Abstract

The etherolytic cleavage of phenoxyalkanoic acids in various bacteria is catalyzed by an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase. In this reaction, the electron acceptor is oxidatively decarboxylated to succinate, whereas the proper substrate is cleaved by forming the oxidized alkanoic acid and the phenolic intermediate. The necessity of regenerating α-ketoglutarate and the consequences for the overall metabolism were investigated in a theoretical study. It was found that the dioxygenase mechanism is accompanied by a significant loss of carbon amounting to up to 62.5% in the assimilatory branch, thus defining the upper limit of carbon conversion efficiency. This loss in carbon is almost compensated for in comparison to a monooxygenase-catalyzed initial step when the dissimilatory efforts of the entire metabolism are included: the yield coefficients become similar. The α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase mechanism has more drastic consequences for microorganisms which are restricted in their metabolism to the first step of phenoxyalkanoate degradation by excreting the phenolic intermediate as a dead-end product. In the case of phenoxyacetate derivatives, the cleavage reaction would quickly cease due to the exhaustion of α-ketoglutarate and no growth would be possible. With the cleavage products of phenoxypropionate and phenoxybutyrate herbicides, i.e., pyruvate and succinate(semialdehyde), respectively, as the possible products, the regeneration of α-ketoglutarate will be guaranteed for stoichiometric reasons. However, the maintenance of the cleavage reaction ought to be restricted due to physiological factors owing to the involvement of other metabolic reactions in the pool of metabolites. These effects are discussed in terms of a putative recalcitrance of these compounds.

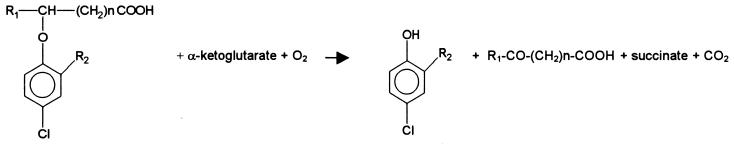

The metabolism of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate (2,4-D) has been well described for both the enzymatic steps (9) and their genetic basis (20, 23) as studied, for example, with Ralstonia eutropha (Alcaligenes eutrophus) JMP 134(pJP4). Although the first enzymatic step in this strain, encoded by the gene tfdA, was previously thought to be carried out by a monooxygenase-type reaction, it has since been shown to be catalyzed by an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase: oxidative decarboxylation of this electron acceptor results in the formation of succinate, whereas 2,4-D is oxidatively cleaved to 2,4-dichlorophenol (DCP) and glyoxylate (7). TfdA-like activities for the degradation of phenoxyalkanoates are widespread in proteobacteria of the β-subgroup (8, 26, 28); often harbored on plasmids (5), they have also been found on the chromosome (10, 24). In addition, however, 2,4-D-utilizing bacteria have been isolated in which the tfdA sequence could not be identified (10, 11, 14) by applying the primers from the conserved region of this gene (28). Although this does not necessarily contradict the enzyme functioning according to the above-mentioned mechanism, the monooxygenase-catalyzed cleavage of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetate was demonstrated in the case of Burkholderia cepacia AC 1100 (30). In addition to phenoxyacetates, cleavage by an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase has also been described for other phenoxyalkanoates. In the case of Sphingomonas herbicidovorans (19, 31), Rhodoferax sp. strain P230 (6), and Comamonas acidovorans MC1 (18), this has been shown for the degradation of phenoxypropionates such as (RS)-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)propionate (2,4-DP). The general equation for this oxidative etherolytic step is presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of oxidative etherolytic step of phenoxyalkanoates. R1 = H or CH3; R2 = Cl or CH3; n = 0 or 2 in respective combinations for the usual herbicides.

The conversion of phenoxyalkanoic acids via an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase thus plays an important role in the degradation of various herbicides. The initiation of degradation via this step requires α-ketoglutarate for continual substrate utilization. The consequences for substrate consumption and growth are investigated here in a theoretical study. Emphasis is placed on strains which only exhibit etherolytic activities by forming the phenolic intermediate as a dead-end product. Such strains are known (cf. references 15 and 27). The oxidized alkanoic acids are the only sources in these cases for both regeneration of the electron acceptor from succinate and growth. The efficiencies and limits of carbon conversion under these conditions are calculated and compared to the productive degradation of (chlorinated) phenolic compounds as described elsewhere (16).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The calculations were performed on the basis of the YATP concept (1, 22), taking into account a biomass synthesis efficiency of 10.5 g of bacterial dry mass/mol of ATP (3). Biomass synthesis was assumed to start from a central carbon precursor (29), which is considered to be 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA). Consequently, primary assimilatory pathways were formulated up to the formation of this metabolite. The average biomass “molecule” was taken as C4H8O2N1. Energy equivalents were synthesized with an efficiency of (P/O) ATP from NAD(P)H and with (P/O − 1) ATP from FADH2 (for further details, see references 2 and 3).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Complete degradation.

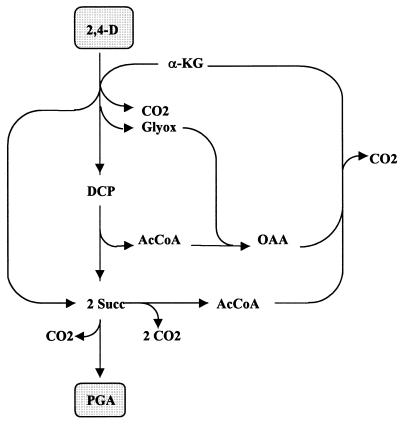

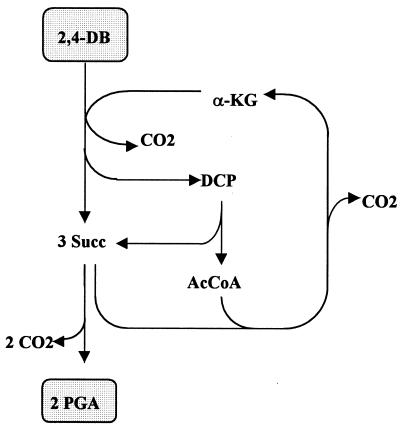

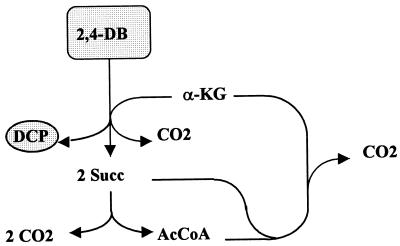

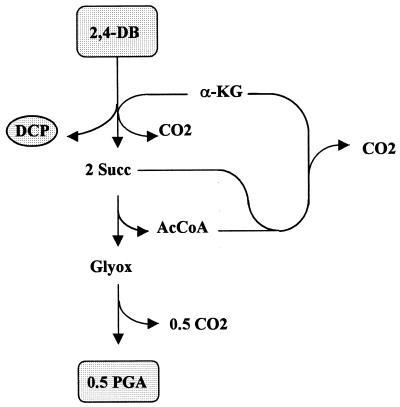

The balances of carbon metabolism, including primary assimilation, carbon precursor, and the biomass synthesis of various phenoxyalkanoic acids, taking into account the α-ketoglutarate-dependent mechanism of cleavage of the ether bond of the substrates, are listed in Tables 1 to 3. The degradation of 2,4-D by a monooxygenase-based type of reaction is shown for comparison (for other phenoxyalkanoates, see reference 15). Accordingly, assimilation of 2,4-D via α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase has pronounced effects on carbon assimilation. In the primary assimilatory route, as much as 50% of carbon was lost; 1 CO2 resulted from the cleavage of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), and three more were derived from the regeneration of the acceptor via glyxoylate (Glyox) and citrate cycle (Fig. 2). A further CO2 was liberated on the way to the precursor synthesis, meaning that a total of 62.5% of the carbon of the substrate appeared as CO2 in the assimilatory branch and only 37.5% remained for biomass synthesis (Fig. 2 and Table 4). By contrast, in the case of assimilation via a monooxygenase, 75% of the carbon was available for assimilatory purposes. 4-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)butyrate (2,4-DB) (Fig. 3) and 2,4-DP assimilated via an α-ketoglutarate-dependent mechanism also resulted in a loss of carbon, although the relative amounts were lower and reached 33 to 40% after the synthesis of PGA (Table 4). In comparison, a monooxygenase-catalyzed initial step of cleavage would preserve 75 to 83% of the carbon up to this metabolite. Since no further loss of carbon was taken into account in biomass synthesis (3), the carbon conversion efficiency in the precursor synthesis corresponds to the maximum carbon conversion efficiency which can possibly be attained on these substrates (Table 4). The increase in oxidative decarboxylation is accompanied by a rise in the formation of energy equivalents (Table 2), reducing the portion of substrate dissimilated only for the purposes of energy generation. This contrasts with the pattern of a monooxygenase-mediated substrate cleavage, which is characterized by the pronounced expenditure of energy equivalents in the primary assimilation and precursor synthesis, increasing the dissimilatory portion of the substrate (Tables 1 and 2), which is satisfied by increased dissimilation. In an overall balance of the mass and energy flows via the assimilatory and the dissimilatory routes, the yield coefficients consequently became similar. The figures are lower by only 2 to 13% in the case of the α-ketoglutarate-dependent version in comparison to a monooxygenase-catalyzed reaction (16). The liberation of HCl was not shown in the balance equations.

TABLE 1.

Balance equations of primary assimilation pathways of phenoxyalkanoate herbicides

| Reaction typea | End productsb |

|---|---|

| Monooxygenase type reaction (TfdA) | |

| 2,4-D + 4 NADH | 1 Succ + 1 AcCoA + 1 Glyox |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), complete degradation | |

| 2,4-D | 1 Succ + 4 CO2 + 1 NADH + 1 FADH2 |

| 2,4-DP + 1 NADH | 1 Succ + 1 Pyr + 2 CO2 + 1 FADH2 |

| 2,4-DB | 2 Succ + 2 CO2 + 1 FADH2 |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), incomplete degradation | |

| 2,4-DPPDH | 3 CO2 + 3 NADH + 1 FADH2 + [DCP]c |

| 2,4-DPPC/ML + 1 ATP | 1 Glyox + 1 CO2 + 1 NADH + [DCP]c |

| 2,4-DBME | 4 CO2 + 5 NADH + 2 FADH2 + [DCP]c |

| 2,4-DBML | 1 Glyox + 2 CO2 + 3 NADH + 2 FADH2 + [DCP]c |

| 2,4-DBME/ML | 0.5 Glyox + 3 CO2 + 4 NADH + 2 FADH2 + [DCP]c |

Superscripts: PDH, regeneration of α-KG via pyruvate dehydrogenase; PC/ML, regeneration of α-KG via pyruvate carboxylase and malate thiokinase–malyl-CoA lyase; ME, regeneration of α-KG via malic enzyme; ML, regeneration of α-KG via malate thiokinase–malyl-CoA lyase; ME/ML, regeneration of α-KG via ME and ML (50% each).

Pyr, pyruvate; AcCoA, acetyl-CoA.

Dead-end product.

TABLE 3.

Balance equations of assimilatory biomass synthesisa

| Reaction type | End products |

|---|---|

| Monooxygenase type reaction (TfdA) | |

| 2 (2,4-D) + 3 NH3 + 32.2 ATP + 10.5 [H2] | 3 BTS + 4 CO2 + 3 FADH2 |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), complete degradation | |

| 4 (2,4-D) + 3 NH3 + 29.2 ATP | 3 BTS + 20 CO2 + 2.5 NADH + 8 FADH2 |

| 2 (2,4-DP) + 3 NH3 + 33.2 ATP + 5.5 [H2] | 3 BTS + 6 CO2 + 4 FADH2 |

| 2 (2,4-DB) + 3 NH3 + 29.2 ATP + 1.5 [H2] | 3 BTS + 8 CO2 + 6 FADH2 |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), incomplete degradation | |

| 8 (2,4-DP) + 3 NH3 + 41.2 ATP + 1.5 [H2] | 3 BTS + 12 CO2 + 8 [DCP] |

| 8 (2,4)-DB)ML + 3 NH3 + 33.2 ATP | 3 BTS + 20 CO2 + 14.5 NADH + 16 FADH2 + 8 [DCP] |

| 16 (2,4-DB)ME/ML + 3 NH3 + 33.2 ATP | 3 BTS + 52 CO2 + 54.5 NADH + 32 FADH2 + 16 [DCP] |

Terms and superscripts are as defined in Table 1. BTS, biomass “molecule.”

FIG. 2.

Scheme of the synthesis of PGA during complete degradation of 2,4-D by including the regeneration of α-KG. Abbreviations: AcCoA, acetyl-CoA; OAA, oxaloacetic acid.

TABLE 4.

Carbon conversion efficiency (CCE) with monooxygenase (M)- and dioxygenase (α-KG)-type reactionsa

| Degradation type | CCE

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary assimilation | Precursor synthesis | Maximum | |

| Complete degradation | |||

| 2,4-D (M) | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| 2,4-D (α-KG) | 0.5 | 0.375 | 0.375 |

| 2,4-DP (M) | 1 | 0.833 | 0.833 |

| 2,4-DP (α-KG) | 0.778 | 0.667 | 0.667 |

| 2,4-DB (M) | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| 2,4-DB (α-KG) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Incomplete degradation (via α-KG) | |||

| 2,4-DP (C3)PDH | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2,4-DP (C3)ML | 0.667 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 2,4-DB (C4)ME | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2,4-DB (C4)ML | 0.5 | 0.375 | 0.375 |

| 2,4-DB (C4)ME/ML | 0.25 | 0.188 | 0.188 |

CCE with incomplete degradation refers to the alkanoic acid moiety. Superscripts are as defined in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

Scheme of the synthesis of PGA during complete degradation of 2,4-DB by including the regeneration of β-KG. Abbreviation: AcCoA, acetyl-CoA.

TABLE 2.

Synthesis of the biomass precursor (PGA)a

| Reaction type | End products |

|---|---|

| Monooxygenase type reaction (TfdA) | |

| 0.5 (2,4-D) + 0.75 ATP + 1.25 [H2] | 1 PGA + 1 CO2 + 1 FADH2 |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), complete degradation | |

| 2,4-D | 1 PGA + 5 CO2 + 2 NADH + 2 FADH2 |

| 0.5 2,4-DP + 1 ATP | 1 PGA + 1.5 CO2 + 1 FADH2 |

| 0.5 2,4-DB | 1 PGA + 2 CO2 + 1 NADH + 1.5 FADH2 |

| α-KG-dependent dioxygenase (TfdA), incomplete degradation | |

| 2 2,4-DPPDH + 3 ATP | 1 PGA + 3 CO2 + 1 NADH + 2 [DCP] |

| 2 2,4-DBML + 1 ATP | 1 PGA + 5 CO2 + 5 NADH + 4 FADH2 + 2 [DCP] |

| 4 2,4-DBME/ML + 1 ATP | 1 PGA + 13 CO2 + 15 NADH + 8 FADH2 + 4 [DCP] |

Terms and superscripts are as defined in Table 1.

Incomplete degradation.

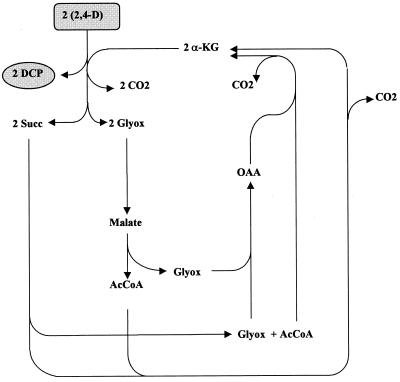

Microbial strains which are characterized by incomplete metabolism for herbicide degradation, i.e., which harbor cleaving activity (TfdA or TfdA analogs) but lack at least TfdB ([chloro]phenolhydroxylase) are faced with more drastic consequences. The phenolic intermediate, e.g., 2,4-dichlorophenol, which via the formation of succinate (Succ) and acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) would otherwise be a potential source for the regeneration of α-ketoglutarate (Fig. 2 and 3), cannot be metabolized, i.e., it remains dead-end product. Strains of the case considered only dispose of glyoxylate (phenoxyacetates), pyruvate (phenoxypropionates), or succinate semialdehyde (putatively from phenoxybutyrates), in addition to succinate resulting from the cleavage of α-ketoglutarate, for the regeneration of this acceptor and as a source of carbon and energy for growth. This strongly restricts metabolic flexibility, as can be seen in Table 5. In the case of 2,4-D, the regeneration of α-ketoglutarate from succinate and glyoxylate, most likely via glyoxylate carboligase, is only possible at all if the loss of carbon in this step is compensated for by tapping additional carbon via the carboxylation of C3 compounds (Fig. 4). Regeneration via this route includes the cleavage of malate resulting in the formation of acetyl-CoA and glyoxylate, which could be catalyzed by malate thiokinase–malyl-CoA lyase. From a stoichiometric point of view, the cleavage of 2,4-D could thus at best be maintained, assuming that carboxylation reactions of C3 compounds work adequately. From a physiological point of view, quantitative regeneration is rather improbable since other reactions make use of the pool of these intermediates and thus waste carbon by forming CO2. Under no circumstances, however, will growth be possible under these conditions. 2,4-D would prove inert despite the presence of TfdA.

TABLE 5.

Carbon balance after regeneration of α-KG in the cases of incomplete degradation of herbicides (with DCP as dead-end product)a

| Substrate | Carbon balance:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without carboxylation | With carboxylationb | |

| 2,4-D | No regeneration | 2 CO2 |

| 2,4-DPPDH | No relevance | 3 CO2 |

| 2,4-DPML | 3 CO2 | 1 Glyox + 1 CO2 |

| 2,4-DBML | 1 Glyox + 2 CO2 | No relevance |

| 2,4-DBME | 4 CO2 | No relevance |

Terms and abbreviations are as defined in Table 1.

Via pyruvate carboxylase.

FIG. 4.

Carbon flow during incomplete degradation of 2,4-D by forming DCP as a dead-end product. Abbreviations: AcCoA, acetyl CoA; OAA, oxaloacetic acid.

In the case of phenoxypropionates and phenoxybutyrates, the regeneration of α-ketoglutarate would be more likely from metabolic viewpoints: in the first case, for example, via pyruvate dehydrogenase and citric acid cycle (not shown) and in the second case, for instance, via malic enzyme, pyruvate dehydrogenase, and citric acid cycle (Fig. 5). α-Ketoglutarate could be adequately regenerated and, due to stoichiometric balances, the etherolytic cleavage of substrate could be maintained (Table 5). Once again, however, this is subject to restriction due to physiological aspects in view of the side reactions discussed. Carbon was quantitatively lost as CO2 under these conditions, and growth was not possible (Table 5). As a consequence, however, a huge amount of reduction equivalents was produced, creating some excess energy situations in the various pathways (not shown). Avoiding steps of extensive decarboxylation in the regeneration of the acceptor and, moreover, taking into account the carboxylation of pyruvate (Pyr) would result in the relaxation of the limitations regarding the availability of metabolites (see Fig. 6 for 2,4-DB). From a stoichiometric angle, the net synthesis of glyxoylate would even be possible from both phenoxypropionates and phenoxybutyrates (Table 5). This should therefore enable biomass synthesis according to the balance equations shown in Tables 1 to 3 and with efficiencies indicated by the figures in Table 4.

FIG. 5.

Carbon flow during incomplete degradation of 2,4-DB by forming DCP as a dead-end product (malic enzyme [C3-type] version). Abbreviations: AcCoA, acetyl-CoA.

FIG. 6.

Carbon flow during incomplete degradation of 2,4-DB by forming DCP as a dead-end product (malate thiokinase–malyl-CoA [C4-type]). Abbreviation: AcCoA, acetyl-CoA.

Examples.

That these restrictions indeed occur became evident from various examples. For instance, this effect can be unequivocally attributed to a derivative of the strain A. eutrophus (R. eutropha) JMP 228, which has been described as only exhibiting TfdA activity but did not further metabolize the chlorophenolic intermediates (27). It became apparent from the data presented here that cleavage of 2,4-D proceeded only as long as pyruvate was present in the growth medium; after pyruvate exhaustion, 2,4-D did not undergo further degradation. Other indications of a mechanism as proposed here were obtained from phenomena observed with noninduced cells of Rhodoferax sp. strain P230 (6) and Comamomas acidovorans MC1 (18). These strains exhibit α-ketoglutarate-dependent activities for the degradation both of the chiral phenoxypropionate herbicides dichlorprop (2,4-DP) and mecoprop [(RS)-2-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)propionate] and of phenoxyacetate herbicides 2,4-D and 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxyacetate. The initial cleavage reaction was constitutively expressed with respect to the R and S enantiomers of 2,4-DP in the case of strain MC1. Incubation in the presence of streptomycin resulted in a partial to complete degradation of the enantiomers with the pure and the racemic substrates. By contrast, 2,4-D remained almost unutilized under these conditions. This was, however, not caused by an enzymatic deficit. The application of an external (auxiliary) source of carbon, e.g., yeast extract, α-ketoglutarate, fructose, or lactate, resulted in the immediate degradation of these compounds accompanied by the liberation of DCP in approximately equimolar concentrations, a finding which is indicative of a shortage of metabolites required for the regeneration of α-ketoglutarate. Similar effects were observed with Rhodoferax sp. strain P230 with respect to the R enantiomer. Such metabolic background is also discussed in terms of the properties of strains of Aureobacterium sp. and Rhodococcus erythropolis which were only able to cleave phenoxybutyrate herbicides but metabolized the resulting chlorophenolic intermediates either very slowly (Rhodococcus) or not at all (Aureobacterium) (15). It was found that these strains could not be continuously cultivated on 2,4-DB, even in the presence of a second strain productively eliminating the toxic compound DCP (Ochrobactrum anthropi K2-14 [17] ) (H. Mertingk, personal communication), since the complete loss of carbon from C4 moieties can be easily explained. However, since the enzymatic mechanism of this cleavage reaction in these strains has not yet been elucidated (activity is completely lost after the disintegration of the cells), this lack of growth on these substrates cannot be unambiguously attributed to a mechanism as presently suggested. It should be mentioned in this context that the application of primers derived from the conserved region of the tfdA gene (28) did not result in respective amplification products in PCR (S. Kleinsteuber and D. Hoffmann, personal communication).

Conclusion.

The mechanisms discussed here might be responsible for an apparent recalcitrance of phenoxyalkanoic acid herbicides. This especially holds for bacterial consortia in which the essential degradative steps were associated with different strains. The latter was shown in a global survey on 2,4-D degrading activity to apply to most biotopes (25) and has most often been found to be the case with phenoxypropionate herbicides as well (12, 13, 21). To conclude, these results demonstrate that any evidence of nondegradative potentials in given biotopes and under respective assay conditions need not necessarily be an indication of enzymatic deficits but may well be due to general metabolic reasons.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babel W, Brinkmann U, Müller R H. The auxiliary substrate concept—an approach for overcoming limits in microbial performances. Acta Biotechnol. 1993;13:211–249. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babel W, Müller R H. Mixed substrate utilization in microorganisms: biochemical aspects and energetics. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babel W, Müller R H. Correlation between cell composition and carbon conversion efficiency in microbial growth: a theoretical study. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1985;22:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauchop T, Elsden S R. The growth of microorganisms in relation to their energy supply. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;23:457–469. doi: 10.1099/00221287-23-3-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Don R H, Pemberton J M. Properties of six pesticide degrading plasmids isolated from Alcaligenes paradoxus and Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:681–686. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.681-686.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrig A, Müller R H, Babel W. Isolation of phenoxy herbicide-degrading Rhodoferax species from contaminated building material. Acta Biotechnol. 1997;17:351–356. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukumori F, Hausinger R P. Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP 134 “2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate monooxygenase” is an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2083–2086. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.2083-2086.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulthorpe R R, McGowan C, Maltseva O V, Holben W E, Tiedje J M. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading bacteria contain mosaics of catabolic genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3274–3281. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3274-3281.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Häggblom M M. Microbial breakdown of halogenated aromatic pesticides and related compounds. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:29–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ka J O, Holben W E, Tiedje J M. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D)-degrading bacteria isolated from 2,4-D-treated field soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1106–1115. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1106-1115.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamagata Y, Fulthorpe R R, Tamura K, Takami H, Forney L J, Tiedje J M. Pristine environments harbor a new group of oligotrophic 2,4-dichlorophenocyacetic acid-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2266–2272. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2266-2272.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly M P, Heniken M R, Touvinen O H. Dechlorination and the spectral changes associated with bacterial degradation of 2-(2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxy)propionic acid. J Ind Microbiol. 1991;7:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilpi S. Degradation of some phenoxy acid herbicides by mixed cultures of bacteria isolated from soil treated with 2-(2-methyl-4-chloro)phenoxypropionic acid. Microb Ecol. 1980;6:261–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02010391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinsteuber S, Hoffmann D, Müller R H, Babel W. Detection of chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase genes in proteobacteria by PCR and gene probes. Acta Biotechnol. 1998;18:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mertingk H, Müller R H, Babel W. Etherolytic cleavage of 4-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)butyric acid and 4-(4-chloro-2methylphenoxy)butyric acid by species of Rhodococcus and Aureobacterium isolated from an alkaline environment. J Basic Microbiol. 1998;38:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller R H, Babel W. Phenol and its derivatives as heterotrophic substrates for microbial growth—an energetic comparison. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;42:446–451. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller R H, Jorks S, Kleinsteuber S, Babel W. Degradation of various chlorophenols under alkaline conditions by Gram-negative bacteria closely related to Ochrobacterum anthropi. J Basic Microbiol. 1998;38:269–281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-4028(199809)38:4<269::aid-jobm269>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller, R. H., S. Jorks, S. Kleinsteuber, and W. Babel. Comamonas acidovorans MC1: a new isolate capable of degrading the chiral herbicides dichlorprop and mecoprop and the herbicides 2,4-D and MCPA. Microbiol. Res., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Nickel K, Suter M J-F, Kohler H-P E. Involvement of two α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases in enatioselective degradation of (R)- and (S)-mecoprop by Sphingomonas herbicidovorans MH. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6674–6679. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6674-6679.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkins E J, Gordon M P, Caceres O, Lurquin P F. Organization and sequence analysis of the 2,4-dichlorophenol hydroxylase and dichlorophenol oxidative operons in plasmid pJP4. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2351–2359. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2351-2359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfarl C, Dietzelmüller G, Loidl M, Streichsbier F. Microbial degradation of xenobiotic compounds in soil columns. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;73:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stouthamer A H. A theoretical study on the amount of ATP required for the synthesis of microbial cell material. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1973;39:545–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02578899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streber W R, Timmis K N, Zenk M H. Analysis, cloning, and high-level expression of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate monooxygenase gene tfdA of Alcaligenes eutrophus JPM 134. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2950–2955. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.2950-2955.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suwa Y, Wright A D, Fukimori F, Nummy K A, Hausinger R P, Holben W E, Forney L J. Characterization of a chomosomally encoded 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid/α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase from Burkholderia sp. strain RASC. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2464–2469. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2464-2469.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiedje J M, Fulthorpe R, Kamagata Y, McGowan C, Rhodes A, Takami H. What is the global pattern of chloroaromatic degrading microbial populations? In: Horikoshi K, Fukuda M, Kudo T, editors. Microbial diversity and genetics of biodegradation. S. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1997. pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Top E M, Holben W E, Forney L J. Characterization of diverse 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degradative plasmids isolated from soil by complementation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1691–1698. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1691-1698.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Top E M, Maltseva O V, Forney L J. Capture of a catabolic plasmid that encodes only 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid:α-ketoglutaric acid dioxygenase (TfdA) by genetic complementation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2470–2476. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2470-2476.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallaeys T, Fulthorpe R R, Wright A M, Soulas G. The metabolic pathway of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation involves different families of tfdA and tfdB genes according to PCR-RFLP analysis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;20:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Dijken J P, Harder W. Growth yields of microorganisms on methanol and methane: a theoretical study. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1975;17:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xun L, Wagnon K B. Purification and properties of component B of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetate oxygenase from Burkholderia cepacia AC1100. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3499–3502. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3499-3502.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zipper C, Nickel K, Angst W, Kohler H P E. Complete microbial degradation of both enantiomers of the chiral herbicide mecoprop [(RS)-2-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)propionic acid] in an enantioselective manner by Sphingomonas herbicidovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4318–4322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4318-4322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]