Key Points

Question

What is the distribution of responder rates to the oral, small-molecule, calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist atogepant for preventing migraine?

Findings

In a secondary analysis of a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of 902 adults with migraine, all doses of atogepant significantly increased the proportion of participants who achieved a 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% reduction in mean monthly migraine-days during 12 weeks of treatment. The atogepant and placebo groups reported similar rates of treatment-emergent adverse effects.

Meaning

Atogepant appears to be effective and well tolerated for the preventive treatment of migraine as measured by 4 levels of the clinically meaningful end point of responder rates.

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial of adults with migraine examines the rates of response to treatment with atogepant.

Abstract

Importance

Some patients with migraine, particularly those in primary care, require effective, well-tolerated, migraine-specific oral preventive treatments.

Objective

To examine the efficacy of atogepant, an oral, small-molecule, calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist, using 4 levels of mean monthly migraine-day (MMD) responder rates.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine from December 14, 2018, to June 19, 2020, in adults with 4 to 14 migraine-days per month at 128 sites in the US.

Interventions

Patients were administered 10 mg of atogepant (n = 222), 30 mg of atogepant (n = 230), 60 mg of atogepant (n = 235), or placebo (n = 223) once daily in a 1:1:1:1 ratio for 12 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

These analyses evaluated treatment responder rates, defined as participants achieving 50% or greater (α-controlled, secondary end point) and 25% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% (prespecified additional end points) reductions in mean MMDs during the 12-week blinded treatment period.

Results

Of 902 participants (mean [SD] age, 41.6 [12.3] years; 801 [88.8%] female; 752 [83.4%] White; 825 [91.5%] non-Hispanic), 873 were included in the modified intention-to-treat population (placebo, 214; 10 mg of atogepant, 214; 30 mg of atogepant, 223; and 60 mg of atogepant, 222). For the secondary end point, a 50% or greater reduction in the 12-week mean of MMDs was achieved by 119 of 214 participants (55.6%) treated with 10 mg of atogepant (odds ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 2.1-4.6), 131 of 223 participants (58.7%) treated with 30 mg atogepant (odds ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 2.4-5.3), 135 of 222 participants (60.8%) treated with 60 mg of atogepant (odds ratio, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.6-5.7), and 62 of 214 participants (29.0%) given placebo (P < .001). The numbers of participants who reported a 25% or greater reduction in the 12-week mean of MMDs were 157 of 214 (73.4%) for 10 mg of atogepant, 172 of 223 (77.1%) for 30 mg of atogepant, and 180 of 222 (81.1%) for 60 mg of atogepant vs 126 of 214 (58.9%) for placebo (P < .002). The numbers of participants who reported a 75% or greater reduction in mean MMDs were 65 of 214 (30.4%) for 10 mg of atogepant, 66 of 223 (29.6%) for 30 mg of atogepant, and 84 of 222 (37.8%) for 60 mg of atogepant compared with 23 of 214 (10.7%) for placebo (P < .001). The numbers of participants reporting 100% reduction in mean MMDs were 17 of 214 (7.9%) for 10 mg of atogepant (P = .004), 11 of 223 (4.9%) for 30 mg of atogepant (P = .02), and 17 of 222 (7.7%) for 60 mg of atogepant (P = .003) compared with 2 of 214 (0.9%) for placebo.

Conclusions and Relevance

At all doses, atogepant was effective during the 12-week double-blind treatment period beginning in the first 4 weeks, as evidenced by significant reductions in mean MMDs at every responder threshold level. Higher atogepant doses appeared to produce the greatest responder rates, which can guide clinicians in individualizing starting doses.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03777059

Introduction

Migraine is a disabling chronic disease characterized by recurrent headache attacks and associated symptoms, including nausea, phonophobia, and photophobia.1,2 Most migraine care for adults takes place in primary care (eg, internal and family medicine).3,4 In an analysis of patients with migraine receiving medical care on a large US health plan, 77% were treated in primary care.5 Recent reviews and position statements3,4 conclude that improving migraine outcomes should focus on primary care.

Preventive medications, a key migraine treatment modality, are intended to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks.6 Approved preventive migraine treatments in the US include 6 daily oral medications from 3 pharmacologic classes (β-blockers, antiepileptic drugs, small-molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide [CGRP] receptor blockers or gepants), as well as injectable CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies and onabotulinumtoxinA.6,7,8 Several oral agents (eg, antidepressants and angiotensin receptor blockers) are used off label for migraine prevention.6 As many as 75% of patients with migraine using oral preventive agents discontinued their use during the first 6 months, with that number increasing at 1 year.9 Discontinuation is largely attributed to poor efficacy or tolerability.10 Although CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies are specifically designed for migraine and have favorable efficacy and tolerability profiles, many patients prefer oral therapies to injections.6,11 Therefore, effective and well-tolerated migraine-specific oral preventive treatments are needed, particularly in primary care, where most people seek migraine treatment.3,4

Atogepant is an oral, small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonist (gepant) recently approved for preventive migraine treatment.12 Atogepant has been evaluated in a phase 2b/3 study13 and the phase 3 ADVANCE (12-Week Placebo-controlled Study of Atogepant for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine in Participants With Episodic Migraine) trial,14 in which once-daily oral administration demonstrated efficacy for migraine prevention by significantly reducing mean monthly migraine-days (MMDs) vs placebo. A key secondary, α-controlled end point in ADVANCE was the proportion of participants achieving a 50% or greater reduction in 3-month mean of MMDs vs placebo. Responder rates are often primary or secondary end points and are regarded as more clinically meaningful than changes in MMDs.15,16 In addition, guidelines recommend exploring multiple responder rate thresholds.15 Monthly migraine-days reflect group mean changes, including individuals with a large response and nonresponders, which generates means that may be difficult to apply to individuals. Responder rates reflect the proportion of individuals achieving a relief threshold, an outcome readily communicated in clinical practice. The course of treatment effects is equally important when setting treatment expectations.

We report the α-controlled, secondary end point of 50% or greater responder rate as well as 25% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% responder rates (prespecified additional end points) in the 3-month mean of MMDs and by 4-week treatment intervals (weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12) for 10, 30, and 60 mg of atogepant vs placebo, consistent with current guidelines.15 These data more fully characterize the benefits of atogepant as a preventive migraine treatment and have meaningful applications to real-world practice, providing clinicians and patients with easier ways to communicate results that consider individual differences in response.17

Methods

Trial Design

This study is a secondary analysis of ADVANCE, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 clinical trial conducted at 128 US sites from December 14, 2018, to June 19, 2020.14 Participants were randomized (1:1:1:1) to 10, 30, or 60 mg of atogepant or placebo administered orally once daily for 12 weeks. A 4-week screening of baseline eDiary data was followed by 12 weeks of treatment and 4 weeks of safety follow-up. The numbers of migraine-days during the baseline period (ie, day –28 to –1) were evaluated. Atogepant tablets and matching placebo were provided in identical blister cards to maintain blinding. Participants were instructed to take study treatment once daily at approximately the same time. The first dose of study treatment was taken at the clinic. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from the International Classification on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines. The protocol (Supplement 1) and all relevant documents were submitted to and approved by a Central Institutional Review Board (Advarra, Inc) and individual study site review boards before study initiation. Participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Participants

Eligible participants were adults (18-80 years of age) with a 1-year or longer history of migraine with or without aura diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3),2 migraine onset before 50 years of age, and a mean of 4 to 14 migraine-days per month during the 3 months before visit 1 and the 28-day baseline eDiary period. Exclusion criteria included a current diagnosis of chronic migraine, new daily persistent headache, cluster headache, or painful cranial neuropathy as defined by the ICHD-32 and a mean of 15 or more headache-days per month across 3 months before visit 1 or during the baseline period. A headache day was defined as a calendar day with headache pain lasting 2 hours or longer unless a medication was immediately used, in which case no minimum duration was specified. Other exclusion criteria were inadequate response to more than 4 medications (2 with different mechanisms of action) prescribed for migraine prevention and use of opioids or barbiturates for more than 2 days per month, triptans or ergots for 10 days or more per month, or simple analgesics (eg, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or acetaminophen) for 15 days or more per month in the 3 months before visit 1 or during the 28-day baseline period. Barbiturate use was excluded 30 days before screening and throughout the trial. Short-term migraine treatments (eg, triptans, ergots, opioids, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiemetics) were permitted. Participants reported their race and ethnicity, which was captured using prespecified coding on case report forms. Race and ethnicity data were collected to gain a better understanding of the populations that were evaluated in this study and because of the potential to conduct subgroup analyses to further evaluate potentially undertreated populations.

Outcome Measures

The primary end point in ADVANCE was change from baseline in MMDs across the 12-week treatment period as previously reported.14 This report focuses on 50% or greater (α-controlled, secondary end point) and 25% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% (prespecified additional end points) reductions in the 12-week mean MMDs. A 100% reduction in MMDs represented individuals who reported no migraine-days from the day the participant received the first dose of treatment (day 1) through the end of week 12. A migraine-day was defined as any calendar day (midnight until 11:59 pm [23:59]) when a headache occurred that met protocol-defined criteria. A day 1 migraine may have included a substantial portion of the day before taking the first dose of study intervention. Therefore, a prespecified sensitivity analysis removed those with a day 1 migraine-day before receiving the first dose of study drug by eliminating day 1 but retained the 28-day period.

Additional prespecified exploratory end points included 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% reductions in MMDs during weeks 1 to 4, 5 to 8, and 9 to 12. A prespecified cumulative distribution function summarized the proportion of participants in each treatment group achieving particular levels of percent reduction in mean MMDs. Additional prespecified responder analyses included the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C; much better or very much better) at week 12 and satisfaction with study medication (satisfied or extremely satisfied) at weeks 4, 8, and 12. Efficacy assessments were based on a participant-rated eDiary used daily at home to collect data on headache duration, characteristics, symptoms, and short-term medication use, which collectively defined migraine- and headache-days.

Adverse events were reported by participants throughout the trial. The most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events (≥5% of participants in any group) are reported. Safety parameters included clinical laboratory evaluations, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy analyses used the modified intention-to-treat population, which consisted of randomized participants who received 1 dose or more of treatment, had an evaluable baseline period of eDiary data, and had 1 or more evaluable postbaseline 4-week periods (weeks 1-4, 5-8, and 9-12) of eDiary data. For analysis purposes, a month was defined as each 4-week treatment interval (28 days). For monthly data, baseline MMDs were calculated during the 28-day baseline period before treatment initiation. An evaluable baseline period was defined as participants having 20 days or more of completed eDiary days during a single month. For participants with less than 28 days of baseline data, the number of headache-days was prorated to a 28-day equivalent. An evaluable postbaseline period was defined as participants having 14 days or more of completed eDiary days (prorated to 28-day equivalent). After treatment initiation, months with 14 days or more of completed eDiary data were prorated to 28-day equivalents. Months with less than 14 days of data were considered missing and addressed in the generalized linear mixed-model (GLMM) analysis under the assumption that data were missing at random. All analyses were prespecified; however, only the 50% or greater responder rate outcome was α controlled. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the 50% or greater responders across the 12-week treatment period. The model included terms for treatment group, prior effective migraine preventive medication exposure, and baseline MMDs. The treatment difference (odds ratio [OR]) between each atogepant dose group and placebo was estimated and tested. A multivariate logistic regression model using the same covariates analyzed the 25% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% responders across the treatment period and PGI-C responders at week 12. A GLMM for repeated measures was used to analyze the 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% responder rates during each 4-week interval. The model included treatment group, prior exposure to an effective migraine prevention medication, baseline MMDs, visit, and treatment group × visit interaction. Individuals were treated as a random effect, and the within-subject repeated binary responses were modeled using an unstructured covariance matrix. The same GLMM model was used to analyze treatment satisfaction responders at weeks 4, 8, and 12. The overall type I error rate for multiple comparisons across atogepant doses for the secondary efficacy end point in this analysis was controlled at the 0.05 level using a graphical approach with weighted Bonferroni test procedure.18 This approach does not require any assumptions about the correlations among the various end points and is transparent in terms of α propagation. The other efficacy analyses were performed at the nominal significance level, without adjusting for multiplicity. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be nominally statistically significant for exploratory analyses. The GLMM was used to handle missing data on the assumption that they are missing at random. The Supplementary Appendix of the primary publication14 contains additional details about the statistical methods.

Results

Participants

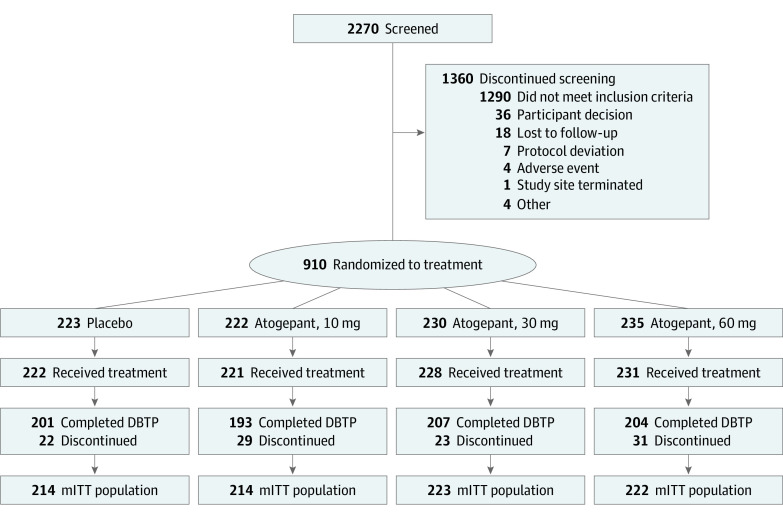

Of 910 participants randomized, 902 (mean [SD] age, 41.6 [12.3] years; 801 [88.8%] female and 101 [11.2%] male; 124 [13.7%] African American or Black, 3 [0.3%] Alaska Native or American Indian, 12 [1.3%] Asian, 752 [83.4%] White, 1 [0.1%] with missing race, and 10 [1.1%] of multiple races; 77 [8.5%] Hispanic and 825 [91.5%] non-Hispanic) took 1 dose or more of the study medications and were included in the safety population (Table). Baseline mean (SD) MMDs were 7.5 (2.5) in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 7.9 (2.3) in the 30 mg of atogepant group, 7.8 (2.3) in the 60 mg of atogepant group, and 7.5 (2.4) in the placebo group. The modified intention-to-treat population included 873 participants (placebo, 214; 10 mg of atogepant, 214; 30 mg of atogepant, 223; and 60 mg of atogepant, 222) (Figure 1). Across all groups, 805 of the 910 participants (88.5%) completed the 12-week double-blind treatment period.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of the Overall Safety Population.

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 222) | Daily atogepant dose | Total (N = 902) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg (n = 221) | 30 mg (n = 228) | 60 mg (n = 231) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.3 (12.8) | 41.4 (12.1) | 42.1 (11.7) | 42.5 (12.4) | 41.6 (12.3) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 198 (89.2) | 200 (90.5) | 204 (89.5) | 199 (86.1) | 801 (88.8) |

| Male | 24 (10.8) | 21 (9.5) | 24 (10.5) | 32 (13.9) | 101 (11.2) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||||

| African American/Black | 24 (10.8) | 34 (15.4) | 38 (16.7) | 28 (12.1) | 124 (13.7) |

| Alaska Native or American Indian | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) |

| Asian | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (3.0) | 12 (1.3) |

| White | 194 (87.4) | 181 (81.9) | 185 (81.1) | 192 (83.1) | 752 (83.4) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Multiplea | 2 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) | 10 (1.1) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| Hispanic | 23 (10.4) | 21 (9.5) | 19 (8.3) | 14 (6.1) | 77 (8.5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 199 (89.6) | 200 (90.5) | 209 (91.7) | 217 (93.9) | 825 (91.5) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 30.8 (8.7) | 30.4 (7.6) | 31.2 (7.6) | 29.9 (7.3) | 30.6 (7.8) |

| MMDs, mean (SD), No.b | 7.5 (2.4) [214] | 7.5 (2.5) [214] | 7.9 (2.3) [223] | 7.8 (2.3) [222] | 7.6 (2.4) [873] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MMD, monthly migraine-day.

Participants who reported multiple races are only included in the multiple category.

Migraine-day is defined as any day meeting criteria A, B, and C or D and E: A, headache with at least 2 of the following characteristics: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate to severe pain, and/or aggravated by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity; B, at least 1 of the following: nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia, and/or typical aura accompanying or within 60 minutes of headache; C, headache lasting at least 2 hours unless an acute, migraine-specific medication was used; D, headache fulfilling 1 criterion from A and at least 1 criteria from B or at least 2 from A and no criteria from B; and E, headache lasting at least 2 hours unless an acute, migraine-specific medication was used.

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through the Trial.

DBTP indicates double-blind treatment period; mITT, modified intention-to-treat.

12-Week Mean Responder Rates

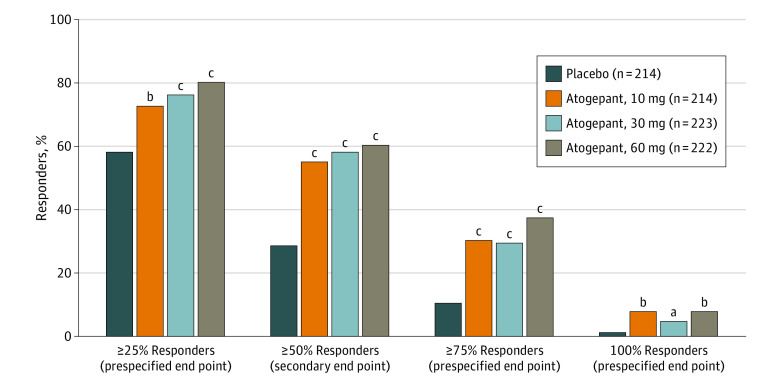

For the α-controlled secondary end point, atogepant treatment resulted in a 50% or greater reduction in the 12-week mean MMDs in 119 of 214 participants (55.6%) in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 131 of 223 participants (58.7%) in the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 135 of 222 participants (60.8%) in the 60 mg of atogepant group compared with 62 of 214 participants (29.0%) receiving placebo (P < .001) (Figure 2). The ORs for achieving a 50% or greater reduction in MMDs for atogepant vs placebo were 3.1 (95% CI, 2.1-4.6) for the 10 mg of atogepant group, 3.5 (95% CI, 2.4-5.3) for the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 3.8 (95% CI, 2.6-5.7) for the 60 mg of atogepant group. The numbers of participants reporting a 25% or greater reduction in the 12-week mean MMDs were 157 of 214 (73.4%) for 10 mg of atogepant, 172 of 223 (77.1%) for 30 mg of atogepant, and 180 of 222 (81.1%) for 60 mg of atogepant vs 126 of 214 (58.9%) for placebo (P < .002) (Figure 2). The numbers of participants who reported a 75% or greater reduction in mean MMDs were 65 of 214 (30.4%) in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 66 of 223 (29.6%) in the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 84 of 222 (37.8%) in the 60 mg of atogepant group compared with 23 of 214 (10.7%) in the placebo group (P < .001) (Figure 2). The numbers of participants reporting 100% reduction in mean MMDs were 17 of 214 (7.9%) in the 10 mg of atogepant group (P = .004), 11 of 223 (4.9%) in the 30 mg of atogepant group (P = .02), and 17 of 222 (7.7%) in the 60 mg of atogepant group (P = .003) compared with 2 of 214 (0.9%) in the placebo group (Figure 2). The results of the prespecified sensitivity analysis that removed day 1 data demonstrated similar results as the original analysis for the 100% reduction in 3-month mean MMDs (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Proportions of Participants Achieving Various Responder Rates by Treatment Group: 12-Week Mean Responder Rates (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population).

aP < .05 vs placebo.

bP < .01 vs placebo.

cP < .001 vs placebo.

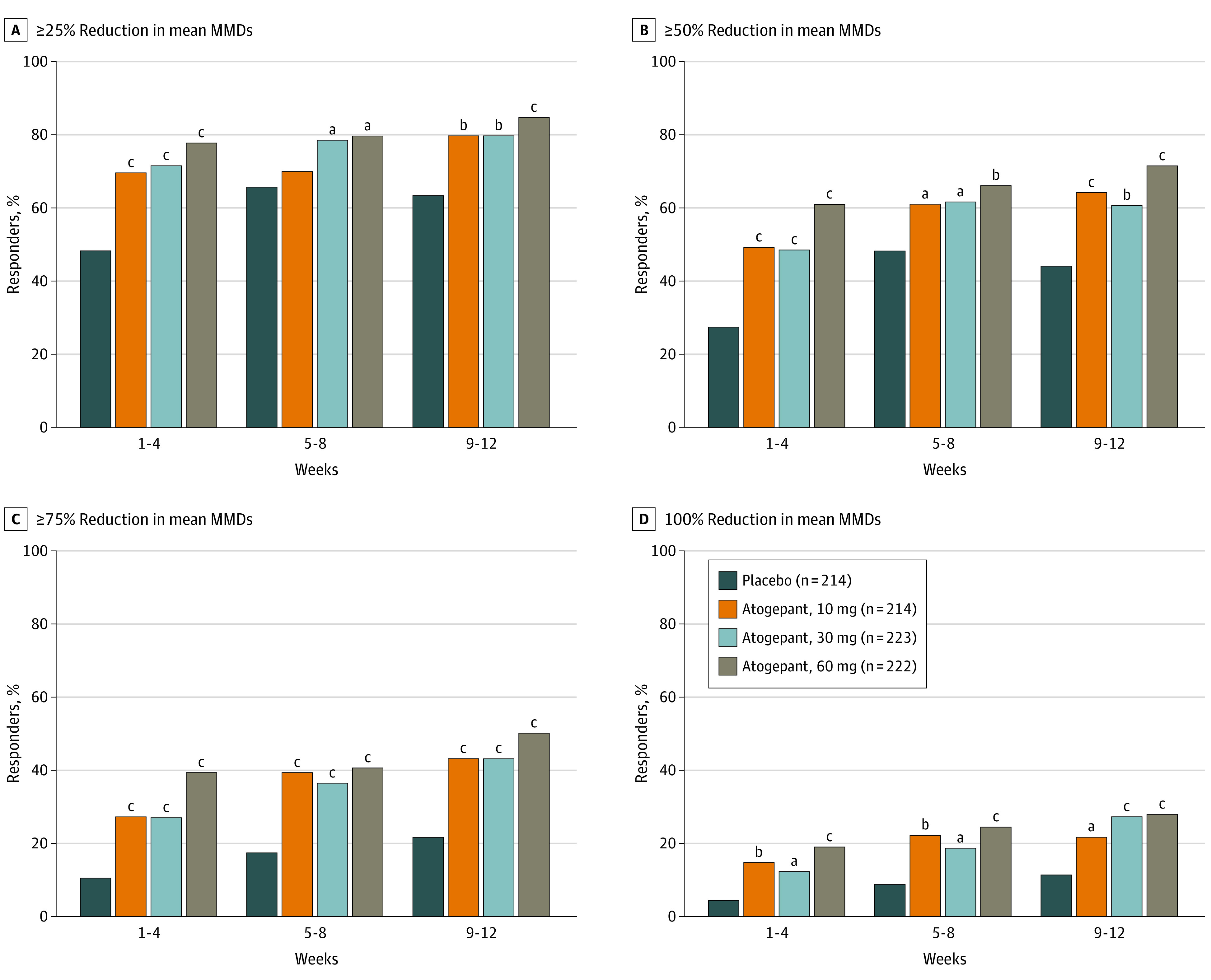

Responder Rates by 4-Week Intervals

Figure 3A presents the 25% or greater response rates, which ranged from 69.5% to 77.8% for atogepant vs 48.1% for placebo in weeks 1 through 4 (69.5% for 10 mg of atogepant, 71.7% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 77.8% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all), 69.9% through 79.7% (atogepant) vs 65.7% (placebo) in weeks 5 through 8 (69.9% for 10 mg of atogepant, P = .4984; 78.7% for 30 mg of atogepant, P = .005; 79.7% for 60 mg of atogepant; P = .005), and 79.8% to 84.6% (atogepant) vs 63.3% (placebo) in weeks 9 through 12 (79.8% for 10 mg of atogepant, 79.9% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 84.6% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all). For the 25% or greater response rates, all differences were statistically significant favoring atogepant vs placebo, except for 10 mg of atogepant for weeks 5 through 8. The 50% or greater response rates by 4-week intervals were 48.9% to 61.1% for atogepant vs 27.4% for placebo in weeks 1 through 4 (49.3% for 10 mg of atogepant, 48.9% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 61.1% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all), 60.7% to 66.2% (atogepant) vs 46.6% (placebo) in weeks 5 through 8 (60.7% for 10 mg of atogepant, P = .009; 61.6% for 30 mg of atogepant, P = .003; 66.2% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001), and 60.8% to 71.3% (atogepant) vs 43.9% (placebo) in weeks 9 through 12 (64.4% for 10 mg of atogepant, 60.8% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 71.3% for 60 mg of atogepant, P < .001 for all) (Figure 3B). All differences were statistically significant in favor of atogepant. The 75% or greater response rates by 4-week intervals ranged from 26.9% to 39.4% for atogepant vs 9.9% for placebo in weeks 1 through 4 (27.2% for 10 mg of atogepant, 26.9% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 39.4% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all), 36.5% to 40.6% (atogepant) vs 17.2% (placebo) in weeks 5 through 8 (39.3% for 10 mg of atogepant, 36.5% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 40.6% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all), and 43.1% to 49.7% (atogepant) vs 20.9% (placebo) in weeks 9 through 12 (43.1% for 10 mg of atogepant, 43.2% for 30 mg of atogepant, and 49.7% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001 for all) (Figure 3C). All differences were statistically significant in favor of atogepant. The 100% response rates by 4-week intervals ranged from 11.7% to 19.0% for all atogepant doses vs 3.8% for placebo in weeks 1 through 4 (14.1% for 10 mg of atogepant, P < .001; 11.7% for 30 mg of atogepant, P = .002; and 19.0% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001), 18.5% to 24.2% (all atogepant doses) vs 8.3% (placebo) in weeks 5 through 8 (21.9% for 10 mg of atogepant, P < .001; 18.5% for 30 mg of atogepant, P = .002; and 24.2% for 60 mg of atogepant; P < .001), and 21.3% to 27.7% (atogepant) vs 11.2% (placebo) in weeks 9 through 12 (21.3% for 10 mg of atogepant, P = .006; 27.1% for 30 mg of atogepant, P < .001; and 27.7% for 60 mg of atogepant, P < .001) (Figure 2D). All differences were statistically significant in favor of atogepant. The sensitivity analysis removing the day 1 data demonstrated similar results to the original analysis (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Proportions of Participants Achieving Various Responder Rate Reductions by Treatment Group and 4-Week Intervals (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population).

MMD indicates monthly migraine-day.

aP < .01 vs placebo.

bP < .001 vs placebo.

cP < .0001 vs placebo.

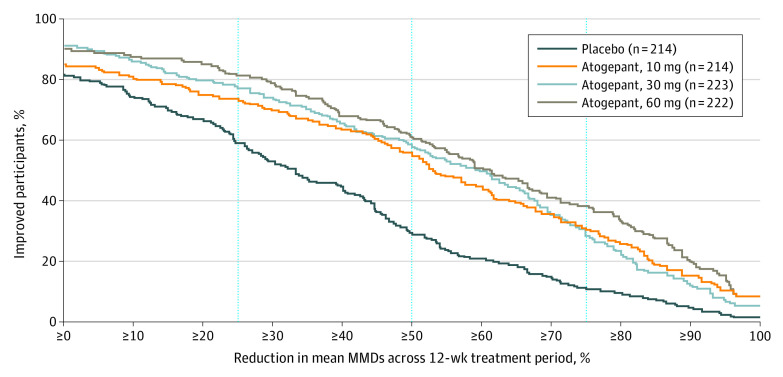

Cumulative Distribution Function

As depicted in the cumulative distribution function graph of the percent reduction from baseline in 12-week mean MMDs (Figure 4), response rates improved for each atogepant group vs placebo. A consistently higher proportion of participants in each atogepant group showed improvements in 12-week mean MMDs compared with placebo across all levels of improvement that were evaluated.

Figure 4. Proportions of Participants Achieving Specified Levels of Reduction in Mean Monthly Migraine-Days (MMDs) During 12 Weeks (Modified Intention-to-Treat Population).

Patient Global Impression of Change

At week 12, more participants in the 10 mg of atogepant group (145 of 201 [72.1%]), 30 mg of atogepant group (153 of 209 [73.2%]), and 60 mg of atogepant group (162 of 213 [76.1%]) met PGI-C responder criteria vs placebo (95 of 206 [46.1%]). The odds for achieving PGI-C response in each atogepant group was 3 times or greater that of placebo (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Satisfaction With Study Medication

A greater proportion of participants in each atogepant group met treatment satisfaction responder criteria at week 12 compared with placebo (77.7%-82.6% for atogepant and 54.8% for placebo; P < .001) (eTable 4 in Supplement 2). The odds of meeting treatment satisfaction responder criteria at week 12 for atogepant were approximately 3 to 4 times greater than placebo.

Safety

Atogepant was well tolerated, and no safety concerns were identified. The percentage of participants reporting treatment-emergent adverse effects was similar among all atogepant groups (117 of 221 [52.9%] in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 119 of 228 [52.2%] in the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 124 of 231 [53.7%] in the 60 mg of atogepant group) vs placebo (126 of 222 [56.8%]) (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse effects for atogepant were constipation (17 of 221 [7.7%] in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 16 of 228 [7.0%] in the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 16 of 231 [6.9%] in the 60 mg of atogepant group) and nausea (11 of 221 [5.0%] in the 10 mg of atogepant group, 10 of 228 [4.4%] in the 30 mg of atogepant group, and 14 of 231 [6.1%] in the 60 mg of atogepant group), compared with 1 of 222 (0.5%) for constipation and 4 of 222 (1.8%) for nausea in the placebo group.

Discussion

In this analysis of the pivotal ADVANCE trial, all atogepant doses demonstrated a statistically significant increase in responder rates vs placebo across the 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% reductions in 12-week mean MMDs, except for 10 mg of atogepant at weeks 5 to 8. The cumulative distribution function also demonstrated efficacy of all 3 doses vs placebo at every MMD reduction level. Compared with placebo, atogepant-treated participants were at least 3 times more likely to achieve a 50% or greater reduction in the 12-week mean MMDs. At all doses, atogepant was effective in the first 4 weeks for 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% responders, suggesting robust treatment effects in the first month. The proportions of participants experiencing a 25% or greater, 50% or greater, 75% or greater, and 100% MMD reduction significantly increased with treatment duration for all atogepant doses. Efficacy was sustained for 3 months, noting that placebo response rates also increased throughout the study. The responder rates were higher with increasing atogepant doses. However, the study was not designed to test dose response, so formal statistical tests were not conducted.

Some recent preventive migraine treatment trials19,20 have reported 100% responder rates, which is variably defined across studies. Often, the reported rate is for only 1 month of treatment; as such, comparisons between trials should be interpreted cautiously. For example, the differences between the 100% responder rates in the 12-week mean MMDs with atogepant (4.9%-7.9%) and those observed during weeks 9 to 12 (21.3%-27.7%) are considerable. Although the data support a rapid onset of action for atogepant, these data also suggest that responder rates continue to improve with extended treatment.

A global assessment of individuals with migraine to evaluate clinical benefit and treatment satisfaction provides insights beyond the assessed responder thresholds. Participants treated with atogepant were more satisfied with treatment and reported greater improvement in migraine attacks compared with placebo. Even if a participant did not achieve the defined responder thresholds, a high proportion of participants (72%-76%) reported feeling much better or very much better, demonstrating that some individuals experience a treatment benefit without exceeding specified responder definitions. Participant perceptions of treatment efficacy are important aspects for defining treatment success, which was reflected in analyses where participants reported feeling satisfied or extremely satisfied with atogepant.21,22 Our sample included 13.7% African American participants and 8.5% Hispanic participants. Greater inclusion of underrepresented groups in clinical trials will improve our understanding of treatment response to novel therapies in diverse populations.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Responder rates were analyzed across a range of thresholds and periods, which allows for capturing varying levels of treatment response at different times. In addition, follow-up time began as early as week 1, which allowed for evaluating the earliest onset of efficacy with atogepant. The study is at low risk for false-positive discovery because most of our results demonstrated statistically significant differences. The study also has some limitations, including that only 50% or greater responder rates were a prespecified, α-controlled outcome. Additional studies are necessary to determine the significance of other outcomes.

Conclusions

In this secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial, response to oral atogepant treatment was evident as early as the first 4 weeks and increased over time, demonstrating an early onset and sustained response. These data suggest that a 12-week trial may be of adequate duration to determine response to atogepant. Higher atogepant doses appeared to produce the greatest responder rates, which can guide clinicians in individualizing starting doses. Atogepant responder rates were consistent with other migraine prevention treatments. The ORs suggest that the likelihood of experiencing a 50% or greater reduction in mean MMDs is approximately 3 to 4 times greater with atogepant than placebo across the 12-week treatment period. Patient-reported outcomes showed a significant proportion of participants reporting feeling much better or very much better and satisfied or extremely satisfied with treatment. No new safety signals were identified for atogepant.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Reduction in 100% in 3-Month Average of MMDs (Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis)

eTable 2. Reduction in 100% of MMDs by 4-Week Intervals (Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis)

eTable 3. Percentage of Participants Reporting Adverse Events (Safety Population)

eTable 4. Patient Global Impression of Change and Treatment Satisfaction After 12 Weeks of Randomized, Blinded Treatment

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA. Pathophysiology of migraine. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:365-391. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do TP, et al. Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet. 2021;397(10283):1485-1495. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32160-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steiner TJ, Antonaci F, Jensen R, et al. ; European Headache Federation; Global Campaign against Headache . Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(4):419-426. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0320-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pressman AR, Buse DC, Jacobson AS, et al. The migraine signature study: methods and baseline results. Headache. 2021;61(3):462-484. doi: 10.1111/head.14033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Headache Society . The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1-18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. ; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society . Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1337-1345. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyepti [package insert]. Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals Inc; 2021.

- 9.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470-485. doi: 10.1177/0333102416678382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the Second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644-655. doi: 10.1111/head.12055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLenon J, Rogers MAM. The fear of needles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(1):30-42. doi: 10.1111/jan.13818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qulipta (atogepant) tablets [package insert]. AbbVie; 2021.

- 13.Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):727-737. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. ; ADVANCE Study Group . Atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(8):695-706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tassorelli C, Diener HC, Dodick DW, et al. ; International Headache Society Clinical Trials Standing Committee . Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of preventive treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(5):815-832. doi: 10.1177/0333102418758283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGinley JS, Houts CR, Nishida TK, et al. Systematic review of outcomes and endpoints in preventive migraine clinical trials. Headache. 2021;61(2):253-262. doi: 10.1111/head.14069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford JH, Kurth T, Starling AJ, et al. Migraine headache day response rates and the implications to patient functioning: an evaluation of 3 randomized phase 3 clinical trials of galcanezumab in patients with migraine. Headache. 2020;60(10):2304-2319. doi: 10.1111/head.14013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bretz F, Maurer W, Brannath W, Posch M. A graphical approach to sequentially rejective multiple test procedures. Stat Med. 2009;28(4):586-604. doi: 10.1002/sim.3495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandes JL, Diener HC, Dolezil D, et al. The spectrum of response to erenumab in patients with chronic migraine and subgroup analysis of patients achieving ≥50%, ≥75%, and 100% response. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(1):28-38. doi: 10.1177/0333102419894559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silberstein SD, Cohen JM, Yang R, et al. Treatment benefit among migraine patients taking fremanezumab: results from a post hoc responder analysis of two placebo-controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01212-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volpicelli Leonard K, Robertson C, Bhowmick A, Herbert LB. Perceived treatment satisfaction and effectiveness facilitators among patients with chronic health conditions: a self-reported survey. Interact J Med Res. 2020;9(1):e13029. doi: 10.2196/13029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable 1. Reduction in 100% in 3-Month Average of MMDs (Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis)

eTable 2. Reduction in 100% of MMDs by 4-Week Intervals (Prespecified Sensitivity Analysis)

eTable 3. Percentage of Participants Reporting Adverse Events (Safety Population)

eTable 4. Patient Global Impression of Change and Treatment Satisfaction After 12 Weeks of Randomized, Blinded Treatment

Data Sharing Statement