Abstract

Small cell clusters exhibit numerous phenomena typically associated with complex systems, such as division of labour and programmed cell death. A conserved class of such clusters occurs during oogenesis in the form of germline cysts that give rise to oocytes. Germline cysts form through cell divisions with incomplete cytokinesis, leaving cells intimately connected through intercellular bridges that facilitate cyst generation, cell fate determination and collective growth dynamics. Using the well-characterized Drosophila melanogaster female germline cyst as a foundation, we present mathematical models rooted in the dynamics of cell cycle proteins and their interactions to explain the generation of germline cell lineage trees (CLTs) and highlight the diversity of observed CLT sizes and topologies across species. We analyse competing models of symmetry breaking in CLTs to rationalize the observed dynamics and robustness of oocyte fate specification, and highlight remaining gaps in knowledge. We also explore how CLT topology affects cell cycle dynamics and synchronization and highlight mechanisms of intercellular coupling that underlie the observed collective growth patterns during oogenesis. Throughout, we point to similarities across organisms that warrant further investigation and comment on the extent to which experimental and theoretical findings made in model systems extend to other species.

Keywords: symmetry breaking, germline cysts, oogenesis, collective growth, cell lineage trees

1. Introduction

Nestled between the two biological extremes of single cells and organisms with trillions of cells, are small cell clusters with few to dozens of cells. Despite their relative simplicity, theoretical studies have shown that several emergent properties associated with complex multicellularity arise already in these smaller systems [1,2], and experimental studies that probe the evolution of multicellularity from unicellular ancestors have revealed the emergence of behaviours such as division of labour, irreversible differentiation, intercellular cooperation, and increased rates of programmed cell death shortly upon evolution into multicellular forms to ensure propagation [3–5]. Both eukaryotes and bacteria are thought to have forayed into the realm of multicellularity on several occasions, with different selective pressures giving rise to distinct multicellular forms: aggregative multicellularity arises when separated or scattered cells aggregate into a mass (e.g. Dictyostelia—cellular slime mould, and myxobacteria) [6,7], while clonal multicellularity arises when cells proliferate with incomplete separation of the daughter cells, forming clusters of intimately connected clonal cells (e.g. Choanoflagellates—microscopic aquatic organisms, and filamentous cyanobacteria) [5,8–12].

In addition to having played a role in the evolution of multicellularity, clonal clusters are critical for the formation of organisms’ reproductive cells (gametes). Across numerous invertebrates, vertebrates and some mammals including humans, oocytes and sperm develop within clusters of connected cells called germline cysts (or nests) prior to their entry into meiosis [13–18]; germline cysts therefore constitute a conserved phase in the life history of gametes [13]. Germline cysts form through incomplete divisions of a founder cell that leave daughter cells connected through an arrested and stabilized cytokinetic furrow called an intercellular bridge (ICB). The result is a cell lineage tree (CLT), where cells and ICBs define the nodes and edges of the tree, respectively [13,14,17,19]. ICBs are found across numerous, diverse species and have diameters that are several orders of magnitude larger than gap junctions, thereby acting as intercellular channels that facilitate both bidirectional and directed transport of cytoplasmic molecules and organelles [16,17,20–25]. In contrast to transient ICBs that are severed in complete cytokinesis, ICBs found in germline cysts are stabilized through the recruitment of a slew of stiffening cytoskeletal proteins, allowing these intercellular channels to persist for days, much longer than the minutes-long timescales involved in furrow constriction [17,20]. In males, where typically all cells develop into sperm, ICBs facilitate diverse processes such as synchronous differentiation and gametic equivalency of haploid spermatids [26,27], while in females, where typically one or several cells develop into oocytes while the rest become support cells, ICBs are critical for synchronizing cell cycles and oocyte fate determination [28]. Female germline cysts, especially those in insects and increasingly those in mammals, are more extensively studied and are better understood—both structurally and molecularly—than those found in males [29–31]. Germline cysts in females have therefore been the subject of numerous quantitative and biophysical modelling studies [1,32–38] and are the focus of this review.

Oogenesis typically culminates with the generation of an oocyte that is competent to develop further and support early embryonic life when fertilized; however, there appear to be several paths towards that end, as there exists an incredible diversity in the size (number of cells), topology and collective behaviours of the intermediate germline cysts. For example, while some CLTs are linear, others are branched [39–41]; while the oocyte in some species is connected to a single support cell, in others it may be connected to several or even hundreds of support cells [42–44]; while some germline cysts form through synchronous divisions, resulting in clusters with 2n cells, others do so asynchronously [41,45]. Germline cysts therefore represent a trove of developmental problems that lend themselves uniquely to mathematical modelling. In this review, however, we have restricted ourselves to the following line of inquiry: can mathematical models of the cell cycle, coupled with cell–cell coupling, account for the diversity of CLT sizes and toplogies in the animal kingdom, and can such models inform our understanding of phenomena such as symmetry breaking, cell cycle synchronization and growth dynamics in CLTs?

The fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster has emerged as a leading and relevant experimental model of animal oogenesis and collective cell dynamics. Its claim to fame largely derives from the animal’s amenability to powerful genetic tools, as well as fixed and live imaging protocols, fast generation times and low maintenance cost. Furthermore, the Drosophila ovary (figure 1a), and the egg chamber in particular, which houses the germline cyst, are largely invariant structures, thus facilitating the systematic study of complex biological processes—and given recent advances in immunohistochemistry and imaging—with high spatio-temporal resolution [32,33,52,53].

Figure 1.

Formation and growth of the Drosophila germline CLT. (a) The ovaries of Drosophila are located in the female’s abdomen. Each ovary contains several ovarioles, each of which comprises the germarium, which houses the stem cell niche, and several sequentially developing egg chambers. (b) Schematic of an ovariole. The germarium, a specialized signalling microenvironment, lies at the anterior end of the ovariole and houses the germline and follicle stem cells that give rise to the germline cyst and the overlying somatic epithelium in the egg chamber, respectively. Region 1 is the region of mitotically active cysts, where a founding cystoblast, which arises through asymmetric division of the germline stem cell, undergoes four serial, synchronous, and highly streotypic divisions to generate a 2-, 4-, 8- and a 16-cell cyst (see panel (c)). Since these divisions occur with incomplete cytokinesis, the daughter cells remain connected through stabilized intercellular bridges (ICBs) called ring canals, giving rise to an invariant cell lineage tree (CLT). In region 2, one cell in the cyst differentiates into an oocyte, while the remaining 15 become support nurse cells. In region 3, the 16-cell cyst is encapsulated by somatic epithelial cells, forming an egg chamber that buds out of the germarium and joins the ovariole. As the egg chamber moves posteriorly, its volume increases substantially, without changes in the number of germline cells. Arrows extending through the ring canals depict two modes of intercellular transport in the egg chamber: bidirectional transport through diffusion, and directional transport that is mediated by a polarized cytoskeletal network. As the egg chamber develops, the ring canals grow as well, increasing their diameters from approximately 0.5 μm to 10 μm. (c) Schematic illustrating the synchronous divisions, that give rise to a CLT, in region 1 of the germarium. Here, nodes correspond to cells and edges to ring canals. Although it is bilaterally symmetric, nodes in this CLT can be unambiguously labelled according to a cell’s position in the division history: cell 1 is the oocyte, and cells 2–16 are the nurse cells. (d) Schematic of the fusome—a branched, cytoplasmic, membranous organelle that permeates the 16-cell cyst through the ring canals [46]. The fusome derives from the spectrosome, a spherical structure found in the germline stem cell [47,48]. At each subsequent division in the germarium, the fusome associates with the newly forming cells [22,49–51], and fuses with the fusome already present in the older cells, thus permeating the entire cyst [48].

In Drosophila, each of the two ovaries comprises several strings (ovarioles) of sequentially developing egg chambers, with each ovariole providing a snapshot of the oocyte producing assembly line [54]. Each egg chamber, which is the multicellular precursor to the oocyte, is made of a germline cyst that is covered by an epithelium (figure 1a). The egg chamber is produced in the germarium, which is a structure that lies at the most anterior end of each ovariole. The germarium houses the germline stem cells that divide asymmetrically, giving rise to a stem cell daughter and a differentiating cystoblast (figure 1b). This founding cystoblast undergoes four synchronous rounds of cell divisions with incomplete cytokinesis, generating a 16-cell cyst with highly stereotypical ICB connections called ring canals (figure 1b) [55,56]. The nodes of this CLT can be unambiguously labelled by a cell’s position in the division history (figure 1c,d). As one cell differentiates into an oocyte, the remaining 15 cells become support ‘nurse’ cells that synthesize and transport proteins, messenger RNAs (mRNAs), organelles and nutrients to the oocyte to support its growth and development [52,57]. The germarium houses a second population of stem cells, the follicle stem cells, which give rise to epithelial cells; once these cells envelop the germline cyst, the resulting egg chamber exits the germarium [57–59]. The journey from germline stem cell to cystoblast to germline cyst with differentiated cell types and, ultimately, to an egg chamber depends on a slew of signalling pathways and interactions with surrounding somatic cap, filament and escort cells in the germarium. These cells collectively make up the ovarian stem cell niche, providing the molecular signals necessary for regulating maintenance and differentiation of the somatic and germline stem cells, for promoting synchronous divisions of the cystoblast, and for facilitating adhesion between the germline cyst and the epithelium that are necessary for egg chamber formation [60–63]. Physical interactions also play a role. Anchoring of the germline stem cells to their niche through accumulation of DE-cadherin at the junctions between the germline stem cells and somatic cap cells is critical for their self-renewal [61]. Furthermore, differentiation of the cystoblast depends on direct interactions with the escort cells’ long cellular protrusions, which are thought to assist in propelling the cyst through the germarium through repeated and dynamic encapsulation and release of the cyst [61,64,65].

The highly reproducible size and connectivity of the Drosophila 16-cell germline cyst, the extensive characterization of key molecular actors and their interactions, and the rapid advances of powerful genetic tools that enable targeted perturbations, have made Drosophila germline cysts particularly well-suited to model-based exploration and mathematical representation [34,35]. As such, Drosophila germline cysts will be the basis from which concepts are presented and experimental and theoretical findings surveyed; however, throughout this review, we will explore the diversity of CLTs and their collective behaviours across the animal kingdom and, where appropriate, highlight unexplored connections across organisms, from bacteria to mammals.

2. The diversity of germline cell lineage trees

A CLT encodes the history of cell divisions and the evolution of cell types [66]. Hierarchical CLTs therefore reveal key features of multicellular tissues. In whole organisms, however, their reconstruction is challenging. By comparison, germline CLTs are considerably simpler, permitting accurate tracing of cell connections and surveying of the zoology of topologies found across species. Throughout this review, we focus only on germline cysts found in animals with polytrophic meroistic ovaries [39,67–71]. In such ovaries, oocytes are connected to support cells through ICBs and develop alongside these support cells in a single cluster (figure 1b) [39,67–71]. These contrast with telotrophic meroistic ovaries, where there is a single cluster of support cells that is restricted to the germarium, and is connected to numerous oocytes developing along the ovariole through nutritive chords rather than through ICBs [39].

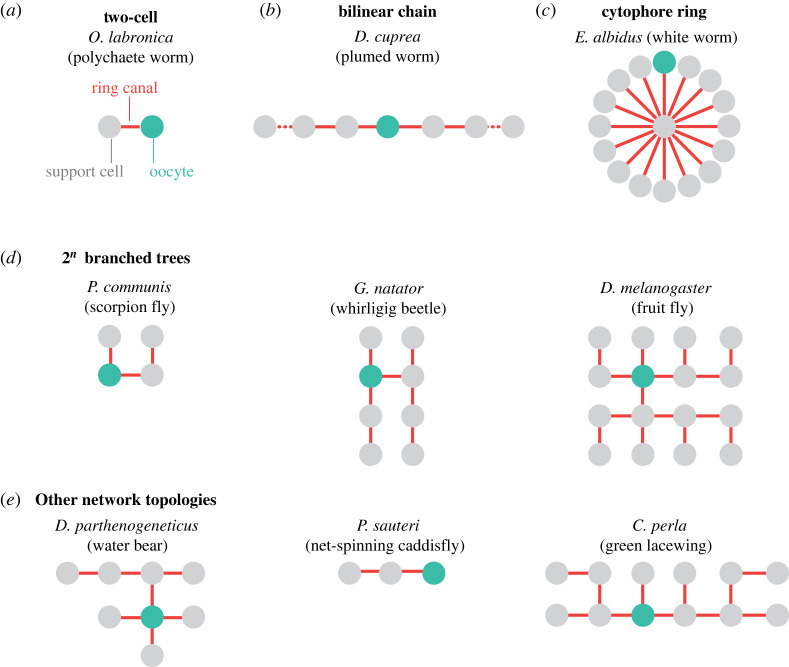

Given its regularity, the 16-cell maximally branched CLT in Drosophila has been the focus of much of the literature on polytrophic meroistic ovaries (figure 1b,c); however, different organisms exhibit varying patterns of divisions, generating CLTs of different topologies and sizes [17,21]. Indeed, among polytrophic meroistic ovaries, there exist four primary CLT network types, encompassing the vast majority of observed patterns [72]. The first of these classes is the two-cell network, where the oocyte is connected to a single support cell (figure 2a). Such cysts are found in the polychaetous annelid worm Ophryotrocha labronica [75], the biting midge Forcipomyia taiwana [42], earwigs (order Dermaptera) [43,76,77] and multiple fungus gnats of the genus Sciara [78,79]. The next class is that of bilinear chains (figure 2b), composed of two long strings of support cells emanating from a central oocyte. These cysts are found in springtails (class Entognatha) [80–82], the polychaetous annelid plumed worm Diopatra cuprea [40], the springtime fairy shrimp Siphonophanes grubei [83] and many net-winged insects (order Neuroptera) [84]. The third class of CLTs, like those found in clitellate annelids, are those in which the germline cyst comprises a ring of cells surrounding a central anucleated cell called a cytophore (figure 2c) [72,85–88]. Often, only one of the peripheral cells of the ring is selected to become the oocyte, while the rest become support cells that transport developmental components and communicate with the oocyte through the cytophore; in others, as in Piscicola geometra, multiple oocytes develop within a single cyst [87,89].

Figure 2.

Zoology of germline CLT topologies across species. Although there is a vast diversity in topology and size (number of cells) of germline cysts across species, many animals form germline cysts that fall into one of four distinct categories. These include (a) two-cell cysts, consisting of an oocyte attached to a single support cell, (b) long, bilinear chains of support cells connected to a central oocyte, (c) rings of cells connected to a central cytophore, and (d) maximally branched trees consisting of 2n cells. A small number of characterized animals have germline cysts whose toplogy do not fall into these categories, such as the water bear Dactylobiotus parthenogeneticus [45], caddisfly Parastenopsyche sauteri [73] and lacewing Chrysopa perla [74], whose series of connections are provided in (e). For all CLTs, support cells are shown in grey and oocytes in green.

The final class, that of maximally branched trees, encompasses the best characterized examples. In the majority of cases, these cysts form as the result of synchronous divisions, forming new branches at each step and giving rise to cysts of 2n cells, where the two most central cells of the cyst are connected to n other cells [90]. Simple examples of four cell cysts (n = 2) are found in two types of clam shrimp, Cyzicus tetracerus and Lynceus brachyurus of different orders (Spinicaudata and Laevicaudata, respectively) [91], the scorpion fly Panorpa communis [92], and the bark lice Peripsocus phaeopterus and Stenopsocus stigmaticus [93]. Extending one round of division further are the whirligig beetles Gyrinus natator [94] and Dineutus nigrior [95], sheep ked Melophagus ovinus [96], and the majority of moths and butterflies in the order Lepidoptera [97–102]. A large portion of characterized cell cyst shapes in this class are those that contain 16 cells, as in Drosophila (figures 1b and 2d). Animals with such cell trees include the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis [103], blowfly Calliphora erythrocephala [104], moth midge Tinearia alternata [105], winter crane flies of the family Trichoceridae [106], tropical African latrine botfly Chrysomya putoria [107], gray flesh fly Sarcophaga bullata [108], tsetse fly Glossina austeni [109] and great diving beetle Dytiscus marginalis [90]. A small number of organisms have been shown to undergo a fifth round of synchronous divisions to form a 32-cell cyst, such as the mole flea Hystrichopsylla talpae [110] and parasitic wasp Habrobracon juglandis [111].

While the aforementioned categories comprise the majority of characterized germline cysts, there exist numerous animals whose germline CLTs do not fall in these categories. Examples include the net-spinning caddisfly Parastenopsyche sauteri [73], which forms a simple three-cell cyst with the oocyte at one end, and the green lacewing Chrysopa perla, which forms a 12-cell CLT via asynchronous divisions [74]. Organisms like the bumblebee Bombus terrestris and the Argentine ant Linepithema humile also form tree-like cysts through asynchronous terminal divisions, resulting in numerous long, linear branches [41]. Another example is the water bear Dactylobiotus parthenogeneticus [45], which does not fit well within any of the categories due to its atypical cell connections (figure 2e).

Notably, germline cysts can vary in size and topology even within the same animal. For example, in the Argentine ant L. humile, the distribution of germline structures is bimodal: approximately half have 16 cells while the other half have 32 cells [41]. Furthermore, in animals such as the water bear Thulinius ruffoi [112], sawfly Athalia rosae ruficornis [113] and mouse Mus musculus [114], CLTs exhibit clear pattern in their size or connectivity. These examples contrast starkly with the highly stereotyped Drosophila germline cyst, and raise questions regarding the biological processes that underlie their emergence. In what follows, we therefore explore whether the formation of this zoology of CLTs can be understood within a unified mathematical framework of growing networks. In detailing similar studies of coupled cell cycles in well-explored systems, we specify the components of a minimal model necessary for cyst generation (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Minimal features of a cell cycle oscillator model for germline CLT generation. (a) Simplified model of a cell cycle oscillator: (1) active cyclin is produced at rate ksynth. (2) Active cyclin activates destruction of cyclin via the function f. (3) Active cyclin feeds back positively onto cyclin activation via the function g. (b) For the simplified model in (a), example nullclines (obtained by setting equations (3.1) and (3.2) to zero) and oscillation trajectory. (c) Hypothesized mechanism of cell cycle communication via diffusion of cyclin between connected cells. One cell (top) becomes mitotic before others; then, diffusion of active component leads to wave of activation, synchronizing oscillators. (d) The same cell cycle oscillator as in (a) but now under control of the accumulating protein Bam, which inhibits degradation of cyclin. The result can be arrest of cell cycle oscillations in exchange for a stable fixed point. (e) For the model in (d), example nullclines and example trajectories. Protection of cyclin by Bam (see panel (d)) shifts the nullcline for total cyclin towards higher concentrations. (f) Cell division either occurs in line (lower) or results in a new branch (upper). Here, cell 3 divides into cells 3 and 5. Evidence from Drosophila females suggests that the fusome biases cells divisions to form new branches, thus resulting in a maximally branched 16-cell tree.

3. Dynamics of cell lineage tree formation

Germline cyst development requires mechanisms for controlling cell proliferation, mediating cell communication, establishing cell division orientation, and terminating those divisions. Despite the power of germline cysts as an experimental system, no mathematical model currently exists that explains the formation of observed sizes and topologies of their CLTs. By contrast, numerous modelling efforts have been dedicated to early embryonic cleavages in Xenopus and Drosophila, which have benefited from extensive experimental characterizations [115–117]. In what follows, we describe the experimental evidence for the dynamics of proteins that play a key role in germline cyst formation and summarize this experimental picture in a simple mathematical model. For simplicity, this discussion assumes that no cells are removed from the network during cyst formation, which is true for organisms like Drosophila, but not true for mice [18].

At a basic level, the formation of multicellular cysts depends on an oscillatory element that drives cell division. This oscillatory element is provided by the cell cycle, which in eukaryotic cells is commonly divided into a temporal sequence of cell growth (G1), DNA replication (S), a second gap phase (G2) and mitosis (M) [118,119]. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and their activating cyclins oscillate both in total concentration and in activity, inducing phosphorylation events that drive the cell in or out of the S or M phases [120]. The result of mitosis is two daughter cells that must again complete the cell cycle before dividing [121]. The network of interactions underlying these oscillations can vary significantly both across organisms and within the same organism, from one tissue to another [122]; nevertheless, some common elements exist. For example, cyclins are frequently strongly self-activating [122]: the activation rate of a specific cyclin, with its CDK partner, monotonically increases with the amount of active cyclin present (figure 3a). This self-activation frequently occurs via cyclin-mediated degradation of its own inhibitor or via phosphorylation-mediated activation of its own activator [122–124]. Conversely, activated cyclins frequently also activate, either directly or indirectly, complexes that target cyclins for degradation (figure 3a).

This picture can be translated into a set of ordinary differential equations for cell cycle oscillations within an individual cell. Only in special cases, like early embryonic cell cycles in Xenopus, is the cell cycle an autonomous limit cycle oscillator, composed of cyclin-CDK complexes, their activators, inhibitors and degradation machinery [125,126]. More generally, the oscillator is non-autonomous and will not proceed if other processes like DNA replication are not complete. In principle, this set of equations could contain tens or hundreds of distinct proteins and could depend explicitly on DNA replication and cell growth [122]. Because we seek a minimal model, we restrict ourselves to equations for total cyclin concentration CYCtot and active cyclin concentration CYCact for a single cell (figure 3a,b) [117,127,128]. With this simplification of the cell cycle, the concentration of active cyclin can be represented in the following way:

| 3.1 |

while the total concentration of cyclin obeys

| 3.2 |

Here, CYCact is produced at a rate ksynth. CYCact nonlinearly increases cyclin degradation via some function, f(CYCact), while CYCact nonlinearly increases activation of cyclin via another function, g(CYCact), and CYCact is inactivated through first-order kinetics with rate constant ki. With proper parameter choices, these equations can produce limit-cycle oscillations around an unstable fixed point (figure 3b). If the timescale of cyclin degradation is much slower than the timescale of cyclin activation and inactivation, then the oscillator becomes a relaxation oscillator: most of the time the system is at high CYCact or low CYCact with fast transitions in-between [128]. Although we have formulated this problem in terms of protein concentrations and generic functions f(CYCact) and g(CYCact) (figure 3a), for simplicity one could instead assume that the cell cycle oscillator behaves like the well-studied FitzHugh–Nagumo oscillator [129,130].

These equations can be extended from a single cell to a cyst of connected cells by accounting for how the cell cycle state of one cell affects its neighbour(s) (figure 3c). In theory, it is possible that these cells behave as autonomous oscillators. Some divisions that appear highly synchronous, like early embryonic cleavages in Xenopus, lack cell cycle coupling [131]; however, for cases like the Drosophila female cyst, this would require rather strong synchrony constraints among the individual cells. Each cell cycle period in this case is estimated to be approximately 12 h, yet the appearance of mitotic spindles and breakdown of nuclear envelopes within the same cyst has been observed within 20 min of each other [53]. Thus, even if cell cycle were perfectly synchronized at the end of the previous division, the cell cycle period would have to vary by less than two per cent to be consistent with current observations.

To synchronize the mitotic activity of neighbouring cells in the cyst, we consider two forms of coupling between cells: advective and diffusive, which both concern how the local concentration of activated cyclin in one cell affects that in another cell. For the case of advection, we assume that the local concentration of actomyosin depends on the local cell cycle state. Thus, desynchronized cell cycles can generate non-uniform actomyosin-driven stress, which in turn can generate forces to redistribute cytoplasmic components [132]. Note however that although large-scale cytoplasmic flows have been observed in the later stages of oogenesis, no evidence exists to date for such flows in mitotic cysts [133]. Simple diffusion of an oscillating component, such as CYCact, is another means for intercellular communication [130] (figure 3c). Diffusive coupling can lead to a travelling wavefront, which separates a region of high CYCact from a region of low CYCact [134–136]. Simple dimensional analysis, considering the diffusion coefficient D with units of length squared per time and k corresponding roughly to the reaction rate driving switching between high and low CYCact states, generates an estimate of for the speed of the wave [134,137].

Even in Drosophila germline cysts, the specific mechanism of cell cycle coupling has remained elusive. There exists some evidence that a membranous and branched organelle called the fusome, first identified in spermatocytes of several insects over a century ago [138], plays a role in the coordination of cell cycle activity [23,47,139]. While the fusome has been most extensively studied in Drosophila [22,48,49,140–142], this organelle appears to be evolutionarily conserved across a vast array of animals [71,90,98,102,143–151]. With each round of divisions, residues of this microtubule precursor from previous generations of cells fuse with those within newly formed cells after mitosis, thereby extending the fusome throughout the growing cell tree (figure 1e) [22,49]. In Drosophila, the fusome comprises a number of components, including α-spectrin, the adducin-like hu-li tai shao (hts), the spectraplakin Short stop (Shot) and the adaptor protein Ankyrin [140,152,153]. In female germline cysts of mutants that lack a fusome, cell cycle synchrony is lost even in the presence of cytoplasmic continuity [23,142]. Additionally, a particular cyclin, Cyclin A, localizes to the fusome during G2 and prophase [139]—a finding that has led to the hypothesis that this localization helps drive the Drosophila cyst synchronously into mitosis [139]. Therefore, current hypotheses tend to favour the propagation of a wave of mitotic activation via the fusome, mathematically encoded by diffusion of the active component, rather than communication via cytoplasmic flows (figure 3c). To incorporate this cell–cell communication into equations (3.1) and (3.2), we propose treating the individual cells as individual agents (each with their own scalar CYCact and CYCtot variables) with the discrete analogue to diffusion (a discrete Laplacian) over the network backbone [154,155]. One could also simplify the cyst to a collection of one-dimensional line segments—connected where ICBs would exist in the actual cyst—along which a wave of mitotic activation propagates [135].

As coupled cell cycle oscillations in the germline cyst do not go on indefinitely, a mechanism must also exist for turning cell cycle oscillations off. In some contexts in Drosophila development, cell cycle control is mediated by controlling activation of cyclins, thus making g(CYCact) non-constant. For example, the protein Checkpoint Kinase (Chk1), which accumulates during Drosophila embryonic nuclear cycles, slows the cell cycle period by inhibiting an cyclin activator, until the degradation of cyclin activators arrests synchronous divisions [127,156–158].

Exploring how the number of cell divisions is regulated during germline cyst formation requires characterization of mutant cysts with variable numbers of cells. In Drosophila, the number of rounds of division can be altered to three or five via mutations in the genes half pint [159] or encore [160,161], respectively. These mutant phenotypes suggest that cell cycle control requires controlled degradation of cyclins, as both Encore and Half pint affect proteins that regulate cyclin degradation [159,161,162], making f(CYCact) non-constant (figure 3d). Consistent with these phenotypes, arrest of oscillations in the germline cysts appears to be mediated by accumulation of the protein Bag of marbles (Bam), which inhibits degradation of cyclins [160,162,163]. This effect can be incorporated in the model by multiplying f(CYCact) by the expression 1/1 + Bam(t)/KBam, where Bam(t) is the monotonically increasing concentration of Bam and KBam quantifies the concentration of Bam necessary to substantially inhibit cyclin degradation.

If cell cycle arrest depends on the accumulation of Bam, this would suggest that the number of cells in the cyst, dictated by the number of completed oscillations, depends on the relative rates of cell cycle oscillations and accumulation of the inhibitor. Therefore, the nullclines, given by setting equations (3.1) and (3.2) equal to zero, drift as a function of Bam accumulation during cell cycle oscillations, until only a single stable fixed point exists (figure 3e). This simple physical model has been tested by independently controlling these two rates [163]: slowing down accumulation of the inhibitor relative to cell cycle oscillations results in cysts with more cells than wild-type, while slowing down cell cycle oscillations relative to accumulation of the inhibitor resulted in cysts with fewer cells than wild-type.

While these experimental manipulations often generate cysts which could not have been formed through synchronous divisions, the simple model described does not address the subtle question of how some cells become post-mitotic while others continue to divide [163]. For example, how can one generate divisions at the termini of a tree, as in the Argentine ant L. humile [41], while more central cells are post-mitotic? One could imagine this is the result of the cell cycle inhibitor being non-uniformly distributed throughout the cyst, potentially via association with a non-uniformly distributed fusome [47,48]. Another possibility is that even in the case of uniform inhibitor, the wave of high CYCact is initiated at termini, but during propagation, the nullcline moves such that the unstable fixed point (and corresponding limit cycle) is lost in exchange for a stable fixed point (figure 3b,e), leading to wave arrest.

Importantly, synchrony in cell divisions, or lack thereof, does not uniquely determine CLT topology. Distinct topologies can arise through orientation of a cell’s mitotic spindle, as its orientation determines the axis of cell division (figure 3f), with consequences for the daughter cells and the tissue overall [164]. In the Drosophila germarium for example, spindle orientation contributes to asymmetric division of the germline stem cell to form a cystoblast: the daughter cell that maintains contact with the interface of the niche continues to receive the self-renewal signal Decapentaplegic (Dpp), a member of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family that promotes germline stem cell division and represses the critical differentiation factor Bam [62,165], while the daughter that is distant from the niche, displaced only by a single cell diameter, experiences derepression of Bam expression, diverges in fate, and becomes a cystoblast (figure 1b) [166–168]. Subsequently, during the divisions that give rise to the maximally branched CLT, spindle orientation is highly ordered: one of the two mitotic centrosomes associates tightly with the fusome, orienting the planes of cell division and ensuring the stereotypical branched pattern of the Drosophila germline cyst [169]. Notably, the role of the mitotic spindle in constraining the plane of cell division and resulting CLT topology has also been described in choanoflagellates—a model organism for studying the origins of multicellularity and emergence of different cell types [9,170,171]. Here, in the absence of cell rearrangements, the fixed orientation of division results in cells that are connected in linear chains [170] or planar sheets [172]. Cell rearrangements further contribute to the possible topological outcomes and generate forms not permissible through cell division orientation alone. For example, to generate a spherical rosette observed in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta, cells must bend, allowing non-sister terminal cells to meet at an enclosure [9].

We note that some key questions remain concerning the mechanism by which the cell cycles are arrested. For example, figure 3d,e suggests that all cells in the cyst arrest in a high CYCtot state; however, current experimental evidence suggests that the cells arrest in a low cyclin state [161]. A factor which could reconcile our simple model with that observation is that the protein which plays a role in inhibiting cyclin degradation (Bam, figure 3d) first rises, then falls [163,173]. It is therefore possible that the purple nullcline in figure 3 first rises, then falls in response to a transient pulse of Bam. An additional complicating factor not included in our model is the role of surrounding somatic cells in the germarium in regulating cell cycle progression of the cyst: somatic cells called escort cells (not depicted in figure 1b) are thought to promote synchronous divisions in the cyst via ecdysone signalling [63]. However, the specific way by which such external signals couple to the dynamics of cyclins remains unclear. Nonetheless, even in the absence of a definitive biological understanding of the mechanisms regulating CLT topology and size, this area is a rich playground for mathematical exploration. Much effort has been dedicated to the dynamics of coupled oscillators, as well as to communication on a fixed network topology; this particular biological problem unites both fields by generating a network structure based on oscillations on the current network state. The remainder of the review focuses on the more well-explored problem of communication in fixed, post-mitotic networks.

4. Symmetry breaking in cell lineage trees

A cell’s identity can affect its morphology, proliferative behaviour and capacity to perform tasks associated with its differentiated state. The formation of specialized cell types is called differentiation—a process that is perhaps most striking during early embryonic development in animals: as all cells of the embryo originate from a single cell through mitosis, cells must differentiate into distinct cell types to generate the organism’s specialized cells and tissues. However, the problem of specifying cell fates arises even earlier: in most mammalian and invertebrate females, only one or a subset of cells in a germline cyst differentiates into the future oocyte(s), while the remaining cells become support cells that provide for the oocyte to support its growth [13,114,151,174]. The differentiation of clonal cells into distinct cell types paves the way for the division of tasks within the germline cyst, and is reminiscent of the differentiation of cyanobacterial clonal cells into vegetative cells, which ensures propagation and dispersal, and heterocyst cells, which play a role in energy capture and conversion during growth [175,176].

Drosophila oogenesis is a powerful experimental model for studying cell fate specification and symmetry breaking in a CLT [52]. In contrast to mammals, where the size and structure of germline cysts and the number of oocytes vary [16,18], the number of cells in Drosophila germline cysts is invariant, cells are connected in a stereotypical manner, and only a single cell is specified as the oocyte (figure 1b,c), while the other 15 cells become nurse cells (figure 1b). Specification of the oocyte and subsequent divergence in the fates of germline sister cells is a robust symmetry breaking event with lasting consequences for the future organism: oocyte selection is required for proper oocyte positioning, which is critical for establishing the anterior–posterior axis of the egg chamber and of the future embryo [24,177].

Oocyte specification involves establishing several asymmetries within the germline cyst. Perhaps the most obvious of these is cytoplasmic, characterized by the accumulation of several specific mRNAs and proteins in one of the two cells with four ring canals (the pro-oocytes)—presumably the future oocyte. Examples of such mRNAs include orb, egalitarian (egl) and BicaudalD (BicD), which are initially uniformly distributed throughout the cyst before progressively localizing to one cell [178,179]. Nuclear asymmetries also arise: the synaptonemal complex that underlies the beginning of meiosis first appears in the pro-oocytes in early region 2 of the germarium, spreads to the two cells with three ring canals, and is finally restricted to one of the two cells with four ring canals towards the end of region 2 [180–183] (figure 1b,d). The third asymmetry is structural: microtubules initially span the 16-cell germline cyst, extending through the ring canals to each cell; however, towards the end of region 2 in the germarium, microtubules polarize, landing their minus ends in only one of the pro-oocytes [141,184–186]. The microtubule cytoskeleton facilitates the dynein-dependent transport of oocyte determinants and other components from the nurse cells into the oocyte, thus establishing cyst polarity. Indeed, mutations in two dynein-dependent transport factors, BicD and egl, block oocyte specification, resulting in egg chambers with 16 nurse cells [179,181,183,187].

While the events coinciding with oocyte specification are well-described, how a single cell is selected to become the oocyte remains an active area of research. A scan of the literature reveals two models, which differ from each other in two key aspects: which occurs first—differentiation or proliferation—and whether oocyte selection occurs through a pre-determined or stochastic process [28,185]. There is evidence to support each model; however, as we demonstrate below, the strict opposition between the two models that is often reflected in the literature is an oversimplification, if not perhaps an incorrect one.

The first model postulates that the cyst’s asymmetry arises during the very first division of the founding cystoblast, and that oocyte fate is effectively predetermined (figure 4a) [48,50,51,169]. According to this ‘pre-determination’ model, a major driver of oocyte selection is the fusome (figure 1d) [46], which segregates asymmetrically during the first division of the cystoblast, causing one of the first two cells, i.e. the pro-oocytes, to have greater fusomal volume than the other. The fusome itself derives from the spectrosome, a spherical structure present within the germline stem cell (GSC; during GSC division, part of the spectrosome is inherited by the founding cystoblast) [47,48]. During cell division, the fusome associates with the mitotic spindle in the newly forming cells [22,49–51], gradually fusing with the fusome in the older cell [48]. With each subsequent division however, the older of the two cells retains an asymmetric portion of the fusome; as a result, one of the two cells with four ring canals, acquires more fusome than all other cells. As microtubules have been shown to associate with the fusome, both periodically in later interphase of the cell cycle and continuously in meiotic 16-cell cysts [141,184,188], fusome asymmetry is proposed to predetermine oocyte identity by directing the microtubule network and dynein-mediated transport of oocyte fate determinants towards one cell. Indeed, a recent study has demonstrated that Patronin—a microtubule minus end-binding protein—is recruited to the fusome, where it stabilizes more microtubules in the cell with the greatest fusome material [189].

Figure 4.

Models for symmetry breaking and oocyte specification in the Drosophila germline CLT. (a) In the ’pre-determination’ model, the oocyte is selected at the first cell division, most likely driven by asymmetry in intercellular fusome distribution. This asymmetry persists throughout the divisions, creating a blueprint for microtubule network polarization and leading to a bias in transport of oocyte determinants (e.g. orb). (b) In the ‘stochastic’ model, oocyte selection occurs only once the 16-cell cyst has been formed. Here, each of the two cells with four ring canals has an equal chance to acquire oocyte fate; the ‘winning’ oocyte outcompetes the other cell for some limiting oocyte determining factor(s). The mechanism underlying selection of these two cells among all other 16 is not considered here. (c) Schematic of a two-cell model in which Orb protein and mRNA localization is driven by simple diffusion and autoregulatory interactions. (d) Top: Orb protein promotes its own translation (left), while also promoting the binding and immobilization of orb mRNA, preventing its transport to neighbouring cells (right). These autoregulatory interactions are plotted to highlight their nonlinear effect. Bottom: above a certain threshold, Orb protein greatly increases the translation rate of its mRNA, thus creating a positive feedback loop (left). As more orb mRNA is bound by the protein, the rate of transport between the two cells decreases, thereby enhancing its localization to one cell (right). (e) For a given set of parameters, this model guarantees that one of the two cells is selected as the oocyte; the initial conditions, namely the relative amounts of Orb protein in the two cells, determine which cell is selected.

Support for this model is compelling; however, the evidence remains indirect—not least because of the delay between when oocyte specification occurs and when oocyte identity becomes clear: in this model, oocyte selection is proposed to occur in region 1 of the germarium (figure 1b), while the oocyte’s identity becomes apparent two days later, when the cyst has arrived in region 3 and several fusome components have begun to disintegrate [48]. The role that the fusome plays is also multi-faceted: the fusome comprises several components and the differing phenotypes resulting from their depletion or knockdown within the germline cyst suggest that these components play distinct roles during the early stages of oogenesis. For example, while hts and α-spectrin mutant cysts exhibit a reduced number of cells and a disrupted microtubule network, and largely fail to specify an oocyte [46,50], germline clones of a shot null allele produce 16-cell cysts that often lack an oocyte, but progress to advanced stages of oogenesis [140]. Furthermore, there are several documented germline-specific mutations that do not affect fusome formation and its asymmetric segregation, yet result in cysts that lack an oocyte. For example, BicD and egl mutant egg chambers form normal fusomes, yet fail to accumulate cytoplasmic markers of oocyte fate like orb and osk mRNAs, or the proteins Orb, BicD and Egl in the future oocyte [179,181,183,187]. Notably, to our knowledge,no study has to date demonstrated through direct measurements a correlation between the continuous preferential accumulation of fusome material in one cell and corresponding accumulation of an oocyte specifying factor during cyst formation.

The second model states that there is an element of stochasticity to oocyte selection, and that oocyte selection occurs only after the 16-cell cyst has been formed [47,190]. According to this ‘stochastic’ model, the two pro-oocytes are considered equivalent, with each having an equal chance of becoming the oocyte (figure 4b). Indeed, soon after the 16-cell cyst forms, the pro-oocytes exhibit stark similarities that distinguish them from the other 14 cells: both cells condense their chromatin, assemble meiotic synaptonemal complexes and accumulate several cytoplasmic markers of oocyte identity [180–183]. Eventually, however, one pro-oocyte decondenses its chromatin, loses its synaptonemal complex and reverts to nurse cell fate, while the other retains its synaptonemal complex and condenses its chromatin into a karyosome to maintain meiotic dormancy [182,183]. The ‘winning’ pro-oocyte is thought to acquire its fate by outcompeting the other cell for some limiting oocyte determining factor(s) [181].

Experimental evidence suggests such an oocyte determining factor could be Orb—an mRNA-binding translational regulator of numerous transcripts and a critical ingredient for establishing cyst polarity [191]. Orb is among the earliest cytoplasmic markers for oocyte identity: in the early regions of the germarium, orb mRNA is expressed uniformly in low amounts in all cells of the cyst, yet as the cyst progresses through the germarium, orb mRNA is gradually restricted to the pro-oocytes, and finally to the presumptive oocyte [35,191]. Egg chambers with strong loss-of-function orb alleles form 16-cell cysts but fail to specify an oocyte, while orb nulls fail to form a 16-cell cyst at all [178]. Furthermore, Orb’s regulatory targets include the mRNAs of BicD, Egl and Cup—proteins with key roles in oocyte specification [191–193]. Particularly intriguing about orb is its autoregulatory activity, in which Orb protein binds to sequences in the orb mRNA 3’UTR and activates its own localized expression [192,194,195], thereby ensuring that high levels of Orb specifically accumulate in the oocyte and that the oocyte maintains its fate [191].

Our recent work has computationally evaluated this autoregulatory mechanism and demonstrated that it predicts the emergence of alternative symmetry-broken states—namely, the robust selection of an oocyte in the absence of a pre-existing bias in intercellular transport [35]. To model oocyte selection, we considered a localization mechanism whereby Orb protein in each central cell binds freely diffusing orb mRNA to its fusome. Feedback loops in the model introduce nonlinear terms that induce switch-like behaviours (figure 4c,d). By applying an algorithmic approach implementing topological methods, we enumerated all phase portraits of stable steady states in the limit when nonlinear regulatory interactions become discrete switches. This framework revealed the global connectedness of parameter domains corresponding to robust oocyte specification, while permitting systematic navigation through multidimensional parameter spaces in a large class of biomolecular switches (figure 4e). Specifically, in a model where intercellular transport is symmetric between the two central cells of the developing cyst, there exist regions of parameter space where one of two cells is guaranteed to be selected as the oocyte, independent of initial conditions. This finding suggests that transport bias owing to fusome asymmetry is sufficient, but not necessary, for robust oocyte selection. This insight into oocyte selection is a more general characteristic of symmetric models with positive feedback, where the inherent symmetries of the system lead to pitchfork bifurcations with respect to various parameters within the system [196,197]. Bifurcations of these types are also well-appreciated in the context of collective decision-making, where asymmetries can induce a universal unfolding of the pitchfork bifurcation, skewing the decision towards one option over the other [198,199].

Notably, what the stochastic model for oocyte selection does not account for is what distinguishes the two pro-oocytes from the other cells, and why the oocyte is not selected from any of the other 14 cells (figure 4b,c). In the pre-determination model, one must therefore explain why one cell differs from all the others, while in the stochastic model, one must explain why two cells are different from all the others, and only as a secondary step, can one invoke stochasticity. Perhaps the simplest mechanism that one can posit for oocyte selection is equivalency with bias, in which the slight asymmetry provided by the fusome biases the choice of oocyte to the first cell—a fate that is then sealed by directing flow of other determinants, such as orb; alternatively, asymmetry of the fusome biases the choice of oocyte to the two pro-oocytes, which then employ a secondary mechanism (e.g. as outlined in figure 4c) to duke it out. Such a mechanism has been documented in other well-studied systems of spatially patterned and robust cell fate decision-making. Consider for example the invariant spatial patterning of the equipotent vulval precursor cells in Caenorhabditis elegans: here, the morphogen, the Epidermal Growth Factor orthologue LIN-3, forms a spatially graded signal, giving the vulval precursor cell closest to it a greater chance of becoming the primary cell, and then, through lateral LIN-12/Notch signalling, that initial slight bias leads to stable determination; however, if that cell is ablated, one of the other cells readily takes over [200,201]. Similarly, during bristle determination in the adult fly cuticle, the achaete(ac)-scute (sc) system is expressed in a small proneural cluster of cells with a bias or variation; generally, the cell with the strongest expression of ac-sc becomes the bristle precursor, with subsequent cell–cell interactions mediated by Notch signalling again reinforcing the decision [202,203].

Several aspects of Drosophila oocyte specification remain unclear and raise questions regarding the plasticity of the cells’ differentiated state. Consider for instance the distribution dynamics of the synaptonemal complex—a meiosis-specific structure formed between homologous chromosomes: in Drosophila, the pro-oocytes and the two cells with three ring canals initially all enter meiosis and form synaptonemal complexes [180,181]. As the 16-cell cyst migrates through the germarium (figure 1b), the synaptonemal complexes are restricted to the two cells with four ring canals, before one of these two cells disassembles the synaptonemal complex and commits to a nurse cell fate, while the other becomes the oocyte. The mechanisms underlying dynamics of syntaponemal complex localization remain poorly understood. Furthermore, mutations that disrupt microtubule-dependent transport have been shown to result in loss of oocyte identity and its reversion to nurse cell fate [204], while spindle gene mutants produce germline cysts in which both pro-oocytes becomes oocytes [205]. In Drosophila, perturbations that result in several oocytes typically lead to egg chamber death; however, studies of such mutations may pave the way for understanding oocyte specification in other organisms, in which multiple oocytes are specified in a single cyst [87,89,114]; in such animals, the dynamics and variability of oocyte fate determination have yet to be uncovered.

5. Collective growth dynamics in cell lineage trees

A notable feature of the Drosophila egg chamber as it travels down the ovariole is the emergence of a non-uniform size distribution among the 16 germline cells (figure 1b) [32]. Over the course of 2–3 days, the nurse cells and oocyte diverge in size, with the oocyte eventually dwarfing the volumes of individual nurse cells [32,206]. Reasons for the oocyte’s growth include the transport of materials from the nurse cells and uptake of yolk [184,206,207]. Several studies however also reported that nurse cells closer to the oocyte appeared larger and proposed that the number of ring canals and contact with the overlying epithelium could affect cell size, yet in the absence of single-cell measurements and testable hypotheses, the pattern and mechanism of the cyst’s differential growth remained unknown [19,55,59]. In our previous work, we revisited this phenomenon by identifying and measuring the sizes of all cells in egg chambers throughout oogenesis using three-dimensional imaging and reconstructions [32]. Our results showed that, starting from uniform initial conditions in the youngest egg chambers, nurse cell volumes diverged and groups of cell sizes emerged that correlated with distance from the oocyte (figure 5a) [32,206].

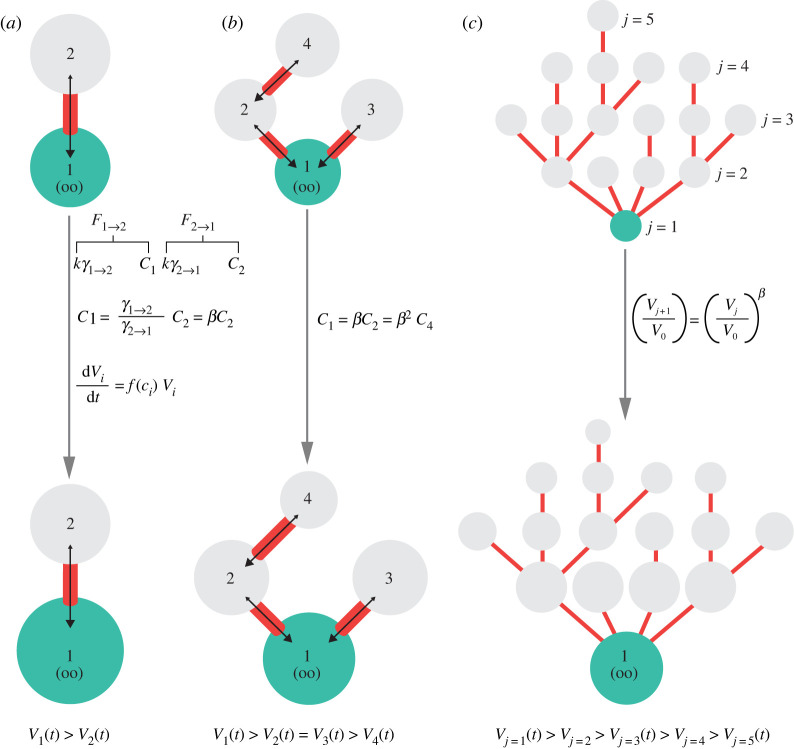

Figure 5.

A biophysical model for differential growth and emergence of allometry in the Drosophila germline CLT. (a) A minimal model of two connected cells, where cell i’s volume Vi grows according to the shown growth law. Cell i has concentration ci of a growth-limiting component that diffuses in the cytoplasm; once at a ring canal, particles have a higher probability (γ) of being transported towards cell 1—the presumptive oocyte (oo). Owing to fast equilibration, forward and reverse fluxes (Fi→j) through the ring canal are assumed equal, and intercellular concentrations of the limiting factor can be related via β, the parameter that quantifies asymmetry in transport at the ring canal. As a result, two cells, initially of uniform size, will grow at unequal rates and diverge in size. (b) Again, following the same growth law as in (a) and owing to polarized transport at the ring canal, cells in a 4-cell tree exhibit differential growth, leading to the emergence of three groups (cell 1; cells 2 and 3; cell 4), where cell size decreases with increasing distance from cell 1. (c) Tree representation of the Drosophila 16-cell germline cyst as in figures 1c and 2d, rearranged in space to highlight the arrangement of nurse cells in groups of 4, 6, 4 and 1 according to their distance (number of intervening ring canals) from the oocyte. Starting from uniform initial conditions, five groups with different cell sizes emerge, as observed experimentally [32]. Taking advantage of the fact that commonly used growth laws are linear at low concentrations (and saturating at higher concentrations), we obtain an allometric relationship for cell sizes at different layers, j, in the tree, where β is an experimentally determined parameter.

To uncover the origin of this cell size pattern, we proposed a coarse-grained mathematical model based on intercellular transport on the CLT whose dynamical variables corresponded to cell volumes (figure 5b). The rate of change in volume of each cell was modelled using Monod-like kinetics, namely, set proportional to a product of its current cell volume and a monotonically increasing function of the concentration of some limiting component, whose identity remains to be determined (figure 5a). Driven by experimental observations, we postulated that this component is exchanged among cells within the cyst and that the probability of being transported through a ring canal connecting any two cells is higher in the direction of the oocyte—namely, that transport, as mediated by microtubules that span the ring canals, is polarized [208,209]. By assuming fast equilibration, cell volumes could be related through a single parameter, β, quantifying transport asymmetry through the ring canal. Starting from uniform initial conditions, 2- and 4-cell models naturally exhibit differential growth at all times (figure 5a,b); when generalized to the 16-cell cyst, a hierarchy in cell sizes emerges correlating with distance from the oocyte (figure 5c). Furthermore, this pattern of decreasing cell sizes with distance from the oocyte can be quantified through an allometric relationship via β—a parameter that quantifies asymmetry in transport at the ring canal, thus linking the process at a molecular scale to cell size. This simple analysis demonstrates that allometry, a feature commonly associated with differential growth at organismal scales, can arise already in small cell clusters [210].

Our recent work has shown that, in addition to cell size, cell cycles in the nurse cells can be similarly grouped according to distance from the oocyte [37]. Upon exiting the germarium, increase in egg chamber volume is driven primarily by the nurse cells that grow dramatically in size by undergoing several rounds of endoreplication—an alternative form of the cell cycle, wherein cells oscillate between S and G phase, synthesizing DNA without undergoing mitotic divisions [211,212]. As a result, the nurse cells become highly polyploid cells that synthesize the components necessary for development of the oocyte. Note that endoreplication, which commences after the egg chamber is formed, leaves the number of nurse cells unchanged at 15 throughout oogenesis and is regulated by Cyclin E (CycE)/Dacapo (Dap) interactions; this cell cycle is a distinct and downstream process from the mitotic divisions required for CLT formation, which occur in the germarium, and are orchestrated primarily via Cyclin A (figure 1a,b) [139]. The two oscillators are thus spatially and temporally separated.

In contrast to the endocycling nurse cells, the Drosophila oocyte remains transcriptionally quiescent during most of oogenesis (developmental arrest of the oocyte is in fact a conserved feature of oogenesis [213,214]). The oocyte has therefore been thought to play a passive role during germline cyst growth, only accepting contents from the polyploid nurse cells. However, our recent work demonstrated that, as in mammals [215], the relationship between the nurse cells and the oocyte is mutually interdependent, meaning that the oocyte is not a mere passenger that depends on the nurse cells for nutrition. Rather, it actively coordinates the nurse cells’ endocycles and the egg chamber’s overall growth [37]. We found that this behaviour could be linked to exchanges between the nurse cells and oocyte, whereby an mRNA produced in the nurse cells is transported to the oocyte, where it is translated into a protein that can diffuse back into the nurse cells (figure 5a). These observations formed the basis of a mathematical model that accounted for these intercellular molecular interactions, along with bidirectional transport along the CLT [37,155].

The endocycles of Drosophila nurse cells are controlled in part by two key proteins: CycE, which promotes S-phase, and Dap, a CDK inhibitor that regulates CycE and allows the onset of G-phase [212,216]. CycE has been shown to exhibit autoregulatory behaviour and to promote production of CDK inhibitors, including dap mRNA [212]. These inhibitors serve to block further production of CycE, causing a decrease in its concentration, thereby completing the cycle (figure 6b). Thus, a cell expressing large amounts of CycE induces the onset of S-phase within the cell and promotes the eventual buildup of Dap, inhibiting CycE, inducing G-phase and continuing the cycle. In parallel, dap mRNA, whose production is promoted by CycE, is transported to the oocyte where it is translated to Dap protein that can diffuse to the nurse cells [37] (figure 6a). Once in the nurse cells, newly formed Dap protein participates in the inhibition of CycE, perturbing the cell cycle oscillations. A mathematical model accounting for these interactions and the cell–cell connections in the Drosophila germline cyst gives rise to groupwise oscillations with a dependence on distance from the oocyte, consistent with experimental evidence (figure 6c) [37]; however, an explicit connection between the emergence of a size gradient and the groupwise oscillations of endoreplication (figure 6), if at all present, remains to be established.

Figure 6.

Intercellular communication and cell cycle coordination on CLTs of varying topologies. (a) Schematic illustrating interactions between known proteins and mRNA in the Drosophila egg chamber. Here, Cyclin E (CycE) in the nurse cells promotes the production of dacapo (dap) mRNA, which is transported to the oocyte, where it is localized and translated. Newly formed Dap protein can diffuse from the oocyte to the nurse cells, where it is involved in inhibiting further CycE production. (b) In any given cell, a limit cycle exists between CycE and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs), which includes Dap. (c) This interaction of CycE, dap, and Dap can induce a wave of activation in a group-wise fashion based on distance from the oocyte. As a result, cells at the same distance from the oocyte on the CLT reach their maximal amounts of CycE (grey) at roughly the same time, as the activation wave propagates towards the terminal end of the network. (d) In the line network archetype and at intermediate coupling levels, there is a clear hierarchy in the amount of perturbation of cell cycle owing to Dap protein, based on a cell’s distance from the oocyte. (e) In the star network, two patterns emerge at sufficient coupling levels: one where all cells exhibit the same amplitude entirely out-of-phase, and one where two cells oscillate at low amplitudes in sync, while the third oscillates out of phase by itself at a higher amplitude. Owing to network symmetry, any of the cells can take on this high-amplitude behaviour, depending on the initial conditions of the system.

Note that while the nurse cells endocycle and develop into highly polyploid cells, the oocyte remains arrested in prophase I of meiosis [213,214], raising the question of how such starkly different modes of cell cycle regulation can be maintained among connected cells that share a common cytoplasm. Here too, Dap was shown to play a key role through interactions with its target CycE/Cdk2. Throughout most of oogenesis, Dap oscillates in the nurse cells, becoming sufficiently low so as to permit high CycE/Cdk2 kinase activity and facilitating entry into the endocycle [212,216]; in the oocyte, however, Dap remains at persistently high levels, thus maintaining the oocyte’s meiotic state (Notch-mediated repression of Dap for instance is required for the mitotic-to-endocycle transition in the overlying epithelium [121,217]). The differential levels of Dap in nurse cells and the oocyte are thought to arise from an initial asymmetry in the balance of CycE/Cdk2 activity and Dap protein between the two cell types, which is amplified through the regulatory relationship between CycE/Cdk2 and Dap. The origin of this initial asymmetry in Dap remains to be determined; one possibility is that the oocyte has a consistently higher concentration of Dap than the nurse cells, as dap RNA is constantly transported to the oocyte, where it accumulates to high levels, while the nurse cells only show low levels of dap RNA [214,216].

To explore the effect of network topology on communication dynamics between the oocyte and support cells [155], we explored the behavioural outcomes of a simplified model of coupled oscillators on three archetypal network types, resembling those found in distinct species: the tree, a maximally branched structure; the line, a system where the oocyte is connected to a chain of nurse cells; and the star, where the only connection for each nurse cell is the central oocyte (figure 2) [155]. Analysis of a simplified minimal model allowed us to describe groupwise coordination by a single parameter quantifying the relative timescales of intercellular transport to degradation of the diffusing Dap protein. In the limits of both low and high coupling of the diffusive inhibitor, where the rate of transport dominated the rate of degradation and vice versa, the topology of the network was not a prime factor in protein localization: a fast rate of degradation quickly removed Dap protein from the system, creating a network of decoupled oscillators, while a fast rate of transport resulted in a uniform distribution of Dap protein. Several interesting behaviours arose, however, when neither timescale was dominant. For example, and perhaps unsurprisingly, we found that in the line network, the effects of inhibition from Dap protein diminish significantly with distance from the oocyte (figure 6d), while in the star network, cells the same distance from the oocyte can exhibit various oscillatory patterns, including in-sync, out-of-sync and phase shifts. Furthermore, in some of these patterns, the amplitude of oscillations was the same throughout all cells, while in others, the amplitudes were asymmetrically distributed, with some cells firing in unison at a lower amount of CycE than others (figure 6e). This observation demonstrates that patterns of oscillation do not necessarily preserve the inherent symmetries of network topologies. Instead, various patterns may emerge based on network size and the initial conditions for the oscillating components within each cell of the network [155].

Extending these simple network types to larger and more complex networks rapidly increases the diversity of coordinated oscillations among groups of cells. Nonetheless, it appears that the key factor in coupling the cell cycles of support cells is the relative timescale of transport to degradation of a diffusing inhibitor emanating from the oocyte. Given that the shape and sizes of cysts in many organisms can be organized into few distinct categories, this minimal model for coupled oscillations is suitable for making predictions about the size hierarchy or groupwise coordination of cell cycles within clusters containing differentiated cell types. Interestingly, in choanoflagellate colonies, where cells are connected through ICBs, albeit not stereotypically as in the Drosophila germline cyst, cells also vary in size, and have been shown to exhibit unique cell morphologies and varying organellar contents indicative of spatially differentiated cell types [171,218]; however, the mechanistic origin of these divergent cell sizes has yet to be determined.

6. Conclusion

This review has focused on a conserved class of small cell clusters that arises during oogenesis and is crucial for formation of a viable egg cell. Despite their relative simplicity, germline cysts partake in numerous complex processes, such as ordered cell divisions, symmetry breaking and cell fate determination, division of labour, and collective growth, making them a rich experimental system for exploring fundamental developmental and biophysical questions. Studies of small cell clusters in general, and of germline cysts in particular, are thus critical for advancing our understanding of more complex living systems.

Accelerating advances in experimental techniques and microscopy have made studies of biological systems increasingly quantitative. These developments, combined with the tractability of germline cysts, should excite theoreticians eager to formulate and test mathematical models in biological systems. One avenue for future exploration is whether a united generative model, based on the experimental characterization of Drosophila, could rationalize the variations observed in germline cysts of other species. Mathematically, a germline cyst is a dynamic graph with node labels, either oocyte or support cell; a united model of such a graph would entail the combination of cell cycle oscillators (§3) and specification of a bistable fate (§4). Consider for instance animals whose germline cysts form through synchronous divisions, giving rise to CLTs with 2n cells, as opposed to those that exhibit asynchronous divisions and generate CLTs with an arbitrary number of cells; or those that give rise to a single oocyte versus those that specify multiple. Do these varying outcomes correspond to two different parameter regimes of the same algorithm, or are they the result of distinct generative mechanisms that are employed by the different species? A second avenue for future exploration centres on uncovering mechanisms underlying differential growth patterns. Generally speaking, studies of collective growth at the organismal level have uncovered two classes of mechanisms that explain the divergence in size of connected parts [32]: the first relies on ‘intrinsic’ differences (e.g. differential expression of key genes in the cells that make up haltere versus the wing in Drosophila [219]), while the second relies on ‘extrinsic’ differences (e.g. competition between connected parts and non-uniform allocation of growth-limiting components, as in the fore- and hindwings of the butterfly [220]). Such spatio-temporal growth patterns are well documented, but are highly complex and notoriously difficult to dissect [210,221,222]. We propose that future studies capitalize on the relative tractability and diversity of germline cysts, which offer a powerful model for uncovering a potential slew of mechanisms underlying divergent growth dynamics in higher animals.

Studies of oogenesis in insects, vertebrates and mammals strongly suggest that germline cyst formation is a conserved process during evolution, with numerous similarities in the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms [13,114,174]; however, key differences between organisms remain. For example, the nature of intercellular transport between support cells and the oocyte in mammalian germline cysts is not nearly as well characterized as in Drosophila, and it is unknown whether support cells in mammalian germline cysts also provide oocyte fate specifying mRNAs to the future oocyte [223]. Mammalian cysts have also been shown to fragment and re-aggregate [18]—an additional complexity that frustrates many conventional algorithms for inferring the history of a dynamic graph [224], and can lead to a distribution over final graph states rather than a single deterministic outcome [18]. It is therefore best to be conservative when extending findings made in Drosophila to other insect species, and especially to the more distant vertebrates and mammals. Furthermore, models developed for oogenesis may require significant modifications if they are to be applied to spermatogenesis, during which germline cysts of connected cells are similarly an obligatory phase. Indeed, we suspect that the zoology of CLT topologies reported here is but a harbinger of the diversity in dynamical processes; uncovering those will be critical for constructing a more holistic view of gametogenesis in the animal kingdom.

Throughout this review, we have highlighted morphological and behavioural similarities between germline cysts in Drosophila—a premier model for studies of collective cell dynamics [32,33,52,53], and powerful models for investigating the evolution of animal multicellularity, such as choanoflagellate and bacterial colonies [9,170,171]. Thus far, studies of the origin of multicellularity and gametogenesis have largely progressed as separate fields, yet they share many commonalities: systems form clonal clusters of cells that are directly connected through cytoplasmic channels, the topologies of the resulting CLTs are heavily influenced by geometric and cytoskeletal constraints, and systems exhibit spatially differentiated cell types and division of labour, as well as differential growth patterns, distinct cellular morphologies and organellar contents [5,171,175,218]. We therefore expect quantitative methodologies, computational tools, and mathematical approaches, as well as the biological insights presented here to prove useful in advancing our understanding of a more general class of small cell networks.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lucy Reading-Ikkanda for assistance with the figures and illustrations. We thank Prof. Trudi Schüpbach for comments on our manuscript, which have helped improve its scope and clarity. We also thank Dr Tatyana Gavrilchenko, Jonathan Jackson and Matt Smart for their careful reading of our work and their feedback. We thank members of the Developmental Dynamics group in the Flatiron Institute for useful discussions.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

R.D.: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; H.N.: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; S.Y.S.: conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; J.I.A.: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM134204 to S.Y.S. and F31HD098835 to R.D.).

References

- 1.Rajapakse I, Smale S. 2017. Emergence of function from coordinated cells in a tissue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1462-1467. ( 10.1073/pnas.1621145114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tompkins N, Li N, Girabawe C, Heymann M, Ermentrout GB, Epstein IR, Testing FS. 2014. Turing’s theory of morphogenesis in chemical cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4397-4402. ( 10.1073/pnas.1322005111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby E, Ratcliff W, Travisano M, Kerr B. 2014. Geometry shapes evolution of early multicellularity. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003803. ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratcliff WC, Dennison RF, Borrello M, Travisano M. 2012. Experimental evolution of multicellularity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1595-1600. ( 10.1073/pnas.1115323109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claessen D, Rozen DE, Kuipers OP, Søgaard-Andersen L, van Wezel GP. 2014. Bacterial solutions to multicellularity: a tale of biofilms, filaments and fruiting bodies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 115-124. ( 10.1038/nrmicro3178) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Q, Kawabe Y, Schilde C, Chen ZH, Schaap P. 2015. The evolution of aggregative multicellularity and cell–cell communication in the Dictyostelia. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3722-3733. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.08.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monds RD, O’Toole GA. 2009. The developmental model of microbial biofilms: ten years of a paradigm up for review. Trends Microbiol. 17, 73-87. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairclough SR, Dayel MJ, King N. 2010. Multicellular development in a choanoflagellate. Curr. Biol. 20, R875-R876. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunet T, King N. 2017. The origin of animal multicellularity and cell differentiation. Dev. Cell 43, 124-140. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratcliff WC, Herron MD, Howell K, Pentz JT, Rosenzweig F, Travisano M. 2013. Experimental evolution of an alternating uni- and multicellular life cycle in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Nat. Commun. 4, 2742. ( 10.1038/ncomms3742) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michod RE. 2007. Evolution of individuality during the transition from unicellular to multicellular life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 8613-8618. ( 10.1073/pnas.0701489104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Trillo I, Roger AJ, Burger G, Gray MW, Lang BF. 2008. A phylogenomic investigation into the origin of metazoa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 664-672. ( 10.1093/molbev/msn006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pepling ME, de Cuevas M, Spradling AC. 1999. Germline cysts: a conserved phase of germ cell development? Trends Cell Biol. 9, 257-262. ( 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01594-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gondos B, Bhiraleus P, Hobel CJ. 1971. Ultrastructural observations on germ cells in human fetal ovaries. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 110, 644-652. ( 10.1016/0002-9378(71)90245-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda T, Hedinger C, Groscurth P. 1975. Ultrastructure of developing germ cells in the fetal human testis. Cell Tissue Res. 161, 55-70. ( 10.1007/BF00222114) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepling ME, Spradling AC. 2001. Mouse ovarian germ cell cysts undergo programmed breakdown to form primordial follicles. Dev. Biol. 234, 339-351. ( 10.1006/dbio.2001.0269) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haglund K, Nevis IP, Stenmark H. 2011. Structure and functions of stable intercellular bridges formed by incomplete cytokinesis during development. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4, 1-9. ( 10.4161/cib.13550) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei L, Spradling AC. 2013. Mouse primordial germ cells produce cysts that partially fragment prior to meiosis. Development 140, 2075-2081. ( 10.1242/dev.093864) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch EA, King RC. 1969. Further studies on the ring canal system of the ovarian cystocytes of Drosophila melanogaster. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 102, 129-152. ( 10.1007/BF00336421) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenbaum MP, Iwamori T, Buchold GM, Matzuk MM. 2011. Germ cell intercellular bridges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005850. ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a005850) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matova N, Cooley L. 2001. Comparative aspects of animal oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 231, 291-320. ( 10.1006/dbio.2000.0120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]