Abstract

Background

This study investigated the predictive value of the frailty index calculated using laboratory data and vital signs (FI-L) in patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Methods

This study included 508 patients (age 67.3±9.7 years, male 78.0%) who underwent CABG between 2018 and 2021. The FI-L, which estimates patients’ frailty based on laboratory data and vital signs, was calculated as the ratio of variables outside the normal range for 32 preoperative parameters. The primary endpoints were operative and medium-term all-cause mortality. The secondary endpoints were early postoperative complications and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs).

Results

The mean FI-L was 20.9%±10.9%. The early mortality rate was 1.6% (n=8). Postoperative complications were atrial fibrillation (n=148, 29.1%), respiratory complications (n=38, 7.5%), and acute kidney injury (n=15, 3.0%). The 1- and 3-year survival rates were 96.0% and 88.7%, and the 1- and 3-year cumulative incidence rates of MACCEs were 4.87% and 8.98%. In multivariable analyses, the FI-L showed statistically significant associations with medium-term all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.042; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.010–1.076), MACCEs (subdistribution HR, 1.054; 95% CI, 1.030–1.078), atrial fibrillation (odds ratio [OR], 1.02; 95% CI, 1.002–1.039), acute kidney injury (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.014–1.108), and re-operation for bleeding (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.032–1.152). The minimal p-value approach showed that 32% was the best cutoff for the FI-L as a predictor of all-cause mortality post-CABG.

Conclusion

The FI-L was a significant prognostic factor related to all-cause mortality and postoperative complications in patients who underwent CABG.

Keywords: Risk assessment, Coronary artery bypass, Frailty

Introduction

For patients with coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is recommended as the standard treatment along with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1,2]. With advances in PCI, the indications for CABG and PCI are being discussed. However, CABG is still the recommended first-line treatment for severe coronary artery diseases, such as 3-vessel disease and left main disease [2-5].

The Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) score and the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II) have been widely used to evaluate the risk of cardiac surgery, including CABG, and have been proven to effectively predict postoperative mortality and morbidity [6-8].

In addition to these risk assessment methods, frailty has recently emerged as a factor influencing patients’ clinical course after cardiac surgery [9,10]. Among the various tools available to measure patients’ frailty, the frailty index calculated using laboratory data and vital signs (FI-L) is an objective and easy-to-use tool to evaluate patients’ frailty, because it uses the results of routine preoperative laboratory data, blood pressure, and pulse rate [11]. This study was conducted to elucidate the clinical correlation between frailty scores and surgical outcomes in patients who underwent CABG.

Methods

Patient characteristics

In total, 519 patients who underwent primary isolated CABG at Seoul National University Hospital between January 2018 and March 2021 were assessed for eligibility. After excluding 11 patients who underwent emergency operations, 508 patients (78.0% male) were enrolled in this study. The mean age at surgery was 67.3±9.7 years. The median STS scores and EuroSCORE II were 1.3 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.9– 2.3) and 0.9 (IQR, 0.5–1.5), respectively. The most common comorbidities identified were hypertension (n=337, 66.3%) and diabetes mellitus (n=297, 58.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics and risk factors in the study population (n=508)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 67.3±9.7 |

| Sex (male) | 396 (78.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.7±3.6 |

| STS score (%) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) |

| EuroSCORE II (%) | 1.3 (0.9–2.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | |

| 3 VD | 361 (71.1) |

| Left main disease with 3VD | 143 (28.2) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 295 (58.1) |

| History of percutaneous coronary intervention | 127 (25.0) |

| Risk factors | |

| Hypertension | 337 (66.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 297 (58.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 257 (50.6) |

| History of stroke | 59 (11.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 112 (22.0) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 26 (5.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23 (4.5) |

| Left ventricular dysfunction (EF <0.35) | 45 (8.9) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation, number (%), or median (interquartile range).

STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; 3 VD, three-vessel disease; EF, ejection fraction.

Operative data

All operations in the study were performed through median sternotomy, except in 20 patients who underwent robot-assisted minimally invasive direct CABG. Off-pump CABG and on-pump beating CABG were performed in 498 patients (98.0%) and 10 patients (2.0%), respectively. The left internal thoracic artery was used in 497 patients (97.8%). The saphenous vein, right internal thoracic artery, and right gastroepiploic artery were used in 434 patients (85.4%), 45 patients (8.9%), and 8 patients (1.6%), respectively. The mean number of distal anastomoses was 3.4±1.1.

Frailty index calculation and evaluation of clinical outcomes

The FI-L was calculated using the patients’ laboratory data and vital signs [11]. It was calculated as the ratio of variables outside the normal range among 32 preoperative parameters, including vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate) and routine laboratory test results using the last preoperative laboratory test results and vital signs, usually obtained the day before surgery. The formula used was FI-L (%)=(number of variables with abnormal results/number of variables measured)×100 (Table 2). A higher score indicated greater frailty.

Table 2.

Frailty-related parameters

| Parameter | Normal range |

|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | 90–140 (mm Hg) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 40–60 (mm Hg) |

| Pulse rate | 60–99 (bpm) |

| Mean arterial pressure | 70–105 (mm Hg) |

| Pulse pressure | 30–65 (mm Hg) |

| Bicarbonate | 21–29 (mmol/L) |

| Calcium | 8.8–10.5 (mg/dL) |

| Phosphorus | 2.5–4.5 (mg/dL) |

| Glucose | 70–110 (mg/dL) |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 10–26 (mg/dL) |

| Uric acid | 3.0–7.0 (mg/dL) |

| Cholesterol | 0–240 (mg/dL) |

| Total protein | 6.0–8.0 (g/dL) |

| Albumin | 3.3–5.2 (g/dL) |

| Total bilirubin | 0.2–1.2 (mg/dL) |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 30–115 (U/L) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 100–225 (U/L) |

| Creatinine | 0.7–1.4 (mg/dL) |

| Sodium | 135–145 (mEq/L) |

| C-reactive protein | 0–0.5 (mg/dL) |

| Triglyceride | 0–200 (mg/dL) |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 35–55 (mg/dL) |

| Hemoglobin | 12–16 (g/dL) |

| Mean cell volume | 79–95 (fL) |

| Red cell distribution width | 11.5–14.5 (%) |

| Platelet | 130–400 (1,000 cells/µL) |

| Segmented neutrophil | 50–75 (%) |

| Glycohemoglobin | 4–6.4 (%) |

| Vitamin B12 | 200–1,000 (pg/dL) |

| Vitamin D | 19.6–54.3 (ng/dL) |

| Folate | 3–15 (ng/mL) |

| Iron, refrigerated | 50–170 (µg/dL) |

The primary endpoints of this study were operative and medium-term all-cause mortality after CABG. Secondary outcomes were early postoperative complications and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs). The definition of operative mortality was all-cause death during index hospitalization or within 30 postoperative days. After discharge, regular follow-up was performed at 3- to 6-month intervals in the outpatient clinic. Patients were contacted by telephone if the last visit did not occur on the scheduled date. In addition, data pertaining to death from any cause or cardiac events were obtained from death certificates provided by Statistics Korea. The definition of cardiac death was death pertaining to cardiac events including sudden death. MACCEs were defined as cardiac death, cerebrovascular accident, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction, and coronary re-intervention, including PCI and redo-CABG. The median follow-up duration was 18.2 months (IQR, 10.8–29.4 months).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS ver. 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For data presentation, continuous variables were described as the mean with standard deviation for data with normal distribution or the median with IQR for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were presented as the number and percentage of participants. Risk factors associated with operative mortality were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression. The validity of the logistic regression model was verified with the Hosmer Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (p=0.243). The survival rate during the follow-up period was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and risk factors associated with medium-term all-cause mortality were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model. The cumulative incidence rates of MACCEs were estimated with non-cardiac death as a competing risk factor for the events. The risk factors for MACCEs were analyzed using the Fine-Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model. Preoperative variables and operation-related factors with a p-value less than 0.10 in univariable analyses were included in multivariable analyses. The optimal cutoff values of continuous variables for predicting time-related events were estimated using the minimal p-value approach [12].

Ethics statement

The institutional review board at Seoul National University Hospital reviewed the protocol of this study and approved it as a retrospective cohort study with minimal risk. The requirement for individual consent was waived according to the institutional guidelines for obtaining consent (approval no., 2108-068-1244).

Results

Early clinical outcomes

The operative mortality rate was 1.6% (n=8). The causes of early death included septic shock (n=3, 0.6%), acute mesenteric ischemia (n=2, 0.4%), pulmonary thromboembolism (n=1, 0.2%), severe limb ischemia (n=1, 0.2%), and intractable native coronary artery spasm (n=1, 0.2%). Postoperative complications included atrial fibrillation (n=148, 29.1%), respiratory complications (n=38, 7.5%), acute kidney injury (n=15, 3.0%), and re-operation for bleeding (n=10, 2.0%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Early clinical outcomes (n=508)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Operative mortality | 8 (1.6) |

| Postoperative complication | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 148 (29.1) |

| Respiratory complications | 38 (7.5) |

| Acute kidney injury | 15 (3.0) |

| Re-operation for bleeding | 10 (2.0) |

| Low cardiac output syndrome | 9 (1.8) |

| Perioperative myocardial infarction | 6 (1.2) |

| Mediastinitis | 4 (0.8) |

| Stroke | 1 (0.2) |

Medium-term clinical outcomes

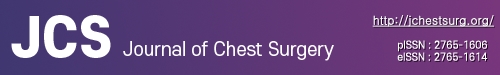

Late death occurred in 23 patients. The 1- and 3-year overall survival rates were 96.0% and 88.7%, respectively (Fig. 1A). During the follow-up period, MACCEs occurred in 28 patients. Cardiac death, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction, coronary re-intervention, and cerebrovascular accident occurred in 9, 1, 12, and 7 patients, respectively. The 1- and 3-year cumulative incidence rates of MACCEs were 4.87% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.16–7.1) and 8.98% (95% CI, 6.13–12.4), respectively (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) A Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival and (B) a cumulative incidence function for major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs).

Impact of FI-L on primary and secondary endpoints

The mean FI-L of the study patients was 20.9%±10.9% (range, 0%–56.3%). The multivariable logistic regression model showed that sex, EuroSCORE II, and peripheral vascular disease were significant risk factors associated with operative mortality (Table 4). The FI-L showed a significant association with all-cause mortality, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.042 (95% CI, 1.010–1.076) in the Cox proportional hazards analysis (Table 5).

Table 4.

Risk factor analysis for operative mortality

| Variable | Univariable analysis p-value | Multivariable analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Sex (female) | 0.072 | 4.914 (1.081–22.222) | 0.039 |

| Age | 0.493 | ||

| STS score | 0.494 | ||

| EuroSCORE II | <0.001 | 1.229 (1.112–1.359) | <0.001 |

| FI-La) | 0.054 | - | - |

| Hypertension | 0.817 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.350 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.973 | ||

| History of stroke | 0.937 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.072 | 4.791 (1.032–22.235) | 0.045 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | >0.999 | ||

| Atrial fibrillationa) | 0.017 | - | - |

| Left ventricular dysfunction (EF <35%)a) | 0.012 | - | - |

| History of coronary intervention | >0.999 | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0.361 | ||

| On-pump beating CABG | 0.999 | ||

| Use of the left internal thoracic artery | 0.999 | ||

| No. of anastomoses | 0.457 | ||

CI, confidence interval; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; FI-L, frailty index based on laboratory data and vital signs; EF, ejection fraction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

a)Variables were included in the multivariable analysis but were dropped during stepwise analysis.

Table 5.

Risk factor analysis for overall survival

| Variable | Univariable analysis (p-value) | Multivariable analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Sex (female) | 0.687 | ||

| Age | 0.001 | 1.054 (1.003–1.106) | 0.036 |

| STS scorea) | 0.041 | - | - |

| EuroSCORE II | <0.001 | 1.121 (1.051–1.196) | <0.001 |

| FI-L | <0.001 | 1.042 (1.010–1.076) | 0.010 |

| Hypertension | 0.827 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.932 | ||

| Dyslipidemiaa) | 0.017 | - | - |

| History of strokea) | 0.037 | - | - |

| Peripheral vascular disease | <0.001 | 3.472 (1.621–7.435) | 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.314 | ||

| Atrial fibrillationa) | 0.007 | - | - |

| Left ventricular dysfunction (EF <35%)a) | <0.001 | - | - |

| History of coronary interventiona) | 0.074 | - | - |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0.204 | ||

| On-pump beating CABGa) | 0.038 | - | - |

| Use of the left internal thoracic artery | 0.863 | ||

| No. of anastomoses | 0.437 | ||

CI, confidence interval; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; FI-L, frailty index based on laboratory data and vital signs; EF, ejection fraction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

a)Variables were included in the multivariable analysis but were dropped out during stepwise analysis.

Among the postoperative complications, the FI-L showed significant associations with atrial fibrillation (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.002–1.039), acute kidney injury (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.014–1.108), and reoperation for bleeding (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.032–1.152) in each multivariable analysis. The FI-L was a significant risk factor related to MACCEs, with a subdistribution HR (sHR) of 1.054 (95% CI, 1.030–1.078) in the Fine–Gray proportional subdistribution hazard model analysis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Risk factor analysis for major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

| Variable | Univariable analysis (p-value) | Multivariable analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| sHR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Sex (female) | 0.596 | ||

| Age | 0.113 | ||

| STS scorea) | 0.053 | - | - |

| EuroSCORE IIa) | <0.001 | - | - |

| FI-L | <0.001 | 1.054 (1.030–1.078) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.862 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.110 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.230 | ||

| History of stroke | 0.216 | ||

| Peripheral vascular diseasea) | 0.013 | - | - |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasea) | 0.099 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.016 | 3.118 (1.280–7.596) | 0.012 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction (EF <35%)a) | 0.019 | - | - |

| History of coronary intervention | 0.153 | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0.393 | ||

| On-pump beating CABG | 0.590 | ||

| Use of the left internal thoracic artery | 0.765 | ||

| No. of anastomoses | 0.805 | ||

sHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II; FI-L, frailty index based on laboratory data and vital signs; EF, ejection fraction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

a)Variables were included in the multivariable analysis but were dropped during stepwise analysis.

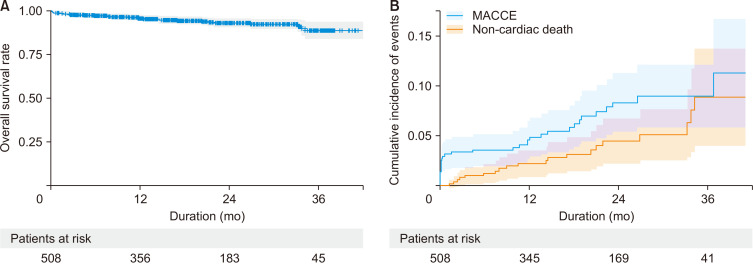

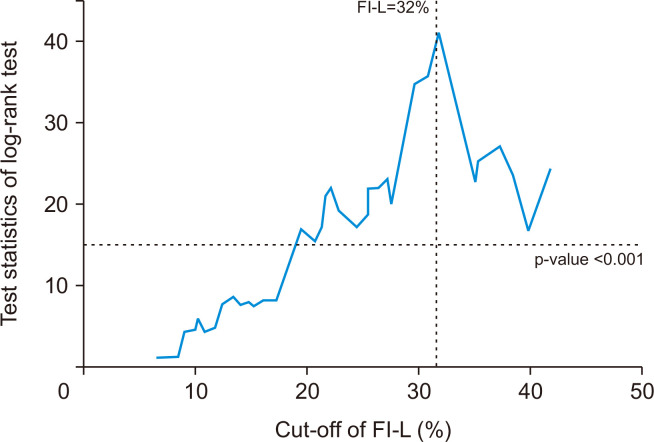

An FI-L of 32% was the best cutoff to predict the medium-term all-cause mortality after CABG according to the minimum p-value approach (Fig. 2). There were significant differences in all-cause mortality and MACCEs between the group with an FI-L >32%, and the group with an FI-L ≤32% (p<0.001 for both) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

A test statistic for each cutoff value of the frailty index based on laboratory data and vital signs (FI-L) in the log-rank test.

Fig. 3.

(A) Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival and (B) cumulative incidence functions for major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) according to the cutoff value of the frailty index based on laboratory data and vital signs (FI-L).

Discussion

This study had 2 main findings. First, the FI-L was shown to be a significant risk factor associated with medium-term all-cause mortality, MACCEs, and early postoperative complications in patients who underwent CABG. Second, frailty in CABG patients was defined as an FI-L more than 32%.

Since CABG was first introduced in the 1950s, surgical techniques and perioperative care have been advanced. However, old age remains a concern when performing cardiac surgery, including CABG [13], and current risk prediction models, such as the STS score and EuroSCORE II, include age as a factor for risk calculation [6,7]. In contrast, previous studies have shown that cardiac surgery could be performed with low risk, even in elderly patients [14-16]. This discrepancy might be explained by the concept of frailty, which refers to the loss of the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis in response to external stressful events. Frailty, rather than chronological age, might affect clinical outcomes after surgical treatment [11].

Previous studies have suggested various scales for discriminating frailty in patients [9]. These included various indicators of frailty, such as the modified Fried frailty criteria, the Katz index of independence in activities of daily living, the modified multidimensional geriatric assessment, and the modified geriatric baseline examination. These frailty indicators use questionnaires, physical examination of functional performance, subjective assessment of physicians, and some laboratory tests to evaluate patients’ frailty. In this study, the FI-L was adopted to measure patients’ frailty, and the study results revealed its association with early- and medium-term clinical outcomes after CABG. Because the FI-L consists of 32 frailty parameters, including 5 parameters derived from vital signs and 27 parameters from laboratory tests, it is objective, easy to measure, and can be adopted during the routine preoperative evaluation of patients. The clinical usefulness of the FI-L in assessing patients’ frailty and its association with operative outcomes after cardiac surgery has been demonstrated in previous studies [17-19]. In the present study, it was significantly associated with important postoperative complications such as atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, re-operation for bleeding, and medium-term MACCEs, although it was not a significant factor for operative mortality. However, the relatively small number of operative mortality events in this study might have weakened the statistical power of the risk factor analysis for operative mortality. Because the FI-L is associated with adverse clinical outcomes such as all-cause mortality and MACCEs, efforts should be made to optimize patients’ medical care, including timely evaluations during outpatient clinic visits, particularly for patients with a high FI-L.

In addition to the clinical implications of the FI-L, we adopted the minimal p-value approach to identify the optimal cutoff point that differentiates clinical outcomes after CABG, and 32% was found to be the best cutoff value for the FI-L to predict worse clinical outcomes after CABG.

This study had some limitations that should be recognized. First, the present study was designed as a retrospective observational cohort study and was performed at a single institution. Second, the follow-up duration of the study population was relatively short, and the study population was relatively small. Frailty parameters have been routinely measured at our institution since January 2018; therefore, the longest follow-up period was 40 months. Future studies should focus on the analysis of long-term outcomes. Third, as mentioned previously, the number of events for operative mortality was relatively small, which could have weakened the statistical power of the risk factor analysis. Fourth, each component of MACCEs was not separately analyzed because the number of events for each component was relatively small.

In conclusion, in addition to chronological age, the frailty of patients is significantly associated with clinical outcomes after CABG. Therefore, combining frailty scores with current risk prediction models might be helpful in the decision-making process for patients who have coronary artery disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Alexander JH, Smith PK. Coronary-artery bypass grafting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1954–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e123–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohr FW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial. Lancet. 2013;381:629–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohr F, Redwood S, Venn G, et al. TCT-43 final five-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial: optimal revascularization strategy in patients with three-vessel disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(17_Suppl):B13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kappetein AP, Feldman TE, Mack MJ, et al. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of left main and/or three-vessel disease: 3-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2125–34. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:734–45. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahian DM, O'Brien SM, Filardo G, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1--coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1 Suppl):S2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PG, Wallach JD, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis comparing established risk prediction models (EuroSCORE II, STS Score, and ACEF Score) for perioperative mortality during cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1574–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepehri A, Beggs T, Hassan A, et al. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:3110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohn B, Choi JW, Hwang HY, Jang MJ, Kim KH, Kim KB. Frailty index is associated with adverse outcomes after aortic valve replacement in elderly patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34:e205. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman DG, Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Dangers of using "optimal" cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:829–35. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu C, Camacho FT, Wechsler AS, et al. Risk score for predicting long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2012;125:2423–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaidi AM, Fitzpatrick AP, Keenan DJ, Odom NJ, Grotte GJ. Good outcomes from cardiac surgery in the over 70s. Heart. 1999;82:134–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit?: quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2129–35. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalrymple-Hay MJ, Alzetani A, Aboel-Nazar S, Haw M, Livesey S, Monro J. Cardiac surgery in the elderly. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:61–6. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(98)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirose H, Amano A, Yoshida S, Takahashi A, Nagano N, Kohmoto T. Coronary artery bypass grafting in the elderly. Chest. 2000;117:1262–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blodgett JM, Theou O, Howlett SE, Rockwood K. A frailty index from common clinical and laboratory tests predicts increased risk of death across the life course. Geroscience. 2017;39:447–55. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howlett SE, Rockwood MR, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Standard laboratory tests to identify older adults at increased risk of death. BMC Med. 2014;12:171. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]