Abstract

Background Interprofessional practice and teamwork are critical components to patient care in a complex hospital environment. The implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) in the hospital environment has brought major change to clinical practice for clinicians which could impact interprofessional practice.

Objectives The aim of the study is to identify, describe, and evaluate studies on the effect of an EHR or modification/enhancement to an EHR on interprofessional practice in a hospital setting.

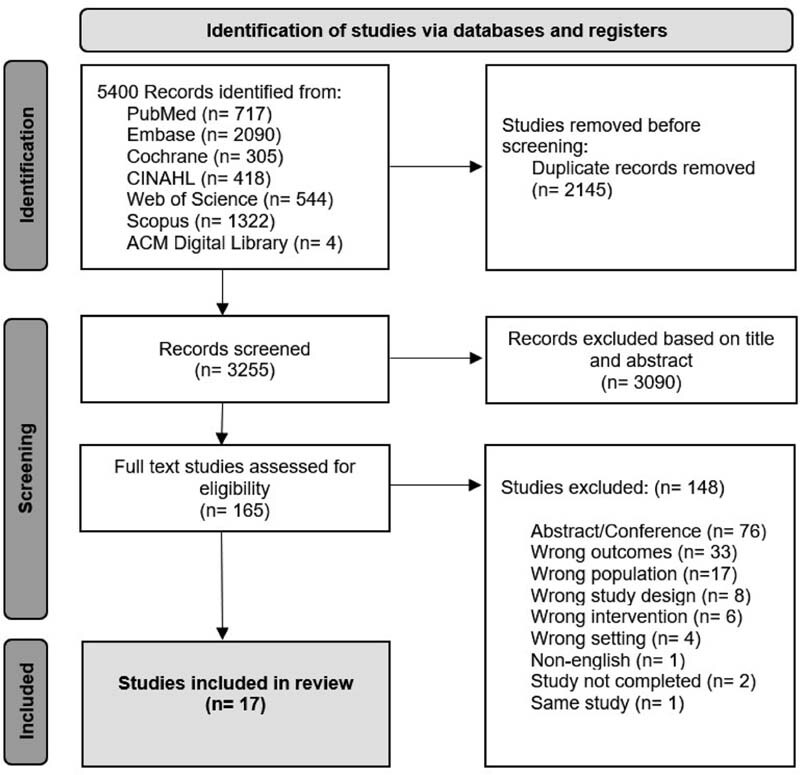

Methods Seven databases were searched including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, Cochrane, EMBASE, and ACM Digital Library until November 2021. Subject heading and title/abstract searches were undertaken for three search concepts: “interprofessional” and “electronic health records” and “hospital, personnel.” No date limits were applied. The search generated 5,400 publications and after duplicates were removed, 3,255 remained for title/abstract screening. Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Risk of bias was quantified using the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs. A narrative synthesis of the findings was completed based on type of intervention and outcome measures which included: communication, coordination, collaboration, and teamwork.

Results The majority of publications were observational studies and of low research quality. Most studies reported on outcomes of communication and coordination, with few studies investigating collaboration or teamwork. Studies investigating the EHR demonstrated mostly negative or no effects on interprofessional practice (23/31 outcomes; 74%) in comparison to studies investigating EHR enhancements which showed more positive results (20/28 outcomes; 71%). Common concepts identified throughout the studies demonstrated mixed results: sharing of information, visibility of information, closed-loop feedback, decision support, and workflow disruption.

Conclusion There were mixed effects of the EHR and EHR enhancements on all outcomes of interprofessional practice, however, EHR enhancements demonstrated more positive effects than the EHR alone. Few EHR studies investigated the effect on teamwork and collaboration.

Keywords: electronic health records, interdisciplinary teams, interprofessional practice, hospitals

Background and Significance

The past decade has seen widespread adoption of digital health technologies aiming to enable safer, high quality, more equitable and sustainable health care while also improving patient and clinician experience. 1 A major example of digital health technology in the clinical setting is the implementation of the electronic health record (EHR), often synonymous with the term electronic medical records (EMRs). 2 This computerization of medical records has had a major impact on the way clinicians work, communicate, and support patient's goals of care. 3

Interprofessional practice has been highlighted as a promising area to improve patient experience, integrated care, and efficiency of health services. 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 However, definitions of interprofessional practice have been inconsistent and ambiguous within the literature. 7 The framework by Xyrichis et al 12 has been used in this review to define interprofessional practice as four key interprofessional activities: teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking. As interprofessional networking is a recent concept and not commonly described within the context of interprofessional practice literature, we have replaced this term with communication. Communication is an essential element of teamwork underpinned by the relational coordination theory, where effective coordination of work tasks and work relationships is reliant on effective communication. 13 14 15

The premise of interprofessional practice is to create high performing teams that collaborate on patient care to improve health outcomes and health care integration. 11 It is recommended to “strengthen health systems and improve health outcomes.” 11 16 Common interventions to improve interprofessional practice involve training and education, structured checklists or communication tools, and the design of work environments. 17 18 Despite widespread agreements on its importance, research to date has been hampered by heterogenous outcome measures and small sample sizes, leading to inconclusive evidence to support improved quality of patient care. 18 More rigorous studies are required. 19

The hospital environment is a busy and complex setting and often multiple health professionals are involved in a patient's care. Effective communication amongst clinicians is essential, with communication breakdowns as one of the key preventable aspects of health care that can be mitigated via team training and team performance. 8 20 The delivery of high quality patient care relies on the ability of interdisciplinary teams to work together to achieve patient goals and improve patient outcomes. 4 6 8 16 21 22 23 24 Each discipline involved in a patient's care is mutually dependent on the other. 21 23 25

An interesting and pervasive consequence of the EHR is its change to communication and interprofessional practice amongst clinicians. As digital aspects of health care have increased, face to face communication amongst professions has decreased. 26 27 28 29 Health professionals were used to gathering around the paper chart for documentation which allowed informal and unplanned communication amongst team members. 30 Now, data can be accessed from any place at any time, providing convenience, however, also resulting in team separateness. 31 32 It is reported that some clinicians feel the EHR creates an “illusion of communication” through extensive documentation, however, their clinical notes are not read by other clinicians and therefore not acted upon. 33

Despite the challenges presented, leveraging the EHR to support key activities of interprofessional practice such as communication and collaboration appears to be expanding. 34 “Customization” or modifications of EHRs such as dashboards or clinical decision support systems enhance the potential of EHRs to improve clinical care. 35 Studies investigating EHR enhancements (e.g., secure messaging systems) have demonstrated benefits such as enhanced communication, reduce cognitive workload, and improved clinician performance. 36 However, uptake of these enhancements remains challenging. 35 36 37

The motivation for this study is that few studies to date have focused on the impact of the EHR on interprofessional teams. In addition to limited knowledge on this topic, studies that have been completed provide a piecemeal view, that is, investigating effects of the EHR on one discipline only such as doctors or nurses, or focusing on one element of interprofessional practice such as coordination of patient care. 26 27 34 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 The EHR has the potential to improve interprofessional practice, however, conflicting results are found within the literature, with disconnected teams and “information overload.” 32

Objectives

The objective of this review was to identify, describe, and evaluate studies on the effect of an EHR, or enhancement to an EHR on interprofessional practice in an inpatient hospital setting.

Methods

This systematic review has been conducted using the PRISMA guidelines 45 and was registered in PROSPERO on May 07, 2021 (CRD42021247103).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Databases searched include PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, and ACM Digital Library. Included study designs were randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, controlled before–after studies, observational studies, mixed methods, and qualitative study designs. Subject heading and title/abstract searches were undertaken for the search concepts: “interprofessional” AND “electronic health records” AND “hospital, personnel.”

An academic librarian assisted in the search strategy string to extract relevant publications related to outcomes of interprofessional practice in using an EHR system or enhancement to an EHR in an inpatient hospital setting. Initially, databases were searched up to the 12 th of March 2021. No publication date limit was applied as the timing of implementation of EHRs internationally varies widely. Reference lists were hand searched to identify further relevant publications. The search strategy was then re-applied to all databases from the 12 th of March to November 1 st , 2021 to capture the most recent publications. Reverse snowballing via Google Scholar was used to identify more recent articles that cited relevant studies. The search strategy is available in Appendix A .

Appendix A. PubMed search strategy translated to other databases.

| Terms translated to other databases | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concept 1 | Concept 2 | Concept 3 |

| “Electronic health records” [MESH] OR “Electronic Health Records” [tiab] OR “Electronic Medical Records” [tiab] OR “Electronic Health Record*” [tiab] OR “Electronic Medical Record*” [tiab] OR “Computerised Health Record*” [tiab] OR “Computerised Medical Record*” [tiab] OR “Computerized Health Record*” [tiab] OR “Computerized Medical Record*” [tiab] OR “EMR” [tiab] OR “EHR” [tiab] | “Interprofessional relations” [MESH] OR “interdisciplinary communication” [MESH] OR “Inter-professional” [tiab] OR “Interprofessional” [tiab] OR “Interdisciplinary” [tiab] OR “Inter-disciplinary” [tiab] OR “Multi-disciplinary” [tiab] OR “Multidisciplinary” [tiab] OR “collaboration” [tiab] OR “communication” [tiab] OR “teamwork” [tiab] OR “Interprofessional collaborative practice” [tiab] | “Personnel, hospital” [MESH] OR “Acute” [tiab] OR “inpatient” [tiab] OR “ward*” [tiab] |

Study Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies included were those conducted in an inpatient hospital setting with the main intervention as the EHR or modification/enhancement to the EHR. Outcome measures reported on teamwork, communication, coordination, collaboration, or staff perceptions of these. Studies involving patient-specific outcomes were excluded. The study selection criteria are outline in Table 1 .

Table 1. Systematic review inclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

| Population | Interdisciplinary, i.e., involving two or more professions (e.g., medical, nursing, allied health, IT) |

| Inpatient setting within a hospital using EHR | |

| Intervention of Interest | Effect of an inpatient EHR or EHR enhancement on interprofessional practice |

| Comparison | Routine care, i.e., prior to implementation/use of EHR or enhancement or paper-based record |

| Outcome measure | Outcomes can be any measure of: |

| • Teamwork • Collaboration • Coordination • Communication • Staff perception of communication/teamwork/coordination | |

| Study design | RCTs, non-RCTs, before-after studies, observational studies, qualitative studies Excluded: opinion pieces, unpublished studies, conference abstracts |

| Publication date | No limit |

| Language | English |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; IT, information technology; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Study Selection

Search results were exported to EndNote where duplicates were removed. A two-stage review system was used: stage one involved two independent reviewers (S.T.R., I.C.M.R.) screening the title and abstracts of publications against the inclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved by discussion and consensus voting. Stage two involved two independent reviewers (S.T.R., S.G.B.) reviewing the remaining publications in full-text. Again, conflicts were discussed and resolved between the two reviewers. The Covidence program was used to screen articles and data extraction was performed manually using a template outlining study demographics, population and setting, methods, participants, intervention groups, outcomes, and results.

Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) was used to determine risk of bias. 46 Two reviewers (S.T.R., I.C.M.R.) independently used the tool for each of the included publications. As the publications were spread across quantitative ( n = 7), qualitative ( n = 5), and mixed methods ( n = 5) study designs, the QATSDD was deemed most suitable. Reviewers score 16 items on a scale of 0 to 3; 14 of the criteria are applicable to quantitative/qualitative study designs but all 16 items are applicable to mixed study designs. Reviewers then count the scores and calculate a percentage based on the total number scored (out of 42 for quantitative/qualitative studies and 48 for mixed method study designs). Higher scores indicate higher quality research.

Reporting and Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of interventions described, outcome measures used, and the observational nature of the study designs, a meta-analysis was not possible. We have provided a narrative synthesis of the findings structured around the type of intervention (EHR or EHR enhancement) and classification of outcome investigated (e.g., communication, coordination, collaboration, teamwork). The effect of the EHR or EHR enhancement was categorized into positive, negative, or neutral/no effect for each outcome measure reported in the studies ( Appendix B ). Studies could include one or more of the outcome measures within the same classification group (i.e., a study may measure communication in a variety of ways) therefore reporting of both positive and negative results was possible for each outcome. Inductive analysis by one researcher was performed on all publications to gain further insight into reasons for positive or negative results.

Appendix B. Effect of intervention on outcome measures.

| Intervention | EHR or enhancement | Author/ Year |

Outcome 1 (communication) |

Outcome 2 (coordination) |

Outcome 3 (collaboration) |

Outcome 4 (teamwork) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHR-integrated rounding report tool (RRT) | Enhancement | Abraham et al 2019 | + + ∼ |

|||

| Large customizable interactive monitor (LCIM) | Enhancement | Asan et al 2018 | + | ∼ | ||

| Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) | EHR | Ash et al 2003 | + | − | ||

| Electronic Task Management (ETM) system | Enhancement | Cheng and South 2020 | + + ∼ |

|||

| “Microblog” messaging platform | Enhancement | Dalal et al 2017 | + + − − − |

+ | + | |

| Colposcopy Information System (CIS) | Enhancement | Goldman et al 2012 | + + − |

− | ||

| Electronic Patient Record (EPR) | EHR | Hertzum and Simonsen 2008 | + + ∼ |

|||

| Computerized Clinical Care Pathway | Enhancement | Hyde and Murphy 2012 | + + |

+ | ||

| Electronic Medical Record (EMR) | EHR | Lloyd et al 2021 | + | + | ||

| Electronic Medical Record (EMR) | EHR | Morrison et al 2008 | − ∼ ∼ |

∼ | ||

| IT/ EHR | EHR | Munoz et al 2014 |

− ∼ |

− − |

||

| eSignout (electronic handover tool) | Enhancement | Nelson et al 2017 | + | + | + | + |

| EHR prompt for present on admission (POA) Pressure Ulcers | Enhancement | Rogers et al 2013 | Results excluded as inconclusive | |||

| Health Information Technology (HIT) | EHR | Samal et al 2016 | ∼ | + + + − ∼ ∼ |

||

| Electronic signout incorporated into EHR | Enhancement | Sidlow and Katz-Sidlow 2006 | + | + | ||

| Electronic Patient Records (EPR) | EHR | Varpio et al 2009 | − − ∼ ∼ |

− ∼ |

||

| Clinical Information System (CIS) | EHR | Ward et al 2012 | ∼ ∼ ∼ |

Results

Overall, the database searches generated 5,400 publications, with 3,255 remaining after duplicates were removed. The majority of publications ( n = 3,090, Fig. 1 ) were excluded as the EHR was not the main intervention or the publication did not examine the impact of the EHR on interprofessional practice outcomes. Based on title/abstract screening, 164 publications were selected for full text review with one additional paper identified through hand searching; 148 were excluded. A total of 17 publications met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Fig. 1 illustrates the combined search strategy results and reasons for exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Search strategy results flowchart.

Table 2 outlines key study characteristics. The 17 publications that met the inclusion criteria consisted of five non-randomized pre–post studies 47 48 49 50 51 and 12 observational studies. 43 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 Of the 17 studies, only six were considered at a low risk of bias 43 47 52 53 57 60 ( Appendix C ). One study by Rogers 51 reported results that were inconclusive, therefore these results are presented in Table 2 , although excluded from the narrative synthesis. Interprofessional practice was assessed mostly via observation and/or interview data ( n = 10). Of the studies using only a survey as their measurement tool ( n = 4), few survey questions related directly to our study aim therefore results were analyzed based only on related questions (ranging from one to four questions). The majority of studies ( n = 10) involved two interprofessional disciplines, e.g., medicine and nursing compared with greater than two types of interprofessional disciplines ( n = 7). Medicine and nursing were the most frequent disciplines participating in the studies.

Table 2. Key features of included publications.

| Author/ Year/ Country |

Study design | Population and setting | Intervention | Outcome measure | Effect (+/ -/ ∼) | Significant results/conclusions | Study quality QATSDD a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al 2019 United States 47 |

Prospective, non-randomized pre-post study design | Twenty-seven participants (medical and pharmacy) across two teams participated in 169 patients rounds at an academic medical center. | EHRE: EHR integrated Rounding Report Tool (RRT) Comparator: Microsoft Word fillable rounding tool (usual tool) |

Communication: Clinical content discussed Questions raised Breakdowns in interactive communication |

+ Positive effect on communication |

Fewer questions (RRT = 7.5 (6.4), usual =10.6 (6.9),

p

= 0.03), and fewer incorrect responses when using RRT (RRT =0.07 [0.4], usual = 0.6 [1.3],

p

= 0.01); no differences for missing information between the two tools (RRT = 0.5 [0.9], usual = 0.6 [0.7],

p

= 0.5).

Quality of interactive communication was improved with the RRT with fewer interruptions through questions, and fewer incorrect responses to questions. |

69% |

| Asan et al 2018 United States 52 |

Cross sectional concurrent mixed methods study design | Thirty-six participants: 19 medical and 27 nurse practitioners (NPs) in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) | EHRE: Large Customizable Interactive Monitor (LCIM) in each patient room; data updated from EHR; view only | Perceived usefulness Perceived ease of use User satisfaction |

+ Positive effect on communication ∼ No effect on coordination |

Improved sharing of information with care team (score 2.65; range 0–6); 70% responses showed “moderate amount/quite a lot” Low effect on organization for each patient (score 1.79; range 0–6); 58% responses showed “not at all/a little.” The LCIM was perceived primarily positive by PICU medical and NPs, both for themselves and the patients and families. |

79% |

| Ash et al 2003 United States 53 |

Multisite qualitative study design | Participant observations, focus groups and interviews across three hospital facilities: 72 clinicians (unspecified) Eight IT staff Seven administrators |

EHR: Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) “a process that allows direct entering of medical orders” |

Staff perspectives of success factors for implementing CPOE | + Positive effect on communication - Negative effect on coordination |

Improved legibility with CPOE Medical and nursing communication positively changed as a result of CPOE (more interdependent). Lack of integration of various IT systems (e.g., CPOE with laboratory results) reduced coordination as information not accessible in a single place. |

83% |

| Cheng and South 2020 Australia 54 |

Retrospective cross sectional study design | Usage audit of all users of the Electronic Task Management (ETM) system in a pediatric hospital | EHRE: ETM system allows requesting and resolution of nonurgent tasks between all clinicians | Usage: type of task, urgency of task, requestor role, and time to completion |

+ Positive effect on communication | Majority of tasks were ordered by nurses for medical staff to complete (97.1%) A high level of closed-loop feedback with 77.4% of all tasks marked as completed within their requested timeframe and all tasks eventually completed. Widespread adoption and a key platform for nursing-medical clinical communication. |

45% |

| Dalal et al 2017 USA 55 |

Observational study design | Usage audit of all users of the microblog in a medical intensive care unit and 2 non-critical care units and participant survey: 21 medical 7 nursing 1 care coordinator |

EHRE: “Microblog” messaging platform to view, contribute, and communicate plans of care via a single forum and synchronization with EHR | Usage and messaging activity Useful features and barriers |

+/− Mixed effects on communication + Positive effect on coordination |

82.8% agreed that the microblog allowed transparent conversation that all care team members can view. Barriers were the availability of other messaging modalities (e.g., pagers, email, texting), poor awareness of the system, and inability to communicate with out-of-network providers. 49.4% of messages discussed care coordination; 27.2% of messages discussed care team collaboration; 65.5% respondents stated that the application was useful for improving plan of care concordance. |

55% |

| Goldman et al 2012 Canada 56 | Prospective mixed methods case study design | Usage audit (non-identifiable data) in a colposcopy clinic in large teaching hospital and 24 participant interviews: eight medical 10 nursing six IT |

EHRE: Colposcopy Information System (CIS), cumulative electronic note on patient history, examination, treatment plans to view on one screen | Usage/uptake of CIS by staff Staff perceptions of CIS |

+/− Mixed effects on communication +/− Mixed effects on coordination |

Positive: system prompts prevented clinicians from forgetting to input important information. Mixed: physicians were unsure if nurses were taking patients histories accurately. Negative: interprofessional communication time increased. Positive: visibility of information. Negative: unclear responsibility for inputting the data and coordination of care. |

44% |

| Hertzum and Simonsen 2008 Denmark 48 |

Mixed methods pre-post intervention | Observation and survey of medical and nursing staff in an acute stroke unit who attend team conferences, ward rounds, and nursing handovers. | EHR: Electronic patient record trial in an acute stroke unit for 5 d Comparator: paper-based records | Mental workload Missing pieces of information Importance assigned to tasks Responsibility for tasks. |

+ Positive effect on coordination (medical). ∼ No effect on coordination (nursing) + General positive effect on coordination |

Medical: Clarity of the importance of assigned work tasks and responsibility for tasks significantly improved while mental workload reduced with use of EHR compared with paper. Nursing: No difference in clarity about plan of care for nursing of the patient or for the medical treatment of the patient and no change in mental workload. Reduction in missing pieces of information (0.90 with paper records and only 0.17 with EPR) and messages to pass on with EHR compared with paper. |

48% |

| Hyde and Murphy 2012 USA 49 |

Pre post pilot study | Pre-post survey of nursing and ancillary staff (PT, pharmacy, nutrition, respiratory therapy, case management, social work) in a 28-bed medical-surgical department | EHRE: Computerized clinical care pathway Comparator: paper-based care plan |

Staff perceptions Documentation |

+ Positive effect on communication + Positive effect on teamwork |

“Communication of information from the clinical pathway during shift report (patient hand-off)” 34% increase (28% paper

n

= 29 to 62% electronic

n

= 21).

“Documentation by ancillary staff on the pathway” 31% increase (60% paper n = 15 to 91% electronic n = 23). “The clinical pathway allows for a multidisciplinary approach to patient care” 24% increase (71% paper n = 34 to 95% electronic n = 22). |

21% |

| Lloyd et al 2021 Australia 57 |

Observational study | Participant survey of 297 medical and nursing staff from both hospital and primary care | EHR: Electronic health record | Clinician perceptions on usability, technical quality, ease of use, benefits, collaboration |

+ Positive effect on collaboration + Positive effect on communication |

Of 199 respondents specific to hospital setting ( n = 143 medical, n = 56 nursing), 62.1% of medical and 72% of nursing staff agreed that the EHR supports collaboration and information exchange between clinicians in the same services. | 67% |

| Morrison et al 2008 UK 50 |

Qualitative observational pre-post study | Participant observation and video analysis of ward rounds in ICU: medical, nursing and allied health including pharmacy, dietetics and physiotherapy. Participant interviews of 7 medical and nursing staff |

EHR: Electronic patient record (Metavision) |

Interaction between members of a multidisciplinary team during ward rounds | -Negative effect on communication and collaboration ∼ No effect when strategies to mitigate were implemented |

Physical setup of the EHR (group formation, non-verbal behavior, access to patient data, and reaction to patient data) decreased interaction or openness of discussion, resulting in staff having less understanding of the patient goals. The easy access to information that the EHR provided did not encourage the usual trading of information that stimulates multidisciplinary interaction. |

45% |

| Munoz et al 2014 USA 58 |

Mixed methods observational study | Participant survey of 4 medical and 16 nursing staff in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) | EHR: Electronic health record | Workflow issues impacting on efficiency and satisfaction (tasks, activities, and barriers) | - Negative effect on communication ∼/- No effect or negative effect on coordination |

Three main areas of dissatisfaction in information flow: IT system, communication, and coordination. The IT system was perceived to have a negative impact on communication and coordination. 75% medical and 50% nursing staff believe the information flow in the EHR needs to be improved. |

36% |

| Nelson et al 2017 USA 59 |

Ethnographic qualitative research design | Participant observation: medical, nursing and medical assistants in a hospital emergency department (ED) Participant interviews: medical and nursing leadership |

EHRE: eSignout (electronic handoff tool) for automatic signout information and patient transfer from ED to medical ward | Social elements of clinical and organizational interactions of the key stakeholders with eSignout | + Positive effect on coordination + Positive effect on communication + Positive effect on collaboration + Positive effect on teamwork |

eSignout largely replaced verbal communication for handoffs leading to reduced disruption to workflows. When verbal communications were required, they were relevant, patient-centered, and succinct. eSignout allowed staff to gain a more coherent picture of the patient, improving communication and care for patients. Teamwork and collaboration improved through increased mutual respect and a shared understanding of clinician's respective time pressures |

45% |

| Rogers et al 2013 USA 51 |

Pre-post study design | Documentation audit; comparing medical and nursing documentation pre and post implementation in an acute hospital setting | EHRE: Electronic tool to identify, communicate and document Present On Admission (POA) Pressure Ulcers (PrUs) | Communication and documentation of POA PrUs | ∼ No effect on communication | The implementation of the electronic prompt did not contribute to the improvement in the communication process between the admitting physicians and the clinical nurses because the improvement in POA PrUs rates occurred before the EHR prompt intervention. | 29% |

| Samal et al 2016 USA 60 |

Qualitative study design | 29 participants: clinicians and information technology professionals from six regions chosen as national leaders in HIT | EHR: Health Information Technology (HIT) specifically focused on EHR | Care coordination: patient level, provider level and systems level | + Positive effect on coordination (patient level) ∼/- No effect/ negative effect on coordination (provider level) +/− Mixed effect on coordination (system level) |

Positive uses of HIT to “assess patients' needs and goals,” “monitor, follow-up and respond to change” and some examples of HIT to “support patients' self-management goals.” HIT was occasionally used in “establishing accountability” and “communication” however, processes were inefficient and had a negative impact on information transfer due to lack of interoperability. | 79% |

| Sidlow and Katz-Sidlow 2006 USA 61 |

Cross sectional observational pilot study | Participant survey of 19 nurses on a general medical acute care unit | EHRE: Electronic sign-out tool | Communication between nursing and medical staff | + Positive effect on communication + Positive effect on coordination |

Communication between medical and nursing staff improved—score 4.6 (where 5 greatly improved and 1 worsened). Coordination improved by nurses' access to the sign-out tool allowing development of an accurate daily nursing plan of care – score 4.3. | 29% |

| Varpio et al 2009 Canada 43 |

Qualitative study | Participant observation of 9 medical and 62 nursing staff in one ward of a pediatric hospital Interviews: 9 medical and 11 nursing staff |

EHR: Electronic patient records | Interprofessional communication strategy | ∼/- No effect/ negative effect on communication ∼/- No effect/ negative effect on collaboration |

34% of communication mediated by the EHR resulted in a workaround: 6/44 workarounds Participants intentionally stopped using the system as it impeded workflow; 30/44 workarounds participants deliberately compromised their work patterns to adopt pathways allowed by the system. Senior medical staff were more likely to display a heightened awareness of the interprofessional effects of workarounds compared with junior staff. |

81% |

| Ward et al 2012 USA 62 |

Prospective, nonexperimental evaluation study | 840 participant surveys: 48 medical 341 nursing 451 other clinical across 7 hospitals |

EHR: Clinical information system of EHR and CPOE | Perception of communication and information flow | ∼ No effect on communication | Staff perceptions of communication were not affected with implementation of the EHR: “Communication between medical and hospital staff is adequate to meet patient care needs” Baseline 4.7 (1.2); Pre-implementation 4.7 (1.0); post implementation 4.6 (1.2) | 52% |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; EHRE, electronic health record enhancement.

Authors of the QATSDD tool suggest that scores >60% are considered at low risk of bias. 46

Appendix C. Study Quality Assessment via the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD).

| Study ID (Author, Year) |

Abraham et al 2019 | Asan et al 2018 | Ash et al 2003 | Cheng and South 2020 | Dalal et al 2017 | Goldman et al 2012 | Hertzum and Simonsen 2008 | Hyde and Murphy 2012 | Lloyd et al 2021 | Morrison et al 2008 | Munoz et al 2014 | Nelson et al 2017 | Rogers et al 2013 | Samal et al 2016 |

Sidlow and Katz-Sidlow 2006 | Varpio et al 2009 | Ward et al 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 33 | 38 | 35 | 19 | 23 | 21 | 23 | 9 | 28 | 19 | 15 | 19 | 12 | 33 | 12 | 34 | 22 |

| % | 69 | 79 | 83 | 45 | 55 | 44 | 48 | 21 | 67 | 45 | 36 | 45 | 29 | 79 | 29 | 81 | 52 |

| Criteria | |||||||||||||||||

| Explicit theoretical framework | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Statement of aims/objectives in main body of report | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Clear description of research setting | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Evidence of sample size considered in terms of analysis | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Representative sample target group of reasonable size | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Description of procedure for data collection | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Rationale for choice of data collection tool(s) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Detailed recruitment data | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tool(s) (Quantitative only) |

2 | 3 | − | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | − | 0 | − | 0 | − | 1 | − | 1 |

| Fit between stated research question and method of data collection (Quantitative only) |

3 | 3 | − | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | − | 1 | − | 2 | − | 0 | − | 1 |

| Fit between research question and format and content of data collection tool (Qualitative only) |

2 | 3 | 3 | − | − | 2 | 1 | − | − | 2 | 2 | 2 | − | 2 | − | 3 | − |

| Fit between research question and method of analysis | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Good justification for analytic method selected | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Assessment of reliability of analytic process (Qualitative only) |

3 | 3 | 3 | − | − | 0 | 0 | − | − | 1 | 0 | 0 | − | 2 | − | 3 | − |

| Evidence of user involvement in design | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Strengths and limitations critically discussed | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Of the 17 publications, 47% investigated the EHR and 53% investigated the effect of an EHR enhancement. Studies investigating the EHR found some positive effects on interprofessional practice (8/31 outcomes; 26%), although most showed no effect (14/31 outcomes; 45%). EHR enhancements demonstrated a more positive trend on outcomes (20/28 outcomes, 71%), with positive findings distributed across communication, coordination, collaboration, and teamwork ( Table 3 ). Studies on the EHR ranged from publication in the year 2003 to 2016 and studies on EHR enhancements were published in 2006 to 2021.

Table 3. Effect of the intervention on interprofessional practice outcomes.

| Total studies n (%) |

Effect | Overall outcomes f (%) |

Outcome of communication f (%) |

Outcome of coordination f (%) |

Outcome of collaboration f (%) |

Outcome of teamwork f (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHR | 8 (47) | Positive | 8 (26) | 2 (13) | 5 (42) | 1 (25) | 0 |

| Negative | 9 (29) | 4 (27) | 4 (33) | 1 (25) | 0 | ||

| No effect | 14 (45) | 9 (60) | 3 (25) | 2 (50) | 0 | ||

| EHRE | 9 (53) | Positive | 20 (71) | 13 (68) | 3 (60) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Negative | 5 (18) | 4 (21) | 1 (20) | 0 | 0 | ||

| No effect | 3 (11) | 2 (11) | 1 (20) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 17 | 59 | 34 | 17 | 6 | 2 |

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; EHRE, electronic health record enhancement; f, frequency of outcome; n, number of studies.

Communication was the most studied outcome measure for both EHR and EHR enhancements ( f = 34; 58%). The majority of EHR studies showed no effect on communication ( f = 9; 60%) in comparison to studies investigating EHR enhancements demonstrating positive effects on communication ( f = 13; 68%). Coordination of care was mainly studied amongst EHRs. There were mixed effects of the impact on coordination amongst teams with both the EHR and EHR enhancements. Few studies investigated the specific outcomes of collaboration or teamwork.

EHR enhancements included a variety of intervention tools that were incorporated into the EHR (as described in Table 2 ). Three of the EHR enhancement tools were designed specifically for interprofessional communication, for example, communicating outstanding tasks, discussing plans of care for patients, and highlighting patient priorities to team members. 54 55 61 Five of the EHR enhancement tools were more focused on sharing patient information, for example, computerized care plans or automated templates for documentation or handover. 47 49 52 56 59 Studies often reported mixed findings, for example, Dalal et al 55 investigated a microblog messaging platform which demonstrated improved team communication, coordination, and collaboration through improved visibility of information by all team members, however, negative impacts to communication through the inability to use this system with clinicians outside the hospital environment.

Despite mixed results, most outcome measures evaluated the impact of the EHR/ EHR enhancement on communication and coordination. Common concepts were noted for both positive and negative results: (1) sharing of information, (2) visibility of information, (3) closed-loop feedback, (4) decision support, and (5) workflow disruptions.

Sharing of Information

There were mixed findings reported on the ability to share information in studies investigating an EHR. In a recent Australian survey of clinicians using an EHR, 62.1% of doctors and 72% of nursing staff in hospitals across Australia agreed upon EHRs supporting collaboration and information exchange between clinicians in the same services. 57 Conversely, a study conducted in the United Kingdom in 2014 reported that the IT system (EHR) was perceived to have a negative impact on communication and coordination. 58 Furthermore, a U.S. study of nine critical access hospitals in North Iowa showed no effect of a new EHR on communication between hospital staff before and after implementation, with relatively high rates of clinician satisfaction regarding communication and information transfer with both paper-based records and EHRs. 62

Publications that reported on EHR enhancements found more positive benefits associated with the ability to share information. In a study investigating a customizable touchscreen monitor and display (LCIM), which receives data from the EHR, 70% of doctors and nurse practitioners stated that the LCIM monitor improved sharing of information with the care team. 52 The ability for the EHR to share information amongst professions was also demonstrated through an electronic sign-out tool intervention. 61 Although this tool was initially used by doctors to handover salient clinical information during medical shift changes, the ability for nursing staff to use this tool in their own clinical practice improved information exchange and communication across professions. 61

Visibility of Information

Multiple studies described the value of team members being able to view the communication and interactions of other professions via the EHR. 52 55 56 58 Sixty percent of doctors and nurse practitioners viewing the LCIM 52 felt this tool was useful in their ward rounds in the pediatric intensive care unit setting and aided in their clinical work. Similarly, survey responses evaluating a “microblog” messaging platform showed that 82.8% of interdisciplinary team members agreed that a valuable feature of the platform was the “transparent conversation that all team members can view.” 55 In contrast, the study by Morrison et al describes the struggle for health professionals to adequately display the clinical information when engaging in an ICU ward round. Physical set up of the health care team around the EHR system during ward rounds impacted the ability to view and therefore interact with discussions about the patient, i.e., the study suggests a physical change to formation of the team around the EHR in a horseshoe format to allow all members of the team to see the EHR data as well as each other. 50

Closed-Loop Feedback

Studies within this review described the benefit of closed-loop feedback via the EHR supporting interprofessional practice. In an electronic task management intervention by Cheng and South, 54 the authors reported a high level of “closed-loop feedback,” as once a requested task is completed by a clinician, a message is sent back to the requestor. 54 A read-receipt functionality was also a key component within the study by Dalal et al 55 where a “microblog” messaging platform allowed visualization of when messages were read and by whom. When asynchronous communication via the EHR occurs, this visual representation of messages being received is an important aspect for allowing team members to coordinate and collaborate on patient care. However, some studies demonstrated how closed-loop feedback did not work optimally within the EHR due to confusion around who is responsible for each aspect of patient care represented in the EHR. 48 58

Decision Support

EHR systems can provide real-time decision support for clinicians through automated prompts, messages, and forcing functions. 56 60 As described in Ash et al 53 investigating a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in the EHR, communication among doctors, nurses and pharmacists has changed and “caused everybody to become more interdependent.” Positive effects of an EHR enhancement on providing prompting and decision support were also seen in the study by Goldman et al, 56 investigating a Colposcopy Information System (CIS), an electronic note that allows health professionals to view a flow sheet of cumulative data and patient history on one screen. 56 However, in their study investigating to what extent Health Information Technology (HIT) is involved in care coordination, Samal et al 60 concludes that despite its potential, there is a low utilization of HIT to impact care coordination at the patient level.

Workflow Disruption

Mixed results were seen regarding disruptions to clinical workflow. Clinicians using an EHR integrated Rounding Report Tool (RRT), which automatically collects and organizes clinical information from the EHR, experienced less interruptions to workflow through lower requirements in seeking clarifying information. 47 Benefit has been reported from capacity for asynchronous clinical handover through an electronic sign out system, with minimization of workflow disruption due to automatic transfer of information through the EHR. 59 61 However, one study in this review exploring communication between doctors and nurses using an EHR showed the common use of “workarounds” (“informal temporary practices for handling exceptions to normal workflow”). 43 63 In a study by Varpio et al 43 the authors showed that 34% of communication facilitated by an EHR resulted in a workaround demonstrating workflow disruptions. 43

Discussion

This systematic review included 17 publications on the effect of the EHR or EHR enhancement on interprofessional practice. The majority of studies evaluated outcomes of communication 43 47 48 49 50 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 and coordination. 48 52 55 56 58 59 60 Fewer studies reported on the effect on the EHR/EHR enhancement on collaboration 43 50 53 55 57 59 or teamwork. 49 59 Overall, there were mixed findings on the effect of the EHR/EHR enhancement on interprofessional practice with both positive and negative impacts evident for sharing of information, visibility of information, closed-loop feedback, decision support and workflow disruption. EHR enhancements demonstrated a more positive trend for its impact on communication amongst interprofessional teams.

From EHR to EHR Enhancements

Results showed that evaluation of EHR enhancements are more common in the literature in the past 5 years. This may indicate that implementation and adoption of EHRs are becoming more universal and now, modifications and adaptations to EHRs are taking place to address unintended consequences, described as “unpredictable, emergent problems” as a result of EHR use. 64 Unintended consequences of the EHR on interprofessional practice are evident throughout this systematic review, with increased workflow disruptions, negative impacts of sharing of information within teams, and insufficient use of the EHR to feedback clinical information between professions. 43 58 60 Interestingly, these negative impacts were not demonstrated in the studies investigating enhancements to the EHR. This may be due to EHR enhancements being specifically designed to mitigate these negative effects. Customization of EHRs (e.g., enhancements) have provided some solutions for operational and technical factors that impact clinical communication; however, these are often in response to issues or problems faced. Within this review, EHR enhancements appear to be designed specifically to fix a problem (reactive) rather than to accommodate the goals of the organization or end-users (proactive). However, there is also the possibility that these negative effects were understudied in the EHR enhancement publications.

Interprofessional Practice and the EHR

Studies in this review show mixed findings on the impact of the EHR to provide enhanced clarity of patient care. 48 56 Hertzum and Simonsen 48 studied the effect of the EHR on clinical activity and results indicated that the EHR enhances clarity of the patient care plan as well as clarity around the responsibility of tasks by clinicians. Conversely, in the study by Goldman et al 56 on the CIS, it was unclear who was responsible for inputting data which negatively impacted coordination of care. This phenomena has been previously reported in a primary care setting investigating the impact of the EHR on coordination of patient care. 39 The authors describe that when teams with a high level of cohesion utilize the EHR, there is greater agreement on patient goals of care and improved clarity about the responsibilities of patient care. 39 It is possible that clinicians working in more cohesive teams may see greater benefits of improved care coordination with an EHR, possibly due to better procedures regarding data retrieval and documentation as well as more shared learning. 39

Greater communication and coordination of work via EHRs may enhance efficiency, however, interprofessional practice encompasses many additional aspects beyond sharing of information and feedback of information. The particular activities associated with interprofessional practice are underpinned by enabling values of teamwork such as trust, interdependence, and mutual respect. 8 10 14 30 One approach to describing teamwork is from the viewpoint of shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect, that is, acting with a greater regard for the “whole,” higher level systems thinking and respecting individual contributions to achieve the desired outcome. 14 Teams that are described as “high performing teams” demonstrate improved quality and efficiency of care. 65 66 With increased use of EHRs to communicate and coordinate clinical tasks, face to face interaction amongst clinicians decreases and there is a risk of health care teams losing the essential elements of teamwork. The loss of the important constructs of teamwork such as shared identity and mutual respect could negate the productivity achieved through EHR enhancements.

Digital health technology has changed the way clinicians work with each other. One of the key findings of this study is that targeted enhancements to an EHR have the capability of promoting enhanced communication and coordination of patient care. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted care by enforcing virtual ward rounds, remote patient assessments, social distancing, and virtual team meetings. This has in turn impacted the nature of team functioning and interprofessional practice in the clinical setting. 67 Asynchronous communication and coordination of care via the EHR have been used widely in response to COVID-19 challenges and may have altered staff perceptions regarding the value of the EHR for such uses. For example, users may place a higher value on comprehensive clinical documentation or EHR messaging systems when they are less able to exchange clinical information through face-to-face meetings or handover. The adjustments to interprofessional practice in the COVID-19 era have been necessary short-term measures to protect the health of both staff and patients, however, long-term impacts to health care teams and ultimately patient care are yet to be determined.

Future Considerations

Ultimately, the goal of health care lies within the quadruple aim of achieving optimal patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and clinician satisfaction at a reduced cost. 68 The revision from the triple aim to the quadruple aim of health care proposed the additional important element of clinician satisfaction. 69 This was considered essential as the effectiveness of health care organizations relies on their workforce, which Sikka et al 69 describes as “an engaged and productive workforce.” The key to clinician engagement is finding joy and meaning in work and many studies have lamented the growing increase of clinician burnout, especially evident throughout the digital transformation of health care and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. 70 71 72 73 Evidence shows that teamwork plays an important role in reducing clinician burnout and promoting clinician well-being, 65 71 74 75 76 in addition to achieving optimal patient outcomes, 6 77 78 79 patient satisfaction, 80 and efficiency 81 in line with the “quadruple aim” of health care. 69 As the use of EHRs becomes more ubiquitous in daily clinical practice, the link between teamwork and clinician satisfaction cannot be overlooked.

The inconsistency and ambiguity of definitions of interprofessional practice in the literature has made it challenging to identify the overall impact of the EHR on interprofessional practice. 12 82 There is a need for hospital environments to evaluate where efficiency can be achieved through use of EHRs and where face-to-face teamwork is essential to achieve integrated care. We cannot simply substitute the interaction of teams from face-to-face to digital, and there is a need to consider the context in which interprofessional tasks are performed. Where clinical work is more complex, time constrained and interdependent, the notion of teamwork seems more important, and EHR enhancements may not be the answer to improving interprofessional practice in this case. Future studies should aim to utilize a common definition of interprofessional practice with agreed upon outcome measures and rigorous study designs. 18

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the heterogeneity of outcome measures and study designs and therefore inability for meta-analysis of results. Additionally, as definitions of interprofessional practice in the literature are still ambiguous, our search terms may not encompass all available studies on this topic. Our study aimed to integrate the effect of an EHR on interprofessional components such as communication, coordination, collaboration, and teamwork. This viewpoint reflects the complex nature of teams within a hospital environment and the complexity of implementation of digital health interventions. However, in this review, not all studies incorporated whole interdisciplinary teams; interprofessional practice was mainly studied amongst the medicine and nursing professions with only few studies including the viewpoints of allied health practitioners in addition. 49 50 53 54 55 62 Therefore, studies within this review may not represent a true interdisciplinary depiction of teams within a clinical setting. In selecting publications for inclusion within the systematic review, the EHR was required to be the main intervention. There is a possibility that studies investigating process enhancements of an EHR have been published, however, not directly described as a result of the EHR resulting in selection bias, however, dual screening and the broad search terms reduce this potential. Additionally, when critically evaluating study quality and coding of publications, some subjectivity of results were inevitable. Results and constructs gathered from this study were based on heterogenous outcome measures and relatively small sample sizes. 48 49 51 59 61 The majority of publications in this study were observational and of poor research quality.

Conclusion

Interprofessional practice is widely considered an essential element of high quality patient care, 6 25 yet research remains limited into the effect of the EHR on the way interprofessional teams function. Our study demonstrates mixed findings on the impact of the EHR/EHR enhancements on aspects of interprofessional practice including communication, coordination, collaboration, and teamwork. EHR enhancements showed more positive results in the ability to communicate (sharing of information, visibility of information, closed-loop feedback) and coordinate (decision support and reduced workflow disruptions) patient care. The impact of the EHR/EHR enhancements on other components of interprofessional practice such as collaboration and teamwork remains understudied.

Clinical Relevance Statement

This systematic review summarizes existing research into how the EHR and EHR enhancements impact interprofessional practice in the hospital environment. Clinicians should be encouraged to use digital health technologies such as the EHR to their advantage in communicating and coordinating patient care. Findings from this review demonstrate that the EHR can be used to promote interprofessional practice, however, continuing to encourage elements of teamwork through face to face interactions remains important in a digitally evolving environment.

Multiple Choice Questions

-

The most commonly studied areas of interprofessional practice in the context of the Electronic Health Record (EHR) include?

a. Communication and teamwork.

b. Communication and coordination.

c. Communication, coordination, collaboration, and teamwork.

d. Coordination and teamwork.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is option b. This study shows that the effects of the EHR and/or EHR enhancements have been more frequently studied within the areas of communication and coordination. Few studies within this review have demonstrated the use of EHR/EHR enhancement to promote interprofessional collaboration or teamwork.

-

EHR and EHR enhancements have impacted interprofessional practice in what way?

Positive impact on interprofessional practice.

Negative impact on interprofessional practice.

Both positive and negative impact on interprofessional practice.

No impact on interprofessional practice.

Correct Answer: The answer is option c. This review demonstrated mixed findings on the impact of interprofessional practice in the areas of sharing of information, visibility of information, real time feedback, decision support, and reduced disruption to clinical workflows.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding received for this project by the Digital Health CRC in Australia. We acknowledge the contributions of Marcos Riba, Liaison Librarian at the University of Queensland and the University of Queensland Centre for Health Services Research (CHSR) for education on the systematic review process.

Funding Statement

Funding This research was supported by the Digital Health CRC and Queensland Health research grant “Bringing Digital Excellence to Clinical Excellence: Leading Digital Excellence in Queensland Health.” Digital Health CRC Limited is funded under the Commonwealth Government's Cooperative Research Centres Program.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

No human subjects were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Alami H, Lehoux P, Gagnon M P, Fortin J P, Fleet R, Ag Ahmed M A. Rethinking the electronic health record through the quadruple aim: time to align its value with the health system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(01):32. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-1048-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wager K A, Lee F W, Glaser J P. 4th ed. Somerset: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 2017. Health Care Information Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical Informatics Committee of the American College of Physicians . Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(04):301–303. doi: 10.7326/M14-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dow A W, Zhu X, Sewell D, Banas C A, Mishra V, Tu S P. Teamwork on the rocks: rethinking interprofessional practice as networking. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(06):677–678. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1344048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Körner M. Interprofessional teamwork in medical rehabilitation: a comparison of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team approach. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(08):745–755. doi: 10.1177/0269215510367538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morley L, Cashell A. Collaboration in health care. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2017;48(02):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2017.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(01):1–3. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salas E, Wilson K A, Murphy C E, King H, Salisbury M. Communicating, coordinating, and cooperating when lives depend on it: tips for teamwork. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(06):333–341. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D.Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare Postgrad Med J 201490(1061):149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen M A, DiazGranados D, Dietz A S. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(04):433–450. doi: 10.1037/amp0000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xyrichis A, Reeves S, Zwarenstein M. Examining the nature of interprofessional practice: an initial framework validation and creation of the InterProfessional Activity Classification Tool (InterPACT) J Interprof Care. 2018;32(04):416–425. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1408576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolton R, Logan C, Gittell J H. Revisiting relational coordination: a systematic review. J Appl Behav Sci. 2021;57(03):290–322. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gittell J H. Edward Elgar Publishers; 2006. Relational Coordination: coordinating work through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gittell J H, Godfrey M, Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional collaborative practice and relational coordination: improving healthcare through relationships. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(03):210–213. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.730564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutfiyya M N, Chang L F, McGrath C, Dana C, Lipsky M S. The state of the science of interprofessional collaborative practice: a scoping review of the patient health-related outcomes based literature published between 2010 and 2018. PLoS One. 2019;14(06):e0218578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie K D, van Wijngaarden J DH. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(01):2. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0411-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(06):CD000072–CD72. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3(03):CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzberg S, Hansen M, Schoonover A. Association between measured teamwork and medical errors: an observational study of prehospital care in the USA. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e025314. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green B N, Johnson C D. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(01):1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Interprofessional Practices Team . Kuziemsky C E, Borycki E M, Purkis M E. An interdisciplinary team communication framework and its application to healthcare ‘e-teams’ systems design. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmutz J, Manser T. Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(04):529–544. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holden R J, Binkheder S, Patel J, Viernes S HP. Best practices for health informatician involvement in interprofessional health care teams. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(01):141–148. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1626724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schot E, Tummers L, Noordegraaf M. Working on working together. A systematic review on how healthcare professionals contribute to interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(03):332–342. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1636007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bardach S H, Real K, Bardach D R. Perspectives of healthcare practitioners: an exploration of interprofessional communication using electronic medical records. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(03):300–306. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1269312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor S P, Ledford R, Palmer V, Abel E. We need to talk: an observational study of the impact of electronic medical record implementation on hospital communication. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(07):584–588. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu R C, Tran K, Lo V. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith C NC, Quan S D, Morra D. Understanding interprofessional communication: a content analysis of email communications between doctors and nurses. Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(01):38–51. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2011-11-RA-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross A H, Leib R K, Tonachel A. Teamwork and electronic health record implementation: a case study of preserving effective communication and mutual trust in a changing environment. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(11):1075–1083. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.013649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eden R, Burton-Jones A, Grant J, Collins R, Staib A, Sullivan C. Digitising an Australian university hospital: qualitative analysis of staff-reported impacts. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(05):677–689. doi: 10.1071/AH18218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furlow B. Information overload and unsustainable workloads in the era of electronic health records. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(03):243–244. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison M I, Koppel R, Bar-Lev S. Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care–an interactive sociotechnical analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(05):542–549. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bates D W. Health information technology and care coordination: the next big opportunity for informatics? Yearb Med Inform. 2015;10(01):11–14. doi: 10.15265/IY-2015-020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collinsworth A W, Masica A L, Priest E L. Modifying the electronic health record to facilitate the implementation and evaluation of a bundled care program for intensive care unit delirium. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2014;2(01):1121. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazur L M, Mosaly P R, Moore C, Marks L. Association of the usability of electronic health records with cognitive workload and performance levels among physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(04):e191709. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmgren A J, Pfeifer E, Manojlovich M, Adler-Milstein J. A novel survey to examine the relationship between health IT adoption and nurse-physician communication. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(04):1182–1201. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-08-RA-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vos J FJ, Boonstra A, Kooistra A, Seelen M, van Offenbeek M. The influence of electronic health record use on collaboration among medical specialties. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(01):676. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05542-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graetz I, Reed M, Shortell S M, Rundall T G, Bellows J, Hsu J.The association between EHRs and care coordination varies by team cohesion Health Serv Res 201449(1 Pt 2):438–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feufel M A, Robinson F E, Shalin V L. The impact of medical record technologies on collaboration in emergency medicine. Int J Med Inform. 2011;80(08):e85–e95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Malley A S, Grossman J M, Cohen G R, Kemper N M, Pham H H. Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(03):177–185. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romanow D, Rai A, Keil M. CPOE-enabled coordination: appropriation for deep structure use and impacts on patient outcomes. Manage Inf Syst Q. 2018;42(01):189–212. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varpio L, Schryer C F, Lingard L. Routine and adaptive expert strategies for resolving ICT mediated communication problems in the team setting. Med Educ. 2009;43(07):680–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watterson J L, Rodriguez H P, Aguilera A, Shortell S M. Ease of use of electronic health records and relational coordination among primary care team members. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(03):267–275. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Page M J, McKenzie J E, Bossuyt P M. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71):n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(04):746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abraham J, Jaros J, Ihianle I, Kochendorfer K, Kannampallil T. Impact of EHR-based rounding tools on interactive communication: a prospective observational study. Int J Med Inform. 2019;129:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hertzum M, Simonsen J. Positive effects of electronic patient records on three clinical activities. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(12):809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyde E, Murphy B. Computerized clinical pathways (care plans): piloting a strategy to enhance quality patient care. Clin Nurse Spec. 2012;26(05):277–282. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e31825aebc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrison C, Jones M, Blackwell A, Vuylsteke A. Electronic patient record use during ward rounds: a qualitative study of interaction between medical staff. Crit Care. 2008;12(06):R148. doi: 10.1186/cc7134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers C.Improving processes to capture present-on-admission pressure ulcers Adv Skin Wound Care 20132612566–572., quiz 573–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asan O, Holden R J, Flynn K E, Murkowski K, Scanlon M C. Providers' assessment of a novel interactive health information technology in a pediatric intensive care unit. JAMIA Open. 2018;1(01):32–41. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooy020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ash J S, Gorman P N, Lavelle M. Perceptions of physician order entry: results of a cross-site qualitative study. Methods Inf Med. 2003;42(04):313–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng D R, South M. Electronic task management system: a pediatric institution's experience. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(05):839–845. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1721321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dalal A K, Schnipper J, Massaro A.A web-based and mobile patient-centered “microblog” messaging platform to improve care team communication in acute care J Am Med Inform Assoc 201724(e1):e178–e184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldman J, Abramovich I A, Sadovy B, Murphy K J, Rice K, Reeves S. The development and implementation of an electronic departmental note in a colposcopy clinic. Comput Inform Nurs. 2012;30(02):91–96. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e318224b567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lloyd S, Long K, Oshni Alvandi A. A National Survey of EMR Usability: comparisons between medical and nursing professions in the hospital and primary care sectors in Australia and Finland. Int J Med Inform. 2021;154:104535. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munoz D A, Bastian N D, Ventura M.A Workflow Assessment for a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: A Mixed-Methods ApproachPaper presented at: IIE Annual Conference Proceedings;20142952–2961.

- 59.Nelson P, Bell A J, Nathanson L, Sanchez L D, Fisher J, Anderson P D. Ethnographic analysis on the use of the electronic medical record for clinical handoff. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(08):1265–1272. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samal L, Dykes P C, Greenberg J O. Care coordination gaps due to lack of interoperability in the United States: a qualitative study and literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1373-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sidlow R, Katz-Sidlow R J. Using a computerized sign-out system to improve physician-nurse communication. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(01):32–36. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward M M, Vartak S, Loes J L. CAH staff perceptions of a clinical information system implementation. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(05):244–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blijleven V, Koelemeijer K, Wetzels M, Jaspers M. Workarounds emerging from electronic health record system usage: consequences for patient safety, effectiveness of care, and efficiency of care. JMIR Human Factors. 2017;4(04):e27. doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sittig D F, Wright A, Ash J, Singh H. New unintended adverse consequences of electronic health records. Yearb Med Inform. 2016;(01):7–12. doi: 10.15265/IY-2016-023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Havens D S, Gittell J H, Vasey J. Impact of relational coordination on nurse job satisfaction, work engagement and burnout: achieving the quadruple aim. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(03):132–140. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gittell J H. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2011. Relational Coordination: Guidelines for Theory, Measurement and Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goddard A F, Patel M.The changing face of medical professionalism and the impact of COVID-19 Lancet 2021397(10278):950–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(06):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sikka R, Morath J M, Leape L. The quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608–610. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poon E G, Trent Rosenbloom S, Zheng K. Health information technology and clinician burnout: current understanding, emerging solutions, and future directions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(05):895–898. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocab058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith C D, Balatbat C, Corbridge S.Implementing Optimal Team-Based Care to Reduce Clinician Burnout. NAM Perspectives.National Academy of Medicine; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Esmaeilzadeh P, Mirzaei T. Using electronic health records to mitigate workplace burnout among clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: field study in Iran. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(06):e28497. doi: 10.2196/28497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holzer K J, Lou S S, Goss C W. Impact of changes in EHR use during COVID-19 on physician trainee mental health. Appl Clin Inform. 2021;12(03):507–517. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chang B P, Cato K D, Cassai M, Breen L. Clinician burnout and its association with team based care in the Emergency Department. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(11):2113–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song H, Ryan M, Tendulkar S. Team dynamics, clinical work satisfaction, and patient care coordination between primary care providers: A mixed methods study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(01):28–41. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Welp A, Meier L L, Manser T. The interplay between teamwork, clinicians' emotional exhaustion, and clinician-rated patient safety: a longitudinal study. Crit Care. 2016;20(01):110. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1282-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carter B L, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James P A. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1748–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berry J C, Davis J T, Bartman T. Improved safety culture and teamwork climate are associated with decreases in patient harm and hospital mortality across a hospital system. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(02):130–136. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyubovnikova J, West M A, Dawson J F, Carter M R. 24-Karat or fool's gold? Consequences of real team and co-acting group membership in healthcare organizations. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2015;24(06):929–950. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Will K K, Johnson M L, Lamb G. Team-based care and patient satisfaction in the hospital setting: a systematic review. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;6(02):158–171. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davis M J, Luu B C, Raj S, Abu-Ghname A, Buchanan E P. Multidisciplinary care in surgery: are team-based interventions cost-effective? Surgeon. 2021;19(01):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reeves S, Goldman J, Gilbert J. A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprofessional interventions. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(03):167–174. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.529960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]