Abstract

The best available evidence and the predictive value of computed tomography (CT) findings for prognosis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are unknown. We systematically searched three electronic databases (MEDLINE, CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov). A total of 410 patients from six observational studies were included in this systematic review. Of these, 143 patients (34.9%) died due to ARDS in short-term. As for CT grade, the CTs used ranged from 4- to 320-row. The index test included diffuse attenuations in one study, affected lung in one study, well-aerated lung region/predicted total lung capacity in one study, CT score in one study and high-resolution CT score in two studies. Considering the CT findings, pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and diagnostic odds ratio were 62% (95% confidence interval [CI] 30–88%), 76% (95% CI 57–89%), 2.58 (95% CI 2.05–2.73), 0.50 (95% CI 0.21–0.79), and 5.16 (95% CI 2.59–3.46), respectively. This systematic review revealed that there were major differences in the definitions of CT findings, and that the integration of CT findings might not be adequate for predicting short-term mortality in ARDS. Standardisation of CT findings and accumulation of further studies by CT with unified standards are warranted.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Tomography, Respiratory distress syndrome

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a respiratory failure disorder characterised by the rapid onset of widespread inflammation in the lungs1. The mortality rate of ARDS is as high as 40%2,3. Many studies have been conducted to identify predictors of acute illness; these predictors include age greater than 70 years, severity of illness scoring, cirrhosis, and sepsis4–6. However, no single factor was proven to be superior to the others.

We hypothesised that certain findings on computed tomography (CT) may be useful to accurately predict mortality. CT imaging is beneficial for the diagnosis of respiratory failure; bilateral opacities on chest CT are used as one of the diagnostic criteria in the Berlin definition1. CT has reportedly been more accurate than chest radiography in detecting the underlying causes and complications of ARDS7. Furthermore, several investigators have revealed that CT findings could predict mortality in ARDS8–11. For example, extensive opacities12–14, traction bronchiectasis13,15 and semi-quantitative score of several CT findings8,15 have been reported as possible poor prognostic factors. However, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review of the predictive value of chest CT has been reported previously. Whether chest CT is beneficial for prognosis is an urgent clinical question in the management of ARDS.

To resolve this clinical question, we conducted a systematic review aimed to determine what types of CT findings were investigated and whether CT findings were predictive of short-term mortality in patients with ARDS.

Methods

Systematic review protocol

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies on diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) were conducted. We followed the methodological standards outlined in the Handbook for DTA Reviews of Cochrane16 and used the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of DTA Studies17 to report our findings. The review protocol was prospectively registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000040725). The need for ethical approval and consent was waived for this systematic review.

Population, index test, and target condition

The target participants were patients with ARDS. We applied the definition of ARDS used in each study in order to collect the relevant studies comprehensively, including those that were published before the Berlin definition was published1. The index tests of interest were all findings on CT, defined in the primary studies. In this study, the target condition to be predicted was short-term mortality, and the reference standards of the condition were defined as 28-day mortality, 30-day mortality, 60-day mortality, or in-hospital mortality, along with the criteria defined by the primary study authors. This is because that The Guidelines on the management of ARDS by the British Thoracic Society define 28-day (almost equal to 30-day) mortality and in-hospital mortality as critically important indicators18 and that several clinical studies19–21 and a meta-analysis22 use 60-day mortality as a benchmark.

Eligibility and study selection

We included all the studies, such as prospective, retrospective, and observational (cohort or cross-sectional) studies and secondary analyses of randomised controlled trial data, that investigated CT findings in patients with ARDS. We excluded case–control studies (two-gate study) and case studies that lacked DTA data, namely true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) values. Two authors independently screened each study for eligibility and extracted the data. Disagreements among reviewers were resolved via discussion or by a third reviewer.

Electronic searching

To identify all eligible studies, we searched the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online via PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (accessed on May 30th, 2020), and ClinicalTrials.gov. We restricted the literature to articles published in English. The details of the search strategy are described in the Supplementary File (Supplementary Table S1 and S2).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were extracted using a predefined data extraction form: study characteristics (author, year of publication, country, design, sample size, clinical settings, conflict of interest, and funding source), patient characteristics (inclusion/exclusion criteria and patient clinical and demographic characteristics), index test (computed tomography), reference standards (30-day mortality, 60-day mortality, or in-hospital mortality), and diagnostic accuracy parameters (TP, FP, FN, and TN). Two investigators evaluated the risk of bias using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2 tool), which included four risks of bias domains and three domains of applicability23. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion or by a third reviewer. Assessment findings were presented using a traffic light plot and a summary plot. Given the absence of evidence for publication bias in DTA studies and the lack of reliable methods for its assessment, no statistical evaluation of publication bias was performed16.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

For a predefined meta-analysis of all CT findings, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of DTA methodology was applied16. Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were captured in paired forest plots to inspect the between-study variance. We used the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) random-effects model for meta-analysis. The HSROC model makes it possible to pool information across studies and derive smoothed estimates of covariate effects, components of variance, and individual study quantities24. In addition, the HSROC model accommodates the variations in cutoff values between studies. The pooled sensitivity and specificity with 95% CI were estimated at a fixed specificity as the median value of primary studies in the same manner as the previous Cochrane review and other systematic reviews25–27. All analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, London, United Kingdom), R version.3.5.3., Meta-DTA (Diagnostic Test Accuracy Meta-Analysis) application28 and CAST-HSROC (calculator for the summary points from the HSROC model) application25.

Ethics statement

This study does not involve human participants.

Results

Study characteristics

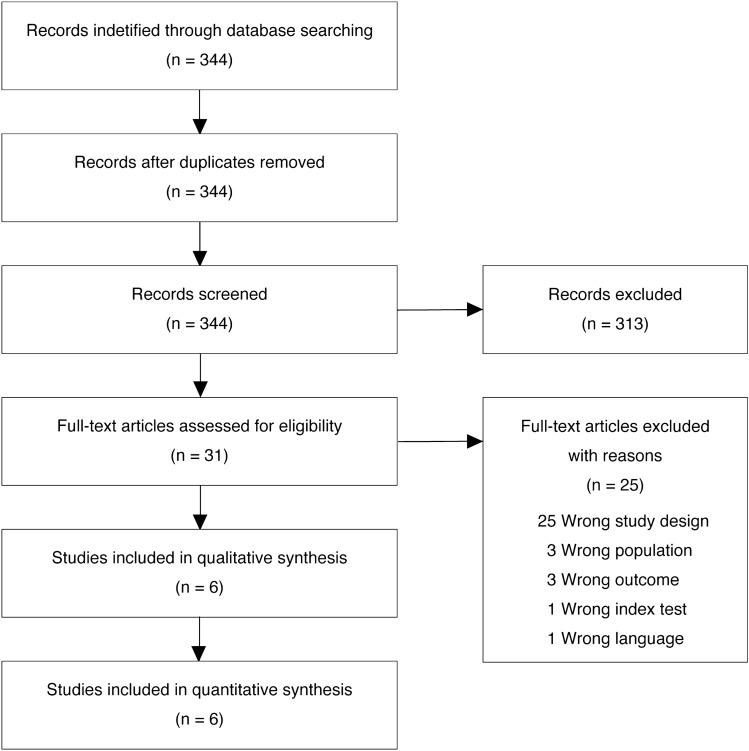

Initially, 344 studies were screened. Six studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the quality assessment and meta-analysis (Fig. 1) (Supplementary Table S3). A total of 410 patients from six observational studies were included (Table 1). Death due to ARDS in the short term occurred in 143 patients (34.9%). The median prevalence of mortality was 38.7% (interquartile range 24.5–49.5%). Two of the six studies were prospective in nature. Most studies (five of six studies) were conducted in the intensive care unit setting. Patient characteristics, index test definitions, and reference standards used in each study are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection.

Table 1.

Summary of the primary study characteristics.

| Author | Nishiyama | Kamo | Ichikado | Chung | Ichikado | Rouby |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2020 | 2019 | 2012 | 2011 | 2006 | 2000 |

| Country | Japan | Japan | Japan | USA | Japan | France |

| Settings | ICU in a university hospital | ICU in a university hospital | ICU in a university hospital | General hospital | ICU in a university hospital | ICU in a university hospital |

| Number of patients | 42 | 140 | 85 | 28 | 44 | 71 |

| Age (mean, years) | 64.2 ± 17.1 | 67 ± 17 | 75 ± 10 | 57.5 ± 15.0 | 61.8 ± 15.6 | 56 ± 17 |

| Data collection | Retrospective | Retrospective | Prospective | Retrospective | Retrospective | Prospective |

| Enrolled period | 2011 to 2013 | 2012 to 2015 | 2004 to 2008 | 1998 to 2006 | 2001 to 2002 | 1993 to 1997 |

| Definition of ARDS | The Berlin definition | The Berlin definition | The AECC criteria | Histopathological diagnosis of DAD | The AECC criteria | The AECC criteria |

| Severity | ||||||

| Index | P/F ratio | The Berlin definition | P/F ratio | – | Lung injury score | Lung injury score |

| Score | 125.1 ± 57.7 |

Mild: 42 Moderate: 71 Severe: 40 |

96.2 ± 45.6 | – | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.6 |

| Gas exchange | ||||||

| PaO2 (mean, Torr) | – | – | – | – | – |

Lobar attenuations: 110 ± 39 Diffuse attenuations: 76 ± 42 Patchy attenuations: 82 ± 30 |

| PaCO2 (mean, Torr) | – |

Mild: 41.0 ± 9.6 Moderate: 47.4 ± 18.8 Severe: 46.7 ± 15.7 |

– | – | – |

Lobar attenuations: 42 ± 6 Diffuse attenuations: 49 ± 11 Patchy attenuations: 47 ± 8 |

| Aetiology of ARDS (%) | Aspiration (23.8%), Pneumonia (21.4%), Sepsis (16.7%), Surgery (11.9%), Trauma (4.8%), Others (21.4%) | Pneumonia (37%), Aspiration (28%), Sepsis (6.5%) | Pneumonia (37.6%), Sepsis (28.2%), Pulmonary (12.9%), Extrapulmonary (15.2%), Others (25.9) | Pneumonia (28.6%), Sepsis (10.7%), Aspiration (7.1%), Pancreatitis (7.1%), Drug reaction (7.1%), Recent major surgery (7.1%) | Pneumonia (36%), Sepsis (16%), Aspiration (7%), Postoperative (7%), Drug related (7%), Near drowning (5%), Pancreatitis (2%), Unknown (20%) | Primary ARDS (69.0%), Secondary ARDS (28.2%), ARDS of both origins (2.8%) |

| Index test | ||||||

| CT modality | 64-Row MDCT | 320-Row MDCT | Various CT/MDCT systems | Various CT/MDCT systems | Various CT/MDCT systems | 4-Row MDCT |

| CT findings | Well-aerated lung region/pTLC | HRCT score | HRCT score | Affected lung | CT score | Diffuse attenuations |

| Positive cutoff value | < 40% | > 210 | > 210 | > 80% | > 230 | – |

| Timing of imaging | At diagnosis | Within 48 h of diagnosis | At diagnosis | Within 14 days of histopathological diagnosis | Within 7 days of diagnosis | – |

| Reference standard | 30-Day mortality | 30-Day mortality | 60-Day mortality | In-hospital mortality | In-hospital mortality | In-hospital mortality |

AECC American–European Consensus Conference, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome, CT computed tomography, DAD diffuse alveolar damage, HRCT high-resolution computed tomography, ICU intensive care unit, MDCT multi-detector computed tomography, pTLC predicted total lung capacity, PaO2 partial pressure of arterial oxygen, PaCO2 partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide.

The index test was as follows: diffuse attenuations in one study12, affected lung in one study13, well-aerated lung region/predicted total lung capacity (pTLC) in one study14, CT score in one study9 and high-resolution CT (HRCT) score in two studies8,15. The CT findings of Rouby’s study were classified as diffuse, lobar, and patchy attenuations according to the extent and location of ground-glass opacity (GGO) and consolidation. The CT findings of Nishiyama’s study were classified as well-, poorly-, and non-aerated lung volume according to the Hounsfield units. In Chung’s study, GGO, consolidation, reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing were investigated. In studies by Ichikado and Kamo, CT and HRCT scores comprised all the six components of CT findings of normal attenuation, GGO, consolidation, GGO with traction bronchiectasis, consolidation with traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing. Two different cutoff values have been reported across studies for the HRCT score (> 210 or 230). The definitions of each index test are provided in Supplementary Table S4. The spatial resolution of the CTs used in these studies differed greatly, ranging from 4-row to 320-row CTs.

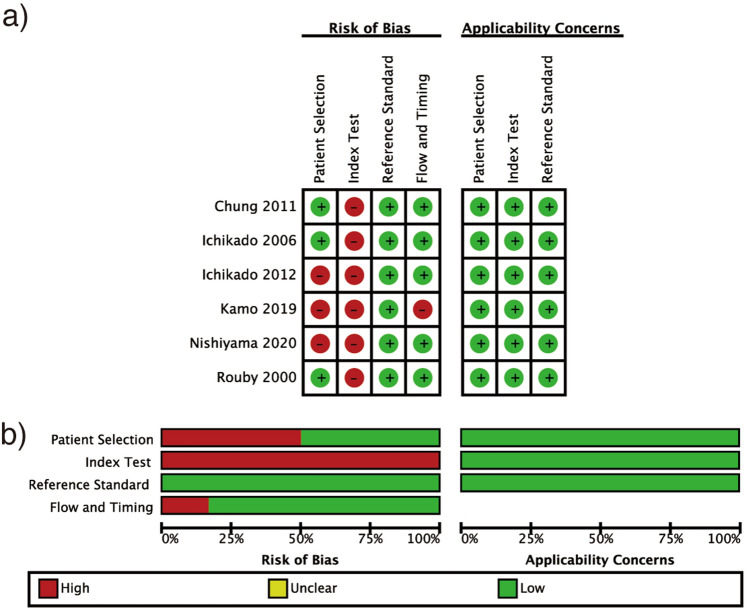

Risk of bias assessment

Based on patient selection, we considered three studies as having a high risk of bias (Fig. 2) (Supplementary Table S5) due to inappropriate exclusion criteria: emphysema, pregnancy, and patients without laboratory data were excluded in one study; while patients resuscitated from cardiopulmonary arrest were excluded in the remaining two studies. Considering the index test, we presumed all the studies to be at high risk since the reference standards were not blinded when the index tests were evaluated in four studies, and two studies did not define the test cutoff point previously. For the reference standard, we considered that no study had a high risk of bias or that there were no serious concerns regarding applicability as mortality seemed to be an objective fact and had to be evaluated accurately. In patient flow assessment, we assessed one study as having a high risk of bias because not all patients were included in the analysis. The overall risk of bias among the included studies was high.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns (a) summary and (b) graph.

Conversely, there were no serious concerns regarding the applicability of the studies.

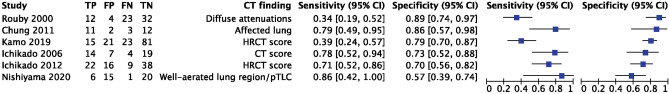

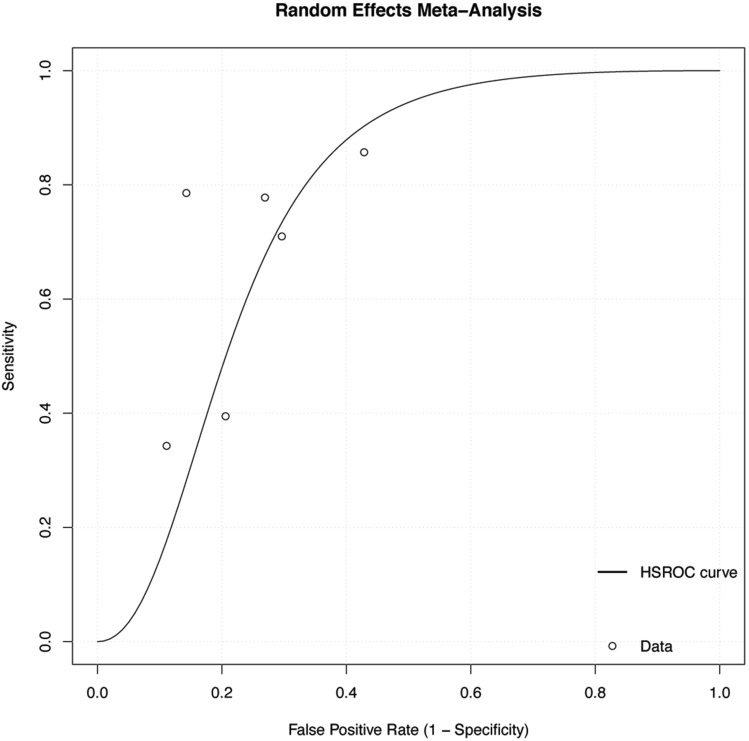

Meta-analysis and predictive value

The differences in the index tests were found to be high. However, since the predefined protocol stipulated that a meta-analysis be performed, we tentatively performed the analysis. The predictive value of CT findings in each study is presented as a forest plot in Fig. 3. Using the HSROC model, a summary ROC curve was plotted (Fig. 4) (Supplementary Table S6). At a fixed specificity of 76% as the median value of the primary study, the pooled sensitivity was 62% (95% CI 30–88%). At this point, the positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and diagnostic odds ratio were 2.58 (95% CI 2.05–2.73), 0.50 (95% CI 0.21–0.79), and 5.16 (95% CI 2.59–3.46), respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Paired forest plot. TP, true positive; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; FN, false negative; CT, computed tomography; HRCT, high resolution computed tomography; pTLC, predicted total lung capacity; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

HSROC curve. HSROC, hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

This systematic review of six studies revealed that CT findings greatly differed in patients with ARDS. As for CT modality, the CTs used ranged from 4- to 320-row, and the CT findings investigated were GGO, consolidation, reticular shadows, traction bronchiectasis, honeycomb lung, or their integration. Tentative meta-analysis showed low sensitivity and specificity for predicting short-term mortality in patients with ARDS (pooled sensitivity 62% [95% CI 30–88%], pooled specificity 76% [95% CI 57–89%]). Both pooled sensitivity and specificity had wide 95% CIs.

We have identified three key strengths of this study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate the prognostic ability of CT for predicting mortality in ARDS. CT is widely used in advanced medical institutions worldwide, and specific CT findings are used as diagnostic criteria for ARDS1. However, CT also has certain disadvantages, such as the manpower required to transport patients, patient safety concerns29, the economic cost of CT imaging, and high dose of ionising radiation exposure30–33. Thus, CT imaging should be performed based on the evidence of clinical utility. This review has demonstrated that the study of CT findings and prognosis is an unexplored field and has potential for future development. Second, we focused on the specific CT findings, including diffuse attenuations in one study, affected lung in one study, well-aerated lung region/pTLC in one study, CT score in one study and HRCT score in two studies. There is no essential difference in the measurement methods between HRCT score and CT score, but caution should be paid to the fact that the cutoff values for the index tests are different (> 210 or 230). On the other hand, since the Ichikado’s study (2012)8 and the Kamo’s study (2019)15 used the same name, the same measurement method, and the same cutoff value, we considered it acceptable to judge them as the same index test. All the findings were based on GGO, consolidation, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, intralobular septal wall thickening, change of Hounsfield units, distribution of opacity, or their combination (Supplementary Table S4, Fig. S2). However, there is no established consensus regarding the specific CT findings that should be the focus of the management of ARDS. Third, this study was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of DTA. Previous systematic reviews of prognostic factors in ARDS have included pathological examination by open lung biopsy34, extravascular lung water index35, and various serum biomarkers (C-reactive protein, cytokines, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, and circulating angiopoietin-2)36–38. Nevertheless, none of these studies have been reviewed in a manner consistent with the principles of the DTA Handbook. A systematic review of DTA should be considered separately from a systematic review of interventions39–41. This is because DTA reviews use their own indices, such as index test, reference standard, and target condition and use specific evaluation methods, such as the QUADAS-2 tool for bias evaluation23,42. Our method could provide a methodological basis for future diagnostic and prognostic studies of ARDS.

The results of this meta-analysis demonstrated that the integration of CT findings might not be a reliable prognostic tool for patients with ARDS. This is because CT has several disadvantages for predicting mortality: 1) timing of imaging, 2) quality of images, and 3) causes of death in patients with ARDS. The timing of CT imaging plays an important role in mortality prediction. Generally, ARDS images show various patterns depending on disease progression. Typical CT findings in ARDS include extensive consolidation/GGOs in the acute phase and fibrotic changes (e.g., traction bronchiectasis or honeycomb lung) in the late phase43,44. These changes in the CT findings do not progress homogeneously, and CT findings can also be affected by therapeutic interventions. For instance, fluid management45,46, drugs47, and respiratory settings including lung protective ventilation48–50, recruitment manoeuvers51,52, and prone position ventilation53. Therefore, it remains controversial whether CT imaging is the most appropriate tool for the predicting prognosis in patients with ARDS in clinical practice. This review shows that the timing of imaging was not standardised in each study (Table 1), which may have resulted in inappropriate timing of imaging for predicting prognosis. Further, CT image quality is an issue. In current practice, multiple detector CT (MDCT) is the usual imaging technology. Even between MDCTs, a tenfold difference in special resolution has been reported (slice thickness in 4-row CT, 5.0 mm; slice thickness in 320-row CT, 0.5 mm)54–56. In this primary study, the number of detector rows included covered a wide range, from 4- to 320-rows (Table 1). Low-quality CT could miss important findings, such as GGO or traction bronchiectasis. The presence of GGO is a well-known indicator of early fibrosis57–60. To avoid missing these findings, it would be necessary to use high-quality CT whenever possible. In addition to the previous two restrictions, the cause of death in ARDS is disadvantageous for CT. It has been pointed out that the severity of lung injury may not correlate with mortality. A prospective observational study found that there was no difference in 28-day mortality between mild and moderate ARDS according to the Berlin definition (mild, 30.9%; moderate, 27.9%; p = 0.70)61. According to previous studies, the most common cause of death in ARDS was multiple organ failure, accounting for 30–50% of deaths62,63. The mortality rate increases with the number of failing organs other than the lungs63. It has been reported that respiratory failure accounted for only 13–19% of all ARDS deaths62,63; it could be difficult to predict prognosis based on the severity of pulmonary injury on CT alone. Our results suggest that attention should be paid to organs other than the lungs to accurately estimate prognosis in patients with ARDS.

This study has several limitations. First, there were a limited number of studies and some retrospective studies were included in this study, which could cause a type-2 error. Pooled sensitivity and specificity had wide CIs; therefore, caution is required when applying these findings to clinical practice. Second, there was some heterogeneity among the included studies. The definitions of the index tests were not homogeneous, and the cutoff points differed even among studies assessing the extent of lung damage. The definition of ARDS was not common across studies, and there was heterogeneity among the patients. It is important to enrol patients using the Berlin definition and standardise the definition of CT findings in future studies. Third, the designs of the studies included in this review were not suitable for assessing predictive value. Because we assumed that few studies had evaluated the predictive value of CT findings in patients with ARDS, we planned to include descriptive and exploratory studies. Extensive inclusion criteria may have reduced the quality of the included studies. Fourth, there was a high risk of bias in all studies, which may have affected the estimates. Most studies did not specify index test thresholds a priori, and the index test results were interpreted without blinding the reference standard results. These biases could be partially attributed to the study design. Additional studies with predefined CT findings are required. Finally, there were no patients with ARDS due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, even though this review was conducted during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Further caution should be applied when evaluating CT findings in patients with ARDS due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In conclusion, patients with ARDS present with various CT findings. The evaluation of CT findings was not standardised in previous studies. This systematic review revealed that the integration of CT findings might not be adequate for predicting short-term mortality in patients with ARDS. Standardisation of CT findings and the accumulation of further studies by CT with unified standards are warranted.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the members of the Japanese ARDS Clinical Practice Guideline Committee of the Japanese Society of Respiratory Care Medicine, the Japanese Respiratory Society, and the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. We also appreciate the librarian at the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine Med.

Author contributions

H.H., T.Y., S.O., Y.O., S.Y., and K.A. contributed to the study design and interpretation. H.H. and S.Y. analysed the data, searched the literature, and drafted the manuscript. H.N., Y.S., S.S., E.T., and S.Y. contributed to the extraction of data and revision of the review draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

No additional data available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally to this work: Hiroyuki Hashimoto and Shota Yamamoto.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-13972-x.

References

- 1.Ranieri VM, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phua J, et al. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time?: A systematic review. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;179:220–227. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-722OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest. 2008;133:1120–1127. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong MN, et al. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: Potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit. Care Med. 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laffey JG, et al. Potentially modifiable factors contributing to outcome from acute respiratory distress syndrome: The LUNG SAFE study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1865–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ely EW, et al. Recovery rate and prognosis in older persons who develop acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;136:25–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-1-200201010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheard S, Rao P, Devaraj A. Imaging of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir. Care. 2012;57:607. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichikado K, et al. Fibroproliferative changes on high-resolution CT in the acute respiratory distress syndrome predict mortality and ventilator dependency: A prospective observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000545. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichikado K, et al. Prediction of prognosis for acute respiratory distress syndrome with thin-section CT: Validation in 44 cases. Radiology. 2006;238:321–329. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2373041515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai SR. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: Imaging of the injured lung. Clin. Radiol. 2002;57:8–17. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiumello D, Froio S, Bouhemad B, Camporota L, Coppola S. Clinical review: Lung imaging in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients—An update. Crit. Care. 2013;17:243. doi: 10.1186/cc13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rouby JJ, et al. Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. II. Physiological correlations and definition of an ARDS Severity Score. CT Scan ARDS Study Group. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1046–1056. doi: 10.1007/s001340051317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung JH, Kradin RL, Greene RE, Shepard JA, Digumarthy SR. CT predictors of mortality in pathology confirmed ARDS. Eur. Radiol. 2011;21:730–737. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1979-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiyama A, et al. A predictive factor for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: CT lung volumetry of the well-aerated region as an automated method. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020;122:108748. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamo T, et al. Prognostic values of the Berlin definition criteria, blood lactate level, and fibroproliferative changes on high-resolution computed tomography in ARDS patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2019;19:37. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0803-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Cochrane Collaboration . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McInnes MDF, et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: The PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths MJD, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2019;6:e000420. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brochard L, et al. Tidal volume reduction for prevention of ventilator-induced lung injury in acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Multicenter Trail Group on Tidal Volume reduction in ARDS. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;158:1831–1838. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9801044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiedemann HP, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2564–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu W, Lin C-W, Liu B-W, Hu W-H, Zhu Y. Extravascular lung water and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure for fluid management in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2014;9:3. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruan S-Y, et al. Exploring the heterogeneity of effects of corticosteroids on acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 2014;18:R63. doi: 10.1186/cc13819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiting PF, et al. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat. Med. 2001;20:2865–2884. doi: 10.1002/sim.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banno M, Tsujimoto Y, Luo Y, Miyakoshi C, Kataoka Y. CAST-HSROC: A web application for calculating the summary points of diagnostic test accuracy from the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic model. Cureus. 2021;13:e13257. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada Y, Nishioka N, Ohtsuru S, Tsujimoto Y. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for detecting pelvic fractures among blunt trauma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020;15:56. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00334-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molano Franco D, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 concentration for the diagnosis of sepsis in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;4:Cd011811. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011811.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman SC, et al. Development of an interactive web-based tool to conduct and interrogate meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: MetaDTA. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019;19:81. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0724-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murata M, et al. Adverse events during intrahospital transport of critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022;52:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard GR, et al. The American–European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Society of Radiology (ESR) European Federation of Radiographer Societies (EFRS) Patient safety in medical imaging: A joint paper of the European Society of Radiology (ESR) and the European Federation of Radiographer Societies (EFRS) Insights Imaging. 2019;10:45–45. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0721-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanal KM, et al. U.S. diagnostic reference levels and achievable doses for 10 adult CT examinations. Radiology. 2017;284:120–133. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berrington de González A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: Estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet. 2004;363:345–351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardinal-Fernández P, et al. The presence of diffuse alveolar damage on open lung biopsy is associated with mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016;149:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Lu B, Ni H. Prognostic value of extravascular lung water index in critically ill patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Crit. Care. 2012;27(420):e421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni Q, Li C, Lin H. Prognostic value of N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020;2020:3472615. doi: 10.1155/2020/3472615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Zee P, Rietdijk W, Somhorst P, Endeman H, Gommers D. A systematic review of biomarkers multivariately associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome development and mortality. Crit. Care. 2020;24:243. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02913-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Yin R, Guo Q. Circulating angiopoietin-2 and the risk of mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020;14:1753466620905274. doi: 10.1177/1753466620905274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Virgili G, Conti AA, Murro V, Gensini GF, Gusinu R. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy and the Cochrane collaboration. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2009;4:255–258. doi: 10.1007/s11739-009-0243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irwig L, et al. Guidelines for meta-analyses evaluating diagnostic tests. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:667–676. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-8-199404150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willis BH, Quigley M. The assessment of the quality of reporting of meta-analyses in diagnostic research: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011;11:163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: A tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gattinoni L, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome profiles by computed tomography. J. Thorac. Imaging. 1986;1:25–30. doi: 10.1097/00005382-198607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelosi P, Crotti S, Brazzi L, Gattinoni L. Computed tomography in adult respiratory distress syndrome: What has it taught us? Eur. Respir. J. 1996;9:1055–1062. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neamu RF, Martin GS. Fluid management in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 2013;19:24–30. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835c285b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casey JD, Semler MW, Rice TW. Fluid management in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;40:57–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1685206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anan K, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of drug-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome compared with non-drug-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: A single-centre retrospective study in Japan. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015330. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brower RG, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amato MB, et al. Beneficial effects of the "open lung approach" with low distending pressures in acute respiratory distress syndrome. A prospective randomized study on mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;152:1835–1846. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amato MB, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1410639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKown AC, Ware LB. Quantification of lung recruitment by respiratory mechanics and CT imaging: What are the clinical implications? Ann. Transl. Med. 2016;4:145–145. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.03.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiumello D, Formenti P, Coppola S. Lung recruitment: What has computed tomography taught us in the last decade? Ann. Intensive Care. 2019;9:12–12. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0497-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelosi P, Brazzi L, Gattinoni L. Prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur. Respir. J. 2002;20:1017. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00401702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldman LW. Principles of CT: Multislice CT. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2008;36:57. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.107.044826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hata A, et al. Effect of matrix size on the image quality of ultra-high-resolution CT of the lung: Comparison of 512 × 512, 1024 × 1024, and 2048 × 2048. Acad. Radiol. 2018;25:869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyata T, et al. Influence of field of view size on image quality: Ultra-high-resolution CT vs. conventional high-resolution CT. Eur. Radiol. 2020;30:3324–3333. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06704-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodman LR, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome due to pulmonary and extrapulmonary causes: CT, clinical, and functional correlations. Radiology. 1999;213:545–552. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv42545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Owens CM, Evans TW, Keogh BF, Hansell DM. Computed tomography in established adult respiratory distress syndrome. Correlation with lung injury score. Chest. 1994;106:1815–1821. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Desai SR, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by pulmonary and extrapulmonary injury: A comparative CT study. Radiology. 2001;218:689–693. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr31689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Remy-Jardin M, Remy J, Giraud F, Wattinne L, Gosselin B. Computed tomography assessment of ground-glass opacity: Semiology and significance. J. Thorac. Imaging. 1993;8:249–264. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199323000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hernu R, et al. An attempt to validate the modification of the American–European consensus definition of acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome by the Berlin definition in a university hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2161–2170. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stapleton RD, et al. Causes and timing of death in patients with ARDS. Chest. 2005;128:525–532. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferring M, Vincent JL. Is outcome from ARDS related to the severity of respiratory failure? Eur. Respir. J. 1997;10:1297–1300. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10061297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No additional data available.