Abstract

The molecular diversity among 60 isolates of Renibacterium salmoninarum which differ in place and date of isolation was investigated by using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. Isolates were grouped into 21 banding patterns which did not reflect the biological source. Four 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer (ITS1) sequence variations and two alleles of an exact tandem repeat locus, ETR-A, were the bases for formation of distinct groups within the RAPD clusters. This study provides evidence that the most common ITS1 sequence variant, SV1, possesses two copies of a 51-bp repeat unit at ETR-A and has been widely dispersed among countries which are associated with mainstream intensive salmonid culture.

Renibacterium salmoninarum is an important cause of clinical and subclinical infections among farmed and wild salmonid populations in North and South America, Europe, and Japan (5). The organism causes a chronic, systemic, and granulomatous infection, bacterial kidney disease (BKD), that is often fatal under conditions which are stressful to the host (11). There is no effective vaccine or chemotherapy, and the presence of subclinical infections complicates attempts to control the disease through programs of eradication. An improved understanding of the transmission and spread of BKD is of considerable importance in policy management issues relating to aquaculture and wildfisheries. There have been a number of studies investigating the presence, prevalence, and means of transmission of BKD within and between fish populations. This work has shown that R. salmoninarum is endemic within many wild salmonid populations as a low-level, subclinical infection; it has been isolated in up to 100% of samples (9, 12, 15). However, the epidemiology of BKD remains unclear, mainly because of the difficulty of differentiating isolates of R. salmoninarum by biochemical, serological, and multilocus enzyme electrophoresis techniques (1, 6, 16).

We used two approaches to assess the extent of molecular variation among R. salmoninarum isolates from different geographic locations. First, we investigated possible polymorphisms in specific regions within the genome, genes msa (3), rsh (4), and hly (8), and the rRNA genes, including the intergenic spacer (ITS) regions. PCR and DNA sequencing studies have shown that R. salmoninarum has only limited variation in these regions (7). Identifying specific markers of variation in the R. salmoninarum genome, such as insertion sequences or variable numbers of tandem repeats (TR), has been constrained by a paucity of sequence information. Second, we analyzed differences throughout the genome using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. RAPD analysis is a PCR-based alternative method to the use of species-specific DNA sequences for isolate or strain differentiation. The method uses short random primers for rapidly detecting genomic polymorphisms under low-stringency conditions (18, 19). RAPD analysis is widely used for differentiating bacterial isolates (2, 10, 17) and relies on small quantities of genomic DNA, making it ideal for the study of slowly growing and fastidious organisms, such as R. salmoninarum. Previous studies show that, compared with other techniques, RAPD analysis is a reliable and reproducible means for differentiating isolates of R. salmoninarum (7). In the present study we used RAPDistance software to produce an objective analysis of RAPD profiles which were generated from the genomes of 60 R. salmoninarum isolates from a variety of sources in order to identify clusters of the isolates and determine whether there is any correlation with geographic or biological source. Furthermore, we identified the locus of a TR and showed that variation within this locus and within another specific region of the R. salmoninarum genome, the nucleotide sequence of the 16S-23S rRNA ITS region, is reflected in the RAPD analysis.

Generating RAPD profiles of R. salmoninarum.

Sixty isolates of R. salmoninarum obtained from a variety of countries in Europe and North America, including the type strain, NCIMB2235 (ATCC 33209), were cultured in selective kidney disease medium (SKDM) broth supplemented with 5% spent broth culture at 15°C for 6 to 10 weeks. A description of the isolates, sources, and the positive identification of each as R. salmoninarum has been previously published (7). Genomic DNA was isolated by using the Puregene D-6000 DNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Gentra Systems Inc.). PCR amplification was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer), and we used two RAPD protocols and eight random 10-mer primers which have been described elsewhere (7). PCR products were analyzed on 1.2% agarose gels in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The RAPD patterns were visualized by UV illumination, images of each gel were captured with a Kodak DC40 digital camera, and the DNA profile was analyzed by using the RAPDistance software package (http://life.anu.edu.au/molecular/solfware/rapd.html). The patterns were normalized with the bands that were uniformly present in all patterns, and the presence or absence of major bands was recorded in a binary matrix. Very faint bands were excluded from the analysis. A band was scored as absent only if no visible band was present within a 2% size range. The patterns generated with each of the primers were combined for each isolate, and the pairwise distances for the combined band patterns were calculated by using the Dice algorithm described by Nei and Li (13). An unrooted tree was constructed based on the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (14), using NJTREE and TDRAW software (L. Jin and J. W. H. Ferguson, University of Texas Health Science Centre, Houston).

Differentiating R. salmoninarum isolates by RAPDistance analysis.

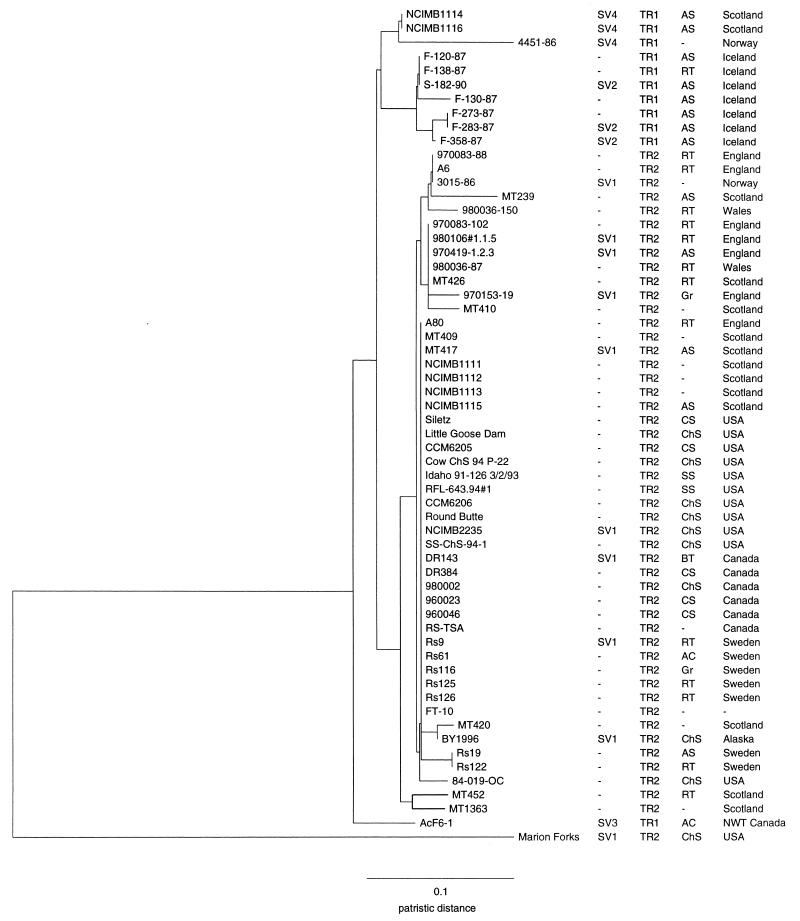

The data for each primer were combined, and for each isolate a total of 86 bands were used to generate a distance matrix, of which 11 bands were invariant, i.e., present in all 60 isolates. By using RAPDistance software, isolates were placed in 21 clusters; 1 of these was a single major cluster which contained 29 of the 60 isolates studied (Fig. 1). The patristic distance between most paired groups was less than 0.1, reflecting the close relatedness of most isolates. Only a single isolate, Marion Forks (from the United States), was sufficiently different to exceed this value. There was no correlation of banding pattern with biological source. All Icelandic isolates were grouped in four closely associated clusters, and most of the isolates from England and Wales were grouped in four adjoining clusters. However, no strong correlation with the geographic origin of isolates was found; the single major cluster of 29 isolates contained the bulk of isolates from the United States, Canada, and Sweden and half of the isolates from Scotland.

FIG. 1.

Unrooted dendrogram, generated by the neighbor-joining method (15), of RAPD patterns for R. salmoninarum isolates (n = 60). Isolate designations and the respective ITS1 sequevar, number of TR at the ETR-A locus, biological source, and geographical origin are indicated. RT, rainbow trout; BT, brook trout; AS, Atlantic salmon; CS, coho salmon; ChS, chinook salmon; SS, sockeye salmon; Gr, grayling; AC, Arctic char.

TR allele profile of R. salmoninarum isolates.

We identified an exact TR repeat locus (ETR-A) in the R. salmoninarum genome during routine sequencing of DNA fragments cloned from a number of different isolates. The repeat unit, with a length of 51 bp, was located in an open reading frame; we used PCR to examine variation in this region of the genomes of 60 R. salmoninarum isolates which differ in place and date of isolation. The isolate numbers are listed in Fig. 1, and the isolates are more fully described elsewhere (7). We amplified this locus using a set of specific PCR primers, 17D+95 (5′-TCGCGAATAGCTTGGCCATTTTGC-3′) and 17D-344 (5′-CGTAGCACCGAAGTCAGATAAGAG-3′), complementary to flanking DNA. Both strands of selected PCR amplicons were sequenced to confirm that our PCR products corresponded to the expected region and number of TR copies. PCR amplification and sequencing were performed under conditions exactly as described for the amplification of specific R. salmoninarum genes (7). Most isolates yielded PCR products of an identical size, 301 bp, which contained two copies of the TR. Interestingly, all Icelandic isolates examined, as well as NCIMB1114 and NCIMB1116 (from Scotland), 4451-86 (from Norway), and AcF6-1 (from the Canadian northwest territories), yielded PCR products of 250 bp which contained only a single copy of the repeat. Furthermore, all of these isolates were clustered separately from the majority of R. salmoninarum isolates by RAPDistance analysis (Fig. 1).

R. salmoninarum isolates with a single TR unit are not SV1.

Members of our group have previously shown that although the R. salmoninarum 16S-23S rRNA ITS (ITS1) is highly conserved three sequence variants which reflect the geographic origin of isolates exist (7). A majority of R. salmoninarum isolates from a wide variety of sources appear to belong to SV1. The other ITS1 sequence variants SV2 and SV3, are more restricted in their distribution. The DNA sequences of ITS1 are already known for isolates S-182-90 (from Iceland) and AcF6-1, and they correspond to SV2 and SV3, respectively. In order to investigate whether any relationship between ITS1 sequence variation and ETR-A exists, we sequenced ITS1 for five isolates, NCIMB1114, NCIMB1116, 4451-86, F-283-87, and F-358-87, which possess a single copy of the TR at the ETR-A locus. The ITS1 was amplified and sequenced by the protocol previously described for PCR amplification and double-stranded sequencing of this region (7). The DNA sequences obtained in this way were found to belong to SV2 (F-283-87 and F-358-87) and a previously unknown ITS1 sequevar, SV4 (NCIMB1114, NCIMB1116, and 4451-86) (GenBank accession no. AF178998 to AF179002). DNA sequence data for the ITS1 region of selected isolates, including 3015-86 (from Norway) and MT417 (from Scotland), which possess two copies of the TR show that these belong to SV1 (Fig. 1). Therefore, ETR-A has a potential use as a specific marker for rapidly distinguishing ITS1 sequence variants.

The purpose of this study was to examine the molecular diversity of isolates of R. salmoninarum from the United Kingdom, other European countries, and North America and from a variety of salmonid host species. Previous research has shown that R. salmoninarum is a highly conserved genospecies with a remarkable degree of biochemical, serological, and genetic uniformity among isolates (1, 6, 16). Furthermore, studies of the R. salmoninarum genome have shown that isolates from diverse sources possess only limited sequence variation in the ITS of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes (7). Members of our group have previously (7) identified three ITS1 sequevars (SV1, SV2, and SV3). We found that isolates from Iceland (SV2), Japan (SV2), and the Canadian northwest territories (SV3) possessed three single-base substitutions in the ITS1 and showed some divergence from the highly conserved SV1, which was present in isolates from the United States, the United Kingdom, mainland Europe, and Canada. We proposed that in areas of the world which could be regarded as relatively isolated from the mainstream intensive salmonid culture of North America and Europe, the bacterium shows genetic divergence. The results presented here broadly support this hypothesis, although some isolates, most notably Marion Forks, vary from this pattern.

This study used an objective method based on RAPDistance software to examine the extent of molecular diversity among R. salmoninarum isolates from different countries around the world and related this information to specific regions of variation within the genome. We have identified four 16S-23S rRNA ITS1 sequevars and an exact TR locus (ETR-A) which are specific markers of variation within the genome of the bacterium, and furthermore, we have shown that an objective method of analysis of RAPD profiles, which can be used to differentiate R. salmoninarum isolates, reflects these specific markers.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences for DNA fragments and for ITS1 regions of isolates have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers AF178991 to AF178997 and AF178998 to AF179002, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food U.K., project code FC1103.

We thank the technicians and staff at CEFAS Weymouth, especially Edel Chambers and Gavin Barker, for freeze-drying and performing purity checks of R. salmoninarum cultures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruno D W, Munro A L S. Uniformity in the biochemical properties of Renibacterium salmoninarum isolates obtained from several sources. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;33:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakroun C, Urdaci M C, Faure D, Grimont F, Bernadet J-F. Random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis provides rapid differentiation among isolates of the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum and among Flavobacterium species. Dis Aquat Org. 1997;31:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien M S, Gilbert T L, Huang C, Landolt M L, O'Hara P J, Winton J R. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene coding for the 57-kDa major soluble antigen of the salmonid fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;75:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90414-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evenden A J. Gene cloning techniques in the study of the fish pathogen Renibacterium salmoninarum. Ph.D. thesis. Plymouth, United Kingdom: University of Plymouth; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evenden A J, Grayson T H, Gilpin M L, Munn C B. Renibacterium salmoninarum and bacterial kidney disease—the unfinished jigsaw. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1993;3:87–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodfellow M, Embley T M, Austin B. Numerical taxonomy and emended description of Renibacterium salmoninarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:2739–2752. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grayson T H, Cooper L F, Atienzar F A, Knowles M R, Gilpin M L. Molecular differentiation of Renibacterium salmoninarum isolates from worldwide locations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:961–968. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.961-968.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayson T H, Evenden A J, Gilpin M L, Martin K L, Munn C B. A gene from Renibacterium salmoninarum encoding a product which shows homology to bacterial zinc-metalloproteases. Microbiology. 1995;141:1331–1341. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonsdottir H, Malmquist H J, Snorrason S S, Gudbergsson G, Gudmundsdottir S. Epidemiology of Renibacterium salmoninarum in wild Arctic charr and brown trout in Iceland. J Fish Biol. 1998;53:322–339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kersulyte D, Woods J P, Keath E J, Goldman W E, Berg D E. Diversity among clinical isolates of Histoplasma capsulatum detected by polymerase chain reaction with arbitrary primers. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7075–7079. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7075-7079.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesa M G, Maule A G, Poe T P, Schreck C B. Influence of bacterial kidney disease on smoltification in salmonids: is it a case of double jeopardy? Aquaculture. 1999;174:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers T R, Short S, Farrington C, Lipson K, Geiger H J, Gates R. Comparison of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the fluorescent antibody test (FAT) for measuring the prevalences and levels of Renibacterium salmoninarum in wild and hatchery stocks of salmonid fishes in Alaska, USA. Dis Aquat Org. 1993;16:181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nei M, Li W H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders J E, Long J J, Arakawa C K, Bartholomew J L, Rohovec J S. Prevalence of Renibacterium salmoninarum among downstream-migrating salmonids in the Columbia River. J Aquat Anim Health. 1992;4:72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starliper C E. Genetic diversity of North American isolates of Renibacterium salmoninarum. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;27:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Wittam W T S, Berg C M, Berg D M. RAPD (arbitrary primer) PCR is more sensitive than multilocus enzyme electrophoresis for distinguishing related bacterial strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5930–5933. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams J G K, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingley S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]