Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to examine how nurse managers’ leadership styles, work engagement, and nurses’ organizational commitment are related in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design using an online survey instrument targeted at nurse managers and nurses working in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Multi-factor leadership questionnaire (MLQ), organizational commitment questionnaire (OCQ), and Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) were used in the Questionnaire. The survey link is forwarded to HR administrators of 71 hospitals, which includes public, private, and public–private partnership hospitals. The survey link was active from 27th November 2021 to 18th December 2021, and at the end of the survey, 394 responses were received. After removing the incomplete responses, 390 participant responses are considered for data analysis. t-tests and correlation analysis are used to analyze the data.

Results

Among the participants, 84.4% of the participants were nurses and 15.6% were nurse managers. Significant difference (p < 0.05) of opinions is observed among nurse managers in relation to transformational and transactional leadership styles and engagement. Transformational and transactional leaderships are positively correlated with organizational commitment and nurses’ engagement.

Conclusion

Differences in leadership style perceptions among nurses and nurse managers reflected issues in nursing management, which have to be addressed in light of rapid infrastructural changes owing to Saudi vision 2030.

Keywords: leadership, nurses’ engagement, organizational commitment

Introduction

Saudi Arabia is transforming its economy from an oil-dependent economy to a knowledge-based economy through its ambitious Vision 2030 programme, which is aimed at large-scale structural and operational reforms in various sectors.1,2 Saudization is one of the core objectives of Vision 2030, which is aimed at empowering the Saudi nationals, developing their skills and competencies in order to employ them in different sectors, as an approach to reduce the dependency on the expatriates.3 The country’s population is recorded to be 35 million, out of which 13.49 million are expatriate workers in various sectors.4 As per 2020 records, there are 196,701 nurses working in Saudi Arabia, out of which only 84,384 nurses were Saudi citizens, while 57.1% of remaining were expats.5 Nursing workforce in Saudi Arabia is considerably less, as there are only 5.5 nurses available per 1000 population in the country, whereas, there are 7.9 nurses per 1000 population in the UK, and 18 nurses per 1000 population in Switzerland. However, Saudi Arabia fares well in comparison to its neighboring countries, such as Bahrain, which has 2.4 nurses per 1000 population, and 3.1 nurses per 1000 population in the UAE.5–7 Going with the current trend of projected nursing graduates, which is about 26,200 per year, there is a need for 185,722 expatriate nurses to achieve the target of having one nurse per 200 Saudi citizens.8 Furthermore, the expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia are from various countries including India, Sri Lanka, Philippines, and Malaysia.9 Given the highly diverse workforce, it may be challenging for the nurse managers to effectively manage the staff and work. Though there is an increasing support from the government for Saudi nurses, issues such as poor working conditions, limited opportunities, and poor image of nursing among Saudi citizens made nursing profession, the least preferred among Saudis.10 Furthermore, due to the cultural influence, most of the Saudi women do not consider nursing as their career option.11,12

Furthermore, work and living conditions for expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia are considered to be poor, adding to that religious and cultural differences, and language barriers create complex working environment and social living conditions for them.13 Therefore, many expatriate nurses initially come to Saudi Arabia to gain work experience, and they tend to move to developed countries in the west and Europe after acquiring enough skills and expertise.14 Therefore, not only the barriers to the expatriates but also the job dissatisfaction and turnover are few other issues affecting the nursing sector in Saudi Arabia.15,16 As a result, there is a need to realize and establish strong and effective leadership in the nursing sector in order to handle the challenges and issues and enabling organizational commitment and increasing retention rates,17 for better managing challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Various studies15,18,19 have analyzed nursing retention and linked it with job dissatisfaction, intention to leave, cultural differences, etc., but there is considerably little research focusing on the impact of leadership styles on increasing organizational commitment and retention rates.20

Furthermore, achieving sustainability in healthcare operations is one of the main objectives of Vision 2030, which may not be achieved if there is poor leadership, job dissatisfaction and decreasing retention rates in nursing sector, as it is one of the core units in healthcare operations in delivering services directly to the patients. As a part of Saudization, there is also a need to increase the attractiveness of nursing among the career options in Saudi Arabia. In addition, the crisis caused by the Covid-19 has affected the supply of human resources in healthcare, which has affected the delivery of healthcare services in many countries. Therefore, there is an immediate need to assess various strategies that can address the issues associated with nursing staff in Saudi Arabia. An effective leadership can address various issues related to employees in organizations, especially dissatisfaction, retention, and intention to leave by providing support.21,22 Furthermore, different leadership styles can have different effects on employees and their work outcomes.23 Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is determined to evaluate the relationship between the nurse managers leadership styles, nurses work engagement, and their organizational commitment in Saudi Arabian hospitals.

Conceptual Framework

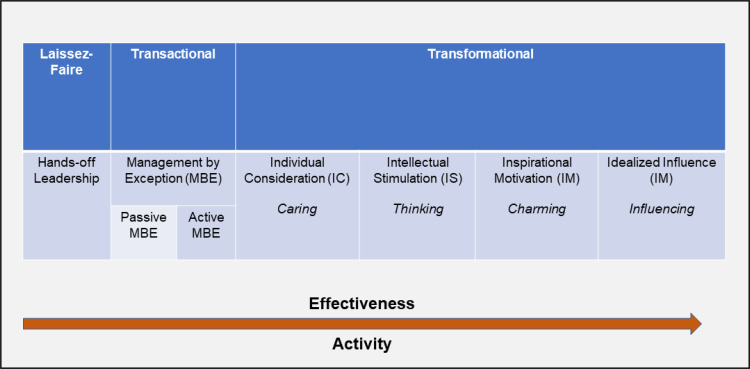

Full range of leadership model (FRL) based on the transformational leadership24 is adopted in this study. In addition, other leadership styles including transactional and laissez-faire were also considered in this study. Transformational leadership is one of the most widely adopted leadership styles focusing on providing support for the employees in developing skills and knowledge.25 Transactional leadership style relies on rewards and punishments according to the employees’ work outcomes in order to achieve optimal job performance.26 Whereas, Laissez-faire leadership takes a hands-off approach to leadership and gives others the freedom to make decisions.27

Effective nursing leadership can be positively linked with better healthcare outcomes, especially in patients’ satisfaction, improved organizational outcomes, and increased nurses’ satisfaction levels.28 As presented in Figure 1, the effectiveness of the processes and activities increases as we move from Laissez-Faire through Transactional and Transformational leadership styles. A recent systematic review29 of 18 studies highlighted that effective leadership can reduce nurse burnout by empowering and promoting nurse engagement, increasing commitment, and creating a healthy work environment. Similarly, transformational leadership was associated with lower turnover intentions, while transactional and laissez-faire leadership styles were associated with higher turnover intentions.30

Figure 1.

Full range leadership model.

Organizational commitment can be analyzed from three types of commitment types, which include affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Affective commitment reflects an employee’s emotional attachment with the organization, when he/she fully adopts the goals and values of the organization, and feels that he/she is fully responsible for the organization’s success or failure. Continuance commitment refers to employees’ perceived attachment with the organization, which is based on what they receive if they stay with the current organization (pay, benefits), and what would be lost if they leave the current organization. They put their best efforts into the work when the rewards match their expectations. Normative commitment is employees’ perceived attachment with the organization based on their expected standards of behavior or social norms. Formality, obedience, etc. are more valued by the employees. If they do not identify these standards, they tend to leave the organization.31

Similarly, employee engagement can be analyzed from three factors, which include vigor, dedication, and absorption. Vigor is a veritable definition of an employee who is proactively engaged in work and is willing to put extra efforts for completing the work. Dedication reflects commitment towards the work engagement, ie, employees want to work because they are enthused about the organization’s goals and mission. Absorption reflects a complete engrossment in the work, where the goal is not to complete the work as soon as possible, but to do it in the best possible way.32

Studies47–49 have shown positive relationships between the leadership styles and work engagement. While transformational leadership styles reflected positive effect on work engagement by enhancing intrinsic motivation, authoritative leadership reflected negative effect on work engagement. For instance, providing training and support to employees (as a part of transformational leadership) can enhance their skills and motivate them to engage actively in various tasks and may increase their commitment towards organization. Previous studies have established these links separately between the leadership models, organizational commitment and work engagement scales; however, they did not consider all the factors in an integrated study to identify the inter-relationships between them. Furthermore, with the significant developments being observed as a part of Vision 2030 in Saudi Arabian hospitals, rapid changes are being observed in the healthcare operations, especially in improving operational efficiency and sustainability. In such contexts, it is highly important to understand and establish the links between the leadership styles, organizational commitment, and work engagement to better understand the nursing work environment and develop policies that aim to foster Saudization process and Vision 2030 objectives.

Considering these factors, this study examines the relationship between the leadership styles, organizational commitment, and nurses’ engagement in Saudi Arabian hospitals.

Materials and Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design for collecting the data related to leadership styles, organizational commitment and work engagement from nursing staff in Saudi Arabian hospitals.

Sampling and Participants

As the survey is targeted at nursing managers and nurses working in Saudi Arabian hospitals, the survey link is forwarded to HR administrators of 71 hospitals, which includes public, private, and public–private partnership hospitals, requesting them to forward the link to the nurses and nurse managers working in their respective hospitals asking them to participate. Only nurses and nurse managers who are currently working were included and those under the age of 20 were excluded from the study. Considering 185,456 nurses working in Saudi Arabia, the sample was calculated using Cochran’s formula,37 at 95% CI and 5% of Margin of error, giving an estimated sample of 384 participants. The survey link was active from 27th November 2021 to 18th December 2021, and at the end of the survey, 394 responses were received. After removing the incomplete responses, 390 responses were considered for the data analysis.

The participants’ demographic information is presented in Table 1. A total of 390 participant responses were considered for the data analysis. Among them, 88.5% were female participants and 11.5% were male participants. The majority of the participants had bachelor’s degree as their educational qualification, followed by 16.4% participants having diploma. The majority of the participants were aged between 20 and 39 years. About 84.4% of the participants were nurses and 15.6% were nurse managers.

Table 1.

Participants’ Demographic Information

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency Counts | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 45 | 11.5% |

| Female | 345 | 88.5% |

| Education | ||

| Diploma | 64 | 16.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 296 | 75.9% |

| Master’s degree | 28 | 7.2% |

| Doctorate | 2 | 0.5% |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 136 | 34.9% |

| 30–39 | 165 | 42.3% |

| 40–49 | 59 | 15.1% |

| 50–59 | 30 | 7.7% |

| >59 | 0 | 0% |

| Work experience | ||

| ≤3 years | 68 | 17.4% |

| 3–5 years | 95 | 24.3% |

| 6–10 years | 95 | 24.3% |

| >10 years | 132 | 33.8% |

| Role | ||

| Nurse Manager | 61 | 15.6% |

| Nurse | 329 | 84.4% |

Questionnaire Design

Three questionnaires were used in this study, which include multi-factor leadership questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio,33 organizational commitment questionnaire (OCQ) developed by Mowday et al,34 and Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) developed by Schaufeli et al35 Accordingly, the main questionnaire is divided into four parts. The first part focuses on collecting participants demographic information, which includes name, age, gender, education, role/job position, work experience, and organization/hospital working for. The second part of the questionnaire includes 21 items from MLQ, which need to be rated on a five-point Likert scale (0: not at all; 1: once in a while; 2: sometimes; 3: fairly often; 4: frequently). Items 1–12 focus on transformational leadership styles, which are further categorized into idealized influence (items 1–3), inspirational motivation (items 4–6), intellectual simulation (items 7–9), and individual consideration (items 10–12). Items 13–18 are related to transactional leadership styles, which are categorized into contingent reward (items 13–15) and management by exception (items 16–18). Items 19–21 are related to laissez-faire leadership style. The questionnaire (MLQ) was translated to Arabic, and a pilot study was conducted with 21 participants, achieving Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 indicating good internal reliability and consistency.36

The third part of the questionnaire includes 18 questions, measured on a 7-point Likert scale ((SD = 0) strongly disagree; (MD = 1) moderately disagree; (LD = 2) slightly disagree; (O = 3) neither disagree nor agree; (LA = 4) slightly agree; (MA = 5) moderately agree; (SA = 6) strongly agree) related to organizational commitment adapted from OCQ. These are further categorized into affective commitment (items 1–6), continuance commitment (items 7–12), and normative commitment (items 13–18). The questionnaire (OCQ) was translated to Arabic, and a pilot study was conducted with 21 participants, achieving Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77 indicating good internal reliability and consistency.36

The fourth part of the questionnaire includes 17 questions related to work engagement, measured on a 7-point Likert scale ((N = 0) never; (AN = 1) almost never (a few times a year or less); (R = 2) rarely (once a month or less); (S = 3) sometimes (a few times a month); (O = 4) often (once a week); (VO = 5) very often (a few times a week); (A = 6) always (every day)). These are further categorized into vigor (items 1–6), dedication (items 7–11), and absorption (items 12–17).

The questionnaire (UWES) was translated to Arabic, and a pilot study was conducted with 21 participants, achieving Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81 indicating good internal reliability and consistency.36 The questions in the main questionnaire are presented in both Arabic and English languages to improve the readability and understandability. An online version of the survey questionnaire was generated using Google survey, to which a link is generated for collecting data.

Data Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using SPSS version 20.0, and various statistical techniques including t-tests, Pearson’s correlation, were used. Missing data was removed in order to avoid any bias in analyzing the results. The primary outcome of the analysis is the correlation between leadership style and organizational commitment, and leadership style and employee engagement.

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was taken from all the participants using checkbox option before starting the survey, where users were provided with information about the study. Participation was voluntary, and completion of the survey was taken as consent to participate. Anonymity of the participants is ensured in this study. Ethical approval for the study was received from Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. This manuscript study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The perceptions of leadership styles among the nurse managers and nurses are presented in Table 2. Significant difference (p < 0.05) of opinions was observed among nurse managers in relation to transformational and transactional leadership styles (Table 2). Transformational leadership was most preferred among the nurse managers followed by transactional leadership and laissez-faire leadership styles. However, among the nurses, both transformational and transactional leadership styles received higher mean scores compared to laissez-faire leadership style. Considering the overall responses, transactional leadership was most preferred (Mean = 2.7), followed by transactional leadership (Mean = 2.6), followed by laissez-faire leadership style (Mean = 2.3).

Table 2.

Nurse Managers’ and Nurses’ Perceptions of Leadership Styles

| Nurse Managers | Nurses | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Transformational leadership | 2.97 | 1.05 | 2.44 | 1.28 | 3.0484 | 0.0025* |

| Idealized influence | 3.03 | 1.01 | 2.46 | 1.18 | 3.5391 | 0.0005* |

| Inspirational motivation | 3.08 | 1.005 | 2.49 | 1.17 | 3.6952 | 0.0003* |

| Intellectual stimulation | 2.90 | 1.06 | 2.37 | 1.16 | 3.3202 | 0.0010* |

| Individual consideration | 2.90 | 1.12 | 2.47 | 1.16 | 2.6732 | 0.0078* |

| Transactional leadership | 2.86 | 1.03 | 2.44 | 1.16 | 2.6409 | 0.0086* |

| Contingent reward | 2.98 | 1.08 | 2.43 | 1.17 | 3.4114 | 0.0007* |

| Management by exception | 2.74 | 0.98 | 2.46 | 1.16 | 1.7712 | 0.0773 |

| Laissez-faire | 2.30 | 1.20 | 2.29 | 1.21 | 0.0594 | 0.9527 |

Note: *Statistically significant difference.

There were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) observed among the nurse managers and nurses in relation to organizational commitment sub-scales (Table 3). It is interesting to note that nurse managers normative commitment gained high mean score followed by continuance commitment and affective commitment among nurse managers, whereas nurses rated continuance commitment as highest followed by normative commitment and affective commitment. It is interesting to note that nurse managers exhibited higher commitment in all sub-scales compared to nurses. Considering the overall responses, normative commitment gained high mean scores (Mean = 3.21) followed by continuance commitment (Mean = 3.17) and affective commitment (Mean = 2.91).

Table 3.

Nurse Managers’ and Nurses’ Perceptions of Organizational Commitment

| Nurse Managers | Nurses | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Affective Commitment | 3.03 | 1.47 | 2.80 | 1.54 | 1.0788 | 0.2813 |

| Continuance Commitment | 3.36 | 1.58 | 2.99 | 1.73 | 1.5543 | 0.1209 |

| Normative Commitment | 3.44 | 1.57 | 2.98 | 1.76 | 1.9052 | 0.0575 |

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed among the nurse managers and nurses in relation to various sub-scales of employee engagement (Table 4). Dedication gained a high mean score followed by absorption, and vigor among both nurse managers and nurses. However, engagement levels on all subscales were identified to be higher for nurse managers compared to nurses. Considering the overall ratings, dedication gained the highest mean score (Mean = 3.96), followed by absorption (Mean = 3.87) and vigor (Mean = 3.61).

Table 4.

Nurse Managers’ and Nurses’ Perceptions of Work Engagement

| Nurse Managers | Nurses | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Vigor | 4.02 | 1.70 | 3.21 | 1.72 | 3.3843 | 0.0008* |

| Dedication | 4.39 | 1.68 | 3.53 | 1.86 | 3.3650 | 0.0008* |

| Absorption | 4.26 | 1.54 | 3.48 | 1.84 | 3.1139 | 0.0020* |

Note: *Statistically significant difference.

Table 5 presents the correlations between the leadership, organizational commitment, and employee engagement subscales. It is evident from the results that transformational leadership has a moderate degree of correlation with all types of organizational commitment (as correlations ranged between 0.30 and 0.49). It is interesting to note that the inspirational motivation (r = 0.465, p < 0.01) and idealized influence (r = 0.455, p < 0.01) had strong positive correlation with normative commitment. Furthermore, the inspirational motivation also had a positive relation with continuance commitment (r = 0.456, p < 0.01). Transaction leadership styles had a positive relationship with organizational commitment compared to transformational leadership style. This is evident from the positive relationship of contingent reward with affective commitment (r = 0.461, p < 0.01), continuance commitment (r = 0.461, p < 0.01), and normative commitment (r = 0.475, p < 0.01). Furthermore, laissez-faire leadership reflected moderate positive relationship with all subscales of organizational commitment, especially the normative commitment (r = 0.469, p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Correlations Between MLQ Subscales, OCQ, and UWES Subscales Using Pearson Product-Moment

| Affective Commitment | Continuance Commitment | Normative Commitment | Vigor | Dedication | Absorption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized influence | 0.402** | 0.423** | 0.455** | 0.489** | 0.510** | 0.500** |

| Inspirational motivation | 0.413** | 0.456** | 0.465** | 0.501** | 0.521** | 0.511** |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.440** | 0.441** | 0.438** | 0.482** | 0.490** | 0.504** |

| Individual consideration | 0.417** | 0.449** | 0.439** | 0.497** | 0.519** | 0.516** |

| Contingent reward | 0.461** | 0.461** | 0.475** | 0.512** | 0.528** | 0.535** |

| Management by exception | 0.433** | 0.432** | 0.464** | 0.516** | 0.528** | 0.532** |

| Laissez-faire | 0.454** | 0.449** | 0.469** | 0.423** | 0.401** | 0.428** |

Note: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

It is evident from Table 5 that transformational leadership has a moderate to strong relationship with employee engagement subscales (“r” value ranged between 0.48 and 0.55). Further analyzing the results, inspirational motivation had strong positive relationship with dedication (r = 0.521, p < 0.01) and absorption (r = 0.511, p < 0.01). Similarly, individual consideration also exhibited strong positive relationship with dedication (r = 0.519, p < 0.01) and absorption (r = 0.516, p < 0.01). However, transactional leadership reflected a stronger relationship with employee engagement compared to transformational leadership (“r” values between 0.5 and 0.71). Both contingent rewards and management by exception reflected a strong positive correlation with all engagement subscales including vigor, dedication, and absorption. However, laissez-faire reflected a moderate relationship with all engagement subscales.

Significant positive correlation can be identified between organizational commitment and nurses’ engagement as shown in Table 6. Strongest relationship was identified between normative commitment, and vigor (r = 0.701, p < 0.01) and absorption (r = 0.690, p < 0.01).

Table 6.

Correlations Between OCQ and UWES Subscales Using Pearson Product-Moment

| Vigor | Dedication | Absorption | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affective Commitment | 0.620** | 0.574** | 0.588** |

| Continuance Commitment | 0.671** | 0.632** | 0.651** |

| Normative Commitment | 0.701** | 0.667** | 0.690** |

Note: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Discussion

The findings in this study indicated that nurse managers exhibited both transformational and transactional leadership styles simultaneously, although they perceived themselves to be more inclined towards transformational leadership styles. It is possible that leaders can inhibit both transformational and transactional leadership styles according to the conditions in working environment,38 which was also observed in previous studies.20,39,40 Transformational leadership can be an important factor influencing various aspects such as organizational commitment and staff engagement and retention. In the current study, idealized influence and inspirational motivation were the most frequently displayed subscales compared to intellectual simulation and individual consideration, which contradicted with findings in,20 where idealized influence was considered to be the least frequently referred subscale. Given the current condition, ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, and increased work pressures, it may be possible that the leaders focused on motivating the nurses to handle the crisis and work pressure, rather than considering intellectual stimulation. Focusing on the nurses, they indicated that they experience both transformational and transactional leadership styles, similar to the views of nurse managers.

However, focusing on the organizational commitment, nurse managers reflected more commitment than nurses, although the ranking of commitment subscales remained the same in both groups: continuance commitment followed by normative commitment and affective commitment. Saudi Arabian healthcare system is largely dependent on expatriate workers, especially non-Saudi nurses. Studies20,41 have confirmed that non-Saudi nurses may leave Saudi Arabia if they have found better opportunities in some other countries, reflecting a lack of commitment and loyalty. However, studies10–12 also referred to various reasons for lack of commitment, among which cultural differences, poor living conditions and dissatisfaction were cited as the major reasons. Accordingly, a strong positive correlation was identified between transactional leadership style and normative, continuance and affective commitment, rather than transformational leadership style and organizational commitment. However, a significant relationship between organizational commitment and transformational leadership was identified among the nurses, which is similar to the studies.20,42 However, laissez-faire reflected moderate positive relationship with organizational commitment, thus indicating that both transactional and transformational leadership styles can have a positive effect on organizational commitment.

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between leadership styles, organizational commitment, and nurses’ engagement. Nurse managers’ perceptions about their leadership styles and nurses’ perceptions about leadership styles, and similarly commitment and engagement (influenced by leadership styles) are important, because what nurse managers perceive about leadership styles may not necessarily be same as what leadership styles nurses expect from their managers. Examining this relationship helps in understanding whether nurse managers’ leadership styles are the same as those nurses expect. However, findings have illustrated significant differences in relation to transactional and transformational leadership styles between nurses and nurse managers, indicating the differences in practice. Therefore, it is important that nurse managers in these hospitals have to adjust their leadership styles by considering the nurses’ expectations in order to increase their commitment and engagement levels.

In relation to engagement, both transformational and transactional leadership styles reflected a positive correlation with all engagement subscales in similar to.43 However, transactional leadership had stronger relationship with engagement characteristics, such as dedication and absorption than transformational leadership. As the majority of the nurses in Saudi Arabia are expats, they may be less committed to the organization and more inclined towards transactional characteristics as they move to the country for opportunities to earn and work. Therefore, it is possible that transactional leadership may be more correlated with nurses’ engagement compared to transformational leadership. For instance, in a study44 conducted in UAE, which also relies greatly on expat nurses, it was identified that transformational leadership is negatively correlated with work load, while transactional leadership is positively correlated with work load, which clearly indicates that engagement characteristics such as dedication and absorption may be significantly influenced by transactional aspects such as contingent rewards. However, laissez-faire reflected moderate positive relationship with nurses’ engagement, thus indicating both transactional and transformational leadership styles can have positive impact on nurses’ engagement.

Furthermore, no significant difference of opinions was observed between nurse managers and nurses in relation to all sub scales of organizational commitment. However, nurse managers reflected more normative commitment than nurses, reflecting that although they are little unsatisfied or not happy, they tend to be associated with their organization; but nurses, on the other hand, reflected low commitment levels in all the sub-scales. Due to the high length of experience or association with their organizations, it may be possible that nurse managers reflected higher normative commitment levels. In relation to work engagement levels, the differences exhibited by nurse managers and nurses can be correlated with their perceptions towards leadership styles, where nurses reflected lower perceptions towards transformational and transactional leadership styles. Therefore, it is also evident that transformational leadership may be positively related with higher work engagement levels.

Furthermore, strong positive correlations observed between organizational commitment and nurses’ engagement indicate that nurses may put more efforts in work, if they are committed to the organization, which impacts patient outcomes and improves the quality of care provided.50,51

Similar results were identified in,45 however, there are various socio-demographic factors that may influence both organizational commitment and nurses’ engagement in Saudi Arabia.46

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. It is important that the results of this study be viewed and generalized with care as there may be inevitable and unaccountable self-selection bias in the data. Furthermore, the appropriateness of the measures and techniques used in this study may be questioned.

Implications

This study also has both practical and theoretical implications. The findings in this study may be used by the policy makers in effectively formulating the strategies for attracting, developing, and retaining Saudi nurse work force in order to limit the dependency on expatriate nurses; and also, to effectively manage the current non-Saudi nurse’s turnover rates and satisfaction levels to meet the country's needs and targets as specified in Vision 2030. This study also contributes to the lack of literature focusing on the impact of leadership styles and employee engagement and commitment, and also opens up the new research ideas for interlinking various influencing factors affecting nurses’ management in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

Understanding the relationship between the factors such as nurses’ leadership styles, work engagement, and organizational commitment is important because of the fast-changing regulations, procedures, and quality of work-life, which may significantly affect the healthcare operations and service delivery. This study has been conducted to address this gap, and valuable findings have been identified. Although differences existed in the preferences of leadership styles among the nurses and nurse managers, the majority of them preferred transformational and transactional leadership styles. In addition, nurses exhibited lower work engagement and organizational commitment compared to nurse managers, which is one of the major concerns identified in the times when Saudi Arabia is planning to completely transform its healthcare infrastructure. As Transformational and transactional leadership are positively correlated with organizational commitment and nurses’ engagement, there is a need to effectively adopt these leadership styles for a smooth transition of existing healthcare system into a modern healthcare system as planned through Vision 2030. However, further studies are required for generalizing the results, which can aid decision-makers in taking effective decisions with respect to nurses’ management in the kingdom.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rahman R, Al-Borie H. Strengthening the Saudi Arabian healthcare system: role of Vision 2030. Int J Healthc Manag. 2020;14(4):1483–1491. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2020.1788334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vision 2030. Overview [Internet]. Vision 2030; 2021. [cited December 17, 2021]. Available from: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/overview/. Accessed May 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahenaz M, Uzma J. Training and development opportunities and turnover intentions post saudization. PalArch’s J Archaeol Egypt/ Egyptol. 2021;18(14):521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 4.INSIGHT G, INSIGHT G. Saudi Arabia population statistics 2021 [Internet]. Official GMI Blog; 2021. [cited December 17, 2021]. Available from: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-population-statistics/. Accessed May 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health. Statistical year book 2020 [Internet]. Ministry of Health; 2021. [cited December 17, 2021]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/book-Statistics.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.OECD. Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Bank. World development indicators 2017. Washington, DC: © World Bank; 2017. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26447License:CCBY3.0IGO. Accessed May 30, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aljohani KAS. Nursing education in Saudi Arabia: history and development. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7874. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alluhidan M, Tashkandi N, Alblowi F, et al. Challenges and policy opportunities in nursing in Saudi Arabia. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00535-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mahmoud S, Mullen P, Spurgeon P. Saudization of the nursing workforce: reality and myths about planning nurse training in Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci. 2012;8:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazzaz L. Saudi Nurses’ Perceptions of Nursing as an Occupational Choice: a Qualitative Interview Study [unpublished PhD thesis]. University of Nottingham; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chetty K. ICU nurses voice their concerns on workload and wellbeing in a Saudi Arabian Hospital: a need for employee wellbeing program. Saudi J Nurs Health Care. 2021;4(9):296–307. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsadaan N, Jones L, Kimpton A, DaCosta C. Challenges facing the nursing profession in Saudi Arabia: an integrative review. Nurs Rep. 2021;11(2):395–403. doi: 10.3390/nursrep11020038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Dossary R, Vail J, Macfarlane F. Job satisfaction of nurses in a Saudi Arabian university teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(3):424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.00978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saquib N, Zaghloul M, Saquib J, Alhomaidan H, Al‐Mohaimeed A, Al‐Mazrou A. Association of cumulative job dissatisfaction with depression, anxiety and stress among expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(4):740–748. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Billah S, Saquib N, Zaghloul M, et al. Unique expatriate factors associated with job dissatisfaction among nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;68(3):358–364. doi: 10.1111/inr.12643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavoie-Tremblay M, Fernet C, Lavigne GL, Austin S. Transformational and abusive leadership practices: impacts on novice nurses, quality of care and intention to leave. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:582–592. doi: 10.1111/jan.12860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alshammari M, Duff J, Guilhermino M. Barriers to nurse–patient communication in Saudi Arabia: an integrative review. BMC Nurs. 2019;18(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12912-019-0385-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albougami AS, Alotaibi JS, Alsharari AF, et al. Cultural competence and perception of patient-centered care among non-Muslim expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2019;13(2):933–939. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Yami M, Galdas P, Watson R. Leadership style and organizational commitment among nursing staff in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26(5):531–539. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssens S, Simon R, Beckmann M, Marshall S. Shared leadership in healthcare action teams: a systematic review. J Patient Saf. 2018;17(8):e1441–e1451. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham R, Woodhead T. Leadership for continuous improvement in healthcare during the time of COVID-19. Clin Radiol. 2021;76(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gemeda H, Lee J. Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: a cross-national study. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03699. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass BM. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budur T. Effectiveness of transformational leadership among different cultures. Int j Soc Sci Educ Stud. 2020;7(3):119–129. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azizaha YN, Rijalb MK, Rumainurc UN, et al. Transformational or transactional leadership style: which affects work satisfaction and performance of Islamic University Lecturers during COVID-19 pandemic? Syst Rev Pharm. 2020;11(7):577–589. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robert V, Vandenberghe C. Laissez-faire leadership and affective commitment: the roles of leader-member exchange and subordinate relational self-concept. J Bus Psychol. 2021;36:533–551. doi: 10.1007/s10869-020-09700-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings GG, MacGregor T, Davey M, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce 160 and work environment: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(47):363–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei H, King A, Jiang Y, Sewell K, Lake D. The impact of nurse leadership styles on nurse burnout. Nurse Lead. 2020;18(5):439–450. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magbity J, Ofei A, Wilson D. Leadership styles of nurse managers and turnover intention. Hosp Top. 2020;98(2):45–50. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2020.1750324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowditch J, Buono A, Stewart M. A Primer on Organizational Behavior. 7th ed. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gera N, Sharma RK, Saini P. Absorption, vigor and dedication: determinants of employee engagement in B-schools. Indian J Econ Bus. 2019;18(1):61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bass B, Avolio B. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Manual. 3rd ed. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW. The measurement of organizational commitment. J Vocat Behav. 1979;14:224–247. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas. 2006;66(4):701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48:1273–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bass BM, Bass R. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. 4th ed. New York: Free Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abualrub R, Alghamdi M. The impact of leadership styles on nurses’ satisfaction and intention to stay among Saudi nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:668–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Hussami M. A study of nurses’ job satisfaction: the relationship to organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and level of education. Eur J Sci Res. 2008;22:286–295. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Aameri A. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment for nurses. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laschinger H, Finegan J, Wilk P. The impact of unit leadership and empowerment on nurses’ organizational commitment. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:228–235. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23d2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mousa WA, EldinFerky NE, Elewa AH. Relationship between nurse manager leadership style and staff nurses’ work engagement. Egypt Nurs J. 2019;16(3):206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussain M, Akthar S. Impact of leadership styles on work related stress among nurses. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2017;3(8):907–916. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohail R, Zaman F. Effects of work environment and engagement on nurses organizational commitment in Public Hospitals Lahore, Pakistan. Saudi J Med Pharm Sci. 2017;3(7A):748–753. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Haroon HI, Al-Qahtani MF. Assessment of organizational commitment among nurses in a Major Public Hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:519–526. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S256856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayati D, Charkhabi M, Naami A. The relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement in governmental hospitals nurses: a survey study. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:25. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shu C-Y. The impact of intrinsic motivation on the effectiveness of leadership style towards on work engagement. Contemp Manag Res. 2015;11(4):327–350. doi: 10.7903/cmr.14043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manning J. The influence of nurse manager leadership style on staff nurse work engagement. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(9):438–443. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos A, Chambel M, Castanheira F. Relational job characteristics and nurses’ affective organizational commitment: the mediating role of work engagement. J Adv Nurs. 2015;72(2):294–305. doi: 10.1111/jan.12834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Botha, I.B.E. Organisational commitment, work engagement and meaning of work of nursing staff in hospitals: original research. SA J Ind Psychol. 2013;39(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]