Abstract

Introduction:

Patients who initially survive opioid-related overdose are at high risk for subsequent mortality. Our health system aimed to evaluate the presence of disparities in prescribing naloxone following opioid overdose.

Methods:

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in our health system, which comprises two academic centers and eight community hospitals. Eligible patients had at least one visit to any of our hospital’s emergency departments (EDs) with a diagnosis code indicating opioid-related overdose between May 1, 2018, and April 30, 2021. The primary outcome measure was prescription of nasal naloxone after at least one visit for opioid-related overdose during the study period.

Results:

The health system had 1,348 unique patients who presented 1,593 times to at least one of the EDs with opioid overdose. Of included patients, 580 (43.2%) received one or more prescriptions for naloxone. The majority (68.9%, n=925) were male. For race/ethnicity, 74.5% (1,000) were Non-Hispanic White, 8.0% (n=108) were Non-Hispanic Black, and 13.0% (n=175) were Hispanic/Latinx. Compared with the reference age group of 16–24 years, only those 65+ were less likely to receive naloxone (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.41, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.20–0.84). The study found no difference for gender (male aOR 1.23, 95% CI 0.97–1.57 compared to female). Hispanic/Latinx patients were more likely to receive a prescription when compared to Non-Hispanic White patients (aOR 1.72, 95% CI 1.22-2.44), while no difference occurred between Non-Hispanic Black compared to Non-Hispanic White patients (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 0.87-1.98).

Conclusions:

Naloxone prescribing after overdose in our system was suboptimal, with fewer than half of patients with an overdose diagnosis code receiving this lifesaving and evidence-based intervention. Patients who were Hispanic/Latinx were more likely to receive naloxone than other race and ethnicity groups, and patients who were older were less likely to receive it. Health systems need ongoing equity-informed implementation of programs to expand access to naloxone to all patients at risk.

1. Introduction

Patients who are discharged after an opioid-related overdose are at high risk for mortality. Recent studies show that one-year mortality of patients discharged from the emergency department (ED) after overdose ranged from 5.3-5.5%, meaning that roughly 1 of every 20 patients was dead within a year (Leece et al., 2020; Weiner et al., 2020)). It is particularly concerning given that most deaths occurred in those under age 55 (Wilson et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the problem (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), and the United States recently experienced its highest ever annual all-cause overdose-related deaths, with >100,000 lives lost in the 12-month period ending in April 2021 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2022).

Just as COVID-19 has disproportionately affected minoritized groups (Dixon et al., 2021), so too has the opioid overdose epidemic. In Philadelphia, numbers of overdoses among Black people during the pandemic exceeded those of White individuals for the first time in recent history (Khatri et al., 2021). Disparities have also been reported in Alabama (Patel et al., 2021) and Kentucky (Ochalek et al., 2020), and a nationwide study reported that overdose-associated cardiac arrests rose about 40% nationally in 2020, with larger relative increases seen among Black and Latinx patients (Friedman et al., 2021). In the state where we primarily practice (Massachusetts), opioid-related overdose deaths increased by 5% in 2020 compared with 2019, but the increase specifically among Black men was 69% (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2021). Between 2019 and 2020, the number of overdose-related deaths decreased for White individuals but increased for Black individuals in Massachusetts (DiGennaro et al., 2021).

As society works to identify primary prevention and secondary prevention of overdoses, such as implementation of prevention programs and prescribed drug diversion monitoring, there is an urgent need for tertiary prevention (rescuing the patient at the time of an overdose) (Mathis et al., 2018). The primary means of saving lives after an opioid overdose is naloxone (Mathis et al., 2018). Community-wide distribution of naloxone is an evidence-based intervention to reduce overdose deaths (Walley et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2014; Wheeler, 2015). Providing a naloxone rescue kit after an opioid overdose is also effective (McDonald & Strang, 2016; Strang et al., 2019; Moustaqim-Barrette et al., 2021). Guidance has been published by the American College of Emergency Physicians to encourage take-home naloxone programs, eliminating any barriers to receiving the kits (Samuels et al., 2015). At several hospitals in our health system, in addition to the ability for providers to write a prescription for naloxone, protocols are in place to dispense naloxone directly to at-risk patients.

Given the recent racial and ethnic disparities in opioid-related overdose and death reported in the literature, our health system aimed to evaluate the presence of disparities in prescription of naloxone following an opioid overdose visit to any of our hospitals’ EDs. In this analysis, we evaluated differences in age, gender, race/ethnicity, and primary language of the patient. If disparities exist, they may represent an opportunity for process improvement and clinician education.

2. Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients seen in two large academic centers and seven community hospitals in Massachusetts and one community hospital in New Hampshire. The combined annual number of ED visits is approximately 400,000. In November 2020, our system implemented a deliberate program to address disparities in healthcare entitled United Against Racism, and this project was part of our substance use steering committee’s efforts at identifying differences in substance use disorder-related care. The Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee approved the protocol.

Patients eligible for inclusion in the study were those who had at least one visit to any of our hospitals’ EDs with a diagnosis code indicating opioid-related overdose (Appendix 1) between May 1, 2018 and April 30, 2021. The primary outcome measure was prescription (including written prescription or dispensation) of nasal naloxone during at least one visit for opioid-related overdose. The prescription could have occurred at ED discharge or after discharge from hospitalization if the patient was admitted but was included only if the treatment episode began with an ED visit for overdose. Prescription rates were then analyzed for differences by comparing: 1) age at incidence of first overdose during the study period binned into categories (for patient confidentiality); 2) gender (as indicated by the patient); 3) a combined variable of race and ethnicity; and 4) primary language. Demographic data are self-reported and input by registration staff the first time the patient visits our healthcare system. For individuals who present unconscious, information from ambulance personnel or patient identification cards is used and confirmed with the patient whenever possible. To avoid potential multicollinearity between race and ethnicity, those variables were combined into the categories “Hispanic,” “Non-Hispanic White,” “Non-Hispanic Black,” “Non-Hispanic Other,” and “Unknown” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018). These data are contained in our electronic health record and are input when a patient is first registered in our hospital system.

Data are first presented using descriptive statistics with unadjusted chi-square analysis comparing categorical variables against the primary outcome. We then conducted a multivariable logistic regression model to determine association of demographics with the naloxone prescription outcome. A Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p>.05) revealed adequate model fit and generalized variance inflation factors (GVIF) computed with the R package “car” (Fox & Sage, 2019) indicated low concern for multicollinearity (GVIF values were < 2.0). R version 4.0.3 was used for all analyses.

3. Results

During the study period, there were 1,348 unique patients who presented 1,593 times to one of our EDs with opioid overdose. Evaluating unique visits, the individual hospital rate of prescribing ranged from 13.3% to 65.6%. The two academic medical centers were more likely to prescribe compared to the eight community hospitals (42.8% vs 37.9%, p=0.037). The most common dispositions were: discharge from the ED (73.0%, n=1161), admission to hospital (13.9%, n=222) and eloped/left against medical advice (9.7%, n=155). The rate of naloxone prescribing after each of these dispositions was: 45.6% (n=529) for discharged patients, 21.6% (n=48) for admitted patients, and 30.3% (n=47) for patients who eloped/left without being seen.

As the primary outcome of the study was to ascertain prescription of at least one naloxone kit and several patients presented more than once for overdose, the remainder of the analyses are at the patient level. Six patients were excluded from further analysis because of missing values in the age variable. There were no missing gender values. Of included patients, 580 (43.2%) received at least one prescription for naloxone after any ED visit. Demographic characteristics and naloxone prescription rates are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of included patients and naloxone prescription rates.

| Naloxone Prescribed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total | Yes | No | p value1 | ||

| n=1,342 | n=580 (43.2%) | n=762 (56.8%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Age Group (years) | 16-24 | 64 (4.8%) | 31 (5.3%) | 33 (4.3%) | 0.01 |

| 25-34 | 384 (28.6%) | 187 (32.2%) | 197 (25.9%) | ||

| 35-44 | 422 (31.4%) | 181 (31.2%) | 241 (31.6%) | ||

| 45-54 | 224 (16.7%) | 90 (15.5%) | 134 (17.6%) | ||

| 55-64 | 170 (12.7%) | 71 (12.2%) | 99 (13.0%) | ||

| 65+ | 78 (5.8%) | 20 (3.4%) | 58 (7.6%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | Female | 417 (31.1%) | 164 (28.3%) | 253 (33.2%) | 0.06 |

| Male | 925 (68.9%) | 416 (71.7%) | 509 (66.8%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latinx | 175 (13.0%) | 93 (16.0%) | 82 (10.8%) | 0.004 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 108 (8.0%) | 49 (8.4%) | 59 (7.7%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,000 (74.5%) | 403 (69.5%) | 597 (78.3%) | ||

| Other2 | 32 (2.4%) | 20 (3.4%) | 12 (1.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 27 (2.0%) | 15 (2.6%) | 12 (1.6%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Primary Language | English | 1,293 (96.3%) | 561 (96.7%) | 732 (96.1%) | 0.89 |

| Non-English | 32 (2.4%) | 12 (2.1%) | 20 (2.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 17 (1.3%) | 7 (1.2%) | 10 (1.3%) | ||

P-values calculated with Chi-square analysis. Bolded values indicate results statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

The “Other” race/ethnicity category included Asian (n=10), American Indian or Alaska Native (n=1), two or more (n=13), and “other”, as recorded in our electronic health record (n=8).

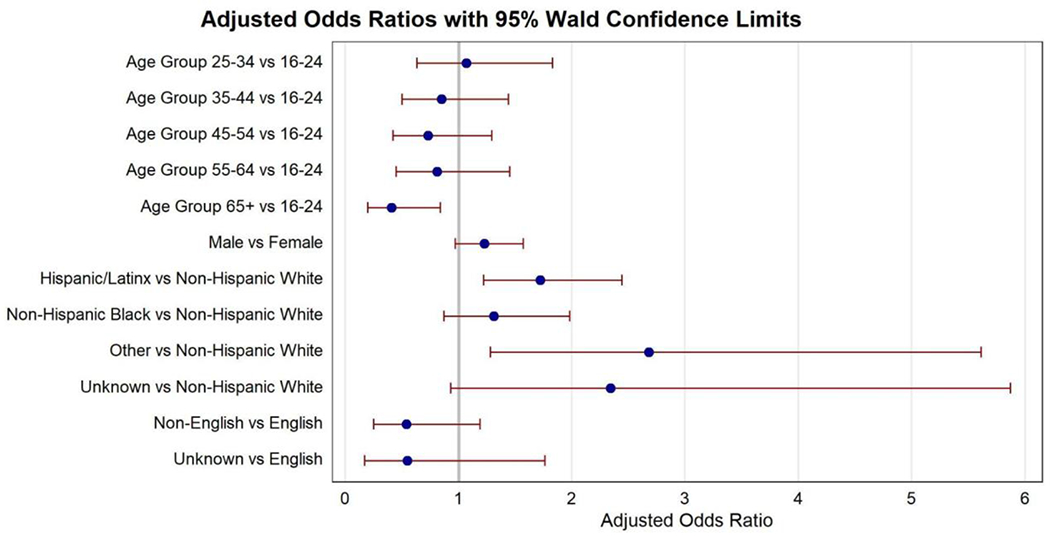

Table 2 and Figure 1 demonstrate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) estimates. When compared to the 16–24-year age group, those older than age 65 were less likely to receive naloxone (aOR 0.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20-0.84). When compared to the non-Hispanic White group, patients who were Hispanic/Latinx were more likely to receive naloxone (aOR 1.72, 95% CI 1.22-2.44), as were those with “other” race/ethnicity (aOR 2.68, 95% CI 1.28-5.61). Notably, there were no differences seen among other age groups, patient gender, or primary language, including no significant difference between non-Hispanic Black patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 0.87-1.98).

Table 2:

Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for receiving a prescription for naloxone (n=1,342).

| Effect | aOR | 95% Confidence Interval1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age Group (Years) | 16-24 | ref | |

| 25-34 | 1.07 | 0.63-1.83 | |

| 35-44 | 0.85 | 0.50-1.44 | |

| 45-54 | 0.73 | 0.42-1.29 | |

| 55-64 | 0.81 | 0.45-1.45 | |

| 65+ | 0.41 | 0.20-0.84 | |

|

| |||

| Gender | Female | ref | |

| Male | 1.23 | 0.97-1.57 | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | ref | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1.72 | 1.22-2.44 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.31 | 0.87-1.98 | |

| Other | 2.68 | 1.28-5.61 | |

| Unknown | 2.34 | 0.93-5.87 | |

|

| |||

| Language | English | ref | |

| Non-English | 0.54 | 0.25-1.19 | |

| Unknown | 0.55 | 0.17-1.76 | |

Bolded values indicate results statistically significant at the p<0.05 level.

Figure 1:

Adjusted odds ratios of compared values for receiving a prescription for naloxone.

4. Discussion

In this analysis of patients who survived opioid overdose and who were treated in one of our health system’s EDs, less than half (43.2%) received either a prescription for naloxone or take-home naloxone. This suboptimal implementation of naloxone for a high-risk patient group indicates the need for ongoing quality improvement. Furthermore, there were differences seen between groups who received naloxone based on age and race/ethnicity. A low rate of prescribing has been described in other hospitals as well. In a study from Ohio, another state with high incidence of opioid overdose, 30.9% of patients received naloxone at ED discharge (Lane et al., 2021). In Alberta, Canada, 49% of eligible ED patients were offered take-home naloxone, with higher rates of offering to those who were found unconscious or if they had used an illegal opioid (O’Brien et al., 2019). An exception is in Rhode Island, where a comprehensive post-overdose care pathway led to 66% of eligible ED patients receiving naloxone (Reddy et al., 2021). Other studies, however, have reported lower rates, such as 25.1% in Illinois, where there were informational and financial barriers to program development (Eswaran et al., 2020) and another ED where naloxone prescribing was low enough (16.3%), that it prompted the investigators to create an electronic health record automated prompt to remind providers to prescribe naloxone, an intervention which was effective (Marino et al., 2019).

One possible explanation for the suboptimal rates may be failures at the provider level or system level to offer naloxone to patients. Although one study found that while emergency physicians were willing to perform opioid-related harm reduction interventions, including prescribing naloxone, many lacked confidence to do so, and cited inadequate knowledge, time, training and institutional support as barriers (Samuels et al., 2016). A 2019 survey in Massachusetts found that only 64% of emergency physicians felt very prepared to prescribe naloxone to prevent overdoses, 45% believed opioid use disorder to be a treatable disease, and just 10% reported caring for patients with OUD to be satisfying (Davidson et al., 2019), potentially indicating stigma and hopelessness among providers that may discourage providing harm reduction modalities like naloxone. More work is clearly needed to educate clinicians about addiction treatment, the benefits of harm reduction, and the detrimental role of stigma. Another potential reason for suboptimal rates may be patients’ willingness to accept naloxone. The research from Alberta described that naloxone was not accepted in 23.8% of cases in which it was offered, including 27.5% of refusing patients who reported that they already had a kit (O’Brien et al., 2019). A similar study from Vancouver also evaluated reasons why patients accepted a kit, and 65.6% reported saving other people as a reason, which may be a way for prescribers to motivate patients to accept the medicine (Kestler et al., 2019). Analyzing prescribing barriers was out of the scope of this research; however, it is a critical question that warrants further investigation.

The primary goal of our study was to evaluate differences in naloxone receipt by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and primary language. We initially hypothesized that Black and Latinx patients would have been offered naloxone less frequently than White patients because of both individual-level prejudice and systemic racism. Instead, we found no differences between White and Black patients during the time period of our analysis. Furthermore, we discovered that Hispanic/Latinx patients were more likely to receive naloxone at discharge than White patients. While greater naloxone provision to Hispanic/Latinx patients is important given increases in overdose among Hispanic/Latinx patients (Cano, 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Cano, 2021), the reasons for these findings are unclear. One optimistic possibility is that these findings reflect upon our system-wide plan to address race, ethnicity, and language disparities (Kilbanski, 2020). However, it is also possible that this increased likelihood of prescribing naloxone to Hispanic/Latinx individuals could reflect bias among providers that this population of patients is more at risk of repeat overdose. Analyzing the underlying causes is subject to further analysis. Previous research has demonstrated that providers perceive Black patients to be at higher risk of opioid misuse compared to White patients (Hirsh et al., 2020). In addition, provider bias about non-White patient groups and perceived risk for misuse has been identified as a reason for disparities by race and ethnicity in prescribing opioids to treat pain (Santoro & Santoro, 2018). Likewise, as commercially insured non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals are less likely to receive follow-up for OUD care after opioid overdose (Kilaru et al., 2020), increased naloxone prescribing for certain groups may represent biased thinking among providers that these patients may be less likely to follow up in treatment.

The importance of the ED as a location for dispensing naloxone to all at-risk patients cannot be understated. Our study was unable to determine if the naloxone provided was just a prescription or an actual take-home kit because, in several of our hospitals, the take-home naloxone is dispensed directly to the patient in the ED after a provider writes the prescription. However, take-home naloxone is clearly advantageous, particularly as the barrier to a patient going to a pharmacy to pick up the prescription is significant (Weiner & Hoppe, 2021), co-pays at pharmacies may be an additional barrier (Barenie et al., 2020), and pharmacies in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are less likely to carry naloxone (Egan et al., 2020; Abbas et al., 2021). Removing barriers within the ED itself could also be helpful, including allowing nurses and social workers to dispense naloxone to patients without needing to rely on a provider to write an order or prescription.

We evaluated if there were differences in naloxone provision based on patient age, as we expected differences in the reasons for overdose, such as more prescription opioid (vs. illicit) overdoses and provider expectation of overdose in older adults to be a one-time accident. In the adjusted analysis, we found that patients older than 65 years were less likely to receive naloxone than the reference group (16-24-year-olds). Possible reasons for this may include older adults’ higher likelihood of having an opioid prescription, as found in a Canadian study (O’Brien et al., 2019), in addition to the possibility of not being well-represented in the public perception of who may be at risk for an opioid-related overdose. Unfortunately, the rate of opioid-related hospitalizations for patients aged 65 years and older increased significantly in past years, including a 34.3% increase in opioid-related hospitalizations and a 74.2% increase in opioid-related ED visits between 2010 and 2015 (Weiss et al., 2018), highlighting the importance of also offering naloxone to patients in this age group.

The final outcomes of interest were the determination of whether primary language or gender of the patient was associated with differential rates of naloxone prescription. Language was included in the analysis in case there were barriers to communication which led to differences. In the adjusted analysis, there was not a significant difference between those with English as their primary language and those with other primary languages. Since the percentage of non-English speakers in our cohort was low (2.4%) the lack of difference may be due to inadequate power and should be interpreted with caution. Gender was included given the numerous differences in overdose incidence, outcomes, and comorbidities between the sexes (McHugh, 2020). Our study found no differences in naloxone prescribing to females vs. males. However, we were unable to identify patients who were transgender or gender diverse from our electronic health record data, and some of these individuals have unmet behavioral health needs (Hughto et al., 2021). Larger studies are needed to better assess possible differences in both patient characteristics.

Our study is subject to several limitations. This was a retrospective study which relied on diagnosis codes and may have not included patients for whom our studied diagnoses codes were not documented. Also, we were unable to determine if the naloxone was prescribed or dispensed, and we were unable to capture if naloxone was offered but refused by the patient, a datapoint which may be important to record in the future should naloxone prescribing after non-fatal overdose become more frequently used as a quality measure. We did not limit the analysis to patients who were discharged from the ED, as we wanted to capture prescription of naloxone at any point in their care, including after hospital admission or if they eloped/left without being seen. Although we measured patient-level factors, we did not investigate differences in the characteristics of the providers caring for the patients, which may have influenced outcomes. We also did not examine reasons why different hospitals had different rates of naloxone prescribing and if there are underlying socioeconomic factors in these communities which contribute to these differences. Finally, Massachusetts has suffered disproportionately from the opioid overdose epidemic (Friedman & Akre, 2021) and has stringent laws mandating provision of medication for opioid use disorder to eligible patients from EDs (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2018). As a result, the EDs may be more apt to provide naloxone compared with other states.

In conclusion, naloxone prescribing after an opioid overdose in our system was suboptimal, with fewer than half of patients with an overdose diagnosis code receiving this lifesaving and evidence-based intervention. Furthermore, patients who were Hispanic/Latinx were more likely to receive it than other race and ethnicity groups, and patients who were older were less likely to receive it, findings which warrant attention and are being shared with providers in our health system. Further evaluation of reasons for differences in naloxone prescribing by ethnicity and age could validate these findings and guide future interventions to improve naloxone access. Ongoing implementation of programs to expand access to naloxone through hospitals is needed, like the “Levels of Care” project in Rhode Island (Samuels et al., 2021), which combined naloxone distribution with behavioral counseling, referral to treatment, and buprenorphine treatment initiation for patients who survived an overdose.

Supplementary Material

Financial support:

SGW reports grant money to Brigham and Women’s Hospital to conduct research conceived and written by SGW from the National Institutes of Health, NIH 5-R01-DA044167.

Footnotes

Presentations: An abstract based on this work was presented at the American Society of Addiction Medicine 53rd Annual Conference, Hollywood, FL, April, 2022.

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Scott G. Weiner, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Aleta D. Carroll, Mass General Brigham, Somerville, MA.

Nicholas M. Brisbon, Mass General Brigham, Somerville, MA.

Claudia P. Rodriguez, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Charles Covahey, Mass General Brigham, Somerville, MA.

Erin J. Stringfellow, MGH Institute for Technology Assessment, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Catherine DiGennaro, MGH Institute for Technology Assessment, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Mohammad S. Jalali, MGH Institute for Technology Assessment, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Sarah E. Wakeman, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

References

- Abbas B, Marotta PL, Goddard-Eckrich D, Huang D, Schnaidt J, El-Bassel N, & Gilbert L (2021). Socio-ecological and pharmacy-level factors associated with naloxone stocking at standing-order naloxone pharmacies in New York City. Drug and alcohol dependence, 218, 108388. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2018). Defining Categorization Needs for Race and Ethnicity Data. Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/iomracereport/reldata3.html. [Google Scholar]

- Barenie RE, Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS, Pawar A, Tong A, Luo J, & Bateman BT (2020). Rates and Costs of Dispensing Naloxone to Patients at High Risk for Opioid Overdose in the United States, 2014-2018. Drug safety, 43(7), 669–675. 10.1007/s40264-020-00923-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M (2021). Racial/ethnic differences in US drug overdose mortality, 2017-2018. Addictive behaviors, 112, 106625. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M (2020). Drug Overdose Deaths Among US Hispanics: Trends (2000-2017) and Recent Patterns. Substance use & misuse, 55(13), 2138–2147. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1793367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Overdose Deaths Accelerating during COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html.

- Chen W, Page TF, & Sun W (2021). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Opioid Use Disorder and Poisoning Emergency Department Visits in Florida. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 8(6), 1395–1405. 10.1007/s40615-020-00901-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AK, Wilder CM, & Winstanley EL (2014). A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. Journal of addiction medicine, 8(3), 153–163. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts (2018). Chapter 208 of the Acts of 2018: An Act for Prevention and Access to Appropriate Care and Treatment of Addiction. https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2018/Chapter208.

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts (2021). Opioid-related overdose deaths rose by 5 percent in 2020. https://www.mass.gov/news/opioid-related-overdose-deaths-rose-by-5-percent-in-2020.

- Davidson C, Bansal C, & Hartley S (2019). Opportunities to increase screening and treatment of opioid use disorder among healthcare professionals. https://rizema.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/GE-Rize-Shatterproof-White-Paper-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- DiGennaro C, Garcia GP, Stringfellow EJ, Wakeman S, & Jalali MS (2021). Changes in characteristics of drug overdose death trends during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International journal on drug policy, 98, 103392. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon BE, Grannis SJ, Lembcke LR, Valvi N, Roberts AR, & Embi PJ (2021). The synchronicity of COVID-19 disparities: Statewide epidemiologic trends in SARS-CoV-2 morbidity, hospitalization, and mortality among racial minorities and in rural America. PloS one, 16(7), e0255063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KL, Foster SE, Knudsen AN, & Lee J (2020). Naloxone Availability in Retail Pharmacies and Neighborhood Inequities in Access. American journal of preventive medicine, 58(5), 699–702. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswaran V, Allen KC, Cruz DS, Lank PM, McCarthy DM, & Kim HS (2020). Development of a take-home naloxone program at an urban academic emergency department. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA, 60(6), e324–e331. 10.1016/j.japh.2020.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, & Weisberg S (2019). An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J, Mann NC, Hansen H, Bourgois P, Braslow J, Bui A, Beletsky L, & Schriger DL (2021). Racial/Ethnic, Social, and Geographic Trends in Overdose-Associated Cardiac Arrests Observed by US Emergency Medical Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA psychiatry, 78(8), 886–895. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J, & Akre S (2021). COVID-19 and the Drug Overdose Crisis: Uncovering the Deadliest Months in the United States, January–July 2020. American journal of public health, 111(7), 1284–1291. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh AT, Anastas TM, Miller MM, Quinn PD, & Kroenke K (2020). Patient race and opioid misuse history influence provider risk perceptions for future opioid-related problems. The American psychologist, 75(6), 784–795. 10.1037/amp0000636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto J, Restar AJ, Wolfe HL, Gordon LK, Reisner SL, Biello KB, Cahill SR, & Mimiaga MJ (2021). Opioid pain medication misuse, concomitant substance misuse, and the unmet behavioral health treatment needs of transgender and gender diverse adults. Drug and alcohol dependence, 222, 108674. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler A, Giesler A, Buxton J, Meckling G, Lee M, Hunte G, Wilkins J, Marks D, & Scheuermeyer F (2019). Yes, not now, or never: an analysis of reasons for refusing or accepting emergency department-based take-home naloxone. CJEM, 21(2), 226–234. 10.1017/cem.2018.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri UG, Pizzicato LN, Viner K, Bobyock E, Sun M, Meisel ZF, & South EC (2021). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Unintentional Fatal and Nonfatal Emergency Medical Services-Attended Opioid Overdoses During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Philadelphia. JAMA network open, 4(1), e2034878. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilaru AS, Xiong A, Lowenstein M, Meisel ZF, Perrone J, Khatri U, Mitra N, & Delgado MK (2020). Incidence of Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Following Nonfatal Overdose in Commercially Insured Patients. JAMA network open, 3(5), e205852. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbanksi A (2020). Mass General Brigham President and CEO’s Update to Employees On Racial Injustice. https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/newsroom/articles/mass-general-brigham-president-and-ceos-update-employees-racial-injustice.

- Lane BH, Lyons MS, Stolz U, Ancona RM, Ryan RJ, & Freiermuth CE (2021). Naloxone provision to emergency department patients recognized as high-risk for opioid use disorder. The American journal of emergency medicine, 40, 173–176. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.10.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leece P, Chen C, Manson H, Orkin AM, Schwartz B, Juurlink DN, & Gomes T (2020). One-Year Mortality After Emergency Department Visit for Nonfatal Opioid Poisoning: A Population-Based Analysis. Annals of emergency medicine, 75(1), 20–28. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino R, Landau A, Lynch M, Callaway C, & Suffoletto B (2019). Do electronic health record prompts increase take-home naloxone administration for emergency department patients after an opioid overdose?. Addiction (Abingdon, England: ), 114(9), 1575–1581. 10.1111/add.14635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis SM, Hagemeier N, Hagaman A, Dreyzehner J, & Pack RP (2018). A Dissemination and Implementation Science Approach to the Epidemic of Opioid Use Disorder in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS reports, 15(5), 359–370. 10.1007/s11904-018-0409-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, & Strang J (2016). Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria. Addiction (Abingdon, England: ), 111(7), 1177–1187. 10.1111/add.13326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK (2020). The Importance of Studying Sex and Gender Differences in Opioid Misuse. JAMA network open, 3(12), e2030676. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustaqim-Barrette A, Dhillon D, Ng J, Sundvick K, Ali F, Elton-Marshall T, Leece P, Rittenbach K, Ferguson M, & Buxton JA (2021). Take-home naloxone programs for suspected opioid overdose in community settings: a scoping umbrella review. BMC public health, 21(1), 597. 10.1186/s12889-021-10497-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2022). Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm.

- O’Brien DC, Dabbs D, Dong K, Veugelers PJ, & Hyshka E (2019). Patient characteristics associated with being offered take home naloxone in a busy, urban emergency department: a retrospective chart review. BMC health services research, 19(1), 632. 10.1186/s12913-019-4469-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, Gal TS, & Moeller FG (2020). Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses at an Urban Emergency Department During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA, 324(16), 1673–1674. 10.1001/jama.2020.17477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel I, Walter LA, & Li L (2021). Opioid overdose crises during the COVID-19 pandemic: implication of health disparities. Harm reduction journal, 18(1), 89. 10.1186/s12954-021-00534-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy NG, Jacka B, Ziobrowski HN, Wilson T, Lawrence A, Beaudoin FL, & Samuels EA (2021). Race, ethnicity, and emergency department post-overdose care. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 131, 108588. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels EA, Hoppe J, Papp J, Whiteside L, Raja AS, & Bernstein E (2015). Emergency Department Naloxone Distribution: Key Considerations and Implementation Strategies. https://prescribetoprevent.org/wp2015/wp-content/uploads/TIPSWhitePaper.pdf.

- Samuels EA, Dwyer K, Mello MJ, Baird J, Kellogg AR, & Bernstein E (2016). Emergency Department-based Opioid Harm Reduction: Moving Physicians From Willing to Doing. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 23(4), 455–465. 10.1111/acem.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels EA, Wentz A, McCormick M, McDonald JV, Marshall B, Friedman C, Koziol J, & Alexander-Scott NE (2021). Rhode Island’s Opioid Overdose Hospital Standards and Emergency Department Naloxone Distribution, Behavioral Counseling, and Referral to Treatment. Annals of emergency medicine, 78(1), 68–79. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro TN, & Santoro JD (2018). Racial Bias in the US Opioid Epidemic: A Review of the History of Systemic Bias and Implications for Care. Cureus, 10(12), e3733. 10.7759/cureus.3733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McDonald R, Campbell G, Degenhardt L, Nielsen S, Ritter A, & Dale O (2019). Take-Home Naloxone for the Emergency Interim Management of Opioid Overdose: The Public Health Application of an Emergency Medicine. Drugs, 79(13), 1395–1418. 10.1007/s40265-019-01154-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, Ruiz S, & Ozonoff A (2013). Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 346, f174. 10.1136/bmj.f174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, & Schuur JD (2020). One-Year Mortality of Patients After Emergency Department Treatment for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. Annals of emergency medicine, 75(1), 13–17. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner SG, & Hoppe JA (2021). Prescribing Naloxone to High-Risk Patients in the Emergency Department: Is it Enough?. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety, 47(6), 340–342. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss AJ, Heslin KC, Barrett ML, Izar R, & Bierman AS (2018). Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits Among Patients Aged 65 Years and Older, 2010 and 2015: Statistical Brief #244. In Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2015). Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons - United States, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 64(23), 631–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H 4th, & Davis NL (2020). Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(11), 290–297. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.