Abstract

Synthetic carbohydrate receptors (SCRs) that bind cell-surface carbohydrates could be used for disease detection, drug-delivery, and therapeutics, or for the site-selective modification of complex carbohydrates but their potential has not been realized because of remaining challenges associated with binding affinity and substrate selectivity. We have reported recently a series of flexible SCRs based upon a biaryl core with four pendant heterocyclic groups that bind glycans selectively through noncovalent interactions. Here we continue to explore the role of heterocycles on substrate selectivity by expanding our library to include a series of indole and quinoline heterocycles that vary in their regiochemistry of attachment to the biaryl core. The binding of these SCRs to a series of biologically-relevant carbohydrates was studied by 1H NMR titrations in CD2Cl2 and density-functional theory calculations. We find SCR030, SCR034 and SCR037 are selective, SCR031, SCR032, and SCR039 are strong binders, and SCR033, SCR035, SCR036, and SCR038 are promiscuous and bind weakly. Computational analysis reveals the importance of C−H⋯π and H-bonding interactions in defining the binding properties of these new receptors. By combining these data with those obtained from our previous studies on this class of flexible SCRs, we develop a series of design rules that account for the binding of all SCRs of this class and anticipate the binding of future, not-yet imagined tetrapodal SCRs.

Keywords: Carbohydrates, computational chemistry, host-guest system, molecular recognition, supramolecular chemistry

Graphical Abstract

The effects of regiochemistry of attachment and structure of heterocyclic groups on the binding between synthetic carbohydrate receptors (SCRs) and a series of carbohydrates was studied. This resulted in design rules that anticipate how structural modifications affect SCR binding affinity and specificity.

Introduction

Interactions that occur on the cell surface have a central role in regulating many important biological processes, including cell−pathogen interactions, immune response, cell-cell communication, and disease progression [1]. These processes are mediated by cell-surface glycoproteins, glycolipids, and glycopolymers, and glycans expressed in the glycocalyx are unique identifiers of cell type that can indicate disease and could serve as drug targets. For example, in gastric cancer [2], liver cancer [3], and breast cancer [4], there is an overexpression of mannose and mannose receptors. While N-acetylgalactosoamine is overexpressed in colorectal cancer [5], and β-galactose and N-acetylglucosamine are prevalent on the surface of malignant melanoma cells [5–6]. Enveloped viruses are also surrounded by a glycosylated lipoprotein bilayer with unique glycosylation patterns [7]. For example, α−mannose is abundant on the surfaces of various infectious viruses like Flaviviridae [8], Coronaviridae[9], and Filoviridae [10], the former of which is responsible for the recent Zika virus outbreak in 2016 [11] and the ongoing pandemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 that is responsible for the deaths of millions of people [9]. For many of these cancers and viruses, there is still a need for effective treatments that halt the progression of disease, and molecules that can bind the glycans on cancer cells and viruses could be used for early detection of the disease biomarkers or as drug delivery agents, as anticancer and antiviral treatments, or as catalysts and ligands for the site-selective transformation of complex glycans.

Glycan binding proteins (GBPs) and antibodies recognize cell-surface glycans [12], but they are not useful in the context of detection, delivery, therapy, or catalysis for a number of reasons. GBPs have a relatively weak affinity for monosaccharides, with dissociation constants that are typically in the millimolar range [13]. Their shallow binding pockets, which are exposed to competitive solvent interactions, accounts for this weak association [13]. Development of highly selective antigen/antibodies has been hindered as a result of the poor immune response of carbohydrates and the structural similarities of different carbohydrates [13]. In addition, the toxicity [13] of both limit their use as therapeutic agents [13]. There are currently only two glycan-binding antibodies which are in clinical trials, and only one, which is for treating high-risk childhood neuroblastoma [14], has received FDA approval. Another approach that is currently being explored to achieve specific glycan-binding is by developing aptamers [15] and peptide-based receptors [16], but aptamer specificity towards glycan targets has not yet been achieved [17]. In summary, even though cell- and viral-surface glycans are known to have a role in disease progression, few strategies exist to exploit this information clinically [18] or catalytically [19], and until such strategies are developed, cell surface glycans will continue to be considered “undruggable targets”, and whose preparation by total synthesis remains a major challenge [20].

Synthetic carbohydrate receptors (SCRs) are small molecules that form complexes with glycans, and are a promising route to exploiting carbohydrate recognition for clinical and catalytic applications [21]. If these small molecules could selectively bind glycans common to the surface of pathogens or diseased cells, they could be used in the context of disease detection, drug delivery, or therapeutics [21e, 22]. Alternatively, knowledge of their binding conformations could be used for developing supramolecular protecting groups, and thereby lead to methods for the site-selective modification of the hydroxyl groups on complex carbohydrates [19]. A major advantage of small molecule receptors over antibody, GBP, or other biologically-derived receptors is that their structures can be easily tuned using the tools of organic synthesis to modulate substrate selectivity or to mitigate toxicity. Several SCRs have recently been reported to undergo binding with biologically relevant glycans. Most SCRs, however, preferentially bind glucosides – the all-equatorial glycosides that are prevalent in the blood and cytoplasm in high concentration but almost entirely absent on the cell surface – and for SCRs to migrate through blood and associate with glycans on the cell surface or offer versatile catalytic strategies, they need to preferentially bind non-glucosides [5, 23].

SCRs fall primarily into two categories – those that bind sugars covalently and those that bind sugars entirely through noncovalent interactions. In the former case, covalent binding takes place through the formation of boronate esters [21b, 24] by the reaction between boronic acid groups on the SCRs and syn-diols of monosaccharides like D-fructose, D-glucose (Glc), D-mannose (Man), D-galactose (Gal), and D-arabinose [24a, 25]. Noteworthy examples are the chiral diboronic acid receptors by Shinkai that bind D-Fructose and D-Glc with Ka values of ~ 104 M−1 in phosphate buffer at pH 7.77 with 33% MeOH [26]. However, boronic acid SCRs typically require alkaline pH to drive bond formation and some biological substrates may not be compatible with these conditions. Also boronic acids tend to bind carbohydrate molecules in the furanose form as opposed to the pyranose form in which biologically relevant carbohydrates are primarily found [13].

Noncovalent SCRs bind as a result of H-bonding, C−H⋯π interactions, and van der Waals forces, and, while many still bind glucosides, a number of noncovalent SCRs with non-glucosidic binding have been recently reported. The noncovalent SCRs can be segregated into rigid and flexible molecules. In rigid SCRs, preorganization reduces the entropic penalty of binding. These rigid noncovalent SCRs include cyclodextrins [27], calixarenes and oligoaromatic receptors [28], porphyrin conjugates [29], cholaphanes[30], podand receptors [31], and encapsulating temple receptors [21e, 32]. The “temple receptors” described by Davis et al. preferentially bind to glucosides and other all-equatorial glycan derivatives with Kas as high as 3.0 × 105 M−1 in CHCl3 and 1.2 × 104 M−1 in H2O [21c]. Mazik [21d, 33] and Roelens [21f, 31a–c, 31e, 31f, 31h, 31k–m, 34] have also reported several rigid noncovalent SCRs with non-glucosidic selectivity.

Generally, synthetic receptors are modeled after rigid proteins, and, following the dictates of Cram’s principle of preorganization, are designed intentionally to be rigid to reduce the entropic penalty that is incurred upon binding [35]. Natural GBPs, however, do not necessarily follow this traditional ‘lock-and-key’ binding model, and the flexible Glc/Gal periplasmic binding protein achieves selectivity by accessing multivalent and cooperative binding modes that arise upon conformational rearrangement [36]. As such, these flexible GBPs suggest that a different paradigm may be more appropriate for the design of SCRs that are intended to bind non-glucosidic carbohydrates, where structural flexibility is intentionally incorporated into the receptor structure [37]. To this end, our group has reported a series of noncovalent SCRs based upon a biaryl framework with four pendant heterocyclic arms appended to the core by secondary amine linkages [37–38]. These molecules are intended to bind glycan targets via H-bonding and C−H⋯π interactions. The binding of the first of these tetrapodal receptors, SCR001, with monosaccharides was studied in CDCl3 and CH2Cl2, which were chosen as solvents to maximize the strength of noncovalent interactions, and SCR001 showed a slight preference for mannosides [38b, 38c]. Since then, we have made a series of these tetrapodal SCRs that vary the nature of the heterocycle, the binding between the heterocycle and the biaryl core, and the receptor valency [37–38]. The result of these studies is a library of SCRs with varying binding affinities and selectivities. Noteworthy among these was SCR018, whose heterocycle is an indole linked to the core at the 2-position that bound α-Man [38a] strongly and specifically. α-Man is a particularly important carbohydrate because of its prevalence on the surfaces of viruses [8–10] and cancer cells [2–4]. In parallel to the binding studies, we recently demonstrated ability of these flexible SCRs to inhibit viral infection, including Zika virus, with nanomolar IC50 values [39].

Given both the remarkable selectivity and antiviral activity of these compounds, we chose to continue expanding this library of tetrapodal SCRs in an effort to develop design rules that anticipate substrate selectivity and binding affinities for future use as antivirals, drug-delivery agents, or as catalysts/ligands in glycan synthesis. Indoles are abundant in nature and they play an important role in cell biology and are found in various medically-relevant natural products [40], and several indole derivatives are currently being explored for their antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-HIV, antioxidant, antimalarial, and antitubercular activities [41]. Taken together, these led us further explore how indole structure affected SCR binding affinity and selectivity. Here we report the addition of ten new SCRs (SCR030 – SCR039) that contain indole and quinoline heterocycles. The binding between these molecules and a series of biologically−relevant carbohydrates was investigated to determine the role of the regiochemistry of heterocyclic binding on binding affinity and substrate selectivity. Using these data, we report a series of guidelines that anticipate how structural modifications affect the association between SCRs and carbohydrates in future tetrapodal SCRs.

Results

SCR030 – SCR039 (Scheme 1A) are prepared by reacting heterocyclic aldehydes with 1 in yields ranging from 30 to 90 % using our previously reported three−step, one−pot protocol [38c]. In this method, an iminophosphorane intermediate is formed by the Staudinger amination of tetraazide 1, which is then followed by an aza−Wittig reaction with the corresponding heteroaryl aldehyde to form an imine. Reduction of the imine with NaBH4 results in the desired tetrapodal SCR. These SCRs vary in the position of attachment of the heterocycles, but they still maintain the secondary amine groups and C2h symmetry of previously reported tetrapodal SCRs. All structures were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and high−resolution mass spectrometry, and these data are all consistent with the proposed structures.

Scheme 1.

A) Preparation of SCR030 – SCR039 from 1 using corresponding heterocyclic aldehydes in 30 − 90% yields. B) Octyloxy pyranosides used to study binding with SCRs.

Determination of Ka values by NMR titrations

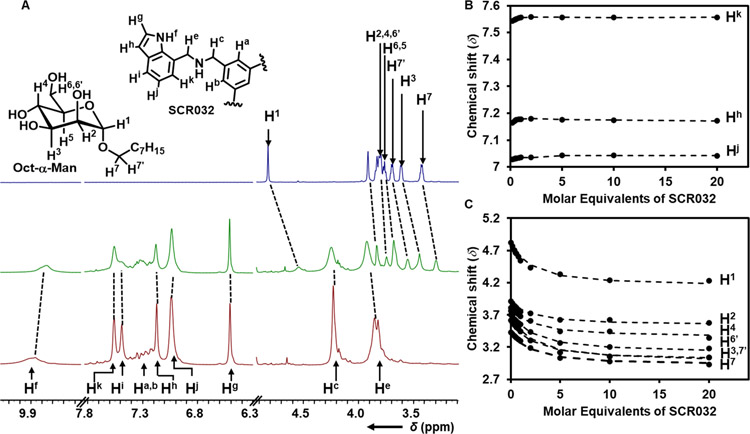

1H NMR titrations were performed to study the interactions between octyloxy pyranosides and the SCRs to calculate their association constants (Kas) and selectivities. NMR was selected as the analytical method because it is generally suitable to quantify host-guest binding processes whose Kas range from 1 to 105 M−1 [42]. To prevent competition caused by H-bonding with the chemical environment, the nonpolar organic solvents CD2Cl2 was used in lieu of an aqueous solvents to strengthen association [21d, 22a, 31, 32j, 33–34, 43]. We have also shown previously that some of these tetrapodal SCRs dimerize [38a], and it is essential to determine the strength of this self-association and account for this interaction to quantify accurately Kas between the carbohydrates and the SCRs. To do so, dilution experiments were performed on SCR030 – SCR039 by examining peak shifting at a concentration range of 20 mM − 200 μM to determine if dimerization occurs. When peak shifting occurred, these data were fit to a dimerization model to determine the dimerization constant (Kd). To prevent errors in calculating Kds, data were only fit if the titrations included at least two peaks in the spectrum that displayed a change in chemical shift (Δδ) >0.02 ppm (see Supporting Information) [38b]. Dimerization was observed for SCR030, SCR032, and SCR034. Following the dilution experiments, the 1H NMR titrations were performed by adding 4.5 μL aliquots of 20 mM solutions of an SCR to 450 μL (1 mM) solutions of octyloxy glycan and continuing to add aliquots until a 20:1 SCR:glycan ratio was achieved. As an illustrative example, the 1H NMR spectra showing the addition of SCR032 to a solution α-Man is presented in Figure 1A. For α-Man, the largest Δδ occurred with the peak corresponding to H7’, with Δδ = 0.66 ppm upfield, and the second-largest shift was for the peak corresponding to H1, with Δδ = 0.59 ppm upfield. When involved in C−H···π interactions with aryl rings of SCRs, protons shift upfield [21c, 31, 32i, 32j, 33a–i, 34a, 43b–o], suggesting the formation of C−H···π interactions between these protons and with the aromatic rings of SCR032. 1H NMR of the indole-based SCR’s in all the titrations presented significant downfield shifts. Meanwhile, for the quinoline-derived SCRs, glycan peaks shift upfield exclusively upon mixing.

Figure 1.

A) 1H NMR (800 MHz, CD2Cl2, 298 K) of α-Man (1 mM, top), a 1:1 ratio of SCR032•α-Man (middle), and SCR032 (20 mM, bottom). Shifts in the peaks after adding SCR032 to α-Man are shown by dashed lines. B) NMR peak shift for SCR032 protons Hk, Hh, Hj at 298 K, experimental data and fit from 1:1 SCR:glycan binding is shown by bullets and dashed lines C) NMR peak shift for α-Man protons H1, H2, H4, H6, H3, H7’, H7 upon addition of SCR032 in CD2Cl2 at 298 K experimental data (bullets), and the fit from 1:1 SCR:glycan binding is shown (dashed lines).

Kas for the host-guest binding between SCRs and glycans were quantified from these NMR titrations. Kas were determined by fitting the Δδ to binding models that considered all the different possible equilibria. For example, we have shown previously that the SCRs can dimerize and that SCR001 can form 1:1, 2:1, and 1:2 complexes with β-Man in CDCl3 [38c] and CD2Cl2 [38b]. All these various equilibria are considered when fitting the titration data by minimizing the sum of least squared residuals (SSRs) between the experimental data and the modelled fit. To maximize the accuracy of the Ka values, NMR peak shift data of only clearly resolved peaks of glycans and SCRs that shifted at Δδ > 0.02 ppm were fit, following previously reported selection protocols [38b]. All potential fits were generated simultaneously, and an appropriate binding model that had the lowest SSR with the titration given data was chosen as the correct equilibrium. To avoid overestimation of Kas, no binding values are reported for Kas < 3.0 × 101 M−1 and for NMR peaks shift < Δδ = 0.02 ppm. Unless 2 peaks in the 1H NMR spectra have Δδ > 0.02 ppm, the SCRs would be assumed to not interact with the glycans upon mixing. It should be noted that many peaks with Δδ > 0.02 ppm could not be used to calculate Ka values because they overlapped with other peaks in the spectra and could not be tracked accurately. To quantify the error in the NMR measurements, the titrations between SCR019 and β-Man were performed in triplicate, and the error, reported as one standard deviation from the mean in Ka, was 15 % [38a]. To demonstrate the data analysis, the NMR peak shift data for the association of SCR032 with α-Man are shown (Figure 1B & C). The peak shifts were best fit with a 1:1 SCR:glycan binding model with Kd, of 1.5 × 102 M−1 and K1 of 5.1 × 102 M−1, where Kd and K1 correspond to self-association and 1:1 SCR:glycan Kas, respectively. Based on the NMR titration data, we determined that the SCRs examined in this study formed exclusively 1:1 complexes with the glycans, except for SCR037•β-Glc, which formed the 1:2 SCR:glucoside complex, SCR037•β-Glc2. In SCR037•β-Glc2, a small positive allosteric cooperativity is demonstrated with K2 > K1 [38a, 38c], and these data are further verified with the molecular modeling results. In addition, several of the SCRs formed dimers (SCR030, SCR032, SCR034), with SCR034 having the highest Kd, and, as a result, the dimerization was considered in the fitting model. For all other complexes, satisfactory fits were obtained without having to include Kd. All binding data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Complexation (K1, K2), dimerization (Kd), and cumulative (β = K1 × K2) constants for SCR018, SCR019, SCR030 – SCR039 with five octyloxy pyranosides calculated from 1H NMR titrations in CD2Cl2 at 298 K.a,b

| β–Glc | α–Glc | β–Man | α–Man | β–Gal | Dilution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Receptor | K1 (M−1) | K2 (M−1) | β (M−2) | K1 (M−1) | K1 (M−1) | K2 (M−1) | β (M−2) | K1 (M−1) | K1 (M−1) | K1 (M−1) |

|

| ||||||||||

| SCR018 | -f | - | - | -d | -d | - | - | 1.1*104 | 6.6*101 | -d |

| SCR019 | -d | - | - | -d | 2.3*100 | 3.2*104 | 7.4*104 | -d | -d | -d |

| SCR030 | -e | - | - | -d | -d | - | - | 8.8*102 | -d | 8.4*101 |

| SCR031 | 5.0*102 | - | - | 1.1*103 | 3.0*102 | - | - | 8.7*102 | 3.4*102 | -d |

| SCR032 | -d | -d | -d | -d | 9.9*101 | - | - | 5.1*102 | -d | 1.5*102 |

| SCR033 | -d | - | - | 9.6*101 | 1.2*102 | - | - | 1.8*102 | -d | -c |

| SCR034 | -d | - | - | -d | -d | -d | -d | 8.8*101 | -d | 5.1*102 |

| SCR035 | 7.8*101 | - | - | 2.6*102 | 1.1*102 | - | - | 1.8*102 | 8.2*101 | -f |

| SCR036 | 1.2*102 | - | - | 2.1*101 | -d | - | - | 9.9*101 | -f | -f |

| SCR037 | 4.1*102 | 9.2*102 | 3.8*105 | 1.2*102 | 7.9*101 | - | - | 4.1*101 | 1.1*102 | -f |

| SCR038 | 2.0*101 | - | - | 1.7*102 | 8.0*101 | - | - | 1.7*102 | 8.6*101 | -f |

| SCR039 | 3.2*102 | - | - | 4.6*102 | 3.4*102 | - | - | 6.8*102 | 1.3*102 | -d |

|

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Titrations performed in triplicate for SCR019·β-Man to determine experimental error. The standard deviation of Ka was 3.2×102 m−1 (15 % error).

Ka values are based on 1:1 binding model that also consider Kd when appropriate.

binding = 0.

binding below threshold.

no NMR peak shift observed.

Titration data fit unsatisfactory, although evidence of binding exists.

These data show that both binding strength and the receptor selectivity for different glycans – defined here as the ratio of Ka values – are dependent sensitively on the receptor structures. Binding results reveal that SCR030 – SCR039 are promiscuous and form 1:1 complexes with most monosaccharides examined. SCR030 and SCR034 show measurable binding with only α-Man. Analysis of the binding data of these tetrapodal SCRs reveals that varying the point-of-attachment (POA) of the heterocycles has a substantial impact on their Kas and specificities, and this subtle change can be all the difference needed for SCRs to vary from no binding to promiscuous binding to completely selective binding. While 2-indole (SCR018) and 3-indole (SCR019) SCRs showed strong preferential binding to α-Man and β-Man, respectively, SCR030 − SCR033 are more promiscuous with weak overall binding. Alternatively, SCR034 dimerizes strongly and has weak association with α-Man. Likewise, SCR035 − SCR039 are only minimally selective with weak overall binding, with SCR037 showing some preference for β-Glc.

Computational modeling.

To understand why changing the heterocycles POA and its H-bonding properties influences the SCRs’ binding selectivities, we performed a systematic computational modeling of all 50 receptor-octyloxy glycan 1:1 complexes. Since the SCR•glycan complexes are thermodynamically stable, the lowest-energy conformers should constitute an accurate representation of the bound structures. One of the challenges in finding such conformers is the complex conformational space of flexible molecular complexes that has to be searched using sampling algorithms. Such methods, however, are rarely employed in the modeling of carbohydrate receptors, which hinders our understanding of interactions that drive the carbohydrate recognition [37]. To overcome this challenge and locate the lowest-energy conformers, we adopted a cascade-based approach that was described in our previous work [38a]. Briefly, candidate structures were generated using force-field-based replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations. A CHARMM-GUI interface [44] was used to assemble the CHARMM36 and CgenFF molecular parameters for the glycosides and receptors respectively, and, for each complex, 12 coupled trajectories, distributed between 300 K and 400 K, were simulated for 100 ns each using Gromacs-2018.1 [45] software. The 300 K trajectory was then clustered, using a cutoff of 0.15 nm, to identify the most abundant binding motifs. Next, the representative structures of the 20 most abundant clusters for each of the 50 SCR•glucoside complexes were refined using a density-functional approximation level of theory. First, they were reoptimized using PBE+vdWTS [46] functional in light basis set settings of the Numerical Atom-centered Orbitals (NAO) available in FHI-aims code [47a]. This level of theory has been shown to provide accurate energetics for H-bonded and dispersion-driven structures of carbohydrates and weakly bound biomolecular complexes [48]. The electronic energy of the resulting geometries was then improved using many-body dispersion-corrected hybrid exchange-correlation functional, PBE0+MBD [49] in intermediate basis set settings. This level of theory combined with the basis set sittings show negligible basis set superposition error (BSSE) [47] and provides accurate predictions for conformational energies of carbohydrates and weakly bound complexes [46,48–50]. Separately, we applied a correction for solvation energy, defined as at difference between the electronic energy of the solute in a continuous medium and in a gas phase, using PCM solvation model available in the Gaussian16 software suite [51]. The same procedure was applied to find energies of unbound receptors, whereas unbound glycans were optimized in the 4C1 ring puckering and extended linker conformation. The solvation-corrected binding energies, defined as the difference between the energy of the complex and the energies of its constituents, are shown in Table 2. We should note that while this strategy yields binding energies matching experimental binding enthalpies [38a], it does not account for the entropic effects included in the Kas, and, as such, the resulting agreement between the theoretical predictions and experimental data can be only qualitative. Finally, to further validate that the predicted complexes are specific for one glycoside, we mutated the orientation of one hydroxy group of the 10 most stable complexes to create an epimer with the same configuration of the glycosidic bond, i.e. α-Glc and α-Man, β-Glc and β-Man, and β-Glc and β-Gal pairs. These complexes were then recomputed using same level of theory and compared to the previously predicted lowest-energy structures. 1H-1H ROESY experiment were performed to determine host-guest structure and validate the molecular modeling. The spectrum was taken at 700 MHz with 1:1 mixture of SCR018 and α-Man. Cross-peaks between host and guest were observed, and they were consistent with the molecular modeling (see Supporting Information Figure S111).

Table 2.

Predicted binding energies (in kcal mol−1) between the SCRs and five octyloxy pyranosides. The binding energies are computed at PBE0+MBD level of theory and intermediate basis settings and were corrected for solvation energy using PCM solvation model.

| Receptor | β-Glc | α-Glc | β-Man | α-Man | β-Gal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| SCR030 | −23.1 | −28.9 | −26.0 | −28.7 | −27.3 |

| SCR031 | −27.0 | −24.5 | −259 | −293 | −258 |

| SCR032 | −27.4 | −26.0 | −29.2 | −29.4 | −26.2 |

| SCR033 | −22.8 | −24.3 | −22.1 | −23.8 | −22.5 |

| SCR034 | −26.0 | −20.7 | −24.1 | −24.4 | −26.2 |

| SCR035 | −27.4 | −20.8 | −25.2 | −24.5 | −26.4 |

| SCR036 | −26.1 | −22.0 | −28.5 | −22.8 | −23.8 |

| SCR037 | −24.0a | −24.7 | −25.4 | −23.9 | −22.9 |

| SCR038 | −26.8 | −25.0 | −27.3 | −26.5 | −28.4 |

| SCR039 | −21.9 | −23.1 | −20.2 | −24.8 | −24.5 |

SCR037 forms a 1:2 complex with β-Glc, with the second binding energy of −26.4 kcal mol−1, calculated in light basis set settings.

Binding between glycosides and indole-based SCR030 – SCR033.

Computational modeling predicted that SCR030, which has the linker POA at the 7-position, forms the most stable complexes with the two α-glycosides, α-Glc and α-Man, which have binding energies of −28.9 and −28.7 kcal mol−1, respectively (Figures 2a and 2b), 1.4 kcal mol−1 stronger than the next most strongly binding octyloxy glycan, β-Gal. Experimentally, only α-Man is observed to form stable complexes. Inspection of the structure of the SCR030•α-Man complex reveals the C−H1,3,5⋯π interaction between the pyranose and an indole are formed during the association. This structure is further stabilized by three H-bonds in which SCR acts as the H-bond donor, two of which are formed between the Nam−H linker groups and O2 and α-O1 of the mannoside, and one between the Nin−H indole and O6 in the methoxy group. The remaining two indoles form internal Nin−H⋯Nam H-bonds with adjacent linkers, resulting in a cage around α-Man that produce stabilizing dispersion interactions with the carbohydrate.

Figure 2.

Lowest energy structures of SCR:glycan complexes discussed in the text. The receptor is shown in gray, while sugar is shown in light blue (α-Glc), dark blue (β-Glc), or light green (α-Man). The H-bonds are shows with dashed lines, non-polar Hs are omitted for clarity.

After shifting the indole POA to the 6-position, resulting in SCR031, the binding becomes more promiscuous. On the molecular level, the Nin−H group points outwards, away from the central biaryl motif. The theory predicts that α-Man forms the most stable complex, experimentally determined to be only second to α-Glc, with binding energy of −29.3 kcal mol−1. The structure of the complex (Figure 2d) shows that the β-face of the pyranose associates with the indole ring. The pyranose is further stabilized by four H-bonds, three of which utilizes SCR as the H-bond donor: two Nin−H⋯O2 and Nin−H⋯O5 H-bonds are formed between the indoles and mannosyl hydroxy groups, and one H-bond is formed between the amine and the methoxy moiety, Nam−H⋯O6. The O6 atom also acts as a H-bond donor to an amine group on another receptor arm, which facilitates extra C−H1,3,5⋯π interactions between the indole and the glycoside α-face. SCR031•α-Glc, which has the largest Ka among all glycosides with SCR031, has a predicted binding energy of only −24.5 kcal mol−1, comparable for that predicted for SCR031•β-Man and SCR031•β-Gal complexes. Neither expanding the number of structures computed at DFT level conformers nor epimerization of the SCR031•α-Man complexes yielded a more stable minimum. Most probably, the initial force-field based search failed to generate a feasible candidate because of overestimation of the intramolecular dispersion interactions within the receptors (Figure 2c).

The other two receptors, SCR032 and SCR033, have the POAs at 8-position and 5-position, adjacent to the five-member ring of the indole. As a result, the Nin−H H-bond donors are pointing, respectively, inward or outward with respect to the central biaryl core. In the case of the inward-pointing SCR032, the theory predicts both mannosides to be the strongest binders, with the binding energies of −29.4 and −29.2 kcal mol−1 for α- and β-anomers, respectively, which agrees qualitatively with the experimentally observed Kas. Upon binding of SCR032 with β-Man, the glycan aligns itself perpendicularly to the plane of the biaryl core and forms C−H1,3,5⋯π interactions with one of the indole rings. Next, the pyranose ring is sandwiched by a second indole, which forms C−H4,6⋯π interactions with the opposite pyranose face, while the remaining two indole rings are involved in Nin−H⋯O2 and Nin−H⋯O6 H-bonds with the β-Man hydroxyl groups. The axial arrangement of the α-octyloxy linker in α-Man disrupts such interactions and associates through interactions between its β-face and the biaryl core. Three H-bonds, involving Nin−H and O6, O4 and O3 hydroxyl groups, stabilize this conformation, whereas the fourth arm of the receptor provides an additional H-bond between the amine group and O2, and C−H1,7⋯π interactions, which involve the anomeric H and the octyloxy linker. The three remaining glycosides are predicted to have at least a 2 kcal mol−1 weaker interaction with the SCR032 receptor, and, experimentally, they were not observed to form stable complexes.

In all SCR-glycoside complexes discussed to this point, the pyranose ring preferred to associate on the side of the heterocycle indole that faces towards the central biaryl core of the receptor because of additional H-bonds formed between glycoside hydroxyl groups and remaining heterocycles. Because of the outward orientation of the indoles’ N−H bonds in the SCR033 receptor, fewer interactions with the receptor are possible, which results in the glycoside associating on the external surface of the receptor. This accounts for the lowest experimentally-derived Kas amongst all indole-based receptors, with the largest Ka of only 1.8 × 102 M−1 measured for the SCR033•α-Man complex. As seen in the Figure 2e, α-Man, which forms C−H3,5⋯π interactions with only one indole heterocycle, is stabilized by only one Nin−H⋯O6 H-bond and a dispersive interaction between axial O2 and the octyloxy linker and the indole ring, resulting in a weak binding energy of −23.8 kcal mol−1. The other two glycosides, α-Glc and β-Man, which were determined to have weak Kas, form similar weakly-bound complexes with the receptor.

Binding between glycosides and quinoline-based SCR034−039.

Quinolines lack the H-bond donating N−H group of indoles, and, instead, they carry a basic N atom, which is an excellent H-bond acceptor. Therefore, we should expect that the glycosidic hydroxyl groups will act as H-bond donors more frequently than in indole-based receptors. The decreased quantity of N−H donors, however, may also have an impact on the receptor dimerization, as seen in the SCR034. In this case, the POA at the 2-position, adjacent to the N atoms, accounts for the significant dimerization strength of the receptor. As a consequence, only α-Man shows binding with the receptor, with a Ka of 8.8 × 101 M−1. Calculations do not predict this complex, with predicted binding energy of −24.4 kcal mol−1, to be more stable than the others, and, in fact, is slightly weaker than predicted for β-Glc, and this discrepancy could be accounted for by entropic effects. The SCR034•α-Man complex, however, is the only structure, where the receptor opens up to accommodate the mannoside in the center of the receptor, orienting the glycan over the biaryl core (Figure 2f), a position which features two O2−H⋯Nqui and O6−H⋯Nqui H-bonds. In contrast, the calculated complex with other glycosides involves only non-specific and weak contacts on the external surface of the receptor.

Shifting the POA to the 3-position in SCR035 results in a receptor that forms weak, promiscuous interactions with all 5 glycosides. Inspection of the structures of these complexes shows that the three β-glycosides, β-Glc, β-Man, and β-Gal, exhibit similar binding to this receptor (Figure 2g). Each pyranose associates by its β-face at the biaryl core, forming C−H1,3,5⋯π interactions and three H-bonds between the hydroxyl groups and the N in the quinoline rings. One of the H-bonds, which involves O6−H acting as an H-bond acceptor from the amine and H-bond donor to the quinoline, is common for all three β−glucosides. Other interactions can vary, depending on the stereochemistry of the hydroxyl groups, but result in comparable SCR binding energies of −27.4, −25.2 and −26.4 kcal mol−1 for β-Glc, β-Man, and β-Gal, respectively. This small variation agrees with the comparable association constants of 7.8 × 101 – 1.1 × 102 M−1. In the case of the two α-glycosides, the theory predicts weaker binding energies of −20.8 and −24.5 kcal mol−1 for α-Glc and α-Man, respectively. The α-orientation of the linker prohibits the favorable, parallel-type association at the biaryl core. Instead the sugars associate onto the receptors surface and forms multiple H-bonds, but they lack stabilizing impact of the C−H⋯π interactions.

Experimentally, shifting of the POA of the quinoline to the 4-position in SCR036 weakens the binding with respect to the SCR035. Theory predicts the strongest binding in the SCR036•β-Man complex (−28.5 kcal mol−1), followed by SCR036•β-Glc (−26.1 kcal mol−1). Despite the high predicted binding energy, the β-Man does not appear bind to SCR036 experimentally. The theory probably overestimates the strength of the interaction of the pyranose ring and two quinoline heterocycles, and completely neglects the entropic penalty associated with forming this sandwich structure. The molecular structure of the β-Glc complex, which has a Ka of 1.2 × 102 M−1, features the pyranose ring in a perpendicular orientation with respect to the biaryl core. This provides access to C−H1,3,5⋯π and C−H2,4,⋯π interactions between the nonpolar pyranose faces and two quinolines. In addition, the sugar is involved in two H-bonds, O2−H⋯Nqui and O6−H⋯Nam. The other two stable complexes, α-Glc and α-Man, also feature a similar perpendicular orientation of the pyranose, but the orientation of the octyloxy linker disrupts the C−H⋯π interactions, resulting in substantially weaker predicted binding energies of −22.0 and −22.8 kcal mol−1 than in their β-epimers.

Shifting the POA from the 6-position in the SCR037, which moves the linker to the benzene ring of the quinoline, results in another promiscuous receptor. The predicted binding energies are within 2.5 kcal mol−1 range, between −22.9 (β-Gal) and −25.4 (β-Man) kcal mol−1, despite very different structures of the computational complexes. For instance, β-Gal associates at the biaryl core, whereas β-Man and α-Man both associate at the quinoline heterocycle, but, respectively, on the side pointing in the biary-core direction and the outside of the receptor. The only notable exception is β-Glc, which experimentally forms a non-stoichiometric 1:2 SCR:glycan complex. In this case, the β-Glc associates between two adjacent receptor arms (Figure 2h), forming Nam−H⋯O3 and O2−H⋯Nam H-bonds, similar to those previously reported for complexes of SCR001 [38a]. This binding conformation provides a symmetric pocket on the opposite side of the biaryl core, which can readily accommodate a second β-Glc. The predicted binding energies of the first and second β-Glc, −24.0 kcal mol−1 and −26.4 kcal mol−1, respectively, quantitatively agree with experimental Kas (Figure 2g) of 4.1 × 102 and 9.2 × 102 M−1. Importantly, this 1:2 complex does not feature any pyranose-pyranose contacts, which is classified as non-cooperative binding, which explains the comparable magnitude of the first and the second Kas [37–38].

Predicted binding energies of SCR038, which carries the POA at the 7-position, again spans a narrow 3 kcal mol−1 range, which corroborates the experimentally-observed promiscuous binding. Specifically, α-Glc shows the weakest interaction of −25.0 kcal mol−1, and β-Gal has the strongest interaction of −28.4 kcal mol−1. Interestingly, the structures of these complexes employ a range of C−H1,3,5⋯π and H-bonding interactions that are unique to each system. In some cases, such as β-Man, the pyranose associates onto the quinoline ring and acts as H-bond donor with O2−H⋯Nam, and O6−H⋯Nqui interactions, and as an acceptor with Nam−H⋯O5 and Nam−H⋯O6 bonds (Figure 2h). In the other two complexes, SCR038•β-Gal and SCR038•β-Glc, the pyranose associates onto the biaryl core of the SCR, which twists along the phenyl-phenyl bond to optimize H-bonds between the hydroxyl groups and the heterocycles. In the case of the two α-glycosides, the pyranose avoids formation of any C−H⋯π interactions. Instead, the binding is driven solely by multiple H-bonds between the quinolines and amine groups with the pyranoside hydroxyl groups.

Finally, SCR039 is another promiscuous receptor that binds all sugars with Kas between 1.3 × 102 M−1 (β-Gal) to 6.8 × 102 M−1 (α-Man). The theory predicts that the complexes are weak binders, with the absolute binding energies smaller than 24.8 kcal mol−1. Participation of the quinoline N atoms in the intramolecular H-bond with the amine linker appears to preclude the formation of intermolecular H-bonds with the glycans, resulting in weaker and promiscuous association.

Discussion

Through four generations of iterative design, we have reported a series of tetrapodal SCRs which differ with respect to structural parameters, such as the regiochemistry of the heterocycle attachment (POA), H-bonding abilities (whether the heterocycle is a H-bond donor or acceptor), size, and the polarizability of the π-conjugated system, as well as the composition of the linker between the heterocycle and the biaryl core. Systematic variations in this parameter space results in receptors which binding to octyloxy pyranosides in CD2Cl2 ranges from weak, to promiscuous, to selective, to specific glycan binders (Figure 3). From this collection of data, we can extract rules that can anticipate the binding of as-yet synthesized SCRs.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Log β values of SCR with different glycans determined from 1H NMR titrations in CD2Cl2. Star on the bars indicates cumulative association constant (β = K1 x K2). G1 indicates the first generation of tetrapodal SCRs [38c].G2 indicates the second generation of tetrapodal SCRs [38b]. G3 indicates the third generation of tetrapodal SCRs [38a]. G4 indicates the fourth generation of tetrapodal SCRs (reported here).

Interestingly, the six largest association constants were measured when non-stoichiometric (1:2 or 2:1 SCR:glycan ratio) complexes form. The ratio of the first and the second association constants determines the type of non-stoichiometric association. If K1 is larger than or approximately equal to K2, then the receptor:glycan complex features a non-cooperative binding with little-to-none interactions between the two glycans. Such binding is observed when two symmetric binding pockets on the opposite sides of the receptor are formed, as seen in SCR001•(β-Man)2 [38a, 38c] and SCR037•(β-Glc)2. If K1 is smaller than K2, but within a range of 1−2 orders of magnitude, then the complex is weakly cooperative as a result of some interactions between the glycans. SCR020•(α-Man)2 constitutes example of such complex and structural analysis revealed formation of one H-bonds between the two glycans[38a]. Finally, if K2 is several orders of magnitude larger than K1, then the complex is strongly cooperative, as seen in SCR019•(β-Man)2 and SCR021•(β-Glc)2 [38a], and Computational modeling revealed that the binding of the second glycan results in several H-bond interactions with the first glycan. Since the largest binding constant for the stoichiometric complexes, observed for SCR018•α-Man, is an order of magnitude smaller than for the non-stoichiometric ones, the multivalent binding might be the key to further improve the SCRs selectivity.

Indole heterocycles have 6 possible points of attachment, two at the five-member ring and four at the six-member ring. A POA at the five-member ring (2- and 3-positions) results in two selective SCRs. SCR018 (2-position) forms a strong complex with α-Man and a weak complex with β-Gal. Shifting the linker to the 3-position, as in SCR019, leads to formation of selective and non-stroichimetric 1:2 SCR:glycan complex with the epimer, β-Man, which has the opposite configuration at the anomeric carbon. Interestingly, shifting the POA to the six-member ring drastically alters the selectivity of the SCRs in a few different ways. First, the value of the largest association constant measured for these POAs is smaller than 103 M−1. While SCR030 remains selective towards α-Man, the association constant for this complex is smaller than for the SCR018•α-Man. Next, SCR031, is a promiscuous receptor, which forms interactions of comparable strength with all five glycosides. Both SCR032 and SCR033, which have a POA at the carbons adjacent to the five-member ring, show only moderate selectivity towards mannosides. Taken together, none of the receptors which has the POA at the six-member ring forms non-stoichiometric complexes with any of the glycans. Second, by comparing the pairs of SCR001 and SCR018, and SCR017 and SCR019, which have the same relative position of the N−H and the POA in the pyrrole and indole heterocycles, we can evaluate the impact of increasing the π-conjugated system. As we reported previously [38a, 38b], SCR001 can form three types of complexes: parallel, perpendicular, and off-center, which depends on the relative orientations of the biaryl core and the pyranose ring. Changing the pyrrole heterocycle to the more bulky indole in SCR018 limits the access to the biaryl core in parallel and off-center orientations, which hinders formation of non-stoichiometric complexes. This size-exclusion effect, however, is weaker in fused heterocycles that have the POA at the same ring as the H-bonding group. In this case, as seen for instance in SCR017 and SCR019, both receptors are able to form selectively 1:2 SCR:glycan complexes.

Quinoline shows weaker dependence on the POA of the linker than indole. Only SCR034 is selective towards α-Man. Remaining receptors, with the exception of SCR037•β-Glc, are promiscuous and the largest Ka was < 103 M−1. Pyridine-based receptors SCR020 and SCR021 are selective as a result of cooperative binding in non-stoichiometric complexes. SCR034, which has the same POA as SCR020, also shows selectivity towards α-Man, but is unable to form non-stoichiometric complex because of size-exclusion, and SCR035, which has the same POA as SCR021, is a promiscuous binder. It is likely that the quinoline heterocycles forms stronger intramolecular van der Waals interactions than pyridine, which makes opening of the receptor to accommodate the pyranose energetically unfavorable. Instead, the glycosides would form several non-specific C−H⋯π and H-bonding interactions with the closed receptor, which, despite having very different molecular structures, show very similar binding energies and promiscuous association.

Finally, both the linker composition and the H-bonding properties of the heterocycle appear to be inconsequential for the receptors selectivity. Comparison of SCR001 (amine linker) and SCR005 (imine linker), shows that the latter yields somewhat larger Kas. This enhancement could be explained by the imine being a better H-bond acceptor than the amine [52]. The stronger binding, however, applies towards all carbohydrates and does not result in increased selectivity of the receptor. On the contrary, the amine group, which can act both as an H-bond donor and acceptor, is required to form non-stoichiometric complexes. Similarly, H-bonding properties of the heterocycle do not relate directly to the receptors’ selectivity or the association strength. Heterocycles that are H-bond donors (e.g. pyrrole in SCR017) and H-bond acceptors (e.g. pyridine in SCR020) can form strong, selective complexes, as well as weak and promiscuous ones, as seen in indoles and quinolines − especially when POA is distant from the H-bonding group.

Conclusions

Here we have prepared a series of new flexible, tetrapodal SCRs with indole and quinoline heterocycles that vary in their POA to the biaryl core. Their binding to a series of biologically-relevant octyloxy glycans was studied experimentally and computationally to provide Kas and lowest-energy binding conformations. Based on an analysis of these new binding data along with the binding data of the previous three generations of this class of SCRs, we are able to identify relationships between tetrapodal SCR structure and trends in the binding data. A first observation is that the largest Logβ values arise from non-stoichiometric binding – where the SCR can associate with more than one equivalent of a glycan. This non-stoichiometric association also accounts for the selectivity of a number of SCRs. Take, for example the binding data of SCR037. This receptor is promiscuous and binds most glycans weakly, however it is selective towards β-Glc because if forms a 1:2 SCR:glycan complex only with β-Glc. As such, we conclude that the receptors will be selective towards glycans with which they can form complexes with 1:2 stoichiometries. Cooperative interactions reinforce this observation. When the association is non-cooperative (K1 ≈ K2), as seen in SCR037•(β-Glc)2,, the receptor binds other glycans weakly. However, when the SCR:glycan complex is strongly cooperative (K1 << K2), as seen in SCR019, SCR021, then the receptor binds exclusively one glycan. A second observation is that small heterocycles (e.g. pyrrole, furan, thiophene, phenol) do not suffer from the size exclusion effect that sterically hinders the non-stoichiometric association. With fused heterocycles (e.g. indoles, quinolines), the POA has a significant impact on binding trends. We find that when the POA is on the same ring as an H-bonding group, then selective binding is more frequent than when placing the POA at the other rin,g which leads to promiscuous binders. Increasing the separation between the H-bonding group in the linker and the heterocycle results in more possibilities for non-specific association, which decreases the selectivity. Another observation is that some SCRS are capable of forming intramolecular H-bonds, and doing so weakens the binding affinity because the glycan must overcome this intramolecular stabilization to form a host-guest complex. This phenomena can result in high selectivity, however, as is the case of SCR022, only β-Glc is capable of overcoming this intramolecular stabilization. Finally, we observe that electron-rich heterocycles, such as those found in SCR019, SCR030, and SCR039, draw the glycan away from the biaryl core, and, in some cases, such as SCR033•α-Man, the lowest-energy binding conformation involves a glycan that rests on the outside face (pointing away from the biaryl core) of the heterocycle. Although there are many open questions that remain about SCR design, these rules provide the first rational foundation for explaining the binding of previously synthesized flexible, tetrapodal SCRs, and allow us to anticipate the binding of SCRs that have not yet been prepared. These results are an important step towards the rational design of selective SCRs with tunable binding affinities, which have important implications for both catalysis and medicine.

Experimental Section

General synthesis of SCRs:

SCRs were synthesized following the procedure bellow unless otherwise noted. PPh3 (5 mmol, 5 eq) was added to a stirring solution of 1 (1 mmol, 1 eq) in THF (5 mL) at room temperature. The reaction was refluxed under Ar atmosphere for 1 h before the addition of the heteroarylaldehyde (5 mmol, 5 eq) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was refluxed for additional 48 h, cooled to room temperature, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in MeOH (5 mL), and NaBH4 (10 mmol, 10 eq) was added in portions at room temperature under an Ar atmosphere followed by stirring for 16 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, treated with CHCl3 (30 mL) and H2O (30 mL), and the organic layer was separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 30 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the crude product, which was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CHCl3: MeOH: NH3 9:1:1) to give the pure products, SCR030-SCR039.

NMR Titration and fitting:

1H NMR titrations were performed in CD2Cl2, at a field strength of either 700 or 800 MHz at 298 K. Pyranoside 1H NMR resonances were previously reported[38b]. The addition of SCR to a pyranoside CD2Cl2 solution or vice versa resulted in the perturbation of the chemical shifts (δ) corresponding to resonances of both SCR and pyranoside. This is the result of an exchange process involving SCR (H) and pyranoside (G) equilibria products interchanging fast on the NMR timescale, resulting in the averaging of chemical shits of protons in differing chemical environments. Accordingly, equilibrium constants (K) can be quantified by first defining a model that includes the correct set of equilibria, calculating the hypothetical concentrations of equilibrium species and the corresponding chemical shifts, and finally fitting the resulting data to the experimental results.

Computational Modeling

The search protocol for finding the minimum-energy binding structures involved the following steps: The initial sampling of the conformational space has been performed using a replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) protocol implemented in Gromacs-2018.2 [45]. First, the parameters for 10 SCRs and 5 sugars were derived from a CHARMM36 force field using the charmm-gui web-interface [44] and combined into 50 SCR•glycan complexes. Initial hand-generated conformations were first equilibrated in the gas phase for 1 ns at 300 K, controlled by a v-rescaling thermostat, and the final structure was used as a starting geometry for REMD simulations. Each complex involved 12 replicas distributed in 300–400 K temperatures according to the Monte-Carlo criteria. The temperatures were chosen to yield an exchange rate of 0.65. The trajectories were simulated for a 100 ns each, with a 1 fs time step and an attempted exchange between trajectories neighboring in temperature space every 10 ps. Each 300 K trajectory was subsampled every 50 ps to generate a set of initial set of 2000 structures visited during the simulations. The structures were then clustered using a single linkage algorithm with a 1.5 Å cutoff for root means square (RMS) distance between all atoms. In several cases in which the supramolecular complex dissociated at 300 K, we restarted the REMD from a different equilibrated structure. For each system we collected central structures of the 20 most abundant clusters, which were used as starting geometries for subsequent density-functional theory calculations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A.B.B. and M.M. thank the Army Research Office (W911NF2010271) for financial support. M.M. thanks the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (SC2GM135145) and the COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium (MCB200141)for financial support. The NMR data (Bruker Avance 300, 700, and 800 MHz) presented herein were collected in part at the CUNY ASRC Biomolecular NMR facility and the NMR facility of the City College of the CUNY. Mass spectra were collected at the CUNY ASRC Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry Facility. We thank Dr. James Aramini (Biomolecular NMR Facility at ASRC), Dr. Rinat Abzalimov (Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry Facility at ASRC) for their help in acquiring the spectral data.

References

- [1].a) Barre A, Bourne Y, Van Damme EJ, Peumans WJ, Rouge P, Biochimie 2001, 83, 645–651; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinaý P, Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2000, 1105p; [Google Scholar]; c) Gabius HJ, The Sugar Code: Fundamentals of Glycosciences, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009, pp. 3–12; [Google Scholar]; d) Garg HG, Cowman MK, Hales CA, Carbohydrate Chemistry, Biology and Medical Applications, Elsevier, Oxford, 2008, pp. 1–21; [Google Scholar]; e) Hao Q, Van Damme EJ, Hause B, Barre A, Chen Y, Rouge P, Peumans WJ, Plant. Physiol. 2001, 125, 866–876; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kilpatrick DC, Handbook of Animal Lectins: Properties and Biomedical Aplications, Wiley, Weinheim, 2000; [Google Scholar]; g) Lindhorst TK, Essenstials of Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2007; [Google Scholar]; h) Loris R, De Greve H, Dao-Thi MH, Messens J, Imberty A, Wyns L, J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 301, 987–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Liu DR, Guan QL, Gao MT, Jiang L, Kang HX, Int. J. Biol. Markers 2017, 32, e278–e283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Takayama H, Ohta M, Iwashita Y, Uchida H, Shitomi Y, Yada K, Inomata M, BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Legler K, Rosprim R, Karius T, Eylmann K, Rossberg M, Wirtz RM, Muller V, Witzel I, Schmalfeldt B, Milde-Langosch K, Oliveira-Ferrer L, Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tao SC, Li Y, Zhou J, Qian J, Schnaar RL, Zhang Y, Goldstein IJ, Zhu H, Schneck JP, Glycobiology 2008, 18, 761–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Han X, Zheng Y, Munro CJ, Ji Y, Braunschweig AB, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 34, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burrell CJ, Howard CR, Murphy FA, Fenner and White’s Medical Virology, Elsevier, Oxford, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Kim SY, Zhao J, Liu X, Fraser K, Lin L, Zhang X, Zhang F, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ, Biochem. 2017, 56, 1151–1162; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen Y, Maguire T, Hileman RE, Fromm JR, Esko JD, Linhardt RJ, Marks RM, Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 866–871; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Routhu NK, Lehoux SD, Rouse EA, Bidokhti MRM, Giron LB, Anzurez A, Reid SP, Abdel-Mohsen M, Cummings RD, Byrareddy SN, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mahase E, BMJ 2020, 368, m1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ritchie G, Harvey DJ, Stroeher U, Feldmann F, Feldmann H, Wahl-Jensen V, Royle L, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, RCM 2010, 24, 571–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gulland A, BMJ 2016, 352, i657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Fraser IP, Koziel H, Ezekowitz RA, Semin. Immunol. 1998, 10, 363–372; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Holmskov UL, APMIS Suppl. 2000, 100, 1–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tommasone S, Allabush F, Tagger YK, Norman J, Köpf M, Tucker JHR, Mendes PM, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 5488–5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Cheung NK, Kushner BH, Yeh SD, Larson SM, Int. J. Oncol. 1998, 12, 1299–1306; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, London WB, Kreissman SG, Chen HX, Smith M, Anderson B, Villablanca JG, Matthay KK, Shimada H, Grupp SA, Seeger R, Reynolds CP, Buxton A, Reisfeld RA, Gillies SD, Cohn SL, Maris JM, Sondel PM, Children’s Oncology G, N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1324–1334; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cheung NK, Cheung IY, Kramer K, Modak S, Kuk D, Pandit-Taskar N, Chamberlain E, Ostrovnaya I, Kushner BH, Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 2199–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sun W, Du L, Li M, Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 2269–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Rauschenberg M, Bandaru S, Waller MP, Ravoo BJ, Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 2770–2782; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Melicher MS, Walker AS, Shen J, Miller SJ, Schepartz A, Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4718–4721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tommasone S, Allabush F, Tagger YK, Norman J, Kopf M, Tucker JHR, Mendes PM, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lazo JS, Sharlow ER, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 56, 23–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ, Biochem. J. 2004, 382, 769–781; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tomme P, Van Tilbeurgh H, Pettersson G, Van Damme J, Vandekerckhove J, Knowles J, Teeri T, Claeyssens M, Eur. J. Biochem. 1988, 170, 575–581; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bolam DN, Ciruela A, McQueen-Mason S, Simpson P, Williamson MP, Rixon JE, Boraston A, Hazlewood GP, Gilbert HJ, Biochem. J. 1998, 331, 775–781; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Boraston AB, Kwan E, Chiu P, Warren RA, Kilburn DG, J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 6120–6127; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Charnock SJ, Bolam DN, Turkenburg JP, Gilbert HJ, Ferreira LM, Davies GJ, Fontes CM, Biochem. 2000, 39, 5013–5021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Ali MK, Hayashi H, Karita S, Goto M, Kimura T, Sakka K, Ohmiya K, Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 41–47; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zverlov VV, Volkov IY, Velikodvorskaya GA, Schwarz WH, Microbiology 2001, 147, 621–629; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Gilkes NR, Warren RA, Miller RC Jr., Kilburn DG, J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 10401–10407; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Maglione G, Matsushita O, Russell JB, Wilson DB, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 3593–3597; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Hall J, Black GW, Ferreira LM, Millward-Sadler SJ, Ali BR, Hazlewood GP, Gilbert HJ, Biochem. J. 1995, 309, 749–756; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Tromans RA, Carter TS, Chabanne L, Crump MP, Li H, Matlock JV, Orchard MG, Davis AP, Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Nakagawa Y, Doi T, Taketani T, Takegoshi K, Igarashi Y, Ito Y, Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 10516–10525; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dove A, Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 913–917; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Meledeo MA, Paruchuri VDP, Du J. Wang Z, Yarema KJ, Mammalian Glycan Biosynthesis: Building a Template for Biological Recognition, (Eds.: Wang B, Wang B, Boons G-J), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Shinkai S, Boronic Acids in Saccharide Recognition, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2006; [Google Scholar]; b) James TD, Shinkai S, Host-Guest Chemistry: Mimetic Approaches to Study Carbohydrate Recognition (Ed.: Penadés S), Springer, Heidelberg, 2002; [Google Scholar]; c) Davis AP, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2531–2545; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mazik M, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 935–956; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Davis AP, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3629–3638; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Gentili M, Nativi C, Francesconi O, Roelens S, Carbohydrate Chemistry, Vol. 41 (Eds.: Rauter AP, Lindhorst TK, Queneau Y), 2016, pp. 149–186; [Google Scholar]; g) Davis AP, Nature 2010, 464, 169–170; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Davis AP, Molecules 2007, 12, 2106–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Mazik M, Chembiochem. 2008, 9, 1015–1017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kubik S, Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1722–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cash KJ, Clark HA, Trends. Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Wu X, Li Z, Chen XX, Fossey JS, James TD, Jiang YB, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8032–8048; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hall DG, Boronic Acids: Preparation, Applications in Organic Synthesis and Medicine, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Jin S, Cheng Y, Reid S, Li M, Wang B, Med. Res. Rev. 2010, 30, 171–257; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) James TD, Stoddart JF, Phillips MD, Shinkai S, Boronic Acids in Saccharide Recognition, RSC 2006; [Google Scholar]; c) Sun X, James TD, Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8001–8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].James TD, Samankumara Sandanayake KRA, Shinkai S, Nature 1995, 374, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Eliseev AV, Schneider H-J, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 6081–6088; [Google Scholar]; b) Aoyama Y, Nagai Y, Otsuki J. i., Kobayashi K, Toi H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1992, 31, 745–747; [Google Scholar]; c) de Namor AFD, Blackett PM, Cabaleiro MC, Al Rawi JMA, J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1994, 90, 845–847; [Google Scholar]; d) Szejtli J, Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1743–1754; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Villalonga R, Cao R, Fragoso A, Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3088–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Rusin O, Král V. r., Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 4235–4238; [Google Scholar]; b) Kobayashi K, Asakawa Y, Kato Y, Aoyama Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10307–10313; [Google Scholar]; c) Poh B-L, Tan CM, Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 49, 9581–9592; [Google Scholar]; d) Yanagihara R, Aoyama Y, Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 9725–9728; [Google Scholar]; e) Goto H, Furusho Y, Yashima E, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9168–9174; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Nishio M, Umezawa Y, Hirota M, Takeuchi Y, Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 8665–8701. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Králová J, Koivukorpi J, Kejík Z, Poučková P, Sievänen E, Kolehmainen E, Král V, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1548–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bonar-Law RP, Davis AP, Murray BA, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1990, 29, 1407–1408. [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Vacca A, Nativi C, Cacciarini M, Pergoli R, Roelens S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16456–16465; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cacciarini M, Cordiano E, Nativi C, Roelens S, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 3933–3936; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Arda A, Canada FJ, Nativi C, Francesconi O, Gabrielli G, Ienco A, Jimenez-Barbero J, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 4821–4829; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Cacciarini M, Nativi C, Norcini M, Staderini S, Francesconi O, Roelens S, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 1085–1091; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Nativi C, Francesconi O, Gabrielli G, Vacca A, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 4814–4820; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Francesconi O, Nativi C, Gabrielli G, Gentili M, Palchetti M, Bonora B, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 11742–11752; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Francesconi O, Gentili M, Nativi C, Arda A, Canada FJ, Jimenez-Barbero J, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6081–6091; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Nativi C, Francesconi O, Gabrielli G, De Simone I, Turchetti B, Mello T, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Ghelardini C, Buzzini P, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 5064–5072; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Francesconi O, Nativi C, Gabrielli G, De Simone I, Noppen S, Balzarini J, Liekens S, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 10089–10093; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Francesconi O, Ienco A, Moneti G, Nativi C, Roelens S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6693–6696; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Nativi C, Cacciarini M, Francesconi O, Moneti G, Roelens S, Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 4685–4688; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Nativi C, Cacciarini M, Francesconi O, Vacca A, Moneti G, Ienco A, Roelens S, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4377–4385; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Arda A, Venturi C, Nativi C, Francesconi O, Gabrielli G, Canada FJ, Jimenez-Barbero J, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 414–418; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Francesconi O, Gentili M, Roelens S, J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 7548–7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].a) Davis AP, Wareham RS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2978–2996; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Klein E, Crump MP, Davis AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 44, 298–302; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ferrand Y, Crump MP, Davis AP, Science 2007, 318, 619–622; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Walker DB, Joshi G, Davis AP, Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2009, 66, 3177–3191; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Barwell NP, Davis AP, J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6548–6557; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Ke C, Destecroix H, Crump MP, Davis AP, Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 718–723; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Carter TS, Mooibroek TJ, Stewart PF, Crump MP, Galan MC, Davis AP, Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9311–9315; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Tromans RA, Samanta SK, Chapman AM, Davis AP, Chem. 2020, 11, 3223–3227; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Bhattarai KM, Davis AP, Perry JJ, Walter CJ, Menzer S, Williams DJ, J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 8463–8473; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) A. P. Davis, R. S. Wareham, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2270–2273; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Ryan TJ, Lecollinet G, Velasco T, Davis AP, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 4863–4866; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Velasco T, Lecollinet G, Ryan T, Davis AP, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 645–647; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Davis AP, James TD, Carbohydrate Receptors, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005; [Google Scholar]; n) Klein E, Ferrand Y, Auty EK, Davis AP, Chem. Comm. 2007, 2390–2392; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Barwell NP, Crump MP, Davis AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7673–7676; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p) Ferrand Y, Klein E, Barwell NP, Crump MP, Jimenez-Barbero J, Vicent C, Boons GJ, Ingale S, Davis AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1775–1779; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q) Sookcharoenpinyo B, Klein E, Ferrand Y, Walker DB, Brotherhood PR, Ke C, Crump MP, Davis AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4586–4590; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; r) Howgego JD, Butts CP, Crump MP, Davis AP, Chem. Comm 2013, 49, 3110–3112; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; s) Destecroix H, Renney CM, Mooibroek TJ, Carter TS, Stewart PF, Crump MP, Davis AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2057–2061; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; t) Mooibroek TJ, Casas-Solvas JM, Harniman RL, Renney CM, Carter TS, Crump MP, Davis AP, Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].a) Mazik M, Radunz W, Boese R, J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 7448–7462; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mazik M, Cavga H, Jones PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9045–9052; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mazik M, Cavga H, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 831–838; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mazik M, Hartmann A, J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7444–7450; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mazik M, Sonnenberg C, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 6416–6423; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Geffert C, Kuschel M, Mazik M, J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 292–300; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Lippe J, Mazik M, J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9013–9020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Rosien JR, Seichter W, Mazik M, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6569–6579; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Lippe J, Mazik M, J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1427–1439; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Mazik M, Hartmann A, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].a) Arda CVA, Nativi C, Francesconi O, Cañada FJ, Jimenez-Barbero J, Roelens S, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 64–71; [Google Scholar]; b) Francesconi O, Martinucci M, Badii L, Nativi C, Roelens S, Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6828–6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].a) Cram DJ, Cram JM, Acc. Chem. Res. 1978, 11, 8–14; [Google Scholar]; b) Cram DJ, Lein GM, Kaneda T, Helgeson RC, Knobler CB, Maverick E, Trueblood KN, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 6228–6232; [Google Scholar]; c) Artz SP, Cram DJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 2160–2171; [Google Scholar]; d) Cram JMCDJ, Container Molecules and Their Guests, RSC, Cambridge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [36].a) Weis WI, Drickamer K, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 441–473; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Koshland DE, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1958, 44, 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bravo MF, Lema MA, Marianski M, Braunschweig AB, Biochem. 2020, 60, 999–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].a) Bravo MF, Palanichamy K, Shlain MA, Schiro F, Naeem Y, Marianski M, Braunschweig AB, Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 11782–11795; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Palanichamy K, Bravo MF, Shlain MA, Schiro F, Naeem Y, Marianski M, Braunschweig AB, Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 13971–13982; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Rieth S, Miner MR, Chang CM, Hurlocker B, Braunschweig AB, Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Palanichamy K, Joshi A, Mehmetoglu-Gurbuz T, Bravo MF, Shlain MA, Schiro F, Naeem Y, Garg H, Braunschweig AB, J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 4110–4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dorababu A, RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 1335–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kumar S, Ritika, Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 121. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ackermann T, Berichte der Bunsengesellschaft für physikalische Chemie 1987, 91, 1398–1398. [Google Scholar]

- [43].a) Mazik M, RSC Advances 2012, 2, 2630–2642; [Google Scholar]; b) Koch N, Rosien J-R, Mazik M, Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 8758; [Google Scholar]; c) Mazik M, Geffert C, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 2319–2326; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mazik M, Hartmann A, Jones PG, Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9147–9159; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mazik M, Kuschel M, Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 2405–2419; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Mazik M, Buthe AC, J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 8319–8326; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Mazik M, Kuschel M, Sicking W, Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 855–858; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Mazik M, Cavga H, J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 2957–2963; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Mazik M, Sicking W, Tetrahedron 2004, 45, 3117–3121; [Google Scholar]; j) Mazik M, Radunz W, Sicking W, Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4579–4582; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Mazik M, Sicking W, Chem. Eur. J. 2001, 7, 664–670; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Mazik M, Bandmann H, Sicking W, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 551–554; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Mazik M, Konig A, J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7854–7857; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Mazik M, Buthe AC, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1558–1568; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Mazik M, Buthe AC, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 2063–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].a) Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W, J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee J, Cheng X, Swails JM, Yeom MS, Eastman PK, Lemkul JA, Wei S, Buckner J, Jeong JC, Qi Y, Jo S, Pande VS, Case DA, Brooks III CL, MacKerell AD Jr., Klauda JB, Im W, Chem J. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mark James Abraham TM, Schulz Roland, Páll Szilárd, Smith Jeremy C, Hess Berk, Lindahl Erik, SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- [46].a) Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M, Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marom N, Tkatchenko A, Scheffler M, Kronik L, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].a) Blum V, Gehrke R, Henke F, Havu P, Havu V, Ren X, Reuter K, Scheffler M., Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009, 180, 2175–2196; [Google Scholar]; b) Ihring AC, Wieferink J, Zhang IY, Ropo M, Ren X, Rinke P, Scheffler M, Blum V, New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 093020. [Google Scholar]

- [48].a) Tkatchenko A, Rossi M, Blum V, Ireta J, Scheffler M, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 118102; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marom N, Tkatchenko A, Rossi M, Gobre VV, Hod O, Scheffler M, Kronik L, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 3944–3951; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Marianski M, Supady A, Ingram T, Schneider M, Baldauf C, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 6157–6168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].a) Tkatchenko A, DiStasio RA, Car R, Scheffler M, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 236402; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Perdew JP, Ernzerhof M, Burke K, J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 9982–9985. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hermann J, DiStasio RA Jr., Tkatchenko A, Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 4714–4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gaussian 16, Revision A.02, Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Li X, Caricato M, Marenich AV, Bloino J, Janesko BG, Gomperts R, Mennucci B, Hratchian HP, Ortiz JV, Izmaylov AF, Sonnenberg JL, Williams, Ding F, Lipparini F, Egidi F, Goings J, Peng B, Petrone A, Henderson T, Ranasinghe D, Zakrzewski VG, Gao J, Rega N, Zheng G, Liang W, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Throssell K, Montgomery JA Jr., Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd JJ, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith TA, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Millam JM, Klene M, Adamo C, Cammi R, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Fox DJ, Gaussian, Inc.,Wallingford, CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Arey JS, Aeberhard PC, Lin IC, Rothlisberger U, J. Phys.Chem. B 2009, 113, 4726–4732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.