Abstract

Nitric oxide, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide are three endogenous gasotransmitters that serve a role in regulating normal and pathological cellular activities. They can stimulate or inhibit cancer cell proliferation and invasion, as well as interfere with cancer cell responses to drug treatments. Understanding the molecular pathways governing the interactions between these gases and the tumor microenvironment can be utilized for the identification of a novel technique to disrupt cancer cell interactions and may contribute to the conception of effective and safe cancer therapy strategies. The present review discusses the effects of these gases in modulating the action of chemotherapies, as well as prospective pharmacological and therapeutic interfering approaches. A deeper knowledge of the mechanisms that underpin the cellular and pharmacological effects, as well as interactions, of each of the three gases could pave the way for therapeutic treatments and translational research.

Keywords: gasotransmitter, NO, H2S, TME, cancer chemotherapy

1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the most dreaded diseases and is a major threat to human life. Among different clinical disorders, cancer is the second most common cause of death after cardiovascular diseases (1). Different approaches and strategies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, immunotherapy and small molecule-targeted therapy, have been studied and applied to target and treat cancer (2,3).

Chemotherapeutic drugs work by targeting fast-growing and proliferating cells, leading to cell death and shrinking of the tumors. The conventional cancer chemotherapy, ‘the standard treatment’, is not always successful, even after 50–100 years of research and clinical experience, although cases of lymphocytic leukemia and Hodgkin's lymphoma have been treated successfully in this manner (1). Conventional chemotherapy indiscriminately delivers the toxic anticancer agent to tumors and normal tissues simultaneously (4). Therefore, cancer-selective drug delivery approaches are required to avoid undesirable systemic side effects. One way of tackling these problems is to deliver anticancer drugs selectively to the tumor site (5). One of the different approaches is using gasotransmitters to selectively provide anticancer drugs to the tumor site (6).

The three small, diffusible gaseous mediators nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) serve multiple roles in normal physiology and the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. Several studies have emphasized the roles of NO, CO and H2S in cancer (7–10); however, there are numerous puzzles and controversies. Some studies have demonstrated that these mediators are pro-tumorigenic, while others have reported that they have an antitumorigenic effect (11–13). It is now recognized that these three gases exhibit bell-shaped (also termed ‘biphasic’, ‘bimodal’ or ‘Janus-faced’) pharmacological characteristics in cancer (6). An improved understanding of the complicated pharmacological nature of these mediators has far-reaching consequences. It also tackles some of the difficulties of the field, enabling the development of novel therapeutic techniques based on pharmacologically suppressing mediator production (6). The present review discusses the important roles of NO, CO and H2S in tumor pathophysiology, addressing how different levels of these gases can affect tumor growth, angiogenesis and survival. Furthermore, it highlights the potential therapeutic value of the gasotransmitters in cancer chemotherapy.

2. Chemotherapy

History of chemotherapy

The use of chemicals to treat a disease is called chemotherapy. This therapeutic model was conceptually born in the early 20th century when the German physician Paul Ehrlich adopted chemicals to treat infectious diseases (14,15). Ehrlich stepped into the field of oncology with great ambition, trying to explore de novo pharmacological bullets to shoot cancer cells (16). The net findings of all his experiments were disappointing since none of the proposed drugs worked on cancer cells (17).

Cancer chemotherapy remained indistinct for >30 years, and scientists continued to follow Ehlrich's fishing strategy after his death. Certain researchers studied the effect of mustard gas or its derivatives on bone marrow eradication; an idea that was obtained from using the gases during the First World War (18,19). Others, such as Sidney Farber, used anti-folates, such as aminopterin and 6-mercaptopurine, to treat childhood cancers (20). In 1950, 6-mercaptopurine was selected for a clinical trial investigating the treatment of acute lymphatic leukemia in children. Despite the promising initial results leading to cancer remission, all investigated chemicals had significant adverse effects indicated by quick relapse a few weeks after treatment (21). The chemotherapeutic drug screening mission was continued. By 1964, ~215,000 chemicals, plant derivatives and fermentation products were studied, and several million mice were included in these studies (22). The challenges encountered in the discovery and delivery of the proper anticancer chemotherapeutics were developing a convenient model to reduce the vast repertoire of chemicals into a considerable list that could have efficiency against cancer, obtaining suitable funds to support the suggested studies and treatment modalities, and admission to clinical facilities to examine the impact of the selected substances. Therefore, different organizations, funding agencies and research centers were established to support scientists and oncologists economically, in order to defeat cancer.

After all these chemotherapeutic screening failures, scientists turned the view back, asking what makes cancer cells switch their response to treatment from sensitive to resistant. Scientists examined if it would be better to employ dual chemotherapy rather than the conventional monotherapy approach used, and this idea of using multiple chemical combinations immediately appeared promising. Freireich et al (23) were the first scientists who combined a four-drug regime (vincristine, amethopterin, mercaptopurine and prednisone) to treat leukemia in children. Despite full cancer remission for several months, they observed severe brain metastasis and death, and thus, stopped this chemotherapeutic regimen. The outcome of tetra-combinatorial therapeutic approaches, including mechlorethamine, oncovin, procarbazine and prednisone (MOPP), and mechlorethamine, oncovin, methotrexate and prednisone, in treating Hodgkin's diseases was surprising, as the complete remission rate increased to 80% in the USA (24). Furthermore, ~60% of patients with Hodgkin's treated with MOPP never relapsed (25). MOPP, ‘the miracle’, made the concept of cancer curability possible. Indications from combination chemotherapies in treating certain types of advanced hematological malignancies motivated scientists to consider a similar therapeutic regime for solid tumors; however, the primary method for treating solid tumors was surgery (26). By the early 1970s, the adjuvant chemotherapy approach was introduced, where chemotherapy was used after surgery to target microscopic tumors and reduce cancer recurrence (26). Bonadonna et al (27) introduced the first combinational chemotherapeutic-postoperative approach, called cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil-adjuvant therapy, to treat early-stage breast cancer in women. The concept of combinational adjuvant chemotherapy was popular in the USA. Fisher et al (28) examined L-phenylalanine mustard to target breast cancer and other solid tumors, such as colorectal cancer. Depending on the type and size of the tumor, an additional approach, called neoadjuvant chemotherapy, is currently used. In this approach, chemotherapy is applied before the surgery or the primary therapy (29).

Most, if not all, solid tumors acquire drug resistance after a few cycles of chemotherapy, and thus, an efficient chemotherapeutic approach has not been developed yet. This is mainly due to dynamic phenotypic and genotypic changes in cancer cells and their surrounding microenvironment. Despite the common non-curative effect of chemotherapy, the disease progression-free survival curves have been markedly improved (30). Any effective therapeutic approach requires systematic knowledge regarding the drug's mechanism of action, primary pharmacologic metabolites, the differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and the behavior of cancer cells and their crosstalk with the tumor microenvironment (TME) (31). This knowledge has markedly progressed during the last 20–30 years upon the emergence of novel technical avenues in genomic and proteomic analysis. As a result, novel treatment modalities, such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy, have been introduced and suggested to be applied either separately or in combination with chemotherapy.

Mechanism of action and classification of chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic drugs are clustered into subgroups according to their structure and overall mechanisms of action. Each subgroup is subdivided into several cytostatic drugs, which are used to treat different types of cancer (32). Table SI lists the most prominent types of drugs, their mechanism of action, the targeted cancer types and the number of clinical trials for each drug.

Microenvironment and chemotherapy

In non-hematological malignancy, a tumor is a disorganized, miscommunicated aberrant tissue, where tumor cells are surrounded by stroma and they all interact unsystematically within one unit. The stroma consists of cellular and non-cellular compartments, and altogether they are referred to as the TME. The TME is made up of different types of cells, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), different sub-types of anti- and pro-inflammatory immune cells, adipocytes and tumor-associated vasculature (endothelial cells and pericytes), and extracellular matrix (ECM) (33). These compartments interact with each other and with tumor cells, initiating various biochemical and cellular signals, which drive cancer cell proliferation, invasion and the response to treatment (34). Chemotherapy eliminates and reduces tumor growth primarily, whereas a small population of cancer cells shift their survival machinery and do not respond to the treatment, as they become more aggressive cells, which serve as the source of relapse. The TME has the potential to drive the anti-chemotherapeutic effect of cancer cells by interfering with different survival mechanisms and cellular signaling pathways (35). This is evident in different types of cancer, such as breast and ovarian cancer, in which enriched TME signatures associated with a treatment-resistant phenotype are observed (34). Among the different signatures, the hypoxic nature of the TME decreases the proliferation rate and induces survival of cancer cells, thus reducing their response to chemotherapy (36–38). The hypoxic TME triggers angiogenic switch by inducing aberrant blood vessel formation in cancer, and due to the leaky properties of cancer-associated vasculature, the drugs that circulate in the blood will not be delivered efficiently to the core of the tumor (39,40). Additionally, the pharmacokinetic action of certain chemotherapeutic drugs depends on the availability of free radicals. Therefore, the cytotoxic activity of those drugs is reduced in the absence or presence of low oxygen (O2) levels (40,41).

The architecture of the TME, characterized by its phenotypic plasticity and heterogenic properties, is essential to allow or prevent drug delivery to the tumor (42). The reorganization of the ECM due to the interaction of cancer cells with CAFs and TAMs leads to drug sequestration, preventing them from reaching the cancer cells (34,43,44).

3. Gasotransmitters

In the last decades, three gaseous molecules have been identified as gasotransmitters: NO, CO and H2S. These particular gases are similar to each other in their production and function, but exert their functions in unique ways in the human body (45). NO is produced endogenously in endothelial cells from L-Arg by a family of enzymes, called NO synthases (NOS), in the vasculature, which modulates vascular tone by activating soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) enzyme and producing cyclic GMP (46). Endogenous CO is produced by the enzyme heme oxygenase (HO), which converts free heme to biliverdin (47). CO has a vasorelaxant and an antiproliferative action on vascular smooth muscles cells (VSMCs), making it an important determinant of vascular tone in several pathophysiological conditions (48). H2S is produced endogenously in mammalian tissues from L-cysteine by cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase and another mitochondrial enzyme, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (49). It regulates vascular diameter, and protects the endothelium from oxidative stress, ischemia reperfusion injury and chronic inflammation by activating several K+ channels in VSMCs (50,51). According to Wang et al (52), other molecules, such as sulfur dioxide, methane, hydrogen gas, ammonia and carbon dioxide, are also considered to be potential gasotransmitter candidates, despite the fact that they have not been adequately explored or do not completely fit the diagnostic criteria for endogenous gasotransmitters.

History of gasotransmitters

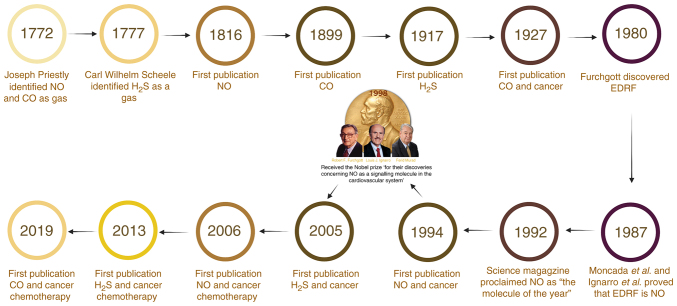

NO was discovered in 1772 by Joseph Priestley as a clear, colorless gas with a half-life of 6–10 sec (53). In 1979, Gruetter et al (54) found that adding NO in a mixture with nitrogen or argon gases into an organ bath vessel containing isolated pre-contracted strips of a bovine coronary artery induces vascular smooth muscle relaxation. In 1980, Furchgott and Zawadzki (55) revealed that endothelial cells produce endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) in response to stimulation by acetylcholine in vessels with intact endothelium. After 7 years and in two unrelated studies, both Ignarro et al (56,57) and Palmer et al (56,57) demonstrated that EDRF is NO. Moncada et al (58) demonstrated that NO is synthesized from the amino acid L-arginine. Earlier, Murad et al (59) reported that nitro vasodilators, such as nitroglycerin (GTN) and sodium nitroprusside, induce vascular tissue relaxation, stimulate sGC expression and increase cGMP levels in tissues. All these studies contributed to the establishment of a signaling molecule in the cardiovascular system. In 1992, the cover of Science magazine proclaimed NO as the molecule of the year (60). Furthermore, 6 years later, Pfizer, Inc. introduced Viagra, a drug that inhibits phosphodiesterase-5 via the NO-cGMP signaling cascade, which revolutionized the management of erectile dysfunction (61). In the same year, the importance of the NO discovery was acknowledged by awarding the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine to Furchgott, Ignarro and Murad (62).

Few discoveries have had the type of impact on biology that NO has had since it was discovered (63). The first scientific article described NO in 1816 (64), while in 1994, Thomsen, et al (48,65) were the first to report a link between NO and cancer action. In 1993, there were >1,000 new publications on the biology of NO. At the end of the 20th century, the rate of NO publications approached a plateau at ~6,000 papers per year, spanning almost every area of biomedicine (63). The number of published articles in PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) reached 58,848 by the end of 2020.

In the late 1200s, a poisonous gas produced by the incomplete combustion of wood similar to CO was described by the Spanish alchemist Arnold of Villanova (66). Between 1772 and 1799, an English chemist, Joseph Priestley, recognized and characterized CO (53). The first scientific article described CO in 1899 (67), and subsequently, the ‘first paper linking CO to cancer was published in 1927 (68). Between 1920 and 1960, Roughton performed several kinetic studies on CO and hemoglobin (69–71). In 1944, he revealed that CO bound to hemoglobin changed the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve, and demonstrated that CO was produced in the body during the metabolism of the hemoglobin molecule (72). Subsequently, Tenhunen et al (73) described and characterized HO as the enzyme responsible for breaking down heme in the body, demonstrating that heme catalysis resulted in the subsequent release of CO and free iron as by-products.

H2S was first discovered in 1777 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele (74), and the first paper related to H2S was published in 1917 (75). The importance of H2S in cell physiology was highlighted in the mid-1990s, and the first link between H2S and cancer was reported in 2005. H2S at physiological concentrations can reduce the apoptotic effects of chemopreventative drugs and play an important role in the response of colonic epithelial cells of the human adenocarcinoma cell line HCT116 to both beneficial and toxic chemicals (76). It is clear that H2S, similar to other endogenous gases, has now been identified as a gasotransmitter (77). It was initially regarded as highly poisonous in the environment; however, this perception has changed as a growing number of studies have illustrated H2S as a cytoprotective and cardioprotective agent (78,79). Fig. 1 depicts a timeline of important scientific developments in the history of gasotransmitter research and therapeutic usage.

Figure 1.

Timeline of key scientific advances during the history of gasotransmitters research and its therapeutic use. CO, carbon monoxide; EDRF, endothelium-derived relaxing factor; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; NO, nitric oxide.

Role of NO in cancer

NO is a small biomolecule that exerts different effects on tumor growth and invasion. It is a pleiotropic regulator and serves essential roles in various intercellular or intracellular processes, including vasodilatation, neurotransmission and macrophage-mediated immunity (7). Vascular endothelial cells can synthesize NO from L-arginine, and this biosynthetic pathway has been thoroughly documented in numerous other cell types, including nervous and immune cells (80,81). It can display a cytotoxic property at higher concentrations as generated by activated macrophages and endothelial cells (7). A total of three different isoforms of the NOS family synthases have been identified: Endothelial NOS (eNOS), neuronal NOS (nNOS) and inducible NOS (iNOS). The gene symbol nomenclatures are NOS1 for nNOS, NOS2 for iNOS and NOS3 for eNOS (7). However, the role of NO in cancer biology, particularly in breast cancer, only started to be elucidated in 1994 (82). It has been detected that NOS expression is increased in various types of cancer, such as breast, cervical, brain, laryngeal, and head and neck cancer (83) (Table I). NO exhibits a pro- or antitumorigenic effect (84). NO appears to enhance tumor growth and cell proliferation at measurable concentrations in different clinical samples from different cancer types (85).

Table I.

Studies on the involvement of NO, H2S and CO synthesis enzymes in the modulation of cancer.

| First author/s, year | Gasotransmitters | Enzyme | Type of cancer | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaltoma, 2001, Aaltomaa, 2000, Bhowmick and Girotti, 2014, Coulter, 2010, Cronauer, 2007, Erlandsson, 2018, McCarthy, 2007, Fahey and Girotti, 2015, D'Este, 2020, Ryk, 2015, Uotila, 2001 | NO | iNOS | Prostate | (170–180) |

| Abdelmagid, 2011, Abdelmagid and Too, 2008, Ambs and Glynn, 2011, Alalami and Martin, 1998, Basudhar, 2017, Bentrari, 2005, Bing, 2001, Deepa, 2013, Duenas-Gonzalez, 1997, Evig, 2004, Flaherty, 2019, Garrido, 2017, Hsu, 2000, Kanugula, 2014, Kotamraju, 2007, López-Sánchez, 2020, Loibl, 2005a, Lahiri and Martin, 2004, Oktem, 2004, Martin, 1999, Nafea, 2020, Oktem, 2006, Zeybek, 2011, Walsh, 2016, Wink, 2015, Tschugguel, 1999 | Breast | (181–206) | ||

| Abadi and Kusters, 2013, Chen, 2006, Doi, 1999, Goto, 1999, Goto, 2006, Hirst and Robson, 2010, Hirahashi, 2014, Huang, 2012, Ikeguchi, 2002, Jun, 1999, Jung, 2002; Rafiei, 2012, Rajnakova, 2001, Zhang, 2011, Sawa, 2008, Shen, 2004, Son, 2001, Song, 2004 | Gastric | (207–224) | ||

| Ambs, 1998b, Bing, 2001, Bocca, 2010, Dabrowska, 2018, Deepa, 2013, Narayanan, 2004, Narayanan, 2003, Kwak, 2000, Kapral, 2015, Puglisi, 2015, Williams, 2003, Tong, 2007; Sasahara, 2002, Shen, 2015, Spiegel, 2005 | Colon | (187,188,225–237) | ||

| Eijan, 2002, Hosseini, 2006, Klotz, 1999, Koskela, 2012, Langle, 2020, Lin, 2003, Ryk, 2010, Ryk, 2011b, Wolf, 2000, Sandes, 2005, Sandes, 2012 | Bladder | (238–248) | ||

| Jung, 2002, Ambs and Harris, 1999, Chung, 2003, Cianchi, 2004, Cianchi, 2003, Fransen, 2005, Gallo, 1999, Ropponen, 2000, Zafirellis, 2010, Wang, 2004 | Colorectal | (217,249–257) | ||

| Delarue, 2001, Hu, 1998, Li, 2014, Liu, 1998, Liu, 2010, Zhang, 2014a, Ye, 2013, Sim, 2012 | Lung | (258–265) | ||

| Franco, 2004, Kong, 2001, Kong, 2002, Wang, 2016a, Vickers, 1999, Takahashi, 2008 | Pancreatic | (266–271) | ||

| Chen, 2005, Dong, 2014, Jiang, 2015, Lee, 2007, Ryu, 2015, Sowjanya, 2016 | Cervical | (272–277) | ||

| Li, 2017b, Malone, 2006, Martins Filho, 2014, Raspollini, 2004, Zhao, 2016, Xu, 1998, Trinh, 2015, Sanhueza, 2016b | Ovarian | (278–285) | ||

| Jayasurya, 2003 | Nasopharyngeal | (286) | ||

| Lukes, 2008 | Tonsillar | (287) | ||

| Soler, 2000 | Thyroid | (288) | ||

| Rafa, 2017 | Colitis | (289) | ||

| Amasyali, 2012, Klotz, 1999, Lin, 2003, Polat, 2015, Ryk, 2011a | eNOS | Bladder | (240,243,290–292) | |

| Abedinzadeh, 2020, Brankovic, 2013, Diler and Oden, 2016, Fu, 2015, Medeiros, 2003, Medeiros, 2002a, Medeiros, 2002b, Nikolic, 2015, Marangoni, 2006, Martin, 1999, Polytarchou, 2009, Re, 2011, Re, 2018, Ziaei, 2013, Zhao, 2014, Yu, 2013, Wu, 2014, Safarinejad, 2013, Sanli, 2011 | Prostate | (200,293–310) | ||

| Bayraktutan, 2020, Cheon, 2000, Fujita, 2010, Kocer, 2020, Peddireddy, 2018 | Lung | (311–315) | ||

| Chen, 2018, Crucitta, 2019, Basaran, 2011, Hao, 2010, Hefler, 2006, Kafousi, 2012, Lahiri and Martin, 2004, Loibl, 2006, Loibl, 2005b, Lu, 2006, Mortensen, 1999a, Mortensen, 1999b, Oktem, 2006, Martin, 2000b, Ramirez-Patino, 2013, Zintzaras, 2010, Zhang, 2016a, Zeybek, 2011 | Breast | (198,202,203,316–330) | ||

| Carkic, 2020, Karthik, 2014 | Oral | (331,332) | ||

| Chen, 2014, Mortensen, 2004, Penarando, 2018, Yeh, 2009 | Colorectal | (333–336) | ||

| Dabrowska, 2018 | Colon | (227) | ||

| Hefler, 2002 | Ovarian | (337) | ||

| Doi, 1999, Krishnaveni, 2015, Wang, 2005, Tecder Unal, 2010 | Gastric | (209,338–340) | ||

| de Fatima, 2008 | Renal | (341) | ||

| Lukes, 2008 | Tonsillar | (287) | ||

| Hung, 2019, Waheed, 2019 | Uterine and cervical | (342,343) | ||

| Riener, 2004 | Vulvar | (344) | ||

| Wang, 2016b | Pancreatic | (345) | ||

| Yanar, 2016 | Larynx | (346) | ||

| Chen, 2013 | nNOS | Neural stem cell | (347) | |

| de Fatima, 2008 | Renal | (341) | ||

| Karihtala, 2007 | Breast | (348) | ||

| Lewko, 2001 | Lung | (349) | ||

| Ahmed, 2012, Al Dhaheri, 2013, Avtandilyan, 2018, Bani, 1995, Avtandilyan, 2019, Alagol, 1999, Bhattacharjee, 2012, Cendan, 1996a, Cendan, 1996b, Chakraborty, 2004, Coskun, 2003, Coskun, 2008, Dave, 2014, De Vitto, 2013, Deliconstantinos, 1995, Demircan, 2020, Duan, 2014, El Hasasna, 2016, Engelen, 2018, Erbas, 2007, Gaballah, 2001, Gajalakshmi, 2013, Ganguly Bhattacharjee, 2012, Ganguly Bhattacharjee, 2014, Gaspari, 2020, Guha, 2002, Gunel, 2003, Kampa, 2001, Khalkhali-Ellis and Hendrix, 2003, Konukoglu, 2007, Kumar and Kashyap, 2015, Lahiri and Martin, 2009, Lee, 2014a, Hewala, 2010, Finkelman, 2017, Jadeski, 2002, McCurdy, 2011, Metwally, 2011, Mishra, 2020, Nakamura, 2006, Negroni, 2010, Martin, 2000a, Pervin, 2001b, Pervin, 2007, Martin, 2003, Nath, 2015, Pance, 2006, Parihar, 2008, Pervin, 2001a, Pervin, 2008, Pervin, 2003, Punathil, 2008, Radisavljevic, 2004, Rashad, 2014, Ray, 2001, Reveneau, 1999, Ridnour, 2012, Zhu, 2015, Zheng, 2020, Zeillinger, 1996, Wang, 2010, Thamrongwittawatpong, 2001, Toomey, 2001, Salaroglio, 2018, Sen, 2013a, Sen, 2013b, Shoulars, 2008, Simeone, 2003, Simeone, 2002, Simeone, 2008, Singh and Katiyar, 2011, Smeda, 2018, Song, 2002, Switzer, 2012, Switzer, 2011 | Non- specific | Breast | (350–424) | |

| Ai, 2015, Babykutty, 2012, Bessa, 2002, Cendan, 1996a, Chattopadhyay, 2012b, Edes, 2010, Ishikawa, 2003, Jarry, 2004, Jenkins, 1994, Jeon, 2005, Kim, 2020, Kopecka, 2011, Liu, 2003, Liu, 2008, Mojic, 2012, Millet, 2002, Oláh, 2018, Prevotat, 2006, Rao, 2004, Rao, 2006, Riganti, 2005, Wang and MacNaughton, 2005, Xie, 2020, Wenzel, 2003, Williams, 2001, Voss, 2019, Tesei, 2007, Thomsen, 1995, Stettner, 2018 | Colon | (357,425–452) | ||

| Ambs, 1998, Cembrzynska-Nowak, 1998, Cembrzyńska-Nowak, 2000, Chen, 2019b, Deliu, 2017, Fu, 2019, Fujimoto, 1997, Gao, 2019a, Hwang, 2017, Kaynar, 2005, Koizumi, 2001, Munaweera, 2015, Maciag, 2011, Maiuthed, 2020, Lee, 2006; Liaw, 2010, Liu, 2018, Luanpitpong and Chanvorachote, 2015, Muto, 2017, Masri, 2010, Masri, 2005, Matsunaga, 2014, McCurdy, 2011, Powan and Chanvorachote, 2014, Punathil and Katiyar, 2009, Zhou, 2000, Zhou, 2020, Zhang, 2014, Yongsanguanchai, 2015, Wongvaranon, 2013, Saisongkorh, 2016, Saleem, 2011, Sanuphan, 2013, Sanuphan, 2015, Su, 2010, Suzuki, 2019, Szejniuk, 2019 | Lung | (386,453–488) | ||

| Arif, 2010, Beevi, 2004, Korde Choudhari, 2012, Patel, 2009 | Oral | (489–492) | ||

| Brankovic, 2017, El-Mezayen, 2012, Gao, 2019b, Gao, 2019c, Jiang, 2013, Krzystek-Korpacka, 2020, Liu, 2004, McIlhatton, 2007, Moochhala, 1996, Muscat, 2005, Mandal, 2018, Yagihashi, 2000, Yu, 2005, Wei, 2008, Siedlar, 1999 | Colorectal | (493–507) | ||

| Arora, 2018, Atala, 2019, Dillioglugil, 2012, Della Pietra, 2015, Huh, 2006, Laschak, 2012, Lee, 2009; | Prostate | (94,152,176,508–519) | ||

| McCarthy, 2007, Rezakhani, 2017, Royle, 2004, Wang, 2007, Tan, 2017, Thomas, 2012, Siemens, 2009, Soni, 2020 | ||||

| Caneba, 2014, El-Sehemy, 2013, El-Sehemy, 2016, Kielbik, 2013, Leung, 2008, Thomsen, 1998, Salimian Rizi, 2015, Stevens, 2010 | Ovarian | (520–527) | ||

| Camp, 2006, Chen, 2020; Fujita, 2014, Fujita, 2019, Zhou, 2009, Wang, 2003, Wang and Xie, 2010, Thomas, 2002, Stewart, 2011, Sugita, 2010 | Pancreatic | (528–537) | ||

| Caygill, 2011, Sun, 2013 | Esophageal | (538,539) | ||

| Gecit, 2012, Gecit, 2017, Jansson, 1998, Kilic, 2006, Khalifa, 1999, Morcos, 1999, Wang, 2001, Thiel, 2014, Saygili, 2006 | Bladder | (540–548) | ||

| Bakan, 2002, Dincer, 2006, Holian, 2002, Eroglu, 1999, Koh, 1999, Oshima, 2001, Rajnakova, 1997, Yao, 2015, Sang, 2011, Sang, 2010 | Gastric | (549–558) | ||

| Li, 2017b, Muntane, 2013; Sayed-Ahmad and Mohamad, 2005 | Liver | (559–561) | ||

| Li, 2017a, Park, 2003, Wei, 2011, Sudhesh, 2013, Sundaram, 2020 | Cervical | (562–566) | ||

| Menendez, 2007, Yang, 2016 | Bone | (567,568) | ||

| Giusti, 2003, Ragot, 2015 | Thyroid | (569,570) | ||

| Gallo, 1998, Kawakami, 2004, Wu, 2020, Utispan and Koontongkaew, 2020 | Head and neck | (571–574) | ||

| Taysi, 2003 | Larynx | (575) | ||

| Thomsen, 1994, Sanhueza, 2016 | Gynecological | (65,576) | ||

| Chattopadhyay, 2012a, Dong, 2019, Li, 2020, Lv, 2014 | H2S | CSE, CBS and 3-MST | Breast | (577–580) |

| Choi, 2012, Kawahara, 2020b, Sekiguchi, 2016, Wang, 2019, Ye, 2020, Zhang, 2015 | Gastric | (126,581–585) | ||

| Chattopadhyay, 2012b, Chen, 2019a, Cai, 2010, Hale, 2018, Hong, 2014, Kodela, 2015, Rose, 2005, Oláh, 2018, Szabo, 2013, Chen, 2017 | Colon | (76,113,428,440,586–591) | ||

| Chen, 2017, Elsheikh, 2014, Faris, 2020, Malagrinò, 2019, Sakuma, 2019 | Colorectal | (591–595) | ||

| Liu, 2017 | Bladder | (596) | ||

| Pei, 2011, Liu, 2016 | Prostate | (96,597) | ||

| Wang, 2020 | Lung | (110) | ||

| Zhang, 2016 | Oral | (598) | ||

| Zhuang, 2018 | Bone | (599) | ||

| Xu, 2018 | Thyroid | (600) | ||

| Huang, 2020, Kawahara, 2017, Kim, 2018, Kourti, 2019, Lee, 2014 | CO | HO | Breast | (601–605) |

| Kawahara, 2020a, Kawahara, 201 | Ovarian | (606,607) | ||

| Khasag, 2014, Liptay, 2009, Nemeth, 2016, Shao, 2018, Shirabe, 1970, Zarogoulidis, 2012 | Lung | (608–613) | ||

| Lian, 2016 | Gastric | (614) | ||

| Lv, 2019, Yin, 2014 | Colorectal | (615,616) | ||

| Nitta, 2019 | Testicular | (617) | ||

| Oláh, 2018 | Colon | (440) | ||

| van Osch, 2019 | Bladder | (618) | ||

| Vítek, 2014 | Pancreatic | (619) |

3-MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; CBS, cystathionine-β-synthase; CO, carbon monoxide; CSE, cystathionine-γ-lyase; eNOS, endothelial NOS; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; HO, heme oxygenase; iNOS, inducible NOS; nNOS, neuronal NOS; NO, nitric oxide.

In contrast to conventional signaling molecules that act by binding to specific receptor molecules, NO exerts its biological actions via a wide range of chemical reactions (86). The NO concentration and minor differences in the composition of the intracellular and extracellular environment determine the exact reactions attained. Under normal physiological conditions, cells produce small but significant amounts of NO, contributing to the regulation of anti-inflammatory effects and its antioxidant properties (83). However, in tissues with a high NO output, iNOS is activated, and nitration (addition of NO2), nitrosation (addition of NO+) and oxidation will be dominant (87). The interaction of NO with O2 or superoxide (O2−) results in the formation of reactive nitrogen species (RNS). The RNS, dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) and peroxynitrite (ONOO), can induce two types of chemical stresses: Nitrosative and oxidative (88). N2O3 effectively nitrosates various biological targets to yield potentially carcinogenic nitrosamines and nitrosothiol derivatives, and N-nitrosation may have essential implications in the known association between chronic inflammation and malignant transformation (88). O2− and NO may rapidly interact to produce the potent cytotoxic oxidants ONOO− and its conjugated acid, peroxynitrous acid. In natural solutions, ONOO is a powerful oxidant, oxidizing thiols or thioethers, nitrating tyrosine residues, nitrating and oxidizing guanosine, degrading carbohydrates, initiating lipid peroxidation, and cleaving DNA, which has important implications in cancer (83).

Effect of NO on the TME

The effects of NO in a multistage model of cancer have been reported previously, it can drive angiogenesis, apoptosis, the cell cycle, invasion and the metastatic process (83,85). NO also serves a role in cellular transformation, the onset of neoplastic lesion formation, and the monitoring of invasion and colonization throughout metastasis (89). Therefore, understanding its role in promoting TME elements is crucial as it will reduce the ambiguity, and aid the development of NO-based cancer therapeutics, which will be effective in the prevention and treatment of a range of human cancer types.

The TME is characterized by hypoxia and acidity. Small pH drops (−0.6 U) favor the production of bioactive NO from nitrite, as evidenced by a higher degree of cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent vasorelaxation in arterioles. A small dose of nitrite may make tumors more sensitive to radiation, resulting in a considerable growth delay and improved survival in mice (90). Therefore, low pH has been revealed to be an ideal setting for tumor-selective NO generation in response to nitrite systemic injection (90). The generation of NO by iNOS inhibits C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 expression in melanoma cells, resulting in a protumorigenic TME (91). Furthermore, eNOS upregulation in the TME reduced both the frequency and size of tumor implants in a surgical model of pancreatic cancer liver metastasis (92) and the influence of NO on tumor cell protease expression since tumor cell anoikis and invasion are both regulated by myofibroblast-derived matrix. Within tumor cells, eNOS-dependent downregulation of the matrix protease cathepsin B was detected, and cathepsin B silencing reduced tumor cell invasiveness in a manner comparable to eNOS upregulation. Therefore, an NO gradient within the TME influences tumor progression through orchestrated molecular interactions between tumor cells and stroma.

The role of NO in the complex interactions between the TME and the immune response is a good example of how complicated the molecular and cellular mechanisms determining the involvement of NO in cancer biology are. Although the activities of NO in the TME are varied and context-dependent, the evidence suggests that NO is an immunosuppressive mediator (93). By targeting tumors in a cell nonautonomous manner, S-nitroso glutathione (GSNO), a NO donor, reduced the tumor burden in a mouse model of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Both the abundance of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages and protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase expression were decreased by GSNO, indicating that NO influences TAM activity. GSNO also reduced IL-34, indicating that TAM differentiation was suppressed. This demonstrates the importance of NO in CRPC tumor inhibition via the TME (94).

Role of H2S in cancer

H2S is a novel gasotransmitter, which regulates cell proliferation and other cellular functions (95). It has been revealed that H2S serves an essential role as a signal molecule in regulating cell survival (95). It seems paradoxical that, on one hand, H2S acts as a physiological intercellular messenger to stimulate cell proliferation, and on the other hand, it may display cytotoxic activity (96). H2S, at physiologically relevant concentrations, hyperpolarizes the cell membrane, regulates cell proliferation, relaxes blood vessels and modulates neuronal excitability (95). Increased expression of various H2S-producing enzymes in cancer cells of different tissues has been reported, and novel roles of H2S in the pathophysiology of cancer have emerged (9). This is mainly observed in some cancer types, such as breast, lung, gastric, colorectal, bladder, prostate, oral, bone and thyroid cancer, where the malignant cells both express high levels of CBS and produce increased amounts of H2S, which results in enhanced tumor growth and spread by stimulating cellular bioenergetics, activating proliferative, migratory and invasive signaling pathways, and enhancing tumor angiogenesis (97), as indicated in Table I, which highlights the research on the involvement of NO, H2S, and CO production enzymes in cancer regulation. Importantly, in preclinical models of these cancer types, either pharmacological inhibition or genetic silencing of CBS was sufficient to suppress cancer cell bioenergetics in vitro, and to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis in vivo (9,98). This enhances the antitumor efficacy of frontline chemotherapeutic agents, providing a strong rationale for the development of CBS-targeted inhibitors as anticancer therapies (99). However, the observation that inhibition of H2S biosynthesis exerts anticancer effects is contradicted by another study which demonstrated that increasing H2S with exogenous donors also exerts antitumor actions (100). H2S stimulates the cytoprotective PI3K-AKT, p38-MAPK and nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NRF2) signaling pathways when present at low concentrations (101). Sulfhydration partially promotes a number of biological functions of H2S, including ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel opening (101). At physiological concentrations, H2S can also serve a role in stimulating the cellular bioenergetic function by donating electrons to the mitochondrial electron transport chain at complex II, leading to increased mitochondrial levels of cyclic AMP (102). At higher concentrations, H2S inhibits oxidation of cytochrome c, which results in disruption of mitochondrial electron transport, and it can also exert pro-oxidant and DNA-damaging effects (103).

Effect of H2S on the TME

H2S acts as a gaseous signaling molecule and is endogenously generated by three H2S-producing enzymes, namely CBS, cystathionine γ-lyase and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase. Imbalances in H2S-producing enzymes as well as H2S levels are associated with malfunctional H2S metabolism, which has been increasingly associated with several human pathological disorders (104). Several cancer cell lines and specimens exhibit upregulation of one or more of the H2S-synthesizing enzymes, and this aberrant expression is suggested to be a tumor enhancer (105). By modulation of the expression of the H2S-producing enzyme, the amount of tumor-derived H2S is altered, thereby modifying the TME and affecting tumor expansion and metastasis (106).

Numerous mechanisms contribute to the pro-tumor effect of H2S, including the induction of angiogenesis, regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics, acceleration of cell cycle progression and anti-apoptotic functions (107). Furthermore, hypoxia is a common feature of the TME in a number of solid tumors, which affects the level of H2S by preventing H2S catabolism and consequently stimulating cystathionine γ-lyase gene expression (107). Furthermore, under the influence of hypoxia in the microenvironment, the levels of H2S-producing enzymes are upregulated, and the H2S-producing enzymes are transferred toward the mitochondria, which results in increased H2S production (106). Angiogenesis, which is an important process in cancer progression, is stimulated by paracrine signaling between stroma in the TME and epithelial tumor cells (108).

Previous evidence has demonstrated that H2S is an endogenous stimulator of ischemic-induced angiogenesis by promoting the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)-α via activation of different pathways, including the VEGFR2/mTOR and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (105,109,110). H2S appears to support tumor cell proliferation by increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (a critical growth factor in angiogenesis) expression in kidney and ischemic tissues (111,112). An in vivo study conducted on nude mice revealed that silencing of CBS expression markedly decreased tumor growth. The researchers concluded that the reduction in tumor growth was associated with both the suppression of cancer cell signaling and metabolism, as well as the paracrine mechanism in the tumor environment (113).

In colon cancer, CBS-derived H2S promotes angiogenesis and vasorelaxation, thereby supporting tumor growth (113). In ovarian cancer, CBS knockdown reduces the number of blood vessels, resulting in tumor growth (97). Taken together, these results indicate that CBS serves an essential role in promoting angiogenesis and tumor growth. Therefore, CBS could be a promising molecular target for cancer therapy. Recently, researchers have developed a novel strategy to improve chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer by remodeling the TME through reduction of the high levels of H2S in colon tissues using copper iron oxide nanoparticles (114). Another strategy for cancer treatment is destroying the tumor metabolism symbiosis. This method successfully affects cancer cells with minimum impairment to healthy cells by using a zero-waste zwitterion-based H2S-driven nanomotor that generates acidosis in cancer cells within the TME, and consequently, the tumor growth will be suppressed (115).

One of the important characteristics of cancer cells is the acidic microenvironment (reduced intracellular pH) due to accumulation of lactic acid that results from a high rate of glycolysis. H2S donors trigger the activation of cellular transporters, such as glutamine transporter-1 (GLT-1) and ATP-binding cassette transporter A1, which directly regulates the aerobic glycolysis, which is a metabolic indicator of cancer (116). Nevertheless, activation of GLT-1 has both a promoting and an inhibiting effect depending on the cancer cell type, and thus, further studies are required to clarify the consequent responses (8).

It has been demonstrated that most cancer cells exhibit increased uptake of glucose and high lactate production, known as the Warburg effect, due to glycolysis that causes the acidic TME, which enhances tumor progression (117). Previous studies have demonstrated that continuous exposure of cancer cells to a low concentration of H2S results in inhibition of cancer progression. This anticancer effect is mainly due to an increase in metabolic lactic acid production by H2S and diminishes the pH regulatory system, which consequently leads to intense intracellular acidification and eventually drives cancer cell death (107,118).

Within the TME, there are key proteins and enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinase, adhesive enzymes (E-cadherin) and integrins, which serve an essential role in the migration and metastasis of cancer cells (119,120). Tumor cells that enter the stroma within the TME after detaching from the main tumor move into the blood vessels and ultimately reach the other organs in the body (121). H2S donors have been used in different studies and have been demonstrated to successfully prevent migration and invasion by decreasing proteins and enzymes involved in migration and invasion in different cancer types (8,122,123). For example, it has been reported that treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma cells with 600–1,000 µM sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS), which is an H2S donor, efficiently reduces migration and invasion in a concentration-dependent manner via modulation of the EGFR/ERK/MMP-2 and PTEN/AKT signaling pathways (124). Similarly, NaHS treatment prevents migratory activity in thyroid cancer cells by deactivating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways (125). Furthermore, NaHS reduces the MMP-2 protein levels in gastric cancer (126). Additionally, H2S serves a role in a different stage of cancer development and is involved in modulation of the TME, which regulates the rate of cancer progression and the effectiveness of therapy (106).

Role of CO in cancer

CO is best recognized for being a toxic gas produced by the burning of fossil fuels. On the one hand, CO poisoning is associated with high mortality rates, and thus, it attracts a lot of attention (127). On the other hand, CO has been conclusively demonstrated to be a gasotransmitter with physiological activities in mammals (128,129). CO is now accepted as a potential therapeutic agent along with its physiological roles and has entered multiple clinical trials (130,131). CO is produced in all cells by HO-1 and HO-2 (132). Each possesses strong cytoprotective functions for the cell, evidenced by the fact that the absence of either, particularly the stress-response isoform HO-1, is detrimental to the cell and organism (133,134). The inducible HO isoform (HO-1) can be upregulated in response to various stimuli, including heme, oxidative stress, ultraviolet irradiation, heat shock, hypoxia and NO (135). The constitutive HO isoform (HO-2) is expressed in several tissues, including the brain, kidney, liver and spleen (6). Low CO concentrations also activate KATP channels and influence various intracellular kinase pathways, including the PI3K-AKT and p38 MAPK signaling pathways (128). CO exerts adverse biological effects at higher concentrations, which, in vivo, are mainly attributed to the binding of CO to hemoglobin. The resulting carboxyhemoglobin reduces the O2-carrying capacity of the blood and leads to tissue hypoxia. In vitro, CO inhibits mitochondrial electron transport by irreversibly inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase (128).

Cellular and animal pharmacological experiments suggest numerous therapeutic indications where HO-1 or CO administration imparts benefits in treating conditions such as sepsis, bacterial infection, cancer, inflammation, circadian clock regulation, stroke, erectile dysfunction and heart attack (131). Some of the best-characterized physiological effects of CO include anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, anti-apoptotic and anticoagulative responses. By contrast, at higher concentrations, CO becomes cytotoxic (136). In contrast to NO, the cytoprotective and cytotoxic effects of CO are intimately intertwined. For example, a low level of CO-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial activity, followed by a slight increase in intracellular reactive O2 species production, is important in CO-mediated cytoprotective signaling events (137,138). In a way, the cytoprotective effects of CO resemble the protective effects of pharmacological preconditioning. A short, relatively mild insult triggers a secondary cytoprotective phenotype via activation of the prototypical antioxidant response element NRF2-related factor. Thus, a protective cellular phenotype is maintained in the cell for a long time after CO has already been cleared from the biological system (6).

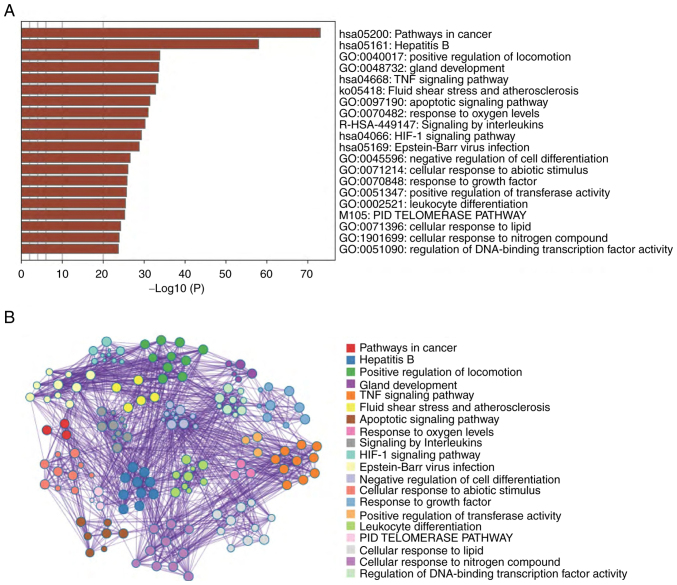

Gasotransmitter signaling significance

To highlight the significance of gasotransmitter signaling cascades in tumor growth and the chemotherapeutic response, network analysis approaches were utilized to identify the gasotransmitter-tumor signaling signature. Utilizing the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science (https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/) databases, ~127 candidates (genes and proteins) were identified, which were significantly related to the gasotransmitters and tumorigenesis simultaneously. Using the selected list of candidates, the present network analyses were applied using the Enrich R (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) and Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html#/main/step1) databases to identify all possible genes, proteins and pathways that may represent tumor-gasotransmitters interrelated signaling. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the most relevant enriched pathways in the present analysis were ones related to cancer, which in turn, justifies the relevance and accuracy of the selected candidate list and highlights the significance of gasotransmitter signaling cascades in tumor development and growth. Additionally, different essential cellular signaling pathways were significantly enriched, such as the ‘positive regulation of locomotion’, ‘TNF signaling pathway’, ‘apoptotic signaling pathway’ and ‘HIF-1 signaling pathway’. These pathways serve an essential role in driving the fate of cancer cells and their response to different treatment modalities (139). Therefore, it is reasonably relevant to investigate the crosstalk between gasotransmitters and tumor cells.

Figure 2.

Pathway enrichment analysis. (A) Bar graph of enriched pathways across input gene lists, the top 20 clusters are arranged according to the degree of significance (P-value). (B) Network of the top 20 enriched pathways. The members with the best P-value from each of the 20 clusters were selected with the constraint that there are not >15 members per cluster and not >250 terms in total. Each node represents an enriched member and is colored accordingly. GO, Gene Ontology; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor 1; PID, primary immunodeficiency.

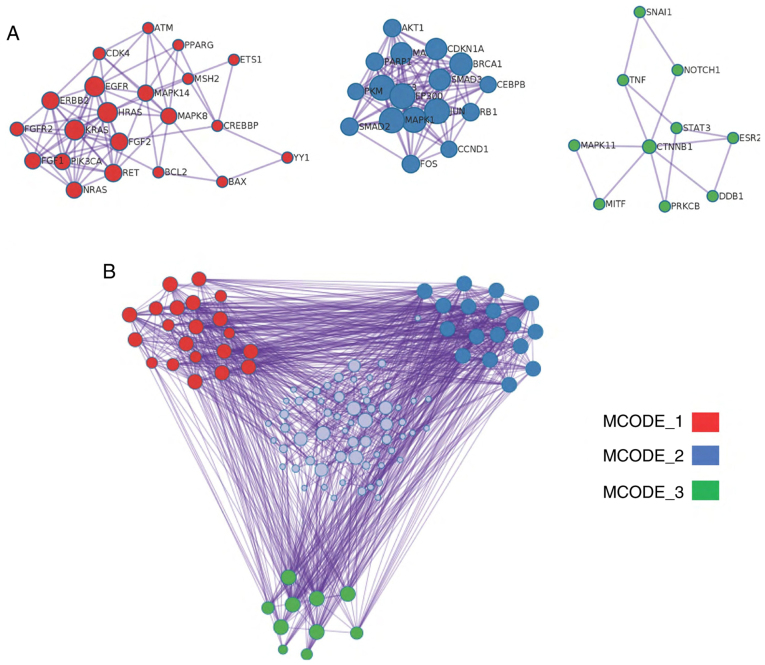

This pathway analysis was further validated using the EviNet database (https://www.evinet.org/). The detected enrichment signature was similar to the one identified using Enrich R and Metascape (data not shown). Furthermore, a deeper enrichment analysis revealing protein-protein interactions was performed considering three direct and physical connections at the minimum (Fig. 3A and B). Accordingly, the candidates were clustered into three densely connected networks upon applying the molecular complex detection algorithm using the Metascape annotation database. Each group or individual candidate within the group may represent a platform for molecular-mechanistic studies to investigate the interaction between the group members and gasotransmitters and their impact on cancer cell proliferation and response to treatment.

Figure 3.

Protein-protein interaction enrichment analysis using the BioGrid, InWeb_IM and OmniPath databases. The network contains the subset of proteins that form physical interactions with at least one other member in the list. The MCODE algorithm was applied for each network containing at least three proteins to identify densely connected network components. (A) Three MCODE clusters and corresponding protein members. Red, proteins enriched in the two best scoring pathways by P-value (‘Cancer Pathways’ and ‘Endocrine Resistance’); blue, two best scoring pathways by P-value (‘Colorectal Cancer’ and ‘Hepatitis B’), and the green cluster represents three pathways: ‘regulation of hematopoiesis’, ‘regulation of myeloid cell differentiation’ and ‘Hepatitis B’. (B) Protein-protein interaction network showing proteins in the three enriched MCODE modules and other candidate proteins, which have one physical contact with each other at the minimum. MCODE, molecular complex detection algorithm.

The present review investigated links between the current candidate list and a drug signature database containing annotations regarding drug induction or inhibition of gene expression. As shown in Table SII, the present candidate list was significantly enriched and associated with different anticancer or cancer-related drugs. The odds ratio ranking method is simply the odds ratio; however, the combined score is the odds ratio multiplied by the negative natural log of the P-value derived from Fisher's exact test and the Enrichr z-score (combined score=log(p)*z). Overall, this suggested that gasotransmitters serve essential roles in drug response signaling by cancer cells. Therefore, well-designed mechanistic studies are required to elucidate such roles and open novel avenues for drug discovery and cancer treatment modalities.

4. Effectiveness of gasotransmitters in chemotherapeutic drug treatment

Following the crucial discovery of gasotransmitters as fundamental biological molecules, their physiological significance has become a debated topic in recent decades. Utilizing gasotransmitters as therapeutic aids is justified by their roles in carcinogenesis, including enhancement of apoptotic stimuli, inhibition of metastasis and inhibition of angiogenesis. Therefore, using them alone or in combination with cytotoxic agents is an essential research platform for researchers and clinicians in cancer therapy (6,140–142).

Platinum compounds have been investigated extensively, and several studies have demonstrated that tumor cells are sensitized to cisplatin compounds by NO donors (143,144). In vitro, combination of cisplatin with natural NO gas or the NO donors diethylamine NONOate (DEA NONOate) or 1-propanamine, 3-(2-hydroxy-2-nitroso-1-propylhydrazino) NONOate increased the killing efficacy of cisplatin by 50–1,000 times compared with cisplatin alone, and the effect lasted for a number of hours (145). Furthermore, the combination treatment of cisplatin and diethylenetriamine NONOate reverses resistance and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines (146) and metastatic human colon carcinoma cell lines (147). NO-producing aspirin compounds that can emit NO for several hours have also been investigated. For example, in a clonogenic assay, nitroaspirin exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity and greatly boosted cisplatin cytotoxicity in both resistant and susceptible cells (148).

Carmustine is a chemotherapeutic drug that is combined with a NO source (the donor drug DEA NONOate), and the combination of chlorotoxin-NO, carmustine, or temozolomide enhances glioma cell death. Two variables that contributed to the enhanced cytotoxic activity of these cells were the production of active levels of the cytoprotective enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity and altered p53 activity (149).

In the same year, Shami, Saavedra, Wang, Bonifant, Diwan, Singh, Gu, Fox, Buzard, Citro, Waterhouse, Davies, Ji and Keefer (150) created glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide (JS-K), a selective targeted NO donor that was active in vitro and in vivo against human HL60 leukemia cells, following its reaction with glutathione to produce NO in vivo. JS-K acts as a chemosensitizer for doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity in renal (151), prostate (152) and bladder cancer cells (153).

NF-κB and NOS activation make HT29 human colon cancer cells more sensitive to doxorubicin cytotoxicity (154). Simvastatin increases NF-κB activity and NO production, while also increasing doxorubicin intracellular accumulation and cytotoxicity (154). The enhanced intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin is caused by tyrosine nitration in P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein 1 by NO (155). In mice with triple-negative breast cancer, NO-releasing nanoparticles in combination with doxorubicin or a doxorubicin nanoparticle carrier decreased cell survival, caused apoptosis, elevated doxorubicin intracellularly, compromised lysosomal membrane integrity and suppressed tumor growth (156). Subsequently, an S class nanocarrier of NO (Nano-NO) was developed, and successfully targeted NO to hepatocellular cancer (157). Nano-NO has improved the administration and efficacy of chemotherapy. Additionally, combining nanomaterials with NO donors, as shown by Housein et al (78) and others (158), has improved the method of NO delivery. The aforementioned Nano-NO make tumor cells more susceptible to chemotherapy.

GTN in combination with vinorelbine and cisplatin increases the response in patients with lung cancer and reduces the median time to tumor progression (159). Additionally, the combination treatment of GTN and valproic acid results in the inhibition of Bcl-2 as well as the expression of Bax and caspase-3 in human K562 cells (160). STAT3 is associated with a number of the substituted NO-releasing quinolone-1,2,4-triazole/oxime derivatives (161). In melanoma with the B-Raf V600E mutation and vemurafenib-resistant melanoma, STAT3 inhibitors have shown efficacy (161). Poly-S nitrosylated human albumin alters colon cancer cell resistance to bevacizumab (162). Furthermore, the combination of bevacizumab with S-nitrosylated human albumin exhibits antitumor effects both in vitro and in vivo (163).

Long-term (3–5 days) exposure of cancer cells to low levels of H2S (30 M; sustained >7 days) using the slow-releasing H2S donor GYY4137 causes cancer cell death in vitro by activating caspase activity and causing apoptosis (164,165). In a mouse xenograft model, GYY4137 caused a reduction in tumor volume, and this had no apparent deleterious effects on physiological functions (165). A previous study, which was performed on 11 cancer cell lines, revealed that H2S-releasing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibited the proliferation of all 11 cancer cell lines that were tested (102), providing further evidence of the potential of H2S as an anticancer agent. Using sulfide salt NaHS, which releases large amounts of H2S instantaneously in an aqueous solution (≤400 µM; detected within first 1.5 h), caused only a minimal growth inhibitory effect in cancer cell lines, indicating the possibility that a long period of continuous, low-level H2S exposure is required for its efficient anticancer function (118). Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that the anti-proliferative effect of H2S is selective, meaning it affects cancer cells but not normal cells.

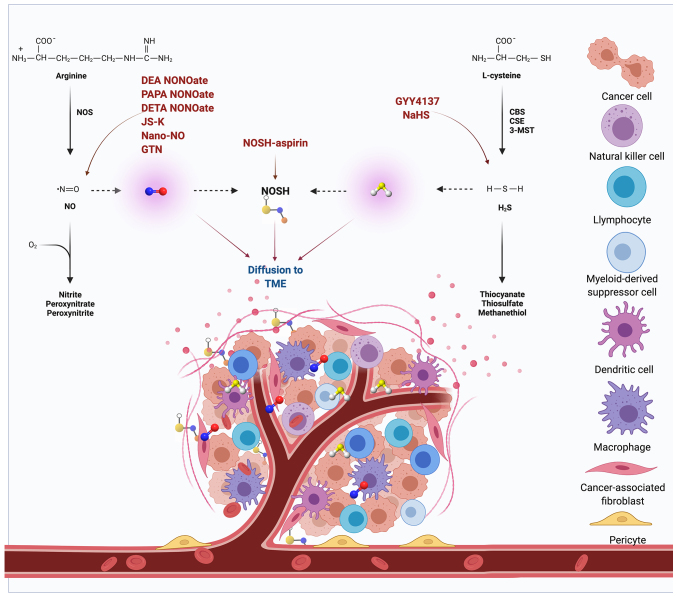

One must remember that the three gasotransmitters do not work alone. Instead, they work together. This cooperation occasionally occurs using overlapping signaling pathways (for instance, both NO and CO stimulate the sGC pathway). NO directly stimulates the sGC pathway, and H2S concurrently blocks cGMP via inhibition of cGMP phosphodiesterase (166). One of the few studies of this contest demonstrated the anticancer effect of a combined NO- and H2S-donating compound, nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing hybrid-aspirin, both in vitro and in vivo (6). The impact of NO and H2S on the TME is displayed in Fig. 4, and several gasotransmitter-based drugs targeting the TME are currently being investigated in clinical studies (167–169). To further investigate and understand the nature of these interactions, more comprehensive studies are required, mainly in the context of cancer, which may be utilized for therapeutic benefits in the future.

Figure 4.

Impact of NO and H2S on the TME. Several gasotransmitter-based drugs targeting the TME are currently being tested in clinical trials. DEA NONOate, PAPA NONOate, DETA NONOate, JS-K, Nano-NO and GTN are NO-releasing drugs, GYY4137 and NaHS are H2S-releasing drugs, and NOSH-aspirin releases NOSH into the TME. When used in combination, these drugs increase the cytotoxic activity of various chemotherapeutic drugs. 3-MST, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; CBS, cystathionine-β-synthase; CSE, cystathionine-γ-lyase; DEA NONOate, diethylamine NONOate; DETA NONOate, diethylenetriamine NONOate; GTN, nitroglycerin; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; JS-K, glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide; NaHS, sodium hydrosulfide; Nano-NO, nitric oxide nanoparticles; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOSH, nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide-releasing hybrid; PAPA NONOate, 1-propanamine, 3-(2-hydroxy-2-nitroso-1-propylhydrazino); TME, tumor microenvironment.

5. Conclusions

More than three decades of studies in the field of the three gasotransmitters NO, CO and H2S have resulted in the identification of several pathophysiological paradigms and associated experimental therapeutic approaches that may be ultimately suitable for clinical translation. In particular, the initial perplexing observation that both gasotransmitter-synthesis inhibitors and donors appear to have anticancer effects, which the complex biology and bell-shaped pharmacology of NO, CO and H2S can explain, should not be considered as a barrier to translation into clinical settings. Their critical functions in normal cells compared with cancer cells open avenues for combinatorial treatment approaches together with chemotherapeutic drugs, aiming for improved clinical significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CAF

cancer-associated fibroblast

- CBS

cystathionine-β-synthase

- CO

carbon monoxide

- CRPC

castration-resistant prostate cancer

- DEA NONOate

diethylamine NONOate

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EDRF

endothelium-derived relaxing factor

- eNOS

endothelial NOS

- GLT-1

glutamine transporter-1

- GSNO

S-nitroso glutathione

- GTN

nitroglycerin

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- HIF-1

hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- HO

heme oxygenase

- iNOS

inducible NOS

- MOPP

mechlorethamine, oncovin, procarbazine and prednisone

- N2O3

dinitrogen trioxide

- NaHS

sodium hydrosulfide

- nNOS

neuronal NOS

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

NO synthases

- NRF2

nuclear factor erythroid 2

- ONOO

peroxynitrite

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- sGC

soluble guanylyl cyclase

- TAM

tumor-associated macrophage

- TME

tumor microenvironment

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MAAN, ZOK, ZH, HAH, RMA and BMH wrote the manuscript and designed the figures. AS and TA wrote the manuscript and critically revised the paper. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Leaf C. Why we're losing the war on cancer (and how to win it) Fortune. 2004;149:76–82. 84–86, 88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, Kitui SK, Manyazewal T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211034366. doi: 10.1177/20503121211034366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ke X, Shen L. Molecular targeted therapy of cancer: The progress and future prospect. Front Laboratory Med. 2017;1:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.flm.2017.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang XJ, Chen C, Zhao Y, Wang PC. Circumventing tumor resistance to chemotherapy by nanotechnology. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;596:467–488. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-416-6_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyer AK, Khaled G, Fang J, Maeda H. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo C. Gasotransmitters in cancer: From pathophysiology to experimental therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:185–203. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu W, Liu LZ, Loizidou M, Ahmed M, Charles IG. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 2002;12:311–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngowi EE, Afzal A, Sarfraz M, Khattak S, Zaman SU, Khan NH, Li T, Jiang QY, Zhang X, Duan SF, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide donors in cancer development and progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17:73–88. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.47850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellmich MR, Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide and cancer. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;230:233–241. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18144-8_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wegiel B, Gallo D, Csizmadia E, Harris C, Belcher J, Vercellotti GM, Penacho N, Seth P, Sukhatme V, Ahmed A, et al. Carbon monoxide expedites metabolic exhaustion to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7009–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vannini F, Kashfi K, Nath N. The dual role of iNOS in cancer. Redox Biol. 2015;6:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashfi K. The dichotomous role of H2S in cancer cell biology? Déjà vu all over again. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;149:205–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tien Vo TT, Vo QC, Tuan VP, Wee Y, Cheng HC, Lee IT. The potentials of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules in cancer treatment: An outlook from ROS biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2021;46:102124. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gensini GF, Conti AA, Lippi D. The contributions of Paul Ehrlich to infectious disease. J Infection. 2007;54:221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riddell S. The emperor of all maladies: A biography of cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:5. doi: 10.1172/JCI45710. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosch F, Rosich L. The contributions of Paul Ehrlich to pharmacology: A tribute on the occasion of the centenary of his Nobel Prize. Pharmacology. 2008;82:171–179. doi: 10.1159/000149583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valent P, Groner B, Schumacher U, Superti-Furga G, Busslinger M, Kralovics R, Zielinski C, Penninger JM, Kerjaschki D, Stingl G, et al. Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) and his contributions to the foundation and birth of translational medicine. J Innate Immun. 2016;8:111–120. doi: 10.1159/000443526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faguet GB. A brief history of cancer: Age-old milestones underlying our current knowledge database. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2022–2036. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baselga J, Bhardwaj N, Cantley LC, DeMatteo R, DuBois RN, Foti M, Gapstur SM, Hahn WC, Helman LJ, Jensen RA, et al. AACR cancer progress report 2015. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21((Suppl 19)):S1–S128. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber S, Diamond LK. Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-aminopteroyl-glutamic acid. N Engl J Med. 1948;238:787–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194806032382301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotecha RS, Gottardo NG, Kees UR, Cole CH. The evolution of clinical trials for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e200. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2014.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinjo J, Nakano D, Fujioka T, Okabe H. Screening of promising chemotherapeutic candidates from plants extracts. J Nat Med. 2016;70:335–360. doi: 10.1007/s11418-016-0992-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freireich EJ, Karon M, Frei III E. Quadruple combination therapy (VAMP) for acute lymphocytic leukemia of childhood. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1964;5:20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liebman HA, Hum GJ, Sheehan WW, Ryden VM, Bateman JR. Randomized study for the treatment of adult advanced Hodgkin's disease: Mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP) versus lomustine, vinblastine, and prednisone. Cancer Treat Rep. 1983;67:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonadonna G, Zucali R, Monfardini S, De Lena M, Uslenghi C. Combination chemotherapy of Hodgkin's disease with adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and imidazole carboxamide versus MOPP. Cancer. 1975;36:252–259. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197507)36:1<252::AID-CNCR2820360128>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arruebo M, Vilaboa N, Sáez-Gutierrez B, Lambea J, Tres A, Valladares M, González-Fernández A. Assessment of the evolution of cancer treatment therapies. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:3279–3330. doi: 10.3390/cancers3033279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Brambilla C. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer: The results of 20 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher B, Sherman B, Rockette H, Redmond C, Margolese R, Fisher ER. 1-phenylalanine mustard (L-PAM) in the management of premenopausal patients with primary breast cancer: lack of association of disease-free survival with depression of ovarian function. National Surgical Adjuvant Project for Breast and Bowel Cancers. Cancer. 1979;44:847–857. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197909)44:3<847::AID-CNCR2820440309>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), corp-author Long-term outcomes for neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: Meta-analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:27–39. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Davudian S, Shirjang S, Baradaran B. The different mechanisms of cancer drug resistance: A Brief Review. Adv Pharm Bull. 2017;7:339–348. doi: 10.15171/apb.2017.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roma-Rodrigues C, Mendes R, Baptista PV, Fernandes AR. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:840. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bagnyukova TV, Serebriiskii IG, Zhou Y, Hopper-Borge EA, Golemis EA, Astsaturov I. Chemotherapy and signaling: How can targeted therapies supercharge cytotoxic agents? Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:839–853. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.9.13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27:5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkasalias T, Moyano-Galceran L, Arsenian-Henriksson M, Lehti K. Fibroblasts in the Tumor Microenvironment: Shield or Spear? Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1532. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klemm F, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of therapeutic response in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaupel P, Multhoff G. Hypoxia-/HIF-1α-Driven factors of the tumor microenvironment impeding antitumor immune responses and promoting malignant progression. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1072:171–175. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-91287-5_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jing X, Yang F, Shao C, Wei K, Xie M, Shen H, Shu Y. Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:157. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo W, Wang Y. Hypoxia mediates tumor malignancy and therapy resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1136:1–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-12734-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarosz-Biej M, Smolarczyk R, Cichoń T, Kułach N. Tumor Microenvironment as A ‘Game Changer’ in cancer radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Befani C, Liakos P. The role of hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha in angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:9087–9098. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Senthebane DA, Rowe A, Thomford NE, Shipanga H, Munro D, Mazeedi MAMA, Almazyadi HAM, Kallmeyer K, Dandara C, Pepper MS, et al. The role of tumor microenvironment in chemoresistance: to survive, keep your enemies closer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1586. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hass R, von der Ohe J, Ungefroren H. Impact of the tumor microenvironment on tumor heterogeneity and consequences for cancer cell plasticity and stemness. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3716. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019;30:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu L, Baba H, Yoshida N, Miyake K, Yasuda T, Uchihara T, Tan P, Ishimoto T. Biological heterogeneity and versatility of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019;38:4887–4901. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R. The Evolution of Gasotransmitter Biology and Medicine. In: Wang R, editor. Signal Transduction and the Gasotransmitters: NO, CO, and H2S in Biology and Medicine. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2004. pp. 3–31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrew PJ, Mayer B. Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:521–531. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryter SW, Choi AMK. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From metabolism to molecular therapy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:251–260. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0170TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naik JS, O'Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Endogenous carbon monoxide is an endothelial-derived vasodilator factor in the mesenteric circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H838–H845. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang R. The gasotransmitter role of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:493–501. doi: 10.1089/152308603768295249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang G, Wu L, Liang W, Wang R. Direct stimulation of K(ATP) channels by exogenous and endogenous hydrogen sulfide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1757–1764. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salihi A. Activation of inward rectifier potassium channels in high salt impairment of hydrogen sulfide-induced aortic relaxation in rats. Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;19:263–273. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, Xie X, Ke B, Huang W, Jiang X, He G. Recent advances on endogenous gasotransmitters in inflammatory dermatological disorders. J Adv Res. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.08.012. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West JB. Joseph Priestley, oxygen, and the enlightenment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L111–L119. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00310.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gruetter CA, Barry BK, McNamara DB, Gruetter DY, Kadowitz PJ, Ignarro L. Relaxation of bovine coronary artery and activation of coronary arterial guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide, nitroprusside and a carcinogenic nitrosoamine. J Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1979;5:211–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced and released from artery and vein is nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. The discovery of nitric oxide as the endogenous nitrovasodilator. Hypertension. 1988;12:365–372. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.12.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murad F, Mittal CK, Arnold WP, Katsuki S, Kimura H. Guanylate cyclase: Activation by azide, nitro compounds, nitric oxide, and hydroxyl radical and inhibition by hemoglobin and myoglobin. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1978;9:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koshland DE., Jr The molecule of the year. Science. 1992;258:1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1470903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marsh N, Marsh A. A short history of nitroglycerine and nitric oxide in pharmacology and physiology. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:313–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu WM, Liu LZ. Nitric Oxide: Nitric oxide: From a mysterious labile factor to the molecule of the Nobel Prize. Recent progress in nitric oxide research. Cell Res. 1998;8:251–258. doi: 10.1038/cr.1998.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yetik-Anacak G, Catravas JD. Nitric oxide and the endothelium: History and impact on cardiovascular disease. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;45:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kennedy J. Account of the phænomena produced by a large quantity of nitric oxide of quicksilver, swallowed by mistake; and of the means employed to counteract its deleterious influence. Med Chir J Rev. 1816;1:189–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomsen LL, Lawton FG, Knowles RG, Beesley JE, Riveros-Moreno V, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthase activity in human gynecological cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1352–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hidy GM, Mueller PK, Altshuler SL, Chow JC, Watson JG. Air quality measurements-From rubber bands to tapping the rainbow. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2017;67:637–668. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2017.1308890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinnicutt LP, Sanford GR. The iodometric determination of small quantities of carbon monoxide. Public Health Pap Rep. 1899;25:600–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luden G. THE carbon monoxide menace and the cancer problem. Can Med Assoc J. 1927;17:43–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roughton FJW. The Kinetics of Haemoglobin V-The Combination of Carbon Monoxide with Reduced Haemoglobin. Proc R Soc London Series B, Containing Papers Biol Character. 1934;115:464–473. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1934.0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roughton FJW, Darling RC. The effect of carbon monoxide on the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve. Am J Physiol Legacy Content. 1944;141:17–31. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1944.141.5.737-s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roughton FJ. The equilibrium between carbon monoxide and sheep haemoglobin at very high percentage saturations. J Physiol. 1954;126:359–383. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sjostrand T. Endogenous formation of carbon monoxide in man. Nature. 1949;164:580. doi: 10.1038/164580a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. Microsomal heme oxygenase. Characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao Y, Biggs TD, Xian M. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) releasing agents: Chemistry and biological applications. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:11788–11805. doi: 10.1039/C4CC00968A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tanner FW. Studies on the bacterial metabolism of sulfur: I. Formation of hydrogen sulfide from certain sulfur compounds under aerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 1917;2:585–593. doi: 10.1128/jb.2.5.585-593.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rose P, Moore PK, Ming SH, Nam OC, Armstrong JS, Whiteman M. Hydrogen sulfide protects colon cancer cells from chemopreventative agent beta-phenylethyl isothiocyanate induced apoptosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3990–3997. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang R. Signaling pathways for the vascular effects of hydrogen sulfide. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:107–112. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283430651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Housein Z, Kareem TS, Salihi A. In vitro anticancer activity of hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide alongside nickel nanoparticle and novel mutations in their genes in CRC patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2536. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82244-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen Y, Shen Z, Luo S, Guo W, Zhu YZ. The cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide in heart diseases: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic potential. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:925167. doi: 10.1155/2015/925167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coleman JW. Nitric oxide in immunity and inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1397–1406. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Esplugues JV. NO as a signalling molecule in the nervous system. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1079–1095. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]