Abstract

Oral amelanotic melanoma (OAM) is a rare, non-pigmented mucosal neoplasm representing less than 2% of all melanoma. The present study analyses the available data on OAM and describes its clinicopathological features, identifying potential prognostic factors. Online electronic databases such as PubMed-Medline, Embase, and Scopus were searched using appropriate keywords from the earliest available date till 31st March 2021 without restriction on language. Additional sources like Google Scholar, major journals, unpublished studies, conference proceedings, and cross-references were explored. 37 publications were included for quantitative synthesis, comprising 55 cases. The mean age of the patients was 59.56 years, and the lesions were more prevalent in males than in females. OAM’s were most prevalent in the maxilla (67.2%) with ulceration, pinkish-red color, nodular mass, and pain. 2 patients (3.36%) were alive at their last follow-up, and 25 were dead (45.4%). Univariate survival analysis of clinical variables revealed that age older than 68 years (p = 0.003), mandibular gingiva (p = 0.007), round cells (p = 0.004), and surgical excision along with chemotherapy & radiation therapy (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with a lower survival rate. Oral Amelanotic Melanoma is a neoplasm with a poor prognosis, presenting a 6.25% possibility of survival after 5 years. Patients older than 68 years, lesions in the mandibular gingiva, round cells, and surgical excision along with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, presented the worst prognosis. However, they did not represent independent prognostic determinants for these patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12105-021-01366-w.

Keywords: Melanoma, Oral cavity, Amelanotic, Mucosal melanoma, Oral amelanotic melanoma, Immunohistochemistry, Prognosis

Introduction

Mucosal melanoma (MM) is a malignant neoplasm of melanocytes derived from mucosal sites. The rarest melanoma subtype contrasts with cutaneous melanomas, which are a hundred times more common and biologically distinct. They are caused by unknown factors and exhibit different cytogenetic alterations and clinical course [1]. MM occurs most frequently in the head and neck region (55%), followed by the anogenital site. In the head and neck region, MM represents < 1% of all melanomas and predominantly arises in two primary sites, the sinonasal region (66%) and the oral cavity (25%). Oral mucosal melanoma (OMM) accounts for about 0.5% of melanomas. They frequently occur on the hard palate and gingiva, show a slight male predominance with a median age range of 55–66 years [2].

Amelanotic melanoma (AM) lack pigmentation clinically, with melanin formation in less than 5% of tumor cells on histological examination [3]. Less than 2% of all melanomas lack pigmentation; however, up to 75% of cases are amelanotic in the oral mucosa [4, 5]. Oral amelanotic melanoma (OAM) constitutes 40% of oral MM, and maxillary gingiva is the most commonly involved site followed by the palate; it rarely affects the mandibular gingiva [6]. The neoplasm is often asymptomatic and appears irregular, erythematous, flat, or nodular lesion with ulceration seen in one-third cases [2]. A higher incidence of regional lymph node and distant metastasis, mainly to the lung or the liver, has been reported for OAM [6]. Histologically, OAM displays diverse cell types, which include undifferentiated epithelioid, spindle, and plasmacytoid morphology. Thereby building immunohistochemistry as an essential tool for confirming the tumor phenotype and conclude the diagnosis. An extensive immunohistochemical panel with the marker of neural, neuroendocrine, lymphoid, or epithelioid differentiation is used to rule out other neoplasms [7]. A combination of surgery and surgery with adjuvant therapy is the treatment of choice, while radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone has also been used [6].

Consequently, the absence of melanin pigmentation in OAM, both clinically and microscopically, poses a diagnostic challenge that varies widely, from reactive or nonneoplastic proliferative lesions to infectious diseases and other oral malignancies. This leads to delayed diagnosis, intrinsic aggressiveness with a poor prognosis. Because of the rarity of the neoplasm, few case reports and scarcely any series have been published to date. As a result, it has been difficult to establish valuable data related to OAM. All relevant case series and case reports were systematically reviewed to clarify the natural history and reinforce knowledge about OAMs and epidemiological predilections. The present study conjoins the available data on OAM into an updated extensive review of their clinicopathological, immune profile, therapeutic and prognostic features. This will help further to perceive the possible biologic profile of the tumor and enhance knowledge about this unusual tumor for its timely diagnosis, treatment planning, and outcome.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines [8].

Search Strategy

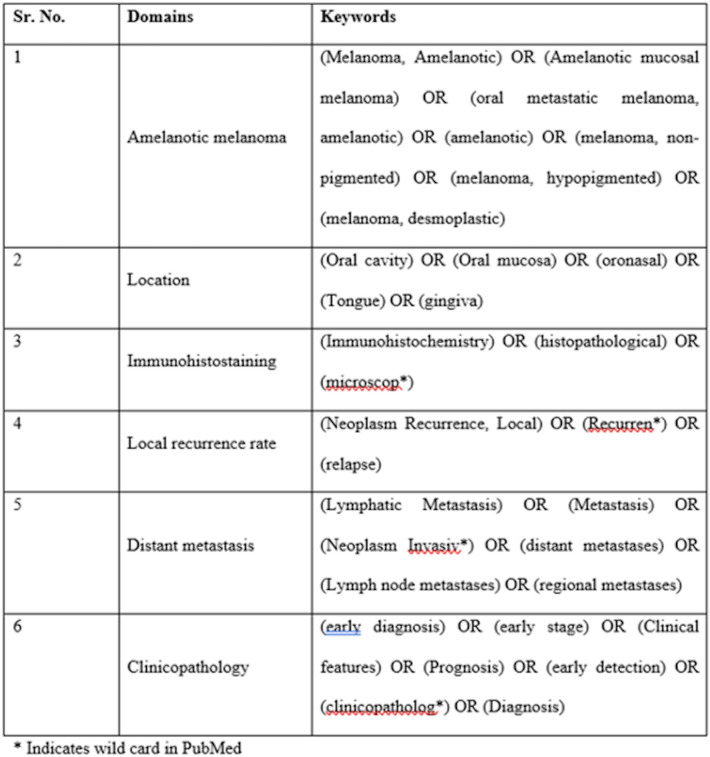

An exhaustive literature search was conducted for the clinical features, immunohistochemistry, histopathological features of Oral Amelanotic Melanoma (OAM), and the rate of metastasis and the prognosis of the disease. Online electronic databases such as PubMed-Medline, Embase, and Scopus were searched from the earliest available date till 31st March 2021 without restriction on language. Additional sources like google scholar, unpublished studies, conference proceedings, and cross-references were explored. Non-English language publications were translated into the English language using Google Translate [9]. We also searched for relevant articles in journals allied to oral pathology, oral medicine, and oral surgery. A detailed search strategy for PubMed is given in Fig. 1 and tailored to other databases when necessary (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Search strategy in PubMed

Eligibility Criteria

Case reports and case series of oral amelanotic melanoma.

Histopathologically confirmed patients and clinically diagnosed as oral amelanotic melanoma.

Patients with primary and secondary oral amelanotic melanoma.

Patients with no other associated malignant tumors orally or extra orally.

Amelanotic Melanoma other than oral cavity and past hospital records were excluded.

Screening and Selection

The papers were independently scanned by two reviewers (SD and VM), first by the title and abstract. Reviews, commentary, or clinical trials were not included in the search. If the search keywords were present in the title and or the abstract, the papers were selected for full‑text reading. Papers without abstracts but with titles suggesting that they were related to the objectives of this review were also selected to screen the full text for eligibility. After selection, full‑text papers were read in detail by two reviewers. (SD and VM) Those papers that fulfilled all of the selection criteria were processed for data extraction. Two reviewers (SD and VM) searched the reference lists of all selected studies for additional relevant articles. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. If a disagreement persisted, the judgment of a third reviewer (SB) was considered decisive.

Risk of Bias

The selection criteria included available information about immunohistochemistry analysis to confirm the diagnosis of OAM, which reduced the risk of bias and the publications with sufficient clinical and histological data. A higher risk of bias is comprised of insufficient clinical, histological and immunohistochemical information to confirm the diagnosis of OAM.

Data Extraction

Two authors (SD and VM) independently extracted data using specially designed data extraction forms, utilizing Microsoft Excel software. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion between the authors. For each selected study, the following data were then extracted from a standard form (when available): author and year of publication, the number of patients, country, location, patient sex (male or female), age, the time elapsed before reporting the case, clinical presentation, radiographic features, histologic features, treatment, prognosis, recurrence, distant metastasis, and outcome of the disease. For those articles that had inadequate data to be included in quantitative synthesis, the corresponding authors were contacted to procure additional data.

Analysis

The data were analyzed using R, version 3.3.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) Confidence intervals were set at 95%, and a p-value ≤ of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The mean and percentages are presented as descriptive data. Overall survival rates were estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared using a log-rank test to identify potential prognostic features.

The systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on March 31, 2021, which was in accordance with the guidelines and was last revised on January 1, 2021. (Registration Number CRD42020216187).

Results

Search Selection and Results

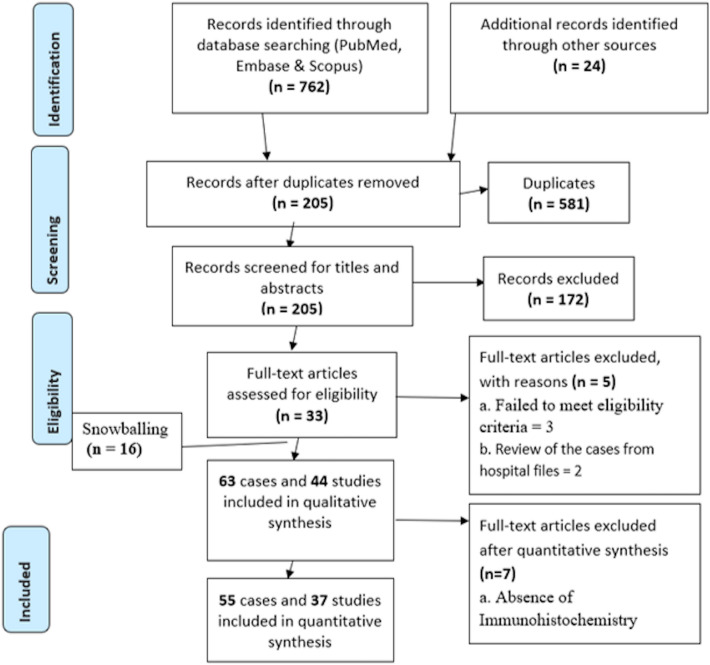

The PubMed-Medline, Embase, Scopus, and additional sources identified 786 search results, out of which 581 were duplicates. The remaining 205 unique studies were screened for the titles and abstracts, and 33 articles were selected for full-text screening (Fig. 2). A total of 44 articles [4, 6, 7, 10–50] that matched the eligibility criteria were processed for data extraction (Supplementary Table 2). Analysis of the remaining 37 articles [4, 6, 7, 13, 14, 16–41, 44, 46–50] resulted in the exclusion of 7 papers [10–12, 15, 42, 43, 45] (Supplementary Table 3) which did not meet the inclusion criteria or provide sufficient clinical, histological and immunohistochemical information to confirm the diagnosis of OAM. Finally, a total of 55 cases were included in the descriptive and statistical analyses.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart summarizing the article selection process (n—number of studies)

Description of the Studies and Analyses

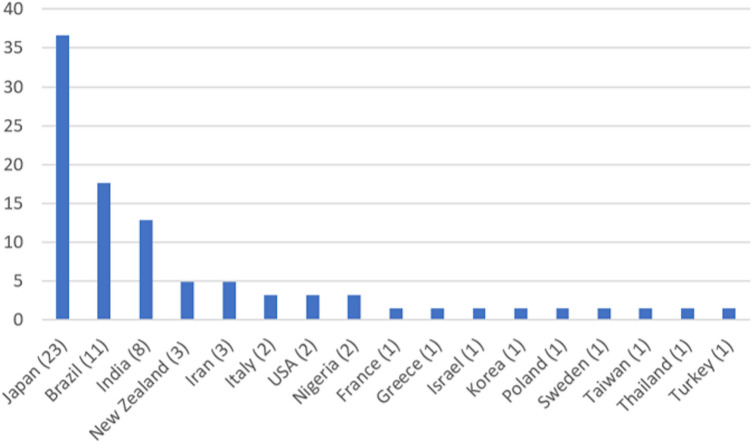

Forty-four publications reporting 63 cases were included for qualitative synthesis (Supplementary Table 3). The epidemiological results are described in Fig. 3, which reveals Japan (23 cases), Brazil (11 cases), India (8 cases), New Zealand, and Iran (3 cases) to be the countries with the highest numbers of cases described. Table 1 presents the demographic, clinical, radiographical, and histological features and the results of the survival analysis. The mean age of the patients was 59.56 years (range 15–97 years); females were older (mean age 62.04 years, range 16–85 years) than males (mean age 57.6 years, range 19–97 years). The lesions were more prevalent in males than in females, with a male to female ratio of 1.29:1. OAM’s were most prevalent in the maxilla (n = 37, 67.2%), mandible (n = 13, 23.6%) and others (n = 5, 9.2%). The mean lesion size was 29.4 × 28.97 × 11.42.

Fig. 3.

Countries with cases of oral amelanotic melanoma described in qualitative synthesis and the number of cases in each country. Japan has reported the most cases, followed by Brazil, India, New Zealand, and Iran

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, clinical features, and survival analysis of cases of oral amelanotic melanoma described in the literature (N = 55)

| Variables | N = 55 | Log-rank univariant survival analysis, p-values |

|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) (mean age − 59.56) | ||

| < 68 years | 36 (65.5%) | 0.003* |

| > 68 years | 19 (35.5%) | |

| Sex, n (%) (male:female ratio—1.29:1) | ||

| Male | 31 (56.4%) | 0.57 |

| Female | 24 (43.6%) | |

| Location: maxilla, 37 (67.2%) | ||

| Hard palate | 17 (30.9%) | 0.10 |

| Gingiva | 15 (27.3%) | |

| Soft palate | 3 (5.5%) | |

| Alveolar ridge | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Location: mandible, 13 (23.6%) | ||

| Mandibular gingiva | 7 (12.7%) | 0.007* |

| Alveolar ridge | 4 (7.3%) | |

| Retro molar | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Location: other, 5 (9.2%) | ||

| Lateral margin of tongue | 2 (3.6%) | 0.76 |

| Anterior 2/3rd tongue | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Buccal mucosa | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Lip | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Clinical features, n (%) | ||

| Ulcerated | 26 (47.2%) | 0.56 |

| Pinkish red color | 19 (34.5%) | |

| Nodular mass | 15 (27.2%) | |

| Sessile | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Pedunculated | 4 (7.27%) | |

| Erythema | 5 (9.09%) | |

| Greyish white color | 2 (3.63%) | |

| Pigmentation in other sites | 3 (5.45%) | |

| Well circumscribed | 3 (5.45%) | |

| Ill-defined | 8 (14.5%) | |

| Mobility in associated tooth | 2 (3.63%) | |

| Asymptomatic | 24 (43.6%) | |

| Pain | 13 (23.6%) | |

| Bleeding | 4 (7.27%) | |

| NA | 14 (25.4%) | |

| First clinical impression, n (%) | ||

| Malignancy | 13 (23.6%) | 0.67 |

| Melanoma | 5 (9.09%) | |

| Epulis | 5 (9.09%) | |

| Benign tumor | 3 (5.45%) | |

| Pyogenic granuloma | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Peripheral giant-cell granuloma (PGCG) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Metastatic tumor | 1 (1.8%) | |

| NA | 25 (45.4%) | |

| Radiographic features, n (%) | ||

| Bone destruction | 24 (43.6%) | 0.58 |

| No abnormality detected | 5 (9.09%) | |

| NA | 26 (47.2%) | |

| Histological features (cell types) n (%) | ||

| Spindle cells | 24 (43.6%) | 0.004* |

| Epithelioid | 12 (21.8%) | |

| Round to spindle cells | 8 (14.5%) | |

| Round cells | 7 (12.72%) | |

| Undifferentiated | 4 (7.27%) | |

| Melanin on histopathology, n (%) | ||

| Present | 5 (9.09%) | 0.65 |

| Absent | 9 (16.3%) | |

| NA | 41 (74.5%) | |

| Lymph node, n (%) | ||

| Present | 27(49.1%) | 0.23 |

| Absent | 23 (41.8%) | |

| NA | 5(9.1%) | |

| Distant metastasis, n (%) | ||

| Present | 14 (25.4%) | |

| Absent | 6 (10.9%) | 0.48 |

| NA | 35 (63.6%) | |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||

| SX + CX | 12 (21.8%) | 0.001* |

| SX | 11 (20%) | |

| SX + RX | 8 (14.5%) | |

| RX | 7 (12.7%) | |

| NA | 6 (10.9%) | |

| No T/t | 4 (7.27%) | |

| CX + RX | 2 (3.6%) | |

| CX + SX + IX | 2 (3.6%) | |

| CX | 1 (1.8%) | |

| SX + CX + RX | 1 (1.8%) | |

| RX + CX + IX | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Recurrence, n (%) | ||

| Absent | 7 (12.7%) | 0.91 |

| Present | 5 (9.09%) | |

| NA | 43 (78.18%) | |

| Status, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 25 (45.4%) | 0.58 |

| Alive | 2 (3.36%) | |

| NA | 28 (50.9%) | |

NA not available, T/t treatment, SX surgical excision, CX chemotherapy, RX radiation therapy, IX immunotherapy

*p-value < 0.05, significant result

The OAM mainly showed ulceration, pinkish-red color, nodular mass, sessile, pain, bleeding, and erythema. Malignancy was described as the first clinical impression of this tumor in 13 (23.6%) patients, followed by melanoma and epulis in 5 (9.09%) patients, benign tumor in 3 (5.45%) patients, pyogenic granuloma in 2 (3.6%) patients, and metastatic tumor and peripheral giant-cell granuloma in 1 (1.8%) patient. Bone destruction was observed in 24 (43.6%) patients. The patients presented a mean duration of lesion evolution of 6.23 months (range 0.5–36 months). Histological analysis revealed different cell types and the presence of melanin in 5 cases (9.09%) and the absence of melanin in 9 cases (16.3%). Lymph nodes were involved in 23 (41.8%) patients, regional lymph nodes were seen in 14 (25.45%), and distant lymph nodes were seen in 6 (10.9%). Metastasis was mainly seen in the lungs, cervical lymph nodes, and liver. Treatment was described for all 55 patients and included surgical excision and chemotherapy (CT) in 12 (21.8%), surgical excision alone in 11 (20%), surgical excision along with radiation therapy (RT) in 8 (14.5%), RT alone in 7 (12.7%), and CT associated with RT and CT along with surgical excision and immunotherapy in 2 (3.6%). A small number of cases (1.8%) underwent CT, surgical excision associated with CT and RT and RT along with CT and immunotherapy. Recurrence was observed in 5 (9.09%) patients. Two patients (3.36%) were alive at their last follow-up, 25 were dead (45.4%), and this information was not available for 28 cases (50.9%).

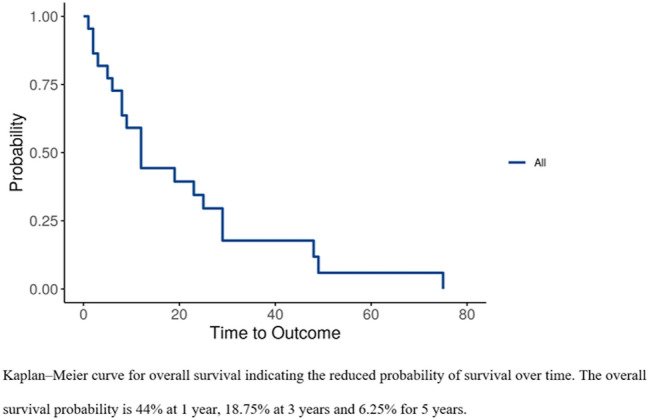

The overall survival probability at 3-years and 5-years is 18.75% and 6.25% respectively (Fig. 4). Univariate survival analysis of clinical variables revealed that age older than 68 years (p = 0.003), mandibular gingiva (p = 0.007), round cells (p = 0.004), and surgical excision along with CT and RT (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with a lower survival rate (Table 1, Fig. 5). The immunohistochemistry panel for OAM is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival indicating the reduced probability of survival over time

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves. A Kaplan–Meier curves for survival associated with age. B Kaplan–Meier curves for survival associated with Mandible location. C Kaplan–Meier curves for survival associated with histological features (cell types). D Kaplan–Meier curves for survival associated with treatment

Table 2.

Markers used in the diagnosis of the cases analyzed (N = 55)

| Immunohistochemistry analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Markers | Positive | Negative |

| HMB-45 | 96.8% | 3.12% |

| S-100 | 95.8% | 4.1% |

| Melan A | 66.6% | 33.3% |

| AE1/AE3 | 11.7% | 88.2% |

| Vimentin | 84.2% | 15.7% |

| Ki-67 | 100% | 0% |

| SOX10 | 100% | 0% |

| Desmin | 12.5% | 87.5% |

| LCA | 0% | 22.7% |

| α-SMA | 0% | 100% |

| EMA | 0% | 100% |

Discussion

Amelanotic melanoma (AM) is a unique subset of melanoma with little or no clinically visible pigmentation and lack of melanin in the cytoplasm of tumor cells, wherein some authors have quantified the presence of melanin in less than 5% of tumor cells [3, 51]. Though AM cells demonstrate melanin-forming ability amelanosis may result from the insufficient activity of specific melanin formation enzymes, such as tyrosinase and germline mutations in genes for MC1R, MITF, and p14ARF. Alcohol, smoking, and exposure to formaldehyde are weakly associated with the pathogenesis of OMM [51–53]. However, the mechanism underlying amelanosis is still unclear. Also there is scarce information on OAM in the literature regarding its clinical course and prognosis, with only a few reports and series currently available. Therefore, we attempted this study to systematically review the available data on OAM to determine the clinicopathological features of this tumor and the affected patients.

The incidence of melanomas differs among different ethnic groups and races. Based on the qualitative synthesis of 63 cases in the present review, the occurrence of OAM was most frequently seen in Japan, followed by Brazil, India, New Zealand, and Iran. Our findings are in accordance with the high incidence of OAMs reported among Japanese than Caucasians by Takagi et al. [54] and Steidler et al. [55]. Also, in Asian/Pacific islanders, more MMs have been reported than non-Hispanic Whites [56, 57]. As there is limited data on intra-oral amelanotic melanoma, most cases are unreported and the literature is disparate, it is possible that Japanese clinicians publish case report more often than in other countries.

The quantitative analysis of 55 cases reflected that OAMs occur mostly in the older age group with high prevalence in the fifth to seventh decades of life and a mean age of 59.6 years. The literature review illustrated a similar pattern [5, 7, 52, 58, 59]. This review revealed a mean duration of 6.2 months until diagnosis, which could be attributed to this tumor's asymptomatic growth and benign appearance. In the present study, male predominance was observed (M:F, 1.29:1), which is concurrent with several studies [3, 4, 13, 21, 42, 60] while some studies showed female predominance [61–63] or no sex predilection [64]. Regarding location, the maxilla was more commonly involved than the mandible (ratio, 2.8:1) which is in agreement with the literature. We observed the palate as the most frequently affected site followed by maxillary gingiva and mandibular gingiva. It is worth mentioning that the development and anatomically close association of the palate with the nasal cavity, which marks the common site for head and neck melanomas, may partly explain this finding [4]. The extensive literature review revealed maxillary gingiva as the most common site of occurrence followed by palate and mandibular gingiva [4, 13, 21, 25, 65]. Cases have also been reported on the tongue, lip, and buccal mucosa. Clinically, OAMs presented as an asymptomatic, ill-defined, ulcerated or pinkish-red color, sessile, or pedunculated nodular mass. Bleeding, bone erosion, and tooth mobility were observed, with pain typically present in advanced cases. A small amount or few flecks of melanin may be detected on close inspection in few cases. These findings are in accordance with previous studies [7, 24, 66–68]. The absence of clinically significant melanin pigmentation makes OAM’s difficult to diagnose, and the differential diagnosis ranged from reactive, inflammatory, non-neoplastic to neoplastic lesions. The present review noted that malignancy was described as the first clinical impression of this tumor. This could be due to the lower evolution time until diagnosis and associated bone destruction seen on the radiograph in most of the cases.

Microscopically, OAM’s show a diverse cell morphology which includes epithelioid, spindle, round, round to spindle, fusiform, plasmacytoid, or undifferentiated small blue round cells. The size of the cell ranges from small to large with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, with or without prominent nucleoli. Loss of epithelial stratification (due to ulceration and necrosis), mitoses, lymphovascular and perineural invasion are the other features [2]. OAM exhibits a vertical growth pattern which rapidly forms invasive phenotype involving adjoining structures, while association of radial growth with melanizarion has also been suggested [51]. These features may explain the biological aggressiveness of the tumor [4, 5, 24]. The present study paralleled the literature review in which the spindle and epithelioid cell morphology were the most common and undifferentiated morphology was the least common cell type in OAM, however, few studies have shown undifferentiated and epithelioid cell morphology more prominent [7, 24]. We also, observed that out of 55 cases of OAM’s, only 14 cases reported the presence/absence of melanin in the tumor cells. Hence reporting of pigmentation presence/absence is vital.

OAMs should be differentiated through immunohistochemistry from other histologically overlapping lesions like poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, small blue cell tumors (rhabdomyosarcoma and olfactory neuroblastoma), high-grade carcinomas, neuroendocrine carcinomas, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor because of varied cell morphology and absence of melanin pigment histologically. Immunohistochemistry with HMB-45 and S-100 is more sensitive in differentiating this tumor from the other neoplasms [69, 70]. It is worthwhile to mention that 8 cases of OAMs showed 100% sensitivity to SOX10 markers, which requires further speculation [7]. In this review, quantitative synthesis was carried out with only cases diagnosed with immunohistochemistry to decrease the risk of misdiagnosis; however, the high variability in the immunohistochemical panels among the reports is still considered a potential limitation.

In the present review, 41.8% of patients exhibited lymph node involvement on clinical examination and 29.1% presented distant metastasis, while Soares et al. [7] has reported a higher incidence of 55% in both. The distant metastasis is seen mainly in the lungs, followed by liver, heart, bone, other systemic and visceral sites. The early identification of cervical lymph node metastasis could help patients with a high risk of distant metastasis to avail of early treatment, resulting in a better prognosis and outcome. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has proposed the TNM staging of mucosal melanomas based on tumor thickness, presence of ulceration, involvement of lymph nodes, and distant metastasis. Stage I and stage II include tumor thickness and presence of ulceration, stage III and stage IV are based on the involvement of lymph node and distant metastasis respectively (A, B). In the present review, with reference to available data, 4 cases were classified as stage I and stage II while stage III and stage IV showed 2 cases and 14 cases respectively. For the remaining 35 cases, the data was incomplete for TNM staging [2, 71]. Earlier studies were based on the 7th edition of AJCC TNM staging for assessment of OAM [4, 6, 7].

The current data showed surgery as the main therapeutic approach, alone or in combination with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, in agreement with the literature. Local tumor excision with surrounding healthy tissue and radical bone resection in cases where tumor-free margins are difficult to obtain is performed [6, 30, 72]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy is not effective when used in isolation. MMs are radio-resistant [73, 74] and irradiation is occasionally used in the elderly or medically compromised patients and post-surgically, when surgical margins cannot be obtained, to increase local control and reduce metastasis but not necessarily enhance survival [2, 72]. However, Tanaka et al. [24] reported a higher success rate with radiotherapy than surgery for OMMs. Chemotherapy is reserved for preoperative use to reduce the size of the tumor and for metastatic patients. Systemic immunotherapy has also been used, as adjuvant therapy, in cases involving widespread metastasis. In the future, detection of genetic alteration and developing molecular targeted therapy may be more effective and improve survival rates [6].

In the current review, 27 patients with reported follow-up, 25 died due to the tumor within 1–49 months after initial diagnosis. We observed, overall 3-years survival rate of patients was 18.75% and the 5-years survival rate was 6.25%; whereas Soraes et al. [7] noted a 1-year survival rate in 20% cases, and Nandapalan et al. [75] reported 20% survival at 3 years in OAM. Literature review shows a high mortality rate in OAM, 5-year survival in 5% cases, compared to pigmented oral mucosal and cutaneous melanomas, 58% survival at 3 years [30, 34, 35, 76]. We also observed recurrence in 9.1% cases of OAM, while the data was unavailable in 78.2% cases, at a mean interval of 3–16 months.

To identify the significant prognostic markers affecting patient survival, the clinicopathological variables in the present review were subjected to statistical analysis. de Paulo et al. [6] in his study could not find any significant prognostic factor for OAM. We observed patients older than 68 years demonstrated a lower survival rate. The higher death rate in elderly patients could be attributed to the tumor specifically or due to treatment complications, underlying systemic diseases or other causes. In addition, cases involving the mandibular gingiva showed lower survival rates, indicating that the tumor location also plays a vital role in the survival analysis. Histopathologically, we observed that OAMs having round cells had a lower survival rate, while Soares et al. [7] in their study on OMM suggested poor prognosis in tumors with epithelioid cell morphology. The treatment modality which consisted of an amalgamation of surgery, CT, and RT, seen in a single case of our study, showed a significantly lower survival rate. Late diagnosis, surgically challenging site (soft palate), high proliferative index (> 70%), lymph node involvement, or delayed treatment could partly explain the poor prognosis in this case. The lack of significance of survival rate with respect to other clinical features is due to the small number of cases investigated in this review. We could not identify independent prognostic factors by including the statistically significant parameters in the univariate analysis due to the low sample size. The nonresponse of several authors made it difficult to assess the reasons for incomplete information or missing data. This Insufficient source of information from the retrieved data is a reason for methodological limitation to our study. Given the limitations of this systematic review that retrieved clinicopathological data, it is important to highlight that the results obtained in our study need to be further validated.

To conclude, the OAM is a rare neoplasm with a poor prognosis, presenting a 6.25% possibility of survival after 5 years. Patients older than 68 years, lesions in the mandibular gingiva, round cells, and surgical excision along with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, presented the worst prognosis. However, they did not represent independent prognostic determinants for these patients. Further, published reports with complete data are required to uncover the prognostic factors and describe the distinct biological behavior of OAMs.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Dr. SB, Dr. SSD, Dr. VM, Dr. AA and Dr. RSD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. SB and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No support or source of funding was obtained.

Data Availability

Search strategy for Embase, Scopus, Pubmed.

Code Availability

R version 3.3.1 (R foundation for Statistical Computing).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest/The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical Approval

This is an observational study. The Ethics Committee of Nair Hospital Dental College (IEC-NHDC) has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shivani P. Bansal, Email: bshivani2000@gmail.com

Sonal Sunil Dhanawade, Email: sonaldhanawade@rediffmail.com.

Ankita Satish Arvandekar, Email: aankita.410@gmail.com.

Vini Mehta, Email: vinip.mehta@gmail.com.

Rajiv S. Desai, Email: nansrd@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Carvajal RD, Spencer SA, Lydiatt W. Mucosal melanoma: a clinically and biologically unique disease entity. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2012;10(3):345–356. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams MD. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of head and neck tumours: mucosal melanomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(1):110–7. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0789-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, Firoz B, Meehan SA. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39(1):33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Notani K, Shindoh M, Yamazaki Y, Nakamura H, Watanabe M, Kogoh T, et al. Amelanotic malignant melanomas of the oral mucosa. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40(3):195–200. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adisa AO, Olawole WO, Sigbeku OF. Oral amelanotic melanoma. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2012;10(1):6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Paulo LFB, Servato JPS, Rosa RR, Oliveira MTF, de Faria PR, da Silva SJ, et al. Primary amelanotic mucosal melanoma of the oronasal region: report of two new cases and literature review. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;19(4):333–339. doi: 10.1007/s10006-015-0501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares CD, Carlos R, de Andrade BAB, Cunha JLS, Agostini M, Romañach MJ, et al. Oral amelanotic melanomas: clinicopathologic features of 8 cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29(3):263–272. doi: 10.1177/1066896920946435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balk EM, Chung M, Hadar N, Patel K, Yu WW, Trikalinos TA, Chang L, et al. Accuracy of data extraction of non-english language trials with Google translate [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012 Apr. Introduction. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK95233/. [PubMed]

- 10.Takahashi M, Seiji M. Malignant melanoma in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1974;4(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuhashi T, Kuno H, Teramoto M, Kurauchi J, Kurauchi T, Fukaya M, et al. A case of amelanotic melanoma originating in the area of mandibule. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1979;25(6):1509–1513. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.25.1509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usui M, Shirasuna K, Morimoto T, Watatani K, Hayashido Y, Nishimura K, et al. Malignant melanoma in the upper alveolus: report of a case. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;31(5):1233–1240. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.31.1233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu L, Abdul A, Takahashi T, Kojima A, Himiya T, Kusama K, et al. Amelanotic melanoma of the oral cavity. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1993;35(2):124–129. doi: 10.2334/josnusd1959.35.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohshima K, Ohtawa A, Yoshiga K, Takada K, Ogawa I, Takata T. A case of amelanotic malignant melanoma in the maxilla. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;40(9):1006–1008. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.40.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tani R, Okamoto T, Sakamoto A, Yabumoto M, Toratani S, Takada K. A case of an amelanotic malignant melanoma successfully treated with LAK therapy. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;40(7):825–827. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.40.825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimazu K, Mohri M, Nishio M, Kamata M, Morimoto I. Amelanotic malignant melanoma in the palatal mucosa. Jibi inkōka rinshō. 1997;90(3):331–338. doi: 10.5631/jibirin.90.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibuya Y, Yoshikawa T, Umeda M, Ri S, Teranobu O, Shimada K. A case of amelanotic malignant melanoma of the maxillary gingiva. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;44(10):814–816. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.44.814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimijima Y, Mimura M, Tanaka N, Kimijima S, Noguchi I, Amagasa T. A difficult-to-diagnose case of amelanotic malignant melanoma in the anterior alveolar of the maxilla. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;45(11):703–705. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.45.703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohno J, Fujita S, Tojo T, Yamaguchi A, Nishida M, Iizuka T. A case of primary achromatic malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa where continuous intraarterial injection therapy of interferon-β was temporarily effective. J Jpn Soci Oral Tumors. 2000;12(4):327–331. doi: 10.5843/jsot.12.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuwazawa T, Okamoto T, Yamamura T, Ogiuchi Y, Uchiyama H, Ogiuchi H. A case of the multiple primary cancer involving maxillary amelanotic malignant melanoma and gastric cancer. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;47(4):243–246. doi: 10.5794/jjoms.47.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao SY, Yang JC, Li WY, Chang RC. Maxillary amelanotic melanoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(6):700–703. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.23409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ducic Y, Pulsipher DA. Amelanotic melanoma of the palate: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(5):580–583. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.22695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krenz RM, Matusik J, Csanaky G. Amelanotic oral malignant melanoma in a 16 year-old girl. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2004;9(5):183–186. doi: 10.1016/S1507-1367(04)71027-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka N, Mimura M, Kimijima Y, Amagasa T. Clinical investigation of amelanotic malignant melanoma in the oral region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(8):933–937. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cicconetti A, Guttadauro A, Riminucci M. Ulcerated pedunculated mass of the maxillary gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108(3):313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimal J, Kasturi DP, Sumanth KN, Ongole R, Shrestha A. Intra-oral amelanotic malignant melanoma: report of a case and review of literature. J Nepal Dent Assoc. 2009;10:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominiak M, Gerber H, Kubasiewicz-Ross P, Ziółkowski P, Łysenko L. Amelanotic malignant melanoma in the oral mucosa localization. Am J Case Rep. 2011;12:159–62. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.882099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawasaki G, Yanamoto S, Yoshitomi I, Mizuno A, Fujita S, Umeda M. Amelanotic melanoma of the mandible: a case report. Oral Sci Int. 2011;8(2):60–63. doi: 10.1016/S1348-8643(12)00002-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patil D, Gandhi A, Karjodkar FR, Deshpande MD, Desai SB. An amelanotic melanoma of the oral cavity—a rare entity; case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5(6):1314–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bansal S, Desai RS, Shirsat P. Amelanotic melanoma of the oral cavity: a case report and review of literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;3(3):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jou A, Miranda FV, Oliveira MG, Martins MD, Rados PV, Filho MS. Oral desmoplastic melanoma mimicking inflammatory hyperplasia. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e1163–e1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar V, Shukla M, Goud U, Ravi DK, Kumar M, Pandey M. Spindle cell amelanotic lesion of the tongue: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(Suppl 1):394–397. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venugopal M, Renuka I, Bala GS, Seshaiah N. Amelanotic melanoma of the tongue. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17(1):113–115. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.110699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandiar D, Basheer S, Shameena PM, Sudha S, Dhana LJ. Amelanotic melanoma masquerading as a granular cell lesion. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:924573. doi: 10.1155/2013/924573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saghravanian N, Pazouki M, Zamanzadeh M. Oral amelanotic melanoma of the maxilla. J Dent (Tehran) 2014;11(6):721–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vierne C, Hardy H, Guichard B, Barat M, Péron JM, Trost O. Mandibular metastasis of a cutaneous melanoma or metachronous amelanotic melanoma of the oral cavity? A case report and literature review. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2014;59(4):276–279. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakamoto Y, Yanamoto S, Matsushita Y, Yamada S-I, Takahashi H, Fujita S, et al. Simultaneous triple primary malignant melanomas occurring in the buccal mucosa, upper gingiva, and tongue: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015;27(4):540–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoms.2014.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohnishi Y, Watanabe M, Fujii T, Sunada N, Yoshimoto H, Kubo H, et al. A rare case of amelanotic malignant melanoma in the oral region: clinical investigation and immunohistochemical study. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3761–3764. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singhvi A, Joshi A. A case of amelanotic malignant melanoma of the maxillary sinus presented with intraoral extension. Malays J Med Sci. 2015;22(5):89–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta M, Bhola N, Jadhav A, Borle RM, Deshpande N, Fidvi M. Amelanotic malignant melanoma of maxilla: a rarity-case report. J Dent Med Sci. 2017;16(9):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deyhimi P, Razavi SM, Shahnaseri S, Khalesi S, Homayoni S, Tavakoli P. Rare and extensive malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: report of two cases. J Dent (Shiraz) 2017;18(3):227–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moshe M, Levi A, Ad-El D, Ben-Amitai D, Mimouni D, Didkovsky E, et al. Malignant melanoma clinically mimicking pyogenic granuloma: comparison of clinical evaluation and histopathology. Melanoma Res. 2018;28(4):363–367. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper H, Solway J, Wolf M, Miller R. Case report: a case of oral mucosal amelanotic melanoma in a 77-year-old immunocompromised male. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):8462. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimitrios M, Athanasios P, Eleni M, Antonios K, Dimitrios A, Lefteris A. Oral amelanotic melanoma: a silent killer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2019;48:5–83. doi: 10.1111/jop.12796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nwoga MC, Effiom OA, Adeyemi BF, Soyele OO, Okwuosa CU. Oral mucosal melanoma in four Nigerian teaching hospitals. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22(12):1752–1757. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_176_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sungkhao W, Klanrit P, Jinaporntham S, Subarnbhesaj A. Primary amelanotic melanoma of the maxillary gingiva: a case report. J Dent Indones. 2019 doi: 10.14693/jdi.v26i3.1000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raha H, Changizi M, Esnaashari N, Ghapanchi J, Sadeghzadeh A. Oral amelanotic malignant melanoma: a review and a case report. J Case Rep Stud. 2019;7(3):303–307. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim BJ, Kim HS, Chang YJ, Kwon KH, Cho SJ. Primary amelanotic melanoma of the mandibular gingiva. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21(2):132–136. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koca RB, Unsal G, Soluk Tekkeşin M, Kasnak G, Orhan K, Özcan İ, et al. A review with an additional case: amelanotic malignant melanoma at mandibular gingiva. Int Cancer Conf J. 2020;9(4):175–181. doi: 10.1007/s13691-020-00425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Limongelli L, Cascardi E, Capodiferro S, Favia G, Corsalini M, Tempesta A, et al. Multifocal amelanotic melanoma of the hard palate: a challenging case. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(6):424. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10060424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gong HZ, Zheng HY, Li J. Amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2019;29(3):221–230. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rapini RP, Golitz LE, Greer ROJ, Krekorian EA, Poulson T. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity. A review of 177 cases. Cancer. 1985;55(7):1543–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850401)55:7<1543::AID-CNCR2820550722>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holmstrom M, Lund VJ. Malignant melanomas of the nasal cavity after occupational exposure to formaldehyde. Br J Ind Med. 1991;48(1):9–11. doi: 10.1136/oem.48.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takagi M, Ishikawa G, Mori W. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity in Japan; with special reference to mucosal melanomas. Cancer. 1974;34(2):359–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197408)34:2<358::AID-CNCR2820340221>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steidler NE, Reade PC, Radden BG. Malignant melanoma of the oral mucosa. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42(5):333–336. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altieri L, Wong MK, Peng DH, Cockburn M. Mucosal melanomas in the racially diverse population of California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, Martin HJ, Roche LM, Chen VW. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer. 2005;103(5):1000–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma. A summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. Cancer. 1998;83(8):1664–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1664::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hicks MJ, Flaitz CM. Oral mucosal melanoma: epidemiology and pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(2):152–169. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(99)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moreau JF, Weissfeld JL, Ferris LK. Characteristics and survival of patients with invasive amelanotic melanoma in the USA. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(5):408–413. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32836410fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McClain SE, Mayo KB, Shada AL, Smolkin ME, Patterson JW, Slingluff CL., Jr Amelanotic melanomas presenting as red skin lesions: a diagnostic challenge with potentially lethal consequences. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(4):420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas NE, Kricker A, Waxweiler WT, Dillon PM, Busman KJ, From L, Environment, and Melanoma (GEM) Study Group et al. Comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival of histopathologically amelanotic and pigmented melanomas: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(12):1306–314. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huvos AG, Shah JP, Goldsmith HS. A clinicopathologic study of amelanotic melanoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;135(6):917–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giuliano AE, Cochran AJ, Morton DL. Melanoma from unknown primary site and amelanotic melanoma. Semin Oncol. 1982;9(4):442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prasad ML, Patel SG, Huvos AG, Shah JP, Busam KJ. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: a proposal for microstaging localized, Stage I (lymph node-negative) tumors. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1657–1664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gorsky M, Epstein JB. Melanoma arising from the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86(6):715–719. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaudhry AP, Hampel A, Gorlin PJ. Primary malignant melanoma of the oral cavity. A review of 105 cases. Cancer. 1958;11(5):923–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195809/10)11:5<923::AID-CNCR2820110507>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ulusal BG, Karatas O, Yildiz AC, Oztan Y. Primary malignant melanoma of the maxillary gingiva. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(3):304–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benevenuto de Andrade BA, Piña AR, León JE, Paes de Almeida O, Altemani A. Primary nasal mucosal melanoma in Brazil: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012;16(5):344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mendenhall WM, Amdur RJ, Hinerman RW, Werning JW, Villaret DB, Mendenhall NP. Head and neck mucosal melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28(6):626–630. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000170805.14058.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greshenwald JE, Scolves RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997;80(8):1373–1386. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1373::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wagner M, Morris CG, Werning JW, Mendenhall WM. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318134ee88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krengli M, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Kaanders JH, Masini L, Beldì D, Orecchia R. What is the role of radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nandapalan V, Roland NJ, Helliwell TR, Williams EM, Hamilton JW, Jones AS. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1998;23:107–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rogers RS, 3rd, Gibson LE. Mucosal, genital, and unusual clinical variants of melanoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(4):362–366. doi: 10.4065/72.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Search strategy for Embase, Scopus, Pubmed.

R version 3.3.1 (R foundation for Statistical Computing).