Abstract

Background

Wasting continued to threaten the lives of 52 million (7.7%) under-five children globally. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for one-third of all wasted children globally, and Ethiopia is among the countries with the highest magnitude of Wasting in the region. Despite, the little decrement in the prevalence of other forms of malnutrition (stunting and underweight), the burden of wasting remains the same in the country. Gedeo zone is among those with a high prevalence of under-five wasting.

Objective

To identify determinants of wasting among children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, 2018.

Methods

A facility-based unmatched case-control study was conducted from May 11 to July 21/2018. A total of 356 (119 cases and 237 controls) mothers/caregivers of under-five children who visited the Wonago woreda public health facilities were included in the study using systematic random sampling. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire and anthropometric measurement. Descriptive analysis was used to describe data. Binary logistic regression was used to identify determinants of wasting among children aged 6–59 months. Variables with p-value < 0.25 in bi-variate analysis entered to multivariate analysis. Those variables with a p-value less than 0.05 during the multivariate regression were considered significant.

Results

Determinants which found to have an association with wasting in this study were; maternal illiteracy [AOR = 2.48, 95% CI (1.11, 5.53)] family size <3 [AOR = 0.16, 95% CI (0.05, 0.50)] wealth index [AOR = 2.41, 95% CI (1.07, 5.46)] exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months [AOR = 2.71, 95% CI (1.15, 6.40)] dietary diversity [AOR = 5.52, 95% CI (2.06, 14.76)] and children been sick in the last 2 weeks [AOR = 4.36, 95% CI (2.21, 8.61)].

Conclusion and recommendations

Determinants identified were maternal education, family size, wealth index, and exclusive breastfeeding, dietary diversity, and morbidity history of a child in the last 2 weeks. To reduce childhood wasting, due emphasis should be given to empowering women and improving the knowledge and practice of parents on appropriate infant and young child-caring practices.

Introduction

Malnutrition is an abnormal physiological condition caused by deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in energy, protein, and/or other nutrients, expressed in the form of over nutrition (obesity) or under-nutrition [1]. Child under-nutrition is a major public health problem, especially in many low-income and middle-income countries [2]. Child malnutrition is responsible for approximately 45 percent of under-five child mortality due to common illnesses, with the majority of deaths occurring in moderately malnourished children [3]. Poor nutrition is linked to suboptimal brain development, which has a negative impact on adult cognitive development, educational performance, and economic productivity [4].

When a child’s nutritional status deteriorates in a relatively short period of time, his or her weight drops to such a low level that they are at risk of dying, the child is said to have acute malnutrition, which is manifested by wasting and being underweight [5].

Wasting refers to a child who is too thin for his/her height and occurs when there is recent rapid weight loss or the failure to gain weight [6]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2009 child growth standards and identification of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children, wasted children have a weight-for-height ratio of less than -3 SD and/or a MUAC of less than 12.5 cm [7].

Globally, child waste remains a critical issue; its consequences are long-lasting and extend beyond childhood, for example, causing wasted children to have weakened immunity, be vulnerable to long-term developmental delays, and face an increased risk of death [8].

Globally, an estimated of 7.7% and 2.5% of under-five children are wasted and severely wasted, respectively [8]. According to the 2015 Millennium development goal (MDG) report, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounts for one-third of all wasted children globally, highlighting that wasting still remains a major health problem for children under 5 years in the sub-region, thus showing the need for urgent intervention [9]. Ethiopia is among countries with the highest magnitude of wasting in Sub-Saharan African countries [10].

Being a caretaker living alone [11], poor socioeconomic status and parental illiteracy [12], being in the age group of less than 2 years, birth spacing less than 2 years [13], having large family sizes [14], children aged 12–23 months [15], nonexclusive breastfeeding [16], and suboptimal frequency of complementary feeding [17] are risk factors associated with child wasting. A study was done in the Tigray region also mentioned that children from households who were used for unprotected sources of water were 3.5 times more likely to be wasted compared to protecting sources [18].

Furthermore, cases of high wasting continue to be reported in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia including: Dilla Zuria, Wonago, Kochore, Bule, and Yirga Cheffe woredas of Gedeo zone, hence they are ranked under priority one for hot spot classification of areas with high malnutrition and food insecurity [19].

In majority of the study, only a few factors like sociodemographic characteristics, breast milk feeding history and maternal and child health service utilization history were repeatedly studied with the same study design and uniform insight across the studies. Variable such as wealth index of the family, families access to variety of food items, the child’s exposure to diverse food groups (dietary diversity score) as well as maternal knowledge, attitude and practices towards adequate child feeding practice were not studied in majority of the studies although, these factors were frequently reported to be predictors of child nutritional status in several researches conducted in other abroad countries. Therefore, this study was aimed to fulfill the above mentioned knowledge gaps and investigate the major determinants of wasting among children aged 6–59 months in the Wonago woreda Gedeo zone, Southern Ethiopia since there are different factors that predispose children to the risk of wasting.

Methods and materials

Study design

An Institutional based unmatched case-control study was conducted from May11- July 21, 2018.

Study setting

The study was conducted in Wonago Woreda, which is one of the 6 Woredas in the Gedeo zone, SNNPRS (Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Regional State), Ethiopia. The Woreda is found 377 km far away from the capital city, Addis Ababa in the southern direction and 102 km from the region capital Hawassa. The Woreda has 21 kebeles (17 rural and 4 urban) and hosts a total population of 156,480 within 30,442 households. The majority of the population is Gedeo ethnic group. Six health centers, 20 health posts, and 2 private clinics provide the overall health care service in the Woreda. The total number of under-five children in the year 2016 was 4,758 [20].

Population

All children aged 6–59 months who lived in Wonago woreda where source population and all children aged 6–59 months and who visited health care facilities in Wonago Woreda for varies health care services during the study period were studied population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All children who are a permanent resident or who have lived at least 6 months in wonago woreda aged 6–59 months who visited the health facilities and who have wasted (MUAC<12.5 cm), with their caregivers/mothers who were given informed consent enrolled into the study as cases. Controls included children aged 6–59 months, whose MUAC >12.5 cm and attend health facilities with their mothers/caregivers, who were given informed consent enrolled into the study as controls.

Exclusion criteria

Children with physical deformities (children born without hands due to congenital deformities, wounded, and burned hands), children in critical health conditions which made anthropometric measurements inconvenient, and mothers/caregivers who are seriously ill and unable to respond to the questions was excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated by using Epi-Info version 7 Statistical software by using two population proportions formula with the following assumptions: Squeeze out of first breast milk was taken with proportion of who didn’t squeeze out of first breast milk of the controls to be 53.92% and of the cases 70.1%, 95% confidence interval, 80% power of the study, control to case ratio of 2:1 to detect an odds’ ratio of 2.00 with a 5% of non-response rate [21]. Thus, the sample size required for the study was 366 (122 cases and 244 controls).

Sampling procedure

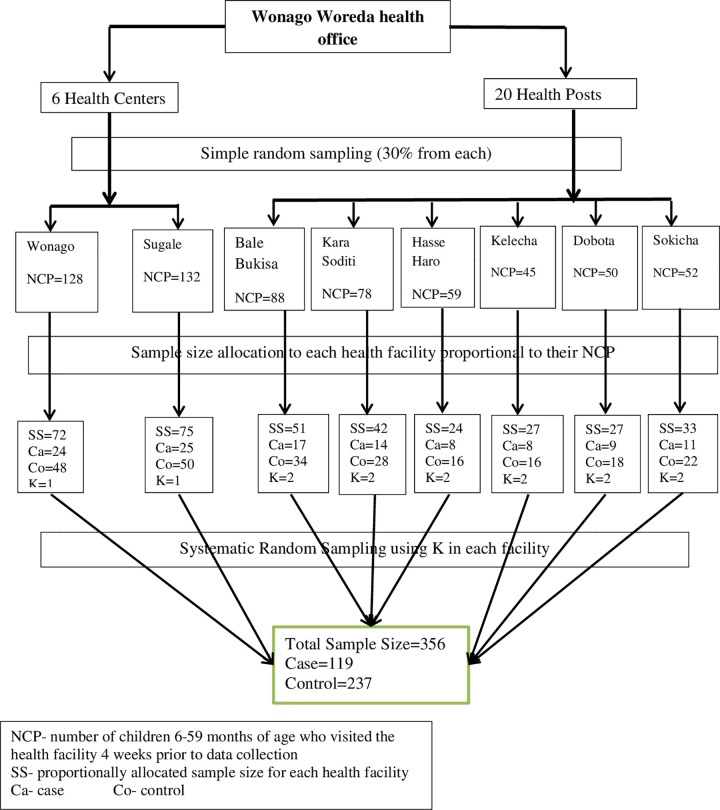

The systematic random sampling technique was applied to select mothers of children aged 6–59 months visiting Wonago public health facilities (health center and health post) for interviews during the study period. The sampling procedure, in general, was as follows: first, the last 4 weeks data of children aged 6–59 months in both public health facilities were taken for the purpose of sample allocation and to determine their sharing’s (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Schematic presentation of sampling procedure for the study on determinants of acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in study area, 2018.

Data collection instruments and procedures

The data were collected using a structured questionnaire via face-to-face interviews and anthropometric measurements. Data were collected by structured questionnaire from all eligible children’s mothers/caregivers using a face-to-face interview with 10 Data collectors (4 nurses and 6 health extension workers) and 2 supervisors who have bachelor degrees in public health. It was done under close supervision of the assigned supervisors and principal investigator. A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was adopted after a detailed review of different pieces of literature and was used to collect data related to the objectives of this study. The questionnaire covered a range of topics including socioeconomic and demographic factors, child characteristics and child-caring practices, maternal characteristics, and environmental health conditions.

The anthropometric data were collected using the procedure set by the WHO (2009) for taking anthropometric measurements. In order to ensure the target population, the age of children was determined before taking anthropometric data. To establish the birth period a local event was used and the mothers or caregivers were asked whether the child was born before or after certain major events until a fairly accurate age was pinpointed. For anthropometric measurement, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was used. MUAC was measured by using a tape meter based on the WHO standardized procedures. Finally, the obtained data of the child were categorized in the wasted and not wasted group according to WHO standard criteria. Edema was checked and determined as per the standard set by WHO, because children with edema were severely malnourished.

To identify the previous sickness of children, mothers were asked about any occurrence of illness during the past two weeks and the vaccination status of children was also checked by observing immunization cards and vaccination scars. Once a case was found and his or her caregiver interviewed, two controls meeting the criteria were selected, and their caregivers were interviewed.

Data quality management

The questionnaire was first prepared in English then translates into Amharic and Gede-ufa and back-translated into English by independent translators to check its consistency. Consensus on the compatibility of forward and backward translation was assured before the actual data collection activities.

Data collectors and supervisors were trained for two days by the principal investigator before the actual study commenced on the objectives of the study, Anthropometric measurements, how to interview, and how to handle the questions asked by study subjects. As part of the training, the data collection tool was pre-tested in 5% of the sample size at Dilla zuria wereda (adjacent to the study area) before the actual data collection time to check the extent to which questions understand by the interviewee and to identify areas for modification and correction. Based on the pretest, some chronological arrangements were made. The principal investigator and supervisors checked the completeness and consistency of collecting data on a daily basis, and necessary feedback was given to the data collectors.

Before data entry, in order to make data processing easier, a code was given to each questioner. And data entry format was prepared in Epi Data software according to the pre-coded questioner. To reduce some errors during data entry, a check file was developed (to detect and refuse some data entry mistakes). Before conducting analysis in SPSS software, data cleaning was done to check the presence of outliers, to check consistency, and to verify the skip pattern was followed. In addition, exploratory data analysis was carried out to check the levels of missing values.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was first coded and entered into a computer using EPI data software version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 20 statistical software for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequencies or proportions were presented by tables and figures. In order to investigate determinants of wasting, both bivariate and multivariate analysis was used. Those variables’ p-value of less than or equal to 0.25 in the bivariate was selected as candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Multicollinearity was checked by variance inflation factor (VIF). Statistical significance was declared at P-value less than 0.05. Significance of association of the variables was described using AOR with 95% confidence interval.

Operational definition

Wasting: nutritional deficiency state of recent onset related to sudden food deprivation or malabsorption utilization of nutrients which results in weight loss, MUAC < 12.5 cm from the WHO standard value [7].

Household dietary diversity: dietary diversity is defined as the diversity of plants, animals, and other organisms used as food, covering the genetic resources within species, between species, and provided by ecosystems [22].

Poor dietary diversity: Children who have < 3 food groups.

Good dietary diversity: Children who have > 4 food groups.

Handwashing practice: mean score for all constructs was computed and dichotomized into positive and negative. If the mother scored below the mean, she would be labeled as having poor handwashing practice [23].

Sources of drinking water: according to WHO [24].

Improved water source: piped water to premises, Public taps or standpipes, tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, Rainwater collection.

Unimproved water source: surface water, unprotected dug well, unprotected spring, Cart with small tank/drum, Surface water, bottled water.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Dilla University College of Medicine and Health Science, School of Public and Reproductive Health. Then by explaining the importance and the intention of the study, an official letter of co-operation was taken from the Wonago health office. Written informed consent from parents/caretakers of the study subject was obtained after the objective of the study was explained to them. Privacy and confidentiality of collecting information were insured at all levels. Participants were assured that if they wish to refuse to participate, their care or dignity has not compromised in any way. Participants also were informed that there is no expectation of additional treatment or any associated benefits and risks for them participating in the study.

Results

A total of 356 children between the ages of 6–59 months participated in this study with a response rate of 97%. Study participants were selected in accordance with for every one case selected systematically two children were selected as control, i.e. case to control the ratio of 1:2. Thus, data analysis was done based on data collected from 119 cases and 237 controls.

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics of the study participants

More than half of the children included in the study were male in sex 190 (53.4%). A majority, 255 (71.6%) of the children, were in the age range of under 12 months. About 345 (96.9%) of the children’s families were living together, married, at the time of the data collection. The majority 296 (83.5%) of the participants were rural inhabitants. And 290 (81.5%) children’s families were protestant in their religion and 80.6% of them were Gedeo in ethnicity (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic and economic characteristics among children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, South Ethiopia, November 2018.

| Characteristics | Frequency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Child’s age | ||||||

| < 12 | 90 | 75.6 | 165 | 69.6 | 255 | 71.6 |

| 12–24 | 16 | 13.4 | 33 | 13.9 | 49 | 13.8 |

| > 24 | 13 | 10.9 | 39 | 16.5 | 52 | 14.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 111 | 93.3 | 234 | 98.7 | 345 | 96.9 |

| Divorced | 5 | 4.2 | 2 | 0.8 | 7 | 2.0 |

| Widowed | 3 | 2.5 | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Maternal education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 63 | 52.9 | 102 | 43.0 | 165 | 46.3 |

| Literate | 56 | 47.1 | 135 | 57.0 | 191 | 53.7 |

| Paternal education | ||||||

| No formal education | 36 | 30.3 | 41 | 17.3 | 77 | 21.6 |

| Formal education | 83 | 69.7 | 196 | 82.7 | 279 | 78.4 |

| Maternal occupation | ||||||

| House wife | 87 | 73.1 | 137 | 57.8 | 224 | 62.9 |

| Farmer | 19 | 16.0 | 23 | 9.7 | 42 | 11.8 |

| Daily laborer/ merchant/employee | 13 | 10.9 | 77 | 32.4 | 90 | 25.3 |

| Paternal occupation | ||||||

| Farmer | 67 | 56.3 | 70 | 29.5 | 137 | 38.5 |

| Daily laborer | 49 | 41.2 | 102 | 43.0 | 151 | 42.4 |

| Merchant | 2 | 1.7 | 49 | 20.7 | 51 | 14.3 |

| Employee | 1 | 0.8 | 16 | 6.8 | 17 | 4.8 |

| Family size | ||||||

| < 3 | 10 | 8.4 | 46 | 19.4 | 56 | 15.7 |

| 3–4 | 26 | 21.8 | 63 | 26.6 | 89 | 25.0 |

| ≥5 | 83 | 69.7 | 128 | 54 | 211 | 59.3 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Very poor | 58 | 48.7 | 61 | 25.7 | 119 | 33.4 |

| Poor | 29 | 24.4 | 89 | 37.5 | 118 | 33.2 |

| Rich | 32 | 26.9 | 87 | 36.8 | 119 | 33.4 |

Child caring practice characteristics of the study participants

Overall, about 84.3% of the children in the current study were put into breastfeeding immediately after birth. Of all children, around three fourth (72.8%) were breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months after birth (Table 2).

Table 2. Child caring practice characteristics among children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, South Ethiopia November 2018.

| Characteristics | Frequency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Total | ||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Early initiation of breast feeding | ||||||

| Yes | 82 | 68.9 | 218 | 92.0 | 300 | 84.3 |

| No | 37 | 31.1 | 19 | 8.0 | 56 | 15.7 |

| Exclusive breast feeding under 6 months | ||||||

| Yes | 66 | 55.5 | 193 | 81.4 | 259 | 72.8 |

| No | 53 | 44.5 | 44 | 18.6 | 97 | 27.2 |

| Initiation of complementary feeding | ||||||

| <6 months | 26 | 21.8 | 8 | 3.4 | 34 | 9.6 |

| 6–12 months | 30 | 25.2 | 172 | 72.6 | 202 | 56.7 |

| 13–24 months | 61 | 51.3 | 35 | 14.8 | 96 | 27.0 |

| >24months | 2 | 1.7 | 22 | 9.3 | 24 | 6.7 |

| Frequency of complementary feeding | ||||||

| ≤2meal/day | 74 | 62.2 | 157 | 65.8 | 228 | 64.6 |

| ≥3meal/day | 45 | 37.8 | 80 | 34.2 | 128 | 35.4 |

| Dietary diversity | ||||||

| Good | 8 | 6.7 | 83 | 35.0 | 91 | 25.6 |

| Poor | 111 | 93.3 | 154 | 65.0 | 265 | 74.4 |

Child health status and health service utilization characteristics of the study participants

The majority of study participants 236 (66.3%) both in cases 65 (54.6%) and controls 171 (72.2%) do not take drugs for the intestinal parasites in the past 6-month prior to the date of the survey. Among all 181 (52.0%) children and from control, 153 (64.6%) children have not been sick in the last 2 weeks before study time. In contrast, from case 87 (73.1%) children have been sick in the last 2 weeks before the study period, among them 73.5% of them had the diarrheal disease. Almost three fourth of all mothers 261 (73.3%) both in cases 76 (63.9%) and controls 185 (78.1%) attended ANC visits during their last pregnancy (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Health service utilization characteristics of children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, South Ethiopia November 2018.

Environmental health and hygiene characteristics of the study participants

Almost all participants 265 (74.4%) of which 186 (78.5%) were from controls and 79 (66.4%) of mothers/caretakers from cases reported that they have access to an improved water source. Conversely, slightly above half 172 (51%) of cases and nearly one in every half 63 (18%) mothers/caretakers from controls reported to have poor handwashing practices. In particular, about 34 (14.7%) and 14 (11.8%) from controls and cases, respectively have reported to lack any form of latrine in their compound or nearby. The majority of the 198 (55.6%) similarly majority in cases do not treat drinking water before consumption, but the majority of respondents 127 (53.6%) among controls are able to treat drinking water before consumption. In addition, around half of all participants 172 (48.3%) and the majority 139 (58.6%) of controls remove solid waste by damping to the ground by composting. Unlike control’s majority, 69 (58.0%) of respondents from cases remove solid waste in an open field.

Determinants of wasting among children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, South Ethiopia

In order to investigate determinants of wasting, both bivariate and multivariate analysis was used. Those variables’ p-value of less than or equal to 0.25 in the bivariate was selected as candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression analysis. Variables which significantly associated in bivariate analysis were: Paternal education, Family size, Wealth index, Early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months, Children who started complementary feeding at age <6 months, Dietary diversity, Vaccination for measles, De-worming in the last 6 months, Vit A in the last 6 months, Children who have been sick in the last 2 weeks, Source of drinking water, Method of waste disposal, Handwashing practice.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis was used by taking all such factors into account simultaneously, and only the following seven of the most contributing factors remained to be significantly and independently associated with wasting. Determinants that were significantly associated with wasting in this finding were; maternal illiteracy, Family size, Wealth index, Exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months, Dietary diversity, Children who have been sick in the last 2 weeks.

Maternal illiteracy was showing a statistically significant association with the outcome variables. Those children whose mother had no formal education had 2.48 times higher risk of wasting as compared to those children whose mother had formal education [AOR = 2.48, 95% CI (1.11, 5.53)]. Family size was shown a statistically significant association with the outcome variables. Those children from family size <3 has 84% less likely to be wasted compared to those who have family size >5 [AOR = 0.16, 95% CI (0.05, 0.50)]. The wealth index is also having a statistically significant association with the outcome variable. Those children from low family wealth index have 2.41 times higher risk of wasting as compared to children from high family wealth index quantile [AOR = 2.41, 95% CI (1.07, 5.46)]. Exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months was shown a statistically significant association with the outcome variable. Those children who didn’t have exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months were 2.71 times higher risk of wasting as compared to those who have exclusively breastfed in the first 6 months [AOR = 2.71, 95% CI (1.15, 6.40)].

Children with poor dietary diversity were found to be 5.52 times more likely to have wasting than Children with good dietary diversity [AOR = 5.52, 95% CI (2.06, 14.76)]. Children who have been sick in the last 2 weeks preceding data collection were found to be 4.36 times at high risk of developing wasting as compared to those who have not been sick in the last 2 weeks preceding data collection [AOR = 4.36, 95% CI (2.21, 8.61)] (Table 3).

Table 3. Determinants of wasting among children aged 6–59 months in Wonago Woreda, South Ethiopia November 2018.

| Variable | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Maternal education | |||||

| No formal education | 63 | 102 | 1.48 (0.95, 2.31) | 2.48 (1.11, 5.53) | 0.02 |

| Formal education | 56 | 135 | 1 | 1 | |

| Paternal education | |||||

| No formal education | 36 | 41 | 2.07 (1.23, 3.47) | 2.11 (0.85, 5.21) | 0.10 |

| Formal education | 83 | 196 | 1 | 1 | |

| Family size | |||||

| < 3 | 10 | 46 | 0.33 (0.16, 0.70) | 0.16 (0.05, 0.50) | < 0.01 |

| 3–4 | 26 | 63 | 0.63 (0.37, 1.08) | 0.18 (0.07, 0.45) | < 0.01 |

| ≥5 | 83 | 128 | 1 | 1 | |

| Wealth index | |||||

| Low | 58 | 61 | 2.58 (1.50, 4.44) | 2.41 (1.07, 5.46) | 0.03 |

| Middle | 29 | 89 | 0.88 (0.49, 1.58) | 1.79 (0.78, 4.06) | 0.16 |

| High | 32 | 87 | 1 | 1 | |

| Early initiation of breast feeding | |||||

| Yes | 82 | 218 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 37 | 19 | 5.17 (2.81, 9.51) | 1.99 (0.67, 5.84) | 0.20 |

| Exclusive breast feeding under 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 66 | 193 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 53 | 44 | 3.52 (2.16, 5.73) | 2.71 (1.05, 6.40) | 0.02 |

| Dietary diversity | |||||

| Good | 111 | 154 | 1 | 1 | |

| Poor | 8 | 83 | 7.4 (3.47, 16.07) | 5.52 (2.06, 14.76) | < 0.01 |

| Vaccination for measles | |||||

| Yes | 97 | 221 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 22 | 16 | 3.13 (1.57, 6.22) | 1.59 (0.55, 4.56) | 0.38 |

| De-worming in the last 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 66 | 171 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 53 | 66 | 2.08 (1.31, 3.29) | 0.66 (0.28, 1.57) | 0.35 |

| Vit A in the last 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 182 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 42 | 55 | 1.80 (1.11, 2.92) | 1.85 (0.75, 4.54) | 0.17 |

| Sick child in the last 2 weeks | |||||

| Yes | 85 | 96 | 3.67 (2.28, 5.90) | 4.36 (2.21, 8.61) | < 0.01 |

| No | 34 | 141 | 1 | 1 | |

| Source of drinking water | |||||

| Improved | 79 | 186 | 1 | 1 | |

| Unimproved | 40 | 51 | 1.84 (1.13, 3.01) | 0.63 (0.24, 1.66) | 0.35 |

| Method of waste disposal | |||||

| Open field | 72 | 68 | 2.26 (1.10, 4.64) | 1.20 (0.34, 4.30) | 0.76 |

| Composting | 33 | 139 | 0.50 (0.24,1.06) | 0.34 (0.09, 1.19) | 0.09 |

| Burning | 14 | 30 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hand washing practice | |||||

| Poor practice | 19 | 20 | 2.06 (1.05, 4.03) | 0.81 (0.30, 2.21) | 0.68 |

| Good practice | 100 | 217 | 1 | ||

Discussion

Determinants which significantly associated with wasting in this finding were; educational status of mothers, family size of household, the wealth index of the household, exclusive breastfeeding under 6 months, food security, and dietary diversity.

Among sociodemographic factors in this study, maternal educational status is significantly associated with wasting. Those children whose mother had no formal education had 2.48 times higher risk of wasting as compared to those children whose illiterate mothers [AOR = 2.48, 95% CI (1.11, 5.53)]. In line with this study, a similar study was conducted in Dilla town, Gedeo zone, Children whose mothers are illiterate were 4.18 times more likely to have wasted compared to children whose mothers are literate (AOR = 4.18, CI = (1.36–12.8)) [21].

Similarly, another study conducted in the Oromia region, west Ethiopia; Konso, Southern Ethiopia revealed that those children whose mothers/caregivers are illiterate were more likely to have wasted as compared to those with literate mothers/caregivers [14,25]. This shows that improved maternal education enhances mothers’ knowledge and practice towards child feeding practices, and empowers them to involve in better economic status than their counterparts. Thus, this can be hypothesized as the maternal education may simply be a proxy for child undernutrition factors such as child caring practice and health-seeking behavior which directly affects the children’s nutritional status.

Family size showed a statistically significant association with the outcome variables. Those children from family size <3 has 84% less likely to have wasted compared to those who have family size >5 [AOR = 0.16, 95% CI (0.05, 0.50)]. In line with the finding of this study, a study conducted in the Oromia region, west Ethiopia has large family sizes (AOR = 2.59 (95% CI) (1.34,5.0)) Children from family size greater than or equal to 5 were 2.59 times more at risk to be wasted compared to children from family size less than five [14].

Other similar studies conducted in the Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia and Gobu Sayo Woreda, East Wollega Ethiopia also showed that children from larger family sizes of the household having five and above were more likely to develop wasting as compared to the family size of the household less than five [15,26]. Increased division of available resources in the household results in a nutritional shortfall. This supports the idea that non-nutritional factors should be essential components in the effort to reduce acute malnutrition in Ethiopia. This is due to the fact that mothers who had many Children may not have appropriate child feeding care and nearby mother intimacy.

Another important sociodemographic factor that has a significant effect on the nutritional status of under-five children is the wealth status of the family. Those children from low family wealth index have 2.41 times higher risk of wasting as compared to children from high family wealth index quintile AOR = 2.41, 95% CI (1.07, 5.46). A study conducted in Lalibela Town, North Ethiopia revealed that children living within a household in the highest wealth quintile were 49% less likely to be underweight compared to those children living within a household in the lower wealth quintile AOR = 0.51; (95%CI: 0.28–0.91) [27].

Among child caring practice factors, Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was found to be associated with being wasted. Children who were not exclusively breastfed 6 months of age were 2.71 times more likely to have wasted compared to those who were exclusively breastfed 6 months of age [AOR = 2.71, 95% CI (1.05, 6.40)]. In line with this, a study conducted in Enebsie Sarmidr Woreda, North West Ethiopia showed that children who started complementary feeding before 6 months were 5.81 times at more risk of developing wasting as compared to children who were started complementary feeding at 6 months (AOR = 5.81, 95% CI 1.80–18.79) [16].

Other findings that support the finding of this study were reported from studies conducted in Dilla town, Gedeo zone; Oromia region, West Ethiopia also showed that children who didn’t have exclusive breastfeeding were more likely to develop wasting as compared to those who were exclusively breastfeed [14,21]. When complementary foods are started, there is a reduction in breast milk consumption, which can lead to a loss of protective immunity [28]. This causes a higher morbidity when unhygienic foods are used, leading to diarrheal disease. In addition, inadequate weaning practices and poor infant feeding practices lead to low protein and energy intake [29]

Children with Poor dietary diversity were found to be at higher risk of wasting than Children with Good dietary diversity. Mothers who feed their child less than or equal to 3 food groups were more likely to develop wasting as compared to those who feed greater than three food groups. Children with Poor dietary diversity were found to be 5.52 times more likely to have wasting than Children with Good dietary diversity [AOR = 5.52, 95% CI (2.06, 14.76)]. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Karat Town, Southern Ethiopia revealed that Mothers who feed their child less than or equal to 3 food groups were 5.13 times more likely to develop wasting as compared to those who feed greater than three food groups (AOR = 5.13, 95% CI (1.56, 16.84)) [30].

Dietary assessment help determine the risk of deficiency due to low or high intakes of essential nutrients needed for good health it also serves as a proxy for measurement of the nutritional quality of an individual’s diet and in determining whether the child’s diet has the important elements needed for growth or not, In addition, it is a useful indicator for growth as it can serve as a qualitative measure of food consumption and reflect household access to a variety of foods [31].

From child health status factors, the Morbidity of children in the last two weeks showed a statistically significant association with wasting and them, 73.5% of all morbidity status is attributed to diarrheal disease. Children who have been sick in the last 2 weeks preceding data collection were found to be 4.36 times at high risk of developing wasting as compared to those who have not been sick in the last 2 weeks preceding data collection [AOR = 4.36, 95% CI (2.21, 8.61)]. In line with this study conducted by Shashogo Woreda, Southern Ethiopia showed that the presence of diarrhea 2 weeks preceding the survey increased the risk of wasting by 4.13-fold as compared to those who have no diarrhea (AOR = 4.13, 95% CI 1.34–11.47) [17].

A similar finding was obtained in the study conducted in Machakel Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia, where diarrhea increases the risk of wasting nearest to three times [32]. Infections play a major role in the etiology of undernutrition because they result in increased needs and high energy expenditure, lower appetite, nutrient losses due to vomiting, diarrhea, poor digestion, malabsorption and the utilization of nutrients, disruption of metabolic equilibrium and diarrhea is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of children through dehydration and malnutrition.

Conclusions and recommendations

In this study, several factors like maternal education, family size, and wealth index, exclusive breastfeeding, early initiation of complementary feeding, dietary diversity, and morbidity history of a child in the last 2 weeks were identified as determinants of wasting. Hence, in order to reduce childhood wasting, due emphasis should be given to empowering women and improving the knowledge and practice of parents on appropriate infant and young child-caring practices.

Strength and limitations of the study

The strength of the study was that we have examined multiple determinant factors of wasting. As a limitation it is possible that selection bias may occur since controls were selected from institutions, but efforts were made to differentiate cases and controls through clinical assessment (child history and physical examination) and additionally we made two controls for a single case to minimize such type of selection bias. And also recall bias might occur. But, we have tried to minimize it by using data collectors who were experienced, who know the local languages and community practices and they have helped mothers try to recall by local event recalls like local holidays.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dilla University for granting ethical approval to conduct this research. Our deepest thanks go to all study participants, data collectors, and supervisors who spent their valuable time for the good outcome of the research work.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal Care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CBN

Community based nutrition

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- CSA

Central statistical agency

- EDHS

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey

- GDP

Gross domestic product

- G.Z.H.B

Gedeo zone health bureau

- MAM

Moderate acute malnutrition

- MUAC

Mid upper arm circumference

- OPD

Outpatient department

- PNC

Postnatal Care

- PSNP

Productive safety net program

- SAM

Sever acute malnutrition

- SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

- SNNPR

South nation nationality and people region

- UNICEF

United Nations Children’s Fund

- WFH

Weight for Height

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

All relevant data are included within the paper. The data would be guarded carefully by our research team for the only purpose of this scientific study and it is an ongoing project. Participants were not signed consent for data publicity. For all these reasons and following the indicators of the research review committee of college of health sciences, Dilla University, the authors must not upload the dataset to a stable, public repository. Interested, qualified researchers can access the data by requesting the research review committee of college of health sciences, Alemayehu Molla (alexmolla09@gmail.com) and the corresponding author, Defaru Desalegn (defdesalegn2007@gmail.com).

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2010. World Health Organization; 2010. May 10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. The state of the world’s children 2008: Child survival. Unicef; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. United Nations Children’s Fund. Levels and trends in child mortality 2014.

- 4.Leroy JL, Ruel M, Habicht JP, Frongillo EA. Linear growth deficit continues to accumulate beyond the first 1000 days in low-and middle-income countries: global evidence from 51 national surveys. The Journal of nutrition. 2014. Sep 1;144(9):1460–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.191981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dereje N. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among under five children in Shashogo Woreda, southern Ethiopia: a community based matched case control study. J Nutr Food Sci. 2014. Jan 1;4(5):300. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janevic T, Petrovic O, Bjelic I, Kubera A. Risk factors for childhood malnutrition in Roma settlements in Serbia. BMC public health. 2010. Dec;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young M, Wolfheim C, Marsh DR, Hammamy D. World Health Organization/United Nations Children’s Fund joint statement on integrated community case management: an equity-focused strategy to improve access to essential treatment services for children. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2012. Nov 7;87(5 Suppl):6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNICEF W. Joint child malnutrition estimates: levels and trends. New York, NY: UNICEF. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Health in 2015: from MDGs, millennium development goals to SDGs, sustainable development goals.

- 10.Akombi BJ, Agho KE, Merom D, Renzaho AM, Hall JJ. Child malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2006–2016). PloS one. 2017. May 11;12(5):e0177338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodos J, Altare C, Bechir M, Myatt M, Pedro B, Bellet F, et al. Individual and household risk factors of severe acute malnutrition among under-five children in Mao, Chad: a matched case-control study. Archives of Public Health. 2018. Dec;76(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal S. and Agarwal N., Risk factors for severe acute malnutrition in Central India. Inter J Medical Sci Res Prac, 2015. 2(2): p. 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prashanth M, Savitha MR, Prashantha B. Risk factors for severe acute malnutrition in under-five children attending nutritional rehabilitation centre of tertiary teaching hospital in Karnataka: a case control study. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017. Sep;4(5):1721. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayana AB, Hailemariam TW, Melke AS. Determinants of acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in public hospitals, Oromia region, West Ethiopia: a case–control study. BMC Nutrition. 2015. Dec;1(1):1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seid A, Seyoum B, Mesfin F. Determinants of acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in Public Health Facilities of Pastoralist Community, Afar Region, Northeast Ethiopia: a case control study. Journal of nutrition and metabolism. 2017. Sep 13;2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/7265972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awoke A, Ayana M, Gualu T. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among under five children in rural Enebsie Sarmidr District, East Gojjam Zone, North West Ethiopia, 2016. BMC nutrition. 2018. Dec;4(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dereje N. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among under five children in Shashogo Woreda, southern Ethiopia: a community based matched case control study. J Nutr Food Sci. 2014. Jan 1;4(5):300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassa ZY, Behailu T, Mekonnen A, Teshome M, Yeshitila S. Malnutrition and associated factors among under five children (6–59 Months) at Shashemene Referral Hospital, West Arsi Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Current Pediatric Research. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebreegziabher Z, Mekonnen A, Ferede T, Guta F, Levin J, Köhlin G, et al. The distributive effect and food security implications of biofuels investment in Ethiopia: A CGE analysis. Routledge; 2018. Mar 5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Central statistics Agency, EDHS 2016. 2017: Addis Abeba, Ethiopia.

- 21.Abuka T., Jembere D., and Tsegaw D., Determinants for Acute Malnutrition among Under-Five Children at Public Health Facilities in Gedeo Zone, Ethiopia: A Case-Control Study. Pediatr Ther, 2017. 7: p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demissie S W.A., Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6–59 months of age in pastoral community of Dollo Ado Woreda, Somali region, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health (1:): p. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngure FM, Reid BM, Humphrey JH, Mbuya MN, Pelto G, Stoltzfus RJ. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: making the links. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014. Jan;1308(1):118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO/UNICEF Joint Water Supply, Sanitation Monitoring Programme. Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment. World Health Organization; 2015. Oct 2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eshetu A, Agedew E, Worku A, Bogale B. Determinant of severe acute malnutrition among children aged 6–59 Months in Konso, Southern Ethiopia: Case control study. Q Prim Care. 2016;24:181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tolera G, Wirtu D, Gemede HF. Prevalence of Wasting and Associated Factors among Preschool Children in Gobu Sayo Woreda, East Wollega, Ethiopia. Prevalence. 2014;28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yalew BM. Prevalence of malnutrition and associated factors among children age 6–59 months at lalibela town administration, North WolloZone, Anrs, Northern Ethiopia. J Nutr Disorders Ther. 2014;4(132):2161–0509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogunlesi TA, Oyelami OA. Kwashiorkor-is it a dying disease?. South African Medical Journal. 2007. Jan 1;97(1):65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tessema M, Belachew T, Ersino G. Feeding patterns and stunting during early childhood in rural communities of Sidama, South Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013. May 4;14(1). doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.75.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miskir A, Godana W, Girma M. Determinants of acute malnutrition among under-five children in Karat Town Public Health Facilities, Southern Ethiopia: a case control study. Quality in Primary Care. 2017;25(4):242–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop MC. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bantamen G, Belaynew W, Dube J. Assessment of factors associated with malnutrition among under five years age children at Machakel Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences. 2014. Jan 1;4(1):1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included within the paper. The data would be guarded carefully by our research team for the only purpose of this scientific study and it is an ongoing project. Participants were not signed consent for data publicity. For all these reasons and following the indicators of the research review committee of college of health sciences, Dilla University, the authors must not upload the dataset to a stable, public repository. Interested, qualified researchers can access the data by requesting the research review committee of college of health sciences, Alemayehu Molla (alexmolla09@gmail.com) and the corresponding author, Defaru Desalegn (defdesalegn2007@gmail.com).