Abstract

A simple method for whole-cell hybridization using fluorescently labeled rRNA-targeted peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes was developed for use in marine cyanobacterial picoplankton. In contrast to established protocols, this method is capable of detecting rRNA in Prochlorococcus, the most abundant unicellular marine cyanobacterium. Because the method avoids the use of alcohol fixation, the chlorophyll content of Prochlorococcus cells is preserved, facilitating the identification of these cells in natural samples. PNA probe-conferred fluorescence was measured flow cytometrically and was always significantly higher than that of the negative control probe, with positive/negative ratio varying between 4 and 10, depending on strain and culture growth conditions. Prochlorococcus cells from open ocean samples were detectable with this method. RNase treatment reduced probe-conferred fluorescence to background levels, demonstrating that this signal was in fact related to the presence of rRNA. In another marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus, in which both PNA and oligonucleotide probes can be used in whole-cell hybridizations, the magnitude of fluorescence from the former was fivefold higher than that from the latter, although the positive/negative ratio was comparable for both probes. In Synechococcus cells growing at a range of growth rates (and thus having different rRNA concentrations per cell), the PNA- and oligonucleotide-derived signals were highly correlated (r = 0.99). The chemical nature of PNA, the sensitivity of PNA-RNA binding to single-base-pair mismatches, and the preservation of cellular integrity by this method suggest that it may be useful for phylogenetic probing of whole cells in the natural environment.

Prochlorococcus spp. and Synechococcus spp. together are the most abundant marine photosynthetic microorganisms. These unicellular cyanobacteria account for a large part of the photosynthetic biomass and total primary production in open-ocean environments (3, 7, 8, 31, 39). However, their population dynamics are complex and poorly understood. Natural populations of both Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus have been observed to be composed of numerous genetically and physiologically distinct strains or “ecotypes” (21–23, 25, 35, 38, 40). Molecular techniques such as nucleic acid sequencing, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and rRNA-targeted DNA probing (i.e., oligonucleotide probing) have lent considerable insight into the natural distribution of marine cyanobacterial ecotypes (11, 15, 27, 34, 36). To date, however, these techniques have been applied solely to extracted and amplified nucleic acids; as such they provide only indirect information about these marine populations. Furthermore, they may be subject to PCR bias (26, 33). In order to gain a better understanding of the dynamics of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in the natural environment it is important to be able to perform molecular analyses on an individual-cell basis, so that direct, simultaneous measurements of abundance, biomass, and activity of ecotypes can be made.

One promising approach for the analysis of individual cells is whole-cell hybridization with fluorescently labeled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes (herein referred to as DNA probes), combined with flow cytometry (2). Flow cytometry allows rapid analysis of cells, which is particularly important for gathering statistically robust data for studies of the natural environment, where cell concentrations can be quite low. Whole-cell hybridization with rRNA-targeted DNA probes has been successfully combined with flow cytometry to quantify the rRNA of individual cells in cultures of marine Synechococcus (5). This study demonstrated a relationship between rRNA content and growth rate in a coastal Synechococcus strain, suggesting that an extension of the approach to natural populations could be used not only to identify cells but also to estimate their in situ growth rates. Another recent study described the application of horseradish peroxidase-labeled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for whole-cell hybridization (visualized with epifluorescence microscopy) in a broad range of cyanobacterial strains (28).

Several factors have hampered the application of whole-cell DNA (oligonucleotide) hybridization to picoplankton populations in oceanic samples and to Prochlorococcus in general. Protocols usually require a cell fixation step and permeabilization step (sometimes in conjunction with fixation) using alcohol and/or detergents, followed by hybridization using a labeled 16S rRNA-targeted probe (1, 5, 9, 28, 41). The permeabilization step can damage delicate cells and degrade important cellular characteristics. Especially critical in this regard is the chlorophyll-based discrimination of Prochlorococcus populations from similarly sized marine heterotrophic bacteria. To date no published protocol for whole-cell hybridization preserves this chlorophyll signal. Once the probe has entered the cell, target site accessibility is a concern particularly for development of phylogenetic probes for which the target site is dictated by the location of a mismatch. It has been shown that the success of DNA probing in Escherichia coli is subject to the target site location, due to the lower accessibility of some regions of the 16S rRNA (12). Finally, in natural systems, where cells typically exist at much lower concentrations than in laboratory cultures, the number of spins and washes becomes a critical issue due to the inevitable loss of cells at each step.

In order to facilitate future work on the identification and analysis of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in natural samples, we have developed a protocol for whole-cell hybridization of fluorescently labeled rRNA targeted probes that minimizes the above-mentioned problems. The protocol utilizes peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes (rather than DNA probes) in conjunction with flow cytometry, making it well suited for the analysis of multiple parameters for specific populations within mixed microbial communities.

PNA is an achiral synthetic nucleic acid in which the sugar-phosphate backbone of DNA has been replaced with an uncharged structurally homomorphous pseudopeptide backbone (10, 24, 29). A PNA-RNA duplex exhibits higher thermal stability than the corresponding DNA-RNA duplex, in part due to the lack of electrostatic repulsion between the target site and the PNA strand (10). PNA probes have higher specificity than analogous DNA probes, because a single-base-pair mismatch is more thermally destabilizing in the former than in the latter (10). Due to the unique chemical nature of PNA these molecules can be used over a broad range of conditions and have allowed gene expression and point mutation research that could not be performed with DNA probes (13). In addition, PNA probes appear to be less hampered by target site accessibility than are DNA probes (30; J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, personal communication). For example, one E. coli 16S rRNA target site shown to yield “only background fluorescence” when probed with fluorescently labeled DNA probes (12) yielded a very good signal with PNA probes (J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, personal communication).

This paper describes and characterizes a PNA-based protocol for in situ rRNA probing of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus cells, including Prochlorococcus cells from natural samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culturing.

Prochlorococcus isolates SS120 and MED4 were grown on modified K/12 media (22) as described below. Synechococcus strains WH8101 and WH8007 were obtained from J. Waterbury (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) and the Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Marine Phytoplankton, respectively, and grown on SN media (38). Twenty-milliliter cultures of Prochlorococcus were maintained at 21°C under Cool-White fluorescent lamps (2.5 × 1015 quanta cm−2 s−1) on a 14-h/10-h light/dark cycle. Synechococcus strains were maintained at 25°C under constant light from cool-white fluorescent lamps (7.8 × 1015 quanta cm−2 s−1). Growth of both organisms was monitored by in vivo fluorescence, and cells were diluted into fresh media prior to the onset of stationary phase to ensure constant exponential growth. Cultures were maintained at a given light level and growth rate for the equivalent of at least 10 generations prior to sampling.

Sampling and fixation.

Two preservation methods were routinely employed. Synechococcus cultures were fixed in methanol and stored at −20°C, as described previously (6). Prochlorococcus cultures were fixed in paraformaldehyde (1% final concentration) and stored cryogenically (37). Other preservation protocols were explored in preliminary experiments and found to be incompatible with whole-cell probing in these cells. Protocols using methanol or ethanol, for example, were found to destroy the chlorophyll signal necessary for the identification of Prochlorococcus cells, and glutaraldehyde fixation (0.1% final concentration) resulted in higher fluorescence background and lower signal strength in Prochlorococcus, compared with paraformaldehyde fixation. Environmental samples were collected from a depth of 25 m in 10-liter Niskin water sampling bottles from an oligotrophic site in the Pacific Ocean bordering the California Current (30°51′N, 122°92′W) and preserved in paraformaldehyde as described above.

rRNA-targeted probes.

Two PNA probes, pEUB339, a positive probe designed to bind to all strains used in this study, and pNEG1198, a negative probe meant to serve as a control to account for nonspecific binding and background fluorescence, were synthesized by PerSeptive Biosystems (Framingham, Mass.) (Table 1). The sequence for pEUB339 was based on the widely used probe EUB338 (Table 1), which has previously been classified as a 16S rRNA-targeted eubacterial probe (1, 14). It should be noted however, that neither EUB338 nor pEUB339 complements all picoplanktonic cyanobacteria: among known sequences for Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus strains, both probes have mismatches with two strains (WH8103 and WH7805) (35). Note also that because pEUB339 is significantly shorter than EUB338, it complements some eukaryotes (20). Likewise, because pNEG1198 is shorter than the eukaryote-specific probe EUK1195, upon which it is based (1, 14), it complements some prokaryotes. It does not, however, complement any known Prochlorococcus or Synechococcus sequences. pNEG1198 was chosen as the negative control rather than NON338 because the latter is a purine-rich sequence and consequently more difficult to synthesize with PNA. PNA probes were synthesized with a hydrophilic linker binding the 5′ terminus and a fluorescein label. PNA probes were dissolved in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and frozen at −20°C in small aliquots for later use. For initial probing attempts, two positive DNA probes, EUB338 and UNIV1392, and one negative DNA probe, NON338 (1, 14), were synthesized with 5′-terminal amino groups and labeled with BODIPY FL-X (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) (Table 1). Fluorescein-labeled DNA probes yielded a lower positive-to-negative signal ratio than BODIPY-labeled DNA probes; therefore, BODIPY-labeled DNA probes were used exclusively.

TABLE 1.

Designations and targets of probes

| Probe | Sequence (5′→3′) | Targeta | Binding expected |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNA | |||

| pEUB339 | CTGCCTCCCGT | 16S, 339–348 | Yes |

| pNEG1198 | CATCACAGACC | 16S, 1198–1209 | No |

| DNA | |||

| EUB338 | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | 16S, 338–355 | Yes |

| NON338 | ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC | 16S | No |

| UNIV1392 | ACGGGCGGTGTGT(G/A)C | 16S, 1392–1406 | Yes |

16S rRNA E. coli numbering.

Whole-cell hybridizations.

Probe fluorescence was optimized with respect to hybridization and wash temperatures, hybridization time, and probe concentration (see Results and Discussion). Because PNAs can be used in a broad range of salt concentrations and are chemically stable over a wide pH range (13; PerSeptive Biosystems product information), we chose to use the same buffer conditions as in previous DNA probe work (5). The results of these hybridization experiments led to the following standard hybridization protocol for Prochlorococcus. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were thawed at room temperature, and 600-μl aliquots were centrifuged (16,000 × g, 10 min, 12°C). All but 10 to 15 μl of the supernatant was aspirated, and cells were then resuspended in the remaining 10 to 15 μl. Hybridization conditions were as follows: 50 μl of prewarmed hybridization buffer (900 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.2]) was combined with 2.5 μl of PNA probe solution (2.1 μg ml−1, final concentration). Five-microliter aliquots of the cell suspension were added to the hybridization/probe solution and incubated at 34°C for 9 to 14 h. At the end of the hybridization period, 500 μl of hybridization buffer was added and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were centrifuged (16,000 × g, 14 min, room temperature), resuspended in 400 μl of filter (0.2-μm pore size)-sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and stored on ice until analysis on the flow cytometer. For probing samples collected from the field, 1,000 μl of preserved seawater (1% paraformaldehyde) was pelleted by centrifugation (18,500 × g, 14 min, 14°C), approximately 990 μl was aspirated, and the pellet was resuspended in the remaining supernatant. Four-microliter aliquots of the cell suspension were hybridized with pEUB339 or pNEG1198 probes (4.3 μg ml−1, final concentration) as described above with an incubation time of 10 h.

For Synechococcus, DNA probe hybridizations were performed according to the methods of Binder and Liu (5). Synechococcus cells for PNA probing were also preserved and prepared according to the methods of Binder and Liu (5), and then the PNA hybridization was performed as outlined above. These two hybridization protocols are essentially the same except for the hybridization and wash temperatures. For DNA probing the hybridization was conducted at 45°C and the wash at 48°C, whereas for PNA probing these temperatures were 34 and 37°C, respectively.

RNase treatment.

Because Prochlorococcus cells have not previously been probed in situ, PNA probe fluorescence was compared in RNase-treated cells and untreated cells to establish that fluorescence was due to probe bound to RNA and not some other cellular constituent. Cryogenic samples were thawed at room temperature for 20 min. Aliquots of 600 μl were incubated with RNase A (0.5 mg ml−1; Sigma R6513) and RNase I (83 U ml−1; Boehringer 1732684) for 1 h at 37°C. Control samples received Milli-Q water rather than RNase but otherwise were treated identically. All samples were centrifuged (16,000 × g, 14 min, 26°C) and resuspended in 15 μl of supernatant. Cell suspensions were diluted in filtered seawater as necessary to achieve comparable cell concentrations and hybridized for 14 h as described above.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Probed cells were analyzed on two different flow cytometers. An EPICS 753 flow cytometer (Coulter Corp.) equipped with a 5-W argon ion laser (run at 800 mW) and modified for high sensitivity as described previously (4) was used for the initial experiments on hybridization conditions and for the RNase experiment. Emission was collected through a 525-nm band-pass filter (35-nm bandwidth; Omega Corp.) for probe fluorescence and a 680-nm band-pass filter (40-nm bandwidth) for chlorophyll and/or phycocyanin fluorescence. An EPICS XL (Coulter Corp.) equipped with a 15-mW argon ion laser was used for all Synechococcus PNA work and final experiments on conditions for Prochlorococcus hybridizations. Emission filters on this flow cytometer were a 525-nm band-pass for probe fluorescence (30-nm bandwidth) and a 675-nm band-pass for red (chlorophyll) fluorescence (30-nm bandwidth). Both flow cytometers excited samples at a wavelength of 488 nm. Fluorescence measurements are expressed on a relative scale and normalized to standard fluorescent latex beads (0.474-μm diameter; Polysciences, Inc.), which were added to each sample. Data were collected as listmodes and analyzed with Cyclops II (Cytomation, Inc.), WinList (Verity Software House, Inc.), and/or WIN-MDI (Joseph Trotter, The Scripps Research Institute) software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DNA probes.

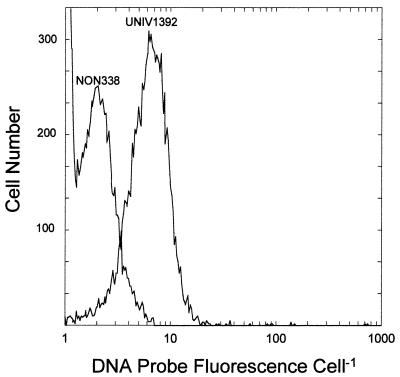

An established protocol for whole-cell hybridization of fluorescently labeled 16S rRNA-targeted DNA probes in Synechococcus (5), which utilizes the positive probe EUB338 and negative probe NON338 (Table 1), provided good positive/negative probe signal ratios in Synechococcus as expected. However, attempts to accomplish the same in Prochlorococcus, using several different protocols and variations thereof (2, 5, 18, 41) and employing two widely used positive probes (EUB338 and UNIV1392), provided poor results. The maximum positive/negative ratio, 2.47, was achieved with paraformaldehyde-fixed Prochlorococcus cells by using UNIV1392 and NON338 (Fig. 1) and was much below that achieved with PNA probes (see below). Use of DNA probes in Prochlorococcus was not pursued further.

FIG. 1.

Frequency distribution of oligonucleotide (DNA) probe-conferred fluorescence in Prochlorococcus strain SS120 cells hybridized with a positive probe, UNIV1392, and a negative control probe, NON338.

PNA protocol optimization.

The PNA protocol was designed and optimized in order to achieve the largest possible ratio between positive and negative probe signals, for example, 11.27 in Prochlorococcus SS120. Two PNA probes were used in all experiments: pEUB339, which should bind to most bacteria (including all the strains used in this study), and pNEG1198, which should not bind to any cyanobacterium (Table 1). These probes are composed of 11 bases rather than the 16 to 18 bases commonly used for DNA probes (1, 14) because of the stronger binding to complementary sequences and higher level of specificity in discriminating mismatched base pairs expected with PNA probes. The hybridization temperature was chosen based on the theoretical temperature of dissociation (Td). Td was calculated according to the formula of Suggs et al. (32), Td = [4(G + C) + 2(A + T)], with an additional 1°C added per base in order to adjust the formula for use with PNAs (10, 32; PerSeptive Biosystems Product Information). The calculated Tds for pEUB339 and pNEG1198 are 48 and 44°C, respectively. Because Td based on this calculation is only an approximation, a series of experiments were conducted to ascertain the optimal hybridization and was temperatures in Prochlorococcus cells. Hybridization temperatures below 30°C and above 40°C provided a suboptimal signal. A range of hybridization temperatures from 31 to 37°C provided comparable results. Because the Td of pEUB339 is higher than that of pNEG1198, it was necessary to ascertain that optimal conditions for the positive probe did not bias the protocol for a low negative signal. Several different hybridization and wash temperatures were tested. The pNEG1198 mean fluorescence was 6.7, 6.5, and 6.7, respectively, for a sequence of hybridization-wash temperatures of 31-34, 34-34, and 34-37°C. The pEUB339 mean fluorescence in each case was above 50. Wash temperatures above 40°C diminished probe signals; the maximum wash temperature tested was 44°C. In accordance with these results our standard protocol uses 34°C for the hybridization and 37°C for the wash.

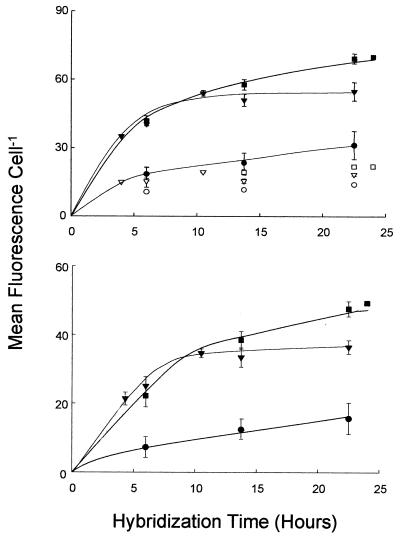

Experiments were conducted to determine optimal hybridization time and probe concentration (Fig. 2). Mean fluorescence per cell stabilized after 9 h at the intermediate concentration (2.1 μg ml−1, final PNA concentration) of PNA probe. The signal from the lowest probe concentration (0.85 μg ml−1) was much lower than that from the intermediate concentration at all times tested. The highest probe concentration (4.3 μg ml−1) yielded fluorescence similar to that of the intermediate concentration up to 14 h but appeared to increase further thereafter. Routine hybridization times were therefore allowed to range from 9 to 14 h at the intermediate concentration (2.1 μg ml−1, final PNA concentration).

FIG. 2.

Effect of hybridization time and PNA concentration (0.85 μg ml−1 [●], 2.1 μg ml−1 [▾], and 4.3 μg ml−1 [■]) on mean cellular fluorescence (± standard errors) in Prochlorococcus strain SS120. (Top) Gross fluorescence of the positive (pEUB339) (closed symbols) and negative (pNEG1198) (open symbols) probes. (Bottom) Negative-probe-conferred fluorescence has been subtracted from that of the positive probe.

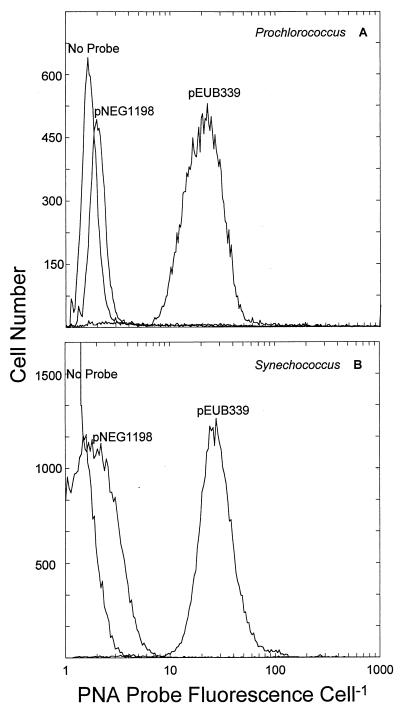

Probing Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus.

The standard hybridization protocol, defined according to the above results (see Materials and Methods), yielded a mean positive probe fluorescence (pEUB339) that was always higher than that of the negative probe (pNEG1198) and the no-probe control in Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus cells (Fig. 3). There was no overlap between the positive and negative signal in either organism (Fig. 3). The no-probe control demonstrated that positive probe signal was not the result of autofluorescence from photosynthetic pigments and was used to ascertain the extent of nonspecific binding by the pNEG1198 probe. This nonspecific binding was detectable, though quite low, as reflected by the slight increase in fluorescence conferred by pNEG1198 relative to the no-probe treatment (Fig. 3). Representative hybridization results for two Prochlorococcus and two Synechococcus strains are presented in Table 2. pEUB339 fluorescence was stable from 0.5 to 2 times the standard cell concentration (data not shown). However, very low cell concentrations (10-fold dilution) resulted in a lower positive signal. Therefore, it may be possible to generate a misleadingly low positive signal below a critical cell concentration. The cause of this effect is unknown at present.

FIG. 3.

Frequency distribution of PNA-conferred fluorescence of Prochlorococcus strain SS120 cells and Synechococcus strain WH8101 cells hybridized with the positive probe (pEUB339), the negative probe (pNEG1198), or no probe.

TABLE 2.

Representative PNA whole-cell hybridization results for different strains

| Strain | Fluorescencea

|

Growth rate (d−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pEUB339 | pNEG1198 | ||

| SS120 (Prochlorococcus) | 94.8 ± 7.8 | 14.4 ± 1.2 | 0.41 |

| MED4 (Prochlorococcus) | 110.8 ± 0.2 | 12.3 ± 0.4 | 0.62 |

| WH8101 (Synechococcus) | 165.4 ± 2.8 | 15.2 ± 0.7 | 1.41 |

| WH8007 (Synechococcus) | 103.2 ± 4.1 | 20.5 ± 0.8 | 1.42 |

Values are means ± standard errors for duplicate samples. All values were normalized to the bead fluorescence values.

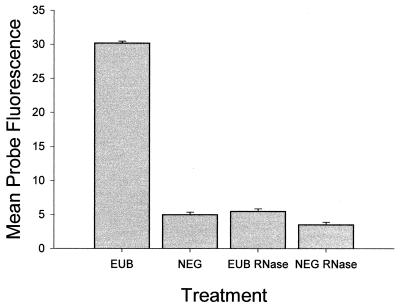

RNase control.

To ensure that PNA probes were hybridizing to RNA, Prochlorococcus cells were treated with RNase and then hybridized with probes. This treatment reduced the pEUB339-conferred fluorescence to the negative-control levels (Fig. 4). This result confirmed that the pEUB339 fluorescence was due to binding of RNA and not nonspecific binding to some other cellular component. The mean fluorescence from pNEG1198 was slightly higher in the control than in RNase-treated cells, indicating that nonspecific or “negative-probe” fluorescence may be due in part to nonspecific binding of RNA.

FIG. 4.

Effect of RNase on PNA-conferred fluorescence in Prochlorococcus strain SS120 (EUB) pEUB339 and NEG (pNEG1198). Error bars show standard errors.

rRNA quantitation.

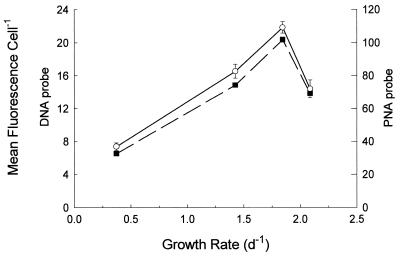

Because it has been established that DNA probes can quantify cellular rRNA in Synechococcus (5), we assessed the quantitative abilities of PNA probes by comparing them to that of DNA probes in Synechococcus strain WH8007 growing over a range of growth rates (Fig. 5). Cellular rRNA based on PNA probes was very well correlated with DNA-based measurements (r = 0.99). Although PNA probe fluorescence was fivefold higher than DNA probe fluorescence, the positive-to-negative signal ratios for both types of probes were comparable. The observed relationship between cellular rRNA content (as reflected by probe-conferred fluorescence) and growth rate is consistent with that reported for a closely related strain (5).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of DNA and PNA probes in Synechococcus strain WH8007. Mean fluorescence conferred by pEUB339 (○) and EUB338 (■) in cells growing at four different light-limited growth rates is shown. Data were corrected for fluorescence from corresponding negative probes. Error bars indicate standard errors for pEUB339 and pNEG1198 fluorescences; standard errors for EUB338 are not shown, but they averaged 7% of the mean.

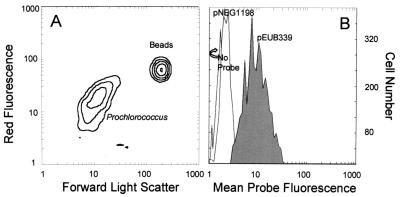

Probing of a natural population.

Seawater was taken from an open-ocean environment in which Prochlorococcus numbers (8.6 × 104 cells ml−1) exceeded Synechococcus numbers (1.9 × 103 cells ml−1) by 45-fold. The natural chlorophyll signal of Prochlorococcus present after the hybridization procedure allowed easy definition of that population (Fig. 6A). After hybridization Synechococcus were hard to distinguish as a population due to low cell numbers. In addition, fluorescence from the phycobiliproteins of open-ocean Synechococcus is likely to spill over into the range of emission for the fluorescein-labeled probes used in this work. Choice of a different fluorochrome for whole-cell hybridizations of Synechococcus in open-ocean environments may circumvent this problem. Prochlorococcus cells from the Pacific Ocean sample showed a 5.1-fold difference between mean fluorescence conferred by pEUB339 and pNEG1198, respectively (Fig. 6B). Despite this modest positive-to-negative ratio, the overlap between the positive and negative signal was minimal. The relatively low positive signal for this Prochlorococcus population may reflect a lower growth rate in the natural environment, which would be expected to result in reduced cellular rRNA content (5, 9, 19).

FIG. 6.

In situ hybridization of natural Prochlorococcus population. (A) Flow cytometric signature of Prochlorococcus (with 0.474-mm-diameter latex beads) showing forward angle light scatter (related to size) versus red fluorescence (from chlorophyll). (B) Probe-conferred fluorescence of Prochlorococcus cells as defined from panel A, hybridized with positive probe (pEUB339), negative probe (pNEG1198), and no probe. Water was collected from the Pacific Ocean in an oligotrophic region off the California coast.

Conclusions and future directions.

Although the focus of PNA-based research has been primarily eukaryotic, PNA probes have been used with success in other bacterial systems. For example, the sensitivity of PNA probes to mismatches has been exploited to discriminate, on the basis of a single mismatch, between intact cells of the closely related bacteria Neisseria gonorrhoea and Neisseria meningitidis (30). Two other studies have demonstrated the use of antisense PNA targeting mRNA to inhibit gene expression in E. coli (16, 17).

We have demonstrated that PNA can be used to probe rRNA in intact Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus cells. Unlike many other whole-cell hybridization protocols, the PNA protocol employs preservation and hybridization conditions that minimize impact on the integrity and characteristics of these cells, thus allowing application to field populations. Furthermore, the high sensitivity to mismatches and strong access to target sites may facilitate detection of slight phylogenetic differences in the natural environment. Combined with flow cytometry, the method presented here will facilitate gathering data at both the molecular and organismic level in mixed microbial communities and should therefore enhance our understanding of the ecology of those communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brian Palenik for providing cruise space on the R/V New Horizon; Gerardo Toledo, Jim Wilkinson, and the captain and the crew of the R/V New Horizon for facilitating field sampling; Q. Eastman for PNA encouragement; Y. C. Liu for laboratory technical assistance; G. Rocap for performing GCG probe matches; R. Gausling for helpful discussions and much assistance; M. Polz and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Georgia Sea Grant College Program (grant R/AT-4-PD) to A.Z.W. and B.J.B. and from the National Science Foundation to B.J.B. (OCE-9711306) and to S.W.C. (OCE-9820035). A.Z.W. is supported by a NASA Earth Systems Science Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R, Ludwig W, Schleifer K. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bidigare R R, Ondrusek M E. Spatial and temporal variability of phytoplankton pigment distributions in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean. Deep-Sea Res II. 1996;43:809–833. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder B J, Chisholm S W, Olson R J, Frankel S L, Worden A Z. Dynamics of pico-phytoplankton, ultra-phytoplankton, and bacteria in the central equatorial Pacific. Deep-Sea Res Part II. 1996;43:907–931. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binder B J, Liu Y C. Growth rate regulation of rRNA content of a marine Synechococcus (cyanobacterium) strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3346–3351. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3346-3351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder B J, Chisholm S W. Relationship between DNA cycle and growth rate in Synechococcus strain. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2313–2319. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2313-2319.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell L, Nolla H A, Vaulot D. The importance of Prochlorococcus to community structure in the central North Pacific Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr. 1994;39:954–961. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm S W. Phytoplankton size. In: Falkowski P G, Woodhead A D, editors. Primary productivity and biogeochemical cycles in the sea. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delong E F, Wickham G S, Pace N R. Phylogenetic stains: ribosomal RNA-based probes for the identification of single cells. Science. 1989;243:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.2466341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freler S M, Driver D A, Berg R H, Kim S K, Norden B, Nielsen P E. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding rules. Nature. 1993;365:266–268. doi: 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris M J, Palenik B. Niche adaptation in ocean cyanobacteria. Nature. 1998;396:226–228. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs B M, Wallner G, Beisker W, Schwippl I, Ludwig W, Amann R. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4973-4982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangamani B P, Kumar V A, Ganesh K N. Spermine conjugated peptide nucleic acids (spPNA): UV and fluorescence studies of PNA-DNA hybrids with improved stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:778–782. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giovanonni S J, Delong E F, Olsen G J, Pace N R. Phylogenetic group-specific oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the identification of single microbial cells. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:720–726. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.720-726.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovanonni S J, Britschgi T B, Moyer C L, Field K G. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature. 1990;345:60–63. doi: 10.1038/345060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good L, Nielsen P E. Antisense inhibition of gene expression in bacteria by PNA targeted to mRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:355–358. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Good L, Nielsen P E. Inhibition of translation and bacterial growth by peptide nucleic acid targeted to ribosomal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2073–2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmsen H J M, Prieur D, Jeanthon C. Group-specific 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes to identify thermophilic bacteria in marine hydrothermal vents. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4061–4068. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4061-4068.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemp P F, Lee S, Laroche J. Estimating the growth rate of slowly growing marine bacteria from RNA content. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2594–2601. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2594-2601.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maidak B L, et al. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore L R, Goericke R, Chisholm S W. Comparative physiology of Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus: influence of light and temperature on growth, pigments, fluorescence and absorptive properties. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1995;116:259–275. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore L R, Rocap G, Chisholm S W. Physiology and molecular phylogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature. 1998;393:464–467. doi: 10.1038/30965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore L R, Chisholm S W. Photophysiology of the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus: ecotypic differences among cultured isolates. Limnol Oceanogr. 1999;44:628–638. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen P E, Egholm M, Berg R H, Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Partensky F, Hoepffner N, Li W K, Ulloa O, Vaulot D. Photoacclimation of Prochlorococcus sp. (prochlorophyta) strains isolated from the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:285–296. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polz M F, Cavenaugh C M. Bias in template-to-product ratios in multitemplate PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3724–3730. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3724-3730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanlan D J, Hess W R, Partensky F, Newman J, Vaulot D. High degree of genetic variation in Prochlorococcus (Prochlorophyta) revealed by RFLP analysis. Eur J Phycol. 1996;31:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schonhuber W, Zarda B, Eix S, Rippka R, Herdman M, Ludwig W, Amann R. In situ identification of cyanobacteria with horseradish peroxidase-labeled, rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1259–1267. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1259-1267.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sen S, Nilsson L. Molecular dynamics of duplex systems involving PNA: structural and dynamical consequences of the nucleic acid backbone. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:619–631. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stefano K, Hyldig-Nielsen J J. Diagnostic applications of PNA oligomers. In: Minden S, editor. Diagnostic gene detection and quantification technologies for infectious agents and human genetic diseases. Southborough, Mass: IBC Library Series. International Business Communications, Inc.; 1997. pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stockner J G, Antia N J. Algal picoplankton from marine and freshwater ecosystems: a multidisciplinary perspective. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1986;43:2472–2503. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suggs S V, Hirose T, Miyake T, Kawashima E H, Johnson M J, Itakura K, Wallace R B. Use of synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides for the isolation of specific cloned DNA sequences. In: Brown D, Fox C F, editors. Developmental biology using purified genes. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1981. pp. 683–693. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki M, Giovanonni S J. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:625–630. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.625-630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledo G, Palenik B. Synechococcus diversity in the California current as seen by RNA polymerase (rpo C1) gene sequences of isolated strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4298–4303. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4298-4303.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urbach E, Scanlan D J, Distel D L, Waterbury J B, Chisholm S W. Rapid diversification of marine picophytoplankton with dissimilar light-harvesting structures inferred from sequences of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (cyanobacteria) J Mol Evol. 1998;46:188–201. doi: 10.1007/pl00006294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urbach E, Chisholm S W. Genetic diversity in uncultured Prochlorococcus populations flow cytometrically sorted from the Sargasso Sea and the Gulf Stream. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43:1615–1630. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaulot D, Courties C, Partensky F. A simple method to preserve oceanic phytoplankton for flow cytometric analyses. Cytometry. 1989;10:629–635. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterbury J B, Watson S W, Valois F W, Franks D G. Biological and ecological characterization of the marine unicellular cyanobacteria Synechococcus. Can Bull Fish Aquat Sci. 1986;214:71–120. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisse T. Dynamics of autotrophic picoplankton in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Adv Microb Ecol. 1993;13:327–370. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood A M, Phinney D A, Yentsch C S. Water column transparency and the distribution of spectrally distinct forms of phycoerythrin containing organisms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1998;162:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zarda B, Amann R, Wallner G, Schleifer K. Identification of single cell bacteria using dioxigenin-labelled, rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2823–2830. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-12-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]