Summary

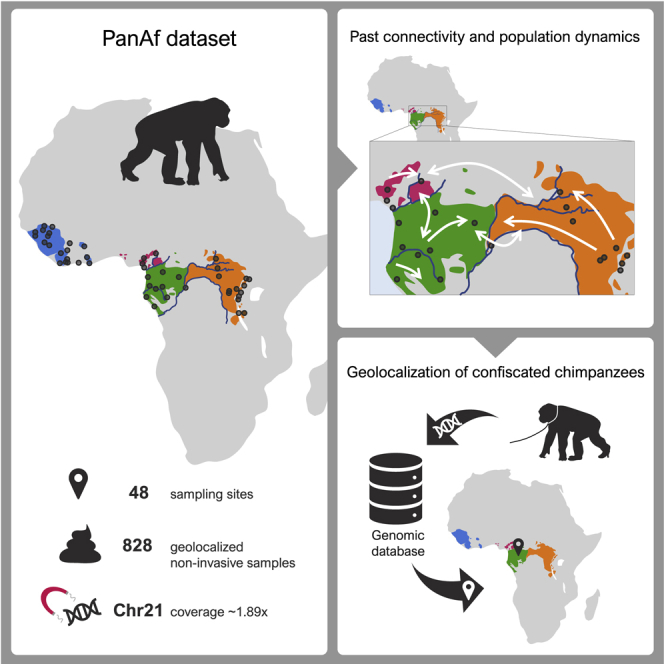

Knowledge on the population history of endangered species is critical for conservation, but whole-genome data on chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) is geographically sparse. Here, we produced the first non-invasive geolocalized catalog of genomic diversity by capturing chromosome 21 from 828 non-invasive samples collected at 48 sampling sites across Africa. The four recognized subspecies show clear genetic differentiation correlating with known barriers, while previously undescribed genetic exchange suggests that these have been permeable on a local scale. We obtained a detailed reconstruction of population stratification and fine-scale patterns of isolation, migration, and connectivity, including a comprehensive picture of admixture with bonobos (Pan paniscus). Unlike humans, chimpanzees did not experience extended episodes of long-distance migrations, which might have limited cultural transmission. Finally, based on local rare variation, we implement a fine-grained geolocalization approach demonstrating improved precision in determining the origin of confiscated chimpanzees.

Keywords: chimpanzee, non-invasive samples, fecal samples, hybridization capture, population genetics, conservation genomics, geolocalization, population dynamics, chimpanzee demography

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Chromosome 21 capture of geolocalized non-invasive chimpanzee samples

-

•

Support for four differentiated subspecies with local population structure

-

•

Fine-scale description of gene flow barriers and corridors since Late Pleistocene

-

•

Power to infer geographical origin of confiscated chimpanzees

Fontsere et al. captured and sequenced chromosome 21 from 828 non-invasively collected chimpanzee samples, providing an extensive catalog of genomic diversity for wild chimpanzee populations. The authors describe patterns of isolation and connectivity between localities and implement a fine-grained geolocalization approach to infer the origin of confiscated chimpanzees.

Introduction

Genetic data on chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) populations have been used to study the species’ diversity and population structure, as well as to characterize their demographic history and patterns of admixture at a broad subspecies level1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and with their sister species, bonobos (Pan paniscus).6,8 Due to a limited fossil record and absence of ancient DNA record, chimpanzee population genetics is inherently restricted to modern-day individuals.9

Four chimpanzee subspecies are currently recognized (western -P. t. verus-, Nigeria-Cameroon -P. t. ellioti-, central -P. t. troglodytes-, and eastern -P. t. schweinfurthii-, Figure 1A) but conflicting hypotheses still exist about whether genetic diversity in central and eastern chimpanzee populations reflects two distinctly separated subspecies,6 or a cline of variation under isolation-by-distance.1,10,11 This long-standing question also relates to the degree of connectivity among subspecies over time, which requires a fine-scaled reconstruction of the demographic history of chimpanzee populations after their split more than ∼100 thousand years ago (kya)6 and their inter-connectivity since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Identifying genetic connections between present-day chimpanzee communities and the role of past environmental change in shaping these12,13 may be linked to behavioral variation in chimpanzee communities,14 similar to what has been explored extensively in humans as a strongly migratory species.15 Also, it will provide crucial tools for the development of conservation strategies for an endangered species that has suffered a dramatic decline in the last decades.16,17 A comprehensive genomic knowledge of a threatened species18 can guide conservation plans both in situ and ex situ.19 Furthermore, genetic information has proven useful to infer the populations of origin of confiscated individuals from illegal trade, detect poaching hotspots,20,21 and guide repatriation planning.22,23

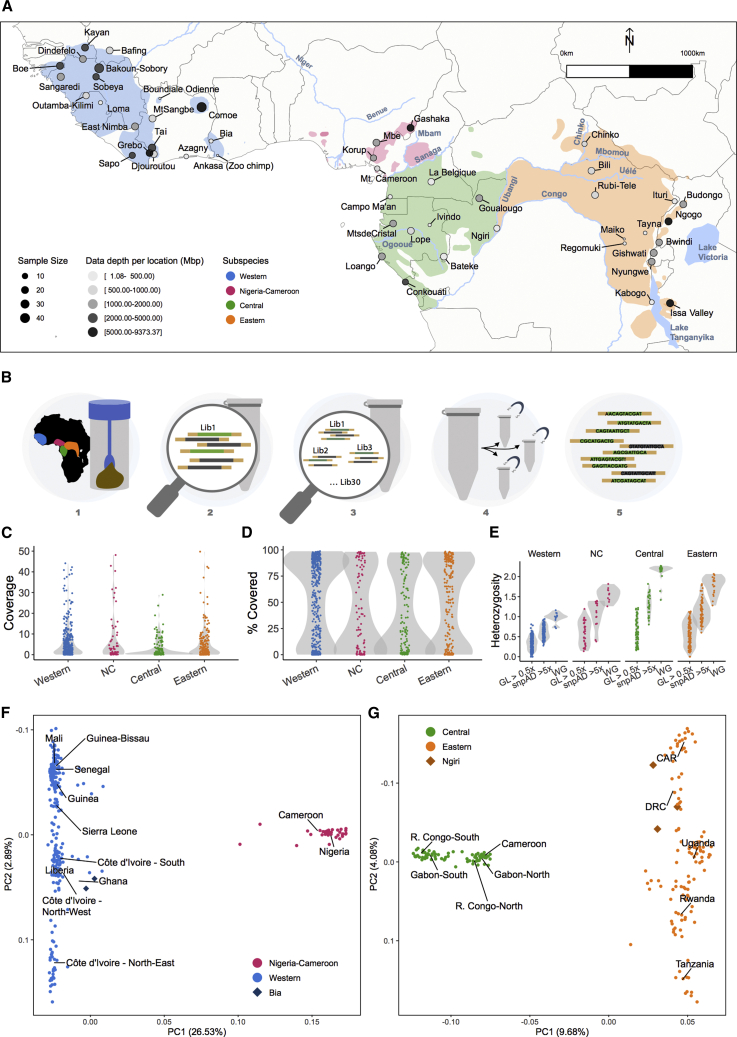

Figure 1.

Overview on sampling, capture, and chimpanzee population history

(A) Geographic distribution of chimpanzee subspecies and PanAf sampling locations. The western chimpanzee range is shown in blue, Nigeria-Cameroon in pink, central in green, and eastern in orange. The size of the dots represents the number of sequenced samples (n = 828) and color intensity represents the amount of chimpanzee genetic data generated (mega-base pairs of mapped sequence) from each sampling site.

(B) Experimental pipeline. (1) Samples were collected from 48 sampling sites, DNA extracted and screened for amplification success, uniqueness, and relatedness using microsatellites;11 (2) one library per individual24 was prepared; (3) between 10 and 30 libraries were pooled equi-endogenously;25 (4) enrichment for chromosome 21 with target capture methods, between three and five times per library;25 (5) sequencing data were generated with Illumina.

(C) Average coverage on the target region of chromosome 21 for each sample.

(D) Percentage of the target space covered by at least one read.

(E) Heterozygosity estimates per subspecies derived from ANGSD genotype likelihood on PanAf samples with more than 0.5-fold coverage (GL > 0.5×), from snpAD genotype calls on PanAf samples with more than 5-fold coverage, and from GATK genotype calls on previously published whole-genome (WG) chimpanzee samples.6

(F) PCA of western (blue) and Nigeria-Cameroon (pink) chimpanzee subspecies. Dark blue diamonds, Bia sampling site in Ghana at the eastern fringe of the extant western chimpanzee range.

(G) PCA of central (green) and eastern (orange) chimpanzee subspecies. Dark orange diamonds, Ngiri sampling site at the western fringe of the eastern chimpanzee distribution. CAR, Central African Republic; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo; R. Congo, Republic of Congo. See also Figures S3–S13, S29–S39, and Table S4

For a detailed reconstruction of chimpanzee population structure and demographic history, it is crucial to gather data from a large number of individuals covering the current range of the species and of sufficient data depth. Since practical and ethical concerns impede the collection of blood samples from wild ape populations, non-invasive samples, such as feces,26,27 are a promising alternative, although low quality and quantities of host DNA (hDNA)27 have typically precluded population data analysis using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). However, in the last years, several technical advances in target capture methods have allowed the use of non-invasive samples in large-scale genomic studies.25, 27, 28, 29 Here, we take advantage of these advances to generate an extensive dataset on genomic variation in georeferenced chimpanzees to infer their demographic history and develop a tool for the geolocation of chimpanzee samples.

Results

Capturing the diversity of wild chimpanzees

A total of 828 unique individuals were identified from non-invasive samples collected from 48 sampling sites across the chimpanzee range (Figure 1A) as part of the PanAfrican Program: The Cultured Chimpanzee.11 Using previously developed methods, we captured chromosome 21 from chimpanzee fecal DNA11,25, 28, 29 (Figure 1B) and generated sequencing data to a median coverage of 1.89-fold (0- to 90.14-fold) in the target space (Figure 1C), covering on average 12.9 million positions per sample (STAR Methods; Notes S1 and S2; Table S1).

Numerous samples have high levels of sequencing reads mapping to other primate species than chimpanzee (n = 100, Figures S9, S10, S14, and S15; Note S3), likely due to the inclusion of sympatric primate species in the diet, a well-known phenomenon,30,31 or sample misidentification during collection of feces.11,32 We also assessed human contamination among the remaining 728 samples using an approach very sensitive in low-coverage data,33 finding 36 of those with more than 1% of such contamination (Figure S16). This is similar to patterns of contamination observed in ancient DNA studies on humans.34 There is also large variation in coverage and hDNA content according to the sampling site, suggesting that environmental and/or dietary factors influence DNA quantity and preservation (Figures 1C, 1D, S4, and S7). Heterozygosity estimates, after careful quality assessment (Figures S21–S29; Note S3), are consistent with known patterns from high-coverage samples:3,6 highest in central chimpanzees, followed by eastern, Nigeria-Cameroon, and western chimpanzee subspecies (Figure 1E).

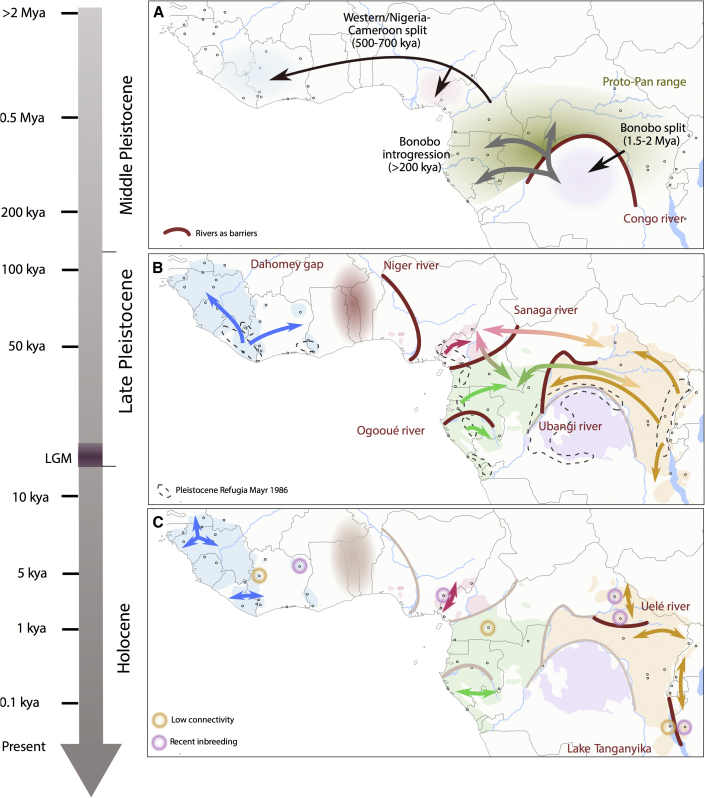

The history of Pan populations during the Middle Pleistocene

We deemed samples with more than 0.5-fold average coverage (on the target regions of chr21) and low levels of contamination to be of sufficient data depth and quality (n = 555) (Figures S9–S13; Note S3) for a PCA from genotype likelihoods,35,36 and found that these cluster according to the four described subspecies (Figures 1F, 1G, and S13) that were previously estimated to have diverged during the Middle Pleistocene (139–633 kya), after the split from bonobos (<2 million years ago [mya]) (Figure 2A).6 Low levels of ancient introgression from bonobos into the non-western chimpanzee subspecies (<1%) had previously been identified, most likely as the result of bonobo admixture into the ancestral population of eastern and central chimpanzees more than 200 kya6,37 (Figure 2A), possibly associated with a reduction of the Congo River discharge, the natural barrier separating both species.38 On chromosome 21, we did not observe a significant enrichment of allele sharing (F statistics)39 between bonobos and chimpanzees, likely due to limitations in the data, a small extent of admixture, and the small number of independent loci (Note S8). However, given the information from previous models based on whole genomes, we sought to determine introgressed fragments on chromosome 21 with the larger number of individuals used in this study. To this end, we inferred bonobo introgression using admixfrog,40 a method developed to reliably detect introgressed fragments even in low-coverage ancient genomes. With this hidden Markov model we inferred local ancestry for each sample (target) using different sources, which represent the admixing population (bonobo and all chimpanzee subspecies) from the reference panel6 (STAR Methods; Note S8). We found that all central chimpanzee communities sampled south of the Ogooué River (Figure 2A) (Loango, Lopé, Conkouati, and Batéké) harbor significantly more bonobo-like genomic fragments than those north of the river (two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p value = 5.735 × 10−8), or any other chimpanzee population (adjusted p value < 0.01; Figure S64; Table S5; Note S8), with some of the individuals from the Lopé and Loango sampling sites showing the highest bonobo ancestry (Figure S64). These fragments are also longer than in other chimpanzee populations (Table S5; Figure S66J), which may hint at a separate, more recent admixture event, although this observation was not significant (two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

Figure 2.

Reconstruction of chimpanzee genetic history

Major rivers and lakes (red lines) and the Dahomey gap (red shading) represent geographical barriers separating populations at different timescales.

(A) Formation of and migration between Pan species (chimpanzees and bonobos) and subspecies formation during the Middle Pleistocene; separation and migration events inferred in previous studies,6,8,38 additional gene flow into southern central populations was inferred here using admixfrog.

(B) Corridors of gene flow (arrows) during the Late Pleistocene and after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), when chimpanzee populations expanded from refugia;12,14 within subspecies based on migration surfaces obtained with EEMS and shared rare variation, between subspecies based on short IBD-like tracts (<0.5 Mbp) and shared fragments of ancestry inferred with admixfrog.

(C) Population connectivity and isolation during the Holocene; connectivity was determined by long (>0.5 Mbp) IBD-like fragments between sampling locations within subspecies and supported by presence or absence of shared rare variation; signatures of recent inbreeding are represented by long regions of homozygosity in individuals from a given sampling location. See also Figures S40–S53, S57–S60, S64, S66, S76–S79, S82–S85, and S92.

Within chimpanzees, our dense sampling approach, including communities at the border between subspecies (eastern Ngiri in DRC, on the eastern bank of the Ubangi River) and thousands of markers (Table S1), allows us to assess the relationship between central and eastern chimpanzee subspecies. Despite Ngiri being geographically closer to Goualougo (a central chimpanzee sampling site, ∼280 km) than to any eastern chimpanzee location in our dataset (Rubi-Télé, ∼845 km, and Bili, ∼900 km) (Figure 1A), individuals from Ngiri clearly fall within the genetic diversity of eastern chimpanzees in the PCA (Figures 1G and S33), pointing to a clear long-term separation of these subspecies. These findings support an unequivocal separation of central and eastern chimpanzee subspecies over a large evolutionary time. However, subsequent recent interbreeding has been suggested by other studies.6,11

Long-term subspecies differentiation and genetic exchange during the Late Pleistocene

The sustained genetic differentiation of chimpanzee subspecies can be interpreted in the context of geographical barriers impeding gene flow, especially the major rivers in tropical Africa.41 We applied the EEMS method42 to analyze long-term migration landscapes during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene43 (Figures 2B and S82). We found evidence for regions of reduced effective migration that overlap with geographic barriers, such as the Sanaga River (separating Nigeria-Cameroon and central chimpanzees) and the Ubangi River (separating central and eastern chimpanzees) (Figures 2B and S82; Note S10). These patterns of stratification and shared drift were also supported by FST and f3 statistics (Figures S45, and S54; Notes S6 and S7).

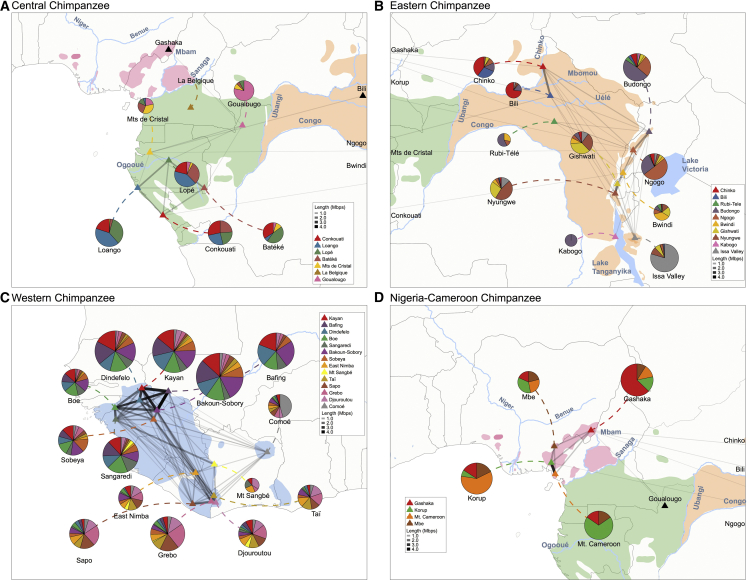

Previous evidence suggested that some chimpanzee subspecies have not been fully isolated since their separation, but rather experienced migration events.3,6,11,44 To analyze the permeability of subspecies barriers to gene flow, we used two methods designed to capture signatures of gene flow at different timescales. First, we used identical-by-descent-like (IBD-like) segments detected between individuals from different subspecies using IBDseq,45 i.e., regions of the chromosome where two individuals share variation. Since the detected segments are smaller than 0.5 mega-base pairs (Mbp) between subspecies, they represent genetic exchange that happened more than approximately 5 kya, assuming an exponential decay of fragment length due to recombination (STAR Methods; Note S10; Figure S89; Table S7). Second, we inferred shorter introgressed fragments between chimpanzee subspecies with the aforementioned method admixfrog,40 using four genomes of each chimpanzee subspecies from the reference panel as sources6 to partition genomic regions into the subspecies state they resemble most (STAR Methods; Note S8). We found evidence of gene flow between the central, eastern, and Nigeria-Cameroon subspecies with both methods (Figures 2B, 3, and S66; Table S7), indicating low levels of genetic exchange at different timescales despite their long-term separation. We observed that Nigeria-Cameroon Gashaka individuals carry more fragments of central and eastern chimpanzee ancestry than other Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees, while the central Goualougo individuals carry more eastern and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee fragments than the other central communities (Figure S66). This indicates gene flow between these local populations, which is also supported by an analysis of shared rare alleles, which are likely to have emerged more recently46 and whose sharing patterns are informative on recent admixture (Figures S76, and S77; Note S9). The observation of a northern area of past genetic exchange between the three subspecies is broadly consistent with conclusions from microsatellite data,11 and with previous studies suggesting a hybrid zone between central and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees in central Cameroon.44,47

Figure 3.

Recent connectivity between chimpanzee populations

(A–D) The size of the pie charts represents the pairwise number of shared fragments, normalized by the number of pairs. Thickness of lines indicates the average length of IBD-like tracts (in Mbp). Triangles show the location of sites. Colors in pies indicate the origin of IBD-like tracts, including comparison between samples from the same site. (A) Central chimpanzees, (B) eastern chimpanzees, (C) western chimpanzees, and (D) Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees. Note also few and short IBD-like fragment connections between central, eastern, and Nigeria-Cameroon subspecies. See also Figures S86–S94.

Recent history between communities since the LGM

Local population stratification within subspecies, probably arising during the Late Pleistocene, has been partially explored previously for eastern and central chimpanzees using whole genomes, but with a much smaller sample size and sampling density.6 Here, for the first time, we can explore the fine-scale population structure and recent connectivity across the whole geographic range since the LGM and into the Holocene for all subspecies, partially down to the specific site level (Figure S31). To do this, we combine information from different methods that can specifically identify connectivity and isolation at different timescales, specifically EEMS42 (more than 6 kya), shared rare alleles (∼1.5–15 kya, Note S9),48 long (>0.5 Mbp) IBD-like tracts shared between communities of the same subspecies (less than 5 kya; please see more on possible caveats to this approach in the Limitations of the study and Note S10),49 as well as recent inbreeding with regions of homozygosity (RoH) (Figures S40–S42; Note S6). This yields a comprehensive and detailed picture of genetic connectivity across the chimpanzee range and within subspecies, beyond the broad genetic clines in eastern and western chimpanzees (Figures 1F, 1G, and S31–S34; Note S5).

Overall, western chimpanzees exhibit higher levels of connectivity across their range and across timescales than the other subspecies, as detected with IBD-like shared fragments, rare variation, and EEMS (Figures 2B, 2C, 3C, S79, S82, and S84; Note S10). Remarkably, for the same geographic distances, western chimpanzee sampling sites share more and longer IBD-like tracts than the other subspecies (Figures 3C and S90), especially within their northern range (Senegal, Mali, northern Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau). Also, shared rare variation resembles the results from IBD-like shared fragments (Figure S79). It is important to note that western chimpanzees have the lowest diversity and likely suffered a strong bottleneck,6 so our results could support two different scenarios: either high levels of recent connectivity between persisting populations during the past ∼780 years (according to the IBD-like tract length; range 117–2,200 years) (Table S9), or a range expansion into the fringe areas of the chimpanzee habitat within the same time frame, resulting in a very recent separation of these populations50 (Figure 2C). However, at this stage we cannot distinguish these scenarios based on genetic data only. All four sampling sites of Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees seem to have been connected within the past 2,500 years (mean 1,600 until 1,000 years ago), indicated by both IBD-like segments and rare allele connectivity (Figures 3D and S77; Note S9). Furthermore, a signature of recent inbreeding in Mbe (i.e., long RoH) suggests that this population was strongly isolated only very recently51 (Figure S40).

Eastern chimpanzee sampling sites largely follow a pattern of isolation-by-distance, shown as an exponential decay of IBD-like fragment length (Figure S90) along a genetic North-South cline also found in the PCA (Figure 1G). However, we observed three clusters of recent connectivity reflected in a higher number and longer IBD-like segments (Figure 3B, thicker lines between Chinko-Bili, Budongo-Ngogo, and Gishwati-Nyungwe). Also, the Uéle River and Lake Tanganyika likely acted as isolation barriers in eastern chimpanzee populations in recent times, which is supported by IBD-like segments and shared rare variation (Figures 2C, 3B, S76–S79, and S92; Table S3; Notes S9 and S10). Dispersal corridors suggested for populations in western Uganda52 and between western Uganda and the eastern DRC53 (Figure 2B) are supported by these types of analyses (Figures 3B and S78). Finally, all eastern chimpanzee populations share rare variation with those communities living in the area of previously proposed Pleistocene refugia12,14 (Budongo, Bwindi, Gishwati, Ngogo, and Nyungwe), suggesting an expansion into the southeast (Issa Valley54), central and southwest (Regomuki), and northwest (Rubi-Télé, Bili, Chinko, and Ngiri) after the LGM (Figures 2B and S78; Note S9). In central chimpanzees, we detected two strongly differentiated population clusters rather than a cline (Figures 2B,S76, S82, and S84; Notes S6, S7, and S10), separated by the Ogooué River in Gabon, which appears to have been a barrier reducing migration between these regions at least since the LGM, and maintained through the Holocene. Meanwhile, connectivity was higher within each central chimpanzee cluster, indicated by IBD-like tracts, rare allele sharing, and the EEMS surface (Figures 3A, S76, and S84; Notes S9 and S10). The southern cluster also matches with those populations that show a larger amount of bonobo-like introgressed fragments (Figure S64).

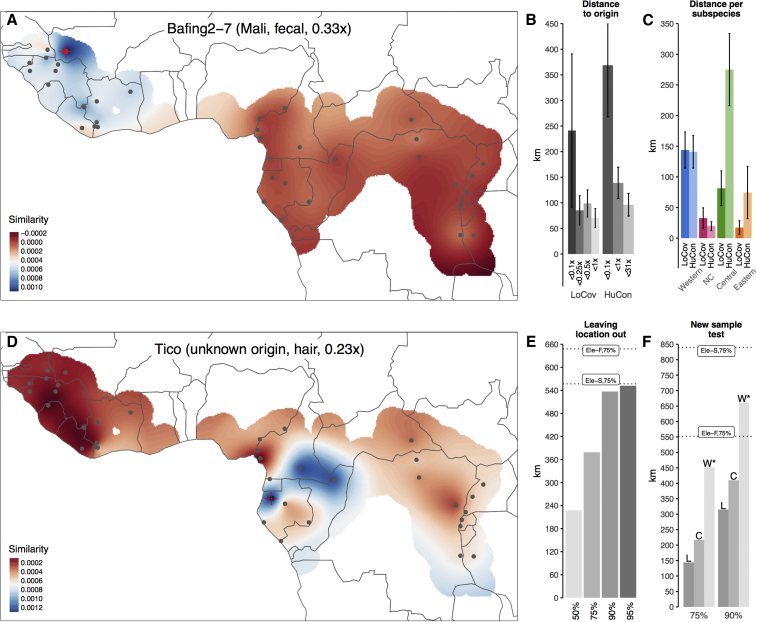

Geolocalization of chimpanzees using rare alleles

Our unique sampling breadth allowed the discovery of ∼50% more new genetic variants on chromosome 21 (Figure S29) in comparison with previously published chimpanzee whole genomes.6 In particular, rare variation likely emerged recently (during few hundreds to thousands of years46), and will be geographically structured. Hence, rare alleles are particularly useful for geolocalization because the chimpanzee groups studied here do show local stratification in the sharing of these alleles (Figures S76–S79; Note S9). Here, we developed a strategy to use rare variants (STAR Methods; Figures S67–S75; Note S9) to infer the geographic origin of samples. In brief, we used a reference panel of 434 samples of sufficient quality (Note S3) across 38 sampling locations, obtained the derived frequency of each SNP within each population, and retained SNPs that were observed at one given sampling location but at low cumulative frequency (lower than 1) across all other locations (STAR Methods; Note S9). We then tested samples by calculating their proportion of matching genotypes, across all such positions, to each reference population, and applied a spatial interpolation (kriging) across the chimpanzee range, allowing the visualization of regions of putative origin (e.g., Figure 4A; Data S1, Figure S96).

Figure 4.

Chimpanzee geolocalization based on rare variation

(A) Spatial model of shared rare alleles with 38 sampling locations. Red indicates lower amounts, while blue indicates larger amounts of shared rare alleles. Black dots, locations included in the reference panel; red dot, known place of origin (low-coverage sample Baf2-7 from Bafing, Mali); red cross, inferred origin. Red cross and dot overlap in this correctly assigned sample.

(B) Average distance (km) of best matching to true location in bins of coverage for samples with low coverage and contamination (LoCov) (n = 99) and samples with human contamination of more than 0.5% (HuCon) (n = 139). Error bars represent the SEM.

(C) Average distance of best matching to true location per subspecies, stratified by low-coverage and human-contaminated samples; note that the Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee range is smaller than that of other subspecies, thus resulting in smaller distances. Error bars represent the SEM.

(D) Geolocalization of the chimpanzee Tico from a rescue center in Spain, here assigned to Gabon or Equatorial Guinea.

(E) Assignment accuracy when leaving full locations out (n = 434), with 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles for the distance of inferred to true origin; for comparison, best 75th percentiles for geolocalization of elephants21 are shown as dotted lines (Ele-S, Savanna elephant; Ele-F, forest elephant).

(F) Assignment accuracy for samples not included in the reference panel (L, low coverage; C, contaminated; W, whole-genome data6); for comparison, the 75th percentiles of the single sample test in elephants are shown as dotted lines; the asterisk marks that the origin for whole genomes may be different from the place of confiscation reported for these individuals. See also Figures S67–S75, S80, and S81.

First, we applied this strategy to 99 samples excluded from the reference panel due to low coverage (<1-fold), as well as 139 samples with human contamination (>0.5%) (Data S1, Figures S96 and S97). At a coverage of more than 0.1-fold, samples are, on average, located 81 km (0–502 km) from their true origin (Figure 4B). In the presence of human contamination (>0.5%, coverage >0.1-fold), this average increases to 139 km, on average, mostly due to central chimpanzee samples (Figure 4C). Samples from locations not included in the reference panel are assigned to nearby regions of the corresponding subspecies (Data S1, Figure S98).

We assessed the accuracy of our method using an approach from a previous study in elephants21 by inferring the origin of samples when leaving their sampling location out of the reference panel. We find that 75% of the samples are inferred to originate from within 379 km of their sampling location (Figure 4E), considerably closer than the closest 75th percentile in elephants (557 km for sample groups of savannah elephants21). Remarkably, when comparing the closest 75th percentile of testing single samples where the sampling location was included in elephants (552 km for forest elephants), in chimpanzees we find that this distance from the true location is less than half for the low-coverage (144 km) and contaminated (217 km) samples (Figure 4E). Our geographically dense reference panel with thousands of markers, likely enhanced by a lower overall mobility of chimpanzees compared with elephants, makes our methodology outperform the elephant one, even though genotype data are extremely patchy and incomplete. Also, the approximate origin of previously published chimpanzee whole genomes6 (Note S9; Data S1, Figure S102) is closer to the known place of origin or confiscation (75th percentile: 452 km; Figure 4F) than what has been found for elephants of known origin. Finally, we used this strategy to estimate the most probable origin of 20 chimpanzees from two Spanish rescue centers (Fundació Mona and Fundación Rainfer), which were sequenced at low coverage from hair and blood samples (median 0.35-fold coverage, ranging from 0.15- to 4.3-fold) (Figures S80 and S81; Note S9). Hence, with our method even shallow sequencing (without target capture) provides enough information for the approximate geolocalization of chimpanzees with unknown or low confidence origin information (e.g., Figures 4D, S80, and S81; Note S9).

Discussion

Our study shows how non-invasive samples can be used as a source of genomic DNA for population and conservation genomic purposes. Here, we have implemented target capture on chimpanzee fecal samples, although it is worth noting that the same approach could be applied to other great ape and primate species, broadening their application from a few autosomal, sex-linked, or mtDNA markers to an entire chromosome. Precisely, by target capturing a complete chromosome we have the power to discover variation previously unreported and detect contiguous segments of DNA that are inherited together. We found evidence supporting the genetic differentiation of the four recognized subspecies of chimpanzee populations,3,6 whose differentiation could be linked to historical geographical barriers, in particular the Sanaga River and Ubangi River. Such barriers of gene flow41,55 have been proposed before, particularly the Congo river separating bonobos from chimpanzees. However, rivers have not been immutable throughout history, and a reduction of river discharge during glaciation periods likely opened corridors for migration;38 for example, allowing ancient introgression from bonobos into non-western chimpanzees6 and also between chimpanzee subspecies.44 Here, we detected differential amounts of ancient introgression from bonobos to central chimpanzee populations north and south of the Ogooué River. This could be explained either by multiple phases of genetic exchange between chimpanzees and bonobos, as has been suggested previously,6 or by a dilution of bonobo ancestry due to admixture with other chimpanzee populations, as supported by a higher Nigeria-Cameroon and eastern chimpanzee ancestry in the central chimpanzee populations north of the Ogooué River. However, these scenarios are not mutually exclusive, and need to be further investigated using multiple whole genomes from these different regions.

Importantly, this dataset is useful to study the population history and connectivity of wild chimpanzee communities in more recent times. Population stratification in chimpanzee populations can be explained by isolation-by-distance to some degree,11 but known ecological or geographical barriers have also reduced gene flow between certain populations for extended periods of time, leading to substantial substructure in chimpanzees. This is the case for the Ogooué River acting as a barrier between northern and southern central chimpanzee populations, or Lake Tanganyika separating eastern chimpanzee populations in the south.53 The Uélé River, isolating eastern chimpanzees since the LGM in the north, is concordant with observed behavioral differences to its north and south.56,57 Corridors of gene flow between non-western chimpanzee subspecies have been suggested previously,3,6,11 and we restrict these events mainly to specific areas between central, Nigeria-Cameroon, and eastern chimpanzee populations in the north of their range, particularly between Goualougo and Gashaka, located at the northern fringe of the distribution of these subspecies. However, due to the lack of sampling in eastern Cameroon, we propose that a historical corridor may have reached from the northern range of central chimpanzees to Gashaka through central Cameroon, in concordance with previous results on mtDNA.44

These patterns of isolation-by-distance over tens of thousands of years, with genetic interactions occurring on a local scale, stand in apparent contrast to the demographic history of most human populations during the same time frame, which is characterized by high levels of migration.46 We speculate that chimpanzee’s comparably lower migration pattern might be related to a lower extent of information transmission, which is a fundamental difference between them and humans.58 We speculate that limited genetic and cultural exchange in chimpanzees compared with humans might be a consequence of the social structure of chimpanzees.59 The higher inter-connectivity of western chimpanzees may also help to explain their larger behavioral diversity compared with non-western chimpanzee populations. A large degree of sharing of IBD-like fragments in the northwestern range of western chimpanzees, resulting from either recent expansion or high recent connectivity, might reflect population movements from Pleistocene refugia in the south (Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire) after the LGM (Figure 2B),12,13 possibly related to the proposed cultural expansion in western chimpanzees.14 However, the Comoé sites in the east of Côte d’Ivoire are genetically closer to forest populations in the south (Figures S45 and S54), despite seemingly being behaviorally similar to the north-eastern mosaic woodland habitat populations.60 We also find genomic support for an expansion from Pleistocene refugia in eastern chimpanzee populations to the south, west, and northwest after the LGM (Figure 2B).

Using our knowledge of genetic diversity linked to geographical locations, we present a strategy for geolocalization with improved accuracy and precision, even when using low-coverage or contaminated samples (Figure 4). Geolocalization of chimpanzees has direct conservation applications: first, it can help ensure that confiscated chimpanzees from illegal pet trade61 are placed into sanctuaries in their countries of origin as mandated by the international standards.62 Second, when sequencing confiscated individuals or wildlife products (e.g., bushmeat), it can allow for the detection of poaching hotspots, so relevant authorities can enforce national and international laws enacted for protected species.21,63 Successful methods have been developed for African elephants,21,64 but past attempts in chimpanzees did not provide sufficient spatial resolution;19,20 while, unfortunately, microsatellite data do not yield a sufficient degree of genetic structure in chimpanzees.11 However, some geographic regions are not well resolved, resulting in different possible countries of origin, as is the case for other species.21 Considering that samples are assigned to nearby locations when their sampling site is not covered (Data S1; Figure S99), this is likely to be improved with yet better sampling. Our strategy is based on low-coverage shotgun sequencing, with lower costs but requiring state-of-the-art laboratory facilities and bioinformatic know-how to process and identify the origin of a confiscated individual, which is not accessible for in situ genotyping.65,66 However, new optimizations on sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies,67 might be helpful to obtain genotype information on-site, to ascertain the origins of confiscated wildlife and products.

In conclusion, using the capture of chromosome 21 on hundreds of chimpanzee fecal samples, we presented the first geographically linked catalog of genomic diversity in extant wild chimpanzee populations. This resource allows for the determination of fine-scale population structure, past and recent gene flow, and migration events, and the construction of a geo-genetic map for the geolocalization of orphaned chimpanzees and confiscated bushmeat.

Limitations of the study

The use of non-invasive samples for population genomics is still limited by their low quality and low proportions of hDNA. Under these circumstances, whole-genome sequencing, which would provide stronger support in many analyses, is prohibited by both low library complexity and economical constraints. Since sequencing was limited to a portion of the genome, we could not reach enough confidence to resolve the origin of the differential amount of bonobo introgression in central chimpanzees, and we cannot apply the standard methods to study gene flow. The nature of our dataset also impedes the reconstruction of recent connectivity using IBD-like segments since the accuracy to detect those segments is directly limited by the missingness inherent in low-coverage datasets. Therefore, the timing of the events using the length of the IBD-like fragments can encompass large confidence intervals since the low coverage and high missingness in the data could result in underestimating their length, leading to inaccurate timings.

Fecal samples may be subject to contamination from mammalian or primate DNA from species included in the diet of the chimpanzee. Even though we used a very thorough quality control, due to our limited coverage we cannot discard small remnants of contamination in our dataset.

Finally, the geolocalization approach is based on rare variation, and relies on having a dense georeferenced panel of samples; even after our extensive sampling effort there are some under-represented areas where future studies should focus on gathering samples to fill in the current gaps.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological samples | ||

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-01 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-02 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-03 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-06 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-08 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-09 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-10 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-11 |

| Chimpanzee hair sample | This Study | AZA-01-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-42 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-46 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-68 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-73 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-74 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Baf2-75 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-42 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bat1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-28 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-46 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-47 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-51 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bil1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bili2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bili2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-33 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-57 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-60 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-71 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-75 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe1-77 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-33 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Boe2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bou1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud1-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-45 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-52 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-73 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-81 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud2-86 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud3-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bud3-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi-2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi-2-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-58 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-61 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-64 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-69 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-71 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-74 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-78 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Bwi1-90 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-49 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-71 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-74 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam1-78 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam2-77 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam3-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam3-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam3-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cam3-45 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Chinko-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP1-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP1-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP2-1_B |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CMNP2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-47 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-63 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-70 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Cnp1-75 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-31 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPE1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPN1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPN1-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPN1-63 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-16_2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | CNPW2-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-49 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-56 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-57 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-64 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-67 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-71 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con2-80 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con3-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Con3-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-68 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-79 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din2-83 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din3-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din3-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din3-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Din3-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-42 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja2-57 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja3-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja3-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja3-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja3-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Dja3-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-60 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo1-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-68 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo3-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Djo3-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | El3-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn1-42 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-52 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-62 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn2-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-56 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-68 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fjn3-84 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-51 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-80 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-82 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Fouta3-87 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-36 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-28 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-67 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gas2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-10-03 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-11-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-11-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-13-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-13-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-14-05 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-22-06 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-25-02 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-25-05 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-28-02 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-29-06 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-30-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-34-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-34-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-36-07 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-36-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-37-04 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | GB-37-09 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo1-86 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-57 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-59 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-63 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo2-85 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo3-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gbo3-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-33_2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-42_2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-51 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-56 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-60 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-61 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco2-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gco4-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-62 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep1-65 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-28 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-30 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-45 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-52 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gep2-61 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-01 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-04 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-05 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-06 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-07 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-08 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gha-01-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-47 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-59 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-70 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis2-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis2-50 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gis2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-51 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-58 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-61 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-70 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-75 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Gou1-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-01 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-02 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-03 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-04 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-05 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-06 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-07 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-08 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-09 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Itu-01-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ivi1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ivi1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kab2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-49 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-52 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kay2-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-65 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-79 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor1-84 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Kor2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | LCA-3-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | LCA-3-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib1-25D |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib1-6-D |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-28 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-62 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib2-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lib3-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Loma2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop1-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-45 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-76 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-77 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-80 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-82 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop2-88 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop3-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop3-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Lop3-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-01 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-04 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-05 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-07 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-09 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe-02-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-18 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-22_2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-23 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mbe1-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-43 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-56 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-58 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-63 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-66 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-67 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-71 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Mtc1-72 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-31 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-33 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-42 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | MTC2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N173-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N173-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N173-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N181-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N181-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N182-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N183-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N183-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N186-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N186-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N190-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N259-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N259-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N259-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N260-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N260-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N260-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N261-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N261-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | N262-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Ngi2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-47 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-49 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-51 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-52 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-77 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-78 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim1-79 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-33 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Nim2-58 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-15 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-40 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-44 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-57 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-77 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP1-86 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-54 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-55 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-67 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-68 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-74 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP2-79 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | NNP3-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-11 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-12 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-28 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-29 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-31 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-34 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Onp1-9 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt1-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt1-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt1-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-14 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-21 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-25 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-26_2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-31 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-35 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-37 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-38 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-41 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-6 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-7 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Rt2-8 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-17 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-19 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-2 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-22 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-3 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-39 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-1 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-10 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-13 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-16 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-20 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-26 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-48 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-49 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-53 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | San2-59 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-24 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-27 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-31 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-32 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-33 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-4 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-47 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-5 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-56 |

| Chimpanzee fecal sample | This Study | Sob1-57 |