Abstract

Context:

Outcomes after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) remain poor. We have spent 10 years investigating an “informed assent” (IA) approach to discussing CPR with chronically ill patients/families. IA is a discussion framework whereby patients extremely unlikely to benefit from CPR are informed that unless they disagree, CPR will not be performed because it will not help achieve their goals, thus removing the burden of decision-making from the patient/family, while they retain an opportunity to disagree.

Objectives:

Determine the acceptability and efficacy of IA discussions about CPR with older chronically ill patients/families.

Methods:

This multi-site research occurred in three stages. Stage I determined acceptability of the intervention through focus groups of patients with advanced COPD or malignancy, family members, and physicians. Stage II was an ambulatory pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the IA discussion. Stage III is an ongoing phase 2 RCT of IA versus attention control in inpatients with advanced chronic illness.

Results:

Our qualitative work found the IA approach was acceptable to most patients, families, and physicians. The pilot RCT demonstrated feasibility and showed an increase in participants in the intervention group changing from “full code” to “do not resuscitate” within 2 weeks after the intervention. However, Stages I and II found that IA is best suited to inpatients. Our phase 2 RCT in older hospitalized seriously ill patients is ongoing; results are pending.

Conclusions:

IA is a feasible and reasonable approach to CPR discussions in selected patient populations.

Introduction

This manuscript represents a culmination of nearly 15 years of collaboration amongst the authors initiated by Dr. J. Randall Curtis. It is offered with our deepest gratitude to Dr. Curtis for his scientific expertise, intellectual generosity, and lifelong inspiration to us individually and collectively.

Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) efficacy has been a quality and research focus since the 1960’s,(1) but outcomes after CPR remain poor. Pivotal to informing the work presented herein was a 14-year (1992–2005) epidemiologic study utilizing Medicare data to assess outcomes after in-hospital CPR that found an overall unchanging survival rate to hospital discharge of only 18.3%, an increase in CPR prior to in-hospital death, and a decrease in the proportion of CPR survivors discharged home.(2) Subsequent research investigating CPR outcomes among patient subgroups with chronic illnesses (COPD, malignancy, congestive heart failure [CHF], diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or cirrhosis) found that long-term survival among CPR recipients was substantially shorter for patients with than without chronic illness, and ≤2% of those with advanced COPD, CHF, malignancy, or cirrhosis were discharged to home and survived at least 6 months without hospital readmission.(3) A recent meta-analysis including 40 studies from 1985–2018 corroborated these findings, reporting a one-year survival after in-hospital CPR of 13.4% across all CPR recipients.(4)

Despite low success rates, CPR is the ‘default’ intervention among hospitalized patients suffering cardiac arrest unless they consent to opt out (e.g. do not resuscitate [DNR]). Compounding the issues intrinsic to defaults in healthcare(5) is the inaccurate portrayal of CPR in lay media with actors often recovering quickly and fully. This may explain, in part, why patients perceive CPR as life-saving and believe that survival is >50%.(6, 7) Furthermore, for clinicians CPR represents a final opportunity to potentially save a life and thus, despite demonstrably poor outcomes, they may be reluctant to proactively engage with patients in informed decisions about forgoing CPR. Additional challenges include the generally low quality of communication between physicians and seriously ill patients, a topic Dr. Curtis has devoted much of his career to addressing via rigorous, high quality research.(8–13)

This confluence of poor CPR outcomes in specific clinical contexts, deep and nuanced understanding of the burden decision-making can impose on patients and families,(9, 14, 15) and expertise in medical ethics became the nidus for a new concept of discussing withholding certain forms of life support that Curtis and Burt termed ‘informed assent (IA).’(16) IA seeks to balance the ethical tensions between appropriate beneficence and inappropriate medical authoritarianism by simultaneously offering full information to patients and families and removing decision-making burdens around specific, generally expected, therapeutic interventions such as CPR. IA should only be applied when there is high clinical certainty by clinicians about outcomes associated with CPR for the individual patient, and patients must be given an opportunity to ‘opt in’ in deference to patient autonomy.(17)

In 2009, Drs Curtis, Stapleton, Ford, and Engelberg began strategizing how to investigate the novel IA approach to CPR discussions. Building on our research in CPR epidemiology, communication skills, and patient/family outcomes associated with end-of-life decision making, we began the journey to ultimately conduct a multi-site randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the then undefined ‘IA intervention’. Herein we present the methods and results associated with developing the intervention and the current protocol for our ongoing RCT. The fundamental principles supporting the RCT are twofold. First, communication with patients/families about life-sustaining therapies is frequently absent or inadequate and may cause harm in the form of stress and anxiety.(18–20) Second, due to inadequate communication, we too often offer non-beneficial and potentially burdensome therapies to patients extremely unlikely to benefit. This leads to patients receiving undesired therapies and may increase patient/family symptoms of depression, anxiety, and decisional regret. We present our work temporally in ‘stages’, each with its own methods and results.

STAGE 1. FORMATIVE STAGE USING A QUALITATIVE APPROACH

Overview

From the outset, we conceptualized the IA intervention for CPR as a physician-directed discussion with patients with advanced chronic illness and their surrogates, including an emphasis on patient values and understanding, along with a statement indicating that CPR would not be performed unless the patient valued life at all costs (‘vitalist’). The goal of the IA formative stage was to test the acceptability and response to this framing of an IA discussion. As patients have diverse needs, we used an unscripted approach allowing flexibility in addressing framework elements (Table 1). We conducted focus groups and key informant interviews with patients, families, and physicians to whom we presented a video that we created of a physician-actor performing an IA discussion as if the camera were a patient.

Table 1:

Initial Framework of Informed Assent Discussion about CPR

| 1. Elicit patients’ values and preferences for therapies and outcomes. |

| 2. Define and describe cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) process. |

| 3. Provide a personalized explanation about the lack of achieving any reasonable therapeutic goal with CPR (i.e., why patient is a poor candidate for CPR due to the underlying illness). |

| 4. Inform patient that CPR will not be offered (except in the rare circumstance where patient indicates in step 1 that they are a vitalist). |

| 5. Assess patient’s understanding of the discussion, during which patients can actively disagree and request that CPR be performed. |

Participants

Patients, family members, and physicians were recruited from three sites: University of Vermont (UVM, Burlington, VT); Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC, Charleston, SC); and University of Washington (UW, Seattle, WA). Adults with oxygen-requiring COPD or advanced malignancy felt by physicians to have life expectancy <2 years, had not already decided to forgo CPR (i.e. did not have a DNR order), and were not on hospice were eligible. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English sufficiently to participate in focus groups or lacked decisional capacity. Patients were identified by their pulmonary or oncology physicians. Participants could ask a loved one to participate, but this was not required. Physicians (pulmonologists, oncologists, primary care) were recruited by email. All patients and family completed written informed consent; a waiver of written informed consent was granted for physician participants.

Measures and Data Collection

Focus group participants were shown the IA video and then asked to respond to open-ended questions (Table 2), as well as follow-up probes to these questions, posed by focus group leaders. These questions were designed to elicit participants’ perceptions of the acceptability of the IA discussion. All focus groups occurred in an ambulatory setting between December 2010 and September 2011 and were conducted by experienced, non-clinical facilitators and observed by a notetaker. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an experienced transcriptionist.

Table 2:

Questions Posed During Patient/Family and Physician Focus Groups

| Patients and Family Members |

|

|

| 1. What are your thoughts about the approach you just observed to in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)? |

| 2. How did what you just heard make you feel? |

| 3. Would you want this type of approach to in-hospital CPR for yourself or your loved one? Why or why not? |

| 4. If you were to receive this kind of news, who would you want to deliver it to you? Why? |

| 5. Would you be willing to participate in a study in which you might receive this approach to discussing CPR? |

|

|

| Physicians |

|

|

| 1. What are your thoughts about the approach you just observed to in-hospital CPR? |

| 2. How do you think your patients would react to this approach regarding in-hospital CPR? |

| 3. How did what you just heard make you feel? |

| 4. Please describe your thoughts about using this type of approach with the patients you take care of who are chronically ill with reduced life expectancy. |

| 5. Who do you think should deliver this news (i.e., perform this informed assent intervention) to appropriate patients? |

| 6. Is there anything we should change about what was said for our future research? |

| 7. Would you be willing to have your patients participate in a randomized trial that uses this “informed assent” approach? |

Analysis

Focus group data were analyzed using content analytic techniques.(21) Using an iterative, deductive approach with consensus from the multi-disciplinary investigative team, we initially developed a codebook guided by IA principles and acceptability domains (preferred clinician, setting, timing). The codebook was aligned with interview guide content including the following domains: 1) attitudes toward death and potential impact on CPR process, 2) attitudes toward initiating discussions about CPR, 3) barriers and facilitators to CPR discussion, and 4) preferences about the context (e.g., clinician, setting, timing) of discussion. Six investigators (RDS, DWF, TWM, PRM, RAE, KRS) collaboratively coded an initial group of three transcripts in order to refine and finalize the code book (e.g., identifying additional codes/themes, collapsing/combining similar codes, refining code/theme definitions). The final code book was then applied to all transcripts by two independent coders each. Finally, the themes that were both deductively and inductively identified in the coded transcripts were reviewed by the team, providing a final summary of participants’ perspectives on IA.

Results

Thirty patients (10 at each site) and 20 family members were enrolled. Focus group size ranged from 1 to 8 patient/family participants. Participants were 48% women, 60% white, 32% Black, 6% multiracial, and 2% unknown race. One focus group with 5 physicians was conducted at each site (15 total). Main themes emerging from the focus groups are shown in Table 3, with example quotes.

Table 3:

Main Themes and Example Quotes Emerging from Patient/Family and Physician Focus Groups

| Patient and Family Member Themes | Patient and Family Example Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Patients commonly do not discuss CPR with their clinicians | “I have to talk to my doctor…she didn’t explain it the way it should have been explained.” “So I haven’t [talked to my doctor]; I haven’t even thought about this.” |

| 2. Patients and families value honesty and comprehensive sharing of information | “Oh, I think she was right on. She was very honest…” “I like the way the doctor came and told the patient what she’s up against.” “The level of honesty and respect that the doctor had…that’s very important to me.” |

| 3. Poor outcomes associated with CPR are not commonly known | “Wow! That’s an eye-opener.” “Your mind is programmed, you know, we see it on TV and stuff. They guys either lives or dies and um…I didn’t know that your ribs could be broken …your chances of survival are …so poor |

| 4. Patients and families often agree with clinician recommendations but want to remain in control of their choices | “I don’t think that’s the doctor’s prerogative…” “Leave it up to the patient. Let the patient decide.” “What I think she could’ve done, was not be so definitive; ‘Do you want more information about your choices?’ You know, to give the patient more opportunity to make a decision.” |

| 5. Most are comfortable with the framing of the informed assent approach but highlight the importance of bedside manner and empathy | “Very cold and aloof.…Just show that you care about your patient……Hold my hand!” “I didn’t like the punch line. Get a second opinion.” “I’ve never heard a physician be that clear or upfront with a patient.” “I think it was a good approach. I think it’s always, um, best for a doctor to be as straightforward and honest with you. You know – this is how it is, instead of beating around the bush.” “The approach was really good because she gave all the information that she needed to make the decision whether she would like to be resuscitated or not. The fact that she probably won’t go home. They could probably actually hurt her, rather than make her better.” |

| 6. There was strong preference that one’s trusted physician deliver the recommendation | “I’m pretty close to my primary care doctor (some cases…oncologist/cardiologist), so I think she would be the one I’d want to talk to…first.” “And that (relationship) plays a big factor because you actually trust these individuals….to have the conversation” |

| 7. Faith/spirituality play an important role in participant reactions to discussions about CPR and other healthcare decisions | “I think everybody should be brought back and every possible thing should be done to keep somebody alive.” "I ultimately feel that it’s Gods decision if we live or die, how we are going to die. It’s going to be ultimately his decision whether he wants to go ahead and take you or whatever the case may be “It’s all about prayer for me.” “Doctors can say one thing, but the Lord has got something else in store…” |

|

| |

| Physician Themes | Physician Example Quotes |

|

| |

| 1. Physicians vary in their attitudes about informed assent with some considering this as an appropriate approach and others believing it is too paternalistic | “It’s a paternalistic approach, but there are times when you need to pull out paternalism.” “I liked how you framed it in the context of what is important to the patient.” “Rather than assent I almost prefer … advise and consent. I’m very happy to advise the patients if they want to, but then it’s them and their family that decide that consent.” “I don’t mind having these conversations, I think they’re great to have and I don’t mind informed ascent with somebody who I have a relationship that I’ve known” “It sounds very heavy handed. I don’t really think people need to be told that your chances of surviving an in-hospital arrest and going on to a functional life expectancy is in the 2–3% range” |

| 2. Physicians vary in their current practices of informed assent | “Well, it’s similar to what I do [for] somebody I don’t feel will benefit, I will let them know that I think that, you know, that’s a therapy that’s out there but it’s therapy that I don’t recommend.” “I’m going to make this sounds so scary that no human being in their right mind would accept CPR” Certainly, a big departure from the way CPR is discussed in my experience.” |

| 3. The context and timing of discussion was viewed as critically important with cultural, family, and religious implications | “And you know, very frequently, it’s harder to get a do not resuscitate order from African American families because there’s like a heavy religious component” “Unless you bring the family into this discussion and everybody is on the same page, when you have a discussion. We see it all the time battles between brothers and sisters and what mom wanted what mom didn’t want. So the informed ascent is nice thing in theory[but] when the family comes into it, if they have not been part of this discussion previously, you may be totally backpedaling, no matter what your patient said.” “The other thing is also around religious and ethnic backgrounds. Case and plan, I’ve taken care of catholic patients who are near dead, and because to withdraw care would be the equivalent of suicide, and from a religious standpoint they are just not going to do this no matter what.” |

| 4. The majority of physicians want to be personally involved with these discussions for their patients and preferences may vary by specialty and setting | “I would not feel comfortable having a researcher of any variety coming in to talk to my patient.” “The person (clinician) who has the longest relationship…should have these conversations”. “It really challenges us because the whole premise of this is based on a physician-patient relationship and it’s patient-system relationship as much as anything else”. “I think that in the office or primary care setting or a continuity setting when you know people well, you know when you can have that level of discussion more easily.” “Most of the time I agree with this informed assent type of approach – but only after we have a mutual understanding, a mutual respect and know the patient and the family very, very well. In oncology it might be, ah, a little bit different from the emergency room or ICU setting”. |

Conclusions

This formative stage provided invaluable information about conduct of the IA intervention and affirmed that most patients and family accepted the approach. Participants also appreciated honesty, empathy, trust, and choice throughout this process, and generally felt that the assent statement was acceptable, as was the case with most physicians. Religious, racial, and cultural issues, in addition to having this conversation with physicians who had the most engaged or long-lasting relationship with the patient, were important to both patients and physicians. These results informed our development of a pilot RCT in ambulatory patients with advanced COPD or malignancy. Importantly, the focus groups provided insights into potential pitfalls that we would subsequently encounter in the next stage of our efforts and suggested that race may influence response to informed assent given the high importance of faith and spirituality among African Americans.(22)

STAGE 2. PILOTING THE RCT

Methods and Results

Our pilot RCT (NCT01558817) of the IA intervention versus usual care occurred from 2012 – 2014 among 29 outpatients (mean age 69.7 years) with advanced COPD or malignancy recruited from pulmonary and oncology clinics at the three study sites. The IA intervention was performed by trained physician discussionists, and the control group received usual care plus an informational brochure about CPR from study staff. Potential participants were excluded if they already had a DNR order prior to the intervention, 1/14 (7.1%) patients in the intervention group and 4/15 (26.7%) patients in the usual care group completed their baseline questionnaire stating that they did not want CPR. The primary endpoint was the difference in the proportion of patients not wanting CPR 2 weeks after the intervention, assessed by questionnaire (Table 4). We also aimed to demonstrate feasibility via enrollment and questionnaire completion rates. Significantly more intervention participants did not want CPR at the 2-week assessment (7/12 [58%] vs. 13/15 [87%], p=0.01). No significant differences were observed in patient-reported anxiety or depression symptoms, but the study was not powered as such. We also found that the intervention was feasible and well received by patients and family members.

Table 4.

Results of Informed Assent Pilot RCT in 29 Outpatients

| Interventiona | Control | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment (n=14) | 2 weeks (n=12) | Enrollment (n=15) | 2 weeks (n=15) | ||

| Proportion wanting CPR | 13/14=92% | 7/12=58% | 11/15=73% | 13/15=87% | 0.01 |

| Initially wanting CPR, changed to “not wanting CPR” |

-- | 4/11=36% | -- | 0/11=0% | 0.045 |

| Depressive symptoms, PHQ9(41–46) | 3.0±3.0 | 1.9±2.5 | 5.5±4.8 | 3.8±3.4 | 0.17 |

| Anxiety Symptoms, GAD7(47–49) | 2.1±2.9 | 1.6±2.5 | 2.5±3.7 | 3.1±4.2 | 0.29 |

2 of 14 intervention patients died before follow up assessment. Neither received CPR. Abbreviations: PHQ9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9); GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire.

Two critical findings emerged from this pilot outpatient RCT. First, patients hospitalized before participation wished they had received such a discussion during hospitalization. Second, IA is best suited to inpatients, as outpatients preferred their own ambulatory physicians for this type of discussion. With this knowledge, we then conducted a 6-patient inpatient pilot study to demonstrate recruitment feasibility to secure NIH funding for our proposed phase 2 RCT.

STAGE 3: ONGOING MULTISITE PHASE 2 RCT OF THE INFORMED ASSENT INTERVENTION

Methods

Refining and finalizing the IA intervention:

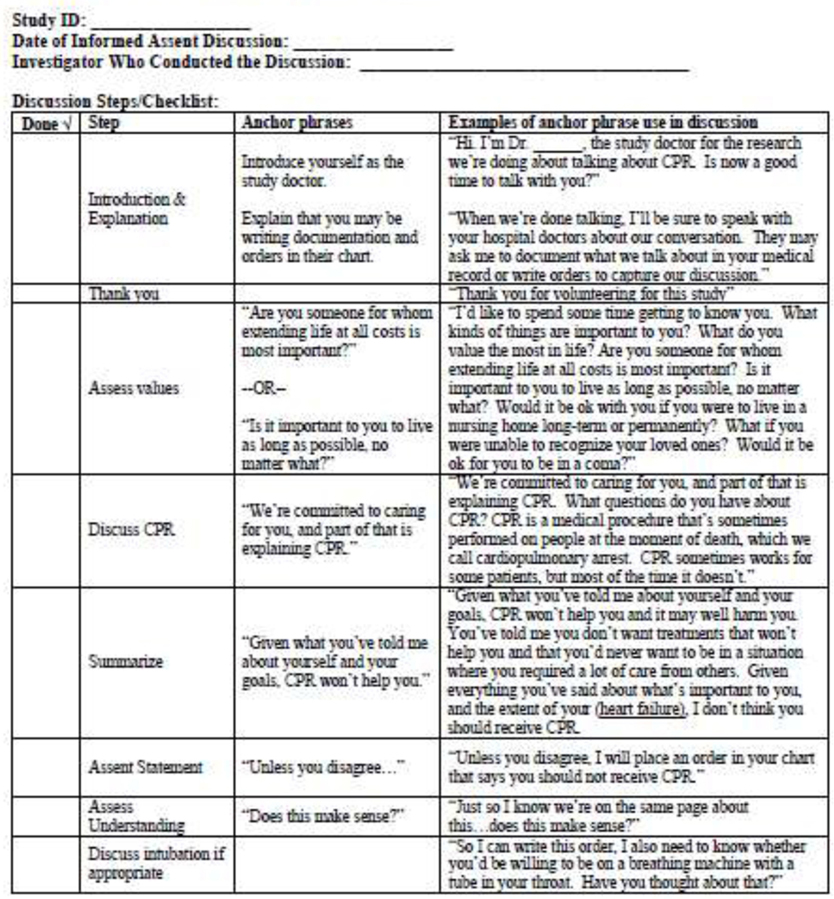

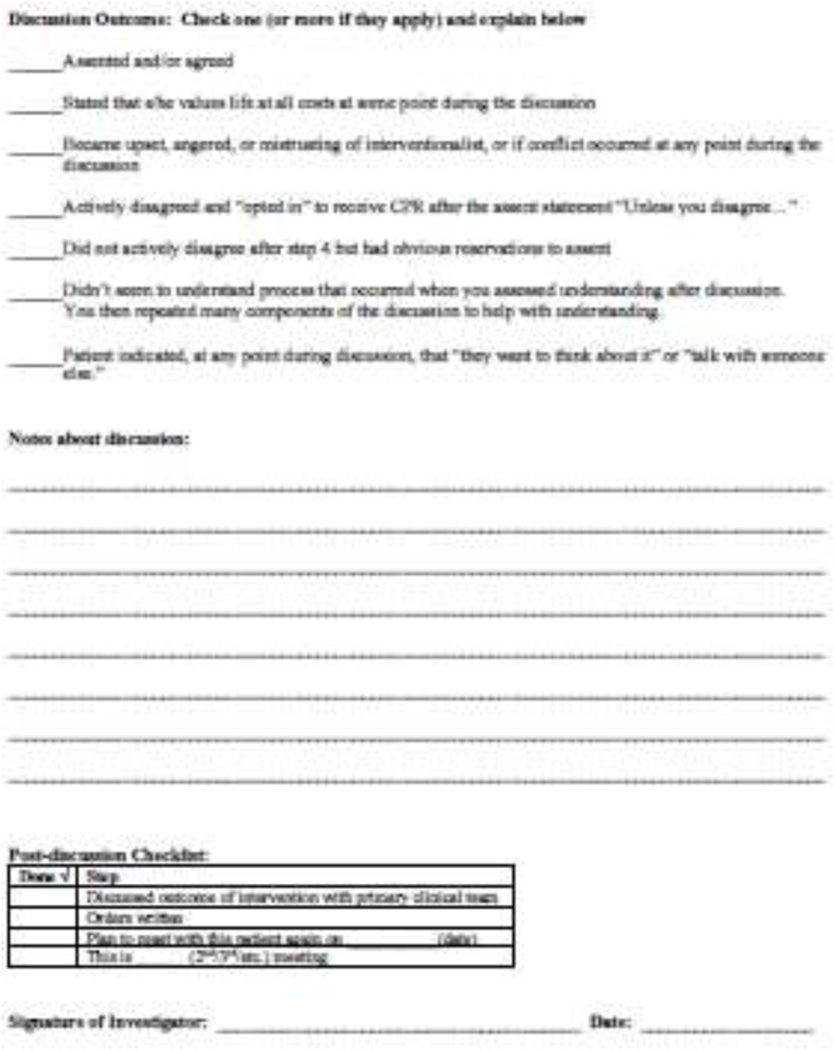

With NIH funding, our study team met in person for 2 days to refine the IA intervention and train for the upcoming RCT. The meeting objectives were to 1) standardize the IA intervention approach and 2) establish methods to ensure consistency across and within sites. All study investigators spent approximately 4 hours with Dr. Anthony Back, who guided an iterative interactive group workshop to standardize the IA discussion with what we ultimately termed “anchor phrases.” The workshop utilized the framework in Table 1 and systematically discussed options for phrases to be used by all discussionists at each step, arriving at consensus on the anchor phrases (Figure 1). Discussionists then spent several additional hours practicing the IA intervention using the anchor phrases to demonstrate mastery of required skills, as has been used in prior studies.(23) At the workshop’s conclusion, we had formulated the Discussionist Checklist shown in Figure 1 and had practiced implementation of the intervention. This checklist serves as a discussionist guide in our ongoing RCT and contains the required anchor phrases as well as examples of their use. Discussionists are trained to always use the anchor phrases to ensure fidelity to the IA concept and consistency across sites.

Figure 1:

Informed Assent Discussion Guide/Checklist

Study Design:

We are conducting a phase 2 multicenter RCT of the IA intervention versus usual care with attention control in older hospitalized patients with underlying serious illness (NCT02984124), funded by the National Institute on Aging. Recruitment began in late 2016 and is occurring at UVM, MUSC, and University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill; UW was an enrolling site until 2020.

Participants:

Table 5 shows eligibility criteria for patient participants. Family members are also included if they are English-speaking adults who can participate in study measures and the patient requests their participation.

Table 5.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Study Entry

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. ≥65 years old 2. English speaking 2. Currently hospitalized 3. Able to make decisions for oneself 4. Life limiting illness or severe functional impairment. Must have one or more of the following: a) Chronic life-limiting illness with median survival ≤2 years defined as: 1) metastatic cancer or inoperable lung cancer; 2) COPD requiring oxygen; 3) New York Heart Association Class III or IV heart failure; 4) Child’s Class C cirrhosis or baseline MELD score of ≥20, 5) end stage renal disease (must be on dialysis and ≥75 years old); 6) advanced pulmonary fibrosis/interstitial lung disease; and 7) advanced pulmonary hypertension b) Severe functional impairment defined as dependence with ≥4 activities of daily living (ADLs) on Katz Index of Independence in ADLs.(50, 51) |

1. Has already definitively chosen DNR status 2. Unable to provide informed consent 3. Refused consent 4. Currently listed on a transplant list (awaiting transplant) 5. Inappropriate for study enrollment per attending physician 6. Research team unavailable to perform study intervention |

Participant screening and consent:

Eligibility is determined by daily screening at sites by trained research staff and once confirmed, the participant is approached for informed consent. This study is approved by Human Subjects Committees at each site.

Randomization:

Consented participants are randomized through an electronic system in a 1:1 ratio using random variable (undisclosed) block sizes and stratified by center.

Study intervention:

IA discussions with participants and their family members randomized to the intervention arm are performed while participants are in the hospital by trained physician discussionists experienced in palliative care (Figure 1). After the intervention is complete, any decisions about life-sustaining treatments are communicated with the participant’s clinical team.

Intervention fidelity:

All IA discussions are audiotaped (with participant consent). The first 5 discussions at each site were reviewed by two non-discussionist investigators (RAE and CSR) to assess deviations from anchor phrasing (Figure 1). These deviations were communicated by both email and at monthly teleconferences where physician discussionists identified solutions. After these first 5 discussions at each site, at least 40% of discussions are randomly selected for review and discussed with the same iterative process.

Control group:

Participants randomized to the control arm receive usual care per their treating inpatient team. Control participants also receive an unscripted “attention control” friendly visit from study staff to both enhance response rates and provide similar attention.

Outcome measures (Table 6):

Table 6:

Study Outcomes and Data Collection Protocol

| MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES | CONCEPT | DATA SOURCE & COLLECTION TIME |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome: | ||

| • Full QOC, questions answered specifically about CPR(24, 25) | Quality of communication about CPR | Patients & Families: Enrollment and hospital discharge |

|

| ||

| Secondary Outcomes: | ||

| • CANHELP questionnaire, communication domain focused specifically on CPR(52, 53) | Satisfaction with communication about CPR | Patients & Families: Enrollment and hospital discharge |

|

| ||

| • Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)(54, 55) | Depressive and anxiety symptoms | Patients & Families: Enrollment; hospital discharge; 3 & 6 months post-enrollment |

|

| ||

| • Presence of and time to DNR orders in electronic medical record | Presence of and time to DNR orders | Medical record: Throughout hospitalization and to 6 months |

|

| ||

| • Hospital and ICU admission/length of stay, mechanical ventilation, CPR, tracheostomy, hemodialysis, gastrostomy, ED visits, clinic visits, skilled nursing facility, home health care(27–29, 31, 56, 57) | Intensity of care during index hospitalization, health care utilization, costs of care | Medical record: Throughout hospitalization and to 6 months Patients & Families: 3 and 6 months post-enrollment |

|

| ||

| • Inpatient and ICU admissions, outpatient and emergency visits, skilled nursing facility care, and home health care visits | Healthcare utilization | Patients, Families: 3 and 6 months post-enrollment |

The primary outcome is patient-assessed quality of communication about CPR measured by the QOC (Quality of Communication) questionnaire at hospital discharge.(24, 25) We also examine the intervention’s efficacy for increasing satisfaction with communication about CPR and the presence of DNR orders; and reducing time to DNR orders, intensity of care (26–28), and health care utilization. Assessments occur at enrollment and hospital discharge, and we also evaluate for enduring effects by measuring patient-assessed depression, anxiety, and health care utilization at 3 and 6 months after enrollment via phone calls to patients and families.

Additional measures and data collected:

Additional measures include descriptive, demographic, and medical history information. We also ask patients and family members a single item about perception of coercion (“During this study, how free did you feel to choose CPR if you wanted to receive it?”), and we assess respondent burden of study questionnaires. Finally, among loved ones of patients who die, we ask a single-item validated measure of patient’s quality of dying and death, (29–35) as well as information about any life-sustaining measures that the patient may have received prior to death (including CPR and/or mechanical ventilation).

Sample size:

To calculate sample size, we conservatively assumed an 80% patient completion rate of the hospital discharge QOC assessment. An enrolled sample size of 180 (144 evaluable patients with a follow-up assessment [72 in each group]) will provide 92% power to detect the same degree of improvement in QOC score as seen in a prior study in COPD patients using the QOC, with a two-tailed α=0.05.(36) However, as discussed below, we have unexpectedly encountered some degree of informative censoring with more patients withdrawing from the intervention than usual care group, so we have received IRB and DSMB approval to enroll until we achieve 72 patients in each group with a measured primary outcome, and we anticipate enrolling a maximum of 200 patients.

Statistical analyses:

All primary analyses will be based on intention to treat and will be 2-tailed, with p-values < 0.05 considered significant. As all secondary outcomes will be considered hypothesis-generating, we will not correct for multiple comparisons in this phase II exploratory trial. Two-sample t-tests will be used to make comparisons between groups. Time to event outcomes will be examined using log-rank approaches with extension to Cox proportional hazard models to examine the impact of baseline or confounding measures. Since missing data may arise at the item level and at the subject level due to attrition, the pattern and potential mechanism of missing data will be explored, and if >10% of data are missing, imputation methods will be used.

Results

We have currently enrolled 169 participants (intervention, n=84; usual care, n=85). Given this very ill population, we have not surprisingly been unable to obtain outcome data on all patients due to factors including death, worsening illness, and unwillingness to continue participation. Our current rate of primary outcome obtainment is 86.1%. When designing this trial, we expected that participants in the usual care group might drop out more often than in the intervention group due to knowledge that they were only receiving standard care, but we have actually encountered the opposite with informative censoring observed in our intervention group (when research subjects withdraw or are lost to follow-up for reasons related to the study itself).(37) We anticipate completing recruitment for this RCT by mid-2022.

Discussion:

To our knowledge, these studies are the first investigations of informed assent, a novel ethical paradigm for CPR discussions with seriously ill, hospitalized patients. Our work is an important innovation, buttressed by systematic and rigorous scientific development. There have been numerous insights obtained during each stage of our work including the development and implementation of our ongoing phase 2 RCT.

While our qualitative research in outpatients with advanced COPD or cancer found general acceptance of the IA approach, it was not universal and there were important caveats. A reasonable synopsis from our focus group participants is the critical importance of patient-centeredness when broaching CPR, including foundational communication and therapeutic rapport skills such as empathy, honesty, respect for patient values, autonomy, and the physician-patient relationship.(38) Commensurate with prior literature, patients were unaware of the poor outcomes associated with CPR.(6, 7) Physician focus group participants were more divided in their acceptance of IA, with some acknowledging they already deployed this approach and others believing it was too paternalistic. Thus, physician acceptance of IA, along with the knowledge and skill to apply this approach, is an important future direction.

We then performed our pilot RCT, also in outpatients, and the three discussionists (RDS, DWF, JRC) found the IA intervention a challenging approach in an ambulatory population, primarily due to absence of the physician-patient relationship and some hesitancy among discussionists to fully deploy IA as we’d envisioned. For these reasons, as well as our observational research on CPR outcomes among hospitalized patients, we pivoted to the inpatient care setting for Stage 3, our phase 2 RCT.

Curiously, while our pilot ambulatory RCT identified the importance of a physician-patient relationship to CPR discussions, this has generally not emerged in our ongoing phase 2 RCT among inpatients. Reasons for this are unclear but may include implicit patient acceptance to discuss CPR while hospitalized, understanding that hospital physicians may be different than one’s ambulatory providers with a shorter-term relationship, greater patient and treating physician acknowledgement that there may be ongoing clinical deterioration while hospitalized, and a more seriously ill cohort due to a combination of acute and chronic illness. Regardless of reasons for this contrast, it is apparent that clinical context and care setting are highly relevant to the application of IA.

Patient recruitment and data collection are ongoing for the phase 2 RCT but important observational insights have emerged over the last 5+ years. Perhaps most provocative is the rate of informative censoring among patients randomized to the IA intervention, as we have unexpectedly encountered an increased rate of withdrawal in the intervention compared with the usual care group, initiated by either participants themselves or by physician discussionists. For example, several participants in the intervention group have withdrawn from the RCT due to receipt of bad news from their clinical team and subsequent desire to discontinue research participation, unwillingness to continue after the discussion itself, or input from family members who objected to participation even after informed consent and randomization. Additionally, a few participants have been withdrawn by physician discussionists who found them to lack decisional capacity when arriving at the bedside to perform that IA discussion. Notably, participants randomized to the usual care group are unlikely to withdraw from the trial for the above reasons. While there are no methods to correct or repair bias introduced by informative censoring, we have added statistical techniques to impute data if needed and perform sensitivity analyses.(39, 40) Additionally, we have modified our protocol to enroll participants until we accrue 72 in each group with a measured primary outcome.

Another challenge has been ensuring intervention fidelity. Based on audits of audiotaped discussions (data not shown), some minor drift slightly away from adherence to specific anchor phrases during the IA discussion has required steady reinforcement to maintain intervention fidelity. We have successfully addressed this in an iterative fashion as described above. However, this mild tendency amongst a highly skilled and specially trained group of physician discussionists serves to highlight future challenges in the dissemination and wider uptake of the IA approach.

Our findings offer important and novel insights into CPR discussions but we do acknowledge additional limitations. While each Stage has been a multi-site study and we have reasonable geographic distribution of sites (Northeastern, Southeastern, and Northwestern US), it is unlikely results are nationally representative. Additionally, IA represents a shift in the generally accepted paradigm of CPR discussions with hospitalized patients, so ethical and safety considerations have been important and are monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

In summary, we believe our initial findings and current RCT protocol related to the evolution of investigating an IA approach to CPR discussions provide important new insights and help inform future directions for this important topic and palliative and end-of-life care. We are indebted to Dr. Curtis for this support of and influence on this work.

Supplementary Material

Key Message:

This article describes a three Stage approach to developing and evaluating a novel approach to discussing cardiopulmonary resuscitation among older hospitalized patients with advanced chronic illnesses, termed ‘informed assent’, in which CPR is not routinely offered as standard care.

Acknowledgements:

With immense professional love and gratitude, we wish to acknowledge Dr. Randy Curtis for the crucial role he has selflessly played in this body of work for 15 years. Were it not that this issue of JPSM in honor of him is a surprise, he would have been a co-author of this manuscript. Randy has been an extraordinary mentor, sponsor, coach, and friend, and we are forever grateful that he has made us better academicians, researchers, physicians, and human beings.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center (grant title “Changing the paradigm of CPR: Exploring Informed Assent”) and the National Institutes of Health (R01AG050698).

Disclosures: RDS, DWF, ELN, KKT, and RAE were supported by both the National Palliative Care Research Center and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for this research. KRS, SD, and EM were supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center for this research. NRN, SSC, KLC, EKK, RCM, JMM, JJE, PRM, AO, CSR, BW, SSA, MB, SB, SC, SRP, and CR were supported by the NIH for this work. SA, ALB, JA, and TWM have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Renee D. Stapleton, Pulmonary and Critical Medicine, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, HSRF 222, Burlington, VT 05452 USA.

Dee W. Ford, Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine Medical University of South Carolina 96 Jonathan Lucas St CSB 816, MSC 630 Charleston, SC 29425 USA.

Katherine R. Sterba, Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Nandita R. Nadig, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, IL.

Steven Ades, Hematology and Oncology University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine Burlington, VT.

Anthony L. Back, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Shannon S. Carson, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC.

Katharine L. Cheung, Nephrology, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington, VT.

Janet Ely, University of Vermont Cancer Center, Burlington, VT.

Erin K. Kross, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine Co-Director of Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at UW Medicine University of Washington Seattle, WA.

Robert C. Macauley, Oregon Health Sciences University Portland, OR.

Jennifer M. Maguire, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC.

Theodore W. Marcy, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine Burlington, VT.

Jennifer J. McEntee, Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Associate Professor, Palliative Care and Hospice Medicine University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC.

Prema R. Menon, Associate Medical Director, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Boston, MA.

Amanda Overstreet, Geriatrics and Palliative Care Medical University of South Carolina Charleston, SC.

Christine S. Ritchie, Harvard Medical School Boston, MA.

Blair Wendlandt, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC.

Sara S. Ardren, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine Burlington, VT.

Mike Balassone, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

Stephanie Burns, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington, VT.

Summer Choudhury, North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Sandra Diehl, University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, VT.

Ellen McCown, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

Elizabeth L. Nielsen, Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at UW Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Sudiptho R. Paul, Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at UW Medicine University of Washington Seattle, WA.

Colleen Rice, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC.

Katherine K. Taylor, Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine Medical University of South Carolina Charleston, SC.

Ruth A. Engelberg, Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at UW Medicine University of Washington Seattle, WA.

References:

- 1.https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the-guidelines/getwith-the-guidelines-resuscitation, accessed Dec. 27, 2021.

- 2.Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2009;361:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stapleton RD, Ehlenbach WJ, Deyo RA, Curtis JR. Long-term outcomes after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in older adults with chronic illness. Chest 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schluep M, Gravesteijn BY, Stolker RJ, Endeman H, Hoeks SE. One-year survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2018;132:90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marco CA, Larkin GL. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: knowledge and opinions among the U.S. general public. State of the science-fiction. Resuscitation 2008;79:490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez L, Diaz J, Alshami A, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in television medical dramas: Results of the TVMD2 study. Am J Emerg Med 2021;43:238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. Jama 2013;310:2271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-Life Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1484–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford DW, Downey L, Engelberg R, Back AL, Curtis JR. Discussing religion and spirituality is an advanced communication skill: an exploratory structural equation model of physician trainee self-ratings. J Palliat Med 2012;15:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a Patient and Clinician CommunicationPriming Intervention on Patient-Reported Goals-of-Care Discussions Between Patients With Serious Illness and Clinicians: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:930–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevick SA, Lord AS. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Complicated Grief are Common in Caregivers of Neuro-ICU Patients. Neurocrit Care 2017;26:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis JR, Burt RA. Point: the ethics of unilateral “do not resuscitate” orders: the role of “informed assent”. Chest 2007;132:748–51; discussion 755–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The Importance of Addressing Advance Care Planning and Decisions About Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders During Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA 2020;323:1771–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2014. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. In. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner JS, Roth J. Avoiding iatrogenic harm to patient and family while discussing goals of care near the end of life. J Palliat Med 2006;9:451–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Emotional numbness modifies the effect of end-of-life discussions on end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:841–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Sinclair S, Horst G. A knowledge synthesis of culturally- and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: findings from a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Ciechanowski PS, Downey L, et al. Development and evaluation of an interprofessional communication intervention to improve family outcomes in the ICU. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33:1245–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JR. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1086–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnato AE, Cohen ED, Mistovich KA, Chang CC. Hospital End-of-Life Treatment Intensity Among Cancer and Non-Cancer Cohorts. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, et al. Development and validation of hospital “endof-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care 2009;47:1098–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnato AE, McClellan MB, Kagay CR, Garber AM. Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Health Serv Res 2004;39:363–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2008;36:1138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:269–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick DL, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Nielsen E, McCown E. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:410–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelberg RA, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Correspondence between patients’ preferences and surrogates’ understandings for dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:498–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downey L, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Patrick DL. Shared priorities for the end-of-life period. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:175–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, et al. A measure of the quality of dying and death. Initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Au DH, Udris EM, Engelberg RA, et al. A randomized trial to improve communication about end-of-life care among patients with COPD. Chest 2012;141:726–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu M, Feng Y, Duan R, Sun J. Regression analysis of multivariate interval-censored failure time data with informative censoring. Stat Methods Med Res 2021:9622802211061668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patientcentered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fielding S, Ogbuagu A, Sivasubramaniam S, MacLennan G, Ramsay CR. Reporting and dealing with missing quality of life data in RCTs: has the picture changed in the last decade? Qual Life Res 2016;25:2977–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cro S, Morris TP, Kenward MG, Carpenter JR. Sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with missing continuous outcome data using controlled multiple imputation: A practical guide. Stat Med 2020;39:2815–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord 2004;78:131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004;42:1194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord 2004;81:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:345–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 1970;10:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. Jama 1963;185:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. Cmaj 2006;174:627–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. The development and validation of a novel questionnaire to measure patient and family satisfaction with end-of-life care: the Canadian Health Care Evaluation Project (CANHELP) Questionnaire. Palliat Med 2010;24:682–95. 1983;67:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-- a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooke CR, Hotchkin DL, Engelberg RA, Rubinson L, Curtis JR. Predictors of time to death after terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest 2010;138:289–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muni S, Curtis JR. Race and ethnicity in the intensive care unit: what do we know and where are we going? Critical care medicine 2011;39:579–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.