Abstract

Introduction

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb) infection, the most frequent tick-transmitted disease, is distributed worldwide. This study aimed to describe the global seroprevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of Bb in human populations.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and other sources for relevant studies of all study designs through 30 December 2021 with the following keywords: ‘Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato’ AND ‘infection rate’; and observational studies were included if the results of human Bb antibody seroprevalence surveys were reported, the laboratory serological detection method reported and be published in a peer-reviewed journal. We screened titles/abstracts and full texts of papers and appraised the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration-endorsed Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. Data were synthesised narratively, stratified by different types of outcomes. We also conducted random effects meta-analysis where we had a minimum of two studies with 95% CIs reported. The study protocol has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021261362).

Results

Of 4196 studies, 137 were eligible for full-text screening, and 89 (158 287 individuals) were included in meta-analyses. The reported estimated global Bb seroprevalence was 14.5% (95% CI 12.8% to 16.3%), and the top three regions of Bb seroprevalence were Central Europe (20.7%, 95% CI 13.8% to 28.6%), Eastern Asia (15.9%, 95% CI 6.6% to 28.3%) and Western Europe (13.5%, 95% CI 9.5% to 18.0%). Meta-regression analysis showed that after eliminating confounding risk factors, the methods lacked western blotting (WB) confirmation and increased the risk of false-positive Bb antibody detection compared with the methods using WB confirmation (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.6 to 2.2). Other factors associated with Bb seropositivity include age ≥50 years (12.6%, 95% CI 8.0% to 18.1%), men (7.8%, 95% CI 4.6% to 11.9%), residence of rural area (8.4%, 95% CI 5.0% to 12.6%) and suffering tick bites (18.8%, 95% CI 10.1% to 29.4%).

Conclusion

The reported estimated global Bb seropositivity is relatively high, with the top three regions as Central Europe, Western Europe and Eastern Asia. Using the WB to confirm Bb serological results could significantly improve the accuracy. More studies are needed to improve the accuracy of global Lyme borreliosis burden estimates.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021261362.

Keywords: epidemiology; medical microbiology; infections, diseases, disorders, injuries; cross-sectional survey; descriptive study

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb) infection, the most frequent tick-transmitted disease in Europe and North America, is distributed worldwide.

The Northern Hemisphere residents have the highest Lyme borreliosis (LB, also as Lyme disease) burden, but no consensus exists regarding the reported global seroprevalence and specific risk factors of Bb infection.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This systematic review and meta-analysis of the literatures addressed this knowledge gap.

Reported seroprevalence was highest in the LB-like symptoms population and lowest in the general population.

Meta-regression analyses showed that the reported pooled Bb seroprevalence of studies using methods confirmed by western blotting (WB) was lower than that of studies using methods not confirmed by WB after eliminating confounding risk factors.

Potential risk factors associated with Bb infection were male sex, age >40 years, residence in rural area and suffering tick bites.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

We confirmed that results confirmed by WB are more reliable than those not confirmed by WB when assessing human Bb infection.

Using WB to confirm Bb serological results could significantly improve the accuracy.

For risk factors, male sex, age >40 years, residence in rural areas, and suffering tick bites might increase the risk of Bb infection.

We provided a more accurate characterizationcharacterisation of the global distribution and sociodemographic factors of Bb infection, which would guide the global epidemiology of LB and identify risk factors for the disease, and could inform the development of public health response policies and LB control programsprogrammes.

Introduction

Lyme borreliosis (LB, also called Lyme disease) is caused by the tickborne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb). The complex biology and multiple immune escape mechanisms of LB make it the most common vectorborne disease in temperate North America, Europe and Asia.1–3 The most common clinical manifestation of LB is migrating erythema (an enlarged erythema on the skin, usually at the site of a tick bite), and the infecting agent can spread to other tissues and organs, resulting in manifestations that can involve the nervous system, joints, heart and skin.4 LB has continued to spread globally in recent years as a chronic, multisystemic vectorborne disease.5 Such vectorborne diseases, which are characterised by specificity of geographical distribution and frequent emergence and introduction of pathogens, pose a significant and growing public health problem and are major causes of disease and death worldwide.5 A strong worldwide push for continuous surveillance (including global epidemiological surveys of LB), diagnosis and control of vectors of tickborne diseases is essential for the development of effective new LB treatments and prevention methods.

Bb is one of several extracellular pathogens capable of establishing a persistent infection in mammals, and laboratory diagnosis of LB depends on the detection of IgM and IgG antibodies against Bb, the causative agent of the disease.6 7 Several laboratory tests are available for the diagnosis of LB, including serological, microscopic and molecular-based methods.8 Standard two-stage tests (STTT) based on immunoblotting (, ELISA or indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assay followed by immunoblot confirmation) currently serve as the primary supports for the laboratory diagnosis of LB and assessment of disease development.9 10 Positive serological reactions indicating the presence of anti-Bb IgM or IgG reflect active or previous infection, respectively.11 12

This review provides the first meta-analysis of literature regarding seropositivity to anti-Bb antibodies in different countries and among different populations worldwide aimed at enhancing understanding of the global epidemiology of LB over the last 36 years. In addition, the detection of different antibodies is compared and analysed based on two different serological testing protocols. Finally, the distribution of Bb seropositivity rates is discussed in conjunction with analyses of potential risk factors, including population categories (general population, defined high-risk population, tick-bitten population and LB-like symptoms population), population characteristics (sex, age, geographical residence, tick bite status), geographical factors (continental plates), testing methods and publication year in order to identify factors associated with Bb seropositivity.

Methods

This article was prepared according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (2020) guidelines (detailed in online supplemental appendix 1) and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021261362).

bmjgh-2021-007744supp001.pdf (19.7MB, pdf)

Search strategy

We performed systematic, internet-based searches using the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and the grey literature abstract databases with the following keywords: ‘Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato’ OR ‘Lyme Disease Spirochete’ OR ‘Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto’ AND ‘infection rate’ OR ‘prevalence’ OR ‘seroprevalence’ OR ‘serological survey’ OR ‘sero-prevalence’ OR ‘seroepidemiology’ OR ‘sero-epidemiology’. The search was not limited by language; reports not written in English were translated using Google Translate or by colleagues proficient in that language. To minimise publication bias, reference lists of included studies were manually retrieved and searched for grey literature that met our inclusion criteria. If data were missing, we contacted the corresponding authors of the relevant studies. The search was carried out between January 1984 and December 2021 (detailed in online supplemental appendix 2).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) samples were human serum; (b) laboratory serological detection methods with the following standard laboratory tests for identifying Bb, including conventional serological methods such as ELISA, IFA test, protein biochip, chemiluminescence immunoassay, passive haemagglutination assays, line blot and western blotting (WB); laboratory molecular detection methods used as additional detection methods in some studies: PCR, real-time PCR, PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism and sequencing assays; (c) results of human studies including Bb antibody seroprevalence surveys; (d) original articles presenting surveillance reports or cross-sectional or case–control or cohort studies.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) animal/insect studies (eg, ticks, sheep, cattle, dogs, etc); (b) serological Bb antibody detection method not described or detection methods did not match description; (c) incomplete data (eg, only reported total Bb seroprevalence while the total number of participants was not indicated or geographical information and population categories not described) and studies lacking primary data (eg, full-text study was not found); (d) systematic review, meta-analysis, conference presentation, case report, repeated publication (the highest quality publication was retained). This phase involved a group of three reviewers (YD, WC and YZ) who independently catalogued all reports using the set criteria. Outcome of this initial categorisation was then crosschecked by a different reviewer within this group to ensure its accuracy with a 90% level of agreement (detailed in online supplemental appendix 3).

Data screening and extraction

Data extraction was assessed independently, with conflicts of opinion and uncertainties discussed and resolved by consensus with third-party reviewers (YD, JC and GZ). Data were extracted from each included study and entered into a database. Data pertaining to the first author, publication year period, country, area of residence, serological screening test used, population categories, sex, age, sample size, tick bite, and number of seropositive results, type of antibody and other relevant information were extracted.

Risk of bias

Full-text papers were obtained for all identified potential reports for detailed risk of bias assessment (by YD, JK and WC), and assessment inconsistencies were discussed and disagreements resolved by consensus. Data quality scores were rated with the Cochrane Collaboration-endorsed Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, which was specifically designed to assess aspects of population-based studies of prevalence.13 14 The assessment was based on three main criteria relating to (a) selection bias, (b) confounding, and (c) outcome measurement bias. The checklist included seven items, each option as ‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’ or ‘d’. The assessment options correspond to a ‘star system’ that allows us to rate the overall quality (low, moderate or high) after assessing the risk of bias in the three main criteria. Option scoring ‘**’ received 20% scores; option scoring ‘*’ received 10% scores; others received 0 point. Thus, final scores for each study could range from 0% to 100%: studies with a score of 0%–49% were defined as low quality; those with a score of 50%–69% were considered moderate quality; and those with a score of 70%–100% were deemed high quality. Studies with a score of ≥50% were included in the final analysis (detailed in online supplemental appendix 4).

Data synthesis and analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted using the ‘meta’ package in R (V.4.0.5) to estimate Bb seroprevalence. A random effects model was used to calculate the reported pooled seroprevalence. An I2 value of more than 50% was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity, and more than 75% was considered to indicate high heterogeneity. The global seropositivity rate was calculated, as this was the objective of the study. For each reported seroprevalence, an exact binomial 95% CI was calculated. Significant differences in estimated seroprevalence between pairs of risk factors for Bb seroprevalence were evaluated based on 95% CIs. Differences were considered statistically significant if the 95% CIs did not overlap.

Overall, heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 test, and seroprevalence estimates were stratified by population category (general, high-risk, tick-bitten, LB-like symptoms) and other potential risk factors (sex, age, years of publication, continent, country, tick bites, residence, serological screening test used), as these variables were considered a priori potential predictors of Bb seroprevalence.15 The effect of heterogeneity on seroprevalence estimates was examined by subgroup and meta-regression analyses. Reported pooled ORs and 95% CIs were calculated from raw data of the included studies using the random effects model, and reported subgroup pooled ORs were generated for different risk factors. Logit transformation, arcsine transformation and Freeman-Tukey methods (different methods used for proportion meta-analyses) were compared via sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was detected using Egger’s test and funnel plots.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement statement is not applicable in this paper since the patients or the public were not involved in either the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Search results and eligible studies

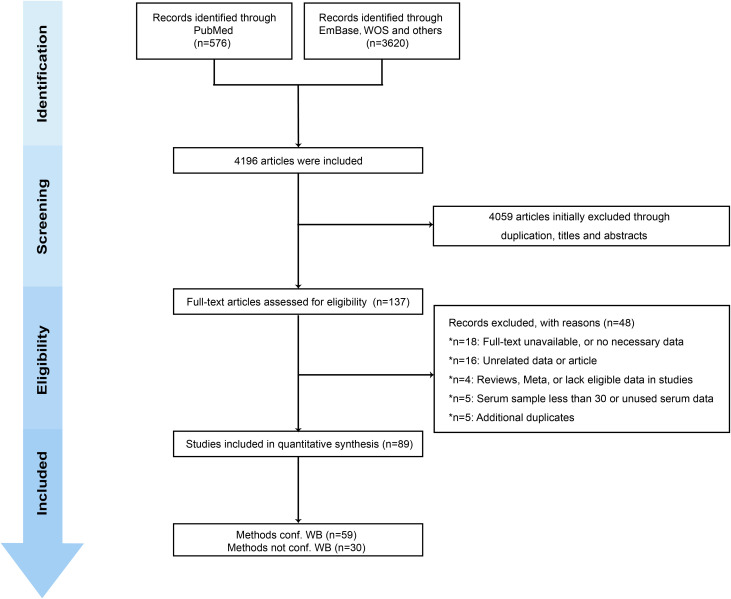

We retrieved 4196 studies from three databases (the PubMed, Embase and Web of Science abstract databases) and grey literatures. A total of 89 observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort, case–control studies) that met inclusion requirements were included after full-text review (online supplemental appendix 5).16–104 The studies involved 158 287 participants, and the reported estimated Bb seroprevalence was 14.5% (95% CI 12.8% to 16.3%). Details regarding article screening procedures and reasons for exclusion are summarised in figure 1. According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, the 89 studies were graded as moderate to high quality. Online supplemental appendix 6 presents the details of the risk of bias assessment.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of search strategy for selecting eligible studies. conf WB, confirmatory western blotting.

Meta-analysis of global Bb seroprevalence

The reported pooled seroprevalence was 14.5% (95% CI 12.8% to 16.3%) according to the random effects model (online supplemental appendix 7). Of the 89 studies, 31 lacked WB confirmation of serological testing, and 58 had WB confirmation, with reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates of 16.3% (95% CI 13.8% to 18.9%) and 11.6% (95% CI 9.5% to 14.0%), respectively (online supplemental appendix 8).

Forty of the included studies were unique, in that they documented the results of serological testing techniques with/without WB confirmation in the same cohort, thus allowing a better comparison of the two methods for determining Bb seropositivity. The reported pooled Bb seropositivity was 17.5% (95% CI 14.2% to 21.0%) without WB confirmation and 9.8% (95% CI 7.5% to 12.3%) with WB confirmation (online supplemental appendix 9). The two methods were also compared after eliminating confounding risk factors such as sex, age, specified antibody type (IgM/IgG/IgM+IgG), publication year period, tick bite history, population category and residence region (rural/urban) (table 1, figure 2). Our results suggested that using only one-step methods such as ELISA/IFA to determine Bb seropositivity has limitations and that serological testing for Bb seropositivity with WB confirmation is more reliable. These results further support the use of standard two-stage testing (STTT, ELISA or IFA assay followed by WB confirmation) as a more reliable means of supporting the laboratory diagnosis of LB and assessing its development.

Table 1.

Meta-regression analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato seroprevalence determined using methods confirmed by WB and methods not confirmed by WB after eliminating confounding risk factors

| Methods conf WB | Methods not conf WB | Random effects model OR (95% CI) |

P value | Cohort | |

| Overall | 9.8% (7.5%; 12.3%) | 17.5% (14.2%; 21.1%) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.2) | <0.0001 | 38 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 5.1% (3.5%; 7.1%) | 10.4% (7.1%; 14.2%) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 0.0002 | 14 |

| Male | 5.4% (2.6%; 9.2%) | 11.1% (5.1%; 18.9%) | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.8) | 0.0055 | 7 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <40 | 8.1% (3.7%; 14.0%) | 15.9% (8.2%; 25.6%) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.19) | 0.0030 | 6 |

| 40–49 | 6.2% (0.0%; 26.4%) | 18.0% (2.6%; 43.1%) | 2.4 (1.6 to 3.6) | <0.0001 | 2 |

| ≥50 | 8.8% (1.2%; 22.6%) | 18.0% (7.2%; 32.4%) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.4) | <0.0001 | 6 |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 9.5% (3.6%; 17.7%) | 13.4% (3.1%; 29.3%) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | 0.0082 | 3 |

| Urban | 5.3% (1.0%; 12.8%) | 8.9% (0.8%; 24.6%) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) | 0.0451 | 3 |

| Tick bites | |||||

| Not suffering | 3.2% (0.8%; 6.9%) | 14.3% (8.7%; 20.9%) | 4.5 (1.6 to 12.9) | 0.0052 | 1 |

| Suffering | 16.2% (4.6%; 33.1%) | 38.0% (2.7%; 67.5%) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.0) | 0.0215 | 4 |

| Different continents | |||||

| Europe | 10.3% (7.5%; 14.1%) | 17.2% (11.7%; 23.8%) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | <0.0001 | 12 |

| America | 4.1% (0.7%; 10.1%) | 10.6% (6.7%; 15.4%) | 3.8 (1.9 to 7.6) | 0.0001 | 6 |

| Asia | 6.6% (3.3%; 10.9%) | 13.8% (8.2%; 20.6%) | 2.3 (1.7 to 3.1) | <0.0001 | 10 |

| Different populations | |||||

| General | 5.3% (3.7%; 7.3%) | 9.7% (7.5%; 12.1%) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.3) | <0.001 | 22 |

| High risk | 10.9% (6.6%; 16.2%) | 22.0% (16.1%; 28.7%) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | <0.001 | 12 |

| Tick bitten | 16.2% (4.6%; 33.1%) | 38.0% (12.7%; 67.5%) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.0) | 0.0215 | 4 |

| LB-like symptoms | 18.9% (10.7%; 28.7%) | 26.5% (14.6%; 40.6%) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 0.007 | 6 |

| Antibodies | |||||

| IgG | 7.8% (4.8%; 11.4%) | 12.8% (7.8%; 18.9%) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | <0.001 | 12 |

| IgM | 4.2% (2.7%; 5.9%) | 12.2% (9.2%; 15.4%) | 3.1 (2.1 to 4.4) | <0.001 | 12 |

| IgG+IgM | 0.2% (0.0%; 0.7%) | 2.2% (0.4%; 5.4%) | 4.8 (2.0 to 11.5) | <0.001 | 3 |

| Two time periods | |||||

| 2001–2010 | 7.1% (3.6%; 11.6%) | 14.3% (11.2%; 17.7%) | 2.5 (1.4 to 4.4) | 0.0017 | 9 |

| 2011–2021 | 10.1% (7.3%; 13.4%) | 17.9% (13.8%; 22.4%) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) | <0.001 | 26 |

Methods conf WB group was considered the reference group when conducting meta-regression analysis.

LB, Lyme borreliosis; WB, western blotting.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of specific anti-IgG and anti-IgG antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato among extracted studies that reported seropositivity confirmed by western blotting (WB) relative to seropositivity not confirmed by WB.

Based on the above results, the 58 studies that used WB confirmation to determine Bb seropositivity were used to analyse factors predictive of Bb infection, as our data showed Bb seropositivity results were more reliable with WB confirmation. Therefore, a subgroup analysis of the data from the 58 studies was conducted to survey possible predictors for Bb infection. The 58 selected articles were published between 1999 and 2021 and conducted in 28 countries from the Americas (5), Europe (17), Asia (4), Australia (1) and the Caribbean region (1).

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis was performed according to possible predictors of LB. By gender, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates were 5.3% (95% CI 3.2% to 8.0%) for females and 7.8% (95% CI 4.6% to 11.9%) for males. By age, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates were 7.1% (95% CI 5.1% to 9.5%) for those 0–39 years of age, 10.1% (95% CI 4.6% to 17.6%) for those 40–49 years of age and 12.6% (95% CI 8.0% to 18.1%) for those ≥50 years of age. By place of residence, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates were 8.4% (95% CI 5.0% to 12.6%) for rural populations and 5.4% (95% CI 3.2% to 8.1%) for urban populations. According to tick bite history, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates were 18.8% (95% CI 10.1% to 29.4%) for the tick-bitten population and 10.5% (95% CI 2.1% to 24.3%) for those not tick bitten. For the four population categories, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rate in the general population was 5.7% (95% CI 4.3% to 7.3%), which was significantly lower than the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rate of 14.7% (95% CI 9.9% to 20.2%) for the high-risk population, 18.8% (95% CI 10.1% to 29.4%) for the tick-bitten population and 21.3% (95% CI 14.1% to 29.4%) for the LB-like symptoms population. Two time periods (2001–2010 and 2011–2021) were examined to analyse the Bb prevalence trend over time. The Bb prevalence after 2011 was higher than that before, with the Bb seropositivity rate increasing from 8.1% (95% CI 5.7% to 10.8%) to 12.2% (95% CI 9.6% to 15.0%) (table 2). Depending on the continental plate, the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rates for the Americas, Europe, the Caribbean, Asia and Oceania (only Australia reported) were 9.4% (95% CI 3.5% to 17.7%), 13.5% (95% CI 10.9% to 16.3%), 2.0% (95% CI 0.6% to 4.1%), 7.4% (95% CI 3.7% to 12.2%) and 4.1% (95% CI 0.0% to 14.1%), respectively (table 3). Forest plots of pooled Bb prevalence stratified by subgroup are shown in online supplemental appendices 10–23. The compositions of the four population cohorts in each region are summarised in figure 3. The reported pooled seropositivity rate is summarised by cohort according to region and population group in figure 4.

Table 2.

Meta-regression analysis of the potential risk factors associated with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb) infection in 58 included studies determining Bb seroprevalence confirmed by WB

| Risk factor | Cohort | Seroprevalence (95% CI) | Random effects model OR (95% CI) |

P value | Cohort |

| Overall | 58 | 11.5% (9.4% to 13.8%) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 20 | 5.5% (3.2% to 8.0%) | Reference | 18 | |

| Male | 20 | 7.8% (4.6% to 11.9%) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.9) | 0.001 | 18 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| <40 | 18 | 7.1% (5.1% to 9.5%) | Reference | 9 | |

| 40–49 | 5 | 10.1% (4.6% to 17.6%) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.6) | 0.049 | 5 |

| ≥50 | 14 | 12.6% (8.0% to 18.1%) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.7) | <0.001 | 9 |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 9 | 8.4% (5.0% to 12.6%) | Reference | 8 | |

| Urban | 9 | 5.4% (3.2% to 8.1%) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.002 | 8 |

| Tick bites | |||||

| Not suffering | 10 | 10.5% (2.1% to 24.3%) | Reference | 5 | |

| Suffering | 5 | 18.8% (10.1% to 29.4%) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.2) | 0.036 | 5 |

| Different continents | |||||

| Europe | 35 | 14.0% (11.2% to 17.0%) | |||

| America | 10 | 9.4% (3.5% to 17.7%) | |||

| Asia | 10 | 7.4% (3.7% to 12.2%) | |||

| Caribbean | 1 | 2.0% (0.6% to 4.1%) | |||

| Different populations | |||||

| General | 35 | 5.7% (4.3% to 7.3%) | Reference | 8 | |

| High risk | 22 | 14.7% (9.9% to 20.2%) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.2) | <0.001 | 7 |

| Tick bitten | 10 | 18.8% (10.1% to 29.4%) | 2.5 (1.7 to 3.8) | <0.001 | 2 |

| LB-like symptoms | 13 | 21.3% (14.1% to 29.4%) | 5.8 (2.7 to 13.6) | <0.001 | 2 |

| Methods | |||||

| Methods not conf WB | 41 | 16.3% (13.8% to 18.9%) | Reference | 36 | |

| Methods conf WB | 40 | 11.6% (9.5% to 14.0%) | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | <0.001 | 36 |

| Two time periods | |||||

| 2001–2010 | 12 | 8.1% (5.7% to 10.8%) | |||

| 2011–2021 | 45 | 12.2% (9.6% to 15.0%) |

LB, Lyme borreliosis; WB, western blotting.

Table 3.

Range of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb) seroprevalence in five populations from different continents

| Continent | General population | High-risk population | Tick-bitten population | LB-like symptoms population | All |

| America | |||||

| North America | 1.2% (0.0%–5.4%) | 27.8% (4.6%–60.8%) | 30.4% (0.9%–77.2%) | 14.2% (12.4%–16.2%) | 9.4% (2.6%–19.8%) |

| South America | – | 4.6% (1.9%–8.5%) | – | 12.2% (1.8%–29.9%) | 8.7% (3.2%–16.6%) |

| Europe | |||||

| Southern Europe | 4.4% (2.1%–6.8%) | 12.3% (6.4%–16.9%) | – | – | 11.1% (5.2%–18.8%) |

| Western Europe | 7.5% (5.2%–10.1%) | 13.1% (1.7%–32.7%) | 23.2% (6.1%–46.9%) | 47.9% (34.3%–61.6%) | 13.5% (9.5%–18.0%) |

| Northern Europe | 8.6% (5.3%–12.6%) | 9.3% (7.6%–11.1%) | 3.2% (1.6%–5.4%) | 14.3% (5.5%–26.3%) | 7.6% (4.3%–11.7%) |

| Eastern Europe | 4.8% (3.4%–6.5%) | – | 10.7% (7.8%–13.9%) | 35.5% (27.3%–44.1%) | 10.4% (5.3%–16.9%) |

| Central Europe | 10.9% (8.8%–13.2%) | 35.7% (23.0%–49.4%) | 5.5% (2.2%–10.1%) | 11.2% (6.6%–16.8%) | 20.7% (13.8%–28.6%) |

| Asia | |||||

| Eastern Asia | – | 22.5% (14.1%–32.2%) | 71.4% (46.0%–91.2%) | 11.1% (7.5%–15.7%) | 15.9% (6.6%–28.3%) |

| Southern Asia | – | 3.0% (1.6%–4.7%) | – | – | 3.0% (1.6%–4.7%) |

| Western Asia | 5.2% (1.5%–10.9%) | 7.8% (1.6%–18.2%) | 17.1% (9.5%–26.3%) | – | 6.3% (2.3%–12.2%) |

| Caribbean | – | 2.0% (0.6%–4.1%) | – | – | 2.0% (0.6%–4.1%) |

| Oceania | 0.0% (0.0%–21.5%) | – | – | – | 4.1% (0.4%–15.4%) |

| All | 5.7% (4.3%–7.3%) | 14.7% (9.7%–19.5%) | 18.8% (10.1%–29.4%) | 21.3% (14.1%–29.4%) | 11.3% (9.2%–13.6%) |

LB, Lyme borreliosis.

Figure 3.

Distribution of included samples by population category and WHO region. AMR, Region of the Americas; AR, Asian Region; EUR, European Region; LB, Lyme borreliosis.

Figure 4.

Estimated western blotting (WB)-based Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb) seroprevalence in different groups of human populations in reported countries. Different colours represent different groups of people and their disease severity, and grey areas represent countries reporting no Bb seroprevalence in humans. (A) General population. (B) High-risk population. (C) Tick-bitten population. (D) Lyme borreliosis (LB)-like symptoms population.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses involved omitting each study in turn and comparing the reported pooled Bb seropositivity rate using an inverse sine transformation. After omitting each study in turn, the reported pooled seropositivity rate of the remaining studies was approximately 12%, indicating that the meta-analysis results were robust and reliable (online supplemental appendix 24).

Meta-regression

To assess potential sources of heterogeneity, a random effects model meta-regression analysis was conducted, which revealed significant heterogeneity with pooled analyses (online supplemental appendix 25) (I2=0.99; p<0.001).

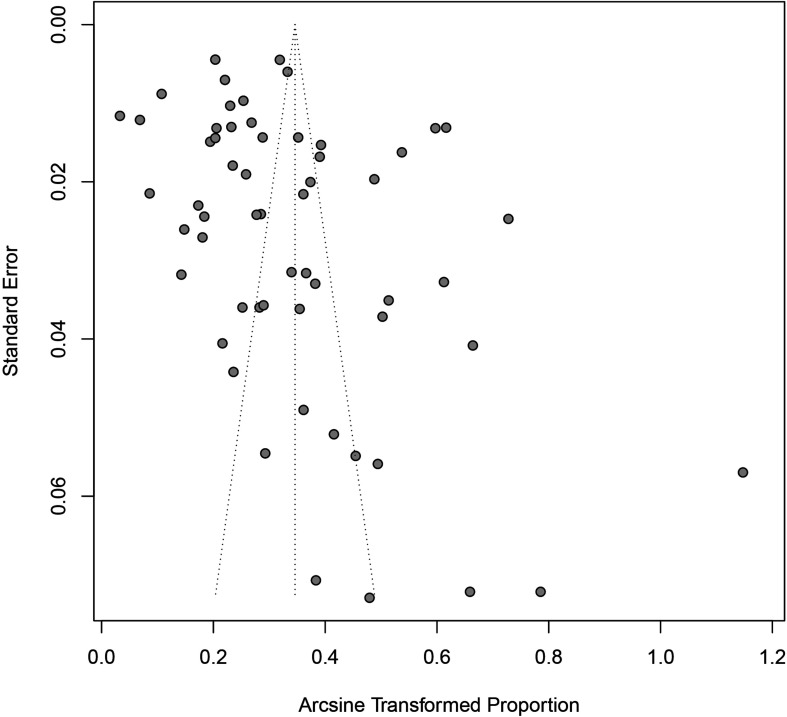

Publication bias

The Egger’s test and a funnel plot were constructed to assess publication bias. According to the Egger’s test, the p value was 0.04, and the funnel plot was clearly asymmetric; thus, the review had some publication bias (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Publication bias result of funnel plot.

Discussion

Bb is a zoonotic tickborne spirochete and pathogen of LB.105 Since its identification in 1975, LB has become the most common tickborne zoonotic disease worldwide.106 107 The incidence and distribution of LB have increased over the last four decades.108 Therefore, there is a need for preventive measures, which necessitates understanding the dynamics of tickborne disease transmission and the lack of effective disease prevention strategies to reduce the risk of contracting the disease.109 This is the most comprehensive and up-to-date systematic review of the worldwide seroprevalence of Bb. We estimated a reported global seroprevalence of 14.5% (95% CI 12.8% to 16.3%) and confirmed wide variation in Bb prevalence between regions and countries, with the reported prevalence highest in Central Europe (20.7%), followed by Eastern Asia (15.9%), Western Europe (13.5%) and Eastern Europe (10.4%). In contrast, the reported prevalence was lowest in the Caribbean (2.0%), Southern Asia (3.0%) and Oceania (5.3%).

The global seroprevalence rates assessed in our meta-analysis should be considered preliminary estimates because of the large heterogeneity of the included studies. After stratification by potentially important predictors (eg, population category, continental distribution, detection test), heterogeneity across populations, continents and detection methods remained high. No specific sources of heterogeneity were identified by various means (subgroup, sensitivity or meta-regression analyses). The high heterogeneity after specified stratification suggests that (1) heterogeneity could be due to the limited data, indicating that more data are needed to address heterogeneity and obtain more globally representative estimates of Bb prevalence; or (2) heterogeneity could be due to other possible sources: differences in study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, population size, recruitment/sampling methods, test kits.

Furthermore, the publication bias of the included studies should not be overlooked. First, in areas where LB is endemic, clinicians routinely use the Bb antibody test and are therefore more likely to report higher seropositivity rates relative to LB-non-endemic areas; thus, the reported seropositivity rate in the general population may be overestimated and non-representative of the global population. Second, whether the study’s sample size was representative of the region’s total population and whether small samples were used for estimation could have impacts that cannot be ignored. The funnel plot and Egger’s test results showed some publication bias in this review, so the global seroprevalence that we assessed should be considered a preliminary estimate. The population was therefore divided into four subpopulations (general, high-risk, tick-bitten and LB-like symptoms populations), and each analysed separately.

Jointly improving and standardising testing methods is of great value in providing accurate epidemiological data on LB and identifying potential risk factors for LB. The possibility of false-positive cross-reactivity with pathogens of other infectious diseases (eg, Epstein-Barr virus) in one-step tests such as ELISA has been reported.9 110 The reported pooled prevalence rate in this study was based primarily on WB-confirmed results due to concerns over results comparability and reliability. This conclusion was based on our results after comparing the seroprevalence of WB-confirmed and non-WB-confirmed results; the seropositivity rate with WB confirmation, which exhibited high consistency after excluding confounding factors, was more reliable than that without WB confirmation. These results suggest that WB confirmation could reduce false positivity to some degree and improve specificity. However, WB confirmation has limitations, such as low sensitivity of serological assays in the early stages of Bb infection,111 the subjectivity and complexity of the techniques associated with secondary immunoblotting and high relative expense.112 Other improved secondary serological assays (eg, whole-cell ultrasound enzyme immunoassay (EIA)+C6 EIA)113 and molecular diagnostics (eg, next-generation sequencing)113 are developing rapidly, which could improve LB diagnosis.

To identify potential risk factors associated with anti-Bb antibody positivity, we conducted meta-regression analyses according to reported demographic characteristics for the 58 studies confirmed by WB. Our limited results showed that the prevalence of people who suffered tick bites was higher than that of those not suffering from tick bites. The high-risk population was defined in terms of occupation (farmers, skilled and unskilled workers, police officers, soldiers, housewives and retirees),15 and the specificity of these occupations has greatly increased the exposure to ticks and intermediate host animals (eg, dogs, sheep) related to LB. The general, high-risk, tick bite and LB-like symptoms populations showed a progressive increase in seropositivity over time. Numerous investigations have shown that the prevalence of tickborne diseases has doubled in the last 12 years.114 Our results indicate that the prevalence of Bb in 2010–2021 was higher than that in 2001–2010. LB is the most prominent tickborne disease, and tick populations (carriers of microbial pathogens second only to mosquitoes) have expanded globally and geographically in recent years, thereby greatly increasing the risk of human exposure to ticks.115 This may be related to ecological changes and anthropogenic factors, such as longer summers and warmer winters, changes in precipitation during dry months, animal migration, fragmentation of arable land and forest cover due to human activities and the prevalence of outdoor activities (eg, more time spent in public green spaces and increasingly frequent pet contact).116 117

In addition, our limited results regarding gender showed that the higher seropositivity rate in men relative to women was closely associated with the greater likelihood of males to engage in high-risk occupations. Older age is also a risk factor. Regarding residence, seropositivity rates were higher in rural than urban areas, suggesting that residence in rural areas is a risk factor of Bb infection, and other studies have reported increases in the proportion of seropositivity in urban populations over time, highlighting the need to raise awareness of Bb pathogens in cities.118 We believe that these differences may have a predictive value for assessing Bb risk factors as more data become available.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, due to the limited data, few studies were conducted with longitudinal follow-up, and it was not possible to systematically assess whether Bb antibody positivity has any long-term effect on the risk of developing LB or the risk of recurrence. Second, the heterogeneity of the included studies was high, and most of the reports lacked important information, such as exact definitions of high-risk groups, the inclusion of subjects with suspicious LB symptoms and no indication regarding whether random sampling was used, which may lead to heterogeneity. We did not identify specific sources of heterogeneity via subgroup, sensitivity or meta-regression analyses; thus, ongoing monitoring is needed to generate more data to address sources of heterogeneity and obtain more globally representative estimates. Third, our extraction of potential risk factors may be incomplete because not all studies reported demographic characteristics, which may have resulted in small sample sizes for some subgroups analysed, making estimates for those subgroups inaccurate. Fourth, secondary WB results for LB detection varied depending on the primary immunological method used, serum concentration, antigen type (eg, OspC-I, C6VlsE, circulating immune complex), antigen concentration, antibody type (eg, IgG, IgM), secondary antibody concentration and subjective judgement ability.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review provides a global estimate of the epidemiology of Bb infection in humans. With a high reported pooled seropositivity rate in the total population, Bb infection was most common in Europe. Subgroup analysis showed that the pooled seroprevalence increased steadily in these four subpopulations (the general population, the high-risk population, the tick-bitten population and the LB-like symptoms population). This report further elaborates on the public health implications of the increasing prevalence of Bb infection. We confirmed that results confirmed by WB are more reliable than those not confirmed by WB when assessing human Bb infection. For risk factors, male sex, age >40 years, residence in rural areas and suffering from tick bites might increase the risk of Bb infection. However, future studies should be undertaken to verify these conclusions. LB is a widely distributed infectious disease, but it has not received much attention worldwide. One of the major public health challenges regarding LB is the ability to predict when and where there is a risk of Bb infection. A more accurate characterisation of the global distribution of Bb infection would guide the circulating epidemiology of LB and identify risk factors for the disease, which could inform the development of public health response policies and LB control programmes.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Senjuti Saha

Contributors: BFK, guarantor. BFK, LAH, and DY conceived and designed the study. DY, CWJ, and ZY conducted the database search and screening. DY, CJJ, and ZGZ extracted the data. DY, KJ, and CWJ conducted the quality assessment. DY, YJR, JZH, and ZGZ conducted the analysis in conjunction with XX, CWJ and FXY. DY, LMX, WSY, YP and LBX interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. BFK and LAH revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 32060180, 82160304, 81860644, 81560596 and 31560051) and the Joint Foundation of Yunnan Province Department of Science and Technology-Kunming Medical University (No 2019FE001 (2019FE002) and 2017FE467 (2017FE001)) and the Science Research Fund Project of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education (2021Y323).

Disclaimer: The funding institutions had no involvement in the design of the study or review of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Branda JA, Steere AC. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2021;34:e00018–19. 10.1128/CMR.00018-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joung HA, Ballard ZS, Wu J. Point-of-care serodiagnostic test for early-stage Lyme disease using a multiplexed paper-based immunoassay and machine learning. ACS Nano 2020;14:229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kilpatrick AM, Dobson ADM, Levi T, et al. Lyme disease ecology in a changing world: consensus, uncertainty and critical gaps for improving control. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017;372:20160117. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis-from tick bite to diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2018;42:233–58. 10.1093/femsre/fux047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital signs: trends in reported vector-borne disease cases–United States and Territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:496–501. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernard Q, Smith AA, Yang X, et al. Plasticity in early immune evasion strategies of a bacterial pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E3788–97. 10.1073/pnas.1718595115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. D'Arco C, Dattwyler RJ, Arnaboldi PM. Borrelia burgdorferi-specific IgA in Lyme disease. EBioMedicine 2017;19:91–7. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodino KG, Theel ES, Pritt BS. Tick-borne diseases in the United States. Clin Chem 2020;66:537–48. 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Branda JA, Body BA, Boyle J, et al. Advances in serodiagnostic testing for Lyme disease are at hand. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:1133–9. 10.1093/cid/cix943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pegalajar-Jurado A, Schriefer ME, Welch RJ. Evaluation of modified two-tiered testing algorithms for Lyme disease laboratory diagnosis using well-characterized serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 2018;56:e01943–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Renzi S, Martini A, Binazzi A. Risk of acquiring tick-borne infections in forestry workers from Lazio, Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:1579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Snyder JL, Giese H, Bandoski-Gralinski C, et al. T2 magnetic resonance assay-based direct detection of three Lyme disease-related Borrelia species in whole-blood samples. J Clin Microbiol 2017;55:2453–61. 10.1128/JCM.00510-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, 2021. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 14. Stockdale AJ, Kreuels B, Henrion MYR, et al. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2020;73:523–32. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cora M, Kaklıkkaya N, Topbaş M, et al. Determination of seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi IgG in adult population living in Trabzon. Balkan Med J 2017;34:47–52. 10.4274/balkanmedj.2015.0478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith RP, Elias SP, Cavanaugh CE, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, B. miyamotoi, and Powassan Virus in Residents Bitten by Ixodes Ticks, Maine, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2019;25:804–7. 10.3201/eid2504.180202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Best SJ, Tschaepe MI, Wilson KM. Investigation of the performance of serological assays used for Lyme disease testing in Australia. PLoS One 2019;14:e214402. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pascoe EL, Stephenson N, Abigana A, et al. Human Seroprevalence of Tick-Borne Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Rickettsia Species in Northern California. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2019;19:871–8. 10.1089/vbz.2019.2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brummitt SI, Kjemtrup AM, Harvey DJ, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia miyamotoi seroprevalence in California blood donors. PLoS One 2020;15:e243950. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lipsett SC, Branda JA, Nigrovic LE. Evaluation of the modified two-tiered testing method for diagnosis of Lyme disease in children. J Clin Microbiol 2019;57:19. 10.1128/JCM.00547-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Psevdos G, Khoo T, Chow R, et al. Epidemiology of Lyme disease among US veterans in long Island, New York. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019;10:407–11. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maulden AB, Garro AC, Balamuth F, et al. Two-Tier Lyme disease serology test results can vary according to the specific First-Tier test used. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2020;9:128–33. 10.1093/jpids/piy133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gordillo-Pérez G, Torres J, Solórzano-Santos F, et al. [Seroepidemiologic study of Lyme’s borreliosis in Mexico City and the northeast of the Mexican Republic]. Salud Publica Mex 2003;45:351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gordillo-Pérez G, García-Juárez I, Solórzano-Santos F, et al. Serological evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in Mexican patients with facial palsy. Rev Invest Clin 2017;69:344–8. 10.24875/RIC.17002344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hatchette TF, Johnston BL, Schleihauf E, et al. Epidemiology of Lyme disease, nova Scotia, Canada, 2002-2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2015;21:1751–8. 10.3201/eid2110.141640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodríguez I, Fernández C, Sánchez L, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in humans from a Cuban village. Braz J Infect Dis 2012;16:82–5. 10.1016/s1413-8670(12)70280-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miranda J, Mattar S, Perdomo K, et al. [Seroprevalence of Lyme borreliosis in workers from Cordoba, Colombia]. Rev Salud Publica 2009;11:480–9. 10.1590/s0124-00642009000300016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lorenzi MC, Bittar RSM, Pedalini MEB, et al. Sudden deafness and Lyme disease. Laryngoscope 2003;113:312–5. 10.1097/00005537-200302000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Passos SD, Gazeta RE, Latorre MdoR, et al. [Epidemiological characteristics of Lyme-like disease in children]. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2009;55:139–44. 10.1590/s0104-42302009000200015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cinco M, Barbone F, Grazia Ciufolini M, et al. Seroprevalence of tick-borne infections in forestry rangers from northeastern Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect 2004;10:1056–61. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tomao P, Ciceroni L, D'Ovidio MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi and to tick-borne encephalitis virus in agricultural and forestry workers from Tuscany, Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005;24:457–63. 10.1007/s10096-005-1348-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Di Renzi S, Martini A, Binazzi A, et al. Risk of acquiring tick-borne infections in forestry workers from Lazio, Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:1579–81. 10.1007/s10096-010-1028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sonnleitner ST, Margos G, Wex F, et al. Human seroprevalence against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in two comparable regions of the eastern Alps is not correlated to vector infection rates. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2015;6:221–7. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krstić M, Stajković N. [Risk for infection by lyme disease cause in green surfaces maintenance workers in Belgrade]. Vojnosanit Pregl 2007;64:313–8. 10.2298/vsp0705313k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jovanovic D, Atanasievska S, Protic-Djokic V, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in occupationally exposed persons in the Belgrade area, Serbia. Braz J Microbiol 2015;46:807–14. 10.1590/S1517-838246320140698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rojko T, Bogovič P, Lotrič-Furlan S, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato infection in patients with peripheral facial palsy. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019;10:398–406. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munro H, Mavin S, Duffy K, et al. Seroprevalence of Lyme borreliosis in Scottish blood donors. Transfus Med 2015;25:284–6. 10.1111/tme.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mavin S, Evans R, Milner RM, et al. Local Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii strains in a single mixed antigen improves western blot sensitivity. J Clin Pathol 2009;62:552–4. 10.1136/jcp.2008.063461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruiz VH, Edjolo A, Roubaud-Baudron C, et al. Association of Seropositivity to Borrelia burgdorferi With the Risk of Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Functional Decline in Older Adults: The Aging Multidisciplinary Investigation Study. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:210–4. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernard A, Kodjikian L, Abukhashabh A, et al. Diagnosis of Lyme-associated uveitis: value of serological testing in a tertiary centre. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:369–72. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thorin C, Rigaud E, Capek I, et al. [Seroprevalence of Lyme Borreliosis and tick-borne encephalitis in workers at risk, in eastern France]. Med Mal Infect 2008;38:533–42. 10.1016/j.medmal.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Skogman BH, Ekerfelt C, Ludvigsson J, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia IgG antibodies among young Swedish children in relation to reported tick bites, symptoms and previous treatment for Lyme borreliosis: a population-based survey. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:1013–6. 10.1136/adc.2010.183624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Madsen KB, Wallménius K, Fridman Åke, et al. Seroprevalence against Rickettsia and Borrelia Species in Patients with Uveitis: A Prospective Survey. J Ophthalmol 2017;2017:9247465. 10.1155/2017/9247465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woessner R, Gaertner BC, Grauer MT, et al. Incidence and prevalence of infection with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent in Germany. A prospective study in young healthy subjects. Infection 2001;29:271–3. 10.1007/s15010-001-2005-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karatolios K, Maisch B, Pankuweit S. Suspected inflammatory cardiomyopathy. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in endomyocardial biopsies with positive serological evidence. Herz 2015;40:91–5. 10.1007/s00059-014-4118-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dehnert M, Fingerle V, Klier C, et al. Seropositivity of Lyme borreliosis and associated risk factors: a population-based study in children and adolescents in Germany (KiGGS). PLoS One 2012;7:e41321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilking H, Fingerle V, Klier C, et al. Antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato among Adults, Germany, 2008-2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2015;21:107–10. 10.3201/eid2101.140009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Woudenberg T, Bohm S, Bohmer M. Dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi-Specific Antibodies: seroconversion and seroreversion between two population-based, cross-sectional surveys among adults in Germany. Microorganisms 1859;2020:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dersch R, Sarnes A, Maul M, et al. Immunoblot reactivity at follow-up in treated patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis and healthy controls. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2019;10:166–9. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Visser AE, Verduyn Lunel FM, Veldink JH, et al. No association between Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a case-control study. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:227–30. 10.1111/ene.13197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kazi H, de Groot-Mijnes JDF, Ten Dam-van Loon NH, et al. No Value for Routine Serologic Screening for Borrelia burgdorferi in Patients With Uveitis in the Netherlands. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;166:189–93. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zomer TP, Barendregt JNM, van Kooten B, et al. Non-specific symptoms in adult patients referred to a Lyme centre. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019;25:67–70. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zwerink M, Zomer TP, van Kooten B, et al. Predictive value of Borrelia burgdorferi IgG antibody levels in patients referred to a tertiary Lyme centre. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2018;9:594–7. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. De Keukeleire M, Vanwambeke SO, Cochez C, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Francisella tularensis infections in Belgium: results of three population-based samples. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2017;17:108–15. 10.1089/vbz.2016.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. De Keukeleire M, Robert A, Luyasu V, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Belgian forestry workers and associated risk factors. Parasit Vectors 2018;11:277. 10.1186/s13071-018-2860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lernout T, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Saegeman V, et al. The value of seroprevalence data as surveillance tool for Lyme borreliosis in the general population: the experience of Belgium. BMC Public Health 2019;19:597. 10.1186/s12889-019-6914-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vellinga A, Kilkelly H, Cullinan J, et al. Geographic distribution and incidence of Lyme borreliosis in the West of Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 2018;187:435–40. 10.1007/s11845-017-1700-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lledó L, Gegúndez MI, Giménez-Pardo C, et al. A seventeen-year epidemiological surveillance study of Borrelia burgdorferi infections in two provinces of northern Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:1661–72. 10.3390/ijerph110201661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Segura F, Diestre G, Sanfeliu I, et al. [Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in the area of Valles Occidental (Barcelona, Spain)]. Med Clin 2004;123:395. 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74527-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lledó L, Gegúndez MI, Saz JV, et al. Screening of the prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in Madrid province, Spain. Eur J Epidemiol 2004;19:471–2. 10.1023/b:ejep.0000027349.48337.cb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oteiza-Olaso J, Tiberio-López G, Martínez de Artola V. [Seroprevalence of Lyme disease in Navarra, Spain]. Med Clin 2011;136:336–9. 10.1016/j.medcli.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lledó L, Giménez-Pardo C, Gegúndez MI. Screening of Forestry Workers in Guadalajara Province (Spain) for Antibodies to Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus, Hantavirus, Rickettsia spp. and Borrelia burgdorferi . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4500. 10.3390/ijerph16224500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vázquez-López ME, Fernández G, Díaz P, et al. [Usefulness of serological studies for the early diagnosis of Lyme disease in Primary Health Care Centres]. Aten Primaria 2018;50:16–22. 10.1016/j.aprim.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jäämaa S, Salonen M, Seppälä I, et al. Varicella zoster and Borrelia burgdorferi are the main agents associated with facial paresis, especially in children. J Clin Virol 2003;27:146–51. 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00169-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cuellar J, Dub T, Sane J, et al. Seroprevalence of Lyme borreliosis in Finland 50 years ago. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:632–6. 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. van Beek J, Sajanti E, Helve O, et al. Population-based Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato seroprevalence and associated risk factors in Finland. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2018;9:275–80. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mygland A, Skarpaas T, Ljøstad U. Chronic polyneuropathy and Lyme disease. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:1213–5. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Thortveit ET, Aase A, Petersen LB, et al. Subjective health complaints and exposure to tick-borne infections in southern Norway. Acta Neurol Scand 2020;142:260–6. 10.1111/ane.13263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hjetland R, Nilsen RM, Grude N, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in healthy adults from western Norway: risk factors and methodological aspects. APMIS 2014;122:1114–24. 10.1111/apm.12267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fryland L, Wilhelmsson P, Lindgren P-E, et al. Low risk of developing Borrelia burgdorferi infection in the south-east of Sweden after being bitten by a Borrelia burgdorferi-infected tick. Int J Infect Dis 2011;15:e174–81. 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Johansson M, Manfredsson L, Wistedt A, et al. Significant variations in the seroprevalence of C6 ELISA antibodies in a highly endemic area for Lyme borreliosis: evaluation of age, sex and seasonal differences. APMIS 2017;125:476–81. 10.1111/apm.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Jensen BB, Bruun MT, Jensen PM, et al. Evaluation of factors influencing tick bites and tick-borne infections: a longitudinal study. Parasit Vectors 2021;14:289. 10.1186/s13071-021-04751-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hristea A, Hristescu S, Ciufecu C, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Romania. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:891–6. 10.1023/a:1015600729900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kalmár Z, Briciu V, Coroian M, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in healthy blood donors in Romania: an update. Parasit Vectors 2021;14:596. 10.1186/s13071-021-05099-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shkilna M, Andreychyn M, Korda M, et al. Serological surveillance of hospitalized patients for Lyme borreliosis in Ukraine. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2021;21:301–3. 10.1089/vbz.2020.2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bazovska S, Machacova E, Spalekova M, et al. Reported incidence of Lyme disease in Slovakia and antibodies to B. burgdorferi antigens detected in healthy population. Bratisl Lek Listy 2005;106:270–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bušová A, Dorko E, Rimárová K, et al. Seroprevalence of Lyme disease in Eastern Slovakia. Cent Eur J Public Health 2018;26:S67–71. 10.21101/cejph.a5442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bušová A, Dorko E, Feketeová E, et al. Association of seroprevalence and risk factors in Lyme disease. Cent Eur J Public Health 2018;26:S61–6. 10.21101/cejph.a5274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hájek T, Pasková B, Janovská D, et al. Higher prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in psychiatric patients than in healthy subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:297–301. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Grus T, et al. Absence of Borrelia burgdorferi in the myocardium of subjects with normal left ventricular systolic function: a study using PCR and electron microscopy. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2016;160:136–9. 10.5507/bp.2015.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Cisak E, Chmielewska-Badora J, Zwoliński J, et al. Risk of tick-borne bacterial diseases among workers of Roztocze National Park (south-eastern Poland). Ann Agric Environ Med 2005;12:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zając V, Pinkas J, Wójcik-Fatla A, et al. Prevalence of serological response to Borrelia burgdorferi in farmers from eastern and central Poland. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017;36:437–46. 10.1007/s10096-016-2813-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pańczuk A, Tokarska-Rodak M, Plewik D, et al. Tick exposure and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies among hunters and other individuals exposed to vector ticks in eastern Poland. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2019;70:161–8. 10.32394/rpzh.2019.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pańczuk A, Kozioł-Montewka M, Tokarska-Rodak M. Exposure to ticks and seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi among a healthy young population living in the area of southern Podlasie, Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 2014;21:512–7. 10.5604/12321966.1120593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kiewra D, Szymanowski M, Zalewska G, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in forest workers from inspectorates with different forest types in Lower Silesia, SW Poland: preliminary study. Int J Environ Health Res 2018;28:502–10. 10.1080/09603123.2018.1489954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bura M, Bukowska A, Michalak M, et al. Exposure to hepatitis E virus, hepatitis A virus and Borrelia spp. infections in forest rangers from a single forest district in Western Poland. Adv Clin Exp Med 2018;27:351–5. 10.17219/acem/65787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wojciechowska-Koszko I, Mnichowska-Polanowska M, Kwiatkowski P, et al. Immunoreactivity of polish lyme disease patient sera to specific Borrelia antigens-part 1. Diagnostics 2021;11:2157. 10.3390/diagnostics11112157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Obaidat MM, Alshehabat MA, Hayajneh WA, et al. Seroprevalence, spatial distribution and risk factors of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Jordan. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2020;73:101559. 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Onen F, Tuncer D, Akar S, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int 2003;23:289–93. 10.1007/s00296-003-0313-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kaya AD, Parlak AH, Ozturk CE, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi infection among forestry workers and farmers in Duzce, north-western Turkey. New Microbiol 2008;31:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Aslan Başbulut E, Gözalan A, Sönmez C, et al. [Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi and tick-borne encephalitis virus in a rural area of Samsun, Turkey]. Mikrobiyol Bul 2012;46:247–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cora M, Kaklıkkaya N, Topbaş M, et al. Determination of Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi IgG in Adult Population Living in Trabzon. Balkan Med J 2017;34:47–52. 10.4274/balkanmedj.2015.0478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bucak Özlem, Koçoğlu ME, Taş T, et al. Evaluation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato seroprevalencein the province of Bolu, Turkey. Turk J Med Sci 2016;46:727–32. 10.3906/sag-1504-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Akar N, Çalışkan E, Öztürk CE, et al. Seroprevalence of hantavirus and Borrelia burgdorferi in Düzce (turkey) forest villagesand the relationship with sociodemographic features. Turk J Med Sci 2019;49:483–9. 10.3906/sag-1807-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Cikman A, Aydin M, Gulhan B, et al. Geographical Features and Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Erzincan, Turkey. J Arthropod Borne Dis 2018;12:378–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hao Q, Geng Z, Hou XX, et al. Seroepidemiological investigation of Lyme disease and human granulocytic anaplasmosis among people living in forest areas of eight provinces in China. Biomed Environ Sci 2013;26:185–9. 10.3967/0895-3988.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liu H-B, Wei R, Ni X-B, et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of tick-borne diseases at one sentinel hospital in northeastern China. Parasitology 2019;146:161–7. 10.1017/S0031182018001178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Huang N-L, Ye L, Lv H, et al. A biochip-based combined immunoassay for detection of serological status of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme borreliosis. Clin Chim Acta 2017;472:13–19. 10.1016/j.cca.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wen S, Xu Q, Liu D, et al. A seroepidemiological investigation of Lyme disease in Qiongzhong County, Hainan Province in 2019-2020. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:4721–7. 10.21037/apm-21-693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Acharya D, Park J-H. Seroepidemiologic survey of Lyme disease among forestry workers in National Park offices in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:2933. 10.3390/ijerph18062933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ikushima M, Yamada F, Kawahashi S, et al. Antibody response to OspC-I synthetic peptide derived from outer surface protein C of Borrelia burgdorferi in sera from Japanese forestry workers. Epidemiol Infect 1999;122:429–33. 10.1017/S0950268899002320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Babu K, Murthy KR, Bhagya M, et al. Seroprevalence of Lymes disease in the Nagarahole and Bandipur forest areas of South India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020;68:100–5. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_943_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Khor C-S, Hassan H, Mohd-Rahim N-F, et al. Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi among the indigenous people (Orang Asli) of Peninsular Malaysia. J Infect Dev Ctries 2019;13:449–54. 10.3855/jidc.11001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Nyataya J, Maraka M, Lemtudo A, et al. Serological evidence of yersiniosis, tick-borne encephalitis, West Nile, hepatitis E, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Lyme borreliosis, and brucellosis in febrile patients presenting at diverse hospitals in Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2020;20:348–57. 10.1089/vbz.2019.2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Norte AC, Lopes de Carvalho I, Núncio MS, et al. Getting under the birds skin: tissue tropism of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in naturally and experimentally infected avian hosts. Microb Ecol 2020;79:756–69. 10.1007/s00248-019-01442-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Strnad M, Hönig V, Růžek D, et al. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017;83:e00609–17. 10.1128/AEM.00609-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Schoen RT. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:3. 10.1007/s11926-019-0857-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Dulipati V, Meri S, Panelius J. Complement evasion strategies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. FEBS Lett 2020;594:2645–56. 10.1002/1873-3468.13894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Tuttle C. Controversies about Lyme disease. JAMA 2018;320:2481. 10.1001/jama.2018.17195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:703. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Joung H-A, Ballard ZS, Wu J, et al. Point-of-care serodiagnostic test for early-stage Lyme disease using a multiplexed paper-based immunoassay and machine learning. ACS Nano 2020;14:229–40. 10.1021/acsnano.9b08151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pegalajar-Jurado A, Schriefer ME, Welch RJ, et al. Evaluation of modified two-tiered testing algorithms for Lyme disease laboratory diagnosis using well-characterized serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 2018;56:e01943–17. 10.1128/JCM.01943-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Branda JA, Strle K, Nigrovic LE, et al. Evaluation of modified 2-tiered serodiagnostic testing algorithms for early Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:1074–80. 10.1093/cid/cix043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Sanchez-Vicente S, Tagliafierro T, Coleman JL, et al. Polymicrobial nature of tick-borne diseases. mBio 2019;10:e02055–19. 10.1128/mBio.02055-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Karasuyama H, Miyake K, Yoshikawa S. Immunobiology of acquired resistance to ticks. Front Immunol 2020;11:601504. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.601504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yang X, Gao Z, Wang L, et al. Projecting the potential distribution of ticks in China under climate and land use change. Int J Parasitol 2021;51:749–59. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ferrell AM, Brinkerhoff RJ. Using landscape analysis to test hypotheses about drivers of tick abundance and infection prevalence with Borrelia burgdorferi. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:737. 10.3390/ijerph15040737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Estrada-Peña A, Cutler S, Potkonjak A, et al. An updated meta-analysis of the distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in ticks in Europe. Int J Health Geogr 2018;17:41. 10.1186/s12942-018-0163-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2021-007744supp001.pdf (19.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.