Abstract

Background

Many models have been developed to predict severe outcomes from Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). These models are usually developed at a single institution and largely are not externally validated. Our aim in this study was to validate previously published risk scores in a multicenter cohort of patients with CDI.

Methods

This was a retrospective study on 4 inpatient cohorts with CDI from 3 distinct sites: the universities of Michigan (2010–2012 and 2016), Chicago (2012), and Wisconsin (2012). The primary composite outcome was admission to an intensive care unit, colectomy, and/or death attributed to CDI within 30 days of positive testing. Both within each cohort and combined across all cohorts, published CDI severity scores were assessed and compared to each other and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guideline definitions of severe and fulminant CDI.

Results

A total of 3646 patients were included for analysis. Including the 2 IDSA guideline definitions, 14 scores were assessed. Performance of scores varied within each cohort and in the combined set (mean area under the receiver operator characteristic curve [AuROC], 0.61; range, 0.53–0.66). Only half of the scores had performance at or better than IDSA severe and fulminant definitions (AuROCs of 0.64 and 0.63, respectively). Most of the scoring systems had more false than true positives in the combined set (mean, 81.5%; range, 0%–91.5%).

Conclusions

No published CDI severity score showed stable, good predictive ability for adverse outcomes across multiple cohorts/institutions or in a combined multicenter cohort.

Keywords: CDI, severe Clostridioides difficile infection, toxic megacolon

Upon validating and comparing 14 severe CDI scoring systems using 3646 patients from 4 cohorts across 3 sites, no scoring system had reproducible, high, or accurate predictive ability for adverse outcomes.

Clostridioides difficile is a gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus that is the cause of C. difficile infection (CDI), which presents with a spectrum from mild diarrhea to severe colitis. CDI can lead to complications that include ileus, toxic megacolon, severe sepsis, or death [1]. In the healthcare setting, it is a frequent cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea with an infection-related mortality of 5%, and it quadruples the cost of acute care hospitalization [2, 3]. Of additional concern is that the incidence of CDI has increased since the emergence of the NAP1 strain in early 2000 [4, 5].

Despite improvements in detection and treatment and despite the availability of effective therapy, it is difficult to predict the clinical course for an individual patient. Should an accurate method of prediction be available, more aggressive treatments such as advancing antimicrobial therapy or using surgical interventions such as loop-ileostomy can be better allocated to only those patients who need them, which could mitigate or reduce negative outcomes.

Numerous scores have been developed to identify patients at a higher risk for mortality or a complicated CDI course [6-25]. Of the published scores, many were developed at a single institution, were trained on a small number of patients, and/or were not externally validated. Previous attempts to externally validate a select number of these scores in single center cohorts show them to have low overall predictive ability [26-28]. In this study, we assess the performance of multiple severe C. difficile predictive scoring systems on a large, multicenter, geographically dispersed cohort within the United States.

METHODS

Study Selection

Initial evaluation for potential scoring systems started with studies that had been assessed in prior published reviews [26-29] and published scoring systems [6, 11, 13-19, 21, 23-25]. Studies were selected that had developed a predictive scoring system for at least 1 of the following outcomes of CDI: severe course, complications, or mortality. For scoring systems that had nonquantifiable parameters, such as altered mental status or abdominal pain, scores were modified to exclude them from the model. Missing values of the parameters were set to zero in calculation of the score if the parameters were included. This was done to simulate real-world situations where all of the data may not be known and the scores would be used with the data that were available.

Patient Cohorts

We included hospitalized patients aged >18 years diagnosed with CDI at the following academic medical centers: University of Michigan (2010–2012 and 2016), University of Wisconsin (2014–2015), and University of Chicago (2013–2015). CDI diagnosis was defined as the presence of diarrhea (ie, ≥3 stools per 24 hours) in combination with positive C. difficile laboratory testing. Site-specific diagnostic testing algorithms and tests used can be found in the Supplementary Materials. All cases of CDI diagnosed in inpatients were included; patients diagnosed in the outpatient setting were excluded. Medical charts were reviewed for demographic and clinical characteristics. All clinical data were collected within 48 hours of CDI diagnosis taking the most extreme values if multiple results present, with baseline data 48 hours prior to diagnosis.

Outcomes

We defined the severe CDI outcome as true if any of the following criteria were met within 30 days of diagnosis and determined to be attributable to CDI by the study team physicians: transfer or admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), colectomy, and/or death.

Data Analyses

We used R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for cleaning data, constructing scoring variables and calculating scores, and computing predictions for each score. If a patient had missing data that were required for a score, that variable was excluded from the score for that patient. We assessed the performance of scores using standard diagnostic test characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values), as well as positive and negative likelihood ratios, area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AuROCs), and precision-recall curves. The scores were compared to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) severity score using net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination index improvement (IDI), and the scores were subsequently compared to each other using NRI/IDI. For continuous scores, cutoffs were set at the level that maximized the AuROC for our binomial, composite outcome, and these were then used to calculate the above metrics that relied on discrete cut-points. The following packages were used for these tasks: dplyr [30], predictABEL [31], PRROC [32], pROC [33], rmda [34], stringr [35], and precrec [36].

RESULTS

A total of 3646 patients from 4 cohorts at 3 sites were used in analyzing the various predictive scores. Approximately 50% of the total patients came from the University of Michigan, with two-thirds of these from the 2010–2012 cohort (Table 1). The University of Michigan 2010–2012 cohort had the most severe CDI outcomes by both number and percentage of total. Regarding severe outcomes, the University of Chicago had the highest 30-day mortality and colectomy by percentage and the University of Wisconsin had the highest ICU transfer by percentage. However, in considering the outcomes attributable to CDI, the University of Michigan had the highest mortality percentage, the University of Wisconsin had the highest ICU transfer by percentage, and the University of Chicago had the highest colectomy by percentage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Multicenter Cohort Population

| Variable | University of Michigan (2010–2012) | University of Michigan (2016) | University of Wisconsin (2014–2015) | University of Chicago (2013–2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 1144 | 646 | 515 | 1341 |

| Age (years) [mean ± SD] | 57.3 ± 18.0 | 57.7 ± 18.2 | 59.3 ± 16.1 | 58.7 ± 18.5 |

| Severe Clostridioides difficile [n (%)] | 90 (7.9%) | 29 (4.5%) | 35 (6.8%) | 64 (5.8%) |

| Male [n (%)] | 519 (45.3%) | 330 (47.6%) | 251 (48.7%) | 639 (47.8%) |

| WBC (x103cells/µL) [mean ± SD] | 13.4 ± 12.4 | 12.2 ± 15.5 | 12.7 ± 19.5 | 11.2 ± 11.9 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dL) [mean±SD] | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 1.6 ± 2.2 |

| Peak creatinine (mg/dL) [mean±SD] | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 2.4 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| 30 day mortality [n (%)] | 89 (7.8%) | 41 (6.3%) | 45 (8.7%) | 117 (8.7%) |

| ICU transfer [n (%)] | 114 (10.0%) | 11 (1.7%) | 61 (11.8%) | 84 (6.3%) |

| Colectomy [n (%)] | 6 (0.5%) | 3 (0.5%) | 6 (1.2%) | 21 (1.6%) |

| Attributable outcomes | ||||

| 30 day mortality [n (%)] | 49 (4.3%) | 23 (3.6%) | 17 (3.3%) | 39 (2.9%) |

| ICU transfer [n (%)] | 49 (4.3%) | 5 (0.8%) | 26 (5.0%) | 18 (1.3%) |

| Colectomy [n (%)] | 4 (0.3%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (1%) | 16 (1.2%) |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation.

A total of 14 predictive scores were chosen for analysis (see Supplementary Materials). The scores that were chosen were both dichotomous (ie, the output was binomial, such as true/false) and continuous (ie, the output consisted of a numerical scale, from a low value to a high value, with one end of the scale more associated with the chosen outcome). Overall, the scores performed variably within each cohort with a mean AuROC of 0.63 (range, 0.49–0.75; Table 2). The scores had the best predictive metrics with the 2016 University of Michigan cohort and the worst predictive metrics with the 2010–2012 University of Michigan cohort: this is illustrated by the IDSA Fulminant score with an AuROC of 0.64 (Michigan, 2010–2012) vs AuROC of 0.75 (Michigan, 2016; Table 2). The McEllistrem score was not run on the University of Wisconsin cohort as they lacked imaging data, and this would have forced the score to rely on white blood cell count (WBC) alone.

Table 2.

Performance Measures of the CDI Severity Scoring Systems Across Cohorts vs. the Primary Composite Outcomea

| University of Michigan (2010-2012) | University of Michigan (2016) | University of Wisconsin | University of Chicago | Combined Sites Data Set | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sen | Spec | AUC | PR AUC | NRIb | Sen | Spec | AUC | PR AUC | NRIb | Sen | Spec | AUC | PR AUC | NRIb | Sen | Spec | AUC | PR AUC | NRIb | Sen | Spec | AUC | PR AUC | NRIb | |

| IDSA [25] | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.66 | d | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.61 | d | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.69 | d | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.71 | d | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.68 | d |

| IDSA Fulminant [25] | 0.59 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.61 | –0.01 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 0.61 | –0.15 | 0.44 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.61 | –0.04 |

| McEllistrem [24] | 0.24 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 0.54 | –0.03 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 0.54 | 0.47 | –0.29 | … | … | … | … | … | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.47 | –0.15 | 0.13 | 0.94 | 0.54 | 0.50 | –0.21 |

| Belmares [6] | 0.51 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.59 | –0.03 | 0.50 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.52 | –0.06 | 0.08 | 0.98 | 0.53 | 0.52 | –0.10 | 0.37 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.57 | –0.05 |

| Zar [17] | 0.52 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.62 | –0.01 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.04 |

| Gujja [11] | 0.12 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.52 | –0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 | … | 0.32 | –0.38 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.46 | –0.20 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.46 | –0.15 | 0.08 | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.47 | –0.22 |

| Lungulescu [15] | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.60 | –0.01 | 0.56 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 0.60 | –0.01 |

| Na [18] | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 0.56 | –0.13 | 0.34 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.56 | –0.02 | 0.40 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.57 | –0.03 |

| Jardin [13] | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.64 | –0.03 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.66 | –0.27 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.04 |

| Welfare [21]c | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.61 | 0.81 | –0.13 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.79 | –0.13 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.70 | –0.38 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.70 | –0.04 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.67 | –0.13 |

| Kassam [23]c | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.68 | –0.07 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.41 | –0.05 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.63 | –0.20 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.63 | –0.03 | 0.49 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.66 | –0.08 |

| Toro [19]c | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.16 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0 |

| Miller [16]c | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.06 |

| Kulaylat [14] | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.69 | –0.13 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.71 | –0.23 | 0.40 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.60 | –0.18 | 0.17 | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.60 | –0.17 | 0.41 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.65 | –0.16 |

IDSA model: Defined as diagnosis of Clostridioides difficile and white blood cells >15 000 cells/µL and/or 1.5-fold increase of serum creatinine from baseline.

IDSA severe model: Defined as diagnosis of Clostridioides difficile and hypotension as defined as systolic blood pressure <90, ileus or toxic megacolon by imaging.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operator curve; NRI, net reclassification improvement; PR AUC, precision-recall area under the receiver operator curve; Sen, sensitivity; Spec, specificity.

aAttributable 30-day ICU admission, colectomy, and/or death).

bNet reclassification improvement is equal to integrated discrimination index for binary models.

cContinuous models were converted to binary models using net reclassification improvement to maximize sensitivity and specificity within cohorts. Different cut-off values were determined depending on cohort.

dIDSA non-severe model as comparator for net reclassification calculations.

The continuous scores (Welfare, Kassam, Toro, and Miller) showed better metrics across all cohorts (Table 2). The predictions from the Toro and Miller scoring systems had the best of the metrics across all cohorts by AuROC, precision-recall area under the receiver operator curve, and net reclassification improvement. For dichotomous scores, the net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination index were equal. Given the rarity of severe CDI outcomes, all scores showed high negative predictive values, but the Toro and Miller scores had higher positive predictive values compared with the other scores.

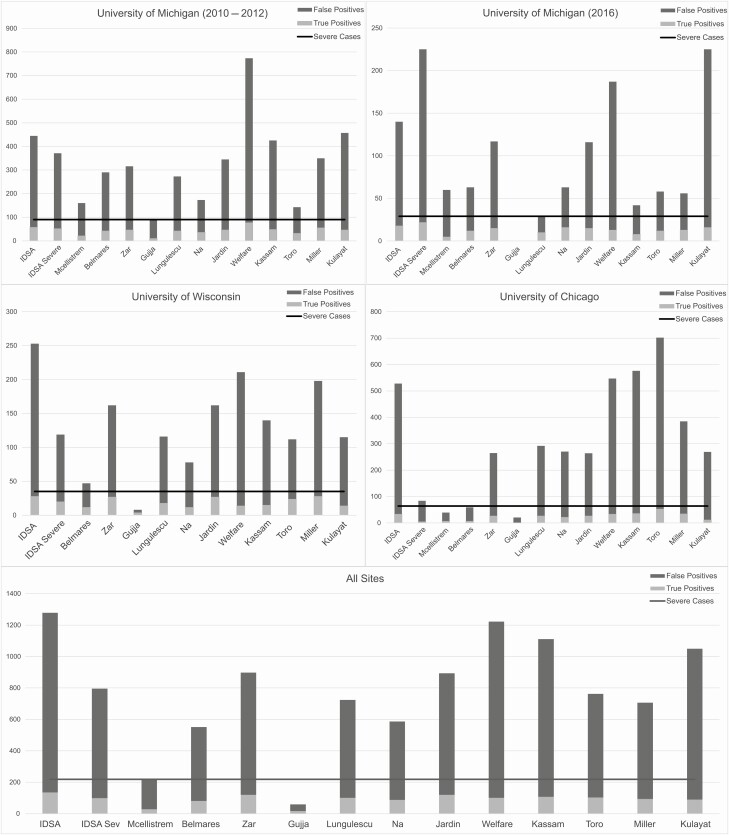

As can be seen in Figure 1, many of the scoring systems overcall severe CDI outcomes, resulting in a greater proportion of false positives vs true positives. Some of these predictive models can accurately identify most of the true-positive severe cases, but this comes at a cost of identifying many false positives (combined set mean 81.5% false positive; range, 0%–91.5%). Some predictive models had such low sensitivity for detection of severe cases that they did not even approach the actual number of severe cases found within a cohort. This is illustrated by the Gujja score in all cohorts, most notably in the Michigan 2016 cohort, which had no severe cases detected (actual severe cases, 29) and by the McEllistrem score in the University of Chicago cohort, which had 39 severe cases detected (actual severe cases, 64).

Figure 1.

Performance of predictive models across cohorts. Abbreviation: IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America.

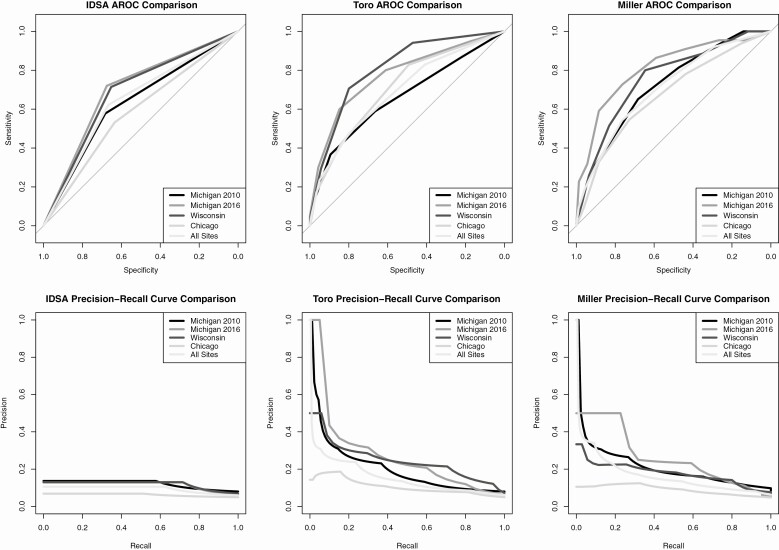

Figure 2 shows the IDSA, Toro, and Miller scores as compared by AuROC and precision-recall curve. Values for the areas under these curves are in Table 2. The IDSA score showed relative similarity across AuROCs (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.63; Michigan 2016, 0.7; Wisconsin, 0.68; Chicago, 0.58; and combined, 0.64) but performed poorly by evaluation of the precision-recall curve (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.66; Michigan 2016, 0.61; Wisconsin, 0.69; Chicago, 0.71; and combined, 0.68). The Toro score showed improved diagnostic discrimination compared with the IDSA score (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.62; Michigan 2016, 0.72; Wisconsin, 0.75; Chicago, 0.69; and combined, 0.64) but showed more variability with the precision-recall curve (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.53; Michigan 2016, 0.44; Wisconsin, 0.59; Chicago, 0.77; and combined, 0.6) with less discrimination at the University of Wisconsin and University of Chicago. The Miller model, like the Toro model, showed a lower poor precision-recall area (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.66; Michigan 2016, 0.61; Wisconsin, 0.69; Chicago, 0.71; and combined, 0.68) when compared with the AuROC (Michigan 2010–2012, 0.66; Michigan 2016, 0.61; Wisconsin, 0.69; Chicago, 0.71; and combined, 0.68).

Figure 2.

ROC and precision-recall curves of the IDSA model compared with top-performing models. Abbreviations: IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; ROC, receiver operator characteristic curve.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the largest external validations of published CDI severity scoring systems to date. Previous studies at single centers have attempted to externally validate CDI scoring systems and have found that they did not externally validate well [26-28]. Across multiple cohorts at multiple sites, no CDI severity score demonstrated sufficient ability to accurately predict severe outcomes. Many scores resulted in a large number of false positives; even the best performing models, namely, the Toro and Miller scores, showed a sharp decrease in positive predictive value as sensitivity increased, as illustrated by the precision-recall curves (Figure 2). No model yielded consistent AuROC above 70%, a commonly accepted minimal threshold to indicate that a model has acceptable performance [37]. Our study confirms previous published validation attempts but does so with more published scores and in a larger, multicenter cohort, suggesting the prior poor validation results were not due to size or the specifics of a particular healthcare center. Thus, while all of these scores, including the models used in published guidelines, can be used to classify CDI cases as severe/not severe, this classification does not reliably associate with prognosis, questioning the clinical utility of allocating treatments to patients based on these scores.

Another recent publication did similar external validation looking at CDI scoring systems using a multicenter cohort [38]. They focused primarily on 7 studies, 4 that predicted CDI complications and 3 that predicted CDI mortality. They did exclude studies that had data that were not within their cohort, 2 of which we were able to include [14, 15] and 1 due to concerns over internal validity [21]. Our study differs in several important ways. We chose to include 14 studies that had been published in peer-reviewed journals and thus could be used by any clinician if they were looking for a predictive model. Through modifications, we additionally tried to include scores even if some of the included variables were missing in our datasets, and we also used a broad, multicenter cohort of patients. We felt that because there are many published scores without even some measure of external validation, we could determine if they show promise by testing modified versions of them in a diverse cohort. Also, their reliance on AuROC alone for comparisons is not optimal given the low prevalence of the complications and mortality attributable to CDI. Use of the area under the precision-recall curve (PR AUC), as we have measured, has been shown to better summarize the performance in testing models of rare outcomes [39]. Several tests did show a modest fit to the data with AuROC but showed less fidelity with PR AUC, so the prediction of the scores may be overestimated. Nevertheless, our results are comparable overall with the prior study [38] as we also found the score performance to be poor across all metrics

For example, using a score with a sensitivity of 60% and a false-positive rate of 81% in a healthcare center that treats 500 patients with CDI over the course of a year with a severe CDI case risk of 5%, one would falsely identify nearly 80 people as being at increased risk of severe CDI. However, with a more sensitive score that could predict 70% of those at increased risk of severe CDI but with a false-positive rate of at most 30%, one would identify 25 people at risk and only falsely identify 7 individuals with the same cohort.

There are multiple avenues one could take to try to improve predictions. One method leverages new modeling approaches with “big data” sources, namely, machine-learning models that use features drawn from the entire electronic medical record to identify patients who are likely to develop a severe CDI outcome [40]. There is also a need for early markers of a severe course to identify the cases as soon as possible when interventions still have a chance to improve outcomes. Since currently available biomarkers, such as WBC, perform inadequately at this task, novel, experimental biomarkers should be explored in developing new scores, as they may improve predictions and can rise early in the disease process [41, 42].

Another avenue for improving the predictive ability of scores arises from the fact that reproducibility is critical. None of the published scores studied showed reproducibility at all sites and, in some cases, could not be used within a certain patient cohort due to data availability. As stated before, many of these models were single center–derived, limiting their external validity. Future models should be multicenter-derived, spread geographically to fully encompass the diversity in general population-level differences (eg, community vs academic health centers), diagnostic and treatment practices, and regional variation in molecular epidemiology so that these important differences are captured and incorporated into predictions.

Improving the quality, reliability, and depth of information about patient characteristics and outcomes can also improve model performance. Many of the published scores studied were developed as part of retrospective studies, limiting data reliability, data integrity, and completeness of patient follow-up information—all problems that could be addressed with a prospective cohort. Furthermore, development of a prospective cohort enables the collection of data about “soft outcomes” that are clinically relevant but difficult to ascertain retrospectively. An example is resolution of diarrhea/clinical cure, which is readily available from randomized, controlled trials, such as the bezlotoxumab and fidaxomicin trials, but difficult to obtain retrospectively through chart review [43, 44]

An accurate and validated model for severe CDI outcomes that uses information available to the clinician at the time of diagnosis or early during the disease course could better enable not only optimal clinical care but also positively impact clinical research. Developing a model to predict the rare outcome of severe CDI is difficult and thus requires a large cohort to achieve sufficient statistical power for trials aimed at reducing this rare outcome, limiting the ability of such trials to occur. If an accurate model for these outcomes existed, we could enrich for patients who are more likely to have this outcome, thus enabling a study with fewer patients; otherwise, it may not be feasible. For example, in the setting of complicated or fulminant disease, characterized by the development of hypotension/shock, ileus, or megacolon, interventions are typically only used once this outcome has already started to occur. These interventions can include pharmacologic measures (advancing oral vancomycin therapy to a higher dose, starting intravenous metronidazole, and adding rectal vancomycin when ileus is present), consultation with the infectious diseases or surgical specialists, and earlier consideration for more experimental procedures such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [45, 46]. In contrast, a study that uses an accurate predictive model to select a patient cohort enriched for those at highest risk for the typically rare but serious outcome of fulminant CDI could determine if progression to fulminant CDI could be prevented when such patients are identified and treated early with pharmacologic measures, early consultation with specialists, or with FMT.

The results from this study are not without issues. The 2010–2012 University of Michigan cohort was earlier than the other 3, and there are likely some patients who were treated with metronidazole instead of vancomycin, as the updated IDSA guidelines were published in 2016. Various other diagnostic and therapeutic trends may have also changed; however, this is mitigated since we validated within and across cohorts and observed no notable differences. Two scores used subjective patient-level findings such as abdominal pain. Since this was a retrospective study with data extracted from the electronic medical record at the respective sites and since these subjective findings are not reliably documented in patient charts, these variables could not be used, limiting our ability to fully validate some of the scores. Additionally, not all sites provided all the objective data needed to run every score completely, such as the lack of imaging data from Wisconsin. However, other sites did provide these data, and such data did not improve the model performance at these sites.

CONCLUSIONS

Use of a retrospective patient cohort of 3646 patients from 3 healthcare systems to analyze 14 CDI severity scores showed that no model had reproducible, high, and accurate predictive ability. Future efforts to accurately model adverse outcomes from CDI would benefit from inclusion of patients from multiple centers and application of best practices in modeling including cross-validation and a train/test approach. This can be further augmented with innovative techniques such as machine learning applied to “big data” sources and novel biomarkers. This approach could result in achieving the goal of an accurate predictive model for adverse outcomes from CDI that can identify patients early in the disease course when interventions can be applied to maximally improve prognosis.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (grants U19AI09871, R21AI120599, and U01AI124255) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant R01HS027431).

Potential conflicts of interest. K. R. is supported in part by an investigator-initiated grant from Merck & Co, Inc and has consulted for Bio-K + International, Inc, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc, and Seres Therapeutics. V. B. Y. is a consultant for Vedanta Biosciences and is a senior editor for mSphere. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

D Alexander Perry, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Daniel Shirley, Division of Infectious Disease, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Dejan Micic, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Pratish C Patel, Division of Infectious Diseases, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Rosemary Putler, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Anitha Menon, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Vincent B Young, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Krishna Rao, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

References

- 1. Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC; Emerging Infections Program C. difficile Surveillance Team. . Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2369-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1539-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lofgren ET, Cole SR, Weber DJ, Anderson DJ, Moehring RW. Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infections: estimating all-cause mortality and length of stay. Epidemiology 2014; 25:570-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:1913-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olson MM, Shanholtzer CJ, Lee JT, Gerding DN. Ten years of prospective Clostridium difficile-associated disease surveillance and treatment at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, 1982-1991. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1994; 15:371-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Belmares J, Gerding DN, Parada JP, Miskevics S, Weaver F, Johnson S. Outcome of metronidazole therapy for Clostridium difficile disease and correlation with a scoring system. J Infect 2007; 55:495-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhangu S, Bhangu A, Nightingale P, Michael A. Mortality and risk stratification in patients with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12:241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Butt E, Foster JA, Keedwell E, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple, accurate and robust prediction rule for risk of mortality in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloomfield MG, Carmichael AJ, Gkrania-Klotsas E. Mortality in Clostridium difficile infection: a prospective analysis of risk predictors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25:700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drew RJ, Boyle B. RUWA scoring system: a novel predictive tool for the identification of patients at high risk for complications from Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 2009; 71:93-4; author reply 4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gujja D, Friedenberg FK. Predictors of serious complications due to Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29:635-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hensgens MP, Dekkers OM, Goorhuis A, LeCessie S, Kuijper EJ. Predicting a complicated course of Clostridium difficile infection at the bedside. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:0301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jardin CG, Palmer HR, Shah DN, et al. Assessment of treatment patterns and patient outcomes before vs after implementation of a severity-based Clostridium difficile infection treatment policy. J Hosp Infect 2013; 85:28-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kulaylat AS, Buonomo EL, Scully KW, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for mortality and adverse outcomes among patients with peripheral eosinopenia on admission for Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA Surg 2018; 153:1127-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lungulescu OA, Cao W, Gatskevich E, Tlhabano L, Stratidis JG. CSI: a severity index for Clostridium difficile infection at the time of admission. J Hosp Infect 2011; 79:151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller MA, Louie T, Mullane K, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple clinical bedside score (ATLAS) for Clostridium difficile infection which predicts response to therapy. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Na X, Martin AJ, Sethi S, et al. A multi-center prospective derivation and validation of a clinical prediction tool for severe Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0123405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toro DH, Amaral-Mojica KM, Rocha-Rodriguez R, Gutierrez-Nunez J. An innovative severity score index for Clostridium difficile infection: a prospective study. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2011; 19:336-9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Velazquez-Gomez I, Rocha-Rodriguez R, Toro DH, Gutierrez-Nuñez JJ, Gonzalez G, Saavedra S. A severity score index for Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2008; 16:376-8. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Welfare MR, Lalayiannis LC, Martin KE, Corbett S, Marshall B, Sarma JB. Co-morbidities as predictors of mortality in Clostridium difficile infection and derivation of the ARC predictive score. J Hosp Infect 2011; 79:359-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, Doherty JA, Kollef MH. Clostridium difficile-associated disease and mortality among the elderly critically ill. Crit Care Med 2009; 37:2583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kassam Z, Cribb Fabersunne C, Smith MB, et al. Clostridium difficile associated risk of death score (CARDS): a novel severity score to predict mortality among hospitalised patients with C. difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43:725-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McEllistrem MC, Carman RJ, Gerding DN, Genheimer CW, Zheng L. A hospital outbreak of Clostridium difficile disease associated with isolates carrying binary toxin genes. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:265-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:e1-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belmares J, Gerding DN, Tillotson G, Johnson S. Measuring the severity of Clostridium difficile infection: implications for management and drug development. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2008; 6:897-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Beurden YH, Hensgens MPM, Dekkers OM, Le Cessie S, Mulder CJJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE. External validation of three prediction tools for patients at risk of a complicated course of Clostridium difficile infection: disappointing in an outbreak setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017; 38:897-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujitani S, George WL, Murthy AR. Comparison of clinical severity score indices for Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32:220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arora V, Kachroo S, Ghantoji SS, Dupont HL, Garey KW. High Horn’s index score predicts poor outcomes in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 2011; 79:23-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wickham H, Francois R, Henry L, Muller K.. dplyr: a grammar of data manipulation. R package version 0.8.3. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kundu S, Aulchenko YS, Janssens ACJW.. PredictABEL: assessment of risk prediction models. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keilwagen J, Grosse I, Grau J. Area under precision-recall curves for weighted and unweighted data. PLoS One 2014; 9:e92209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown M. rmda: risk model decision analysis. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wickham H. stringr: simple, consistent wrappers for common string operations. R package version 1.4.0 ed. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saito T, Rehmsmeier M. Precrec: fast and accurate precision-recall and ROC curve calculations in R. Bioinformatics 2017; 33:145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX.. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beauregard-Paultre C, Abou Chakra CN, McGeer A, et al. External validation of clinical prediction rules for complications and mortality following Clostridioides difficile infection. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0226672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ozenne B, Subtil F, Maucort-Boulch D. The precision–recall curve overcame the optimism of the receiver operating characteristic curve in rare diseases. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68:855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li BY, Oh J, Young VB, Rao K, Wiens J. Using machine learning and the electronic health record to predict complicated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu H, Chen K, Sun Y, et al. Cytokines are markers of the Clostridium difficile-induced inflammatory response and predict disease severity. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2017; 24:e00037-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Archbald-Pannone LR. Quantitative fecal lactoferrin as a biomarker for severe Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized patients. J Geriatr Palliat Care 2014; 2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gerding DN, Kelly CP, Rahav G, et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in patients at increased risk for recurrence. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:649-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. ; OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. . Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:422-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fischer M, Sipe B, Cheng YW, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant in severe and severe-complicated Clostridium difficile: a promising treatment approach. Gut Microbes 2017; 8:289-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ, Greenberg A, et al. Long-term follow-up study of fecal microbiota transplantation for severe and/or complicated Clostridium difficile infection: a multicenter experience. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50:398-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.