Abstract

Background

Sexual violence against women remains a global public health problem, with Southeast Asia having among the highest rates of violence victimization globally. Exposure to violence in adolescence--a highly prevalent experience in Vietnam--is associated with later perpetration of violence against others. However, childhood maltreatment as a latent construct is understudied, with most analyses focusing on theoretical categories, potentially missing key patterns of victimization, particularly poly-victimization. Poor understanding of these experience limits researchers’ ability to predict and intervene upon cyclical perpetration of violence. This study aims to identify latent classes of childhood maltreatment, and to test associations between class membership and sexually violent behavior during the first 12 months of university in a sample of Vietnamese men.

Methods and findings

Heterosexual and bisexual men aged 18–24 matriculating into two universities in Hanoi were recruited for the randomized controlled trial of GlobalConsent, a six-module online sexual-violence prevention program. Participants (N = 793) completed a baseline survey, were randomized 1:1 to GlobalConsent or attention control, and were invited to complete post-test surveys at six-months post-baseline and 12-months post-baseline. Validated scales were employed to assess childhood maltreatment and past-six-month sexually violent behavior at each post-test. Latent class analysis identified four classes of childhood maltreatment: Limited-to-no, physical, physical and emotional, and poly-victimization. Associations between childhood maltreatment class and sexually violent behavior demonstrate a threshold effect, wherein poly-victimized men were significantly more likely than men in other classes to have engaged in sexually violent behavior during the 12-month follow-up period.

Conclusions

There is a vital need for screening and intervention with men who have experienced childhood maltreatment in Vietnam to prevent future violence perpetration. Education is needed to break the cycle of violence intergenerationally and in romantic relationships by changing harmful norms around men's sexual privilege and the normalization of childhood maltreatment.

Keywords: Childhood maltreatment, Sexual violence, Latent class analysis, Gender based violence

Highlights

-

•

Exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with later perpetration of violence.

-

•

Sexual violence against women remains a global health concern.

-

•

Latent classes identify patterns of maltreatment associated with later sexual violence.

-

•

Polyvictimization is associated with sexual violence perpetration beyond other latent classes.

-

•

Understanding these associations allows for intervention upon cyclical perpetration of violence.

1. Background

Sexual violence—any sexual act committed against a person without freely given consent (Yount et al., 2020)—is a global public-health problem (García-Moreno et al., 2013). Women are most at risk for victimization due to unequal power dynamics and gender norms (Kalra & Bhugra, 2013). Over one-third of women worldwide are estimated to experience sexual violence in their lifetime (García-Moreno et al., 2013), with substantial regional variation. Rates of sexual violence in most regions of the world, including Asia, have remained stable over the past 25 years (Borumandnia, Khadembashi, Tabatabaei, & AlaviMajd, 2020) despite global commitments to reduce gender inequality and related health outcomes (Gupta et al., 2019; Weber et al., 2019). Southeast Asia has the highest combined lifetime prevalences of physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner or sexual violence by a non-partner, with over 40% of women and girls 15 and older exposed to intimate partner violence, sexual violence, or a combination of the two (García-Moreno et al., 2013). In Vietnam, much of the available literature focuses on the prevalence of IPV and family violence (James-Hawkins et al., 2019, 2021; Le, Morley, Hill, Bui, & Dunne, 2019; Nguyen et al., 2018; Yount et al., 2014), and the extent to which these forms of violence include sexually violent behaviors is unknown. That said, the available data suggest that sexual violence may be common, yet understudied; moreover, the focus of prior studies on specific forms of contact sexual violence has meant that rates of non-contact sexual violence are largely unknown (Pham, 2015; Winzer, Krahé, & Guest, 2019).

Adolescence is a critical developmental period when the risk for exposure to sexual violence is heightened (Bhutta, Yount, Bassat, & Moyer, 2021; Mihalic & Elliott, 1997; Rodenhizer & Edwards, 2017; Wekerle & Wolfe, 1999). Experiences of victimization in adolescence are associated with major adverse physical and mental health outcomes (García-Moreno et al., 2013), and experiences of victimization and perpetration of sexually violent behavior are associated with higher risks of recurrence (World Health Organization, 2010). Several socio-ecological factors influence sexually violent behavior globally and in Vietnam, including the degree to which individuals agree with myths around rape, such as “a woman deserves it,” (Bergenfeld, Lanzas, Trang, Sales, & Yount, 2020) inequitable gender norms (Lewis et al., 2021), and masculine gender norms, which may promote violent behavior (Santana, Raj, Decker, La Marche, & Silverman, 2006). Formative experiences, such as maltreatment in childhood, also have been associated in diverse contexts with the risk of sexually violent behavior (Fitton, Yu, & Fazel, 2020). All forms of child maltreatment are prevalent worldwide, including physical abuse (18%), emotional abuse (26%), sexual abuse (12%), physical neglect (16%), and emotional neglect (18%) (Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink, & van Ijzendoorn, 2012; Stoltenborgh; Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2013; Stoltenborgh; Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn et al., 2013; Stoltenborgh, Van Ijzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011); in Vietnam, prevalences of childhood physical abuse (39%) emotional abuse (50%), and non-specific neglect (25%) have been higher than the global average, whereas reports of sexual abuse (7%) have been lower (Tran, Alink, Van Berkel, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2017). Despite type-specific variation, 83% of Vietnamese adults have reported experiencing any type of childhood maltreatment (Tran, Alink, et al., 2017). Compared to girls in Vietnam, boys are more likely to have experienced sexual or physical maltreatment, but less likely to have experienced emotional abuse or non-specific neglect (Tran, Alink, et al., 2017).

2. Theory

The negative effects of childhood maltreatment are well documented, including neurobiological alterations to brain structures and functions (Teicher & Samson, 2016), adverse psychiatric outcomes and/or emotional dysfunction (Teicher & Samson, 2016; Tran, Van Berkel, van IJzendoorn, & Alink, 2017), and negative health behaviors in adulthood, such as alcohol use and sexual risk taking (Rodgers et al., 2004). Further, behavioral health researchers postulate that exposure to childhood maltreatment operates as social conditioning, creating a cycle of violence wherein individuals who experienced childhood maltreatment themselves perpetrate violence, consistent with Social Learning Theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977; Felson & Lane, 2009). Indeed, there is a documented association between childhood maltreatment exposure and violence perpetration, including sexually violent behavior (Fitton et al., 2020). Alternative causal theories also have been discussed, including the formation of maladaptive attachment styles (Mitchell & Beech, 2011), psychopathy and mental health (Green, Browne, & Chou, 2017), and maltreatment-instigated neurobiological alterations (Siever, 2008).

Although associations between childhood maltreatment and sexually violent behavior are well established, less attention has been paid to the subtypes and intensities of childhood maltreatment, and their potential differential influence on sexually violent behavior (Ford & Delker, 2018). Consistent with Social Learning Theory, the type of childhood maltreatment experienced may affect the type or pattern of sexually violent behavior, with adults replicating the types or patterns they experienced in childhood. Accordingly, researchers have focused on theoretical categories of childhood maltreatment (physical maltreatment, emotional maltreatment, sexual maltreatment, physical neglect, emotional neglect), but relationships with violence perpetration have been inconsistent (Brennan, Borgman, Watts, Wilson, & Swartout, 2020; Casey et al., 2017; Duke, Pettingell, McMorris, & Borowsky, 2010; Ford & Delker, 2018; Fulu et al., 2017). Most theoretical assessments exclude poly-victimization, or experiencing four or more types of childhood maltreatment (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007), as a maltreatment subclass. The experience of poly-victimization may be a unique childhood maltreatment profile and may result in adverse outcomes beyond that of specific types of maltreatment in childhood (Finkelhor et al., 2007; Ford & Delker, 2018). Further, the assessment of childhood maltreatment often is conducted using inventory or count measurements, as might be considered measures of “breadth” or “depth” of childhood maltreatment (Ford & Delker, 2018), resulting in incomplete profiles of victimization (Finkelhor et al., 2007).

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) is a person-centered analytic method to identify unobserved, or latent, qualitative groups or patterns among participants (Ford & Delker, 2018). Generally, LCA is used among populations that have outwardly similar characteristics, with underlying heterogeneity that is not observable, but which may be identified through mixture modeling of a series of observed variables (Weller, Bowen, & Faubert, 2020). Underlying LCA is the assumption that membership in the identified classes can explain patterns of an outcome (Weller et al., 2020). In the limited number of applications of LCA to measures of childhood maltreatment, researchers have identified patterns of distinct single and combined exposures to maltreatment subtypes, supporting the existence of latent classes beyond theoretical groupings of manifest, or observable, variables (Brown et al., 2019; Charak, Villarreal, Schmitz, Hirai, & Ford, 2019; Davis et al., 2018; Ziobrowski et al., 2020). As such, use of LCA is appropriate for identification of qualitatively different classes of childhood maltreatment experiences. Knowledge of the association of class membership with violence perpetration can offer meaningful insights into the impacts of childhood maltreatment, the importance of early, tailored interventions for social learning, and the prevention of cyclically violent behavior through effective interventions with adults who have particular histories of childhood maltreatment.

The current study aims to identify latent classes of childhood maltreatment, and to assess the association of childhood maltreatment latent class membership with sexually violent behavior during the first 12 months of university in a cohort of university men in Vietnam, guided by Social Learning Theory. We explored the following a priori hypotheses:

-

1.

Distinct latent classes of childhood maltreatment will be observed, including limited-to-no maltreatment, co-occurrence of maltreatment types, and poly-victimization (experience of four or more maltreatment types).

-

2.

Differences in sexually violent behavior will be observed by childhood maltreatment latent-class membership.

-

3.

Poly-victimization will be more strongly, positively associated with all forms of sexually violent behavior than limited-to-no exposure to child maltreatment.

3. Material and methods

Participants in this analysis were recruited for enrollment in a double-blind randomized controlled trial of a sexual violence prevention program, GlobalConsent, which is described elsewhere (Yount et al., 2020). All study procedures were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00099860) and Hanoi University of Public Health (017–384/DD-YTCC).

3.1. Setting

The study was carried out in two universities in Hanoi. The first university was a 120-year-old state university which provides training on the health professions and enrolls annually about 1000 students, of whom 40% are men. The second university was a 30-year-old private university that enrolls 2000 students each year for training on different disciplines, of whom about one-third are men.

3.2. Sample eligibility and recruitment

A total of 1017 male students who were enrolled as first-year students across the two universities were invited to attend an orientation session on GlobalConsent. In total, 812 of 1017 invited students attended. Among attendees, three indicated they did not meet the inclusion criteria (identifying as homosexual, 18–24 years old), and seven refused to participate in the program, primarily due to not being enrolled in classes at the time of recruitment. The remaining 802 participants completed baseline visits and enrollment in the GlobalConsent Trial.

3.3. Randomization and masking

After enrollment, nine other participants were found to be ineligible and were not re-contacted, yielding 793 participants who were randomly assigned to either GlobalConsent or attention control (AHEAD) groups at a 1:1 ratio. Participants were assigned a number using a random number generated in Microsoft Excel. Participants’ numbers were sorted in order from 1 to 793; the first 397 men were assigned to the attention-control group, and the remaining men (n = 396) were assigned to the GlobalConsent group (Yount et al., 2020). Study arm assignment (intervention or attention-control) was blinded to the PI, study analyst, and participants during the data collection period; data collection staff were not blinded. Post-randomization, six participants declined to complete the intervention modules (four GlobalConsent, two AHEAD).

3.4. Fieldwork preparation and data collection

A team of 3 research assistants, the PI, and the co-I developed the study questionnaires (Baseline, six-month, and 12-month) in English. The forms, then, were translated into Vietnamese, and the Co-PI reviewed them to standardize the critical terms in Vietnamese. The translated questionnaires were pilot-tested in a group of male university students in Hanoi, and group discussions were hosted to obtain feedback for revisions. The revised baseline surveys were uploaded to Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Harris et al., 2009) for testing, and difficult terms or questions were back-translated into English for discussion in the research team. Final revisions were made to facilitate comprehension in Vietnamese.

Baseline study visits occurred at two study sites in September 2019, at which time students provided written informed consent, and completed self-administered surveys on tablets using the REDCap Mobile App (Harris et al., 2009). Participants were compensated 100000 VND (about 4.00 USD) upon completion of the baseline visit and survey. The intervention is described in detail elsewhere (Yount et al., 2020). In brief, intervention participants were invited to complete six web-based educational modules on sexual violence and prosocial bystander behavior. Those who accessed the intervention modules were invited to complete a post-test one survey (six months after baseline; three months after intervention), and those who did not decline to complete post-test one were invited to complete a post-test two survey (12 months after baseline; nine months after intervention). Participants were compensated 150000 VND (about 6.00 USD) for follow-up surveys, which occurred in March–April 2020 (N = 751) and October–December 2020 (N = 739), for an overall retention rate of 93%. In the GlobalConsent group, 374 students completed post-test one and 364 students completed post-test two. In the AHEAD group, 377 and 375 students completed post-tests one and two, respectively; thus, across both groups and timepoints, retention exceeded 91%. Due to COVID-19 lockdowns, follow-up surveys were conducted via anonymous REDCap survey, for which consent was taken electronically. These follow-up surveys were linked to baseline data using a unique ID number.

3.5. Measures

3.5.1. Sexually violent behavior outcome

We administered a modified Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Oros, 1982) at baseline, six months post-baseline, and 12-months post-baseline to asses sexually violent behavior in the prior six months. The measure has been validated in a variety of contexts (Abbey, Helmers, Jilani, McDaniel, & Benbouriche, 2021; Anderson, Cahill, & Delahanty, 2017; Cecil & Matson, 2006; Krahé, Reimer, Scheinberger-Olwig, & Fritsche, 1999), though not specifically in Vietnam. However, as noted above, the translated measure was piloted for acceptability and relevancy. At each occasion, participants were asked about the frequency (never, once, twice, three or more times) with which they had engaged in each of 10 non-contact sexually violent behaviors, such as sending unsolicited sexual photographs, in the prior six months. They also reported the frequency with which they used each of five tactics to perpetrate each of seven contact sexually violent behaviors (35 tactic/behavior pairs total), such as unwanted touching and attempted or completed rape, in the prior six months. Contact acts involved physical contact with the victim, while non-contact acts do not. Data with respect to all 45 items (10 non-contact sexually violent behaviors, 35 pairs of contact sexually violent behaviors and the tactic used to accomplish them) at post-tests one and two were combined to capture sexually violent behavior in the 12-month follow-up period, during the students’ first year at university. For the primary outcomes, responses were dichotomized to at least one act versus no acts of any sexually violence behavior, based on outcomes for which the study was powered; for analyses of supplementary outcomes, responses were dichotomized into at least one act versus no acts for each (1) contact sexually violent behaviors, (2) non-contact sexually violent behaviors using physical tactics, and (3) non-contact sexually violent behavior using non-physical tactics. The full instruments have been published elsewhere (Yount et al., 2020).

3.5.2. Childhood maltreatment exposure

We administered a child maltreatment module at 12-month follow-up based on a measure used previously and validated in Vietnam (Tran, Alink, et al., 2017). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had ever experienced each of 28 acts of physical, sexual, and emotional maltreatment, including physical and emotional neglect, perpetrated by an adult, before the age of 18. Example items were as follows: “pushing, grabbing, or shoving you, or throwing something at you” for physical maltreatment, “exposed their genitals to you” for sexual maltreatment, “insult you” for emotional maltreatment, “did not show you affection” for emotional neglect, and “did not take care of you when you were sick” for physical neglect. The full instruments have been published elsewhere (Yount et al., 2020).

3.5.3. Covariates

Finally, we collected demographic information at baseline on age in years, living situation (with parents, in a dormitory, other), gender affinity—a measure of self-identification with degree of masculinity or femininity, within male gender identity (feminine or androgynous, somewhat masculine, masculine, very masculine)- sexual orientation (bisexual, heterosexual), religion (any, none), romantic relationship history (any, none), ethnicity (majority Kinh, minority), university (University one, University two), and length of residence in Hanoi (one year or more, less than one year).

3.6. Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics and univariate statistics were computed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, 2013). Classes of childhood maltreatment were defined using latent class analysis (LCA), a person-centered analytic strategy that allows for the identification of classes or patterns of exposure (Collins & Lanza, 2009), in this case, exposure to childhood maltreatment. In LCA, mixture models are used to group participants with similar response patterns into mutually exclusive groups, or classes. Missingness in the data was minimal. We employed full information maximum likelihood estimation, which allows the analyst to use available data for all participants (Enders, 2001). We ran a series of fixed-effects latent class models in MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998), beginning with three classes and adding one class per successive model until theory and model fit statistics indicated no further improvement. A starting value of three latent classes was based on theory and evidence about the likely minimum number of childhood maltreatment latent classes. In line with recent thinking regarding the assumption of local independence in LCA, we decided to allow violation of the assumption of local independence to capture better an accurate and interpretable model (Reboussin, Ip, & Wolfson, 2008). Assuring local independence can result in overly simplified and biased models (Oberski, 2016; Reboussin et al., 2008), particularly when a set of behaviors or experiences are likely to be associated (as is the case with violence victimization). Furthermore, while local independence could be improved by adding an additional class (Suppes & Zanotti, 1981), we found the additional class to lack theoretical meaning, risking the class being spurious. The best-fitting model was determined using the Akaike information criteria (AIC), sample size adjusted BIC (aBIC), Bayesian information criteria (BIC), Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test, entropy, and the theoretical significance and meaningfulness of distinct classes, with consideration for parsimony and interpretability (Weller et al., 2020).

Childhood maltreatment latent-class-membership data were imported into SAS version 9.4. Bivariate associations between demographic characteristics, sexually violent behavior, and latent class membership were computed using t-tests, chi-squared tests, and one-way ANOVA, to understand better differences in latent class characteristics; limited cell sizes limit the statistical meaningfulness of differences between some groups. We used the GENMOD function with robust standard errors to perform binary logistic regressions of childhood maltreatment latent class membership on any sexually violent behavior (the primary analysis) and on subtypes of sexually violent behavior (non-contact sexually violent behavior, contact sexually violent behavior using physical tactics, contact sexually violent behavior using non-physical tactics; supplementary analyses) during the 12-month follow-up period. Outcomes for the supplementary analyses were derived from the Sexual Experiences Survey, as described above, and integrated to examine sexually violent behavior in more detail; however, the reduced disaggregated incidence and corresponding reduced statistical power should be considered. For each outcome, logistic regression models with and without theoretically important covariates (Lee, 2014) (continuous age in years, living situation, gender affinity, sexual orientation, religion, romantic relationship history, ethnicity, treatment versus control arm of the parent RCT, university, and length of residence in Hanoi) were estimated. In both sets of models, we performed post-estimation pairwise tests for differences in estimated coefficients for childhood maltreatment class. The threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Sample characteristics

Participants had an average age of 18.06 (SD: 0.39), and most identified as heterosexual (95.53%) and of the majority Kinh ethnicity (95.65%) (Table 1). A majority of students had not previously been in a romantic relationship (54.3%), were living somewhere other than on campus or with their parents (53.59%), and had lived in Hanoi at least one year (52.23%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of men matriculating to two universities in Vietnam in September 2019 (N = 739).

| Variable | Of Total |

|---|---|

| University, N (%) | |

| University 1 | 341 (46.14) |

| University 2 | 398 (53.86) |

| Age, M (SD) | 18.06 (0.39) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |

| Majority (Kinh) | 703 (95.65) |

| Minority | 32 (4.35) |

| Sexual orientation, N (%) | |

| Heterosexual | 706 (95.53) |

| Bisexual | 33 (4.47) |

| Religion, N (%) | |

| Any | 128 (17.32) |

| None | 611 (82.68) |

| Relationship status, N (%) | |

| Ever in a romantic relationship | 336 (45.47) |

| Never in a romantic relationship | 403 (54.53) |

| Living situation, N (%) | |

| With parents | 225 (30.45) |

| Dormitory/on campus | 118 (15.97) |

| Other/Don't know | 396 (53.59) |

| Lived in Hanoi at least one year, N (%) | |

| Yes | 386 (52.23) |

| No | 353 (47.77) |

| Gender Affinity | |

| Feminine or Neutral | 79 (10.69) |

| Somewhat Masculine | 46 (6.22) |

| Masculine | 341 (46.14) |

| Very Masculine | 273 (36.94) |

| Intervention Arm | |

| [blinded for review] | 364 (49.26) |

| [blinded for review] | 375 (51.44) |

4.2. Latent classes of childhood maltreatment

A four-class latent class model of childhood maltreatment was selected for differentiation of qualitatively different classes with adequate distribution and fit, with emphasis on BIC as the most reliable fit statistic (Weller et al., 2020), while maintaining parsimony and theoretical interpretability (Weller et al., 2020) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Latent class analysis of childhood maltreatment among men matriculating to two universities in Vietnam in September 2019 (N = 739).

| 3-Class Model | 4-Class Model | 5-Class Model | 6-Class Model | 7-Class Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Free Parameters | 86 | 115 | 144 | 173 | 202 |

| Log Likelihood | −7887.597 | −4658.616 | −4541.945 | −4446.264 | −4372.647 |

| AIC | 9941.194 | 9547.233 | 9371.89 | 9238.527 | 9149.294 |

| BIC | 10337.25 | 10076.842 | 10035.053 | 10035.244 | 10079.564 |

| aBIC | 10064.169 | 9711.677 | 9577.802 | 9485.908 | 9438.144 |

| Entropy | 0.953 | 0.914 | 0.926 | 0.940 | 0.937 |

| Average Latent Class Probabilities for Most Likely Latent Class Membership | 0.989; 0.959; 0.987 | 0.989; 0.950; 0.976; 0.908 | 0.952; 0.996; 0.981; 0.975; 0.913 | 0.940; 0.998; 0.997; 0.971; 0.980; 0.960 | 0.991; 0.994; 0.920; 1.000; 0.928; 0.946; 0.965 |

| Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test | 799.522 | 451.961 | 232.224 | 191.23 | 146.953 |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.0028 | 0.0128 | 0.0008 | 0.7608 |

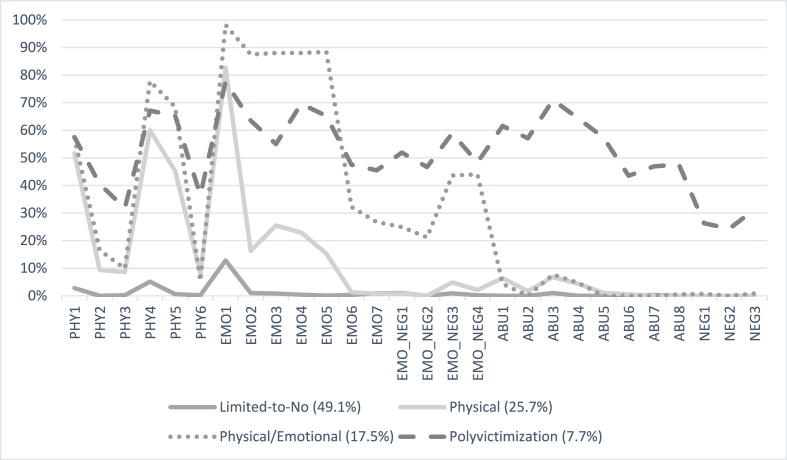

Participants were assigned class membership based on the highest latent class probability (i.e., the probability of membership in a given class). Latent classes were given labels corresponding to the observed patterns of childhood maltreatment: Limited-to-no Maltreatment (less than 5% of participants experienced 26 out of the 28 acts), primarily Physical Maltreatment, primarily Physical and Emotional Maltreatment, and four or more types of maltreatment, Poly-victimization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Childhood Maltreatment Latent Variable Four-Class Solution

PH: Physical maltreatment; EMO: Emotional maltreatment; EMO_NEG: Emotional Neglect; SEX: Sexual maltreatment; PH_NEG: Physical neglect.

Latent classes were qualitative different demographically. Most often (49.12%), students had membership in the limited-to-no childhood maltreatment class, followed by the primarily physical maltreatment class (25.71%), primarily physical and emotional maltreatment class (17.46%), and finally, the poly-victimization class (7.71%). Table 3 presents the distribution of demographic characteristics by child maltreatment latent class membership. University attended and self-identified degree of masculinity were significantly different across classes, though small cell sizes limit the power of this analysis.

Table 3.

Characteristics of men matriculating to two universities in Vietnam in September 2019 (N = 739).

| Variable | By Childhood Maltreatment Latent Class Membership |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited/No Maltreatment | Physical Maltreatment | Physical/Emotional Maltreatment | Poly-victimization | p-value | |

| Of Total | 363 (49.12) | 190 (25.71) | 129 (17.46) | 57 (7.71) | – |

| University, N (%) | |||||

| University 1 | 155 (45.45) | 98 (28.74) | 68 (19.94) | 20 (5.87) | 0.029 |

| University 2 | 208 (52.26) | 92 (23.12) | 61 (15.33) | 37 (9.30) | |

| Age, M (SD) | 18.06 (0.41) | 18.03 (0.18) | 18.14 (0.58) | 18.02 (0.13) | 0.074 |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| Majority (Kinh) | 342 (48.53) | 183 (26.03) | 124 (17.64) | 54 (7.68) | 0.869 |

| Minority | 18 (56.25) | 7 (21.88) | 5 (3.88) | 2 (3.75) | |

| Sexual orientation, N (%) | |||||

| Heterosexual | 353 (50.0) | 181 (25.64) | 119 (16.86) | 53 (7.51) | 0.084 |

| Bisexual | 10 (30.30) | 9 (27.27) | 10 (30.30) | 4 (12.12) | |

| Religion, N (%) | |||||

| Any | 74 (57.81) | 24 (18.75) | 18 (14.06) | 12 (9.38) | 0.076 |

| None | 289 (47.30) | 166 (27.17) | 111 (18.17) | 45 (7.36) | |

| Relationship status, N (%) | |||||

| Ever in a romantic relationship | 167 (49.70) | 82 (24.40) | 60 (17.86) | 27 (8.04) | 0.899 |

| Never in a romantic relationship | 196 (48.94) | 108 (26.80) | 69 (17.12) | 30 (7.44) | |

| Living situation, N (%) | |||||

| With parents | 98 (43.56) | 62 (27.56) | 50 (22.22) | 15 (6.67) | 0.128 |

| Dormitory/on campus | 58 (49.15) | 26 (22.03) | 21 (17.80) | 13 (11.02) | |

| Other/Don't know | 207 (52.27) | 102 (25.76) | 58 (14.65) | 29 (7.32) | |

| Lived in Hanoi at least one year, N (%) | |||||

| Yes | 166 (47.03) | 94 (26.63) | 64 (18.13) | 29 (8.22) | 0.748 |

| No | 197 (51.04) | 96 (24.87) | 65 (16.84) | 28 (7.25) | |

| Gender Affinity, N (%) | |||||

| Feminine or Neutral | 26 (32.91) | 24 (30.38) | 19 (24.05) | 10 (12.66) | <0.001 |

| Somewhat Masculine | 17 (36.96) | 14 (30.43) | 11 (23.91) | 4 (8.7) | |

| Masculine | 153 (44.87) | 96 (28.15) | 72 (21.11) | 20 (5.87) | |

| Very Masculine | 167 (61.17) | 56 (20.51) | 27 (9.89) | 23 (8.42) | |

| Intervention Arm, N (%) | |||||

| [blinded for review] | 180 (49.45) | 88 (24.18) | 73 (10.05) | 23 (6.32) | 0.154 |

| [blinded for review] | 183 (48.80) | 102 (27.20) | 56 (14.93) | 34 (9.07) | |

4.3. Bivariate analysis of sexually violent behavior by latent classes of childhood maltreatment

In bivariate analyses of sexually violent behavior by latent class of childhood maltreatment, students who had experienced poly-victimization reported sexually violent behavior during the 12-month follow-up period more often than did students in other classes of child maltreatment. This pattern was observed for any sexually violent behavior, contact sexually violent behavior, contact sexually violent behavior using physical tactics, and contact sexually violent behavior using non-physical tactics (all p < 0.001) (Table 4). Among students with membership in the not-to-low childhood maltreatment class, physical maltreatment class, and physical/emotional maltreatment class, between 28.72% and 33.29% reported any sexually violent behavior during the first 12 months of university, compared to 72.73% of students in the poly-victimization class.

Table 4.

Sexually violent behavior in the first 12 Months of university, by childhood maltreatment latent class membership, men matriculating to two universities in Vietnam in September 2019 (N = 739).

| Childhood Maltreatment Latent Classes | Sexually Violent Behavior During the First 12 Months of University, N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Sexually Violent Behavior (SVB)a | Non-Contact SVBa | Contact SVB Using Physical Tacticsa | Contact SVB Using Non-Physical Tacticsa | |

| Total |

247 (34.31) |

178 (24.09) |

82 (11.40) |

122 (17.11) |

| Limited-to-No Maltreatment (N = 363) | 114 (32.29) | 75 (20.66) | 10 (11.27) | 60 (17.00) |

| Physical Maltreatment (n = 190) | 54 (28.72) | 42 (22.11) | 10 (5.41) | 18 (9.84) |

| Physical and Emotional Maltreatment (n = 129) | 39 (31.45) | 33 (25.58) | 6 (4.84) | 14 (11.29) |

| Poly-victimization (n = 57) | 40 (72.73) | 28 (49.12) | 26 (47.27) | 30 (56.60) |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Row percentages are not mutually exclusive.

4.4. Regression analysis of childhood maltreatment latent class and sexually violent behavior

In regression models with covariates, compared to all other classes, poly-victimization class membership was associated with significantly higher odds of perpetrating sexually violent behavior during the 12-month follow-up period (Table 5). Compared to students in the limited-to-no maltreatment, primarily physical maltreatment, and primarily physical and emotional maltreatment groups, students in the poly-victimization group had 5.59, 6.62, and 5.81 times the odds of perpetrating sexually violent behavior in the first 12 months of university (all p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons between the remaining classes demonstrated no statistically significant differences in the odds of sexually violent behavior in the 12-month follow-up period.

Table 5.

Odds ratios of any sexually violent behavior by childhood maltreatment latent class membership of men matriculating to two universities in Vietnam in September 2019 (N = 739).

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Reference: Low-to-No Maltreatment | Limited/No Maltreatment | ref | – | – | ref | – | – |

| Physical Maltreatment | 0.85 | 0.57, 1.24 | 0.393 | 0.88 | 0.59, 1.33 | 0.552 | |

| Physical and Emotional Maltreatment | 0.96 | 0.62, 1.49 | 0.863 | 1.03 | 0.65, 1.65 | 0.899 | |

| Poly-victimization |

5.59 |

2.97, 10.54 |

<0.001 |

5.43 |

2.80, 2.35 |

<0.001 |

|

| Reference: Primarily Physical Maltreatment | Limited/No Maltreatment | 1.18 | 0.80, 1.74 | 0.393 | 1.13 | 0.75, 1.70 | 0.552 |

| Physical Maltreatment | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | |

| Physical and Emotional Maltreatment | 1.14 | 0.70, 1.87 | 0.606 | 1.17 | 0.70, 1.95 | 0.557 | |

| Poly-victimization |

6.62 |

3.38, 12.96 |

<0.001 |

6.14 |

3.05, 12.35 |

<0.001 |

|

| Reference: Primarily Physical and Emotional Maltreatment | Limited/No Maltreatment | 1.04 | 0.67, 1.61 | 0.863 | 0.97 | 0.61, 1.55 | 0.900 |

| Physical Maltreatment | 0.88 | 0.54, 1.44 | 0.606 | 0.86 | 0.51, 1.43 | 0.557 | |

| Physical and Emotional Maltreatment | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | |

| Poly-victimization | 5.81 | 2.87, 11.75 | <0.001 | 5.26 | 2.52, 11.01 | <0.001 | |

Adjusted for age, living situation, gender affinity, sexual orientation, religion, romantic relationship history, ethnicity, treatment arm, university, length of residence in Hanoi.

In supplemental analyses (Supplemental Table 1), students in the poly-victimization group showed significantly higher adjusted odds of sexually violent behavior in the first 12 months of university across all types of sexually violent behavior (non-contact, contact using physical tactics, contact using non-physical tactics). Interestingly, students in the limited-to-no maltreatment group had approximately 2.5 times the odds of reporting contact sexually violent behaviors using physical tactics compared to those in the physical maltreatment group and the physical and emotional maltreatment group, while students in the limited-to-no maltreatment group were almost twice as likely to report contact sexually violent behavior using non-physical tactics compared to the physical maltreatment group.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings and interpretation

This analysis is the first to identify latent classes of childhood maltreatment and to assess their associations with sexually violent behavior, overall and by type, in a large representative sample of men attending university in Vietnam. Findings reveal distinct patterns of childhood maltreatment experiences among sample participants. Specifically, having limited-to-low exposure to childhood maltreatment (49.12%), exposure primarily to physical maltreatment (25.71%), exposure primarily to physical and emotional maltreatment (17.46%), and poly-victimization (exposure to four or more types of maltreatment, 7.71%) corresponded to mutually exclusive classes based on membership probability, supporting existing literature proposing distinct childhood maltreatment sub-classes beyond single-maltreatment type theoretical categories. This finding supports the use of LCA to identify latent classes that are qualitatively different from theoretically determined (a priori) childhood maltreatment classifications. However, the latent classes of childhood maltreatment identified in this analysis differ from those that have been identified previously using LCA (Brown et al., 2019; Charak et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2018; Ziobrowski et al., 2020). Regressions predicting sexually violent behavior in the 12-month follow-up period by class membership demonstrated a lack of a dose-response relationship between childhood maltreatment class and sexually violent behavior. Instead, findings corroborated a significant threshold effect of poly-victimization on the risk of sexually violent behavior as first-year university students. This threshold effect was observed in comparison to all other latent classes of exposure to childhood maltreatment. Of note, the poly-victimization class was the only class that commonly reported exposure to childhood sexual maltreatment. Given the significant association with between poly-victimization and sexually violent behavior, it is possible that exposure to sexual childhood maltreatment is a predisposing factor for later sexually violent behavior, rather than poly-victimization; however, this specific relationship cannot be teased out due to the common co-occurrence of sexual maltreatment and other forms of childhood maltreatment in this sample. Prior research has documented conflicting associations between childhood sexual abuse and sexual IPV (Fulu et al., 2017) and dating violence (Duke et al., 2010), and no associations between sexual violence or poly-victimization and sexual abuse (Davis et al., 2018). Hence, further research on these profiles is needed to understand better the potential effects of childhood sexual maltreatment as distinct from poly-victimization. Finally, supplementary analyses revealed the unexpected finding of increased odds of contact sexually violent behavior among those who experienced limited-to-no maltreatment compared to those who experienced physical maltreatment (significant for both physical and non-physical tactics) and physical and emotional maltreatment (significant for only physical tactics). In contrast, poly-victimization was significantly associated with all sexually violent behaviors. It may be that exposure to sexual maltreatment in childhood, as potentially experienced by those in the poly-victimization class, is the factor influencing increased odds of violence perpetration, explaining why those in the physical and physical-emotional maltreatment class do not have increased odds of sexually violent behavior. There also may be contextual factors unaddressed in the current analysis, including exposure to sexually explicit material (Bergenfeld, Cheong, Minh, Trang, & Yount, n.d., Miller, Jones, & McCauley, 2018), or psychological and physiological compensation from the effects of childhood maltreatment (Teicher & Samson, 2016).

Over half of the men in the sample reported more than limited or no childhood maltreatment, and 33% reported sexually violent behavior in their first year of university, indicating a high burden of violence victimization and perpetration in the sample, respectively. The context of Vietnam provides unique factors that may influence the perpetration of childhood maltreatment and sexually violent behavior. Some authors have suggested that the recent history of the Vietnam War may have set a standard of tolerance for violence for the generation of parents with children now in young adulthood, shifting social norms for enacting violence against children, and reinforcing acceptance of violence among the same children (Tran, Alink, et al., 2017). Compounding this contextual factor, unequal power dynamics are pervasive between elders and children (Rydstrøm, 2006) and between men and women (Horton & Rydstrom, 2011), normalizing childhood maltreatment and gender-based violence, respectively. These dynamics may be sustained by restrictive gender norms embedded in Confucianism (Park & Chesla, 2007), as well as philosophies that are considered to be imported from the West (Rydstrøm, 2010). Consideration for and integration of such cultural factors into efforts to mitigate violence exposure and perpetration is vital, while they also may serve as entry points for promotion of anti-violence movements.

5.2. Limitations and strengths

The findings of this study are subject to some limitations; however, substantial efforts were invested to mitigate these threats and, thereby, to maintain the validity of the results. First, young adult men were recruited from two universities in Hanoi, so the sample may not be generalizable to university men across Vietnam. Still, we intentionally chose one private university and one public university to ensure that the sample included diverse men coming from many regions in Vietnam. Due to the focus of the parent study-testing an adaptation of a male-to-female sexual violence prevention program intended for young adult men-we were unable to consider the important topic of violence among gender and sexual minorities, which is pervasive globally (Blondeel et al., 2018), including in Vietnam (Hershow et al., 2021). This includes sexual violence against women by other women, or by men who do not identify as sexually attracted to women (homosexual/gay). However, the majority of sexual violence against women is perpetrated by men (García-Moreno et al., 2013), and available evidence notes that men identifying as “mostly heterosexual” and bisexual are more likely to perpetrate violence than men identifying as "homosexual” (Swiatlo, Kahn, & Halpern, 2020). Third, exposure to childhood maltreatment was retrospectively self-reported, indicating the potential for recall and response bias, particularly with the possibility of repression of childhood maltreatment; the team addressed this limitation by using an instrument to measure childhood maltreatment that was validated in Vietnam (Tran, Alink, et al., 2017). Relatedly, the risk of underreporting sexually violent behavior was present but may similarly have been mitigated with the use of a self-administered survey and the use of the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss & Oros, 1982). Both the childhood maltreatment measure and Sexual Experiences Survey use multiple, behaviorally-specific items to capture experiences, which improves content validity (Diamantopoulos, Sarstedt, Fuchs, Wilczynski, & Kaiser, 2012), and tends to stimulate recall and reduce under-reporting (Khare & Vedel, 2019). Moreover, self-administration of the questionnaire allowed for greater privacy, which may have enhanced disclosure of potentially sensitive or shameful experiences (Okamoto et al., 2002). Despite these efforts, the potential for biased reporting may not be fully mitigated; however, under such circumstances, our findings may provide a lower bound for the effects of childhood maltreatment class on sexually violent behavior. Third, the observational (non-randomized) nature of this analysis limited our ability to make causal inferences of the effects of child maltreatment on sexually violent behavior; however, we attempted to mitigate this limitation by using a validated childhood maltreatment questionnaire, robust estimation of membership in childhood maltreatment exposure groups using latent class analysis, and adjustment for potential confounders. Despite the disruption of COVID-19-related school closures and lockdowns, our use of a secure, web-based survey platform allowed us to continue data collection without interruption. Still, estimated rates of sexually violent behavior may have been affected by interrupted contact with female students during COVID-19-related school closures, resulting in lower rates of sexually violent behavior during the study period than would have been observed in the absence of COVID-19. Finally, other pathways may contribute to the relationship between childhood maltreatment and sexually violent behavior in adulthood, such as physiological changes to brain structure and functioning (Teicher & Samson, 2016). There also may be more nuanced qualitative classifications within the “poly-victimization” class, which are not bound by number of childhood maltreatment types, but associated factors such as severity and frequency. These possibilities should be elucidated further by cohort studies in the region.

5.3. Implications for research and policy

Results from this study underscore the need to screen for childhood maltreatment and especially poly-victimization among adolescent men. Identification of childhood maltreatment is key to interruption of ongoing maltreatment and cycles of violence, with teachers and school administrators potentially serving as responsible reporters. Educational professionals could be trained to identify childhood maltreatment in primary and secondary school, as well as be aware of sequalae displayed in university settings that may place individuals at risk of harm to themselves or others. Similarly, pediatric and health services could be prepared to screen and to identify priority risk groups for intervention- likely those who have experienced or are experiencing poly-victimization- to provide support services in childhood and adulthood. Latent class analysis provides a way to identify a small set of underlying subgroups characterized by multiple dimensions which could, in turn, be used to examine differential intervention effects. The results of this analysis could help target future intervention resources to subgroups for tailored interventions (Lanza & Rhoades, 2013). Appropriate intervention with these groups, such the GlobalConsent intervention, may mitigate the risk of sexual violence on university campuses. Survivor-centered services may help adolescent men to process trauma associated with childhood maltreatment, lessening the likelihood of perpetrating sexual violence. Educating students before leaving university on healthy parenting and the long-term negative impacts of childhood maltreatment on children, and implementation of governmental policies disincentivizing childhood maltreatment of may lower the risk of exposure to childhood maltreatment in future generations, disrupting “cycles of violence” across generations and in dating relationships. In settings lacking robust resources for intervention and support services, identification of childhood maltreatment experiences most associated with adulthood harm to others, through screening, allows for targeting of resources to populations most in need. Further, while screening requires resources, the burden of childhood maltreatment in Southeast Asia has a significant economic cost, of approximately 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) (UNICEF, 2015); domestic violence, which includes some forms of sexual violence, is responsible for loss of an additional 1.8% of GDP (UN Women, 2012). Cost-effectiveness analyses may provide further insight into the cost efficiency of screening in Vietnam, as has been conducted for other health outcomes (Nguyen et al., 2013). Beyond educational and preventative programming, results indicate a need for engagement in policy on prevention of both childhood maltreatment and sexual violence. Vietnam has taken a preventative policy approach towards domestic violence in recent years, though with unknown effectiveness and barriers to implementation (Le et al., 2019). Should these efforts prove effective, policy around childhood maltreatment and sexual violence beyond intimate partnerships could be modeled after this policy. More broadly, advancement of gender equity and health require efforts to shift harmful norms that normalize parental maltreatment of children, men's sexual privilege, and violence more generally are required for violence reduction. Additional research also is needed to understand the impact of childhood maltreatment on violence among dyadic relationships that are not male-female, particularly given high rates of violence against gender and sexual minorities (Blondeel et al., 2018), including in Vietnam (Hershow et al., 2021). This should include tailoring of sexual violence prevention programs to different sexual and gender identity minority populations, and understanding how childhood maltreatment is classified and related to sexually violent behavior in late adolescent and early adulthood among these populations. Routine screening and intervention may reinforce the norm that childhood maltreatment and sexually violent behavior are negative outcomes, facilitating shifts away from perceptions that these behaviors are normal or acceptable. In the near future, more research is needed to understand the unique impacts of childhood maltreatment poly-victimization with the full range of outcomes in young adulthood.

Funding

Anonymous charitable foundation (PI Yount).

Author CRediT roles

KMA: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

IB: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing;

YFC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- Editing and Reviewing.

THM: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Investigation, Project Administration, Writing- Editing and Reviewing.

KMY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing- Editing and Reviewing.

Ethical statement

All study procedures were approved by Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00099860) and the Hanoi University of Public Health (017–384/DD-YTCC). Funding was provided by an anonymous charitable foundation (PI Yount). The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dang Hong Linh, Nguyen Phuong Thao, and Le Thu Giang for assistance to the Center for Creative Initiatives in Health and Population (CCIHP) in project implementation. The authors also thank the universities that agreed to be study sites and all study participants and volunteers, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101103.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abbey A., Helmers B.R., Jilani Z., McDaniel M.C., Benbouriche M. Assessment of men's sexual aggression against women: An experimental comparison of three versions of the sexual experiences survey. Psychology of Violence. 2021;11(3):253–263. doi: 10.1037/vio0000378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.E., Cahill S.P., Delahanty D.L. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of the sexual experiences survey-short form perpetration (SES-SFP) in college men. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2017;26(6):626–643. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1330296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A., Walters R.H. Vol. 1. Prentice Hall; 1977. (Social learning theory). [Google Scholar]

- Bergenfeld, I., Cheong, Y.F., Minh, T.H., Trang, Q.T., and Yount, K.M. (n.d.). Effects of exposure to sexually explicit material on sexually violent behavior among first-year university men in Vietnam.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bergenfeld I., Lanzas G., Trang Q.T., Sales J., Yount K.M. Rape myths among university men and women in Vietnam: A qualitative study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020;37(3–4):NP1401–NP1431. doi: 10.1177/0886260520928644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z.A., Yount K.M., Bassat Q., Moyer C.E. Sustainable Developmental Goals interrupted: Overcoming challenges to global child and adolescent health. PLoS Medicine. 2021;18(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeel K., de Vasconcelos S., García-Moreno C., Stephenson R., Temmerman M., Toskin I. Violence motivated by perception of sexual orientation and gender identity: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2018;96(1):29–41L. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.197251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borumandnia N., Khadembashi N., Tabatabaei M., Alavi Majd H. The prevalence rate of sexual violence worldwide: A trend analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09926-5. 1835-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan C.L., Borgman R.A., Watts S.S., Wilson R.A., Swartout K.M. Childhood neglect history, depressive symptoms, and intimate partner violence perpetration by college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020;36(23–24):NP12576–NP12599. doi: 10.1177/0886260519900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Rienks S., McCrae J.S., Watamura S.E. The co-occurrence of adverse childhood experiences among children investigated for child maltreatment: A latent class analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;87:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey E.A., Masters N.T., Beadnell B., Hoppe M.J., Morrison D.M., Wells E.A. Predicting sexual assault perpetration among heterosexually active young men. Violence Against Women. 2017;23(1):3–27. doi: 10.1177/1077801216634467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecil H., Matson S.C. Sexual victimization among African American adolescent females: Examination of the reliability and validity of the Sexual Experiences Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(1):89–104. doi: 10.1177/0886260505281606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charak R., Villarreal L., Schmitz R.M., Hirai M., Ford J.D. Patterns of childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence, emotion dysregulation, and mental health symptoms among lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults: A three-step latent class approach. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;89:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L.M., Lanza S.T. Vol. 718. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. (Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences). [Google Scholar]

- Davis K.C., Masters N.T., Casey E., Kajumulo K.F., Norris J., George W.H. How childhood maltreatment profiles of male victims predict adult perpetration and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33(6):915–937. doi: 10.1177/0886260515613345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A., Sarstedt M., Fuchs C., Wilczynski P., Kaiser S. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2012;40(3):434–449. doi: 10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duke N.N., Pettingell S.L., McMorris B.J., Borowsky I.W. Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e778–786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K. A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8(1):128–141. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0801_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felson R.B., Lane K.J. Social learning, sexual and physical abuse, and adult crime. Aggressive Behavior. 2009;35(6):489–501. doi: 10.1002/ab.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R.K., Turner H.A. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitton L., Yu R., Fazel S. Childhood maltreatment and violent outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020;21(4):754–768. doi: 10.1177/1524838018795269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J.D., Delker B.C. Polyvictimization in childhood and its adverse impacts across the lifespan: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2018;19(3):275–288. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2018.1440479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulu E., Miedema S., Roselli T., McCook S., Chan K.L., Haardörfer R., et al. Pathways between childhood trauma, intimate partner violence, and harsh parenting: Findings from the UN multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the pacific. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(5):e512–e522. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno C., Pallitto C., Devries K., Stöckl H., Watts C., Abrahams N. World Health Organization; 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625 [Google Scholar]

- Green K., Browne K., Chou S. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and violence to others in individuals with psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2017;20(3):358–373. doi: 10.1177/1524838017708786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G.R., Oomman N., Grown C., Conn K., Hawkes S., Shawar Y.R., et al. Gender equality and gender norms: Framing the opportunities for health. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2550–2562. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershow R.B., Miller W.C., Giang L.M., Sripaipan T., Bhadra M., Nguyen S.M., et al. Minority stress and experience of sexual violence among men who have sex with men in Hanoi, Vietnam: Results from a cross-sectional study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021;36(13–14):6531–6549. doi: 10.1177/0886260518819884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Rydstrom H. Heterosexual masculinity in contemporary Vietnam: Privileges, pleasures, and protests. Men and Masculinities. 2011;14(5):542–564. doi: 10.1177/1097184X11409362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James-Hawkins L., Hennink M., Bangcaya M., Yount K.M. Vietnamese men's definitions of intimate partner violence and perceptions of women's recourse-seeking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2021;36(13–14):5969–5990. doi: 10.1177/0886260518817790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James-Hawkins L., Salazar K., Hennink M.M., Ha V.S., Yount K.M. Norms of masculinity and the cultural narrative of intimate partner violence among men in Vietnam. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2019;34(21–22):4421–4442. doi: 10.1177/0886260516674941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra G., Bhugra D. Sexual violence against women: Understanding cross-cultural intersections. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;55(3):244–249. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.117139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare S.R., Vedel I. Recall bias and reduction measures: An example in primary health care service utilization. Family Practice. 2019;36(5):672–676. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmz042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M.P., Oros C.J. Sexual experiences survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(3):455. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahé B., Reimer T., Scheinberger-Olwig R., Fritsche I. Measuring sexual aggression: The reliability of the Sexual Experiences Survey in a German sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14(1):91–100. doi: 10.1177/088626099014001006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza S.T., Rhoades B.L. Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science. 2013;14(2):157–168. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.H. Should we adjust for a confounder if empirical and theoretical criteria yield contradictory results? A simulation study. Scientific Reports. 2014;4(1):6085. doi: 10.1038/srep06085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T.M., Morley C., Hill P.S., Bui Q.T., Dunne M.P. The evolution of domestic violence prevention and control in Vietnam from 2003 to 2018: A case study of policy development and implementation within the health system. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2019;13:41. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0295-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P., Bergenfeld I., Thu Trang Q., Minh T.H., Sales J.M., Yount K.M. Gender norms and sexual consent in dating relationships: A qualitative study of university students in Vietnam. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1846078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic S.W., Elliott D. A social learning theory model of marital violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1997;12(1):21–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1021941816102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E., Jones K.A., McCauley H.L. Updates on adolescent dating and sexual violence prevention and intervention. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2018;30(4):466–471. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell I.J., Beech A.R. Towards a neurobiological model of offending. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(5):872–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H., Laohasiriwong W., Stewart J.F., Wright P., Nguyen Y.T.B., Coyte P.C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a screening program for breast cancer in Vietnam. Value in Health Regional Issues. 2013;2(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.H., Ngo T.V., Nguyen V.D., Nguyen H.D., Nguyen H.T.T., Gammeltoft T., et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Vietnam: Prevalence, risk factors and the role of social support. Global Health Action. 2018;11(sup3):1638052. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1638052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberski D.L. Beyond the number of classes: Separating substantive from non-substantive dependence in latent class analysis. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification. 2016;10(2):171–182. doi: 10.1007/s11634-015-0211-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Ohsuka K., Shiraishi T., Hukazawa E., Wakasugi S., Furuta K. Comparability of epidemiological information between self- and interviewer-administered questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55(5):505–511. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Chesla C. Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study. Journal of Family Nursing. 2007;13(3):293–311. doi: 10.1177/1074840707304400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T.T.G. Using education-entertainment in breaking the silence about sexual violence against women in Vietnam. Asian Journal of Women's Studies. 2015;21(4):460–466. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2015.1106858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin B.A., Ip E.H., Wolfson M. Locally dependent latent class models with covariates: An application to under-age drinking in the USA. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 2008;171(4):877–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenhizer K.A.E., Edwards K.M. The impacts of sexual media exposure on adolescent and emerging adults' dating and sexual violence attitudes and behaviors: A critical review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2017;20(4):439–452. doi: 10.1177/1524838017717745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers C.S., Lang A.J., Laffaye C., Satz L.E., Dresselhaus T.R., Stein M.B. The impact of individual forms of childhood maltreatment on health behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(5):575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydstrøm H. Masculinity and punishment: Men's upbringing of boys in rural Vietnam. Childhood. 2006;13(3):329–348. doi: 10.1177/0907568206066355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rydstrøm H. Nias Press; 2010. Gendered inequalities in Asia: Configuring, contesting and recognizing women and men. [Google Scholar]

- Santana M.C., Raj A., Decker M.R., La Marche A., Silverman J.G. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc . SAS Institute Inc; 2013. SAS 9.4. [Google Scholar]

- Siever L.J. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):429–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J., Alink L.R.A., van Ijzendoorn M.H. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2012;21(8):870–890. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2012.708014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J., Van Ijzendoorn M.H. The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(3):345–355. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J., van Ijzendoorn M.H., Alink L.R.A. Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48(2):81–94. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.697165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M., Van Ijzendoorn M.H., Euser E.M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(2):79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppes P., Zanotti M. When are probabilistic explanations possible? Synthese. 1981:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Swiatlo A.D., Kahn N.F., Halpern C.T. Intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among young adult sexual minorities. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2020;52(2):97–105. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher M.H., Samson J.A. Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):241–266. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N.K., Alink L.R., Van Berkel S.R., Van Ijzendoorn M.H. Child maltreatment in Vietnam: Prevalence and cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2017;26(3):211–230. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1250851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N.K., Van Berkel S.R., van IJzendoorn M.H., Alink L.R. The association between child maltreatment and emotional, cognitive, and physical health functioning in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4258-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN Women Estimating the costs of domestic violence against women in Viet Nam. 2012. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2013/2/estimating-the-cost-of-domestic-violence-against-women-in-viet-nam

- UNICEF Estimating the economic burden of violence against children in east Asia and the pacific. 2015. https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/661/file/Economic%20Burden%20of%20Violence%20against%20Children.pdf

- Weber A.M., Cislaghi B., Meausoone V., Abdalla S., Mejía-Guevara I., Loftus P., et al. Gender norms and health: Insights from global survey data. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2455–2468. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30765-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C., Wolfe D.A. Dating violence in mid-adolescence: Theory, significance, and emerging prevention initiatives. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(4):435–456. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller B.E., Bowen N.K., Faubert S.J. Latent class Analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology. 2020;46(4):287–311. doi: 10.1177/0095798420930932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer L., Krahé B., Guest P. The scale of sexual aggression in Southeast Asia: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2019;20(5):595–612. doi: 10.1177/1524838017725312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Preventing IPSV against woman: Taking action and generating evidence. 2010. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564007/en/

- Yount K.M., Minh T.H., Trang Q.T., Cheong Y.F., Bergenfeld I., Sales J.M. Preventing sexual violence in college men: A randomized-controlled trial of GlobalConsent. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09454-2. 1331-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount K.M., Pham H.T., Minh T.H., Krause K.H., Schuler S.R., Anh H.T., et al. Violence in childhood, attitudes about partner violence, and partner violence perpetration among men in Vietnam. Annals of Epidemiology. 2014;24(5):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziobrowski H.N., Buka S.L., Austin S.B., Sullivan A.J., Horton N.J., Simone M., et al. Using latent class analysis to empirically classify maltreatment according to the developmental timing, duration, and co-occurrence of abuse types. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.