of DMSO (diluent) were used. As previously adopted by our group and also by (Hariharakrishnan et al. 2009; Miranda et al. 2013; Bate et al. 2020) no death positive control (LLC-MK2 cells only incubated with DMSO, SDS or Triton X-100 at high concentrations) was assayed. Cells’ viability was expressed as percentage (%) compared to the negative control.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Instat, applying the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey test in analysis of variance with a determination of the significance level for p < 0.05 through multiple comparisons.

Results

In silico prediction of n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b)

Some achieved results are relevant when evaluating the ADME/TOX properties of oxadiazole (2b) by pkCSM—Pharmacokinetics with reference values. According to these shown in Table 1 it was possible to predict that the oxadiazol 2b in question has a low aqueous solubility (− 4254 log.mol/L), high cell permeability (1342 logPapp 10–6 cm/s), good intestinal absorption (93.534%) and relevant volume of distribution (0.445 logL/kg). Besides this, it has an acidic character due to not being a substrate of P-glycoprotein and has a low distribution to the central nervous system (CNS) with permeability to the blood–brain barrier of 0.109 log BB, and − 2776 log PS of CNS permeability. Regarding metabolization, the result of the prediction of 2b shows that it presents itself as a potential inhibitor of the CYP1A2 and CYPC19 enzymes. In excretion, oxadiazole presents a moderate value for its total elimination (0.798 log ml/min/kg). Finally, it shows hepatotoxicity and toxicity in Tetrahymena pyriformis (1035 log µg/L).

Table 1.

ADME/TOX parameters’ values of n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b) and Amphotericin B (ANF B) generated by the pkCSM Pharmacokinetics server

| Evaluation parameters | 2b | ANF B | Unit | Reference values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Aqueous Solubility | − 4.254 | − 2.937 | log.mol/L | – |

| Cell Permeability (Caco2) | 1.342 | − 0.597 | log Papp 10−6 cm/s | High > 0.90 | |

| Intestinal Absorption (Human) | 93.534 | 0 | % absorption | Low < 30% | |

| P-Glycoprotein Substrate | No | Yes | – | – | |

| Distribution | Distribution Volume (human) | 0.445 | -0.37 | log L/kg | High > 0.45 |

| Permeability to the blood–brain barrier (BBB) | 0.109 | -2.058 | log BB | > 0.3 crosses the BBB | |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) Permeability | − 2776 | − 3.718 | log PS | – | |

| Metabolism | Cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 Inhibitor | Yes | No | – | – |

| Cytochrome P450 CYPC19 Inhibitor | Yes | No | – | – | |

| Excretion | Total Elimination | 0.798 | − 1.495 | log ml/min/kg | – |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | No | – | – | |

| Toxicity | Toxicity in T. pyriformis | 1.035 | 0.285 | log µg/L | Toxic > 0.5 |

Pharmacokinetic prediction from the pkCSM Pharmacokinetics server of the compound n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b) as well as the reference drug used in the study (Amphotericin B)

2b molecule displays anti- L. infantum in vitro effect

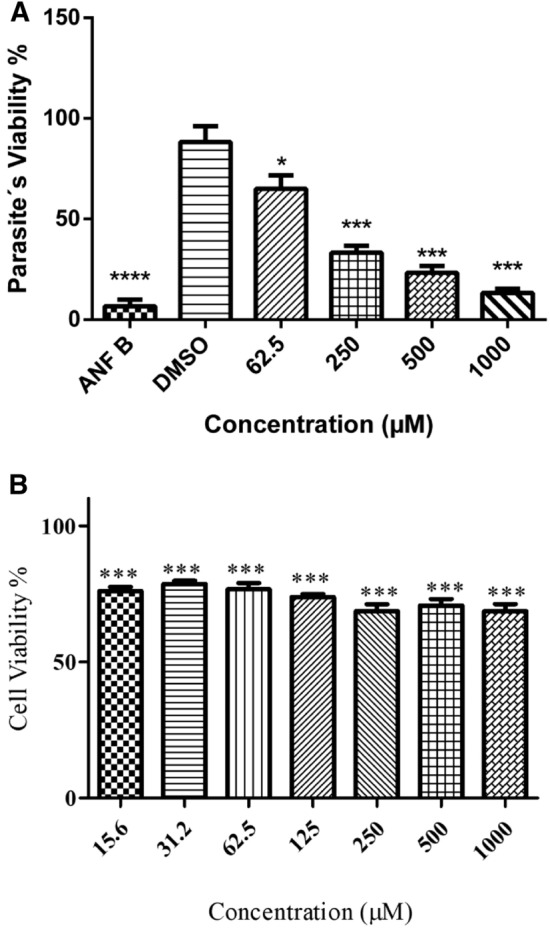

The potential antileishmanial effect of compound 2b was evaluated on the promastigote forms of L. infantum for 24 h. It showed relevant antipromastigote activity compared to the reference drug at highest concentration. With 1000 µM of 2b the cell viability was 12%, while with 16 µg/ml of (ANF B), the cell viability was 7% (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Effects of n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol (2b) on the promastigote forms of L. infantum and LLC-MK2 cells after 24 h. A Promastigostes were cultured in supplemented Schneider medium and incubated with Amphotericin B (16 µg/mL) (death control); DMSO (1%) (diluent control); Different concentrations (62.5 to 1000 µM) of n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b). B LLC-MK2 cells were cultured DMEM medium and incubated with different concentrations (15.6 to 1000 µM) of n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole (2b). Data are expressed as mean ± SD from two different experiments; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group (untreated promastigotes/host cells)

2b molecule does not display relevant toxicity for LLC-MK2 cells

LLC-MK2 cells were used to assess the cytotoxic effects of the 2b molecule as a host cell model for L. infantum infection and treated at different concentrations using the MTT assay. The results obtained in Fig. 1B showed moderate toxicity in host cells, even at the highest concentrations (1000 µM) with cell viability of 69%, demonstrating that oxadiazole did not show relevant toxicity, as previously demonstrated (Karakas et al. 2017).

Discussion

The oxadiazole molecule (2b) used in this study has a high Caco-2 cell permeability of 1.342 log Papp 10–6 cm/s. The predicted result also reveals high intestinal absorption with 93,534% and low aqueous solubility (− 4254 log.mol/L), predicting that n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole is fat-soluble and that the oral route could be used (Ballard et al. 2012; Hubatsch et al. 2007; Ungell 2004). Once absorbed, drugs are transported freely or bound to plasma proteins in the bloodstream. Acids bind albumin, and basics bind alpha-1-glycoprotein or lipoproteins. According to the data presented, it is possible to infer that oxadiazol has an acidic character and binds to albumin since it is not a substrate for P-glycoprotein. For a drug with high tissue binding, little of the drug remains in the circulation. Oxadiazol 2b has a volume of distribution of 0.445 log L/kg, considered high by the reference value, and will soon be able to exert its action on tissues (Batchelor and Marriot 2015). The value for CNS permeability of 2b is low, − 2776 log PS (Takashima et al. 2011).

The main pathways involved in drug metabolism are divided into phase I or phase II reactions. Phase I reactions involve oxidation, reduction, and hydroxylation processes, with CYPs (cytochrome P450 enzymes) being the most relevant group of drug-metabolizing enzymes. The result of the prediction of oxadiazol 2b shows that it presents itself as a potential inhibitor of the CYP1A2 and CYPC19 enzymes. CYP1A2 is involved with caffeine and paracetamol, while CYPC19 is involved in the metabolism of many proton pump inhibitors and antiepileptics, and it is necessary to evaluate their drug interaction with oxadiazol 2b (Kearns et al. 2003; Van Den Anker et al. 2011). In the context of drug hepatitis, toxic metabolites are formed from the original compound by CYP-450 enzymes, potentially causing a tissue injury by covalent modification of liver macromolecules through the generation of free radicals and/or increasing the levels of hepatic enzymes (AST, ALT, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase) (Massolla et al. 2018). On the other hand, liver involvement in Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL) is considered in the background, mainly affecting kupffer cells, which their function in hepatic metabolism is still unknown (Ding et al. 2004; Franciscato 2010).

Regarding the in vitro assays conducted, the promastigote forms of L. infantum were susceptible to oxadiazol 2b, which had a potential antileishmanial effect, mainly at the highest concentration (1000 μM), with 13% cell viability, matching the positive control Amphotericin B at 16 μg/mL with 7% cell viability. Parasite cultures treated with only 1% DMSO did not show significant effects. Thus, the observed activity cannot be attributed to the presence of DMSO in the cultures. The results obtained against the LLC-MK2 cell line showed low cell toxicity, even at the highest concentrations (1000 µM) with 69% cell viability, demonstrating that oxadiazole did not show relevant toxicity.

The antileishmanial action mechanism of oxadiazol 2b may involve proteases present in the parasite, such as the cysteine protease. These enzymes allow the perpetuation of parasites within their hosts, as they activate survival mechanisms and can be explored as potential pharmacological targets (Michels and Avilán 2011). Cysteine proteases (CPs) may be involved in favoring the Th2 response, leading to degradation of class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules of the host macrophage, with a consequent increase in the expression of IL-4 and IL-1, which direct the differentiation of CD4 + T cell precursors to the T helper cell phenotype 2 (Th2). Such effects generated by the protozoan CPs favor the proliferation of the parasite (Mottram et al. 1998). Furthermore, Almeida (2017) showed a promising compound with antileishmanial activity in vitro and in vivo in L. infantum based on oxadiazole (furoxanic 14e), with an ability to inhibit the cysteine protease, donating nitric oxide and interrupting the life cycle of the parasite. These results reinforce the potential antileishmanial effect of compounds derived from oxadiazoles.

Conclusion

The n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole showed a relevant pharmacokinetic prediction with low aqueous solubility (− 4254 log.mol/L), high cell permeability in Caco2 (1342 log Papp 10–6 cm/s) and good intestinal absorption (93.534%), demonstrating that it can be administered orally. It demonstrated a relevant volume of distribution (0.445 logL/kg), inferring that it will be able to exert its pharmacological function, an acidic and liposoluble character, soon being transported by albumin, also revealed a low distribution to the CNS with permeability to the blood–brain barrier of 0.109 log BB and -2776 log PS of CNS permeability. It presented itself as a potential inhibitor of the enzymes CYP1A2 and CYPC19, being necessary to evaluate further a possible drug interaction with caffeine, paracetamol, proton pump inhibitors, and antiepileptics.

In vitro assays showed low toxicity in LLC-MK2, even at the highest concentration (1000 µM) with cell viability of 69%. Regarding antileishmanial activity, oxadiazol 2b was shown to be as efficient as the reference drug Amphotericin B, thus justifying the need for further studies with n-cyclohexyl-1,2,4-oxadiazole against leishmaniasis.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Authors’ contributions

CVGP conducted the experiments and YMR assisted in in vitro experiments and LLC-MK2 assay. JPVR assisted in silico experiment and revised the English language. MJT collaborated to the in vitro experiments. RNO synthesized and provided the oxadiazole molecule. WMBS and NVS guided the conduction of the article’s writing. RN concepted the idea, supervised the entire study as well as guided the students.

Funding

This study was funded by Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) (Grant VPPIS-001-FIO-18-55), Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação em Desenvolvimento Tecnológico e Inovação (PIBITI-FIOCRUZ) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (Grants Numbers 448082/2014-4, PQ 301308/2017–9).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Almeida LD (2017) Leishmanioses e derivados de furoxano e benzofuroxano: atividade biológica in vitro e in vivo e potenciais mecanismos de ação

- Ballard P, Brassil P, Bui KH, Dolgos H, Petersson C, Tunek A, Webborn PJ. The right compound in the right assay at the right time: an integrated discovery DMPK strategy. Drug Metab Rev. 2012;44(3):224–252. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2012.691099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor HK, Marriott JF. Pediatric pharmacokinetics: key considerations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(3):395–404. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate PNN, Orock AE, Nyongbela KD, Babiaka SB, Kukwah A, Ngemen MN. In vitro activity against multi-drug resistant bacteria and cytotoxicityof lichens collected from Mount Cameroon. J King Saud Univ. 2020;32:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL (2006) Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde 2006. Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Manual de Vigilância e Controle da Leishmaniose Visceral. Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos. Brasília, DF

- de Oliveira VNM, dos Santos FG, Ferreira VPG, Araújo HM, do Ó Pessoa C, Nicolete R, de Oliveira RN. Focused microwave irradiation-assisted synthesis of N-cyclohexyl-1, 2, 4-oxadiazole derivatives with antitumor activity. Synth Commun. 2018;48(19):2522–2532. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2018.1509350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Tong J, Wu SC, Yin DK, Yuan XF, Wu JY, Chen J, Shi GG. Modulation of Kupffer cells on hepatic drug metabolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(9):1325–1328. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciscato, C. (2010). Lesão hepática em pacientes com leishmaniose visceral atendidos no hospital universitário da UFMS de 2005 a 2009

- Hariharakrishnan J, Satpute RM, Prasad GBKS, Bhattacharya R. Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity of cyanide in LLC-MK2 cells and its attenuation by alpha-ketoglutarate and N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol Lett. 2009;185(2):132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubatsch I, Ragnarsson EG, Artursson P. Determination of drug permeability and prediction of drug absorption in Caco-2 monolayers. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2111. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaş D, Ari F, Ulukaya E. The MTT viability assay yields strikingly false-positive viabilities although the cells are killed by some plant extracts. Turk J Biol. 2017;41(6):919–925. doi: 10.3906/biy-1703-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology—drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1157–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massolla P, Tomazeli J, Rodrigues S, Sbeghen MR (2018) HEPATITE MEDICAMENTOSA. Seminário de Iniciação Científica e Seminário Integrado de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão

- Michels PA, Avilán L. The NAD+ metabolism of Leishmania, notably the enzyme nicotinamidase involved in NAD+ salvage, offers prospects for development of anti-parasite chemotherapy. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82(1):4–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda MA, Tiossi RFJ, da Silva MR, Rodrigues KC, Kuehn CC, Oliveira LGR, Albuquerque S, McChesney JD, Lezama-Davila CM, Isaac-Marquez AP, Bastos JK. In vitro leishmanicidal and cytotoxic activities of the glycoalkaloids from Solanum lycocarpum (Solanaceae) fruits. Chem Biodivers. 2013;10(4):642–648. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201200063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram JC, Brooks DR, Coombs GH. Roles of cysteine proteinases of trypanosomes and Leishmania in host-parasite interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1(4):455–460. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(98)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves LO, Talhari AC, Gadelha EPN, Silva Júnior RMD, Guerra JADO, Ferreira LCDL, Talhari S. Estudo clínico randomizado comparando antimoniato de meglumina, pentamidina e anfotericina B para o tratamento da leishmaniose cutânea ocasionada por Leishmania guyanensis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(6):1092–1101. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962011000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin MA, Yar MS, Mazumder R, Chakraborthy GS, Ahsan MJ, Rahman MU. Updates on synthesis and biological activities of 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole: a review. Synth Commun. 2017;47(20):1805–1847. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2017.1360911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taha M, Ismail NH, Imran S, Selvaraj M, Jamil W, Ali M, Kashif SM, Rahim F, Khan KM, Adenan MI. Synthesis and molecular modelling studies of phenyl linked oxadiazole-phenylhydrazone hybrids as potent antileishmanial agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;126:1021–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima T, Yokoyama C, Mizuma H, Yamanaka H, Wada Y, Onoe K, Nagata H, Tazawa S, Doi H, Takahashi K, Morita M, Kanai M, Shibasaki M, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y, Onoe H, Watanabe Y. Developmental changes in P-glycoprotein function in the blood–brain barrier of nonhuman primates: PET study with R-11C-verapamil and 11C-oseltamivir. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(6):950–957. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R (2017). Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Research 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ungell ALB. Caco-2 replace or refine? Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(4):423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Anker JN, Schwab M, Kearns GL (2011) Developmental pharmacokinetics. In: Pediatric clinical pharmacology. Springer, Berlin, pp 51–75 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wenzel J, Matter H, Schmidt F. Predictive multitask deep neural network models for ADME-Tox properties: learning from large data sets. J Chem Inf Model. 2019;59(3):1253–1268. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO – World Health Organization (2020) Informações gerais: Leishmaniose. [Internet] [cited 2021 Jun 01]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9417:2014-informacion-general-leishmaniasis&Itemid=40370&lang=en