Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of burnout among primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries and to identify factors associated with burnout.

Methods

We systematically searched nine databases up to February 2022 to identify studies investigating burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries. There were no language limitations and we included observational studies. Two independent reviewers completed screening, study selection, data extraction and quality appraisal. Random-effects meta-analysis was used to estimate overall burnout prevalence as assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment. We narratively report factors associated with burnout.

Findings

The search returned 1568 articles. After selection, 60 studies from 20 countries were included in the narrative review and 31 were included in the meta-analysis. Three studies collected data during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic but provided limited evidence on the impact of the disease on burnout. The overall single-point prevalence of burnout ranged from 2.5% to 87.9% (43 studies). In the meta-analysis (31 studies), the pooled prevalence of a high level of emotional exhaustion was 28.1% (95% confidence interval, CI: 21.5–33.5), a high level of depersonalization was 16.4% (95% CI: 10.1–22.9) and a high level of reduced personal accomplishment was 31.9% (95% CI: 21.7–39.1).

Conclusion

The substantial prevalence of burnout among primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries has implications for patient safety, care quality and workforce planning. Further cross-sectional studies are needed to help identify evidence-based solutions, particularly in Africa and South-East Asia.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer la prévalence de l’épuisement professionnel (burnout) chez les professionnels des soins de santé primaires dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire et identifier les facteurs associés à l’épuisement professionnel.

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué une recherche systématique dans neuf bases de données jusqu’en février 2022 afin d’identifier les études portant sur l’épuisement chez les professionnels des soins de santé primaires dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire. Il n’y avait aucune limitation linguistique et nous avons inclus des études observationnelles. Deux examinateurs indépendants ont effectué le screening, la sélection des études, l’extraction des données et l’évaluation de la qualité. Une méta-analyse à effets aléatoires a été utilisée pour estimer la prévalence globale de l’épuisement professionnel, évaluée à l’aide des sous-échelles d’épuisement émotionnel, de dépersonnalisation et d’accomplissement personnel du Maslach Burnout Inventory. Voici un rapport narratif des facteurs associés à l’épuisement professionnel.

Résultats

Nos recherches ont permis d’identifier 1568 articles. Après sélection, 60 études provenant de 20 pays ont été incluses dans l’examen narratif, et 31 ont été incluses dans la méta-analyse. Trois études ont recueilli des données pendant la pandémie de Covid-19, mais ont fourni des preuves limitées de l’impact de cette maladie sur l’épuisement professionnel. La prévalence globale à point unique de l’épuisement professionnel variait de 2,5 à 87,9% (43 études). Dans la méta-analyse (31 études), la prévalence collective d’un niveau élevé d’épuisement émotionnel était de 28,1% (intervalle de confiance (IC) à 95%: 21,5–33,5), un niveau élevé de dépersonnalisation était de 16,4% (IC à 95%: 10,1–22,9) et un niveau élevé d’accomplissement personnel réduit était de 31,9% (IC à 95%: 21,7–39,1).

Conclusion

La prévalence notable de l’épuisement professionnel chez les professionnels des soins de santé primaires dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire a des implications pour la sécurité des patients, la qualité des soins et la planification des effectifs. D’autres études transversales sont nécessaires pour aider à identifier des solutions empiriques, en particulier en Afrique et en Asie du Sud-Est.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar la prevalencia del desgaste profesional entre los profesionales de la atención primaria de salud en los países de ingresos bajos y medios e identificar los factores que se asocian a este síndrome.

Métodos

Se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en nueve bases de datos hasta febrero de 2022 para identificar estudios que investigaran el desgaste profesional en profesionales de la atención primaria de países de ingresos bajos y medios. No hubo limitaciones de idioma y se incluyeron estudios observacionales. Dos revisores independientes completaron el cribado, la selección de estudios, la extracción de datos y la evaluación de la calidad. Se utilizó el metanálisis de efectos aleatorios para estimar la prevalencia global del desgaste profesional, evaluada mediante las subescalas de agotamiento emocional, despersonalización y realización personal del Maslach Burnout Inventory. En este documento, se describen los factores asociados al síndrome de desgaste profesional.

Resultados

La búsqueda arrojó 1568 artículos. Tras la selección, se incluyeron 60 estudios de 20 países en la revisión narrativa y 31 en el metanálisis. Tres estudios recopilaron datos durante la pandemia de la enfermedad por coronavirus de 2019, pero proporcionaron pruebas limitadas sobre el impacto de la enfermedad en el desgaste profesional. La prevalencia global de un único punto sobre el desgaste profesional osciló entre el 2,5 y el 87,9 % (43 estudios). En el metanálisis (31 estudios), la prevalencia conjunta de un nivel alto de agotamiento emocional fue del 28,1 % (intervalo de confianza del 95 %, IC: 21,5-33,5), un nivel alto de despersonalización fue del 16,4 % (IC del 95 %: 10,1-22,9) y un nivel alto de disminución de la realización personal fue del 31,9 % (IC del 95 %: 21,7-39,1).

Conclusión

La considerable prevalencia del desgaste profesional entre los profesionales de la atención primaria en los países de ingresos bajos y medios tiene implicaciones para la seguridad de los pacientes, la calidad de la atención y la planificación del personal. Se necesitan más estudios transversales para ayudar a identificar soluciones fundamentadas en la evidencia, en especial en África y Asia Sudoriental.

ملخص

الغرض

تقدير مدى انتشار الإرهاق بين أخصائيي الرعاية الصحية الأولية في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض والدخل المتوسط، وتحديد العوامل المرتبطة بالإرهاق.

الطريقة قمنا بالبحث بشكل منهجي في تسع قواعد للبيانات حتى فبراير/شباط 2022، لتحديد الدراسات التي تقوم بالاستقصاء في الإنهاك لدى أخصائيي الرعاية الأولية في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفضة والدخل المتوسطة. لم تكن هناك قيود تتعلق باللغة، وقمنا بتضمين دراسات قائمة على الملاحظات. قام اثنان من المراجعين المستقلين بإكمال عمليات الفحص، وتحديد الدراسة، واستخراج البيانات، وتقييم الجودة. تم استخدام التحليل التلوي للتأثيرات العشوائية لتقدير مدى انتشار الإرهاق الكلي كما تم تقييمه باستخدام المقاييس الفرعية Maslach Burnout Inventory للإرهاق العاطفي، وفقدان الشخصية، والإنجاز الشخصي. نحن نقوم بالإبلاغ عن العوامل المرتبطة بالإرهاق عن طريق السرد.

النتائج أسفر البحث عن 1568 مقالةً. بعد الاختيار، تم تضمين 60 دراسةً من 20 دولة في المراجعة السردية، وتضمين 31 دراسة في التحليل التلوي. جمعت ثلاث دراسات البيانات أثناء جائحة مرض فيروس كورونا 2019، ولكنها قدمت أدلة محدودة على تأثير المرض على الإرهاق. تراوح معدل الانتشار الكلي للإرهاق في نقطة واحدة من 2.5 إلى 87.9% (43 دراسة). في التحليل التلوي (31 دراسة)، كان معدل الانتشار المجمع لمستوى عالٍ من الإرهاق العاطفي هو 28.1% (بفاصل ثقة مقداره 95%: 21.5 إلى 33.5)، ومستوى عالٍ من فقدان الشخصية هو 16.4% (بفاصل ثقة مقداره 95%: 10.1 إلى 22.9)، ومستوى عالٍ من الإنجاز الشخصي هو 31.9% (بفاصل ثقة مقداره 95%: 21.7 إلى 39.1).

الاستنتاج إن الانتشار الكبير للإرهاق بين أخصائيي الرعاية الصحية الأولية في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض والدخل المتوسط، له آثار على سلامة المرضى، وجودة الرعاية، وتخطيط القوى العاملة. هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات المقطعية للمساعدة في تحديد الحلول القائمة على الأدلة، وخاصة في أفريقيا وجنوب شرق آسيا.

摘要

目的

评估低收入和中等收入国家初级医疗护理工作者的职业倦怠率,并确定引起职业倦怠的相关因素。

方法

我们系统地搜索了截至 2022 年 2 月的九个数据库,以确定调查低收入和中等收入国家初级医疗护理工作者职业倦怠情况的研究。搜集的研究没有语言限制,而且我们纳入了观察性研究。由两位独立评审员完成了筛查、研究选择、数据提取和质量评估。我们采用随机效应元分析法来评估整体职业倦怠率,并使用《马氏职业倦怠量表》作为子量表来评估情绪疲劳、人格解体和个人成就感的情况。我们对于职业倦怠相关的因素进行了叙述性报告。

结果

搜索出 1568 篇论文。经过筛选,来自 20 个国家的 60 项研究被纳入叙述性回顾,31 项研究被纳入元分析。有三项研究收集了新型冠状病毒肺炎大流行期间的数据,但该疾病对职业倦怠的影响方面的证据有限。职业倦怠的总体单点流行率范围为 2.5% 至 87.9%(43 项研究)。在元分析(31 项研究)中,严重级别情绪疲劳的综合流行率为 28.1% (95% 置信区间,CI:21.5–33.5),严重级别人格解体的流行率为 16.4% (95% CI: 10.1-22.9),个人成就感严重缺失的流行率为 31.9% (95% CI: 21.7-39.1)。

结论

低收入和中等收入国家初级医疗护理工作者的高职业倦怠率对患者安全、护理质量和人力规划会产生影响。需要开展进一步的横断面研究来帮助确定有证据支持的解决方案,特别是在非洲和东南亚地区。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить распространенность профессионального выгорания среди специалистов первичной медико-санитарной помощи в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода, а также выявить факторы, связанные с профессиональным выгоранием.

Методы

Авторы провели систематический поиск по девяти базам данных, собранных до февраля 2022 года, и выявили исследования о профессиональном выгорании среди специалистов первичной медико-санитарной помощи в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода. Языковых ограничений не было. Были включены обсервационные исследования. Два независимых эксперта провели скрининговое обследование, отбор исследований, извлечение данных и оценку качества. Для оценки общей распространенности профессионального выгорания использовался метаанализ случайных эффектов с помощью подшкал опросника выгорания Маслач для определения эмоционального истощения, деперсонализации и личных достижений. Авторы описательно сообщают о факторах, связанных с профессиональным выгоранием.

Результаты

В результате поиска обнаружено 1568 статей. После завершения отбора 60 исследований из 20 стран были включены в описательный анализ, а 31 – в метаанализ. Три исследования собрали данные во время пандемии коронавирусной инфекции 2019 года, но представили ограниченные данные о влиянии болезни на профессиональное выгорание. Общая распространенность профессионального выгорания колебалась от 2,5 до 87,9% (43 исследования). В метаанализе (31 исследование) общая распространенность высокого уровня эмоционального истощения составила 28,1% (95%-й ДИ: 21,5–33,5), высокий уровень деперсонализации составил 16,4% (95%-й ДИ: 10,1–22,9), а высокий уровень снижения личных достижений составил 31,9% (95%-й ДИ: 21,7–39,1).

Вывод

Значительная распространенность эмоционального выгорания среди специалистов первичной медико-санитарной помощи в странах с низким и средним уровнем дохода влияет на безопасность пациентов, качество медицинской помощи и планирование трудовых ресурсов. Необходимы дальнейшие поперечные исследования для поиска основанных на фактических данных решений, особенно в Африке и Юго-Восточной Азии.

Introduction

Burnout is defined as a form of chronic occupational stress consisting of three dimensions: (i) exhaustion; (ii) depersonalization or cynicism; and (iii) feelings of inefficacy.1 Although the burden of burnout in high-income countries is well established, less is known about low- and middle-income countries. Knowledge about burnout is important because of its substantial consequences.2–6 Among health-care professionals, burnout has been associated with patient safety concerns and poor quality of care.2 There is also an impact on physical and mental health and an increase in sick leave, staff turnover and emigration rates.3–7 Moreover, burnout can increase direct and indirect costs.6,8

Studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of burnout differs between countries and that it may be difficult to generalize research findings from high-income countries to low- and middle-income countries because of cultural differences that may affect factors associated with burnout and its prevalence.9,10 Additionally, the imbalance between job demands and the resources available underlies the etiology of burnout;11 this imbalance may differ substantially between low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries. Moreover, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic changed the health-care landscape in many countries and introduced additional stressors, such as staff redeployment and the fear of infection.12 The impact of the pandemic on the prevalence of burnout and the possibility that factors associated with the pandemic may differ across regions warrants investigation.

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified good primary health care as fundamental for achieving universal health coverage (UHC), a WHO strategic priority.13 UHC refers to the provision of universal, cost-effective health services that can be accessed without financial hardship.13 However, as observed, “health services are only as effective as the persons responsible for delivering them.”14 Thus, the physical and mental well-being of primary health-care professionals is crucial for achieving UHC. There is clear evidence from high-income countries that the prevalence of burnout in health-care professionals differs according to specialty and that the risk may be higher in primary care.15 Having a good estimate of the prevalence of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries is important because this information will provide the first step in identifying ways to mitigate the impact of burnout and to develop culturally and organizationally appropriate interventions.

The aims of this review, therefore, were: (i) to provide a comprehensive overview and meta-analysis of the prevalence of burnout among primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries; (ii) to explore factors associated with burnout in these countries; and (iii) to compare data on burnout collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and the pre-pandemic period.

Methods

When performing this review, we followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.16 We conducted an initial systematic search in nine electronic databases from database inception to 16 November 2020: (i) MEDLINE®; (ii) CINAHL; (iii) PsycInfo; (iv) APA PsycArticles®; (v) AMED; (vi) Embase®; (vii) Web of Science Core Collection; (viii) Global Index Medicus; and (ix) CNKI. Searches were updated on 11 February 2022. Reference lists were hand searched. Box 1 (available at: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/) presents the combination of search terms. The full search strategy conducted on MEDLINE® via EBSCOhost (EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, United States of America, is extensive; details are available from the data repository.17 There were no search limitations.

Box 1. Search term combinations used in the meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

primary health-care providers, such as (“general practi*”), (“family physician”), (“primary N2 care”), (“community health care”), (“community health work*”) and (“community N3 nurse”);

with terms for burnout, such as (“burnout”), (“compassion fatigue”), (“emotional exhaustion”), (disengage*), (“occupation* N3 stress*”) and (“work* N3 stress*); and

terms for low- and middle-income countries that included each country name along with additional terms such as (MH “Developing Countries”), (“middle income*” W0 (countr* OR nation OR nations OR econom*)), (“low* income” W0 (countr* OR nation OR nations OR econom*)), (“third world” W0 (countr* OR nation OR nations OR econom*)), (“less* developed” W0 (countr* OR nation OR nations OR econom*)), (Africa*), (West* W0 Asia*), ((South OR Southern) W0 Asia*), ((Latin OR Central OR South) W0 America*), ((Middle OR Far) W0 East) and (Caribbean* OR “West Indies*).

Study eligibility criteria are listed in Box 2 (available at: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/). We included studies in the meta-analysis if the Maslach Burnout Inventory was used as the measurement tool and prevalence estimates were reported for each of the following three subscales:19 (i) emotional exhaustion; (ii) depersonalization; and (iii) personal accomplishment. Low- and middle-income countries were defined by the World Bank’s 2020 income classification.18 We exported search results to Rayyan Intelligent Systematic Review (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, USA) for de-duplication and screening. One reviewer completed title screening and a second reviewer independently screened 10% of titles for comparability. Two reviewers independently completed abstract and full text screening; disagreements were resolved through discussion. We developed the protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis a priori and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020221336).20

Box 2. Study eligibility criteria, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

Inclusion criteria

Study design: cross-sectional or cohort study

Study setting: low- or middle-income country, as defined by the World Bank’s 2020 income classification18

Study population: primary health-care professionals working in community settings

Primary outcome of study: burnout prevalence as assessed using a validated burnout measurement tool or by self-report

Secondary outcome of study: factors associated with burnout

Exclusion criteria

Duplicates of publications or secondary research, such as narrative reviews or opinion pieces

Studies in high-income countries, as defined by the World Bank’s 2020 income classification18

Studies involving or including hospital-based secondary care professionals or specialists that report no separate data for primary care practitioners

Studies on medical students

Research on anxiety, depression or occupational stress that does not have a specific focus on burnout

Data extracted included: (i) study author; (ii) year of publication; (iii) country; (iv) region; (v) country income classification; (vi) study design; (vii) study participants; (viii) sampling method; (ix) sample size; (x) participants’ mean age; (xi) percentage of female participants; (xii) measurement tool; (xiii) prevalence of overall burnout; and (xiv) prevalence of burnout according to measurement tool subscales and to any associated factors. Two reviewers extracted data independently using a form developed and piloted for the study and at the same time performed a quality assessment using Hoy et al.’s risk-of-bias tool for prevalence studies,21 details available from the data repository.17 Disagreements were resolved through discussion. We translated non-English studies using Google Translate (Google LLC, Mountain View, USA).

Data analysis

Study characteristics, the burnout prevalence range and factors associated with burnout are reported narratively for all eligible studies. A random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis. We performed the analysis with MetaXL v. 5.3 (EpiGear International Pty Ltd) using the double arcsine transformation variant for the meta-analysis of prevalence.22 We calculated pooled prevalence estimates for each score category (i.e. high, moderate and low) in the three Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Standard values for the subscale score categories are listed in Table 1. Subgroup analyses were carried out for different professional groups. Study heterogeneity was assessed by inspecting forest plots and by calculating I2 – an I2 greater than 60% indicated a high degree of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using Doi plots and the LFK index.23

Table 1. Definitions of low, moderate and high Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale scores, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

| Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale | Subscale score, score category |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | |

| Emotional exhaustion | ≤ 16 | 17–26 | ≥ 27 |

| Depersonalization | ≤ 5 | 6–9 | ≥ 10 |

| Personal accomplishment | ≤ 33 | 34–39 | ≥ 40 |

Results

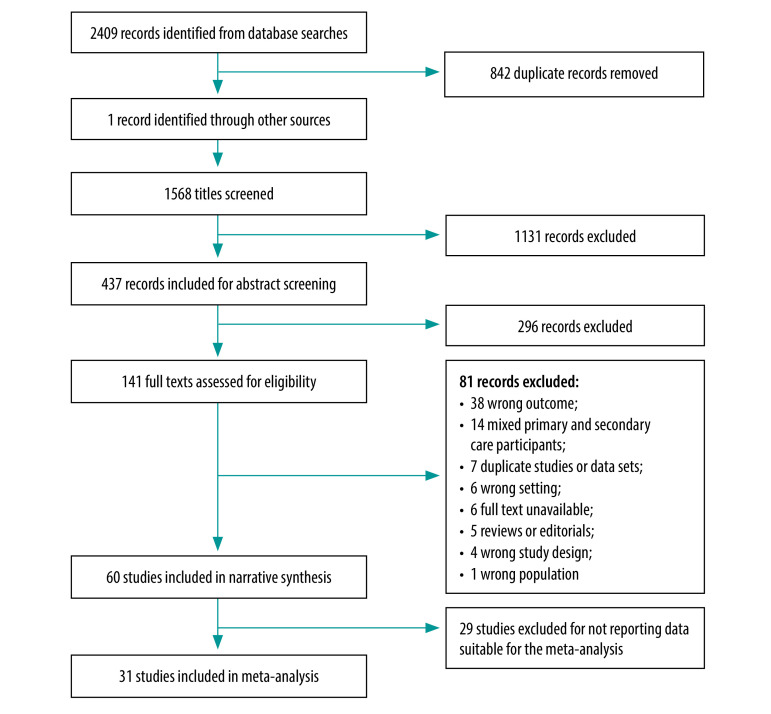

The literature searches generated a total of 1568 unique articles once duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). After screening, we included 60 studies in the narrative review and 31 studies in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Selection of studies, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022

Study characteristics

The 60 studies in the narrative review included a total of 61 089 primary health-care professionals from 20 low- and middle-income countries. The sample size ranged from 28 to 21 759. There were 61 different country data sets as one study included two countries: Bulgaria and Turkey.24 The greatest number of studies came from Brazil (18 studies),25–42 followed by China (10 studies),43–52 and Mexico (6 studies).53–58 Every WHO region was represented, with the greatest number of studies (25 studies) coming from the Region of the Americas. Box 3 (available at: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/) summarizes the geographical spread of studies.

Box 3. Data sets, by WHO region and country, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

Region of the Americas (25 studies)

18 studies from Brazil; six studies from Mexico; and one study from Cuba.

European Region (11 studies)a

Five studies from Turkey; two studies from Bosnia and Herzegovina; two studies from Serbia; one study from Bulgaria; and one study from the Russian Federation.

Western Pacific Region (10 studies)

10 studies from China.

Eastern Mediterranean Region (seven studies)

Four studies from the Islamic Republic of Iran; one study from Egypt; one study from Iraq; and one study from West Bank and Gaza Strip.

African Region (six studies)

Two studies from South Africa; one study from Cameroon; one study from Ethiopia; one study from Uganda; and one study from Zambia.

South-East Asia Region (two studies)

One study from India; and one study from Thailand.

WHO: World Health Organization.

a One study included data from Bulgaria and Turkey.

According to the World Bank’s 2020 income classification, most (54) data sets in this review were from upper-middle-income countries. Five were from lower-middle-income countries;59–63 two were from low-income countries.64,65 There were 20 non-English language studies: 11 Portuguese;26–30,32,33,36,37,39,40 eight Spanish;35,53–58,66 and one French.59 All Chinese publications that fulfilled our inclusion criteria were available in English. Overall, 54 studies reported participants according to gender and 31 reported their mean age, which ranged from 28 (standard deviation, SD: 2.59) to 47 (SD: 8.48) years. Table 2 (available at: https://www.who.int/publications/journals/bulletin/) lists the different types of health-care worker included in the studies.

Table 2. Study participant type, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

| Study participants | No. (%) of studies (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Family physicians | 20 (33.3) |

| Mixed primary health-care professionals | 18 (30.0) |

| Community nurses and nursing assistants | 12 (20.0) |

| CHWs | 6 (10.0) |

| Community pharmacists | 2 (3.3) |

| Community midwives | 1 (1.7) |

| Community oral health team members | 1 (1.7) |

CHW: community health worker.

The measurement tool used by 47 of the 60 studies was the Maslach Burnout Inventory. In the remaining 13 studies, the tool used was either: the Spanish Burnout Inventory;29,36,39 the Compassion Fatigue Questionnaire;67 the Professional Quality of Life scale;65 the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory;40 a short, validated questionnaire based on the Maslach Burnout Inventory;66 the Burnout Measure;68,69 the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory;63 the Burnout Characterization Scale;42 Emotional Burnout Diagnostics by Boyko V.V.;70 or a single-item scale.61 Only three studies reported collecting data during the COVID-19 pandemic:68–70 two were conducted in Turkey and used the Burnout Measure (short version);68,69 and one was conducted in the Russian Federation and used Emotional Burnout Diagnostics.70 One study included family medicine residents,68 one nurses,70 and one community pharmacists.69 Table 3 summarizes the studies’ characteristics.

Table 3. Study characteristics, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

| Study and year | Country | Type of participant | Burnout measurement tool | No. of participants | Mean age of participants, years | Proportion of female participants, % | Overall burnout prevalence, % | Prevalence of burnout by MBI subscale score category, (%)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal accomplishment | ||||||||

| Putnik 201171 | Serbia | Family physicians | MBI–General Survey | 373 | 47 | 84 | ND | High (48.3); moderate (34.0) | High (12.9); moderate (32.7) | High (5.1); moderate (16.9) |

| Mandengue 201759 | Cameroon | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 85 | ND | 48.2 | 42.4 | High (11.8); moderate (18.8) | High (10.6); moderate (31.8) | High (30.6); moderate (29.4) |

| López-León 200756 | Mexico | Family physicians | MBI | 131 | 46.4 (SD: 6.3) | 42 | 39.7 | High (26.0); moderate (22.1) | High (19.8); moderate (12.3) | High (8.4); moderate (14.5) |

| Lesić 200972 | Serbia | Family physicians | MBI | 38 | 42.2 (SD: 10.7) | 79.0 | ND | High (29.0); moderate (45.2) | High (11.1); moderate (27.8) | High (24.2); moderate (27.3) |

| Kotb 201460 | Egypt | Family physicians | MBI | 31 | ND | 80 | 41.94 | ND | ND | ND |

| Kosan 201973 | Turkey | Family physicians | MBI | 385 (139 in 2008 and 246 in 2012) | 2008: 30 (SD: 5.13); 2012: 34.05 (SD: 5.78) | 64.2 (48.9 in 2008 and 72.8 in 2012) | ND | 2008: high (0.7) and moderate (24.5); 2012: high (9.3) and moderate (21.5) | 2008: high (4.3) and moderate (18.0); 2012: high (4.5) and moderate (19.9) | 2008: high (76.3) and moderate (21.6); 2012: high (79.3) and moderate (17.4) |

| Gan 201945 | China | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 1015 | ND | ND | 35.0 (high on one MBI subscale); 21.0 (high on two subscales); 2.5 (high on three subscales) | High (24.83); moderate (23.25) | High (6.21); moderate (12.0) | High (33.99); moderate (20.0) |

| Charoentanyarak 202074 | Thailand | Family physician residents | MBI–Human Services Survey | 149 | 28.29 (SD: 2.59) | 67.1 | 10.7 | High (33.56); moderate (30.87) | High (14.09); moderate (27.52) | High (1.34); moderate (2.68) |

| Cetina-Tabares 200655 | Mexico | Family physicians | MBI | 93 | 44 | 46.2 | 20.5 (high on three subscales); 29.0 (moderate on three MBI subscales) | ND | ND | ND |

| Stanetić 201375 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 239 | ND | 83.3 | ND | High (46.0); moderate (28.9) | High (21.3); moderate (31.8) | High (22.2); moderate (34.7) |

| Soler 200824 | Bulgaria and Turkey | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 69 in Bulgaria and 112 in Turkey | ND | ND | ND | Bulgaria: high (62.3); Turkey: high (15.2) | Bulgaria: high (30.4); Turkey: high (15.2) | Bulgaria: high (18.8); Turkey: high (69.4) |

| Aranda 200453 | Mexico | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 163 | 47 | 36.2 | 42.3 | High (16.0); moderate (16.0) | High (1.8); moderate (5.5) | High (6.7); moderate (8.6) |

| Aranda-Beltrán 200554 | Mexico | Family physicians | MBI | 197 | ND | 37.1 | 41.8 | High (13.3); moderate (17.9) | High (2.0); moderate (6.6) | High (6.6); moderate (7.7) |

| Al Dabbagh 201976 | Iraq | Family physicians | MBI | 134 | ND | 64.8 | 30.6 (high); 50.0 (moderate) | High (68.7); moderate (11.9) | High (26.1); moderate (28.4) | High (41.1); moderate (26.1) |

| Ahmadpanah 201577 | Iran (Islamic Republic of) | Family physicians | MBI | 100 | 32.90 (SD: 5.06) | 29 | ND | High (15.4) | High (14.5) | High (10.2) |

| Aguilera 201057 | Mexico | Family physicians | MBI–Human Services Survey | 233 | 44.4 (SD: 7.18) | 40.3 | 41.6 | High (31.7) | High (15.0) | High (15.9) |

| Račić 201967 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Family physicians | Compassion fatigue questionnaire | 120 | ND | 80 | 75 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Rossouw 201378 | South Africa | Family physicians | MBI | 132 | ND | ND | ND | High (53) | High (64) | High (43) |

| Çevik 202168b | Turkey | Family medicine residents | Burnout Measure (short version) | 477 | Median: 28 (range: 24–54) | 61.2 | 25.8 (moderate); 24.1 (severe); 23.3 (very severe) | ND | ND | ND |

| Zhang 202152 | China | Family physicians | MBI–General Survey (Chinese version) | 2 693 | 44.64 (SD: 7.25) | 35.6 | 65.2 | High (30.1); moderate (24.2) | High (22.2); moderate (11.7) | High (48.3); moderate (13.3) |

| Engelbrecht 200879 | South Africa | Community nurses | MBI | 542 | ND | ND | ND | High (68.7); moderate (30.9) | High (85.1); moderate (12.9) | High (8.3); moderate (91.0) |

| Hu 201544 | China | Community nurses | MBI | 420 | ND | 100 | 86.2 | ND | ND | ND |

| Alshawish 202062 | West Bank and Gaza Strip | Community nurses and midwives | MBI | 207 | ND | 91.3 | 10.6 | High (36.7); moderate (17.9) | High (14.0); moderate (20.8) | High (17.9); moderate (19.3) |

| Merces 201732 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI–Human Services Survey | 60 | 39.55 (SD: 10.38) | 95 | 58.3 (high on at least one MBI subscale); 16.7 (high on all three subscales) | High (18.3); moderate (43.3) | High (48.3); moderate (41.7) | High (56.6); moderate (41.7) |

| Merces 201630 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI | 28 | 39.1 (SD: 9.6) | 100 | 7.1 | High (28.6); moderate (39.3) | High (21.5); moderate (32.1) | High (46.4); moderate (50.0) |

| Barbosa Ramos 201937 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI | 52 | ND | 100 | ND | High (15.4); moderate (34.6) | High (13.5); moderate (34.6) | High (23.1); moderate (21.2) |

| Merces 201631 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI | 189 | ND | 96.8 | 10.6 | High (20.6); moderate (40.7) | High (31.7); moderate (39.2) | High (48.1); moderate (49.2) |

| Lorenz 201834 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI | 168 | ND | 88.4 | ND | High (28.0); moderate (37.5) | High (32.1); moderate (33.9) | High (38.7); moderate (33.3) |

| Holmes 201426 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI | 45 | ND | 100 | 11.1 | High (53.3); moderate (20.0) | High (11.1); moderate (28.9) | High (11.1); moderate (48.9) |

| Merces 202038 | Brazil | Community nurses | MBI–Human Services Survey | 1125 | 37.1 (SD: 9.6) | 87.9 | 18.3 | High (28.1); moderate (41.1) | High (44.5); moderate (35.9) | High (60.2); moderate (36.2) |

| Garcia 202142 | Brazil | Community nurses | Burnout characterization scale | 122 | 45.2 (SD: 9.8) | 94.3 | ND | High (27.9); moderate (37.7) | High (25.4); moderate (41.8)c | High (25.4); moderate (47.5)d |

| Seluch 202170b | Russian Federation | Community nurses | Emotional Burnout Diagnostics by Boyko V.V. | 60 | 40.86 | 100 | 50 | ND | ND | ND |

| Silveira 201429 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | CESQT | 217 | ND | 88.9 | 18 (profile 1); 11 (profile 2) | ND | ND | ND |

| da Silva 200825 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 141 | 38.9 (SD: 11.4) | 92.2 | 24.1 | Moderate or high (70.9) | Moderate or high (34.0) | Moderate or high (47.5) |

| Selamu 201964 | Ethiopia | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI–Human Services Survey | 136 | ND | 61 | 3.8 (at baseline); 4.6 (at 6-month follow-up) | High (7.7 at baseline; 7.5 at 6-month follow-up) | ND | High (43.7 at baseline; 48.5 at 6-month follow-up) |

| Hernández 200366 | Cuba | Mixed primary health-care professionals | Short questionnaire of burnout | 144 | ND | 77.1 | 43.8 (doctors); 27.3 (nurses) | ND | ND | ND |

| Ran 202047 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI–General Survey | 1 279 | ND | 66.5 | 18.69 | ND | ND | ND |

| Pinheiro 202039 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | CESQT | 344 | 40 (SD: 9.7) | 88.7 | 14.4 (profile 1); 44.5 (profile 2) | ND | ND | ND |

| Mao 202048 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 663 | ND | 44.5 | ND | High (24.1); moderate (14.6) | High (15.7); moderate (7.4) | High (34.7); moderate (15.8) |

| Lima 201833 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI–Human Services Survey | 153 | 45 (SD: 9.78) | 82.4 | 51 | ND | ND | ND |

| Li 201946 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI–Human Services Survey | 951 | ND | 65.1 | ND | High (33.1); moderate (32.9) | High (8.8); moderate (19.8) | High (41.43); moderate (20.5) |

| Kruse 200961 | Zambia | Mixed primary health-care professionals | Single-item scale | 483 | 37 (IQR: 31–45) | 87 | 51.2 | ND | ND | ND |

| Hernández-Vargas 200958 | Mexico | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 276 | ND | ND | ND | High (34.8); moderate (30.1) | High (35.1); moderate (19.6) | High (36.2) Moderate (30.4) |

| Xu 202049 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 15 627 | ND | 66.2 | 3.3 (high); 47.6 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Wang 202043 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 1 148 | ND | 64.72 | ND | High (27.66) | High (6.06) | High (38.74) |

| Tomaz 202040 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | Oldenburg Burnout Inventory | 94 | 40.9 (SD: 9.6) | 84 | 38.3 | High (21.3) | ND | ND |

| de Souza Filho 201936 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | CESQT | 248 | 40.75 (SD: 9.66) | 91.1 | 24.2 (profile 1); 8.5 (profile 2) | ND | ND | ND |

| da Silva 202141 | Brazil | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 2 940 | 36.7 (SD: 9.6) | 90.5 | 11.4 (severe) | High (39.7); moderate (24.9) | High (11.8); moderate (24.5) | High (18.3); moderate (27.2) |

| Lu 202050 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI | 21 759 | 35 | 70.0 | 50.1 (total); 3.0 (severe); 47.1 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Yan 202151 | China | Mixed primary health-care professionals | MBI (Chinese version) | 1 214 | 40.26 (SD: 8.61) | 55 | 11.3 (severe); 37.6 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Malakouti 201180 | Iran, (Islamic Republic of) | CHWs | MBI | 212 | 35.1 (SD: 7.2) | 70.1 | 1.1 (high); 16.6 (moderate) | High (12.3); moderate (15.1) | High (5.3); moderate (8.0) | High (43.7); moderate (19.0) |

| Mota 201428 | Brazil | CHWs | MBI | 222 | ND | 87.8 | 29.3 | Moderate or high (57.7) | Moderate or high (51.8) | Moderate or high (59.0) |

| Martins 201427 | Brazil | CHWs | MBI | 107 | ND | ND | 41.6 | High (20.6); moderate (52.3) | High (21.1); moderate (50.0) | High (20.6); moderate (55.4) |

| Bijari 201681 | Iran (Islamic Republic of) | CHWs | MBI | 423 | 39 (SD: 8.4) | 57.9 | 5.7 (high on all three MBI subscales); 28.8 (high on either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization subscale) | High (17.7); moderate (13.7) | High (6.4); moderate (10.4) | High (53.0); moderate (18.2) |

| Amiri 201682 | Iran (Islamic Republic of) | CHWs | MBI | 548 | 35.8 (SD: 7.5) | 71 | 5.5 (high); 52.7 (moderate) | High (17.3); moderate (18.4) | High (8.8); moderate (10.0) | High (33.9); moderate (15.7) |

| Pulagam 202163 | India | CHWs | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | 150 | ND | 100 | Personal burnout: 8.0 (high) and 30 (moderate); work burnout: 8.7 (high) and 24.7 (moderate); client burnout: 6.7 (high) and 23.3 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Muliira 201665 | Uganda | Midwives | Professional Quality of Life scale | 224 | 34 (SD: 6.3) | 79.5 | 10.3 (high); 87.9 (moderate) | ND | ND | ND |

| Maciel 201835 | Brazil | Community oral health team members | MBI–Human Services Survey | 50 | ND | 72 | ND | High (26); moderate (32) | High (16); moderate (26) | High (10); moderate (26) |

| Calgan 201183 | Turkey | Community pharmacists | MBI | 251 | 42.06 (SD: 11.19) | 58.6 | ND | High (1.2); moderate (27.1) | High (0.8); moderate (13.9) | High (71.3) Moderate (24.7) |

| Okuyan 202169b | Turkey | Community pharmacists | Burnout Measure (short version) | 1 098 | 41 | 64.8 | 31.5 | ND | ND | ND |

CESQT: Spanish Burnout Inventory (Cuestionario para la Evaluación del Síndrome de Quemarse por el Trabajo); CHW: community health worker; IQR: interquartile range; MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory; ND: not determined; SD: standard deviation.

a Definitions of low, moderate and high score categories for the Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment are listed in Table 1.

b This study reported collecting data during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic.

c Dehumanization was assessed instead of depersonalization.

d Disappointment was assessed instead of personal accomplishment.

Burnout prevalence

A single-point prevalence for overall burnout was reported by 43 studies, which used a range of different measurement tools and different definitions of burnout. Estimates ranged from 2.5% for severe burnout among family physicians in China to 87.9% for burnout among midwives in Uganda.45,65 In the three studies that collected data during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence ranged from 31.5% in community pharmacists to 47.4% in family medicine residents (for severe or very severe burnout) to 50.0% in primary care nurses.68–70

Of 47 studies that reported burnout prevalence determined using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, 31 (involving 14 439 primary health-care professionals) contributed data suitable for the meta-analysis. The risk of bias was assessed as low for 18 of these studies and moderate for 13. No study had a high risk of bias. Of the two studies in the meta-analysis that were published during the pandemic, one collected data before the COVID-19 pandemic and one did not report dates for data collection. Table 4 shows the pooled prevalence of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment across the 31 studies. The pooled prevalence was 28.1% for a high level of emotional exhaustion, 27.6% for a moderate level of emotional exhaustion, 16.4% for a high level of depersonalization, 22.7% for a moderate level of depersonalization, 31.9% for a high level of reduced personal accomplishment and 28.1% for a moderate level of reduced personal accomplishment. The combined estimated prevalence of a moderate or high level on each subscale was 55.7% for emotional exhaustion, 39.1% for depersonalization and 60.0% for reduced personal accomplishment. The I2 for these studies was 98% for the emotional exhaustion subscale and 99% for the depersonalization and personal accomplishment subscales, which indicate a high degree of heterogeneity. Forest plots for high scores on each subscale are available from the data repository.17

Table 4. Prevalence of burnout by Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale score category, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022.

| Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale score categorya | Pooled prevalence, % (95% CI)b |

|---|---|

|

Emotional exhaustion

| |

| High |

28.1 (21.5–33.5) |

| Moderate |

27.6 (21.1–33.0) |

| Low |

44.3 (36.6–49.9) |

|

Depersonalization

| |

| High |

16.4 (10.1–22.9) |

| Moderate |

22.7 (15.2–29.7) |

| Low |

60.9 (50.5–67.6) |

|

Personal accomplishment

| |

| High |

31.9 (21.7–39.1) |

| Moderate |

28.1 (18.5–35.3) |

| Low | 39.9 (28.7–47.0) |

CI: confidence interval.

a Definitions of low, moderate and high Maslach Burnout Inventory score categories are listed in Table 1.

b Prevalence was pooled across 31 studies.

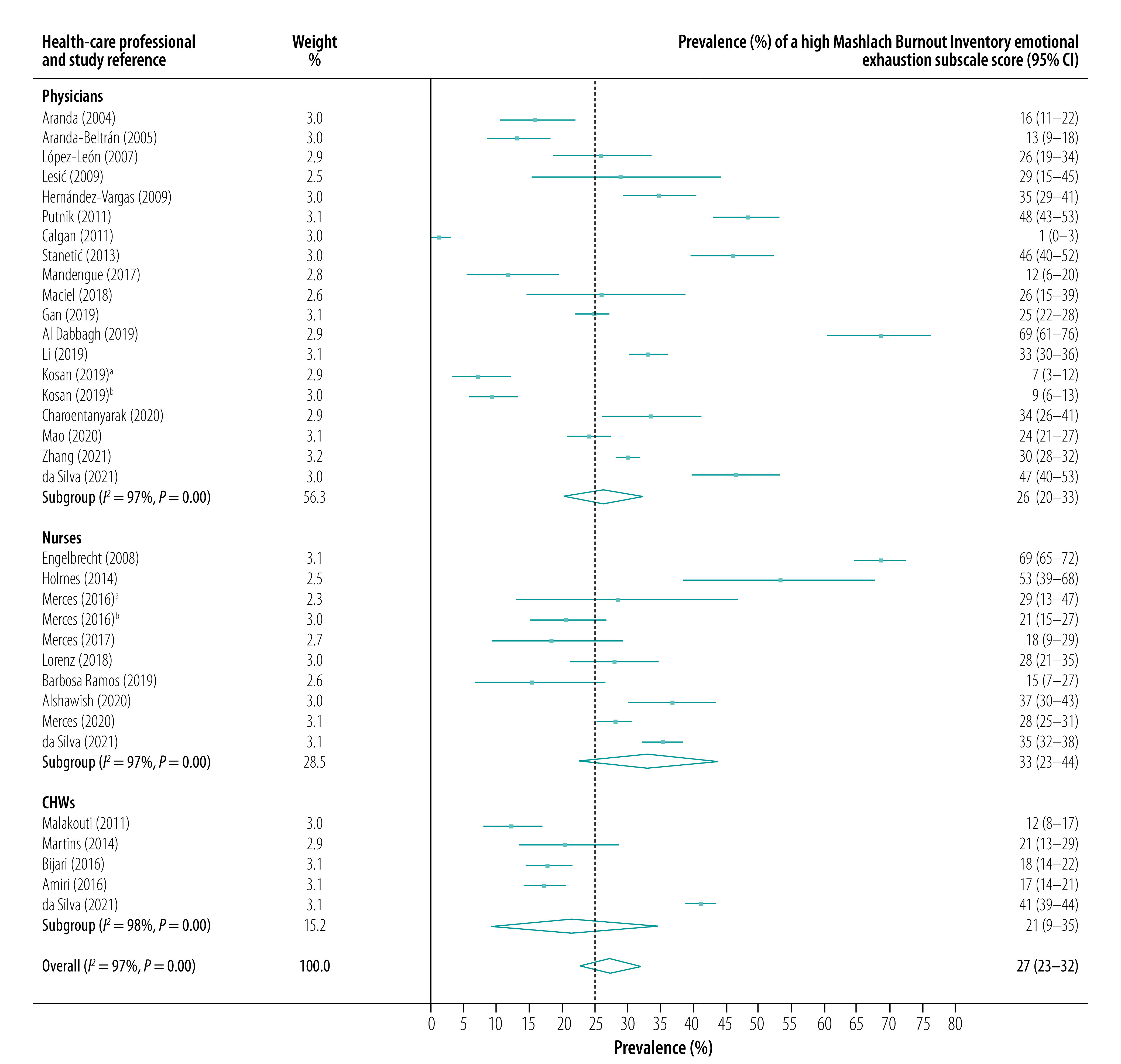

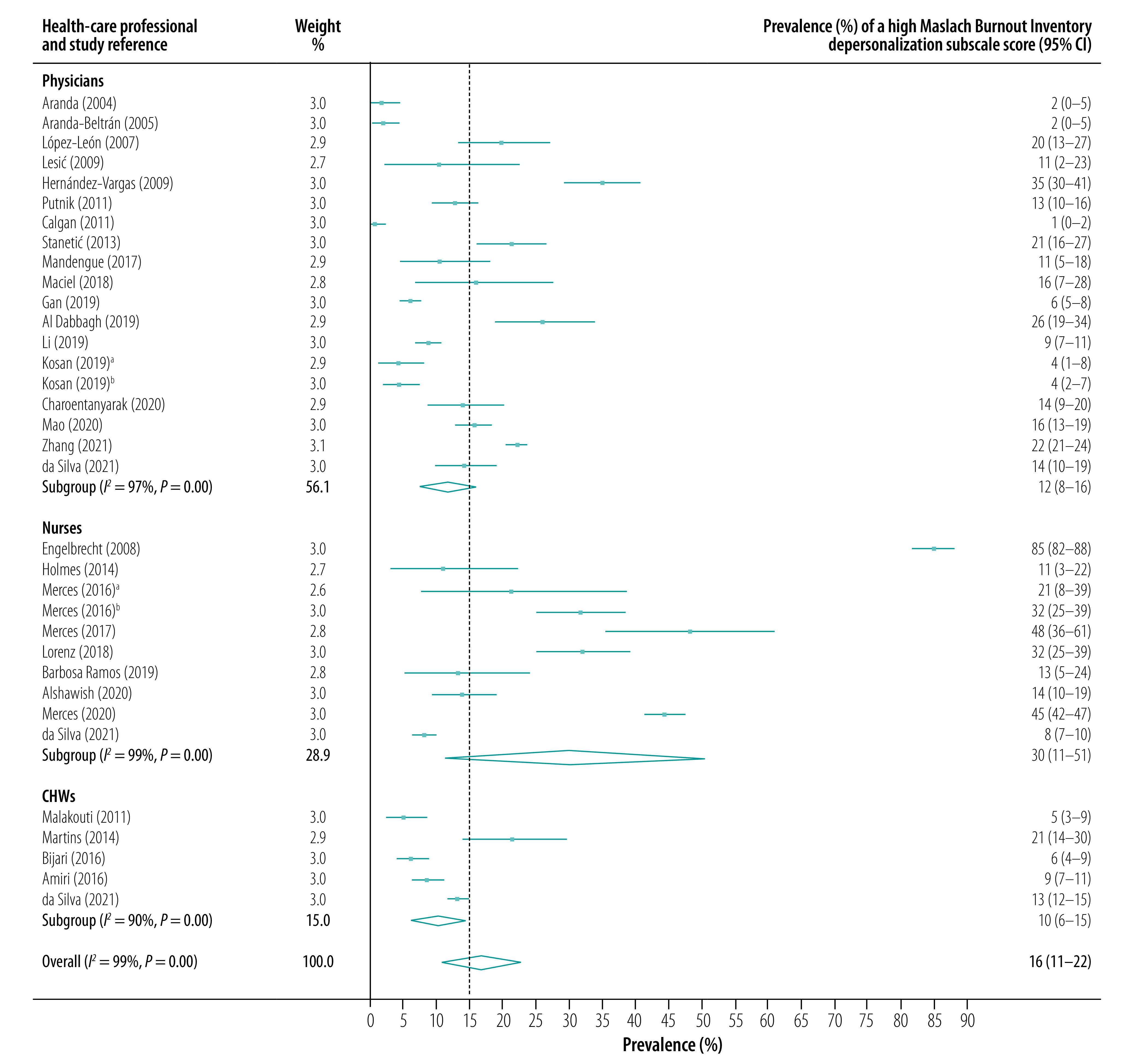

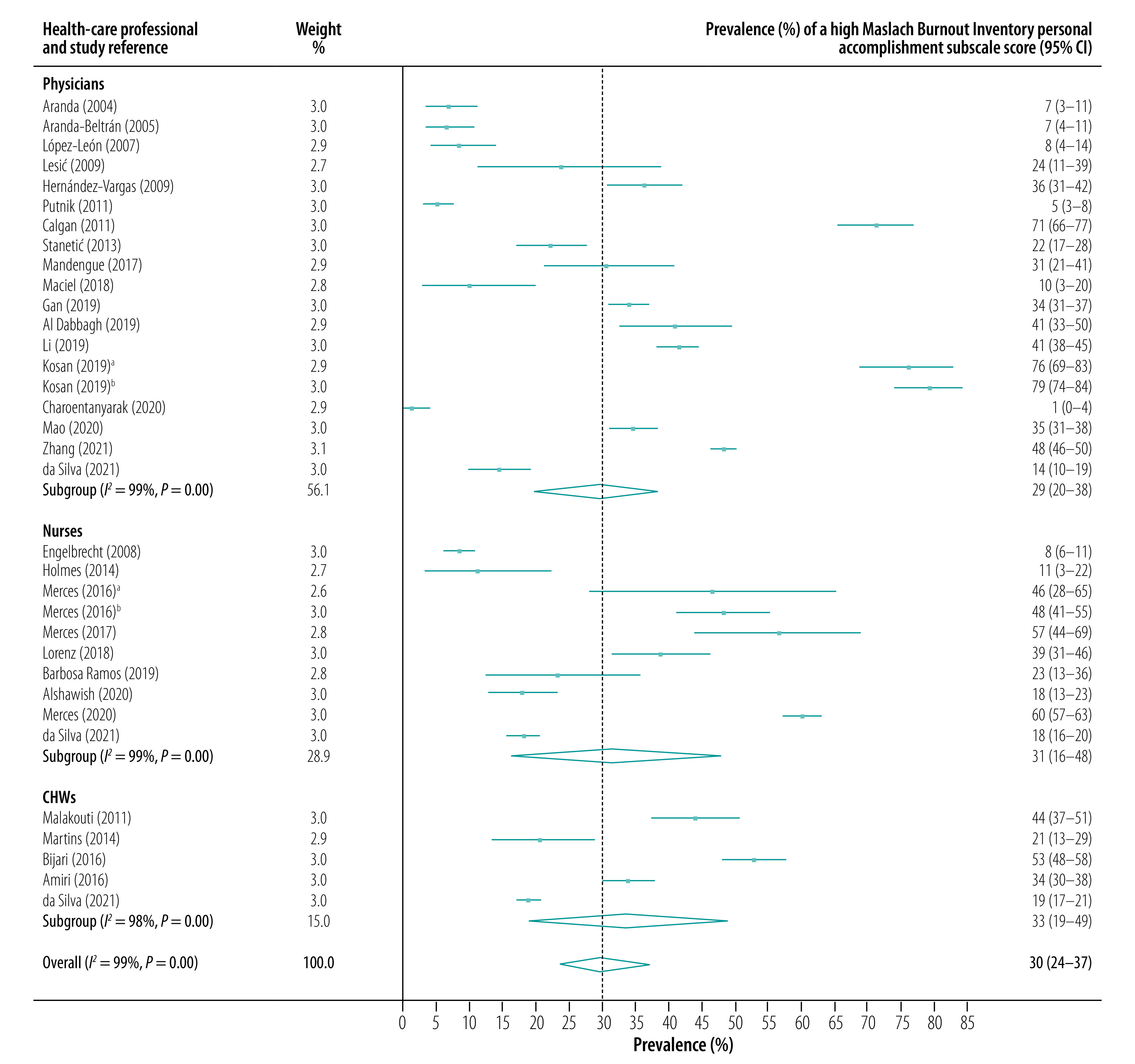

The subgroup analysis showed that high scores for emotional exhaustion were most prevalent in community nurses (pooled prevalence: 33.1%; 95% CI: 22.7–44.0), followed by family physicians (pooled prevalence: 26.1%; 95% CI: 20.3–32.5) and community health workers (CHWs, pooled prevalence: 21.3%; 95% CI: 9.3–34.8). Depersonalization was also most prevalent among community nurses (pooled prevalence for a high score: 30.0%; 95% CI: 11.3–50.7), followed by family physicians (pooled prevalence: 11.5%; 95% CI: 7.8–16.0) and CHWs (pooled prevalence: 10.0%; 95% CI: 6.3–14.5). In contrast, reduced personal accomplishment was most prevalent in CHWs (pooled prevalence for a high score: 33.5%; 95% CI: 19.2–48.7), followed by nurses (pooled prevalence: 31.3%; 95% CI: 16.1–47.8) and family physicians (pooled prevalence: 28.7%; 95% CI: 19.7–38.4). Forest plots for the prevalence of high scores on the three Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales are presented in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of a high Maslach Burnout Inventory emotional exhaustion subscale score, by health-care professional type and study, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022

CHWs: community health workers; CI: confidence interval.

Notes: A high Maslach Burnout Inventory emotional exhaustion subscale score is defined in Table 1. For the Kosan 2019 study, data are represented separately for 2008 (Kosan 2019a) and 2012 (Kosan 2019b). The Merces 2016a study refers to the paper by Merces M, Carneiro e Cordeiro T, et al. 2016.30 The Merces 2016b study refers to the paper by Merces M, Silva D, et al. 2016.31

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of a high Maslach Burnout Inventory depersonalization subscale score, by health-care professional type and study, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022

CHWs: community health workers; CI: confidence interval.

Notes: A high Maslach Burnout Inventory depersonalization subscale score is defined in Table 1. For the Kosan 2019 study, data are represented separately for 2008 (Kosan 2019a) and 2012 (Kosan 2019b). The Merces 2016a study refers to the paper by Merces M, Carneiro e Cordeiro T, et al. 2016.30 The Merces 2016b study refers to the paper by Merces M, Silva D, et al. 2016.31

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of a high Maslach Burnout Inventory personal accomplishment subscale score, by health-care professional type and study, meta-analysis of burnout in primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries up to 2022

CHWs: community health workers; CI: confidence interval.

Notes: A high Maslach Burnout Inventory personal accomplishment subscale score is defined in Table 1. A high score indicates reduced personal accomplishment. For the Kosan 2019 study, data are represented separately for 2008 (Kosan 2019a) and 2012 (Kosan 2019b). The Merces 2016a study refers to the paper by Merces M, Carneiro e Cordeiro T, et al. 2016.30 The Merces 2016b study refers to the paper by Merces M, Silva D, et al. 2016.31

Factors associated with burnout

Demographic factors, such as sex, age, marital status and educational level, were associated with burnout in our review. Nine studies found a higher prevalence of burnout in women,38,40,57,61,64,68,69,71,82 six found a higher prevalence in men,24,27,46,48–50 and three found no significant sex difference.45,56,60 Burnout, specifically emotional exhaustion, was negatively associated with age in 10 studies,24,27,41,49,50,60,61,69,73,76 whereas four studies found a positive association.64,75,81,82 Burnout was positively associated with marriage in four studies,40,44,60,65 and with having children in four studies.40,57,59,81 In contrast, there was a positive association with unmarried status in eight studies,45,49,50,53,54,68,76,83 and with not having children in two.29,68 A high educational level was associated with burnout in eight studies.44,46,48–50,53,54,81

A heavy workload (including overtime, shift work and a high patient load) and having a second job were significantly associated with a high prevalence of burnout,24,29,37,38,46,48–50,53,56,57,59–61,63,67,78,79,83 as were exposure to violence and conflict at work.38,44,45,56,59,74,79 Other work-related factors included working in a rural or economically deprived setting,27,38,41,64,67 insufficient resources,38,56,79,82 COVID-19 exposure,68 inadequate personal protective equipment,68 a poor level of support,46,48,58 job insecurity,58,63,64 specific job tasks,65 and inadequate rest breaks or vacation time.38,73 Eleven studies found a positive association between burnout and years of service,29,38,41,44,48,54,57,63,75,80,81, whereas five found a negative association.33,62,69,78,83 The work-related consequences of burnout included a lack of job satisfaction,24,33,45,55 and an intention to change jobs.24,34,43,47 Burnout was also significantly associated with physical or psychological illness,27,62,65,67,76,81 smoking,24,38,76 a lack of exercise,38,60 and the distance travelled to work.59 The distance travelled to work and being asked to complete work tasks beyond the individual’s expertise were associated factors only in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Protective factors identified included exercise, rest breaks and vacation time.38,60,73

Quality assessment and publication bias

The risk of bias was calculated for each study: 46.7% of studies (28/60) scored between 5 and 7 points, which indicated a moderate risk of bias, and 53.3% (32/60) scored between 8 and 10 points, which indicated a low risk of bias. Studies scored well in domains relating to internal validity but less well in domains related to external validity, such as representative sampling frames and sampling methods.

The Doi plot for a high depersonalization subscale score was symmetrical, with a low LFK index (0.03), which suggests a low risk of publication bias. However, the Doi plots for a high emotional exhaustion subscale score and a high personal accomplishment subscale score demonstrated minor asymmetry, with an LFK index of –1.08 and –1.11, respectively, which suggests a small risk of publication bias. Full details of the risk of bias assessment are available from the data repository.17

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the prevalence of burnout among primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries is substantial, perhaps unsurprisingly in view of the workforce and resource shortages in these countries.14,84 However, given that the consequences of burnout include increased sick leave, staff turnover and emigration, there are implications for workforce planning and the recruitment and retention of primary health-care professionals in countries where understaffing is already a critical issue. Any increased desire to emigrate could exacerbate the so-called brain drain from these countries to high-income countries.8 Policy-makers in low- and middle-income countries may need to work with policy-makers in high-income countries to identify solutions.

We found that the prevalence of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization was highest among primary care nurses, whereas the prevalence of reduced personal accomplishment was highest among CHWs. The high prevalence of burnout among nurses may affect patient safety as they are the main providers of community health care in some low- and middle-income countries. Longitudinal studies are needed to identify causal factors and to determine ways of reducing work demands on primary care nurses. One solution may be to increase the number of family physicians to provide professional support and clinical expertise. However, burnout is also common among family physicians and, therefore, any restructuring of roles and responsibilities must bear this in mind. Although international studies suggest that overall burnout levels among family physicians are similar in low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries, there are differences in the prevalence of each dimension of burnout for different cadres. For example, the prevalence of depersonalization is lower among primary care nurses in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income countries.85,86 This result may reflect differences in the responsibilities, workload and type of work expected of primary care nurses in low- and middle-income countries, where they are often responsible for diagnosis, treatment and performing basic procedures.87 Additionally, in contrast to observations in high-income countries,24 studies in our review suggest that reduced personal accomplishment is the most prevalent dimension of burnout for family physicians and CHWs in low- and middle-income countries. These results may reflect limited opportunities for further education, professional development and career progression in these countries. Policy-makers need to be aware of these differences, to work actively to identify individuals most at risk of burnout and to develop targeted interventions.

We were unable to compare findings from the three studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic with pooled pre-pandemic data because different measurement tools were used. However, the estimated overall prevalence of burnout in two of these studies was higher than the pooled prevalence we found for the individual Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales,69,70 which is in line with the findings of a global survey of health-care professionals that used a single-item scale to assess burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic and found a prevalence of 51%.88 Additionally, we found no clear difference in burnout prevalence between upper-middle-income countries and lower-middle-income and low-income countries. Again, this result was partly due to differences in the definition of burnout and in the measurement tools used, which made comparisons difficult.

In line with previous research,89 we found conflicting evidence on the association between burnout and sex. This outcome may have been due to: differences in how men and women experience burnout;89 cultural differences in sex roles;71 or cultural and sex differences in the importance of protective factors such as social support.90,91 Our findings suggest that burnout is more common in younger age groups. Younger professionals early in their careers may have greater family responsibilities, which could lead to increased conflict between work and home life and which, combined with lower professional self-efficacy, could result in a higher risk of burnout.92 In contrast to studies from high-income countries,93 11 studies in our review found that the prevalence of burnout also increased with the number of years of service; it may be that limited opportunities for career development in low- and middle-income countries lead to frustration and burnout over the years. Our findings imply that burnout prevalence peaks in health workers both at an early career stage and much later in their careers. Consequently, policies and interventions to mitigate and prevent burnout should be targeted at these two career stages.

The evidence from our review confirms, as previously established,93 that burnout is associated with heavy workloads, few workplace resources, insufficient workplace support and conflict at work. One study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that increased exposure to COVID-19 patients and the requirement to supply one’s own personal protective equipment were both positively associated with burnout.68 Another highlighted the need for specific pandemic training and increased organizational resources and support.69 These results are in line with findings from high-income countries, which highlight the increased workload and stress associated with exposure to COVID-19 patients, the need for extra training and support, and the importance of adequate personal protective equipment.12,88 Several studies in our review identified factors that protected against burnout, such as regular exercise, regular rest breaks and time away from work,38,60,73 which could be incorporated into the culture of primary care.

The geographical spread of studies in our review highlights the dearth of research on primary care burnout in low- and middle-income countries, specifically in Africa and South-East Asia, which are the WHO regions with the greatest shortages of health-care professionals.84 Moreover, most studies were performed in upper-middle-income countries, which limits the generalizability of our results to lower-resource settings. This finding highlights the urgent need for research in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Importantly, 43% of studies in our review were published from 2019 onwards, possibly reflecting increasing awareness that a healthy primary care workforce is essential for achieving UHC.13

Study heterogeneity was high due to the breadth of primary health-care professionals included, the geographical spread of the studies and the variety of burnout measurement tools used. The variety of cultures, economies, disease burdens and political, educational and health systems in study countries would have resulted in differences in workload, resource availability and training, which may have contributed to large variations in the working environment and personal coping strategies between countries. However, the quality of the studies was good as no study was assessed as having a high risk of bias.

We conducted this study using a robust systematic review method and preregistered the study protocol on the PROSPERO website which ensured transparency. However, searches were limited to electronic databases and reference lists. Grey literature was not searched, which means that some data may have been missed, although the risk was small.94 Another limitation was the use of Google Translate rather than translators, which may have introduced errors at the data extraction stage. However, a recent study suggested that Google Translate is adequate for data extraction.95 One third of the studies retrieved by our searches and fulfilling our inclusion criteria were in languages other than English. Of the 25 studies from the Americas, 19 were not published in English. Excluding these studies would have excluded a considerable amount of regional data.

The findings of this review suggest that over half of primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries have a moderate or high level of emotional exhaustion or reduced personal accomplishment and over a third have a moderate or high level of depersonalization. These results have implications for the health of the primary care workforce, staffing levels and the quality of care. It is necessary to identify protective factors against burnout, such as workplace support, continuing education and regular rest breaks, and to incorporate them into primary care. Further research should be conducted to provide better estimates of the prevalence of burnout and to explore its determinants, especially in underrepresented countries in Africa and South-East Asia, where workforce shortages are greatest. Additionally, this review highlighted the difficulty of making comparisons across regions, countries and professional groups when different measurement tools and definitions of burnout are used. There is, therefore, a need for an international consensus on a definition of burnout and on outcome measures to enable comparisons within burnout research.

Funding:

This work was funded by a matched Wellcome Trust-funded Keele University doctoral studentship awarded to TW. FM was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) doctoral fellowship (NIHR300957).

Competing interests:

CM and TH have received funding from the NIHR. Keele School of Medicine has received funding from Bristol Myers Squibb to support a non-pharmacological atrial fibrillation screening trial. TH is also working on the Novavax and Valneva COVID-19 vaccine trials.

References

- 1.Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/ [cited 2021 May 10].

- 2.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017. Apr;32(4):475–82. 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, González AD, Gabani FL, Andrade SM. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2017. Oct 4;12(10):e0185781. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toppinen-Tanner S, Ojajärvi A, Väänänen A, Kalimo R, Jäppinen P. Burnout as a predictor of medically certified sick-leave absences and their diagnosed causes. Behav Med. 2005. Spring;31(1):18–32. 10.3200/BMED.31.1.18-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019. Jan;17(1):36–41. 10.1370/afm.2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye LN, Awad KM, Fiscus LC, Sinsky CA, Shanafelt TD. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019. Oct 15;171(8):600–1. 10.7326/L19-0522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anduaga-Beramendi A, Beas R, Maticorena-Quevedo J, Mayta-Tristán P. Association between burnout and intention to emigrate in Peruvian health-care workers. Saf Health Work. 2019. Mar;10(1):80–6. 10.1016/j.shaw.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirigia JM, Gbary AR, Muthuri LK, Nyoni J, Seddoh A. The cost of health professionals’ brain drain in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006. Jul 17;6(1):89. 10.1186/1472-6963-6-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S. Burnout and doctors: prevalence, prevention and intervention. Healthcare (Basel). 2016. Jun 30;4(3):37. 10.3390/healthcare4030037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malach Pines A. Occupational burnout: a cross-cultural Israeli Jewish–Arab perspective and its implications for career counselling. Career Dev Int. 2003. Apr;8(2):97–106. 10.1108/13620430310465516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The Job Demands–Resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol. 2007. Jan 1;22(3):309–28. 10.1108/02683940710733115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly EL, Cunningham A, Sifri R, Pando O, Smith K, Arenson C. Burnout and commitment to primary care: lessons from the early impacts of COVID-19 on the workplace stress of primary care practice teams. Ann Fam Med. 2022. Jan-Feb;20(1):57–62. 10.1370/afm.2775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Universal health coverage (UHC). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) [cited 2021 May 10].

- 14.Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Guerra Arias M, Leone C, et al. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, Brazil, 10–13 November 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GHWA_AUniversalTruthReport.pdf [cited 2021 May 10].

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work–life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012. Oct 8;172(18):1377–85. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welcome to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) website! [internet]. Available from: http://prisma-statement.org/ [cited 2022 Apr 21].

- 17.Wright T, Mughal F, Helliwell T, Babatunde OO, Dikomitis L, Mallen CD, et al. Prevalence and determinants of burnout in primary health care professionals in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Supplementary files [data repository]. London: Figshare; 2021. 10.6084/m9.figshare.19410932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.World Bank country and lending groups – country classification [internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2020. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [cited 2021 May 10].

- 19.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright T, Mughal F, Helliwell T, Babatunde OO, Dikomitis L, Mallen CD. A systematic review of the prevalence and determinants of burnout in primary healthcare workers in low- and middle-income countries. York: PROSPERO; 2021. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020221336http://[2021 May 10].

- 21.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012. Sep;65(9):934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013. Nov 1;67(11):974–8. 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuya-Kanamori L, Barendregt JJ, Doi SAR. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. Int J Evid-Based Healthc. 2018. Dec;16(4):195–203. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, Dobbs F, Asenova RS, Katic M, et al. ; European General Practice Research Network Burnout Study Group. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract. 2008. Aug;25(4):245–65. 10.1093/fampra/cmn038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Silva ATC, Menezes PR. Burnout syndrome and common mental disorders among community-based health agents. Rev Saude Publica. 2008. Oct;42(5):921–9. Portuguese. 10.1590/S0034-89102008000500019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes E, dos Santos S, Farias J, de Sousa Costa M. Síndrome de burnout em enfermeiros na atenção básica: repercussão na qualidade de vida. Rev Pesquisa Cuidado Fundam. 2014;6(4):1384–95. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins LF, Laport TJ, Menezes VP, Medeiros PB, Ronzani TM. Esgotamento entre profissionais da atenção primária à saúde. Cien Saude Colet. 2014. Dec;19(12):4739–50. Portuguese. 10.1590/1413-812320141912.03202013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mota CM, Dosea GS, Nunes PS. Avaliação da presença da síndrome de burnout em agentes comunitários de saúde no município de Aracaju, Sergipe, Brasil. Cien Saude Colet. 2014. Dec;19(12):4719–26. Portuguese. 10.1590/1413-812320141912.02512013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silveira S, Câmara S, Amazarray M. [Preditores da síndrome de burnout em profissionais da saúde na atenção básica de Porto Alegre/RS]. Cad Saude Colet. 2014;22(4):386–92. Portuguese. 10.1590/1414-462X201400040012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merces MC das, Carneiro e Cordeiro TMS, Santana AIC, Lua I, Silva DDS, Alves MS, et al. [Síndrome de burnout em trabalhadores de enfermagem da atenção básica à saúde]. Rev Baiana Enferm. 2016;30(3):1–9. Portuguese. 10.18471/rbe.v30i3.15645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merces MC das, Silva D, Lua I, Oliveira D, de Souza M, D’Oliveira Júnior A. Burnout syndrome and abdominal adiposity among primary health care nursing professionals. Psicol Reflex Crit. 2016;29(1):44. 10.1186/s41155-016-0051-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merces MC das, Lopes RA, Silva DS, Oliveira DS, Lua I, Mattos AIS, et al. Prevalência da síndrome de burnout em profissionais de enfermagem da atenção básica à saúde. Rev Pesquisa Cuidado Fundam Online. 2017;9(1):208–14. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lima A, Farah B, Bustamante-Teixeira M. Análise da prevalência da síndrome de burnout em profissionais da atenção primária em saúde. Trab Educ Saúde. 2018;16(1):283–304. Portuguese. 10.1590/1981-7746-sol00099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenz VR, Sabino MO, Corrêa Filho HR. Professional exhaustion, quality and intentions among family health nurses. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71 suppl 5:2295–301. 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maciel J, de Farias M, Sampaio J, Guerrero J, Castro-Silva I. Satisfacción profesional y prevalencia del síndrome de burnout en equipos de salud bucal de atención primaria en el municipio Sobral, Ceará-Brasil. Salud Trab (Maracay). 2018;26(1):34–44. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Souza Filho P, Campani F, Câmara S. Contexto laboral e burnout entre trabalhadores da saúde da atenção básica: o papel mediador do bem-estar social. Quaderns Psicol [internet]. 2019;21(1):e1475. Portuguese. 10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbosa Ramos C, Alves Farias J, De Sousa Costa M, Tavares da Fonseca L. Impactos da síndrome de burnout na qualidade de vida dos profissionais de enfermagem da atenção básica à saúde. Rev Bras Cien Saude. 2019;23(3):285–96. Portuguese. 10.22478/ufpb.2317-6032.2019v23n3.43595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Merces MC das, Coelho JMF, Lua I, Silva DSE, Gomes AMT, Erdmann AL, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout syndrome among primary health care nursing professionals: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. Jan 11;17(2):474. 10.3390/ijerph17020474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinheiro JP, Sbicigo JB, Remor E. Associação da empatia e do estresse ocupacional com o burnout em profissionais da atenção primária à saúde. Cien Saude Colet. 2020. Sep;25(9):3635–46. Portuguese. 10.1590/1413-81232020259.30672018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomaz H, Tajra F, Lima A, Santos M. Síndrome de burnout e fatores associados em profissionais da Estratégia Saúde da Família. Interface (Botucatu). 2020;24 suppl 1:e190634. Portuguese. 10.1590/interface.190634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Silva ATC, de Souza Lopes C, Susser E, Coutinho LMS, Germani ACCG, Menezes PR. Burnout among primary health care workers in Brazil: results of a multilevel analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021. Nov;94(8):1863–75. 10.1007/s00420-021-01709-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia GPA, Marziale MHP. Satisfaction, stress and burnout of nurse managers and care nurses in primary health care. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2021. Apr 16;55:e03675. 10.1590/s1980-220x2019021503675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H, Jin Y, Wang D, Zhao S, Sang X, Yuan B. Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among primary care providers in rural China: results from structural equation modeling. BMC Fam Pract. 2020. Jan 15;21(1):12. 10.1186/s12875-020-1083-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu HX, Liu LT, Zhao FJ, Yao YY, Gao YX, Wang GR. Factors related to job burnout among community nurses in Changchun, China. J Nurs Res. 2015. Sep;23(3):172–80. 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Yang Y, Wang C, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of burnout and associated factors among general practitioners in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019. Dec 2;19(1):1607. 10.1186/s12889-019-7755-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Yuan B, Meng Q, Kawachi I. Contextual factors associated with burnout among Chinese primary care providers: a multilevel analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019. Sep 23;16(19):3555. 10.3390/ijerph16193555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ran L, Chen X, Peng S, Zheng F, Tan X, Duan R. Job burnout and turnover intention among Chinese primary healthcare staff: the mediating effect of satisfaction. BMJ Open. 2020. Oct 7;10(10):e036702. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao Y, Fu H, Feng Z, Feng D, Chen X, Yang J, et al. Could the connectedness of primary health care workers involved in social networks affect their job burnout? A cross-sectional study in six counties, central China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020. Jun 18;20(1):557. 10.1186/s12913-020-05426-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu W, Pan Z, Li Z, Lu S, Zhang L. Job burnout among primary healthcare workers in rural China: a multilevel analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. Jan 22;17(3):727. 10.3390/ijerph17030727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu S, Zhang L, Klazinga N, Kringos D. More public health service providers are experiencing job burnout than clinical care providers in primary care facilities in China. Hum Resour Health. 2020. Dec 3;18(1):95. 10.1186/s12960-020-00538-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan H, Sang L, Liu H, Li C, Wang Z, Chen R, et al. Mediation role of perceived social support and burnout on financial satisfaction and turnover intention in primary care providers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021. Mar 19;21(1):252. 10.1186/s12913-021-06270-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, Bai X, Bian L, Wang M. The influence of personality, alexithymia and work engagement on burnout among village doctors in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021. Aug 4;21(1):1507. 10.1186/s12889-021-11544-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aranda C, Pando M, Aranda M, Guadalupe Salazar J, Torres T. Síndrome de burnout y apoyo social en los médicos familiares de base del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS) Guadalajara, México. Rev Psiquiatr Fac Med Barc. 2004;31(4):142–150. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aranda-Beltrán C, Pando-Moreno M, Torres-López T, Salazar-Estrada O, Franco-Chávez S. Factores psicosociales y síndrome de burnout en médicos de familia. México. An Fac Med (Lima). 2005;66(3):225. Spanish. 10.15381/anales.v66i3.1346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cetina-Tabares RE, Chan-Canul AG, Sandoval-Jurado L. Nivel de satisfacción laboral y síndrome de desgaste profesional en médicos familiars. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2006. Nov-Dec;44(6):535–40. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.López-León E, Rodríguez-Moctezuma JR, López-Carmona JM, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Munguía-Miranda C. Desgaste profesional en médicos familiares y su asociación con factores sociodemográficos y laborales. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2007. Jan-Feb;45(1):13–9. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aguilera E, de Alba García J. Prevalencia del síndrome de agotamiento profesional (burnout) en médicos familiares mexicanos: análisis de factores de riesgo. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2010;39(1):67–84. Spanish. 10.1016/S0034-7450(14)60237-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernández-Vargas C, Garcia A, Galicia F, Bannack E. Factores psicosociales predictores de burnout en trabajadores del sector salud en atención primaria. Cienc Trab. 2009;34:227–31. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mandengue SH, Owona Manga LJ, Lobè-Tanga MY, Assomo-Ndemba PB, Nsongan-Bahebege S, Bika-Lélé C, et al. Syndrome de burnout chez les médecins généralistes de la région de Douala (Cameroun): les activités physiques peuvent-elles être un facteur protecteur? Rev Med Brux. 2017;38(1):10–5. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kotb AA, Mohamed KA, Kamel MH, Ismail MAR, Abdulmajeed AA. Comparison of burnout pattern between hospital physicians and family physicians working in Suez Canal University Hospitals. Pan Afr Med J. 2014. Jun 19;18(2):164. 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.164.3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kruse GR, Chapula BT, Ikeda S, Nkhoma M, Quiterio N, Pankratz D, et al. Burnout and use of HIV services among health care workers in Lusaka District, Zambia: a cross-sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2009. Jul 13;7(1):55. 10.1186/1478-4491-7-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alshawish E, Nairat E. Burnout and psychological distress among nurses working in primary health care clinics in West Bank–Palestine. Int J Ment Health. 2020;49(4):321–35. 10.1080/00207411.2020.1752064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pulagam P, Satyanarayana PT. Stress, anxiety, work-related burnout among primary health care worker: a community based cross sectional study in Kolar. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021. May;10(5):1845–51. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2059_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Selamu M, Hanlon C, Medhin G, Thornicroft G, Fekadu A. Burnout among primary healthcare workers during implementation of integrated mental healthcare in rural Ethiopia: a cohort study. Hum Resour Health. 2019. Jul 18;17(1):58. 10.1186/s12960-019-0383-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muliira RS, Ssendikadiwa VB. Professional quality of life and associated factors among Ugandan midwives working in Mubende and Mityana rural districts. Matern Child Health J. 2016. Mar;20(3):567–76. 10.1007/s10995-015-1855-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hernández JJR. Estrés y burnout en profesionales de la salud de los niveles primario y secundario de atención. Rev Cuba Salud Pública. 2003;29(2):103–10. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Račić M, Virijević A, Ivković N, Joksimović BN, Joksimović VR, Mijovic B. Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among family physicians in the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2019. Dec;25(4):630–7. 10.1080/10803548.2018.1440044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Çevik H, Ungan M. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and residency training of family medicine residents: findings from a nationwide cross-sectional survey in Turkey. BMC Fam Pract. 2021. Nov 15;22(1):226. 10.1186/s12875-021-01576-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okuyan B, Bektay MY, Kingir ZB, Save D, Sancar M. Community pharmacy cognitive services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study of practices, precautions taken, perceived enablers and barriers and burnout. Int J Clin Pract. 2021. Dec;75(12):e14834. 10.1111/ijcp.14834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seluch M, Volchansky M, Safronov R. Dependence of emotional burnout on personality typology in the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2021;70(3):713–21. 10.3233/WOR-210428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Putnik K, Houkes I. Work related characteristics, work-home and home-work interference and burnout among primary healthcare physicians: a gender perspective in a Serbian context. BMC Public Health. 2011. Sep 23;11(1):716. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lesić ARA, Petrović-Stefanovic N, Perunicić I, Milenković P, Lecić Tosevski D, Bumbasirević MZ. Burnout in Belgrade orthopaedic surgeons and general practitioners, a preliminary report. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2009;56(2):53–9. 10.2298/ACI0902053L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kosan Z, Aras A, Cayir Y, Calikoglu EO. Burnout among family physicians in Turkey: a comparison of two different primary care systems. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019. Aug;22(8):1063–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Charoentanyarak A, Anothaisintawee T, Kanhasing R, Poonpetcharat P. Prevalence of burnout and associated factors among family medicine residency in Thailand. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020. Jul 28;7:1–8. 10.1177/2382120520944920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stanetić K, Tesanović G. Influence of age and length of service on the level of stress and burnout syndrome. Med Pregl. 2013. Mar-Apr;66(3-4):153–62. 10.2298/MPNS1304153S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Al Dabbagh A, Hayyawi A, Kochi M. Burnout syndrome among physicians working in primary health care centers in Baghdad, Al-Rusafa Directorate, Iraq. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10(7):502–7. 10.5958/0976-5506.2019.01620.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ahmadpanah M, Torabian S, Dastore K, Jahangard L, Haghighi M. Association of occupational burnout and type of personality in Iranian general practitioners. Work. 2015. Jun 5;51(2):315–9. 10.3233/WOR-141903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rossouw L, Seedat S, Emsley R, Suliman S, Hagemeister D. The prevalence of burnout and depression in medical doctors working in the Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality community healthcare clinics and district hospitals of the Provincial Government of the Western Cape: a cross-sectional study. S Afr Fam Pract. 2013;55(6):567–73. 10.1080/20786204.2013.10874418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Engelbrecht M, Bester C, Van Den Berg H, Van Rensburg H. A study of predictors and levels of burnout: the case of professional nurses in primary health care facilities in the Free State. S Afr J Econ. 2008;76:S15–27. 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2008.00164.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malakouti SK, Nojomi M, Salehi M, Bijari B. Job stress and burnout syndrome in a sample of rural health workers, behvarzes, in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2011. Spring;6(2):70–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bijari B, Abassi A. Prevalence of burnout syndrome and associated factors among rural health workers (behvarzes) in south Khorasan. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016. Jul 9;18(10):e25390. 10.5812/ircmj.25390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amiri M, Khosravi A, Eghtesadi AR, Sadeghi Z, Abedi G, Ranjbar M, et al. Burnout and its influencing factors among primary health care providers in the north east of Iran. PLoS One. 2016. Dec 8;11(12):e0167648. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Calgan Z, Aslan D, Yegenoglu S. Community pharmacists’ burnout levels and related factors: an example from Turkey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011. Feb;33(1):92–100. 10.1007/s11096-010-9461-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511131 [cited 2021 May 10].

- 85.Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019. Mar 18;12:169–77. 10.2147/PRBM.S195633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]