Abstract

Rob, which serves as a paradigm of the large AraC/XylS family transcription activators, regulates diverse subsets of genes involved in multidrug resistance and stress response. However, the underlying mechanism of how it engages bacterial RNA polymerase and promoter DNA to finely respond to environmental stimuli is still elusive. Here, we present two cryo-EM structures of Rob-dependent transcription activation complex (Rob-TAC) comprising of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (RNAP), Rob-regulated promoter and Rob in alternative conformations. The structures show that a single Rob engages RNAP by interacting with RNAP αCTD and σ70R4, revealing their generally important regulatory roles. Notably, by occluding σ70R4 from binding to -35 element, Rob specifically binds to the conserved Rob binding box through its consensus HTH motifs, and retains DNA bending by aid of the accessory acidic loop. More strikingly, our ligand docking and biochemical analysis demonstrate that the large Rob C-terminal domain (Rob CTD) shares great structural similarity with the global Gyrl-like domains in effector binding and allosteric regulation, and coordinately promotes formation of competent Rob-TAC. Altogether, our structural and biochemical data highlight the detailed molecular mechanism of Rob-dependent transcription activation, and provide favorable evidences for understanding the physiological roles of the other AraC/XylS-family transcription factors.

INTRODUCTION

In order to survive, bacteria have successfully evolved complex transcription initiation mechanisms to timely and finely evoke adaptive responses to a myriad of environmental threats, through transcribing key genes involved in stress responses by RNA polymerase (1–3). In Escherichia coli, RNA polymerase (RNAP) is assembled by a multisubunit RNA polymerase core (α2ββ'ω) and a principal promoter-specific factor σ70 (alternative σ factors will be required under stress conditions) (4). At transcription initiation stage, in combination with RNA polymerase core, σ70 usually makes specific interactions with consensus –35 element (TTGACA) and –10 element (TATAAT) of canonical promoters by σ70 region 4 (σ70R4) and σ70 region 2 (σ70R2), respectively (5–7). Subsequently, the double strands of promoter DNA melt, allowing the RNAP-promoter closed complex (RPc) isomerizes into a stable RNAP-promoter open complex (RPo) which enables transcription initiation without activators (8–12). In contrast, most promoters of bacterial stress response genes do not simultaneously contain the two canonical consensus promoter elements. Thus, transcription activators are required to strengthen the interactions between RNAP and such non-canonical promoters. These interactions remodel promoter DNA, sustain optimal promoter recognition, and finally promote RPc to isomerize into an initiation-competent transcription activation complex (TAC), which is virtually an activator-dependent RPo (13–18).

Rob, originally designated by its binding ability to the right border of the E. coli replication origin oriC (19), is characterized as a representative member of the global AraC/XylS family transcription activators, which regulate expression of diverse subsets of genes involved in multidrug resistance, virulence, and stress response in many clinically important pathogens, such as Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella typhimurium, Yersinia pestis, Pseudomonas putida, Citrobacter rodentium, enteroaggregative E. coli and Shigella spp. (20–23). The common feature of AraC/XylS family transcription activators is the composition of two conserved helix-turn-helix (HTH) motifs that interact with the upstream recognition element A (designated as A site) and the downstream recognition element B (designated as B site) of the highly degenerate corresponding promoters, respectively (20,23). Up to date, a growing number of genetic and biochemical studies have elucidated that Rob is a pleiotropic transcription activator targeting widely distributed Rob regulons. Overexpression of Rob not only causes antibiotics resistance through down-regulating the influx activity, but also leads to adaptive tolerance to organic solvents, superoxide-generating agents and heavy metals, mainly by upregulating the efflux activity to afford increased cellular detoxification (2,24–27).

Though the HTH motif containing Rob N-terminal domain (Rob NTD) shares high sequence and structural similarities with those of the other AraC/XylS family regulators, various studies have proved that Rob also has its own distinct functional and structural characteristics: (i) Unlike SoxS and MarA, which are regulated by certain inducers, Rob is constitutively expressed and maintained at a high level in cell, as can be regulated by itself and other paralogs (19,28). (ii) Rob has a large C-terminal domain (Rob CTD), which was identified as a potential effector binding domain (25,26). Rob CTD also plays physiological roles in the activation of Rob by an effector through a ‘sequestration–dispersal’ mechanism, and in retaining stabilization by protecting Rob from cellular protease degradation by Lon and ClpYQ (29). However, the underlying mechanism of how Rob orchestrates its CTD and NTD to synergistically respond to changing environmental stimuli is still poorly understood. (iii) Comparative analysis of the co-crystal structures of Rob-micF double-stranded DNA (PDB ID: 1D5Y) (30) with MarA-mar double-stranded DNA (PDB ID: 1BL0) (31) shows that Rob displays two major differences in DNA binding from MarA. The second HTH (helix 6) of Rob only binds to the DNA backbone instead of binding to the adjacent DNA major groove as MarA does, and thus orientation of the upstream DNA is unbent while MarA bends DNA with an angle of 35°. Whether this conformation of Rob-micF structure is a functional state is still under dispute. Although previous genetic epistasis experiments and mutational analysis have identified that some key residues of Rob were involved in DNA binding and transcription activation (29,32), the detailed mechanism mediating Rob-dependent transcription activation is still elusive, largely due to the absence of accurate structural information for Rob-dependent transcription activation complex. Furthermore, whether Rob interacts with the C-terminal domain of RNAP alpha subunit (αCTD) and activates transcription of Rob regulons through proposed ‘pre-recruitment’ mechanism for the other AraC/XylS-family transcription factors remain to be elucidated.

In the present study, we determined two functional cryo-EM structures of Rob-dependent transcription activation complex (Rob-TACI and Rob-TACII). The structures trap two alternative conformations of Rob in complex with E. coli RNAP and micF promoter DNA, whose downstream gene is involved in cellular influx of antibiotics, detergents, and toxins. In Rob-TAC, a single Rob molecule engages RNAP by simultaneously interacting with RNAP αCTD and σ70R4, revealing their versatility and important regulatory roles. Notably, by occluding σ70R4 from binding to promoter -35 element, Rob specifically binds to the conserved Rob binding box through its consensus HTH motifs, and retains DNA bending by aid of the accessory acidic loop (residues 187–193) from Rob CTD. More strikingly, our ligand docking and biochemical analysis demonstrate that the large Rob CTD shares great structural similarity with the global Gyrl-like domains in effector binding and allosteric regulation, and it coordinately promotes formation of competent Rob-TAC along with the DNA-binding Rob NTD. Our results systematically define the key interactions that mediate Rob-dependent transcription activation, provide a new mechanistic framework for bacterial transcription regulation, and may support further exploration on the physiological roles of the other AraC/XylS family transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

Plasmid pET28a-rob encoding C-terminal His6 tagged E. coli Rob under the control of T7 promoter was synthesized by Sangon Biotech, Inc. Linear micF_mango DNA fragment corresponding to –85 to +50 of E. coli micF promoter followed by Mango III coding sequence was generated by de novo PCR using primers of micF_mango F1, R1 and R2 (Supplementary Table S1) (16,33–36), purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Inc.), and stored at –80°C. Two strands of micF DNA fragment corresponding to –63 to +20 of micF promoter were synthesized and annealed in a mole ratio of 1:1. Plasmids carrying rob amino acid substitutions were constructed using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Agilent, Inc.). Primers of Rob mutants used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Sequences of micF_mango DNA and micF DNA are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Rob protein purification

E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) was transformed with plasmid pET28a-rob or pET28a-rob derivatives. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin, and cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking until OD600 reached 0.6. Protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG to 0.5 mM, and cultures were incubated 14 h at 20°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (5422 g; 10 min at 4°C), resuspended in 20 ml buffer A (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 5% glycerol), and lysed using a high-pressure homogenizer NanoGenizer (Genizer LLC, Irvine, CA, USA). The lysate was centrifuged (13000 g; 40 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 3 ml Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was subsequently washed with 30 ml buffer A containing 0.04 M imidazole and eluted with 15 ml buffer A containing 0.2 M imidazole. The eluate was loaded onto a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 75 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2), and the column was eluted with 120 ml of the same buffer. Fractions containing E. coli Rob were pooled and stored at –80°C. E. coli Rob derivatives were expressed and purified using the same procedure as the wild type protein. The yields were 4 mg/l, and the purities were > 95%.

E. coli RNAP purification

E. coli RNAP was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmids of pGEMD (37) and pIA900 (38). Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 50 ml LB broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and cultures were incubated 16 h at 37°C with shaking. Aliquots (10 ml) were used to inoculate 1 L LB broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin, cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking until OD600 = 0.6, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated 15 h at 20°C. Then cells were harvested by centrifugation (5000 g; 15 min at 4°C), resuspended in 20 ml lysis buffer C (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 0.2 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol and 5 mM DTT) and lysed using a high-pressure homogenizer NanoGenizer (Genizer LLC, Irvine, CA, USA). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (13 000 g; 30 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was precipitated by 0.7% (g/ml) Polymin P (pH 7.9), incubated for 10 min at 4°C with stirring, followed by centrifugation (8000 g; 15 min at 4°C). The precipitate was washed with buffer D (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9 and 5% glycerol) containing 0.5 M NaCl, followed by centrifugation (8000 g; 15 min at 4°C). Protein was extracted with buffer D containing 1 M NaCl, followed by centrifugation (8000 g; 20 min at 4°C). Then the extract is precipitated by addition of 30 g ammonium sulfate, incubated for 30 min at 4°C with stirring, followed by centrifugation (13 000 g; 30 min at 4°C). Subsequently, the pellet was resuspended in buffer D containing 0.5 M NaCl, and loaded onto a 5 ml column of Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Inc.) pre-equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with 25 ml buffer D containing 20 mM imidazole and eluted with 25 ml buffer D containing 0.15 M imidazole. The eluate was diluted in buffer E (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT) and loaded onto a Mono Q 10/100 GL column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer E and eluted with a 160 ml linear gradient of 0.3-0.5 M NaCl in buffer E. Fractions containing E. coli RNAP were pooled and applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer B, and the column was eluted with 120 ml of the same buffer. Fractions containing E. coli RNAP were pooled and stored at -80°C. Yield was 2.5 mg/l, and purity was >95%.

Assembly of E. coli Rob-TAC

DNA oligonucleotides micF scaffold (sequence is shown in Figure 1A) were synthesized (Sangon Biotech, Inc.) and dissolved in nuclease-free water to 1 mM. Template strand DNA and nontemplate strand DNA were annealed at 1:1 ratio in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 0.2 M NaCl. Then, E. coli Rob-TAC was assembled by incubating E. coli RNAP, micF scaffold, and E. coli Rob in a molar ratio of 1: 1.1: 10 at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, the mixture was applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in buffer B. After identification by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), the fractions containing E. coli Rob-TAC were concentrated to 18.7 mg/ml using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (10 kDa MWCO, Merck Millipore, Inc.).

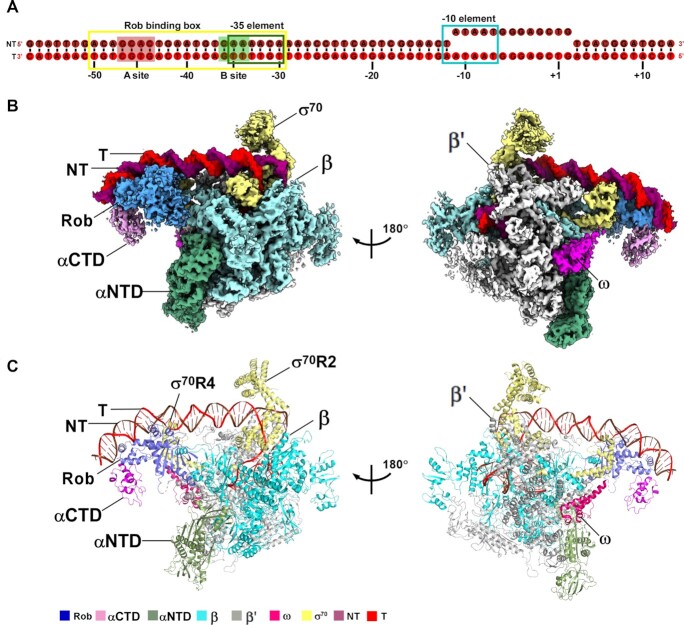

Figure 1.

The overall structure of E. coli Rob-TAC. (A) DNA scaffold used in structure determination of E. coli Rob-TACII. (B, C) Two views of the cryo-EM density map (B) and structure model (C) of E. coli Rob-TACII. The EM density maps and cartoon representations of Rob-TACII are colored as indicated in the color key. NT, non-template-strand promoter DNA; T, template-strand promoter DNA.

Cryo-EM grid preparation

Immediately before freezing, 6 mM CHAPSO was added to the freshly purified E. coli Rob-TAC. C-flat grids (CF-1.2/1.3-4C; Protochips, Inc.) were glow-discharged for 60 s at 15 mA (PELCO/Easiglow apparatus) or with a cleaning time for 120 s (Gatan/SOLARUS 950 plasma cleaning system) prior to the application of 3 μl of E. coli Rob-TAC complex, then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (FEI, Inc.) with 95% chamber humidity at 10°C.

Cryo-EM data acquisition and processing

The grids with E. coli Rob-TAC were imaged using a 300 kV Titan Krios (FEI, Inc.). Images were recorded with Serial EM (39) in counting mode with a physical pixel size of 1.100 Å or 1.307 Å and a defocus range of 1.4–2.2 μm. Data were collected with a dose of 10 e/pixel/s. Images were recorded with a 10 s exposure and 0.25 s subframes. Subframes were aligned and summed using MotionCor2 (40). The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using CTFFIND4 (41). From the summed images, ∼10 000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION (42). 2D averages of the best classes were used as templates for auto-picking in RELION. Auto-picked particles were manually inspected, then subjected to 2D classification in RELION. Poorly populated classes were removed, resulting in a dataset of 791 759 particles from 4,372 movies for E. coli Rob-TACI or a dataset of 417 732 particles from 2099 movies for E. coli Rob-TACII. These particles were 3D-classified in RELION using a map of E. coli RPo (PDB ID: 6CA0) (10) low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution as a reference. For E. coli Rob-TACI, 3D classification resulted in 4 classes. Particles in Classes 2 and 3 were combined and further performed 3D classification focused in the region of Rob. After focused 3D classification, particles in Classes 2, 3, 4 were combined and processed by CTF refinement, Bayesian polishing and 3D auto-refined, and the best-resolved 386,188 particles was post-processed in RELION. The Gold-standard Fourier-shell-correlation analysis indicated a mean map resolution of 4.06 Å of E. coli Rob-TACI (Supplementary Figure S3 and S5). Likewise, For E. coli Rob-TACII, 3D classification resulted in 3 classes. Particles in Class 3 were processed by CTF refinement, Bayesian polishing, 3D auto-refinement, the best-resolved 335,021 particles were post-processed in RELION. And the Gold-standard Fourier-shell-correlation analysis indicated a mean map resolution of 4.57 Å of E. coli Rob-TACII (Supplementary Figure S4 and S6).

Cryo-EM model building and refinement

The model of E. coli RNAP RPo (PDB ID: 6CA0) (10), the crystal structure of Rob in complex with E. coli micF DNA (PDB ID: 1D5Y) (30), and the ternary structure of E. coli MarA, DNA and RNAP αCTD (PDB ID: 1XS9) (43) were manually fitted into the cryo-EM density maps in Coot (44), followed by adjustment of main- and side-chain conformations in Coot and real-space refinement using Phenix (45). The coordinates were real-space refined with secondary structure restraints in Phenix.

In vitro transcription assay

In vitro Mango-based transcription assays were carried out by incubating E. coli RNAP, micF-mango scaffold, with or without E. coli Rob or its derivatives. Transcription assay was performed in a 96-well microplate format. Reaction mixtures (80 μl) contained: 0 or 4 μM Rob or Rob derivatives, 0.1 μM E. coli RNAP, 50 nM micF-mango scaffold, 1 μM TO1-Biotin, 0.1 mM NTP mix (ATP, UTP, GTP and CTP), with or without ligand (100 μM chenodeoxycholic acid or 5 mM 2, 2’-bipyridine), 40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol. First, E. coli RNAP, Rob and micF-mango scaffold were incubated for 15 min at 37°C, then mixtures were supplemented with 0.030 mg/ml heparin and incubated for 2 min at 22°C, then NTP mix and TO1-biotin were added into the mixture and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Finally, fluorescence emission intensities were measured using a multimode plate reader (EnVision, PerkinElmer Inc.; excitation wavelength = 510 nm; emission wavelength = 535 nm). Relative transcription activities of Rob derivatives were calculated using:

|

(1) |

where IWT and I are the fluorescence intensities in the presence of Rob and Rob derivatives; I0 is the fluorescence intensity in the absence of Rob.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

To further clarify whether Rob derivatives affect the formation of Rob-TAC or not, we also carried out electrophoretic mobility shift assays in reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing:1 μM Rob or Rob derivatives, 50 nM E. coli RNAP, 15 nM micF DNA in EMSA buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol). E. coli RNAP was firstly incubated with micF DNA for 10 min at 37°C, then incubated with Rob or Rob derivatives for 20 min at 37°C. Reaction mixtures were supplemented with 0.050 mg/ml heparin and incubated for 2 min at 22°C. The reaction mixtures were finally applied to 5% polyacrylamide slab gels (29:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide), electrophoresed in 90 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.0, and 0.2 mM EDTA, and stained with 4S Red Plus Nucleic Acid Stain (Sangon Biotech, Inc.) according to the procedure of the manufacturer, and analyzed by ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) of E. coli Rob and RNAP were performed in reaction mixtures (20 μl) containing: 1 μM Rob or Rob derivatives, 2 μM E. coli RNAP, 15 nM micF DNA in EMSA buffer. Rob was incubated with E. coli RNAP for 10 min at 25°C and then incubated with (or without) DNA scaffold for 15 min at 25°C. Reaction mixtures were supplemented with 0.050 mg/ml heparin and incubated 2 min at 22°C. The reaction mixtures were applied to 5% polyacrylamide slab gels (29:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide), electrophoresed in 90 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.0, and 0.2 mM EDTA, and stained with 4S Red Plus Nucleic Acid Stain (Sangon Biotech, Inc.) or coomassie brilliant blue staining solution (Sangon Biotech, Inc.) according to the procedure of the manufacturer.

Molecular Docking analysis and the burying surface area measurement

All molecular docking studies were performed using Autodock4.2 package (46). Briefly, Rob from the cryo-EM structure of Rob-TACII was docked with its potential ligands (chenodeoxycholic acid, 2,2’-bipyridine, sodium decanoate and 4,4’-bipyridine). The molecule was added with non-polar hydrogens and assigned partial atomic charges using AutoDockTools (ADT) (46). The coordinates of potential ligands in Rob structure were generated based on the coordinates of rhodamine 6G (R6G) from the crystal structure of the Gyrl-like family protein SAV2435 (PDB ID: 5KAW) (53) in combination with CORINA Classic online service. A grid box with 40 × 40 × 40 grid points and 0.2 Å grid spacing centered roughly at the potential ligand binding position was used as the searching space. 100 runs of Larmarckian Genetic Algorithm were performed to search the protein-ligand interactions. The results were clustered and ranked. Result analyses and figure rendering were performed using PyMOL.

To measure the potential burying surface areas in the Rob-TACI or Rob-TACII, we used the online web server (http://sts.bioe.uic.edu/castp) and followed the descriptions as illustrated before (54).

Data analysis

Data for in vitro transcription assays or EMSA are means of three technical replicates. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (***) or (**) indicates highly significant (P value < 0.001) or significant (P value < 0.01) difference from the wild-type Rob analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, respectively.

RESULTS

Overall structure of Rob-TAC

In order to obtain the structure of Rob-TAC, we used a nucleic-acid scaffold corresponding to positions –57 to +13 of micF promoter (positions numbered relative to the transcription start site; Figure 1A). MicF encodes an antisense RNA involved in multidrug resistance by repressing expression of the major membrane porin, OmpF (47,48). The micF DNA scaffold is composed of a 20 bp Rob binding box robbox (including recognition element A site with sequence of GCAC and recognition element B site with sequence of CAAA which overlaps with the –35 element), and a 13 bp non-complementary transcription bubble (–11 to +2) with a consensus –10 element, which was positioned at the catalytic center of RNAP for stabilizing core RNAP and allowing RNA synthesis (Figure 1A) (12,16,18,49). Meanwhile, our in vitro Mango-based transcription assay showed that, in the presence of Rob, E. coli RNAP efficiently activated transcription of micF-mango promoter, reflecting that these purified proteins are biologically relevant (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). By combing E. coli RNAP, Rob and micF DNA scaffold, we successfully assembled Rob-TAC complex in a stoichiometric manner as evidenced from SDS-PAGE and native PAGE analyses (Supplementary Figure S2A, C and D).

The frozen Rob-TAC complex was subsequently analyzed on a Titan Krios cryo-EM, and the data was sequentially processed, modelled and refined. Fortunately, we finally trapped two structures of Rob-TAC, namely Rob-TACI and Rob-TACII, at nominal resolutions of 4.06 and 4.57 Å, respectively (Figure 1B and C; Supplementary Figures S3–S7; Table 1). Local resolution calculation exhibits two central core RNAP at 3.5–4.5 Å and peripheral RNAP αCTD and Rob at 5.5–7.0 Å (Supplementary Figure S5C and 6C). There is only one Rob molecule present in each complex, simultaneously engaging RNAP αCTD, RNAP σ70R4 and robbox of promoter DNA, as is different from the reported dimeric transcription activators (13,14). Though the two structures superimpose onto each other well at the densities of E. coli RNAP core enzyme, promoter DNA, and Rob NTD, the obvious extra density of Rob CTD in Rob-TACI exhibits significant differences from that of Rob-TACII, with a rotation of ∼35° (Supplementary Figures S7D). In Rob-TACI, Rob CTD retains in close proximity to RNAP αCTD and helix 1 from Rob NTD, possibly plays a potential role in RNAP recruitment and facilitates DNA binding (Supplementary Figures S7B and C). While in Rob-TACII, Rob CTD moves away from RNAP αCTD and helix 1 of Rob NTD, mainly interacts with the C-terminal portion of Rob NTD and the long linker connecting Rob NTD and Rob CTD, rendering the acidic loop of Rob CTD close to the downstream promoter (Figure 1A and B). Since the density and occupancy of Rob CTD in Rob-TACI seem to be significantly weaker and lower than that in Rob-TACII, we infer that the non-stable Rob-TACI is most probably a pre-state of the stable Rob-TACII. Therefore, we choose Rob-TACII to be described in the following section.

Table 1.

Single particle cryo-EM data collection, processing, and model building for E. coli Rob-TACII, Rob-TACI

| Rob-TACII | Rob-TACI | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | ||

| Microscope | Titan Krios | Titan Krios |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | 300 |

| Detector | K2 summit | K3 summit |

| Electron exposure (e/Å2) | 50 | 50 |

| Defocus range (μm) | 1.4–2.2 | 1.4–2.2 |

| Data collection mode | Count | Super resolution |

| Physical pixel size (Å/pixel) | 1.307 | 1.100 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 | C1 |

| Initial particle images | 478 388 | 962 734 |

| Final particle images | 335 021 | 386 188 |

| Map resolution (Å)a | 4.57 | 4.06 |

| Refinement | ||

| Map sharpening B-factor (Å) | –89 | –101 |

| Root-mean-square deviation | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 |

| Bond angle (º) | 0.904 | 0.993 |

| MolProbity statistics | ||

| Clashscore | 12.00 | 10.00 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| Cβ outliers (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 91.84 | 91.38 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.20 | 0.20 |

aGold-standard FSC 0.143 cutoff criteria.

Comparative structural analysis shows that E. coli RNAP containing σ70 in Rob-TAC structures maintains in a similar conformation to that of E. coli RNAP-promoter open complex (PDB ID: 6CA0) (10) with root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.410 Å (3144 Cαs aligned) and 1.492 Å (3237 Cαs aligned) in Rob-TACI and Rob-TACII, respectively. By aid of β′ coiled coil, σ70R2 contacts the consensus –10 element. RNAP accommodates the transcription bubble and downstream dsDNA in the same way as those in RPo (10) (Supplementary Figures S8 and S9). One distinguishing feature of Rob-TACII is that Rob occludes σ70R4 from binding to the -35 element and specifically binds robbox. Furthermore, the co-crystal structure of Rob complexed with micF double stranded DNA could be well fitted into the upstream promoter density map, except for the obvious DNA bending towards Rob CTD (Supplementary Figure S7E), especially the acidic loop of Rob. Such DNA conformational change shares some similarities with that of MarA-mar binary complex (PDB ID: 1BL0) (31) (Figure 1B and C; Supplementary Figure S7B and C).

RNAP αCTD is required for Rob-dependent transcription activation of class II promoters

Distinct from previous in vitro transcription assay that inferred RNAP αCTD was not required for transcription activation of class II promoters (50), in Rob-TACII, there exists abundant interactions between Rob NTD and RNAP αCTD, burying a surface area of 149.39 Å2 (Figure 2A-B). Evidently, residues Q3, G5, D9 and W13 from helix α1 of Rob form hydrogen bonds with residues P293 and N294 in the N-terminal loop of helix α1, and helix α4 of RNAP αCTD, respectively. Residues G5 and G32 of Rob form van der Waals contacts with residues V264 and L295 of RNAP αCTD (Figure 2C). Moreover, residue Y33 in the loop connecting helix α2 and α3 of Rob generates hydrogen bonds with residues from the DNA binding ‘265 determinant’ (R265 and K298) of RNAP αCTD (Figure 2C), indicative of DNA binding deficiency of RNAP αCTD targeting at promoter UP elements (AT-rich DNA regions locate approximately from –40 to –60 of a promoter) (51). Consistent with this, mutation of the key residues of Rob-RNAP αCTD interaction led to obvious decrease in both transcription activation activities by Mango-based transcription assay and Rob-TAC formation activities evidenced by EMSA (Figure 2D, Supplementary Figure S10A and B), suggesting the necessity of these residues to Rob-dependent transcription activation.

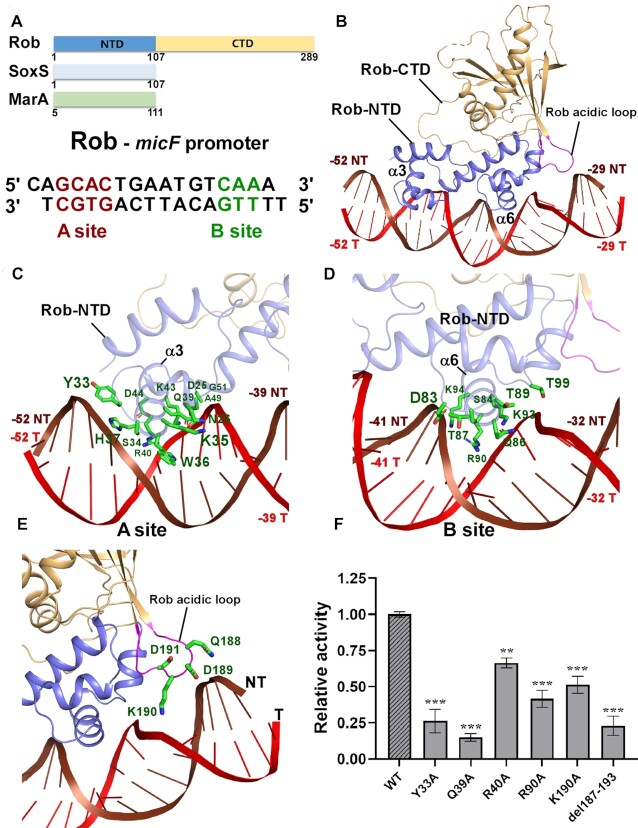

Figure 2.

The interactions between Rob and RNAP αCTD. (A) Relative locations of Rob, E. coli RNAP αCTD, and the upstream double-stranded DNA. (B) Rob interacts with E. coli RNAP αCTD. (C) Detailed interactions between E. coli RNAP αCTD and Rob. Salt-bridges are shown as red dashed lines. (D) Substitutions of Rob residues involved in interactions with E. coli RNAP αCTD decreased in vitro transcription activity. Data for in vitro transcription assays are means of three technical replicates. Error bars represent ± SEM of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (***) indicates highly significant (P value < 0.001) difference from the wild-type Rob analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, respectively. (E) Interface between E. coli MarA and RNAP αCTD (PDB ID: 1XS9). (F) Interface between T. thermophilus TAP (transcription activator protein TTHB099) and T. thermophilus RNAP αCTD (PDB ID: 5I2D).

In comparison, structural analysis shows that interactions between Rob and RNAP αCTD in Rob-TACII are similar to those between MarA and RNAP αCTD (MarA-RNAP αCTD, PDB ID: 1XS9) (43) (with DNA omitted for clarity, Figure 2E) as well as between the class II transcription activator protein TAP (T. thermophilus TTHB099) and RNAP αCTD from TAP-dependent transcription activation complex (TAP-TAC, PDB ID: 5I2D, Figure 2F) (13), with buried surface areas being 123.81 Å2 and 182.54 Å2, respectively. In Rob-TACII and MarA-RNAP αCTD complexes, each activator uniquely contacts the DNA binding ‘265 determinant’ of RNAP αCTD by the homologous helices and loops. Likewise, in TAP-TAC, activating region 4 (AR4) of one TAP monomer interacts with a cluster of residues in the N-terminus of helix α4, the loop connecting helix α3 and α4, and ‘265 determinant’ of RNAP αCTD (Figure 2F). These implies the important regulatory role of the ‘265 determinant’ of RNAP αCTD.

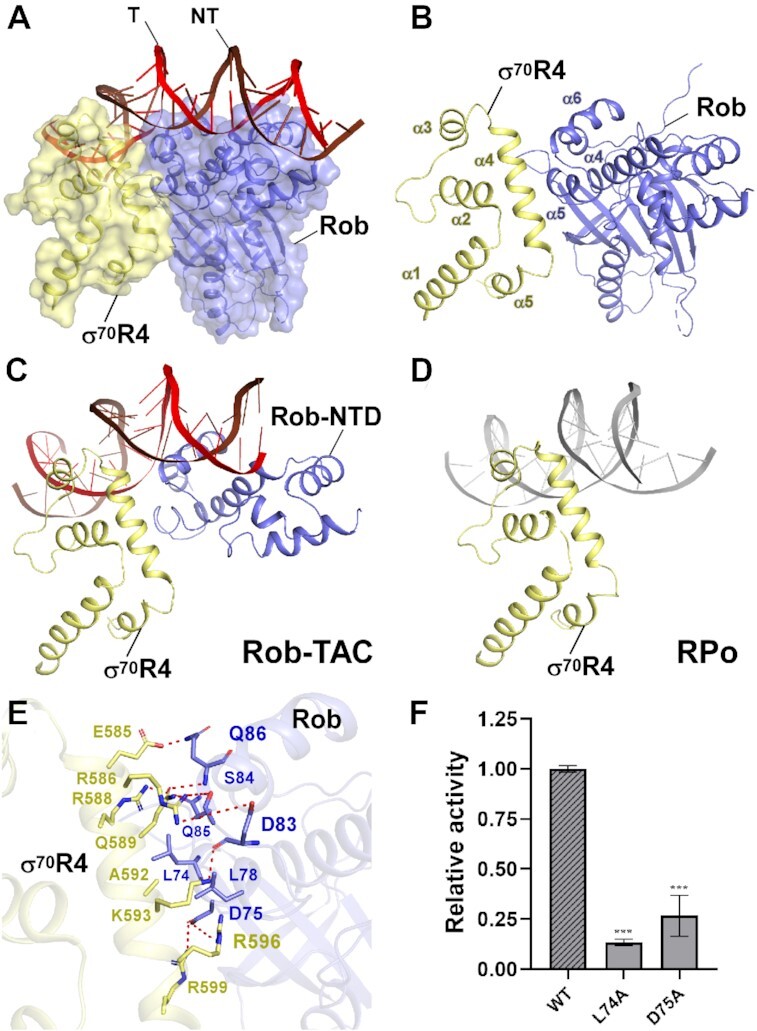

Rob occludes σ70R4 from binding to promoter -35 element and synergistically redirects RNAP to Rob regulons

Despite the critical interactions between σ70R2 and promoter consensus –10 element, interactions between σ70R4 and promoter consensus –35 element have also been extensively proved to be essential for RPo formation and transcription activation (3,5,10,12). While in case of class II promoters that contain activator binding box overlapping with –35 element to some extent, σ70R4 remodeling is required to maintain successful transcription initiation. As expected, in Rob-TACII, Rob forms several types of interactions with the long helix α5 of σ70R4, with a buried surface area of 40.46 Å2 (Figure 3A–C). Thus, helix α5 and the adjacent loop of Rob in Rob-TACII occlude σ70R4 from binding to –35 element, rendering it makes weaker interactions with DNA (Figure 3C and D). Residues S84, Q85, Q86 in the loop connecting helix α5 and α6 of Rob form three hydrogen bonds with residues Q589, R588 and E585 in σ70R4, respectively. Residues D75 and D83 of Rob simultaneously make ionic bonds with residues R596, R599, K593 and R586 from σ70R4. Furthermore, residues of L74 and L78 from Rob form van der Waals contacts with the hydrophobic residue A592 from σ70R4. In accordance with the above interactions (Figure 3E), our transcription and EMSA analyses of mutants also showed that the key residues are functionally relevant (Figure 3F; Supplementary Figure S10B). This observation is consistent with the previous genetic and biochemical experiments which suggested that Rob possibly occludes σ70R4 from binding to promoter -35-hexamer and synergistically redirect RNAP to specific robbox-containing promoters (32).

Figure 3.

The interactions between Rob and σ70R4. (A) Relative locations of Rob, σ70R4, and upstream double-stranded DNA in E. coli Rob-TAC. (B) Rob interacts with the σ70R4. σ70R4 and Rob are represented as yellow or blue cartoon, respectively. (C) Relative locations of Rob-NTD, E. coli RNAP σ70R4 and the upstream double-stranded DNA. (D) Relative locations of E. coli RNAP σ70R4 and the upstream typical –35 element DNA (PDB ID: 6CA0). (E) Detailed interactions between σ70R4 and Rob. Hydrogen bonds are shown as red dashed lines. (F) Substitutions of the residues involved in Rob-σ70 interactions reduced in vitro transcription activity. Data for in vitro transcription assays are means of three technical replicates. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (***) indicates highly significant (P value < 0.001) difference from the wild-type Rob analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, respectively.

Rob specifically interacts with two DNA major grooves of robbox and the acidic loop facilitates such interaction

As a representative example of the AraC/XylS family transcription activators, Rob harbors two highly conserved DNA-binding HTH motifs (designated as HTHA and HTHB, respectively) in Rob NTD (Figure 4A). Unlike MarA, which can insert its two conserved HTH motifs into the corresponding DNA major grooves of mar promoter and bends DNA by 35°, the co-crystal structure of Rob–micF showed that Rob could only insert helix α3 of HTHA into the A site of robbox, with helix α6 of HTHB contacting the phosphate backbone of B site, and thus rendering promoter DNA unbent (Supplementary Figures S11A) (30). However, some other in vivo and in vitro assays on Rob held different opinions (32,52) and it needs to be further clarified. Surprisingly, both helix α3 of HTHA and helix α6 of HTHB in Rob-TACII insert into the DNA major grooves of robbox and make the DNA bent with an orientation similar to that of MarA (Figure 4A–D; Supplementary Figures S11B), revealing a general promoter remodeling mode for the AraC/XylS family transcription activators. By using helix α3 of HTHA and helix α6 of HTHB, Rob makes abundant interactions with the corresponding DNA major grooves of robbox (Figure 4C and D; Supplementary Figures S11C). As to the A site of robbox, residues W36 and S34 of Rob form hydrogen bonds with –45A and -47G of the non-template strand DNA, respectively. Residues Y33, H37 of Rob make contacts with the DNA phosphate backbone of the non-template strand DNA. Both of residues Q39 and R40 form two hydrogen bonds with the template strand DNA, indicating their critical roles in stabilizing DNA. Besides, several residues (D25, N26, K35, K43, D44, A49, G51) from helix α3 and the adjacent loops interacts with the DNA phosphate backbone of the template strand DNA. In respect to the B site of robbox, residues Q86 and R90 of Rob insert into the major groove and specifically recognize bases of –34T, –35T from the template strand DNA, and –37T, –38G from the non-template strand DNA (Figure 4D). In addition, residues of R55, D83, S84, T87, K94 make extensive contacts with the non-template strand DNA, while residues of Q86, K93, T89, T99 contact template strand DNA. Another striking feature of Rob-TACII is that the acidic loop of Rob (spanning from S187 to E193) moves in close proximity to the bent micF promoter DNA. Structural analysis shows that residue K190 makes obvious ionic bonds with the DNA phosphate backbone of –31G and -32T from the template strand DNA (Figure 4E). In good agreement with these observations, substitutions of the above key residues involved in Rob-DNA interactions (Y33A, Q39A and R90A) and acidic loop (K190A, del187-193) confer significant defects in transcription activation activities verified by our Mango-based transcription assay (Figure 4F) and Rob-TAC formation activities (Supplementary Figure S10A and B), suggesting the importance of their functions. This is in accordance with the recently reported molecular dynamics simulation experiment which proposed that the acidic loop of Rob might facilitate interconversion between the distinct DNA binding modes observed in MarA and Rob (52). These evidences reveal the necessity and accessory role of the acidic loop for Rob-dependent transcription activation.

Figure 4.

The interactions between Rob and the micF promoter DNA. (A) Domain architecture of Rob, SoxS and MarA (top panel); the sequences of the micF promoter for Rob protein with the A- and B-box sequences highlighted in red and green, respectively (bottom panel). (B) Rob in complex with the micF promoter DNA. Rob-NTD and Rob-CTD are represented as blue or orange cartoon, respectively. (C, D) Detailed interactions between Rob and the micF promoter DNA. Residues from Rob involved in interacting with A- or B-site sequences of micF promoter DNA are shown in green sticks. (E) Zoom-in view of the interactions between the acid loop and the micF promoter DNA. The acidic loop (residues 187-193) connecting strands β3 and β4 in the extra C-terminal domain of the Rob protein is highlighted in magenta. Residues from the acidic loop that contact DNA are shown in green sticks. (F) Substitutions of residues involved in Rob-DNA interactions suppressed in vitro transcription activity. Data for in vitro transcription assays are means of three technical replicates. Error bars represent ± SEM of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (***) or (**) indicates highly significant (P value < 0.001) or significant (P value < 0.01) difference from the wild-type Rob analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, respectively.

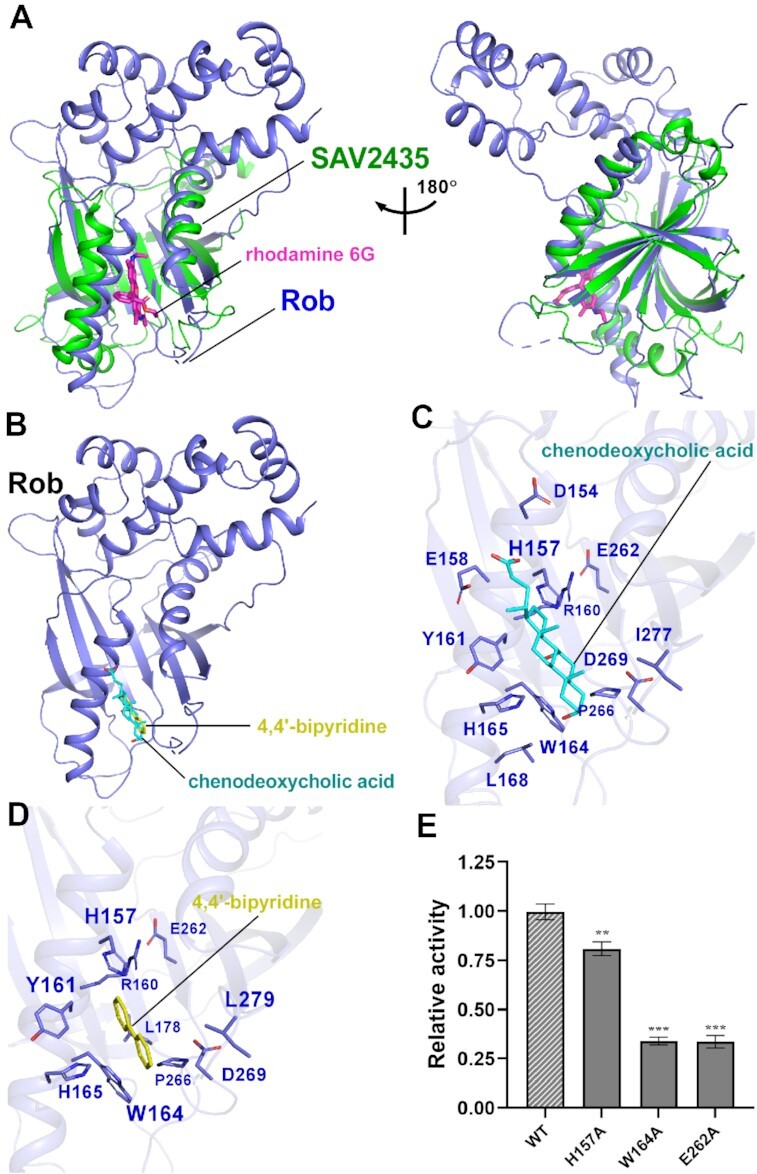

Rob CTD activates transcription through allosteric coordination with Rob NTD

Rob CTD is the most obvious feature that distinguish itself from the other subfamily AraC/XylS factors, and has been evidenced to be crucial for stability and activation activity of Rob (29). In vivo analysis inferred that Rob CTD possibly stabilizes Rob by protecting its vulnerable DNA-binding NTD from proteolytic degradation by ClpYQ and Lon proteases (32). Consistent with this, Rob CTD in our Rob-TAC structures forms ‘ridge-like’ projection sitting atop the N-terminal surface of Rob NTD in Rob-TACI (Supplementary Figure S7B and C) or embracing the C-terminal surface of Rob NTD in Rob-TACII (Figure 1B and C). This equilibrium enables Rob NTD well protected by Rob CTD and promoter DNA.

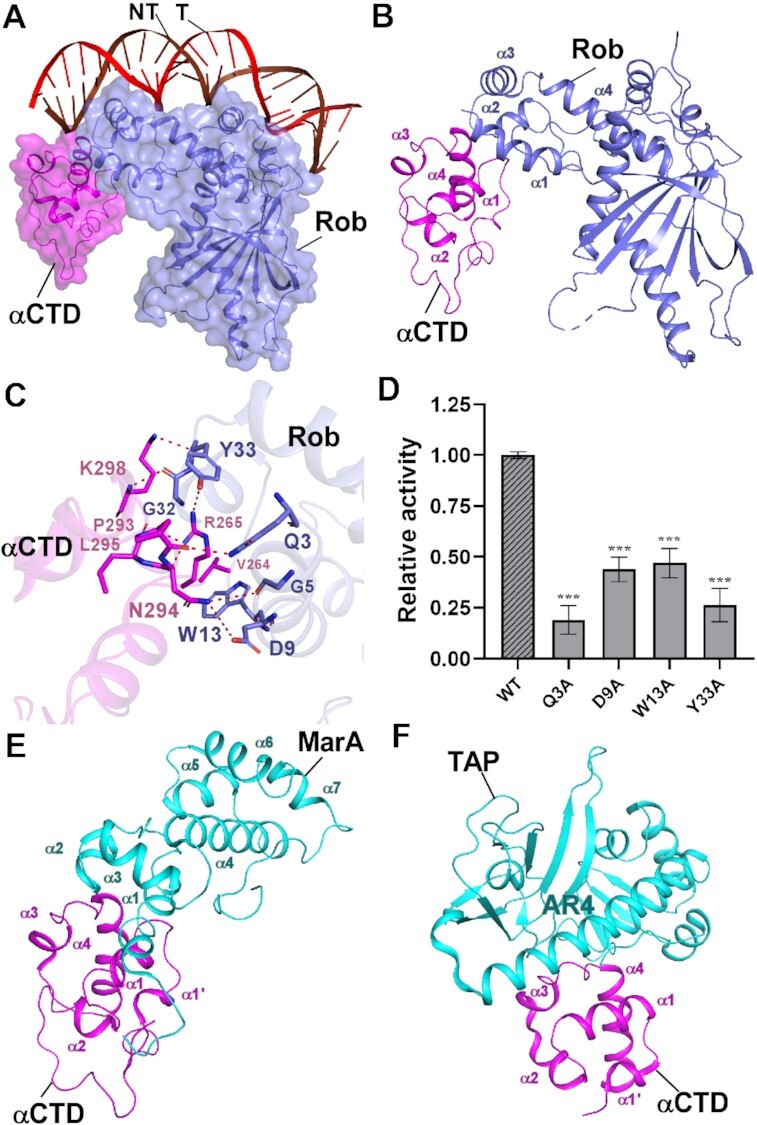

In E. coli, Rob is postulated as a global regulator of multidrug resistance. This is mainly attributed to the distinct Rob CTD which forms a global GyrI-like domain capable of binding small molecules (25,26,53). However, the detailed molecular mechanism is poorly determined. To gain insight into the ligand binding properties and the evoked conformation changes of Rob, we compared Rob from Rob-TACII with other GyrI-like domains in complex with ligands from other transcription factors involved in bacterial stress response (18,53,55). Intriguingly, comparative structural analysis shows that Rob CTD superimposes well with the evolutionarily conserved GyrI-like domain family regulators, such as Staphylococcus aureus SAV2435 (PDB ID: 5KAW) with an RMSD of 2.21 Å (133 Cα aligned) (Figure 5A) (53). These GyrI-like domains are mainly composed of antiparallel β-strands, connecting loops and long characteristic helices, and have been proved to be adaptive for broad selectivity of ligand binding and biological signaling. These ligand binding pockets exhibit similar stereochemical properties and some connecting loops were also verified to play regulatory roles in the allosteric regulation process. Consistent with the above points, our molecular docking analysis of Rob with rhodamine 6G (R6G) and other four potential ligands (chenodeoxycholic acid, 4,4′-bipyridine, sodium decanoate and 2,2′-bipyridine) exhibits well fitted ligand binding pockets (Figure 5A–C; Supplementary Figure S12), indicating similar allosteric regulation mode. In accordance with the well-defined nature of ligand binding pockets, all the four potential ligands are mainly surrounded by cluster of aromatic and heterocyclic amino acids (Figure 5C and D; Supplementary Figure S12B and D), and mutation of the involved conserved residues largely compromises Rob-dependent transcription activity and Rob-TAC formation, especially Rob W164A and E262A (Figure 5E; Supplementary Figure S12E and F; Supplementary Figure S10E). This implies their biological significance in maintaining stereochemical conformation of Rob CTD and activating Rob-dependent transcription activity. As allosteric regulation model has been proposed for GyrI-like domain containing factors upon effector binding, it is therefore tempting to speculate that Rob may allosterically activate transcription through synergistical coordination with its effector sensor CTD and effector responder NTD.

Figure 5.

Molecular docking analysis of Rob with potential ligands. (A) Structural superimposition of the Gyrl-like family protein SAV2435 (PDB ID: 5KAW) onto the Rob from Rob-TAC. Rob and the SAV2435 are shown as blue and green cartoon. The ligand rhodamine 6G(R6G) is shown in magenta stick. (B) Rob docked with chenodeoxycholic acid and 4,4′-bipyridine. (C) Predicted binding pockets for chenodeoxycholic acid on Rob protein. Residues potentially interacted with chenodeoxycholic acid are shown in blue sticks. (D) Predicted binding pockets for 4,4’-bipyridine on Rob protein. Residues potentially interacted with 4,4’-bipyridine are shown in blue sticks. (E) Substitutions of conserved residues involved in Rob-ligand interactions suppressed in vitro transcription activity in the presence of 100 μM chenodeoxycholic acid. Data for in vitro transcription assays are means of three technical replicates. Error bars represent ± SEM of n = 3 experiments. Asterisk (***) indicates highly significant (P value < 0.001) difference from the wild-type Rob analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test, respectively.

DISCUSSION

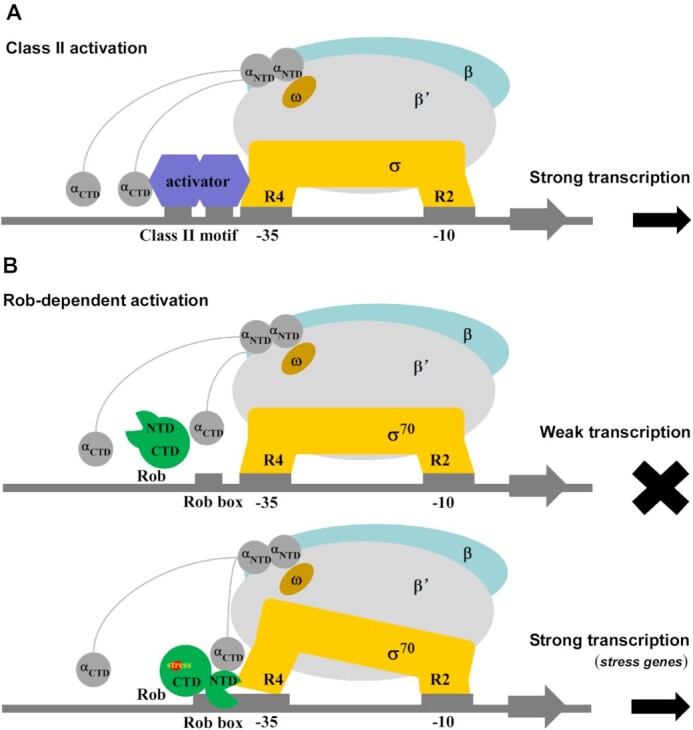

Bacteria has established diverse transcription regulation strategies to respond to a variety of environmental stresses and transcription activation is a well-known strategy. Though both in vivo and in vitro experiments have elucidated that the AraC/XylS family transcription activators play fundamental roles in multidrug resistance, metabolism of carbohydrate, heavy metals sensing, and virulence (20,22,23), long-standing questions regarding to their molecular mechanism still remain. Based on our structural and biochemical analysis of Rob-TAC, several key features of Rob as a member of AraC/XylS subfamily transcription activators can be delineated: (i) Rob acts as a monomer in Rob-TAC. This is different from the reported class II transcription activators, which usually function in the dimer form (Figure 6A) (13,15,18,56). (ii) Rob remodels RNAP by specific Rob-RNAP αCTD interactions and Rob-σ70R4 interactions. These interactions synergistically redirect RNAP to target at specific Rob regulons. Similar to SoxS, MarA and TAP, Rob interacts with the DNA binding ‘265 determinant’ of RNAP αCTD, disrupts potential interactions between RNAP αCTD and UP elements, and stabilizes the transcription activation complex. This is also in agreement with the mutational analysis that different determinants of RNAP αCTD are required for CRP-dependent transcription activation (13,43,56,57). The Rob-σ70R4 interactions occlude σ70R4 from binding to canonical promoter elements, make it acting as a co-sigma factor. This also resembles the efficient σ appropriation mechanism mediated by MotA and AsiA (49). Sequence alignment of Rob and its homologs (MarA, SoxS, TetD and RamA) shows that the key residues (D9, W13, Y33 and D75) of Rob involved in the above interfaces are highly conserved (Supplementary Figure S13), implying similar significant protein-protein interactions for the AraC/XylS-family transcription factors to remodel RNAP. (iii) Rob remodels promoter DNA not only by its two conserved HTH motifs, but also by aid of the acidic loop, which possibly facilitates DNA bending and promotes formation and stability of Rob-TAC. (iv) The global Gyrl-like domain containing Rob CTD serves as an environmental stimuli sensor, which structurally stabilizes and activates transcription through allosteric coordination with the stress responder Rob NTD.

Figure 6.

Proposed models for class-II-activator-dependent and Rob-dependent transcription activation. (A) Proposed working model for class-II-activator-dependent transcription activation. (B) Proposed working model for Rob-dependent transcription activation. Rob shows weak transcription activation activity in the absence of Rob-RNAP interactions, and activates the transcription of most genes with the promoter containing Rob binding box under stress.

It is worthwhile to mention several observations during our experiments. (i) Rob protein we purified exhibits obvious transcription activity; (ii) Rob CTD deletion mutant (residues 1–133) was mostly expressed as inclusion bodies and reduced greatly in solubility; (iii) The two alternative conformations of Rob-TAC we obtained show active ‘dispersal’ state, which may include an effector molecule during expression and purification. In agreement with this, the effectors play an insignificant role in enhancing transcription activities and Rob-TAC formation (Supplementary Figure S12E, S10A, B and E), and mutation of the potential ligand binding residues of Rob CTD apparently cause defects on transcription activities (Figure 5E; Supplementary Figure S12F). These data demonstrate that Rob CTD is essential for the stability and activity of Rob, and ligand is required for Rob-dependent transcription activity through binding to Rob CTD. Consistent with previous in vitro results, this also provides favorable evidence for the ‘sequestration-dispersal’ mechanism of Rob in vivo, which proposes Rob CTD as a novel off-on switch for the regulation of Rob's activation activity upon ligand binding (25,26,29,47). Thus, it is probably that in the ‘sequestration’ state, the residues involved in Rob-RNAP αCTD and Rob-σ70R4 interfaces might be enclosed by the large Rob CTD (and/or a cofactor) and retained in an inactive manner; while ligand binding is able to change the ‘sequestration’ conformation of Rob into a ‘dispersal’ one, and the above enclosed residues of Rob NTD will be exposed to engage RNAP and finally initiate transcription. (iv) To identify the two alternative conformations of Rob-TAC, further single-molecule FRET assay was performed on the scaffold with a Cy5 fluorophore labelled on template strand of micF DNA2 and a Cy3B fluorophore on the 281-Cystine of Rob mutant (Supplementary Methods). The results showed only one FRET peak in each assay, and the FRET values were comparable and consistent with a distance of 5.5 nm from Rob-TACII rather than 7.7 nm from Rob-TACI (Supplementary Figure S14). Considering on this, we propose that the conformation of Rob-TACII is physiologically relevant and may have dominant significance for Rob-dependent transcription activation.

In summary, a model for Rob-dependent transcription regulation can be proposed (Figure 6B). When environmental stimuli are absent, Rob CTD keeps in inactive sequestration state, and thus transcription cannot be initiated. Upon ligand binding, Rob CTD undergoes conformation change, turns Rob into de-sequestration active state, and relocates itself in cells. If Rob encounters a robbox-containing promoter, Rob CTD along with its acidic loop plays critical roles in the coordination with Rob NTD, promote two HTH motifs to insert into the corresponding DNA major grooves, render DNA bent to form Rob-TACII and finally initiate transcription efficiently. Consistent with the fact that Rob interacts with both RNAP αCTD and σ70R4 as revealed in the structure of Rob-TAC, Rob was found to form larger complex with RNAP in the absence of promoter DNA (Supplementary Figure S10C), suggestive of a ‘pre-recruitment’ mechanism, implying Rob possibly also activates transcription through a ‘pre-recruitment’ mechanism like SoxS (58). Besides, Rob also binds DNA in the absence of RNAP (Supplementary Figure S10D), which enables the DNA-binding Rob to recruit RNAP. Therefore, it is most probably that Rob-dependent transcription activation is accomplished through both a ‘pre-recruitment’ mechanism and a general ‘recruitment’ mechanism, and leading to enhanced formation of Rob-TAC (Supplementary Figure S10) (13,58). However, whether Rob activates transcription at the promoter clearance stage yet needs to be further clarified.

Comparative structural analysis shows that Rob CTD endows the evolutionarily conserved GyrI-like domain as the other GyrI-like domain containing transcription regulators (53). These GyrI-like domains possess similar residue composition, stereochemical properties, and potential allosteric regulation mechanism, implying their significant physiological roles. This resembles the recently reported Bacillus subtilis BmrR (PDB: 7CKQ) (18) and E. coli EcmrR (PDB: 6XL5) involved in multidrug-sensing (55). However, there exists some big differences among them. Unlike the monomeric Rob, both BmrR and EcmrR function as dimers, sit on the distal face of promoter DNA, show no or few interactions with RNAP, and activate transcription mainly through promoter-distortion mechanism. This reveals that it is the two small conserved HTH motifs and the accessory acidic loop that accomplishes similar promoter remodeling functions to the above-mentioned dimers, which may reflect evolutionary significance to the AraC/XylS-family transcription factors.

By performing Pfam search using Rob sequence as a query, 2650 homologous protein sequences from various bacteria show the same architecture of ‘HTH_18 plus GyrI-like’ as Rob and are classified as transcription regulators, including AfrR and Caf1-R, revealing the global distribution and diverse functions of these ‘Rob-like regulators’. Further sequence analysis shows that critical residues from HTH motifs of Rob NTD and aromatic residues in Rob CTD are highly conserved in these Rob-like regulators, which is in good agreement with the key residues defined in our Rob-TAC, implying their general regulatory roles during the physiological adaptation processes. However, new molecular transcription activation mechanism about them is yet to be explored experimentally. Meanwhile, it also unveils the potential role of Rob in providing a novel target for the anti-bacterial drug discovery.

During the review process of this manuscript, Hao et al. published the structure of RamA-class II activator complex, which also visualized a homologous activator interacts with RNAP αCTD as well as σ70R4 (59), exhibiting similar interfaces as those in TAP-TAC and our Rob-TACII. Since CAP shares great similarity with TAP, though RNAP αCTD was invisible in CAP-TACII due to its high flexibility (18), it might probably engage RNAP in a similar dynamic manner. These data collectively reveal a general regulation mode for class II activator-dependent transcription activation. Considering that RNAP αCTD is conserved among all types of organisms, it could be generally applicable to other transcription factors in other organisms. However, not all class II activators remodel σ70R4 of RNAP by occluding the interactions between σ70R4 and -35 consensus element (such as TAP), this regulation mode of Rob might be an accessory way to efficiently remodel RNAP. As to class I promoters containing an activator binding site upstream of the –35 element, the corresponding activator is too far in distance to contact σ70R4, and it may variably activate transcription by combination with the highly distinctive determinants of RNAP αCTD (one or two), σ70R4 and promoter DNA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Accession number for cryo-EM density map: EMD-32166 for of Rob-TACI and EMD-32165 for Rob-TACII (Electron Microscopy Data Bank). Accession number for atomic coordinates: 7VWZ for of Rob-TACI and 7VWY for Rob-TACII (Protein Data Bank).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We appreciate Shenghai Chang at the Center of Cryo-Electron Microscopy in Zhejiang University School of Medicine and Guangyi Li, Fangfang Wang, Liangliang Kong at National Center for Protein Science, Shanghai for assistance with cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection. We thank the Core Facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine for technical support. We thank the Experiment Center for Science and Technology, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine for experimental assistance. We are grateful for helpful discussions and supports from Prof. Weishan Wang from State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author contributions: J. S., F.L.W., F.F.L., L.W., Y.X., A.J.W., Y.L.J., S.J., F.G., Z.Z.F., J.C.L., Y.Z. performed the experiments. A.J.W., J.S., S.J. performed cryo-EM sample preparations and data collections. Y.F., W.L. performed cryo-EM structure determination. J.S., F.L.W. performed biochemical experiments. J.S., W.L. designed the study, J.S., W.L., S.W., Z.S. and Y. F. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

Contributor Information

Jing Shi, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China; Department of Pathology of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Fulin Wang, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Fangfang Li, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Lu Wang, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Ying Xiong, Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics, Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; School of Physics, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory, Dongguan 523808, Guangdong, China.

Aijia Wen, Department of Biophysics, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China; Department of Pathology of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Yuanling Jin, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Sha Jin, Department of Biophysics, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China; Department of Pathology of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Fei Gao, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Zhenzhen Feng, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Jiacong Li, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Yu Zhang, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Zhuo Shang, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China.

Shuang Wang, Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics, Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; School of Physics, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory, Dongguan 523808, Guangdong, China.

Yu Feng, Department of Biophysics, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China; Department of Pathology of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Wei Lin, Department of Pathogen Biology, School of Medicine & Holistic Integrative Medicine, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China; Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Chinese Medicinal Resources Industrialization, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 210023, China; State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 210023, China; State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Natural Science Foundation of China [82072240, 81903756, 32000025, 12004420, 32071228]; Jiangsu Province of China [BK20190798 to W.L., BK20211302 to J.S.]; Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines [SKLNMKF202004 to W.L.]; Open Project of Chinese Materia Medica First-Class Discipline of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine [2020YLXK008 to W.L., 2020YLXK016 to J.S.]; Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation; Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor Talent Program (to W.L.); Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences [XDB37000000]; Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS [2021009]; the Opening Project of the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dorman C.J. Flexible response: DNA supercoiling, transcription and bacterial adaptation to environmental stress. Trends Microbiol. 1996; 4:214–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duval V., Lister I.M.. MarA, SoxS and Rob of Escherichia coli - Global regulators of multidrug resistance, virulence and stress response. Int. J. Biotechnol. Wellness Ind. 2013; 2:101–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Browning D.F., Busby S.J.. Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016; 14:638–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feklistov A., Sharon B.D., Darst S.A., Gross C.A.. Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2014; 68:357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feklistov A., Darst S.A.. Structural basis for promoter-10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase sigma subunit. Cell. 2011; 147:1257–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saecker R.M., Record M.T., Dehaseth P.L.. Mechanism of bacterial transcription initiation: RNA polymerase-promoter binding, isomerization to initiation-competent open complexes, and initiation of RNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2011; 412:754–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bae B., Feklistov A., Lass-Napiorkowska A., Landick R., Darst S.A.. Structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme open promoter complex. Elife. 2015; 4:e08504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Decker K.B., Hinton D.M.. Transcription regulation at the core: similarities among bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic RNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013; 67:113–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen J., Boyaci H., Campbell E.A.. Diverse and unified mechanisms of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021; 19:95–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Narayanan A., Vago F.S., Li K., Qayyum M.Z., Yernool D., Jiang W., Murakami K.S.. Cryo-EM structure of Escherichia coli sigma(70) RNA polymerase and promoter DNA complex revealed a role of sigma non-conserved region during the open complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018; 293:7367–7375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen J., Chiu C., Gopalkrishnan S., Chen A.Y., Olinares P.D.B., Saecker R.M., Winkelman J.T., Maloney M.F., Chait B.T., Ross W.et al.. Stepwise promoter melting by bacterial RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell. 2020; 78:275–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zuo Y., Steitz T.A.. Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell. 2015; 58:534–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng Y., Zhang Y., Ebright R.H.. Structural basis of transcription activation. Science. 2016; 352:1330–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu B., Hong C., Huang R.K., Yu Z., Steitz T.A.. Structural basis of bacterial transcription activation. Science. 2017; 358:947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi W., Jiang Y.N., Deng Y.B., Dong Z.G., Liu B.. Visualization of two architectures in class-II CAP-dependent transcription activation. PLoS Biol. 2020; 18:e3000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi J., Li F., Wen A., Yu L., Wang L., Wang F., Jin Y., Jin S., Feng Y., Lin W.. Structural basis of transcription activation by the global regulator Spx. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:10756–10769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lilic M., Darst S.A., Campbell E.A.. Structural basis of transcriptional de tel/fax details of the cactivation by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis intrinsic antibiotic-resistance transcription factor WhiB7. Mol. Cell. 2021; 81:2875–2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fang C., Li L., Zhao Y., Wu X., Philips S.J., You L., Zhong M., Shi X., O’Halloran T.V., Li Q.et al.. The bacterial multidrug resistance regulator BmrR distorts promoter DNA to activate transcription. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:6284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Skarstad K., Thony B., Hwang D.S., Kornberg A.. A novel binding protein of the origin of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J. Biol. Chem. 1993; 268:5365–5370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin R.G., Rosner J.L.. The AraC transcriptional activators. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001; 4:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tobes R., Ramos J.L.. AraC-XylS database: a family of positive transcriptional regulators in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:318–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cortes-Avalos D., Martinez-Perez N., Ortiz-Moncada M.A., Juarez-Gonzalez A., Banos-Vargas A.A., Estrada-de Los Santos P., Perez-Rueda E., Ibarra J.A.. An update of the unceasingly growing and diverse AraC/XylS family of transcriptional activators. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2021; 45:fuab020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gallegos M.T., Schleif R., Bairoch A., Hofmann K., Ramos J.L.. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997; 61:393–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Z., Demple B.. Sequence specificity for DNA binding by Escherichia coli SoxS and Rob proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 1996; 20:937–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosner J.L., Dangi B., Gronenborn A.M., Martin R.G.. Posttranscriptional activation of the transcriptional activator Rob by dipyridyl in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2002; 184:1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenberg E.Y., Bertenthal D., Nilles M.L., Bertrand K.P., Nikaido H.. Bile salts and fatty acids induce the expression of Escherichia coli AcrAB multidrug efflux pump through their interaction with Rob regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 2003; 48:1609–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakajima H., Kobayashi K., Kobayashi M., Asako H., Aono R.. Overexpression of the robA gene increases organic solvent tolerance and multiple antibiotic and heavy metal ion resistance in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995; 61:2302–2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Azam T.A., Ishihama A.. Twelve species of the nucleoid-associated protein from Escherichia coli. Sequence recognition specificity and DNA binding affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999; 274:33105–33113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griffith K.L., Fitzpatrick M.M., Keen E.F. III, Wolf R.E. Jr. Two functions of the C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli Rob: mediating “sequestration-dispersal” as a novel off-on switch for regulating Rob's activity as a transcription activator and preventing degradation of Rob by Lon protease. J. Mol. Biol. 2009; 388:415–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kwon H.J., Bennik M.H., Demple B., Ellenberger T.. Crystal structure of the Escherichia coli Rob transcription factor in complex with DNA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000; 7:424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rhee S., Martin R.G., Rosner J.L., Davies D.R.. A novel DNA-binding motif in MarA: the first structure for an AraC family transcriptional activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998; 95:10413–10418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taliaferro L.P., Keen E.F. III, Sanchez-Alberola N., Wolf R.E. Jr. Transcription activation by Escherichia coli Rob at class II promoters: protein-protein interactions between Rob's N-terminal domain and the sigma(70) subunit of RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 2012; 419:139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeng S.C., Chan H.H., Booy E.P., McKenna S.A., Unrau P.J.. Fluorophore ligand binding and complex stabilization of the RNA Mango and RNA Spinach aptamers. RNA. 2016; 22:1884–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Autour A., Jeng S.Y.C., Cawte A. D., Abdolahzadeh A., Galli A., Panchapakesan S.S.S., Rueda D., Ryckelynck M., Unrau P.J.. Fluorogenic RNA Mango aptamers for imaging small non-coding RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shi J., Gao X., Tian T., Yu Z., Gao B., Wen A., You L., Chang S., Zhang X., Zhang Y.et al.. Structural basis of Q-dependent transcription antitermination. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang F., Shi J., He D., Tong B., Zhang C., Wen A., Zhang Y., Feng Y., Lin W.. Structural basis for transcription inhibition by E. coli SspA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:9931–9942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Igarashi K., Ishihama A.. Bipartite functional map of the E. coli RNA polymerase alpha subunit: involvement of the C-terminal region in transcription activation by cAMP-CRP. Cell. 1991; 65:1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Svetlov V., Artsimovitch I.. Purification of bacterial RNA polymerase: tools and protocols. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015; 1276:13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mastronarde D.N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. JStruct Biol. 2005; 152:36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zheng S.Q., Palovcak E., Armache J.P., Verba K.A., Cheng Y.F., Agard D.A.. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017; 14:331–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rohou A., Grigorieff N.. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J of Struct Biol. 2015; 192:216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scheres S.H.W. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J of Struct Biol. 2012; 180:519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dangi B., Gronenborn A.M., Rosner J.L., Martin R.G.. Versatility of the carboxy-terminal domain of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase in transcriptional activation: use of the DNA contact site as a protein contact site for MarA. Mol. Microbiol. 2004; 54:45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Emsley P., Cowtan K.. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004; 60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adams P.D., Afonine P.V., Bunkoczi G., Chen V.B., Davis I.W., Echols N., Headd J.J., Hung L.W., Kapral G.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W.et al.. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. 2010; 66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J.. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009; 30:2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ariza R.R., Li Z., Ringstad N., Demple B.. Activation of multiple antibiotic resistance and binding of stress-inducible promoters by Escherichia coli Rob protein. J. Bacteriol. 1995; 177:1655–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Delihas N., Forst S.. MicF: an antisense RNA gene involved in response of Escherichia coli to global stress factors. J. Mol. Biol. 2001; 313:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shi J., Wen A.J., Zhao M.X., You L.L., Zhang Y., Feng Y.. Structural basis of sigma appropriation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:9423–9432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jair K.W., Yu X., Skarstad K., Thony B., Fujita N., Ishihama A., Wolf R.E. Jr. Transcriptional activation of promoters of the superoxide and multiple antibiotic resistance regulons by Rob, a binding protein of the Escherichia coli origin of chromosomal replication. J. Bacteriol. 1996; 178:2507–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ross W., Gosink K.K., Salomon J., Igarashi K., Zou C., Ishihama A., Severinov K., Gourse R.L.. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science. 1993; 262:1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Corbella M., Liao Q., Moreira C., Parracino A., Kasson P.M., Kamerlin S.C.L.. The N-terminal Helix-Turn-Helix Motif of Transcription Factors MarA and Rob Drives DNA Recognition. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2021; 125:6791–6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moreno A., Froehlig J.R., Bachas S., Gunio D., Alexander T., Vanya A., Wade H.. Solution Binding and Structural Analyses Reveal Potential Multidrug Resistance Functions for SAV2435 and CTR107 and Other GyrI-like Proteins. Biochemistry. 2016; 55:4850–4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tian W., Chen C., Lei X., Zhao J., Liang J.. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:W363–W367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang Y., Liu C., Zhou W., Shi W., Chen M., Zhang B., Schatz D.G., Hu Y., Liu B.. Structural visualization of transcription activated by a multidrug-sensing MerR family regulator. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shah I.M., Wolf R.E. Jr. Novel protein–protein interaction between Escherichia coli SoxS and the DNA binding determinant of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit: SoxS functions as a co-sigma factor and redeploys RNA polymerase from UP-element-containing promoters to SoxS-dependent promoters during oxidative stress. J. Mol. Biol. 2004; 343:513–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Savery N. J., Lloyd G. S., Kainz M., Gaal T., Ross W., Ebright R.H., Gourse R. L., Busby S. J.. Transcription activation at Class II CRP-dependent promoters: identifification of determinants in the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit. EMBO J. 1998; 17:3439–3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zafar M.A., Shah I.M., Wolf R.E. Jr. Protein-protein interactions between sigma(70) region 4 of RNA polymerase and Escherichia coli SoxS, a transcription activator that functions by the prerecruitment mechanism: evidence for “off-DNA” and “on-DNA” interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2010; 401:13–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hao M., Ye F., Jovanovic M., Kotta-Loizou I., Xu Q., Qin X., Buck M., Zhang X., Wang M.. Structures of class I and class II transcription complexes reveal the molecular basis of RamA-dependent transcription activation. Adv. Sci. 2021; 9:e2103669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Accession number for cryo-EM density map: EMD-32166 for of Rob-TACI and EMD-32165 for Rob-TACII (Electron Microscopy Data Bank). Accession number for atomic coordinates: 7VWZ for of Rob-TACI and 7VWY for Rob-TACII (Protein Data Bank).