Abstract

Secreted yields of foreign proteins may be enhanced in filamentous fungi through the use of translational fusions in which the target protein is fused to an endogenous secreted carrier protein. The fused proteins are usually separated in vivo by cleavage of an engineered Kex2 endoprotease recognition site at the fusion junction. We have cloned the kexin-encoding gene of Aspergillus niger (kexB). We constructed strains that either overexpressed KexB or lacked a functional kexB gene. Kexin-specific activity doubled in membrane-protein fractions of the strain overexpressing KexB. In contrast, no kexin-specific activity was detected in the similar protein fractions of the kexB disruptant. Expression in this loss-of-function strain of a glucoamylase human interleukin-6 fusion protein with an engineered Kex2 dibasic cleavage site at the fusion junction resulted in secretion of unprocessed fusion protein. The results show that KexB is the endoproteolytic proprotein processing enzyme responsible for the processing of (engineered) dibasic cleavage sites in target proteins that are transported through the secretion pathway of A. niger.

Many secreted eukaryotic proteins contain a signal peptide and an adjacent propeptide at the amino terminus. The signal peptide specifies a sequence for translocation over the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and is normally removed in the lumen during translocation by a signal peptidase. Propeptides have been implicated in correct folding and in subcellular sorting of proteases. They also often function as (auto)inhibitors. The processing of most of these propeptides occurs at either a monobasic or a dibasic cleavage site (2). Propeptides, which are cleaved after a Lys-Arg or Arg-Arg basic doublet at the P2 and P1 positions (the nomenclature used is according to reference 27), are specifically recognized and processed in the trans-Golgi network by the kexin family of proteases, a subfamily of the subtilase family of proteases (29). The kexin family consists of the yeast Kex2-like proteases (EC 3.4.21.61), the mammalian prohormone convertases (PCs) (EC 3.4.21.93 and EC 3.4.21.94), and the furins (EC 3.4.21.75). All members of the kexin subfamily are calcium-dependent, neutral, serine proteases that are activated by the removal of the amino-terminal propeptide at a kexin-specific (auto)processing site. The active proteases all contain two additional domains, a subtilisin-like domain containing the catalytic triad and a conserved P or Homo B domain of approximately 150 residues. The P domain, which is absent in other subtilases, is essential for the catalytic activity (21) and the stability of the protein (18). Kex2-like yeast proteases, furins, and some of the PCs also have a single transmembrane domain (20, 21, 28). In its cytoplasmic tail, yeast Kex2 contains a Golgi retrieval signal, necessary to remain in the trans-Golgi network (33).

In Aspergillus spp., kexin-like activity has been detected through the cleavage of artificial fusion proteins. Here, artificial fusion proteins are used for the production of foreign proteins, exploiting the efficient production, sorting, and processing of endogenous proteins (reviewed in reference 13). In these constructs, a consensus Kex2 cleavage site often separates the foreign protein from the endogenous protein. Studies with such fusion proteins in Aspergillus niger showed that amino acid residues directly adjacent to the cleavage site can affect correct processing of an engineered Kex2 site (30).

Examples of physiological substrates for an A. niger kexin-like endoprotease are the endopolygalacturonase (Pga) family of proteins (6, 7, 8, 23). They all contain a dibasic cleavage site at the carboxy-terminal end of their amino-terminal propeptide, except for PgaII, which has a single arginine residue preceding the cleavage site (6).

Our objectives in this study were (i) to show that A. niger expresses a Kex2-like dibasic endoprotease and (ii) to demonstrate that this endoprotease is responsible for the cleavage of a fusion protein with an engineered Kex-2 site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, transformation, and DNA and RNA techniques.

The A. niger strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. NW219, NW249, and NW266 were used for the transformation of A. niger, as previously described (17). Strain NW266 was constructed by the transformation of NW249 with pIM4003. (The construction of the pIM plasmids is described below.) MCK-5 was constructed by the cotransformation of NW249 with pGW635, containing the A. niger pyrA gene, and pIM4002. MCGI and MCGIΔ were constructed by the cotransformation of, respectively, NW219 and NW266 with pGW635 and pFGPDGLAHIL6 (9).

TABLE 1.

A. niger strains used in this studya

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| N402 | cspA1 | 3 |

| NW219 | pyrA6 leuA1 nicA1 cspA1 | 17 |

| NW249 | ΔargB pyrA6 nicA1 leuA1 cspA1 | P. J. I. van de Vondervoort and Y. Muller, unpublished data |

| MCK-5 | NW249+ (pyrA) (kexB)15–25 | This study |

| NW266 | NW249 (argB::ΔkexB) | This study |

| MCGI | NW219 (pyrA) (PgpdA-glaA-KEX2-hIL6)12–15 | This study |

| MCGIΔ | NW266 (pyrA) (PgpdA-glaA-KEX2-hIL6)10–12 | This study |

Genes introduced by transformation are indicated in parentheses. Estimated copy numbers of relevant genes were determined by Southern analysis and are indicated in subscript. KEX2 symbolizes an engineered dibasic processing site.

Escherichia coli LE392 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used for phage amplification and λ DNA isolation. E. coli DH5α was used for plasmid transformation and propagation. Standard DNA manipulations were carried out essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (26). Plasmid pUC19 or phagemid pBluescript SK(+) was used as a cloning vector for genomic DNA fragments. Cloned hybridizing fragments and cDNA clones were sequenced with a Thermo Sequenase fluorescent-labelled primer cycle sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and an ALF automated sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

For Southern analysis, total DNA from Aspergillus strains was isolated as previously described (9a). Hybridizations were done in standard hybridization buffer (SHB) (6× SSC, 5× Denhardt's solution (27), 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 100 μg of denatured herring sperm DNA ml−1). 1× SSC contains 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate. Washing was performed at 65°C to a final stringency of 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS. For nonstringent conditions, hybridization was executed at 56°C and washing was done twice in 4× SSC and 0.1% SDS at the same temperature.

For Northern analysis, strains were grown for 17 h in minimal medium (24) supplemented with 1% glucose as a carbon source and 0.5% yeast extract in 50-ml cultures in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks in an Innova incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Inc., Edison, N.J.) at 250 rpm at 30°C. Mycelium was harvested by filtration over a nylon membrane (mesh size, 100 μm) and the mycelium was ground with a Braun II dismembrator (B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany). Total RNA was isolated from mycelium samples with Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically and equal amounts of RNA were denatured with glyoxal by standard techniques (26) and separated on a 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gel. RNA blots were hybridized at 42°C in SHB to which 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate and 50% (vol/vol) formamide were added. Washing was performed at 65°C to a final stringency of 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS. As a control, Northern blots were hybridized with A. niger ribosomal protein gene rpS28.

Cloning of kexB.

A kexB PCR product was generated by PCR on genomic DNA of A. niger N400 with two degenerate primers: the forward primer was 5′-CAYGGNACIMGITGYGCNGG-3′, encoding HGTRCAGE, and the reverse primer was 5′-TAYTGNACRTCNCKCCA-3′, encoding WRDVQY (standard IUB-IUPAC symbols are used to indicate the nucleotide mixes; I indicates inosine). A standard program of 30 thermal cycles was composed of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 48°C, and 1 min at 72°C, preceded by an incubation of 4 min at 95°C and followed by an incubation of 5 min at 72°C. The amplified fragment was cloned in vector pGEM-T (Promega) and identified by sequencing. Genomic sequences of the kexB gene were obtained by screening a λ EMBL4 genomic library of A. niger N402 by standard methods (26), with the kexB PCR product as a probe. Four λ clones were isolated and from one of these positive phages, two SalI fragments of about 2 kb were subcloned in pUC19.

Plasmid construction.

The upstream and downstream kexB SalI fragments in pUC19 were each recloned in pBluescript SK(+) digested with SalI and XhoI. The resulting plasmids were selected for having the SalI sites upstream and downstream, respectively, of kexB ligated in the XhoI sites of the pBluescript vectors. Next, the downstream kexB fragment in pBluescript was ligated as a SalI-EcoRI fragment downstream of the upstream kexB fragment, yielding pIM4002 (see Fig. 2). For the construction of pIM4003, a 590-bp ClaI-SalI fragment was first removed from the open reading frame (ORF) of the upstream SalI fragment in pBluescript. The resulting plasmid was digested with HindIII and PstI, and the argB gene was inserted 3′ of the truncated kexB fragment. In the resulting plasmid, the kexB downstream fragment was inserted as a PstI-BamHI fragment yielding pIM4003 (see Fig. 3).

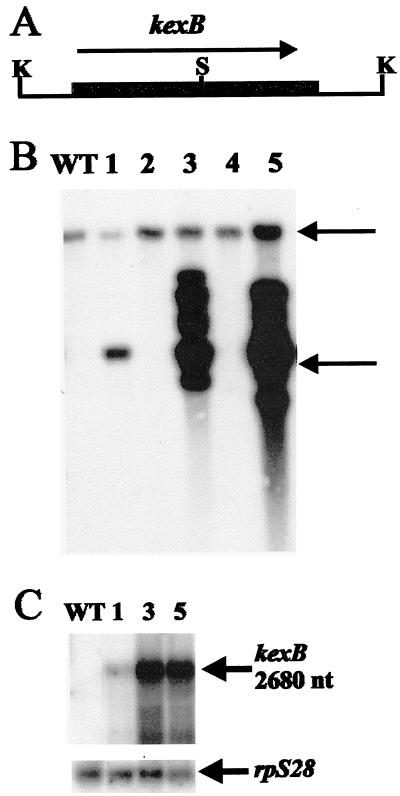

FIG. 2.

Molecular characterization of kexB multicopy strains. (A) Map of the insert of pIM4002 used for transformation. The SalI sites (S) in the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of kexB are replaced by KpnI (K) sites. (B) Southern analysis of kexB-overexpressing transformants. KpnI-digested genomic DNA of NW249 and of five transformants was analyzed. The 10-kb band of the endogenous gene and the 4-kb band originating from intact integrated copies of pIM4002 are indicated by arrows. Some scattered integration of pIM4002 is also observed. (C) Northern analysis of kexB expression in multicopy transformants. Transformant numbers are indicated above the lanes. In the lower panel, the membrane is rehybridized with ribosomal protein gene rpS28 to provide a loading control. WT, wild type.

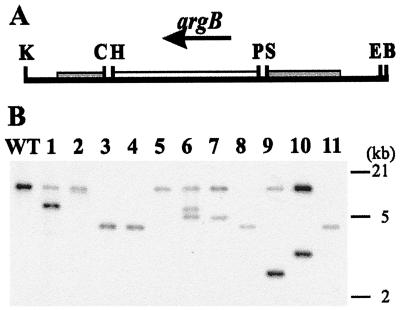

FIG. 3.

Molecular characterization of kexB disruption strains. (A) Map of the insert of pIM4003 used for transformation. A part of the kexB ORF substituted with the argB selection marker. The BamHI (B), ClaI (C), EcoRI (E), KpnI (K), HindIII (H), PstI (P), and SalI (S) used in the cloning strategy are indicated. (B) Southern analysis of arginine prototrophic transformants. PstI-digested genomic DNA of NW249 and of 11 transformants was hybridized with a SalI-EcoRI fragment of pIM4003. The endogenous kexB gene hybridizes as a 15-kb fragment (WT lane). A 4.4-kb fragment replaces this fragment if the argB gene replaces a part of the kexB coding region (lanes 3, 4, 8, and 11). Transformants (lanes 1, 6, 7, 9, and 10) show an ectopic pattern of integration. Transformants (lanes 2 and 5) have integrated only a functional argB gene.

Nucleotide and protein sequence analyses.

Sequence analysis was performed with the sequence analysis software package PC/Gene (IntelliGenetics, Inc., Geneva, Switzerland). Public databases were searched with the BLAST search tools (1). Multiple alignment was done in CLUSTAL W (31). The SignalP program was used to identify the signal sequence for secretion (22). Putative transmembrane regions were identified with the SOSHUI program (14).

Isolation of KexB containing membrane-protein fractions.

Strains were grown and mycelium was treated as described for the Northern analysis. Ground mycelium (3 g [wet weight]) was extracted with 6 ml of 50 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.6) and 10 mM EDTA. The extract was clarified by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C) and the clarified supernatant was centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pelleted membrane-containing fraction was extracted with 5 ml of 50 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.6), 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, and 2% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate in 20% glycerol. The extract was clarified again by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C. The supernatant was stored at −20°C until use.

Kexin enzyme assay.

7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) and tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) methylcoumarinamide (MCA) derivatives were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 200 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.0), 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 100 μM MCA derivative (Table 2). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 0 to 4 h and the reactions were terminated by the addition of 1.8 ml of 125 mM ZnSO4 and 0.2 ml of saturated Ba(OH)2. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation for 3 min at 10,000 × g, and the amount of AMC liberated was measured with a Hitachi F4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer calibrated with known amounts of AMC (λex = 370 nm; λem = 445 nm). One unit was defined as 1 pmol of AMC released per min (12). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method as described by the manufacturer (Sigma Chemical Co.).

TABLE 2.

Relative efficiency of cleavage of peptidyl-MCA substratesa

| Peptide substrate

|

Relative activity (%) in strain

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5 | P4 | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | NW249 | MCK-5 | NW266 (ΔkexB) |

| Boc | Gly | Arg | Arg | MCA | 9 | 24 | 5 | |

| Boc | Gly | Lys | Arg | MCA | 34 | 81 | 9 | |

| Boc | Leu | Arg | Arg | MCA | 30 | 74 | 8 | |

| Boc | Leu | Lys | Arg | MCA | 100 | 220 | 17 | |

| Boc | Leu | Gly | Arg | MCA | 3 | 7 | 5 | |

| Boc | Gln | Arg | Arg | MCA | 71 | 180 | 14 | |

| Boc | Gln | Gly | Arg | MCA | 10 | 29 | 14 | |

| Boc | Glu | Lys | Lys | MCA | 2 | 5 | 3 | |

| Boc | Val | Pro | Arg | MCA | 29 | 50 | 7 | |

| Boc | Leu | Ser | Thr | Arg | MCA | 11 | 21 | 2 |

| Boc | Arg | Val | Arg | Arg | MCA | 68 | 130 | 7 |

The activity is expressed as a percentage of the activity obtained with the DSP fraction of the wild-type strain (NW249) on Boc-Leu-Lys-Arg-MCA (0.51 pmol of AMC liberated/μg of DSP). The concentrations of the DSP fractions of the wild-type strain, MCK-5, and NW266 were 1.33, 0.49, and 0.67 mg/ml respectively.

Western analysis of strains MCGI and MCGIΔ.

Shake flask cultures were used to express the PgpdA-glaA-hIL-6 fusion gene from strains MCGI and MCGIΔ, each harboring 10 to 15 copies of the construct (Table 1). Culture conditions were as described for Northern analysis except that xylose was used as a carbon source to suppress the endogenous glucoamylase gene. Culture fluid was concentrated by deoxycholate-trichloroacetic acid precipitation. Medium samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and standard protocols were used for the detection of recombinant human interleukin-6 fusion protein by Western analysis (26). Mouse monoclonal human interleukin-6 antibody (R & D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) was used for the detection. Recombinant human interleukin-6 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as a positive control.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data of the kexB gene has been submitted to the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank databases under accession no. Y18127.

RESULTS

Cloning of an A. niger kexin homologue.

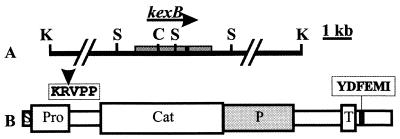

We designed degenerate primers based on amino acid sequences shared by several kexin proteases and amplified a 603-bp PCR product from A. niger genomic DNA. A genomic SalI fragment of approximately 2 kb hybridized with the probe. We recovered two SalI fragments of similar size from an A. niger genomic λ library. The fragments contained adjacent parts of the complete ORF of the gene we designated kexB (Fig. 1). The ORF encodes a protein of 844 amino acids interrupted by a putative 51-bp intron located 1,763 bp downstream of the start codon. We identified a partial 1-kb cDNA clone in a cDNA library of A. niger that confirmed that the intron was positioned correctly. The cDNA ended in a poly(A) tail 133 bp downstream of the inferred stop codon. Southern analysis performed under conditions of low stringency indicated that the kexB gene is a single copy gene.

FIG. 1.

Sequence characteristics of the A. niger kexB gene. (A) Partial restriction map of the kexB genomic region. The position of the ClaI (C), KpnI (K), and SalI (S) used in cloning strategies are indicated. The distance between the KpnI sites flanking the cloned region is approximately 10 kb. The ORF is indicated with a gray box and the arrow indicates the direction of transcription. The position of the single intron in kexB is indicated with a black box. (B) Putative domains of the KexB protease. The KexB amino acid sequence is indicated by an open box. The following domains could be distinguished: signal-sequence (S), prosequence (Pro), subtilisin-like domain (Cat), P domain (P), and transmembrane domain (T). The putative auto cleavage site (with arrowhead) and the putative Golgi retention signal are also indicated.

Analysis of the kexB ORF sequence.

The encoded protein is highly similar to the kexin subfamily of proteases and also shares significant similarity with several other subtilisins. The highest similarity was with the Kex2-like protease from the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica (10), yielding 42% overall identity.

As has been described for other kexin proteases, five putative domains were identified in the deduced amino acid sequence (Fig. 1). The first 19 amino acid residues of the ORF were identified by the signalP neural network (22) as a signal sequence for translocation over the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. The adjacent propeptide probably encompasses amino acids 20 to 129. At the carboxy-terminal end of this segment, there is a Lys-Arg dibasic (auto)cleavage site. Amino acids 190 to 435 contain a subtilisin-like domain. This domain has 53 to 62% identity with the same domains of the yeast Kex2-like proteases and contains the active site residues of the Asp, His, and Ser catalytic triad and a conserved Asn residue which stabilizes the oxyanion hole in the transitional state (5). The P domain (Fig. 1) is not found in other subtilase subfamilies and its presence therefore strongly suggests that we have indeed cloned a member of the kexin subfamily. There also is a putative single membrane-spanning domain. In the putative cytoplasmic tail, 15 amino acids downstream of the transmembrane domain, we found the peptide sequence YDFEMI. The underlined amino acids residues are identical to the late Golgi retention signal (consensus, YXFXXI) in the cytoplasmic tail of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protease (33).

In a multiple alignment, the A. niger KexB protease was compared to other proteases of the kexin subfamily of proteases and PepC (11) and PepD (15), two A. niger subtilases of the proteinase K subfamily (29). The alignment indicated that the A. niger endoprotease is more similar to the yeast-like kexin proteases than to the furins and PCs and is only weakly related to the A. niger PepC and PepD subtilases.

Characterization of kexB disruptants and overproducers.

We transformed strain NW249 (Table 2) with plasmid pIM4002 and identified three multicopy transformants with elevated expression of the kexB gene (Fig. 2).

We disrupted kexB by transformation with plasmid pIM4003. In this plasmid, a part of the subtilisin-like domain, including the Ser residue of the catalytic triad and the conserved Asn, was replaced by the argB gene of A. niger (Fig. 3). We identified four transformants in which the kexB gene was replaced by the nonfunctional gene and four other transformants in which the disrupted gene was integrated ectopically (Fig. 3). On agar plates, starting from single spores, the four kexB disruptants, but not the ectopic transformants, formed compact colonies with no sporulation at the edges. The hyphae of these strains also branched more often and the individual cell segments were shorter, resulting in a dense appearance of the mycelium. In liquid shake flask cultures, there was no clear difference in growth rate and the mycelium appeared much more like wild-type mycelium. No unusual phenotype was associated with the kexB multicopy transformants.

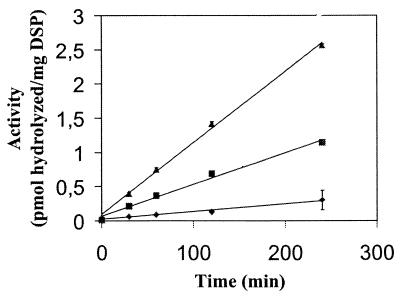

Characterization of KexB activity.

We measured the relative kexin activity of the detergent-solubilized membrane-protein fraction (DSP) for 4 h with Boc-L-K-R-MCA as a fluorogenic substrate in a wild-type strain (NW249), a kexB disruptant (NW266), and a kexB multicopy transformant (MCK-5) (Table 1). The DSP fraction of MCK-5 had more than twice as much hydrolyzing activity towards the MCA substrate as the DSP fraction from the wild-type strain. The DSP fraction of the kexB-disrupted strain had no significant hydrolyzing activity (Fig. 4). The amount of AMC liberated increased linearly with time if DSP fractions of NW249 or MCK-5 were used, indicating that under assay conditions the enzyme activity is stable.

FIG. 4.

Time dependence of hydrolysis of Boc-Leu-Lys-Arg-MCA by the DSP fractions of NW249 (■), MCK-5 (▴), and NW266 (⧫). The data represent the means of two independent experiments. Standard errors are indicated by bars or are within each symbol.

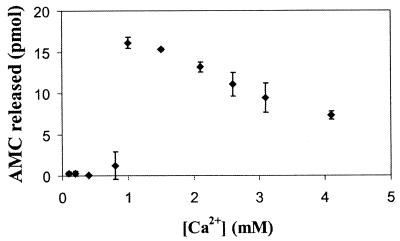

Kexin activity is strictly Ca2+ dependent (Fig. 5). Without Ca2+, no hydrolyzing activity towards the substrate was observed. Free Ca2+ concentration of 1 to 2 mM appears to be optimal for activity of the DSP extract.

FIG. 5.

Ca2+ dependency of KexB activity. Incubations were done for 4 h in 200 mM HEPES, 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0), and a varying Ca2+ concentration with 10 μl of DSP extract of NW249 (1.33 mg of protein/ml) and 100 μM Boc-L-K-R-MCA as a substrate. The data represent the means of two independent experiments. Bars indicate standard errors.

We tested several fluorogenic substrates to determine the substrate specificity of the A. niger kexin (Table 2). In all cases, a lysine residue at P2 performs better than an arginine residue. Similarly, a glutamine residue at P3 performs better than a leucine residue. A glycine residue at P3 is not preferred. Furthermore, a typical furin recognition site, the tetrapeptide Arg-Val-Arg-Arg (21) is also a good substrate for KexB. The tripeptide Glu-Lys-Lys and the tetrapeptide Leu-Ser-Thr-Arg are poor substrates for KexB. The membrane-protein fraction of the kexB-disrupted strain showed no significant activity towards any of the MCA substrates tested (Table 2).

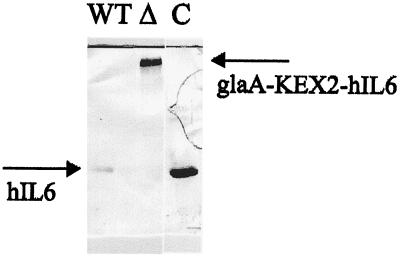

KexB cleavage of an engineered Kex2 site in a reporter construct.

Strains MCGI (wild type) and MCGIΔ (kexB disruptant) (Table 1) express a fusion gene encoding a glucoamylase–human interleukin-6 fusion protein separated by a Kex2 site at the fusion junction. Western analysis of the reporter showed that while the wild-type strain secretes glucoamylase and interleukin-6 separately, the kexB disruptant is unable to hydrolyze the Kex2 site at the fusion junction and therefore only secretes the intact fusion protein (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Western analysis of glucoamylase–human interleukin-6 processing. Medium samples (0.5 ml) of MCGI (wild type) (WT) and MCGIΔ (kexB disruptant) (Δ) were analyzed for the presence of unprocessed human interleukin-6 (glaA-KEX2-hIL6). The control lane (C) contains 0.5 μg of recombinant human interleukin-6 (hIL6).

DISCUSSION

We used a PCR approach to clone a kexin homologue in A. niger. Kexins have been cloned and characterized from yeasts and mammalian cells, and thus from an evolutionary perspective, the existence of such a function was predictable. The work done with polygalacturonases (6, 7, 8, 23) and with fusion proteins that use engineered Kex2 sites at the fusion junction (reviewed in reference 13) suggested that this function exists in A. niger. The kexB gene we cloned encodes a Kex2-like dibasic endoprotease that has significant similarity to expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of two other filamentous fungi. One EST (GenBank accession no. AA787123) originated from Aspergillus nidulans, and a translation from that EST has 64% identity with KexB. The other EST (GenBank accession no. AIO68899) was from the pyrenomycete Magnaporthe grisea, and a translation from that EST also showed 64% identity with KexB. These findings suggest that this endoprotease function is ubiquitously expressed in filamentous fungi.

Strain MCK-5 has more than 15 copies of the kexB gene, and a high level of overexpression of kexB in that strain was confirmed by Northern analysis. The relatively low increase in kexin activity in the DSP fraction of strain MCK-5 could be due to a regulatory mechanism operative at the posttranscriptional level. When the Kex2 protease was overproduced in the yeast S. cerevisiae, it was transported to the vacuole at an increased rate and degraded (33).

The kexB disruptant grows very poorly on agar plates and its hyphae have an unusual morphology. Under these circumstances, KexB function appears to be essential for normal growth. In shake flask cultures, however, the disruption of kexB has less severe consequences. Biomass is not reduced in liquid culture and there are no indications that secretion of the reporter is hampered in the kexB-disrupted strain. When strains with comparable copy numbers were used, the amount of glucoamylase produced as a separate protein in the control strain was comparable to the amount of fusion protein produced by the KexB disruptant (NW266).

The lack of processing of MCA derivatives by the DSP of the kexB disruptant proves that hydrolysis of the MCA derivatives in the membrane-protein fractions of the wild-type strain and the kexB multicopy strain depends on KexB. In vitro, the specificity of KexB is more comparable to that of the yeast Kex2 maturase (4) than it is to that of mammalian furin (21). However, in vitro Aspergillus KexB appears to process the furin-specific sequence Arg-Val-Arg-Arg better than yeast Kex2. Like Kex2, KexB does not process the tripeptide Glu-Lys-Lys. In yeast, the amino acid at the P4 position is important for the cleavage of a Lys-Lys dibasic cleavage site (25). If a phenylalanine residue is present at P4, then normal processing of the substrate results. In A. niger PgaI, a similar cleavage site (F-A-K-K) is processed in vivo (7).

The results from the in vitro experiments are consistent with the inability of the kexB disruptant to process the glucoamylase–interleukin-6 fusion protein with an engineered Kex2 site at the fusion junction. The yeast monobasic aspartyl protease Mkc7 can also hydrolyze a dibasic cleavage site (16) and monobasic cleavage is operative in A. niger (7). However, such compensation for the loss of kexin activity was not observed with this reporter. Clearly, our results identify the kexB gene as the kexin-encoding gene of A. niger.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Contreras for providing plasmid pFGPDGLAHIL6 and Y. Müller for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Dutch Technology Foundation (STW) grant WBI.4100.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker D, Shiau A K, Agard D A. The role of pro regions in protein folding. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:966–970. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos C J, Debets A J M, Swart K, Huybers A, Kobus G, Slakhorst S M. Genetic analysis and the construction of master strains for assignment of genes to six linkage groups in Aspergillus niger. Curr Genet. 1998;14:437–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00521266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner C, Fuller R S. Structural and enzymatic characterization of a purified prohormone-processing enzyme: secreted, soluble Kex2 protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:922–926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan P, Pantoliano M W, Quill S G, Hsiao H Y, Poulos T. Site-directed mutagenesis and the role of the oxyanion hole in subtilisin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3743–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bussink H J D, Kester H C M, Visser J. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence and expression of the gene encoding pre-pro-polygalacturonase II of Aspergillus niger. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81066-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bussink H J D, Brouwer K B, de Graaff L H, Kester H C M, Visser J. Identification and characterization of a second polygalacturonase gene of Aspergillus niger. Curr Genet. 1991;20:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00318519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussink H J D, Buxton F P, Fraaye B A, de Graaff L H, Visser J. The polygalacturonases of Aspergillus niger are encoded by a family of diverged genes. Eur J Biochem. 1992;208:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contreras R, Carrez D, Kinghorn J R, van den Hondel C A M J J, Fiers W. Efficient Kex2-like processing of a glucoamylase-interleukin-6 fusion protein by Aspergillus nidulans and secretion of mature interleukin-6. Bio/Technology. 1991;9:378–381. doi: 10.1038/nbt0491-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.de Graaff L, van den Broek H, Visser J. Isolation and expression of the Aspergillus nidulans pyruvate kinase gene. Curr Genet. 1988;13:315–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00424425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enderlin C S, Ogrydziak D M. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and functions of XPR6, which codes for a dibasic processing endoprotease from the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast. 1994;10:67–79. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederick G D, Rombouts P, Buxton F P. Cloning and characterization of pepC, a gene encoding a serine protease from Aspergillus niger. Gene. 1993;125:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90745-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller R S, Brake A, Thorner J. Yeast prohormone processing enzyme (Kex2 gene product) is a Ca2+-dependent serine protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1434–1438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouka R J, Punt P J, van den Hondel C A M J J. Efficient production of secreted proteins by Aspergillus: progress, limitations and prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002530050880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. SOSUI: classification and secondary structure prediction system for membrane proteins. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:378–379. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarai G, Buxton F P. Cloning and characterization of the pepD gene of Aspergillus niger which codes for a subtilisin-like protease. Gene. 1994;139:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komano H, Fuller R S. Shared functions in vivo of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl protease, Mkc7, and the proprotein processing protease Kex2 in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10752–10756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusters-van Someren M A, Harmsen J A M, Kester H C M, Visser J. Structure of the Aspergillus niger pelA gene and its expression in Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Genet. 1991;20:293–299. doi: 10.1007/BF00318518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipkind G M, Zhou A, Steiner D F. A model for the structure of the P domains in the subtilisin-like prohormone convertases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7310–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizuno K, Nakamura T, Ohshima T, Tanaka S, Matsuo H. Characterization of kex2-encoded endopeptidase from yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:305–311. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molloy S S, Bresnahan P A, Leppla S H, Klimpel K R, Thomas G. Human furin is a calcium-dependent serine endoprotease that recognizes the sequence Arg-X-X-Arg and efficiently cleaves anthrax toxin protective antigen. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16396–16402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama K. Furin: a mammalian subtilisin/Kex2p-like endoprotease involved in processing of a wide variety of precursor proteins. Biochem J. 1997;327:625–635. doi: 10.1042/bj3270625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pařenicová L, Benen J A E, Kester H C M, Visser J. pgaE encodes a fourth member of the endopolygalacturonase gene family from Aspergillus niger. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:72–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pontecorvo G, Roper J A, Hemmons L J, MacDonald K D, Bufton A W J. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–238. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockwell N C, Fuller R S. Interplay between S1 and S4 subsites in Kex2 protease: Kex2 exhibits dual specificity for the P4 side chain. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3386–3391. doi: 10.1021/bi972534r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schechter I, Berger A. On the size of the active site in proteases. I Papain Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidah N G, Hamelin J, Mamarbachi M, Dong W, Tadros H, Mbikay M, Chretien M, Day R. cDNA structure, tissue distribution, and chromosomal localization of rat PC7, a novel mammalian proprotein convertase closest to yeast kexin-like proteinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3388–3393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siezen R J, Leunissen J A M. Subtilases: the superfamily of subtilisin-like serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1997;6:501–523. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spencer J A, Jeenes D J, MacKenzie D A, Haynie D T, Archer D B. Determinants of the fidelity of processing glucoamylase-lysozyme fusions by Aspergillus niger. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:107–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Hombergh J P, Fraissinet-Tachet L, van de Vondervoort P J, Visser J. Production of the homologous pectin lyase B protein in six genetically defined protease-deficient Aspergillus niger mutant strains. Curr Genet. 1997;32:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s002940050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox C A, Redding K, Wright R, Fuller R S. Mutation of a tyrosine localization signal in the cytosolic tail of yeast Kex2 protease disrupts Golgi retention and results in default transport to the vacuole. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1353–1371. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]