Abstract

Background:

Intimal sarcoma (InS) is an exceedingly rare neoplasm with an unfavourable prognosis, for which new potentially active treatments are under development. This is to report on the activity of anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens and pazopanib in patients with InS.

Methods.

Seventeen sarcoma reference centres in Europe, US and Japan contributed data to this retrospective analysis. Patients with MDM2-positive InS treated with anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens or pazopanib between October 2001 and January 2018 were selected. Local pathological review was performed to confirm diagnosis. Response was assessed by RECIST1.1. Recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were computed by Kaplan-Meier method.

Results:

Seventy-two patients were included (66 anthracycline-based regimens; 26 gemcitabine-based regimens; 12 pazopanib). In the anthracycline-based group, 24 (36%) patients were treated for localized disease, 42 (64%) patients for advanced disease. Real-world overall response rate (rwORR) was 38%. For patients with localized disease, the median RFS was 14.6 months. For patients with advanced disease, the median PFS was 7.7 months. No anthracycline-related cardiac toxicity was reported in patients with cardiac InS (n=26). For gemcitabine and pazopanib the rwORR was 8% and the median PFS 3.2 and 3.7 months, respectively.

Conclusions:

This retrospective series shows activity of anthracycline-based regimens in InS. Of note, anthracyclines were used in patients with cardiac InS, with no significant cardiac toxicity. The prognosis in patients with InS remains poor and new active drugs and treatment strategies are needed.

Keywords: Intimal sarcoma, systemic therapies, anthracycline, gemcitabine, pazopanib, MDM2

Precis

Anthracycline-based regimens are a potentially effective medical option in intimal sarcoma. Of note, anthracyclines were used in patients with cardiac primary, with no significant cardiac toxicity The value of gemcitabine and pazopanib was limited (though possibly exploitable as further-line therapy or in patients unfit for anthracyclines).

Introduction

Intimal sarcoma (InS) is an extremely rare, mesenchymal neoplasm originating from large blood vessels and from the heart, being one of the most common primary cardiac histologies1,2. Regarded as a high-grade tumour, it is marked by MDM2 nuclear overexpression, and amplification of the 12q12–15 region (containing CDK4 and MDM2)3. These molecular features suggest that this pathway might play a relevant role in tumour pathogenesis and that MDM2 inhibition might represent a potential treatment strategy in this disease. The outcome for InS patients is poor, with a reported median overall survival (mOS) in the range of 8–13 months4,5.

Retrospective data on the activity of systemic therapies in InS are limited and no prospective studies have been conducted 4,6–10. This lack of knowledge is increasingly important today, as new potentially active treatments are emerging.

This academic, international, collaborative effort, including 17 referral sarcoma centres in the EU, US and Japan, within the World Sarcoma Network initiative, aims to report on the activity of medical agents available for treatment of soft tissue sarcomas (STS), i.e. anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens, and pazopanib, in adult patients with InS.

Patients and methods

Patient population

We sought data regarding adult patients with InS, treated with anthracycline-based regimens, gemcitabine-based regimens or pazopanib, between October 2001 and January 2018. Both patients with localized disease treated with curative intent and with advanced disease (locally advanced not eligible for complete surgical resection, or definitive RT, or metastatic) were included. A written informed consent to the treatment was obtained as required by local regulation. Approval by the Institutional Review Board of each participating institution was required.

Study design and data collection

Data were extracted from clinical databases and confirmed through a review of patient records (Table 1 reports contributions). Only cases in which diagnosis of MDM2-positive InS was histologically reviewed and confirmed by a sarcoma pathologist at the respective institution were included. MDM2 status was determined by immunohistochemistry and/or molecular testing. Response was assessed by RECIST 1.111.

Table 1.

Intimal sarcoma cases by institution.

| Institution | Cases (n) |

|---|---|

| IRCCS Fondazione Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milano, Italy | 12 |

| Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, Villejuif, France | 9 |

| Centre Léon Bérard & Université Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, France | 7 |

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts | 7 |

| National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan | 7 |

| University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA | 5 |

| Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute-Oncology Center, Warsaw, Poland | 4 |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, USA | 4 |

| Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, Roma, Italy | 3 |

| La Timone University Hospital, Aix-Marseille Université (AMU), Marseille, France | 3 |

| The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas | 3 |

| Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands | 2 |

| S.Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy | 2 |

| N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research, Moscow, Russian Federation | 1 |

| Northwell Cancer Institute and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York, USA | 1 |

| Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands | 1 |

| Nuovo Ospedale “S.Stefano”, Prato, Italy | 1 |

| TOT= 72 |

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and frequency tabulation were used to summarize patient and tumor characteristics. Real-world overall response rate (rwORR) was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) by RECIST.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival distributions were compared using the log-rank test. In patients receiving anthracycline-based regimens and treated for localized disease with curative intent, RFS was calculated as the interval from primary treatment to the date of the first evidence of recurrence, death for any reason or the last follow-up. PFS was calculated as the interval from the start of the medical treatment to the date of progressive disease (PD), death for any reason or the last follow-up. OS was calculated as the interval from the start of treatment to the time of death for any reason or the last follow-up. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out with SAS (version 9.4) and R software (version 3.5.2).

Results

Patient population

Ninety-eight adult patients were retrospectively identified and 72 included after histological review (anthracycline-group: 66; gemcitabine-group: 26; pazopanib-group: 12). Twenty-six patients received more than one treatment. The median follow-up was 36.3 months. Table 2 summarizes population characteristics.

Table 2.

Population characteristics.

| Anthracycline-based regimens | Gemcitabine-based regimens | Pazopanib | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 66* | 26* | 12* |

| Median follow up (IQR) | 36.3 (16.6 – 58.4) months | ||

| MDM2 status | |||

| • IHC | 67 (93%) | ||

| • FISH/MPS | 44 (61%) | ||

| • Both | 39 (54%) | ||

| Median age (range) | 45 (16–81) | 42 (16–75) | 51 (34–57) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| • M | 31 (47%) | 12 (46%) | 7 (58%) |

| • F | 35 (53%) | 14 (54%) | 5 (42%) |

| Stage at the time of treatment start (%) | |||

| • Localized/locally advanced (curative intent) | 24 (36%) | 2 (8%)** | 0 |

| • Locally advanced/metastatic (palliative intent) | 42 (64%) | 24 (92%) | 12 (100%) |

| Primary site | |||

| • Pulmonary artery | 38 (58%) | 16 (62%) | 7(58%) |

| • Heart | 22 (33%) | 8 (31%) | 3 (25%) |

| Left atrium | 19 (86%) *** | 7 (88%) *** | 2 (67%) *** |

| • Other sites | 6 (9%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (17%) |

IQR: interquartile range; IHC: immunohistochemistry; FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization; MPS: massive parallel sequencing.

72 unique patients; 26 patients received more than one treatment

1 patient was treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy and died of disease; 1 patient was treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery and he it is currently disease free.

26 cardiac InS – 23 (88%) left atrium; results are referred to the overall series (72 unique patients)

Treatment response and outcome

Table 3 reports treatment details.

Table 3.

Treatment and outcome in patients treated with anthracycline-based regimens for localized disease.

| All | Adjuvant CT | Neo-adjuvant CT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT (%) | 24 | 16 (67%) | 8 (33%) |

| Surgery (%) | 22 (92%) | 16 (73%) | 6 (27%) |

| • Post-operative RT (%) | 5 (23%) | ||

| Exclusive RT (%) | 2 (8%)* | - | 2 (100%) |

| Alive and disease free > 2 years | 5 | ||

CT: chemotherapy; RT: radiation therapy

1 patient was treated with proton therapy; 1 patient received 60 Gy (30 fractions) through volumetric modulated arc therapy.

Anthracycline-based regimens

Sixty-six patients were included, 50 were evaluable for response. Sixteen patients underwent surgery before chemotherapy, and therefore were not evaluable for response (however, they were included in the calculation of RFS). Anthracyclines were used as a first-line treatment in 59 (89%) patients, as a second-line treatment in 6 (9%) and as a further line in 1 (2%). Twenty (30%) patients received anthracyclines as single agent, 39 (59%) as a combination with ifosfamide, and 7 (11%) as a combination with a different compound. Sixty-four patients (97%) completed the treatment at the time of the analysis: 15 (23%) for progressive disease, 9 (13%) for toxicity, 25 (38%) for having received a maximum cumulative dose and 17 (26%) for other reasons.

Best RECIST response was 2 (4%) CR, 17 (34%) PR, 24 (48%) stable disease (SD), and 7 (14%) PD. The rwORR was 38%.

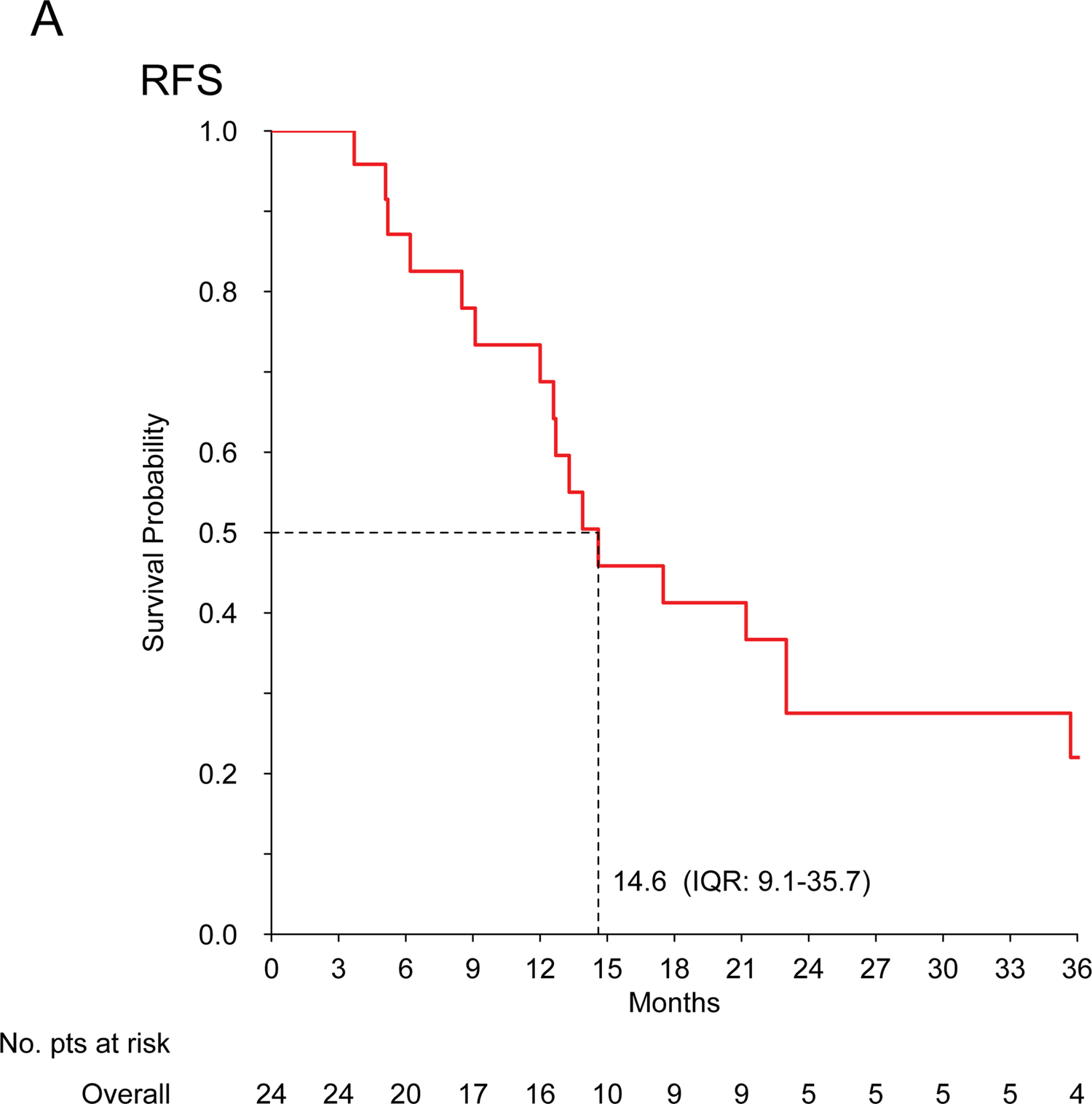

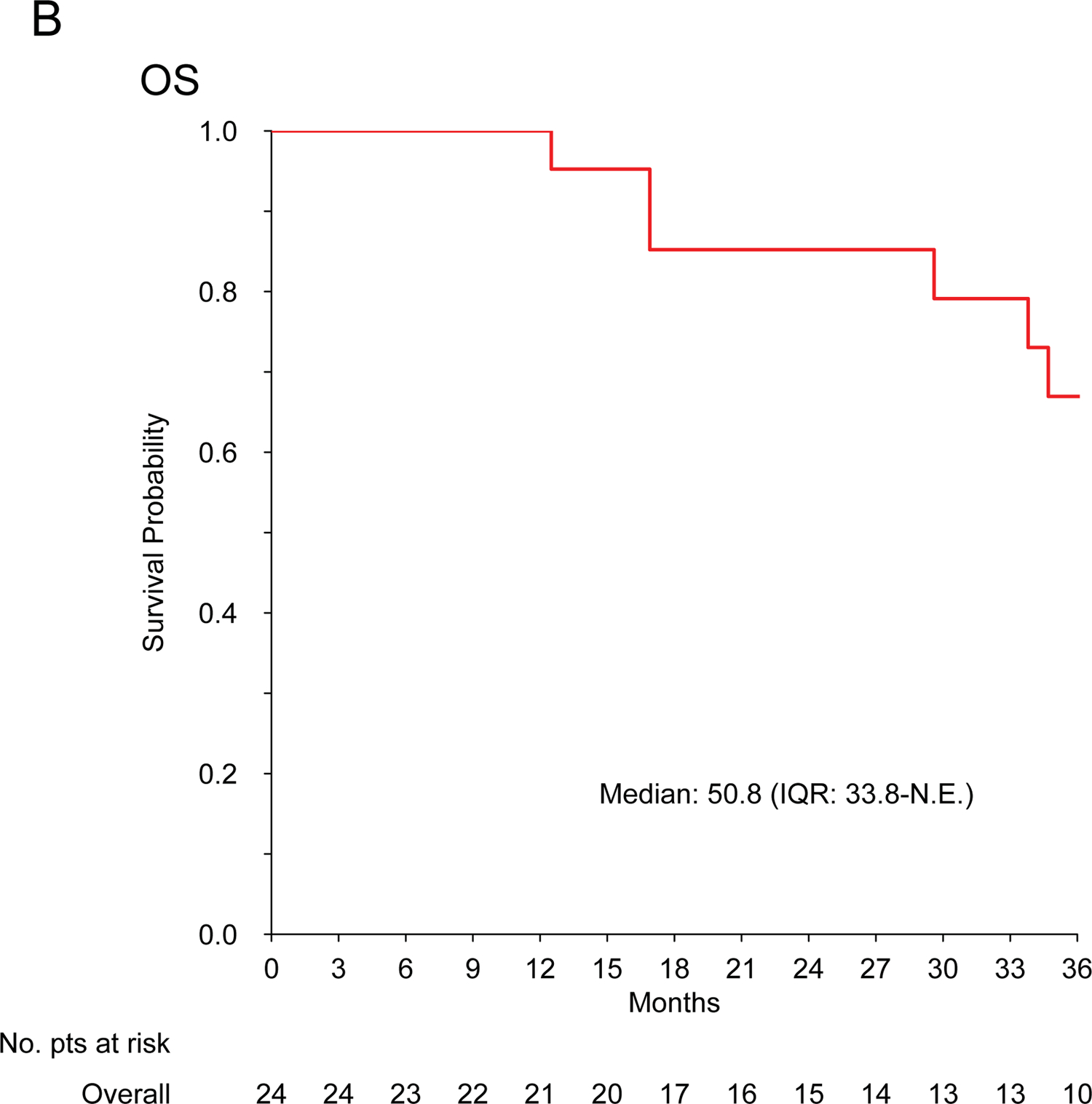

For patients with localized disease treated with curative intent (n=24), the median RFS and mOS were 14.6 (IQR: 9.1–35.7) and 50.8 (IQR: 33.8-N.E.) months, respectively. Five patients were alive and disease free at >2 years: 2 patients had chemotherapy and exclusive radiation therapy; 1 patient had chemotherapy, surgery and radiation therapy; 2 patients had chemotherapy and surgery. Table 3 describes treatment details.

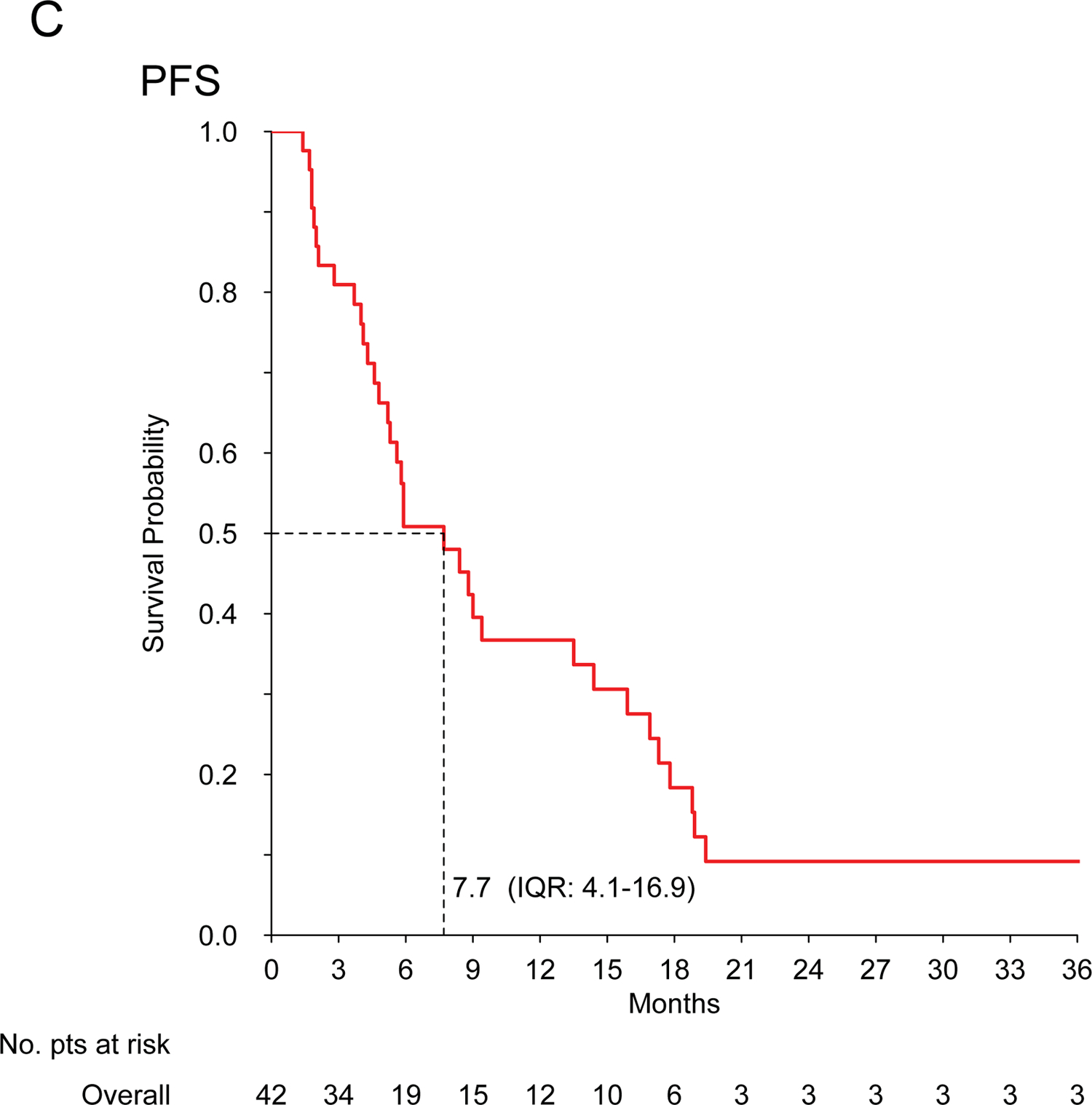

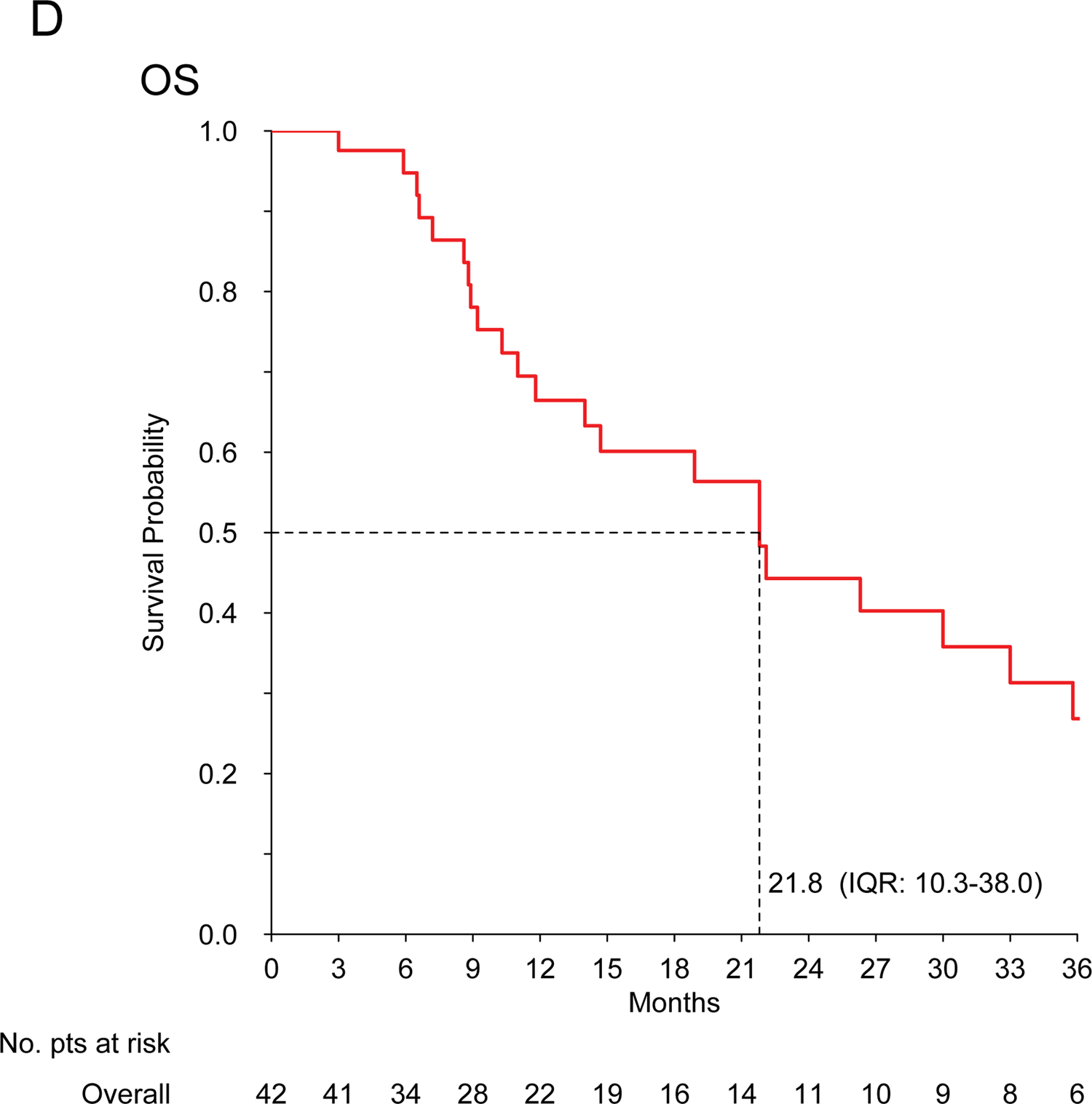

For patients with advanced disease (n=42), the median PFS (mPFS) and mOS were 7.7 (IQR: 4.1–16.9) and 21.8 (IQR: 10.3–38) months, respectively. The median PFS in responding patients was 9 months, compared to 5 months in non-responding patients (P=0.02). Two patients are alive and disease free at more than 2 years (one patient metastatic to the lung had chemotherapy with complete response and exclusive radiation therapy on the primary; one patient metastatic to the lung underwent lung metastasectomy, chemotherapy and exclusive radiation therapy on the primary).

No cardiac toxicity was observed in patients with cardiac InS (n=26). Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier curves.

Figure 1. Intimal sarcoma patients treated with anthracycline-based regimens.

Kaplan-Meier curves for recurrence-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in patients treated for localized disease with curative intent (n=24); progression-free survival (C) and overall survival (D) in patients treated for advanced disease with palliative intent (n=42).

Gemcitabine-based regimens

Twenty-six patients were included, 25 evaluable for response (one had surgery prior to chemotherapy). Gemcitabine-based regimens were used as a first-line treatment in 6 (23%) patients and as a second-line treatment in 20 (77%). Seven (27%) patients received gemcitabine as single agent, 16 (62%) as a combination with docetaxel, and 3 (11%) as a combination with a different compound. All patients completed the treatment at the time of the analysis: 20 (77%) for progressive disease, 2 (8%) for toxicity and 4 (15%) for other reasons.

Best RECIST response with gemcitabine-based regimens was 2 (8%) PR, 7 (28%) SD and 16 (64%) PD. rwORR was 8%.

For patients with advanced disease (n=24), the mPFS and mOS were 3.2 (IQR: 2.1–7.1) and 13.1 (IQR: 7.6–16.5) months, respectively.

Pazopanib

Twelve metastatic patients were included, all evaluable for response. Pazopanib was used as a first-line treatment in 1 (8%) patient, as a second-line treatment in 3 (25%) and as a further line in 8 (67%). All patients completed the treatment at the time of the analysis: 11 (92%) for progressive disease and 1 (8%) for toxicity.

Best RECIST response with pazopanib was 1 (8%) PR, 4 (34%) SD, and 7 (58%) PD. The rwORR was 8%. The mPFS and mOS were 3.7 (IQR: 2.6–4.6) and 12.1 (IQR: 4.1–18.9) months, respectively.

Discussion

This academic, multi-institutional, international, retrospective study collected the largest series currently available of adult patients affected by MDM2-positive InS treated with systemic therapy. Seventy-two patients (66, anthracycline-group; 26, gemcitabine-group; 12, pazopanib-group) were included. Anthracycline-based regimens showed a degree of activity towards the higher limits observed in STS (rwORR 38%, mPFS 7.7 months), whereas gemcitabine and pazopanib had a limited antitumor effect (rwORR: 8%, mPFS 3.2 and 3.7 months, respectively), though they were mainly used in advanced disease and further lines.

InS is extremely rare, mostly diagnosed in adult patients and often arising from critical anatomic sites, thus being an often life-threatening tumour even when localized. In this series, pulmonary artery was the most common primary site (56%), followed by heart (36%). Notably, 23/26 (88%) cardiac InS originated from the left atrium. Pathology review in sarcoma reference centres led to the exclusion of approximately 25% of the cases diagnosed in the community.

The previous data available are confined to case reports and small retrospective series, not always reporting MDM2 status, and suggest a poor activity of chemotherapy in InS, with few anecdotal responses observed4,6,8. In our series, including only confirmed MDM2-positive cases, InS showed sensitivity to anthracycline-based regimens, possibly greater than expected in other STS and to what has been reported previously by Van Dievel and Penel, who observed no responses over 5 InS patients each4,8,12. Given InS challenging sites of origin, tumor shrinkage may be crucial both in the localized and advanced stages, as it may facilitate local treatment (surgery and/or radiation therapy), control symptoms and improve patient’s quality of life. Unfortunately, mPFS for advanced disease was only 7.7 months. This unfavourable prognosis is consistent with previous findings4,8,13. Prognosis was also unsatisfactory in patients with localized disease, treated with anthracycline-based regimens plus an intended definitive local treatment, with a14.6-month mRFS. However, it is worth noting that around 25% of patients with localized disease are expected to be alive and disease-free at >2 years. This suggest a possible role for (neo)adjuvant treatment in InS patients, although this series did not establish a comparison estimate of RFS for patients without chemotherapy, and a randomized study would be exceedingly difficult to accrue for this rare sarcoma subtype.

With a median follow up of 36 months, no cardiac complications were observed following treatment with anthracyclines in this series. No data are available on long-term toxicity and, due to the retrospective nature of the study, asymptomatic cardiac toxicity could have been missed. However, though expected cardiac risk must be assessed individually, this observation in a significant number of patients may contribute to clinical decision-making.

In contrast to angiosarcoma, another vascular sarcoma potentially arising from the heart, a low rwORR (8%) and a limited m-PFS (3.2 months) were observed with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy14. Similarly, the activity of pazopanib, previously suggested by Kollar (2 RECIST PR/2 patients) and by Funatsu (1 PR /1 patient), was limited (rwORR: 8%, m-PFS 3.7 months)6,7. Of note, if anthracyclines were mostly used upfront, gemcitabine and pazopanib were mainly used as further lines.

In conclusion, our results show that anthracycline-based regimens are a potentially effective medical option in InS. The value of gemcitabine and pazopanib was limited (though possibly exploitable as further-line therapy or in patients unfit for anthracyclines). The prognosis of InS patients remains poor, and new medical options are needed both in the localized and in the metastatic stages. MDM2 inhibitors are emerging as a promising venue in InS, requiring prospective studies. This series may be used as a benchmark for such future trials.

Funding statement

JYB: NetSARC (INCA & DGOS) and RREPS (INCA & DGOS), RESOS (INCA & DGOS) and LYRICAN (INCA-DGOS-INSERM 12563, InterSARC (INCA), LabEx DEvweCAN (ANR-10-LABX-0061), EURACAN (EC 739521) funded this study.

RF received support from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Core Grant No. P30 CA008748.

MG received research support and honoraria from Epizyme, Bayer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Karyopharm and Springwork Therapeutics; support from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Core Grant No. P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

AMF received institutional clinical trials support from Amgen Dompé, AROG Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar and travel grants from PharmaMar.

BV received consultancy and advisory honoraria from Bayer, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar, Abbott; honoraria from Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar, Abbott; institutional research funding from Eli Lilly, Novartis and PharmaMar.

GGB received travel grants and advisory honoraria from Pharmamar and Eli Lilly, advisory honoraria from Eisai.

RGM received consulting fees and institutional clinical trials support from Lilly, Novartis, Roche and Glaxo Smith Kline.

JYB received research support and honoraria from Novartis, Bayer, GSK, Pharmamar.

AG received advisory honoraria from Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Nectar Therapeutics; speaker’s honoraria from Eisai, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, PharmaMar; research support from Amgen Dompé, AROG Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar.

ALC received honoraria from Pharmamar, Lilly, Amgen, Pfizer.

OM received consultancy honoraria from Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Incyte, Ipsen, Lundbeck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Vifor Pharma; board membership from Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol Myers-Squibb, Eli-Lilly, Lundbeck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Vifor Pharma; speakers bureau from Eli-Lilly, Roche, Servier; stock ownership for Amplitude surgical, Transgene.

SS received research support from Adaptimmune, Amgen, Glaxo Smith Kline, Karyopharm, Lilly; honorarium from NanoCarrier.

JH received consultancy honoraria from Eli Lilly and Epizyme.

AJW has reported consulting roles for Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Five Prime Therapeutics, Nanosphere; received honoraria from Novartis and institutional research support from Daiichi-Sankyo, Plexxikon, Eli Lilly, Aadi Bioscience, Five Prime Therapeutics, Karyopharm

PGC has reported advisory roles for Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Nektar Therapeutics, speaker’s honoraria from Eisai, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, PharmaMar, and conducted studies sponsored by Amgen Dompé, AROG Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar.

KT hase served on an advisory board for Agios.

SSt has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, PharmaMar, Takeda; institutional research grants from Amgen Dompé, Advenchen, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo Pharma, Epizyme Inc., Novartis, Pfizer and PharmaMar; travel grants from PharmaMar and has reported advisory/consultant roles for Bayer, Daiichi, Eli Lilly, Epizyme, Karyopharm, ImmuneDesign, Maxivax and PharmaMar

TA, SLV, EBA, AD, KY, EN, BS, PT, FD, VR, HG, MP, ID, AF, RLJ, RGB, AK, JA, MB, AMC, MS, AM, LM have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDMBJ, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone; Lyon, FR, IARC. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuville A, Collin F, Bruneval P, et al. Intimal sarcoma is the most frequent primary cardiac sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular retrospective analysis of 100 primary cardiac sarcomas. The American journal of surgical pathology. Apr 2014;38(4):461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bode-Lesniewska B, Zhao J, Speel EJ, et al. Gains of 12q13–14 and overexpression of mdm2 are frequent findings in intimal sarcomas of the pulmonary artery. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. Jan 2001;438(1):57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Dievel J, Sciot R, Delcroix M, et al. Single-Center Experience with Intimal Sarcoma, an Ultra-Orphan, Commonly Fatal Mesenchymal Malignancy. Oncology research and treatment. 2017;40(6):353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato W, Usui A, Oshima H, Suzuki C, Kato K, Ueda Y. Primary aortic intimal sarcoma. General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. May 2008;56(5):236–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funatsu Y, Hirayama M, Shiraishi J, et al. Intimal Sarcoma of the Pulmonary Artery Treated with Pazopanib. Internal medicine. 2016;55(16):2197–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kollar A, Jones RL, Stacchiotti S, et al. Pazopanib in advanced vascular sarcomas: an EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG) retrospective analysis. Acta oncologica. Jan 2017;56(1):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penel N, Taieb S, Ceugnart L, et al. Report of eight recent cases of locally advanced primary pulmonary artery sarcomas: failure of Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. Aug 2008;3(8):907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong HH, Gounaris I, McCormack A, et al. Presentation and management of pulmonary artery sarcoma. Clinical sarcoma research. 2015;5(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantaloube M, Moureau-Zabotto L, Mescam L, et al. Metastatic Intimal Sarcoma of the Pulmonary Artery Sensitive to Carboplatin-Vinorelbine Chemotherapy: Case Report and Literature Review. Case reports in oncology. Jan-Apr 2018;11(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). European journal of cancer. Jan 2009;45(2):228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Judson I, Verweij J, Gelderblom H, et al. Doxorubicin alone versus intensified doxorubicin plus ifosfamide for first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. Apr 2014;15(4):415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Secondino S, Grazioli V, Valentino F, et al. Multimodal Approach of Pulmonary Artery Intimal Sarcoma: A Single-Institution Experience. Sarcoma. 2017;2017:7941432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stacchiotti S, Palassini E, Sanfilippo R, et al. Gemcitabine in advanced angiosarcoma: a retrospective case series analysis from the Italian Rare Cancer Network. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. Feb 2012;23(2):501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]