Abstract

There is limited literature detailing the histology of pharyngeal papillomas. Herein, we report our experience with papillomas occurring in the oro-and nasopharynx that have both squamous and respiratory features akin to the sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma. We retrospectively reviewed pharyngeal papillomas that were composed of both squamous and respiratory epithelium received at our institution between 2010 and 2020. Cases of sinonasal papillomas directly extending into the pharynx were excluded. Immunohistochemistry for p16 as well as RNA in situ hybridization to evaluate for 6 low-risk and 18 high-risk HPV genotypes were performed on all cases. Thirteen cases were included. Mean age was 61 with 12 males and 1 female. While often incidentally found, presenting symptoms included globus sensation, hemoptysis, and hoarseness of voice. Histologically, all tumors consisted of squamous and respiratory epithelium with neutrophilic infiltrates arranged in an exophytic/papillary architecture that was reminiscent of the exophytic type of Schneiderian papilloma. Immunohistochemistry for p16 was negative in all papillomas. 85% were positive for low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) subtypes and all were negative for high-risk HPV subtypes. A well-differentiated, invasive squamous cell carcinoma was associated with two of the cases. Papillomas with squamous and respiratory features similar to the sinonasal exophytic Schneiderian papilloma can arise in the oro- and nasopharynx and like their sinonasal counterparts show an association with HPV. While many in this series were benign, they can be harbingers for invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Keywords: Papilloma, Sinonasal tract, Pharynx, Papillomavirus infections, Squamous cell carcinoma, Head and neck neoplasms

Introduction

Schneiderian papillomas, also known as sinonasal papillomas, are benign neoplasms that are derived from the Schneiderian mucosa [1]. The Schneiderian mucosa is an ectodermally derived ciliated respiratory mucosa lining the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses [1]. In the sinonasal region these papillomas have been divided into three subtypes: inverted, exophytic and oncocytic [2]. There has been an ongoing debate since the 1800s, with regards to their nosology, etiology, and terminology; this history and the characteristics of each subtype are reviewed by Dr. Justin Bishop in his 2017 update on sinonasal papillomas [3].

Rarely, lesions histologically akin to Schneiderian papillomas have been reported outside the sinonasal tract. Their occurrence in the nasopharynx, oropharynx, oral cavity, hypopharynx, middle ear, mastoid, and lacrimal sac has been described in a handful of case reports and case series [4–20]. In this case series we report our experience with papillomas arising in the oro- and nasopharynx that have squamous and respiratory features that are similar to their sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma counterpart.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 17-1573). We performed a natural language search from 2010 to 2020 to identify referral and in-house cases of papillomas arising in the pharynx. We excluded cases that represented sinonasal papillomas directly extending into the pharynx. Papillomas had to be composed of both squamous and respiratory epithelium to be included in this series.

Immunohistochemistry for p16 (E6H4, predilute, Ventana) was performed on 5-µm thick formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue using fully automated systems on the BenchMark ULTRA instrument (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ). Positive expression of p16 was defined as strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in 70% or more of tumor cells. HPV testing was performed by RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) using the RNAscope method (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA). 4-µm thick formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue were evaluated with the HPV-LR6 Probe which detects 6 low-risk HPV genotypes (6, 11, 40, 42, 43 & 45) and the HPV-HR18 Probe which detects 18 high-risk HPV genotypes (16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73 & 82) (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA). Positive cells are characterized by dot-like cytoplasmic and/or nuclear brown precipitates.

Clinicopathologic characteristics including patients’ age, sex, presenting symptoms, size of tumor, location of tumor, number of tumors, histologic characteristics, history of papillomas in same site or at other sites, smoking status, treatment, and follow-up were recorded when available.

Results

The clinical and pathologic features are summarized in Table 1. A total of 13 cases were identified, 12 in-house and 1 referral case. There were 12 males and 1 female with ages ranging from 32 to 80 years (mean: 61 years). Smoking history was available for 12 patients, and all were former or current nicotine smokers. Presenting symptoms included (number of cases): globus sensation/mass (4, 31%), asymptomatic (4, 31%), hemoptysis (2, 15%), hoarseness (1, 8%), nasal congestion (1, 8%), unknown (1). Five cases (38%) were in the nasopharynx, most commonly the nasal aspect of the soft palate, with 2 (15%) cases involving the eustachian tube. Eight cases (62%) were in the oropharynx, most commonly the uvula. One patient had a history of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis with papillomas involving the trachea and subglottis and another had a concurrent exophytic schneiderian papilloma in the septum that was separate from his posterior soft palate/uvula oropharyngeal papilloma. Ten cases had tumor size available; sizes ranged from 1.0 to 6.0 cm (median: 1.5 cm & mean: 1.9 cm). Six cases (46%) were described as single discrete lesions, while 5 cases (38%) represented sampling of two or more lesions. The number of discrete lesions was not available in 2 cases.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic features of pharyngeal papillomas with squamous and respiratory features

| Case | Location | Sex | Age (years) | Size (cm) | Histology | LR HPV | Treatment | History | F/U (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nasopharynx | M | 61 | 1.0 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with focal ciliated respiratory cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision, with KTP laser ablation | Prior papilloma in naso/oropharynx | Alive, NED (8) |

| 2 | Oropharynx | M | 80 | 1.5 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates including abscesses | Neg | Excision | No relevant |

Alive, NED (7.4) |

| 3 | Oropharynx | M | 60 | 1.0 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Neg | Excision | Tracheal invasive squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemo/radiation 2 years ago | Deceased unrelated to papilloma, (0.6) |

| 4 | Nasopharynx | M | 53 | 2.4 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates including abscesses; parakeratosis present | Pos | Excision | History of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis involving trachea and larynx | Unknown |

| 5 | Nasopharynx | M | 78 | N/A | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with focal ciliated respiratory cells and neutrophilic infiltrates; parakeratosis present | Pos | Excision | Prior papilloma in naso/oropharynx | Alive, NED (2.9) |

| 6 | Oropharynx | M | 57 | 1.0 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision | No relevant | Alive, NED (3.1) |

| 7 | Oropharynx | M | 62 | 1.5 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision | No relevant | Alive, NED (3.3) |

| 8 | Nasopharynx | M | 70 | N/A | Fragments of exophytic papilloma with stratified squamous epithelium with focal ciliated respiratory cells and neutrophilic infiltrates; parakeratosis present. Admixed fragments of well-differentatied, keratinizing invasive squamous cell carcinoma with a pushing growth pattern and loss of neutrophils and perineural invasion | Pos | Excision followed by radiation | No relevant | Alive, NED (1.7) |

| 9 | Oropharynx | M | 68 | N/A | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision | No relevant | Unknown |

| 10 | Oropharynx | M | 32 | 1.5 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium, ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates with focal parakeratosis | Pos | Excision | Concurrent exophytic sinonasal papilloma | Alive, NED (0.5) |

| 11 | Nasopharynx | M | 65 | 1.6 |

Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium, with focal ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates Admixed fragments of well-differentatied, keratinizing invasive squamous cell carcinoma with a pushing growth pattern and loss of neutrophils with focal parakeratosis |

Pos | Excision, followed by radiation | No relevant | Alive, NED (1.9) |

| 12 | Oropharynx | F | 52 | 1.5 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with focal ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision | No relevent | Alive, NED (0.6) |

| 13 | Oropharynx | M | 60 | 6 | Exophytic, stratified squamous epithelium with ciliated respiratory cells, mucous cells and neutrophilic infiltrates | Pos | Excision | No relevant | Alive, NED (0.3) |

NED no evidence of disease, LR HPV low-risk human papillomavirus, KTP Potassium Titanyl Phosphate, F/U follow-up; N/A not applicable, Pos positive, Neg negative

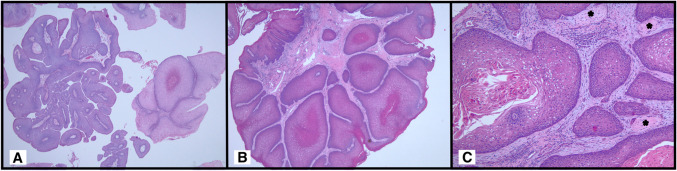

Histologically, all thirteen cases demonstrated a predominantly exophytic architecture i.e. broad based growth with rounded projections covered by epithelium (Fig. 1A). Focal papillary growth i.e. thin, filiform projections with fibrovascular cores covered by epithelium were noted in 11 of 13 cases (85%) accounting for 5 to 30% of the growth pattern. All cases were lined by multilayered stratified squamous epithelium which transitions to ciliated pseudostratified columnar respiratory epithelium (Fig. 1B). Mucous cells were identified in 10 cases (77%) (Fig. 1C). Neutrophilic infiltrates including neutrophilic microabscesses were a consistent finding associated with the epithelium in all cases (Fig. 1D). Parakeratosis was noted in 5 cases (38%). Two cases, including one with parakeratosis, demonstrated a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 2A). The foci of carcinoma demonstrated a morphologic shift in that the squamous epithelium in these areas became thicker with a glassier, keratinized appearance as well as loss of neutrophils. The carcinoma had a broad based, pushing pattern of invasion (Fig. 2B). The carcinoma was associated with perineural invasion in one case (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Papilloma with squamous and respiratory features demonstrating an exophytic architecture with focal papillary growth (arrow) (A). The multilayered stratified squamous epithelium transitions to ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium (B). Mucous cells are a prominent feature in this case (C). Neutrophilic infiltrates were a consistent finding (D)

Fig. 2.

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma arising in association with the papilloma with squamous and respiratory features. The papilloma fragments on the left of image have both multilayered squamous epithelium admixed with ciliated respiratory epithelium, the well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma fragments on the right of image have thicker epithelium with a glassier, keratinized appearance (A). In this intact fragment invasion by the well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is apparent as broad pushing pattern (B), perineural invasion was also identified in this case (asterisk) (C)

Immunohistochemistry for p16 was considered negative in all cases, with staining ranging from 5 to 30% of tumor cells in a patchy distribution (Fig. 3A). In-situ hybridization for low-risk HPV subtypes was positive in 11 of 13 cases (85%) (Fig. 3B–D) including the two papillomas with associated squamous cell carcinomas. In 6 of the 11 low-risk HPV positive cases (55%), a positive signal was seen in both respiratory and squamous cells (Fig. 3D). In 3 of the 11 cases (27%) the respiratory component was cut-through and not present for evaluation on the ISH slide. And in 2 cases (18%) no convincing signal was found in the respiratory areas, though these areas were quite admixed with the squamous component making their distinction challenging on the ISH slide. All cases were negative for high-risk HPV subtypes.

Fig. 3.

p16 immunohistochemistry demonstrated patchy expression in both the papilloma and well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and was considered to be negative in both components (A). Refer to Fig. 2A for the corresponding hematoxylin and eosin-stained section. Chromogenic in-situ hybridization for low-risk HPV subtypes is positive in both the carcinoma (B) and the papilloma component (C). There is dot-like positivity in the ciliated columnar cells as well (arrow) (D). Inset: Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section from the corresponding area

All cases were initially treated by excision. In the two cases with associated well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, one patient received post-operative radiation while the other received both cisplatin-based chemotherapy and radiation. Follow-up was available for 11 patients (average of 2.8 years), 10 (77%) were alive and one patient was deceased from advanced staged laryngeal cancer which was not directly related to his papilloma. Two patients (15%) reportedly had a prior history of papillomas in the nasopharynx with their current cases, included in this study, representing recurrences of their prior disease. Of these two patients, one has been free of further recurrent disease over subsequent 8 years of follow-up. However, the other patient has had an ongoing history of nasopharyngeal papillomas since 1999 with multiple recurrences in 2000, 2001, 2005 and then 2017. Since the 2017 recurrence (specimen included in study) this patient has been free of further disease.

Discussion

Schneiderian papillomas can rarely occur outside the sinonasal tract and have been reported in the nasopharynx, oropharynx, oral cavity, hypopharynx, middle ear, mastoid, and lacrimal sac [4–20]. The largest series of Schneiderian-like papillomas of the pharynx was reported by Sulica et al. in 1999, in which they presented 16 cases that were identical to inverted papillomas [4]. Sulica et al. discussed the embryology of the upper aerodigestive tract and suggested that there might be an inclusion of Schneiderian mucosa in sites outside its normal range [4]. Based on their histologic description and the figures they provided, all the papillomas in their paper showed inverted growth with downward invagination of the proliferating epithelium, consistent with an inverted subtype [4]. There are also rare reports of the oncocytic subtype of Schneiderian papillomas occurring in the nasopharynx [17, 19]. However, in our series the papillomas that had squamous and respiratory features all demonstrated an exophytic or papillary growth pattern without significant downward invagination that was akin to the exophytic subtype of sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma.

Investigations surrounding the association of HPV and Schneiderian papillomas began in the 1980s [21]. Although HPV detection methods and rates are highly variable, it appears that there is a more consistent association with the exophytic subtype and less well-established prevalence in the inverted subtype [22–28]. HPV6 and 11 are the most consistently detected genotypes [21–23]. While most studies have not detected HPV in the oncocytic subtype, a recent study showed the presence of HPV by polymerase chain reaction in four of thirty-six oncocytic papillomas [23–26, 29]. Similar to studies in the sinonasal tract, our papillomas with squamous and respiratory features also demonstrated a consistent association with low-risk HPV as it was detected in 85% of cases.

While the risk of malignancy associated with exophytic Schneiderian papillomas in the sinonasal tract is quite rare, our series had two cases that had an associated well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The well-differentiated carcinoma arising in this setting had a broad based, pushing pattern of invasion and was characterized by thicker epithelium with a glassier more keratinized appearance. We also noted a loss of the neutrophils in the areas of carcinoma. This loss of transmigrating neutrophils has been previously documented as a feature that can be seen in Schneiderian papillomas transitioning to carcinomas [30].

Low-risk human papillomavirus subtypes are not typically associated with malignant transformation, however, there are rare reports of low-risk subtypes being detected in cervical and anal carcinomas [31]. The low-risk HPV signal was maintained in both the papilloma and areas of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma in both cases which we speculate provides evidence that the squamous cell carcinoma arose out of the papilloma. However, this finding does not necessarily mean that the LR-HPV has a causative role in the malignant progression of the papilloma; but may simply be a marker of its origin from the papilloma.

It is plausible that these papillomas with squamous and respiratory features arising in the oro- and nasopharynx are equivalent to traditional squamous papilloma that just happens to have integration of the native respiratory mucosa. However, a low-risk HPV ISH signal was detected in the respiratory cells in 6 of the 11 positive cases (55%). While not conclusive, this suggests that the respiratory cells are likely lesional rather than entrapped normal epithelium. However, direct comparison to the native mucosa would need to be performed to further establish that conclusion which was not present in all cases.

Furthermore, the separation from the traditional squamous papilloma is not as clear cut as both have overlapping histologic features and an association with HPV. Ultimately, it is the recognition of the respiratory epithelial component that seems to be the distinguishing histologic feature. The respiratory elements can range from being quite focal to overt with well-developed mucinous cells. There are also some additional subtle differences to the traditional squamous papilloma. Firstly, those with glandular elements tend to be more exophytic rather than papillary. The delicate glycogenated appearance that is seen in the traditional squamous papillomas is also less apparent and the epithelium appears more densely squamous. In addition, all the cases in our series showed transmigrating mucosal neutrophilic infiltrates. In our experience, traditional squamous papillomas do not tend to have a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate unless they have been traumatized or there is concurrent candidal colonization. In essence these papillomas with squamous and respiratory features seem to be histologically closer to their sinonasal Schneiderian counterparts rather than the traditional squamous papillomas. Additionally, their risk of recurrence and the risk of malignancy, albeit low but not insignificant, is also more in-line with sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma than the traditional squamous papilloma.

It is interesting that one of our patients had a history of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) with papillomas in the trachea and subglottis. The possibility that the papilloma in the nasopharynx is a manifestation of his RRP cannot be excluded. While RRP is histologically considered a type of squamous papilloma, it has been reported that these papillomas can also have respiratory features similar to the papillomas in this series [32]. Additionally, one of our patients also had an exophytic Schneiderian papilloma on the septum which was separate from their oropharyngeal papilloma. This can suggests that patients with HPV related diseases in other sites can also develop papillomas in their pharynx that are also HPV-related.

The best diagnostic term for these pharyngeal papillomas that have squamous and respiratory features: Schneiderian-like, Schneiderian-type or flat out Schneiderian papilloma is debatable; particularly, as the use of Schneiderian papilloma has been superseded by sinonasal papilloma [2]. For the purposes of this article, we decided to use a descriptive terminology of papilloma with squamous and respiratory features. But recognize that these lesions seem more akin to their sinonasal Schneiderian papilloma counterparts rather than the traditional squamous papilloma. As additional cases are recognized, our understanding and terminology will evolve for these pharyngeal papillomas.

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Emad Ababneh and Akeesha Shah. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Akeesha Shah, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability

Data is available upon request from Authors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of Cleveland Clinic Foundation approved this study (IRB number: 17-1573).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Perez-Ordonez B. Special tumours of the head and neck. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2003;9:366–383. doi: 10.1016/S0968-6053(03)00068-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop JA. OSPs and ESPs and ISPs, Oh My! An update on Sinonasal (Schneiderian) Papillomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(3):269–277. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulica RL, Wenig BM, Debo RF, Sessions RB. Schneiderian papillomas of the pharynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108(4):392–397. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nosanckuk JS. Oropharyngeal inverting papilloma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;100:71–72. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780040075018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fechner RE, Sessions RB. Inverted papilloma of the lacrimal sac, the paranasal sinuses and the cervical region. Cancer. 1977;40:2303–2308. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2303::AID-CNCR2820400543>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff AP, Ossoff RH, Clemis JD. Four unusual neoplasms of the nasopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88:753–759. doi: 10.1177/019459988008800623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astor FC, Donegan JO, Gluckman JL. Unusual anatomic presentations of inverting papilloma. Head Neck Surg. 1985;7:243–245. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gluckman JL, Astor F, Donegan JO, Welsh R, Wessler T. Spontaneous malignant transformation of multiple nasopharyngeal papilloma? A report of two cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94(2):260–265. doi: 10.1177/019459988609400226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone DM, Berktold RE, Ranganathan C, Wiet RJ. Inverting papilloma of the middle ear and mastoid. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:416–418. doi: 10.1177/019459988709700416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Reilly BJ, Zuk R. Transitional type papilloma of the nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103(5):528–530. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100156798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampal S, Hawthorne M. Hypopharyngeal inverted papilloma. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:432–434. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100158657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boesen PV, Laszewski MJ, Robinson RA, Dawson DE. Squamous cell carcinoma in an inverted papilloma of the buccal mucosa. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:748–750. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaddour HS, Woodhead CJ. Transitional papilloma of the middle ear. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:628–629. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100120377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts WH, Dinges DL, Hanly MG. Inverted papilloma of the middle ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:890–892. doi: 10.1177/000348949310201113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenig BM. Schneiderian-type mucosal papillomas of the middle ear and mastoid. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:226–233. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochhar L, Choudhary S. Cylindrical papilloma of nasopharynx (a case report) Med J Armed Forces India. 1997;53(3):233–234. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(17)30726-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Low WK, Toh ST, Lim CM, Ramesh G. Schneiderian papilloma of the nasopharynx. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002;81(5):336–338. doi: 10.1177/014556130208100512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chrysovergis A, Paschalidis J, Michaels L, Bibas A. Nasopharyngeal cylindrical cell papilloma. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125(1):86–88. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110002094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishikawa M, Tsunoda A, Tanaka Y, Kishimoto S. Large nasopharyngeal inverted papilloma presenting with rustling tinnitus. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35(3):402–404. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syrjanen S, Happonen RP, Virolainen E, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) structural antigens and DNA types in inverted papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987;104:334–341. doi: 10.3109/00016488709107337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syrjanen KJ. HPV infections in benign and malignant sinonasal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:174–181. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaffey MJ, Frierson HF, Weiss LM, et al. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in sinonasal Schneiderian papillomas. An in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:475–482. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judd R, Zaki SR, Coffield LM, et al. Sinonasal papillomas and HPV: HPV 11 detected in fungiform Schneiderian papillomas by in situ hybridization and PCR. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:550–556. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90231-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner JS, Sherris D, Kasperbauer J, et al. Relationship of HPV to Schneiderian papillomas. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:21–26. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchwald C, Franzmann MB, Jacobsen GK, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in sinonasal papillomas: a study of 78 cases using in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:66–71. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199501000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawson W, Schlecht NF, Brandwein-Gensler M. The role of the human papillomavirus in the pathogenesis of Schneiderian inverted papillomas: an analytic overview of the evidence. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah AA, Evans MF, Adamson CSC, et al. HPV DNA is associated with a subset of Schneiderian Papillomas but does not correlate with p16INK4a immunoreactivity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4(2):106–112. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Zhai C, Liu J, Wang J, Sun X, Hu L, Wang D. Low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in sinonasal inverted papilloma and oncocytic papilloma. Virchows Arch. 2020;476(4):577–583. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02717-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nudell J, Chiosea S, Thompson LDR. Carcinoma ex-Schneiderian papilloma (malignant transformation): a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 20 cases combined with a comprehensive review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:269–286. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egawa N, Doorbar J. The low-risk papillomaviruses. Virus Res. 2017;231:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fechner RE, Fitz-Hugh GS. Invasive tracheal papillomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4(1):79–86. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198004010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from Authors.