Abstract

Salmonella enterica is among the principal etiological agents of food-borne illness in humans. Increasing antimicrobial resistance in S. enterica is a cause for worldwide concern. There is concern at present in relation to the increasing incidence of human infection with antimicrobial agent-resistant strains of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium, in particular of phage type DT104. Integrons appear to play an important role in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes in many Enterobacteriaceae including S. enterica. In this study the antimicrobial susceptibilities and phage types of 74 randomly collected strains of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium from the Cork region of southern Ireland, obtained from human, animal (clinical), and food sources, were determined. Each strain was examined for integrons and typed by DNA amplification fingerprinting (DAF). Phage type DT104 predominated (n = 48). Phage types DT104b (n = 3), -193 (n = 9), -195 (n = 6), -208 (n = 3), -204a (n = 2), PT U302 (n = 1), and two nontypeable strains accounted for the remainder. All S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains were resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, Sulfonamide Duplex, and tetracycline, and one strain was additionally resistant to trimethoprim. All DT104 strains but one were of a uniform DAF type (designated DAF-I) and showed a uniform pattern of integrons (designated IP-I). The DT104b and PT U302 strains also exhibited the same resistance phenotype, and both had the DAF-I and IP-I patterns. The DAF-I pattern was also observed in a single DT193 strain in which no integrons were detectable. Greater diversity of antibiograms and DAF and IP patterns among non-DT104 phage types was observed. These data indicate a remarkable degree of homogeneity at a molecular level among contemporary isolates of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 from animal, human, and food sources in this region.

Two serotypes of Salmonella predominate worldwide, the poultry-associated S. enterica serotype Enteritidis and S. enterica serotype Typhimurium, which has a wider animal reservoir. Both of these serotypes can be subdivided by phage typing; some of the S. enterica serotype Typhimurium phage types are referred to as definitive types (DT). S. enterica serotype Typhimurium phage type DT104 is causing particular concern because of its increasing prevalence and acquisition of multiple antibiotic resistance (11, 25, 26, 29). The selective pressure created by widespread use of antimicrobial agents in animal and poultry husbandry may have contributed to the dissemination of these multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains. Detailed characterization of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium strains from animal, human, and clinical sources may improve our understanding of the epidemiology of this zoonotic infection.

S. enterica is one of the most common food-borne pathogens identified in Great Britain and Ireland. In the United States 800,000 to 4 million Salmonella infections occur annually, of which approximately 1 to 5% are confirmed as due to S. enterica serotype Typhimurium by standard laboratory methods, on the basis of data reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (11). This organism has the potential to infect a variety of animal species, and therefore a diverse range of foods can become contaminated making control difficult. Recent data signaled the emergence of MDR S. enterica serotype Typhimurium (8, 11, 25, 26, 29; M. Cormican, C. O'Hare, D. Morris, G. Corbett-Feeney, and J. Flynn, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. A-103, p. 22, 1999), most isolates of which were found to be resistant to at least five common antibiotics, including ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline (ACSSuT). Furthermore the increasing incidence of trimethoprim and nalidixic acid resistance (8, 14, 20) together with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinone) is of particular concern. It is well established that the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance is often plasmid and/or transposon mediated. Integrons, a novel group of mobile DNA elements originally identified in gram-negative bacteria, have the potential to incorporate several antibiotic resistance genes by site-specific recombination (7, 13, 19, 24). Recent reports demonstrated that antimicrobial resistance genes are clustered in the genome of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 (6, 20) and that these genes can be efficiently transduced by P22-like phages (22).

In the United Kingdom, infections with MDR strains are reported to be associated with an increased morbidity and mortality compared to other Salmonella infections (29). The increasing incidence in animals and humans of infection with a single MDR phage type requires investigation. It is essential that relevant epidemiological data be available to monitor organism spread and patterns of infection through animals, food, and humans. In this study 74 randomly selected S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates from animal, food, and human sources in the Cork region of Ireland submitted to the Molecular Diagnostics Unit between 1997 and 1998 were studied. Our objectives were to determine the predominant serogroups of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium in this region using phenotypic and molecular methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 74 S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates were investigated in this study, all of which are listed in Table 1. These isolates were collected between the end of 1997 and the end of 1998 from animal (clinical), human, and food sources. Cork University Hospital, the Cork Regional Veterinary Laboratory, and the Cork County Council Food Laboratory, respectively, submitted the isolates to the Molecular Diagnostics Unit for study. The majority of the strain collection reported here are bovine isolates taken from different farms and regions in the greater Cork area. All isolates were identified as S. enterica serotype Typhimurium based on colony morphology, API 20NE (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) biotyping, and serotyping. Isolates were stored on nutrient agar slopes at 4°C and when required were initially grown on XLD agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) to assess culture purity and then in tryptone soy broth (Oxoid). The isolates were also maintained on cryostat beads (Mast Diagnostics, Merseyside, United Kingdom) at −20°C for long-term storage.

TABLE 1.

Data for S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates

| Isolate | Yr | Sourcea | Phage typeb | R typed | DAF pattern | IP group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIT-H 8 | 1997 | Human | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-H23 | 1997 | Human | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F30 | 1997 | Swine | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V31 | 1997 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F32 | 1997 | Premince beef | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F33 | 1997 | Poultry carcass | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-H35 | 1997 | Human | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V39 | 1998 | Swine | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F45 | 1998 | Swine | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V57 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V59 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V61 | 1998 | Bovine fetus | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V62 | 1997 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V63 | 1997 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V64 | 1998 | Swab pens | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V65 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V66 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V67 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V68 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V69 | 1998 | Ovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V70 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V71 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V72 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V73 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V74 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V78 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V80 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V81 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V82 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V83 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V84 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V85 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V86 | 1998 | Ovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V87 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V89 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V90 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V91 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V92 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V93 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V94 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V95 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-V96 | 1998 | Bovine feces | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F100 | 1998 | Cooked poultry | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F101 | 1998 | Black pudding | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F103 | 1998 | Cooked poultry | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F104 | 1998 | Cooked poultry | 104 | ACSSuT | I | I |

| CIT-F107 | 1998 | Cooked swine | 104b | ACSSuTK | I | I |

| CIT-F108 | 1998 | Cooked swine | 104b | ACSSuTK | I | I |

| CIT-F109 | 1998 | Cooked swine | 104b | ACSSuTK | I | I |

| CIT-V36 | 1998 | Unknown | 104 | ACSSuTTp | I | I |

| CIT-V38 | 1998 | Swine | 104 | ACSSuT | XI | I |

| CIT-F44 | 1998 | Swine | 193 | ASu | I | III |

| CIT-F41 | 1998 | Swine | 193 | ASSuTTp | II | II |

| CIT-F34 | 1997 | Bovine milk | 193 | ASSuTN | III | Nonec |

| CIT-F43 | 1998 | Swine | 193 | ASSuT | III | None |

| CIT-F47 | 1998 | Swine | 193 | ASSuT | III | None |

| CIT-V56 | 1998 | Porcine tissue | 193 | ASSuT | III | None |

| CIT-V77 | 1998 | Porcine feces | 193 | SuTTp | IV | IV |

| CIT-V79 | 1998 | Canine feces | 193 | ASuTTp | IV | IV |

| CIT-V88 | 1998 | Porcine tissue | 193 | ASSuT | IV | IV |

| CIT-H12 | 1997 | Human | 195 | T | II | None |

| CIT-H16 | 1997 | Human | 195 | T | II | None |

| CIT-V60 | 1998 | Bovine tissue | 195 | SuTTp | III | None |

| CIT-F102 | 1998 | White pudding | 195 | STp | V | IV |

| CIT-F106 | 1998 | Raw poultry | 195 | SuTp | VI | IV |

| CIT-H11 | 1997 | Human | 195 | ASSuT | VII | None |

| CIT-F42 | 1998 | Swine | 204a | ASSuT | XI | None |

| CIT-F46 | 1998 | Swine | 204a | ASSuT | VIII | None |

| CIT-V58 | 1998 | Porcine feces | 208 | T | III | None |

| CIT-V75 | 1998 | Porcine feces | 208 | T | III | IV |

| CIT-V76 | 1998 | Porcine feces | 208 | T | III | IV |

| CIT-V37 | 1998 | Unknown | PT U302 | ACSSuTTp | I | I |

| CIT-F105 | 1998 | Raw poultry | NT | SuTp | IX | VI |

| CIT-F40 | 1998 | Swine | NT | Sensitive | X | V |

| E. coli K12/R100.1e | Unknown | nd | nd | nd | A | |

| E. coli K12/R751e | Unknown | nd | nd | nd | B |

Isolates of human origin were from Cork University Hospital; isolates of veterinary origin were from the Regional Veterinary Laboratory; isolates of food origin were from the Cork County Council Food Laboratory.

NT, not phage typeable; nd, not determined or the relevant information was not available.

None, no gene cassette amplicon was detected.

R type, drugs to which isolates were resistant. A, ampicillin; C, chloramphenicol; K, kanamycin; N, nalidixic acid; S, streptomycin; Su, Sulfonomide Duplex; T, tetracycline; Tp, trimethoprim.

Control strain, kindly provided by D. Sandvang (21).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility to antimicrobial agents was determined by the disk diffusion assay on Mueller-Hinton agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) with commercial antimicrobial susceptibility disks (Oxoid) according to the recommendations of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (30). The antibiotics tested and corresponding concentrations were as follows: ampicillin, 10 μg/disk; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/disk; ciprofloxacin, 5 μg/disk; kanamycin, 30 μg/disk; nalidixic acid, 30 μg/disk; streptomycin, 10 μg/disk; spectinomycin, 5 μg/disk; sulfonamide, 300 μg/disk; tetracycline, 10 μg/disk; trimethoprim, 5 μg/disk.

Phage typing.

Phage typing was performed in accordance with the methods of the Public Health Laboratory Service, Collindale, London, United Kingdom (2). Briefly, 4 ml of double-strength nutrient broth (Difco, Dublin, Ireland) was inoculated with a single colony of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium and incubated at 37°C for 1 h 15 min. By means of a sterile Pasteur pipette 2 ml of the broth culture was then used to flood a dried double-strength nutrient agar plate (30-ml volume of agar, dried for 1 h 30 min), and the excess broth was removed. After surface drying for 15 min, a series of typing phages were applied to the plate surface according to a defined template using a multipoint inoculator. Each plate was incubated overnight at 37°C, and the pattern of lysis produced by the phages was recorded and interpreted by comparison to standard charts.

Genomic DNA isolation.

Bacterial cells were grown in 5 ml of tryptone soy broth overnight at 37°C, and the DNA was extracted as previously described by Daly et al. (9).

5′ CS- and 3′ CS-targeted gene cassette amplification.

The S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates were also investigated for the presence of integrons. A primer set previously designed to anneal to the 5′ conserved sequence (CS) and 3′ CS flanking regions containing the integrated gene cassette were used (5, 17). All PCRs were performed in 50-μl final volumes containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 25 pmol of both forward (Int 1F, 5′-GGC ATC CAA GCA GCA AG-3′) and reverse (Int 1B, 5′-AAG CAG ACT TGA CCT GA-3′) (5, 17) primers, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 500 mM KCl, 1% Triton X-100), 8 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (consisting of 1.25 mM dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Integron primers were synthesized by Eurogentec (Abingdon, United Kingdom) and subsequently purified by high-performance liquid chromatography. All amplification reactions were performed in a MiniCycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) using the following temperature profile: predenaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 5 min and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. Each amplification reaction included a negative control, which contained all reagents except target DNA. Amplified DNA products were resolved by conventional electrophoresis through horizontal 2% agarose gels at 100 V, and the results were visualized and photographed over a UV transilluminator.

DNA amplification fingerprinting (DAF).

Genome fingerprint amplification reaction conditions were similar to those described for the analysis of gene cassettes above. Briefly, 200 ng of genomic DNA and 100 pmol of the 10-mer arbitrary primer P1254 (5′-CCG CAG CCA A-3′) (15), were included in each reaction mixture. The amplification thermal profile consisted of a predenaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 40°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and results were found to be reproducible.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the partial open reading frame of the purG gene has been assigned GenBank accession no. AF151984.

RESULTS

Phage type and antimicrobial susceptibility.

Seventy-four S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates were studied. All were phage typed, with 70% belonging to the DT104 family, of which 65% were found to be DT104 (n = 48), 4% were found to be DT104b (n = 3), and 1% were found to be PT U302 (n = 1). Other phage types included DT193 (n = 9 [12%]), the next most common phage type in this collection, DT195 (n = 6, [8%]), DT204a (n = 2, [3%]), and DT208 (n = 3, [4%]). Phage types for two isolates (CIT-F40 and -F105; Table 1) could not be determined.

All of the DT104 isolates were resistant to ACSSuT, and one isolate was resistant to ACSSuT and trimethoprim (ACSSuTTp) CIT-V36; Table 1). Three DT104b isolates (CIT-F107, -F108, and -F109; Table 1) were resistant to ACSSuT and kanamycin. Similarly CIT-V37, which was phage typed as U302, was resistant to ACSSuTTp and CIT-F34 (cultured from a milk sample) was the only isolate in this collection resistant to nalidixic acid. Twenty-one of the remaining 22 isolates in the study population demonstrated differing resistance types, the most notable feature of which was the consistent sensitivity to chloramphenicol. No resistance to ciprofloxacin was detected, and only one isolate tested (CIT-F40) was sensitive to all antimicrobials.

Amplification of integrated gene cassettes by PCR.

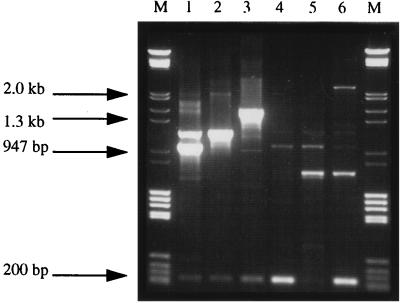

As 90% (67 of 74) of the strains were resistant to sulfonamide, a feature commonly associated with the presence of class I integrons, all isolates were analyzed for these novel (mobile) genetic elements. Use of the previously described Int 1F and Int 1B primers (5, 17) showed that strains of phage types DT104 (n = 48), DT104b (n = 3), DT193 (n = 5), DT195 (n = 2), DT208 (n = 2), and PT U302 (n = 1) and two nontypeable isolates, representing 85% (63 of 74) of the collection, contained class I integrons. The predominant amplicon pattern (denoted integron pattern IP-I; Fig. 1) detected in all DT104, DT104b, and PT U302 isolates contained three integrons. This IP-I amplicon pattern consisted of two intense DNA fragments of approximately 1.0 and 1.2 kbp as previously described (20, 21) and a weaker 210-bp fragment (Fig. 1, lane 1). Escherichia coli strains carrying plasmids R100.1 and R751 (21) were included as control strains (data not shown; Table 1). A 1.0-kbp DNA fragment, similar to that amplified in DT104 isolates, containing the ant(3”)-Ia gene was detected in the control strain carrying R100.1; this fragment corresponded to the 1.0-kb fragment of IP-I. A smaller DNA amplicon (approximately 850 bp) was detected in the control strain carrying R751 (data not shown). For the purposes of comparison these profiles were designated IP groups A and B, respectively (Table 1). However the smaller 210-bp amplicon of IP-I was absent. All remaining isolates produced five different patterns, denoted IP-II through -VI (Fig. 1, lanes 2 to 6, and Table 1). With the exception of IP-VI, all IP groups contained the small integron structure previously outlined for IP-I above. Eleven isolates did not show any evidence of a detectable gene cassette after PCR. The latter isolates displayed phage types DT193 (n = 4), DT195 (n = 4), DT204a (n = 2), and DT208 (n = 1).

FIG. 1.

Amplified gene cassettes and corresponding IP groups of representative strains of S. enterica serotype Typhimurium. After PCR 10 μl of the amplified reaction mixture was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel in 1× Tris-EDTA-acetate buffer containing 0.1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. Samples were horizontally electrophoresed at 100 V for 90 min. Lanes M, molecular weight markers, grade III (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), ranging in size from 0.56 to 21.2 kb; lane 1, CIT-F45 (DT104, IP-I); lane 2, CIT-F44 (DT193, IP-III); lane 3, CIT-F41 (DT193, IP-II); lane 4, CIT-V77 (DT193, IP-IV); lane 5, CIT-V105 (not typeable [NT] IP-VI); lane 6, CIT-F40 (NT, IP-V).

Careful inspection of Fig. 1 shows that the two large DNA fragments amplified in IP-I were also present, but with reduced intensity, in IP-II, -V, and -VI (Fig. 1, lanes 3, 6, and 5, respectively). These gene cassettes were previously reported in DT104 isolates (20, 21) and are known to contain the aminoglycoside resistance ant(3”)-Ia gene on the 1.0-kb amplicon together with pse-1 encoding β-lactamase on the 1.2-kb amplicon. The primers outlined previously by Sandvang et al. (21) were used to gel purify these amplicons from several isolates in this collection and map them by PCR. The structural arrangements of the antimicrobial resistance-encoding genes were found to be conserved in these amplicons as outlined previously (data not shown). In contrast, however, none of the previous reports (20, 21) identified the smaller 210-bp gene cassette amplicon shown in Fig. 1. This fragment appears to be unique to S. enterica serotype Typhimurium and was cloned and sequenced. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence (data not shown) identified a 178-bp open reading frame containing part of the purG gene (encoding phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthetase).

In considering the other IP groups, four additional amplicons were detected, at approximately 1.5 kbp (IP-II), 700 bp and 2.4 kbp (both IP-V), and 300 bp (IP-VI). These bands are not present as part of the DT104 pattern. As the average size of a bacterial gene is approximately 800 bp, it is possible that these larger amplicons (i.e., 1.5 and 2.4 kbp) contain two and three antimicrobial resistance determinants, respectively, within these cassettes, arranged in a “head-to-tail” configuration (6; M. Daly and S. Fanning, unpublished data). Similar structures (6) have recently been identified in S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates cultured from Albanian refugees entering Italy (27).

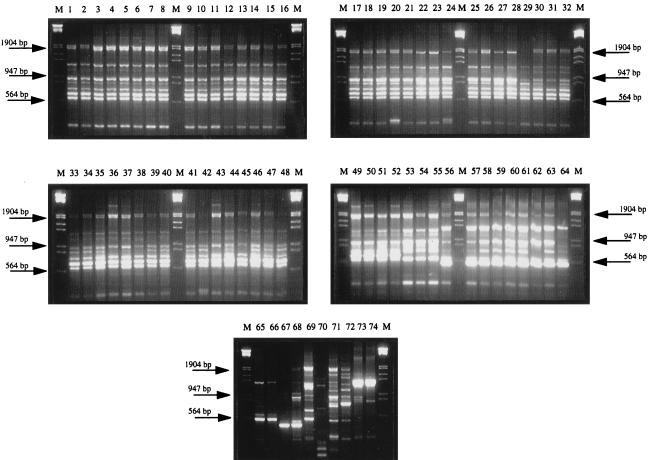

DAF analysis.

DNA fingerprint analysis using the previously characterized random 10-mer (15) was performed on purified genomic DNA from all 74 isolates. Typically, between 5 and 11 amplicons were observed after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. DNA fragments ranged in size from 300 bp to 2.0 kbp (Fig. 2). The DNA fingerprints of all isolates were grouped into 11 pattern types (DAF groups I through XI), based on a comparison of all profiles shown in the agarose gels (Fig. 2). DAF group I accounted for 70% of all isolates investigated, and this group had a typical DNA fragment pattern consisting of 10 bands (Fig. 2, lanes 1 through 52).

FIG. 2.

DAF patterns of all S. enterica serotype Typhimurium strains typed using the 10-mer primer P1254 (15). After PCR 10 μl of each reaction mixture was loaded onto a 2% agarose gel in 1× Tris-EDTA-acetate buffer containing 0.1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. Samples were electrophoresed as outlined for Fig. 1. Lanes (designated DAF groups are in parentheses [Table 1]): M (all gels), molecular weight markers, grade III (Boehringer), ranging in size from 0.56 to 21.2 kb; 1, CIT-H8 (I); 2, CIT-H23 (I); 3, CIT-F30 (I); 4, CIT-F31 (I); 5, CIT-F32 (I); 6, CIT-F33 (I); 7, CIT-F35 (I); 8, CIT-F36 (I); 9, CIT-F37 (I); 10, CIT-F39 (I); 11, CIT-F44 (I); 12, CIT-F45 (I); 13, CIT-V57 (I); 14, CIT-V59 (I); 15, CIT-V61 (I); 16, CIT-V62 (I); 17, CIT-V63 (I); 18, CIT-V64 (I); 19, CIT-V65 (I); 20, CIT-V66 (I); 21, CIT-V67 (I); 22, CIT-V68 (I); 23, CIT-V69 (I); 24, CIT-V70 (I); 25, CIT-V71 (I); 26, CIT-V72 (I); 27, CIT-V73 (I); 28, CIT-V74 (I); 29, CIT-V78 (I); 30, CIT-V80 (I); 31, CIT-V81 (I); 32, CIT-V82 (I); 33, CIT-V83 (I); 34, CIT-V84 (I); 35, CIT-V85 (I); 36, CIT-V86 (I); 37, CIT-V87 (I); 38, CIT-V89 (I); 39, CIT-V90 (I); 40, CIT-V91 (I); 41, CIT-V92 (I); 42, CIT-V93 (I); 43, CIT-V94 (I); 44, CIT-V95 (I); 45, CIT-V96 (I); 46, CIT-V100 (I); 47, CIT-F101 (I); 48, CIT-F103 (I); 49, CIT-F104 (I); 50, CIT-F107 (I); 51, CIT-F108 (I); 52, CIT-F109 (I); 53, CIT-H12 (II); 54, CIT-H16 (II); 55, CIT-F41 (I); 56, CIT-F34 (III); 57, CIT-F43 (III); 58, CIT-F47 (III); 59, CIT-V56 (III); 60, CIT-V58 (III); 61, CIT-V60 (III); 62, CIT-V75 (III); 63, CIT-V76 (III); 64, CIT-V77 (IV); 65, CIT-V79 (IV); 66, CIT-V88 (IV); 67, CIT-F102 (V); 68, CIT-F106 (V); 69, CIT-H11 (VI); 70, CIT-F46 (VII); 71, CIT-F105 (VIII); 72, CIT-F40 (IX); 73, CIT-F38 (X); 74, CIT-F42 (X).

These data suggest (Table 1) an association between DAF pattern I and IP group I for all DT104 strains. Only CIT-V38, which was phage typed as DT104, belonging to IP group I, was distinguished by a DAF pattern (DAF group XI) different from those of all other DT104 and DT104b isolates. In comparison CIT-F44, phage type DT193, had a fingerprint consistent with DAF group I and a gene cassette amplicon profile associated with IP group III. A second fingerprint group (DAF group II) consisted of three isolates (CIT-H12, -H16, and -F41; Fig. 2, lanes 53 through 55). The banding patterns observed in the last were similar to those in DAF group I, with differences represented by a single band at approximately 600 bp. The isolates in this group were typed as DT193 and DT195 (Table 1). DAF group III contained 11% (8 of 74) of the collected strains (Fig. 2, lanes 56 through 63), with all remaining isolates being grouped into eight additional categories (DAF groups IV to XI), wherein 1 to 3 amplicons were detected (Fig. 2, lanes 64 through 74).

DISCUSSION

During the 1980s S. enterica serotype Enteritidis PT4 was often reported to be the causative agent in outbreaks of salmomellosis linked to food poisoning. However, in the 1990s S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 has emerged as a new epidemic strain (20, 25). Reservoirs for the latter exist among bovine, poultry, and other animal populations from which this pathogen is transmitted to humans via the food chain. S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 is characterized by its simultaneous resistance to many antimicrobial agents, with resistance to ACSSuT common among isolates (Table 1). Acquisition of these resistance genes results from numerous independent events (20, 22).

This study investigated 74 randomly collected S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates from the Cork region of southern Ireland. The majority of these isolates (Table 1) were derived from bovines, accounting for 56% of all strains analyzed, represented by DAF group I and phage type DT104, (with the exception of two isolates, CIT-F34 [DT193] and -V60 [DT195], belonging to DAF group III]. These data suggest that S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 has been remarkably successful, relative to other phage types, in colonizing bovines in this region. The detection of indistinguishable isolates from cattle, food, and humans suggests that cattle are a significant reservoir for human infection with S. enterica serotype Typhimurium in the Cork region. In contrast, swine-derived S. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates were more heterogenous. Swine-derived isolates accounted for 29% of the total collection and, while being a smaller proportion of the study population than the bovine group, were more diverse based on their phage types, antibiograms, and DNA fingerprint patterns. Swine-derived isolates were distributed among 4 of the phage types, 8 of the 11 DAF groups, and 5 of the 6 integron groups. It is well recognized that DT193 isolates are genetically heterogenous (4). In this study, DT193 isolates cultured from porcine (n = 7), bovine (n = 1), and canine (n = 1) sources could be divided into four DNA fingerprint groups (DAF groups I to IV). A similar result was also noted recently by Baggesen and Aarestrup (3) when pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns of Danish porcine isolates were compared. All remaining isolates cultured from various animal, food, and human sources were distributed among 6 of the 11 DAF groups.

Each isolate was investigated for drug resistance and the presence of class I integrons (based on the large number of isolates resistant to sulfonamide). A conserved integron structure (IP-I; Table 1) similar to that recently reported (20, 21) was identified among all DT104 isolates, three DT104b isolates, and one PT U302 isolate. Eleven of the non-DT104 isolates in the study group did not contain an amplified gene cassette. Molecular analysis of the Penta resistance in S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 strains was previously shown to be chromosomally localized. Of particular concern in the United Kingdom is the increasing additional resistance of these isolates to nalidixic acid (14) and trimethoprim (11, 20) and their reduced susceptability to ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinone). There is evidence for a similar trend, although less marked, in Ireland (8; Cormican et al., Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.), where a significant incidence of resistance to nalidixic acid is observed. Resistance to nalidixic acid in one of our strains is a marker for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (8). While resistance to ACSSuT may be useful as a marker for DT104, further identification by molecular subtyping can provide useful information (1, 3, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 23, 28).

In conclusion, based on our data, we have identified a probable reservoir for S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 among the bovine population in the Cork region of southern Ireland. Many of these isolates were resistant to five or more antimicrobials. This observation highlights two important issues for agriculture, environmental, food, and public health authorities in Ireland. Use of antimicrobial agents in animals and humans contributes to a selective pressure favoring acquisition of multivalent antimicrobial resistance. More-limited use of antimicrobials, in particular in relation to their use for growth promotion and routine flock- or herd-wide prophylaxis in animal husbandry may be expected to reduce the opportunities for the emergence and spread of new antimicrobial agent-resistant pathogens among animals intended for human food. Furthermore, the transmission of DT104 and other strains from the livestock reservoir to humans via the food chain, must be carefully monitored. It is essential that the epidemiology of this organism be fully elucidated. Phenotypic analysis as a “front-line” measure supported by genotyping can facilitate the directed implementation of an effective surveillance and control strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Bolton, J. Fanning, C. Wall, and H. O'Shea for their comments on the manuscript and J. Murphy for providing technical assistance. L. Ward and D. Sandvang are acknowledged for their gifts of phage and control strains.

The Cork County Council are acknowledged for financially supporting part of this study. M.D. is in receipt of a postgraduate scholarship from Cork Institute of Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarts H J, van Lith L A, Keijer J. High-resolution genotyping of Salmonella strains by AFLP. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;26:3–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson E S, Ward L R, de Saxe M J, de Sa J D. Bacteriophage typing designations of Salmonella typhimurium. J Hyg. 1977;78:297–300. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400056187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggesen D L, Aarestrup F M. Characterization of recently emerged multiple antibiotic resistant Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104 and other multiresistant phage types from Danish pig herds. Vet Rec. 1998;25:95–97. doi: 10.1136/vr.143.4.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baquar N, Threlfall E J, Rowe B, Stanley J. Phage type 193 of Salmonella typhimurium contains different chromosomal genotypes and multiple IS200 profiles. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:291–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bissonnette L, Roy P H. Characterization of In0 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid pVS1, an ancestor of integrons of multiresistant plasmids and transposons of gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1248–1257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1248-1257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briggs C E, Fratamico P M. Molecular characterization of an antibiotic resistance gene cluster of Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:846–849. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collis C M, Hall R M. Site-specific deletion and rearrangement of integron insert genes catalyzed by the integron DNA integrase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1574–1585. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1574-1585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cormican M, Butler C, Morris D, Corbett-Feeney G, Flynn J. Antibiotic resistance amongst Salmonella enterica species isolated in the Republic of Ireland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:16–118. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly M, Power E, Björkroth J, Sheehan P, Colgan M, Korkeala H, Fanning S. Molecular analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; epidemiological investigation of mastitis outbreaks in Irish dairy herds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2723–2729. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2723-2729.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fanning S, Gibbs R A. PCR in genome analysis. In: Birren B, Green E, Hieter P, Klapholz S, Myers R, editors. Genome analysis: a laboratory manual. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 249–299. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glynn M K, Bopp C, Dewitt W, Dabney P, Mokhtar M, Angulo F J. Emergence of multidrug resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerra B, Landeras E, Gonzales-Hevia M A, Mendoza C. A three way ribotyping scheme for Salmonella serotype typhimurium and its usefulness for phylogenetic and epidemiological purposes. Epidemiol Typing. 1997;46:307–313. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-4-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall R M, Brookes D E, Stokes H W. Site-specific insertion of genes into integrons: role of the 59-base element and determination of the recombination cross-over point. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1941–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heurtin-Le Corre C, Donnio P Y, Perrin M, Travert M F, Avril J L. Increasing incidence and comparison of nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates from humans and animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:266–269. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.266-269.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilton A C, Banks J G, Penn C W. Optimisation of RAPD for fingerprinting Salmonella. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;24:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Minor L. Typing of Salmonella species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;7:214–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01963091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lévesque C, Pyché L, Larose C, Roy P H. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:185–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen J E, Skov M N, Angen Ø, Threlfall E J, Bisgaard M. Genomic relationships between selected phage types of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype typhimurium defined by ribotyping, IS200 typing and PFGE. Microbiology. 1997;143:1471–1479. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recchia G D, Hall R M. Origins of the mobile gene cassettes found in integrons. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:389–394. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridley A, Threlfall E J. Molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance genes in multiresistant epidemic Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Microb Drug Res. 1998;4:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandvang D, Aarestrup F M, Jensen L B. Characterisation of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella enterica Typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmieger H, Schickmaier P. Transduction of multiple drug resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanley J, Saunders N. DNA insertion sequences and the molecular epidemiology of Salmonella and Mycobacterium. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:236–251. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-4-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stokes H W, Hall R M. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Threlfall E J, Frost J A, Ward L R, Rowe B. Epidemic in cattle and humans of Salmonella typhimurium DT104 with chromosomally integrated multiple drug resistance. Vet Rec. 1994;134:577. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.22.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Threlfall E J, Frost J A, Ward L R, Rowe B. Increasing spectrum of resistance in multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium. Lancet. 1996;347:1053–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tosini F, Visca P, Luzzi I, Dionisi A M, Pezella C, Petrucca A, Carattoli A. Class I integron-borne multiple resistance carried by IncFI and IncL/M plasmids in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3053–3058. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;24:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall P G, Morgan D, Lamden K, Griffin M, Threlfall E J, Ward L R, Rowe B. A case control study of infection with an epidemic strain of multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104 in England and Wales. Commun Dis Rep. 1994;4:R130–R135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wayne P A. Performance standards for antimicrobial disc susceptibility tests. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]