Abstract

Interactions between T cell receptors (TCRs) and their cognate tumour antigens are central to antitumour immune responses1-3; however, the relationship between phenotypic characteristics and TCR properties is not well elucidated. Here we show, by linking the antigenic specificity of TCRs and the cellular phenotype of melanoma-infiltrating lymphocytes at single-cell resolution, that tumour specificity shapes the expression state of intratumoural CD8+ T cells. Non-tumour-reactive T cells were enriched for viral specificities and exhibited a non-exhausted memory phenotype, whereas melanoma-reactive lymphocytes predominantly displayed an exhausted state that encompassed diverse levels of differentiation but rarely acquired memory properties. These exhausted phenotypes were observed both among clonotypes specific for public overexpressed melanoma antigens (shared across different tumours) or personal neoantigens (specific for each tumour). The recognition of such tumour antigens was provided by TCRs with avidities inversely related to the abundance of cognate targets in melanoma cells and proportional to the binding affinity of peptide–human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complexes. The persistence of TCR clonotypes in peripheral blood was negatively affected by the level of intratumoural exhaustion, and increased in patients with a poor response to immune checkpoint blockade, consistent with chronic stimulation mediated by residual tumour antigens. By revealing how the quality and quantity of tumour antigens drive the features of T cell responses within the tumour microenvironment, we gain insights into the properties of the anti-melanoma TCR repertoire.

Although single-cell studies have demonstrated the heterogeneous cellular states of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)1, the extent to which such phenotypic properties are linked to the specificities of TCRs and which functional states are enriched in cells bearing TCRs with antitumour reactivity remain unanswered. Recent studies have highlighted the variability in the intrinsic capacity of TCRs to recognize autologous cancers, and the general rarity of true antitumour TCRs2 owing to the presence of bystander T cells lacking antitumour function3. Here we used testing against patient-derived melanoma cell lines (pdMel-CLs)4,5 to define the tumour reactivity of CD8+ TCR clonotypes infiltrating the tumour microenvironment of patients with melanoma, allowing the unambiguous determination of the properties associated with true tumour-reactive lymphocytes.

Cell state of CD8+ TIL-TCR clonotypes

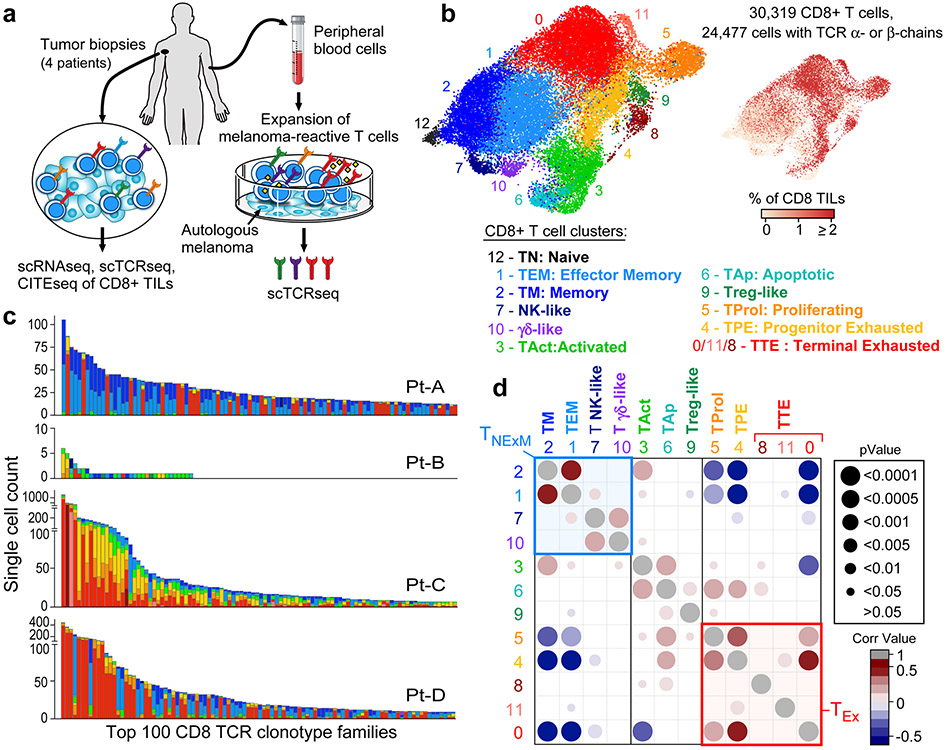

We focused on five tumour specimens collected from four previously reported patients4,6 (Pt-A, Pt-B, Pt-C and Pt-D) with stage III/IV melanoma (Extended Data Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). To characterize the phenotype and clonality of CD8+ TILs (Fig. 1a), we used high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-cell TCR sequencing (scTCR-seq) coupled with the detection of surface proteins (that is, cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq)7) (Supplementary Table 2). Our dataset of transcriptomes from 30,319 single CD8+ T cells derived mainly from the 3 biopsies with modest or high T cell infiltration (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Table 3).

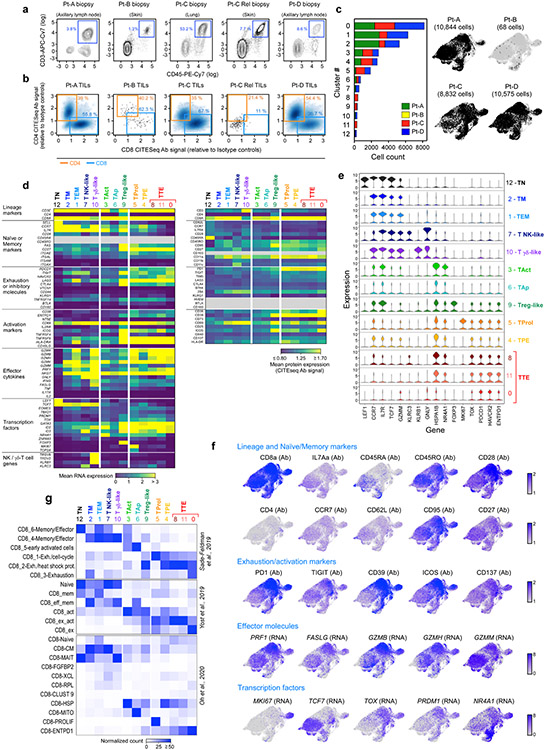

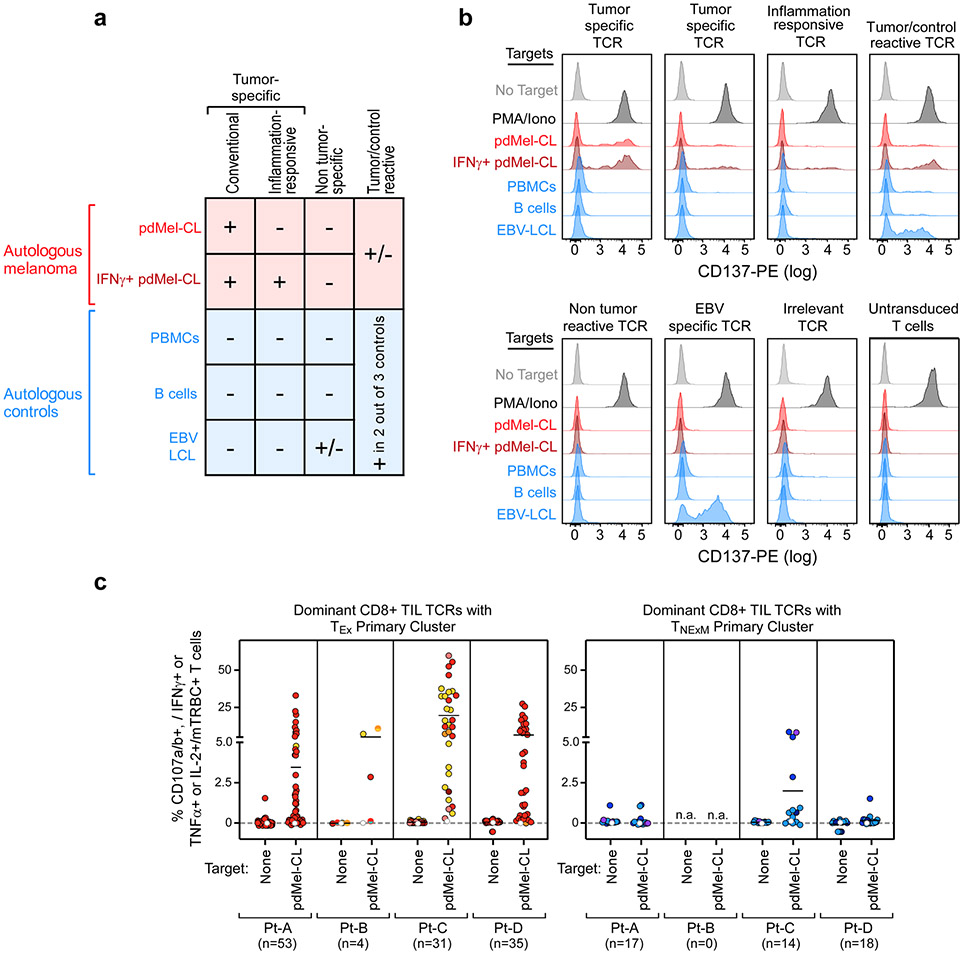

Fig. 1 ∣. Distinct cell states among CD8+ TCR clonotype families in melanoma.

a, Schema of sample collection, processing and single-cell sequencing analysis of melanoma and peripheral blood samples. b, UMAP of scRNA-seq data from CD8+ melanoma TILs. Clusters are denoted by colours and labelled with inferred cell states. The same UMAP (right) shows TILs marked on the basis of intrapatient TCR clone frequency defined through scTCR-seq. c, Cluster distribution of the top 100 CD8+ TCR clonotype families from melanoma A–D. The colours denote cell states, as delineated in b. d, Two-sided Spearman correlation of normalized cluster distribution of dominant TCR clonotype families comprising five or more cells. The colours and the area of the circles indicate the strength and significance of the correlation, respectively.

CD8+ TILs clustered into 13 subsets (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 4), classified on the basis of RNA and surface protein expression of T-cell-related genes and by cross-labelling with reference gene signatures from external single-cell datasets of human TILs8-10 (Extended Data Fig. 2d-g). This process (Methods) allowed definition of five major populations: effector memory (TEM) and memory (TM), acutely activated (TAct), terminally exhausted (TTE) and progenitor exhausted (TPE) TILs. Six additional minor clusters included proliferating T (TProl) cells, apoptotic T (TAp) cells, natural killer (NK)-like cells, contaminant regulatory T (Treg)-like cells, γδ-like T cells and naive T (TN) cells.

We evaluated the relationship between phenotype and TCR clonality in 7,239 different clonotypes identified by scTCR-seq (Extended Data Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 3). Highly expanded clonotype families were distributed predominantly in cells with exhausted phenotypes (Fig. 1b, right), which showed decreased diversity of TCRs (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Most of the TCR clonotypes were confined to a defined area of the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) (Extended Data Fig. 3c); although individual cells with the same TCR could map to different clusters, the vast majority were largely restricted to clusters with similar levels of exhaustion. The distributions of cells with the same TCRs fell in one of two distinct patterns, in which the predominant phenotype per clonotype was either ‘non-exhausted memory’ (TNExM: TM + TEM + γδ-like + NK-like) or ‘exhausted’ (TEx: TTE +TPE + TProl) (Fig. 1c, d). The less-differentiated TM and TEM cells segregated together, but were negatively correlated with exhausted TILs. Thus, for most clonotype families, CD8+ TILs were either distributed among clusters with exhausted phenotypes or among non-exhausted phenotypes, allowing us to assign a ‘primary cluster’ to each expanded TCR clonotype family as an approximate phenotype.

Phenotype of antitumour CD8+ T cells

The detection of two distinct phenotypic patterns, each delineated on the basis of the identity of TCRs, led us to hypothesize that this separation was driven by the recognition of different antigens, resulting in different antitumour potential. We thus tested the ability of the most highly represented TCRs whose primary clusters were either TEx (n = 123) or TNExM (n = 49) to recognize autologous pdMel-CLs, each confirmed to recapitulate the genomic and transcriptomic features of parental tumours (Extended Data Fig. 4). Upon cloning and lentiviral transduction in T cells from healthy individuals (Fig. 2a), effector cells expressing individual TCRs were multicolour-labelled to enable parallel screening of antigenic specificities using multiparametric flow cytometry (Methods). Transduction of the TCR signal, detected as upregulation of the CD137 protein11, was measured upon co-culture of effector pools against pdMel-CLs and against non-tumour controls (autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells, B cells and Epstein–Barr virus-immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-LCLs)).

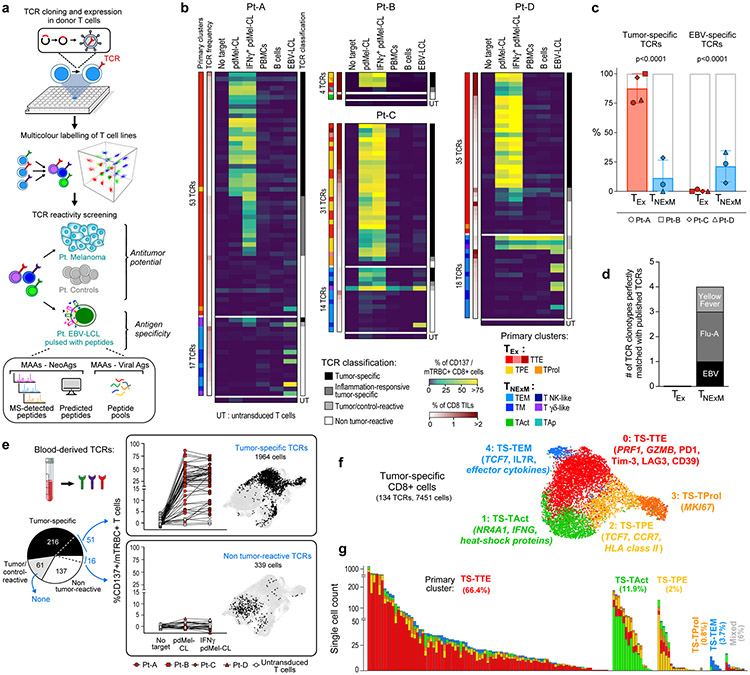

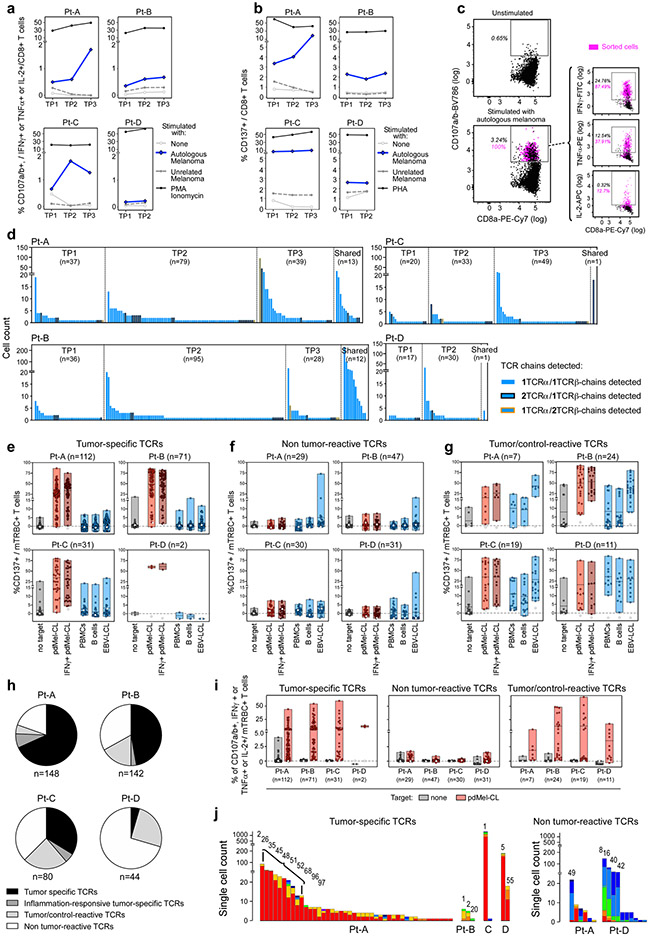

Fig. 2 ∣. Target specificity and phenotype of tumour-specific CD8+ TCRs.

a, Schematic of the workflow for in vitro TCR reconstruction and specificity screening. Multiple TCRs are cloned and expressed in healthy donor T cells (top). Pools of colour-labelled effectors expressing individual TCRs are tested for reactivity against autologous melanoma, controls or EBV-LCLs (middle and bottom) that could be pulsed with peptides from NeoAgs, MAAs or viral antigens selected from mass spectrometry (MS) detection of HLA class I tumour immunopeptidomes, from computational prediction or from commercially available peptide pools. b, Reactivity of dominant TCRs sequenced among TEx (top) or TNExM (bottom) clusters in melanoma A–D. CD137 upregulation was measured on TCR-transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ T cells cultured alone (no target) or in the presence of autologous melanoma cells (pdMel-CLs; with or without interferon-γ (IFNγ) pre-treatment) or controls (peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), B cells and EBV-LCLs). Background detected on CD8+ T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR was subtracted. Left track, TCR phenotype (primary cluster) and frequency among CD8+ TILs from patients; right track, classification of TCR reactivities (Extended Data Fig. 5a). UT, untransduced cells. c, Proportion of TCRs classified as tumour-specific (left) or EBV-specific (right) among TEx-TCRs (red; n = 123) or TNExM-TCRs (blue; n = 49) in melanoma A–D. Mean ± s.d. are shown. P values were calculated using two-tailed Fisher’s exact test on the total distribution of tested TCRs. d, Number of TCRs from TEx or TNExM clusters perfectly sequence matched with viral TCRs from TCRdb12. Flu-A, influenza-A specific TCR. e, Spectrum of reactivities and phenotypes of TCRs isolated from blood, traced within the tumour microenvironment. Left, classification of TCRs isolated from the blood of patients with melanoma A–D and screened in vitro. Per boxed panels, antitumour reactivity of TCRs traced within TILs (filled symbols), measured as CD137 upregulation, compared with nonspecific activation of untransduced cells (open symbols) (left). UMAP distribution of cells bearing TCRs of interest (right). f, Cell states of tumour-specific (TS) CD8+ TILs, bearing any of the 134 TCRs with in vitro-verified antitumour specificity. g, Cluster distribution of tumour-specific TCRs, grouped on the basis of their primary cluster, and coloured on the basis of the tumour-specific clusters represented in f.

In total, 102 of 123 (83%) TEx-TCRs analysed across 4 patients were confirmed to be tumour-specific (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). Conversely, only 5 of 49 TNExM-TCRs (10%) exhibited tumour recognition (Fig. 2b), whereas 11 (22%) non-tumour-reactive TCRs recognized EBV-LCLs, supporting their specificity for viral antigens. TEx-TCRs, but not TNExM-TCRs, conferred both activation and cytotoxic potential to transduced lymphocytes (Extended Data Fig. 5c). In addition, five TNExM-TCRs demonstrated nonspecific recognition of both melanoma and control cells. Overall, TEx-TCRs clonotypes were enriched in antitumour specificities, whereas TNExM-TCRs were enriched in anti-EBV specificities (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c). Moreover, public TCR sequences with known antiviral specificities12 could be matched only to four TNExM-TCRs (Fig. 2d).

In a complementary evaluation of blood-derived T cells, we first single-cell sequenced TCRs from circulating melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cells isolated following in vitro stimulation of serially collected peripheral blood mononuclear cells with autologous pdMel-CLs (Fig. 1a, right, Extended Data Fig. 6a-c), and then mapped them to the expression states delineated within TILs to discover their phenotype. Across 4 patients, 414 of 491 sequenced TCRs were reconstructed and screened in vitro against autologous melanoma and controls (Extended Data Fig. 6d-i). Tumour specificity was established for 216 (52%) blood-derived TCRs (Fig. 2e, left), whereas 61 (15%) blood-derived TCRs showed nonspecific reactivity and 137 (33%) were not reactive against pdMel-CLs. Fifty-one tumour-specific and 16 non-tumour-reactive blood-derived TCRs were tracked back to CD8+ TILs by matching TCRα–TCRβ chains across these two tissue compartments. Again, we observed that tumour-specific TCRs preferentially exhibited TEx phenotypes, whereas the majority of non-tumour-reactive TCRs were traced to TNExM clusters (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2e, right, Extended Data Fig. 6j).

We validated these results by reconstructing 94 clonally expanded TCRs sequenced from CD8+ TILs of 8 independent patients with metastatic melanoma previously characterized by scRNA-seq8 (Supplementary Table 5). In total, we identified 7 virus-specific TCRs, reactive against autologous EBV-LCLs or matched with public antiviral specificities12, and 22 potentially tumour-specific TCRs, reactive against a panel of 12 melanoma-associated antigens (MAAs) (Extended Data Fig. 7a-c). Virus-specific and MAA-specific TCRs were expressed by CD8+ TILs with distinct transcriptomic profiles; the former mapped preferentially to previously described memory clusters, whereas the latter mapped almost exclusively to exhausted subsets (P < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) (Extended Data Fig. 7d, e). Direct comparison of virus-specific and MAA-specific cells highlighted transcriptional upregulation of exhaustion genes (PDCD1, HAVCR2 and CTLA4) (Extended Data Fig. 7f). Thus, antitumour TILs clearly reside within the exhausted compartment rather than within the less-differentiated TNExM compartment, and the acquisition of TEx profiles within the tumour microenvironment is an antigen-driven process.

The ability to unambiguously determine the antitumour reactivity of 134 TCRs validated from our discovery cohort prompted us to investigate the cellular phenotypes of true tumour-specific CD8+ TILs. First, tumour-specific TILs could be distinguished from virus-specific TILs based on the deregulation of 98 transcripts (Extended Data Fig. 7g, h, Supplementary Table 6), including known genes encoding transcription factors (TCF7/TOX) and genes (IL7R, CCR7/PDCD1, HAVCR2 and ENTPD1) associated with memory or exhausted cell states. Six surface proteins were highly expressed on tumour-specific TCR clonotypes, the highest of which were PD1 and CD39, which have previously been associated with antitumour responses2,3,13-15.

Second, we captured the fine differences among tumour-specific TILs by reclustering the 7,451 cells with the 134 tumour-specific TCRs. We detected five tumour-specific clusters (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Table 7), scored on the basis of RNA and surface protein expression (Extended Data Fig. 7i, j) and on enrichment of gene signatures annotated from internal or external datasets (Extended Data Fig. 7k, Supplementary Table 8). We identified: (1) tumour-specific TTE cells, which resembled human8,9 and mouse16-19 TTE cells, due to a high expression of PRF1 and GZMB transcripts and exhaustion proteins (PD1, Tim3 (encoded by HAVCR2), LAG3 and CD39); (2) tumour-specific TAct cells, which corresponded to acutely activated TILs9,20, given their high expression of IFNG and heat shock protein transcripts; (3) tumour-specific TPE cells, characterized by positivity for TCF7 and CCR7, high levels of activation (HLA-DR and CD137) and lower exhaustion, but absent cytotoxic potential, consistent with previously described TPE cells16-19; (4) tumour-specific TProl cells, which were highly exhausted but in active proliferation; and (5) tumour-specific TEM cells, which resembled human and mouse memory T cells with stem-like properties9,16,21-23 because of the highest expression of memory markers (TCF7 and IL7R), low level of exhaustion, and expression of effector cytokines. Analysis of such cell states in relation to TCR clonality demonstrated that 78.3% of tumour-specific TCR clonotypes were skewed towards tumour-specific TTE or tumour-specific TAct phenotypes, even as the cellular members of each TCR clonotype could acquire any of the tumour-specific phenotypes (Fig. 2g). Only a minor portion of tumour-specific cells or tumour-specific TCRs acquired tumour-specific TPE or tumour-specific TEM states. Thus, the activation and differentiation of antitumour CD8+ TILs within the tumour microenvironment led to their preferential accumulation as exhausted cells rather than as less-differentiated memory effectors.

Specificity and avidity of antitumour TCRs

We investigated how the specificity and avidity of TCRs determines the properties of CD8+ tumour-specific cells in our discovery cohort. The specificity of 561 TCRs (299 tumour-specific and 262 non-tumour-specific) isolated from TILs or blood (Fig. 3a, left) was determined based on co-culture with autologous EBV-LCLs pulsed with hundreds of peptides corresponding to: (1) personal neoantigens (NeoAgs) (Supplementary Table 9), (2) public MAAs (Supplementary Table 10); or (3) common viral antigens, either detected as displayed on pdMel-CLs within respective human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I immunopeptidomes, or defined by prediction pipelines or commercially available as peptide pools (Fig. 2a, bottom, Methods).

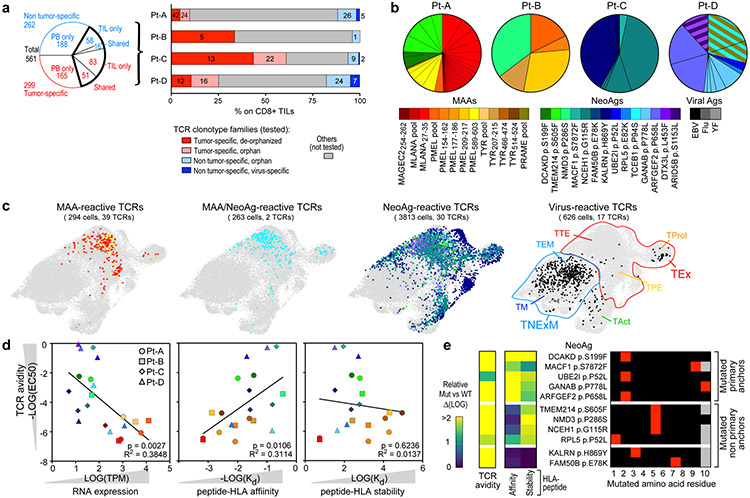

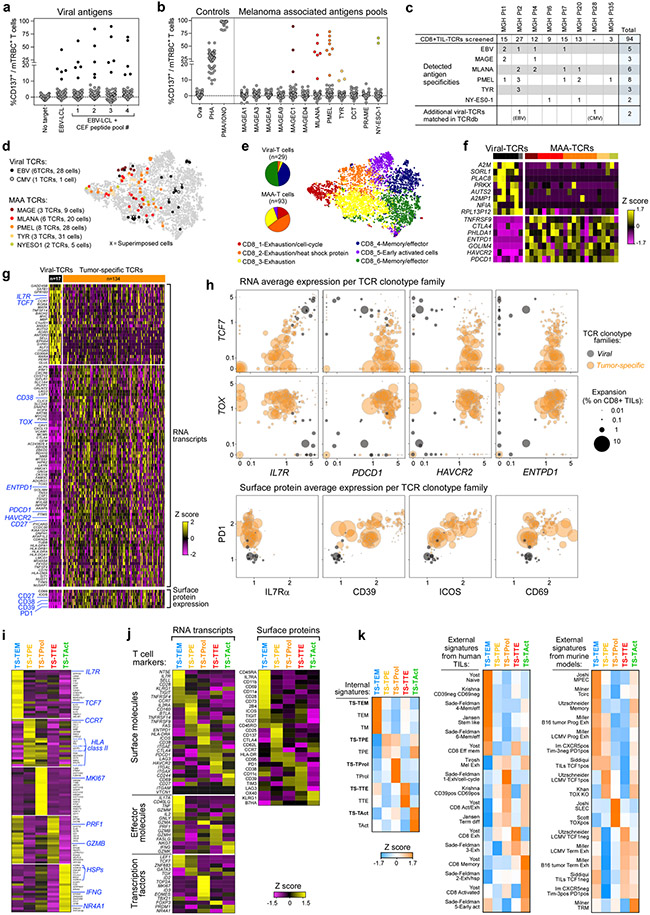

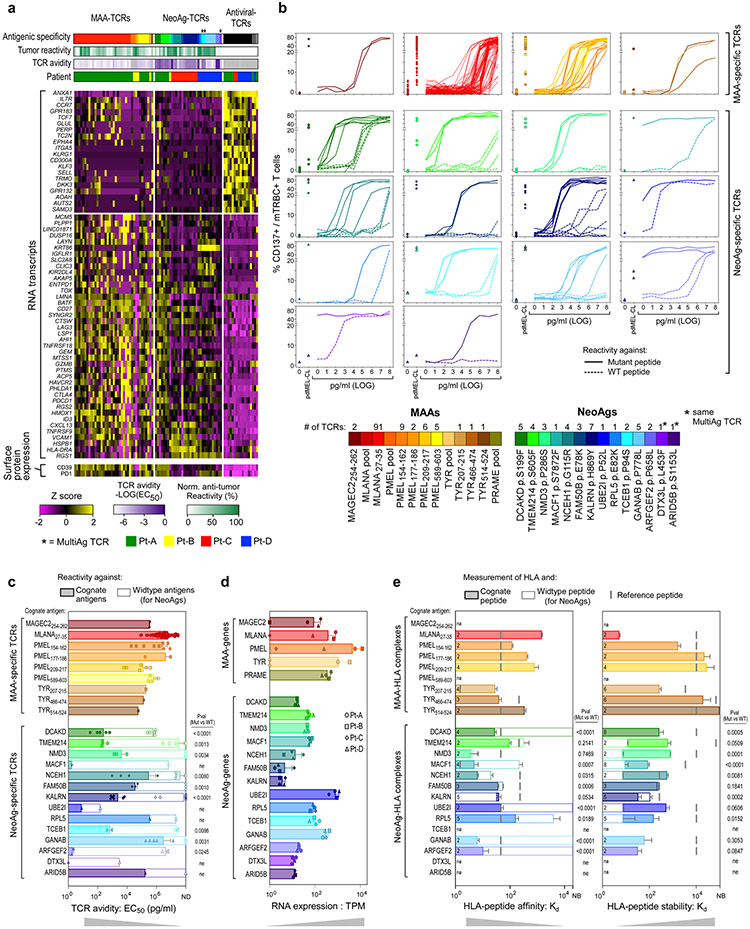

Fig. 3 ∣. Antigenic specificity and avidity of tumour-specific TCRs.

a, Summary of evaluated TCRs, classified on the basis of tumour specificity and compartment of detection (blood or tumour). The bar plot shows intrapatient distribution of tested TCR clonotypes among CD8+ TILs. Tested TCRs are colour-coded based on tumour specificity and whether reactivity to cognate antigen was detected. The numbers of TCRs corresponding to each category are reported. PB, peripheral blood. b, Summary of the deorphanized antigen specificity of tumour-specific TIL-TCRs, showing the frequency (slice size) and cognate antigen (colours) for each TCR clonotype. The colour legend also applies to c and d. c, UMAPs of the phenotypic distribution of T cells bearing antitumour TCRs specific for MAAs and/or NeoAgs or TCRs specific for viral peptides. d, Parameters affecting the avidity (y axis) of antitumour TCRs, including RNA expression of TCR-targeted genes detected in the autologous pdMel-CLs (left), the affinity of peptide–HLA complexes (middle) and the stability of peptide–HLA complexes (right). The values for the avidity of TCRs, and the affinity and stability of peptide–HLA complexes represent averages of data presented in Extended Data Fig. 9. The significance of each linear regression is reported within each panel. The symbols refer to patients from whom TCRs were identified. Measurements for peptide–HLA affinity and stability are for 7 of 9 MAAs and 11 of 14 NeoAgs. EC50, half-maximal effective concentration; Kd, dissociation constant; TPM, transcripts per million mapped reads. e, The effect of the position of the mutated residue within NeoAg peptides on the avidities of TCRs and the affinities and stabilities of peptide–HLA complexes. Parameters are reported as the fold change of the mutant (Mut) relative to the corresponding wild-type (WT) peptides.

In total, we could define the antigenic specificity (‘deorphanize’) for 180 of 561 TCRs (166 of 299 (56%) tumour-specific, 14 of 261 (5%) non-tumour-specific). The 166 tumour-specific TCRs recognized 14 NeoAgs and 5 MAAs (Extended Data Fig. 8). In rare cases (n = 3, Pt-D), we documented TCR reactivity against multiple targets (MAA–NeoAg or NeoAg–NeoAg), presented within the same HLA context (Supplementary Information, ‘Flow-cytometry data’). To link antigen specificity with intratumoural phenotypes, we focused on the 72 MAA-specific or NeoAg-specific TCRs detected within TILs; these constituted 4.7–43.9% of CD8+ TILs per patient (Fig. 3a, b). MAA-specific and NeoAg-specific tumour-specific TCRs were predominantly distributed among TEx clusters; by contrast, cells bearing ‘bystander’ non-tumour-reactive TCRs with antiviral specificity distinctly exhibited a TNExM profile (Fig. 3c). Direct comparison of cells bearing the deorphanized TCRs revealed no differences between the profiles of MAA-specific and NeoAg-specific clonotypes, which shared downregulation of memory markers (for example, IL7R and TCF7) and upregulation of exhaustion genes (for example, PDCD1, ENTPD1 and TOX) when compared with viral TCR clonotypes (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Thus, the recognition of tumour antigens but not the type (MAA and NeoAg) of tumour antigens appeared to determine the phenotype of CD8+ tumour-specific TILs.

To delineate the relationships between the type of tumour antigen and the strength of peptide recognition, we evaluated 157 of 166 deorphanized tumour-specific TCRs for which we could identify the minimal peptide epitope (Extended Data Fig. 9b, Supplementary Table 11). MAA-specific TCRs displayed intermediate or low avidities (median: 3.5 × 105 pg ml−1, range: 5.9 × 104 to 4.5 × 106) (Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). By contrast, the majority of NeoAg-specific TCRs recognized the mutated cognate antigens at substantially lower concentrations (median: 1.1 × 103 pg ml−1, range: 1 × 100 to 1.4 × 106; P < 0.0001, two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test) and therefore demonstrated high or intermediate avidities for cognate mutated antigens. No differences in the transcript or protein expression levels were observed among cells bearing tumour-specific TCRs with high versus low avidity or with high versus low strength of tumour recognition (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Given this, we sought to determine how the range of TCR avidities correlated with features affecting antigen presentation24. As expected, MAA-related genes were expressed at higher levels in autologous pdMel-CLs than NeoAgs, and for all of the detected TCR–antigen pairs, the avidity of TCRs was inversely correlated with tumour-antigen abundance (P = 0.0027) (Fig. 3d, left, Extended Data Fig. 9d). The higher avidity of NeoAg-specific TCRs was also associated with an experimentally measured higher affinity of interaction between peptides and HLA class I molecules (P = 0.0106), but not to measured peptide–HLA stability (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 9e).

We found that the position of the altered residues among the neoepitopes could affect the high avidity of NeoAg–TCRs and their ability to distinguish the wild-type epitopes (Fig. 3e): (1) mutations at primary anchor residues (positions 2 and 9–10) determined increased binding strength and stability of mutant peptide–HLA complexes compared with corresponding wild-type peptides; (2) mutations at non-primary anchor residues did not markedly enhance the affinity of peptide–HLA complexes, but rather increased their stability; and (3) mutations in residues exposed towards the outside of the HLA pocket (positions 3 and 7) affected neither the affinity nor the stability of peptide–HLA complexes, and hence the altered residue was inferred to directly affect peptide–TCR interactions.

Blood dynamics of CD8+ TIL-TCRs

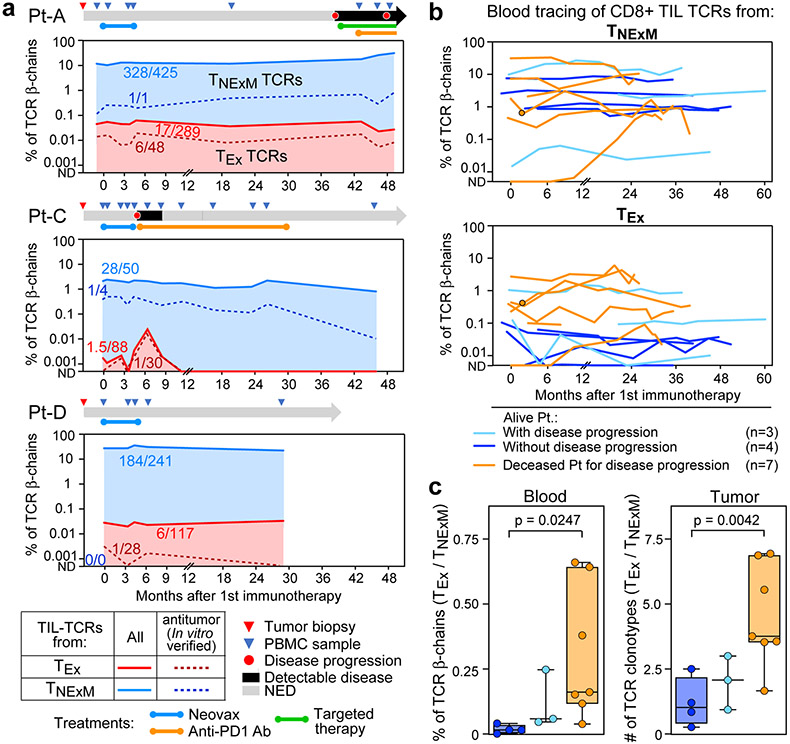

To explore the systemic dynamics of TIL clones, we performed bulk TCRβ chain sequencing of T cells from longitudinal peripheral blood samples, and traced the behaviour of CD8+ clonotypes with intratumoural TEx or TNExM phenotypes in three patients with abundant TIL-TCRs (Fig. 4a). A greater proportion of TNExM-TCRs were detected, which resulted in far more stably abundant circulating TNExM-TCRs than TEx-TCRs (P < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Such circulating repertoire, enriched in virus-reactive specificities, ensures host immunosurveillance and probably infiltrates tumours due to blood perfusion or recognition of non-tumour antigens rather than active recognition of melanoma antigens. TEx-TCRs were relatively rare among circulating cells, consistent with the predominant residence of these high tumour-specific cells within the tumour microenvironment, where stimulation by tumour antigens could lead to acquisition of the observed exhaustion. Thus, the exhaustion state of TIL-TCRs negatively affected their persistence in peripheral circulation. Consistently, exhausted MAA-specific or NeoAg-specific TCRs were rarely detectable in blood (16 of 166 TCRs (9.6%) across 4 patients), whereas the majority of non-exhausted antiviral specificities were present in the circulation at high frequency (15 of 18 TCRs (83%)) (Extended Data Fig. 10a). A similar pattern was noted for the very rare antitumour TNExM-TCRs (Fig. 4a).

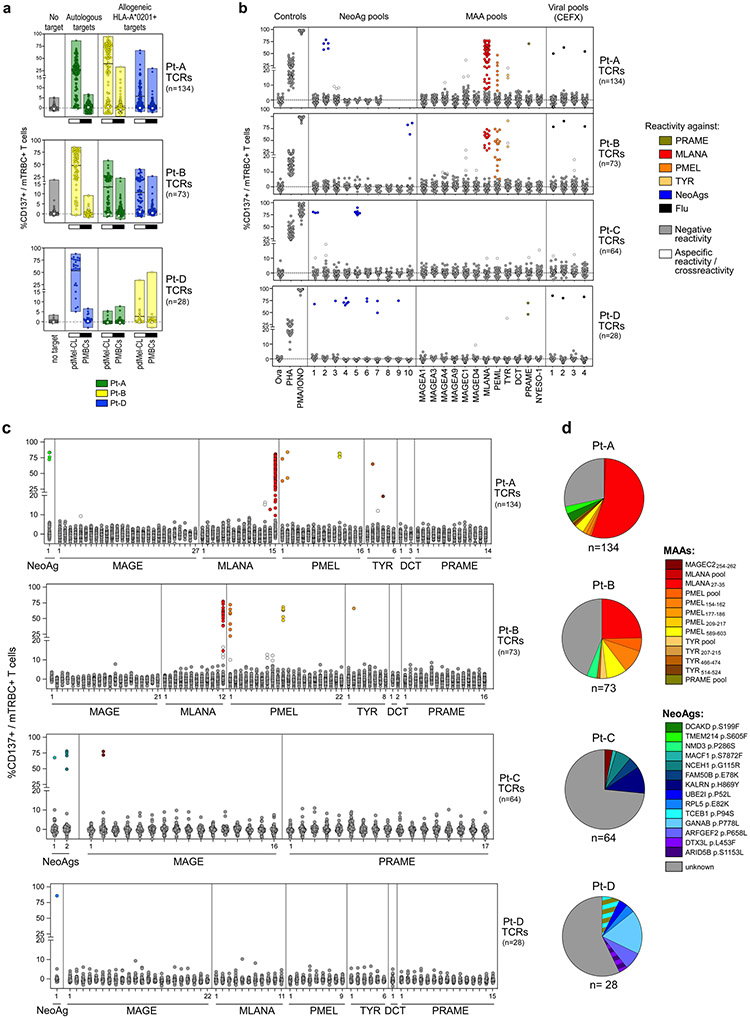

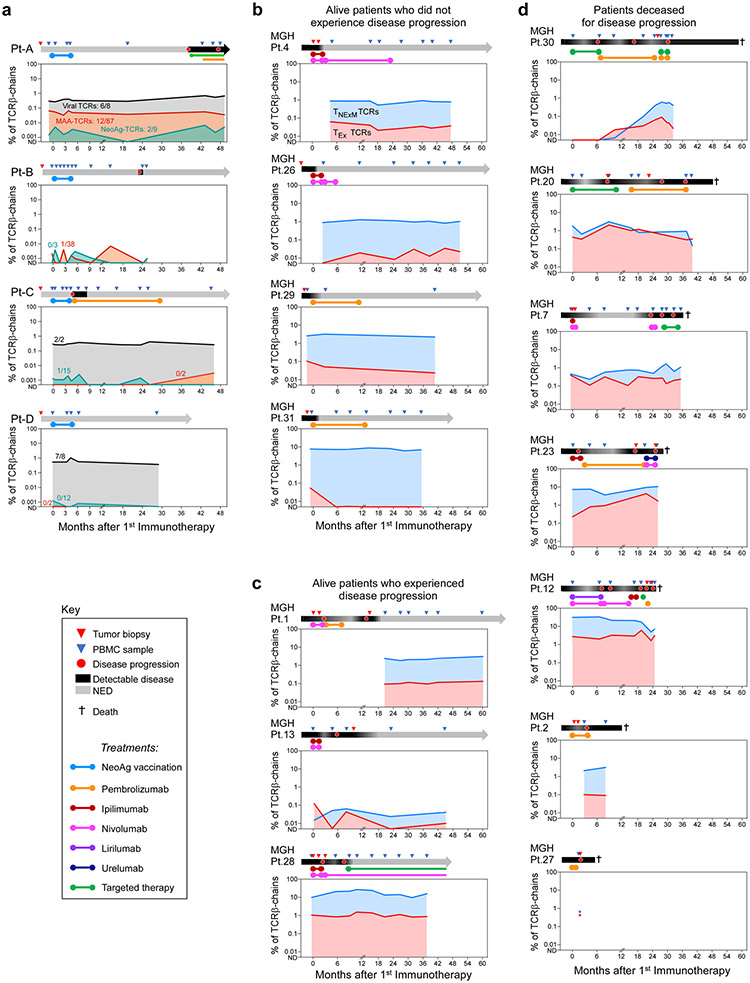

Fig. 4 ∣. Peripheral blood dynamics of CD8+ TIL-TCRs.

a, Systemic dynamics of T cells bearing intratumoural CD8+ with exhausted (light red) or non-exhausted memory (light blue) clusters. The levels of circulating TCRs with in vitro- verified antitumour reactivity are shown with dark dashed lines. TCRs were quantified through bulk TCRβ chain sequencing of CD3+ T cells isolated from serial peripheral blood sampling of the three patients with high numbers of TIL-TCRs. The numbers within the graphs are the median number of TCRs detected longitudinally out of the total number of TCRs within each category. Per patient, a schematic of clinical history and sample collection is depicted. Anti-PD1 Ab, anti-programmed cell death protein 1 antibody; ND, not detectable; NED, no evidence of disease. b, Circulating counts of T cells with TCRs detected among CD8+ TILs classified as non-exhausted (top) or exhausted (bottom). Samples were collected from 14 patients with melanoma8 who experienced long-term remission (blue; n = 7) or poor clinical outcome (orange; n = 7) after immunotherapy treatment. Patients with good clinical outcome were further divided into those who did (n = 4) or did not experience (n = 3) disease progression following treatment. Single dots show values for patients with a single time point available. c, Ratio of exhausted versus non-exhausted TCR families for the validation cohort reported in b. The box plots depict the median ratio of blood frequencies measured through bulk TCR-seq (left) or of clonotype counts detected within TILs in published single-cell sequencing data8 (right) of TCRs with an TEx versus TNExM intratumoural phenotype. The whiskers show the minimum to maximum values, the horizontal bars are the medians and the boxes depict the 25–75th percentiles. For the P values, significant comparisons were calculated with two-tailed Welch’s t-test.

Finally, we explored the relationship between the levels of circulating TNExM and TEx CD8+ TILs and clinical outcome by analysing an independent cohort of 14 patients with metastatic melanoma treated with immune checkpoint blockade, as previously reported8 (Supplementary Table 5). The systemic frequencies of TIL-TCRs, classified as TEx or TNExM (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 2g), were measured among circulating T cells through sequencing of TCRβ chains. Consistent with our analysis, intratumoural TNExM-TCRs were stable and predominant among circulating clonotypes in most of the analysed patients (Fig. 4b, top, Extended Data Fig. 10b, c). Conversely, TEx-TCRs were quite rare, but persisted at levels that correlated with long-term outcomes; the majority of patients who eventually succumbed to disease displayed higher levels of circulating TEx-related TCRs, both before and after immunotherapy (Fig. 4b, bottom). Compared with TNExM-TCRs, TEx-TCRs were more abundant in patients who experienced disease progression (Fig. 4c, left). These systemic dynamics mirrored the different proportions of TEx cells within the intratumoural microenvironment (Fig. 4c, right), highlighting how the frequency of circulating TEx TIL-TCRs can potentially distinguish between patients with response versus resistance to immune checkpoint blockade.

Discussion

By coupling high-resolution single-cell profiling of CD8+ TILs and reconstruction and specificity testing of hundreds of TCRs, we achieved unambiguous definition of antigen specificities, phenotypes and dynamics of tumour-specific CD8+ T cells in melanoma, and we gained numerous insights.

First, CD8+ tumour-specific TILs, whether directed against MAAs or NeoAgs, were highly enriched within the T compartment. Overall, truly tumour-reactive TILs could acquire five distinct cell states (tumour-specific TTE, TAct, TProl, TPE and TEM), but their interaction with tumour antigens within the intratumoural microenvironment markedly skewed their phenotype towards a highly exhausted cell state (PD1+CD39+ (refs. 2,3,13,15)); in our discovery cohort, a proportion of tumour-specific TILs showed a TPE phenotype and only rarely acquired a CD39−PD1− memory state22,23.

Second, the deorphanization of tumour-specific TCRs enabled us to establish the key relationships between tumour recognition and TCR properties. TILs with MAA-specific and NeoAg-specific TCRs converged on a similar level of exhaustion, but this was triggered by the stimulation of TCRs with different properties. MAA-specific TCRs more often exhibited low avidities and displayed strong tumour recognition, as their cognate antigens were abundantly available (due to their high tumour expression). By contrast, the majority of NeoAg-specific TCRs exhibited markedly higher avidities that were generated by the high affinities and increased stabilities of mutated peptide–HLA interactions, exerted towards cognate antigens expressed at relatively lower levels. In total, these observations point to the effect of central tolerance on the generation of tumour antigen-specific TCRs.

Third, we found that the circulating levels of exhausted TIL-TCRs correlated with disease persistence. In patients with progressive disease, chronic tumour stimulation, reflecting an incomplete response to immunotherapy, resulted in an increased fraction of TEX-TILs locked in exhausted states. Our data therefore underscore the importance of generating new non-exhausted T cells to achieve a productive antitumour response. Indeed, various studies have suggested that effective antitumour responses elicited by immunotherapy may arise from new specificities generated outside the tumour and hence not subject to active exhaustion9,25, or might derive from revived intratumoural tumour-specific TPE precursors or TEM cells endowed with regenerative potential16. To this point, we note that Pt-C, who achieved complete response after immune checkpoint blockade (Extended Data Fig. 1), was characterized by the presence of antitumour TCRs having a TPE primary cluster and relatively few tumour-specific TCRs with TNExM phenotypes within the tumour microenvironment (Figs. 1c, 2b). In line with this observation, recent studies have revealed that patients with melanoma with higher frequencies of intratumoural TPE cells experienced a durable response to immune checkpoint blockade16, and that rare less-exhausted tumour-specific cells can be expanded from TILs upon ex vivo activation, to acquire a reinvigorated CD39− memory phenotype that associated with response to therapy and long-term persistence23. Future studies focused on similar analyses of serial tissue specimens could delineate the features and dynamics of specificities responding to immunotherapy.

Finally, our data indicate that antitumour recognition—provided by TCRs—and exhaustion are highly associated in tumours; the disentanglement of these two features through adoptive transfer26 of gene-modified T cells armed with TEx-TCRs and having a desirable memory phenotype, or through expansion of memory specificities outside the tumour with cancer vaccines27, could result in effective and personalized tumour cytotoxicity.

Methods

Study participants and patient samples

Single-cell sequencing and TCR screening analyses were conducted on four patients with high-risk melanoma enrolled between May 2014 and July 2016 to a single centre, phase I clinical trial approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) (NCT01970358). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The details about eligibility criteria have previously been described4, and all participants received NeoAg-targeting peptide vaccines, as previously reported (Supplementary Table 1). Tumour samples were obtained immediately following surgery and processed as previously described4 for single-cell analyses (Supplementary Methods). Heparinized blood samples were obtained from the same study participants on IRB-approved protocols at the DFCI.

The analysis was extended to an independent cohort of 16 patients with metastatic melanoma treated with immune checkpoint blockade therapy (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston), as previously reported8. The updated clinical data of such patients are summarized in Supplementary Table 5. All patients provided written informed consent for the collection of tissue and blood samples for research and genomic profiling, as approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center IRB (DF/HCC protocol 11-181).

Melanoma cell lines were characterized with whole-exome sequencing and RNA-seq as previously described4,5. HLA class I expression and the HLA class I binding immunopeptidome of melanoma cell lines were detected using mass spectrometry-based proteomics. A detailed description is reported in Supplementary Methods.

Processing of single-cell data

Processing of scTCR-seq data.

scTCR-seq data for each sample were processed using Cell Ranger software (version 3.1.0). TCRs were grouped in patient-specific TCR clonotype families on the basis of TCRα–TCRβ chain identity, allowing for a single amino acid substitution within the TCRα–TCRβ CDR3. Cells with a single TCR chain were included and grouped with the matched clonotypes families. The resulting TCR clonotype families were ranked according to sample-specific size and incorporated into downstream analysis. This procedure was reiterated on all samples sequenced from the same patient and results were manually reviewed. The same strategy was also used to match TCR clonotypes from TILs with those isolated and sequenced from PBMCs upon in vitro co-culture with melanoma cells. Owing to the low number of TCR clonotypes specific for Pt-C-rel specimen (n = 7), Pt-C and Pt-C-rel TILs were analysed together (referred as Pt-C within the text).

Processing and analysis of scRNA-seq and CITE-seq data.

scRNA-seq data were processed with Cell Ranger software (version 3.1.0). scRNA-seq count matrices and CITE-seq antibody expression matrices were read into Seurat (version 3.2.0)28. For each batch of samples comprising all tumour or PBMC single-cell data acquired for a single patient, a Seurat object was generated. Cells were filtered to retain those with 20% or less mitochondrial RNA content and with a number of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) comprised between 250 and 10,000. Overall, scRNA-seq data comprised 1,006,058,131 transcripts in 288,238 cells that passed quality filters. scTCR-seq data were integrated and cells with three or more TCRα chains, three or more TCRβ chains or two TCRα and two TCRβ chains were removed. scRNA-seq data was normalized using Seurat NormalizeData function and CITE-seq data using the centre log-ratio (CLR) function. CITE-seq signals were then expressed as relative to isotype control signals of each single cell, by dividing each antibody signal by the average signal from three CITE-seq isotype control antibodies used. For cells with an average isotype signal less than one, all of the corresponding CITE-seq signals were increased of a value equal to ‘1 – mean isotype signal’.

Each patient dataset was scaled and processed under principal components analysis using the ScaleData, FindVariableFeatures and RunPCA functions in Seurat. Serial custom filters were used to identify CD8+ T lymphocytes; first, UMAP areas with predominance of cells belonging to FACS-sorted CD45+CD3+ populations (either processed from blood or tumour) and with high expression of the CD3E transcripts were selected. Second, possible contaminants belonging to B and myeloid lineages were removed by excluding cells characterized by either high expression of CD19 and ITGAM transcripts or positivity for CD19 or CD11b CITE-seq antibodies. Last, remaining events were grouped in CD8+ or CD4+ cells using the corresponding CITE-seq antibodies, and CD8+CD4− lymphocytes were selected. These steps were designed to maximize the ability to correctly detect CD8+ T cells by relying on the actual surface protein expression of CD8a, thus avoiding cell loss due to possible false negatives at the RNA level. Cells classified as CD8+CD4− from tumour specimens of the four patients were combined using the RunHarmony function in Seurat with default parameters29. Data were normalized, scaled and principal component analyses were computed as previously described. UMAP coordinates, neighbours and clusters were calculated with the reduction parameter set to ‘harmony’. Cluster stability over objects with different resolutions was evaluated to select the appropriate level of resolution (0.6). Clusters composed of less than 200 cells were not characterized. Markers specific for each cluster were found using FindAllMarkers function in Seurat with min.pct set to 0.25 and logfc.threshold set to log2 (Supplementary Table 4). Cluster classification was performed using RNA and surface protein expression of a panel of T cell-related genes and by cross-labelling with reference gene signatures from external single-cell datasets of human TILs8-10. By doing so, we could distinguish rare CD45RA+CD62L+CCR7 +IL7Rα+ TN cells (cluster 12) from remaining clusters of differentiated CD45RO+CD95+ cells. These included TEM and TM CD8 T cells (clusters 1 and 2, respectively) expressing memory markers (IL7R and TCF7), albeit with differential transcription of effector cytokines (GZMA, GZMB, GZMH and PRF1). Cluster 3 matched reported activated CD8+ cells (TAct), marked by the high expression of the NR4A1, which encodes a transcription factor, and heat shock proteins. A large proportion of CD8+ TILs displayed high levels of inhibitory and cytotoxic markers: cluster 0, together with 2 Pt-C-specific clusters (clusters 8 and 11; Extended Data Fig. 2c), exhibited high association with published TTE TILs and shared robust expression of genes encoding inhibitory molecules (PDCD1, TIGIT, HAVCR2 and LAG3), regulators of tissue residency (ITGAE and ZNF683) and cytotoxicity (PRF1, IFNG and FASLG). Cluster 4 was marked by the highest expression of TOX, which encodes a transcription factor, and differed from TTE on the basis of higher expression of memory-associated transcripts (TCF7, CCR7 and IL7R), consistent with previously identified TPE cells16. The other minor clusters were identified based on expression of: MKI67 (cluster 5, TProl), mitochondrial signature (cluster 6, TAp), KLRC3 (cluster 7, NK-like), CD4/FOXP3 (cluster 9, contaminant Treg-like cells) and TRDV2/TRGV9 (cluster 10, γδ-like).

Comparison of TEx clusters (0-4-5-8-11) to the remaining single cells allowed the identification of a subset of genes upregulated or downregulated in exhausted cells enriched in antitumour specificities (Supplementary Table 6). Upregulated genes (adjusted P < 0.0001, log2 fold change (log2FC) > 1) constituted the core signature of tumour-specific cells. Phenotypic distribution of TCR clonotypes composed of more than one cell (defined as TCR clonotype families) was examined using the CD8+ clusters identified through Seurat clustering. To associate a cell state to each TCR clonotype family, a primary cluster was assigned by selecting the cluster with the largest representation of cells in the clone. In cases of a tie, in which the two largest representative clusters had equal counts, no primary cluster was assigned. Cells expressing TCRs with in vitro-identified antigenic specificities were compared to establish transcripts or surface proteins deregulated among T cells specific for different antigenic categories (viral epitopes, MAAs and NeoAgs). Comparisons were performed independently for each patient using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat, and only significantly deregulated genes (adjusted P < 0.05, log2FC > 1 for scRNA-seq data; log2FC > 0.4 for CITE-seq data) in at least 2 of 4 patients were selected. The same type of analysis was performed for each patient to compare T cells containing TCRs with high (above the median) or low (below the median) avidity or normalized TCR-induced tumour-specific activation (as measured in vitro with the CD137 assay; see below). No gene was found to be recurrently deregulated among TCR clonotype families with different avidity and antitumour activity.

To analyse the subpopulations of tumour-specific CD8+ cells, 7,451 single cells expressing TCRs with in vitro-confirmed tumour-specific TCRs (n = 134) were normalized and reclustered with a resolution of 0.4 (which granted proper cluster stability). During this procedure, TCR-related genes were removed to avoid clustering artefact produced by the dramatically reduced TCR diversity. Cluster-specific genes were identified with the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat, and are reported in Supplementary Table 7. The presented single-cell dataset was compared to published datasets and evaluated for enrichment in gene signatures as described in Supplementary Methods.

TCR reconstruction and expression in T cells for reactivity screening

In vitro TCR reconstruction and antigen specificity screening were performed for TCRs from: (1) CD8+ TILs of the discovery cohort, selected to be highly expanded within the intratumoural microenvironment or having a primary phenotype representative of all the clusters classified as TEx or TNExM; (2) melanoma specimens from the validation cohort8 and detected with high frequency in seven patients with HLA-A02:01 restriction; and (3) peripheral blood of patients of the discovery cohort after enrichment for antitumour T cell responses. Selection criteria also included the availability of reliable sequences of both TCRα and TCRβ chains. Moreover, TCRs with single TCRα and TCRβ chains were preferred to TCRs with multiple chains; only for highly expanded TCRs with two TCRα or two TCRβ chains per cell, two different TCRs were studied. In such a case, the results of the most reactive TCR are reported.

The full-length TCRα and TCRβ chains, separated by a Furin SGSG P2A linker, were synthesized in the TCRβ–TCRα orientation (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into a lentiviral vector under the control of the pEF1α promoter using Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs). Full-length TCRα V-J regions and TCRβ V-D-J regions were fused to optimized mouse TRA and TRB constant chains, respectively, to allow preferential pairing of the introduced TCR chains, enhanced surface expression and functionality30-32. The cloning strategy was optimized to rapidly reconstruct up to 96 TCRs in parallel in 96-well plates with high efficiency. The assembled plasmids were transfected in 5-alpha competent Escherichia coli bacteria (New England Biolabs), which were expanded in LB medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with ampicillin (Sigma). Plasmids were purified using the 96 Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), resuspended in water and sequence-verified through standard sequencing (Eton Bioscience).

T cells were enriched from PBMCs obtained from healthy participants using the PanT cell selection kit (Miltenyi Biotech) and then activated with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Gibco) in the presence of 5 ng/ml of IL-7 and IL-15 (Peprotech) and dispensed in 96-well plates. After 2 days, activated cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding the reconstructed TCRB–TCRA chains. In brief, lentiviral vector particles were generated by transient transfection of the lentiviral packaging Lenti-X 293T cells (Takahara) with the TCR-encoding and packaging plasmids (VSVg and PSPAX2 (ref. 33)) using Transit LT-1 (Mirus). Parallel production of different lentiviral vectors encoding diverse TCRs was achieved by seeding packaging cells in 96-well plate format. Lentiviral vector supernatants were collected each day for 3 consecutive days (days 1, 2 and 3 after transfection) and used on activated T cells on days 1, 2 and 3 after activation. To increase the transduction efficiency, spinoculation (2,000 rpm for 2 h at 37 °C) in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed at day 2. Six days after activation, beads were removed using Dynal magnets and supernatant was replaced with complete medium supplemented with cytokines. Transduction efficiency was assessed using by flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of T cells expressing the mouse TCRB with the anti-mTCRB antibody (PE, clone H57-597, eBioscience). Transduced T cells were used 14 days post-transduction for TCR reactivity tests, as detailed below.

CD137 upregulation assay

The TCR transduction signal resulting from antigen recognition was assessed measuring the upregulation of CD137 surface expression on effector T cells upon co-culture with target cells. To allow for simultaneous evaluation of up to 64 distinct TCRs, T cell lines expressing distinct reconstructed TCRs were pooled after labelling with a combination of cytoplasmic dyes. In brief, TCR-transduced T cell lines were washed, resuspended in PBS at 1 × 106 cells per ml and labelled with a combination of three dyes (Cell Trace CFSE, Far Red or Violet Proliferation Kits, Life Technologies). Up to 4 dilutions per dye were created and then mixed, resulting in up to 64 colour combinations. After incubation at 37 °C for 20 min, T cells were washed twice, resuspended in complete medium and divided in pools. As internal controls, each pool contained a population of mock-transduced lymphocytes and a population of T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR. In addition, for selected T cell pools, the TCR specific for the HLA-A*0201-restricted GILGFVFTL Flu peptide33 was included as a positive control. Effector pools were plated in 96-well plates (0.25 × 106 cells per well) with the following targets: (1) pdMel-CLs (0.25 × 105 cells per well), either untreated or pre-treated with IFNγ (2,000 U/ml; Peprotech); (2) PBMCs from patients (0.25 × 106 cells per well); (3) B cells from patients (0.25 × 106 cells per well), purified from PBMCs using anti-human CD19 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec); (4) EBV-LCLs from patients (0.25 × 106 cells per well) alone or pulsed with peptides; (5) medium, as the negative control; and (6) PHA (2 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or PMA (50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) as positive controls. Peptide pulsing of target cells was performed by incubating EBV-LCLs in FBS-free medium at a density of 5 × 106 cells per ml for at least 2 h in the presence of individual peptides (107 pg/ml; Genscript) or peptide pools (each at 107 pg/ml; JPT Peptide Technologies) diluted in ultrapure DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich). Tested peptides composed pools of: (1) class I peptides (more than 70% purity) predicted from NeoAgs from patients, as previously reported4; (2) overlapping 15mer peptides (more than 70% purity) spanning the entire length of 12 MAA proteins (MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, MAGE-A4, MAGE-A9, MAGE-C, MAGE-D, MLANA, PMEL, TYR, DCT, PRAME and NYESO-1); and (3) class I and class II peptides (more than 70% purity) encoding immunogenic viral antigens (CEF pools; JPT Technologies). Tested peptides also included: individual crude peptides detected by mass spectrometry within HLA class I binding immunopeptidomes of at least one pdMel-CL, mapping to selected MAAs or NeoAgs and predicted to bind to HLA alleles of patients using NetMHCpan version 4.0; and individual crude peptides from MLANA protein (also known as MART-1), either predicted to bind to class I HLAs of patients with high MLANA tumour expression (Pt-A, Pt-B and Pt-D) using NetMHCpan version 4.0 or reported to be highly immunogenic34 (Supplementary Tables 9, 10).

Following overnight co-incubation of effector and target cells, TCR reactivity was assessed by flow-cytometric detection of CD137 upregulation on CD8+ transduced T cells, using the following antibodies: anti-human CD8a (BV785, clone RPA-T8, BioLegend), anti-mouse TRBC (PE-Cy7, clone H57-597, eBioscience) and anti-human CD137 (PE, clone 4B4-1, BioLegend). To test in vitro-enriched anti-melanoma T cells from PBMCs from patients, anti-human CD3 (APC-Cy-7, clone UCHT1, BioLegend) and Zombie Aqua viability die (BioLegend) were included in the staining procedure. Data were acquired on a high-throughput sampler-equipped Fortessa cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysed using Flowjo v10.3 software (BD Biosciences). For each tested condition, background signal measured on CD8+ T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR was subtracted. On the basis of CD137 upregulation upon challenge with the different targets, each TCR was classified as: (1) tumour-specific (conventional or inflammation responsive, based on the response detected against melanoma cell lines without or with IFNγ pre-treatment, respectively); (2) non-tumour-reactive; and (3) tumour/control-reactive, as depicted in Extended Data Fig. 5a, b. A TCR was considered tumour-reactive if the level of background-subtracted CD137 upon co-culture with melanoma cells was at least 5% with 2 standard deviations higher than that of the unstimulated control (mean value from 3 replicates per condition). Activation-dependent TCR downregulation was manually evaluated to further corroborate ongoing TCR signal transduction.

In peptide deconvolution analyses, peptide recognition was calculated by subtracting the background detected with DMSO-pulsed EBV-LCLs from the upregulation level of CD137 measured from the peptide-pulsed EBV-LCLs. When TCRs specific for individual peptides were identified, reactivity was validated and titrated using EBV-LCLs pulsed with increasing doses of pure peptides (from 100 to 108 pg/ml). For NeoAg-specific TCRs, titration was performed for both mutated and wild-type antigens. To define the recognition affinity for each TCR–peptide pair, results of titration curves were normalized, and EC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 software. Finally, HLA restriction of tumour-specific TCRs with identified specificity was determined by measuring the upregulation of CD137 upon stimulation with available monoallelic HLA lines5,35 (expressing HLAs from single patients) pulsed with the peptide of interest (Supplementary Methods).

Statistical analyses

The following statistical tests were used in this study, as indicated throughout the text: (1) Spearman’s correlation coefficients and associated two-sided P values were computed using R to test the null hypothesis that the correlation coefficient is zero (Fig. 1d). (2) Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test were performed in R to calculate the significance of deviation of a distribution from the null hypothesis of no differential distribution (Figs. 2c, 4a, Extended Data Fig. 7e). (3) Welch t-tests were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software to obtain the two-sided P value of the null hypothesis that the two groups have equal means (Fig. 4c). (4) Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed in R for data with high variance to test whether mean ranks differ (Extended Data Fig. 9d). (5) Ratio-paired parametric t-tests were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 software, to obtain the two-sided P value of the null hypothesis that the paired values of two groups have a ratio equal to 1 (Extended Data Fig. 9d-f). (6) Linear regressions were performed on log-transformed values of different parameters using GraphPad Prism 8 software, which provided R2 values and two-sided P values of the null hypothesis that the regression coefficient is zero (Fig. 3e). (7) Normalized Shannon index (normSI) was calculated on patient-specific TCRs or on all available TCR clonotypes as follows:

k is the number of TCR clonotypes, n is the total count of cells, f is frequency, and i indicates the rank of TCR clonotypes.

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Extended Data

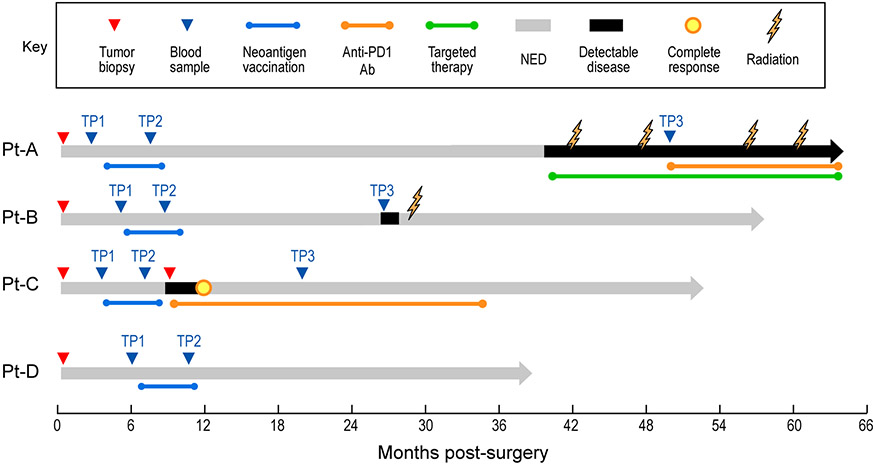

Extended Data Figure 1. Clinical course of melanoma patients analyzed for single-cell sequencing and TCR specificity.

Schematic representation of the clinical histories of the 4 melanoma patients profiled in this study. Triangles - time of collection of tumor biopsies (red) analyzed with single-cell sequencing or of peripheral blood samples (blue) used for isolation of tumor-reactive T cells at serial timepoints (TP). NED, no evidence of disease.

Extended Data Figure 2. Single-cell profiling of CD8 + tumor infiltrating lymphocytes.

a. Flow-cytometry plots quantifying the proportion of T lymphocytes (defined as CD45+ CD3+) infiltrating 5 tumor biopsies subjected to single-cell sequencing. Tissue origin for each tumor sample is indicated. b. Density plots identifying CD8+ TILs through CITEseq antibody signals for CD4+ (orange) and CD8+ (blue). Data are reported as CD4 and CD8 CITEseq signals relative to isotype controls for all sequenced cells that were identified as T cells after flow sorting and computational filtering. c. Size and patient distribution of the 13 clusters identified from CD8+ TIL scRNAseq. Left: per cluster, sample origin is denoted by color. The analyzed CD8+ dataset is predominantly composed by cells from 3 patients (Pt-A (green), Pt-C (red) and Pt-D (blue)). Two clusters were found to be patient-specific (clusters 8 and 11). Right: UMAPs depicting cluster distribution of patient-specific CD8+ TILs. d. Heatmaps depicting the mean cluster expression of a panel of T-cell related genes, measured by scRNAseq (left panel) and the mean surface expression of the corresponding proteins measured through CITEseq (right panel). Clusters (columns) are labelled using the annotation provided in Fig. 1b; markers (rows) are grouped based on their biological function. Grey - unevaluable markers (CD45 isoforms for scRNASeq) or which were not assessed (for CITESeq). CITESeq CD3 surface expression was poorly detected because of the presence of competing CD3 sorting antibody. e. Violin plots quantifying relative transcriptional expression of genes (columns) with high differential expression among CD8+ TIL clusters (rows). f. UMAPs depicting the single-cell expression of representative T cell markers among CD8+ TILs either through detection of surface protein expression with CITEseq (Ab), or through scRNAseq (RNA). g. Characterization of the CD8+ TIL clusters using independent reference gene-signatures8-10. Heatmaps show cross-labelling of T cell clusters defined in the present study (columns, reported as in Fig. 1b) versus reference gene-signatures (rows) derived from the analyses in Sade-Feldman et al.8, Yost et al.9 and Oh et al.10, with intensities indicating normalized frequency.

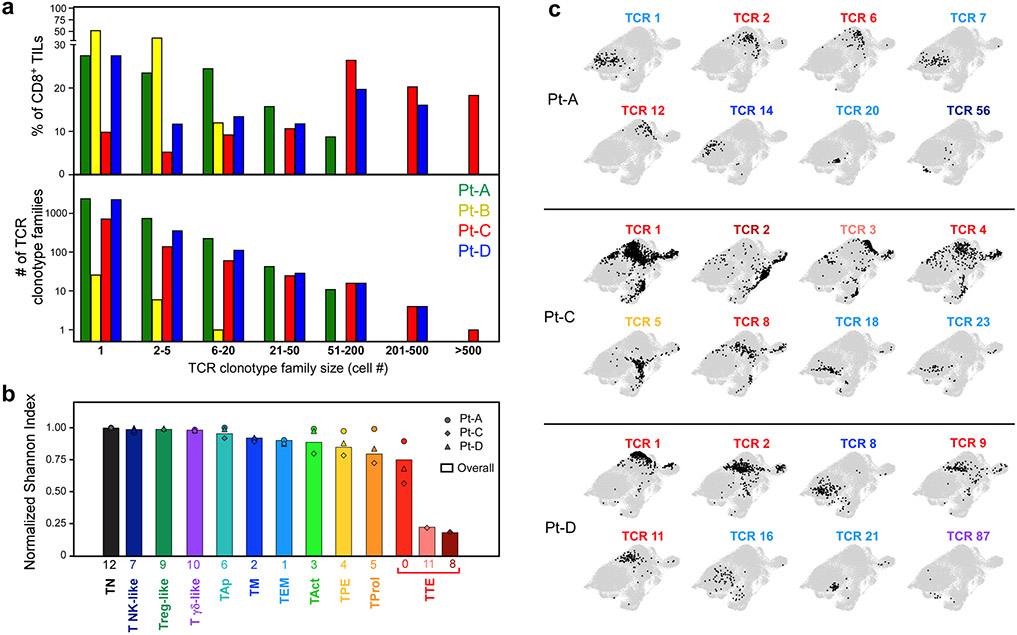

Extended Data Figure 3. Clonality of CD8+ TILs and cell states of TCR clonotypes.

a. Histograms depicting the number (bottom panel) and overall frequency (top panel) of patients’ TCR clonotype families divided in categories based on their size (x axis). b. Histograms showing the intra-cluster TCR clonality, calculated for CD8+ T cells in each cluster (x axis) using normalized Shannon index. Symbols - individual TCR clonality for the 3 patients with high numbers of TILs (Pt-A, Pt-C, Pt-D). Bars - the overall TCR clonality measured within each cluster. c. UMAPs of the cluster distribution of representative dominant TCR clonotype families among CD8+ TILs from TIL-rich patients (n=3). For each patient, numbers denote the ranking of each TCR clonotype (see Fig. 1c), while colors identify their primary cluster (see Fig. 1b).

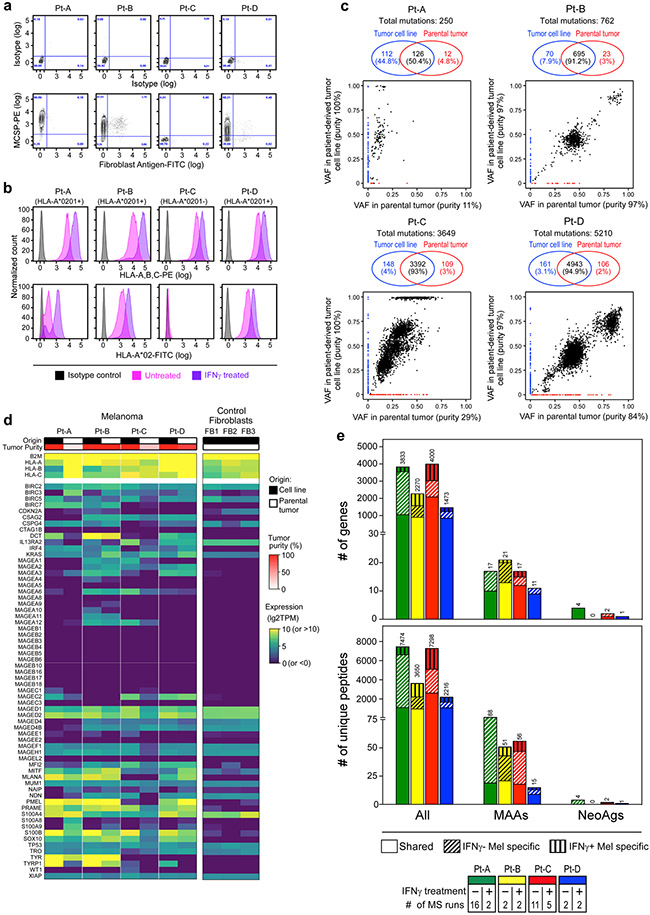

Extended Data Figure 4. Characterization of patient-derived melanoma cell lines.

a. Purity of tumor cultures, originating from patient biopsies, was assessed by flow-cytometry by staining cells with isotype controls (top panels) or surface markers (bottom panels) identifying melanoma (using melanoma chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan [MCSP], y axis) or fibroblast lineages (fibroblast antigen, x axis). Consistent with previous reports36, MCSP was expressed in 3 of 4 tumor cultures, with each lacking substantive fibroblast contamination. b. Flow-cytometric assessment of HLA class I surface expression on the established melanoma cell lines. Surface expression was measured with a pan-HLA class I antibody (top panels) or with an HLA-A:02-specific antibody (bottom panels) at basal culture conditions (magenta) or upon exposure to IFNγ for 72 hours (purple), compared to isotype control (grey). c. Comparison of the mutation burden of patient-derived melanoma cell lines vs. corresponding parental tumors. For all patients, mutation calling from WES of tumor biopsies and cell lines was performed through comparison with autologous PBMCs serving as germline controls. Venn diagrams - the numbers and frequencies of mutations unique to parental tumors (red) or melanoma cell lines (blue) or shared between the two (black). Corresponding dot plots, using the same color code, show the variant allele frequencies (VAF) of mutations detected in the parental tumors (x axis) and derived cell lines (y axis). For both, tumor purity inferred from single-cell data (parental tumors) or detected by flow-cytometry (cell lines) is indicated. The high concordance between the genomic mutations detected in paired specimens demonstrates that the melanoma cell lines are reflective of the corresponding parental tumors. d. Gene expression profiles of HLA class I genes and MAA genes in patient-derived cell lines (columns, black) or in matched parental tumors (columns, white), compared to control tumor-derived fibroblast cell lines (n=3) originating from unrelated melanoma biopsies (right columns). Tumor purity is reported in red. Gene expression was measured by RNA-seq and normalized as logarithmic transcripts per million base pairs (TPM). e. HLA class I immunopeptidome of patient-derived melanoma cell lines cultured with or without IFNγ. Bars - numbers of unique peptides detected by mass spectrometry (MS) after immunoprecipitation of peptide-HLA class I complexes (bottom panel), and of unique genes from which the detected peptides were derived (top panel), and grouped based on their origin from MAAs or NeoAgs and colored by patient. The number of MS acquisitions for each condition is indicated.

Extended Data Figure 5. Antitumor reactivity of in vitro reconstructed TCRs.

a. Schema for classification of TCR reactivities based on CD137 upregulation of TCR transduced T cell lines upon challenge with patient-derived melanoma cells (Mel, with or without IFNγ pre-treatment [red]) or controls (PBMCs, B cells and EBV-LCLs [blue]). A TCR was defined as tumor-specific if it recognized only the autologous melanoma cell line, but did not upregulate CD137 when challenged with autologous controls. b. Representative flow-cytometry plots depicting CD137 upregulation measured on CD8+ T cells transduced with TCRs isolated from Pt-A and cultured with melanoma or control targets. Background reactivity was estimated by measuring CD137 upregulation on CD8+ T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR. c. Cytotoxic potential provided by TCRs with exhausted (left) or non-exhausted (right) primary clusters isolated from all 4 studied patients. Degranulation (CD107a/b+) and concomitant production of cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2) were assessed through intracellular staining, gating on TCR-transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ T cells cultured alone or in the presence of autologous melanoma. Each dot represents the result for a single TCR isolated from CD8+ TILs, color-coded based to its primary phenotypic cluster (as defined in Fig. 1b). For each analyzed TCR, background cytotoxicity from CD8+ T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR was subtracted. White dots - basal level of activation of untransduced cells. Overall, these data indicate that antitumor cytotoxicity mainly resides among TCR clonotypes with exhausted primary clusters.

Extended Data Figure 6. Isolation, single-cell sequencing and screening of tumor-reactive TCRs from peripheral blood samples.

a-b. PBMCs harvested at serial timepoints (TP1, TP1, TP3; see Extended Data Fig. 1) were cultured with autologous melanoma cell lines to enrich for antitumor TCRs. After two rounds of stimulation, the reactivity of effector CD8+ T cells was assessed by measuring: (a) degranulation and cytokine production; or (b) CD137 upregulation upon re-challenge with melanoma (blue line). The specificity of the response was supported by the low recognition of HLA-mismatched unrelated melanoma (dashed grey line). Negative controls (cultured in the absence of target cells) and positive controls (polyclonal stimulators, PHA or PMA-ionomycin) are displayed as solid grey and black lines, respectively. c. FACS sorting strategy for the isolation of tumor-reactive T cells. CD8+ effectors with active degranulation and concomitant cytokine production were identified using cytokine secretion assays (see Supplementary Methods) upon stimulation without any target (top panel) or in the presence of autologous melanoma (bottom panels). CD107a/b+ cells secreting at least one of the measured cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2) were single-cell sorted and sequenced. Gates depict the detection and quantification of reactive (black) or sorted cells (magenta) from a representative sample (TP3 PBMCs from Pt-A). d. TCR clonotypes identified upon single-cell sorting and scTCRseq of melanoma-reactive CD8+ T cells from the 4 studied patients. Bars - cell counts of clonotype families, defined as CD8+ cells bearing identical TCRα and TCRβ chains, divided based on their detection at specific timepoints (TP1, TP2, TP3) or across multiple timepoints (shared). Presence of multiple TCRα or TCRβ chains is indicated with black or orange borders, respectively. e-h. TCRs isolated and sequenced from anti-melanoma cultures were reconstructed, expressed in CD8+ T cells and screened against melanoma (Mel, with or without IFNγ pre-treatment in red) or controls (PBMCs, B cells and EBV-LCLs in blue). TCRs were classified as reported in Extended Data Fig. 5a, to identify: (e) tumor-specific TCRs, (f) non-tumor reactive TCRs, and (g) tumor/control reactive TCRs. Reactivity was calculated by subtracting from CD137 expression of CD8+ cells transduced with the reconstructed TCR the background of lymphocytes transduced with an irrelevant TCR. Floating boxes show min to max measurements, with mean values depicted as horizontal lines; white dots denote the basal level of activation measured on untransduced cells. Pie charts in h summarize the classification of TCR reactivity for all reconstructed TCRs. i. Cytotoxicity mediated by TCRs classified as tumor-specific (left panel), non-tumor reactive (middle panel) or tumor/control reactive (right panel). Degranulation (CD107a/b+) and concomitant production of cytokines (IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2) were measured through intracellular flow-cytometry on TCR transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ T cells cultured alone or in the presence of autologous melanoma. Each dot represents the results of a single TCR isolated from CD8+ TILs (upon subtraction of background activation measured on CD8+ lymphocytes transduced with an irrelevant TCR). White dots denote the basal level of cytotoxicity of untransduced cells. j. Bar plots showing intratumoral cluster distribution of cells bearing tumor-specific (left) or non-tumor reactive (right) TCRs isolated from blood and traced within the tumor microenvironment (see Fig. 2e). For each patient, numbers denote the ranking of each TCR among top 100 clonotype families (see Fig. 1c), while colors identify their primary cluster (see Fig. 1b).

Extended Data Figure 7. Cell states of tumor-specific CD8+ TILs.

a-c. Antigen specificity screening of 94 TCRs sequenced from clonally expanded CD8+ T cells isolated from tumor biopsies of 7 patients with metastatic melanoma from Sade-Feldman et al8. a. After TCR reconstruction and expression in T cells, reactivity was measured as CD137 upregulation on TCR-transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ cells upon culture with autologous EBV-LCLs pulsed with peptide pools covering immunogenic viral epitopes (CEF). Unstimulated cells were analyzed as negative control. Results are reported after subtraction of background CD137 expression on T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR. Five TCRs (black dots) recognized unpulsed EBV-LCLs, thereby documenting specificity for EBV epitopes. b. TCR antitumor reactivity, evaluated upon culture with autologous EBV-LCLs pulsed with peptide pools derived from 12 known MAAs. Background detected upon culture with DMSO-pulsed EBV-LCLs was subtracted. Additional positive and negative controls were an irrelevant peptide (Ova) and polyclonal stimulators (PHA or PMA/ionomycin), respectively. Colored dots denote MAA-reactive TCRs. c. Table summarizing patient distribution of TCR specificities either discovered from reconstruction and screening of 94 TCRs or present within a database of human TCRs with known specificities (TCRdb12). d-e-f. Single-cell phenotype of TILs with antiviral or anti-MAA TCRs identified in the validation cohort from Sade-Feldman et al8. d. t-SNE plot of CD8+ TILs highlighting the spatial distribution of cells harboring TCRs with identified antigen specificity. Each color denotes a distinct specificity, with crosses representing two cells with identical spatial coordinates. e. Pie charts summarizing the assignment of single cells harboring antiviral (top) or anti-MAA (bottom) TCRs to one of the previously reported 6 clusters8. f. RNA transcripts differentially expressed between antiviral and anti-MAA cells (log2FC>1.5, adj. p value<0.05). The heatmap reports Z scores, calculated from average gene expression of each TCR clonotype family (columns). Antigen specificity is reported on top with the same color-code as in d. g-h. Analysis of deregulated genes in exhausted clusters (TEx), enriched in tumor-reactive T cells, from the discovery cohort. g. Average gene expression, reported as Z scores, for each TCR clonotype family (columns) validated in vitro as tumor-specific (orange, 134 TCRs) or defined as virus-specific (black, 17 TCRs). The heatmap reports 98 RNA transcripts (adjPval<0.0001, log2FC>1) and 6 surface proteins (bottom rows, adjPval<0.0001, log2FC>0.4) detected trough scRNAseq and CITEseq respectively. h. Plots depicting expression of representative RNA-transcripts (top) or surface proteins (bottom) in each TCR clonotype family with antiviral (black) or antitumor (orange) specificity. Dots depict the average gene-expression in each TCR clonotype, with size proportional to the frequency of the TCR clonotype within patient-specific CD8+ TILs. i. Heatmap depicting the top 20 overexpressed genes in each TS-cluster of tumor-specific (TS) CD8+ cells (columns). Z scores of gene expression among 5 subpopulations are shown. Genes important for the classification of each subset are highlighted in blue. j. Heatmaps depicting expression of a panel of T cell related transcripts detected through scRNAseq (left) or surface proteins detected through CITEseq (right). Z scores document the trends in expression among subpopulations of TS CD8+ cells (columns). k. Enrichment in expression of gene-signatures among identified clusters of TS CD8+ cells (columns). Single cells with tumor-specific TCRs were divided in clusters as reported in Fig. 2f, and scored for the expression of gene-signatures defined from analysis of CD8 TILs of the discovery cohort (left), reported in external datasets of sequenced human CD8+ TILs (middle), or defined from published murine studies (right) (see Methods and Supplementary Table 8). Average enrichment score was calculated for each cluster and reported as Z score.

Extended Data Figure 8. Antigen specificity of tumor-reactive TCRs.

a. Antitumor TCRs isolated from HLA-A*02:01+ patients (Pt-A, Pt-B and Pt-D) were tested for the ability to cross-recognize allogeneic HLA-A*02:01+ melanomas. Melanoma reactivity was measured as CD137 upregulation on TCR-transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ cells upon culture with autologous or allogeneic HLA-A*02:01-matched melanomas. Tumor specificity was ruled out through parallel detection of CD137 upregulation upon challenge with matched non-tumor controls (PBMCs). Floating boxes show min to max measurements, with mean values denoted by horizontal lines. All results are shown after subtraction of background CD137 expression on T cells transduced with an irrelevant TCR; white dots denote the basal level of activation of untransduced CD8+ T cells. Pt-A and Pt-B displayed high melanoma-specific (i.e. lack of recognition of autologous PBMCs) cross-reactivity indicating that a substantial proportion of antitumor TCRs recognize public HLA-A*02:01-restricted melanoma antigens. b-c. Antigen specificity screening of 299 antitumor TCRs. Upregulation of CD137 was assessed by flow-cytometry on CD8+ T cells transduced with previously identified tumor-specific TCRs upon culture with autologous EBV-LCLs. Background, assessed using DMSO-pulsed target cells, was subtracted from each condition. b. Antigen recognition tested with pools of peptides corresponding to predicted immunogenic NeoAgs (see Supplementary Table 9), known MAAs (see Supplementary Table 10) or immunogenic viral epitopes. Reactivity was also assessed against an irrelevant peptide (Ova) or in the presence of polyclonal stimulators (PHA or PMA/ionomycin) as negative and positive controls, respectively. Black dots - activation levels of a control Flu-specific HLA-A*02:01-restricted TCR. Colored dots – confirmed antigen-reactive TCRs, colored based on highest reactivity against a particular antigens, as per the legend, compared to the other tested antigens; white dots –TCRs reactive against an antigen which was not the highest of the panel of antigens tested, and hence considered a cross-reactive response; grey dots - negative responses. Deconvolution of antigen specificity of TCRs reactive to NeoAg-peptide pools is reported in Supplementary Information – Flow-cytometry data. c. Antigen specificity tested using NeoAg or MAA-peptides detected by HLA-class I mass spectrometry (MS) immunopeptidome of melanoma cell lines (see Supplementary Table 9-10) with the addition of the MLANA protein (not retrieved by MS but known as highly immunogenic34). Colored dots -confirmed antigen-reactive TCRs, colored based on highest reactivity against a particular antigens (color legend reported in d), compared to the other tested antigens; white dots –TCRs reactive against an antigen which was not the highest of the panel of antigens tested, and hence considered a cross-reactive response; d. Distribution of antigen specificities of antitumor TCRs per patient successfully deorphanized after screening. Colors denote the distinct peptides recognized by individual antitumor TCRs. Note that TCRs classified as specific for antigenic pools (n=11) represent CD8-restricted specificities showing reactivity against peptide pools (b), but not towards single peptides (c), likely due to the absence of the specific cognate antigen within the tested panels of epitopes in c.

Extended Data Figure 9. Phenotype of MAA/NeoAg-TCRs and parameters affecting their avidity.

a. Heatmap showing genes differentially expressed between CD8+ TILs with identified MAA, NeoAg or virus-specific TCRs. Comparisons were performed independently for each patient, and only significantly deregulated genes (adj-pval<0.05, log2FC>1 for scRNAseq data; log2FC>0.4 for CITEseq data) in at least 2 out of 4 patients were selected. No deregulated gene was found upon comparison of single-cells with MAA or NeoAg-TCRs; 60 RNA transcripts and 2 surface proteins resulted from comparison of MAA and/or NeoAg cells vs viral cells. Heatmap colors depict Z scores of average gene expression within a TCR clonotype (columns). Top tracks: annotations of antigen specificity (color legend reported in panel b), normalized antitumor TCR reactivity, TCR avidity and patient of origin. b. To define the avidity of antitumor TCRs, TCR-dependent CD137 upregulation was measured on TCR-transduced (mTRBC+) CD8+ cells upon culture with patient-derived EBV-LCLs pulsed with increasing concentrations of the cognate antigen (MAAs in the top panel, NeoAgs in bottom panels). Reactivity to DMSO-pulsed targets (0) and autologous melanoma (pdMel-CL) are reported on the right; for NeoAg-specific TCRs, the dashed lines report reactivity against wildtype peptides. A color legend depicts the different cognate antigens targeted by the deorphanized TCRs and specifies the number of TCRs specific for each antigenic specificity. c. EC50 calculated from titration curves: note that high EC50 values correspond to low TCR avidities. Means with SD are reported, with TCR numbers corresponding to that reported in the legend of b. Most of the NeoAg-specific TCRs display higher avidities than MAA-specific TCRs. d. Expression levels of MAA or NeoAg transcripts (from bulk RNA-seq data) from which the analyzed epitopes are generated, as a measure of cognate peptide abundance in tumor cells, as analyzed from 4 patient-derived cell lines (symbols). Columns show means values with SD. e. Assessment of the affinity (left) and stability (right) of peptide:HLA complexes. The interactions between reported MAA or NeoAg peptides and their HLA restriction (assessed in vitro as shown in Supplementary Information – Flow-cytometry data) were measured as previously described37. Note that high values correspond to low affinity (left), or to stable interactions (right). Columns report mean affinity/stability with standard deviations from repeated measurements; numbers of replicates is indicated at columns’ bases. Horizontal grey lines - affinity levels of reference peptides reported to be strong binders for the analyzed HLA alleles that were tested in parallel.

In all NeoAg panels, comparisons of mutant (Mut, colored bars) vs. wildtype (WT, white bars) peptides were performed using two-tailed ratio-paired parametric t-tests, and p values are reported. ND: not detectable; NB: non-binding; na: not assessed; ne: not evaluable.

Extended Data Figure 10. Peripheral blood dynamics of intratumoral T cell specificities.

a. Peripheral blood dynamics of T cells harboring TCRs with in vitro defined antigen specificity (Black: virus-specific TCRs; red: MAA-specific TCRs; green: NeoAg-specific TCRs). TCRs were quantified through bulk sequencing of TCRβ-chains of sorted CD3+ T cells from serial peripheral blood sampling of the 4 melanoma patients within the discovery cohort. Numbers report the median number of TCRs detected longitudinally out of the total number of TCRs within each category. b-d. CD8+ TCR clonotypes identified in CD8+ TILs were traced within serial peripheral blood samples harvested from an independent cohort of melanoma patients (n=14) treated with immune checkpoint blockade therapies and with available scRNASeq data generated from TILs8. TCRs were classified as exhausted (red) or non-exhausted (blue) based on their phenotypic primary cluster assessed by scRNAseq. Quantification of circulating TCR clonotypes was performed through bulk sequencing of TCRβ chains on circulating CD3+ cells and reported as percentage of total TCR sequences detected. Patient clinical outcomes were grouped as: survivors who did not experienced post-therapy disease recurrence (panel b, n=4); survivors who experienced disease progression after immunotherapy (panel c, n=3); and deceased patients (panel d, n=7).

Per patient, a schematic representation of clinical timeline and sample collection is depicted atop each panel. “ND”: not detected; “NED”: no evidence of disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for expert assistance from O. Olive and K. Shetty from the DFCI Center for Personal Cancer Vaccines; M. Manos and M. Severgnini and the staff of the DFCI Center for Immuno-Oncology (CIO); S. Pollock and C. Patterson (the Broad Institute’s Biological Samples, Genetic Analysis, and Genome Sequencing Platform) for their help in sample collection and management; and D. Braun, S. Gohil, S. Sarkizova and all of the members of the Wu laboratory for productive discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This research was made possible by a generous gift from the Blavatnik Family Foundation, and was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NCI- 1R01CA155010 and NCI-U24CA224331 to C.J.W.; NIH/NCI R21 CA216772-01A1 and NCI-SPORE- 2P50CA101942-11A1 to D.B.K.; NCI-1R01CA229261-01 to P.A.O.; NIH/NCI P01CA229092 and NIH/NIAID U19 AI082630 to K.J.L.; NCI R50CA211482-01 to S.A.S.; NCI R50CA251956 to S.L.; and R01 CA208756 to N.H.) and a Team Science Award from the Melanoma Research Alliance (to C.J.W., P.A.O. and K.J.L.). G.O. was supported by the American Italian Cancer Foundation fellowship. This work was further supported by The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation, and the Bridge Project, a partnership between the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03704-y.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis included the Broad Institute Picard Pipeline (for whole-exome sequencing/RNA-seq), GATK4 v4.0, Mutect2 v2.7.0 (for single-nucleotide variant and indel identification), NetM- HCpan 4.0 (for NeoAg-binding prediction), ContEst (for contamination estimation), ABSOLUTE v1.1 (for purity/ploidy estimation), STAR v2.6.1c (for sequencing alignment), RSEM v1.3.1 (for gene expression quantification), Seurat v3.2.0 (for single-cell sequencing analysis), Harmony v1.0 (for single-cell data normalization), SingleR v3.22, Scanpy v1.5.1 and Python v3.7.4 (for comparison with other single-cell datasets), which are each publicly available. The computer code used to generate the analyses is available at https://github.com/kstromhaug/oliveira-stromhaug-melanoma-tcrs-phenotypes.