Key Points

Question

Is there a difference in survival or toxic effects between the main first-line therapies used for metastatic pancreatic cancer?

Findings

In this comparative effectiveness study that included 1102 patients, FOLFIRINOX (combined leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) was associated with improved survival of approximately 2 months compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and fewer posttreatment hospitalizations.

Meaning

Clinical data suggest that FOLFIRINOX should be the preferred first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

This comparative effectiveness study explores survival outcomes, posttreatment hospitalizations, and treatment costs associated with FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel regimens among patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Abstract

Importance

FOLFIRINOX (leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel are the 2 common first-line therapies for metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (mPC), but they have not been directly compared in a clinical trial, and comparative clinical data analyses on their effectiveness are limited.

Objective

To compare the FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatments of mPC in clinical data and evaluate whether there are differences in overall survival and posttreatment complications between them.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, nonrandomized comparative effectiveness study used data from the AIM Specialty Health–Anthem Cancer Care Quality Program and from administrative claims of commercially insured patients, spanning 388 outpatient centers and clinics for medical oncology located in 44 states across the US. Effectiveness and safety of the treatments were analyzed by matching or adjusting for age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, ECOG performance status (PS) score, Social Deprivation Index (SDI), liver and lymph node metastasis, prior radiotherapy or surgical procedures, and year of treatment. Patients with mPC treated between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2019, and followed up until June 30, 2020, were included in the analysis.

Interventions

Initiation of treatment with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were overall survival and posttreatment costs and hospitalization. Median survival time was calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimates adjusted with inverse probability of treatment weighting and 1:1 matching.

Results

Among the 1102 patients included in the analysis (618 men [56.1%]; median age, 60.0 [IQR, 55.5-63.7] years), those treated with FOLFIRINOX were younger (median age, 59.1 [IQR, 53.9-63.3] vs 61.2 [IQR, 57.2-64.3] years; P < .001), with better PS scores (226 [39.9%] with PS of 0 in the FOLFIRINOX group vs 176 [32.8%] in the gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel group; P = .02), fewer comorbidities (median Charlson Comorbidity Index, 0.0 [IQR, 0.0-1.0] vs 1.0 [IQR, 0.0-1.0]), and lower SDI (median, 36.0 [IQR, 16.2-61.0] vs 42.0 [IQR, 23.8-66.2]). After adjustments, the median overall survival was 9.27 (IQR, 8.74-9.76) and 6.87 (IQR, 6.41-7.66) months for patients treated with FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, respectively (P < .001). This survival benefit was observed among all subgroups, including different ECOG PS scores, ages, SDIs, and metastatic sites. FOLFIRINOX-treated patients also had 17.3% fewer posttreatment hospitalizations (P = .03) and 20% lower posttreatment costs (P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this comparative effectiveness cohort study, FOLFIRINOX was associated with improved survival of approximately 2 months compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and was also associated with fewer posttreatment complications. A randomized clinical trial comparing these first-line treatments is warranted to test the survival and posttreatment hospitalization (or complications) benefit of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a common and aggressive cancer, with more than 56 000 new cases in the US annually.1 Although the 5-year survival rate has improved from approximately 5% in 2000 to approximately 11% in 2021, pancreatic cancer is still the deadliest among all common cancer types.1

Gemcitabine was historically used as monotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPC). In 2011, FOLFIRINOX (leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) was shown to be superior to gemcitabine alone in a clinical trial (median survival of 11.1 and 6.8 months for FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine alone, respectively).2 However, it was suggested that FOLFIRINOX increases toxic effects and was therefore recommended as a treatment for patients with higher levels of function and capability of self-care.2 A second, roughly contemporaneous trial3 evaluated gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel compared with gemcitabine alone and found a survival benefit with the combined treatment (median survival of 8.7 and 6.6 months for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine alone, respectively). As of today, most patients with mPC are administered FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line therapy. However, a clinical trial directly comparing the effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel has not been performed. Furthermore, clinical trials often fail to reflect real-world situations and therefore cannot be generalized to support evidence-based decision-making for more diverse patient populations.4

Several studies5,6,7,8,9,10,11 have been published within the last 8 years using retrospective clinical data to compare FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in mPC treatment. However, most of these studies focused on a single hospital or specific region and were performed using only several hundred patients.5,6,7 Other studies have lacked critical information required to accurately match between patient cohorts.8 In general, most studies have shown a survival benefit of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel,9 whereas a few studies have shown comparable effectiveness.10 Reports regarding toxicity levels are inconsistent; some report no obvious difference in toxic effects,9 whereas some show more adverse events associated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel leading to treatment interruptions,11 and others show increased toxic effects in patients receiving FOLFIRINOX.6

Administrative claims are widely used to characterize patient populations and disease trends over time but are rarely used in outcomes research. Many times, clinical information needed for comparison between patient populations is not captured by claims,12 and therefore such missing data hinder the use of claims in effectiveness analyses. In this study, we take advantage of data captured through the Cancer Care Quality Program13 to augment insurance claims. These data include essential information such as performance status (PS), line of treatment, TNM staging, pathology, and treatment plan.

Using this comprehensive clinical data set from 1102 patients with mPC across multiple regions and health care systems in the US, we explored survival outcomes, posttreatment hospitalizations, and treatment costs associated with FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel regimens. We hypothesized that by accounting for the heterogeneous characteristics of patients and using multiple causal inference methods, FOLFIRINOX would be associated with improved survival and fewer posttreatment adverse events.

Methods

Ethical Declaration

This comparative effectiveness study was designed as an analysis based on medical claims data. There was no active enrollment or active follow-up of study participants, and no data were collected directly from individuals. The study was not required to obtain additional institutional review board approval, because the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule14 permits protected health information in a limited data set to be used or disclosed for research, without individual authorization, if certain criteria are met. This study followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) reporting guideline.

Data Source

This retrospective comparative effectiveness study is based on nationally representative clinical data submitted to the AIM Specialty Health–Anthem Cancer Care Quality Program together with associated claims and laboratory data.13 Requests submitted through the AIM Specialty Health portal include, among other information, the intended regimen for treatment, date of intended treatment, TNM staging, line of therapy, and ECOG PS score. The claims data include medical and pharmacy claims for nearly 40 million members with commercial insurance across 14 US regional health plans, but exclude claims from government, Medicare, and Medicaid members. All study data were kept anonymous to safeguard patient confidentiality. Death was inferred from discharge status and complemented with information from national death registries and obituary data.

Cohort Definition

The study cohort included patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2019. On the basis of this inclusion criterion, we identified 3461 patients. Only patients with stage IV, first-line treatment with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel with an ECOG PS score ranging from 0 to 3 were included in analyses. On the basis of this inclusion criterion, we identified 1383 patients. Patients were followed up until June 30, 2020, or death, whichever occurred first (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

FOLFIRINOX indicates leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin; Gem-Nab-P, gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel; ITT, intention to treat; and PS, performance status.

Patients were excluded if the treatment plan as defined in the clinical data could not be corroborated by the claims data. First, we excluded 12 patients missing medical claims. For 117 patients, there was no claim of chemotherapy. An additional 152 patients were excluded because either the treatment date was more than 40 days from the intention to treat or the regimen could not be validated using claim data with the same regimen at the same time of treatment start (eFigure 1C in the Supplement).

The patients spanned 388 outpatient centers and clinics for medical oncology located in 44 states across the United States. The index date was defined as the start date of first-line treatment and was confirmed using administrative claims.

Covariates and Outcomes

Our primary effectiveness outcome was overall survival, defined as the time from treatment index date to death or last follow-up if censored. Secondary outcomes of interest included posttreatment costs and hospitalization. Posttreatment outcomes were identified in the 14 days after the index date.

Baseline characteristics included prognostic stage, ECOG PS score, metastasis sites, prior radiotherapy or surgical procedures, comorbidities, and sociodemographic information. The PS score was determined by the treating physician at the beginning of the treatment. The ECOG PS score has been shown to be subjective and inconsistent15; therefore, we used serum albumin measurements, which have been shown to correlate with the PS score,16 for validation. Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) according to patient claims in the 1 year before and as many as 10 days before the index date. The CCI was calculated using the R comorbidity package, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing),17 and consists of 17 different medical conditions; metastasis and cancer were removed from the score. Metastatic site was identified using metastasis-associated codes from International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, in the 2 months before the index date to 20 days subsequently. Sociodemographic information included age, sex, and Social Deprivation Index (SDI) calculated based on patient zip code. Zip code was not captured and was not part of the final data set. The numerical variables—ECOG PS score, SDI, and CCI—were normalized using minimum-maximum normalization. Prior radiotherapy or surgery procedures were evaluated using associated Current Procedural Terminology codes to 3 months before the index date. The data set used for the analyses was deidentified according to the Safe Harbor method18 and did not include names, dates (only differences between dates), zip codes (only rounded SDI), or any other identifying information.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients treated with FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney test or the unpaired 2-tailed t test for continuous variables. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Overall survival was defined as the interval between the initiation of first-line therapy (index date) and the date of death. Patients without a mortality event were censored at the date of their last medical claim or the end of study. Median survival time was calculated with a Kaplan-Meier estimate, and 0.8 and 0.2 survival quantiles were calculated to support the median survival difference. Unadjusted survival was estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and differences between survival curves were assessed using the log-rank test.19

To verify that the survival estimates were not a result of confounding by baseline characteristics, we used various methods to adjust for potential confounding factors. Exact 1:1 matching for age binned the participants into subsets, and nearest matching on propensity score based on all the other features was performed using the Matchit R package, version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).20 After applying the matching, P values were calculated for the source variables to validate that there was no significant difference between matched cohorts. Kaplan-Meier estimator was then applied to the matched cohort.

Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model with the treatment type as the dependent variable, regressed on the potentially confounding variables. The causalib package, version 0.1.3 (Python),21 was used to compute and evaluate inverse propensity weighting. To assess survival, the Kaplan-Meier estimator was weighted by the inverse propensity score.

The matched cohort and the inverse probability of treatment weighted (IPTW) cohort were also used for the posttreatment effect comparisons. Secondary outcomes, including posttreatment costs and hospitalizations, were compared between FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatment groups using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test for discrete outcomes and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for continuous outcomes.

Results

Study Population

Using clinical data and administrative claims, we identified a study cohort of 1102 patients (618 men [56.1%] and 484 women [43.9%]; median age, 60.0 [IQR, 55.5-63.7] years) diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer from January 2016 to December 2019 who were at least 18 years of age at the start of their palliative first-line treatment with FOLFIRINOX (566 [51.4%]) or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (536 [48.6%]). Race and ethnicity information were not available to the health insurance company and therefore were not considered. This cohort included only patients with corroborated clinical and claims data and without missing data (see Methods for full inclusion and exclusion procedure and Figure 1). We further defined another cohort for intention-to-treat analysis that included 1383 patients; of these, 693 (50.1%) were treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Of the 281 patients who were excluded from the treated cohort, 117 were not treated at all. Of these, most died within 2 months after the planned treatment start date (92 [78.6%]), and most probably did not receive any treatment owing to the severity of their condition (eFigure 1A and B in the Supplement). In patients with poor PS (PS score of 2), there was a significant difference in those not receiving treatment between the 2 regimens: only 3 patients (7.3%) who were intended to receive FOLFIRINOX treatment did not receive treatment, whereas 17 (22.7%) intended to receive gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatment were not treated (eFigure 1B in the Supplement). In patients with good PS (PS score of 0), the fraction of patients who were eventually not treated was similar (13 [4.8%] in the FOLFIRINOX group and 13 [6.1%] in the gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel group).

Owing to the observational nature of the study design, patients receiving FOLFIRINOX differed in multiple demographic and clinical characteristics from those treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (Table 1). In general, patients receiving the combination gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatment were older (median age, 61.2 [IQR, 57.2-64.3] vs 59.1 [IQR, 53.9-63.3] years; P < .001), had more comorbidities (median CCI, 1.0 [IQR, 0.0-1.0] vs 0.0 [IQR, 0.0-1.0]; P = .01), and had poorer PS scores (226 [39.9%] with PS of 0 in the FOLFIRINOX group vs 176 [32.8%] in the gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel group; P = .02). Of note, the PS score agreed with albumin levels: 41 patients (77.4%) with abnormal albumin levels had a high PS score (eFigure 2A and B in the Supplement). Socioeconomic status (measured using SDI) of the patients also significantly differed between the treatment groups (median SDI, 42.0 [IQR, 23.8-66.2] vs 36.0 [IQR, 16.2-61.0]; P = .003). Radiotherapy to 3 months before the treatment was documented in 7 of 566 (1.2%) FOLFIRINOX-treated patients and 19 of 536 (3.5%) gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel–treated patients (P = .02). Surgery in the 3 months before the treatment was documented for only 13 patients (1.2%) in the total cohort, with no difference between the treatment groups. There were no significant differences in the metastasis sites between the treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Cohorts .

| Characteristic | Treatment groupa | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 1102) | FOLFIRINOX group (n= 566) | Gem-Nab-P group (n = 536) | ||

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 60.0 (55.5-63.7) | 59.1 (53.9-63.3) | 61.2 (57.2-64.3) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 618 (56.1) | 327 (57.8) | 291 (54.3) | .27 |

| Women | 484 (43.9) | 239 (42.2) | 245 (45.7) | |

| Social Deprivation Index, median (IQR)b | 39.0 (19.0-64.0) | 36.0 (16.2-61.0) | 42.0 (23.8-66.2) | .003 |

| Clinical features | ||||

| ECOG performance status scorec | ||||

| 0 | 402 (36.5) | 226 (39.9) | 176 (32.8) | .06 |

| 1 | 606 (55.0) | 299 (52.8) | 307 (57.3) | |

| 2 | 84 (7.6) | 36 (6.4) | 48 (8.9) | |

| 3 | 10 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0-1.0) | 0.0 (0.0-1.0) | 1.0 (0.0-1.0) | .01 |

| Metastasis sites | ||||

| Liver | 677 (61.4) | 358 (63.3) | 319 (59.5) | .23 |

| Peritoneum | 146 (13.2) | 72 (12.7) | 74 (13.8) | .66 |

| Lung | 124 (11.3) | 58 (10.2) | 66 (12.3) | .32 |

| Bone | 62 (5.6) | 29 (5.1) | 33 (6.1) | .54 |

| Lymph node | 155 (14.1) | 78 (13.8) | 77 (14.4) | .85 |

| Digestive tract | 86 (7.8) | 43 (7.6) | 43 (8.0) | .88 |

| Previous treatment | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 26 (2.3) | 7 (1.2) | 19 (3.5) | .02 |

| Surgery | 13 (1.2) | 6 (1.1) | 7 (1.3) | .92 |

| Year of treatment | ||||

| 2016 | 211 (19.1) | 97 (17.1) | 114 (21.3) | .10 |

| 2017 | 307 (27.9) | 152 (26.9) | 155 (28.9) | .49 |

| 2018 | 287 (26.0) | 131 (23.1) | 156 (29.1) | .03 |

| 2019 | 298 (27.0) | 186 (32.9) | 112 (20.7) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: FOLFIRINOX, combined leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin; Gem-Nab-P, gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (%) of patients. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Scores range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater deprivation.

Scores range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating worse status.

Because these features differed significantly between the treatment groups, we hypothesized that they may, in part, be associated with treatment decisions. We therefore trained a logistic regression model to determine whether these features are associated with the regimen used for treatment. The accuracy of the outcome, as defined by the area under the curve, was only 0.61 (P < .001), suggesting that although the treatment decision is somewhat driven by clinical or demographic characteristics, it is mostly stochastic.

Overall Survival

Using the treated cohort, we compared the effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel with an end point of all-cause mortality. We validated mortality data by examining the carbohydrate antigen 19.9 measurement, which is released by pancreatic cancers and is a known marker associated with survival time in mPC.22 As expected, the survival agreed with the carbohydrate antigen 19.9 levels in that patients with abnormal levels had 2.8% shorter survival, although not significantly (P = .20) (eFigure 2C in the Supplement).

The Kaplan-Meier estimator for unadjusted survival suggested superior survival benefit for FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (median survival, 9.37 [IQR, 8.68-10.09] and 6.84 [IQR, 6.15-7.76] months, respectively; P < .001) (Figure 2A and Table 2). To adjust for the covariates, we used matching on the confounding features. The matched subpopulations had 456 patients for each treatment (n = 912), which is 82.7% of the full cohort (eTable in the Supplement). Survival analysis on the matched cohort similarly showed significant survival benefit for FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (median survival, 9.27 [IQR, 8.48-10.16] and 7.10 [IQR, 6.21-7.92] months, respectively; P = .003) (Figure 2B and Table 2). Furthermore, we performed IPTW adjusting for the covariates. The Kaplan-Meier fit using IPTW showed similar results as well (median survival of 9.27 [IQR, 8.74-9.76] for FOLFIRINOX and 6.87 [IQR, 6.41-7.66] months for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel; P < .001) (Figure 2C and Table 2). Overall, the median survival difference between the treatments was approximately 2.3 months or approximately 33% longer survival with FOLFIRINOX. Moreover, we observed consistent survival benefit of FOLFIRINOX in both the 20% and the 80% survival quantiles (Table 2). Finally, an analysis of the intention-to-treat cohort increased the survival benefit gap between the treatments (median survival of 9.2 [IQR, 8.21-9.86] months for FOLFIRINOX vs 6.01 [IQR, 5.22-6.80] months for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel; P < .001), rejecting the hypothesis that early mortality or worse prognosis may explain the superiority of FOLFIRINOX over gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in survival benefit (Figure 2D and Table 2).

Figure 2. Survival Analysis Comparing Treatment Groups.

Kaplan-Meier fit for patients treated with FOLFIRINOX (leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (Gem-Nab-P). Dashed lines and numbers show the median survival. A, Naive analysis without any adjustments for the treated cohort. B, 1:1 Matching of the treated cohort. C, A model weighted with inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) for the treated cohort. D, 1:1 Matching of the intention to treat (ITT) cohort.

Table 2. Median Survival Differences and 20% and 80% Survival Quantiles Using Different Matching Methods .

| Method | Survival (95% CI), mo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 20% Quantile | 80% Quantile | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX vs Gem-Nab-P | Change | FOLFIRINOX vs Gem-Nab-P | Change | FOLFIRINOX vs Gem-Nab-P | Change | |

| Treated cohort | ||||||

| Naive | 9.37 (8.68-10.09) vs 6.84 (6.15-7.76) | 2.53 | 3.85 (3.29-4.47) vs 2.50 (2.20-2.93) | 1.35 | 17.05 (15.84-21.26) vs 14.79 (13.11-16.23) | 2.27 |

| 1:1 Matching | 9.27 (8.48-10.16) vs 7.10 (6.21-7.92) | 2.17 | 3.75 (3.19-4.47) vs 2.57 (2.30-3.26) | 1.18 | 17.32 (15.64-21.82) vs 14.92 (13.93-16.89) | 2.40 |

| IPTW | 9.27 (8.74-9.76) vs 6.87 (6.41-7.66) | 2.40 | 3.81 (3.49-4.24) vs 2.57 (2.37-2.99) | 1.25 | 17.02 (15.94-18.80) vs 14.92 (14.10-16.07) | 2.10 |

| ITT cohort | ||||||

| Naive | 9.23 (8.41-9.76) vs 5.82 (5.32-6.51) | 2.92 | 3.29 (2.73-3.84) vs 1.61 (1.45-1.91) | 1.68 | 17.02 (15.57-19.15) vs 14.09 (12.39-15.44) | 3.42 |

| 1:1 Matching | 9.20 (8.68-10.09) vs 5.82 (5.19-6.67) | 3.38 | 3.09 (3.29-4.47) vs 1.68 (1.51-2.17) | 1.41 | 17.25 (15.24-19.75) vs 14.29 (12.58-15.64) | 2.96 |

| IPTW | 9.20 (8.48-9.53) vs 6.08 (5.62-6.54) | 3.12 | 3.22 (2.73-3.58) vs 1.68 (1.54-1.91) | 1.54 | 16.30 (15.84-18.27) vs 14.23 (13.11-15.08) | 2.07 |

Abbreviations: FOLFIRINOX, combined leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin; Gem-Nab-P, gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; ITT, intention to treat.

It has been suggested that gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is less toxic and more tolerable than FOLFIRINOX.23 However, using a stratified analysis, we observed that patients receiving FOLFIRINOX had improved median survival across all ECOG PS levels (PS score = 0: 9.83 [IQR, 9.20-10.75] vs 7.79 [IQR, 6.67-8.68] months [P < .001]; PS score = 1: 9.14 [IQR, 8.18-9.66] vs 6.84 [IQR, 6.21-7.66] months [P < .001]; PS score = 2: 7.89 [IQR, 3.29-9.86] vs 4.80 [IQR, 3.68-7.82] months [P = .03]) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In fact, a multivariable survival analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression models stratified by all relevant covariates still showed a significant regimen hazard ratio (hazard ratio, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.06-1.59]; P = .01).

Posttreatment Outcomes

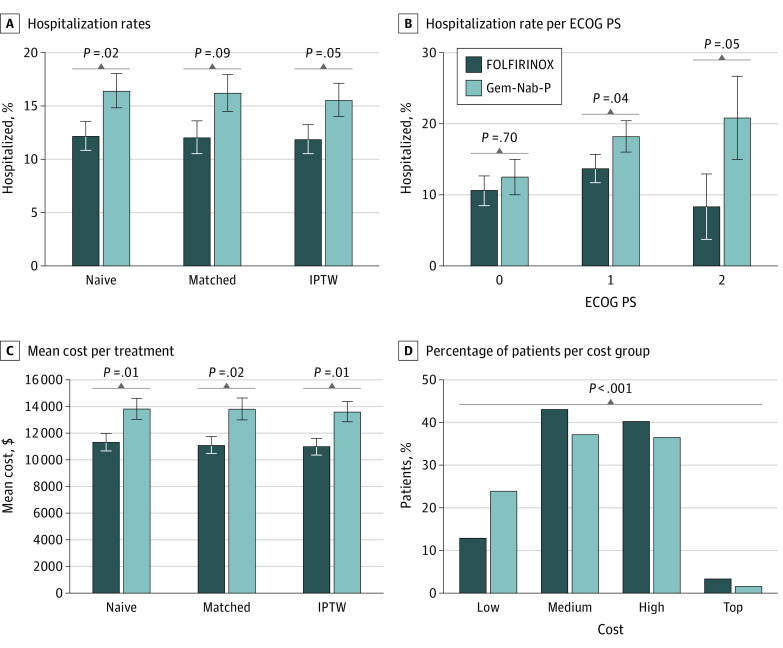

To study posttreatment outcomes, we compared hospitalization rates of the patients within 14 days from the initiation of the treatment. We found that 69 patients (12.2%) treated with FOLFIRINOX were hospitalized after treatment compared with 88 patients (16.4%) who were hospitalized after gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatment. Using both the matched cohort and the IPTW adjustment, we estimate that FOLFIRINOX leads to 17.3% fewer hospitalization events 14 days after first treatment (P = .03) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Comparison of Posttreatment Outcomes of Treatment Groups .

A, Percentage of hospitalized patients, for patients treated with FOLFIRINOX (leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) or gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (Gem-Nab-P). The hospitalization rate was assessed for the full cohort (naive) and the inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) and matched cohorts. B, Percentage of hospitalized patients per ECOG performance status (PS) score. C, Mean total cost assessed for the full cohort (naive) and the IPTW and matched cohorts. D, Percentage of patients by cost groups and treatment group. Low indicates less than $2000; medium, $2000 to $10 000; high, greater than $10 000 to $50 000; and top, greater than $50 000.

The benefit of FOLFIRINOX in preventing subsequent hospitalizations is more pronounced in patients with poor ECOG PS (PS score >0), with 28% fewer hospitalizations compared with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel treatment (P = .04) (Figure 3B). Sepsis was the most common diagnosis during hospitalization in both treatment groups (20 of 166 [12.7%] hospitalizations), followed by pulmonary embolism and dehydration. Interestingly, we observed noninfectious gastroenteritis in 7 hospitalizations (9.2%) after FOLFIRINOX treatment, whereas this was not a common diagnosis during hospitalization among patients receiving gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Finally, we compared the total cost for the patients after the start of the treatment as a proxy for adverse reactions. In general, the mean cost for patients receiving FOLFIRINOX was 20% less than that for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (IPTW data, $13 600 vs $11 000; P = .007) (Figure 3C). Moreover, although 111 patients receiving FOLFIRINOX (24.3%) had a total cost less than $2000 in the 14 days after the start of the treatment, only 59 patients treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (12.9%) had this low total cost (P < .001) (Figure 3D). Even when excluding hospitalized patients, the fraction of patients with lower costs was higher among those treated with FOLFIRINOX (the mean cost for patients receiving FOLFIRINOX was 16% less than that for patients receiving gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [IPTW data, $9380 vs $7840; P = .002]).

Discussion

Using cross-institutional clinical analysis, we found that treatment with FOLFIRINOX was associated with more than 2 months of survival advantage over gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel. We used multiple statistical approaches to demonstrate that the difference in survival outcomes was not explained by potential confounding factors. The median survival reported herein is approximately 2 months less than that reported in the randomized clinical trials of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.2,3 Several factors may contribute to the efficacy-effectiveness gap, including differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria (our data include patients with PS scores >1) and the more diverse population represented in our data compared with underrepresentation of individuals who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups in randomized clinical trials. It should be noted that previous observational studies reported median survivals that are similar to those reported herein.

The FOLFIRINOX randomized clinical trial2 suggested that excessive adverse events were associated with FOLFIRINOX, resulting in more patients with compromised functional status treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line therapy. In our analysis, however, patients receiving FOLFIRINOX had improved posttreatment outcomes, even among patients with high ECOG PS scores. The reduced posttreatment effects we observed in patients treated with FOLFIRINOX may be due to recently introduced treatments to improve tolerability of FOLFIRINOX adverse events such as nausea and diarrhea.24

In our analysis, we observed some nontrivial associations that require further investigation. For example, our study found that patients treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel were generally from regions of lower socioeconomic status, despite the higher cost of the treatment. This may suggest that at least in some areas, FOLFIRINOX is the preferred treatment irrespective of its lower cost, or perhaps that there are uncovered correlations between comorbidities and the choice of the treatment that are enriched in regions of lower socioeconomic status. Although this finding needs to be corroborated by additional studies, potential health equity implications must be considered and addressed.

To our knowledge, this is the first cross-institutional study that uses clinical data collected from health insurance claims to assess and compare the effectiveness of treatments for pancreatic cancer. We expect that combining different types of data sets currently available to health insurers for outcomes research will grow in the coming years and will prove to be a highly useful tool that can improve clinical decision-making.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. First, our cohort of 1102 patients is, to our knowledge, among the largest of such studies published to date. Second, our data set includes a wide set of features that should be considered to match baseline differences across patients receiving different treatment regimens. Third, the patient population and treating oncologists represent a highly diverse population coming from multiple clinics across the US. Previous studies5,6,7,8,9,10,11 were mostly based on patients from a single hospital. This diversity reduces the chances of selection bias in treatment decisions and increases the generalizability of the conclusions for patients with different background characteristics. Last, using data sourced from a health insurer allowed us to examine cost of care as a proxy for the level of intervention that the patients consume and the level of posttreatment complications. We believe that our cost of care–based analysis suggesting increased hospitalizations after treatment with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is another layer that should be considered during treatment decision-making.

Our analysis also has several limitations. First, as noted, the data were collected for administrative and reimbursement-related purposes and were not part of clinical decision-making. Another limitation of claims data is that coding practices may vary significantly across physicians or practices and may not be representative of what is done in clinical practice for various reasons, although it should be noted that our analysis is based on a combination of claims and reported clinical data. Also, because our focus was on all-cause mortality data, we may have ignored clinically relevant outcomes such as toxic effects, progression-free survival, and quality of life metrics. In addition, patients could potentially leave the insurance plan or use private services that are not well documented. Last, because this is an observational study, there are inherent limitations from time-related biases and other residual confounding from unmeasured factors.

Conclusions

The findings of this observational comparative effectiveness study suggest that FOLFIRINOX was associated with better clinical outcomes than gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel among patients with mPC. These data support the need for a randomized clinical trial comparing these regimens.

eTable. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Matched Cohort

eFigure 1. Differences Between Treated and Intention-to-Treat but Nontreated Patients

eFigure 2. Validation of ECOG PS and Death Information Using Laboratory Test Results

eFigure 3. Survival Analysis Stratified by ECOG PS

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Pancreatic Cancer . Revised January 21, 2022. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- 2.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. ; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup . FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817-1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein D, El-Maraghi RH, Hammel P, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2):dju413. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fogel DB. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: a review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2018;11:156-164. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegewisch-Becker S, Aldaoud A, Wolf T, et al. ; TPK-Group (Tumour Registry Pancreatic Cancer) . Results from the prospective German TPK clinical cohort study: treatment algorithms and survival of 1,174 patients with locally advanced, inoperable, or metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(5):981-990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muranaka T, Kuwatani M, Komatsu Y, et al. Comparison of efficacy and toxicity of FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel in unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8(3):566-571. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.02.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KKW, Guo H, Cheng S, et al. Real-world outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in advanced pancreatic cancer: a population-based propensity score-weighted analysis. Cancer Med. 2020;9(1):160-169. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda O, Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi J, et al. Real-world experience with FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of pancreatic cancer in Japan. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 10):x69. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx660.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollmann S, Alloul K, Attard C, Kavan P. An indirect treatment comparison and cost-effectiveness analysis comparing FOLFIRINOX with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:ii11. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu164.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riedl JM, Posch F, Horvath L, et al. Gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel versus FOLFIRINOX for palliative first-line treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer: a propensity score analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;151:3-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun JW, Lee SH, Kim JS, et al. Comparison between FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel including sequential treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer: a propensity score matching approach. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):537. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08277-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal K, Gill RR, Widick P, et al. Association of performance status with survival in patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab monotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037120. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern DM, Barron JJ, Wu B, et al. A validation of clinical data captured from a novel Cancer Care Quality Program directly integrated with administrative claims data. Pragmat Obs Res. 2017;8:149-155. doi: 10.2147/POR.S140579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services . The HIPPA privacy rule. Reviewed March 31, 2022. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/index.html

- 15.Blagden SP, Charman SC, Sharples LD, Magee LRA, Gilligan D. Performance status score: do patients and their oncologists agree? Br J Cancer. 2003;89(6):1022-1027. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Evaluation of cumulative prognostic scores based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with inoperable non–small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(6):1028-1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasparini A. Comorbidity: an R package for computing comorbidity scores. J Open Source Softw. 2018;3(23):648. doi: 10.21105/joss.00648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services . Guidance regarding methods for de-identification of protected health information in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule. Reviewed November 6, 2015. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html#safeharborguidance

- 19.Klein JP, Logan B, Harhoff M, Andersen PK. Analyzing survival curves at a fixed point in time. Stat Med. 2007;26(24):4505-4519. doi: 10.1002/sim.2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42(8):1-28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v042.i08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimoni Y, Karavani E, Ravid S, et al. An evaluation toolkit to guide model selection and cohort definition in causal inference. arXiv. Preprint posted online June 2, 2019. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1906.00442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger AC, Garcia M Jr, Hoffman JP, et al. Postresection CA 19-9 predicts overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer treated with adjuvant chemoradiation: a prospective validation by RTOG 9704. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(36):5918-5922. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pusceddu S, Ghidini M, Torchio M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX in the first-line setting of metastatic pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4):E484. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UpToDate. FOLFIRINOX for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Updated March 25, 2022. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image?imageKey=ONC%2F79571

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Matched Cohort

eFigure 1. Differences Between Treated and Intention-to-Treat but Nontreated Patients

eFigure 2. Validation of ECOG PS and Death Information Using Laboratory Test Results

eFigure 3. Survival Analysis Stratified by ECOG PS