Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the time-lagged, bidirectional relationships among clinical variables of pelvic pain, urinary symptoms, negative mood, non-pelvic pain and quality of life (QOL) in men and women with UCPPS, incorporating interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS).

METHODS:

204 female and 166 male patients were assessed up to 24 times over a 48-week period on the five primary outcomes. A lagged autoregressive analysis was applied to determine the directional relationship of one variable to another two weeks later, beyond that of the concurrent relationships at each time point and autocorrelations and trends over time.

RESULTS:

The results show clear evidence for a bidirectional positive relationship between changes in pelvic pain severity and urinary symptom severity. Increases in either variable predicted significant increases in the other two weeks later, beyond that explained by their concurrent relationship at each time point. Pelvic pain and to a lesser degree urinary frequency also showed similar bidirectional relationships with negative mood and decreased QOL. Interestingly, neither pelvic pain or urinary symptom severity showed lagged relationships with non-pelvic pain severity.

CONCLUSION:

Results document for the first time specific short-term positive feedback between pelvic pain and urinary symptoms, and between symptoms of UCPPS, mood, and QOL. The feedforward aspects of these relationships can facilitate a downward spiral of increased symptoms and worsening psychosocial function, and suggest the need for multifaceted treatments and assessment to address this possibility in individual patients.

Keywords: urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes, interstitial cystitis, chronic prostatitis, pain, urinary symptoms, autoregressive analysis

Introduction

Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) include idiopathic chronic pelvic pain in both men and women. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS)1 has historically been diagnosed primarily in women whereas chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS)2 is a diagnosis exclusive to men. Although most often these conditions have been studied separately, they share prevalence of key symptoms, psychosocial impact and some neurobiological mechanisms 3–6. While the pathophysiology of UCPPS is unclear and likely heterogeneous, studies from the Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Research Network (see Appendix A) have shown, 1) pelvic pain and urinary symptoms represent two distinct but correlated facets of UCPPS, 2) patients with UCPPS report higher levels of multiple psychosocial difficulties than healthy controls, 3) a majority of patients with UCPPS also report persistent pain problems outside of the pelvic region, and 4) increased presence of psychosocial disruption and a greater number of non-pelvic symptoms are associated with poorer one-year symptom outcomes 6.

Cross-sectional, case control data indicate higher levels of negative affect and stress are related to UCPPS symptoms, 4, 7, 8 but little is known regarding the temporal relationships among UCPPS symptoms and psychosocial variables. For example, does exacerbation of urinary symptoms precede or follow exacerbation of pain? Do changes in negative mood precede or follow increased pain? No prior studies have examined how these major clinical variables interact over time and whether there are sex differences in these relationships.

The MAPP Network’s Trans-MAPP Epidemiology and Phenotyping (Trans-MAPP EP) Study followed a large group of men and women with UCPPS for 12 months using an observational (i.e., treated natural history) design.6, 9. The present study examines biweekly symptom data from the Trans-MAPP EP study to address the time-lagged,10 bidirectional relationships among pelvic pain, urinary symptoms, negative mood, non-pelvic pain and quality of life. The lagged autoregressive approach allowed estimation of the predictive relationship of one variable on another two weeks later across all available assessments, simultaneously controlling for cross-sectional correlations, autocorrelations across time, as well as trends over time. The study addresses the following hypotheses: 1) Level of pain and urinary symptoms mutually correlate over time such that increases in either component are followed by subsequent increases in the other beyond the correlation at a single time point (e.g., pain predicts urinary symptoms two weeks later, and likewise urinary symptoms predict pain, two weeks later). 2) Bidirectional relationships will also be found between the pain and urinary symptom severity measures and measures of mood and non-pelvic pain, and 3) The cross-lagged relationships will be similar for males and females with UCPPS.

Materials and Methods

The MAPP Research Network is a multi-disciplinary, multi-site, NIDDK-funded study group that conducts highly integrated and collaborative studies designed to improve our understanding of IC/BPS and CP/CPPS. 11

Participants:

Details of recruitment methods and inclusion and exclusion criteria have been published 11. Participants had to have a diagnosis of IC/BPS or CP/CPPS, pain severity of at least 1 on a 0–10 numerical rating scale, be over age 18, and have urinary symptoms present the majority of the time during three of the previous six months. As previously reported the sample was largely White and drawn primarily from urban or suburban areas. 12 Recruitment was from both clinics and community advertisement, and income levels were quite diverse. There were no specific criteria regarding current or past treatment; treatment history varied widely among participants.

Design:

Following informed consent and enrollment, participants completed the study assessments via computer during a single baseline visit. They were subsequently contacted every two weeks for a total of 48 weeks to provide symptom and psychosocial data using validated questionnaires and specific single items as detailed below.

Measures:

The MAPP patient-reported outcomes used in this study are described in prior publications. 4, 11, 13 UCPPS severity was characterized on two distinct dimensions; Pelvic Pain Severity (PPS) and Urinary Symptom Severity (USS) based on a multivariate psychometric analysis of the MAPP baseline data. 13 Pelvic Pain Severity varied from 0 to 28 and was the sum of the pain subscore of the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI)14 and Item 4 of the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI)15. Urinary Symptom Severity varied from 0 to 25 and was the sum of the GUPI urinary subscore and ICSI Items1–3. Single item, 0–10 numerical rating scales (NRS), with higher score indicating worse outcomes, were used to assess non-pelvic pain severity (Non-Pelvic Pain NRS), mood (Mood NRS), and pelvic region pain severity (Pelvic Pain NRS) over the past two weeks. Quality of Life impact of UCPPS was assessed from the QOL subscale of the GUPI.

Statistical Analysis:

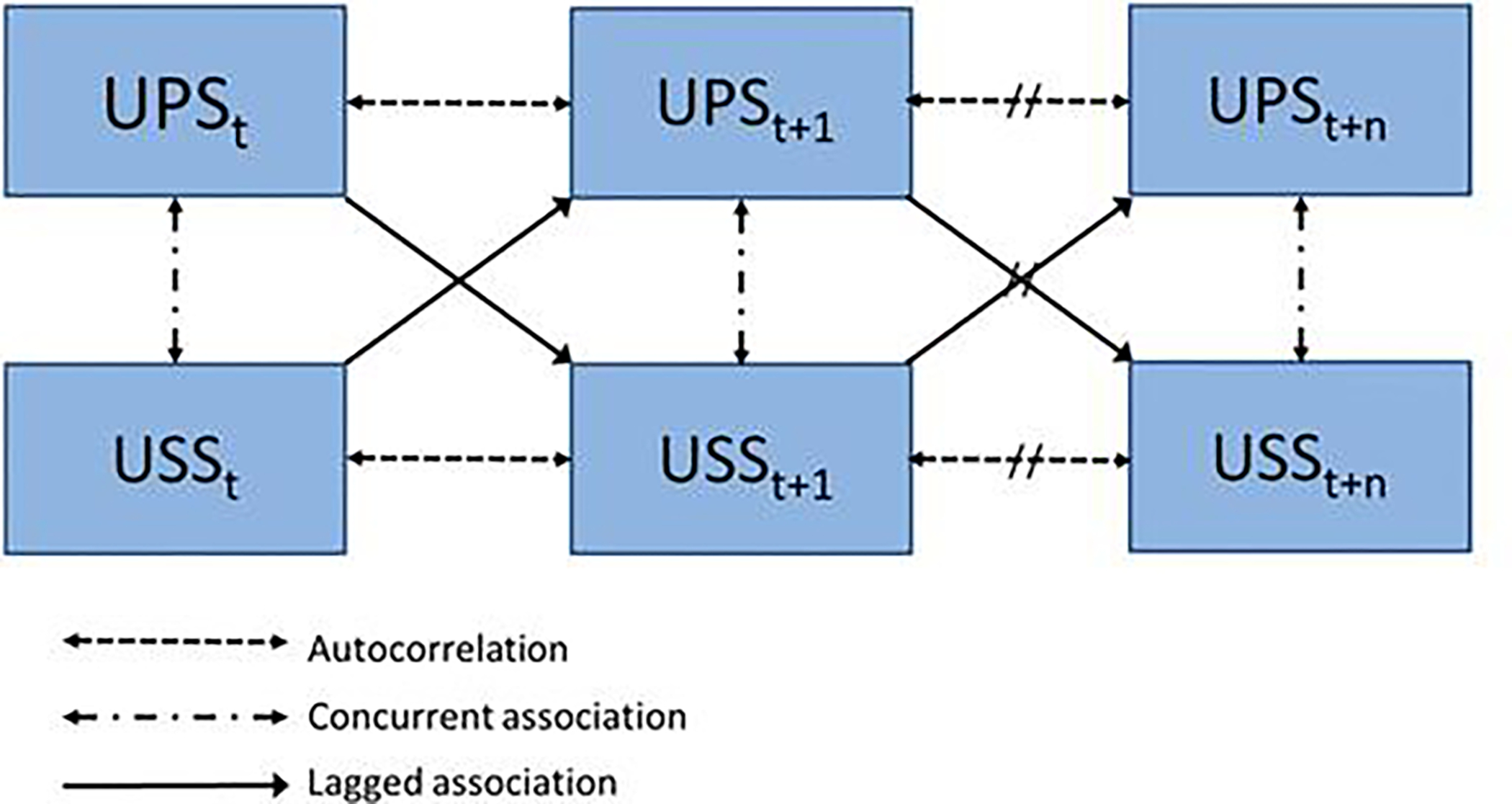

Analysis of each of the hypothesized relationships for each variable pair followed the same format and included all available biweekly assessments: 1) the average concurrent correlation of the two variables at each time point was computed, 2) the average autocorrelation of each variable with itself two weeks later was computed, 3) the correlation of each variable with the other at the two week lag was calculated, and 4) the relationship of each variable with the other two weeks later after controlling for both the concurrent and autocorrelations was determined (lagged analysis). These relationships are illustrated in Figure 1. Descriptive information on the participants and the concurrent and autocorrelation results are reported in Supplement, Appendix B. The main hypotheses for this study were tested with a lagged analysis utilizing residual dynamic structural equation modeling (RDSEM) and the Mplus program. 16 Unlike standard correlations, this approach enables simultaneous evaluation of concurrent and lagged directional relationships between variables over time.

Figure 1.

The lagged analysis examined relationships across all consecutive biweekly assessments starting at study week 4. Arrows show types of associations included in the analyses. PPS=Pelvic Pain Severity Index, USS= Urinary Symptom Severity Index, t=time (t=week 4, t+1=week 6, etc.)

The RDSEM model provided both unstandardized and standardized coefficients, with standardized coefficients representing the standard deviation (SD) change in the dependent variable as a result of a one-SD change in the covariate. The mean standardized regression coefficients normalized to have unit variance (i.e., variance of 1.0), including both auto- and cross-lagged regression coefficients, are also presented as a standardized effect size. Statistical significance was examined by inspecting p values and 95% confidence intervals with α = .05 as the threshold for significance. Further details of the RDSEM analysis are in Supplement, Appendix B.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics:

The sample consisted of 204 female and 166 male individuals with UCPPS enrolled in the Trans-MAPP EP study.12 Due to a large consistent decline in symptoms over the first month of the study, likely due to regression to the mean combined with an attention effect from study entrance, the first two assessments were not used in the the analysis.17 Each participant was therefore assessed up to 23 times over the 48-week study on the 5 primary outcomes. On average 72% of these possible data points were obtained and usable for the analysis. Further descriptive information is contained in Supplement Appendix B.

Pelvic Pain Severity and Urinary Symptom Severity:

The lagged analysis showed significant bidirectional associations at a two-week lag (see Table 1 for all lagged analyses). Examination of the standardized β coefficients show relatively strong and similar associations for PPS predicting USS (β=0.50) and USS predicting PPS (β=0.57). Males showed a small but statistically significantly larger prediction of USS from PPS two weeks later compared to females (for males standardized β=0.19, p<.05; for females β=0.15, ns) In contrast, sex did not significantly modify PPS prediction of USS.

Table 1.

| Standardized β, 95% CI | |||

| Estimate | Lower 2.5% | Upper 2.5% | |

| USS Index ==> PSS Index | 0.57 | 0.28 | 1.00 |

| PPS Index ==> USS Index | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.73* |

| Nonpelvic Pain==> NRS PPS Index | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.36 |

| PPS Index ==> Nonpelvic Pain NRS | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.38 |

| Mood NRS ==>PPS Index | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.58* |

| PPS Index ==>Mood NRS | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.74* |

| Gupi QOL==>PPS Index | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.56* |

| PPS Index ==>Gupi QOL | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.53* |

| Nonpelvic Pain NRS==> USS index | −0.05 | −0.37 | 0.24 |

| USS index ==>Nonpelvic Pain NRS | 0.12 | −0.12 | 0.37 |

| Mood ==>NRS USS Index | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.53* |

| USS Index ==> Mood NRS | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.40 |

| Gupi QOL ==> USS Index | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.70* |

| USS Index ==> Gupi QOL | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.64* |

| Nonpelvic Pain NRS ==> Pelvic Pain NRS | 0.21 | −0.10 | 0.57 |

| Pelvic Pain NRS ==> Nonpelvic Pain NRS | 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.26 |

Significant p <0.05, 1-tailed from Mplus output.

Pelvic Pain and Urinary Symptom Severity Associations with Mood:

Lagged analysis indicated a significant bidirectional relationship between PPS and mood (for PPS predicting mood, standardized β=0.44; for Mood predicting PPS, β=0.31). USS was not a significant predictor of mood at the two-week lag (standardized β=.09) but mood did significantly predict USS (standardized β=0.32). These associations were not significantly modified by participant sex.

Pelvic Pain and Urinary Symptom Severity Associations with Severity of Non-Pelvic Pain:

Neither PPS nor USS were significantly associated with Non-Pelvic Pain in the lagged nalysis. Standardized βs for PPS predicting Non-Pelvic pain or Non-Pelvic pain predicting PPS at the two-week lag were small and non-significant. This was also true for USS and Non-Pelvic pain and was not impacted by participant sex.

Pelvic Pain and Urinary Symptom Severity Associations with Illness Impact:

The lagged analysis showed significant bidirectional associations of QOL with both PPS and USS. Standardized β coefficients for PPS predicting QOL and QOL predicting PPS were 0.33 and 0.34 respectively. The standardized coefficient for USS predicting QOL was 0.34, while the coefficient for QOL predicting USS was larger (0.52). These associations were not significantly impacted by participant sex.

Discussion:

Prior research has shown general associations among various measures of urological symptoms and psychosocial variables. The current study, however, is the first to directly examine the temporal and longitudinal relationships among these variables biweekly over an extended, one year period.8 The results show clear evidence for a direct bidirectional, longitudinal. positive relationship between changes in pelvic pain severity and urinary symptom severity, with urinary symptoms being primarily characterized by increased urinary frequency. Increases (or decreases) in either variable predict significant increases (or decreases) in the other two weeks later over and above their concurrent relationship at each time point. This suggests that the two most common symptom domains in UCPPS may act in a positive feedback loop with each other over a period of weeks, with the potential impact of mild exacerbations of specific symptoms predicting a much more widespread disruptive flare-up event. Similarly, it also suggests improvement in one can help generate a positive symptom spiral.

In addition, as hypothesized, we found that changes in mood share a bidirectional relationship with UCPPS pain severity. If pain increases, mood likely worsens several weeks later and similarly if mood worsens it predicts an increased level of pain will follow. Mood changes predicted changes in urinary symptoms but not vice versa suggesting mood shares a closer relationship with pelvic pain than urinary symptoms. To the degree that mood influences later symptoms of UCPPS, treatments for mood disturbance such as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) may be more effective for patients with predominant chronic pelvic pain as opposed to those with predominant urinary symptoms such as increased frequency.

Somewhat surprising was the absence of significant lagged relationships between pelvic pain or urinary symptomsand changes in non-pelvic pain. The degree of non-pelvic or widespread pain is known from both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to be associated with UCPPS severity 18, however, this relationship does not seem to hold in terms of reciprocal potentiation of urological and non-pelvic pain in our biweekly data. This suggests it may be the presence or absence of a more stable widespread pain phenotype that is most impactful in terms of UCPPS severity and not the more acute fluctuations in ongoing non-pelvic pain severity. To assess whether the absence of a relationship may have been due to differences in measurement method, we examined the cross-lagged relationship of non-pelvic pain to a single-item NRS measure of pelvic/urological pain severity also assessed at each time point. Results were also non-significant and non-substantive in terms of effect size with respect to any cross-lagged relationship.

UCPPS pain and urinary severity measures also showed significant bidirectional relationships with GUPI QOL indicating that the impact of the illness influences and is influenced by UCPPS symptoms over several weeks. This suggests that a focus on lessening the impact of the disorder perhaps through addressing catastrophizing or coping ability, may have beneficial effects on future urinary and pain symptoms. Similar to mood, it seems that pain symptoms are more closely tied to QOL than problems related to urinary frequency; further suggesting pain is an important target for treatment especially in cases with declining QOL.

The present analysis goes beyond prior examinations of these variables in several unique ways including the size and diversity of the sample, study length, breath of variables, and the examination of predictive directional relationships. It has previously been suggested that a biobehavioral approach that emphasizes positive feedback between clinical and psychosocial variables is important to the understanding of the limited success of urological focused treatment of UCPPS.6, 19 The potential feedforward aspects of the relationships shown here may facilitate a downward spiral of increased symptoms and worsening psychosocial function. It is therefore understandable that interventions that narrowly target specific symptoms and do not take into account the facilitating influences of other variables will be less effective. 20 This holds true for treatments that target either, but not both, pelvic pain and urinary frequency, as well as treatments that target only peripheral symptoms but not psychosocial variables such as altered mood or illness coping that impact daily functioning. The relationships between pelvic pain and both mood and QOL were stronger than that of urological symptom severity, especially with respect to how much increased urological symptoms precipitated declines in mood and QOL two weeks later. Thus, pain management is a key target for intervention and may help prevent a negative symptom spiral. Overall the data strongly support multifaceted treatment and assessment that address both urological symptoms and psychosocial factors to improve personalized treatment targeting and provide an ‘early warning system’ for developing negative feedback situations. It is important to note that we observed no significant differences in the relationships across men and women with UCPPS, although some differences in average severity were noted. Thus the implications of the current data for UCPPS treatment apply equally to men and women.

Several limitations of the current data should be noted. In terms of measurement, all of the primary variables were based on participants’ self-report, several of which were single items and may therefore not be as reliable as multi-item scales. In addition, data were collected via the internet; however, the validity of internet versus in-person assessment has been established 21, 22. The relative short-term retrospective period of two weeks and the large number of within-subject replications for each relationship studied also bolsters confidence in the findings. The significant cross-lagged relationships were small to medium sized (standardized βs ranged from 0.3 to 0.5), but given the control for auto- and concurrent correlations, we would argue that they indicate a substantial sequential relationship of one variable on another across time. Although the lagged analysis cannot positively identify causation it goes beyond standard regression approachs by specifying directional relationships not explained by auto- or concurrent associations. The current analysis looked only at bivariable relationships and did not examine possible confounding or mediating variables that could partially or totally account for the observed associations. For example, changes in pain severity and associated changes in urinary severity may be jointly caused by interruptions in medication or diet; relationships between symptoms and mood may also be caused by or mediate changes in physical activity, which in turn may impact subsequent symptoms. Future studies including randomized trials combined with mediation and moderation analysis of factors that may impact symptoms will be important to further elucidate these relationships.

Conclusions

The traditional view in Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes was that the urinary and pain symptoms were caused by the same process, presumably inflammation. The evolution of our understanding of these conditions has shown that many do not have inflammation, and based on the MAPP data, urinary and pain symptoms do not always track together indicating possible different sources.13 The current study further indicates that while somewhat separate, these facets of UCPPS do influence each other. Taken together, the MAPP data supports an approach to treating both aspects of the condition, pain and urinary symptoms, whether with common treatments or with multimodal therapy to get both. The data also support the need to address areas traditionally outside of the Urologists’ focus but important to the disease, namely mood and psychological aspects. A global approach addressing the multifaceted nature of the syndrome appears to be needed to best treat patients.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. MAPP Research Network masthead.

Appendix B. Descriptive statistics and RSample statistics and RDSEM methods.

Acknowledgments:

Funding for the MAPP Research Network was obtained under a cooperative agreement from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health (NIH) [DK082315 (Andriole, G; Lai, H), DK082316 (Landis, J), DK082325 (Buchwald, D), DK082333 (Lucia, M), DK082342 (Klumpp, D; Schaeffer A), DK082344 (Kreder, K), DK082345 (Clauw, D; Clemens, JQ), DK082370 (Mayer, E; Rodriguez L), DK103227 (Moses, M), DK103260 (Anger, J; Freeman, M), DK103271 (Nickel, J)]. The NIDDK and MAPP Network investigators wish to thank the Interstitial Cystitis Association and the Prostatitis Foundation for their assistance in study participant recruitment and other network efforts, as well as all the participants who enrolled in these important research studies.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02514265 - MAPP Research Network: Trans-MAPP Study of Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain: Symptom Patterns Study (SPS)

References:

- 1.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. AUA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. J Urol 2011;185:2162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieger JN, Nyberg L Jr., Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. Jama 1999;282:236–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemens JQ, Clauw DJ, Kreder K, et al. Comparison of baseline urological symptoms in men and women in the MAPP research cohort. J Urol 2015;193:1554–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Afari N, et al. Widespread Psychosocial Difficulties in Men and Women With Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes: Case-control Findings From the Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network. Urology 2015;85:1319–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA, et al. The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology male study. J Urol 2013;189:141–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Ackerman AL, et al. Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: insights from the MAPP Research Network. Nat Rev Urol 2019;16:187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afari N, Buchwald D, Clauw D, et al. A MAPP Network Case-control Study of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Compared With Nonurological Pain Conditions. Clin J Pain 2020;36:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKernan LC, Walsh CG, Reynolds WS, et al. Psychosocial co-morbidities in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain syndrome (IC/BPS): A systematic review. Neurourology and urodynamics 2018;37:926–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Kusek JW, et al. The MAPP research network: a novel study of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. BMC Urol 2014;14:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Comparison of Models for the Analysis of Intensive Longitudinal Data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2020;27:275–297. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landis JR, Williams DA, Lucia MS, et al. The MAPP research network: design, patient characterization and operations. BMC Urol 2014;14:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naliboff BD, Stephens AJ, Lai HH, et al. Clinical and Psychosocial Predictors of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Symptom Change in 1 Year: A Prospective Study from the MAPP Research Network. J Urol 2017;198:848–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith JW, Stephens-Shields AJ, Hou X, et al. Pain and Urinary Symptoms Should Not be Combined into a Single Score: Psychometric Findings from the MAPP Research Network. J Urol 2016;195:949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology 2009;74:983–7, quiz 987 e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ Jr., et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology 1997;49:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthén LKaM BO Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles CA: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens-Shields AJ, Clemens JQ, Jemielita T, et al. Symptom Variability and Early Symptom Regression in the MAPP Study: A Prospective Study of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. J Urol 2016;196:1450–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai HH, Jemielita T, Sutcliffe S, et al. Characterization of Whole Body Pain in Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome at Baseline: A MAPP Research Network Study. J Urol 2017;198:622–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullins C, Bavendam T, Kirkali Z, et al. Novel research approaches for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: thinking beyond the bladder. Transl Androl Urol 2015;4:524–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickel JC. Management of chronic urologic pain: When the traditional model fails, ask your friends for help. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l’Association des urologues du Canada 2018;12:S145–S145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavorgna L, Di Tella M, Miele G, et al. Online Validation of a Battery of Questionnaires for the Assessment of Family Functioning and Related Factors. Frontiers in psychology 2020;11:771–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallejo MA, Jordán CM, Díaz MI, et al. Psychological Assessment via the Internet: A Reliability and Validity Study of Online (vs Paper-and-Pencil) Versions of the General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) and the Symptoms Check-List-90-Revised (SCL-90-R). J Med Internet Res 2007;9:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. MAPP Research Network masthead.

Appendix B. Descriptive statistics and RSample statistics and RDSEM methods.