Abstract

Objectives

The burden of substance use in Kenya is significant. The objective of this study was to systematically summarize existing literature on substance use in Kenya, identify research gaps, and provide directions for future research.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA guidelines. We conducted a search of 5 bibliographic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library) from inception until 20 August 2020. In addition, we searched all the volumes of the official journal of the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol & Drug Abuse (the African Journal of Alcohol and Drug Abuse). The results of eligible studies have been summarized descriptively and organized by three broad categories including: studies evaluating the epidemiology of substance use, studies evaluating interventions and programs, and qualitative studies exploring various themes on substance use other than interventions. The quality of the included studies was assessed with the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs.

Results

Of the 185 studies that were eligible for inclusion, 144 investigated the epidemiology of substance use, 23 qualitatively explored various substance use related themes, and 18 evaluated substance use interventions and programs. Key evidence gaps emerged. Few studies had explored the epidemiology of hallucinogen, prescription medication, ecstasy, injecting drug use, and emerging substance use. Vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, and persons with physical disability had been under-represented within the epidemiological and qualitative work. No intervention study had been conducted among children and adolescents. Most interventions had focused on alcohol to the exclusion of other prevalent substances such as tobacco and cannabis. Little had been done to evaluate digital and population-level interventions.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review provide important directions for future substance use research in Kenya.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO: CRD42020203717.

Introduction

Globally, substance use is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, substance use disorders (SUDs) were the second leading cause of disability among the mental disorders with 31,052,000 (25%) Years Lived with Disability (YLD) attributed to them [1]. In 2016, harmful alcohol use resulted in 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) worldwide and 132.6 (5.1%) million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [2]. Tobacco use, the leading cause of preventable death, kills more than 8 million people worldwide annually [3]. Alcohol and tobacco use are leading risk factors for non-communicable diseases for example cardiovascular disease, cancer, and liver disease [3, 4]. Even though the prevalence rate of opioid use is small compared to that of tobacco and alcohol use, opioid use disorder contributes to 76% of all deaths from SUDs [4]. Other psychoactive substances such as cannabis and amphetamines are associated with mental health consequences including increased risk of suicidality, depression, anxiety and psychosis [5, 6]. In addition to the effect on health, substance use is associated with significant socio-economic costs arising from its impact on health and criminal justice systems [7].

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear the burden of substance use. Over 80% of the 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide live in LMICs [3]. In 2016, the alcohol-attributable disease burden was highest in LMICs compared to upper-middle-income and high-income countries (HICs) [2]. In Kenya, a nationwide survey conducted in 2017 reported that over 10% of Kenyans between the ages of 15 to 65 years had a SUD [8]. In another survey, 20% of primary school children had ever used at least one substance in their lifetime [9]. Moreover, Kenya has the third highest total DALYs (54,000) from alcohol use disorders (AUD) in Africa [4] Unfortunately, empirical work on substance use in LMICs is limited [10, 11]. In a global mapping of SUD research, majority of the work had been conducted in upper-middle income and HICs (HICs) [11]. In a study whose aim was to document the existing work on mental health in Botswana, only 7 studies had focused on substance use [10]. Information upon which policy and interventions could be developed is therefore lacking in low-and-middle income settings.

Since the early 1980s, scholars in Kenya began engaging in research to document the burden and patterns of substance use [12]. In 2001 the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA) was established in response to the rising cases of harmful substance use in the country particularly among the youth. The mandate of the Authority was to educate the public on the harms associated with substance use [13]. In addition to prevention work, NACADA contributes to research by conducting general population prevalence surveys every 5 years and recently launched its journal, the African Journal of Alcohol and Drug Abuse (AJADA) [14]. The amount of empirical work done on substance use in Kenya has expanded since these early years but has not been systematically summarized. The evidence gaps therefore remain unclear.

In order to guide future research efforts and adequately address the substance use scourge in Kenya, there is need to document the scope and breadth of available scientific literature. The aim of this systematic review is therefore: (i) to describe the characteristics of research studies conducted on substance use and SUD in Kenya; (ii) to assess the methodological quality of the studies; (iii) to identify areas where there is limited research evidence and; (iv) to make recommendations for future research. This paper is in line the Vision 2030 [15], Kenya’s national development policy framework, which directs that the government implements substance use treatment and prevention projects and programs, and target 3.5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which requires that countries strengthen the treatment and prevention for SUDs [16].

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

In conducting this systematic review we adhered to the recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [17]. A 27-item PRISMA checklist is available as an additional file to this protocol (S1 Checklist). Our protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020203717.

Search strategy

A search was carried out in five electronic databases on 20th August 2020: PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library. The full search strategy can be found in S1 File and takes the following form: (terms for substance use) and (terms for substance use outcomes of interest) and (terms for region). The searches spanned the period from inception to date. No filter was applied. A manual search was done in Volumes 1, 2 and 3 (all published volumes by the time of the search) of the recently launched AJADA journal by NACADA, and additional articles identified.

Study selection

Following the initial search, all articles were loaded onto Mendeley reference manager where initial duplicate screening and removal was done. After duplicate removal, the articles were loaded onto Rayyan, a soft-ware for screening and selecting studies during the conduct of systematic reviews [20]. The abstract and titles of retrieved articles were independently screened by two authors based on a set of pre-determined eligibility criteria. A second screening of full text articles was also done independently by two authors and resulted in an 88.7% agreement. Disagreements during each stage of the screening were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Inclusion criteria

Since we sought to map existing literature on the subject, our inclusion criteria were broad. We included articles on substance use if (i) the sample or part of the sample was from Kenya, (ii) they were original research articles, (iii) they had a substance use or SUD exposure, (iv) they had a substance use or SUD related outcome such as prevalence, pattern of use, prevention and treatment, and (iv) they were published in English or had an English translation available. We included studies conducted among all age groups and studies that used all designs including quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if: (i) they were cross-national and did not report country specific results (ii) they did not report substance use or SUD as an exposure, and did not have substance use or SUD related outcomes or as part of the outcomes, (iii) they were review articles, dissertations, conference presentations or abstracts, commentaries or editorials, (iv) and the full text articles were not available.

Data extraction

We prepared 3 data extraction forms based on three emerging categories of studies i.e.:

Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD

Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs

Studies qualitatively exploring various themes on substance use or SUD (but not evaluating interventions or programs)

The forms were piloted by F.J. and S.K. and adjustments made to the content. Data extraction was then done using the final form by all authors and double checked by F.J. for completeness and accuracy. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with S.K. and E.T. until consensus was achieved. The following data was extracted for each study category:

Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD: study design, study population characteristics, study setting, sample size, age and gender distribution, substance(s) assessed, standardized tool or criteria used, main findings (prevalence, risk factors, other key findings).

Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs: study design, study objective, sample size, name of the intervention or program, person delivering intervention, outcomes and measures, and main findings.

Studies qualitatively exploring various aspects of substance use or SUD other than programs and interventions: study objective, methods of data collection, study setting, study population, age and gender distribution, theoretical framework used, and main findings.

Data synthesis

The results have been summarized descriptively and organized by the three categories above. Within each category, a general description of the study characteristics has been provided followed by a narrative synthesis of findings organized by sub-themes inductively derived from the data. The sub-themes within each category are as follows:

Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD: Epidemiology of alcohol use, epidemiology of tobacco use, epidemiology of khat use, epidemiology of cannabis use, epidemiology of opioid and cocaine use, epidemiology of other substance use (sedatives, inhalants, hallucinogens, prescription medication, emerging drugs, ecstasy).

Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs: Individual level interventions (Individual-level interventions for harmful alcohol use, individual-level interventions for khat use, individual level intervention for substance use in general); Programs (Methadone programs, needle-syringe programs, tobacco cessation programs, out-patient SUD treatment programs); Population-level interventions: Population-level tobacco interventions, population-level alcohol interventions.

Studies qualitatively exploring various aspects of substance use or SUD other than programs and interventions: Injecting drug use and heroin use, alcohol use, substance use among youth and adolescents, other topics.

Quality assessment of the studies

Quality assessment was conducted by S.K. using the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) [21]. F.J. & J.B. double checked the scores for completeness and accuracy. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. We had initially planned to use the National Institute of Health (NIH) set of quality assessment tools but due to the diverse nature of study designs, the authors agreed to use the QATSDD tool. The QATSDD is a 16-item tool for both qualitative and quantitative studies. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale (0–3), with a total of 14 criteria for each study design and 16 for studies with mixed methods. Scoring relies on guidance notes provided as well as judgment and expertise from the reviewers. The criteria used are: (i) theoretical framework; (ii) statement of aims or objectives; (iii) description of research setting; (iv) sample size consideration; (v) representative sample of target group (vi) data collection procedure description; (vii) rationale for choice of data collection tool(s); (viii) detailed recruitment data; (ix) statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tools (quantitative only); (x) fit between research question and method of data collection (quantitative only); (xi) fit between research question and format and content data collection (qualitative only); (xii) fit between research question and method of analysis; (xiii) justification of analytical method; (xiv) assessment of reliability of analytical process (qualitative only); (xv) user involvement in design and (xvi) discussion on strengths and limitations[21]. Scores are awarded for each criterion as follows: 0 = no mention at all; 1 = very brief description; 2 = moderate description; and 3 = complete description. The scores of each criterion are then summed up with a maximum score of 48 for mixed methods studies and 42 for studies using either qualitative only or quantitative only designs. For ease of interpretation, the scores were converted to percentages and classified as low (<50%), medium (50%–80%) or high (>80%) quality of evidence [22].

Results

Search results

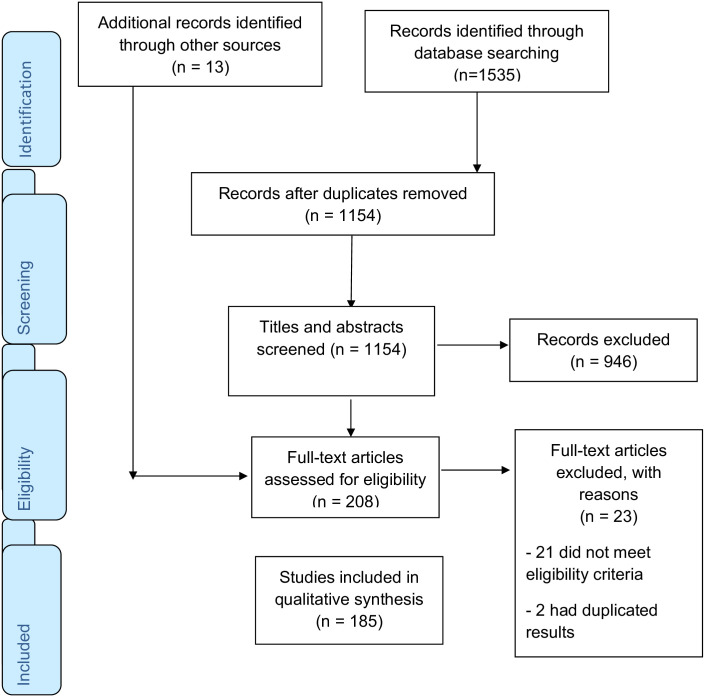

The search from the five electronic databases yielded 1535 results: 950 from PubMed, 173 from PsychINFO, 210 from web of science, 123 from CINAHL and 79 from Cochrane library. Thirteen additional studies were identified through a manual search of the AJADA journals (Volumes 1, 2 and 3). Studies were assessed for duplicates and 1154 articles remained after removal of duplicates. The 1154 studies underwent an initial screening based on abstracts and titles, and 946 articles were excluded. A second screen of full text articles was done for the 208 studies that were potentially eligible for the review. Twenty three studies were excluded as follows: 21 did not meet the eligibility criteria and 2 had duplicated results. A total of 185 studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Fig 1).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart.

General characteristics of the studies

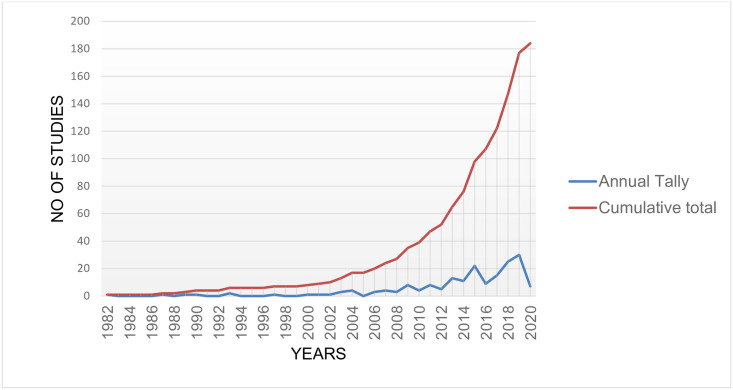

Of the 185 studies included in this review, 144 (77.8%) investigated the epidemiology of substance use or SUD, 18 (9.7%) evaluated substance use or SUD interventions and programs, and 23 (12.4%) were qualitative studies exploring perceptions on various substance use or SUD topics other than interventions and programs (Table 4). The studies were published between 1982 and 2020. The number of studies published has gradually increased in number over the years, particularly in the past decade. Fig 2 shows the publication trends for substance use research in Kenya.

Fig 2. Line graph showing publication trends for substance use research in Kenya.

Quality assessment

The QATSDD scores ranged from 28.6% [23] to 92.9% [24]. Only 14 studies [12, 23, 25–36] (all quantitative) had scores of less than 50%. Of these, the main items driving low quality were: no mention of user involvement in study design (n = 14) [12, 23, 25–36], no explicit mention of a theoretical framework (n = 10) [12, 23, 25–28, 30, 33, 35, 36] and a lack of a statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tools (n = 10) [12, 23, 25, 28, 30–33, 35, 36] Table 1.

Table 1. Quality assessment.

| Mixed Methods studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| Author, year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total/48 | Percentage of total |

| Kamenderi et al., 2020 [37] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 72.9 |

| Mackenzie et al., 2009 [38] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 70.8 |

| Mutai et al., 2020 [39] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 34 | 70.8 |

| Papas et al., 2010 [40] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 42 | 87.5 |

| Qualitative studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| Author, Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total/42 | Percentage of total |

| Bazzi et al., 2019 [41] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Beckerleg 2004 [42] | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Ezard et al., 2011 [43] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Guise et al., 2015 [44] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Guise et al., 2019 [45] | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Kibicho & Campbell, 2019 [46] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Mburu et al., 2018 [47] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Mburu et al., 2019 [48] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Mburu et al., 2020 [49] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Mburu et al., 2019 [50] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Mburu, 2018[51] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Mital et al., 2016 [52] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Muturi, 2014 [53] | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Muturi, 2015 [54] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Muturi et al., 2016 [55] | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Ndimbii et al., 2015 [56] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Ndimbii et al., 2018 [57] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Njue et al., 2009 [58] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Njue et al., 2011 [59] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Othieno et al., 2012 [60] | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Rhodes et al., 2015 [61] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Rhodes, 2018 [62] | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Ssewanyana et al., 2018 [63] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Syvertsen et al., 2016 [64] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 52.3 |

| Syvertsen et al., 2019 [65] | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Velloza et al., 2015 [66] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Yotebieng et al., 2016 [67] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Quantitative studies | ||||||||||||||||||

| First author, Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total/42 | Percentage of total |

| Aden et al., 2006 [23] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 12 | 28.6 |

| Akiyama et al., 2019 [68] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Anundo, 2019 [69] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Asiki et al., 2018 [70] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Astrom et al., 2004 [71] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 2 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Atwoli et al., 2011 [72] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Ayah et al., 2013 [73] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Ayaya et al., 2002 [74] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Balogun et al., 2014 [75] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Beckerlerg et al., 2006 [76] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Bengston et al., 2014 [77] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Budambula et al., 2018 [78] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Cagle et al., 2018 [79] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Chersich et al., 2014 [80] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Christensen et al., 2009 [81] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Cleland et al. 2007 [82] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 27 | 64.2 |

| De Menil et al., 2014 [83] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 2 | 1 | NA | 0 | 2 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Deveau Dhadphale, 2010 [84] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Dhadphale et al., 1982 [12] | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 14 | 33.3 |

| Dhadphale, 1997 [27] | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 18 | 42.9 |

| Embleton, 2012 [85] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Embleton et al., 2013[86] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Embleton et al., 2017 [87] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Gathecha et al., 2018 [88] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Gichuki et al., 2015 [89] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 1 | 2 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Gitatui et al., 2019 [24] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | 39 | 92.9 |

| Giusto et al., 2020 [90] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 1 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Goldblatt et al., 2015 [91] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 1 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Goodman et al., 2017 [92] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Hall et al., 1993 [93] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Harder et al., 2019 [94] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Haregu et al., 2019 [95] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Hulzebosch et al., 2015 [96] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Jenkins et al., 2017 [97] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Joshi et al., 2015 [98] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Kaai et al., 2019 [99] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Kaduka et al., 2017 [100] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 0 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Kamau et al., 2017 [101] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Kamenderi, 2019 [102] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Kamenderi et al., 2019 [103] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 0 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Kamenderi et al., 2019 [104] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 1 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Kamotho et al., 2004[105] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Kanyanya et al., 2007 [31] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Kaplan et al., 1990 [106] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 1 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Kendagor et al., 2018 [107] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Khasakhala et al., 2013 [108] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Khasakhala et al., 2013 [109] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Kiburi et al., 2018 [110] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Kimando et al., 2017 [111] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Kimani et al., 2019 [112] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Kimbui et al., 2018[113] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Kinoti et al., 2011 [114] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 2 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Kinyanjui & Atwoli, 2013 [115] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Kisilu et al., 2019 [29] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 19 | 45.2 |

| Komu et al., 2009[116] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 2 | 21 | 50.0 |

| Korhonen et al., 2018 [117] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Kunzweiler et al., 2017 [118] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Kunzweiler et al., 2018 [119] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Kuria et al., 2012 [120] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Kurth et al., 2015 [121] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Kurui & Ogoncho, 2019 [122] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Kurui & Ogoncho, 2020 [123] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 22 | 52.4 |

| Kwamanga et al., 2001 [124] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 0 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Kwamanga et al., 2003 [125] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Kwobah et al., 2017 [126] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| L’Engle et al., 2014 [127] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Lo et al., 2013 [128] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Luchters et al., 2011 [129] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Lukandu et al., 2015 [130] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Macigo et al., 2006 [32] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Magati et al., 2018 [131] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Maina et al., 2015 [132] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Mannik et al., 2018 [133] | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Maru et al., 2003 [30] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 19 | 45.2 |

| Mburu et al., 2018 [134] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Medley et al., 2014 [135] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Menach et al., 2012 [136] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Menya et al., 2019 [137] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Micheni et al., 2015 [33] | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Mkuu et al., 2018 [138] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Mohammed et al., 2018 [139] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Mokaya et al., 2016 [140] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Moscoe et al., 2019 [141] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Mundan et al., 2013 [142] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Mungai & Midigo, 2019 [143] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 21 | 50.0 |

| Muraguri et al., 2015 [144] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 2 | 21 | 50.0 |

| Muriungi & Ndetei, 2013[145] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Muthumbi et al., 2017 [146] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Mutiso et al., 2019 [147] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Muture et al., 2011 [148] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 1 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Mwangi et al., 2019[149] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Nall et al., 2019 [150] | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Ndegwa & Waiyaki, 2020 [151] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Ndetei et al., 2008 [28] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 18 | 42.9 |

| Ndetei et al., 2008 [152] | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 22 | 52.4 |

| Ndetei et al., 2009 [153] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Ndetei et al., 2009 [154] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 0 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Ndetei et al., 2010 [34] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Ndetei et al., 2012 [155] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 27 | 64.2 |

| Ndugwa et al., 2011 [156] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 37 | 88.1 |

| Ng’ang’a et al., 2018 [157] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Ngaruyia et al., 2018 [158] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Nguchu et al., 2009 [159] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Ngure et al., 2019 [160] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Nielsen et al., 1989 [161] | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 24 | 57.1 |

| Njoroge et al., 2017 [162] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Njuguna et al., 2013 [25] | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 1 | 16 | 38.1 |

| Ogwell et al., 2003 [163] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Okal et al., 2013 [164] | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 3 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Olack et al., 2015 [165] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Ominde et al., 2019 [35] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Omolo & Dhadphale, 1987 [36] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 20 | 47.6 |

| Ongeri et al., 2019 [166] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 35 | 83.3 |

| Onsomu et al., 2015[167] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Othieno et al., 2000 [168] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Othieno et al., 2014[169] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Othieno et al., 2015a[170] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 29 | 69.0 |

| Othieno et al., 2015b [171] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Owuor et al., 2019 [172] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 1 | 1 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Oyaro et al., 2018 [173] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Pack et al., 2014 [174] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Papas et al., 2011 [175] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 1 | 2 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Papas et al., 2016[176] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Papas et al., 2017 [177] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 40 | 95.2 |

| Parcesepe et al., 2016 [178] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Patel et al., 2013 [179] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 21 | 50.0 |

| Peltzer et al., 2009 [180] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Peltzer et al., 2011 [181] | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Pengpid & Peltzer, 2019 [182] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Perl et al., 2015 [183] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Ploubidis, 2013 [184] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Roth et al., 2017 [185] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Rudatsikira et al., 2007 [186] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Sanders et al., 2007 [187] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 27 | 64.3 |

| Saunders et al., 1993 [188] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 0 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Secor et al., 2015 [189] | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 2 | 31 | 73.8 |

| Syvertsen et al., 2015 [190] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 23 | 54.8 |

| Shaffer et al., 2004 [191] | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Takahashi et al., 2017 [192] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Takahashi et al., 2018 [193] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 33 | 78.6 |

| Tang et al., 2018 [194] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 26 | 61.9 |

| Tegang et al., 2010[195] | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 1 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Thuo et al., 2008 [26] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | NA | 3 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 17 | 40.5 |

| Tsuei et al., 2017 [196] | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 25 | 59.5 |

| Tun et al., 2015 [197] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 30 | 71.4 |

| Wekesah et al., 2018 [198] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 2 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Were et al., 2014 [199] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 1 | NA | 0 | 1 | 25 | 59.5 |

| White et al., 2016 [200] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 2 | NA | 0 | 3 | 28 | 66.7 |

| Widmann et al., 2014 [201] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Widmann et al., 2017 [202] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Wilson et al., 2016 [203] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 36 | 85.7 |

| Winston et al., 2015 [204] | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 0 | 3 | 32 | 76.2 |

| Winter et al., 2020 [205] | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 1 | 3 | 34 | 81.0 |

| Woldu et al., 2019 [206] | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 38 | 90.5 |

Studies examining the epidemiology of substance use or SUD

General description of epidemiological studies

One hundred and forty-four studies examined the prevalence and or risk factors for various substances. The studies were published between 1982 and 2020. The four main study designs used were cross-sectional (n = 126), cohort (n = 5), case-control (n = 10), and mixed methods (n = 2). One study used a combination of the multiplier method, Wisdom of the Crowds (WOTC) method, and a published literature review to document the size of key populations [164]. The sample size for this category of studies ranged from 42 [130] to 72292 [128].

The studies were conducted in diverse settings including the community (n = 72), hospitals (n = 40), institutions of learning (n = 24), streets (n = 5), prisons and courts (n = 3), charitable institutions (n = 1), methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) clinics (n = 1), and in needle-syringe program (NSP) sites (n = 1). Of the studies conducted within the community, 12 were conducted in informal settlements. The study populations were similarly diverse as follows: general population adults & adolescents (n = 39), persons with NCDs (n = 11), primary and secondary school students (n = 15), people who inject drugs (PWID) (n = 11), general patients (n = 5), men who have sex with men (MSM) (n = 8), university and college students (n = 9), commercial sex workers (n = 7), psychiatric patients (n = 6), orphans and street connected children and youth (n = 6), people living with HIV (PLHIV) (n = 6), healthcare workers (n = 3), law offenders (n = 3), military (n = 1), and teachers (n = 1). Only one study was conducted among pregnant women [131].

Sixty-nine studies (47.6%) used a standardized diagnostic tool to assess for substance use. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (n = 21) and the Alcohol, Smoking & Substance Use Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) questionnaire (n = 10) were the most frequently used tools. Most papers assessed for alcohol (n = 109) and tobacco use (n = 80). Other substances assessed included khat (n = 34), opioids (n = 21), sedatives (n = 19), cocaine (n = 19), inhalants (n = 16), cannabis (n = 14), hallucinogens (n = 7), prescription medication (n = 4), emerging drugs (n = 1) and ecstasy (n = 1). Most studies (n = 93) assessed for more than one substance.

Epidemiology of alcohol use

One hundred and nine papers assessed for the prevalence and or risk factors for alcohol use. Using the AUDIT, the 12-month prevalence rate for hazardous alcohol use ranged from 2.9% among adults drawn from the community [97] to 64.6% among female sex workers (FSW) [77]. Based on the same tool, the lowest and highest 12-month prevalence rates for harmful alcohol use were both reported among FSWs i.e. 9.3% [80] and 64.0% [174] respectively, while the prevalence of alcohol dependence ranged from 8% among FSWs living with HIV [203] to 33% among MSM who were commercial sex workers [144]. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for alcohol use was reported by Ndegwa & Waiyaki [151]. The authors found that 95.7% of undergraduate students had ever used alcohol.

Alcohol use, was associated with several socio-demographic factors including being male [50, 112, 114, 140, 158, 168, 182, 191], being unemployed [114], being self-employed [97], having a lower socio-economic status (SES) [128], being single or separated, living in larger households [97], having a family member struggling with alcohol use, and alcohol being brewed in the home [143]. Alcohol use was linked to various health factors including glucose intolerance [81], poor cardiovascular risk factor control [111], having a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus [134], hypertension [112, 139], default from tuberculosis (TB) treatment [148], depression [113], psychological Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) [205], tobacco use [182, 205], and increased risk of esophageal cancer [137, 179]. Finally, alcohol use was associated with involvement in Road Traffic Accidents (RTAs) [88], and having injuries [88, 171] and suicidal behavior [109].

Epidemiology of tobacco use

Eighty papers assessed for the prevalence and risk factors for tobacco use. The lifetime prevalence of tobacco use ranged from 23.5% among healthcare workers (HCWs) [140] to 84.3% among psychiatric patients [110]. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for tobacco use was reported by Ndegwa & Waiyaki [151]. The authors found that 95.7% of undergraduate students had ever used tobacco.

Tobacco use was associated with socio-demographic factors such as being male [112, 140, 168] and living in urban areas [163]. Several health factors were linked to tobacco use including hypertension [112], development of oral leukoplakia [32], pneumonia [146], increased odds of laryngeal cancer [136], ischemic stroke [100] and diabetes mellitus [134]. In addition, tobacco use was associated with having had an injury in the last 12 months [171], emotional abuse [110], and psychological IPV [205]. Longer duration of smoking was associated with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus [73], lower SES [128], and hypertension [98, 142]. Peltzer et al. [181] reported that early smoking initiation among boys was associated with ever drunk from alcohol use, ever used substances, and ever had sex. Among girls, the authors found that early smoking initiation was associated with higher education, ever drunk from alcohol use, parental or guardian tobacco use, and suicide ideation.

Epidemiology of khat use

The epidemiology of khat use was investigated by 34 studies. The lifetime prevalence rate for khat use ranged from 10.7% among general hospital patients [168] to 88% among a community sample [23]. Khat use was associated with being male [114, 168]; unemployment [114]; being employed [25]; younger age (less than 35 years), higher level of income, comorbid alcohol and tobacco use [166] and age at first paid sex of less than 20 years among FSWs [195]. Further, khat use was associated with increased odds of negative health outcomes [130, 146, 166, 201].

Higher odds of reporting psychotic [166, 201], and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) symptoms [201], having thicker oral epithelium [130], and pneumonia [146], were reported among khat users compared to non-users.

Epidemiology of cannabis use

Fourteen studies evaluated the prevalence of cannabis use. The lifetime prevalence rate of cannabis use ranged from 21.3% among persons with AUD [120] to 64.2% among psychiatric patients [110]. Cannabis use was associated with being male [140, 168], and with childhood exposure to physical abuse [110].

Epidemiology of opioid and cocaine use

Twenty-one studies investigated the prevalence of opioid use. The lifetime prevalence rate of opioid use ranged from 1.1% among PLHIV [132] to 8.2% among psychiatric patients [110].

Nineteen studies assessed for the prevalence of cocaine use. The highest reported prevalence rates were 76.2% among PWID use (current use) [190]; 8.8% among healthcare workers (lifetime use) [140]; and 6.7% among PLHIV (lifetime use) [132].

Epidemiology of IDU

One study assessed the prevalence for IDU. Key population size estimates for PWID use was reported as 6107 for Nairobi [164]. IDU was associated with depression, risky sexual behavior [149], Hepatitis-C Virus (HCV) infection [173], and HIV-HCV co-infection [68].

Epidemiology of other substance use (sedatives, inhalants, hallucinogens and prescription medication, emerging drugs, ecstasy)

The epidemiology of sedative use was investigated by 19 studies, inhalant use by 16 studies, hallucinogen use by 7 studies, prescription medication by 4 studies, and emerging drugs and ecstasy by one study each. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for sedative use was reported as 71.4% among a sample of psychiatric patients [28], while the highest prevalence rate for inhalant use was 67% among children living in the streets [86]. The lifetime prevalence rates for hallucinogen use ranged from 1.4% among university students [160] to 3.7% among psychiatric patients [110]. The highest prevalence rate for the use of prescription medication was reported as 21.2% among PWID [190]. One study each reported on the prevalence of emerging drugs [122] and ecstasy [153]. The studies were both conducted among adolescents and youth. The authors found the lifetime prevalence rates for the two substances to be 11.8% [122] and 4.0% [153] respectively.

Other topics explored by the epidemiology studies

In addition to prevalence and associated factors, the epidemiological studies explored other topics.

Papas et al. [176] explored the agreement between self-reported alcohol use and the biomarker phosphatidyl ethanol and reported a lack of agreement between self-reported alcohol use and the biomarker phosphatidyl ethanol among PLHIV with AUD.

One study investigated the self-efficacy of primary HCWs for SUD management and reported that self-efficacy for SUD management was lower in those practicing in public facilities and among those perceiving a need for AUD training. Higher self-efficacy was associated with attending to a higher proportion of patients with AUD, and the belief that AUD is manageable in outpatient settings [196].

Five studies investigated the reasons for substance use. Common reasons for substance use included leisure, stress and peer pressure among psychiatric patients[28], curiosity, fun, and peer influence among college students [123], peer influence, idleness, easy access, and curiosity among adults in the community [25], and peer pressure, to get drunk, to feel better and to feel warm among street children [74]. Atwoli et al. 2011 [72] reported that most students were introduced to substances by friends.

Kaai et al. [99] conducted a study regarding quit intentions for tobacco use and reported that 28% had tried to quit in the past 12 months, 60.9% had never tried to quit, and only 13.8% had ever heard of smoking cessation medication. Intention to quit smoking was associated with being younger, having tried to quit previously, perceiving that quitting smoking was beneficial to health, worrying about future health consequences of smoking, and being low in nicotine dependence. A complete description of the prevalence studies has been provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUDs.

| Author, Year | Study design | Study population/study setting | Sample size | Age; gender distribution | Substance(s) assessed | Standardized tool/criteria used | Main findings (prevalence, risk factors, other key findings) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dhadphale et al. 1982 [12] | Cross-sectional | Students (Secondary school) | 2870 | Age range: 14–20 years Male to female ratio 2:1 |

Alcohol, tobacco, cannabis | None | Prevalence of tobacco use 3 or more times a

week—16.1% Prevalence of alcohol use 3 or more times a week—10.3% Prevalence of cannabis use was 13.5% at a rate of 1 time per month |

| Omolo & Dhadphale 1987 [36] | Cross-sectional | General patients (Hospital) | 100 | Age distribution not reported Males 50% |

Khata | None | Lifetime prevalence khat use was

29%. Mild and moderate chewing significantly associated with age < 20 years (p<0.001) |

| Nielsen et al. 1989 [161] | Cross-sectional | Outpatients (Hospital) | 112 | 18–65 years Males 50% |

Alcohol | DSM-III | 30 patients met the criteria for both

alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. 8 patients received a diagnosis of alcohol abuse only and 6 patients received a diagnosis of alcohol dependence only. 39% of the sample exceeded the cut off score for one or both DSM diagnoses |

| Kaplan et al. 1990 [106] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | Not indicated | Age range: 20–40 years Gender distribution not reported |

Tobacco | None | Highest prevalence lifetime tobacco smoking

was by luo community: 63% males and 67%

females Reasons for smoking: positive feelings, to work harder |

| Hall et al. 1993 [93] | Cross-sectional | General patients (Hospital) | 105 | Mean age: 35.4 years Males 78.1% |

Alcohol | DSM-III-R/ ICD-I0. | Prevalence of weekly alcohol use was 48% |

| Saunders et al. 1993 [188] | Cross-sectional | General patients (Hospital) | Country specific sample size not reported | Country specific demographics not reported | Alcohol | None | Prevalence of alcohol use for Kenya ->40g per day was 43%, and >60g per day was 37% |

| Dhadphale 1997 [27] | Cross-sectional | Psychiatric patients (Hospital) | 220 | Age range: 18–55 years Males 50.9% |

Alcohol | MAST and ICD-9 criteria | Lifetime prevalence of alcohol use among patients with psychiatry morbidity was 12.7% (and 3.1% of those attending outpatient care) |

| Othieno et al. 2000 [168] | Cross-sectional | General patients (Hospital) | 150 | Modal age group: 20–39 years Males 50% |

Alcohol, tobacco, khat, cannabis, methaqualone | DSM IV Criteria | Lifetime prevalence: alcohol use (56.7%),

tobacco use (32%), khat use (10.7%), cannabis use

(5.3%), methaqualone use (0.7%) Alcohol use (p = 0.000), tobacco use (p = 0.000), khat use (p = 0.045), cannabis use (p = 0.004) associated with being male |

| Ayaya et al. 2001 [74] | Case-control | Children living in the streets | 191 | Mean age: 14.03 (SD2.4) Gender distribution not reported |

Alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, glue, cocaine | None | Prevalence for drug abuse was 545 per 1000

children. Specific substance prevalence: tobacco 37.6%; sniffing glue 31.2%; alcohol 18.3%; cannabis 8.3%; and sniffing cocaine 4.6% Reasons for substance use included peer pressure, to get drunk, to feel better and to feel warm |

| Kwamanga et al. 2001 [124] | Cross-sectional | Teachers (School) | 800 | Median age: 35 years, Males 74.5% |

Tobacco smoking | WHO standard self- administered questionnaire | 50% of males and 3% of females reported

tobacco smoking. Peer pressure (63%) and advertisements (21%) are major drivers of smoking |

| Christensen et al. 2009 [81] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 1179 | Mean age: 38.6 years Males 42% |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Tobacco use was 6.6% in females and 16.2%

in males; Alcohol use was 5.4% in females and 20.9% in

males Daily alcohol use in males associated with glucose intolerance (p<0.01) |

| Kwamanga et al. 2003 [125] | Cross-sectional | Students (Secondary school) | 5311 | Mean age: 16.7 years, Males 68.1% |

Tobacco smoking | A WHO standard self- administered questionnaire | Prevalence of current smoking was 10.5%. A

total of 12.4% of male students and 6.4% of female

students were current smokers. Smoking associated with older age (p<0.001), being in a private school (p<0.001). Reduced odds of stopping smoking with increase in number of tobacco smoked (OR 0.22; 95% CI = 0.19, 0.26; p<0.001) |

| Maru et al. 2003 [30] | Cross-sectional | Children and youth (Juvenile court) | 90 | Age range: 8–18 years Males 71.1% |

Alcohol, khat, tobacco, volatile hydrocarbons, sedatives, cannabis | None | Overall prevalence of substance use 43.3%.

Tobacco 32.2%; volatile hydrocarbons 21.1%; cannabis

8.9%; alcohol 6.7%; khat 5.6%; sedatives

3.3% Substance use associated with being male (p = 0.0134) |

| Ogwell et al. 2003 [163] | Cross-sectional | Pupils (Primary school) | 1130 | Mean age: 14.1 (SD 0.9) years Males 52% |

Tobacco | None | Lifetime tobacco use was 31%, lifetime use

of smokeless tobacco was 9%, 55% had friends who

smoked Rates of lifetime smoking higher in urban than in suburban students (p<0.005) |

| Astrom et al. 2004 [71] | Cross-sectional | Pupils (Primary school) | 1130 | Mean age: 14.1 (SD 0.9) years Males 52% |

Tobacco | None | Tobacco smoking; 31% reported ever smoking

tobacco Sources of anti-tobacco messages: broadcast media (47%), Newspapers and magazines (45%), schoolteachers (32%), health workers (29%) |

| Kamotho et al. 2004 [105] | Cross-sectional | Patients undergoing coronary angiography (Hospital) | 144 | Coronary artery disease (CAD): Mean age: 54.4 years, male to female ratio -5.5:1; No CAD: Mean age: 49.8 years, male to female ratio 2.3:1 |

Alcohol, tobacco smoking, | None | CAD: Smoking prevalence 15.4%, alcohol

32.7; No CAD: smoking prevalence 13.0%, alcohol

36.9% There was no difference in prevalence of smoking (p = 0.227) and alcohol use (p = 0.67) between those with CAD and those without |

| Shaffers et al. 2004 [191] | Cross-sectional | General patients (Hospital) | 299 | Mean age: 38 (SD 8) years Males 55% |

alcohol | AUDIT | Prevalence of hazardous drinking 53.5%,

(males 76. %, female 25%), Being male associated with hazardous drinking (p = 0.01) |

| Aden et al. 2006 [23] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 50 | Age range: 15–34 years Males 80% |

Khat | None | Prevalence of khat use was 88% |

| Beckerleg et al. 2006 [76] | Cross- sectional | Adults (Community) | 496 | Age data not given Males 95% |

Heroin | None | Prevalence of lifetime heroin injection was

15%; current injection was 7% Average number of years of heroin use was 11.1 years |

| Macigo et al. 2006 [32] | Case-control | Adults and adolescents (Community) | 226 | Age: 15 years and above Males 100% |

Tobacco | None | Smoking tobacco was associated with development of oral leukoplakia among those who brushed (RR 4.6 95%CI 2.9–5.1 p<0.001) and those who did not brush teeth (RR 7.3 95%CI 3.6–16.3 p<0.001) |

| Cleland et al. 2007 [82] | Cross-sectional | PWID use (Community) | 106 | Mean age (SD): Males 29 [7];

Female 28 [8] Males 87% |

Injection drugs (not specified) | None | Receptive sharing 26% Distributive sharing 41% |

| Kanyanya et al. 2007 [31] | Cross-sectional | Inmates (Prison) | 76 | Mean age: 33.5 years Males 100% |

alcohol | DSM-IV Criteria | 71.1% had lifetime abuse or dependence of alcohol |

| Rudatsikira et al. 2007 [186] | Cross-sectional study | Pupils (Primary school) | 242 | Age: 54.3% aged >15 years Gender distribution: males 55.7% |

Alcohol, tobacco smoking, other drugs (not specified) | None | Lifetime use: alcohol 10.7%, smoking 10.3%,

other drugs 8.4% Past month use: alcohol 9.1%, smoking 6.0% The risk factors for having sex among males were: ever smoked (OR = 2.05, 95%CI 1.92, 2.19), currently drinking alcohol (OR = 1.13, 95%CI 1.06, 1.20), ever used drugs (OR = 2.36, 95%CI 2.24, 2.49) and among females ever used drugs (OR = 2.85, 95%CI 2.57, 3.15). |

| Sanders et al. 2007 [187] | Cross-sectional study | Men who have Sex with Men Exclusively

(MSME) and Men who have Sex with both Men and Women

(MSMW) (Community) |

285 | Median age (IQR): MSME 27 [23–29]; MSMW 28[23–35] all males |

Injection drugs (not specified) | None | Prevalence of IV drug use among MSME was 0.9% and among MSMW was 1.8% |

| Ndetei et al. 2008 [28] | Cross-sectional | Psychiatric Patients (Hospital) | 691 | 78% aged between 21–45 years Males: 63% |

Alcohol, opioid, sedatives, khat | SCID-I for DSM IV | Prevalence substance abuse disorder—34.4%.

Alcohol use disorder (52%), opiate use disorder (55.5%),

sedative use disorder (71.4%), khat use disorder

(58.8%) Leisure, stress and peer pressure were the most common reasons given for abusing substances |

| Ndetei et al. 2008 [152] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 1420 | Mean age: 29.2 years Gender distribution not reported |

Alcohol, tobacco, khat, cocaine, heroin, sedatives, opioids, inhalants, phencyclidine, prescription pills, amphetamines | None | Alcohol use prevalence was 36.3% and

cocaine 2.2% (most and least abused substances

nationally). Prevalence of other substances not

stated. Reasons for substance use: leisure, stress and peer pressure |

| Thuo et al. 2008 [26] | Cross-sectional | Psychiatric Patients (Hospital) | 148 | Mean age: 31 years Males nearly two-thirds |

Alcohol | SCID for DSM IV | More males (n = 39) than

females (n = 6) were abusing substances

(p<0.001); Significant associations between PDs and substance abuse dependence (p<0.001) |

| Komu et al. 2009 [116] | Cross-sectional | Students (University) | 281 | Age data not given Males 60.4% |

Tobacco smoking | None | Prevalence of current tobacco smoking was 12.1% and lifetime prevalence was 38% |

| Ndetei et al. 2009 [153] | Cross-sectional | Students (Secondary school) | 1252 | Mean age: 17 years males 62.5% |

Alcohol, tobacco, amphetamines, sedatives, cannabis, hallucinogens, cocaine, methaqualone, ecstasy, heroin, inhalants. | School Toolkit by UNODC | Lifetime smoking reported by 25,3%, daily

smoking reported by 3.9% Lifetime use: alcohol 19.6%; heroin 4.0%, amphetamines 18.3%, sedatives 7.0%, cannabis 7.1%, hallucinogen 4.1%, cocaine 4.2%, mandrax 4.0%, ecstasy 4.0%, inhalants 6.6% Age at first use as low as below 11 years |

| Ndetei et al. 2009 [154] | Cross-sectional | Students (Secondary school) | 1328 | Mean age: 16 years Males 58.9% |

Not specified | DUSI-R | Prevalence of substance abuse was 33.9% but

substances not specified Substance use associated with psychiatric morbidity, school performance, social competence, peer relations, involvement in recreation, behavior problems (p<0.001 in each case). |

| Nguchu et al. 2009 [159] | Cross-sectional | Patients with diabetes (Hospital) | 400 | Mean age: 63.3 years Males 60% |

Tobacco smoking | None | Prevalence of tobacco smoking was 8.4% |

| Peltzer et al. 2009 [180] | Cross-sectional | Students (School) | 2758c | 13–15 years Country specific gender distribution not reported |

Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs (not specified) | Global School-Based Health Survey questionnaire | Prevalence tobacco use 17.5%, illicit drug use 9.5%, risky drinking 4.7% |

| Ndetei et al. 2010 [34] | Cross-sectional | Students (Secondary school) | 343 | Mean age: 16.8 years Males 64.1% |

Alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, khat, cocaine, heroin | None | Alcohol, tobacco, khat and cannabis were

the most commonly reported substance of use, with user

prevalence rates of 5.2%, 3.8%, 3.2%, and 1.7%, respectively. |

| Tegang et al. 2010 [195] | Cross-sectional | FSWs (Community) | 297 | Median age 25 (IQR 21–29) All female |

Tobacco smoking, khat, alcohol, heroin | None | Lifetime prevalence:91% for alcohol, 71%

for khat, 34% for cannabis, and 6% for

heroin, cocaine, glue or petrol. Lifetime prevalence of at least one substance was 96%, at least two substances 80% Lifetime use khat associated with age at first paid sex of <20 years (p<0.01); lifetime use tobacco associated with engagement in sex work of >5years (p<0.05); lifetime use heroin/cocaine/ glue/petrol associated with sex with 2 or more partners (p<0.005). |

| Atwoli et al. 2011 [72] | Cross-sectional | Students (University) | 500 | Mean age: 22.9 (SD2.5) Males 52.2% |

Alcohol, tobacco | WHO Model Core Questionnaire | Alcohol use: lifetime prevalence was 51.9%;

Current prevalence was 50.7%; Among those using alcohol,

50.4% used 5 or more drinks per day, on 1 or 2 days and

9.2% used for3 or more days. Lifetime tobacco smoking was 42.8%; cannabis (2%), cocaine (0.6%). Tobacco use higher among males compared to females (p < 0.05). 75.1% introduced to substances by a friend Reasons for use: to relax (62.2%) or relieve stress (60.8%). |

| Kinoti et al. 2011 [114] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 217 | Mean age: 34.2 years males 70.5% |

Alcohol, khat | None | Prevalence of use for bottled beer: 64.8%;

local brew– 41.6%; khat chewing– 41.6%; cannabis

-13.7% Males significantly more likely to use bottled beer (p<0.01) and local brew (p<0.01) and khat (p<0.01) Unemployment associated with use of bottled beer (p<0.05) and local brew (p<0.01) and khat (p<0.01) |

| Luchters et al. 2011 [129] | Cross-sectional | MSW (Community) | 442 | Mean age: 24.6 (SD 5.2) All males |

Alcohol and others (Khat, rohypnol, heroin or cocaine) | AUDIT | Alcohol: overall prevalence of use 70%; 35%

of participants who drink had hazardous drinking, 15%

harmful drinking and 21% alcohol

dependence. Binge drinking prevalence of 38.9% Prevalence of other substances (khat 75.5%, cocaine/heroin 7.7%, rohypnol 14.9%) Alcohol dependence was associated with inconsistent condom use (AOR = 2.5, 95%CI = 1.3–4.6), penile or anal discharge (AOR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.0–3.8), and two-fold higher odds of sexual violence (AOR = 2.0, 95%CI = 0.9–4.9). |

| Muture et al. 2011 [148] | Case-control | Cases were patients on treatment for tuberculosis (Hospital) | 1978 cases and 945 controls | Mean age/age range: mean 31.2 years for

cases and 29.5 years for controls Males 59.4% in cases and 53% of controls |

Alcohol | None | Alcohol abuse was found to be a predictive factor for defaulting from TB treatment (OR 4.97; CI 1.56–15.9). |

| Ndugwa et al. 2011 [156] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents living in an informal settlement (community) | 1722 | Mean age: 12–19 years Males 47.2% |

Alcohol, tobacco, miraa, glue illicit drugs (not specified) | MPBI | Lifetime prevalence of alcohol use was 6.0%; tobacco smoking was 2.6%; other illicit drugs (not specified) 6.8% |

| Peltzer et al. 2011 [181] | Cross-sectional | Pupils (Primary school) | Mean age/range: 13–15 years Gender distribution: 47.7% |

Tobacco smoking | GSHS core questionnaire | Lifetime smoking prior to age 14 years

reported by 15.5% (20.1% boys and 10.9%

girls) early smoking initiation was among boys associated with ever drunk from alcohol use (OR = 4.73, p = 0.001), ever used drugs (OR = 2.36, p = 0.04) and ever had sex (OR = 1.63, p = 0.04). Among girls, it was associated with higher education (OR = 5.77, p = 0.001), ever drunk from alcohol use (OR = 4.76, p = 0.002), parental or guardian tobacco use (OR = 2.83, p = 0.001) and suicide ideation (OR = 2.05, p = 0.02) |

|

| Embleton et al. 2012 [85] | Cross-sectional | Children living in the streets | 146 | Age range: 10–19 Males 78% |

Alcohol, glue, tobacco, cannabis, khat, prescription medication, petrol | None | Lifetime substance use was 74%, current

substance use was 62% Lifetime and current prevalence for specific substances respectively was: glue 67%, 58%; alcohol 47%, 16%; tobacco 45% 21%; khat 33%,7%; cannabis 29%,11%; petrol 24%,5%; and pharmaceuticals 8%,<1% Factors associated with having any lifetime drug use were increasing age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.15–1.87), having a family member who used alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs (AOR = 3.43, 95% CI = 1.15–10.21), staying in a communally rented shelter (AOR = 3.64, 95% CI = 1.13–11.73), and being street-involved for greater than 2 years (AOR = 3.69, 95% CI = 1.22–11.18). |

| Kuria et al. 2012 [120] | Cross-sectional | Persons with alcohol use disorder in an informal settlement (community) | 188 | Mean age: 31.9 years Male 91.5% |

Alcohol | CIDI, ASSIST and AUDIT | Tobacco—50% of the

participants Cannabis—21.3% There was a statistically significant association (P value 0.002) between depression and the level of alcohol dependence at intake. And at 6 months |

| Menach et al. 2012 [136] | Case-control | Cases were adults with laryngeal cancer (Hospital) | 100 (50 cases, 50 controls) | Mean age: 61years in cases and 63years in

control group 96% males |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Being a current smoker

increased laryngeal cancer risk with an odds ratio (OR) of 30.4 (P < 0.0001; 95% CI: 8.2–112.2). |

| Ndetei et al. 2012 [155] | Cross-sectional | Psychiatric Patients (Hospital) | 691 | Schizoaffective disorder: Mean age 33.1 years; Males 52.2% Schizophrenia mean age: 33.5 years; Males:62.9% Mood disorders: mean age 33.2 years; Males: 58.4% |

Alcohol, drugs (not specified) | SCID-I for DSM IV | Comorbidity with alcohol dependence disorder was more common in schizoaffective disorder than with schizophrenia (p = 0.008) |

| Ayah et al. 2013 [73] | Cross-sectional | Adults living in informal settlements (community) | 2061 | Mean age 33.4 years Males 50.9% |

Alcohol, tobacco | WHO STEPS survey instrument | Tobacco use Current smoking 13.1% of whom 84.8% were daily smokers. The mean age of smoking commencement and duration of smoking was 19.7 years and 16.5 years Respectively Alcohol use Lifetime prevalence 30%, of whom 74.9% used in past 12 months and 62.2% in the previous 30 days Daily use was 19.7% and use 1–6 days per week among 43.4% Duration of smoking (p = 0.001) and number of pack years(p = 0.049) associated with diagnosis of diabetes |

| Embleton et al. 2013 [86] | Mixed-methods (cross-sectional and qualitative) | Children living in the streets | 146 | Age range: 10–19 years males 85% |

Alcohol, glue, tobacco, khat, cannabis, petrol, prescription medication | None | Prevalence of substance use was as follows: glue 67%; alcohol 47%; tobaccos 45%; khat 33%; cannabis 29%; petrol 24%; and pharmaceuticals 8%; |

| khasakala et al. 2013 [108] | Cross-sectional | Youth attending an out-patient clinic (Hospital) | 250 | Mean age: 16.92 years Males 59.1 |

Alcohol, other substances (not specified) | MINI (DSM IV) | Any drug use prevalence was

62.4% Alcohol abuse prevalence was 47.8% associations between major depressive disorders and any drug abuse (OR = 3.40, 95% CI 2.01 to 5.76, p < 0.001), or alcohol use (OR = 3.29, 95% CI 1.94 to 5.57, p < 0.001), |

| khasakala et al. 2013 [109] | Cross-sectional | Youth and biological parents attending a youth clinic (Hospital) | 678 (250 youth, 226 biological mothers, 202 biological fathers) | Mean age youth 16.92years males 59.1% (youth) |

Alcohol, other substances (not specified) | MINI (DSM IV) | Alcohol use—46.8% of youth, 1.2% mothers

and 39.2% of fathers Multiple drug use identified in 9% of youth Significant statistical association between alcohol abuse (p <0.001), substance abuse (p < 0.001) and suicidal behaviour in youths. |

| Kinaynjui & Atwoli 2013 [115] | Cross-sectional | Inmates (Prison) | 395 | Mean age: 33.3 years Males 68.6% |

Alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, tranquillizers, cocaine, heroin. | WHO Model Core questionnaire | Lifetime prevalence of any substance use

was 66.1% Lifetime prevalence: alcohol 65.1%, tobacco use 32.7%, tobacco chewing 22.5% admitted to chewing tobacco, cannabis 21%, amphetamines (9.4%), volatile inhalants (9.1%), sedatives (3.8%), tranquillizers (2.3%), cocaine (2.3%), and heroin (1.3%). Substance use associated with male gender (p<0.001), urban residence (p<0.001). |

| Lo et al. 2013 [128] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 72292 | Modal age group: 18–29 years males 43.1% |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Prevalence of ever smoking was 11.2% and of

ever drinking, 20.7%. Percentage of current smokers rose with the number of drinking days in a month (P < 0.0001). Tobacco and alcohol use increased with decreasing socio-economic status and amongst women in the oldest age group (P < 0.0001). |

| Mundan et al. 2013 [142] | Cross-sectional | Military personnel attending a clinic (Hospital) | 340 | Mean age: hypertensives 45.1(SD 7.7);

normotensive 40.8 (SD 7.3) Males 91.6% |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Alcohol use in 63% of hypertensive patients and 52.07% of normotensive patients Smoking prevalence was 11% among those with hypertension and 4.2% among normotensives. hypertension associated with daily (P < 0.01) and 1–3 times per week (P < 0.05), consumption of alcohol daily Smoking duration is significantly (P < 0.05) longer among participants with hypertension compared to normotensives. |

| Njoroge et al. 2017 [162] | Cross-sectional study | ART-naïve HIV-1 sero-discordant couples attending a clinic (Hospital) | 196 (99 HIV-infected and 97 HIV-uninfected) | Median age 32 years Males 50% |

Tobacco, smoking | None | Smoking: prevalence among those HIV positive was 10% current and past was 22%; among those HIV negative was 11% current and 9% past |

| Njuguna et al. 2013 [25] | Cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 75 | Mean age: 28.3 Males 100% |

Khat | None | Overall prevalence of khat use was 68% Khat

use was associated with being employed (OR = 2.8, 95% CI

1.03–7.6) Reasons for starting to chew khat included peer influence (40.4%), idleness (23.1%), easy access to khat (19.2%), and curiosity (17.3%) |

| Okal et al. 2013 [164] | A combination of ‘multiplier method’, the ‘Wisdom of the Crowds’ (WOTC) method and a published literature review. | MSM, PWID, FSWs (Community) | Not reported | Age and gender distribution data not given | Injection drugs (not specified) | None | Approximately 6107 IDU and (plausibly 5031–10 937) IDU living in Nairobi. |

| Patel et al. 2013 [179] | Case-control | Cases were adults with oesophageal cancer (Hospital) | 159 cases and 159 controls | Mean age for males 56.09 years and females

was 54.5 years Males 57.9% |

Alcohol, snuff, tobacco smoking | None | Smoking, use of snuff and alcohol were associated with increased risk of esophageal cancer (OR = 2.51, 4.74 and 2.64 respectively) |

| Ploubidis et al. 2013 [184] | cross-sectional | Adults (Community) | 4314 | Mean age: 60.8 years Males 49.2%% |

Alcohol, tobacco smoking | None | Prevalence of alcohol was 17.7% and smoking prevalence was 6.8% |

| Balogun et al., 2014 [75] | cross-sectional | Pupils (Primary School) | 3666 | Age range: 13–15 years Males 49.1% |

Alcohol | None | Past 30-day alcohol use was

17.9% Lifetime drunkenness was 22.5% Past 30-day alcohol use associated with increased odd sleeplessness; Lifetime drunkenness associated with both depression and sleeplessness |

| Bengston et al., 2014 [77] | Cross-sectional | FSWs (Community) | 818 | Age distribution: 30% aged 18–23 All female |

Alcohol | AUDIT | Prevalence of hazardous drinking was 64.6%;

harmful drinking was 35.5% Higher levels alcohol consumption associated with having never tested for HIV (PR 1.60; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.40). |

| Chersich et al., 2014 [80] | Cross-sectional | FSWS (Community) | 602 | Mean age: 25.1 years Female 100% |

Alcohol | AUDIT | Prevalence of hazardous drinking was 17.3%

and harmful drinking was 9.3% Harmful drinking associated with increased odds sexual (95% CI adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.9–8.9) and physical violence (95% CI AOR = 3.9–18.0); while hazardous drinkers had 3.1-fold higher physical violence (95% CI AOR = 1.7–5.6). |

| De Menil et al., 2014 [83] | Cross-sectional | Psychiatric patients (Hospital) | 455 | Mean age/range: 36.3 years Gender distribution: males 66.4 |

Alcohol, other substances (not specified) | None | Prevalence of alcohol use disorder was 21.2% and other drug use was 10.4% |

| Joshi et al., 2014 [98] | cross-sectional | Adults living in informal settlements (Community) | 2061 | Mean age: 33.4 (SD 11.6) years Males 50.9% |

Alcohol, tobacco | WHO STEPS | Alcohol use: 30.1% reported lifetime

alcohol use; 81% alcohol use in past 12 months; 76.8%

reported using alcohol in the past 30 days; harmful use

by 52% Tobacco: 13.1% reported current smoking (84% of whom used daily) Current smoking (p = 0.018), years of smoking (p = 0.001) associated with having hypertension |

| Medley et al., 2014 [135] | Cross-sectional | PLHIV (Hospital) | 1156 | Mean age: 37.2 Gender distribution not reported |

Alcohol | None | Overall, 14.6% of participants reported alcohol use in the past 6 months; 8.8% were categorized as non-harmful drinkers and 5.9% as harmful/likely dependent drinkers. Binge drinking reported in 5.4% |

| Othieno et al., 2014 [169] | Cross-sectional | Students (University) | 923 | Mean age: age 23 (SD4.0) males 56.9% | Alcohol, tobacco | None | Students who used tobacco (p = 0.0001) and engaged in binge drinking (p = 0.0029) were more likely to be depressed |

| Pack et al., 2014 [174] | Cross-sectional | FSW (Community) | 619 | 18 years and older Female 100% |

Alcohol | AUDIT Tool not specified for other drug use |

Hazardous alcohol use 36.0%; harmful alcohol use 64.0%; other drug use 34.1% |

| Were et al., 2014 [199] | Cross-sectional | PWID (Community) | 61 | Age range: 29–33 years Gender distribution: not reported |

Brown sugar, rohypnol, khat, tobacco, cocktail, alcohol, injection drugs (heroin, diazepam) | None | Prevalence of substance use was as follows: 43%, brown sugar 16%, rohypnol 61%, tobacco 61%, khat 26%, cocktail 39%, alcohol 52%; injection drugs heroin 100%, diazepam 18% |

| Widmann et al., 2014 [201] | Case-control | Cases were male khat chewers (Community) | 48 (cases = 33, controls = 15) | Mean age: 34 years for cases, 35.1 for

controls Males 100% |

Alcohol, khat, tobacco, tranquilizers | MINI | Khat chewers experienced more traumatic event types than non-chewers (p = 0.007), more PTSD symptoms than non-chewers (p = 0.002) and more psychotic symptoms (p = 0.044). |

| Goldblatt et al., 2015 [91] | Cross-sectional | Children living in the streets | 296 | Age range: 13-21years All males |

Alcohol, tobacco, khat, glue, fuel | None | Weekly alcohol use reported by 49%;93% reported weekly tobacco use; and 39% reported weekly Cannabis use; 46% reported lifetime use of glue; 8% reported lifetime inhalation of fuel |

| Hulzelbosch et al., 2015 [96] | Cross-sectional | Persons with hypertension in an informal settlement (Community) | 440 | Age: 35 years and above males 42% |

Alcohol, tobacco, khat, glue, fuel | WHO STEPS survey instrument | Tobacco use: current 8.4%, former

11.8% Alcohol use: low 84.8%, moderate 6.8%, high 8.4% |

| Kurth et al., 2015 [121] | Cross-sectional | PWID (Community) | 1785 | Mean age 31.7 years in Coast and 30.4 in

Nairobi Males 82.4–89.0% |

Injection drugs (heroin) | None | 93% injected heroin in the past 30 days. |

| Lukandu et al., 2015 [130] | Case-control | Cases were dental patients (Hospital) | 42 (34 cases, 8 controls) | mean age 28.9 years all males |

Alcohol, khat, tobacco, | None | Oral epithelium thicker in khat chewers compared non-chewers (p<0.05); |

| Maina et al., 2015 [132] | Cross-sectional | PLHIV (Hospital) | 200 | Modal age group 34–41 years

(27.4%) males 49.7% |

Alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, opioids, hallucinogens, others (not specified) | ASSIST, ASI | Lifetime prevalence of any substance use

was 63.1%; alcohol 94.4%; tobacco 49.7%; cocaine 6.7%;

amphetamine type stimulants 19.6%; inhalants 3.4%;

sedatives 1.7%; opioids 1.1%; hallucinogens 6.6%; others

4.2% 50.3% wrongly identified the alcohol use vignette problem as stress |

| Micheni et al., 2015 [33] | Cohort | MSM and FSW (Community) | 1425 | Median age was 25 for MSM and 26 for

FSW Males 50.9% |

Alcohol, injection drugs (not specified) | None | Recent alcohol use was associated with reporting of all forms of assault by MSM [(AOR) 1.8, CI 0.9–3.5] and FSW (AOR 4.4, CI 1.41–14.0), |

| Muraguri et al., 2015 [144] | Cross-sectional | MSM (Community) | 563 | MSM who did not sell sex: 30% in the 35 and

older age group; MSM who sell sex: 30.8% in the 25–29

age group Males 100% |

Alcohol, illicit drugs (not specified) |

AUDIT for alcohol use; tool not specified for illicit substances | 62.9% of MSM who did not sell sex had used illicit drugs in the past 12 months while those who sold sex were 78.7%. Possible alcohol dependence was 21.4% among those who did not sell sex while those who sold sex were 33%. |

| Olack et al., 2015 [165] | Cross-sectional | Adults living in informal settlements (Community) | 1528 | Mean age: 46.7 years Males 42% |

Alcohol, tobacco smoking | WHO STEPS survey questionnaire | Prevalence of smoking: Current smokers 8.5%

and past Smokers 5.1%; Alcohol: Ever Consumed was 30.4%; In the past 12 months was 17% and In the past 30 days was 6.5% |

| Onsomu et al., 2015 [167] | Cross-sectional | Adult women (Community) | 2227 | Age range not reported Females 100% |

Alcohol use in husband | None | 385 of women reported that husband uses alcohol |

| Othieno et al., 2015 [170] | Cross-sectional | Students (University) | 923 | Mean age: age 23 (SD4.0) Males 56.9% |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Alcohol use (p<0.001), binge drinking (p<0.01), tobacco use (p<0.001), were significantly associated with increased odds of having multiple sexual partners. |

| Othieno et al., 2015b [171] | Cross-sectional | Students (University) | 923 | Mean age: age 23 (SD4.0) Males 56.9% |

Alcohol, tobacco | None | Prevalence of binge drinking was 38.85%;

Tobacco use prevalence not reported Binge drinking and tobacco use were significantly associated with injury in the last 12 months (AOR 5.87 and 4.02, p<0.05, respectively) |

| Secor et al., 2015 [189] | Cross-sectional | MSM Community) | 112 | Median age: 26 years Males 100% |

Alcohol, other drugs (not specified) | AUDIT, DAST | Prevalence of hazardous or harmful alcohol

use was 45%; prevalence harmful use of other drugs