Abstract

The cranio-orbito-zygomatic (COZ) approach consists of an extension of the pterional approach characterized by the removal of the superolateral part of the orbital rim and zygoma. This key step tremendously increases the angular exposure to some deep targets and overall surgical freedom to the lesion. In this article we review the technical variations of the COZ approach, mainly focusing on the differential quantitative effects coming from the orbital osteotomy compared to the zygomatic one. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Carotid-oculomotor Window, Optic-carotid Window, Orbito-Zygomatic Approach, Orbitopte-rional Approach, Pterional Craniotomy, Skull Base Approach, Surgical Anatomy

Introduction

The cranio-orbito-zygomatic (COZ) approach allows wide exposure of the anterior and middle skull base until the upper clivus.

It involves the addition of an orbito-zygomatic (OZ) osteotomy to the pterional approach. Removal of the OZ bar has three main advantages (1-16). The first is the dramatic increase in the subfrontal and sub-temporal view angle for those skull base lesions extensively projecting upward. The second is the shortening of the working distance. The third is obtaining a wide working space with the capability of handling the lesion from different angles.

Herein we overview the different techniques reported for the COZ approach. We also analyze the differential quantitative effects of the orbital and zygomatic osteotomy on the angular exposure of the target and overall surgical freedom.

Indications

The COZ approach is indicated for high-riding large to giant aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery (ACoA) and basilar apex, especially when projecting posteriorly. Large meningiomas of the anterior clinoid and spheno-orbital region, large crani-opharyngiomas, and giant pituitary adenomas are additional indications. The COZ approach also provides direct access to the ipsilateral crural and ambient cisterns, interpeduncular fossa, ipsilateral cerebral peduncle, and hypothalamic region. Therefore, it is also the most widely used corridor for the treatment of cavernous hemangiomas of the anterior midbrain and hypothalamus.

Technique

Positioning

The patient is placed in a supine position with the head secured to a Mayfield-Kees skull clamp. The head is elevated, extended 20°, and rotated 20° to 60° to the contralateral side depending on the target. The malar eminence is the highest point of the patient’s head. A rotation of 30° leads to a line of sight that is parallel to the long axis of the anterior clinoid. Conversely, a rotation of 45° optimizes the exposure of the subfrontal area.

Skin Incision and Soft Tissue Dissection

The curvilinear skin incision is made behind the hairline, from the contralateral midpupillary line to the level of the zygomatic process of the temporal bone, 1 cm in front of the tragus to spare the superficial temporal artery and auriculotemporal nerve. The skin flap is separated from the galea and reflected forward. Then, the preserved galea is incised along the superior temporal line and reflected anteriorly. Subperiosteal dissection prepares the galea-pericranium vascularized flap which, along with the fat graft, can be used for repair of the frontal sinus in case of violation. At the level of the temporalis muscle, the superficial and deep layers of the superficial temporal fascia are incised together 2.5 cm behind the fronto-zygomatic suture. This cut is directed obliquely toward the posterior root of the zygoma, thus making an anterior two-layer leaflet, containing the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve with its interfascial fat pad, and a posterior one. This technique is referred to as subfascial dissection.

The temporalis muscle is cut at the level of the fronto-zygomatic suture, 2 cm below the superior temporal line, to leave a myofascial cuff. It will be useful in anchoring the temporalis muscle during closure.

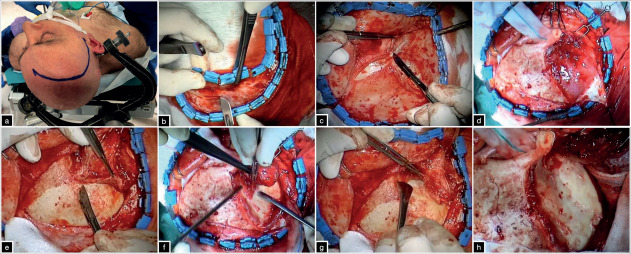

The cut curves posteriorly to reach the posterior third of the zygoma and the muscle is subperiosteally detached from the underlying bone in a retrograde superior-to-posterior and backward-to-forward direction, according to the Oikawa technique (17). Electrocau-terization must be avoided during this phase to preserve the blood supply from the internal maxillary artery, through the deep temporal arteries, and prevent muscle atrophy (11, 17-19). Then, the periorbita is freed from the superior and lateral orbital wall to a depth of 3 cm until the lateral most point of the superior orbital fissure (SOF). Care must be taken for the lacrimal gland and to maintain the periorbita intact to prevent postoperative orbital enophthalmos (figure 1).

Figure 1. (a) position and skin incision. (b-d) galea-pericranium vascularized flap and subfascial dissection of the superficial temporal fascia. (e-g) retrograde subperiosteal dissection of the temporalis muscle according to the Oikawa technique and the skeletonization of the orbito-pterional region.

Craniotomy

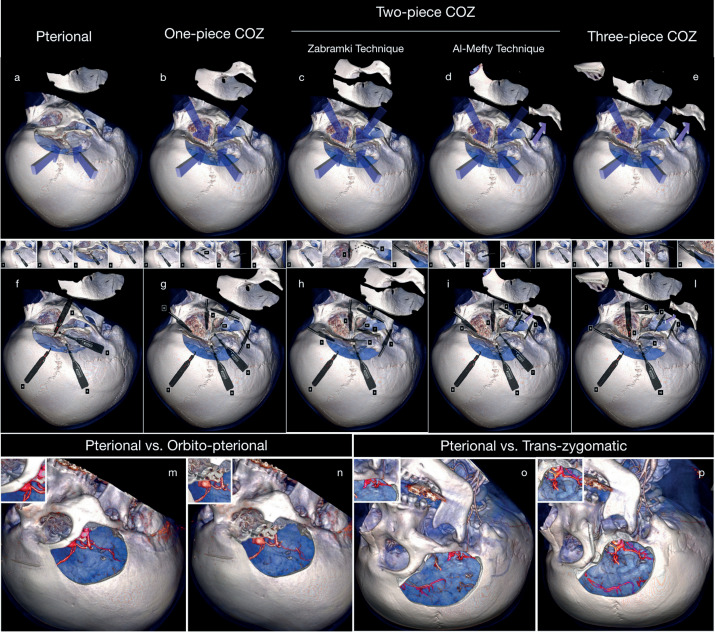

The COZ craniotomy can be performed in a one-(1-6), two-(9-11), or three-piece technique (13, 14) (figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison between pterional (a) approach and one-piece (b), two-piece (c,d), and three-piece COZ craniotomy with the relative surgical steps (f-l). Comparison in the surgical exposure between the pterional (m) vs O-pt approach (n) and pterional (o) and transzygomatic (p) approach.

One-Piece Orbito-Zygomatic Craniotomy

MacCarty keyhole is placed 5 mm behind the join between the fronto-zygomatic, spheno-zygomatic, and fronto-sphenoidal sutures. The anterior fossa dura, periorbita, and orbital roof separating them are thus exposed (4, 20). An additional burr hole is placed at the level of the temporal squama above the posterior root of the zygoma.

An additional burr hole is placed at the level of the temporal squama above the posterior root of the zygoma. The first cut involves the posterior root of the zygoma and is generally accomplished through the reciprocating saw. Preplating may be useful for osteo-synthesis. The second cut connects the keyhole with the inferior orbital fissure (IOF). A simple method to identify the IOF at the level of the infratemporal fossa is passing Penfield Dissector No. 4 placed parallel to the zygoma. The third cut involves the lateral orbital wall and is conducted across the malar eminence. The supraorbital nerve may be released and mobilized. The fourth cut is made on the intraorbital side lateral to the supraorbital notch. It crosses the superior orbital rim and orbital roof to reach the SOF. The keyhole and temporal and frontal burr holes are then connected. In the case of particularly adherent dura, a further burr hole can be placed.

The temporalis muscle is reflected downward. Galea-pericranium flap is tented with stiches protecting the eyeball and allowing for a line of sight as flat as possible to the anterior skull base.

Two-Piece COZ Craniotomy

Two variants have been reported to perform the two-piece COZ. The first, namely Zabramski’s technique, includes the pterional craniotomy plus the OZ osteotomy. Al-Mefty’s technique consists of an or-bitopterional flap completed with an osteotomy and downward mobilization of the zygoma.

Orbito-zygomatic Craniotomy (Zabramski Technique)

The first step consists of pterional craniotomy. Six different cuts are necessary to complete the removal of the OZ bar. The first cut involves the posterior root of the zygoma; the second divides the lateral and medial part of the malar eminence; the third is executed across the lateral orbital wall, from medial to lateral. In contrast with the one-piece variant, the orbital roof cut (fourth cut) is performed intracranially. It is performed from the lateral end of the SOF to the superior orbital rim. The fifth and sixth cuts unite the SOF and IOF, while the sixth one involves the anterior part of the middle fossa and is advanced up to the lateral limit of the IOF (11).

O-pt Craniotomy (Al-Mefty Technique)

The O-pt variant of the two-piece COZ consists of, as the first step, two zygomatic cuts performed at the level of the anterior and posterior roots of the zygoma. This technique avoids the detachment of the masseter muscle and decreases the risk of postoperative masticatory imbalance. Apart from the zygomatic osteotomy, the remaining steps are the same already described for the one-piece COZ, and all cuts are made extracranially (3).

Three-Piece COZ Craniotomy

The three-piece COZ approach comes from the combination of both the two-piece techniques. It entails a zygomatic osteotomy, downward mobilization of the zygomatic arch, and pterional and orbital bone flaps in separated pieces (13, 14).

Intradural Corridors

The COZ is related to four intradural corridors: subfrontal, transsylvian, pretemporal, and subtem-poral, whose accessibility is conditioned by the wide splitting of the Sylvian fissure.

The transsylvian and pretemporal corridors are associated with the optic-carotid, carotid-oculomotor, supra-carotid, and oculomotor-tentorial window. The subfrontal and transsylvian perspectives are largely used to clip large and giant ACoA aneurysms, whereas the deep windows represent the main access routes to basilar tip aneurysms.

The removal of the orbital rim, which is the roof of the subfrontal perspective, allows increasing obliquity of the line of sight backward and upward.

A shorter internal carotid artery (ICA) is related to a narrower optic-carotid and carotid-oculomotor window and a wider supra-carotid corridor to the basilar tip.

The anterior clinoidectomy, including the opening of the distal dural ring, enlarges the working space of the deep windows through lateral or medial mobilization of the ICA.

The lateral mobilization of the ICA can be required to furtherly increase the optic-carotid route to basilar apex aneurysms, also achieving the proximal control of the upper part of the mid basilar trunk. Conversely, medial mobilization of the ICA, posterior clinoidectomy and splitting of the tentorium expands the carotid-oculomotor window.

While the removal of the orbital rim is useful for high-riding basilar tip aneurysms, the increased illumination and shallowing of the surgical field coming from the zygomatic osteotomy provide advantages during pretemporal, subtemporal transtentorial, and subtemporal transpetrosal (Kawase’s) approaches in low-riding aneurysms.

The accessibility of the supra-carotid window may be reduced by perforating arteries from the ICA terminus to the anterior perforated substance.

Tailoring The COZ Approach

From a quantitative standpoint, the comparison between the pterional and COZ approach in terms of overall surgical freedom has led to assess that the removal of the OZ bar osteotomy, as a single bloc, increases the angular exposure of 8°, 6°, and 10° on the sagittal, coronal, and axial plane, respectively (21). About the surgical perspectives, the estimated angular exposure to the ACoA, basilar bifurcation, and posterior clinoid have been reported to be 75%, 46%, and 86% in the subfrontal, pterional, and subtemporal corridors, respectively (21).

For the basilar apex and posterior clinoid, the removal of the orbital rim and zygomatic arch in separate pieces leads to increases in the exposure of 28% and 22%, respectively (22).

Table 1 presents the average area of exposure of pterional, O-pt, pterional plus zygomatic, and COZ osteotomy based on the data of Schwartz and colleagues (22).

Table 1.

Average Area of Exposure to Different Targets of Pterional, O-pt, and COZ Osteotomy

| Approach | Area of exposure (mm2 ± SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior clinoid | Tentorial edge | Basilar tip | |

| Pterional | 2915 ± 585 | 2521 ± 301 | 1639 ± 244 |

| O-pt | 3702 ± 943 | 3536± 539 | 2020 ± 350 |

| COZ | 4170 ±1053 | 4249 ±1186 | 2400 ± 386 |

| O-pt, orbitopterional; COZ, cranio-orbito-zygomatic | |||

Table 2 shows the percentage increase in exposure to different targets, provided by O-pt, pterional + zy-gomatic, and COZ osteotomy compared with that in the pterional approach (22).

Table 2.

Percentage Increase in Exposure to Different Targets Provided by O-pt, Pterional + Zygomatic Osteotomy, and COZ Osteotomy Compared with That in the Pterional Approach (22)

| Surgical target (% increase in exposure) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Posterior clinoid | Tentorial edge | Basilar tip |

| O-pt | 26* | 39* | 28* |

| Pterional + Zygomatic Osteotomy | 13 | 17 | 22 |

| COZ | 43* | 64* | 51* |

| O-pt, orbitopterional; COZ, cranio-orbito-zygomatic; *p < 0.05 | |||

These morphometric data represent the basis for tailoring the COZ approach.

Complications Avoidance

The COZ-related complications can be functional or aesthetic. Injury of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve, atrophy of the temporalis muscle, masticatory imbalance, enophthalmos, diplopia, blindness, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage are the most frequent. The dissection of the superficial temporal fascia via the subfascial technique avoids damage to the fron-totemporal branch of the facial nerve, while a subpe-riosteal blunt and “cold” (without electrocauterization) dissection of the deep temporal fascia lessens the risk of temporalis muscle atrophy.

The subfascial technique is proved to be safer than the interfascial one due to the variable anatomical course of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve. In fact, in 30% of cases, many nerve twigs were found within the two fascial layers (23).

About the atrophy of the temporalis muscle, two points are recommended: first, the subperiosteal retrograde dissection of the deep temporal fascia according to the Oikawa technique (17), second, avoid excessive compression of the muscle against the zygomatic arch during its downward displacement (24).

The main reason for mobilization rather than resection of the zygomatic arch is to avoid detachment of the masseter muscle, thus preventing postoperative masticatory imbalance.

Diplopia and orbital asymmetry can be avoided by meticulous osteosynthesis, generally performed using low-profile mini plates and screws. The anatomical integrity of the periorbita is of greatest importance to prevent enophthalmos and postoperative orbital he-matomas. A potential risk for the optic nerve is the excessive downward displacement of the eyeball in the effort to maximize the exposure of the subfrontal area. The need to expand the subfrontal corridor may also cause the violation of the frontal air sinus. Crani-alization of the sinus and use of autologous fat graft and galea-pericranium vascularized flap significantly reduces the risk of infections and cerebrospinal fluid leakage.

Illustrative Cases

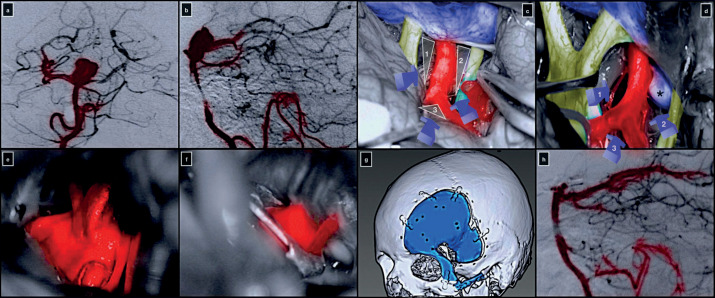

Case 1: Complex Basilar Tip Aneurysm

A 54-year-old woman was diagnosed with an incidental large basilar tip aneurysm. On digital subtraction angiography, the aneurysm had a dome-to-neck ratio of 1.5, and the dome was projecting superiorly. Both P1 segments of the posterior cerebral arteries arose from the neck, which was also calcified. The basilar bifurcation was low-riding, at 0.8 cm below the dorsum sellae.

The patient underwent a COZ approach with an extradural anterior clinoidectomy, lateral mobilization of the ICA, and posterior clinoidectomy. Posterior cli-noidectomy allowed the widening of the carotid-oculomotor window, thus gaining an optimal exposure of the mid basilar trunk. The anterior clinoidectomy and lateral mobilization of the ICA expanded the optic-carotid deep window leading to successfully clipping the aneurysm. The transsylvian and pretemporal corridors were used. The patient was discharged neurologically intact on the fifth postoperative day (figure 3).

Figure 3. Preoperative digital subtraction angiography of the right vertebral artery in anterior-posterior (a) and lateral (b) projection. (c,d) Intraoperative pictures showing the right optic-carotid (1), carotid-oculomotor (2), supra-carotid (3), and oculomotor-tentorial (4) deep windows. Exposure (e) and clip ligation (f) of the basilar tip aneurysm. (g) 3D volume-rendered post-operative CT scan highlighting the COZ approach. (h) Postoperative digital subtraction angiography of the right vertebral artery in lateral projection.

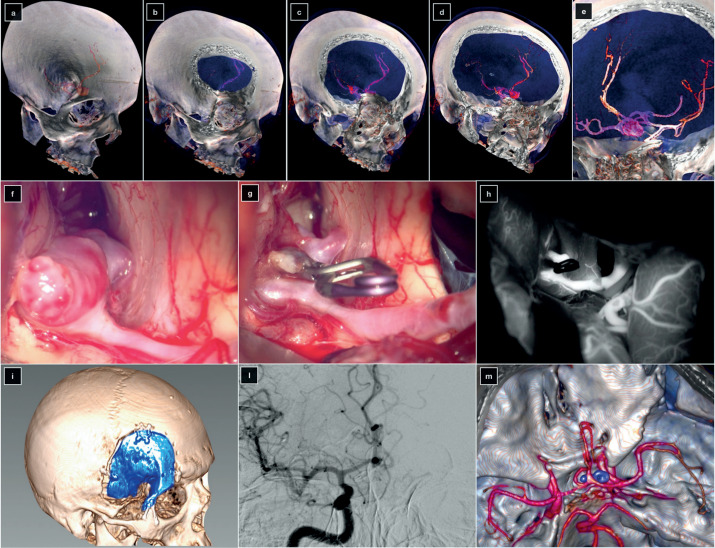

Case 2: Large ACoA Aneurysm

A large ACoA aneurysm was found incidentally in a 48-year-old female patient. The left A1 segment was hypoplasic, and both A2 segments originated from ACoA near to the neck. The aneurysm was anterior superior projecting. The blind spot was on the left A2, hidden by the orbital rim. An O-pt approach was performed. The aneurysm was successfully clipped, and the postoperative course was uneventful (figure 4).

Figure 4. (a-e) 3D volume-rendered preoperative CT angiography. Intraoperative pictures were taken before (f) and after (g) the clipping of the aneurysm. (h) Post-clipping indocyanine green videoangiography. (i) 3D volume-rendered postoperative CT scan showing the orbito-pterional approach. (l) Digital subtraction angiography of the right internal carotid artery in anterior-posterior projection. (m) Postoperative 3D volume-rendered CT angiography.

Discussion

Morphometric quantitative studies clarified the consequences of OZ osteotomy on the overall surgical freedom of the COZ approach (3, 25-33).

OZ osteotomy has three main advantages, namely, wide working space, shorter operative distance, and increased angular exposure of the target. All of these factors contribute to decreasing the need for brain retraction.

Amid the anterolateral approaches to the skull base, the COZ allows the maximum surgical freedom to deep targets, deriving from the possibility to combine the subfrontal, transylvian, pretemporal, and sub-temporal perspectives.

Several studies highlighted the advantages of the OZ osteotomy for lesions projecting upward, as high-riding ACoA and basilar tip aneurysm. An equally large number of anatomical studies supported the COZ approach for lesions extending downward, as basilar bifurcation aneurysms in patients with low-riding basilar apex, large parasellar tumors, and even infratemporal fossa lesions (21, 22, 25, 27, 30, 31, 33-38).

Indeed, the COZ approach is indicated in both upward and downward projecting lesions, since the additional exposure related to OZ bar removal is spherical rather than linear. This increase in surgical freedom is the key of the multangular approach to the target.

About the angular exposure, the superolateral or-bitotomy has quantitative and qualitative effects different from those of the zygomatic osteotomy, these aspects being arguments for tailoring the COZ (21, 22, 31, 33, 36, 39).

The removal of the orbital rim markedly raises the roof of the subfrontal corridor, also enhancing the an-terolateral perspective of the subfrontal area through the transylvian route. Conversely, the zygomatic osteotomy provides substantial advantages in the expansion of the pretemporal and subtemporal corridors (22).

The constant refinement of skull base surgical techniques, on a par with other fields of neurosurgery (40-50), has led to a progressive shift from one-to three-piece technique, the reasons for this mainly lying in a greater facility of execution and better functional and cosmetic outcomes (6, 11, 51, 52).

Conclusion

The COZ approach is an extension of the pterional approach where the removal of the OZ bar dramatically increases the angular exposure of the subfrontal, transylvian, pretemporal, and subtemporal corridors. The COZ approach finds its main indication in high-riding, giant, or complex ACoA aneurysms, in the basilar apex ones, and large tumors of the anterior and middle skull base. A careful planning and meticulous execution of the approach, along with deep knowledge of the skull base anatomy, are paramount factors to exploit all advantages of the COZ approach and decrease concurrently the risk of complications.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- Pellerin P, Lesoin F, Dhellemmes P, Donazzan M, Jomin M. Usefulness of the orbitofrontomalar approach associated with bone reconstruction for frontotemporosphenoid meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1984;15(5):715–718. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198411000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakuba A, Liu S, Nishimura S. The orbitozygomatic infratemporal approach: a new surgical technique. Surg Neurol. 1986;26(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mefty O. Supraorbital-pterional approach to skull base lesions. Neurosurgery. 1987;21(4):474–477. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz KM, Froelich SC, Cohen PL, Sanan A, Keller JT, van Loveren HR. The one-piece orbitozygomatic approach: the MacCarty burr hole and the inferior orbital fissure as keys to technique and application. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144(1):15–24. doi: 10.1007/s701-002-8270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delashaw JB,, Jr, Tedeschi H, Rhoton AL. Modified supraorbital craniotomy: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(6):954–956. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199206000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemole GM,, Jr, Henn JS, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF. Modifications to the orbitozygomatic approach. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(5):924–930. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.5.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delashaw J, Jane J, Kassell N, Luce C. Supraorbital craniotomy by fracture of the anterior orbital roof. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:615–618. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.4.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaluz N, van Loveren HR, Keller JT, Zuccarello M. The One-Piece Orbitopterional Approach. Skull base : official journal of North American Skull Base Society [et al]. 2003;13(4):241–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagargil M.G. FJL, Rayl M.W. The Operative Approach to Aneurysms of the Anterior Communicating Artery. In: al. KHe, editor. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, vol 2. Vienna: Springer. 1975 [Google Scholar]

- Jane JA, Park TS, Pobereskin LH, Winn HR, Butler AB. The supraorbital approach: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1982;11(4):537–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabramski JM, Kiris T, Sankhla SK, Cabiol J, Spetzler RF. Orbitozygomatic craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(2):336–341. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.2.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott M, Durity F, Rootman J, Woodhurst W. Combined frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic approach for tumors of the sphenoid wing and orbit. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:107–116. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo S, Komune N, Hayashi D, Amano T, Nakamizo A. Three-piece orbitozygomatic craniotomy: anatomical and clinical findings. World Neurosurg. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campero A, Martins C, Socolovsky M, Torino R, Yasuda A, Domitrovic L, et al. Three-piece orbitozygomatic approach. Neurosurgery. 2010;66((suppl_1):ons-E119-ons-E20) doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000348559.82835.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, Galzio R. Microneurosurgical management of giant intracranial aneurysms: Datasets of a twenty-year experience. Data Brief. 2020;33:106537. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, Galzio R. Surgical Management of Giant Intracranial Aneurysms: Overall Results of a Large Series. World Neu-rosurg. 2020;144:e119–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa S, Mizuno M, Muraoka S, Kobayashi S. Retrograde dissection of the temporalis muscle preventing muscle atrophy for pterional craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1996;84(2):297–299. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.2.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasargil MG, Reichman MV, Kubik S. Preservation of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve using the inter-fascial temporalis flap for pterional craniotomy. Technical article. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(3):463–466. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.3.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coscarella E, Vishteh AG, Spetzler RF, Seoane E, Zabram-ski JM. Subfascial and submuscular methods of temporal muscle dissection and their relationship to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(5):877–880. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.5.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Tanriover N, Rhoton AL,, Jr, Yoshioka N, Fujii K. MacCarty keyhole and inferior orbital fissure in orbit-ozygomatic craniotomy. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(1 Sup-pl):152–159. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000163600.31460.d8. discussion -9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaywan M, Sindou M. Fronto-temporal approach with or-bito-zygomatic removal. Surgical anatomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1990;104(3-4):79–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01842824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MS, Anderson GJ, Horgan MA, Kellogg JX, Mc-Menomey SO, Delashaw JB., Jr Quantification of increased exposure resulting from orbital rim and orbitozygomatic osteotomy via the frontotemporal transsylvian approach. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(6):1020–1026. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammirati M, Spallone A, Ma J, Cheatham M, Becker D. An anatomicosurgical study of the temporal branch of the facial nerve. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199312000-00012. discussion 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadri PA, Al-Mefty O. The anatomical basis for surgical preservation of temporal muscle. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(3):517–522. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.3.0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda A, Nanda A. Anatomical study of the orbitozygo-matic transsellar-transcavernous-transclinoidal approach to the basilar artery bifurcation. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(1):151–160. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.1.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Mefty O, Anand VK. Zygomatic approach to skull-base lesions. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(5):668–673. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.5.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva SA, Yamaki VN, Solla DJF, Andrade AF, Teixeira MJ, Spetzler RF, et al. Pterional, Pretemporal, and Orbit-ozygomatic Approaches: Anatomic and Comparative Study. World Neurosurg. 2019;121:e398–e403. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Mefty O, Smith RR. Tailoring the cranio-orbital approach. Keio J Med. 1990;39(4):217–224. doi: 10.2302/kjm.39.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo EG, Deshmukh P, Zabramski JM, Preul MC, Crawford NR, Siwanuwatn R, et al. Quantitative anatomic study of three surgical approaches to the anterior communicating artery complex. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(2 Sup-pl):397–405. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156549.96185.6d. discussion 397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez LF, Crawford NR, Horgan MA, Deshmukh P, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF. Working area and angle of attack in three cranial base approaches: pterional, orbitozy-gomatic, and maxillary extension of the orbitozygomatic approach. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(3):550–555. discussion 5-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Scerrati A, Zhang J, Ammirati M. Quantitative analysis of surgical exposure and surgical freedom to the anterosuperior pons: comparison of pterional transtentorial, orbitozygomatic, and anterior petrosal approaches. Neuro-surg Rev. 2016;39(4):599–605. doi: 10.1007/s10143-016-0710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitelli SD, Almeida GG, Nakagawa EJ, Marchese AJ, Cabral ND. Basilar aneurysm surgery: the subtemporal approach with section of the zygomatic arch. Neurosurgery. 1986;18(2):125–128. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebi Meybodi A, Benet A, Rodriguez Rubio R, Yousef S, Lawton MT. Comprehensive Anatomic Assessment of the Pterional, Orbitopterional, and Orbitozygomatic Approaches for Basilar Apex Aneurysm Clipping. Oper Neu-rosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;15(5):538–550. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebi Meybodi A, Benet A, Rodriguez Rubio R, Yousef S, Mokhtari P, Preul MC, et al. Comparative Analysis of Orbitozygomatic and Subtemporal Approaches to the Basilar Apex: A Cadaveric Study. World Neurosurg. 2018;119:e607–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti DD, Morais BA, Figueiredo EG, Spetzler RF, Preul MC. Accessing the Anterior Mesencephalic Zone: Orbitozygomatic Versus Subtemporal Approach. World Neurosurg. 2018;119:e818–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo EG, Tavares WM, Rhoton AL,, Jr, de Oliveira E. Nuances and technique of the pretemporal transcavern-ous approach to treat low-lying basilar artery aneurysms. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33(2):129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10143-009-0231-3. discussion 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giotta Lucifero A, Baldoncini M, Bruno N, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, Marseglia GL, et al. Microsurgical Neurovascular Anatomy of the Brain: The Anterior Circulation (Part I) Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S4):e2021412. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS4.12116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giotta Lucifero A, Baldoncini M, Bruno N, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, Marseglia GL, et al. Microsurgical Neurovascular Anatomy of the Brain: The Posterior Circulation (Part II) Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S4):e2021413. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS4.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giotta Lucifero A, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Nunez M, Bruno N, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, et al. The Modular Concept in Skull Base Surgery: Anatomical Basis of the Median, Paramedian and Lateral Corridors. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S4):e2021411. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS4.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Elia A, Vincitorio F, Di Perna G, Zenga F, et al. Morphometric and Radiomorphometric Study of the Correlation Between the Foramen Magnum Region and the Anterior and Posterolateral Approaches to Ventral Intradural Lesions. Turk Neurosurg. 2019 doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.26052-19.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Zoia C, Rampini AD, Elia A, Del Maestro M, Carnevale S, et al. Lateral Transorbital Neuroendoscopic Approach for Intraconal Meningioma of the Orbital Apex: Technical Nuances and Literature Review. World Neuro-surg. 2019;131:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoia C, Bongetta D, Dorelli G, Luzzi S, Maestro MD, Gal-zio RJ. Transnasal endoscopic removal of a retrochiasmatic cavernoma: A case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:76. doi: 10.25259/SNI-132-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Galzio R. Letter to the Editor. Preoperative embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2019:1–2. doi: 10.3171/2019.6.JNS191541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaout MM, Luzzi S, Galzio R, Aziz K. Supraorbital keyhole approach: Pure endoscopic and endoscope-assisted perspective. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;189:105623. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Elbabaa SK, Galzio R. Letter to the Editor Regarding “One and Done: Multimodal Treatment of Pediatric Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations in a Single Anesthesia Event”. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:660. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Giotta Lucifero A, Marasco S, Elsawaf Y, Del Maestro M, et al. Anterolateral approach for subaxial vertebral artery decompression in the treatment of rotational occlusion syndrome: results of a personal series and technical note. Neurol Res. 2021;43(2):110–125. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2020.1831303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Maestro M, Rampini AD, Mauramati S, Giotta Lucif-ero A, Bertino G, Occhini A, et al. Dye-Perfused Human Placenta for Vascular Microneurosurgery Training: Preparation Protocol and Validation Testing. World Neurosurg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Marasco S, Lucifero AG, Del Maestro M, Bellantoni G, et al. Subaxial Vertebral Artery Rotational Occlusion Syndrome: An Overview of Clinical Aspects, Diagnostic Work-Up, and Surgical Management. Asian Spine J. 2020 doi: 10.31616/asj.2020.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millimaggi DF, Norcia VD, Luzzi S, Alfiero T, Galzio RJ, Ricci A. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion with Percutaneous Bilateral Pedicle Screw Fixation for Lumbosacral Spine Degenerative Diseases. A Retrospective Database of 40 Consecutive Cases and Literature Review. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28(3):454–461. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzi S, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, Marfia G, Navone SE, Baldoncini M, et al. Anterolateral Approach for Retrostyloid Superior Parapharyngeal Space Schwannomas Involving the Jugular Foramen Area: A 20-Year Experience. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e40–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanriover N, Ulm AJ, Rhoton AL,, Jr, Kawashima M, Yoshioka N, Lewis SB. One-piece versus two-piece orbit-ozygomatic craniotomy: quantitative and qualitative considerations. Neurosurgery. 2006;58 doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000210010.46680.B4. (4 Suppl 2):ONS-229-37; discussion ONS-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaluz N, Van Loveren HR, Keller JT, Zuccarello M. Anatomic and clinical study of the orbitopterional approach to anterior communicating artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2003;52(5):1140–1148. discussion 8-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]