Abstract

Background/objective

While ammonia plays a role in the complex pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), serum ammonia is unreliable for both diagnosis of, and correlation with, neurological symptoms in patients with cirrhosis. We aimed to quantify ordering, cost and appropriate use of serum ammonia in a major Midwestern healthcare system.

Design/method

Serum ammonia ordering in adult patients presenting to a large Midwestern health system was evaluated from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019.

Results

Serum ammonia ordering was prevalent, with 20 338 tests ordered over 5 years. There were no differences in the number of inappropriate serum ammonia tests per 100 000 admissions for chronic liver disease over time (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−0.24, p=0.70). As a proportion of total ammonia tests ordered, inappropriate tests increased over time (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.91, p=0.03). Inappropriate ordering was more common at community hospitals compared with the academic medical centre (99.3% vs 87.6%, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Despite evidence that serum ammonia levels are unreliable for the diagnosis of HE and are not associated with severity of HE in individuals with cirrhosis, ordering remains prevalent, contributing to waste and potential harm.

Keywords: hepatic encephalopathy, cirrhosis

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Serum ammonia levels are unreliable for the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and are not associated with severity of HE in individuals with cirrhosis.

What this study adds

Inappropriate serum ammonia ordering is prevalent and costly in those with chronic liver disease.

How might it impact clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Given the high prevalence and cost of inappropriate serum ammonia ordering, further work is needed to identify and implement effective techniques to educate clinicians on appropriate ammonia ordering in patients with chronic liver disease to reduce wasteful healthcare spending.

Introduction

The USA has the most expensive healthcare system in the world, spending 17.8% of its gross domestic product on healthcare in 2016, with hospitalisations for patients with cirrhosis accounting for US$18.8 billion of these costs.1 Recent data suggest that as much of 25% of total healthcare spending in the USA is wasteful; up to US$935 billion is estimated to be wasted each year.2 As the prevalence of cirrhosis in the USA increases, healthcare costs, along with the potential for wasteful healthcare spending, are expected to rise.2

Ammonia is a nitrogen-based neurotoxin and metabolic toxin produced by the metabolism of amino acids in the small intestine and by the breakdown of proteins by colonic bacteria.3 While ammonia is important in the complex pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), serum ammonia is unreliable for diagnosis, does not correlate with severity of symptoms in patients with cirrhosis, and does not add value to clinical evaluation of patients with cirrhosis.4–6 Furthermore, serum ammonia may be affected by several factors including diet, medications, sarcopenia and renal function.7 In contrast, ammonia plays a direct role in HE in patients with acute liver failure (ALF) and has a high prognostic value.8

The use of serum ammonia in the diagnosis of HE is not recommended by current society practice guidelines due to the low sensitivity and specificity of the test.8 9 Several initiatives, such as Choosing Wisely Canada and a recent ‘Things We Do for No Reason’ article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, have warned against the use of serum ammonia to diagnose or manage HE in patients with cirrhosis.10 Despite these recommendations, inappropriate serum ammonia ordering in patients with cirrhosis remains common and contributes to wasteful healthcare spending.11

As healthcare costs continue to spiral out of control in the USA, the inappropriate use of serum ammonia represents an opportunity for both the reduction in wasteful healthcare spending and the improvement of quality care in patients with cirrhosis. In this study, we aimed to quantify ordering, cost and appropriate use of serum ammonia in a major Midwestern healthcare system.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of adults who had a serum ammonia laboratory test ordered during an emergency department (ED) visit or hospital admission to a large Midwestern healthcare system between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2019, comprising eight hospitals, including one high-volume liver transplant academic medical centre. The bed capacity of the eight hospitals ranges from 36 to 828 beds, and four of the eight hospitals have a capacity of under 100 patients. The four largest hospitals have general gastroenterology consultation services available, but only the academic medical centre also has a specialised hepatology consultation service and the ability to perform liver transplantation. Liver transplant recipients were excluded from the analysis.

Sociodemographic information (age, gender and race/ethnicity), serum ammonia testing and International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for chronic liver disease and ALF were collected. All encounters for ALF were validated with manual chart review by a single physician using a standard definition—evidence of coagulation abnormality with an international normalised ratio >1.5 and any degree of mental alteration (encephalopathy) in a patient without preexisting cirrhosis and with an illness of <26 weeks’ duration.12 The diagnosis of urea cycle disorders were confirmed by manual chart review after initial abstraction using ICD-9/ICD-10 code for urea cycle disorders. Serum ammonia use was categorised as appropriate when used in the management of ALF and urea cycle disorders; the use of serum ammonia was otherwise deemed inappropriate.

Descriptive statistics were calculated and presented by group. Median and IQR were presented for continuous variables that were not normally distributed. Frequency and percentage were presented for categorical variables. Categorical variables were analysed using χ2 test. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the trends in serum ammonia ordering over time. Significance was defined as a p<0.05.

Results

A total of 20 338 serum ammonia tests for 8536 patients were ordered over the 5-year study. The median age of the cohort was 63 years (IQR 52–73) with 54.5% males. The majority of patients were non-Hispanic white (82.0%), followed by non-Hispanic black (7.5%), Asian (2.3%) and Hispanic or Latino (1.5%). The most common insurance coverage was Medicare (52.0%) followed by private insurance (31.1%, table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the total cohort (n=8536)

| Total (median, IQR) or (N, %) | |

| Age in years | 63.0 (52–73) |

| Male gender | 4646 (54.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 7000 (82.0) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 637 (7.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 131 (1.5) |

| Asian | 197 (2.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 247 (2.9) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 8 (0.1) |

| Other/unknown | 158 (3.7) |

| Insurance status | |

| Medicare | 4376 (52.0) |

| Medicaid | 1498 (17.6) |

| Private | 2617 (31.1) |

| Other/missing | 45 (0.5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 4527 (53.0) |

| Acute liver failure | 69 (0.8) |

| Urea cycle disorder | 8 (0.1) |

| Valproic acid use | 148 (1.7) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5 (2–9) |

A total of 4527 patients (53.0% of the total cohort) had an ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnoses of chronic liver disease; 8 patients (0.1%) had an ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis of a urea cycle disorder; 69 patients (0.8%) had a diagnosis of ALF and 148 patients were on valproic acid (1.7%). Of the 20 338 serum ammonia tests ordered, 1138 (6.5%) tests were ordered for a definitively appropriate indication, while the remaining tests were inappropriately ordered.

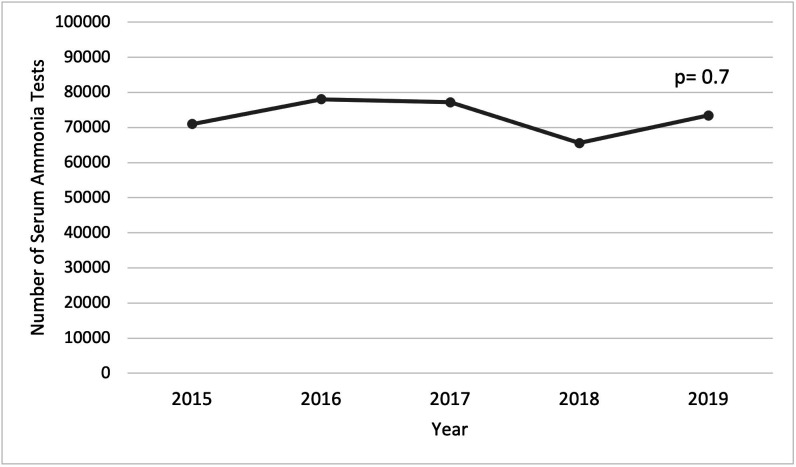

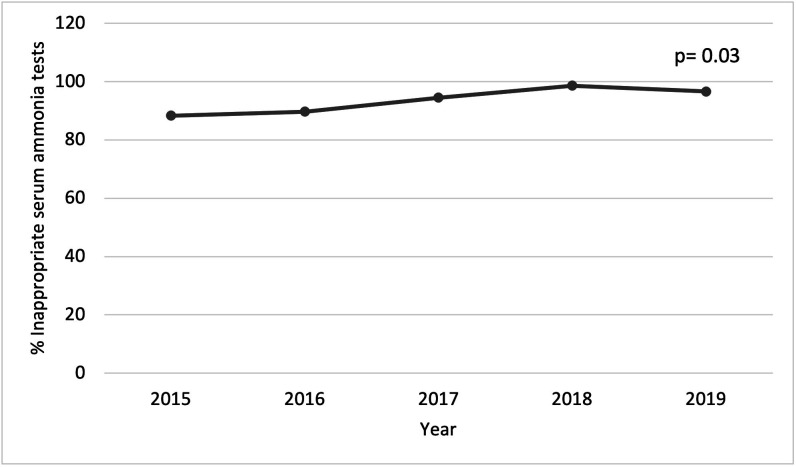

There were no differences in the number of inappropriate serum ammonia tests per 100 000 admissions for chronic liver disease over time (Pearson’s correlation coefficient of −0.24, p=0.70) (figure 1 and online supplemental table 1). The proportion of inappropriate tests to the total number of serum ammonia tests ordered increased over time (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.91, p=0.03) (figure 2 and online supplemental table 2).

Figure 1.

Inappropriate serum ammonia tests per 100 000 admissions for chronic liver disease.

Figure 2.

Inappropriate serum ammonia tests per total serum ammonia tests.

flgastro-2021-101837supp001.pdf (38.1KB, pdf)

49.4% (n=10 042) of serum ammonia tests were ordered at the academic medical centre on 4280 patients, while the remainder (n=10 296) were ordered at community hospitals within the health system on 4256 patients. 12.4% ammonia tests at the academic medical centre compared with 0.7% of ammonia tests at community hospitals were ordered for appropriate indications (p<0.0001).

Based on the 2018 clinical diagnostic laboratory fee schedule for Medicare, serum ammonia testing costs US$17.99. Thus, a minimum of US$342 169.8 was spent on inappropriate serum ammonia testing in our health system over the 5-year study period.

Discussion

We demonstrate that inappropriate serum ammonia use is prevalent and costly in a large Midwestern health system, including community and academic sites. Despite initiatives to educate practitioners on inappropriate serum ammonia use, such as the Choosing Wisely campaign, there was no change in ordering patterns between 2015 and 2019. Inappropriate use—the use of serum ammonia outside of the management of ALF and urea cycle disorders—was more common among community hospitals compared with the academic care centre.

Although the cost of an individual serum ammonia test is low, the aggregate costs can be significant, as much of this cost is frank waste. The Medicare fee schedule is usually interpreted as the lowest possible price for a medical test; however, this can increase markedly when using private insurance or private laboratories. The price of a serum ammonia test may be as high as US$139 in some private laboratories; therefore, the cost of inappropriate serum ammonia use may be up to an additional US$2 323 392 for the study period.13 Furthermore, the costs represented in this study are for a single health system alone, suggesting that the costs of inappropriate serum ammonia testing are immense when extrapolated nationally. This expenditure could increase further due to the rising trends of hospitalisations for HE in the USA.14

HE is a complex pathophysiological process that cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory value alone; instead, HE requires a thoughtful evaluation to make the clinical diagnosis. The standard for the diagnosis of HE is clinical evaluation. Therefore, reliance on this laboratory test for diagnostic and management reasoning in patients with cirrhosis is a recipe for diagnostic error: both high and low values can lead to erroneous conclusions. Serum ammonia is notoriously unreliable for diagnosis of HE and is not recommended in current society practice guidelines.9 One study showed that a venous ammonia level ≥55 μmol/L had a sensitivity and specificity of 47.2% and 78.3%, respectively, for HE compared with the West Haven criteria and the critical flicker frequency test.15 Another study demonstrated that checking serum ammonia levels in patients admitted with HE did not impact management in terms of lactulose prescribed or clinical outcomes.16

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, serum ammonia remains nearly ubiquitous in the evaluation of patients with cirrhosis. In our study, inappropriate usage of serum ammonia testing (as a proportion of all ammonia tests ordered) appeared to increase over the study period, highlighting the need for new, systematic approaches to reduce this practice. One potential intervention is the use of a decision support tool integrated into the electronic health record to notify clinicians of the appropriate use of the test and to confirm the clinician’s intent. Similar decision support tools have been shown to reduce over testing in other aspects of liver disease care, such as ceruloplasmin ordering.17 Another potential intervention is to limit the ability to order serum ammonia in settings such as the emergency department or to limit ordering to those who care for patients with ALF, valproic acid toxicity or urea cycle disorders. This type of approach has been successful in eliminating inpatient faecal occult blood testing, successfully reducing the number of unnecessary endoscopies performed at a large, urban teaching hospital.18

Our findings show a higher rate of inappropriate serum ammonia use at community hospitals compared with the academic medical centre. Previous studies of Medicare data have shown that admissions to teaching hospitals are associated with higher costs—but better patient outcomes—including lower overall 30-day mortality, compared with non-teaching hospitals.19 While inappropriate ordering of serum ammonia prevails, it is possible that the current initiatives are having some impact in teaching hospitals. The higher rate of inappropriate ammonia use at community hospitals is likely multifactorial: academic centres often have greater access to advanced informatics; are early adopters in new research; have a larger volume of patients with cirrhosis and thus more clinician experience; have ready access to hepatology consultation and may have access to additional grant-based financial support for quality improvement.

This study has limitations. First, our study was retrospective and focused on a single Midwestern health system, which limits the generalisability. Cirrhosis was identified using diagnostic coding data, which is subject to coding inaccuracy and incompleteness. In a similar manner, we suspect that the true numbers of patients with cirrhosis in our cohort were underrepresented due to inaccurate coding. We were unable to obtain the reason for ordering serum ammonia testing and details on the clinician who ordered the study—such as provider specialty and level of training—could not be ascertained in this study but may have influenced unnecessary ordering of this test; future studies would benefit from obtaining this level of data to inform the optimal target audience for future interventions. Finally, we were unable to obtain accurate data on serum ammonia testing in the ED resulting in calculation of inappropriate testing as a proportion of all tests ordered- this approach fails to account for patients in need of ammonia testing but who did not receive it.

Despite the knowledge that serum ammonia levels do not inform the management of individuals with HE, ordering remains prevalent. The potential cost for this practice is massive when considering price inflation (by health systems) in patients with private insurance and when extrapolating these trends to a national level. In addition, the risk of associated diagnostic error is high. Further work is needed to identify and implement effective techniques to educate practitioners on appropriate ammonia ordering in patients with chronic liver disease to reduce wasteful healthcare spending.

Footnotes

Contributors: Role in the Study: Study concept and design (EA and NL); acquisition of data (EA and NL); analysis and interpretation of data (EA and NL); drafting of the manuscript (EA, NL); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (EA, NL and APJO); statistical analysis (EA and NL); obtained funding (not applicable).

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota (STUDY00009348).

References

- 1. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 2018;319:1024–39. 10.1001/jama.2018.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA 2019;322:1501–9. 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Richardson AJ, McKain N, Wallace RJ. Ammonia production by human faecal bacteria, and the enumeration, isolation and characterization of bacteria capable of growth on peptides and amino acids. BMC Microbiol 2013;13:6. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Butterworth RF, Giguère JF, Michaud J, et al. Ammonia: key factor in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Pathol 1987;6:1–12. 10.1007/BF02833598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gonzalez JJ, Tapper EB. A prospective, blinded assessment of ammonia testing demonstrates low utility among front-line clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;S1542-3565(21)00019-7. 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bajaj JS, Bloom PP, Chung RT, et al. Variability and lability of ammonia levels in healthy volunteers and patients with cirrhosis: implications for trial design and clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:783–5. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ge PS, Runyon BA. Serum ammonia level for the evaluation of hepatic encephalopathy. JAMA 2014;312:643–4. 10.1001/jama.2014.2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhatia V, Singh R, Acharya SK. Predictive value of arterial ammonia for complications and outcome in acute liver failure. Gut 2006;55:98–104. 10.1136/gut.2004.061754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, European Association for the Study of the Liver . Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 practice guideline by the European association for the study of the liver and the American association for the study of liver diseases. J Hepatol 2014;61:642–59. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ninan J, Feldman L. Ammonia levels and hepatic encephalopathy in patients with known chronic liver disease. J Hosp Med 2017;12:659–61. 10.12788/jhm.2794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumral D, Qayyum R, Roseff S, et al. Adherence to recommended inpatient hepatic encephalopathy workup. J Hosp Med 2019;14:156–60. 10.12788/jhm.3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American association for the study of liver diseases position paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology 2012;55:965–7. 10.1002/hep.25551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammonia blood test cost. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files-Items/18CLAB. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files-Items/18CLAB

- 14. Hirode G, Vittinghoff E, Wong RJ. Increasing burden of hepatic encephalopathy among hospitalized adults: an analysis of the 2010-2014 national inpatient sample. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:1448–57. 10.1007/s10620-019-05576-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gundling F, Zelihic E, Seidl H, et al. How to diagnose hepatic encephalopathy in the emergency department. Ann Hepatol 2013;12:108–14. 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31392-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haj M, Rockey DC. Ammonia levels do not guide clinical management of patients with hepatic encephalopathy caused by cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:723–8. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Lai M, et al. A decision support tool to reduce overtestingfor ceruloplasmin and improve adherence with clinical guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1561–2. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta A, Tang Z, Agrawal D. Eliminating in-hospital fecal occult blood testing: our experience with disinvestment. Am J Med 2018;131:760–3. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor DH, Whellan DJ, Sloan FA. Effects of admission to a teaching hospital on the cost and quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med 1999;340:293–9. 10.1056/NEJM199901283400408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2021-101837supp001.pdf (38.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Not applicable.