Abstract

The functional interactions between opioid and chemokine receptors have been implicated in the pathological process of chronic pain. Mounting studies have indicated the possibility that a MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer may be involved in nociception and related pharmacologic effects. Herein we have synthesized a series of bivalent ligands containing both MOR agonist and CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophores with an aim to investigate the functional interactions between these two receptors. In vitro studies demonstrated reasonable recognition of designed ligands at both respective receptors. Further antinociceptive testing in mice revealed compound 1a to be the most promising member of this series. Additional molecular modeling studies corroborated the findings observed. Taken together, we identified the first bivalent ligand 1a showing promising antinociceptive effect by targeting putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers, which may serve as a novel chemical probe to further develop more potent bivalent ligands with potential application in analgesic therapies for chronic pain management.

Keywords: mu opioid receptor, chemokine receptor CXCR4, bivalent ligand, pain management

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Chronic pain remains an intractable problem in public health due to the considerable medical treatment costs and the loss of productivity in the workplace [1]. While several possible mechanisms have been proposed to account for the pathophysiological changes associated with the development of chronic pain, it is widely accepted that the presence of inflammation at the site of the damaged tissue could be one of the causative factors, in which immunoactive substance can initiate immune responses that lead to the chronic pain condition [2–5].

As major inflammatory mediators, chemokines and their receptors are crucial for the inflammatory response and their overexpression has been shown to contribute to the exacerbation of inflammation in different tissues [6–8]. Moreover, it has recently been discovered that chemokines and their receptors appear to pose effects on opioid receptor function in nociceptive processing [9]. For example, the injection of high doses of CXC motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) into the periaqueductal gray (PAG) region in rats significantly blocked the antinociceptive effect induced by selective mu opioid receptor (MOR) agonist [D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO) [10]. Furthermore, several studies have suggested that CXCL12 is able to reduce morphine-mediated analgesia both in the PAG and spinal cord [11–13]. In addition, although the underlying roles of CXC chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) in pain transduction have not been fully understood, a recent study indicated that it is implicated in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain together with relevant spinal molecular events [14].

On the other hand, aside from the ability to induce analgesia, opioid receptors have been shown to possess immunomodulatory properties due, at least in part, to the modulation of chemokine receptor gene expression. For example, activation of the MOR by DAMGO leads to an increased expression of CXCR4 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [15,16]. Additionally, stimulation of opioid receptors is likely to influence CXCR4 mediated function in neuronal cells. For example, treatment of rat cortical neurons co-expressing MOR and CXCR4 with selective MOR agonists, e.g. morphine or DAMGO, inhibited the expression of CXCR4-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), which is pivotal to maintain peripheral and central sensitization associated with different pain states [17–19]. Altogether, these more recent studies have supported functional crosstalk between the MOR and CXCR4 in pain modulation, and more importantly, they suggested that a novel chemical entity that can activate the MOR while simultaneously antagonizing the CXCR4 may serve as a potent analgesic for treatment of chronic pain without tolerance and other undesired side effects.

As one of hypotheses for the mechanism of crosstalk between the MOR and CXCR4, the formation of MOR–CXCR4 heterodimers has garnered a great deal of interest in recent years. Given that the MOR and CXCR4 were able to form homodimers and heterodimers with other G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [20–25] and the findings that MOR and CXCR4 were co-expressed in cultured cells [26–29], together with reports that these receptors were colocalized in pain-transmitting neuroanatomical structures, including the dorsal root ganglion and the spinal cord dorsal horn [10,30], it seems reasonable to hypothesize that MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers may be involved in at least some of the functional interactions that have been reported previously. As demonstrated in prior studies, bivalent ligands that are able to interact with both receptors simultaneously have been regarded as powerful tools to elucidate the underlying mechanism of GPCR dimerization [29,31], as well as to serve as potential therapeutic agents in treating specific diseases [32,33].

In the past years, our laboratories have developed several selective bivalent ligands with promising pharmacological properties [34–36]. In particular, a bivalent ligand featuring both a MOR and a CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore has been recently identified by us with reasonable recognition to both respective receptors as well as potent inhibition of opioid enhanced HIV-1 invasion [37]. Encouraged by these observations, the present study was initiated using an analogous approach by which a selective MOR agonist, oxymorphone, was connected to a selective CXCR4 antagonist, IT1t, via a spacer of varied lengths. We envisioned that such a combination of agonist and antagonist pharmacophores in a single bivalent ligand could confer potential analgesia on the basis of prior reports [1,38,39]. Herein we firstly report the design and synthesis of a series of a MOR agonist/CXCR4 antagonist bivalent ligands and the characterization of their pharmacological properties both in vitro and in vivo.

Results and Discussion

Bivalent Ligand Rational Design.

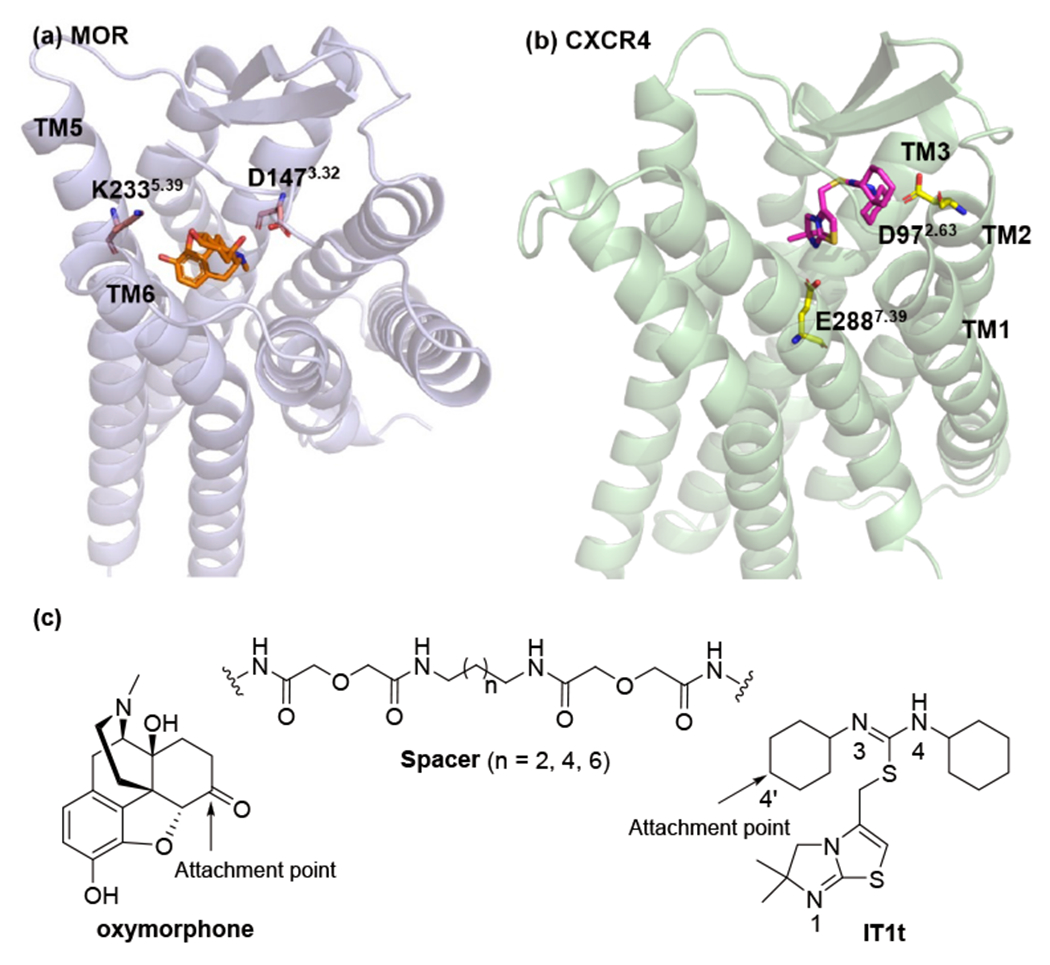

Previous studies have suggested that three key components are pivotal in the rational design of a bivalent ligand, including selection of pharmacophores, designation of suitable attachment points of the spacer, and optimal length and chemical composition of the spacers [42]. Within this context, we commenced our study by utilizing oxymorphone as a selective MOR agonist pharmacophore as it has successfully been incorporated into other bivalent ligands, in which the C6-position of the epoxymorphinan skeleton was usually designated as the attachment point for the spacer [32,33,43,44]. Moreover, the docking pose of oxymorphone in the active MOR showed that its C6-position oriented to the extracellular end of the transmembrane helix 5 (TM5) and TM6 (Figure 2a) . Taken together, the C6-position of oxymorphone was selected as the attachment point to connect the spacer via an amide bond (Figure 2c). As the only ligand that has been co-crystallized with the CXCR4 presently, IT1t has been shown to possess reasonable recognition at the CXCR4 in previous bivalent ligand studies [35, 37] . We therefore decided to choose it as the CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophore in current work by employing its 4′-position on the cyclohexyl ring as the attachment point (Figures 2b, 2c).

Figure 2.

The schematic diagram of designing target bivalent ligands: (a) the binding mode of oxymorphone within the MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M [40]) from docking study; (b) the binding mode of IT1t within the CXCR4 from its crystal structure (PDB ID: 30DU [41]); (c) the designated attachment points and adopted spacers.

As for the spacer, a chain comprised of one alkyldiamine moiety and two diglycolic units was employed. This selection was based on the fact that several previously reported successful bivalent ligands incorporating such a spacer have been demonstrated as potent, long-lasting analgesics in in vivo studies, suggesting its good physicochemical properties including favorable rigidity, high stability and low toxicity. [32,33,44]. Meanwhile, it has been well documented that bivalent ligands targeting GPCR dimers are believed to be bridged by a spacer with a length between 16 to 22 atoms [45, 46]. As such, we incorporated spacers bearing 18, 20 and 22 heavy atoms (compounds 1a–c, Figure 1), respectively, to systematically investigate how the spacer length affects activity. Additionally, the corresponding monovalent ligand controls for both oxymorphone (2a–c) and IT1t (3a–c) pharmacophores were also synthesized for comparison purposes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of oxymorphone, IT1t, designed bivalent ligands (1a–c), monovalent controls (2a–c) and (3a–c).

Chemical Synthesis.

In an effort to introduce the MOR agonist pharmacophore, 6β–oxymorphamine 8 was synthesized through 4 steps as shown in Scheme 1. The synthesis of oxymorphone 6 was accomplished by oxidation of thebaine 4 with performic acid, followed by catalytic hydrogenation and cleavage of the 3- methoxy group [47]. Following a previously described procedure [48], oxymorphone 6 was then subjected to reductive amination and catalytic hydrogenation to give 6β–oxymorphamine 8 in a good yield. The critical intermediate aminomethyl-substituted IT1t was obtained with an acceptable yield through 8 steps according to our previous reported procedures [35]. The synthetic route of bivalent ligands 1a–c and monovalent ligand controls 2a–c and 3a–c were depicted in Scheme 2 and Scheme 3.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 6β–oxymorphaminc 8. Reagents and conditions: (a) i: H2O2, HCOOH, H2SO4; ii: H2, Pd/C MeOH, 2 steps 76%; (b) BBr3, CHCl3, 86%; (c) i: dibenzylamine, p-Toluenesulfonic acid, phenolic acid, toluene; ii NaCNBH3, EtOH, 45%; (d) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 84%.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of bivalent ligands (1a–c). Reagents and conditions: (a) CbzCl, CH2Cl2, MeOH, 1,4-diaminobutane or 1,6-diaminohexane or 1,8-diaminooctane, 22-34%; (b) diglycolic anhydride, THF, 49-96%; (c) 6β-oxvmorphaminc. EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF, 66-74%; (d) H2, MeOH, Pd/C, 83-92%; (e) diglycolic anhydride, DMF, 99-100%; (f) aminomethyl-substituted IT1t, EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF, 32-49%.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of monovalent control compounds (2a–c) and (3a–c). Reagents and conditions: (a) methylamine, diglycolic anhydride, THF, 60-70%; (b) EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF, 9a or 9b or 9c, 40-50%; (c) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 50-60%; (d) diglycolic anhydride, 40-50%, THF; (e) aminomethyl-substituted IT1t or 6β-oxymorphamine. EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DMF, 20-90%.

In Vitro Pharmacological Studies.

All synthesized ligands were firstly evaluated for their binding affinities and functional properties on the corresponding receptors. From the competitive radioligand binding and functional assay results adopted on the MOR monoclonal CHO cells (Table 1), all tested ligands maintained excellent recognition to the MOR, which justified our original molecular design pertaining to the MOR pharmacophore. In detail, all of bivalent ligands were basically equipotent to the parent pharmacophore oxymorphone with nanomolar binding affinity, indicating that the spacer did not affect their binding to the MOR. Meanwhile, similar binding affinities of monovalent controls 2a–c and oxymorphone further suggested that incorporation of spacers appeared not to interfere with MOR binding.

Table 1.

MOR radioligand binding assay, [35S]-GTPγS functional assay and calcium mobilization assay results of bivalent ligands 1a–c and MOR monovalent controls 2a–c.a

| Compounds | [3H]NLX binding | MOR [35S]-GTPγS binding | Ca2+ flux | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | % Emax of DAMGO | EC50 (nM) | |

| oxymorphoneb | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 4.39 ± 0.76 | 98.0 ± 11.0 | 44.3 ± 9.7 |

| 1a | 2.22 ± 0.22 | 3.07 ± 0.01 | 78.4 ± 0.5 | 18.9 ± 5.2 |

| 2a | 1.95 ± 0.14 | 70.28 ± 3.89 | 94.3 ± 3.6 | 146.3 ± 25.0 |

| 1b | 2.23 ± 0.12 | 8.11 ± 1.65 | 78.3 ± 2.2 | 28.3±12.8 |

| 2b | 1.71 ± 0.04 | 49.34 ± 6.73 | 89.1 ± 2.1 | 121.8 ± 15.9 |

| 1c | 2.19 ± 0.23 | 3.39 ± 0.09 | 70.6 ± 0.9 | 28.1 ± 4.9 |

| 2c | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 20.01 ± 1.78 | 98.5 ± 2.7 | 210.6 ± 2.7 |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Membranes for radioligand binding assays were prepared from mMOR-CHO cells. Calcium mobilization assay was performed on hMOR-CHO cells.

Data taken from Ref. [49].

Based on [35S]-GTPγS functional assay results, all of the tested ligands maintained reasonable potency and showed 70-98% relative efficacy compared to the full MOR agonist DAMGO, which demonstrated that they acted as potent and efficacious MOR agonists as intended in our original molecular design. In addition, the calcium mobilization assay results showed that all tested bivalent ligands acted as potent agonists, exhibiting comparable potency relative to the parent pharmacophore oxymorphone as well. Meanwhile, when comparing the monovalent controls with their corresponding bivalent ligands, their binding affinities at the MOR was not significantly different, whereas a relatively lower potency in calcium mobilization assay was observed, indicating that the spacers were well tolerated in binding to the receptor. Taken together, the desirable recognition of our target ligands to the MOR suggested that they may elicit potential analgesia as designed.

The compounds carrying IT1t pharmacophore were then subjected to their binding affinity and functional activity tests at the CXCR4 (Table 2). As tested previously, IT1t showed a Ki value of 8.0 nM in the radioligand binding assay, and an IC50 value of 1.1 nM in the calcium mobilization assay [50]. As depicted in Table 2, all tested compounds showed binding affinities at the micromolar level. Moreover, similar binding affinities between bivalent ligands 1a–c suggested that the spacer length seemed not to play a significant role in their binding to the CXCR4. An even greater reduction in the binding affinity of monovalent controls 3a–c than their corresponding bivalent ligands 1a–c indicated that the spacers seemed not well tolerated in recognition to the CXCR4. These observations were basically consistent with our prior study in which antibody binding assays were adopted to assess binding affinity to the CXCR4 [35, 37].

Table 2.

CXCR4 radioligand binding assay and calcium mobilization assay results of bivalent ligands 1a–c and CXCR4 monovalent control 3a–c.a

| Compounds | [125I] SDF-1α binding | Ca2+ flux |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Ki (μM) | IC50 (μM) | |

| 1a | 45.66 ± 8.10 | 18.16 ± 1.10 |

| 3a | 307.33 ± 12.15 | 53.00 ± 6.60 |

| 1b | 26.60 ± 7.13 | 40.19 ± 5.80 |

| 3b | 412.39 ± 119.01 | 78.00 ± 21.00 |

| 1c | 32.38 ± 14.63 | 63.48 ± 8.92 |

| 3c | 218.66 ± 8.23 | ND |

The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The CXCR4 radioligand binding assay was performed on human recombinant Chem-1 cells. The antagonist calcium assay was conducted on HOS-CXCR4 cells. ND: not determined, no inhibition up to 400 μM.

Subsequently, in calcium mobilization assays conducted on HOS-CXCR4 cells, all investigated ligands showed no obvious agonism and antagonized SDF-1 induced calcium flux with considerably lower potency than the standard antagonist IT1t. A similar trend was observed for the monovalent controls. In all, despite the seemingly reasonable recognition of the ligands to the CXCR4, the detrimental role of the spacers observed in these studies summons further optimization of the molecular design.

In Vivo Pharmacological Studies.

As the primary end product of glycolysis, lactic acid has recently been demonstrated to serve as a modulator in immune cells during inflammation as well as a contributor to specific pain conditions [51,52]. We thus tested these target bivalent ligands with varying length of spacers for their antinociceptive effectiveness to block stretching behavior elicited by intraperitoneal injection of 0.56% lactic acid (IP acid) in ICR mice. Separate groups of mice (N = 5) were used to test each of the three target ligands. Each group was tested using a within-subject 2x2 design with four treatments consisting of (a) 3.2 mg/kg of one of the tested drugs (or its saline vehicle) as a pretreatment to (b) IP acid (or its water vehicle). Results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Both oxycodone and ketoprofen were adopted as positive controls in this assay, which produced a dose-dependent and significant decrease in IP acid-stimulated stretching [53].

After vehicle pretreatment, IP acid stimulated a significant stretching response in all three groups, and none of the tested compounds significantly reduced IP acid-stimulated stretching (main effect of IP acid in all groups, p<0.05, but no significant effect of tested bivalent compounds). It is noteworthy that compound 1a produced the largest decrease in the mean number of stretches. Although the p value for this effect (p=0.11) did not meet the criterion for statistical significance, further evaluation of this compound may be warranted. Higher doses of compounds 1a–c were not tested because pilot studies indicated that a higher dose of 10 mg/kg decreased locomotor activity in ICR mice (data not shown), which may interfere with the interpretation of the data.

In terms of the design strategy of bivalent ligands as chemical probes that target the dimerization of GPCRs, two selected pharmacophores bridged together with a spacer of certain length should, in principle, simultaneously interact with both receptors in the dimer if proper attachment positions on both pharmacophores were well designated and a spacer of suitable length was chosen to tether them. Once all these criteria are achieved in optimized bivalent ligands, desirable pharmacological effects of these ligands should generally be observed in subsequent biological evaluations. In this context, we speculated that the observations in the in vivo study could largely result from the decreased binding affinity of target compounds at the CXCR4. This provides a compelling incentive to conduct optimization of our molecular design, particularly for the CXCR4 pharmacophore, in order to obtain more potent bivalent ligands with preferable analgesic effect.

On the other hand, intraperitoneal route was adopted in the current in vivo assay because this technique is quick and minimally stressful for animals [54]. Due to the large molecular size, high molecular weight, and total polar surface area of bivalent ligands, we envisaged that the solubility and cell permeability could also be possible limitations to their in vivo pharmacological activity, which have been supported by previously reported druggability assessment of other bivalent ligands [55,56]. In addition, since the stretching response of the mice is mainly mediated at the level of the spinal cord in the CNS, we postulated that the less than ideal antinociceptive effectiveness of these bivalent ligands could also due in part to their poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability though more in-depth studies are warranted to verify such speculation. Nevertheless, our preliminary in vivo screening assay suggested that compound 1a may possess seemingly potential effect in alleviating inflammatory pain, though such a conclusion needs to be subjected to further complementary assessment.

Molecular Modeling Study.

In order to further understand the interaction between bivalent ligand 1a and the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer as well as to interpret the in vitro results, molecular docking study was performed following previously described procedures [36,37]. The binding features of the MOR_oxymorphone and CXCR4_IT1t complexes were firstly analyzed (Figure S1). In the MOR_oxymorphone complex (Figure S1a), hydrophobic ìnteractions were formed between the epoxymorphinan moiety of oxymorphone and several hydrophobic residues, M1513.36, W2936.48, I2966.51, H2976.52, I3227.39, and Y3267.43. Additionally, the protonated nitrogen atom in the 17-amino group formed ionic interaction with D1473.32 and the dihydrofuran oxygen atom formed hydrogen bonding interaction with Y1483.33. These interactions were basically similar to those of reported MOR agonists, such as INTA, interacted with the MOR [57,58].

At the same time, as shown in CXCR4_IT1t complex (Figure S1b), the residues from TM1, TM2, TM3, TM7, extracellular loop 1 (ECL1), and ECL2 appeared to fully accommodate IT1t, in which the residues L411.35, W942.60, W102ECL1, V1123.28, I185ECL2, and C186ECL2 may form hydrophobic interactions with the two cyclohexane rings of IT1t. It is noteworthy that the symmetrical isothiourea group of IT1t may flip to each other’s position, inducing one of the nitrogen atoms of the symmetrical isothiourea group to form an ionic interaction with D972.63 and another one to form a polar interaction with C186ECL2.

In the MOR-CXCR4_1a complex, the MOR pharmacophore oxymorphone of compound 1a primarily occupied the same binding pocket of the MOR as that of oxymorphone in the MOR_oxymorphone complex (Figures 4 and S1a). However, due to the tensile force caused by the spacer tethered at the C-6 position of the MOR pharmacophore oxymorphone, it appeared that the MOR pharmacophore oxymorphone moved somewhat from where oxymorphone bound with the MOR (Figure S1c). This provides a putative explanation of the slightly lower MOR binding affinity of compound 1a as compared to that of oxymorphone.

Figure 4.

The binding mode the MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer complexing with compound 1a after energy minimization. The CXCR4 and MOR were shown as cartoon models in light-green and light-blue, respectively. The compound 1a was shown as a stick model in cyan. The key residues of the CXCR4 and MOR were shown as stick models in yellow and light-pink, respectively.

Meanwhile, the CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t was found to form similar interactions with the CXCR4 to those of IT1t in the CXCR4 (Figures 4 and S1b). The most noticeable difference is that the symmetrical isothiourea groups of IT1t may not be able to flip to each other’s position due to the introduction of the spacer to one cyclohexyl group adjacent to the N3 nitrogen atom of the isothiourea group. As a consequence, unlike the scenario of IT1t interacting with the CXCR4, these two interactions, the ionic interaction with D972.63 and the polar interaction with C186ECL2, for compound 1a may not be satisfied at the same time in the MOR-CXCR4_1a complex. This may explain why the binding affinity of compound 1a at the CXCR4 was considerably lower than that of IT1t.

Conclusions

Mounting studies have implied specific functional roles of crosstalk between MOR and CXCR4 that could occur in nervous system. In terms of previously published results, a possibility has been raised that MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers may be implicated in these functional interactions involved in pain modulation. Given the fact that bivalent ligands targeting both receptors concurrently serve as invaluable tools to unveil mechanism of GPCR dimerizations as well as potential therapeutics in treating specific diseases, it would be intriguing to identify novel bivalent ligands aiming at putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers and investigate their potential roles in pain modulation. To this end, we designed, synthesized and pharmacologically characterized a series of novel bivalent ligands containing MOR agonist and CXCR4 antagonist pharmacophores.

Further In vitro studies suggested their reasonable recognition at both receptors, albeit somehow decrease in potency at the CXCR4 relative to the parent ligand IT1t. Subsequent in vivo studies indicated that compound 1a showed the most promise as a potential antinociceptive treatment to attenuate IP acid-induced stretching in mice. Additional molecular docking study indicated that compound 1a may bind with the putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimer to elicit its potential pharmacological effect. Meanwhile, we also recognized the possible intrinsic shortcoming in our current molecular design in terms of the decreased binding affinity at the CXCR4. Based on the molecular docking results with respect to CXCR4 pharmacophore IT1t, potentially different attachment points on it will be considered as the top priority followed by varying spacer lengths in the optimization of molecular design. Collectively, as a proof-of-concept, bivalent ligand 1a featuring a MOR agonist and a CXCR4 antagonist may serve as a novel chemical probe to elucidate the plausible role of heterodimerization of these two receptors in pain modulation and may be a reasonable starting point to further develop novel analgesic agents in the treatment of chronic pain by targeting putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers.

Experimental Section.

Chemistry.

All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or other venders without further purification. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were performed on Analtech Uniplate F254 plates and flash column chromatography (FCC) was carried out over silica gel (230–400 mesh, Merck). Proton and carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR and 13C NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Ultrashield 400 Plus spectrometer, and chemical shifts were expressed in ppm. Mass spectra were obtained on an Applied BioSystems 3200 Q trap with a turbo V source for TurbolonSpray. Analytical reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Varian ProStar 210 system using Agilent Microsorb-MV 100-5 C18 column (250 x 4.6 mm). HPLC method were conducted at room temperature and a flow rate of 0.65 mL/min. Mobile phase is water (0.1% TFA)/acetonitile (40/60 to 0/100) at 0.65 mL/min over 30 min. The UV detector was set up at 210 nm. Compounds purities were calculated as the percentage peak area of the analyzed compound, and retention times (tR) were presented in minutes. The purity of all target compounds was identified as ≥ 95%.

General Procedure for Amide Coupling.

A solution of carboxylic acid (1.5 equiv) in anhydrous DMF (2 mL) was added with hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt, 3 equiv), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI, 3 equiv), 4 Å molecular sieves, and triethylamine (5 equiv) at 0 °C. After 30 min, a solution of amine (1 equiv) in anhydrous DMF (1.5 mL) was added dropwise at the same temperature. The resulting mixture was warmed and stirred at room temperature. Once TLC indicated complete consumption of the starting material, the reaction mixture was filtered through celite. The filtrate was concentrated to dryness followed by purification through column chromatography.

3-dimethoxy-17-methyl-14β-hydroxy-4,5α-epoxymorphinan-6-one (5)

To a solution of thebaine (1g, 3.21 mmol) in HCOOH (0.8 mL) and H2SO4 (2.5 mL, 0.7%) was added H2O2 (660 μL, 30%) dropwise at 0 °C. The resulting clear solution was kept in refrigerator (4 °C) under N2 for 12 h. TLC indicated complete consumption of starting material, and ammonia water was added to adjust pH to 9 followed by the addition of DCM (150 mL). The organic layer was washed by brine (3 × 50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to afford a white solid product, which was then subject to hydrogenation under 35 psi for 5 h. After filtration through celite, filtrate was collected and concentrated. The resulting residue was then washed by ether to give an off-white solid (770 mg, 76%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.70 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (s, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.16 (d, J = 18.8 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (dt, J = 14.5, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.86 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (dd, J = 18.8, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.38 (m, 1H), 2.29 (dt, J = 14.5, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 2.16(m, 1H), 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.64 (m, 1H), 1.58 (m, 1H). HRMS calcd for C18H22NO4 [M + H]+: 316.1543. Found: 316.1539.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxymorphinan-6-one (6)

To a solution of compound 5 (100 mg, 0.317 mmol) in chloroform (2.5 mL) was added a solution of BBr3 in chloroform (150 μL, 1.5 mL) slowly at −20 °C. The resulting mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 5 h, which was quenched by addition of ice water. Then ammonia water was added to adjust pH to 9 followed by the addition of DCM (150 mL). The organic layer was washed by brine (3 × 50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to afford a white residue, which was purified by column chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 30/1) to yield an off-white solid (82 mg, 86%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.72 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.15 (d, J = 18.5 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (td, J = 14.5, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (dd, J = 18.5, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.48 (m, 1H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.30 (dt, J = 14.5, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.64 (m, 1H), 1.59 (m, 1H), 1.56 (dd, J = 12.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H). HRMS calcd for C17H20NO4 [M + H]+: 302.1387. Found: 302.1372.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6-dibenzylaminomorphinan (7)

To a round bottom flask (500 mL) charged with toluene (110 mL) was added compound 6 (500 mg, 1.66 mmol), benzoic acid (264 mg, 2.16 mmol), p-toluenesulfonic acid (5 mg, catalytic amount) and dibenzylamine (414 μL, 2.16 mmol). The resulting mixture was reflux for 22 h under nitrogen atmosphere and then removed a portion of toluene (80 mL) before cooled down to room temperature. EtOH (20 mL) and molecular sieves were added followed by the addition of NaCNBH3 (84 mg, 1.33 mmol), the mixture was stirred overnight and filtered through celite. The filtrate was then concentrated to give a brown oil residue. To this residue was dissolved with DCM (100 mL) and washed by ammonia water (3%, 60 mL). All organic layer was collected, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum to afford a pale solid, which was then purified by recrystallization in MeOH. The target compound was obtained as a white solid (360 mg, 45%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.44–7.42 (m, 4H), 7.31–7.27 (m, 4H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 2H), 6.56 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (s, 1H), 3.89 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 2H), 3.60 (d, J = 14.2 Hz, 2H), 3.06 (d, J = 18.4 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (ddd, J = 12.8, 7.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.48 (dd, J = 18.3, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.38 (dd, J = 11.6, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.20 (m, 1H), 2.12 (m, 1H), 2.00 (dt, J = 13.0, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 1.68 (m, 1H), 1.59 (m, 1H), 1.42 (m, 1H), 1.22 (dt, J = 13.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H). HRMS calcd for C31H35N2O3 [M + H]+: 483.2642. Found: 483.2640.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-aminomorphinan hydrochloride (8)

To a solution of compound 7 (360 mg, 0.747 mmol) and concentrated hydrochloric acid (400 μL) in MeOH (16 mL) was added Pd/C (36 mg). The resulting mixture was hydrogenated (60 psi) for 5 days. Then the catalyst was filtered through celite and washed by MeOH. All filtrate was concentrated under vacuum. The light yellow raw product was purified by recrystallization from MeOH and the target compound was obtained as an off-white solid (233 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.56 (s, 1H), 9.24 (s, 1H), 8.44 (s, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (s, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 3.62 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (dd, J = 19.7, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 3H), 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.45 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (m, 1H), 1.99 (q, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 1.74 (t, J = 12.2 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 1.30 (t, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H). HRMS calcd for C17H23N2O3 [M + H]+: 303.1703. Found: 303.1692.

Synthetic procedures of aminomethyl-substituted IT1t, 9a-c, 10a-c, 14, 15a-c, 16a-c and 17a-c have been previously reported [35, 37].

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(3,10-dioxo-1-phenyl-2,12-dioxa-4,9-diazatetradecanamido)morphinan (11a)

The title compound was prepared according to the general amide coupling procedure by reacting 10a (706 mg, 2.088 mmol) with compound 8 (355 mg, 0.949 mmol). The resulting residue was dissolved in MeOH followed by the addition of K2CO3 (5 eq.) and stirred for 24 h. After 24 h, the K2CO3 was filtered out and the filtrate was concentrated to dryness to afford a brown solid, which was purified with column chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 9/1) to afford a light yellow solid (400 mg, 68%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.30 (m, 5H), 7.23 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.81 (s, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.24 (m, 1H), 3.15–3.10 (m, 2H), 3.03–2.97 (m, 3H), 2.72 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.52 (m, 1H), 2.37 (m, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 1.98 (m, 1H), 1.77 (m, 1H), 1.46–1.40 (m, 5H), 1.30–1.20 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.43, 168.19, 156.08, 142.03, 140.44, 137.25, 131.20, 128.30 (2 C), 127.69, 127.67, 123.48, 118.40, 117.06, 117.01, 90.46, 70.36, 70.32, 70.32, 69.79, 65.08, 64.08, 50.63, 46.41, 45.37, 42.27, 37.87, 29.97, 26.90, 26.86, 26.62, 24.52, 21.50. HRMS calcd for C33H42N4O8Na [M + Na]+: 645.2895. Found: 645.2910.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(3,12-dioxo-1-phenyl-2,14-dioxa-4,11-diazahexadecanamido)morphinan (11b)

The synthesis of 11b was conducted following similar procedure as 11a except with 10b as the starting material. (394 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.01 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.28 (m, 6H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.80 (s, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.19–3.02 (m, 4H), 3.00–2.93 (m, 3H), 2.72 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (dd, J = 11.4, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.10 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 1H), 1.78 (m, 1H), 1.43 (m, 5H), 1.25 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.37, 168.19, 156.05, 142.04, 140.44, 137.29, 131.98, 131.20, 129.15, 128.29, 127.82, 127.68, 127.66, 123.48, 118.41, 117.01, 90.47, 70.37, 70.32, 69.78, 65.03, 64.12, 64.07, 50.62, 46.41, 45.38, 42.27, 38.09, 29.97, 29.31, 29.20, 26.07, 25.90, 24.52, 21.47. HRMS calcd for C35H46N4O8Na [M + Na]+: 673.3208. Found: 673.3227.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(3,14-dioxo-1-phenyl-2,16-dioxa-4,13-diazaoctadecanamido)morphinan (11c)

The synthesis of 11c was conducted following similar procedure as 11a except with 10c as the starting material. (555 mg, 74%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.51 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 5H), 6.81 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 4.83 (s, 1H), 4.41 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (m, 4H), 3.30 (dd, J = 13.7, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 3.18 (dd, J = 13.6, 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (m, 1H), 2.77 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.61 (dd, J = 18.5, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 2.42 (m, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.27–2.18 (m, 2H), 1.78 (dd, J = 9.4, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 1.64 (m, 1H), 1.56–1.45 (m, 7H), 1.34–1.28 (m, 8H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.54, 168.40, 156.49, 143.16, 139.41, 136.65, 130.39, 128.53, 128.11, 124.64, 119.31, 117.83, 92.39, 70.90, 70.34, 66.63, 64.91, 49.36, 46.59, 45.48, 42.86, 41.05, 39.10, 31.67, 29.90, 29.52, 29.06, 28.84, 26.81, 26.57, 23.16, 21.95. HRMS calcd for C37H51N4O8 [M + H]+: 679.3701. Found: 679.3710.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(2-(2-(4-aminobutylamino)-2-oxoethoxy)acetamido)morphinan (12a)

The synthesis of 12a was conducted following similar procedure as 8 except with 11a as the starting material. (260 mg, 83%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.25 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.15–3.11 (m, 2H), 3.08–3.03 (m, 2H), 2.97 (m, 1H), 2.71 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 2.64–2.60 (m, 2H), 2.38 (dd, J = 11.5, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.28 (m, 1H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 1H), 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.53–1.37 (m, 7H), 1.33–1.16 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.49, 168.23, 142.05, 140.56, 131.17, 123.39, 118.38, 117.32, 117.07, 90.45, 70.42, 70.35, 69.78, 64.07, 50.66, 46.42, 45.37, 42.27, 37.85, 29.99, 28.34, 26.51, 24.52, 21.48. HRMS calcd for C25H37N4O6 [M + H]+: 489.2708. Found: 489.2691.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(2-(2-(6-aminohexylamino)-2-oxoethoxy)acetamido)morphinan (12b)

The synthesis of 12b was conducted following similar procedure as 8 except with 11b as the starting material. (290 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.22 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.17–3.12 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.97 (m, 1H), 2.72 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.37 (m, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.15 (m, 1H), 1.98 (m, 1H), 1.78 (m, 1H), 1.46–1.40 (m, 5H), 1.31–1.21 (m, 7H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.22, 168.16, 142.05, 140.54, 131.18, 129.61, 118.38, 117.32, 117.07, 90.43, 70.42, 70.35, 69.79, 64.06, 50.61, 46.36, 44.40, 42.27, 37.85, 29.98, 29.94, 29.91, 26.10, 25.81, 24.49, 21.47. HRMS calcd for C27H41iN4O6 [M + H]+: 517.3021. Found: 517.2997.

17-methyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6β-(2-(2-(8-aminooctylamino)-2-oxoethoxy)acetamido)morphinan (12c)

The synthesis of 12c was conducted following similar procedure as 8 except with 11c as the starting material. (410 mg, 92%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.23 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.94, (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.52 (m 1H), 3.15–3.10 (m, 2H), 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.71 (m, 1H), 2.59–2.54 (m, 2H), 2.37 (m, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 2.15 (m, 1H), 1.99 (m, 1H), 1.78 (m, 1H), 1.48–1.41 (m, 4H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.32–1.17 (m, 11H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.33, 168.21, 142.03, 140.49, 131.15, 123.38, 118.34, 117.04, 90.49, 70.40, 70.35, 69.81, 64.07, 50.69, 46.45, 45.38, 42.24, 40.74, 38.09, 31.33, 29.99, 29.15, 28.72, 28.63, 26.28, 26.14, 24.51, 21.49. HRMS calcd for C29H45N4O6 [M + H]+: 545.3334. Found: 545.3318.

16-(6β-oxymorphamino)-5,12,16-trioxo-3,14-dioxa-6,11-diazahexadecanoic acid (13a)

To a 25 mL flask charged with 12a (255 mg, 0.522 mmol) and diglycolic anhydride (69 mg, 0.574 mmol) was added anhydrous DMF (3 mL). The resulting solution was allowed to stir overnight at room temperature and then concentrated under vacuum to give a light yellow oil. The oil was recrystallized in MeOH/Et2O to yield a gold solid (313 mg, 99%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.34 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 8.11 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 6.64, (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.95 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 4H), 3.90 (s, 1H), 3.49 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.16–3.09 (m, 6H), 2.76 (m, 1H), 2.68 (m, 1H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 2.32–2.22 (m, 2H), 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.53 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 1.47–1.40 (m, 5H), 1.33–1.27 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.96, 168.98, 168.48, 168.26, 142.08, 140.92, 130.38, 122.04, 118.86, 117.45, 90.12, 70.54, 70.36, 69.78, 69.00, 50.42, 48.59, 46.28, 45.74, 41.61, 37.87, 37.78, 35.77, 29.68, 26.57, 26.46, 24.13, 22.33, 15.16. HRMS calcd for C29H39N4O10 [M – H]−: 603.2672. Found: 603.2646.

18-(6β-oxymorphamino)-5,14,18-trixox-3,16-dioxa-6,13-diazanonadecan-1-oic acid (13b)

The synthesis of 13b was carried out following similar procedure as 13a except with 12b as the starting material. (380 mg, 100%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.34 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.95–3.91 (m, 8H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.17–3.14 (m, 2H), 3.11–3.08 (m, 2H), 2.80–2.73 (m, 2H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 2.31 (m, 1H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.53 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 1.46–1.40 (m, 5H), 1.31–1.25 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.25, 169.01, 168.41, 168.23, 162.29, 142.08, 140.90, 130.38, 122.02, 118.82, 117.45, 90.18, 70.73, 70.35, 69.74, 69.34, 64.87, 50.39, 46.25, 45.73, 41.58, 38.06, 37.98, 30.75, 29.75, 29.06, 28.96, 26.05, 25.98, 24.10, 22.29. HRMS calcd for C31H43N4O10 [M – H]−: 631.2985. Found: 631.3014.

20-(6β-oxymorphamino)-5,16-18-trixox--3,18-dioxa-6,15-diazaicosanoic acid (13c)

The synthesis of 13c was carried out following similar procedure as 13a except with 12c as the starting material. (520 mg, 100%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.29 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 6.64 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.92 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 1H), 3.51 (m, 1H), 3.20–3.14 (m, 2H), 3.12–3.06 (m, 4H), 2.72–2.64 (m, 2H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.34–2.16 (m, 3H), 1.81 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.39 (m, 6H), 1.30–1.23 (m, 10H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.20, 168.93, 168.37, 168.23, 162.26, 142.06, 140.84, 130.45, 122.18, 118.76, 117.39, 90.18, 70.66, 70.37, 69.73, 69.22, 64.85, 64.75, 50.43, 46.12, 45.80, 41.66, 38.12, 38.09, 35.73, 30.73, 29.82, 29.06, 28.98, 28.53, 26.21, 24.13, 22.21. HRMS calcd for C33H47N4O10 [M – H]−: 659.3298. Found: 659.3308.

Bivalent ligand (1a, n = 2)

The title compound was prepared according to the general amide coupling procedure by reacting 13a with the aminomethyl-substituted IT1t. The resulting crude residue was purified using column chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 8/1) to afford the product as a light yellow solid (60 mg, 49%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.23 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.09–7.98 (m, 3H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 4H), 3.93 (s, 4H), 3.91 (m, 1H), 3.72 (m, 1H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 3.25 (m, 1H), 3.18–3.10 (m, 6H), 3.06–2.93 (m, 3H), 2.89 (m, 1H), 2.82 (m, 1H), 2.73 (m, 1H), 2.71–2.58 (m, 4H), 2.35–2.25 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.65 (m, 4H), 1.61–1.52 (m, 3H), 1.51–1.38 (m, 8H), 1.37–1.25 (m, 6H), 1.23 (s, 3H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.18–1.02 (m, 2H), 1.01–0.91 (m, 2H), 0.85 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.70, 168.61, 168.56, 168.36, 162.93, 150.75, 150.03, 142.05, 141.12, 131.91, 119.39, 119.10, 117.69, 89.85, 82.89, 73.69, 70.34, 69.79, 65.56, 64.52, 64.77, 55.61, 55.49, 55.34, 50.34, 46.70, 43.98, 42.78, 41.32, 37.88, 37.83, 36.72, 36.62, 33.89, 33.83, 33.76, 33.34, 30.83, 29.45, 29.43, 28.91, 28.86, 28.74, 28.71, 28.67, 28.60, 27.61, 26.67, 25.08, 23.86, 23.70. HRMS calcd for C51H76N9O9S2 [M + H]+: 1022.5202. Found: 1022.5227.

Bivalent ligand (1b, n = 4)

The synthesis of 1b was conducted following similar procedure as 1a except with 13b and aminomethyl-substituted IT1t as the starting materials. (63 mg, 32%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.07 (s, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.06–8.00 (m, 3H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (s, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.96–3.90 (m, 8H), 3.87 (m, 1H), 3.69 (m, 1H), 3.51 (m, 1H), 3.38–3.35 (m, 2H), 3.18–3.07 (m, 7H), 3.02 (m, 1H), 2.99–2.93 (m, 2H), 2.84–2.79 (m, 2H), 2.78–2.62 (m, 4H), 2.41 (m, 1H), 2.31 (s, 3H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.01 (m, 1H), 1.82–1.74 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.65 (m, 4H), 1.60–1.51 (m, 3H), 1.48–1.40 (m, 7H), 1.31–1.24 (m, 9H), 1.21 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.09–0.95 (m, 3H), 0.85 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.64, 168.60, 168.48, 168.41, 163.20, 150.25, 149.35, 142.05, 140.50, 123.65, 131.12, 118.46, 117.07, 90.43, 82.58, 74.37, 70.38, 69.79, 64.19, 64.02, 59.83, 55.56, 55.42, 55.22, 50.62, 46.35, 43.99, 42.56, 42.21, 38.05, 38.03, 36.91, 36.64, 33.94, 33.69, 33.62, 33.41, 33.38, 30.85, 29.94, 29.83, 29.19, 29.14, 28.99, 28.87, 28.73, 28.69, 26.04, 26.02, 25.12, 24.49, 23.71, 21.58. HRMS calcd for C53H80N9O9S2 [M + H]+: 1050.5515. Found: 1050.5544.

Bivalent ligand (1c, n = 6)

The synthesis of 1c was conducted following similar procedure as 1a except with 13c and aminomethyl-substituted IT1t as the starting materials. (66 mg, 35%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.04 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05–7.99 (m, 3H), 6.59 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.83 (s, 1H), 4.59 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.97–3.90 (m, 8H), 3.87 (m, 1H), 3.69 (m, 1H), 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.38–3.36 (m, 2H), 3.21–3.06 (m, 7H), 3.04 (m, 1H), 3.01–2.95 (m, 2H), 2.85 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.76–2.62 (m, 4H), 2.54 (m, H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.32 (s, 3H), 2.17 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 1H), 1.84–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.74–1.65 (m, 4H), 1.62–1.53 (m, 3H), 1.49–1.39 (m, 8H), 1.31–1.24 (m, 13H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.13–0.91 (m, 3H), 0.84 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.59, 168.44, 168.38, 168.22, 163.18, 149.33, 148.80, 142.06, 140.49, 131.25, 123.49, 118.47, 117.07, 90.53, 82.59, 74.35, 70.44, 69.82, 64.09, 63.25, 60.05, 55.59, 55.19, 54.91, 50.67, 46.40, 44.03, 42.56, 42.27, 38.15, 38.09, 36.94, 36.73, 34.00, 33.82, 33.72, 33.62, 33.55, 30.34, 29.97, 29.23, 29.16, 28.99, 28.87, 28.84, 28.68, 27.68, 27.55, 26.37, 26.33, 25.58, 25.15, 24.47, 23.72, 21.57. HRMS calcd for C55H84N9O9S2 [M + H]+: 1078.5828. Found: 1078.5844.

MOR Monovalent Control (2a, n = 2)

The title compound was prepared according to the general amide coupling procedure by reacting acid 17a with 6β-oxymorphamine hydrochloride salt. After starting material was completely consumed, the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and the filtrate was then concentrated under vacuum. The resulting residue was treated with K2CO3 (3 equiv) in MeOH. After 24 h, K2CO3 was filtered out and the filtrate was concentrated to dryness to afford a brown solid. The residue was then purified using chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 8/1) to afford the product as a light yellow solid. (70 mg, 57%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.15–7.96 (m, 4H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.12 (s, 1H), 4.77 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.91 (s, 4H), 3.56 (m, 1H), 3.31 (m, 1H), 3.16–3.13 (m, 4H), 3.04–2.98 (m, 3H), 2.80 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H), 2.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 2.47–2.36 (m, 2H), 1.84 (m, 1H), 1.66 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 1.48–1.44 (m, 4H), 1.20 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.84, 168.43, 168.31, 168.26, 142.07, 141.29, 129.46, 120.54, 119.27, 117.88, 89.70, 70.34, 70.23, 69.79, 65.93, 64.85, 50.21, 45.41, 45.01, 40.90, 37.88, 37.81, 35.73, 29.24, 27.31, 26.67, 25.06, 23.66, 23.13, 8.41. HRMS calcd for C30H44N5O9 [M + H]+: 618.3134. Found: 618.3149.

MOR Monovalent Control (2b, n = 4)

The synthesis of 2b was conducted following similar procedure as 2a except with 17b and 6β-oxymorphamine hydrochloride salt as the starting materials. (110 mg, 90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.09–7.99 (m, 3H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.09 (s, 1H), 4.75 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 4H), 3.91 (s, 4H), 3.59–3.57 (m, 2H), 3.31 (m, 1H), 3.14–3.08 (m, 4H), 3.05–2.96 (m, 2H), 2.80 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 3H), 2.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 2.46–2.35 (m, 2H), 1.84 (m, 1H), 1.66 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.40 (m, 6H), 1.35 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.24 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.85, 168.38, 168.29, 168.27, 142.07, 141.30, 129.45, 120.55, 119.29, 117.88, 89.69, 70.36, 70.32, 70.31, 70.24, 69.78, 65.97, 50.21, 47.20, 45.01, 40.90, 38.07, 38.01, 29.22, 29.15, 29.13, 29.04, 27.30, 26.04, 25.07, 23.66, 23.13. HRMS calcd for C32H47N5O9Na [M + Na]+: 668.3266. Found: 668.3286.

MOR Monovalent Control (2c, n = 6)

The synthesis of 2c was conducted following similar procedure as 2a except with 17c and 6β-oxymorphamine hydrochloride salt as the starting materials. (50 mg, 66%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.07–8.02 (m, 3H), 6.71 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.08 (s, 1H), 4.75 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 2H), 3.91 (s, 2H), 3.90 (s, 2H), 3.31 (m, 1H), 3.15–3.05 (m, 5H), 3.03–2.97 (m, 2H), 2.80 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H), 2.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 3H), 2.48–2.35 (m, 2H), 1.84 (m, 1H), 1.66 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.37 (m, 7H), 1.33 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.21 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.86, 168.35, 168.29, 168.25, 142.07, 141.30, 129.44, 120.54, 119.28, 117.88, 89.69, 70.36, 70.32, 70.24, 70.23, 69.79, 65.95, 50.21, 47.19, 45.01, 40.90, 38.14, 38.08, 29.23, 29.16, 28.64 (2C), 27.31, 26.32 (2C) , 25.06, 23.66, 23.14. HRMS calcd for C34H53N5O9 [M + H]+: 674.3760. Found: 674.3787.

Synthetic procedures of compounds 3a–c have been previously reported. [35, 37]

Biological Evaluation:

Drugs.

All drugs and test compounds were dissolved in pyrogen-free isotonic saline (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) or sterile-filtered distilled/deionized water. All other reagents and radioligands were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Thermo Fisher.

Animals.

Adult male and female ICR mice (Envigo) were housed in same-sex groups of 2-3 mice per cage in an animal facility maintained at 22 °C on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center and complied with the recommendations of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

In Vitro Competitive Radioligand Binding Assay.

Competition binding was performed using the monoclonal mouse mu opioid receptor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines (MOR-CHO). MOR-CHO cell culture and membrane homogenate preparation were performed as previously described [59]. In this assay, 20 μg of membrane protein was incubated with 1.4 nM [3H]naloxone in the presence of different concentrations of test compounds in TME buffer (50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM EGTA, pH 7.7) for 1.5 h at 30 °C. After incubation, the bound radioactive ligand was separated from free radioligand by filtration through a GF/B glass fiber filters and rinsed three times with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2) using a Brandel harvester. The results were determined by utilizing a scintillation counter. Specific (i.e., opioid receptor-related) binding at the MOR was determined as the difference in binding obtained in the absence and presence of 5 μM naltrexone. The IC50 values were determined and converted to Ki values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation.

In Vitro [35S]-GTPγS Functional Assay.

In the [35S]-GTPγS functional assay, 14 μg of MOR-CHO cell membrane protein was incubated in TME buffer with 100 mM NaCl, 20 μM GDP, 0.1 nM [35S]-GTPγS and varying concentrations of the compound under investigation in a final volume of 500 μl for 1.5 h at 30 °C. Non-specific binding was determined with 20 μM unlabeled GTPγS. Final volume in each assay tube was 500 μl. Furthermore, 3 μM of DAMGO was included in the assay as maximally effective concentration of a full agonist for the MOR. The incubation was terminated by filtration and bound radioactivity determined as described above for the competition binding assay. All samples were assayed in duplicate and repeated at least three times. Percent DAMGO-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was defined as (net-stimulated binding by ligand/net-stimulated binding by 3 μM DAMGO) x 100%.

Calcium Mobilization Assay

The ligands were first tested with various concentrations (0.3 nM to 3 μM) for possible agonist activity in either MOR-CHO or CXCR4-HOS cells. The protocol was the same for the antagonism study for both MOR and CXCR4 cell types, except for the addition of an agonist (either DAMGO or SDF-1). Either MOR-CHO or CXCR4-HOS cells were transfected with Gqi5 pcDNA1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedure. Cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and then trypsinized and transferred to a clear bottom, black 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-one) at 3x106 cells per well in their respective growth media and incubated until confluent. 48 hours after transfection the growth media was decanted and cells were then incubated with 50 μL of fluo-4 AM loading buffer [24 μL 2 mM fluo-4 AM solution (Invitrogen), 12 μL 250 mM probenecid, in 6 mL assay buffer (HBSS–HEPES–Ca–Mg-probenecid)] for 45 min. Loading buffer was then decanted and cells were incubated for an additional 15 min in 20 ¼L of each compound in varying concentrations and 60 μL assay buffer. Ca2+ concentrations were monitored by RFU for 90 seconds right after addition of 20 μL of agonist (DAMGO or SDF-1) to each well in the microplate reader (FlexStation3, Molecular Devices). Peak values were obtained using SoftMaxPro software (Molecular Devices) and non-linear regression curves were generated using GraphPad Prism to calculate IC50 values. All doses were tested with triplicates. All experiments were repeated at least 4 times to obtain standard error values.

In Vivo Pharmacological Studies

Fifteen mice were divided into three groups of N=5 per group with at least two males and two females in each group. Different groups were used to test each of the three tested drugs. Testing in each group was structured as a 2x2 within-subject experimental design in which mice received four total treatments: subcutaneous injection with 3.2 mg/kg of the designated bivalent ligands (or its saline vehicle) administered 30 min before intraperitoneal injection of 10 ml/kg 0.56% lactic acid (or its sterile-water vehicle). Immediately after the i.p. injection, mice were placed into plexiglass cylinder, and behavior was videotaped for 10 min similar to methods described previously [53]. The order of treatments was randomized across mice using a Latin-square design, and test sessions were separated by at least 72 h. Videos were scored for number of stretches by two observers blind to treatments, and scores of the two observers were averaged. Data were analyzed by within-subject two-way ANOVA, with bivalent compound dose (0 or 3.2 mg/kg) and IP acid concentration (0 or 0. 56%) as the two factors, and a significant dose x concentration interaction was followed by the Holm-Sidak post hoc test. The criterion for significance for all tests was p<0.05. All statistical analysis was accomplished with Statistical Analysis.

Molecular Modeling Study.

The crystal structures of the CXCR4 (PDB ID: 3ODU) [41] and MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M) [40] derived from the Protein Data Bank at http://www.rcsb.org were applied to build the respective monomers of the CXCR4 and MOR. The CXCR4 monomer complexing with IT1t (CXCR4_IT1t complex) was from the crystal structure of the CXCR4 (PDB ID: 3ODU) [41]. The MOR monomer complexing with oxymorphone (MOR_oxymorphone complex) was obtained by docking oxymorphone into the active MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M) [40]. Subsequently, the CXCR4_IT1t and MOR_naltrexone complexes were firstly put together by Hex 8.0.0 [60]. Next, the CXCR4_IT1t complex was fixed and its TM1/2 was selected as its interface. Thirdly, rotating the MOR_oxymorphone complex to make its TM5/6 interact with the TM1/2 of CXCR4_IT1t complex. At last, saving the new coordinates of CXCR4_IT1t and MOR_oxymorphone complexes to obtain the heterodimer MOR-CXCR4 with their respective pharmacophores. After that, the heterodimer MOR-CXCR4 was opened by the molecular graphics software Sybyl-X 2.1 (TRIPOS Inc., St. Louis, MO) to link the two pharmacophores by the spacer and finally obtain the complex of MOR-CXCR4 with bivalent ligand 1a (MOR-CXCR4_1a complex). To remove the clashes and strain energy, the CXCR4_IT1t, MOR_oxymorphone, MOR-CXCR4_1a complexes were respectively optimized with 10,000 energy minimization iterations under the Tripos Forcefield (TAFF) in Sybyl-X 2.1 (Figures 3 and Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Effects of bivalent compounds 1a-c on IP acid-induced stretching. Mice were treated with vehicle (open bars) or 3.2 mg/kg of one of the tested drugs (gray bars) followed by intraperitoneal injection of either water (IP H2O) or 0.56% lactic acid (IP acid). Y axis: stretches during 15 min observation time. After vehicle administration, IP acid stimulated stretching in all groups. None of the tested drugs significantly decreased IP acid-stimulated stretching. All bars show mean ± SEM for N = 5 mice.

Statistical Analysis.

One-way ANOVA followed by the posthoc Dunnett test were performed to assess significance using Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The crosstalk between opioid and chemokine receptors play a role in chronic pain

The putative MOR-CXCR4 heterodimers may be involved in pain modulation

Bivalent ligands are powerful to investigate GPCR dimerization and relevant diseases

Bivalent ligand 1a showed reasonable recognition to both the MOR and CXCR4

Bivalent ligand 1a showed potential antinociception in lactic acid-induced pain model

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to NIDA Drug Supply Program for providing the free base of thebaine. This work was partially supported by NIH/NIDA Grant R01-DA044855 (Y.Z.) and P30-DA033930 (S.S.N. and D.E.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Melik Parsadaniantz S, Rivat C, Rostene W, Reaux-Le Goazigo A, Opioid and chemokine receptor crosstalk: a promising target for pain therapy?, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16 (2015) 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tal M, A Role for Inflammation in Chronic Pain, Curr. Rev. Pain 3 (1999) 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lipnik-Stangelj M, Mediators of inflammation as targets for chronic pain treatment, Mediators Inflamm. 2013 (2013) 783235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pak DJ, Yong RJ, Kaye AD, Urman RD, Chronification of Pain: Mechanisms, Current Understanding, and Clinical Implications, Curr. Pain Headache Rep 22 (2018) 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sommer C, Leinders M, Uceyler N, Inflammation in the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain, Pain 159 (2018) 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ, Chemokine receptors as therapeutic targets in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 27 (2006) 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pender SL, Chance V, Whiting CV, Buckley M, Edwards M, Pettipher R, MacDonald TT, Systemic administration of the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha exacerbates inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model, Gut 54 (2005) 1114–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Viola A, Luster AD, Chemokines and their receptors: drug targets in immunity and inflammation, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 48 (2008) 171–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abbadie C, Bhangoo S, De Koninck Y, Malcangio M, Melik-Parsadaniantz S, White FA, Chemokines and pain mechanisms, Brain Res. Rev 60 (2009) 125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen X, Geller EB, Rogers TJ, Adler MW, Rapid heterologous desensitization of antinociceptive activity between mu or delta opioid receptors and chemokine receptors in rats, Drug Alcohol Depend. 88 (2007) 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McCance-Katz EF, Treatment of opioid dependence and coinfection with HIV and hepatitis C virus in opioid-dependent patients: the importance of drug interactions between opioids and antiretroviral agents, Clin. Infect. Dis 41 Suppl 1 (2005) S89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zimmerman DM, Leander JD, Selective opioid receptor agonists and antagonists: research tools and potential therapeutic agents, J. Med. Chem 33 (1990) 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wetzel MA, Steele AD, Eisenstein TK, Adler MW, Henderson EE, Rogers TJ, Mu-opioid induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, RANTES, and IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, J. Immunol 165 (2000) 6519–6524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Luo X, Tai WL, Sun L, Qiu Q, Xia Z, Chung SK, Cheung CW, Central administration of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 antagonist alleviates the development and maintenance of peripheral neuropathic pain in mice, PloS one 9 (2014) e104860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Steele AD, Henderson EE, Rogers TJ, Mu-opioid modulation of HIV-1 coreceptor expression and HIV-1 replication, Virology 309 (2003) 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Happel C, Steele AD, Finley MJ, Kutzler MA, Rogers TJ, DAMGO-induced expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors: the role of TGF-beta1, J. Leukoc. Biol 83 (2008) 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Volkow ND, The epidemic of fentanyl misuse and overdoses: challenges and strategies, World psychiatry 20 (2021) 195–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang P, Yang M, Chen C, Liu L, Wei X, Zeng S, Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/Opioid Receptor Pathway Crosstalk and Impact on Opioid Analgesia, Immune Function, and Gastrointestinal Motility, Front. Immunol 11 (2020) 1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lazim R, Suh D, Lee JW, Vu TNL, Yoon S, Choi S, Structural Characterization of Receptor-Receptor Interactions in the Allosteric Modulation of G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Dimers, Int. J. Mol. Sci 22 (2021) 3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang J, He L, Combs CA, Roderiquez G, Norcross MA, Dimerization of CXCR4 in living malignant cells: control of cell migration by a synthetic peptide that reduces homologous CXCR4 interactions, Mol. Cancer Ther 5 (2006) 2474–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pawig L, Klasen C, Weber C, Bernhagen J, Noels H, Diversity and Inter-Connections in the CXCR4 Chemokine Receptor/Ligand Family: Molecular Perspectives, Front. Immunol 6 (2015) 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Babcock GJ, Farzan M, Sodroski J, Ligand-independent dimerization of CXCR4, a principal HIV-1 coreceptor, J. Biol. Chem 278 (2003) 3378–3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee CW, Ho IK, Pharmacological Profiles of Oligomerized mu-Opioid Receptors, Cells 2 (2013) 689–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].al-Aoukaty A, Schall TJ, Maghazachi AA, Differential coupling of CC chemokine receptors to multiple heterotrimeric G proteins in human interleukin-2-activated natural killer cells, Blood 87 (1996) 4255–4260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pello OM, Martinez-Munoz L, Parrillas V, Serrano A, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Toro MJ, Lucas P, Monterrubio M, Martinez AC, Mellado M, Ligand stabilization of CXCR4/delta-opioid receptor heterodimers reveals a mechanism for immune response regulation, Eur. J. Immunol 38 (2008) 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Strazza M, Banerjee A, Alexaki A, Passic SR, Meucci O, Pirrone V, Wigdahl B, Nonnemacher MR, Effect of mu-opioid agonist DAMGO on surface CXCR4 and HIV-1 replication in TF-1 human bone marrow progenitor cells, BMC Res. Notes 7 (2014) 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Heinisch S, Palma J, Kirby LG, Interactions between chemokine and mu-opioid receptors: anatomical findings and electrophysiological studies in the rat periaqueductal grey, Brain Behav. Immun 25 (2011) 360–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nash B, Meucci O, Functions of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in the central nervous system and its regulation by mu-opioid receptors, Int. Rev. Neurobiol 118 (2014) 105–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Berque-Bestel I, Lezoualc’h F, Jockers R, Bivalent ligands as specific pharmacological tools for G protein-coupled receptor dimers, Curr. Drug Discov. Technol 5 (2008) 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Reaux-Le Goazigo A, Rivat C, Kitabgi P, Pohl M, Melik Parsadaniantz S, Cellular and subcellular localization of CXCL12 and CXCR4 in rat nociceptive structures: physiological relevance, Eur. J. Neurosci 36 (2012) 2619–2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hubner H, Schellhorn T, Gienger M, Schaab C, Kaindl J, Leeb L, Clark T, Moller D, Gmeiner P, Structure-guided development of heterodimer-selective GPCR ligands, Nat. Commun 7 (2016) 12298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Akgun E, Javed MI, Lunzer MM, Smeester BA, Beitz AJ, Portoghese PS, Ligands that interact with putative MOR-mGluR5 heteromer in mice with inflammatory pain produce potent antinociception, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) 11595–11599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Akgun E, Javed MI, Lunzer MM, Powers MD, Sham YY, Watanabe Y, Portoghese PS, Inhibition of Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain by Targeting a Mu Opioid Receptor/Chemokine Receptor5 Heteromer (MOR-CCR5), J. Med. Chem 58 (2015) 8647–8657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Arnatt CK, Falls BA, Yuan Y, Raborg TJ, Masvekar RR, El-Hage N, Selley DE, Nicola AV, Knapp PE, Hauser KF, Zhang Y, Exploration of bivalent ligands targeting putative mu opioid receptor and chemokine receptor CCR5 dimerization, Bioorg. Med. Chem 24 (2016) 5969–5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reinecke BA., Kang G., Zheng Y., Obeng S., Zhang H., Selley DE., An J., Zhang Y., Design and synthesis of a bivalent probe targeting the putative mu opioid receptor and chemokine receptor CXCR4 heterodimer, RSC Med. Chem 11 (2019) 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, Weber R, Fux C, Furrer H, Chave JP, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Calmy A, Vernazza P, Khoo S, Ledergerber B, Back D, Battegay M, Swiss HIVCS, Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, Antivir. Ther 15 (2010) 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ma H, Wang H, Li M, Barreto-de-Souza V, Reinecke BA, Gunta R, Zheng Y, Kang G, Nassehi N, Zhang H, An J, Selley DE, Hauser KF, Zhang Y, Bivalent Ligand Aiming Putative Mu Opioid Receptor and Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 Dimers in Opioid Enhanced HIV-1 Entry, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 11 (2020) 2318–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hutchinson MR, Shavit Y, Grace PM, Rice KC, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia, Pharmacol. Rev 63 (2011) 772–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Milligan ED, Watkins LR, Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 10 (2009) 23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, Kato HE, Livingston KE, Thorsen TS, Kling RC, Granier S, Gmeiner P, Husbands SM, Traynor JR, Weis WI, Steyaert J, Dror RO, Kobilka BK, Structural insights into micro-opioid receptor activation, Nature 524 (2015) 315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wu B, Chien EY, Mol CD, Fenalti G, Liu W, Katritch V, Abagyan R, Brooun A, Wells P, Bi FC, Hamel DJ, Kuhn P, Handel TM, Cherezov V, Stevens RC, Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists, Science 330 (2010) 1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cherner M, Masliah E, Ellis RJ, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Grant I, Heaton RK, Neurocognitive dysfunction predicts postmortem findings of HIV encephalitis, Neurology 59 (2002) 1563–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zheng Y, Akgun E, Harikumar KG, Hopson J, Powers MD, Lunzer MM, Miller LJ, Portoghese PS, Induced association of mu opioid (MOP) and type 2 cholecystokinin (CCK2) receptors by novel bivalent ligands, J. Med. Chem 52 (2009) 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Le Naour M, Akgun E, Yekkirala A, Lunzer MM, Powers MD, Kalyuzhny AE, Portoghese PS, Bivalent ligands that target mu opioid (MOP) and cannabinoid1 (CB1) receptors are potent analgesics devoid of tolerance, J. Med. Chem 56 (2013) 5505–5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Neumeyer JL, Zhang A, Xiong W, Gu XH, Hilbert JE, Knapp BI, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bidlack JM, Design and synthesis of novel dimeric morphinan ligands for kappa and mu opioid receptors, J. Med. Chem 46 (2003) 5162–5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rook Y, Schmidtke KU, Gaube F, Schepmann D, Wunsch B, Heilmann J, Lehmann J, Winckler T, Bivalent beta-Carbolines as Potential Multitarget Anti-Alzheimer Agents, J. Med. Chem 53 (2010) 3611–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schmidhammer H, Deeter JB, Jones ND, Leander JD, Schoepp DD, Swartzendruber JK, Synthesis, Structure Elucidation, and Pharmacological Evaluation of 5-Methyl-Oxymorphone (=4,5 Alpha-Epoxy-3,14-Dihydroxy-5,17-Dimethylmorphinan-6-One), Helv. Chim. Acta, 71 (1988) 1801–1804. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sayre LM, Portoghese PS, Stereospecific Synthesis of the 6-Alpha-Amino and 6-Beta-Amino Derivatives of Naltrexone and Oxymorphone, J. Org. Chem 45 (1980) 3366–3368. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ben Haddou T, Beni S, Hosztafi S, Malfacini D, Calo G, Schmidhammer H, Spetea M, Pharmacological investigations of N-substituent variation in morphine and oxymorphone: opioid receptor binding, signaling and antinociceptive activity, PloS one 9 (2014) e99231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Thoma G, Streiff MB, Kovarik J, Glickman F, Wagner T, Beerli C, Zerwes HG, Orally bioavailable isothioureas block function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in vitro and in vivo, J. Med. Chem 51 (2008) 7915–7920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Haas R, Smith J, Rocher-Ros V, Nadkarni S, Montero-Melendez T, D’Acquisto F, Bland EJ, Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C, Perretti M, Marelli-Berg FM, Mauro C, Lactate Regulates Metabolic and Pro-inflammatory Circuits in Control of T Cell Migration and Effector Functions, PLoS biology 13 (2015) e1002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim TJ, Freml L, Park SS, Brennan TJ, Lactate concentrations in incisions indicate ischemic-like conditions may contribute to postoperative pain, J. Pain 8 (2007) 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Diester CM, Santos EJ, Moerke MJ, Negus SS, Behavioral Battery for Testing Candidate Analgesics in Mice. I. Validation with Positive and Negative Controls, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 377 (2021) 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Al Shoyaib A, Archie SR, Karamyan VT, Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should it Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies?, Pharm. Res 37 (2019) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Shonberg J, Scammells PJ, Capuano B, Design strategies for bivalent ligands targeting GPCRs, ChemMedChem 6 (2011) 963–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Childs-Disney JL, Hoskins J, Rzuczek SG, Thornton CA, Disney MD, Rationally designed small molecules targeting the RNA that causes myotonic dystrophy type 1 are potently bioactive, ACS Chem. Biol 7(2012) 856–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Obeng S, Wang H, Jali A, Stevens DL, Akbarali HI, Dewey WL, Selley DE, Zhang Y, Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of 6alpha- and 6beta-Indolylacetamidonaltrexamine Derivatives as Bitopic Mu Opioid Receptor Modulators and Elaboration of the “Message-Address Concept” To Comprehend Their Functional Conversion, ACS Chem. Neurosci 10 (2018) 1075–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang H, Reinecke BA, Zhang Y, Computational insights into the molecular mechanisms of differentiated allosteric modulation at the mu opioid receptor by structurally similar bitopic modulators, J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des 34 (2020) 879–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Li G, Aschenbach LC, Chen J, Cassidy MP, Stevens DL, Gabra BH, Selley DE, Dewey WL, Westkaemper RB, Zhang Y, Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 6alpha- and 6beta-N-heterocyclic substituted naltrexamine derivatives as mu opioid receptor selective antagonists, J. Med. Chem 52 (2009) 1416–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Ritchie DW, Recent progress and future directions in protein-protein docking, Curr. Protein Pept. Sci 9(2008) 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.