Abstract

Patient: Female, 3-week-old

Final Diagnosis: Thyroglossal duct cyst

Symptoms: Infection • neck mass • respiratory distress

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Incision and drainage • Sistrunk’s procedure

Specialty: Otolaryngology • Pediatrics and Neonatology

Objective:

Congenital defects/diseases

Background:

Thyroglossal duct cysts are the most common congenital cervical anomalies, often presenting as midline neck cysts. The mean age of presentation of pediatric thyroglossal duct cysts varies between 5 and 9 years old, with rare cases younger than 1 year old. This case report details a rare case of an infected thyroglossal duct cyst presenting during the neonatal period as an upper airway obstruction.

Case Report:

A 3-week-old neonate born full-term with no complications during pregnancy or labor presented with a 5-day history of worsening nasal congestion and upper airway obstruction after an upper respiratory infection. Physical examination revealed a large midline neck mass measuring 3.1×4.2×3.2 cm abutting the hyoid with internal echogenicity consistent with a thyroglossal duct cyst, causing posterior tongue compression of the airway and airway distress. The patient was emergently taken to the operating room for incision and drainage, where she underwent a difficult intubation due to superior-posterior tongue displacement and global supraglottic edema. She was discharged on postoperative day 5 on a course of Augmentin after cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. The patient had no further complications, with successful excision using a Sistrunk procedure 6 months later.

Conclusions:

Pediatric thyroglossal duct cysts most often present as an asymptomatic midline neck mass, with rare sequel-ae of infection and upper airway obstruction. This case report highlights the pathophysiology and presenting symptomology of thyroglossal duct cysts, explores the rarity of infected thyroglossal duct cysts in neonates, and reviews the current literature on management strategies for these patients.

Keywords: Congenital Abnormalities, Neck, Pediatrics, Thyroglossal Tract Cyst, Otolaryngology

Background

Thyroglossal duct cysts (TGDC) are the most common congenital cervical anomaly and the most common pediatric mass, with a prevalence of 7% in the worldwide population. TGDCs are remnants that form from failure of closure of the thyroglossal duct, extending from the foramen cecum in the tongue to the thyroid’s location in the neck. The duct usually invo-lutes by the tenth week of gestation, but if it persists, secretion from the epithelial lining causes inflammation and cyst formation [1]. As there are many mimics of the TGDC, the clinician must be knowledgeable about the age of presentation, location of the lesion, association with surrounding structures, and internal architecture to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. Differentiating features of a TGDC include a close association with the posterior aspect of the hyoid located midline in the suprahyoid neck or paramidline in the infrahyoid neck [2]. The most common presenting symptom is an asymptomatic mid-line neck mass, but other symptoms include a sore throat, pain, dysphagia, and hoarseness [3]. Complications of a TGDC include infection from oropharyngeal organisms, with the most common being Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. These infections are treated with antibiotics prior to surgery; however, if an abscess is formed, aspiration or drainage is indicated [4]. Rare but serious complications include airway obstruction from a rapidly enlarging cyst, but these are most commonly lingual TGDC [5]. The age of presentation of TGDC and prevalence of infection is highly variable. Few reports have characterized the presentation of a TGDC in a patient less than 1 year old and even fewer have diagnosed an infected cyst in a patient this age [6,7]. We report a case of an infected TGDC in a 3-week-old neonate, while exploring the rarity of this presentation and reviewing management strategies of these patients. This is significant because currently there is no reported case of this pathology presenting in a patient this young. This has implications that may lead to reconsideration of when to suspect the diagnosis and how to manage complications for clinicians.

Case Report

A 3-week-old neonate born full-term with no complications during pregnancy or labor presented to the Emergency Department in respiratory distress with a 5-day history of worsening nasal congestion and upper airway obstruction after upper respiratory infection. She was diagnosed with a viral infection and given baby saline nebulizers by the pediatrician. The patient’s breathing and feeding worsened, leading to her presentation to the Emergency Department overnight. Her mother denied any family illness exposure. On admission, her heart rate was 164 bpm, her temperature was 38.2°C, her respiratory rate was 45, her oxygen saturation on room air was 98%, and her weight was 4.02 kg. Laboratory test results showed an elevated WBC count at 31.0×109/L with 6.20×109/L neutrophils and 20.0×109/L monocytes. A physical exam was significant for a visible large midline neck mass with pink overlying skin, as shown in Figure 1. The mass was firm and well-circumscribed on palpation.

Figure 1.

Clinical image of neck mass.

A chest X-ray showed minimally prominent central peribronchial markings with no consolidation or effusion. A viral panel was negative. An ultrasound revealed a large midline neck mass measuring 3.1×4.2×3.2 cm abutting the hyoid, with internal echogenicity consistent with a thyroglossal duct cyst, causing posterior tongue compression of the airway. Midline neck longitudinal and transverse ultrasound views are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Midline ultrasound neck longitudinal view of neck mass (between arrows).

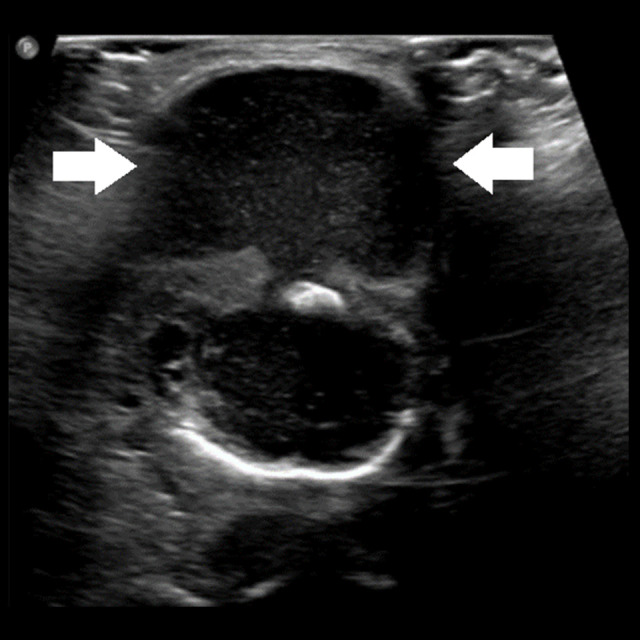

Figure 3.

Midline ultrasound neck transverse view of neck mass (between arrows).

She was noted to obstruct regardless of position. The patient was emergently taken to the operating room by the otolaryngologist for incision and drainage of the cyst, where 10 mL of fluid was aspirated to decrease neck swelling. When the patient’s respiratory distress did not improve, the decision was made to intubate. Exposure of the larynx with a Parsons 1 laryngoscope was difficult due to superior-posterior tongue displacement and global supraglottic edema. Telescopic endoscopic intubation was attempted with a 3.5 tube seldingered over the rod lens telescope. The airway was visualized but the straightness of the tube could not intubate due to the tongue pushing posteriorly. Three attempts at intubation in this way were unsuccessful. A Miller 1 was tried but immediately found to result in poorer exposure. After switching back to a Parsons 1 and visualizing the arytenoid and epiglottis, a stylet was used to successfully intubate with a 3.0 microcuff endotracheal tube with a slight curve. The incision was made percutaneously at the apex of the mass. An additional 10 mL of serosanguinous fluid was expressed from the mass via incision and drainage before the wound was irrigated with saline and packed with plain gauze strip. The patient was started empirically on intravenous cefepime and clindamycin and weaned and extubated on postoperative day 2. After recommendations from Infectious Disease, she was discharged on postoperative day 5 on a course of Augmentin after cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus with anticipation of surgical cyst excision in 6 months. A repeated ultrasound at discharge showed a small, subcentimeter collection with mild internal debris measuring 0.5×0.5×0.3 cm and no indications of significant inflammatory change. The patient was followed closely and started on cephalexin prophylaxis to prevent recurrence of infection. A CT scan was performed prior to surgery, which showed a thin-walled, smooth, well-defined, homogeneously fluid-dense lesion located anterior mid-line. A Sistrunk procedure was performed 6 months later with no complications. Following definitive resection, the neck mass was confirmed by histology to be a TGDC.

Discussion

A literature review of pediatric TGDC using the electronic database Medline via PubMed (2000–2021) was performed to determine the age of presentation and infection frequency of patients with pediatric TGDC, as seen in Table 1. Studies including adult populations or in a language other than English were excluded.

Table 1.

Summary of pediatric TGDC in the literature.

| Author | Number of patients studied | Mean age at presentation (years) | SD of age at presentation (years) | Age range at presentation | Infection frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rattan et al [8] (2020) | 71 | 7.15 | ND | ND | ND |

| Ross et al [17] (2017) | 108 | 6 | ND | 6 months to 20 years | 27.8% |

| Zaman et al [10] (2017) | 39 | 8.2 | ±3.8 | ND | ND |

| Al-Thani et al [20] (2016) | 67 | 10.4 | ±5.4 | ND | 3.0% |

| Kepertis et al [21] (2015) | 33 | 6.125 | ND | 9 months to 13 years | 12.12% |

| Geller et al [22] (2014) | 128 | 5.1 | ND | 2 months to 14 years | 50.4% |

| Hussain et al [23] (2013) | 93 | 6.1 | ND | 1.1 years to 15.3 years | ND |

| Pradeep et al [9] (2013) | 16 | 9 | ±1.4 | ND | 0% |

| Simon et al [18] (2012) | 120 | 5.1 | ND | 6.5 weeks to 13 years | 40.8% |

| Ren et al [11] (2011) | 47 | 7.0 | ±4.2 | ND | ND |

| Lin et al [24] (2008) | 32 | 6.1 | ±3.5 | ND | ND |

| Brousseau et al [12] (2003) | 21 | 6 | ±5 | ND | 43% |

| Marianowski et al [15] (2003) | 57 | 4 | ±2.6 | ND | ND |

SD – standard deviation; ND – no data.

Results from the literature review show a mean age of presentation of 6–10 years, with the youngest patient being 2 months old. Preoperative infection frequency greatly varies among studies. This supports the rarity of an infected TGDC presentation in a 3-week-old neonate.

Although TGDCs are the most common pediatric mass, studies have shown they present in a bimodal distribution, peaking in children and adults. The consensus is that the cyst most often presents as an asymptomatic midline cyst in children, although some studies have found a thyroglossal fistula is most common. These studies also found that an asymptomatic midline neck mass is the most common presentation in adults [8,9]. However, adults have been found to be more likely to present with a concern other than mass or infection, including pain, dysphagia, dysphonia, and fistula formation. Airway obstruction, although very rare, occurred equally among adult and pediatric study subjects [10–12]. Airway obstruction is much more common in a lingual TGDC [13,14]. There is evidence to suggest older children (5 years old or older) are more likely to present with an infected TGDC, but more research is needed to confirm this [3]. Because the frequency of infection and presenting symptomatology is highly variable in study outcomes among children, clinicians should have a high suspicion for TGDC with any midline neck mass and be aware of the most common morbid complications. Further evaluation with imaging can be used for diagnosis.

Proper management of infected TGDC when the cyst presents with airway obstruction and respiratory distress is unclear.

Traditionally, incision and drainage has been avoided, with reliance on parenteral antibiotics and needle aspiration for refractory cases. Incision and drainage can create scarring and obscure tissue planes, making dissection difficult and decreasing the likelihood of successful surgical extirpation. However, there has recently been much deliberation about the utility of the procedure. Historically, recurrence rates of TGDC double when treated with incision and drainage versus antibiotics alone [15,16], but more recent studies have found the opposite to be true. This is because incision and drainage are thought to decrease the duration of inflammation, only affect the localized tissues, and lessen the scarring and destruction from the extensive inflammation due to the cyst itself [17–19]. In any event, we support the use of incision and drainage when the airway is at risk of obstruction, as this is a worse complication than recurrence of the TGDC. The Sistrunk procedure may be utilized to fully excise the TGDC later.

The Sistrunk procedure is known to be the criterion standard for surgical treatment of TGDC, yielding the lowest recurrence rates. The procedure resects the midline portion of the hyoid bone and a wide core of tissue belonging to the midline between the hyoid and foramen cecum. This attempts to fully remove the thyroglossal duct remnants. The most common complication of the Sistrunk procedure is recurrence of the TGDC, occurring in approximately 10% of patients. Risk factors increasing the recurrence rate are the presence of infection, age less than 2 years old, cyst lobulation, intraoperative rupture, incomplete excision, dermal involvement, and cases with fistulas [1,14,15]. Our patient was at high risk for recurrence due to the presence of infection and age less than 2 years. As in our patient, the increased risks should be explained to the patient and their family. More research is needed to determine why risk for recurrence is increased and how to reduce this risk in these patients.

Conclusions

Although TGDC rarely presents in the neonatal period, clinicians should keep the diagnosis in their differential when evaluating an asymptomatic midline neck mass. Serious complications such as infection and airway obstruction can occur if not treated promptly. Although use of only antibiotics has been the traditional treatment regimen for infected TGDC, incision and drainage should also be considered when there is risk of airway obstruction. While the Sistrunk procedure has become the standard surgical treatment for TGDC, there is an increased risk for recurrence in patients with clear risk factors such as infection and young age, and more management guidance is needed to reduce the risk for these patients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1..Amos J, Shermetaro C. Thyroglossal duct cyst. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519057/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2..Patel S, Bhatt AA. Thyroglossal duct pathology and mimics. Insights Imaging. 2019;10(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3..Shah R, Gow K, Sobol SE. Outcome of thyroglossal duct cyst excision is independent of presenting age or symptomatology. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(11):1731–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4..Nightingale M. Midline cervical swellings: What a paediatrician needs to know. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(11):1086–90. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5..Zimmerman KO, Hupp SR, Bourguet-Vincent A, et al. Acute upper-airway obstruction by a lingual thyroglossal duct cyst and implications for advanced airway management. Respir Care. 2014;59(7):e98–e102. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6..Atmaca S, Çeçen A, Kavaz E. Thyroglossal duct cyst in a 3-month-old infant: A rare case. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;54(3):138–40. doi: 10.5152/tao.2016.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7..Deaver MJ, Silman EF, Lotfipour S. Infected thyroglossal duct cyst. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(3):205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8..Rattan KN, Kalra VK, Yadav SPS, et al. Thyroglossal duct remnants: A comparison in the presentation and management between children and adults. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;72(2):184–86. doi: 10.1007/s12070-019-01742-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9..Pradeep PV, Jayashree B. Thyroglossal cysts in a pediatric population: Apparent differences from adult thyroglossal cysts. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(1):45–48. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10..Zaman SU, Ikram M, Awan MS, et al. A decade of experience of management of thyroglossal duct cyst in a tertiary care hospital: Differentiation between children and adults. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;69(1):97–101. doi: 10.1007/s12070-016-1037-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11..Ren W, Zhi K, Zhao L, et al. Presentations and management of thyroglossal duct cyst in children versus adults: A review of 106 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111(2):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12..Brousseau VJ, Solares CA, Xu M, et al. Thyroglossal duct cysts: Presentation and management in children versus adults. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67(12):1285–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13..Burkart CM, Richter GT, Rutter MJ, et al. Update on endoscopic management of lingual thyroglossal duct cysts. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(10):2055–60. doi: 10.1002/lary.20534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14..Gioacchini FM, Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Kaleci S, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes of thyroglossal duct cysts: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(1):119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15..Marianowski R, Ait Amer JL, Morisseau-Durand MP, et al. Risk factors for thyroglossal duct remnants after Sistrunk procedure in a pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16..Athow AC, Fagg NL, Drake DP. Management of thyroglossal cysts in children. Br J Surg. 1989;76(8):811–14. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17..Ross J, Manteghi A, Rethy K, et al. Thyroglossal duct cyst surgery: A ten-year single institution experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;101:132–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18..Simon LM, Magit AE. Impact of incision and drainage of infected thyroglossal duct cyst on recurrence after Sistrunk procedure. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(1):20–24. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19..Ostlie DJ, Burjonrappa SC, Snyder CL, et al. Thyroglossal duct infections and surgical outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(3):396–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20..Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A, Sulaiti MA, et al. Presentation, management, and outcome of thyroglossal duct cysts in adult and pediatric populations: A 14-year single center experience. Oman Med J. 2016;31(4):276–83. doi: 10.5001/omj.2016.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21..Kepertis C, Anastasiadis K, Lambropoulos V, et al. Diagnostic and surgical approach of thyroglossal duct cyst in children: Ten years data review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(12):PC13–15. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14190.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22..Geller KA, Cohen D, Koempel JA. Thyroglossal duct cyst and sinuses: A 20-year Los Angeles experience and lessons learned. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(2):264–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23..Hussain K, Henney S, Tzifa K. A ten-year experience of thyroglossal duct cyst surgery in children. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(11):2959–61. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24..Lin ST, Tseng FY, Hsu CJ, et al. Thyroglossal duct cyst: A comparison between children and adults. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29(2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]