Abstract

Background

This study aims to provide 12-year nationwide epidemiology data to investigate the epidemiology and comorbidities of and therapeutic options for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) by analyzing the National Health Insurance Research Database.

Methods

6306 patients identified as having CFS during the 2000–2012 period and 6306 controls (with similar distributions of age and sex) were analyzed.

Result

The patients with CFS were predominantly female and aged 35–64 years in Taiwan and presented a higher proportion of depression, anxiety disorder, insomnia, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, renal disease, type 2 diabetes, gout, dyslipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren syndrome, and herpes zoster. The use of selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs), Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), benzodiazepine (BZD), Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), muscle relaxants, analgesic drugs, psychotherapies, and exercise therapies was prescribed significantly more frequently in the CFS cohort than in the control group.

Conclusion

This large national study shared the mainstream therapies of CFS in Taiwan, we noticed these treatments reported effective to relieve symptoms in previous studies. Furthermore, our findings indicate that clinicians should have a heightened awareness of the comorbidities of CFS, especially in psychiatric problems.

Keywords: Chronic fatigue syndrome, Epidemiology, Treatment, National health programs, Nationwide population-based study

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, is characterized by the experience of debilitating fatigue for more than 6 months that is not improved by rest [1]. The World Health Organization classifies CFS as a neurological illness, and over the last 30 years, numerous studies have identified and verified the diagnostic criteria for CFS, which are unexplained persistent or relapsing fatigue lasting at least 6 months with the addition of the concurrent presence of four or more of the following symptoms over a 6-month period: unusual postexertion fatigue, impaired memory or concentration, unrefreshing sleep, headache, muscle pain, joint pain, sore throat, and tender cervical nodes [2].

Several studies have indicated that the following multifactorial mechanisms contribute to the onset of CFS: Epstein–Barr virus, human herpes virus 6 [3], Helicobacter pylori,[4] Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection [5], immunoinflammatory pathways [6], neuroimmune dysfunctions [7], and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways, such as those induced by burn injury [8, 9]. It also shares some features of autoimmune disease. In addition, we previously reported that inflammatory bowel disease, herpes zoster and psoriasis are associated with an increased risk of subsequent CFS [10–12].

CFS considerably reduces patients’ quality of life and places a financial burden on the patients, their families, and health care systems [13]. The primary goals of management are to relieve symptoms and provide supportive health care to improve functional capacities. However, no pharmaceutical therapies have been licensed for CFS nor has any strong evidence been revealed on the efficacy of a single regimen. In the present study, we investigated the epidemiology and comorbidities of and therapeutic options for CFS by using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Our results can help physicians diagnose CFS early and manage the disorder effectively.

Methods

Data source

The data set used in this study was derived from the NHIRD, which contains details concerning the demographic characteristics, dates of admission and discharge, drug prescriptions, surgical procedures, and diagnostic codes for approximately 99% of Taiwan’s population of 23 million. The 2000 Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, which is a data subset of the NHIRD, includes all the original claims data and registration files for 1 million individuals randomly sampled from among the beneficiaries of the NHI program in 2000 in Taiwan. The diseases are defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

Sample participants

Cases of CFS were identified using two outpatient records or one admission record with a diagnosis of ICD-9-CM code 780.71. The date of the first diagnosis of CFS was the index date. For each CFS case, we used a frequency matching method to select a participant without CFS with the same sex, age, and index date as a control. Participants aged below 18 years or with missing information on sex were excluded.

Exposure assessment and comorbidities

For this study, we examined exposure to pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical treatments. In terms of exposure to pharmaceutical treatments, we included the following: selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code N06AB10, N06AB06, N06AB03, N06AB08 and N06AB05), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (ATC code N06AX21 and N06AX16), Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs) (ATC code N06AX05), Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (ATC code N06AA09 and N06CA01), benzodiazepine (BZD) (ATC code N03AE01, N05BA06, N05BA12, N05BA01, N05BA17, N05BA22, N05CD04, N05CD05, N05CD03, N05CD09, N05CD01 and N05CD08), Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) (ATC code N06AX12), Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs) (ATC code N06AX11), muscle relaxants (ATC code M03BX08), and analgesic drugs (including acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], pregabalin, and gabapentin) (ATC code M02AA, D11AX18, M01A, M01B, N03AX16, and N03AX12). With regard to nonpharmaceutical treatments, we included supportive individual psychotherapy, supportive group psychotherapy, intensive individual psychotherapy, intensive group psychotherapy, reeducative individual psychotherapy, reeducative group psychotherapy, behavior modification assessments, behavior modification planning, stretching exercise, therapeutic exercise, breathing exercises, reconditioning exercise, multiple physical examinations of sleep, brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness and a brainwave examination for sleep disorders. We made adjustments for the potentially confounding effects of other comorbidities, including depression(ICD-9-CM code 296.2, 296.3, 926.82, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, and 311), anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM code 300.0–300.3, 300.5–300.9, 309.2–309.4, 309.81, and 313.0), Insomnia (ICD-9-CM code 307.41, 307.42, 780.50, and 780.52), suicide (ICD-9-CM code E950-E959), crohn's disease (ICD-9-CM code 555), ulcerative colitis (ICD-9-CM code 555–556), renal disease (ICD-9-CM code 580–589), diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250 and A181), obesity (ICD-9-CM code 278), gout (ICD-9-CM code 274), dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), malignancy (ICD-9-CM code 140–208), HIV (ICD-9-CM code 042–044), rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 714), psoriasis (ICD-9-CM code 696.x), ankylosing spondylitis (ICD-9-CM code 720.0), lymphadenopathy (ICD-9-CM code 289.1–289.3, 686, and 785.6), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (ICD-9-CM code 245.2), Sjogren’s syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 710.2), irritable bowel syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 564.1), SLE (ICD-9-CM code 710.0), celiac disease (ICD-9-CM code 579.00, fibromyalgia (ICD-9-CM 729.1), and herpes zoster (ICD-9-CM code 053) anxiety disorders, insomnia, suicide, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and renal disease, prior to the index date. These were evaluated as part of the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of CFS and the controls were reported, including demographic characteristics, comorbid diseases, and treatments received after the index date. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables between the CFS cohort and the control cohort, as necessary. We used a logistic regression model to assess the CFS treatments the patients had received. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and then subsequently adjusted using covariates, which included age, sex, and comorbidities. Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4 for Windows; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Values were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

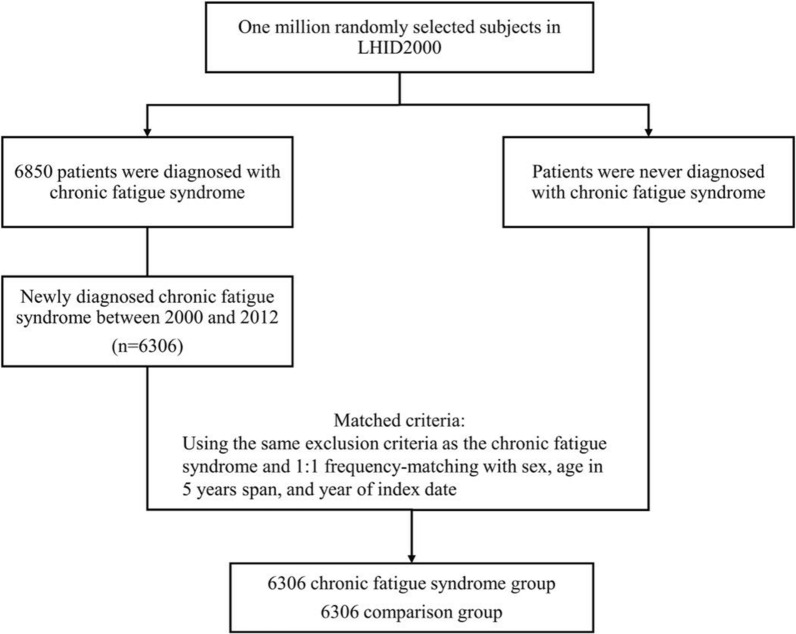

Of the 1,000,000 patients in the LHID2000 database, 6850 patients were diagnosed with CFS. Among these patients, 6306 patients were newly diagnosed with CFS during the study period. In total, 12,612 participants were enrolled, including 6306 CFS patients and 6306 non-CFS patients (Fig. 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The participants were predominantly female and aged 35–64 years. The mean (standard deviation) age was 50.6 years in both groups. Patients in the CFS group most presented with the comorbidities of depression, anxiety disorder, insomnia, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, renal disease, type 2 diabetes, gout, dyslipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren syndrome, and herpes zoster.

Fig. 1.

The selection process of the participants in the cohort study

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients newly diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome in Taiwan between 2000 and 2012 and of those in the control group

| Variable | CFS cohort | Non-CFS cohort | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 6306) | (n = 6306) | ||

| Gender | > 0.99 | ||

| Female | 3339 (52.9) | 3339 (52.9) | |

| Male | 2967 (47.1) | 2967 (47.1) | |

| Age at diagnosis of CFS | > 0.99 | ||

| ≤ 34 | 1350 (21.4) | 1350 (21.4) | |

| 35–64 | 3485 (55.3) | 3485 (55.3) | |

| ≥ 65 | 1471 (23.3) | 1471 (23.3) | |

| Age at diagnosis of CFS(mean, SD)† | 50.6 (17.9) | 50.6 (18.0) | 0.80 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Depression | 807 (12.8) | 407 (6.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 2038 (32.3) | 1033 (16.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Insomnia | 2303 (36.5) | 1106 (17.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Suicide | 19 (0.30) | 12 (0.19) | 0.20 |

| Crohn's disease | 255 (4.04) | 121 (1.92) | < 0.0001 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 279 (4.42) | 138 (2.19) | < 0.0001 |

| Renal disease | 585 (9.28) | 427 (6.77) | < 0.0001 |

| T1DM | 78 (1.24) | 68 (1.08) | 0.40 |

| T2DM | 1473 (23.3) | 1068 (16.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Obesity | 93 (1.47) | 64 (1.01) | 0.01 |

| Gout | 1196 (18.9) | 702 (11.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2252 (35.7) | 1356 (21.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Malignancy | 407 (6.45) | 487 (7.72) | 0.01 |

| HIV | 3 (0.05) | 3 (0.05) | > 0.99 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 254 (4.03) | 155 (2.46) | < 0.0001 |

| Psoriasis | 94 (1.49) | 83 (1.32) | 0.40 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 53 (0.84) | 39 (0.62) | 0.14 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 132 (2.09) | 104 (1.65) | 0.06 |

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | 13 (0.21) | 10 (0.16) | 0.53 |

| Sjogren's syndrome | 110 (1.74) | 71 (1.13) | 0.003 |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 886 (14.1) | 423 (6.71) | < 0.0001 |

| Fibromyalgia | 4905 (77.8) | 4914 (77.9) | 0.85 |

| SLE | 4 (0.06) | 9 (0.14) | 0.16 |

| Herpes zoster | 341 (5.41) | 234 (3.71) | < 0.0001 |

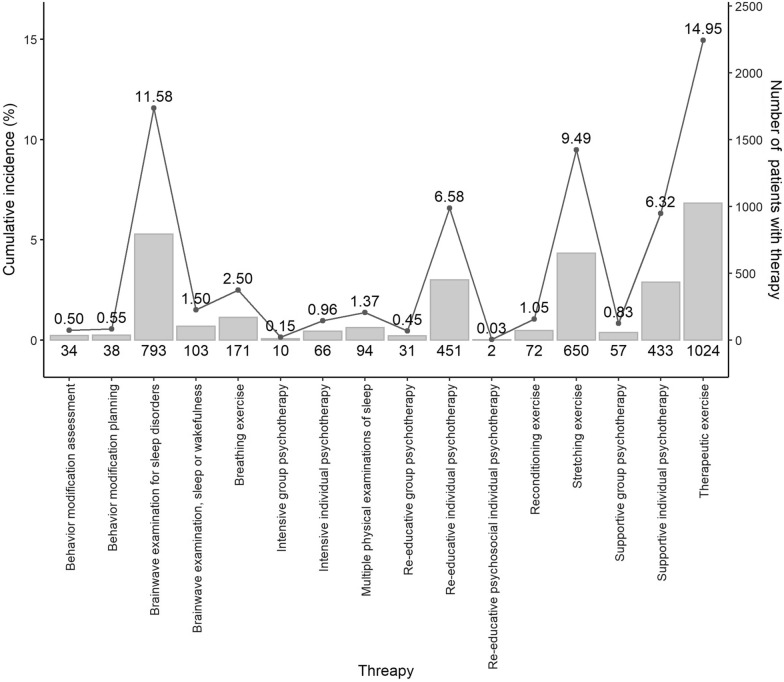

Table 2 lists the treatments received by both the patients with CFS and those without. With adjustments for sex, age, and comorbidities, patients with CFS had higher odds of receiving SSRIs (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.70; 95% CI 1.48, 1.95), SNRIs (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.52; 95% CI 1.20, 1.93), SARIs (aOR = 1.56; 95% CI 1.35, 1.78), TCAs (aOR = 1.37; 95% CI 1.07, 1.76), BZD (aOR = 1.70; 95% CI 1.57, 1.84), NDRI (aOR = 1.59; 95% CI 1.08, 2.36), Muscle relaxant (aOR = 1.52; 95% CI 1.24, 1.86) and Analgesic drug (aOR = 9.55; 95% CI 7.72, 11.81) than patients without CFS. Moreover, psychotherapy, including supportive individual psychotherapy (aOR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.09, 1.51), intensive individual psychotherapy (aOR = 2.73; 95% CI 1.47, 5.04), reeducative individual psychotherapy (aOR = 1.31; 95% CI 1.11, 1.56), stretching exercises (aOR = 1.26; 95% CI 1.10, 1.45), therapeutic exercise (aOR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.19, 1.47), and a brainwave examination for sleep disorders (20001C, 20002C; aOR = 1.40; 95% CI 1.25, 1.55) were frequently prescribed to patients with CFS. Figure 2 demonstrated the cumulative incidence calculated as the number of new patients who received nonpharmaceutical treatment divided by the total number of CFS patients who were at risk and multiple by 100. In 6850 CFS patients, the highest cumulative incidences of treatment were therapeutic exercise (14.95%), followed by brainwave examination for sleep disorders (11.58%) and stretching exercise (9.49%).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for various treatments for patients with and without chronic fatigue syndrome

| Variable | N | Control | CFS | Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| SSRI | 2.33 (2.05,2.66)*** | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.48,1.95)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 11,471 | 5946 | 52 | 5525 | 48 | ||||

| Yes | 1141 | 360 | 32 | 781 | 68 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.22 (1.77,2.78)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.20,1.93)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 12,260 | 6195 | 51 | 6065 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 352 | 111 | 32 | 241 | 68 | ||||

| SARI | 2.21 (1.95,2.52)*** | < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.35,1.78)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 11,451 | 5927 | 52 | 5524 | 48 | ||||

| Yes | 1161 | 379 | 33 | 782 | 67 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.79 (1.42,2.28)*** | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.07,1.76)* | 0.01 | |||||

| No | 12,310 | 6197 | 50 | 6113 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 302 | 109 | 36 | 193 | 64 | ||||

| BZD | 2.13 (1.98,2.29)*** | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.57,1.84)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 5368 | 3260 | 61 | 2108 | 39 | ||||

| Yes | 7244 | 3046 | 42 | 4198 | 58 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.42 (1.67,3.51)*** | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.08,2.36)* | 0.02 | |||||

| No | 12,476 | 6266 | 50 | 6210 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 136 | 40 | 29 | 96 | 71 | ||||

| NaSSA | 2.02 (1.57,2.59)*** | < 0.001 | 1.28 (0.98,1.67) | 0.08 | |||||

| No | 12,331 | 6212 | 50 | 6119 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 281 | 94 | 33 | 187 | 67 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.80 (1.49,2.19)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.24,1.86)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 12,150 | 6139 | 51 | 6011 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 462 | 167 | 36 | 295 | 64 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 12.44 (10.12,15.3)*** | < 0.001 | 9.55 (7.72,11.81)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 1173 | 1071 | 91 | 102 | 9 | ||||

| Yes | 11,439 | 5235 | 46 | 6204 | 54 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.90 (1.63,2.21)*** | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.09,1.51)** | 0.003 | |||||

| No | 11,837 | 6032 | 51 | 5805 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 775 | 274 | 35 | 501 | 65 | ||||

| Supportive group psychotherapy | 2.29 (1.52,3.45)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (0.99,2.35) | 0.057 | |||||

| No | 12,504 | 6273 | 50 | 6231 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 108 | 33 | 31 | 75 | 69 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 3.95 (2.20,7.12)*** | < 0.001 | 2.73 (1.47,5.04)** | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 12,543 | 6292 | 50 | 6251 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 14 | 20 | 55 | 80 | ||||

| Intensive group psychotherapy | 2.13 (0.92,4.93) | 0.078 | 1.57 (0.65,3.78) | 0.318 | |||||

| No | 12,587 | 6298 | 50 | 6289 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 8 | 32 | 17 | 68 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 2.01 (1.72,2.36)*** | < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.11,1.56)** | 0.002 | |||||

| No | 11,881 | 6057 | 51 | 5824 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 731 | 249 | 34 | 482 | 66 | ||||

| Re-educative group psychotherapy | 2.30 (1.37,3.84)** | 0.002 | 1.49 (0.87,2.56) | 0.149 | |||||

| No | 12,543 | 6285 | 50 | 6258 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 21 | 30 | 48 | 70 | ||||

| Behavior modification assessment | |||||||||

| No | 12,612 | 6306 | 50 | 6306 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Behavior modification planning | 1.60 (1.02,2.54)* | 0.043 | 1.15 (0.71,1.86) | 0.582 | |||||

| No | 12,534 | 6276 | 50 | 6258 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 78 | 30 | 38 | 48 | 62 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.44 (1.26,1.64)*** | < 0.001 | 1.26 (1.10,1.45)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 11,600 | 5884 | 51 | 5716 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 1012 | 422 | 42 | 590 | 58 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.47 (1.33,1.63)*** | < 0.001 | 1.33 (1.19,1.47)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 10,768 | 5535 | 51 | 5233 | 49 | ||||

| Yes | 1844 | 771 | 42 | 1073 | 58 | ||||

| Breathing exercise | 1.04 (0.82,1.32) | 0.758 | 0.92 (0.71,1.18) | 0.506 | |||||

| No | 12,343 | 6174 | 50 | 6169 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 269 | 132 | 49 | 137 | 51 | ||||

| Reconditioning exercise | 1.30 (0.94,1.79) | 0.108 | 1.19 (0.85,1.67) | 0.310 | |||||

| No | 12,456 | 6238 | 50 | 6218 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 156 | 68 | 44 | 88 | 56 | ||||

| Multiple physical examinations of sleep | 1.48 (1.10,2.00)* | 0.011 | 1.07 (0.78,1.47) | 0.676 | |||||

| No | 12,434 | 6234 | 50 | 6200 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 178 | 72 | 40 | 106 | 60 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 1.60 (1.44,1.77)*** | < 0.001 | 1.40 (1.25,1.55)*** | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 10,825 | 5590 | 52 | 5235 | 48 | ||||

| Yes | 1787 | 716 | 40 | 1071 | 60 | ||||

| Brainwave examination for sleep disorders | |||||||||

| No | 12,612 | 6306 | 50 | 6306 | 50 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

CFS: chronic fatigue syndrome; N: total number of subjects the subgroups; n: number of subjects; CI: confidence interval; SSRI: selective serotonin receptor inhibitors; SNRI: serotonin norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors; SARI: serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressant; MAOi: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors; BZD: benzodiazepine; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidences of different nonpharmaceutical treatment among the CFS subpopulations

The stratification of treatments for patients with CFS in terms of depression, anxiety disorders, and insomnia is presented in Table 3. For patients with depression, those with CFS were more likely to receive SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs, BZD, analgesic drugs, reeducative individual psychotherapy and therapeutic exercise. SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs, BZD, NDRI, analgesic drugs, muscle relaxants, reeducative individual psychotherapy stretching exercise and therapeutic exercise were commonly prescribed for patients with CFS identified with an anxiety disorder. In the subgroup of patients with insomnia, SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs, BZD, analgesic drugs, reeducative individual psychotherapy and therapeutic exercise were most prescribed to patients with CFS.

Table 3.

The odd ratios of treatments for patients with and without chronic fatigue syndrome in difference subgroup of comorbidities

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 1.69 (1.29,2.22)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.14,2.03)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 5633 | 313 | 4990 | 535 | ||||

| Yes | 266 | 94 | 509 | 272 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.72 (1.67,4.42)*** | < 0.001 | 2.56 (1.55,4.23)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5809 | 386 | 5362 | 703 | ||||

| Yes | 90 | 21 | 137 | 104 | ||||

| SARI | 1.91 (1.43,2.54)*** | < 0.001 | 1.73 (1.28,2.36)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5599 | 328 | 4971 | 553 | ||||

| Yes | 300 | 79 | 528 | 254 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.30 (0.78,2.17) | 0.305 | 1.21 (0.71,2.08) | 0.480 | ||||

| No | 5812 | 385 | 5362 | 751 | ||||

| Yes | 87 | 22 | 137 | 56 | ||||

| BZD | 1.96 (1.42,2.71)*** | < 0.001 | 1.77 (1.24,2.52)** | 0.002 | ||||

| No | 3178 | 82 | 2016 | 92 | ||||

| Yes | 2721 | 325 | 3483 | 715 | ||||

| NDRI | 1.75 (0.93,3.28) | 0.083 | 1.60 (0.82,3.09) | 0.167 | ||||

| No | 5872 | 394 | 5447 | 763 | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 13 | 52 | 44 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.58 (0.92,2.73) | 0.100 | 1.27 (0.72,2.25) | 0.411 | ||||

| No | 5750 | 389 | 5259 | 752 | ||||

| Yes | 149 | 18 | 240 | 55 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 13.7 (6.41,29.15)*** | < 0.001 | 11.15 (5.00,24.87)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1022 | 49 | 94 | 8 | ||||

| Yes | 4877 | 358 | 5405 | 799 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.52 (1.13,2.04)** | 0.006 | 1.27 (0.92,1.74) | 0.142 | ||||

| No | 5700 | 332 | 5204 | 601 | ||||

| Yes | 199 | 75 | 295 | 206 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 1.94 (0.72,5.23) | 0.191 | 1.79 (0.58,5.46) | 0.310 | ||||

| No | 5890 | 402 | 5463 | 788 | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 5 | 36 | 19 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 1.72 (1.28,2.31)*** | < 0.001 | 1.50 (1.10,2.05)* | 0.011 | ||||

| No | 5724 | 333 | 5240 | 584 | ||||

| Yes | 175 | 74 | 259 | 223 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.12 (0.77,1.64) | 0.538 | 1.12 (0.76,1.66) | 0.563 | ||||

| No | 5522 | 362 | 5008 | 708 | ||||

| Yes | 377 | 45 | 491 | 99 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.80 (1.30,2.50)*** | < 0.001 | 1.81 (1.29,2.55)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5184 | 351 | 4606 | 627 | ||||

| Yes | 715 | 56 | 893 | 180 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 1.01 (0.45,2.27) | 0.983 | 0.98 (0.42,2.30) | 0.959 | ||||

| No | 5776 | 398 | 5380 | 789 | ||||

| Yes | 123 | 9 | 119 | 18 | ||||

| Variable | Control | CFS | Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

| Anxiety disorder | ||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 1.70 (1.38,2.09)*** | < 0.001 | 1.54 (1.24,1.92)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5054 | 892 | 3918 | 1607 | ||||

| Yes | 219 | 141 | 350 | 431 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.41 (1.63,3.57)*** | < 0.001 | 2.02 (1.35,3.03)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5194 | 1001 | 4173 | 1892 | ||||

| Yes | 79 | 32 | 95 | 146 | ||||

| SARI | 1.60 (1.31,1.96)*** | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.11,1.7)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 5045 | 882 | 3925 | 1599 | ||||

| Yes | 228 | 151 | 343 | 439 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.25 (0.86,1.83) | 0.238 | 1.14 (0.77,1.68) | 0.508 | ||||

| No | 5204 | 993 | 4173 | 1940 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 40 | 95 | 98 | ||||

| BZD | 1.89 (1.56,2.29)*** | < 0.001 | 1.68 (1.37,2.06)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 3022 | 238 | 1829 | 279 | ||||

| Yes | 2251 | 795 | 2439 | 1759 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.09 (1.21,3.64)** | 0.009 | 1.84 (1.04,3.25)* | 0.037 | ||||

| No | 5249 | 1017 | 4237 | 1973 | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 16 | 31 | 65 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.57 (1.09,2.25)* | 0.015 | 1.46 (1.01,2.11)* | 0.046 | ||||

| No | 5147 | 992 | 4097 | 1914 | ||||

| Yes | 126 | 41 | 171 | 124 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 7.84 (4.7,13.09)*** | < 0.001 | 7.80 (4.55,13.38)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1000 | 71 | 83 | 19 | ||||

| Yes | 4273 | 962 | 4185 | 2019 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.37 (1.09,1.72)** | 0.007 | 1.15 (0.9,1.47) | 0.267 | ||||

| No | 5113 | 919 | 4063 | 1742 | ||||

| Yes | 160 | 114 | 205 | 296 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 2.34 (1.03,5.31)* | 0.043 | 1.87 (0.79,4.46) | 0.155 | ||||

| No | 5266 | 1026 | 4245 | 2006 | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 7 | 23 | 32 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 1.58 (1.25,2.00)*** | < 0.001 | 1.34 (1.04,1.73)* | 0.025 | ||||

| No | 5128 | 929 | 4092 | 1732 | ||||

| Yes | 145 | 104 | 176 | 306 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.49 (1.15,1.93)** | 0.003 | 1.44 (1.1,1.88)** | 0.008 | ||||

| No | 4936 | 948 | 3918 | 1798 | ||||

| Yes | 337 | 85 | 350 | 240 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.32 (1.08,1.61)** | 0.006 | 1.29 (1.05,1.58)* | 0.016 | ||||

| No | 4669 | 866 | 3609 | 1624 | ||||

| Yes | 604 | 167 | 659 | 414 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 0.69 (0.44,1.09) | 0.109 | 0.67 (0.42,1.07) | 0.095 | ||||

| No | 5175 | 999 | 4178 | 1991 | ||||

| Yes | 98 | 34 | 90 | 47 | ||||

| Variable | Control | CFS | Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

| Insomnia | ||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 1.81 (1.47,2.24)*** | < 0.001 | 1.65 (1.32,2.06)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 4969 | 977 | 3667 | 1858 | ||||

| Yes | 231 | 129 | 336 | 445 | ||||

| SNRI | 1.74 (1.23,2.47)** | 0.002 | 1.54 (1.07,2.21)* | 0.019 | ||||

| No | 5131 | 1064 | 3910 | 2155 | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 42 | 93 | 148 | ||||

| SARI | 1.45 (1.2,1.76)*** | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.06,1.59)* | 0.011 | ||||

| No | 4991 | 936 | 3701 | 1823 | ||||

| Yes | 209 | 170 | 302 | 480 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.62 (1.09,2.4)* | 0.018 | 1.58 (1.05,2.38)* | 0.027 | ||||

| No | 5124 | 1073 | 3919 | 2194 | ||||

| Yes | 76 | 33 | 84 | 109 | ||||

| BZD | 1.43 (1.2,1.71)*** | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.14,1.66)** | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 3008 | 252 | 1714 | 394 | ||||

| Yes | 2192 | 854 | 2289 | 1909 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.01 (1.14,3.55)* | 0.016 | 1.75 (0.97,3.16) | 0.062 | ||||

| No | 5175 | 1091 | 3969 | 2241 | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 15 | 34 | 62 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.19 (0.86,1.65) | 0.285 | 1.11 (0.80,1.55) | 0.530 | ||||

| No | 5087 | 1052 | 3841 | 2170 | ||||

| Yes | 113 | 54 | 162 | 133 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 8.75 (5.77,13.25)*** | < 0.001 | 8.00 (5.16,12.4)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 960 | 111 | 73 | 29 | ||||

| Yes | 4240 | 995 | 3930 | 2274 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.26 (1.01,1.59)* | 0.044 | 1.03 (0.81,1.32) | 0.784 | ||||

| No | 5042 | 990 | 3799 | 2006 | ||||

| Yes | 158 | 116 | 204 | 297 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 1.63 (0.74,3.6) | 0.228 | 1.31 (0.57,3.02) | 0.519 | ||||

| No | 5194 | 1098 | 3975 | 2276 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 8 | 28 | 27 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 1.57 (1.24,2)*** | < 0.001 | 1.35 (1.04,1.74)* | 0.024 | ||||

| No | 5049 | 1008 | 3826 | 1998 | ||||

| Yes | 151 | 98 | 177 | 305 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.30 (1.02,1.66)* | 0.033 | 1.26 (0.99,1.62) | 0.064 | ||||

| No | 4878 | 1006 | 3677 | 2039 | ||||

| Yes | 322 | 100 | 326 | 264 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.52 (1.25,1.84)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.25,1.86)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 4591 | 944 | 3406 | 1827 | ||||

| Yes | 609 | 162 | 597 | 476 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 0.84 (0.56,1.26) | 0.405 | 0.88 (0.58,1.33) | 0.539 | ||||

| No | 5106 | 1068 | 3933 | 2236 | ||||

| Yes | 94 | 38 | 70 | 67 | ||||

CFS: chronic fatigue syndrome; CI: confidence interval; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

As presented in Table 4, patients with CFS were more likely to receive SSRIs, BZD and analgesic drugs in each age group. The odds of patients with CFS aged 35–64 and ≥ 65 receiving SARIs and muscle relaxant treatments were higher than the odds of those without CFS. For participants aged 35–64 years, reeducative individual psychotherapy was also frequently received by patients with CFS. Female and male patients with CFS were equally likely to be treated with SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs, BZD, muscle relaxants, analgesic drugs, reeducative individual psychotherapy, intensive individual psychotherapy and therapeutic exercise, TCAs was higher prescribed to female and NDRI was higher used in male, as presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

The odd ratios of treatments for patients with and without chronic fatigue syndrome in difference subgroup of age

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤ 34 y/o | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 1.98 (1.43,2.74)*** | < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.08,2.15)* | 0.015 | ||||

| No | 4758 | 1188 | 4386 | 1139 | ||||

| Yes | 300 | 60 | 667 | 114 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.13 (1.23,3.7)** | 0.007 | 1.39 (0.77,2.52) | 0.272 | ||||

| No | 4966 | 1229 | 4852 | 1213 | ||||

| Yes | 92 | 19 | 201 | 40 | ||||

| SARI | 1.82 (1.25,2.65)** | 0.002 | 1.20 (0.8,1.8) | 0.375 | ||||

| No | 4724 | 1203 | 4351 | 1173 | ||||

| Yes | 334 | 45 | 702 | 80 | ||||

| TCAs | 2.17 (1.12,4.21)* | 0.022 | 1.59 (0.78,3.22) | 0.2 | ||||

| No | 4962 | 1235 | 4888 | 1225 | ||||

| Yes | 96 | 13 | 165 | 28 | ||||

| BZD | 1.91 (1.62,2.25)*** | < 0.001 | 1.61 (1.36,1.92)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2380 | 880 | 1411 | 697 | ||||

| Yes | 2678 | 368 | 3642 | 556 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.29 (0.94,5.59) | 0.068 | 1.34 (0.5,3.56) | 0.557 | ||||

| No | 5025 | 1241 | 4973 | 1237 | ||||

| Yes | 33 | 7 | 80 | 16 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.88 (1.1,3.21)* | 0.021 | 1.69 (0.97,2.96) | 0.065 | ||||

| No | 4912 | 1227 | 4797 | 1214 | ||||

| Yes | 146 | 21 | 256 | 39 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 3.94 (2.57,6.02)*** | < 0.001 | 3.89 (2.49,6.06)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 968 | 103 | 74 | 28 | ||||

| Yes | 4090 | 1145 | 4979 | 1225 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.74 (1.23,2.45)** | 0.002 | 1.13 (0.77,1.64) | 0.531 | ||||

| No | 4839 | 1193 | 4645 | 1160 | ||||

| Yes | 219 | 55 | 408 | 93 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 5.37 (1.56,18.47)** | 0.008 | 3.34 (0.92,12.17) | 0.067 | ||||

| No | 5047 | 1245 | 5014 | 1237 | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 3 | 39 | 16 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 1.85 (1.29,2.65)*** | < 0.001 | 1.20 (0.81,1.79) | 0.362 | ||||

| No | 4858 | 1199 | 4659 | 1165 | ||||

| Yes | 200 | 49 | 394 | 88 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.21 (0.86,1.70) | 0.274 | 1.15 (0.81,1.63) | 0.425 | ||||

| No | 4701 | 1183 | 4541 | 1175 | ||||

| Yes | 357 | 65 | 512 | 78 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.08 (0.84,1.39) | 0.544 | 0.98 (0.76,1.28) | 0.89 | ||||

| No | 4418 | 1117 | 4121 | 1112 | ||||

| Yes | 640 | 131 | 932 | 141 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 0.63 (0.24,1.64) | 0.344 | 0.60 (0.22,1.65) | 0.321 | ||||

| No | 4937 | 1237 | 4923 | 1246 | ||||

| Yes | 121 | 11 | 130 | 7 | ||||

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 35–64 y/o | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 2.15 (1.85,2.50)*** | < 0.001 | 1.57 (1.34,1.85)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1389 | 4557 | 1251 | 4274 | ||||

| Yes | 82 | 278 | 220 | 561 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.23 (1.71,2.90)*** | < 0.001 | 1.56 (1.18,2.07)** | 0.002 | ||||

| No | 1443 | 4752 | 1411 | 4654 | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 83 | 60 | 181 | ||||

| SARI | 2.19 (1.88,2.55)*** | < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.3,1.81)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1356 | 4571 | 1232 | 4292 | ||||

| Yes | 115 | 264 | 239 | 543 | ||||

| TCAs | 2.09 (1.57,2.79)*** | < 0.001 | 1.66 (1.22,2.24)** | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1432 | 4765 | 1422 | 4691 | ||||

| Yes | 39 | 70 | 49 | 144 | ||||

| BZD | 2.15 (1.98,2.33)*** | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.56,1.87)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 474 | 2786 | 236 | 1872 | ||||

| Yes | 997 | 2049 | 1235 | 2963 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.19 (1.46,3.3)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (0.99,2.35) | 0.057 | ||||

| No | 1465 | 4801 | 1449 | 4761 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 34 | 22 | 74 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.73 (1.38,2.18)*** | < 0.001 | 1.46 (1.14,1.85)** | 0.002 | ||||

| No | 1424 | 4715 | 1380 | 4631 | ||||

| Yes | 47 | 120 | 91 | 204 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 9.18 (7.27,11.59)*** | < 0.001 | 6.83 (5.38,8.66)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 410 | 661 | 20 | 82 | ||||

| Yes | 1061 | 4174 | 1451 | 4753 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.82 (1.53,2.16)*** | < 0.001 | 1.20 (1,1.45) | 0.054 | ||||

| No | 1415 | 4617 | 1352 | 4453 | ||||

| Yes | 56 | 218 | 119 | 382 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 4.11 (2.19,7.75)*** | < 0.001 | 2.95 (1.52,5.73)** | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1469 | 4823 | 1465 | 4786 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 12 | 6 | 49 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 2.01 (1.68,2.39)*** | < 0.001 | 1.33 (1.1,1.61)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 1423 | 4634 | 1376 | 4448 | ||||

| Yes | 48 | 201 | 95 | 387 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.43 (1.23,1.67)*** | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.08,1.49)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 1360 | 4524 | 1315 | 4401 | ||||

| Yes | 111 | 311 | 156 | 434 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.42 (1.26,1.59)*** | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.13,1.45)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1256 | 4279 | 1150 | 4083 | ||||

| Yes | 215 | 556 | 321 | 752 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 1.08 (0.79,1.50) | 0.622 | 0.98 (0.69,1.37) | 0.889 | ||||

| No | 1411 | 4763 | 1412 | 4757 | ||||

| Yes | 60 | 72 | 59 | 78 | ||||

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 65 y/o | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 2.98 (2.29,3.88)*** | < 0.001 | 2.17 (1.64,2.88)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 4557 | 1389 | 4274 | 1251 | ||||

| Yes | 278 | 82 | 561 | 220 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.19 (1.39,3.45)*** | < 0.001 | 1.46 (0.9,2.37) | 0.121 | ||||

| No | 4752 | 1443 | 4654 | 1411 | ||||

| Yes | 83 | 28 | 181 | 60 | ||||

| SARI | 2.29 (1.81,2.89)*** | < 0.001 | 1.69 (1.31,2.17)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 4571 | 1356 | 4292 | 1232 | ||||

| Yes | 264 | 115 | 543 | 239 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.27 (0.83,1.94) | 0.28 | 0.89 (0.56,1.42) | 0.633 | ||||

| No | 4765 | 1432 | 4691 | 1422 | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 39 | 144 | 49 | ||||

| BZD | 2.49 (2.08,2.97)*** | < 0.001 | 1.72 (1.42,2.09)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2786 | 474 | 1872 | 236 | ||||

| Yes | 2049 | 997 | 2963 | 1235 | ||||

| NDRI | 3.71 (1.5,9.17)** | 0.005 | 2.33 (0.9,6.03) | 0.082 | ||||

| No | 4801 | 1465 | 4761 | 1449 | ||||

| Yes | 34 | 6 | 74 | 22 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 2.00 (1.39,2.86)*** | < 0.001 | 1.75 (1.2,2.56)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 4715 | 1424 | 4631 | 1380 | ||||

| Yes | 120 | 47 | 204 | 91 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 28.0 (17.77,44.22)*** | < 0.001 | 27.1 (16.65,44.03)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 661 | 410 | 82 | 20 | ||||

| Yes | 4174 | 1061 | 4753 | 1451 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 2.22 (1.6,3.08)*** | < 0.001 | 1.58 (1.11,2.24)* | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 4617 | 1415 | 4453 | 1352 | ||||

| Yes | 218 | 56 | 382 | 119 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 3.01 (0.61,14.93) | 0.178 | 1.47 (0.26,8.18) | 0.662 | ||||

| No | 4823 | 1469 | 4786 | 1465 | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 2 | 49 | 6 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 2.05 (1.44,2.92)*** | < 0.001 | 1.28 (0.87,1.88) | 0.207 | ||||

| No | 4634 | 1423 | 4448 | 1376 | ||||

| Yes | 201 | 48 | 387 | 95 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.45 (1.13,1.88)** | 0.004 | 1.29 (0.99,1.69) | 0.063 | ||||

| No | 4524 | 1360 | 4401 | 1315 | ||||

| Yes | 311 | 111 | 434 | 156 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.63 (1.35,1.97)*** | < 0.001 | 1.48 (1.21,1.82)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 4279 | 1256 | 4083 | 1150 | ||||

| Yes | 556 | 215 | 752 | 321 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 0.98 (0.68,1.42) | 0.925 | 0.86 (0.58,1.27) | 0.447 | ||||

| No | 4763 | 1411 | 4757 | 1412 | ||||

| Yes | 72 | 60 | 78 | 59 | ||||

CFS: chronic fatigue syndrome; CI: confidence interval; *:p-value; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

Table 5.

The odd ratios of treatments for patients with and without chronic fatigue syndrome in difference subgroup of sex

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 2.36 (1.99,2.81)*** | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.42,2.06)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2815 | 3131 | 2639 | 2886 | ||||

| Yes | 152 | 208 | 328 | 453 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.04 (1.51,2.75)*** | < 0.001 | 1.42 (1.04,1.95)* | 0.029 | ||||

| No | 2922 | 3273 | 2858 | 3207 | ||||

| Yes | 45 | 66 | 109 | 132 | ||||

| SARI | 2.10 (1.77,2.5)*** | < 0.001 | 1.46 (1.21,1.76)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2805 | 3122 | 2611 | 2913 | ||||

| Yes | 162 | 217 | 356 | 426 | ||||

| TCAs | 2.25 (1.62,3.13)*** | < 0.001 | 1.69 (1.2,2.38)** | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 2911 | 3286 | 2891 | 3222 | ||||

| Yes | 56 | 53 | 76 | 117 | ||||

| BZD | 2.22 (2.01,2.46)*** | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.53,1.92)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1663 | 1597 | 1133 | 975 | ||||

| Yes | 1304 | 1742 | 1834 | 2364 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.16 (1.28,3.63)** | 0.004 | 1.39 (0.8,2.4) | 0.241 | ||||

| No | 2948 | 3318 | 2916 | 3294 | ||||

| Yes | 19 | 21 | 51 | 45 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.89 (1.45,2.45)*** | < 0.001 | 1.52 (1.15,2.01)** | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 2889 | 3250 | 2836 | 3175 | ||||

| Yes | 78 | 89 | 131 | 164 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 13.54 (9.80,18.7)*** | < 0.001 | 10.11 (7.26,14.09)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 590 | 481 | 61 | 41 | ||||

| Yes | 2377 | 2858 | 2906 | 3298 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 1.74 (1.42,2.13)*** | < 0.001 | 1.19 (0.96,1.48) | 0.121 | ||||

| No | 2851 | 3181 | 2731 | 3074 | ||||

| Yes | 116 | 158 | 236 | 265 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 4.03 (1.85,8.76)*** | < 0.001 | 2.76 (1.21,6.3)* | 0.016 | ||||

| No | 2961 | 3331 | 2944 | 3307 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 8 | 23 | 32 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 1.98 (1.61,2.44)*** | < 0.001 | 1.26 (1.01,1.59)* | 0.045 | ||||

| No | 2860 | 3197 | 2755 | 3069 | ||||

| Yes | 107 | 142 | 212 | 270 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.49 (1.26,1.77)*** | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.09,1.56)** | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 2787 | 3097 | 2726 | 2990 | ||||

| Yes | 180 | 242 | 241 | 349 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.39 (1.22,1.59)*** | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.07,1.43)** | 0.003 | ||||

| No | 2637 | 2898 | 2477 | 2756 | ||||

| Yes | 330 | 441 | 490 | 583 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 1.42 (0.99,2.04) | 0.057 | 1.18 (0.81,1.74) | 0.393 | ||||

| No | 2886 | 3288 | 2902 | 3267 | ||||

| Yes | 81 | 51 | 65 | 72 | ||||

| Variable | Control (n = 6306) |

CFS (n = 6306) |

Odds ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Crude (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

| SSRI | 2.3 (1.89,2.81)*** | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.37,2.10)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 3131 | 2815 | 2886 | 2639 | ||||

| Yes | 208 | 152 | 453 | 328 | ||||

| SNRI | 2.48 (1.74,3.52)*** | < 0.001 | 1.64 (1.13,2.38)** | 0.009 | ||||

| No | 3273 | 2922 | 3207 | 2858 | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 45 | 132 | 109 | ||||

| SARI | 2.36 (1.95,2.86)*** | < 0.001 | 1.71 (1.38,2.10)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 3122 | 2805 | 2913 | 2611 | ||||

| Yes | 217 | 162 | 426 | 356 | ||||

| TCAs | 1.37 (0.96,1.94) | 0.079 | 1.06 (0.73,1.53) | 0.771 | ||||

| No | 3286 | 2911 | 3222 | 2891 | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 56 | 117 | 76 | ||||

| BZD | 2.06 (1.86,2.29)*** | < 0.001 | 1.69 (1.50,1.90)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 1597 | 1663 | 975 | 1133 | ||||

| Yes | 1742 | 1304 | 2364 | 1834 | ||||

| NDRI | 2.71 (1.60,4.61)*** | < 0.001 | 1.81 (1.03,3.17)* | 0.039 | ||||

| No | 3318 | 2948 | 3294 | 2916 | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 19 | 45 | 51 | ||||

| Muscle relaxant | 1.71 (1.29,2.28)*** | < 0.001 | 1.53 (1.13,2.07)** | 0.005 | ||||

| No | 3250 | 2889 | 3175 | 2836 | ||||

| Yes | 89 | 78 | 164 | 131 | ||||

| Analgesic drug | 11.82 (9.03,15.47)*** | < 0.001 | 9.40 (7.11,12.43)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 481 | 590 | 41 | 61 | ||||

| Yes | 2858 | 2377 | 3298 | 2906 | ||||

| Supportive individual psychotherapy | 2.12 (1.69,2.67)*** | < 0.001 | 1.38 (1.08,1.77)* | 0.012 | ||||

| No | 3181 | 2851 | 3074 | 2731 | ||||

| Yes | 158 | 116 | 265 | 236 | ||||

| Intensive individual psychotherapy | 3.86 (1.57,9.48)** | 0.003 | 2.56 (1.00,6.57) | 0.051 | ||||

| No | 3331 | 2961 | 3307 | 2944 | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 6 | 32 | 23 | ||||

| Re-educative individual psychotherapy | 2.06 (1.62,2.61)*** | < 0.001 | 1.39 (1.07,1.80)* | 0.014 | ||||

| No | 3197 | 2860 | 3069 | 2755 | ||||

| Yes | 142 | 107 | 270 | 212 | ||||

| Stretching exercise | 1.37 (1.12,1.67)** | 0.002 | 1.21 (0.98,1.49) | 0.081 | ||||

| No | 3097 | 2787 | 2990 | 2726 | ||||

| Yes | 242 | 180 | 349 | 241 | ||||

| Therapeutic exercise | 1.58 (1.36,1.84)*** | < 0.001 | 1.44 (1.23,1.69)*** | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 2898 | 2637 | 2756 | 2477 | ||||

| Yes | 441 | 330 | 583 | 490 | ||||

| Brainwave examination, sleep or wakefulness | 0.8 (0.57,1.11) | 0.181 | 0.75 (0.53,1.07) | 0.117 | ||||

| No | 3288 | 2886 | 3267 | 2902 | ||||

| Yes | 51 | 81 | 72 | 65 | ||||

CFS: chronic fatigue syndrome; CI: confidence interval;*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

Discussion

Our nationwide population-based study revealed that patients with CFS experienced more comorbidities, such as psychiatric problems (depression, anxiety disorders, and insomnia), autoimmune diseases (Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren syndrome), type 2 diabetes, renal diseases, and malignancy, than the participants without CFS. In addition, we found that the use of SSRIs, SARIs, SNRIs, TCAs, NDRI, BZD, muscle relaxants, analgesic drugs, psychotherapies and exercise therapies were higher in the CFS cohort. This finding is consistent with the general treatment for CFS [14]. Notably, brainwave examination is not a standard examination method for diagnosing CFS, but it was regularly used by clinicians in our study.

The etiology of CFS remains unknown. Emerging research suggests CFS is an autoimmune disease, with evidence of dysregulation of the immune and autonomic nervous systems as well as metabolic disturbances, triggered particularly by infection with stress [15]. Patients with CFS have been identified as having increased levels of autoantibodies against ß2-adrenergic receptors and M3 acetylcholine receptors [16]. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis maintains homeostasis through a self-regulating feedback system that helps to manage stress [17, 18], and abnormalities in the HPA axis are believed to be a feature of CFS [19]. In addition, we previously reported that psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease significantly increased the risk of CFS [10, 11]. In future studies, the aspects of CFS linked to autoimmune diseases should be clarified.

In recent 2 years during COVID-19 pandemic, many studies indicated that some COVID-19 patients had persistent clinical signs and symptoms including fatigue, breathlessness, and cognitive dysfunction after recovering from initial illness. This condition named Post COVID-19 Syndrome or long COVID. Pathological inflammation with immune dysfunction was a one of the underlying multifactorial mechanism of long COVID, which was similar to CFS [20–22]. Various autoantibodies were found in 10–50% of patients with COVID-19 [23]. These autoantibodies and increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers contributed to the disease severity and inflammation-related symptoms such as fatigue and joint pain [22, 24]. The treatments of CFS were believed to have a potential effect of relieving fatigue in long COVID cases [22, 25]. Future studies should be conducted to determine the underlying mechanism and treatments between CFS and long COVID.

Our comparison of patients with CFS with those without demonstrated that the use of SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs and BZD was higher in the CFS cohort after adjustments for age, sex, and comorbidities (Table 2), especially in those with psychiatric problems (depression, anxiety disorders, and insomnia; Table 3). However, a subclassification analysis of age and sex established no significant differences between the two groups (Tables 4 and 5). Patients with CFS have been reported to have clinical depression and anxiety [26], and several pathophysiologies related to depression have been reported, such as inflammation with elevated cytokine levels (e.g., interleukin [IL]-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]), increased oxidative stress, and decreased neurotrophic factors and brain neurotransmitters [27]. Serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A [5-HT1A]), a monoamine neurotransmitter, has been discovered to be linked to mood, behavior, sleep cycles, and appetite [28]. One study indicated that the number of brain 5-HT1A receptors was decreased in patients with CFS, with the decrease particularly marked in the bilateral hippocampus [29]. Furthermore, changes in the HPA axis in chronic stress were reported to be associated with the serotonin system and abnormal adrenocortical activity and were observed in patients with CFS [30]. One study indicated that patients with CFS prescribed SSRIs had a faster rate of recovery and experienced a greater reduction in fatigue levels than untreated patients [31]. However, few clinical trials have been conducted on CFS treatments, although the use of SSRIs for fibromyalgia, especially for patients with depression, may be advantageous for CFS [32]. Bupropion, a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), was reported to improve hypersomnia and fatigue significantly in the patients with major depressive disorder compared with the placebo-group [33]. Unrefreshing sleep is one feature of CFS, Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and sleep hygiene education should be applied whenever possible [34]. Experienced clinicians believed that low-dose TCAs and BZD may also be useful for sleep. However, monitoring the adverse effects including drowsiness upon awakening must be considered.

Treatments for pain symptoms, including muscle relaxants and analgesic drugs, were more common among the CFS cohort (Table 2), but no significant difference in psychiatric comorbidities, age, or sex was identified in the subclassification analysis (Tables 3, 4, and 5). Chronic pain in the muscles, joints, and subcutaneous tissues was a common presenting symptom in patients with CFS. The potential contributing mechanisms may be oxidative and nitrosative stress, low-grade inflammation, and impaired heat shock protein production [35]. Another hypothesis concerning muscle fatigue is that it results from the overutilization of the lactate dehydrogenase pathway and slowed acid clearance after exercise [36]. The mainstream management of pain in CFS is similar to that for fibromyalgia. Pain can be treated with NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Pregabalin or gabapentin are helpful for neuropathic and fibromyalgia pain [37]; however, clinicians should be aware of the adverse effects of this treatment on cognitive dysfunction and weight gain. One systematic review indicated that cyclobenzaprine was more effective for back pain [38] but was associated with the side effects of drowsiness, dizziness, and dry mouth. Nonpharmacologic interventions for pain vary, and useful modalities include meditation, warm baths, massage, stretching, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, chiropractic, yoga, tai chi, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [14, 39].

According to the information released by NHIRD and clinical experiences, the supportive individual psychotherapy is performed by various professional members in psychiatric team under the psychiatrists’ guidance. The re-educative individual psychotherapy is mainly performed by psychotherapists and the intensive individual psychotherapy is administered by psychiatrists. Our results found the application of all psychotherapy was higher in the CFS cohort since those with psychiatric problems are mostly referred to psychotherapists for re-educative individual psychotherapy. However, the group psychotherapy is not a first choice for clinicians in Taiwan. In the age and sex subclassification analysis, psychotherapy was not prescribed significantly more frequently to young aged (below or equal to 34 y/o) patients. With regard to nonpharmaceutical options, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a psychotherapy, has been prescribed to patients with CFS. CBT includes relaxation exercises, the development of coping mechanisms, and stress management, and it is an effective treatment for depression and anxiety and eating and panic disorders [40]. One randomized trial reported that CBT and graded exercise therapy (GET) were safe for CFS and effective at improving fatigue and functional impairment [41, 42]. A 16 week standard individual CBT has been shown to be beneficial in physical function and fatigue [43]. Furthermore, CBT is the most cost-effective treatment option for CFS [44]. Although CBT is often used with GET, the program should be discussed with patients to ensure their compliance.

Brainwave examination was also significantly more frequently prescribed in the CFS cohort (OR = 1.40; Table 2), regardless of whether the participant had depression, an anxiety disorder, or insomnia (Table 3). On the other hand, polysomnography (PSG), including brainwave examination (EEG), eye movements (EOG), muscle activity or skeletal muscle activation (EMG), and heart rhythm (ECG) records certain body functions during sleeping, Nonrestorative sleep is a key feature of CFS and is defined as the subjective experience that sleep has not been sufficiently refreshing or restorative [45, 46], resulting in increased daytime drowsiness, mental fatigue, and neurocognitive impairment [47]. Primary sleep disorders (PSDs), including primary insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, and narcolepsy, occur in approximately 18% of patients with CFS [48]. PSG is a key tool for detecting these disorders. Patients with more severe symptoms should be routinely screened for PSDs with appropriate questionnaires, a semistructured history interview, and PSG [49].

Some emerging management strategies for CFS have been proposed in recent years. The fact that drugs targeting immune responses or impaired autoregulation of blood flow was indicated to be effectual in CFS [50]. We previously discovered that the increased risk of CFS among patients with psoriasis was attenuated by immunomodulatory drugs [11]. In addition, a small placebo-controlled and open study mentioned that rituximab achieved sustained clinical responses in patients with CFS [51], and a clinical trial demonstrated that rintatolimod, a restricted toll-like receptor 3 agonist, achieved significant improvements in patients with CFS [52]. Furthermore, increased levels of several cytokines, including IL-1 and TNF-α, have been positively correlated with fatigue [53]. These findings provide insight into treating CFS through immune pathways. Another emerging treatment of CFS is dietary intervention, with one systemic review indicating that nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride, coenzyme Q10, and probiotic supplements relieved CFS symptoms [54]. These potential mechanisms contribute by increasing adenosine triphosphate production and improving gut microbiota. Aripiprazole was reported to relieve the symptoms of CFS including fatigue and unrefreshing sleep effectively [55]. Biofeedback therapy has also demonstrated benefits in the treatment of CFS. Compared with GET, heart rate variability biofeedback therapy has improved quality of life in cases of mental health disorders, including depression, potentially through the enhancement of self-efficacy and self-control [56].

Our study has some limitations. First, the severity of CFS and efficacy of the treatment were not evaluated in the study because of limited information available in the NHIRD. Second, some nonpharmaceutical treatments, such as meditation and massage, were not included in our study because they were not included in the database. Third, patients’ personal information and family histories, such as symptoms, occupation, and laboratory data, were not available because of the anonymity of the NHIRD. Fourth, incorrect coding and diagnoses in the database may have resulted in bias in the data analysis; however, such errors may result in considerable penalties for physicians, and hence, they are unlikely. Moreover, data on 99.9% of Taiwan’s population are contained in the NHIRD, making the database a robust source of data, the reliability and validity of which have been reported previously [57]. Consequently, the diagnoses and codes should be reliable in our study.

Conclusion

In our nationwide population-based cohort study, the use of SSRIs, SARIs, SNRIs, TCAs, NDRI, BZD, muscle relaxants, analgesic drugs, psychotherapies and exercise therapies were prescribed significantly more frequently in the CFS cohort than in the control group. Previous studies have reported these treatments to be effective at relieving the symptoms of CFS and useful for managing related comorbidities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend acknowledgment to Dr. Jung-Nien Lai’s and Miss. Yu-Chi Yang's material support, and the listed institutes and Department of Medical Research at Mackay Memorial Hospital, and Mackay Medical College for funding support.

Author contributions

S-YT. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: S-YT. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: K-HL, C-FK, and S-YT,. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important: S-YT. Intellectual content: S-YT; Statistical analysis: H-TY Obtained funding: S-YT, H-TY. Administrative, technical, or material supports: S-YT, and H-TY. Study supervision: S-YT. Submission: K-HL and S-YT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW109-TDU-B-212-114004), MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 109-2321-B-039-002), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-109-231), Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan, Mackay Medical College (1082A03), Department of Medical Research at Mackay Memorial Hospital (MMH-107-135; MMH-109-79; MMH-109-103).

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this study is from the National Health Insurance Research database (NHIRD). Interested researchers can obtain the data through formal application to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the China Medical University Hospital (CMUH-104-REC2-115) and the Institutional Review Board of Mackay Memorial Hospital (16MMHIS074).

Consent for publication

The authors agree with the publication of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kam-Hang Leong, Hei-Tung Yip and Chien-Feng Kuo are joint first authors and contributed equally to this paper

References

- 1.Komaroff AL. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a real illness. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(12):871–872. doi: 10.7326/M15-0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, Staines D, Powles AC, Speight N, Vallings R, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270(4):327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo CF, Shi L, Lin CL, Yao WC, Chen HT, Lio CF, Wang YT, Su CH, Hsu NW, Tsai SY. How peptic ulcer disease could potentially lead to the lifelong, debilitating effects of chronic fatigue syndrome: an insight. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7520. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87018-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang TY, Lin CL, Yao WC, Lio CF, Chiang WP, Lin K, Kuo CF, Tsai SY. How mycobacterium tuberculosis infection could lead to the increasing risks of chronic fatigue syndrome and the potential immunological effects: a population-based retrospective cohort study. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03301-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maes M, Twisk FN. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Harvey and Wessely's (bio)psychosocial model versus a bio(psychosocial) model based on inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. BMC Med. 2010;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris G, Maes M. A neuro-immune model of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28(4):523–540. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maes M, Mihaylova I, De Ruyter M. Lower serum zinc in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS): relationships to immune dysfunctions and relevance for the oxidative stress status in CFS. J Affect Disord. 2006;90(2–3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai SY, Lin CL, Shih SC, Hsu CW, Leong KH, Kuo CF, Lio CF, Chen YT, Hung YJ, Shi L. Increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome following burn injuries. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1713-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SY, Chen HJ, Lio CF, Kuo CF, Kao AC, Wang WS, Yao WC, Chen C, Yang TY. Increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based retrospective cohort study. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1797-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai SY, Chen HJ, Chen C, Lio CF, Kuo CF, Leong KH, Wang YT, Yang TY, You CH, Wang WS. Increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome following psoriasis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai SY, Yang TY, Chen HJ, Chen CS, Lin WM, Shen WC, Kuo CN, Kao CH. Increased risk of chronic fatigue syndrome following herpes zoster: a population-based study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(9):1653–1659. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collin SM, Crawley E, May MT, Sterne JA, Hollingworth W. Database UCMNO: The impact of CFS/ME on employment and productivity in the UK: a cross-sectional study based on the CFS/ME national outcomes database. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:217. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(4):223–249. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2015-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sotzny F, Blanco J, Capelli E, Castro-Marrero J, Steiner S, Murovska M, Scheibenbogen C. European Network on MC: myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome—evidence for an autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(6):601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loebel M, Grabowski P, Heidecke H, Bauer S, Hanitsch LG, Wittke K, Meisel C, Reinke P, Volk HD, Fluge O, et al. Antibodies to beta adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;52:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanfumey L, Mongeau R, Cohen-Salmon C, Hamon M. Corticosteroid-serotonin interactions in the neurobiological mechanisms of stress-related disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(6):1174–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleare AJ. The neuroendocrinology of chronic fatigue syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(2):236–252. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadopoulos AS, Cleare AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;8(1):22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt J, Blease C, Geraghty KJ: Long Covid at the crossroads: Comparisons and lessons from the treatment of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J Health Psychol 2022:13591053221084494. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Aiyegbusi OL, Hughes SE, Turner G, Rivera SC, McMullan C, Chandan JS, Haroon S, Price G, Davies EH, Nirantharakumar K, et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: a review. J R Soc Med. 2021;114(9):428–442. doi: 10.1177/01410768211032850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yong SJ. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infect Dis. 2021;53(10):737–754. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1924397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao ZW, Zhang HZ, Liu C, Dong K. Autoantibodies in COVID-19: frequency and function. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(3):102754. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou M, Yin Z, Xu J, Wang S, Liao T, Wang K, Li Y, Yang F, Wang Z, Yang G, et al. Inflammatory Profiles and Clinical Features of Coronavirus 2019 Survivors 3 Months After Discharge in Wuhan, China. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(9):1473–1488. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komaroff AL, Buchwald DS. Chronic fatigue syndrome: an update. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:1–13. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(1):22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammad-Zadeh LF, Moses L, Gwaltney-Brant SM. Serotonin: a review. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(3):187–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleare AJ, Messa C, Rabiner EA, Grasby PM. Brain 5-HT1A receptor binding in chronic fatigue syndrome measured using positron emission tomography and [11C]WAY-100635. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poteliakhoff A. Adrenocortical activity and some clinical findings in acute and chronic fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1981;25(2):91–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(81)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas MA, Smith AP. An investigation of the long-term benefits of antidepressant medication in the recovery of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(8):503–509. doi: 10.1002/hup.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walitt B, Urrutia G, Nishishinya MB, Cantrell SE, Hauser W. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD011735. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papakostas GI, Nutt DJ, Hallett LA, Tucker VL, Krishen A, Fava M. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue in major depressive disorder: a comparison of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1350–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309(7):706–716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerwyn M, Maes M. Mechanisms explaining muscle fatigue and muscle pain in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): a review of recent findings. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0628-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutherford G, Manning P, Newton JL. Understanding muscle dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Aging Res. 2016;2016:2497348. doi: 10.1155/2016/2497348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumpton JE, Moulin DE. Fibromyalgia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:513–527. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4086-3.00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browning R, Jackson JL, O'Malley PG. Cyclobenzaprine and back pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(13):1613–1620. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sim J, Adams N. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of nonpharmacological interventions for fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(5):324–336. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):745–764. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, Potts L, Walwyn R, DeCesare JC, Baber HL, Burgess M, Clark LV, Cox DL, et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):823–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deale A, Chalder T, Marks I, Wessely S. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(3):408–414. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gotaas ME, Stiles TC, Bjorngaard JH, Borchgrevink PC, Fors EA. Cognitive behavioral therapy improves physical function and fatigue in mild and moderate chronic fatigue syndrome: a consecutive randomized controlled trial of standard and short interventions. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:580924. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.580924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCrone P, Sharpe M, Chalder T, Knapp M, Johnson AL, Goldsmith KA, White PD. Adaptive pacing, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e40808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jason LA, King CP, Frankenberry EL, Jordan KM, Tryon WW, Rademaker F, Huang CF. Chronic fatigue syndrome: assessing symptoms and activity level. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55(4):411–424. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199904)55:4<411::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson K, Shapiro C. Development and validation of the nonrestorative sleep scale (NRSS) J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(9):929–937. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durmer JS, Dinges DF. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol. 2005;25(1):117–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-867080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeves WC, Heim C, Maloney EM, Youngblood LS, Unger ER, Decker MJ, Jones JF, Rye DB. Sleep characteristics of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome and non-fatigued controls: results from a population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2006;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mariman AN, Vogelaers DP, Tobback E, Delesie LM, Hanoulle IP, Pevernagie DA. Sleep in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(3):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fluge O, Tronstad KJ, Mella O. Pathomechanisms and possible interventions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) J Clin Invest. 2021;131(14):e150377. doi: 10.1172/JCI150377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fluge O, Risa K, Lunde S, Alme K, Rekeland IG, Sapkota D, Kristoffersen EK, Sorland K, Bruland O, Dahl O, et al. B-Lymphocyte depletion in myalgic encephalopathy/ chronic fatigue syndrome. An open-label phase ii study with rituximab maintenance treatment. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0129898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell WM. Efficacy of rintatolimod in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(6):755–770. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2016.1172960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maes M, Twisk FN, Kubera M, Ringel K. Evidence for inflammation and activation of cell-mediated immunity in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): increased interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, PMN-elastase, lysozyme and neopterin. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campagnolo N, Johnston S, Collatz A, Staines D, Marshall-Gradisnik S. Dietary and nutrition interventions for the therapeutic treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(3):247–259. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crosby LD, Kalanidhi S, Bonilla A, Subramanian A, Ballon JS, Bonilla H. Off label use of Aripiprazole shows promise as a treatment for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a retrospective study of 101 patients treated with a low dose of Aripiprazole. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02721-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Windthorst P, Mazurak N, Kuske M, Hipp A, Giel KE, Enck P, Niess A, Zipfel S, Teufel M. Heart rate variability biofeedback therapy and graded exercise training in management of chronic fatigue syndrome: an exploratory pilot study. J Psychosom Res. 2017;93:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsieh CY, Su CC, Shao SC, Sung SF, Lin SJ, Kao Yang YH, Lai EC. Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349–358. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S196293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study is from the National Health Insurance Research database (NHIRD). Interested researchers can obtain the data through formal application to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.