Abstract

Background/Aims

Surgeons and endoscopists have started to use endoscopically inserted double pigtail stents (DPTs) in the management of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) leaks, including UGI anastomotic leaks. We investigated our own experiences in this patient population.

Methods

From March 2017 to June 2020, 12 patients had endoscopic internal drainage of a radiologically proven anastomotic leak after UGI surgery in two tertiary UGI centers. The primary outcome measure was the time to removal of the DPTs after anastomotic healing. The secondary outcome measure was early oral feeding after DPT insertion.

Results

Eight of the 12 patients (67%) required only one DPT, whereas four (33%) required two DPTs. The median duration of drainage was 42 days. Two patients required surgery due to inadequate control of sepsis. Of the remaining 10 patients, nine did not require a change in DPT before anastomotic healing. Nine patients were allowed oral fluids within the 1st week and a soft diet in the 2nd week. One patient was allowed clear oral feeds on the 8th day after DPT insertion.

Conclusions

Endoscopic internal drainage is becoming an established minimally invasive technique for controlling anastomotic leak after UGI surgery. It allows for early oral nutritional feeding and minimizes discomfort from conventional external drainage.

Keywords: Anastomotic leak, Drainage, Stents, Upper gastrointestinal tract

INTRODUCTION

Anastomotic leak from upper gastrointestinal (UGI) surgery is a major complication associated with significant perioperative morbidity, mortality, and prolonged hospital stay. Leak rates have been reported to vary between 3% and 8%.1-4 These leaks have also been shown to have an impact on the longterm survival of patients undergoing curative resection for gastric cancer.4-6 There is currently no consensus regarding the best modality of management.3 Options include conservative treatment with nil by mouth, total parenteral nutrition, and antibiotics, or endoscopic therapy or surgery. Recently, the number of endoscopic options has increased. These endoscopic options include fully covered self-expanding metal stents (SEMSs), endoscopic clips, endoscopic glue, fistula plugs, endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, drainage of the perianastomotic leak cavity through the anastomotic defect via a tube from the nose, and double pigtail stent (DPT) insertion.7-12 The fact that there are such a large number of options implies that none of these techniques are superior. This also means that there may be an opportunity to individualize treatment based on the location and anatomical features of the leak.

As such, we investigated our own experience and elucidated some limitations and contraindications to the use of DPTs in this patient population to help guide patient management.

METHODS

From March 2017 to June 2020, 12 patients had a DPT inserted for internal drainage of an anastomotic leak after UGI surgery in two tertiary UGI centers. Data were collected and retrospectively analyzed. Patient features and demographics are listed in Table 1. All patients, without exception, who had a radiologically proven anastomotic leak with a perianastomotic collection during the study period were included, and informed consent for the procedure as well as the potential need for multiple endoscopic sessions was obtained from all patients.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics (n=12)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 67.5±7.6 |

| Male sex | 10 (83.3) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 4 (33.3) |

| Postoperative days to diagnosis (day) | 6 (3–28) |

| Postoperative days to EUS insertion (day) | 13.5 (5–50) |

| Method of initial diagnosis | |

| Computed tomography | 9 (75.0) |

| Contrast swallow | 3 (25.0) |

| Preceding pathology | |

| Gastric GIST | 2 (16.7) |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 4 (33.3) |

| Gastroesophageal junctional adenocarcinoma | 4 (33.3) |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 2 (16.7) |

| Preceding operation | |

| Minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy | 3 (25.0) |

| Minimally invasive McKeown’s esophagectomy | 2 (16.7) |

| Open subtotal gastrectomy | 1 (8.3) |

| Open total gastrectomy | 1 (8.3) |

| Open proximal gastrectomy | 1 (8.3) |

| Open completion gastrectomy | 2 (16.7) |

| Laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with double tract reconstruction | 1 (8.3) |

| Laparoscopic total gastrectomy | 1 (8.3) |

| Location of leak | |

| Esophagogastric | 6 (50.0) |

| Esophagojejunal | 5 (41.7) |

| Gastrojejunal | 1 (16.7) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation, number (%), median (range).

EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

The procedure was performed under topical anesthesia and intravenous sedation with midazolam and fentanyl in an endoscopy suite equipped with image intensification facilities. Endoscopic internal drainage (EID) was preceded by an endoscopic evaluation of the location and size of the anastomotic leak. A guidewire was then inserted endoscopically into the perianastomotic collection under fluoroscopic guidance. A DPT was subsequently inserted via the Seldinger technique over the guidewire, with one end of the stent placed within the collection and the other end of the stent positioned into the gut lumen. The size and number of DPTs chosen depended on both the size of the defect and the collection. As a rule of thumb, if the adult esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) scope (9.9 mm diameter) could pass through the defect into the cavity, two DPTs were deployed, whereas if the defect was smaller than 9.9 mm, one DPT was deployed. In theory, if the leak is so large that the double pigtail spiral curves would not be able to hold the stent in place, then DPTs would not be inserted. Generally, the default DPT is a 7 Fr, 7 cm DPT as it fits through a standard adult EGD scope channel and is of a reasonable length. Once the stent had been deployed, diluted water-soluble contrast was injected to confirm contrast passage into the distal gut lumen with good drainage and minimal leakage into the cavity. A nasojejunal tube (NJT) was then routinely inserted, taking care not to dislodge the DPT during the procedure. NJT feeding commenced the day after the procedure, and unless the patient was quite malnourished, the NJT feeding was stopped, and the NJT was removed as soon as the patient was established on an oral liquid diet.

A repeat EGD was performed 6 weeks later in all patients to assess for any persistent leak and whether the DPT could be removed or had to be replaced. If there was still a persistent defect and associated cavity, the DPT was replaced. Figures 1 to 3 demonstrate the before and after effects of successful DPT deployment.

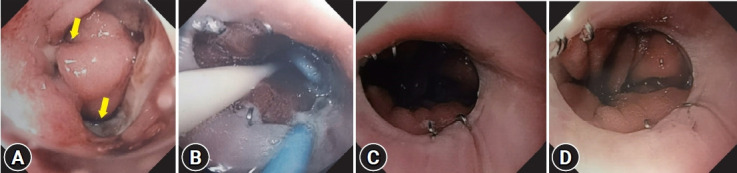

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic view of the healing process of anastomotic leak. (A) Esophagojejunal anastomotic leak (arrows). (B) Prior to removal of the pigtail stent. (C, D) Three months later.

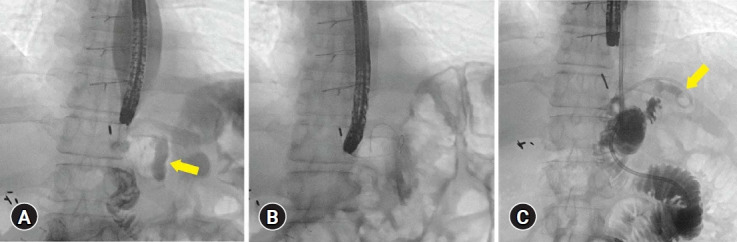

Fig. 2.

Fluoroscopy view during endoscopic internal drainage. (A) Perianastomotic collection (arrow). (B) A guidewire was inserted into the perianastomotic collection cavity under radiological guidance before double pigtail stent deployment. (C) Six weeks later, no obvious contrast leaks were observed (arrow). All contrast flowed into the jejunum. A small amount of contrast in the remnant cavity traveled from double pigtail stent in situ.

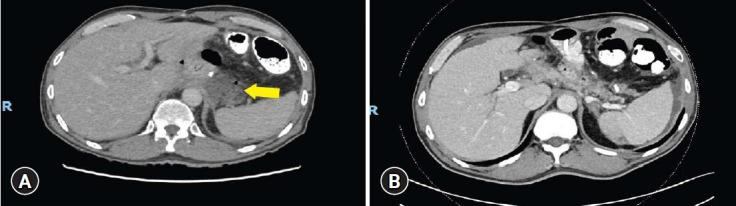

Fig. 3.

Abdominal computed tomography findings pre- and postendoscopic internal drainage (EID) insertion. (A) Pre-EID: perianastomotic collection was demonstrated (arrow). (B) Post-EID: the size of perianastomotic collection decreased and any contrast leakage into collection was not seen.

The primary outcome measure was the time to DPT removal after anastomotic healing. The secondary outcome measure was early oral feeding after DPT insertion. Anastomotic healing was defined as the absence of a contrast leak proven either endoscopically or radiologically.

Pre- and postprocedure inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, white cell count, and temperature were routinely monitored to confirm ongoing sepsis resolution after DPT insertion and during the phase of reinstitution of oral intake as well. Once patients were well established on an oral soft diet and sepsis was under control, antibiotics could be oralized, and the patients were discharged home with the DPTs in situ. They would then return for their relook EGD as an outpatient at the 6-week mark.

Ethical statements

Because this study was based on a retrospective analysis of existing clinical data, the requirement for informed patient consent was waived.

RESULTS

Of the 12 patients, 10 (83%) underwent surgery for gastric or esophageal malignancy, and two underwent surgery for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Five (42%) underwent open surgery. The average age was 67.5 years, with a male (83%) preponderance. Four patients (33%) had a medical history of type II diabetes mellitus. The types of anastomotic leaks were as follows: five esophagojejunal (42%), six esophagogastric (50%), and one gastrojejunal (8%). Table 1 summarizes the patients’ demographics and characteristics. Two patients underwent salvage surgery soon after DPT insertion and were excluded from the analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes. Table 2 summarizes the internal endoscopic drainage parameters and the results.

Table 2.

Endoscopic internal drainage parameters and results

| Variable | Result |

|---|---|

| No. of pigtail stents inserted at initial endoscopy | |

| 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 4 |

| No. with concomitant NJT insertion at initial endoscopy | 6 |

| No. who had TPN | 2 |

| No. with percutaneous drainage | 1 |

| No. needing a second endoscopy with DPT insertion | 1 |

| Time to oral intake (day) | |

| Clear fluids | 0–8 |

| Full fluids | 1–14 |

| Soft diet | 5–28 |

| Duration DPTs left in situ (day), median (range) | 42 (13–120) |

| No. in whom defect closed with DPT alone | 9 |

| No. requiring salvage surgery | 2 |

| Mortality | 1 |

NJT, nasojejunal tube; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; DPT, double pigtail stent.

The median time to diagnosis of a leak was 6 days postoperatively. Seven leaks were diagnosed within the 1st week, and one of them had a delayed diagnosis because the patient was not stable enough to undergo endoscopic evaluation for confirmation of an anastomotic leak. However, small locules of gas were seen next to the anastomosis on imaging. Another patient had a subclinical, delayed leak with a small collection seen on a computed tomography (CT) scan performed on readmission on day 28. The median time to EID was 13.5 days postoperatively. The time to EID was delayed to day 22 in one patient as the patient initially underwent external drainage on day 8, with a repeat water-soluble contrast study showing persistent leak before proceeding to EID. EID was also delayed in another patient due to other complications with hypovolemic shock due to bleeding from the left hepatic artery as well as from the first jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric artery both of these required interventional angioembolization. Subsequently, the patient had a persistent liver hematoma that required surgical evacuation.

The exact size of the anastomotic defect was not documented in all cases, but eight of the 12 patients (67%) only required one DPT, whereas four (33%) required two DPTs inserted at the same time. The median duration for which the DPT was left in situ was 42 days. The majority (90%) did not require a change in the DPT before anastomotic healing. One patient who required repeated replacement of the DPT was later found to have early cancer recurrence at the anastomosis and is discussed in greater detail below. There were no patients for whom the defect was so large that DPTs were not inserted.

Nine patients were allowed oral fluids within the 1st week and a soft diet by the 2nd week, while one patient was allowed oral fluids by day 8 and a soft diet by the 3rd week post-DPT insertion. There were no cases of luminal stenosis or any other anastomotic complication after DPT removal in cases successfully treated with DPTs.

Two patients required surgery due to inadequate control of sepsis. On day 9, the first patient was found to have an esophagogastric anastomotic leak following a minimally invasive McKeown esophagectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the mid-esophagus. Following the insertion of two DPTs, the patient developed an esophagotracheal fistula the next day. The fistulous opening in the trachea was at a site remote from the location of the DPTs. It was located just proximal to the location where the right main bronchus came off the trachea. Nevertheless, surgery was required as the silicone plastic Y-stent placed via rigid bronchoscopy did not seal the leak from the airway. Fully covered self-expanding metal Y-stents, which would have produced a better seal, are not available in our institution.

The second patient who required salvage surgery was eventually found to have distal obstruction due to an internal hernia. The patient underwent proximal gastrectomy and double tract reconstruction for a proximal gastric GIST. Esophagojejunal leak was diagnosed on postoperative day 6, and a DPT was inserted on the same day. After insertion of the DPT, the patient had persistently high output from his chest drains and developed atrial fibrillation with some hemodynamic instability. As such, he was returned to the theater, and a left posterolateral thoracotomy was performed. The defect was slightly proximal to the anastomosis and was controlled with a T-tube and then patched with a surrounding intercostal muscle patch. He continued to have a very high nasogastric tube output, and a follow-up CT scan showed a persistently dilated loop of the jejunum. He returned to the theater for a laparotomy, and it was found that he had an internal hernia of his biliopancreatic (BP) limb through his retrocolic window, causing proximal obstruction of the BP limb and partial compression of the Roux-limb. Due to the double tract reconstruction, the BP limb could still decompress retrogradely through the remnant stomach.

One patient had ongoing leakage despite several changes in the DPT. This was later found to be due to recurrent cancer at the anastomosis site. This patient eventually succumbed to metastatic disease, and the fistula never healed, progressing to a gastrocolic fistula in the later stages. Her postoperative course was complicated by superior mesenteric artery and splenic artery pseudoaneurysms and bleeding requiring repeated angioembolization procedures. The leak was persistent, with a resultant chronic abscess cavity that did not resolve with the deployment of an extra stent or with upsizing of the stents. The patient eventually developed a fistula to the colon, underwent laparoscopic cecostomy diversion, and covered SEMS. The patient subsequently developed multiple peritoneal metastases, and a decision was made for palliative care.

DISCUSSION

Anastomotic leak from UGI surgery is associated with increased mortality and prolonged hospital stay. Hence, early identification and treatment are key to reducing morbidity and mortality. Management options include conservative treatment with antibiotics, endoscopic therapy, or surgery. The choice of which management option to use is often made based on the patient’s clinical condition, timing of diagnosis, anastomotic level, and size of the defect. Although many new endoscopic therapies have recently been described, outcomes are variable, and there is still no consensus on the optimal approach. Surgical revision may also not be successful due to surrounding inflammation. Furthermore, patients often have poor nutritional status, anastomotic ischemia, or both, and these may predispose them to anastomotic dehiscence in the first place.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are key to reducing morbidity and mortality from anastomotic leaks. Leaks are proven either radiologically (e.g., water-soluble contrast swallow, or CT scan with demonstration of contrast leakage or a perianastomotic collection) or endoscopically, which allows for direct visualization of the luminal defect as well as assessment of the integrity of the rest of the anastomosis. Such leaks may be managed conservatively with a combination of antibiotics, nasogastric/jejunal tubes that bypass the site of anastomotic leakage and enable enteral nutrition, parenteral nutrition, and adequate drainage, which is traditionally often external. An increasing number of endoscopic modalities for treatment have emerged over the past two decades, including fully covered SEMS, endoscopic suturing, clips, tissue sealants, and even endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure therapy.7,8 However, these modalities have variable outcomes and are not without complications. For example, SEMSs have several disadvantages, including stent migration and stent erosion into large vessels, plus they are relatively expensive. Fibrin glue may require repeated applications. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure requires changing the endoscopic sponge under general anesthesia every three to 7 days or so, and the patients are not permitted any oral intake while the sponge is in situ. Surgical management is probably still indicated in cases with larger defects, failure of conservative treatment, or signs of diffuse peritonitis or sepsis with organ failure. Options include direct repair of the anastomosis, reconstruction of the anastomosis, or removal of the anastomosis with temporary diversion.1,3,7-13

EID is not a new concept and has been used with good success rates in the management of pancreatic pseudocysts via cyst gastrostomy.14-16 This same principle can be applied in the management of leaks and fistulas following both upper and lower gastrointestinal surgery using a DPT with one end in the gastrointestinal tract and the other in the fistula/collection. The use of EID with DPTs for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leaks is now well established in the literature.17-20 Surgeons and endoscopists have been quick to extrapolate this usage to the management of all UGI leaks, including UGI anastomotic leaks. This has been employed in a few centers with encouraging results.11,12 It is postulated that pigtail stents act as a foreign body on the edge of the leak and inside the cavity, promoting a reaction to try to seal off and extrude the foreign body toward the gut lumen.18,19 Compared to endoluminal vacuum therapy, patients with EID can generally commence oral feeding earlier, EID procedures can be performed without a general anesthetic, and there is less need for frequent and repeated endoscopic procedures.21-23

Nine out of 12 patients were successfully managed with EID using DPT in this case series. DPT allows for early oral nutritional feeding and potentially avoids conventional external drainage. The primary aim of DPT is to allow for adequate drainage and, therefore, to form a controlled situation. Some have also postulated that trauma to the orifice from the insertion of a DPT also helps promote reepithelialization of the internal opening and, therefore, healing of the anastomotic leak. Normal peristaltic movement will also help create negative pressure intraluminally, which will aid the flow of fluid/pus from the abdominal collection into the intraluminal space according to the Bernoulli principle. Removal of the stent will subsequently be followed by spontaneous closure, as all that is left is a tight “mold” of tissue around the stent in the extraluminal portion. Good early nutritional support and appropriate antibiotic coverage for sepsis control are important aspects of management. Therefore, EID aids patient recovery by enhancing nutritional status, increasing patient mobility without external drainage, and minimizing the length of hospital stay. All of these will help reduce other postoperative complications such as deep vein thrombosis and hospital-acquired pneumonia. However, surgical intervention is still likely required for uncontained leaks with generalized peritonitis, as these will not be adequately controlled with DPT.

The reasons for the non-healing of fistulas appear to be applicable to the failure of DPTs as well. It is well known that fistulas are generally not close in the presence of high fluid output, foreign bodies, radiation, inflammatory bowel disease, epithelialization of the tract, neoplasia, distal obstruction, and sepsis in the form of undrained abscesses. In one of our patients, failure was due to neoplasia, while in another, it was due to distal obstruction. In a third patient, it was due to the appearance of an esophagotracheal fistula, possibly due to inadequately drained sepsis. The use of steroids or other immunosuppressive medications, as well as poor patient nutrition, also negatively affect healing.

One of the limitations of this study was the lack of clear documentation regarding the size of the defect, as this data was retrospectively collected. The sample size is relatively small, but the results are consistent with other published data showing high success rates.12 It was also slightly subjective, depending on the judgment of the endoscopist with regard to the estimated defect size as well as the number of DPTs to be inserted during the procedure. The exact time to anastomotic healing is also unclear as repeat EGD was performed 6 weeks later in uncomplicated cases for reassessment and to determine if the DPT could be removed. Future studies with larger sample sizes to increase generalizability could consider repeating endoscopic evaluation earlier to allow for earlier stent removal and minimize the theoretical risk of DPT migration (either intraluminally or into the abdominal cavity). Plain radiography should be performed prior to reevaluation with endoscopy to confirm that the DPT is still present, as it often spontaneously extrudes itself, and endoscopy is no longer strictly necessary.

In conclusion, EID is a relatively safe and minimally invasive technique for controlling anastomotic leak after UGI surgery. Limitations to its use include neoplasia, distal obstruction, and other undrained septic foci. It can be expected that other foreign bodies, such as ineffectual endoscopic clips at the leak site, may also lead to non-closure. Likewise, inflammatory bowel disease, previous high-dose radiation, immunosuppressive drugs, and poor nutrition may reduce the chances of successful EID with DPTs.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: BCT, JTHT; Data curation: BCT, JC; Formal analysis: BCT, JC; Methodology: BCT, JC; Supervision: JTHT; Writing-original draft: BCT, JC; Writing-review & editing: JTHT, CHL, EKWL, WHC, BPMY.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lang H, Piso P, Stukenborg C, et al. Management and results of proximal anastomotic leaks in a series of 1114 total gastrectomies for gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:168–171. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh SJ, Choi WB, Song J, et al. Complications requiring reoperation after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: 17 years experience in a single institute. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carboni F, Valle M, Federici O, et al. Esophagojejunal anastomosis leakage after total gastrectomy for esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: options of treatment. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:515–522. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2016.06.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo HM, Lee HH, Shim JH, et al. Negative impact of leakage on survival of patients undergoing curative resection for advanced gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:734–740. doi: 10.1002/jso.22045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li QG, Li P, Tang D, et al. Impact of postoperative complications on long-term survival after radical resection for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4060–4065. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i25.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizk NP, Bach PB, Schrag D, et al. The impact of complications on outcomes after resection for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogalski P, Daniluk J, Baniukiewicz A, et al. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal perforations, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10542–10552. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bemelman WA, Baron TH. Endoscopic management of transmural defects, including leaks, perforations, and fistulae. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1938–1946.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahler G. Anastomotic leakage after upper gastrointestinal surgery: endoscopic treatment. Visc Med. 2017;33:202–206. doi: 10.1159/000475783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willingham FF, Buscaglia JM. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal leaks and fistulae. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1714–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hummel R, Bausch D. Anastomotic leakage after upper gastrointestinal surgery: surgical treatment. Visc Med. 2017;33:207–211. doi: 10.1159/000470884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot M, Yee G, Saxena P. Endoscopic modalities for upper gastrointestinal leaks, fistulae and perforations. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:171–176. doi: 10.1111/ans.13355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan JT, Kariyawasam S, Wijeratne T, et al. Diagnosis and management of gastric leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2010;20:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson MD, Walsh RM, Henderson JM, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical management of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:586–590. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31817440be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akshintala VS, Saxena P, Zaheer A, et al. A comparative evaluation of outcomes of endoscopic versus percutaneous drainage for symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:921–928. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, et al. Equal efficacy of endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:583–590.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foo JW, Balshaw J, Tan MH, et al. Leaks in fixed-ring banded sleeve gastrectomies: a management approach. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donatelli G, Dumont JL, Cereatti F, et al. Treatment of leaks following sleeve gastrectomy by endoscopic internal drainage (EID) Obes Surg. 2015;25:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donatelli G, Dumont JL, Cereatti F, et al. Endoscopic internal drainage as first-line treatment for fistula following gastrointestinal surgery: a case series. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E647–E651. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorenzo D, Guilbaud T, Gonzalez JM, et al. Endoscopic treatment of fistulas after sleeve gastrectomy: a comparison of internal drainage versus closure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodrigues-Pinto E, Pereira P, Sousa-Pinto B, et al. Retrospective multicenter study on endoscopic treatment of upper GI postsurgical leaks. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:1283–1299.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung CF, Hallit R, Muller-Dornieden A, et al. Endoscopic internal drainage and low negative-pressure endoscopic vacuum therapy for anastomotic leaks after oncologic upper gastrointestinal surgery. Endoscopy. 2022;54:71–74. doi: 10.1055/a-1375-8151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Still S, Mencio M, Ontiveros E, et al. Primary and rescue endoluminal vacuum therapy in the management of esophageal perforations and leaks. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;24:173–179. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.17-00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]