Abstract

Rising inequality is one of the grand societal challenges of our time. Yet, its effects on firms – including multinational enterprises (MNEs) – and their operations have not been widely examined by IB scholars. In this study, we posit that income inequality within a country is positively associated with the incidence and severity of crime experienced by businesses. Further, we propose that this relationship will be negatively moderated by social cohesion (in the form of greater societal trust and lower ethno-linguistic fractionalization) in these countries, such that social cohesion helps to offset the negative impacts of inequality on crime against businesses. We test these hypotheses using a comprehensive data set of 114,000 firms from 122 countries and find consistent support for our theses. Our findings, which are robust to different alternative variables, model specifications, instrumentation, and estimation techniques, unpack the intricate ways through which inequality affects businesses worldwide and the associated challenges to MNEs. They also offer important managerial and policy insights regarding the consequences of inequality and potential mitigation mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1057/s41267-022-00535-5.

Keywords: income inequality, crime against businesses, social cohesion, trust, fractionalization

Résumé

L'inégalité croissante est l'un des grands défis sociétaux de notre époque. Pourtant, ses impacts sur les entreprises - y compris les entreprises multinationales - et leurs activités n'ont pas été largement examinés par les chercheurs en affaires internationales. Dans cette recherche, nous postulons que l'inégalité des revenus dans un pays est positivement associée à l'incidence et à la gravité de la criminalité subies par les entreprises. De plus, nous proposons que cette relation soit négativement modérée par la cohésion sociale dans ces pays (sous la forme d'une plus grande confiance sociétale et d'une plus faible fragmentation ethnolinguistique), dans la mesure où la cohésion sociale aide à compenser les impacts négatifs de l'inégalité sur la criminalité contre les entreprises. Nous testons ces hypothèses sur un ensemble complet de données de 114000 entreprises issues de 122 pays et trouvons des appuis cohérents à nos thèses. Nos résultats, robustes aux différentes variables alternatives, spécifications du modèle, techniques d'estimation et à l'instrumentation, dévoilent les manières complexes par lesquelles l'inégalité influe sur les entreprises dans le monde entier ainsi que sur les défis associés aux entreprises multinationales. Ils apportent également d’importants renseignements managérial et politique liés aux conséquences de l'inégalité et aux mécanismes d'atténuation potentiels.

Resumen

El aumento de la desigualdad es uno de los grandes desafíos sociales de nuestro tiempo. Con todo, sus efectos en las empresas, incluyendo las empresas multinacionales, y sus operaciones no han sido ampliamente examinado por académicos de Negocios Internacionales. En este estudio, planteamos que la desigualdad en un país está asociada positivamente con la incidencia y gravedad de la delincuencia que experimentan las empresas. Aún más, proponemos que esta relación será moderada negativamente por la cohesión social (en forma de mayor confianza social y menor fraccionamiento etnolingüístico) en estos países, para que la cohesión social ayuda a compensar los impactos negativos de la desigualdad en la delincuencia contra las empresas. Probamos estas hipótesis utilizando un exhaustivo conjunto de datos de 114.000 empresas de 122 países y encontramos un apoyo consistente a nuestras tesis. Nuestros hallazgos, que son robustos a diferentes variables alternativas, especificaciones del modelo, instrumentación y técnicas de estimación, desentrañan las maneras intrincadas en que la desigualdad afecta a las empresas de todo el mundo y los desafíos asociados a las empresas multinacionales. También ofrecen importantes perspectivas para la gerencia y política en relación con las consecuencias de la desigualdad y los posibles mecanismos de mitigación.

Resumo

O aumento da desigualdade é um dos grandes desafios sociais do nosso tempo. No entanto, seus efeitos sobre empresas – incluindo empresas multinacionais (MNEs) – e suas operações não foram amplamente examinados por acadêmicos de IB. Neste estudo, postulamos que a desigualdade de renda dentro de um país é positivamente associada à incidência e gravidade de crimes vivenciados por empresas. Além disso, propomos que essa relação seja negativamente moderada pela coesão social (na forma de maior confiança social e menor fracionamento etnolinguístico) nesses países, de modo que a coesão social ajude a compensar os impactos negativos da desigualdade em crimes contra empresas. Testamos essas hipóteses usando um conjunto de dados abrangente de 114.000 empresas de 122 países e encontramos consistente suporte para nossas teses. Nossos achados, robustos a diferentes variáveis alternativas, especificações de modelo, instrumentação e técnicas de estimação, desvendam as formas intrincadas pelas quais a desigualdade afeta negócios em todo o mundo e os desafios associados a MNEs. Eles também oferecem importantes insights gerenciais e de políticas no que tange às consequências da desigualdade bem como potenciais mecanismos mitigantes.

Abstract

日益增加的不平等是我们这个时代面临的重大社会挑战之一。然而, 它对包括跨国企业 (MNE) 在内的公司及其运营的影响尚未得到 IB 学者的广泛研究。在这项研究中, 我们假设一个国家内的收入不平等与企业所经历的犯罪发生率和严重程度正相关。此外, 我们提出, 这种关系将受到这些国家的社会凝聚力 (以较大的社会信任和较低的民族语言分裂的形式) 的负面调节, 这样的社会凝聚力有助于抵消不平等对针对企业的犯罪的负面影响。我们使用来自 122 个国家的 114,000 家公司的综合数据集检验了这些假设, 并为我们的论点找到了一致的支持。我们的研究结果对不同的替代变量、模型规范、仪器仪表和估算技术具有稳健性, 揭示了不平等影响全球企业的复杂方式以及MNE所面临的相关挑战。它们还就不平等的后果及潜在的缓解机制提供了重要的管理和政策见解。

INTRODUCTION

Rising inequality within countries poses ubiquitous social and economic concerns in both advanced and emerging economies (Marsh, 2016; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Inequality affects businesses by undermining their legitimacy (Shrivastava & Ivanova, 2015), altering operational configurations (Audebrand & Barros, 2018), and stimulating shareholder activism (Judge, Gaur, & Muller-Kahle, 2010). Traditionally, international business (IB) scholars have treated inequality as an issue that falls under the exclusive purview of governmental policymakers. Of late, however, inequality has been identified as a grand societal challenge that affects both domestic and multinational firms (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017). Subsequently, recent IB scholarship has begun to examine its consequences by focusing on its impact on the attractiveness of host countries (Bu, Luo, & Zhang, 2021; Lupton, Jiang, Escobar, & Jimenez, 2020) or the role MNEs play in perpetuating inequality (Giuliani, 2019). To date, the bulk of this work remains predominantly conceptual, and fails to provide a complete picture of the direct and indirect costs that inequality imposes on business organizations, including MNEs (Narula & van der Straaten, 2021). In response to recent calls to examine this phenomenon in a comparative, IB context (Arikan & Shenkar, 2021; Rygh, 2020), we examine the link between inequality and crime against businesses across the globe, and its deleterious impact on firms operating in these environments.

Crime has a significant and long-term impact on both economies as a whole (Neves & Silva, 2014) and firms doing business in unsafe environments (Islam, 2014; Mazhar & Rehman, 2019). Estimations of the societal impact of crime suggest that it accounts for a significant proportion of a country’s GDP (Brand & Price, 2000; Dettoto & Vannini, 2010) and is robustly associated with lower economic performance.1 Crime that targets businesses commonly results in reductions in sales growth, employment, and capital investments (Oguzoglu & Ranasinghe, 2013), slower development and adoption of innovations (Saridakis, Mohammed, & Sookram, 2015), and overall subpar firm performance (Commander & Svejnar, 2011). Yet, despite these critical implications for operation and performance of organizations, we still lack robust knowledge of the drivers and potential mitigators of crime, particularly in a cross-country or comparative context (Enderwick, 2019).

Combining elements from the economics of crime (Becker, 1968) and institutional theory (North, 1990), we argue that high levels of income inequality will lead to greater crime against businesses due to higher payoffs for criminal activities vis-à-vis legal work, the perceived deterioration of individuals’ relative social position, and the weakening of social institutions (Buonanno, 2003; Damm & Dustmann, 2014; Hicks & Hicks, 2014). In addition, we propose that the positive relationship between income inequality and crime against businesses will be weakened by greater social cohesion as reflected by its relational and ideational components (Moody & White, 2003) in the form of higher societal trust (Uslaner, 2002) and lower ethno-linguistic fractionalization (Luiz, 2015), respectively. We test these hypotheses using data on more than 114,000 firms from 122 countries over the period 2006–2018. Our empirical results provide support for our theoretical arguments and are robust to different alternative variables, model specifications, instrumentation, and estimation techniques.

We offer several contributions. First, we develop theoretical arguments that explicate the mechanisms through which greater income inequality within a country will trigger adverse effects on businesses – including MNEs – via increased exposure to crime (Dettoto & Vannini, 2010; Enderwick, 2019; Islam, 2014). Second, we examine potential contingencies that influence the relationship between inequality and crime against businesses by focusing on the moderating effect of social cohesion conceptualized via two components (Moody & White, 2003): a relational one in the form of societal trust (Beugelsdijk & Klasing, 2016) and an ideational one in the form of ethno-linguistic fractionalization (Luiz, 2015). Finally, we answer recent calls by IB and management scholars to examine inequality as one of the prominent societal challenges of our time (Amis, Munir, Lawrence, Hirsch, & McGahan, 2018; Bapuji, Ertug, & Shaw, 2020; Buckley et al., 2017) by explicating how inequality imposes direct and indirect costs on business operations worldwide (Falaster, Ferreira, & Li, 2021; Schotter & Beamish, 2013) via increased criminal activities. To the best of our knowledge, we are also the first to conduct a large-scale, cross-country investigation of the effect of within-country inequality on firms, its implications for MNEs, and potential mitigating mechanisms.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

IB scholars have exhibited growing interest in broader questions on the role of multinationals in both causing and solving grand societal challenges (Buckley et al., 2017). Despite this interest, much of the research on inequality has emanated from the allied social sciences of economics, development studies, and sociology, with a few notable exceptions from the IB scholarly community that have conceptually explored the interplay between inequality and internationalization activities (Doh, 2018; Giuliani, 2019; Narula & van der Straaten, 2021). In his review of research on MNEs and inequality, Rygh (2020) concluded that “…few IB studies have considered economic inequality, and even fewer have linked economic inequality up to the activities of MNEs” (p. 1), an assertion echoed by Arikan and Shenkar (2021) who identify inequality as one of the “neglected areas” in IB. Likewise, while the role of societal issues such as inequality and poverty in spurring various types of criminal activities has been examined by scholars from other disciplines, IB scholarship is yet to engage meaningfully in this discussion, with a few recent exceptions on crime and locational attractiveness (Bu et al., 2021; Falaster et al., 2021). We build on these recent efforts to develop our theoretical framework to examine the link on the relationship between inequality and crime against business.

Theoretically, the relationship between inequality and crime can be examined through several lenses. First, Merton’s (1938) strain theory suggests that individuals become more frustrated when placed near their more successful peers, and as this disparity increases, and they become more likely to channel their anger and resentment into crime. Second, the social disorganization tenet highlights the effect of inequality in lowering the ability of communities to oversee their members, which, combined with poverty, racial segregation, and family instability, triggers an increase in crime (Kornhauser, 1978). Lastly, the economic theory of crime depicts it as a rational decision whereby criminals weigh in the expected payoffs from illegal acts vis-à-vis those from legal work (Becker, 1968), both of which are affected by the availability and equality of economic opportunities in a society.

Complementing these theoretical tenets, empirical research in criminology and sociology has found a consistent and strong relationship between inequality and crime within different national contexts (Hsieh & Pugh, 1993). Overall, despite some heterogeneity in terms of the type of crimes and national contexts considered, the link between within-country inequality and criminal activities is robust and sizeable (Demombynes & Ozler, 2005; Kelly, 2000; Nilsson, 2004; Rufrancos, Power, Pickett, & Wilkinson, 2013; Soares, 2004).2

Building on these insights, we move beyond these generic effects and explore more specific implications of inequality for crime against business. Such an approach is warranted for several reasons. First, crime rates against businesses are usually higher than those against individuals (Hopkins, 2002) as businesses face crime from both external and internal agents such as customers or employees (Home Office, 2015). Second, crimes on businesses have broader social implications as they affect businesses both directly via operating costs (e.g., theft, damages, security expenses) and indirectly via negative externalities (such as employment, business closure, lower productivity), thus diverting resources away from other productive activities (Amin, 2010; Bapuji & Neville, 2015; Gaviria, 2002).3 Third, a better understanding of the mitigating factors of the relationship between inequality and crime against businesses is important for managers of firms (and MNEs) operating in (or seeking to enter) these markets, as well as for (local) governments in these countries seeking to reduce these negative impacts (Bu et al., 2021). Accordingly, in the next sections, we hypothesize the direct effect of income inequality on crime against businesses, as well as the moderating effects of informal institutions related to social cohesion.

Inequality and Crime Against Businesses

Inequality is likely to increase crime risk among businesses for at least three reasons. First, heightened inequality decreases the (perceived) ability of individuals to secure sufficient income for satisfying their needs, while providing greater returns from criminal activities relative to those from lawful work. As such, higher inequality will ultimately result in more crime by lowering the opportunity cost of engaging in illegal activities vis-à-vis obtaining an income through legal means (Hicks & Hicks, 2014). Naturally, the ability to find a job (Elliot & Ellingworth, 1992) and the potential to secure a stable and sufficient income (Loncher & Moretti, 2003) will affect this tradeoff. Therefore, the presence of significant economic disparities between the poor and the rich will make criminal activities appear as more attractive alternatives (Fajnzylber, Lederman, & Loayza, 2002). It has been documented that areas of high inequality, where poor individuals reside next to high-income businesses or individuals, become breeding grounds for crime (Amin, 2010; Kelly, 2000).

Second, the link between inequality and crime is driven also by psychological processes related to the (dis)satisfaction of an individual’s socio-economic status relative to peers (Hicks & Hicks, 2014). Poor individuals may be drawn towards criminal activities as their relative position on the income scale deteriorates, and they grow disenchanted by the perceived implausibility of improving their relative position. Therefore, a rise in inequality might reduce the moral threshold of poor individuals through an “envy effect” and spur them to commit crimes (Buonanno, 2003). As symbols of wealth and success, businesses, and in particular foreign-owned firms (Bu et al., 2021), can become easy targets of such envy-fueled criminal activities.

Finally, inequality tends to destabilize the social fabric of communities, thereby weakening societal institutions and the legitimacy of business. In the wake of surges in income inequality, societies witness eruptions in protest movements that advocate for redistributive policies (Bapuji & Neville, 2015). Such protests provide opportunity and motivation for arson and crime, even for ordinarily law-abiding citizens that feel marginalized by society (Robinson, 2005). Moreover, higher inequality tends to erode the legitimacy enjoyed by local businesses, turning them into permissible targets for crime (Shrivastava & Ivanova, 2015). Businesses are also more likely to be targeted by criminals in less-equal societies since such societies tend to have weaker rule of law (Sunde, Cervellati, & Fortunato, 2008) and underdeveloped institutions that cannot enforce the law effectively (Chong & Gradstein, 2007; Damm & Dustmann, 2014).

In sum, income inequality will make criminal activities toward business more alluring to low-income individuals via increased payoffs relative to legal work, perceived deterioration of their relative social position, and the weakening of social institutions. Therefore, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1:

Income inequality is positively associated with higher crime experienced by businesses.

The Mitigating Role of Social Cohesion

The effect of inequality on crime against businesses will likely differ across countries because of idiosyncratic institutional factors, both formal and informal (North, 1990). A natural candidate for such a moderation role is the level of social cohesion, which refers to a field of forces that act on members to remain in the group (Festinger, Back, & Schachter, 1950) and resist disruptive forces within the group (Gross & Martin, 1952). Social cohesion can be viewed as having a relational component (i.e., type and strength of connections among individuals in a social collective), which we suggest is reflected in societal trust, and an ideational component (i.e., the extent of members’ identification with the social collective), which is reflected in lower levels of ethno-linguistic fractionalization (Moody & White, 2003).

Defined as the belief in the honesty, integrity, and reliability of other individuals (Uslaner, 2002), societal trust has been a critical ingredient of cooperation and productivity among individuals, communities, and nations (Jones & George, 1998; Putnam, 1993). Building on this body of evidence, we posit that societal trust weakens the relationship between inequality and crime for multiple reasons. First, high-trust societies promote higher moral standards, even in the absence of strong formal regulations against criminal activities. In turn, individuals in these societies are more likely to develop a social conscience, which will reduce the attractiveness of criminal endeavors (Halpern, 2001) and diminish the level of envy vis-à-vis richer peers (Buonanno, 2003).

Second, there is substantial pressure among community members in high-trust societies to interact with all members (Halpern, 2001) regardless of their income status (i.e., an “ecological effect”). Societal trust enables disadvantaged community members, such as low-income individuals and/or minorities, to successfully integrate with the broader society. By enabling greater social and economic interaction that facilitates social mobility, trust counters the possibility that marginalized individuals and groups in unequal societies will resort to unlawful means for economic progress (Bellair, 1997). Through a favorable ecological effect, trust thus weakens the link between crime incidence and inequality by widening lawful means of economic engagement for individuals that would otherwise be potential perpetrators of crime.

Finally, high levels of trust in a community will yield stronger binding forces between individuals (Noteboom, 2000) that will weaken the negative effects of inequality in such environments. Greater trust between members of society will facilitate coordination and collective action, creating productive interdependencies that advance the greater good for all members. High levels of social capital will thus weaken the effect of inequality on criminal behavior by providing a more inclusive and representative institutional environment that stands for individuals at the lower end of the income spectrum (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989). Similarly, in societies with higher trust levels disenfranchised individuals are less likely to be skeptical of the presence of MNEs (Lu, Song, & Shang, 2018), and instead more likely to perceive opportunities for jobs and other income sources, which in turn will reduce the engagement in criminal activities (Daniele & Marani, 2011).

Hence, societal trust will act as an informal governance mechanism to mitigate the effect of income inequality on crime by maintaining a social conscience, encouraging collaboration, and strengthening bonding forces between community members. We therefore hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a:

Higher social cohesion in its relational form (i.e., societal trust) will weaken the effect of inequality on crime experienced by businesses.

The ideational element of social cohesion captures latent commonalities in cognitive and cultural cues that entail similarities in feelings of shared destiny among individuals (Beugelsdijk & Klasing, 2016). As such, it is shaped by social forces such as language, ethnicity, and race. This influence is aptly captured by the concept of ethno-linguistic fractionalization (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2005). In essence, ethno-linguistic fractionalization (i.e., the probability that two randomly chosen individuals belong to different ethnic and/or linguistic groups) reduces the cognitive and cultural homogeneity of a society, thereby reflecting a low degree of social cohesion.

We argue that high fractionalization will strengthen the effect of inequality on crimes experienced by businesses for three reasons. First, fractionalization weakens the degree of a collective vision and destiny in a society, thereby providing a justification for some individuals to resort to criminal activities. Further, greater ethnic and linguistic diversity increases competition between different groups for scarce resources (Putnam, 2007). This struggle increases identification with ethno-linguistic affiliations, resulting in in-group favoritism for allocation of jobs and other resources, while reducing opportunities for out-group individuals (Coenders, Lubbers, & Scheepers, 2004). In high fractionalization contexts, excluded individuals will be more inclined to resort to criminal activities as means to secure sufficient income (Fajnzylber et al., 2002).

Second, greater fractionalization is associated with more “hate crimes” against business, defined as offenses motivated by bias toward race, religion, ethnicity, or national origin (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2015). From this perspective, a large or growing minority group is often perceived as a threat to the majority group (in terms of jobs and wage competition), which in turn fuels ethnically motivated criminal acts against this minority (Jacobs & Wood, 1999). In addition, crimes against minority-owned businesses can serve to preserve power and income differences in a society by curbing the economic potential of minority ethnic groups (Levine & Campbell, 1972; Soylu & Sheehy-Skeffington, 2015). As such, the perceived risk of reprisal for crimes perpetrated against minority ethnic groups can be contingent on the relative size and power of the victimized minority group (Disha, Cavendish, & King, 2011).

Finally, fractionalization can also affect the ability of societies to deal effectively with crime (Papyrakis & Mo, 2014). Ethno-linguistic fractionalization will exacerbate the predilection of the ethnic groups in power to redistribute wealth and social goods based on arbitrary and self-serving logics (Alesina & La Ferrara, 2005). Greater fractionalization will result in more government intervention, weaker legislation and de facto enforcement, more corruption, and inferior provision of public goods such as educational programs (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1999). As a result, higher fractionalization will significantly reduce the ability of local institutions to deter crime against businesses via both punitive (i.e., enforcing the law) and preventive measures (i.e., educational access). Finally, given their inherent liability of foreignness, MNEs will likely suffer from crimes when societies are very unequal and deeply fractionalized, as ethnic groups will constantly fight for resources and political control and MNEs can easily get caught in the crossfire (Oetzel & Oh, 2019). In such contexts, real or perceived favoritism to one or another ethnic groups can easily expose them to serious risks of criminal act by a competing group.

In sum, low ideational social cohesion as reflected in high level of fractionalization reduces social bonds among the larger collective by engendering in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination. This, in turn, will increase crimes by disenfranchised minority groups against businesses owned by ethnic majorities, as well as hate crimes by majority groups against businesses owned by ethnic minorities. Further, when fractionalization is high, institutions are either unable to protect minorities or they may actively discriminate against them. Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2b:

Lower social cohesion in its ideational form (i.e., ethno-linguistic fractionalization) will strengthen the effect of inequality on crime experienced by businesses.

Methods

Sample and Data

We compiled our dataset from multiple sources with the World Bank’s Enterprises Surveys (WBES) serving as the primary data source. Table A1 (in the Online Appendix – OA-attached to this paper) provides a description of variables, operationalization, and data sources. WBES is one of the most comprehensive international firm-level datasets that is widely employed across different disciplines, including economics (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2002); finance (Beck, Demirgûç-Kunt, & Maksimovic, 2005) and management (Krammer, 2021; Krammer, Strange, & Lashitew, 2018; Uhlenbruck, Rodriguez, Doh, & Eden, 2006). Our sample covers 114,000 firms from 122 countries surveyed between 2006 and 2018 across both manufacturing (56%) and services (44%). Summary statistics and correlations between our variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics and correlations

| Descriptive statistics | Correlation coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | No. of countries | Mean | Std. dev. | Crime incidence | Crime losses (%) | Gini coefficient | |

| Crime incidence (binary) | 132,347 | 122 | 0.199 | 0.399 | 1 | ||

| Crime losses plus security expenses (%) | 128,593 | 122 | 1.518 | 4.238 | 0.407 | 1 | |

| Gini coefficient | 133,055 | 122 | 0.399 | 0.078 | 0.153 | 0.081 | 1 |

| Income share of the top 10% | 133,055 | 122 | 0.312 | 0.061 | 0.138 | 0.074 | 0.976 |

| Trust | 123,830 | 98 | 0.213 | 0.112 | − 0.044 | − 0.057 | − 0.372 |

| Linguistic fractionalization | 128,174 | 114 | 0.462 | 0.292 | − 0.029 | 0.068 | 0.113† |

| Linguistic fractionalization alternative | 131,097 | 119 | 0.509 | 0.320 | − 0.075 | 0.049 | 0.061† |

| Linguistic polarization | 131,097 | 119 | 0.438 | 0.246 | − 0.074 | − 0.012 | − 0.232 |

| Political polarization | 105,446 | 72 | 1.067 | 0.214 | − 0.014 | 0.049 | 0.234 |

| Political values (average) | 105,446 | 72 | 5.749 | 0.375 | 0.041 | 0.104 | 0.302 |

| Poverty rate | 132,896 | 121 | 0.175 | 0.215 | 0.018 | 0.121 | 0.279 |

| GDP per capita (PPP) | 130,667 | 119 | 10,629 | 9455 | 0.026 | − 0.08 | − 0.161† |

| GDP growth | 133,055 | 122 | 4.027 | 1.989 | − 0.12 | − 0.068 | − 0.033† |

| Inflation rate | 132,905 | 121 | 7.027 | 10.439 | 0.022 | 0.036 | 0.076† |

| Rule of law | 133,055 | 122 | − 0.391 | 0.714 | 0.021 | − 0.095 | − 0.119† |

| Control of corruption | 133,055 | 122 | − 0.398 | 0.681 | 0.071 | − 0.076 | − 0.013† |

| Secondary-school enrolment | 127,801 | 115 | 0.704 | 0.272 | 0.022 | − 0.105 | -0.189 |

| Youth unemployment | 132,515 | 120 | 0.163 | 0.121 | − 0.011 | − 0.041 | 0.061† |

| Firm age | 131,130 | 122 | 26.025 | 16.042 | 0.079 | − 0.006 | 0.11 |

| Firm size—employment (permanent) | 130,964 | 122 | 70.315 | 148.683 | 0.072 | − 0.021 | − 0.008 |

| Public firm (binary) | 130,752 | 122 | 0.014 | 0.116 | 0.007 | 0.036 | − 0.031 |

| Foreign firm (binary) | 130,713 | 122 | 0.107 | 0.309 | 0.057 | 0.034 | 0.098 |

| Exporting firm (binary) | 131,571 | 122 | 0.187 | 0.390 | − 0.004† | 0.003† | − 0.031† |

| Security payment (binary) | 132,527 | 122 | 0.626 | 0.484 | 0.151 | 0.171 | 0.077 |

†All correlation coefficients have p values below 0.05 apart from those marked with the symbol.

Dependent variable

Our main dependent variable captures the incidence of crime against firms, i.e., whether the business had experienced “losses as a result of theft, robbery, vandalism, or arson” during the past fiscal year. We also conduct additional analysis using the financial costs of crime (i.e., the estimated value of losses from crime plus security expenses as percentage of firm’s sales) for which data availability is more limited. Overall, almost 20% of the firms in our sample experienced crime, and losses from crime plus security expenses were equivalent to 1.5% of annual sales revenues, suggesting significant effects on businesses.

Independent variables

Income inequality is measured using the average Gini coefficient between 2006 and 2018 (from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators-WDI-) to match the years covered by the WBES. As noted above, we identify two elements of social cohesion. To capture the relational component of social cohesion which can be summarized as trust, we employ data on trust from the World Values Survey, the European Values Survey, and the Global Barometer Survey. We used a standard measure of trust in the literature based on the proportion of individuals who responded positively to the question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted?” (Delhey, Newton, & Welzel, 2011; Knack & Keefer, 1997; Krammer, 2019). We measured the ideational dimension of social cohesion, fractionalization, using the level of linguistic fractionalization (Docquier, Lohest, & Marfouk, 2007; Luiz, 2015; Miguel, Satyanath, & Sergenti, 2004) computed as the inverse of the Herfindahl index for linguistic composition in a country, drawn from Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg (2003). Our robustness analyses also include two alternative proxies for fractionalization.

Control variables

In line with the economic approach regarding the opportunity costs of criminal activities (Becker, 1968), we included the following controls for economic opportunities (data comes from WDI): (1) share of the population below the poverty line; (2) GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity); (3) GDP growth rate, and (4) the rate of inflation (Consumer Price Index). In robustness analyses we also included the youth unemployment rate and secondary school enrollment rate. Considering the importance of law enforcement and policing (Becker, 1968; Levitt, 1997), we also included a measure of rule of law which measures the de jure enforcement of “the rules of society” and containment of “crime and violence”. We also controlled for the level of corruption in these countries as it is a good indication of whether laws are de facto implemented in these jurisdictions (Krammer, 2019). Corruption levels were measured as the extent to which “public power is exercised for private gain.” We also included several firm-specific controls, including firm size (number of employees), age, export status, and ownership characteristics indicating (partial) foreign or governmental ownership. In addition, we controlled for firm-specific security deterrence using a dummy variable that captured whether the firm spent money for “equipment, personnel, or professional security services.” Finally, since crime rates are likely to vary across years and industries, we also included year and industry dummies in all our regressions.

Empirical Analysis and Results

For testing our hypotheses, we employ a probit model in line with the binary nature of our primary dependent variable (i.e., crime incidence). Since our sample is stratified at industry level within countries, we cluster the standard errors within country–industry groups (Abadie, Athey, Imbens, & Wooldridge, 2017).

Our baseline results are reported in Table 2. Model 1 includes only control variables, Model 2 includes inequality, while Models 3 and 4 examine the interaction between inequality and, respectively, trust and fractionalization. Model 5 includes both interactions simultaneously. Overall, we find support for our hypotheses. The Gini coefficient was positive and significant (β = 1.57, p value = 0.00, Model 2) in line with Hypothesis 1. The interaction term between the Gini coefficient and trust was negative and significant (β = − 5.9, p value = 0.00, Model 3), and the interaction between the Gini coefficient and ethno-linguistic fractionalization was positive and significant (β = 1.6, p value = 0.00, Model 4), thus supporting Hypotheses 2a and 2b.

Table 2.

Income inequality and crime against businesses: Baseline probit estimations

| Dependent variable: crime incidence | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |||||||||||

| Coeff. | S.E. | p value | Coeff. | S.E. | p value | Coeff. | S.E. | p value | Coeff. | S.E. | p value | Coeff. | S.E. | p value | |

| Poverty rate | 0.638 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.479 | 0.087 | 0.000 | 0.334 | 0.082 | 0.000 | 0.420 | 0.085 | 0.000 |

| Log (GDP per capita) | − 0.060 | 0.021 | 0.004 | − 0.089 | 0.022 | 0.000 | − 0.081 | 0.023 | 0.001 | − 0.079 | 0.022 | 0.000 | − 0.069 | 0.023 | 0.003 |

| GDP per capita growth | − 0.099 | 0.007 | 0.000 | − 0.099 | 0.007 | 0.000 | − 0.097 | 0.007 | 0.000 | − 0.098 | 0.007 | 0.000 | − 0.095 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| Inflation | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Rule of law | − 0.172 | 0.052 | 0.001 | − 0.098 | 0.055 | 0.074 | − 0.108 | 0.061 | 0.080 | − 0.104 | 0.056 | 0.062 | − 0.120 | 0.061 | 0.048 |

| Control of corruption | 0.308 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.236 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.244 | 0.061 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.056 | 0.000 | 0.256 | 0.061 | 0.000 |

| Log (Firm age) | 0.048 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.006 | 0.043 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.006 |

| Log (firm size) | 0.069 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.068 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.006 | 0.000 |

| Public dummy | 0.054 | 0.051 | 0.287 | 0.082 | 0.051 | 0.110 | 0.103 | 0.053 | 0.049 | 0.079 | 0.053 | 0.132 | 0.105 | 0.054 | 0.051 |

| Foreign dummy | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.350 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.886 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.516 | − 0.008 | 0.019 | 0.669 |

| Exporter dummy | − 0.046 | 0.017 | 0.008 | − 0.036 | 0.017 | 0.037 | − 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.054 | − 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.044 | − 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.059 |

| Security payment | 0.400 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.396 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.394 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.401 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.399 | 0.014 | 0.000 |

| Gini | 1.571 | 0.147 | 0.000 | 2.649 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 0.753 | 0.253 | 0.003 | 1.640 | 0.370 | 0.000 | |||

| Trust | 2.112 | 0.678 | 0.002 | 2.516 | 0.673 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Gini × Trust | − 5.920 | 1.711 | 0.001 | − 7.021 | 1.702 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Linguistic frac. | − 0.464 | 0.174 | 0.008 | − 0.760 | 0.189 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Gini × Linguistic frac. | 1.602 | 0.403 | 0.000 | 2.396 | 0.436 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Industry dummies | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | ||||||||||

| Year dummies | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | ||||||||||

| Observations | 114,202 | 114,202 | 107,484 | 110,437 | 103,988 | ||||||||||

The reported standard errors (S.E.) are corrected for potential correlations among firms within the same country–industry clusters.

Magnitude of effects

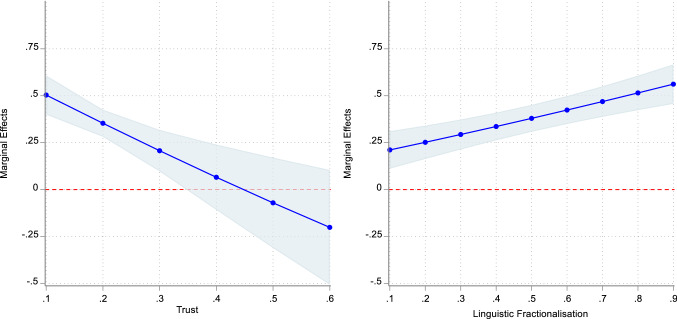

Following standard practice, we discuss the marginal effects on the observed probability of crime incidence against each of the two moderating variables, and represent them graphically in Figure 1 (Hoetker, 2007; Wooldridge, 2016). The average marginal effect of the Gini coefficient on crime incidence is 0.39 (Model 2). Since the Gini is measured in the range of 0–1, this value indicated that an increase of one decile in the Gini coefficient (or 10 percentage points) on the probability of crime incidence is 0.039. In other words, the probability of a firm experiencing crime increased by 3.9% as the Gini rose by one decile, for example, from the level seen in Ethiopia or Poland (Gini = 0.33) to that of Slovenia or Ghana (Gini = 0.43). Compared to the average probability of crime incidence in our sample, which is 0.199, this value represented a 19% increase in crime rate, showing that variations in inequality are associated with sizable differences in crime rates faced by firms.

Figure 1.

The marginal effects of income inequality on the probability of crime incidence.

Figure 1 presents the average marginal effects across all observations. The left panel shows that the marginal effect of inequality declines sharply when trust increases (its average value is 0.21), effectively nullifying the positive effect of inequality on business crime. This decline is so strong that the marginal effect of inequality on crime becomes statistically insignificant (0.14) when trust levels reach 0.35 (i.e., case of Thailand, Ukraine, and Armenia). In Bangladesh, where trust is at the first quartile of the sample (0.13), the marginal effect of inequality is four times higher (0.43). Similarly, the right panel of Figure 1 shows that the marginal effect of inequality is greater at higher levels of ethno-linguistic fractionalization. The marginal effect was 0.23 in China, where the level of fractionalization is at the first quartile in the sample (0.13). In contrast, the marginal effect was more than twice as high (0.47) in Burkina Faso, whose level of linguistic fractionalization was at the third quartile (0.72).

Robustness Tests

We also conducted several tests to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, we check potential endogeneity of trust in our model and instrument trust with the degree of polarization in political values in a country (from the World and European Value Surveys). This instrumentation approach follows Beugelsdijk & Klasing (2016) who found that polarization of political values related to government intervention and the need to redistribute income is an important predictor of trust, independent from the effects of fractionalization and inequality. Given that trust, inequality, and polarization are country-level concepts we perform a two-step instrumental variable (IV) analysis (Wooldridge, 2016): in the first stage we predict the exogenous component of social trust in a country-level setting (Table A2, OA – the Online Appendix) while in the second stage we use these predicted values to re-run our firm-level analysis4 (Table A3, OA). The estimates show good predictive power and confirm that societal trust remains a robust moderator of the effects of inequality on crimes against businesses. More details on the procedure and results are provided in the Online Appendix.

Second, we employ alternate measures for our variables of interest and successfully re-assess our models. Hence, we use an alternative measure of inequality that captured the income shares of the richest 10% of the population (Table A4, OA) and two alternate measures for fractionalization from Desmet, Ortuño-Ortín and Wacziarg (2012) in the form of language families and linguistic groups’ sizes in a country (Table A5, OA). Further, recognizing the limitation of using a binary variable to capture crime, we employ an alternative measure that captures the value of firms’ losses from theft plus security expenses as a percentage of its annual sales. While this measurement provides a more accurate, quantitative estimate of the effects of crime on firms, it suffers from lower coverage in terms of observations (Table A6, OA). Our results (Model 2) suggest that one decile increase in the Gini leads to an increase of crime loss and security expense relative to sales by 0.32 percentage points, a 20% increase relative to the mean. We also discuss and graph again the marginal effects when using this alternate DV in Figure A1 (OA).

Third, we include additional controls that influence certain types of crimes, but for which we lack good coverage across all countries in our sample. Specifically, we included secondary school enrolment and youth unemployment rates (Lancher, 2007; Loncher & Moretti, 2003; Luiz, 2001). Results (Table A7, OA) show that despite the decrease in sample size, our hypotheses are supported after controlling for these factors.

Fourth, we conducted an additional analysis at the regional level to check whether cross-regional differences in crime (rather than across firms) drive our results. These initial results (Table A8, OA) provided support for H1 and H2a but not for H2b. We further investigate this issue by employing two alternative fractionalizations measures to address the significant reduction in terms of observations (Table A9, OA) and these results provide support for all our hypotheses.

Fifth, we examined the effect size indices following Cohen (1988). While the f2 values were small (i.e., 0.033 for crime incidence and 0.012 for crime losses), they are in accordance with the multitude and complexity of drivers for crime in the literature (Becker, 1968). Moreover, we also replicated our analysis on random sub-samples of one-half, one-third, and one-quarter of total observations to ensure that our results are not driven by the large size of our sample. Our results remained robust in these tests.

Finally, firms within a country share other market and institutional conditions besides social cohesion or inequality. To better isolate these potential interplays, we also employ a mixed effects probit with random country effects (Table A10, OA). The results confirm our baseline findings.

Post Hoc Analysis

To further explore the applicability of our findings for IB and internationalization outcomes, we conduct an additional analysis that focuses on foreign-owned firms and exporting firms in our dataset. The results (Table A11, OA) show that inequality is associated with greater crime incidence for both foreign-owned firms and exporters. Social cohesion also plays a moderating role, although the specific mechanism seems to differ between the two types of firms. For foreign firms, trust significantly moderates the link between inequality and crime (but not fractionalization); for exporting firms, fractionalization significantly moderates the link between inequality and crime (but not trust). These results suggest that the mechanisms through which the inequality–crime link can be mitigated vary across different firm types. Future research can provide substantive evidence that explicates the link between crime, inequality, and social cohesion for different internationalization processes.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We examined the effect of within-country income inequality on crimes against business, and the potential moderators of this relationship in the form of social cohesion across a large sample of countries. Our analysis supports the thesis that within-country income inequality is positively associated with the incidence of crime against businesses, and that social cohesion as reflected in greater societal trust and lower fractionalization mitigates this effect.

Contributions

Our study contributes to research in several ways. First, it is likely the first attempt at theorizing the impact of inequality on societies via crimes against business organizations, including MNEs (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). In so doing, we substantially deepen current understanding of the relationship between economic inequality and organizations (Bapuji et al., 2020). Given the significant negative implications of criminal activities for firms and societies alike (Dettoto & Vannini, 2010; Mazhar & Rehman, 2019), our study provides a much-needed analysis of the drivers of crime in a comparative, international context (Enderwick, 2019). This is relevant for MNEs that seek to invest in countries characterized by high inequality (Judge, Fainshmid & Brown, 2014; Lupton et al., 2020), not just because of the potential reputational and other legitimacy risks, but also because such societies are more likely to feature higher levels of crime against business that reduces their locational attractiveness (Bu et al., 2021; Falaster et al., 2021).

Second, we uncover some important contingencies that influence the relationship between inequality and crime. By focusing on two components of social cohesion (trust and fractionalization), we show that two countries with similar levels of inequality may not necessarily experience the same level of crime against businesses. Greater cohesion either via high societal trust or less fractionalization mitigates the influence of inequality on crime, attesting to the importance of the social context in mitigating the consequences of unequal environments (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; Krammer, 2019; Luiz, 2015; Oetzel & Oh, 2019).

Finally, by demonstrating theoretically and empirically the impact of inequality on businesses, we answer multiple calls both in the IB (Arikan & Shenkar, 2021; Buckley et al., 2017; Judge et al., 2014) and management (Amis et al., 2018; Bapuji et al., 2020) literatures to understand the consequences of grand societal challenges for organizations. Our insights contribute to debates about the role of inequality within countries in exacerbating anti-globalization sentiments around the world (Witt, 2019), particularly in the post COVID-19 global environment (Ciravegna & Michailova, 2021). While the neoclassic economic consensus postulates that globalization has helped lift tens of millions of individuals around the world out of poverty and spurred economic convergence across countries (Williamson, 1996), it has also increased within-country inequality in terms of income, education, and opportunities for certain groups of individuals (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Our study demonstrates that, in addition to these first-order negative externalities, there might be second-order effects on the broader societal functioning, as reflected in crime against business, which bear clear negative implications for MNE investment and operations in such countries. Such an acknowledgement may also help policymakers develop approaches that leverage the most positive aspects of globalization while mitigating the negative outcomes.

Managerial and Policy Implications

Our study offers important implications for organizational practice and policy. Considering that income inequality influences crimes against businesses, MNEs should be careful about investing in countries characterized by high inequality, not just because of the potential reputational and other legitimacy challenges, but also because such endeavors are likely to turn costlier and riskier due to higher rates of criminality against businesses. Subsidiary managers in such countries might be wise to develop systems to improve the security of business establishments and enhance the safety of employees handling cash and other valuable assets. Our results show that a decile increase in inequality as proxied by the Gini coefficient would trigger 3.9% increase in crime incidence and 0.32 percentage point increase in sale revenue losses (or 20% increase relative to average losses). Further, managers of MNEs can better manage operating costs and risks by making viable decisions that consider a country’s trust and fractionalization levels, rather than simply avoiding all high-inequality countries as places to conduct business. Policymakers should consider that, in addition to its social and economic impacts, inequality also affects the business environment; higher crime countries and regions are less likely to attract both domestic and foreign investment. As such, existing inequality within countries may further undermine their social and economic development by acting as a deterrent on business investment and growth. Similarly, we document the beneficial role of a cohesive society in the form of greater social trust and lower ethno-linguistic fractionalization. Indeed, our results illustrate the significant deterring effects of social cohesion, which, at sufficiently high levels, can nullify the effect of inequality on business crime. These findings support the implementation of cohesion policies as an avenue to both reduce social costs and improve the business environments in these countries.

Future Directions

Our work reveals several promising avenues of research on the organizational effects of inequality in an IB setting. For instance, future research can examine how income inequality within countries influences organizational performance through other, less explored channels related to human development. For example, income inequality has been associated with a range of health indicators (e.g., obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and mental illnesses) whose effect on organizational performance have yet to be examined. Future research could reveal the ways in which organizations might be bearing part of the costs of unequal socioeconomic circumstances, just as societies often bear the cost of organizational externalities such as the lack of health coverage for employees (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009), adoption of environmental standards (Bapuji et al., 2020), or skewed distribution of revenues via global value chains (Nachum, 2021).

In addition, the recent COVID-19 crisis has significant implications for the global evolution of inequality. The pandemic has effectively sanded the wheels of globalization, reversing the decades-long trend of declining cross-country inequality and further exacerbating within-country inequalities (Ciravegna & Michailova, 2021). These trends will have profound long-term implications that could affect firms in both emerging and developed countries via crime and other channels, weakening their adaptability, survival, and success in this new environment (Krammer, 2021).

Furthermore, IB scholars have recognized the importance of crime-free environments for firms to conduct their daily business operations (Bu et al., 2021). Our findings suggest that social cohesion can be crucial for reducing the exclusion of the poor from social and economic engagement and thus combat one of its unintended consequences, namely crime (Hall, Matos, Sheehan, & Silvestre, 2012). In this way, we provide reinforcing evidence of the relationship between business and society by examining an important, yet under-researched area of crime against businesses (Islam, 2014).

Lastly, our study makes an important case for interdisciplinary approaches to addressing grand societal challenges by incorporating insights from other social sciences (e.g., economics, sociology, criminology), not all of which are frequently integrated in management and international business studies. Different approaches and theoretical lenses may yield different, yet complementary, insights that can shed light on this complex phenomenon (Hicks & Hicks, 2014). Within this large puzzle, our study clearly shows that income inequality within a country affects society through more crime, implicitly raising the costs of doing business and making the country a less attractive choice for multinationals (Falaster et al., 2021; Schotter & Beamish, 2013).

Limitations

Notwithstanding these contributions, this work has several caveats that present opportunities for further research. Firstly, our dependent variable did not contain information on who (insiders or outsiders vis-à-vis the firm) committed the crime. Thus, an interesting extension would be to disentangle the role of inequality on employees’ criminal behavior (Greenberg, 1990). In addition, future studies may want to contrast the effects of crimes for private gains (e.g., theft, fraud) versus malicious intent (e.g., looting, vandalism) as our data does not distinguish between these categories.

Secondly, the socio-economic conditions in a country tend to be relatively “sticky” or constant, particularly in the short and medium term. Thus, we adopt an empirical strategy that exploits cross-country heterogeneities and controls for other unobserved temporal and industry characteristics that can affect firms’ exposure to crime. However, we want to emphasize the need for better understanding of the temporal dynamics of this relationship, which can be important for both scholarly and policy considerations (Luiz, 2001; Oetzel & Oh, 2019).

Finally, WBES covers only formally registered businesses and predominantly emerging markets. However, in many emerging markets there are many informal firms that may face greater exposure to crime, since they operate outside legal protection (Islam, 2014). This can imply that our estimations are quite conservative in terms of the actual effects of inequality on crime against businesses. Conversely, inclusion of more developed economies (contingent on the coverage of future WBES rounds of surveys) would increase generalizability of these findings.

Conclusion

Widening inequality is a defining challenge for developed and developing countries alike, and COVID-19 and recent policy and technological developments have only exacerbated this problem (Chong & Gradstein, 2007). While IB scholars have called for more research on inequality as one of the great societal challenges of our time (Buckley et al., 2017), work in this area has remained scant and mostly conceptual. Answering recent calls in the IB community (Arikan & Shenkar, 2021; Rygh, 2020), we examine the impact of inequality on business organizations and the role of societal contingencies in influencing these effects (Amis et al., 2018). We have documented a robust positive association between inequality and crime against businesses, and identified key environmental contingencies (i.e., social cohesion, as reflected by societal trust and lower fractionalization) that can blunt that relationship. We hope that our efforts will stimulate other studies to provide a fuller picture of the range of effects inequality has on social well-being, and to identify useful lessons for policymakers and managers worldwide.

Notes

Brand and Price (2000) estimate the total crime costs in Wales and England to be around 6.5% of GDP, while Dettoto and Vannini (2010) evaluate the burden of a relevant subset of crime offenses (about 65% of the total) to equal about 2.6% of the Italian GDP.

For example, a reduction of inequality in Colombia to the level of Argentina or the United Kingdom would result in a 50% drop in crime (Soares, 2004).

The average crime losses experienced by Eastern European firms were two times larger than what they spend on R&D, while their security-related expenses were six times larger (Amin, 2010).

In the first stage, a joint test for the significance of the level and polarization of political values shows that they are significant with an F value of 3.95 and p value of 0.025, indicating strong instruments. The two-step procedure provides unbiased estimates for the coefficients that are equal with the one-step 2SLS estimator but the standard errors for the predicted variable are only approximations of those from the one-stage process (Woolridge, 2016). Other studies that used this approach of instrumentation include Carboni and Medda (2018) and Kim, Baum, Ganz, Subramanian and Kawachi (2011).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Biographies

Sorin M. S. Krammer

(PhD, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, USA) is Professor of Strategy and International Business at University of Exeter Business School (University of Exeter, UK). His research focuses on various aspects of innovation activities in international, comparative contexts and has been previously published in journals such as Journal of Management, Research Policy, Journal of World Business, Journal of Product Innovation Management, and others. He has been awarded the Haynes Prize for the Most Promising Young Scholar by the AIB.

Addisu A. Lashitew

(PhD, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) is Assistant Professor at DeGroote School of Business (McMaster University, Canada) and a non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institution (Washington DC, USA). He was previously a David Rubenstein Research Fellow at the Global Economy and Development Program of the Brookings Institution. His research and teaching cover diverse topics in development economics including corporate sustainability, social innovation, and impact investing.

Jonathan P. Doh

(PhD, George Washington University, USA) is Associate Dean of Research and Global Engagement, Rammrath Chair in International Business, Co-Faculty Director of the Moran Center for Global Leadership, and Professor of Management at the Villanova School of Business, Villanova University (Villanova, PA, USA). He teaches and does research at the intersection of international business, strategic management, and corporate sustainability. From 2014–2018, he was Editor-in-Chief of Journal of World Business and currently serves as General Editor of Journal of Management Studies.

Hari Bapuji

is a Professor in the Department of Management and Marketing, Faculty of Business and Economics, The University of Melbourne, Australia. His primary research interests lie at the intersection of business and society, with a particular focus on how economic inequality affects businesses and vice versa. His research appeared in world’s leading management journals and has also been noted for its impact on practice and policy. He serves as a co-editor of Business & Society and is a co-founder of Action to Improve Representation.

Footnotes

The article has been corrected by adding author Hari Bapuji, University of Melbourne, Australia, and his biographical sketch

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Arjen van Witteloostuijn, Area Editor, 4 April 2022. This article has been with the authors for two revisions.

Change history

1/9/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1057/s41267-022-00586-8

REFERENCES

- Abadie, A., Athey, S., Imbens, G. W., & Wooldridge, J. 2017. When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? (No. 24003). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Aguilera RV, Grøgaard B. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies. 2019;50(1):20–35. doi: 10.1057/s41267-018-0201-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, Devleeschauwer A, Easterly W, Kurlat S, Wacziarg R. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth. 2003;8:155–194. doi: 10.1023/A:1024471506938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alesina A, La Ferrara E. Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities. Journal of Public Economics. 2005;89:897–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin, M. 2010. Crime and security in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region. Enterprise Note 15, World Bank.

- Amis JM, Munir KA, Lawrence TB, Hirsch P, McGahan A. Inequality, institutions and organizations. Organization Studies. 2018;39(9):1131–1152. doi: 10.1177/0170840618792596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arikan I, Shenkar O. Neglected elements: What we should cover more of in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies. 2021 doi: 10.1057/s41267-021-00472-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audebrand, L. K., & Barros, M. 2018. All equal in death? Fighting inequality in the contemporary funeral industry. Organization Studies, 39(9): 1323–1343.

- Bapuji H, Ertug G, Shaw JD. Organizations and societal economic inequality: A review and way forward. Academy of Management Annals. 2020;14(1):60–91. doi: 10.5465/annals.2018.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bapuji H, Neville L. Income inequality ignored? An agenda for business and strategic organization. Strategic Organization. 2015;13:233–246. doi: 10.1177/1476127015589902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Demirgûç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V. Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? Journal of Finance. 2005;60:137–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00727.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy. 1968;76:167–217. doi: 10.1086/259394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk S, Klasing MJ. Diversity and trust: The role of shared values. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2016;44(3):522–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2015.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellair, P. E. 1997. Social interaction and community crime: Examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology, 35(4): 677–704.

- Bu J, Luo Y, Zhang H. The dark side of informal institutions: How crime, corruption, and informality influence foreign firms' commitment. Global Strategy Journal. 2021 doi: 10.1002/gsj.1417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley PJ, Doh JP, Benischke MH. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies. 2017;48(9):908–921. doi: 10.1057/s41267-017-0102-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno, P. 2003. The socioeconomic determinants of crime: A review of the literature. Università di Milano, Dipartimento di Economia Politica. Working Paper 63.

- Brand, S., & Price, R. 2000. The economic and social costs of crime. Home Office Research Study no.217, Home Office, London (UK).

- Carboni OA, Medda G. R&D, export and investment decision: Evidence from European firms. Applied Economics. 2018;50(2):187–201. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2017.1332747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chong A, Gradstein M. Inequality and institutions. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2007;89:454–465. doi: 10.1162/rest.89.3.454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciravegna, L., & Michailova, S. 2021. Why the world economy needs, but will not get, more globalization in the post-COVID-19 decade. Journal of International Business Studies, pp. 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coenders, M., Lubbers, M., & Scheepers, P. 2004. Majorities’ Attitudes towards Minorities in Western and Eastern European Societies: Results from the European Social Survey 2002–2003 (Report 4 for the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia). Vienna: European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Commander, S., & Svejnar, J. 2011. Business environment, exports, ownership, and firm performance. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1): 309–337.

- Damm AP, Dustmann C. Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior? The American Economic Review. 2014;104:1806–1832. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.6.1806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele V, Marani U. Organized crime, the quality of local institutions and FDI in Italy: A panel data analysis. European Journal of Political Economy. 2011;27(1):132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delhey J, Newton K, Welzel C. How general is trust in “most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:786–807. doi: 10.1177/0003122411420817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demombynes G, Ozler B. Crime and local inequality in South Africa. Journal of Development Economics. 2005;76:265–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2003.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet K, Ortuño-Ortín I, Wacziarg R. The political economy of linguistic cleavages. Journal of Development Economics. 2012;97:322–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Detotto C, Vannini M. Counting the cost of crime in Italy. Global Crime. 2010;11(4):421–435. doi: 10.1080/17440572.2010.519523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Disha I, Cavendish JC, King RD. Historical events and spaces of hate: Hate crimes against Arabs and Muslims in post-9/11 America. Social Problems. 2011;58:21–46. doi: 10.1525/sp.2011.58.1.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Djankov S, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A. The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2002;117:1–37. doi: 10.1162/003355302753399436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier F, Lohest O, Marfouk A. Brain drain in developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review. 2007;21:193–218. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhm008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doh J. MNEs, FDI, inequality and growth. Multinational Business Review. 2018 doi: 10.1108/MBR-09-2018-0062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot C, Ellingworth D. The relationship between unemployment and crime: A cross-sectional analysis employing the British Crime Survey. International Journal of Manpower. 1992;16:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Enderwick P. Understanding cross-border crime: The value of international business research. Critical Perspectives on International Business. 2019;15(2/3):119–138. doi: 10.1108/cpoib-01-2019-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fajnzylber P, Lederman D, Loayza N. Inequality and violent crime. Journal of Law and Economics. 2002;45:1–40. doi: 10.1086/338347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falaster C, Ferreira MP, Li D. The influence of generalized and arbitrary institutional inefficiencies on the ownership decision in cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies. 2021;52:1–26. doi: 10.1057/s41267-021-00434-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). 2015. Hate crime statistics. Available at: www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2015/november/latest-hate-crime-statistics-available.

- Festinger L, Back KW, Schachter S. Social pressures in informal groups: A study of human factors in housing. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviria A. Assessing the effects of corruption and crime on firm performance: Evidence from Latin America. Emerging Markets Review. 2002;3:245–268. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0141(02)00024-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani E. Why multinational enterprises may be causing more inequality than we think. Multinational Business Review. 2019;27(3):5. doi: 10.1108/MBR-10-2018-0068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J. Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1990;75:561–568. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross N, Martin WE. On group cohesiveness. American Journal of Sociology. 1952;57:546–564. doi: 10.1086/221041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Matos S, Sheehan L, Silvestre B. Entrepreneurship and innovation at the base of the pyramid: A recipe for inclusive growth or social exclusion? Journal of Management Studies. 2012;49:785–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01044.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern D. Moral values, social trust and inequality: Can values explain crime? British Journal of Criminology. 2001;41:236–251. doi: 10.1093/bjc/41.2.236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks DL, Hicks JH. Jealous of the Joneses: Conspicuous consumption, inequality and crime. Oxford Economic Papers. 2014;66:1090–1120. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpu019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoetker G. The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: Critical issues. Strategic Management Journal. 2007;28:331–343. doi: 10.1002/smj.582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Home Office 2015. Crime against businesses: Findings from the 2014 commercial victimisation survey in the UK. Available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/.

- Hopkins M. Crimes against businesses: The way forward for future research. British Journal of Criminology. 2002;42:782–797. doi: 10.1093/bjc/42.4.782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CC, Pugh MD. Poverty, income inequality, and violent crime: A meta-analysis of recent aggregate data studies. Criminal Justice Review. 1993;18:182–202. doi: 10.1177/073401689301800203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam A. Economic growth and crime against small and medium sized enterprises in developing economies. Small Business Economics. 2014;43:677–695. doi: 10.1007/s11187-014-9548-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D, Wood K. Interracial conflict and interracial homicide: Do political and economic rivalries explain white killings of blacks or black killings of whites? American Journal of Sociology. 1999;105:157–190. doi: 10.1086/210270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GR, George JM. The experience and evolution of trust: Implications for cooperation and teamwork. Academy of Management Review. 1998;23:531–546. doi: 10.2307/259293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Judge WQ, Fainshmidt S, Brown JL., III Which model of capitalism best delivers both wealth and equality? Journal of International Business Studies. 2014;45(4):363–386. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2014.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Judge WQ, Gaur A, Muller-Kahle MI. Antecedents of shareholder activism in target firms: Evidence from a multi-country study. Corporate Governance-an International Review. 2010;18(4):258–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8683.2010.00797.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. Inequality and crime. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2000;82:530–539. doi: 10.1162/003465300559028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman HC, Hamilton VL. Crimes of obedience. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Baum CF, Ganz ML, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The contextual effects of social capital on health: A cross-national instrumental variable analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(12):1689–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knack S, Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997;12:1251–1288. doi: 10.1162/003355300555475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser RR. Social sources of delinquency: An appraisal of analytic models. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer SM. Greasing the wheels of change: Bribery, institutions, and new product introductions in emerging markets. Journal of Management. 2019;45(5):1889–1926. doi: 10.1177/0149206317736588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer SM. Navigating the New Normal: Which firms have adapted better to the COVID-19 disruption? Technovation. 2021;110:102368. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer SM, Strange R, Lashitew A. The export performance of emerging economy firms: The influence of firm capabilities and institutional environments. International Business Review. 2018;27(1):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny R. The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 1999;15:222–279. doi: 10.1093/jleo/15.1.222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancher L. Education and crimes, a review of literature. London: University of Western Ontario; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levine RA, Campbell DT. Ethnocentrism. New York: Wiley; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt SD. Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime. The American Economic Review. 1997;87:270–290. [Google Scholar]

- Loncher L, Moretti E. The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrest, and self-reports. American Economic Review. 2003;94:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- Lu JW, Song Y, Shan M. Social trust in subnational regions and foreign subsidiary performance: Evidence from foreign investments in China. Journal of International Business Studies. 2018;49(6):761–773. doi: 10.1057/s41267-018-0148-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luiz JM. Temporal association, the dynamics of crime, and their economic determinants: A time series econometric model of South Africa. Social Indicators Research. 2001;53(1):33–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1007192511126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luiz JM. The impact of ethno-linguistic fractionalization on cultural measures: Dynamics, endogeneity and modernization. Journal of International Business Studies. 2015;46(9):1080–1098. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2015.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton NC, Jiang GF, Escobar LF, Jiménez A. National income inequality and international business expansion. Business and Society. 2020;59(8):1630–1666. doi: 10.1177/0007650318816493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh RM. What have we learned from cross-national research on the causes of income inequality? Comparative Sociology. 2016;15:7–36. doi: 10.1163/15691330-12341376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar U, Rehman F. Diehard or delicate? Violence and young firm performance in a developing country. Business Economics. 2019;54(4):236–247. doi: 10.1057/s11369-019-00137-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merton R. Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review. 1938;3:672–682. doi: 10.2307/2084686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel E, Satyanath S, Sergenti E. Economic shocks and civil conflict: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Political Economy. 2004;112:725–753. doi: 10.1086/421174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J, White DR. Structural cohesion and embeddedness: A hierarchical concept of social groups. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:103–127. doi: 10.2307/3088904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nachum L. Value distribution and markets for social justice in global value chains: Interdependence relationships and government policy. Journal of International Business Policy. 2021;4:1–23. doi: 10.1057/s42214-021-00105-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narula, R., & van der Straaten, K. 2021. A comment on the multifaceted relationship between multinational enterprises and within-country inequality. Critical Perspectives on International Business 17(1): 33–52.

- Neves PC, Silva SMT. Inequality and growth: Uncovering the main conclusions from the empirics. Journal of Development Studies. 2014;50:1–21. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2013.841885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, A. 2004. Income inequality and crime: The case of Sweden. IFAU Working Paper 2004-6, Uppsala, Sweden: University of Sweden.

- North DC. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Noteboom B. Learning by interaction: Absorptive capacity, cognitive distance and governance. Journal of Management and Governance. 2000;4(1–2):69–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1009941416749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, Oh CH. Melting pot or tribe? Country-level ethnic diversity and its effect on subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Policy. 2019;2(1):37–61. doi: 10.1057/s42214-018-00016-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oguzoglu, U., & Ranasinghe, A. 2017. Crime and establishment size: Evidence from South America. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 17(4).

- Papyrakis E, Mo PH. Fractionalization, polarization, and economic growth: Identifying the transmission channels. Economic Inquiry. 2014;52(3):1204–1218. doi: 10.1111/ecin.12070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. What makes democracy work? National Civic Review. 1993;82:101–107. doi: 10.1002/ncr.4100820204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century: The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies. 2007;30:137–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B. 2005. The psychology of looting. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Health/HurricaneKatrina/psychology-looting/story?id=1087898.

- Rufrancos HG, Power M, Pickett KE, Wilkinson R. Income inequality and crime: A review and explanation of the time-series evidence. Social Criminology. 2013;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rygh A. Multinational enterprises and economic inequality: A review and international business research agenda. Critical Perspectives in International Business. 2020 doi: 10.1108/cpoib-09-2019-0068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saridakis, G., Mohammed, A. M., & Sookram, S. 2015. Does crime affect firm innovation? Evidence from Trinidad and Tobago. Economics Bulletin, 35(2): 1205–1215.

- Schotter A, Beamish PW. The hassle factor: An explanation for managerial locational shunning. Journal of International Business Studies. 2013;44(5):521–544. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2013.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava P, Ivanova O. Inequality, corporate legitimacy and the occupy wall street movement. Human Relations. 2015;68:1209–1231. doi: 10.1177/0018726715579523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soares R. Development, crime and punishment: Accounting for the international differences in crime rates. Journal of Development Economics. 2004;73:155–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2002.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soylu S, Sheehy-Skeffington J. Asymmetric intergroup bullying: The enactment and maintenance of societal inequality at work. Human Relations. 2015;68:1099–1129. doi: 10.1177/0018726714552001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]