Abstract

We described the case of a peripancreatic paraganglioma (PGL) misdiagnosed as pancreatic lesion. Surgical exploration revealed an unremarkable pancreas and a large well-defined cystic mass originating at the mesocolon root. Radical enucleation of the mass was performed, preserving the pancreatic tail. Histologically, a diagnosis of PGL was rendered. Interestingly, two previously unreported mutations, one affecting the KDR gene in exon 7 and another on the JAK3 gene in exon 4 were detected. Both mutations are known to be pathogenetic. Imaging and cytologic findings were blindly reviewed by an expert panel of clinicians, radiologists, and pathologists to identify possible causes of the misdiagnosis. The major issue was lack of evidence of a cleavage plane from the pancreas at imaging, which prompted radiologists to establish an intra-parenchymal origin. The blinded revision shifted the diagnosis towards an extra-pancreatic lesion, as the pancreatic parenchyma showed no structural alterations and no dislocation of the Wirsung duct. Ex post, the identified biases were the emergency setting of the radiologic examination and the very thin mesocolon sheet, which hindered clear definition of the lesion borders. Original endoscopic ultrasonography diagnosis was confirmed, emphasizing the intrinsic limit of this technique in detecting large masses. Finally, pathologic review favored a diagnosis of PGL due to the morphological features and immonohistochemical profile. Eighteen months after tumor excision, the patient is asymptomatic with no disease relapse evident by either radiology or laboratory tests. Our report strongly highlights the difficulties in rendering an accurate pre-operative diagnosis of PGL.

Keywords: Peripancreatic paraganglioma, Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, S100, Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene and expression, Fine needle biopsy

Core Tip: Our report strongly supports that paraganglioma should be included in the differential diagnosis of peripancreatic/pancreatic masses, highlighting the difficulties in establishing the accurate preoperative diagnosis, even after a second-round evaluation. In fact, due to the deep localization and the lack of specific clinical manifestations and imaging data, early diagnosis often relies solely on a level of suspicion, thus making it more probable to have a missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. Moreover, the limited time spent with a patient in an emergency setting might impair the accuracy of the diagnosis, lowering quality and outcomes of healthcare delivery. A multidisciplinary team approach, involving skilled radiologists, endoscopists, pathologists, and surgeons, is of foremost importance for proper diagnosis and management, preventing undue surgical resections.

TO THE EDITOR

We read with interest the paper authored by Lanke et al[1] on a peripancreatic paraganglioma (PPGL) successfully diagnosed pre-operatively by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)-fine needle aspiration. After a careful review of the literature, the report highlights the enduring difficulties in achieving an accurate diagnosis of this rare entity prior to surgery. Among the 47 pancreatic/peripancreatic PGL reported so far, only 8 (17%) were correctly identified pre-operatively; the majority (n = 29, 62%) were misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocine tumors or pancreatic neoplasms/cysts. In almost all cases (80%), the treatment of choice was surgery, demonstrating the uncertainty of classification for such lesion and its unpredictable behavior[1].

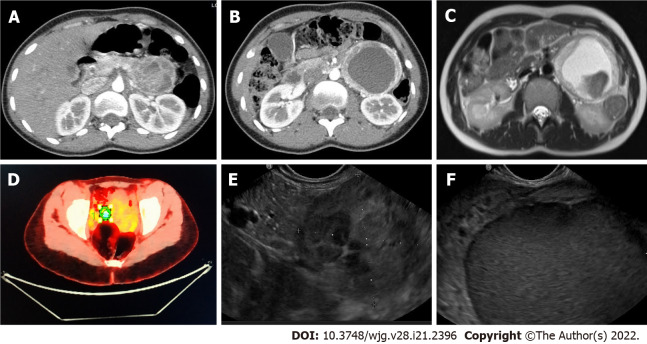

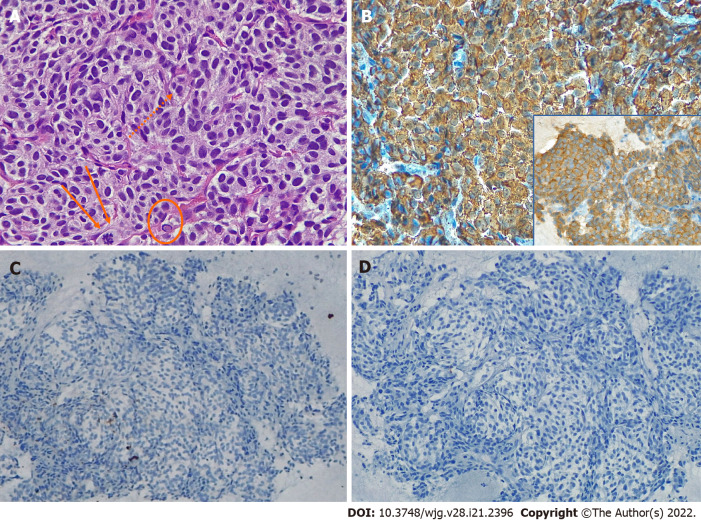

In November 2020, a 23-year-old woman complaining of left hypocondrial pain, diarrhea, and sweating lasting for 4 d, was referred to the Emergency Unit of Ospedale Unico della Versilia. The physical examination was unremarkable, but the abdominal US showed a large cystic, liquid-filled mass close to the pancreatic tail. Whole-body computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a 95-mm cystic lesion with thickened, contrast-enhanced walls and a marked inhomogeneous boundary with the pancreatic tail. The mass seemed to be adherent to the left renal artery, left kidney hilum, and homolateral ureter (Figures 1A and 1B). Imaging work-up was completed with abdominal nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) revealing T1 signal hyperintensity (Figure 1C) and positron emission tomography disclosing abnormal hyperactivity of the mass (standard uptake value 4.7%) (Figure 1D). The suspicion of a solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) vs a cystic pancreatic tumor was posed. Blood tests, including vasoactive intestinal peptide, C-peptide, pancreatic polypeptide, serotonin, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), Ca-125, and Ca-19.9, were within normal range; whereas chromogranin A (CgA) serum levels exceeded 1800 ng/mL (reference range: 0-108 ng/mL). EUS-fine needle biopsy (FNB) was scheduled. EUS examination showed a 10-cm lesion of the pancreatic tail. The lesion was hypoechoic with well-defined borders and a cystic component (Figures 1E and 1F). Two FNB passes were made using a 20 Gauge needle with Rapid On-Site Evaluation to ensure adequate sampling[2]. Intracystic fluid was aspirated and analyzed with the following results: Glucose, 45 mg/dL; pancreatic amylase, 5 U/L; CEA, 1.0 ng/mL; Ca-19.9, 9 U/mL. Cell block examination disclosed nests of small to medium-sized epithelioid cells exhibiting moderate amount of amphophilic granular cytoplasm and oval to round nuclei with smooth contours and dense chromatin (Figure 2A). Occasionally, small nucleoli (Figure 2A dots), sparse mitotic figures (Figure 2A arrows), and intra-cytoplasmic hyaline globules (Figure 2A encircled) were noted, as well as vague rosette-like formations and branching hyalinized fibrovascular cores lined by neoplastic cells. Tumor cells diffusely expressed CgA (Figure 2B), synaptophysin (Figure 2B, inset), and GATA-3. Scattered cells were dot-like positive for AE1/AE3 cytokeratins (Figure 2C). Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), PAX-8, and S100 protein (Figure 2D) were negative. A provisional diagnosis of neoplasm with neuroendocrine differentiation (either PGL or PanNET) vs SNP was made.

Figure 1.

Radiologic findings. A and B: Computed tomography-scan showed a 95-mm cystic lesion with no cleavage plane from the pancreas; C: Nuclear magnetic resonance evidenced that the lesion was hyper-intense in T1; D: Positron emission tomography demonstrated a 4.7% standard uptake value; E and F: Endoscopic ultrasonography identified a hypoechoic mass close to the pancreatic tail.

Figure 2.

Fine needle biopsy findings. A: Proliferation of small to medium-sized cells arranged in a nest pattern was evident, the cells occasionally showed small nucleoli (dots), mitotic figures (arrows), and intra-cytoplasmic hyaline globules (encircled), hematoxylin and eosin original magnification (O.M) × 40; B: Chromogranin A (CgA) positivity of neoplastic cells; inset: Synaptophysin positivity of neoplastic cells, CgA stain, O.M. × 20; B inset, synaptophysin stain, O.M. × 20; C: AE1/AE3 cytokeratins expression in scattered cells, cytokeratin AE1/AE3 stain, O.M. × 20; D: S100 negativity, S100 stain, O.M. × 20).

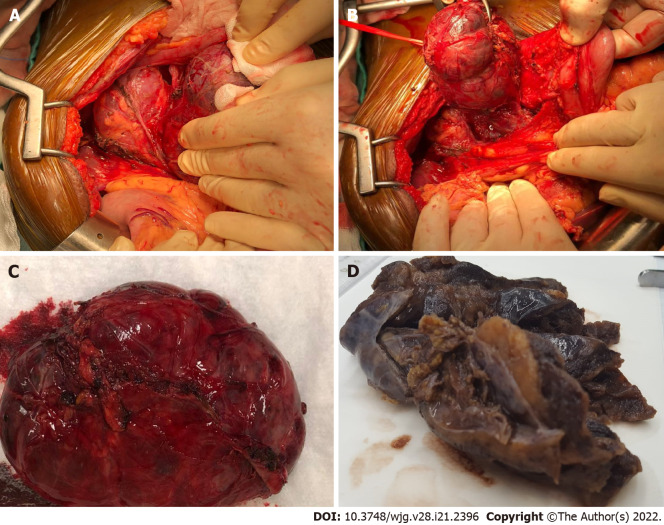

Surgical exploration revealed an unremarkable pancreas and a large well-defined cystic mass underneath the mesocolon plane, originating at the mesocolon root (Figures 3A and 3B). The lesion extended to the inferior margin of the pancreas and was strictly adherent but did not involve the organ parenchyma. As the capsule could be easily detached from the mesocolon sheets and vessels, radical enucleation was performed, preserving the pancreatic tail (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Macroscopic findings. A and B: At surgical exploration a large well-defined cystic mass located underneath the mesocolon plane was found; C: Radical enucleation of the lesion; D: Grossly, the cystic lesion showed a thick fibrous wall with a solid component and a yellowish, lobulated appearance on cut surface.

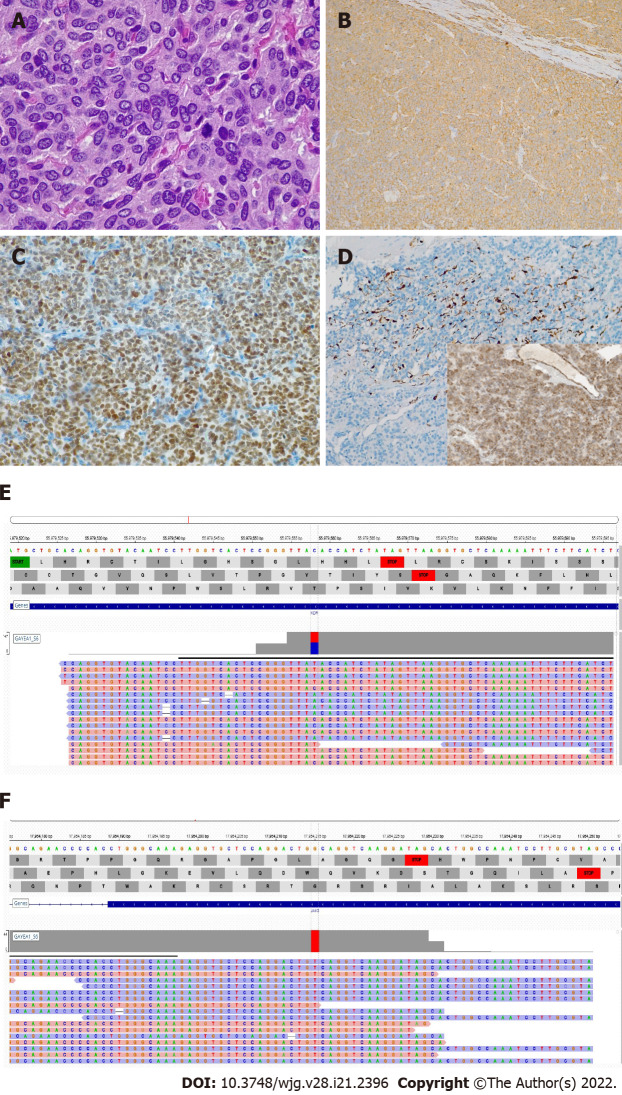

The surgical specimen consisted of a 12-cm hemorrhagic cystic lesion, surrounded by a thick fibrous wall, with a solid component showing a yellowish, lobulated appearance on cut surface (Figure 3D). Microscopically, the tumor was composed of polygonal cells with abundant finely granular eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm, mostly arranged in nests and anastomosing cords (Figure 4A). Areas with a diffuse growth pattern were also noted. Nuclei were regular, round to oval, with granular fine chromatin, small nucleoli, and occasional pseudoinclusions. The stroma was richly vascular. In the more cellular areas, pleomorphic cells with prominent nucleoli and occasional mitotic figures (2/high power field) were observed. There was evidence of focal capsular disruption. Cells were confirmed to be positive for CgA (Figure 4B), synaptophysin, GATA-3 (Figure 4C), and substantially negative for AE1/AE3 cytokeratins, EMA, and PAX-8. S100 and GFAP stained scanty cells encircling cell nests (Figure 4D). A final pathologic diagnosis of PGL, Grading System for Adrenal Phaeochromocytoma and Paraganglioma score 6 (intermediate risk), was rendered[3,4].

Figure 4.

Histologic and molecular findings. A: The lesion was composed of nests and cords of polygonal cells with abundant granular cytoplasm, and occasional mitotic figures in the more cellular areas, hematoxylin and eosin original magnification (O.M) × 60; B: Chromogranin A (CgA) positivity in neoplastic cells; inset: Synaptophysin positivity in neoplastic cells, CgA stain, O.M × 10; C: GATA-3 positivity in neoplastic cells, GATA-3 stain, O.M. × 10; D: S100-positive cells were scattered; inset: Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) expression was preserved, S100 stain, O.M. × 10; inset, SDHB stain, O.M. × 10; E: KDR mutation; F: JAK3 mutation.

Given the young age of the patient and the rarity of the tumor, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) protein expression was evaluated, and next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis, using the commercial kit “Miriapod NGS-IL” (Diatech) on MiSeq Illumina Platform, was carried out to identify mutations affecting genes associated with syndromic and/or familial conditions (i.e., SDHB, VHL, NF1, RET). SDHB expression was preserved (Figure 4D, inset) and none of the above-mentioned genes were found to be mutated, thus ruling out a hereditary condition[5]. Interestingly, we detected two previously unreported mutations, one affecting the KDR gene in exon 7 (c.889G>A missense variant)[6], and another on the JAK3 gene (c.394C>A missense variant) in exon 4[7,8] (Figures 4E and 4F). Both mutations are known to be pathogenetic in olfactory neuroblastoma[6], some forms of leukemia, and solid tumors, such as neuroendocrine tumors[7,8].

Imaging and cytologic findings were blindly reviewed by an expert panel of clinicians, radiologists, and pathologists to identify possible causes of misdiagnosis. The major issue was lack of evidence of a cleavage plane from the pancreas at US, CT, and NMR, which prompted radiologists to establish an intra-parenchymal origin. The blinded revision shifted the diagnosis towards an extra-pancreatic lesion as the pancreatic parenchyma showed no structural alterations and no dislocation of the Wirsung duct. Ex post, the identified biases were the emergency regimen of radiologic examination, which impaired a precise assessment, and the very thin mesocolon sheet, probably on account of the patient’s leanness, which hindered clear definition of the lesion borders, also masked by the extensive hemorrhagic component. Original EUS diagnosis was confirmed, emphasizing the intrinsic limit of the bi-dimensional image of trans-abdominal US in detecting a large mass in the same examination field. Finally, pathologic review of the FNB findings favored a diagnosis of PGL due to substantial negativity for cytokeratins and PAX-8, usually positive in PanNet[9,10], and absence of folded nuclei with longitudinal grooves, cholesterol crystals, and foamy macrophages, usually found in SPN[9]. Furthermore, diffuse cytoplasmic CgA reactivity is typically not seen in SPN[9]. The detection of S100-positive sustentacular cells and zellballen pattern, considering the hallmarks of PGL, has limited value in the diagnosis of PGL, since they may not be present in small samples or in sympathetic PGLs, as in our case[2,11]. Eighteen months after tumor excision, the patient is asymptomatic with no disease relapse evident with CT or NMR imaging; CgA levels are within the reference range.

In conclusion, our report strongly supports the suggestion by Lanke et al[1] that PGL should be included in the differential diagnosis of peripancreatic/pancreatic masses, and highlights the difficulties in establishing an accurate preoperative diagnosis even after a second round evaluation. Indeed, due to the deep localization and lack of specific clinical manifestations and imaging data, early diagnosis of PGL often relies solely on the level of suspicion, thus easily resulting in misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis[12,13]. A multidisciplinary team approach, involving skilled radiologists, endoscopists, pathologists, and surgeons, is of foremost importance for proper PGL diagnosis and management in order to prevent undue surgical resections[14]. In the present case, the first radiologic mistake affected all the diagnostic work-up, even after second round evaluation, and only the long-lasting experience of the surgeon avoided over-treatment (i.e., distal splenopancreasectomy, as reported in most of the cases described so far)[1]. Since there are no definite criteria for malignancy, a close follow-up after surgery is mandatory[14,15]. Pathologists play a key role in providing clues that may disclose genetic profile and predict malignant potential of the tumor[1,3,4,14,15].

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 7, 2021

First decision: January 8, 2022

Article in press: May 14, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Souza HSP, Brazil; Zhang CZ, China A-Editor: Nakaji K S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JJ

Contributor Information

Federica Petrelli, Pathology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Geri Fratini, Surgery Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Andrea Sbrozzi-Vanni, Endoscopic Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Andrea Giusti, Pathology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Raffele Manta, Endoscopic Unit, Santa Maria Misericordia Hospital, Perugia 06122, Italy.

Claudio Vignali, Interventional Radiology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Gabriella Nesi, Department of Health Sciences, University of Florence, Florence 50139, Italy.

Andrea Amorosi, Pathology Unit, Università Magna Graecia, Catanzaro 88100, Italy.

Andrea Cavazzana, Pathology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Marco Arganini, Surgery Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy.

Maria Raffaella Ambrosio, Pathology Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Toscana Nord Ovest, Pisa 56121, Italy. mariaraffaella.ambrosio@uslnordovest.toscana.it.

References

- 1.Lanke G, Stewart JM, Lee JH. Pancreatic paraganglioma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:6322–6331. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i37.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng J, Simsir A, Oweity T, Hajdu C, Cohen S, Shi Y. Peripancreatic paraganglioma mimics pancreatic/gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor on fine needle aspiration: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:947–952. doi: 10.1002/dc.23761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, Itagaki E, Katabami T, Kakoi N, Rakugi H, Ikeda Y, Tanabe A, Nigawara T, Ito S, Kimura I, Naruse M Phaeochromocytoma Study Group in Japan. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405–414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Li M, Deng H, Pang Y, Liu L, Guan X. The systems of metastatic potential prediction in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:769–780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam AK. Update on Paragangliomas and Pheochromocytomas. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31 Suppl 1:105–112. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2015.01318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Ding Y, Wei L, Zhao D, Wang R, Zhang Y, Gu X, Wang Z. Recurrent Olfactory Neuroblastoma Treated With Cetuximab and Sunitinib: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3536. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintás-Cardama A, Manshouri T, Estrov Z, Harris D, Zhang Y, Gaikwad A, Kantarjian HM, Verstovsek S. Preclinical characterization of atiprimod, a novel JAK2 AND JAK3 inhibitor. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:818–826. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9429-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacConaill LE, Garcia E, Shivdasani P, Ducar M, Adusumilli R, Breneiser M, Byrne M, Chung L, Conneely J, Crosby L, Garraway LA, Gong X, Hahn WC, Hatton C, Kantoff PW, Kluk M, Kuo F, Jia Y, Joshi R, Longtine J, Manning A, Palescandolo E, Sharaf N, Sholl L, van Hummelen P, Wade J, Wollinson BM, Zepf D, Rollins BJ, Lindeman NI. Prospective enterprise-level molecular genotyping of a cohort of cancer patients. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohara Y, Oda T, Hashimoto S, Akashi Y, Miyamoto R, Enomoto T, Satomi K, Morishita Y, Ohkohchi N. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor and solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm: Key immunohistochemical profiles for differential diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:8596–8604. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbasi A, Wakeman KM, Pillarisetty VG. Pancreatic paraganglioma mimicking pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Rare Tumors. 2020;12:2036361320982799. doi: 10.1177/2036361320982799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhi AD, Hruban RH, Fabre M, Imura J, Schulick R, Wolfgang C, Ali SZ. Peripancreatic paraganglioma: a potential diagnostic challenge in cytopathology and surgical pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1498–1504. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182281767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Tu Z, Lv Z, Luo Y, Yuan J. Case Report: Totally Laparoscopic Resection of Retroperitoneal Paraganglioma Masquerading as a Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Front Surg. 2021;8:586503. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.586503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Peng L, Huang S, Li Y, Xiao W. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:19. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0771-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: updates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1272–1284. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1272-PAEPU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura N, Takekoshi K, Naruse M. Risk Stratification on Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma from Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. J Clin Med. 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/jcm7090242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]