Abstract

Background

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a type of communicating hydrocephalus also known as non‐obstructive hydrocephalus. This type of hydrocephalus is caused by impaired cerebrospinal fluid reabsorption without any obstruction in the ventricular system and is associated with normal cerebrospinal fluid pressure. It is characterised clinically by gait disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and urinary incontinence (known as the Hakim‐Adams triad). The exact cause of iNPH is unknown. It may be managed conservatively or treated surgically by inserting a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt. However, a substantial number of patients do not respond well to surgical treatment, complication rates are high and there is often a need for further surgery. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is an alternative surgical intervention. It has been suggested that ETV may lead to better outcomes, including fewer complications.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of ETV for treatment of patients with iNPH compared to conservative therapy, or shunting of CSF using VP or VA shunts.

To assess the perioperative and postoperative complication rates in patients with iNPH after ETV compared to conservative therapy, VP or VA shunting.

Search methods

We searched for eligible studies using ALOIS: a comprehensive register of dementia studies, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and several bibliographic databases such as MEDLINE (Ovid SP), EMBASE (Ovid SP), PsycINFO (Ovid SP), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) and LILACS (BIREME).

We also searched the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) to identify potentially relevant reviews. The search strategy was adapted for other databases, using the most appropriate controlled vocabulary for each. We did not apply any language or time restrictions. The searches were performed in August 2014.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of ETV treatment of iNPH. Patients had to have at least two symptoms of the Hakim‐Adams triad. Exclusion criteria were obstructive causes of hydrocephalus, other significant intracranial pathology and other confirmed causes of dementia. The eligible comparators were conservative treatment or shunting using VP and VA shunts.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened search results, selected eligible studies, assessed risk of bias and extracted data. We contacted trial authors for additional data.

Main results

Only one study met the inclusion criteria: an RCT comparing effectiveness of ETV and non‐programmable VP shunts in 42 patients with iNPH. The study was conducted in Brazil between 2009 and 2012. The overall study risk of bias was high. The primary outcome in the study was the proportion of patients with improved symptoms one year after surgery, determined as a change of at least two points on the Japanese NPH scale. Due to imprecision in the results, it was not possible to determine whether there was any difference between groups in the proportion of patients who improved 3 or 12 months after surgery (3 months: odds ration (OR) 1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26 to 4.76, n = 42; 12 months: OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.62 to 10.11, n = 38). We were unable to estimate the effect of treatment on other efficacy outcomes (cognition, balance, function, gait and mobility) because they were inadequately reported. Of the 26 patients in the VP shunting group, 5 developed subdural hematoma postoperatively, while there were no complications among the 16 patients in the ETV group (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.3, n = 42), but the estimate was too imprecise to determine whether this was likely to reflect a true difference in complication rates. This was also the case for rates of further surgical intervention (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.31 to 6.24, n = 42). There were no deaths during the trial. We judged the quality of evidence for all outcomes to be very low because of a high risk of selection, attrition and reporting bias and serious imprecision in the results.

Authors' conclusions

The only randomised trial of ETV for iNPH compares it to an intervention which is not a standard practice (VP shunting using a non‐programmable valve). The evidence from this study is inconclusive and of very low quality. Clinicians should be aware of the limitations of the evidence. There is a need for more robust research on this topic to be able to determine the effectiveness of ETV in patients with iNPH.

Plain language summary

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy for idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus

Background

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the fluid which circulates around the brain and spinal cord and through spaces called ventricles within the brain. It protects the brain, supplies nutrients and removes waste products. Normally, its production and reabsorption are tightly controlled. In idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), there is an increase in the volume of CSF for unknown reasons. This causes the ventricles to enlarge and eventually leads to damage to surrounding brain tissue. It usually occurs in older people. Its characteristic symptoms are deterioration in balance and gait, urinary incontinence and cognitive decline. It is one of the less common causes of dementia.

It is thought that the symptoms of some patients with iNPH can be improved by an operation to drain away the excess CSF. This has usually been done by inserting a tube (a shunt) to drain fluid into the chest or abdomen (ventriculoatrial or ventriculoperitoneal shunts). However, there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of this approach and a significant number of patients develop complications or need further surgery. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is a newer and less invasive surgical approach which involves making a small hole in the floor of one of the ventricles.

Review question

We undertook this review to try to determine how safe and effective ETV is for treating iNPH. We did this by looking for any randomised, controlled trials (RCTs) which compared ETV to no surgery or to insertion of a shunt.

Results

We searched for trials which had been reported by August 2014. We were able to include only one RCT with 42 participants in the review. It compared ETV to insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, but unfortunately a type of shunt which is not often used in standard practice. We compared the numbers of patients whose symptoms improved with each treatment, but the result was too imprecise to allow us to draw a conclusion. In the shunting group, 19% of the patients had a surgical complication, while there were no complications in the ETV group. Due to the small number of participants, we could not be sure whether this was likely to reflect a true difference in complication rates.

Quality of the evidence

We considered the quality of the evidence to be very low because there was a high risk of bias in the trial results, because the results were so imprecise, and because several outcomes measured in the trial were not fully reported.

Conclusions

Doctors and patients should be aware of the limitations of the evidence on the effectiveness and safety of this operation for iNPH. There should be more and larger trials to compare the different treatment options.

Background

Description of the condition

Definition

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) is a clinical syndrome of older people (> 60 years) (McGirt 2005). It is coded G91.2 by ICD‐10 (i.e. the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, the World Health Organization medical classification. iNPH is characterised by the triad of gait impairment (apraxia), cognitive decline and urinary incontinence (i.e. Hakim‐Adams triad). For unknown reasons it is associated with ventricular enlargement in the absence of elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure (Marmarou 2005a). The enlargement of ventricles is characteristically triventricular in nature and the hydrocephalus is of the communicating type.

The term normal pressure (or normotensive) hydrocephalus (NPH) was devised by Hakim and Adams et al. in 1965 (Marmarou 2005a). There are two types of NPH: primary or idiopathic (iNPH) of unknown origin and secondary NPH due to subarachnoid haemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, cerebral infarction, brain tumours, brain surgery and meningitis (McGirt 2005). According to data from case‐series, substantial improvement after shunting occurs in 50% to 70% of patients with secondary NPH and 30% to 50% of patients with iNPH (Black 1985; Vanneste 1992; Vanneste 1994). iNPH is considered one of the few treatable causes of dementia (Bradley 2000; Marmarou 2007). If treated on time, iNPH symptoms may be to some extent reverted (Meier 1999).

iNPH has been neurosurgically treated since the 1960s. Considerable experience and knowledge of pathophysiology, biomarkers, neuroimaging and surgical treatment of iNPH have been accumulated over this time (Hebb 2001). Currently, standard surgical treatment of iNPH involves shunting of CSF using ventriculoperitoneal (VP) or ventriculoatrial (VA) shunts. Traditionally the diagnosis of NPH could only be confirmed postoperatively by a favourable outcome to surgical diversion of CSF.

Clinical description

The complete triad is seen in 50% to 75% of patients, with gait and cognitive disturbances occurring in 80% to 95%, and urinary incontinence in 50% to 75% of patients (Larsson 1995).

The gait abnormality in iNPH is a frontal gait disorder. Patients complain about imbalance, tiredness of legs, leg weakness, and, as the disease progresses, shorter steps, shuffling, scuffing and slow turning. A hypokinetic gait, associated with a wide base, decreased step height and disturbance of dynamic equilibrium is considered 'characteristic' for iNPH (Stoltze 2001). Gait apraxia is often the first symptom that can be observed and also the first one to resolve postoperatively (Bradley 2000; Corkill 1999; Damasceno 2009; Estanol 1981; Nutt 1993). The onset of gait abnormality before cognitive decline has been reported to predict a better prognosis after shunting (Fisher 1982; Graff‐Radford 1986).

The dementia of iNPH is of subcortical type (Gustafson 1978; Thomsen 1986) and is characterised by inertia, forgetfulness and poor executive function (Corkill 1999).

Urinary incontinence usually manifests after gait and cognitive disorder. Initially urinary urgency and frequency may be present, due to detrusor overactivity.

NPH is often misdiagnosed as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease (and other forms of dementia) and senility owing to its chronic nature and its presenting symptoms.

As well as clinical history and physical exam, the diagnostic procedure includes brain imaging.

Useful brain imaging modalities for diagnosis are computerised tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

Imaging studies of the brain are insufficient on their own to diagnose iNPH. However, to establish a diagnosis of iNPH in patients with appropriate symptoms, it is necessary to establish ventricular enlargement (ventriculomegaly). On CT scans, triventricular enlargement, not attributable to cerebral atrophy or congenital disorder, is observed with an Evans' index ≥ 0.3 (Borgesen 1982; Bradley 2004; Evans 1942) and corpus callosum angle ≤ 40° (Ishii 2008; Sjaastad 1973). Evans' index is a frontal horn ratio defined as the maximal frontal horn ventricular width divided by the transverse inner diameter of the skull; it signifies ventricular enlargement if it is ≥ 0.3 (Gallia 2005). The corpus callosum angle is another measure used on CT scans to help establish diagnosis of patients with iNPH. This angle should be < 90° in patients with iNPH (Gallia 2005).

MRI demonstrates an aqueductal flow void and white matter hyperintensities in patients with iNPH (Bradley 1991). In spite of many diagnostic and measurement tests used, there is no gold standard for assessing likely success rates for shunt treatment in iNPH (Klinge 2005). Aqueductal stroke volume above 42 µl is associated with a favourable outcome after shunting (Bradley 1996). A lack of white matter lesions on MRI, B‐waves longer than 50% of intracranial pressure monitoring time and resistance to CSF outflow > 18 mmHg are considered to predict a good response to operation. A poor response to operation is predicted by severe dementia, dementia as a presenting symptom, MRI abnormalities, cerebral atrophy and multiple white matter lesions. Misdiagnosis and delayed recognition may contribute to poor treatment outcome in iNPH (Relkin 2005). 'Mixing' of iNPH patients with those with NPH of known cause may delay appropriate diagnosis and management of NPH patients (Marmarou 2005a).

Epidemiology

Approximately 6% of all cases of dementia are caused by NPH (Adams 1981; Meyer 1984; Mullrow 1987). The number of patients with iNPH is increasing, most likely because of increased longevity (it is an illness of older people) (Marmarou 2005a; Marmarou 2005b).

One Norwegian study and two Japanese studies found an incidence of 1.8 to 5.5 per 100,000/year and a prevalence of about 22 per 100,000 (Brean 2008; Hiraoka 2008; Tanaka 2009).

Pathophysiology

Many pathophysiologic abnormalities that may lead to ventricular enlargement have been reported to occur in iNPH. These include hyperdynamic aqueduct CSF flow (Bradley 1996), reduced compliance of the subarachnoid space (Bateman 2000; Bateman 2003), elevated CSF pulse pressure (six to eight times higher than normal) (Stephensen 2002), impaired (increased resistance to) reabsorption of CSF in the venous system (Borgesen 1982), abnormal site of CSF reabsorption (transependymal rather than through Pacchionian granulations) (Edwards 2004; Oi 2006), and cerebral blood flow reduction (Owler 2001). The precise pathophysiologic pathway remains unclear (McGirt 2005).

The gait symptoms have been ascribed to the increased intracranial pressure, with presumed secondary stretching and compression of the fibres of the corticospinal tract in the corona radiata that supply the legs and that pass in the close vicinity to the lateral ventricles. As the ventricles continue to enlarge and the cortex is pushed against the inner table of the calvarium, radial shearing forces lead to dementia (Hakim 1976). There is an increased incidence of subcortical, deep white matter hyperintensities on T2‐weighted MRI images (Bradley 1991; Jack 1987; Kraus 1996, Kraus 1997). These changes probably represent small vessel ischaemia, supported by the finding of decreased cerebral blood flow (Bradley 1991; Kristensen 1996; Mamo 1987; Tanaka 1997; Waldemar 1993). At an early stage the periventricular sacral fibres of the corticospinal tract are stretched causing a loss of voluntary (supraspinal) control of bladder contractions (Gleason 1993); in later stages of the disease, the dementia may contribute to incontinence (Corkill 1999).

Description of the intervention

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is a surgical procedure in which an opening is created in the floor of the third ventricle. The standard procedure involves insertion of a flexible or rigid endoscope through a right precoronal burr hole and a small corticotomy. Perforation of the floor of the third ventricle (using a coagulation probe) is performed to the mamillary bodies and the tuber cinereum enabling pulsations of the floor of the third ventricle.

ETV is a minimally invasive surgery that has been used routinely since 1993, mainly for the treatment of obstructive hydrocephalus and intracranial CSF cysts (Gangemi 2004). In 1999, Mitchell and Mathew were first to report the use of ETV for treating iNPH in a series of four patients (Gangemi 2004; Hailong 2008; Mitchell 1999). The largest reported series of ETV in iNPH with a long follow‐up period (2 to12 years; median, 6.5 years) by Gangemi 2008 showed that both ETV and shunting have a similar mechanism. However, ETV seems to be more physiologic than shunting, which can often cause significant overdrainage and lead to shunt dependence.

Postoperative complications include intracerebral haematoma of the right frontal region, subdural haematoma, CSF leak and wound infections (Gangemi 2008).

How the intervention might work

The exact cause of iNPH is yet to be determined (McGirt 2005). There are several theories regarding the origin of this condition such as an extraventricular intracisternal CSF pathway obstruction, increased transmantle pressure gradient, a transmantle pulsatile stress or a combination of these. If iNPH is a consequence of CSF pathway obstruction, ETV could then potentially act as an internal shunt by reabsorbing CSF in the dural venous system and bypassing the aqueduct and the CSF pathways of the posterior fossa (Kehler 2003). However, in a series of iNPH patients examined neuroendoscopically, an absence of CSF pathway obstruction was observed in most cases and stated as the reason for failure of subsequent ETV treatment (Longatti 2004). However, if we accept the theory that the increased transmantle pressure gradient or a transmantle pulsatile stress, or both (from inside toward the subarachnoid space) lead to iNPH, ETV could work as an opening in the bottom of the third ventricle enabling greater systolic CSF outflow into the subarachnoid space, reducing the intraventricular pulse pressure and thus the size of the ventricles (Gangemi 2008).

Why is it important to do this review

Currently, common methods of treatment for patients with iNPH are conservative therapy (i.e. no surgical intervention, management of symptoms) or shunting of CSF using VP or VA shunts (Bergsneider 2005; Krauss 2004). However, substantial numbers of patients do not respond to shunting (Bergsneider 2005; Hebb 2001). Considering high complication rates and a frequent need for further surgery, it is evident that shunting has limitations (Meier 2000). Furthermore, a Cochrane review published in 2009 found no evidence of effectiveness of shunting for NPH (Esmonde 2009).

Although a success rate of 73.4% for treating iNPH with ETV has been reported (Gangemi 2008), there is no clear evidence about comparative effectiveness for ETV, and VP and VA shunting. That is, there is so far no clear evidence about whether ETV has any advantages over shunting procedures and whether it should be preferred in the treatment of iNPH (Meier 2003). This systematic review aims to summarise the evidence to date and will be updated to include new evidence as it accumulates.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of ETV for treatment of patients with iNPH compared to either conservative therapy or shunting of CSF using VP or VA shunts.

To assess the perioperative and postoperative complication rates in patients with iNPH after ETV compared to conservative therapy, VP or VA shunting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of ETV treatment of iNPH.

Types of participants

We considered eligible studies on patients with iNPH. Patients had to have two symptoms of an Adams–Hakim triad: gait apraxia, dementia, urinary incontinence (using either Kiefer or Japanese Committee for Scientific Research on Intractable Hydrocephalus grading systems) (Ishikawa 2008; Kiefer 2003). Other diagnostic criteria such as dilatation of all four ventricles, resistance to CSF outflow > 18 mmHg, B waves during preoperative intracranial pressure recording, good responses to spinal tap/lumbar drainage and aqueductal stroke volume of 42 µl were not used as inclusion criteria since they are not routinely performed in patients with iNPH. However, we report them in our review as they could be a source of heterogeneity.

Exclusion criteria were obstructive causes for hydrocephalus, other significant intracranial pathology and other confirmed causes of dementia.

Types of interventions

ETV for treatment of patients with iNPH. The eligible comparators were conservative treatment or shunting using VP and VA shunts.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Postoperative change in clinical signs and symptoms of iNPH measured using validated assessment tools. These were divided into:

short‐term outcomes (up to and including six months);

long‐term outcomes (measured more than six months postoperatively);

Postoperative complications, perioperative mortality and morbidity rates.

Secondary outcomes

Long‐term complications (infection, CSF fistula, overdrainage).

A need for further surgical treatment.

Ventricle width in the postoperative period.

Changes in measurements of diagnostic tests (e.g. MRI, CT).

Total mortality over a trial.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search strategy was developed and performed by the The Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group trial search coordinator. The following electronic databases were searched for eligible studies:

ALOIS: a comprehensive register of dementia studies. ALOIS is the specialised register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group that contains records of controlled trials identified from monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases, trials registers and grey literature sources. For a full list of sources searched for ALOIS, see About ALOIS at the following link ‐ http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois/content/about‐alois ;

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 7);

Bibliographic databases: MEDLINE (Ovid SP), EMBASE (Ovid SP), PsycINFO (Ovid SP), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), LILACS (BIREME).

The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 7) was also searched to identify potentially relevant reviews.

We used the strategy outlined in Appendix 1 to search MEDLINE which was adapted for other databases, using the most appropriate controlled vocabulary for each. We did not apply any language restrictions.The search was conducted in August 2014 without any time limits.

Searching other resources

For the included study, we conducted author and citation searches in Science Citation Index database.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MT and KIT) independently examined titles and abstracts of citations obtained from the searches and excluded obviously ineligible articles. We then obtained the full‐text report for only one study which met the inclusion criteria. We independently assessed the retrieved paper for inclusion in the review using pre‐defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MT and KIT) independently retrieved information on the study design, participants, and intervention outcomes and results from the study using a standardised data extraction form. We resolved any potential disagreements about the extracted data by discussion. We contacted authors for missing information on study outcomes.

For each outcome measure, we searched for available data on every randomised patient. We planned to perform an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis of available data. However, the information available in the only eligible study found, did not allow this approach. This is because five participants initially randomised to the ETV group were reassigned to, and analysed as, a part of the VP shunting group.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MT and KIT) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study, using the 'Risk of bias' tool from Chapter 8.5 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2011), with any differences resolved by discussion and consensus. The tool includes the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias.

We analysed the included study and assigned a judgment relating to the risk of bias for each item. We used a template to guide the assessment of risk of bias judging each item as 'yes' (indicating a low risk of bias), 'no' (indicating a high risk of bias) or 'unclear' (indicating an uncertain risk of bias). We summarised the risk of bias for each outcome.

We also assessed a range of other possible sources of bias and indicators of study quality, including: baseline comparability of groups, validation of outcome assessment tools and reliability of outcome measures.

We presented the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment in a table and incorporated the results of the assessment of risk of bias into the review through systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the quality items, for the included study. We were unable to make to make an overall assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies and a judgment about the possible effects of bias on the effect sizes of the included studies as initially intended as we only found one eligible study.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes, such as clinical improvement or no clinical improvement, we presented the outcomes using odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous outcomes, we planned to report the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

We followed Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Intervention recommendations (Deeks 2011) to resolve potential unit of analysis issues. Repeated measurements (i.e. outcomes assessed at different time points within the same trial) were analysed separately as short‐term (assessed up to six months post‐intervention) and long‐term (more than six months post‐intervention) outcomes.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to include studies published in any language to address the language bias. In order to minimise the risk of publication bias, we performed a comprehensive search in multiple databases (including unpublished results)

Data synthesis

Although we planned to assess all studies qualitatively and subsequently, if appropriate, perform a meta‐analysis (using a random‐effects model), this was unfeasible as only one study was included.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In terms of the subgroup analyses, our aim was, if collected data allowed, to perform subgroup analyses according to age, co‐morbidities, gender and duration of symptoms. We planned to examine protocols for the selection of iNPH patients for ETV used in the analysed studies and form subgroups of patients, depending on additional diagnostic tests used to confirm the diagnosis, and then perform subgroup analysis. Given that we only included one eligible study, the planned subgroup analyses were unfeasible.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses based on the 'Risk of bias' assessment of the included studies and if possible remove studies with the highest risk of bias from the analysis. However, this was unfeasible as only one study was included.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

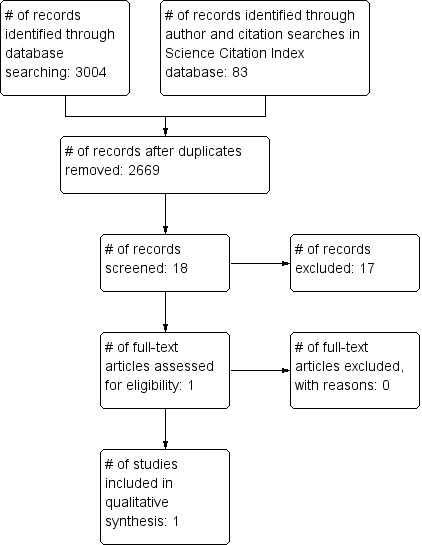

The search strategy yielded 3004 potentially relevant references. The number of records that remained after duplicates were removed was 2669. Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in only one paper retrieved in full text which was in the end included (Pinto 2013). Author Science Citation Index database search yielded 78 citations which were deemed ineligible. Citation Science Citation Index database search resulted in five studies which did not fit our inclusion criteria. We did not find any relevant conference proceedings or on‐going trials. Figure 1 shows the search process and study selection with the adapted PRISMA flow‐diagram.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We found only one eligible study (Pinto 2013). Key characteristics of the included study are summarised in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. This study was an RCT, in which the unit of randomisation was the individual patient. The study was conducted from January 2009 to January 2012 on patients with iNPH at the Institute of Psychiatry, Hospital das Clinicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. The objective of the study was to compare functional neurological outcome in patients with iNPH 12 months after treatment with either ETV or VP shunting. The sample size was 42. The authors' hypothesis was that iNPH treatment with VP shunting is the superior option compared to ETV.

The study participants included 24 men and 18 women, aged from 60 to 75 years. All participants had a diagnosis of probable iNPH. The diagnostic criteria for probable iNPH consisted primarily of clinical criteria, as well as radiological and manometric criteria. Further inclusion criteria were the duration of symptoms for 24 months, preserved ambulation with 2 supports, absence of other dementia syndromes, absence of malignant disease, compensated clinical co‐morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hormonal disorders), positive result of the tap test (TT) (Wikkelsø 2013), and free and informed consent signed by patients and family members. The TT is a common prognostic test used to select patients for shunt surgery (Marmarou 2005b). In this study, the TT was performed preoperatively to determine the CSF pressure and therapeutic prognosis by withdrawing 40 ml of CSF.

ETV was performed via a right precoronal burr hole (Kocher point) with a rigid ventricular neuroendoscope containing a 30 lens (Minop, Aesculap). The the floor of the third ventricle was perforated in the midline halfway between the mammillary bodies and the infundibular recess. An inflating balloon of a 4F Fogarty catheter was used to enlarge the fenestration. The ventriculostomy size was approximately 4 mm to 6 mm.

VP shunting was performed via a right precoronal burr hole (Kocher point). The chosen valve pressure (PS Medical, Medtronic) was based on the final manometry value at the TT. After the removal of 40 ml of CSF, a low‐pressure valve was inserted with the final pressure of 4 cm H2O; a final pressure between 4 cm and 10 cm H2O resulted in the administration of a medium‐pressure valve; and a final pressure of 10 cm H2O resulted in the administration of a high‐pressure valve.

Outcomes were measured with the following validated scales before and after surgery: the NPH Japanese Scale (NPH Scale) (Mori 2001), the Berg Balance Scale (BERG) (Berg 1992;Miyamoto 2004), the Dynamic Gait Index (DGI) (Marchetti 2006), the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (Linacre 1994), the Mini‐Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (Folstein 1975), and the Timed Up and Go (TUG) (Schoene 2013). All patients were followed for 12 months, with prescheduled consultations at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. The patients were evaluated according to the scales at 3 and 12 months. The primary outcome measure in this study was the proportion of patients showing improvement of symptoms after one year using the NPH scale. The authors state that “after 1 year, the late postoperative result was classified as positive if the patient had at least a 2 points higher score on the NPH Scale”, although higher scores on this scale actually indicate poorer outcomes. No definition is given for a positive outcome after three months. The outcomes measured using other scales were considered secondary outcomes. Surgical complications were presented for both groups of patients.

Excluded studies

The only study for which we retrieved the full text was included in the review. We therefore do not present any excluded studies, as no study was excluded at the full‐text screening stage.

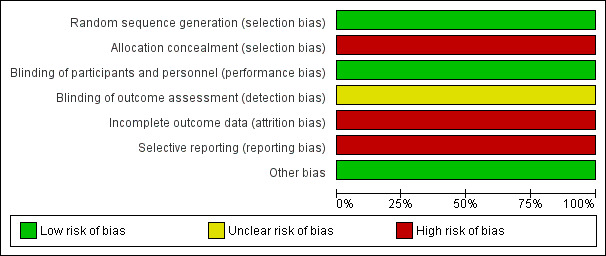

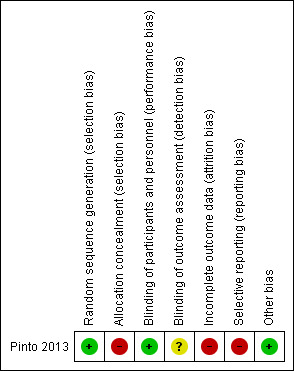

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged the included RCT to have a high risk of bias. The 'Characteristics of included studies' table, Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the relevant information.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We judged that the methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment in the included RCT were adequate: a random choice of opaque white sealed envelopes containing the name of one of the two procedures by an independent physician from the surgical ward. However, five participants who had been randomly assigned to ETV were actually treated with VP shunting because at the time of surgery the surgeon judged them to be unsuitable for ETV due to anatomical variations. These participants were analysed in the VP shunting group. Hence, we judged there to be an overall high risk of selection bias. Blinding of the participants and personnel in the study was not possible. We believe this did not influence outcome and therefore the risk of performance bias was judged to be low. The risk of detection bias was judged to be unclear since we could not find any information in the study about the blinding of the outcome assessors. We judged the study to have a high risk of attrition bias as 4 patients in the ETV group who were judged unimproved after 3 months were treated with VP shunting and excluded from the primary outcome analysis at 12 months. We judged the study to have a high risk of reporting bias since no continuous outcomes were reported in sufficient detail to allow calculation of mean differences (only average, maximum and minimum presented in a table) and the study authors have not responded to a request to provide the standard deviations.

Effects of interventions

Short‐term (<6 months after surgery) and long‐term (> 6 months after surgery) postoperative change in clinical signs and symptoms of iNPH

The study authors report that 12 of the 16 patients in the ETV group and 20 of the 26 patients in the VP shunting group showed clinical improvement after 3 months, but it is not clear how improvement at this time point was defined. We did use these figures to calculate an odds ratio, but due to the small sample size, the effect estimate was very imprecise and it was not possible to determine whether there was any difference between groups (OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.26 to 4.76, n = 42, 1 study). We judged this evidence to be of very low quality due to very serious imprecision and serious risk of bias.

At 12 months, 4 patients from the ETV group who had not improved at 3 months had been treated with VP shunting and were excluded from the analysis. The study authors reported that 8 of the 12 remaining patients in the ETV group and 20 of the 26 patients in the VP shunting group showed clinical improvement. This had been defined as an increase of at least 2 points on the NPH scale, but we assumed that the authors meant a decrease of at least 2 points (lower scores on this scale indicating better outcome). Again, it was not possible to determine any difference between the groups (OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.62 to 10.11, n = 38, 1 study). We judged this to be very low quality evidence due to very serious imprecision and very serious risk of bias.

Other efficacy outcomes (cognition, balance, function, gait and mobility) were measured at 3 and 12 months, but the results were reported only as “average” and range. No standard deviations were reported and the authors have not responded to our request for additional data. Hence, we were not able to calculate mean differences between the groups with confidence intervals for any of these outcomes.

Postoperative complications and long‐term complications (infection, CSF fistula, overdrainage)

There were no postoperative complications in the ETV group. In the VP group, 5 of the 26 patients (19%) who underwent implantation of a low‐pressure valve had overdrainage with a significant reduction in ventricular size and a chronic subdural haematoma. Due to imprecision of the effect estimate, it was not possible to determine whether the interventions differed in the rate of post‐operative complications (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.3, n= 42, 1 study). We judged this to be very low quality evidence due to very serious imprecision and very serious risk of bias.

A need for further surgical treatment

Four of the 16 patients (25%) receiving ETV who showed no improvement at three months post surgery were submitted to VP shunting. In the VP shunting group, 5 of the 26 patients (19%) experienced overdrainage and underwent another operation with implantation of a medium‐pressure valve. Again, the effect estimate was very imprecise and it was not possible to determine whether there was a difference between the interventions in the need for further surgical treatment (OR 1.4, 95% CI 0.31 to 6.24, n = 42 , 1 study). We judged this to be very low quality evidence due to very serious imprecision and very serious risk of bias.

Ventricle width in the postoperative period and changes in measurements of diagnostic tests (e.g. MRI, CT)

Ventricular size on CT scan was measured preoperatively and six months postoperatively, but data were given only as means and ranges.

Total mortality

No patients died during the study.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The only included study provides no evidence that either ETV or VP shunting is associated with better outcomes for patients with iNPH (Pinto 2013). Many outcomes were inadequately reported and, where we were able to calculate effect estimates with confidence intervals, these were extremely imprecise. The results were compatible with no difference or with superiority of either intervention. While none of the 16 ETV patients had complications, 5 of the 26 patients submitted to VP shunting developed overdrainage and chronic subdural haematoma, but the sample size was too small to draw any definitive conclusion from this.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In this review, we performed a thorough search of the available literature on the effectiveness of ETV compared to all other currently employed types of treatment. Nevertheless, we only found one eligible trial that assessed the effectiveness of ETV compared to VP shunting. This trial had serious limitations. The included evidence does not provide robust and generalisable answers to the review questions.

The included study was performed in Brazil and included elderly patients with the diagnosis of probable iNPH, with 1 to 2 symptoms, duration of symptoms of 24 months, preserved ambulation with 2 supports, absence of other dementia syndromes and malignant disease, compensated clinical co‐morbidities, positive TT result, and free and informed consent signed by patients and family members. The sample size was small. Five patients were re‐allocated post‐randomisation from ETV to VP shunting group. The comparator used was non‐programmable VP shunts which are no longer a standard treatment for people with iNPH. The presented data on continuous outcomes lack relevant summary measures to allow statistical analysis and comparison.

Quality of the evidence

The study had 42 participants and was judged to have a high risk of bias. Using GRADE criteria, we judged the evidence to be of very low quality (Schünemann 2011). The evidence presented in this review has serious limitations relating both to the risk of bias (high risk of selection, attrition and reporting bias) and to imprecision in the effect estimates (inclusion of only one small study).

Potential biases in the review process

We rigorously followed the Cochrane review methodology and performed a comprehensive search without any limitations. In our opinion, it is unlikely that we missed any other relevant study, either published, from grey literature or on‐going.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

An Italian multicenter retrospective study published in 2008 reported outcomes of the ETV treatment. This study reported a success rate of 69.1% for ETV treatment in 110 patients with iNPH after a follow‐up period of at least 2 years. The study had several limitations such as a lack of a clear distinction between the cases of iNPH and possible cases of secondary NPH, and the use of the monitoring of intracranial pressure as a predictive functional test rather than the TT, the lumbar infusion test, and external lumbar drainage monitoring for 72 hours (Gangemi 2008). Another case series presented 14 cases with apparently idiopathic NPH treated by ETV and reported a low rate of success (21%) (Longatti 2004). A study on perioperative safety of ETV for iNPH compared with VP shunting that used a nationwide database reported that ETV was associated with higher perioperative mortality and complication rates compared with VP shunting. In this review, the only eligible study we found had no complications (either short‐ or long‐term) associated with ETV (Chan 2013).

The findings from these three studies are diverse and different to the outcomes reported in the RCT included in this review. There is a clear need for larger, methodologically robust RCTs to provide reliable evidence on the effectiveness of ETV in patients with iNPH.

Authors' conclusions

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence we found was inconclusive for all outcomes and of very low quality. When choosing a surgical intervention for iNPH, clinicians should be aware of the limitations of the evidence base.

Implications for research.

There is a lack of evidence on the effectiveness of ETV in patients with iNPH. The only eligible study we found had a high risk of bias, a small sample size and used VP shunts with non‐programmable valves. There is a need for larger randomised controlled trials comparing ETV with the currently recommended treatment ‐ VP shunting with a programmable valve. The authors of the included study reported that oscillations of the third ventricle floor observed intra‐operatively were associated with improvement in the ETV group. Future trials should consider following up this observation by undertaking relevant subgroup analyses.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Ms Anna Noel‐Storr for developing the search strategy and running the searches and to Ms Sue Marcus and the Cochrane Dementia Review Group for their help, patience and guidance with this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (Ovid SP) search strategy

1. "idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus".ti,ab. 2. Hydrocephalus, Normal Pressure/ 3. (wet ADJ wobbly ADJ wacky".ti,ab. 4. "weird ADJ walking ADJ water".ti,ab. 5. "normotensive hydrocephalus".ti,ab. 6. (NPH or iNPH or sNPH).ti,ab. 7. dement*.ti,ab. 8. Dementia/ 9. or/1‐8 10. Ventriculostomy/ 11. ventriculostomy.ti,ab. 12. Cerebrospinal Fluid Shunts/ 13. ("cerebrospinal fluid shunt*" or "CSF shunt*").ti,ab. 14. Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt/ 15. "ventriculoperitoneal shunt*".ti,ab. 16. ETV.ti,ab. 17. or/10‐16 18. 9 and 17

Appendix 2. Glossary

Arachnoid mater: one of the three meninges, the protective membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord, located between the two other meninges ‐ the more superficial and much thicker dura mater and the deeper pia mater, from which it is separated by the subarachnoid space.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): is the fluid which circulates around the brain and spinal cord and through spaces called ventricles within the brain. It protects the brain and the spinal cord, supplies nutrients and removes waste products.

Communicating hydrocephalus: type of hydrocephalus in which the openings between the ventricular spaces, and between the fourth ventricle and the subarachnoid space, are working.

Corpus Callosum: a broad band of nerve fibres linking the two brain hemispheres.

Coronal suture: seam between the frontal and the parietal bones.

Corticotomy: removal of a part of bone cortex while leaving the intramedullary blood supply intact

CSF shunt: a tube surgically sited in the body that channels cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain or spinal cord into another part of the body, where it can be absorbed and transported to the bloodstream.

Dura mater: the top layer of the meninges underneath the bone tissue.

Dural venous sinuses: venous channels found between layers of dura mater in the brain. They receive blood from internal and external veins of the brain, receive cerebrospinal fluid and finally empty into the internal jugular vein.

Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV): a surgical operation that forms an opening through the membranous floor of the third ventricle, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to leave the third ventricle and flow directly into the subarachnoid space at the brain base.

Hakim‐Adams triad: classic symptom triad associated with iNPH‐ deterioration in balance and gait, urinary incontinence and cognitive decline

Hydrocephalus: an abnormal condition that occurs when there is an imbalance between the rate of cerebrospinal fluid production and the rate of absorption, leading to gradual accumulation of CSF.

Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH): type of adult‐onset hydrocephalus without known cause with symptoms such as difficulty walking, mild dementia, and impaired bladder control. This form of hydrocephalus occurs most often in people over age 60.

Intracranial pressure (ICP): pressure caused by a build‐up of cerebrospinal fluid, resulting in hydrocephalus.

Lateral ventricles: part of the ventricular system of the brain located in each cerebral hemisphere. The lateral ventricles are the largest of the ventricles.

Meninges: the three membranes (the dura mater, arachnoid, and pia mater) that coat the skull and vertebral canal and enfold the brain and spinal cord.

Pacchionian granulation: the arachnoid membrane projections into the dural sinuses that allow CSF entrance from the subarachnoid space to the venous system.

Pia mater: the delicate innermost membrane surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

Subarachnoid space: the anatomic space between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater, the two membranes that surround the brain and the spinal cord.

Transmantle pressure: the difference between the intraventricular pressure and the pressure inside the subarachnoid spaces of the cerebral convexity.

Third ventricle: a midline brain cavity that is located between the right and left thalamus. Cerebrospinal fluid enters the third ventricle from each lateral ventricle via the foramen of Monro; it exits the third ventricle via the aqueduct of Sylvius.

Ventricle: a cavity within the brain that contains cerebrospinal fluid.

Ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt: a shunt that is placed into a brain ventricle to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the ventricular system into the heart.

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt: a shunt that is placed into a brain ventricle to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the ventricular system into the abdomen.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Pinto 2013.

| Methods | Parallel, open‐label randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Eligble participants were patients with diagnosis of probable iNPH, aged 55 to 75 years, duration of symptoms 24 months, preserved ambulation even with 2 supports, absence of other dementia syndromes, absence of malignant disease, compensated clinical co‐morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hormonal disorders), positive TT result, and free and informed consent signed by patients and family members. A total of 42 participants were included in the study and randomised into two groups of 21 patients. However, 5 patiens from the ETV group were subsequently reallocated to VP shunting group due to anatomical characteristics which made ETV inappropriate. ETV group consisted of 16 patients with 9 men and 7 women. The mean age was 70 years, ranging from 60 to 75 years. VP shunting group consisted of the 21 patients randomly assigned to the VP shunting group and the 5 patients reallocated from ETV group. 15 were men and 11 were women. The mean age was 71 years, ranging from 62 to 73 years. |

|

| Interventions | Intervention was ETV which was performed with a rigid endoscope with a 30 lens (Minop, Aesculap). The comparison consisted of VP shunting which was performed with a fixed‐pressure valve (PS Medical, Medtronic). | |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome was improvement of neurological function one year after surgery measured as 2 points improvement on the NPH Japanese Scale. The secondary outcomes included improvement determined thorough the use of other scales (e.g. The Mini‐mental Status Examination, the Berg Balance Scale, the Dynamic Gait Index, the Functional Independence Measure, the Timed Up and Go) and surgical complications. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The allocation sequence was adequately generated. The authors state: "An independent physician from the surgical ward of the hospital randomly chose between 2 equally sized and opaque white sealed envelopes that were placed side to side over a table. Each envelope contained a white sheet of paper with the name of a procedure on it (either VPS or ETV), thus choosing the intervention to be performed." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | The allocation of participants in the study was adequately concealed. As above, authors state: "the surgical ward of the hospital randomly chose between 2 equally sized and opaque white sealed envelopes that were placed side to side over a table. Each envelope contained a white sheet of paper with the name of a procedure on it (either VPS or ETV), thus choosing the intervention to be performed." However, 5 participants who had been randomly assigned to ETV were actually treated with VTP due to anatomical variations found at surgery and were analysed in the VT shunting group. Hence, we judged there to be an overall high risk of selection bias. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The blinding of participants and personnel was unfeasible. We believe this did not influence outcome and therefore the risk of performance bias was judged to be low. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | There is no information on blinding of outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Four patients in the ETV group who were judged unimproved after three months were treated with VP shunting and excluded from the primary outcome analysis at 12 months. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No continuous outcomes were reported in sufficient detail to allow calculation of mean differences (only average, max and min presented in a table) and the study authors have not responded to a request to provide the standard deviations. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Differences between protocol and review

There are a number of differences between the protocol and the present review. These differences are mainly because only one study met the inclusion criteria and they are mostly in the data analysis section.

Data analysis If we had found more than one eligible study, we would have presented a summary of the treatment effect. Moreover, we would have analysed the outcomes using RevMan 2014, and intention‐to treat principle of analysis (Unnebrink 2001). If sufficient number of eligible studies had been available, we would have aimed to summarise data statistically. We planned to present dichotomous data as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For continuous outcomes we wanted to calculate the mean difference with 95% CI. We wanted to calculate overall results based on a random effects model. If heterogeneity had been detected and it had been appropriate to combine the trials, we would have used a random‐effects model.

Assessment of heterogeneity We felt it was important to consider heterogeneity in this review, given the fledgling nature of this field. Had we found substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity, we would not have combined the results in a meta‐analysis and would have performed a narrative overview of the findings. We planned to identify heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots, by using a standard Chi2 test and a significance level of alpha = 0.1, in view of the low power of such tests. We would also have examined heterogeneity with the I2 statistic, where I2 values of 50% or more indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We would have attempted to determine potential reasons for heterogeneity by examining individual study characteristics of the main body of evidence.

Reporting bias To test the likelihood of reporting bias in the included studies, we planned to use funnel plots. We wanted initially to test for funnel plot asymmetry by visual inspection. If we had included more than 10 studies, funnel plot asymmetry would have been tested using the test proposed by Egger 1997. If funnel plot asymmetry had been determined, we would have discussed its possible causes (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis We would have performed meta‐analysis if a group of included studies was sufficiently homogenous. We would have separately analysed the results of the different study types and for the different outcomes. If statistical pooling of results had been inappropriate, we would have undertaken a narrative overview of the results. We would have systematically described each included study according to setting, participants, control, and outcomes. We would have grouped the included studies according to duration of the study and performed separate meta‐analyses. We would have presented each included study in a “Characteristics of included studies” table and we would have provided a risk of bias assessment and quality assessment of included studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity If there had been sufficient trial data, we would have performed subgroup analyses according to age, co‐morbidities, gender and duration of symptoms. We would have examined protocols for the selection of iNPH patients for ETV used in the analysed studies and formed subgroups of patients, depending on additional diagnostic tests used to confirm the diagnosis of iNPH. These diagnostic tests (such as resistance to CSF outflow, spinal tap/lumbar drainage, etc.) have different sensitivities, as well as positive and negative predictive values and represent a potential source of heterogeneity. If we had found a sufficient number of studies employing different diagnostic modalities to confirm the diagnosis of iNPH, we would have performed subgroup analysis based on different diagnostic tests.

Sensitivity analyses We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses based on the ’Risk of bias’ assessment of the included studies.

Contributions of authors

Mario Tudor and Katarina Ivana Tudor wrote the protocol and the review. Josip Car and Jenny McCleery provided methodological and reporting guidance and performed final amendments.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

NIHR, UK.

This protocol was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health

Declarations of interest

Katarina Ivana Tudor: no conflicts of interest. Mario Tudor: no conflicts of interest. Jenny McCleery: no conflicts of interest. Josip Car: no conflicts of interest.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Pinto 2013 {published data only}

- Pinto FC, Saad F, Oliveira MF, Pereira RM, Miranda FL, Tornai JB, et al. Role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy and ventriculoperitoneal shunt in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: preliminary results of a randomized clinical trial. Neurosurgery 2013;72(5):845‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Adams 1981

- Adams RD, Victor M. Principles of Neurology. 2nd Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 1981:285‐95. [Google Scholar]

Bateman 2000

- Bateman GA. Vascular compliance in normal pressure hydrocephalus. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2000;21:1574–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bateman 2003

- Bateman GA. The reversibility of reduced cortical vein compliance in normal pressure hydrocephalus following shunt insertion. Neuroradiology 2003;45:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berg 1992

- Berg KO, Wood‐Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: validation of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health 1992;83(suppl 2):S7‐S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bergsneider 2005

- Bergsneider M, Black PM, Klinge P, Marmarou A, Relkin N. Surgical management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2005;57:29‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Black 1985

- Black PM, Ojemann RG, Tzouras A. CSF shunts for dementia, incontinence and gait disturbances. Clinical Neurosurgery 1985;32:632‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borgesen 1982

- Borgesen SE, Gjerris F. The predictive value of conductance to outflow of CSF in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain 1982;105:65–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bradley 1991

- Bradley WG, Whittemore AR, Watanabe AS, Davis SJ, Teresi LM, Homyak M. Association of deep white matter infarction with chronic communicating hydrocephalus: implications regarding the possible origin of normal pressure hydrocephalus. American Journal of Neuroradiology 1991;12:31‐9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bradley 1996

- Bradley WG, Scalzo D, Queralt J, Nitz WN, Atkinson DJ, Wong P. Normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: evaluation with cerebrospinal fluid flow measurements at MR imaging. Radiology 1996;198:523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bradley 2000

- Bradley WG. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: new concepts on etiology and diagnosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2000;21:1586‐90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bradley 2004

- Bradley WG, Safar FG, Furtado C, Ord J, Alksne JF. Increased intracranial volume: a clue to the etiology of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus?. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2004;25:1479‐84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brean 2008

- Brean A, Eide PK. Prevalence of probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2008;118(1):48‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chan 2013

- Chan AK, McGovern RA, Zacharia BE, Mikell CB, Bruce SS, Sheehy JP, Kelly KM, McKhann GM 2nd. Inferior short‐term safety profile of endoscopic third ventriculostomy compared with ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement for idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: a population‐based study. Neurosurgery 2013;73(6):951‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corkill 1999

- Corkill RG, Cadoux‐Hudson TAD. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: developments in determining surgical prognosis. Current Opinion in Neurology 1999;12:671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Damasceno 2009

- Damasceno BP. Normal pressure hydrocephalus diagnostic and predictive evaluation. Dementia & Neuropsychologia 2009;3(1):8‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2011

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors).Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Edwards 2004

- Edwards RJ, Dombrowski SM, Luciano MG, Pople IK. Chronic hydrocephalus in adults. Brain Pathology 2004;14:325‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Esmonde 2009

- Esmonde T, Cook S. Shunting for normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003157] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Estanol 1981

- Estanol BV. Gait apraxia in communicating hydrocephalus. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1981;44:305–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 1942

- Evans WA. An encephalographic ratio for estimating ventricular and cerebral atrophy. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 1942;47:931‐7. [Google Scholar]

Fisher 1982

- Fisher CM. Hydrocephalus as a cause of gait disturbances in the elderly. Neurology 1982;32:1258‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Folstein 1975

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini‐mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975;12(3):189‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallia 2005

- Gallia GL, Rigamonti D, Williams MA. The diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology 2005;2:375‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gangemi 2004

- Gangemi M, Maiuri F, Buonamassa S, Colella G, Divitiis E. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2004;55(1):129‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gangemi 2008

- Gangemi M, Maiuri F, Naddeo M, Godano U, Mascari C, Broggi G, et al. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: an Italian multicenter study. Neurosurgery 2008;63(1):62‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gleason 1993

- Gleason PL, Black PM, Matsumae M. The neurobiology of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America 1993;4:667–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graff‐Radford 1986

- Graff‐Radford NR, Godersky JC. Normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: onset of gait abnormality before dementia predicts good surgical outcome. Archive of Neurology 1986;43(9):940‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gustafson 1978

- Gustafson L, Hagberg B. Recovery in hydrocephalic dementia after shunt operation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1978;41:940–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hailong 2008

- Hailong F, Guangfu H, Haibin T, Hong P, Yong C, Weidong L, et al. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the management of communicating hydrocephalus: a preliminary study. Journal of Neurosurgery 2008;109:923‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hakim 1976

- Hakim S, Venegas JG, Burton JD. The physics of the cranial cavity, hydrocephalus and normal pressure hydrocephalus: mechanical interpretation and mathematical model. Surgical Neurology 1976;5:187‐209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hebb 2001

- Hebb AO, Cusimano MD. Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus: a systematic review of diagnosis and outcome. Neurosurgery 2001;49:1166‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors).Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hiraoka 2008

- Hiraoka K, Meguro K, Mori E. Prevalence of idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus in the elderly population of a Japanese rural community. Neurologia Medico‐chirurgica (Tokyo) 2008;48(5):197‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ishii 2008

- Ishii K, Kanda T, Harada A, Miyamoto N, Kawaguchi T, Shimada K, et al. Clinical impact of the callosal angle in the diagnosis of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. European Radiology 2008;18(11):2678‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ishikawa 2008

- Ishikawa M, Hashimoto M, Kuwana N, Mori E, Miyake H, Wachi A, et al. Management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, guidelines from the Guidelines Committee of Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, the Japanese Society of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Neurologia Medico‐chirurgica 2008;48 Supp:1‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jack 1987

- Jack CR, Mokri B, Laws ER, Houser OW, Baker HL, Petersen RC. MR findings in normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: significance and comparison with other forms of dementia. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 1987;11:923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kehler 2003

- Kehler U, Gliemroth J. Extraventricular intracisternal obstructive hydrocephalus ‐ a hypothesis to explain successful 3rd ventriculostomy in communicating hydrocephalus. Pediatric Neurosurgery 2003;38(2):98‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kiefer 2003

- Kiefer M, Eymann R, Komenda Y, Steudel WI. A grading system for chronic hydrocephalus. Zentralblatt für Neurochirurgie 2003;64(3):109‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klinge 2005

- Klinge P, Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Relkin N, Black P. Outcome of shunting in idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus and the value of outcome assessment in shunted patients. Supplement to Neurosurgery 2005;57(3):S2‐40‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kraus 1996

- Krauss JK, Droste DW, Vach W, Regel JP, Orszagh M, Borremans JJ, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid shunting in idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus of the elderly: effect of periventricular and deep white matter lesions. Neurosurgery 1996;39:292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kraus 1997

- Krauss JK, Regel JP, Vach W, Orszagh M, Jüngling FD, Bohus M, et al. White matter lesions in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus and in an age‐matched control group: a comparative study. Neurosurgery 1997;40(3):491–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krauss 2004

- Krauss JK, Halve B. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: survey on contemporary diagnostic algorithms and therapeutic decision‐making in clinical practice. Acta Neurochirurgica (Wien) 2004;146:379‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kristensen 1996

- Kristensen B, Malm J, Fagerland M, Hietala SO, Johansson B, Ekstedt J, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow, white matter abnormalities, and cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics in patients with idiopathic adult hydrocephalus syndrome. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1996;60:282‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larsson 1995

- Larsson A, Stephensen H, Wikkelsö C. Normaltryckshydrocefalus: demenstillstand som förbätttras med shuntkirurgi. Läkartidningen 1995;92:545‐50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Linacre 1994

- Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1994;75(2):127‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Longatti 2004

- Longatti PL, Fiorindi A, Martinuzzi A. Failure of endoscopic third ventriculostomy in the treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery 2004;47(6):342‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mamo 1987

- Mamo HL, Meric PC, Ponsin JC, Rey AC, Luft AG, Seylaz JA. Cerebral blood flow in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Stroke 1987;18:1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marchetti 2006

- Marchetti GF, Whitney SL. Construction and Validation of the 4‐Item Dynamic Gait Index. Physical Therapy 2006;86(12):1651‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marmarou 2005a

- Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Relkin N, Klinge P, Black PM. Development of guidelines for idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: introduction. Supplement to Neurosurgery 2005;57(3):S2‐1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marmarou 2005b

- Marmarou A, Bergsneider M, Klinge P, Relkin N, Black P. The value of supplemental prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus. Supplement to Neurosurgery 2005;57(3):S2‐17‐S2‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marmarou 2007

- Marmarou A, Young HF, Aygok GA. Estimated incidence of normal pressure hydrocephalus and shunt outcome in patients residing in assisted‐living and extended‐care facilities. Neurosurgical Focus 2007;22(4):E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGirt 2005

- McGirt MJ, Woodworth G, Coon A, Thomas G, Williams MA, Rigamonti D. Diagnosis, treatment, and analysis of long‐term outcomes in idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2005;57(4):699‐705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meier 1999

- Meier U, Zeilinger FS, Kintzel D. Signs, symptoms and course of normal pressure hydrocephalus in comparison with cerebral atrophy. Acta Neurochirurgica (Wien) 1999;141:1039‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meier 2000

- Meier U, Zeilinger FS, Schonherr B. Endoscopic ventriculostomy versus shunt operation in normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnostics and indication. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement (Wien) 2000;76:563–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meier 2003

- Meier U. Shunt operation versus endoscopic ventriculostomy in normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnostics and outcome. Zentralblatt für Neurochirurgie 2003;64:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meyer 1984

- Meyer JS, Tachibana H, Hardenberg JP, Dowell RE, Kitagawa Y, Mortel KF. Normal pressure hydrocephalus: influence on cerebral hemodynamic and cerebrospinal fluid pressure chemical autoregulation. Surgical Neurology 1984;21:195‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitchell 1999

- Mitchell P, Mathew B. Third ventriculostomy in normal pressure hydrocephalus. British Journal of Neurosurgery 1999;13:382‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miyamoto 2004

- Miyamoto ST, Lombardi Junior I, Berg KO, Ramos LR, Natour J. . Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004, 37(9):1411‐1421. Brazilianversion of the Berg balance scale. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2004;37(9):1411‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mori 2001

- Mori K. Management of idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: a multiinstitutionalstudy conducted in Japan. Journal of Neurosurgery 2001;95(6):970‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mullrow 1987

- Mulrow CD, Feussner JR, Williams BC, Vokaty KA. The value of clinical findings in the detection of normal pressure hydrocephalus. Journal of Gerontology 1987;42:277‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nutt 1993

- Nutt JG, Marsden CD, Thompson PD. Human walking and higher‐level gait disorders particularly in the elderly. Neurology 1993;43:268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oi 2006

- Oi S, Rocco C. Proposal of "evolution theory in cerebrospinal fluid dynamics" and minor pathway hydrocephalus in developing immature brain. Child's Nervous System 2006;22:662–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Owler 2001

- Owler BK, Pickard JD. Normal pressure hydrocephalus and cerebral blood flow: a review. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2001;104:325–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Relkin 2005

- Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black P. Diagnosing idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus. Supplement to Neurosurgery 2005;57(3):S2‐4‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Schoene 2013

- Schoene D, Wu SM, Mikolaizak AS, Menant JC, Smith ST, Delbaere K, Lord SR. Discriminative ability and predictive validity of the timed up and go test in identifying older people who fall: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of American Geriatric Society 2013;61(2):202‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schünemann 2011

- Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, Guyatt GH. Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Sjaastad 1973

- Sjaastad O, Nordvik A. The corpus callosal angle in the diagnosis of cerebral ventricular enlargement. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 1973;49(3):396‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stephensen 2002

- Stephensen H, Tisell M, Wikkelso C. There is no transmantle pressure gradient in either communicating or non‐communicating hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2002;50:763–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sterne 2011

- Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D (editors). Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors).Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Stoltze 2001

- Stolze H, Kuhtz‐Buschbeck JP, Drücke H, Jöhnk K, Illert M, Deuschl G. Comparative analysis of the gait disorder of normal pressure hydrocephalus and Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 2001;70:289‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tanaka 1997

- Tanaka A, Kimura M, Nakayama Y, Yoshinaga S, Tomonaga M. Cerebral blood flow and autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus syndrome. Neurosurgery 1997;40:1161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tanaka 2009

- Tanaka N, Yamaguchi S, Ishikawa H, Ishii H, Meguro K. Prevalence of possible idiopathic normal‐pressure hydrocephalus in Japan. Neuroepidemiology 2009;32(3):171‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomsen 1986

- Thomsen AM, Borgesen SE, Bruhn P, Gjerris F. Prognosis of dementia in normal pressure hydrocephalus after a shunt operation. Annals of Neurology 1986;20:304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Unnebrink 2001

- Unnebrink K, Windeler J. Intention‐to‐treat: methods for dealing with missing values in clinical trials of progressively deteriorating diseases. Statistics in Medicine 2001;20(24):3931‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vanneste 1992

- Vanneste J, Augustijn P, Dirven C, Tan WF, Goedhart ZD. Shunting normal pressure hydrocephalus: do the benefits outweigh the risks? A multicenter study and literature review. Neurology 1992;42(1):54‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vanneste 1994

- Vanneste JAL. Three decades of normal pressure hydrocephalus: are we wiser?. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1994;57:1021‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Waldemar 1993

- Waldemar G, Schmidt JF, Delecluse F, Andersen AR, Gjerris S, Paulson OB. High resolution SPECT with [99mTc]‐d, l‐HMPAO in normal pressure hydrocephalus before and after shunt operation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1993;56:655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wikkelsø 2013

- Wikkelsø C, Hellström P, Klinge PM, Tans JT, European iNPH Multicentre Study Group. The European iNPH Multicentre Study on the predictive values of resistance to CSF outflow and the CSF Tap Test in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 2013;84(5):562‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]