Abstract

The yield coefficient (YC) of Pseudomonas sp. strain DP-4, a 2,4-dichlorophenol (DCP)-degrading organism, was estimated from the number of CFU produced at the expense of 1 unit amount of DCP at low concentrations. At a low concentration of DCP, the YC can be overestimated in pure culture, because DP-4 assimilated not only DCP but also uncharacterized organic compounds contaminating a mineral salt medium. The concentration of these uncharacterized organic compounds was nutritionally equivalent to 0.7 μg of DCP-C ml−1. A mixed culture with non-DCP-degrading organisms resulted in elimination of ca. 99.9% of the uncharacterized organic compounds, and then DP-4 assimilated only DCP as a substrate. In a mixed culture, DP-4 degraded an initial concentration of 0.1 to 10 μg of C ml of DCP−1 and the number of CFU of DP-4 increased. In the mixed culture, DCP at an initial concentration of 0.07 μg of C ml−1 was degraded. However, the number of CFU of DP-4 did not increase. DCP at an extremely low initial concentration of 0.01 μg of C ml−1 was not degraded in mixed culture even by a high density, 105 CFU ml−1, of DP-4. When glucose was added to this mixed culture to a final concentration of 1 μg of C ml−1, the initial concentration of 0.01 μg of C ml of DCP−1 was degraded. These results suggested that DP-4 required cosubstrates to degrade DCP at an extremely low initial concentration of 0.01 μg of C ml−1. The YCs of DP-4 at the expense of DCP alone decreased discontinuously with the decrease of the initial concentration of DCP, i.e., 1.5, 0.19, or 0 CFU per pg of DCP-C when 0.7 to 10, 0.1 to 0.5, or 0.07 μg of C ml of DCP−1 was degraded, respectively. In this study, we developed a new method to eliminate uncharacterized organic compounds, and we estimated the YC of DP-4 at the expense of DCP as a sole source of carbon.

In order to enhance the biodegradation of chemicals of environmental concern, the inoculation of microorganisms capable of degrading the chemicals has been reported (7, 12). However, the attempts did not always produce desired results. One possible reason for the failure of inoculation is the failure of the responsible microorganisms to grow, since in a natural environment, the concentrations of the chemicals are generally low (5, 9, 10). If the density of the microorganism is insufficient, the degradation of the chemicals is not detectable (16, 24). Therefore, studies of the growth of responsible microorganisms at low chemical concentrations are indispensable to enhance the biodegradation of the chemicals.

Studies of the yield coefficient (YC), i.e., the efficiency of biomass production at the expense of the chemicals of concern which provide energy and carbon sources, are indispensable to the kinetic analysis of degradation of the compounds (19). However, measurements of YC in the laboratory have sometimes been overestimated, especially when the concentration of the chemical of concern was low, because microorganisms utilized not only the chemical of concern but also uncharacterized organic compounds contaminating the inorganic medium from water, glassware, or air (1, 4, 6, 14, 20). Therefore, the YC that was observed reflected the combined influence of the chemicals of concern and uncharacterized organic compounds, rather than the YC of the chemicals alone (1, 14, 20).

In our previous study (20), we proposed a method to eliminate uncharacterized organic compounds by using bacterial communities which did not utilize the chemicals of concern. In this study, by using this method, we estimated the YC of the 2,4-dichlorophenol (DCP)-degrading Pseudomonas sp. strain DP-4 at the expense of DCP alone as a model chemical of environmental concern, and the effect of the concentration of DCP on YC is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental microorganisms.

Pseudomonas sp. strain DP-4 (17) was used as a DCP degrader. Strain DP-4 was isolated from an enrichment culture inoculated with sewage, soil, and activated sludge. This bacterium is gram-negative and rod-shaped and has a polar flagellum (17). DP-4 was cultured in a mineral salts (MS) medium with or without the heterotrophic bacterial community which is described below.

The heterotrophic bacterial community was obtained from groundwater pumped up from a 250-m depth from the campus of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan. To eliminate eucaryotic microorganisms, the microbial community was incubated for a few days with 100 μg of cycloheximide ml−1 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.) and 50 μg of nystatin ml−1 (Wako) and then passed through a sterilized 5-μm-pore-sized membrane filter (Millex-SV; Millipore Corp.). The heterotrophic bacterial community was obtained and stored in a sterilized MS medium. It was ascertained by preliminary study that the heterotrophic bacterial community did not degrade 0.01 to 10 μg of C ml of DCP−1 in MS medium.

Cultivation of DP-4.

Pure-culture experiments of DP-4 were performed by adding the desired amount of DCP and DP-4 suspension to 1,000 ml of a sterilized MS medium in a 1.2-liter screw-cap glass bottle.

Mixed-culture experiments of DP-4 with the heterotrophic bacterial community were performed as described below; 1 ml of the heterotrophic bacterial community was added to 1,000 ml of sterilized MS medium in a 1.2-liter screw-cap glass bottle and incubated for 1 week. Then, the desired amount of DCP or DP-4 suspension was added.

The DP-4 suspension was prepared by culturing DP-4 for a few days in MS medium which was supplemented with (in micrograms of C ml−1) yeast extract (Difco) (10), glucose (5), glycerin (5), and sodium l-glutamate (5). Then the culture was diluted with sterilized ion-exchanged water to achieve the desired density of DP-4.

All the cultures were incubated aerobically at 25°C in the dark.

Analysis of concentration of DCP.

The concentration of DCP was analyzed on a high-performance liquid chromatography system (16), consisting of a Yanaco L-4000W pump (Yanagimoto Co., Ltd.), a Shodex M-315 UV-visible variable-wavelength detector (Showa Denko K. K.) set at 254 nm, and a Shodex RSpak DS-613 and RSpak DS-613(p) column (Showa Denko). The eluent consisted, in volume, of 40% ion-exchanged water and 60% methanol. The pH was adjusted to 11.2 by 6.25 mM Na2HPO4 and 1.5 mM NaOH. The flow rate was 1.0 ml min−1. If necessary, DCP in a 25-ml subsample from the culture was concentrated with a Sep-pak plus tC18 cartridge (Waters Corp.) to 2.5 ml of sample (20).

The measurement of the density of DP-4 and total heterotrophic bacterial community.

The density of DP-4 was measured by a CFU method with DP-4 selective agar medium in which the heterotrophic bacterial community, except for DP-4, could not grow. DP-4 selective agar medium contained 0.7 mg of nutrient agar (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd.), 8 mg of agar (Kyokuto Co., Ltd.), 200 μg of carbenicillin sodium (Wako), 70 μg of bacitracin (Wako), 15 μg of ampicillin sodium (Wako) and 20 μg of C of DCP (Wako) per ml of modified MS (mMS) medium. Subsamples from the MS medium were diluted with sterilized ion-exchanged water by 10-fold serial dilution. The 1-ml portion thus obtained was poured into DP-4 selective agar medium. The medium was incubated for 7 days.

The density of the total heterotrophic bacterial community, including DP-4, was measured by the CFU method with a medium which contained only 0.7 mg of nutrient agar and 8 mg of agar per ml of MS medium.

Composition of MS or mMS medium.

The MS medium contained 2.1 μM Na2HPO4, 0.9 μM KH2PO4, 40 μM NH4NO3, 10 μM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 10 μM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 3 μM Na2SiO3, 1 μM MnCl2 · 4H2O, 1 μM H3BO3, 1 μM Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 5 nM FeCl3 · 6H2O, 5 nM CuSO4 · 5H2O, 5 nM ZnSO4 · 7H2O, and 5 nM CoSO4 · 7H2O in ion-exchanged water. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 to 7.2. The mMS medium contained 2.1 mM Na2HPO4, 0.9 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM NH4NO3, 0.1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 30 μM Na2SiO3, 10 μM MnCl2 · 4H2O, 10 μM H3BO3, 10 μM Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 50 nM FeCl3 · 6H2O, 50 nM CuSO4 · 5H2O, 50 nM ZnSO4 · 7H2O, and 50 nM CoSO4 · 7H2O in ion-exchanged water. The pH was 7.2.

Estimation of YC.

In this investigation, the YC of DP-4 was defined as follows: YC = (Bt − B0)/Sd, where Bt is the density of DP-4 at the end of incubation, B0 is the initial density of DP-4, and Sd is the amount of DCP degraded per milliliter of medium. Because of the difficulty in measuring the biomass of DP-4 at low density or in mixed culture, YC was expressed as the number of CFU of DP-4 produced at the expense of 1 unit amount of DCP.

All experiments were carried out in duplicate.

RESULTS

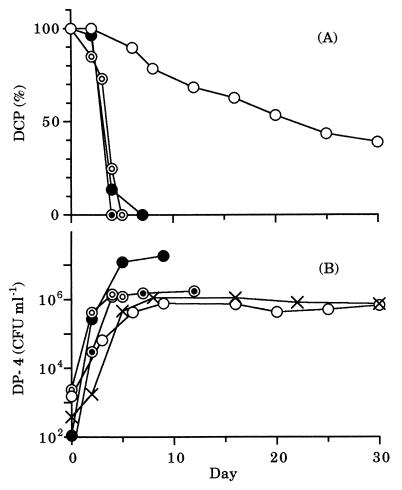

In pure culture of DP-4 in MS medium (Fig. 1A), all the DCP was degraded when the initial concentration of DCP added was 10, 1, or 0.1 μg of C ml−1. On the other hand, 60% of DCP was degraded during a 30-day incubation period when the initial concentration of DCP added was 0.01 μg of C ml−1. The density of DP-4 increased to more than 105 CFU ml−1, irrespective of the initial concentration of DCP added (Fig. 1B). Even when no DCP was added, the density of DP-4 increased to ca. 106 CFU ml−1. Therefore, the increase of the density of DP-4 was attributable to the expense not only of DCP but also of uncharacterized organic compounds contaminating the MS medium.

FIG. 1.

Change in concentration of DCP (A) or density of DP-4 (B) in pure culture. The initial concentration of DCP added was 10 (●), 1 (⦿), 0.1 (◎), 0.01 (○), or 0 (×) μg of C ml−1.

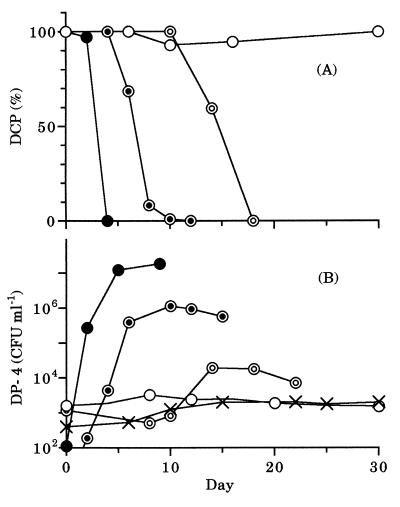

In a mixed culture of DP-4 with the heterotrophic bacterial community (Fig. 2A), all the DCP was degraded when the initial concentration of DCP added was 10, 1, or 0.1 μg of C ml−1. On the other hand, no DCP was degraded during a 30-day incubation period when the initial concentration of DCP was 0.01 μg of C ml−1. The density of DP-4 increased to 1.2 × 107, 1.1 × 106, or 1.9 × 104 CFU ml−1 when the initial concentration of DCP added was 10, 1, or 0.1 μg of C ml−1, respectively (Fig. 2B). When the initial concentration of DCP added was 0.01 μg of C ml−1 or no DCP was added, the density of DP-4 did not increase and was almost constant at ca. 103 CFU ml−1 during the incubation period. This suggested that uncharacterized organic compounds had almost been eliminated by the heterotrophic bacterial community and that DP-4 utilized DCP as a sole source of carbon and energy. The density of the total heterotrophic bacterial community was ca. 106 to 107 CFU ml−1 during the incubation period, irrespective of the initial concentration of DCP added (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Change in concentration of DCP (A) or density of DP-4 (B) in mixed culture. Symbols are as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

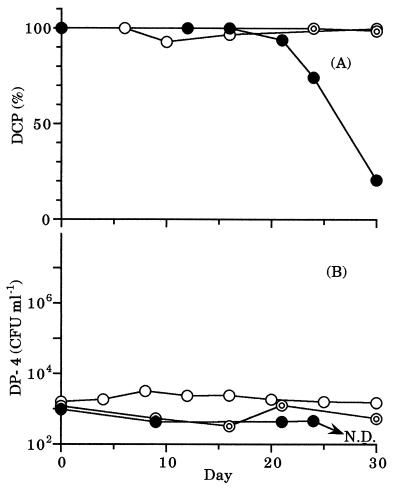

In mixed culture, 80% of DCP was degraded during the 30-day incubation period when the initial concentration of DCP was 0.07 μg of C ml−1 (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, no DCP was degraded when the initial concentration of DCP was 0.05 or 0.01 μg of C ml−1. The density of DP-4 did not increase (Fig. 3B), even when DCP was partially degraded. The density of the total heterotrophic bacterial community was ca. 106 CFU ml−1 during the incubation period, irrespective of the initial concentration of DCP added (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Change in concentration of DCP (A) or density of DP-4 (B) in mixed culture. The initial concentration of DCP added was 0.07 (●), 0.05 (◎), or 0.01 (○) μg of C ml−1. N.D., not detected.

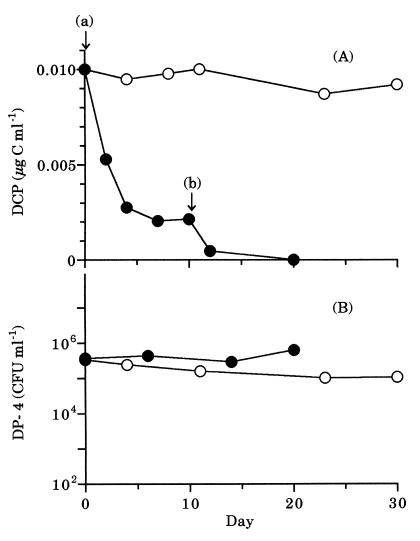

DP-4 in a mixed culture was unable to degrade DCP at a concentration of 0.01 μg of C ml−1 without the addition of glucose (Fig. 4A). However, DP-4 degraded DCP completely by two additions of glucose at a final concentration of 1 μg of C ml−1. The density of DP-4 was almost constant at ca. 105 CFU ml−1, irrespective of the addition of glucose (Fig. 4B). The density of the total heterotrophic bacterial community was ca. 106 CFU ml−1, irrespective of the addition of glucose (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Change in concentration of DCP (A) or density of DP-4 (B) in mixed culture with (●) or without (○) the addition of glucose. The arrow (at a and b) indicates the first or second addition of glucose to a final concentration of 1 μg of C ml−1, respectively.

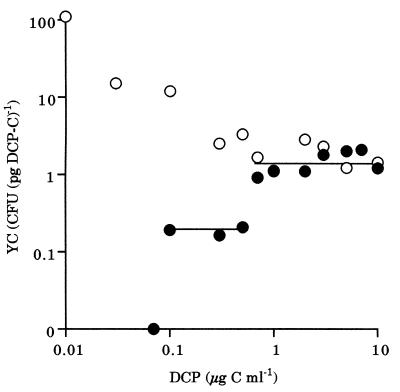

In pure culture, the YC of DP-4 apparently increased with the decrease of the initial concentration of DCP added (Fig. 5). In mixed culture, however, the YC of DP-4 decreased discontinuously with the decrease of the initial concentration of DCP added and was estimated by an arithmetic mean to be 1.5, 0.19, or 0 CFU per pg of DCP-C when the initial concentration of DCP added was in the range of 0.7 to 10, 0.1 to 0.5, or 0.07 μg of C ml−1, respectively. The YC could not be estimated when the initial concentration of DCP added was less than 0.05 μg of C ml−1, because neither the degradation of DCP nor the increase in the density of DP-4 was observed.

FIG. 5.

Relationship between the initial concentration of DCP added and the YC of DP-4 in pure culture (○) or mixed culture (●).

DISCUSSION

The overestimation of YC of DP-4 in pure culture was attributable to the presence of uncharacterized organic compounds contaminating the MS medium, which allowed DP-4 to grow. For example, the amount of uncharacterized organic compounds in synthetic liquid medium was reported to be 2 (6), 0.1 (14), or from 0.1 to 1 (18) μg ml−1 in terms of the amount of carbon, and the density of microorganisms increased to 107, 105, or 105 to 106 cell ml−1, respectively. In our previous study (18), the density of DP-4 increased to 105 cell ml−1, even in double-distilled water. If we assume that the YC at the expense of uncharacterized organic compounds was equal to the YC at the expense of 1 μg of C ml of DCP−1, the amount of uncharacterized organic compounds estimated in this study was ca. 0.7 μg of C ml−1, because the density of DP-4 was 1.1 × 106 CFU ml−1 at the stationary phase in pure culture without DCP (Fig. 1B). Therefore, to estimate the YC at the expense of DCP, the elimination of uncharacterized organic compounds contaminating synthetic medium is indispensable, especially when the concentration of DCP is low.

Mixed culture with a heterotrophic bacterial community, as used in this study, seemed to be a simple and effective way to eliminate uncharacterized organic compounds, because the density of DP-4 was almost constant in a mixed culture without DCP (Fig. 2B). The density of DP-4 in the mixed culture without DCP was ca. 1/1,000-fold lower than that of the pure culture. This suggested that DP-4 could utilize only 0.1% of uncharacterized organic compounds and that the heterotrophic bacterial community then eliminated ca. 99.9% of the uncharacterized organic compounds.

The reason for using a bacterial community from a natural environment to eliminate uncharacterized organic compounds is that in the preliminary study, bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, or some isolates which were obtained from groundwater, rivers, or lakes could not effectively eliminate the uncharacterized organic compounds. DP-4 inoculated to a final density of 103 ml−1 increased to 105 to 106 ml−1 in MS medium cultured with these bacteria (data not shown). The heterotrophic bacterial community used in this study seemed not to affect the growth or activity of DP-4 except for the elimination of uncharacterized organic compounds.

The reason for the discontinuous decrease of YC with the decrease in concentration of DCP is not clear. One possible explanation is that different degradation systems are involved in the DCP degradation, as a number of studies have reported (1, 22). Another hypothesis, such as the effect of maintenance loss (2, 23) of DP-4, is probably negligible. If the maintenance coefficient was almost the same as that of Pseudomonas aeruginosa of 0.26 mg of C per gram of biomass C per hour (15), then 105 DP-4 cells ml−1, whose C biomass per cell is 0.1 pg (21), will consume only 1.9 ng of C ml−1 of DCP for maintenance, even in the 30-day incubation period. There was enough DCP to allow DP-4 to increase to a density of 105 cells ml−1 when 0.1 μg of DCP-C ml−1 was added.

The problem of this method is that we couldn't measure the biomass of DP-4 because of experimental restrictions. Since cell size generally becomes smaller under oligotrophic conditions (11), the YC of DP-4 at the low concentration of DCP is probably even lower than at a high concentration of DCP if the YC of DP-4 was expressed in terms of biomass.

The failure of degradation of 0.01 or 0.05 μg of C ml of DCP−1 in mixed culture (Fig. 3A) was not attributable to the low density of DP-4 of 103 CFU ml−1, because even a higher density of 105 CFU ml of DP-4−1 did not degrade that level of DCP in mixed culture without the addition of glucose (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, DP-4 degraded 0.01 μg of C ml of DCP−1 in pure culture (Fig. 1A) or in mixed culture with glucose supplementation when the density of DP-4 was 105 CFU ml−1 (Fig. 4). These results suggested that DP-4 required auxiliary organic compounds, rather than high density, to degrade extremely low concentrations of DCP, such as 0.01 μg of C ml−1. Although this phenomenon is similar to cometabolism (3, 8), we couldn't confirm whether DP-4 specifically cometabolized 0.01 μg of C ml of DCP−1. We should have used 14C-labeled DCP, but it was impossible because of our equipment restrictions. For example, Schmidt and Alexander (13) have reported a similar phenomenon by using 14C-labeled glucose, in which Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mineralized glucose at a high concentration, but not at a low concentration, as its sole source of carbon and mineralized a low concentration of glucose if a cosubstrate was contained. In their study, however, both significant growth of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and the acceleration of degradation were observed simultaneously. Interestingly, they observed no differences in the percentage of glucose carbon incorporated into cells between the time when the bacterium grew at a high concentration of glucose alone and when it grew at a low concentration of glucose with a cosubstrate.

The results obtained in this study with DP-4 suggest that the biodegradation of extremely low concentrations of chemicals may be controlled by the presence of higher concentrations of other available substrates, as a number of studies have reported (7, 12, 25). The data also suggest that the inoculation of microorganisms to enhance the biodegradation of chemicals in polluted natural environments will not always give satisfactory results, because the concentrations of available substrates for microorganisms are generally extremely low in natural environments (11). We need more information about ecological or physiological factors which affect the biodegradation of low concentrations of chemicals that are assimilated at higher concentrations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aa K, Olsen R A. The use of various substrates and substrate concentrations by a Hyphomicrobium sp. isolated from soil: effect on growth rate and growth yield. Microb Ecol. 1996;31:67–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00175076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelissen G, Sijm D T H M. An energy budget model for the biodegradation and cometabolism of organic substances. Chemosphere. 1996;33:817–830. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(96)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton H, Stirling D I. Co-metabolism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1982;297:481–496. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favero M S, Carson L A, Bond W W, Petersen N J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: growth in distilled water from hospitals. Science. 1971;173:836–838. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3999.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank R, Clegg B S, Sherman C, Chapman N D. Triazine and chloroacetamide herbicides in Sydenham River water and municipal drinking water, Dresden, Ontario, Canada, 1981–1987. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1990;19:319–324. doi: 10.1007/BF01054972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geller A. Growth of bacteria in inorganic medium at different levels of airborne organic substances. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:1258–1262. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.6.1258-1262.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein R M, Mallory L M, Alexander M. Reasons for possible failure of inoculation to enhance biodegradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:977–983. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.4.977-983.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath R S. Microbial co-metabolism and the degradation of organic compounds in nature. Bacteriol Rev. 1972;36:146–155. doi: 10.1128/br.36.2.146-155.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarty P L, Reinhard M, Rittmann B E. Trace organics in ground water. Environ Sci Technol. 1981;15:40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijers A P, van der Leer R C. The occurrence of organic micropollutants in the river Rhine and the river Maas in 1974. Water Res. 1976;10:597–604. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita R Y. Starvation-survival of heterotrophs in the marine environment. Adv Microbial Ecol. 1982;6:171–197. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pahm M A, Alexander M. Selecting inocula for the biodegradation of organic compounds at low concentrations. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:275–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00171893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt S K, Alexander M. Effects of dissolved organic carbon and second substrates on the biodegradation of organic compounds at low concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:822–827. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.4.822-827.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seto M, Alexander M. Effect of bacterial density and substrate concentration on yield coefficients. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;50:1132–1136. doi: 10.1128/aem.50.5.1132-1136.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seto M, Iwamoto M. Respiratory rate and survival of a bacterium (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) under starved condition. Man Environ. 1988;14:11–19. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seto M, Ikejima K, Nakano S. Some observations on the density of chlorophenol-degrader and the degradation of chlorophenol in water sample from the river Tamagawa. Man Environ. 1989;14:12–19. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seto M, Tsurui F. Survival of 2,4-dichlorophenol (DCP)-degraders and their expression of DCP-degrading activity in water samples from aquatic environment. Man Environ. 1989;15:18–24. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seto M, Tanaka Y, Homma T, Yamasaki A. Degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol at low concentrations and biomass production by microorganisms. Man Environ. 1992;18:15–20. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simkins S, Alexander M. Models for mineralization kinetics with the variables of substrate concentration and population density. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:1299–1306. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.6.1299-1306.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarao M, Tsunozaki K, Seto M. Biodegradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol at low concentration and specific growth rate of Pseudomonas sp. strain DP-4. Bull Jpn Soc Microb Ecol. 1993;8:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarao M, Itoh M, Seto M. Second-order rate constants as affected by some environmental factors in pure culture system of 2,4-dichlorophenol-Pseudomonas sp. strain DP-4. Man Environ. 1999;25:2–7. . (In Japanese with English summary.) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tros M E, Schraa G, Zehnder A J B. Transformation of low concentrations of 3-chlorobenzoate by Pseudomonas sp. strain B13: kinetics and residual concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:437–442. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.437-442.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Kooij D, Visser A, Hijnen W A M. Growth of Aeromonas hydrophila at low concentrations of substrates added to tap water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:1198–1204. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.6.1198-1204.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiggins B A, Jones S H, Alexander M. Explanations for the acclimation period preceding the mineralization of organic chemicals in aquatic environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:791–796. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.791-796.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaidi B R, Mehta N K. Effects of organic compounds on the degradation of p-nitrophenol in lake and industrial waste water by inoculated bacteria. Biodegradation. 1995;6:275–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00695258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]