Abstract

Background.

The nature of the relationship between dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has clinical and nosological importance. The aim of this study was to evaluate the evidence for a dissociative subtype of PTSD in two independent samples and to examine the pattern of personality disorder comorbidity associated with the dissociative subtype of PTSD.

Methods.

Latent profile analyses were conducted on PTSD and dissociation items reflecting derealization and depersonalization in two samples of archived data: Study 1 included 360 male Vietnam War Veterans with combat-related PTSD; Study 2 included 284 female Veterans and active duty service personnel with PTSD and a high base rate of exposure to sexual trauma.

Results.

The latent profile analysis yielded evidence for a three-class solution in both samples: the model was defined by moderate and high PTSD classes and a class marked by high PTSD severity coupled with high levels of dissociation. Approximately 15% of the male sample and 30% of the female sample were classified into the dissociative class. Women (but not men) in the dissociative group exhibited higher levels of comorbid avoidant and borderline personality disorder diagnoses.

Conclusions.

Results provide support for a dissociative subtype of PTSD and also suggest that dissociation may play a role in the frequent co-occurrence of PTSD and borderline personality disorder among women. These results are pertinent to the on-going revisions to the DSM and suggest that consideration should be given to incorporating a dissociative subtype into the revised PTSD criteria.

Keywords: Dissociation, PTSD, multivariate analysis, taxonomy, Veterans

Since the classic work of Pierre Janet in 1889 (see van der Kolk et al.[1]), dissociative symptoms that manifest in the context of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been theorized to have their genesis in trauma exposure[2] and reflect problems in the integration of fundamental cognitive processes governing attention, perception, emotion, consciousness, identity, and memory.[3–5] Such disruption in the integration and processing of emotion are thought to reflect a unique neurocircuitry pattern marked by pre-frontal suppression of amygdala activity.[6] The association between PTSD and dissociation is of clinical and nosological importance but the specific nature of this association is a source of debate.

Theorists have advanced two primary hypotheses about the relationship between dissociation and PTSD. One, the subtype hypothesis, posits that dissociation is present in a small but discrete subgroup of individuals with PTSD.[6–10] For example, Waelde and colleagues[9] performed a taxometric analysis on the Dissociative Experiences Scales (DES)[11] in trauma-exposed Vietnam War Veterans and found that 32% of those with PTSD could be classified into a discrete dissociative taxon. Putnam et al.[8] observed that the mean score on the DES among individuals with PTSD (and other disorders) was a function of a subset of participants with very high levels of dissociation, as opposed to a reflection of a continuous dispersion of such symptoms in the group. Finally, Lanius et al.[6] reviewed both psychometric and neurobiological research and found parallel lines of support for a dissociative subtype of PTSD. Specifically, these authors suggested that this subtype is characterized by blunted emotional responses to trauma cues and over-activation of brain regions thought to be associated with emotion modulation, namely the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex. The alternative to the dissociative subtype hypothesis is that dissociation is a primary facet of PTSD that is distributed evenly among the PTSD population, and is a general marker for disorder severity[12]. Support for this hypothesis comes from research suggesting a moderate to strong correlation between PTSD and dissociation symptom severity (for an extensive review, see Carlson et al.[13]).

This distinction carries implications for revisions to the PTSD criteria in DSM-5. Specifically, evidence for a discrete and markedly dissociative subgroup of individuals with PTSD would support proposals to define a dissociative subtype in the PTSD section of the DSM[4,6] and imply that the phenomenon is a clinically relevant and distinct, yet atypical presentation of PTSD. In contrast, evidence for a linear, dimensional relationship between these two sets of symptoms would suggest that dissociation is syndromal with PTSD and not limited to a categorically distinct subgroup of individuals with the disorder; evidence that dissociation is a common and core component of PTSD would argue against the validity of the subtype because dissociation would not be limited to a discrete group of individuals.

In a recent study, we used latent profile analysis (LPA, a form of latent class analysis) to evaluate the structure of dissociation and PTSD symptoms in a sample of trauma-exposed military Veterans and their intimate partners.[10] LPA is a multivariate data analytic approach to the identification of subgroups from a heterogeneous population. LPA identifies classes of individuals within a dataset based on unobserved (i.e., latent) characteristics. The LPA of PTSD and dissociation symptoms yielded evidence for three latent classes: a low PTSD severity group, a high PTSD severity group without dissociation, and a group marked by both high PTSD and dissociative symptoms. The dissociative class was defined by distinctly high scores on derealization, depersonalization, and flashbacks; the group represented approximately 12% of individuals with PTSD and 6% of the full sample. Individuals in the dissociative group reported greater severity of childhood and adult sexual assault relative to individuals with equivalent severity of PTSD symptoms without dissociation, suggesting a possible etiologic link with severe sexual trauma. That study was the first to use LPA to evaluate the evidence for a dissociative subtype in a large, well-assessed sample, but was limited by the focus on male Veterans (who comprised the majority of that sample) with a high prevalence of combat exposure, and by the use of a single measure of dissociation, namely, items drawn from the associated features section of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS).[14]

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the replicability of these findings in two independent samples and to extend that work by examining the relationship between dissociation and PTSD in women Veterans with a high base rate of exposure to sexual assault assessed with a different measure of dissociation. An additional aim of this study was to extend prior work by evaluating the pattern of comorbid personality disorders (PDs) associated with the dissociative subtype.

To evaluate these aims, we conducted secondary analyses from two existing datasets: a multisite study of male Vietnam Veterans with current combat-related PTSD who participated in a randomized clinical trial (RCT) PTSD[15] (Study 1), and a multisite study of female Veterans and active-duty personnel with current PTSD who participated in a RCT for PTSD[16] (Study 2). We hypothesized that a LPA would yield evidence for a three class solution: a low or moderate PTSD severity class, and two high PTSD severity classes distinguished from one another by the presence of derealization and depersonalization in a small subset of the participants. We hypothesized the dissociative group would have higher severity ratings on PTSD Criteria B3 (flashbacks), and C3 (psychogenic amnesia), and higher prevalence of comorbid borderline PD, given that dissociation is also a prominent feature of borderline PD and thought to reflect a transient reaction to stress.[3,17–18] Alternatively, if the class solution revealed groups differing only on symptom severity (i.e., if individuals with moderate PTSD severity also exhibited moderate levels of dissociation and individuals with high PTSD severity exhibited high levels of dissociation), this would argue against the validity of the dissociative subtype and support that notion that dissociation is syndromal with PTSD and simply varies as a function of disorder severity.

Study 1 (Male Sample)

Method

Sample.

Participants were 360 male Vietnam Veterans with combat-related PTSD who participated in a multisite RCT of group therapy for PTSD.[15] Inclusion criteria included having a current PTSD diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria and a symptom severity of 45 or higher on the CAPS;[14] 12 participants with severity scores under 45 who met criteria for current PTSD were ultimately enrolled in the trial. Participants taking psychoactive medications were required to have a stable regimen for at least 2 months before study entry, and agree to terminate other psychotherapy for PTSD (except 12-step programs) during the study. Exclusion criteria included current or lifetime diagnoses of psychotic disorder, mania, or bipolar disorder, current major depression with psychotic features, current alcohol or drug dependence, unwillingness to refrain from substance abuse during treatment or at work, significant cognitive impairment, or severe cardiovascular disorder.

Mean age of participants was 50.61 (SD = 3.61, range 44 to 74). Most (66.9%, n = 241) had more than a high school education, and about half (51.1%, n = 184) were married or living in a permanent relationship. One third of participants (n = 120) self-identified as a non-White minority; most of the minority group self-identified as Black (65%, n = 78) or Hispanic (21.7%, n = 26). Twenty-seven percent of participants were employed part- or full-time (n = 96), and 56.9% (n = 205) had an approved VA PTSD service-connected disability

Measures.

PTSD symptom severity was assessed using the CAPS,[14] a structured interview in which the frequency and severity of each of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms are rated on a scale from 0 to 4. The CAPS has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity.[14,19] For each PTSD symptom, severity is computed as the sum of the frequency and intensity rating, with overall PTSD severity computed by summing scores across the 17 items. An independent doctoral-level psychologist monitored audiotapes of 8.3% of CAPS assessments. The intraclass correlation for PTSD severity was high (r = 0.85). The CAPS was also used to determine PTSD diagnosis; symptom presence was defined using the “1/2 rule” (symptom frequency of at least monthly with at least moderate symptom intensity).[20]

Dissociation was measured using three items from the CAPS: reduction in awareness of surroundings, derealization, and depersonalization. The frequency and intensity of each dissociation item is rated on a scale from 0 to 4, and severity is computed as the sum of frequency and intensity ratings for each dissociation item.

Combat exposure was assessed using the Combat Exposure Scale,[21] a self-report measure that asks participants to rate the frequency of exposure to seven types of combat events, including being surrounded by the enemy, or being in danger of being injured or killed.

Axis-II PDs were established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Version (SCID-P).[22] Monitoring of audiotapes of 25% of SCID-P assessments showed modest agreement for SCID-P diagnoses (kappas = 0.50–0.70).

Procedure.

An institutional review board at each site approved the research protocol, and participants provided written informed consent before study enrollment. Assessment was performed by a master’s- or doctoral-level therapist. All data reported in the current study were collected before the start of treatment.

Data Analysis.

We submitted current severity scores on the 17 DSM-IV CAPS items and the three associated features (reduction in awareness, derealization, and depersonalization) to a LPA. LPA identifies homogenous groups of individuals based on similarity of item responses. It is ideally suited to answer questions about possible subpopulations within a dataset because it simultaneously evaluates all items submitted to the analysis, is hypothesis driven, allows for the evaluation of multiple latent classes (as compared to taxometric analysis which tests for a single class only), and yields fit statistics that permit testing across multiple class solutions. Ideally, when using LPA to evaluate psychopathology, the classes that emerge will be categorically different from one another, rather than differing from one another only on the basis of disorder severity (the latter finding may suggest that the structure of the disorder is more accurately represented by a dimensional latent variable rather than by a categorical latent class).

We tested multiple class solutions, starting with the two-class solution, and added classes to the analysis until the results revealed that doing so was no longer warranted, per model fit statistics. Specifically, we evaluated relative fit of competing models by examining the overall quality and performance of the model (i.e., adequate convergence), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-A),[23] the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT),[24] and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC).[24] Statistically significant BLRT and LMR-A test statistics suggest the model under consideration is preferred over a model with one less class while a non-significant result suggests the model has attempted to extract too many classes and a more parsimonious class solution is preferred; models with relative lower BIC values are also preferred. A recent simulation study[26] suggested that the BLRT and BIC statistics are the most accurate of these statistics in selecting the correct class solution. We also evaluated model entropy, with higher values generally preferred over lower ones. The LPA was conducted using the Mplus 5.1 statistical modeling software.[27]

After determining the best class solution, we used participant class membership as the group variable in ANOVAs (for continuous dependent variables) and logistic regressions (for categorical dependent variables) to evaluate potential group differences in PTSD symptom presentation, rates of Axis II disorder comorbidity, and demographic characteristics. We followed-up significant group differences by examining the pattern of pairwise comparisons.

Results

Latent Profile Analysis.

The two- and three-class solutions yielded adequate overall quality and were further compared with one another, but the four-class solution was rejected because neither the best loglikelihood value for the model nor the p-value associated with the BLRT statistic could be replicated (see Table 1). In addition, the model was rejected because it yielded only a minimal increase in entropy relative to the three-class solution and because the four-class solution suggested that the model added a very small latent class that differed only by severity (not categorically) relative to the three-class solution. The three-class solution was favored over the two-class one given that the BIC was substantially lower, and entropy higher, and because the BLRT p-value was statistically significant, indicating the superiority of the three- over the two-class solution. The LMR-A statistic was inconsistent with the rest of the model evaluation statistics in that it suggested that the three-class solution was not superior to a two-class one; however this result was afforded less weight in model selection given that the LMR-A has been shown to be less robust in selecting the correct class solution relative to the BIC and BLRT.[26]

Table 1.

Fit of Competing Class Models in the Male (Study 1) and Female (Study 2) Samples

| Model | Loglikelihood | BIC | Entropy | LMR-A p-value | BLRT p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Male Sample | |||||

| 2 Class | −15228.495 | 30816 | .82 | < .001 | < .001 |

| 3 Class | −14977.199 | 30437 | .90 | .08 | < .001 |

| 4 Class | −14768.087a | 30142 | .92 | .06 | < .001b |

| Female Sample | |||||

| 2 Class | −11927.510 | 24217 | .93 | < .001 | < .001 |

| 3 Class | −11800.826 | 24087 | .88 | < .001 | < .001 |

| 4 Class | −11730.748a | 24072 | .90 | .13 | < .001 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR-A = Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test; BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

The best loglikelihood value was not replicated, despite increasing the number of random starts. This can be an indication that too many classes were extracted and/or that a local maxima was reached and the parameter estimates may not be reliable or replicable.

The best loglikelihood value for the bootstrapped test was not replicated in 3 out of 5 draws, despite increasing the number of random starts for the test.

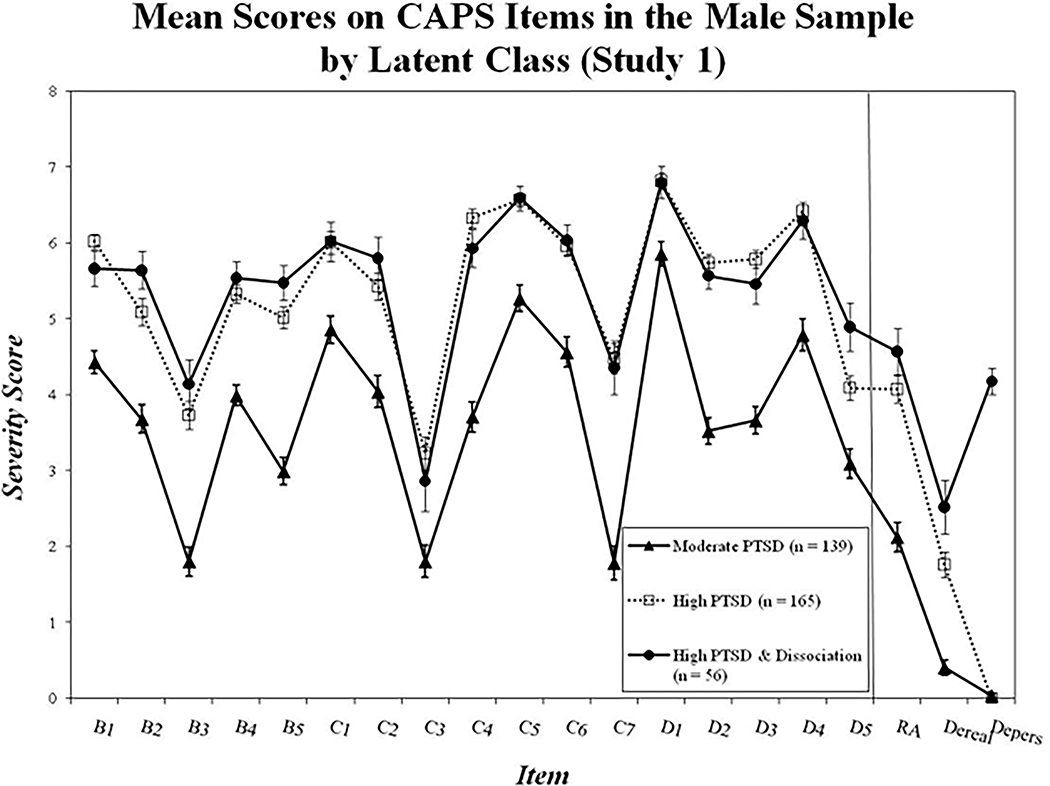

In the three-class solution, mean probability of membership in each class was excellent (.93 for class 1, .96 for class 2, and 1.0 for class 3), implying good discrimination amongst the classes, and 38.6% of the sample were grouped into class 1, 45.8% into class 2, and 15.6% of the sample were grouped into class 3. As shown in Figure 1, class 1 (labeled “Moderate PTSD”) had moderate scores on the PTSD items and low scores on the dissociation items. Class 2 (the “High PTSD” group) had higher scores on the PTSD items and low scores on the dissociation items while Class 3 (the “High PTSD group with Dissociation”) had high scores on the CAPS items and was also defined by uniquely high scores on derealization and depersonalization.

Figure 1:

All items drawn from the CAPS. Significant differences between the High PTSD and the Dissociative groups were observed for D5, derealization, and depersonalization. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; RA = reduction in awareness; dereal = depersonalization; depers = depersonalization.

Group Differences in Psychiatric Symptoms, Trauma Exposure, and Demographic Characteristics.

We next evaluated mean differences in PTSD and dissociation severity scores as a function of latent class membership using ANOVAs. The overall F-test for each item on the CAPS and on PTSD severity (CAPS total score) was significant (all F [2, 357] ≥ 11.04, all p < .001), but follow-up pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s HSD suggested that this was largely due to higher mean severity scores between both high PTSD groups versus the moderate symptom group (all ps < .05). There were three exceptions to this: PTSD criterion D5 (exaggerated startle), depersonalization, and derealization. Specifically, for D5 and derealization, all pairwise comparisons were significant such that the Dissociative group had higher mean scores than the High PTSD group (both ps < .05), which scored higher than the Moderate PTSD group (ps < .001). Mean scores for depersonalization were significantly higher in the Dissociative group compared to the High and Moderate PTSD groups (both ps < .001), which did not differ significantly from each other (p = .88).

Next, we evaluated the pattern of Axis II comorbidity across the latent classes using logistic regression. We did so for Axis II disorders that were prevalent in at least 5% of the full sample. Five PDs met this prevalence criterion: avoidant PD (17.2% of the full sample), obsessive-compulsive PD (20.6%), paranoid PD (18.1%), borderline PD (13.1%), and antisocial PD (8.9%). The logistic regressions revealed overall differences in the prevalence of paranoid and borderline PDs as a function of latent class membership (likelihood ratio χ2 (df = 2, n = 360) = 13.90 and 7.07, p = .001 and .03, respectively), but follow-up pairwise comparisons suggested that in both cases, this was due to a greater percentage of individuals in the High PTSD class meeting criteria for these two PDs relative to individuals in the Moderate PTSD group (both ps < .05). Thus, no PDs were uniquely associated with the Dissociative latent class.

We also examined the extent to which severity of combat exposure might differ as a function of latent class using total scores on the Combat Exposure Scale.[21] The ANOVA revealed the Dissociative class was associated with significantly greater combat exposure severity relative to the Moderate PTSD class, but no differences emerged between the Dissociative and the High PTSD latent classes (overall F [2, 356] = 4.77, p = .009). Finally, we evaluated potential demographic differences among the latent classes and found no group differences for race (dichotomized as minority vs. non-minority; χ2 [df = 2, n = 360] = .62, p = .73) nor age (F [2, 357] = 1.23, p = .29).

Discussion

The aim of this first study was to evaluate if prior evidence for a dissociative subtype of PTSD[10] would be replicated in an independent sample of male Veterans with combat-related PTSD. Results provided evidence of three classes: Moderate and High PTSD classes, which had relatively low levels of dissociation and primarily differed from one another by PTSD severity, and a third group with high PTSD severity and uniquely high scores on derealization and depersonalization. The Dissociative subgroup comprised approximately 15% of the sample, a result that is very similar to prior work suggesting that the dissociative class defined 12% of individuals with PTSD.[10]

Results support the replicability of the dissociative subtype of PTSD when evaluated using the same measure of dissociation (i.e., the CAPS associated features items) in a sample with a similar demographic composition as that reported on by Wolf et al.[10] Given that, we wondered about the generalizability of the dissociative subtype to women; therefore, in Study 2, we evaluated the evidence for a dissociative subtype among women with PTSD who were assessed for dissociation using the Trauma Symptom Inventory.[28]

Study 2 (Female Sample)

Method

Sample.

Participants were 277 female Veterans and 7 female soldiers who participated in a multi-site randomized clinical trial of prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD.[16] All participants had current PTSD according to DSM-IV criteria and a symptom severity of 45 or higher according to the CAPS.[14] Other inclusion criteria were: a clear memory of the index traumatic event; 3 or more months since experiencing trauma; agreement not to receive other psychotherapy for PTSD during treatment; and, if on psychoactive medication, a stable regimen of 2 or more months. Exclusion criteria included current substance dependence (not in remission for at least 3 months), current psychotic symptoms, mania, bipolar disorder, prominent suicidal or homicidal ideation, cognitive impairment, current involvement in a violent relationship, or self-mutilation within the last 6 months.

Mean age of participants was 44.79 (SD = 9.44, range 22 to 78). Most (89.1%, n = 253) had more than a high school education, and 31.7% (n = 80) were married or living as married. Almost half (45.4%, n = 129) self-identified as a non-White minority; most of the minority group self-identified as Black (72.1%, n = 93) or Hispanic (14.0%, n = 17). Almost 40% (n = 111) of participants were working full- or part-time and 22.7% (n = 63) had an approved VA PTSD service connected disability.

Measures.

PTSD symptom severity, PTSD diagnosis, and Axis-II PDs were assessed using the same measures as Study 1. Twenty-five percent of SCID and 12.5% of CAPS interviews were selected for monitoring by a doctoral-level psychologist. Intraclass correlations were .92 for the CAPS and between .65 and .83 for SCID diagnoses. Dissociation was measured using 4 items from the Dissociation Scale on the Trauma Symptom Inventory,[28] a self-report questionnaire that assesses PTSD symptoms and associated features experienced during the past 6 months on a scale from 0 to 3 (never to often). We chose to evaluate 4 items that measured derealization and depersonalization: “feeling like you were outside of your body”; “feeling like you were watching yourself from far away”; “feeling like things weren’t real”; and “feeling like you were in a dream.” We limited the analysis to these 4 items because they are the ones that are most analogous to the derealization and depersonalization items evaluated in Study 1.

Traumatic exposure was assessed using the Life Events Checklist,[14] which measures exposure to 17 types of potentially traumatic events. The number of types of traumatic events each participant directly experienced was calculated as the sum of events that “happened to me.” Exposure to sexual trauma included both sexual assault or other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experience.

Procedure.

An institutional review board at each site approved the research protocol. Clinical assessments were conducted by master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians. All data reported here were collected before treatment.

Data Analyses.

The data analytic approach for Study 2 was identical to that for Study 1 with the exception that the LPA was based on items drawn from two different measures: the 17 core CAPS items (current severity scores) and the 4 items tapping derealization and depersonalization from the Dissociation scale of the TSI.

Results

Latent Profile Analysis.

The two- and three-class solutions yielded acceptable model quality, but the four-class solution resulted in a failure to replicate the best loglikelihood value. This means that the model reached a local solution (i.e., the best solution for the model was not found) and can be an indication that the analysis has attempted to extract too many classes. This led us to reject the four-class solution. Both the two- and three-class solutions yielded significant p-values for the BLRT and LMR-A tests, indicating the superiority of the three-class solution. The three-class solution also achieved a lower relative BIC value, further suggesting that it was the class solution that best fit the data, although entropy was somewhat lower for the three-class solution over the two-class one.

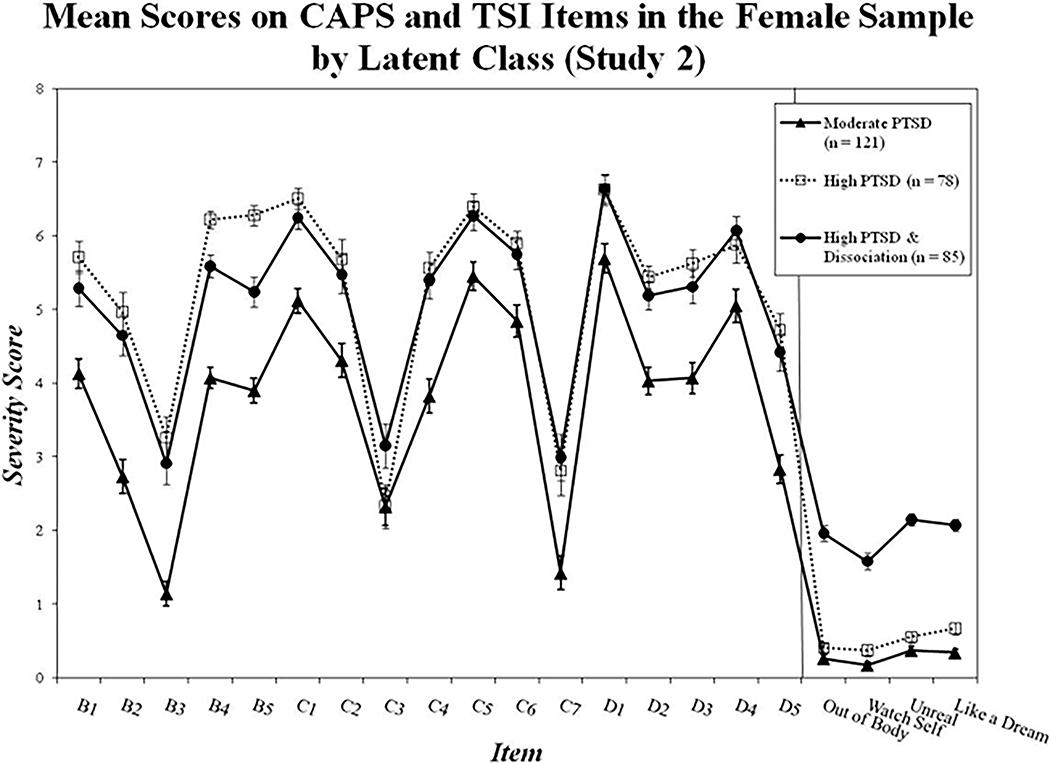

In the three-class solution, the mean probability of class membership was good for each class (.96 for class 1, .91 for class 2, and .98 for class 3) indicating good class discrimination, and participants were classified into groups as follows: 42.6% of the sample were grouped into class 1, defined by moderate PTSD severity and scores at or near zero on the four TSI dissociation items; 27.5% were grouped into class 2, defined by high PTSD severity and scores at or near zero on dissociation; and 29.9% of the sample were classified into group 3, defined by high PTSD severity and uniquely high scores on all 4 dissociation items (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:

PTSD items drawn from the CAPS; dissociation items drawn from the TSI. Possible item range on the CAPS: 0–8; possible item range on the TSI: 0–3. Significant differences between the High PTSD and Dissociative groups were observed for B4, B5, and all dissociation items. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; TSI = Trauma Symptom Inventory; out of body = depersonalization item: “Feeling like you were outside of your body”; watch self = depersonalization item: “Feeling like you were watching yourself from far away”; unreal = derealization item: “Feeling like things weren’t real”; like dream = derealization item: “Feeling like you were in a dream.”

Group Differences in Psychiatric Symptoms, Trauma Exposure, and Demographic Characteristics.

Next, we evaluated the pattern of PTSD and dissociation severity scores across the three latent classes. The overall F-tests comparing the mean PTSD and dissociation severity scores across the groups were statistically significant for each item (all F [2, 281] ≥ 7.61, all p < .001] with the exception of the F-test for PTSD Criterion C3 (amnesia), which just failed to reach the standard threshold for statistical significance (p = .07). Follow-up pairwise comparisons using Tukey’s HSD revealed that in most cases, the High and Dissociative classes had higher scores on PTSD symptoms compared to the Moderate PTSD class (all ps < .05). There were six instances in which the Dissociative class differed from the High PTSD class. Specifically, the High PTSD class scored higher than the Dissociative class (which in turn scored higher than the Moderate PTSD class) on PTSD Criteria B4 (trauma-cued emotional distress) and B5 (trauma-cued physiological reactivity), all ps < .05, while the Dissociative class scored higher than the High PTSD class (and the Moderate PTSD class) on all four TSI items assessing derealization and depersonalization, with the High PTSD group scoring higher than the Moderate PTSD group on one derealization item (“feeling like you were in a dream”) (all ps < 01).

As with the male sample, we also evaluated how prevalence of Axis II disorders differed by latent class for PDs occurring in at least 5% of the full sample. In the female sample, five PDs met this criterion: avoidant (27.1% of the full sample), obsessive-compulsive (21.1%), paranoid (18.0%), schizoid (7.8%), and borderline (23.6%). Logistic regressions revealed two instances (on avoidant and borderline PD) in which there was an overall difference in the frequency of comorbid PD as a function of latent class (likelihood ratio χ2 (df = 2, n = 284) = 8.18 and 25.98, p = .02 and p < .001, respectively); follow-up comparisons revealed, in both instances, the Dissociative class had a higher rate of the comorbid PD than the High or Moderate PTSD classes (both ps < .05), which did not differ from one another (p = .79 and p = .06, respectively). Specifically, 38.8% of the Dissociative class met criteria for avoidant PD (compared to 23.1% and 21.5% of the High and Moderate PTSD groups, respectively) and 42.4% of the Dissociative class met criteria for borderline PD (compared to 21.8% and 11.6% of the High and Moderate PTSD groups, respectively).

We next evaluated how trauma exposure might differ across the three groups using ANOVA. There were no differences between the two high PTSD groups in the total number of trauma types endorsed on the LEC (although both groups were higher than the Moderate PTSD group on this variable; overall F [2, 281] = 7.68, p < .001) nor were there group differences in prevalence of exposure to sexual trauma (sexual trauma was reported by 90.9% of the Moderate PTSD group, 93.6% of the High PTSD group, 95.3% of the Dissociative group, and 93.0% of the full sample; likelihood ratio; χ2 [df = 2, n = 284] = 1.56, p = .46). There were also no differences in prevalence of exposure to combat trauma by group, which was reported by 21.5% of the Moderate PTSD group, 31.2% of the High PTSD group, and 22.4% of the Dissociative group, likelihood ratio χ2 (df = 2, n = 284) = 2.58, p = .28.

Finally, we evaluated potential demographic differences among the three latent classes. Results revealed the three groups did not differ in age (F [2, 281] = 2.43, p = .09). However, the three groups differed in terms of self-identified race (likelihood ratio χ2 (df = 2, n = 284) = 7.79, p = .02). Individuals in the Moderate and High PTSD groups were more likely than the Dissociative group to self-report their race as White (relative to identifying as a racial minority, both ps < .05); 42.4% of the dissociative group reported White racial identity, compared to 57.9% of the Moderate PTSD class and 62.8% of the High PTSD group.

Discussion

The aim of Study 2 was to evaluate whether a dissociative class would be identified in a sample of women with current PTSD who were assessed for dissociation using items assessing derealization and depersonalization from the Dissociation scale of the TSI. Results replicated prior findings and provided further evidence for a distinctly dissociative subgroup, defined by high scores on measures of derealization and depersonalization along with severe PTSD. Unlike the results of Study 1 and prior work,[10] the Dissociative subgroup in this sample did not score significantly higher on any individual PTSD criterion (such as B3, flashbacks, or C3, amnesia) relative to the High PTSD class and was not more likely to have experienced sexual trauma. The high base rate of sexual trauma in this sample (93%) might have obscured group differences in this putative risk variable.

Women in the Dissociative group were more likely to have comorbid diagnoses of avoidant and borderline PDs, relative to the High and Moderate PTSD groups. One interpretation of this is that dissociation is part of a common factor that underlies the high levels of comorbidity between PTSD and these PDs.[29] This may reflect the shared process of trauma exerting broad and negative effects on the development and integration of identity, personality, and consciousness.[2,30]

One question that arises regarding the association between PTSD and borderline PD is whether dissociation serves a similar function in both disorders. Among individuals with borderline PD, dissociation is thought to be associated with self-injurious behavior[31] such that it may serve an analgesic function.[32] It is conceivable that dissociation serves a similar function in response to distressing emotion and trauma-related memories in PTSD (see Lanius et al.[6]) A second question that arises about this association is whether dissociation affects psychotherapy treatment outcome for both PTSD and borderline PD. Dissociation in borderline PD is associated with impaired neuropsychological functioning[33] and appears to inhibit emotional learning in experimental paradigms.[34] Lanius and colleagues[6] have raised concerns that dissociation may have a similar negative impact on psychotherapy outcome in individuals with PTSD. However, applied work evaluating this hypothesis has been equivocal to date,[35–36] as discussed in greater detail by Resick et al.[36] in this issue.

A larger percentage of women (near 30%) were classified into the dissociative class in the female sample as compared to our two male samples (i.e., 12–15%). There are several possible explanations for this difference. First, it is possible that the high base rate of sexual trauma in the sample (93%) led to an increased occurrence of dissociative phenomena. Prior work has provided evidence of a link between dissociation and sexual assault,[10,13,37–38] although the relationship between sexual trauma and dissociation does not appear to be a unique one.

Second, it is possible that women are more prone to dissociation than men. Putnam et al. [8] found a higher likelihood of dissociation in women, but this was confounded by higher likelihood of psychopathology. This may be a factor in our study too, as the higher prevalence of borderline PD in the female sample (24%, compared to 13% in the male sample) may account for the greater percentage of individuals in the dissociative subtype. This idea is further supported by evidence that the prevalence of borderline PD was uniquely high in the female Dissociative group. It will be helpful for future work to evaluate if gender exerts an independent risk for dissociation following traumatic stress because our study was not able to address this question.

Third, it is possible that the way dissociation is assessed accounts for the difference in the percentage of individuals assigned to the Dissociative class. Self-report measures may be more subject to over-endorsement relative to clinician administered interviews, which presumably have greater construct validity when administered by a well-trained clinician. A prior taxometric evaluation[9] using the self-report DES yielded evidence of a similarly sized dissociative group (32%) among male veterans with PTSD as we obtained in Study 2. One possible explanation for the higher proportion of individuals in the dissociative group in those two samples relative to the results of Study 1 and Wolf et al.[10] is that it is a function of the self-report nature of the measures evaluated in Study 2 and by Waelde et al.[9] The TSI Dissociation scale appears to share significant variance with general measures of negative emotionality, dysphoria, and distress[39] such that the scale is accounted for by a latent trauma/dysphoria factor.[40] This raises questions about the specificity of these items to the dissociation construct and increases the risk that high levels of general distress may unduly influence responses to them. Similar concerns have been raised about the specificity and construct validity of the DES.[41]

Summary and Concluding Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with prior work that has provided evidence for the existence of a discrete dissociative subtype of PTSD in a subset of individuals with the disorder. In the two studies reported here and in our prior work,[10] the Dissociative subgroup was defined by symptoms of depersonalization and derealization and comprised approximately 15% of men with PTSD and 30% of women with PTSD. The pattern of trauma, PTSD symptoms, and Axis II disorder correlates differed somewhat from sample to sample, but the overall structure of PTSD and dissociation symptoms was remarkably similar: the Dissociative group was nearly identical to the High PTSD group with respect to overall PTSD symptom severity but was distinguished by marked elevations in derealization and depersonalization.

Together, our results, along with those reported previously,[9, 10] suggest that dissociation is a salient feature of PTSD for a subset of individuals with the disorder. One possible way to reflect this in the diagnostic nomenclature would be to define a dissociative subtype within the PTSD section of the DSM-5. This would help describe an important facet of the heterogeneity in posttraumatic psychopathology and provide a definition and characterization of the phenomenon for future clinical research. For example, establishment of dissociative subtype criteria would allow investigators to replicate work on the clinical and neurobiological correlates of dissociation by increasing the reliability of its assessment. This would also yield improved ability to characterize potential differential rates of dissociation across gender, trauma type, and psychiatric comorbidity. Most importantly, it may have clinical utility if the best treatment for PTSD patients with dissociative symptoms differs from the optimal treatment approach for those without.[36,42] Currently, it is difficult to draw conclusions about such differences because of variability in the definition and measurement of the construct across studies. Clinically, the inclusion of the subtype in the DSM would cue clinicians to assess for dissociation and could inform case conceptualization and treatment planning.

More research is needed to determine the extent to which the core DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD is associated with the dissociative subtype. Our prior study[10] suggested that flashbacks (PTSD Criterion B3) and psychogenic amnesia (PTSD Criterion C3) were defining features of the dissociative subtype of PTSD, but we did not find this in the two samples examined in this study. If DSM-IV PTSD Criteria B3 and C3 are differentially associated with the subtype, then they might be included in the definition of the dissociative subtype and used as a marker for it. However, if there is no specific association between B3 and C3 and the dissociative subtype, then this would suggest that this subgroup is not a “subtype” of PTSD in the traditional sense of the term (i.e., because PTSD-specific criteria would not distinguish the type). Instead, the subtype could be conceptualized as subtype of posttraumatic psychopathology or as a form of PTSD comorbidity (e.g., designated as “PTSD with marked dissociative symptoms”). Future research may help resolve these issues.

This study was limited by the exclusive focus on Veterans and active duty service members. Future work should examine the generalizability of the dissociative subtype to civilian populations. Our assessment of dissociative phenomena was largely limited to symptoms of derealization and depersonalization and this raises questions about how other aspects of dissociation might relate to symptoms of PTSD. It is important for future research to address this question using clinician administered measures of dissociation that provide comprehensive coverage of the pathological end of the spectrum of dissociation. In so doing, it is particularly important to use measures that also show discriminant validity with non-pathological traits, such as capacity for absorption,[41] fantasy proneness, and generalized distress; otherwise, estimates of the prevalence of dissociation and of its structure will be unduly influenced by normative phenomena. This study was also limited in that we had little or no variability in some of the trauma measures in the samples (i.e., exposure to combat in the men, exposure to sexual assault in the women), which made it impossible to determine if the dissociative subgroup was associated with higher likelihood of these types of trauma.

In conclusion, this study replicates prior work in suggesting a subtype structure of the relationship between dissociation and PTSD. It will be helpful for future work to further evaluate the biological and clinical correlates of the dissociative subtype by determining if it is associated with specific genetic variation, neurobiological functioning,[6] and responses to treatment. Improved understanding of the basic structure, function, and correlates of dissociation may ultimately improve our classification of and treatments for trauma-related disorders.

Acknowledgements:

The data reported in this article were drawn from a study funded by grant CSP #494 from the VA Cooperative Studies Program and support from the Department of Defense for CSP #494. However, the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, or any US government agency.

This work was also supported by a VA Career Development Award to Erika J. Wolf.

Footnotes

Trial registration information for CSP #494: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00032617.

References

- 1.Van der Kolk BA, Brown P, van der Hart O. Pierre Janet on post-traumatic stress. J Trauma Stress 1989;2:365–378. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gershuny BS, Thayer JF. Relations among psychological trauma, dissociative phenomena, and trauma-related distress: a review and integration. Clin Psychol Rev 1999;19:631–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman MJ, Resick PA, Bryant RB, et al. Classification of Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiegel D, Cardeña E. The dissociative disorders revisited. J Abnorm Psychol 1991;100:366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginzburg K, Koopman C, Butler LD, et al. Evidence for a dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder among help-seeking childhood sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation 2006;7:7–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam FW, Carlson EB, Ross C,A Anderson G. Patterns of dissociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996;184:673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waelde LC, Silvern L, Fairbank JA. A taxometric investigation of dissociation in Vietnam veterans. J Trauma Stress 2005;18:359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Reardon AF, et al. A latent class analysis of dissociation and PTSD: evidence for a dissociative subtype. Arch Gen Psychiatry, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;174:727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Kolk BA, Pelcovitz D, Roth S, Mandel FS. Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: the complexity of adaptation to trauma. Am J Psychiat 1996;153:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson EB, Dalenberg C, McDade-Montez E. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: recommendations for modifying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). Boston, MA: National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division-Boston, VA; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Foy DW, et al. Randomized trial of trauma-focused group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: results from a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korzekwa MI, Dell PF, Links PS, et al. Dissociation in borderline personality disorder: a detailed look. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation 2009;10:346–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stiglmayr CE, Ebner-Priemer W, Bretz J, et al. Dissociative symptoms are positively related to stress in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008;117:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety 2001;13:132–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weathers FW, Ruscio A, Keane TM. Psychometric Properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment 1999;11:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keane T, Fairbank J, Caddell J, et al. Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessment 1989;1:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Patient Edition (SCID-P. Version 2.0). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. 1st ed. New York: Wiley, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz G Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling 2007;13:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briere J Trauma Symptom Inventory Professional Manual. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Personality disorders associated with full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the U.S. population: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Psychiatr Res 2011;45:678–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herman J. Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodsky BS, Cloitre M, Dulit RA. Relationship of dissociation to self-mutilation and childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1788–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludäscher P, Valerius G, Stiglmayr C, et al. Pain sensitivity and neural processing during dissociative states in patients with borderline personality disorder with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2010;35:177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haaland VØ, Landrø NI. Pathological dissociation and neuropsychological functioning in borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2009;119:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebner-Priemer UW, Mauchnik J, Kleindienst N, et al. Emotional learning during dissociative states in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2009;34:214–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagenaars MA, van Minnen A, Hoogduin KL. The impact of dissociation and depression on the efficacy of prolonged exposure treatment for PTSD. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resick P, Suvak M, Johnides B, et al. The impact of dissociation on PTSD treatment with Cognitive Processing Therapy. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Briere J, Runtz M. Symptomatoloty associated with childhood sexual victimization in a nonclinical adult sample. Child Abuse Negl 1988;12:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu JA, Frey LM, Ganzel BL, Matthews JA. Memories of childhood abuse: dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arbisi PA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, Nelson NW. The concurrent and incremental validity of the Trauma Symptom Inventory in women reporting histories of sexual maltreatment. Assessment 2010;17:406–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder JJ, Elhai JD, North TC, Heaney CJ. Reliability and validity of the Trauma Symptom Inventory with veterans evaluated for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 2009;170:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giesbrecht T, Lynn S, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H. Cognitive processes in dissociation: An analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychol Bull 2007;134:617–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, Lassell LF. An examination of a phase oriented treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]