Abstract

The genetic systems of bacteria that have the ability to use organic pollutants as carbon and energy sources can be adapted to create bacterial biosensors for the detection of industrial pollution. The creation of bacterial biosensors is hampered by a lack of information about the genetic systems that control production of bacterial enzymes that metabolize pollutants. We have attempted to overcome this problem through modification of DmpR, a regulatory protein for the phenol degradation pathway of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600. The phenol detection capacity of DmpR was altered by using mutagenic PCR targeted to the DmpR sensor domain. DmpR mutants were identified that both increased sensitivity to the phenolic effectors of wild-type DmpR and increased the range of molecules detected. The phenol detection characteristics of seven DmpR mutants were demonstrated through their ability to activate transcription of a lacZ reporter gene. Effectors of the DmpR derivatives included phenol, 2-chlorophenol, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 4-chloro-3-methylphenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, 2-nitrophenol, and 4-nitrophenol.

Within the last few decades there has been a notable increase in government regulations that hold industries accountable for the chemical pollution that results from their manufacturing activities. In order to comply with environmental laws, industries must be able to identify contamination resulting from chemical spills and leaks and to monitor remediation processes. The chromatographic methods currently used for analysis of samples from contaminated sites are costly and technically complex (14). A potentially inexpensive and simple way to reduce the cost of contaminant detection is to use biosensors derived from the genetic systems of bacteria that use organic contaminants as growth substrates.

A whole-cell bacterial biosensor can be created by placing a reporter gene under control of an inducible promoter. Expression of the reporter gene provides a measurable response when the appropriate transcription activator protein interacts with an effector molecule to signal a particular environmental condition. Bacterial biosensors have been created to detect naphthalene (10), benzene derivatives, including toluene and xylene (1, 11, 20, 41); and certain toxic metals (20, 25).

The construction and use of bacterial biosensors has been restricted by our limited understanding of the genetic systems that control bacterial responses to polluting chemicals and by the specificity of the interaction between a transcription activator protein and its chemical effectors. However, of the known systems, several show a high degree of similarity in the regulatory pathways that control their expression. Operons carrying genes required for metabolism of phenol, toluene, benzene, and xylene in some Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species are controlled through inducible promoters recognized by ς54-associated RNA polymerase. Transcription directed by these promoters occurs when a regulatory protein detects the presence of the substrate for the catabolic enzymes. Proteins in this category are DmpR, XylR, MopR, PhhR, PhlR, and TbuT (3, 6, 16, 17, 24, 28, 29, 31). These six proteins show significant similarity to one another at the amino acid level and are organized into discrete domains with independent functions that include chemical detection, polymerase activation, and DNA binding.

XylR and DmpR are the best-characterized members of this group of transcription activators. The Pseudomonas putida XylR protein has served as the detection component for a number of biosensors (1, 11, 20, 41) based on the ability of this protein to activate transcription in response to xylene and toluene. DmpR, the product of the Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 dmpR gene (28, 29), mediates expression of the dmp operon to allow growth on simple phenols. Transcription from Pdmp, the promoter of the dmp operon, is activated when DmpR detects the presence of an inducing phenol (29).

Domain-swapping experiments to form XylR-DmpR hybrids demonstrated that the sensor activity of these regulatory proteins is localized in the amino-terminal region (29). Transcription from Pdmp depends on a direct physical interaction between the sensor domain of DmpR and the inducing phenol. A productive association between the sensor domain and a phenolic molecule causes DmpR to undergo a conformational change that results in a polymerase-activating form of the protein (18, 30).

The single-protein, independent-domain arrangement of DmpR and other proteins of this type makes them particularly suitable candidates for genetic manipulation. Specifically, one should be able to alter the chemical-sensing domain of the protein through mutagenesis without disturbing DNA-binding or transcription-activating functions. Modification of the sensor domain should allow the creation of novel proteins that respond to xenobiotics which remain undetected by the wild-type protein. Such altered proteins have the potential to extend the chemical target range of biosensors beyond that based on natural systems.

The natural interaction of DmpR with a subset of phenols suggested that modification of its sensor domain might create protein derivatives with the capacity to detect phenolic molecules commonly used in industry. Phenol and substituted phenols are common starting materials and waste by-products in the manufacture of chemical, industrial, and agricultural products (34–39). The high-volume use of phenols in the United States and their potential toxicity has led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to include 11 of them on its list of priority pollutants. Phenols listed as priority pollutants include phenol, 2-chlorophenol, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol, pentachlorophenol, 4-chloro-3-methylphenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, 2-nitrophenol, 4-nitrophenol, 2,4-dinitrophenol, and 2-methyl-4,6-dinitrophenol (9).

The magnitude of the production and use of phenolic molecules in the United States suggests that an inexpensive method of detecting these chemicals could be of use in preventing the inadvertent release of phenolic pollutants. Here, we present five DmpR mutants that were created through random mutagenesis of the DmpR sensor domain. All five of the DmpR mutants described in this report, through activation of a reporter gene, increase detection of the phenolic effectors that also generate transcription activation by wild-type DmpR. In addition, the DmpR mutants demonstrate the ability to detect phenolic molecules that are not effectors of the wild-type protein. The distribution of mutations that alter the chemical-sensing capacity of DmpR suggests that protein secondary structure, determined by the amino acid sequence of the sensor domain, normally prevents disubstituted phenols from acting as effectors of DmpR-mediated transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli TE2680 (8) was used as an intermediate strain for placing the Pdmp-lacZ fusion into the chromosome of E. coli MC4100 (5) to create a test strain (AW101) for the DmpR derivatives. DH5α (27) was the host for plasmid constructions.

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genetic characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169(φ80 lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 27 |

| TE2680 | F− λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 Δ(lac)X74 rpsL galK2 recD1903::Tn10d-Tet trpDC::putPA1303::[Kans-Camr-lacZ] | 8 |

| MC4100 | F− Δ(argF-lac)U169 thiA | 5 |

| AW101 | MC4100 trpDC::Pdmp-lacZ | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVI401 | Apr; dmpRwt-N | 21, 29 |

| pBR322 | Cloning vector; Apr Tetr | New England Biolabs |

| pRS551 | Promoter assay vector with promoterless lacZ gene; Kanr Apr | 32 |

| pAW50 | pBR322 derivative, carries wild-type or mutant versions of dmpRwt-N; Tetr | This study |

| pAW51 | pRS551 derivative, carries dmp operon promoter (Pdmp) fused to lacZ gene; Kanr Apr | This study |

Plasmid pVI401 (21, 29) served as the source of both the dmpRwt-N gene and the Pdmp promoter, which heads the divergently transcribed dmp operon. The dmpRwt-N gene includes the entire dmpR gene but contains a synthetic NdeI restriction site resulting from nucleotide changes immediately upstream from the ATG initiation codon. The coding region of dmpRwt-N is the same as that of the wild-type dmpR gene, and the response of the encoded protein to aromatic chemicals is indistinguishable from that of the wild-type protein (29).

Plasmid pRS551 (32) is a promoter assay vector that has homology to the engineered trp operon of E. coli TE2680 to allow integration of promoter-lacZ fusions into the TE2680 chromosome. pAW51 is a derivative of pRS551 that carries the dmp operon promoter Pdmp on a 0.6-kb DNA fragment fused to the pRS551 lacZ reporter gene.

Plasmid pAW50 was derived from pBR322 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Following removal of the pBR322 NdeI site, a 2.4-kb NotI fragment containing the pVI401 dmpRwt-N gene was cloned into a NotI linker which replaced the ScaI site normally located in the ampicillin resistance gene of pBR322. An EcoRI restriction digest, followed by ligation, removed the promoter of the ampicillin resistance gene, as well as the 5′ NotI site. pAW50 contains dmpR sequences extending approximately 650 bp upstream from the dmpR translation initiation site.

Genetic techniques.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by using a Plasmid Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) or by a miniprep alkaline lysis method (13). Standard methods were used for restriction digests, gel electrophoresis, and ligations (2, 27). Transformation of E. coli was accomplished by electroporation (7) with Gene Pulser II unit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Nonmutagenic PCR to amplify the Pdmp fragment was done as described by Innes et al. (12).

Plasmid pVI401 served as the template for amplifying Pdmp in a reaction that included primers Pdmp5′-EcoRI (5′-CCATCGCTGAATTCTGCAGCAACAG-3′) and Pdmp3′-BamHI (5′-CGCACACGGATCCAACGAGTGAG-3′). PCR was conducted on a Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, Calif.) 9600 thermal cycler with a 2-min denaturation step at 92°C followed by 25 cycles of 1 min each at 92, 52, and 72°C. The Pdmp PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI to allow directed cloning in front of the promoterless lacZ gene of pRS551 for creation of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion of pAW51. The 600-bp Pdmp fragment includes sequences 520 bp upstream from the transcription initiation site identified by Shingler et al. (28).

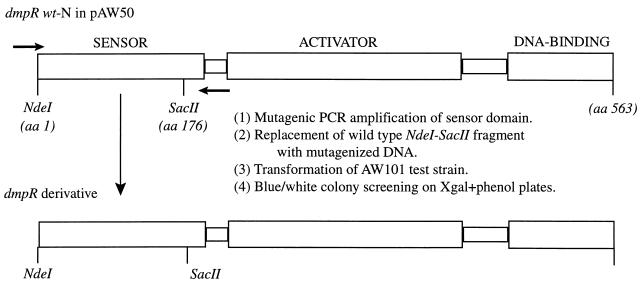

Construction of DmpR derivatives with mutant sensor domains.

The method used to create and select mutant DmpR proteins with increased responses to phenol and substituted phenols is diagrammed in Fig. 1. Mutagenic PCR of the DmpR sensor domain was conducted by a modification of Cadwell and Joyce's method (4). Plasmid pAW50 served as the template in the mutagenic PCR with 25 pmol each of primers dmpR5′-75 (5′-GCCGTCGATTGATCATTTGG-3′) and dmpR3′-976 (5′-TGTCCATCATATTGCGCACG-3′). In addition, the reaction mixture contained 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM dATP and dGTP, 0.8 mM dCTP and dTTP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.001% (wt/vol) gelatin, and 5 U of AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer). The mutagenic PCR amplification cycle followed a 2-min denaturation at 92°C and consisted of 30 cycles of 94°C (10 s), 56°C (20 s), and 72°C (1 min).

FIG. 1.

Independent domain structure of dmpRwt-N and method used to create and select DmpR mutants. aa, amino acid.

The pAW50 plasmid and the mutagenized PCR products were each digested with NdeI and SacII. The 528-bp NdeI-SacII PCR fragment contained 85% of the dmpR sensor domain. This fragment and pAW50, excluding the wild-type sensor domain, were gel purified from low-melting-point agarose by using Elutip-D columns (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.). The purified DNA fragments served as components in a ligation reaction to reassemble pAW50 derivatives carrying dmpR with variously mutated sensor regions.

DmpR mutants B24 and F17 were derived from dmpR derivatives that carried two sensor domain mutations through a nonmutagenic sequential PCR process (2). The 5′ section of B23 containing DNA corresponding to the Q10R mutation was amplified by using dmpR5′-75 (see above) and dmpR3′-420 (5′-CCTTGGCGCGTTCGATGC-3′). An overlapping wild-type DNA fragment encoding the 3′ portion of the sensor domain was amplified with primers dmpR5′-420 (5′-GCATCGAACGCGCCAAGG-3′) and dmpR3′-976 (see above). The resulting PCR fragments were combined in a self-priming PCR to construct the dmpR-B24 sensor domain.

The F17 sensor domain was constructed in a similar fashion. The wild-type 5′ region of the wild-type dmpR sensor domain was amplified with primers dmpR5′-75 (see above) and dmpR3′-280 (5′-GCATGTTCCTCGCTGGGC-3′). The overlapping 3′ sensor domain fragment carrying DNA corresponding to the F17 D116V mutation was amplified by using primers dmpR5′-280 (5′-GCCCAGCGAGGAACATGC-3′) and dmpR3′-976 (see above). The template for this step was a double mutant carrying the D116V mutation in conjunction with an upstream mutation. Again, the 5′ and 3′ fragments were combined in a self-priming PCR to create the dmpR-F17 sensor domain.

Test strain construction and screen for sensor domain mutations.

The pAW51 plasmid, carrying the Pdmp-lacZ fusion, was linearized by restriction with ScaI and then used to transform TE2680 with selection for kanamycin resistance. Transformants were screened for loss of ampicillin and chloramphenicol resistance, a condition indicating integration of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion into the TE2680 chromosome at the trp operon (8, 32). The general transducing phage P1kc (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) was used to transfer the fusion to the chromosome of E. coli MC4100. The transduction created strain AW101.

DmpR mutant selection.

AW101 was used as a test strain to identify and characterize changes in the chemical detection capacity of DmpR derivatives after sensor domain mutagenesis. The pAW50 plasmid derivatives were introduced into AW101 by electroporation. Transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) plates containing 10.5 μg of tetracycline per ml. Transformants were then replica plated onto M9 minimal medium (15) plates containing 0.2% glucose, 30 μg of tryptophan per ml, 1 μg of thiamine per ml, 10.5 μg of tetracycline per ml, 0.003% 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal), and either no inducer or a phenol derivative at 50 nM. Cells that formed bluer colonies than cells containing wild-type DmpR were subjected to further analysis with liquid β-galactosidase assays.

Phenolic molecules tested.

DmpR mutants were tested for their ability to detect the 11 phenols listed as priority pollutants by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, i.e., phenol, 2-chlorophenol, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol, pentachlorophenol, 4-chloro-3-methylphenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, 2-nitrophenol, 4-nitrophenol, 2,4-dinitrophenol, and 2-methyl-4,6-dinitrophenol. Phenols were prepared as 25 mM stocks in ethyl alcohol for addition to solid or liquid media and were tested at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 75 μM in different experiments.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Overnight cultures of AW101 carrying pAW50 derivatives were diluted 1,000-fold into Luria-Bertani broth containing 10.5 μg of tetracycline per ml. When cells reached an A595 of between 0.80 and 1.0 as measured on a Lambda Bio UV-visible spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Corp. Analytical Instruments, Norwalk, Conn.), 800-μl samples were pelleted by centrifugation and immediately suspended in 800 μl of spent Luria-Bertani broth (medium from an overnight culture sterilized through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter) containing the appropriate phenol derivative. The use of spent Luria-Bertani medium prevented the high level of phenol-independent activity that was seen when cells were allowed to grow into stationary phase in regular Luria-Bertani medium or glucose-supplemented minimal medium. In E. coli, the dmpR gene is expressed or stabilized as cells enter stationary phase (33). We assume that the stationary-phase expression of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion in the absence of a phenolic inducer resulted from the multicopy nature of pAW50 and its derivatives carrying the dmpR mutants.

In most experiments, exposure to phenolic molecules was for 2 h with shaking at 37°C. For assays involving more dilute phenolic inducers, the reporter gene signal was amplified by increasing phenol exposure to 4 h. Cell samples were then pelleted by centrifugation and frozen at −70°C for β-galactosidase assays the following day.

Liquid β-galactosidase assays were performed by using a modification of Miller's assay (15). Cell sample pellets were thawed and suspended in 800 μl of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4 · H2O, 40 mM NaH2PO4 · H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O). The A595 of 100 μl of each cell suspension was determined in a microtiter plate by using an automated microplate reader (BIO-TEK Instruments, Inc., Winooski, Vt.). Following the addition of 15 μl of 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 20 μl of HCCl3, the remaining cell suspension was vortexed for 30 s to lyse cells, and 100 μl of each lysed sample was placed in the well of a microtiter plate. Each assay reaction was initiated with the addition of 50 μl of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (2.5 mg/ml). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 26°C, and reactions were stopped with the addition of 50 μl of 1 M Na2CO3. Color development for each reaction was detected by measurement at A415 on the microplate reader. Arbitrary units for graphing purposes were calculated as (1,000 × A415)/(time)(A595), where time is the reaction time in minutes.

DNA sequencing.

Mutations in the dmpR sensor domain were identified through DNA sequencing with the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing system (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). Products from sequencing reactions were separated by electrophoresis in 4% polyacrylamide gels on an ABI 373A Stretch DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Analysis of mutant sensor domain DNA and amino acid sequences was conducted by using LASERGENE software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.).

RESULTS

DmpR mutants increase detection of phenolic molecules in β-galactosidase assays.

Our mutagenic procedure and selection process (Fig. 1) resulted in replacement of DNA corresponding to the first 176 amino acids of DmpR (about 85% of the sensor domain). Three repetitions of these methods led to the identification of more than 20 DmpR derivatives that increased transcription of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion (compared to wild-type DmpR) in response to phenol and substituted phenols on plate assays. Sequence analysis demonstrated that the number of mutations per dmpR derivative ranged from one to six and averaged between two and three (data not shown).

Mutations that change the interaction of DmpR with phenol and substituted phenols.

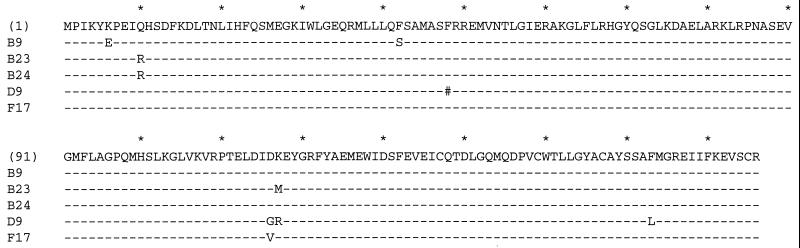

Changes in the sensor domain-coding sequences of the DmpR mutants that increased transcription of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion in response to phenol or substituted phenols are represented in Fig. 2. Three DmpR mutants contained a mutation at codon 116 and/or codon 117. B23 contained a lysine-to-methionine change at codon 117, F17 contained an aspartate-to-valine change at codon 116, and D9 was mutated at both positions (D116G and K117R). B23 and D9 contained additional mutations, making it difficult to assess the importance of changes at codon 117. An enhanced response to phenolic molecules mediated by F17 (D116V) suggested that the aspartate at position 116 acts to restrict the effector range of wild-type DmpR. The Q10R mutation of B24 strongly enhanced the response to phenol and disubstituted phenols. The effector response profile of B24 is similar to that of mutant B23, suggesting that the Q10R mutation contributes to increased detection of phenols by B23.

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequences of DmpR mutant sensor domains. The wild-type sequence is shown in the first line. Mutations are entered at corresponding positions for the mutants. The # symbol indicates a nucleotide mutation that is not expected to alter the amino acid code (e.g., TTT→TTC at codon 48 in D9).

Detection of phenolic molecules by DmpR mutants.

The DmpR mutants described in this report were characterized in detail with liquid β-galactosidase assays. β-Galactosidase activity is proportional to transcription of the Pdmp-lacZ reporter fusion and is, therefore, a measure of a particular DmpR mutant's ability to detect phenol or a specific substituted phenol. The comparative performance of mutant proteins was initially tested to detect priority pollutant phenols listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in concentrations that ranged from 10 to 100 μM. The concentrations of phenolic effectors for the assays represented in Tables 2 and 3 were chosen based on their ability to elicit a response from the majority of DmpR mutants that was at least fourfold higher than that achieved in the absence of a phenolic inducer. Thus, phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and 2,4-dichlorophenol were used at a concentration of 25 μM (Table 2). The less efficient inducers 4-chloro-3-methylphenol, 2,4-dimethylphenol, 2-nitrophenol, and 4-nitrophenol (Table 3) were used at 75 μM.

TABLE 2.

Responses of DmpR mutants to 25 μM phenol- or chloro-substituted phenol

| DmpR mutant | Effector phenol | Avg mutant activitya (SD) | Avg wild-type activityb (SD) | Ratio of mutant activity to wild-type activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B9 | None | 12 (0.2) | 13 (0.2) | 1 |

| Phenol | 847 (26.6) | 20 (2.1) | 42 | |

| 2-Chlorophenol | 895 (99) | 239 (40.6) | 4 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 79 (13.5) | 13 (1.9) | 6 | |

| B23 | None | 8 (0.4) | 8 (0.1) | 1 |

| Phenol | 1,122 (142) | 20 (2.1) | 56 | |

| 2-Chlorophenol | 2,889 (126) | 644 (68.4) | 4 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 1,368 (87) | 29 (2.7) | 47 | |

| B24 | None | 19 (0.9) | 20 (2.1) | 1 |

| Phenol | 1,455 (170) | 33 (1.9) | 44 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 431 (41) | 18 (0.5) | 24 | |

| D9 | None | 11 (0.6) | 13 (0.2) | 1 |

| Phenol | 474 (25.1) | 24 (1.0) | 20 | |

| 2-Chlorophenol | 1,030 (109) | 239 (40.6) | 4 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 68 (4.0) | 13 (1.9) | 5 | |

| F17 | None | 17 (0.7) | 20 (2.1) | 1 |

| Phenol | 1,079 (197) | 33 (1.9) | 33 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 207 (31) | 18 (0.5) | 12 |

β-Galactosidase activity [(1,000)(A415)]/[(A595)(minute)]. Results are averages from three independent cultures.

Activity for cells carrying wild-type DmpR assayed on the same day under identical conditions.

TABLE 3.

Responses of DmpR mutants to 75 μM methyl- or nitro-substituted phenols

| DmpR mutant | Effector phenol | Avg mutant activitya (SD) | Avg wild-type activityb (SD) | Ratio of mutant activity to wild-type activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B9 | None | 22 (1.8) | 21 (3.4) | 1 |

| 4-Chloro-3-methylphenol | 86 (2.2) | 27 (0.8) | 3 | |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenol | 351 (12.2) | 29 (4.2) | 12 | |

| 2-Nitrophenol | 369 (82.5) | 53 (9.3) | 7 | |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 110 (16.3) | 26 (2.0) | 4 | |

| B23 | None | 21 (5.1) | 21 (3.4) | 1 |

| 4-Chloro-3-methylphenol | 182 (62.1) | 27 (0.8) | 7 | |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenol | 573 (43.5) | 29 (4.2) | 19 | |

| 2-Nitrophenol | 529 (82.2) | 53 (9.3) | 10 | |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 169 (4.9) | 26 (2.0) | 7 | |

| B24 | None | 19 (0.9) | 18 (2.1) | 1 |

| 4-Chloro-3-methylphenol | 445 (40) | 20 (2.6) | 22 | |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenol | 480 (13) | 23 (1.6) | 21 | |

| D9 | None | 21 (7.6) | 21 (3.4) | 1 |

| 4-Chloro-3-methylphenol | 140 (25.9) | 27 (0.8) | 5 | |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenol | 404 (19.2) | 29 (4.2) | 14 | |

| 2-Nitrophenol | 179 (20.2) | 53 (9.3) | 3 | |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 123 (10.5) | 26 (0.2) | 5 | |

| F17 | None | 17 (0.7) | 19 (2.1) | 1 |

| 4-Chloro-3-methylphenol | 89 (11) | 20 (2.6) | 4 | |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenol | 169 (31) | 23 (1.6) | 7 |

β-Galactosidase activity [(1,000)(A415)]/[(A595)(minute)]. Results are averages from three independent cultures.

Activity for cells containing the wild-type DmpR protein and assayed on the same day under identical conditions.

Phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and 2-nitrophenol are inducers of wild-type DmpR, although the effect of phenol and 2-nitrophenol is weak (less than threefold induction) at the concentrations used in our study. Both of these chemicals elicited a distinct response when transcription was mediated by DmpR mutants (Tables 2 and 3). Induction levels in response to phenol ranged from 43 times (with D9) to 140 times (with B23) the uninduced response. Exposure to 75 μM 2-nitrophenol increased activity 17-fold for B9, 25-fold for B23, and 8-fold for D9. In addition, B9, B23, and D9 consistently produced about fourfold higher levels of β-galactosidase activity following exposure to 2-chlorophenol than levels determined in side-by-side tests with the wild-type protein (Table 2).

The DmpR mutants also responded well to phenols that are poor effectors of wild-type DmpR. Disubstituted and para-substituted phenols are poor effectors of the wild-type protein, even at concentrations as high as 2 mM (29). We tested the ability of the DmpR mutants to induce transcription of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion following exposure to 2,4-dichlorophenol (Table 2) and 2,4-dimethylphenol, 4-chloro-3-methylphenol, and 4-nitrophenol (Table 3). Induction levels following exposure to disubstituted phenols ranged from 4-fold (for B9 in response to 4-chloro-3-methylphenol) to 170-fold (for B23 in response to 2,4-dichlorophenol). The response to 4-nitrophenol was less impressive and ranged from fivefold induction for B9 to eightfold induction for B23.

Priority pollutant phenols that are not detected by DmpR mutants.

Priority pollutant phenols that were not detected by any of the DmpR mutants included the larger and more toxic molecules, i.e., pentachlorophenol, 2,4,6-trichlorophenol, and 2-methyl-4,6-dinitrophenol. The pKas of pentachlorophenol (4.9) and 2-methyl-4,6-dinitrophenol (4.3) suggest that these molecules may not have been able to efficiently enter the cell due to deprotonation of their hydroxyl groups at the neutral pH of the induction medium. In addition, exposure of the test strain to 25 μM pentachlorophenol or 2,4,6-trichlorophenol resulted in visible cell lysis. The response to 2,4-dinitrophenol was unaccountably variable.

Limits of phenol detection by DmpR mutant B24.

The usefulness of a DmpR variant as the phenol-detecting component of a bacterial biosensor will be determined in part by the lowest concentration of chemical that can elicit a transcriptional response. As illustrated in Tables 2 and 3, the B24 mutant protein was one of the more sensitive DmpR derivatives. We sought to estimate the lowest concentrations of phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and 2,4-dichlorophenol that could be detected by B24. Reliable detection was defined as β-galactosidase activity that reached a level at least fourfold higher than that attained in the absence of a phenolic inducer. In order to amplify the β-galactosidase signal, the chemical exposure time was increased to 4 h.

Table 4 compares activity mediated by B24 with that dependent on the wild-type protein. The lower limit of phenol detection by B24 was found to be close to 0.5 mM (fourfold induction). Phenol detection by the wild-type protein requires a concentration of between 50 and 100 mM (data not shown). The B24 mutant could detect 2-chlorophenol at a concentration of between 0.1 and 0.5 mM (24-fold induction). Wild-type protein could detect 2-chlorophenol at 2.5 mM (eightfold induction). B24 detected 2,4-dichlorophenol at 5 mM (fivefold induction). As shown previously, 2,4-dichlorophenol is not an effector of wild-type DmpR (29).

TABLE 4.

Limits of B24-mediated detection of phenolic molecules

| Effector phenol | Conc (μM) | Avg B24-mediated activitya (SD) | Ratio of induced to noninduced activity (B24) | Avg wild-type DmpR-mediated activitya (SD) | Ratio of induced to noninduced activity (DmpR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 16 (20.6) | 1 | 16 (2.9) | 1 | |

| Phenol | 0.1 | 40 (3.2) | 3 | 20 (3.0) | 1 |

| 0.5 | 67 (3.3) | 4 | 22 (2.5) | 1 | |

| 2.5 | 261 (10.9) | 16 | 27 (7.6) | 2 | |

| 2-Chlorophenol | 0.1 | 50 (3.0) | 3 | 21 (3.3) | 1 |

| 0.5 | 381 (87) | 24 | 28 (5.1) | 2 | |

| 2.5 | 3,087 (61) | 193 | 134 (11.0) | 8 | |

| 2,4-Dichlorophenol | 1 | 37 (1.4) | 2 | 21 (1.1) | 1 |

| 5 | 72 (5.4) | 5 | 21 (1.1) | 1 | |

| 25 | 683 (126) | 44 | 25 (1.8) | 2 |

β-Galactosidase activity [(1,000)(A415)]/[(A595)(minute)]. Results are averages from three independent cultures.

DmpR derivatives do not respond to XylR effectors.

The sensor domain of XylR is 64% identical to DmpR at the amino acid level (28). The increased range of phenol effectors for the DmpR derivatives led us to ask if they had acquired the ability to respond to effectors of XylR. Cells carrying either wild-type DmpR or mutant B9, B23, D9, or F17 were exposed to 75 mM toluene, 2-nitrotoluene, 2-chlorotoluene, 4-chlorotoluene, or o-xylene in spent Luria-Bertani medium for 2 h. These chemicals did not induce transcription of the Pdmp-lacZ fusion (data not shown). Thus, like the wild-type protein, the DmpR mutants were unable to respond to chemical effectors of XylR.

DISCUSSION

Whole-cell bacterial biosensors have the potential to provide inexpensive, easy-to-use methods of detecting industrial pollution. Biosensors based on the genetic systems of bacteria that metabolize pollutants have been described (1, 10, 11, 20, 40, 41). These biosensors have used the XylR or NahR proteins to activate expression of reporter genes. The chemical detection capabilities of bacterially based biosensors have been limited to chemicals that are natural effectors of a wild-type regulator protein. Through the generation and characterization of mutant regulator proteins, we demonstrate that the chemical detection ability of bacterial biosensors can be enhanced to increase the sensitivity to chemical effectors of the natural genetic system. The range of effector chemicals that can be detected by the bacterial system can also be expanded to include chemicals that are not detected by the wild-type proteins.

In this report we describe the response of DmpR derivatives to phenols listed as priority pollutants by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. DmpR mutants B9, B23, B24, and F17 increased sensitivity to effectors of the wild-type protein and also responded to phenolic molecules that are not effectors of the natural system. Engineered proteins of this type could form the basis for biosensors with improved detection of organic pollutants.

The mechanism by which DmpR binds its chemical effectors and changes conformation to become capable of transcription activation is not well understood. However, there is good evidence that the capacity of DmpR to activate transcription is repressed through an interaction between the sensor and polymerase-activating domains of DmpR (18, 19, 30). This repression can be reversed through a successful interaction between the sensor domain and an effector chemical or through engineering the removal of the sensor domain (30). Similar experiments with XylR give analogous results (22, 23).

Our DmpR mutants failed to respond to XylR effectors (data not shown). The benzene derivatives that induce transcription activation mediated by XylR are similar in size and shape to the phenolic effectors studied, but they lack a hydroxyl group. Our results suggest that a hydroxyl group remains a requirement for achieving the transcription activator form of the DmpR mutants. It is clear, however, that DmpR mutants B9, B23, B24, D9, and F17 can accommodate an increased number of substituents on their phenolic effectors compared with the wild-type protein.

Sensor domain mutations that increase the range of effector chemicals have been identified by others in an attempt to understand the biochemical properties of DmpR and XylR. DmpR mutations E135K and R184W each induce transcription of a reporter gene following exposure to phenolic molecules that are not effectors of wild-type DmpR (21, 30). Like the DmpR derivatives described in this paper, these mutant proteins retain the capacity to respond to chemical effectors of wild-type DmpR. An XylR E172K mutation allows a response to 3-nitrotoluene, a chemical which inhibits transcription activation by the wild-type protein (6, 26). It has been suggested that mutations that alter the effector profile of DmpR or XylR exert their effect either through an improvement in the effector-protein interaction or by changing the three-dimensional structure of the protein in ways that enhance other necessary functions of the protein, for example, polymerase activation (6, 21, 26).

The fact that the DmpR derivatives can still detect effectors of wild-type DmpR (phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and 2-nitrophenol) suggests that a key aspect of the interaction between the mutant sensor domains and the chemical effectors remains substantially unaltered. Rather, mutations that distort the secondary structure of DmpR may allow larger, differently substituted molecules access to a crucial site on the sensor domain. These molecules could then act as effectors, provided that they have the appropriate chemical attribute (perhaps determined by the phenol hydroxyl group).

For DmpR and similarly organized proteins, knowledge of the protein's three-dimensional structure and any specific contacts it makes with effector chemicals would greatly enhance efforts to directly engineer proteins that can function as detectors for a variety of organic molecules. So far, the poor solubility of DmpR and related proteins has impeded efforts to understand the structure of such proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Virginia Shingler for providing pVI401. Our thanks go to Geoff Waldo and Thomas Terwilliger for interesting discussions on DmpR and to John Dunbar for helpful comments on the manuscript. In addition, we thank Alicia Alexander and Rachael Morgan for assistance with experiments.

This work was supported by Los Alamos National Laboratory LDRD grant W-7405-ENG-36.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa M, Nishiguchi K, Imamura M, Kobatake E, Haruyama T, Ikariyama Y. Integrated molecular systems for biosensors. Sensors Actuators B. 1995;24:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne A, Olsen R. Cascade regulation of the toluene-3-monoxygenase operon (tbuA1UBVA2C) of Burkholderia pickettii PKO1: role of the tbuA1 promoter (PtbuA1) in the expression of its cognate activator, TbuT. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6327–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6327-6337.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadwell R, Joyce G. Mutagenic PCR. In: Dieffenbach C W, Dveksler G S, editors. PCR primer, a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadaban M. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage, lambda and Mu. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:541–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado A, Ramos J. Genetic evidence for activation of the positive transcriptional regulator XylR, a member of the NtrC family of regulators, by effector binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8059–8062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dower W, Miller J, Ragsdale C. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliot T. A method for constructing single-copy lac fusions in Salmonella typhimurium and its application to the hemA-prfA operon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:245–253. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.245-253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Register. National recommended water quality criteria. Fed Regist. 1998;63:67547–67558. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heitzer A, Webb O, Thonnard J, Sayler G. Specific and quantitative assessment of napthalene and salicylate bioavailability by using a bioluminescent catabolic reporter bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1839–1845. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1839-1846.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikariyama Y, Nishiguchi S, Koyama T, Kobatake E, Aizawa M. Fiber-optic based biomonitoring of benzene derivatives by recombinant E. coli bearing luciferase gene-fused TOL-plasmid immobilized on the fiber-optic end. Anal Chem. 1997;69:2600–2605. doi: 10.1021/ac961311o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Innes M, Gelfand D, Sninsky J, White T. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S-Y, Rasheed S. A simple procedure for maximum yield of high-quality plasmid DNA. BioTechniques. 1990;9:676–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez D, Pocurull E, Marce R, Borrull F, Calull M. Separation of eleven priority phenols by capillary zone electrophoresis with ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr A. 1996;734:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller C, Petruschka L, Cuypers H, Burchhardt G, Herrmann H. Carbon catabolite repression of phenol degradation in Pseudomonas putida is mediated by the inhibition of the activator protein PhlR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2030–2036. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2030-2036.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng L, Poh C, Shingler V. Aromatic effector activation of the NtrC-like transcriptional regulator PhhR limits the catabolic potential of the (methyl)phenol degradative pathway it controls. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1485–1490. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1485-1490.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng L, O'Neil E, Shingler V. Genetic evidence for interdomain regulation of the phenol-responsive ς54-dependent activator DmpR. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17281–17286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neil E, Ng L, Sze C, Shingler V. Aromatic ligand-binding and intramolecular signaling of the phenol-responsive sigma(54)-dependent regulator DmpR. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:131–141. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer G, McFadzean R, Kilham K, Sinclair A, Paton G. Use of lux-based biosensors for rapid diagnosis of pollutants in arable soils. Chemosphere. 1998;36:2683–2696. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavel H, Forsman M, Shingler V. An aromatic effector specificity mutant of the transcriptional regulator DmpR overcomes the growth constraints of Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 on para-substituted methylphenols. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7550–7557. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7550-7557.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. Identification of the repressor subdomain within the signal reception module of the prokaryotic enhancer-binding protein XylR of Pseudomonas putida. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7899–7902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Martín J, de Lorenzo V. In vitro activities of an N-terminal truncated form of XylR, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:575–587. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos J, Marqués S, Timmis K. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas TOL plasmid catabolic operons is achieved through an interplay of host factors and plasmid-encoded regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:341–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen L, Turner R, Barkay T. Cell density dependent sensitivity of a mer-lux bioassay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3291–3293. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3291-3293.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salto R, Delgado A, Michan C, Marques S, Ramos J. Modulation of the function of the signal receptor domain of XylR, a member of prokaryotic enhancer-like positive regulators. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:600–604. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.600-604.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shingler V, Bartilson M, Moore T. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the positive regulator (DmpR) of the phenol catabolic pathway encoded by pVI150 and identification of DmpR as a member of the NtrC family of transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1596–1604. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1596-1604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shingler V, Moore T. Sensing of aromatic compounds by the DmpR transcriptional activator of phenol-catabolizing Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1555–1560. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1555-1560.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shingler V, Pavel H. Direct regulation of the ATPase activity of the transcriptional activator DmpR by arromatic compounds. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirmer F, Ehrt S, Hillen W. Expression, inducer spectrum, domain structure, and function of MopR, the regulator of phenol degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus NCIB82250. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1329–1336. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1329-1336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons R W, Houman F, Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sze C C, Moore T, Shingler V. Growth phase-dependent transcription of the ς54-dependent Po promoter controlling the Pseudomonas-derived (methyl)phenol dmp operon of pVI150. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3727–3735. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3727-3735.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for phenol, 440/5-80-066. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for 2-chlorophenol, 440/5-80-034. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for chlorinated phenols, 440/5-80-032. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for 2,4-dichlorophenol, 440/5-80-042. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. p. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for 2,4-dimethylphenol, 440/5-80-044. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. p. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Ambient water quality criteria for nitrophenols, 440/5-80-063. U.S. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webb Q, Bienkowski P, Matrubutham U, Evans F, Heitzer A, Sayler G. Kinetics and response of a Pseudomonas fluorescens HK44 biosensor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1997;54:491–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970605)54:5<491::AID-BIT8>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willardson B, Wilkins J, Rand T, Schupp J, Hill K, Keim P, Jackson P. Development and testing of a bacterial biosensor for toluene-based environmental contaminants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1006–1012. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.1006-1012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]