Abstract

Purpose

Cancer patients were particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic given their reliance on the healthcare system, and their weakened immune systems. This systematic review examines the social, psychological, and economic impacts of COVID-19 on cancer patients.

Methods

The systematic search, conducted in March 2021, captures the experience of COVID-19 Wave I, when the most severe restrictions were in place globally, from a patient perspective.

Results

The search yielded 56 studies reporting on the economic, social, and psychological impacts of COVID-19. The economic burden associated with cancer for patients during the pandemic included direct and indirect costs with both objective (i.e. financial burden) and subjective elements (financial distress). The pandemic exasperated existing psychological strain and associated adverse outcomes including worry and fear (of COVID-19 and cancer prognosis); distress, anxiety, and depression; social isolation and loneliness. National and institutional public health guidelines to reduce COVID-19 transmission resulted in suspended cancer screening programmes, delayed diagnoses, postponed or deferred treatments, and altered treatment. These altered patients’ decision making and health-seeking behaviours.

Conclusion

COVID-19 compounded the economic, social, and psychological impacts of cancer on patients owing to health system adjustments and reduction in economic activity. Identification of the impact of COVID-19 on cancer patients from a psychological, social, and economic perspective following the pandemic can inform the design of timely and appropriate interventions and supports, to deal with the backlog in cancer care and enhance recovery.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-022-07178-0.

Keywords: Cancer, Covid-19, Economic, Psychological, Social

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of death globally, with almost 10 million deaths and 19.3 million incidences worldwide in 2020 [1]. This has a significant economic burden globally, estimated at $1.16 trillion in 2010 [2]. Such cost estimates capture expenditure on several types of cancer care, depending on prevalence, treatment patterns, and pharmaceutical spend. However, the economic burden of cancer extends beyond the costs of healthcare delivery. Patients and survivors also face objective costs (i.e. financial burden), arising from out-of-pocket payments. These vary depending on the public healthcare system in which they are treated, and insurance coverage. Additionally, there are subjective costs (financial distress) [3], which incorporates the psychological consequences and coping behaviours associated with the financial burden of cancer. Financial distress has adverse effects on health outcomes, collectively affecting quality of life (QoL) and well-being [3]. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted health services globally. Cancer patients were particularly vulnerable to its adverse impacts given their reliance on the healthcare system, and their weakened immune systems.

Here, we investigate the social, psychological, and economic costs of the pandemic on cancer patients. National and institutional public health guidelines issued to protect against COVID-19 both influenced cancer care. Stay-at-home orders, social distancing, reconfigured healthcare delivery, reduced healthcare capacity, and re-distributed resources were needed to meet the demands of COVID-19. This in turn negatively impacted cancer care.

This systematic review examines the social, psychological, and economic impacts of COVID-19 on cancer patients. The systematic search, conducted in March 2021, captures the experience of COVID-19 Wave I, when the most severe restrictions were in place globally. Taking a patient perspective, the findings provide reflections on how cancer care for patients undergoing treatment was affected by the pandemic. Consideration is given to innovations arising during the pandemic and lessons learned for designing future developments and supports, which are to mitigate the social, psychological, and economic impacts associated with cancer.

Methods

Study selection criteria

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the principles of conducting systematic reviews [4]. The PICOCS framework (i.e. population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, context, studies) was used to support inclusion criteria [5] (see Table 1). (There was a minor adaptation including “context” and excluding “comparator” as it was not applicable.) Studies published between January 2020 and March 2021 examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult cancer patients undergoing treatment and survivors (2 years post-diagnosis) were examined. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. Studies included were limited to those written in English and focused on the economic, social, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients/survivors. Table 2

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| PICOS framework | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult population (> 18 years old) Current cancer patients and survivors (2-years post-diagnosis) | Caregivers, nursing, and medical staff and paediatric cancer patients |

| Intervention | COVID-19 pandemic | - |

| Outcome | economic, social, and psychological implications of COVID-19 on cancer patients/survivors | - |

| Context | Hospital and community setting | - |

| Studies | Full-text articles, patient perspective, observational, cross-sectional, prospective, longitudinal, retrospective | Letters to the editor, editorials, case studies, reports, protocols, commentaries, short communications, reviews, opinions, perspectives, and discussions |

Table 2.

Search terms

| Population | Intervention | Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer patients | COVID-19 | Economic impact | Social impact | Psychological impact | Health impact |

| "cancer" OR "oncology" OR "malignant" OR "tumour" OR "metastasis" OR "neoplasm" | “covid-19" OR "coronavirus" OR "2019-ncov" OR "sars-cov-2" OR "cov-19" OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2" OR "pandemic" | "financial toxicity" OR "out-of-pocket" OR "productivity" OR "absenteeism" OR "unemployment" OR "cost" OR "waiting time" OR "expenses" OR "financial stress" OR "inconvenience" OR "opportunity cost" OR "income" | "well being" OR "social isolation" OR "exclusion" OR "loneliness" OR "happiness" OR "life satisfaction" | "fatigue" OR "insomnia" OR "psychological distress" OR "emotional distress" OR "anxiety" OR "depression" OR "post-traumatic stress disorder" OR "psychological" | "quality of life" OR "health-related quality of life" OR "survival" OR "mortality" OR "disease progression" OR "diagnosis" OR "screening" OR "recurrence" OR "disease stage" OR "delay" OR "support" OR "surgery" OR "treatment" OR "target therapy" OR "radiotherapy" OR "chemotherapy" OR "immunotherapy" OR "hormone therapy" OR "survivorship programme" OR "follow-up-care" |

Literature search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was employed using a combination of free-text words and subject headings relevant to CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PsycArticles, and EMBASE databases and refined using Boolean operators. Searches were performed on the 31st of March 2021. Full search terms and combinations are provided in Appendices 1 and 2. The search protocol was registered (CRD42021246651).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction is presented in tabular format to assist reporting uniformity, reproducibility, and minimising bias (provided on Table 3). The evidence was combined and summarised using a narrative synthesis. Methodological quality of studies was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools (for cross-sectional, prevalence, cohort, and qualitative studies) and the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list for cost analyses. Two authors performed quality assessment independently (AL and AK). If there was conflict or uncertainty, a third author was consulted. Risk of bias in a study was considered high if the “yes” score was ≤ 4; moderate if 5–6; and low risk if the score was ≥ 7 on the JBI tools. Quality review results are presented in Appendix 3.

Table 3.

Extraction summary

| Author, year Country Type of cancer | Aim | Perspective Study design Sample size Age | Data source Context and setting Study timeframe | Data collection methods Data analysis methods | Results: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Akhtar et al. (2021) India Multiple |

To describe the hospitals’ experience during the first 6 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, including the functioning of our department, clinical outcomes, the problems faced by the patients, and the lessons learned |

NA Retrospective N = 1 institution NA |

Secondary data: hospital record database Primary data: questionnaire Hospital setting April to September 2019 and 2020 |

• Hospital data • Patient data of difficulties encountered •Desc. stats • χ2 tests |

• Outpatient consultations reduced by 62% (2019 (20,822) vs 2020 (7973)) • Inpatient admissions reduced by 58% (2019 (2840) vs 2020 (1184)) • Chemotherapy unit reduced by 56% (2019 (4896) vs 2020 (2150)) • 31% reduction in major surgeries across all sites • Higher % head and neck surgeries (absolute % are lower than those in 2019) • Average 82 patients operated by surgeons vs 119 in 2019 • Increase in telehealth and oral counterparts • High number of no-shows due to misinformation, fear of infection: • 400 patients on waiting lists for surgery did not show up Reasons: • 52% apprehension of COVID‐19 infection • 47% unawareness about the functioning of the department Difficulties faced by patients: • 58% lack of transportation • 52% apprehension of COVID‐19 infection • 17% had logistic issues • 49% inability to arrange finances • 36% had financial issues, 46% missed consultations due to financial difficulties |

|

Baffert et al. (2021) France Multiple |

To examine cancer patients’ medical management during the COVID-19 pandemic, satisfaction with care management, quality of life, and anxiety |

Patient Cross-sectional, prospective, observational N = 189 > 18 years old |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting May to June 2020 |

Questionnaire using: • GAD-7 scale • SF-12 scale • Patient satisfaction using a numerical scale •Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Fisher’s exact tests • Mann–Whitney U-test |

•6% of appointments were postponed • Patients had low anxiety scores (mean: 3.2 ± 4.5) • 21 patients (11.1%) had anxiety with a GAD-7 score > 10 • 6 (3.1%) had high anxiety (GAD7 ≥ 15) • Before COVID-19, the mean physical health score was 48.5 and mean mental health score was 42.6 • After 4 weeks, physical health remained stable (mean: 46.7) but mental health decreased (mean 36.1; p < 0.0001) • Risk factors of anxiety included female gender and those who lived in a city apartment • Physical health score was better in patients who lived in a city apartment • Mental health score was better in patients who lived in individual houses • Factors influencing better HRQoL include retired patients, patients with children, aged > 60 years |

|

Bakkar et al. (2020) Jordan Thyroid |

To assess the impact of COVID-19 measures on thyroid cancer treatment plans |

Patient and provider Retrospective N = 12 > 18 years old |

Secondary data: medical records Primary data: anxiety scale Hospital setting 17 March to 20 May 2020 |

• Medical records • HAM-A scale •Desc. stats |

• All surgical procedures were performed without delay as no patients had symptoms of COVID • Additional delay in receiving conventional RIA experienced by 2 patients (17%) placed them in the mild-to-moderate anxiety group according to the HAM-A scale • 50% (6/12) patients had additional extra personal cost of 1000 JOD per patient due to treatment modification |

|

Bäuerle et al. (2021) Germany Multiple |

1.To analyse individual changes in cancer patients’ mental health before and after the COVID-19 outbreak 2.To explore predictors of mental health impairment |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 150 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 16–30 March 2020 |

•Online survey using: •EQ-5D-3L •GAD-2 •PHQ-2 •Distress scale •COVID fear Likert scales •Desc. stats • Regression analysis |

• Health status deteriorated since the COVID-19 outbreak (p = 0.004) • There was no predictor for reported change in health status • Increase in depression (p = 0.01), anxiety symptoms (p = 0.001), and distress (p = 0.001) • The prevalence of major depression, severe generalised anxiety, and enhanced distress all increased after the outbreak • COVID-related fear was a predictor of increased depression and generalised anxiety symptoms |

|

Biagioli et al. (2020) Italy Multiple |

To investigate the perception of self-isolation at home in patients with cancer during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 195 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: online survey Web-based 29 March to 3 May 2020 |

•ISOLA scale •Desc. stats • Qualitative content analysis |

• 37.3% of participants were “very or extremely” afraid of going to hospital because of the COVID-19 outbreak • 24.5% were “very or completely” afraid that their cancer care would become less important and that this would have a negative impact on their prognosis • 39.5% of patients had been in self-isolation for > 6 weeks • 60% rarely left their home • 41% of patients reported changes in their relationships with family (avoiding kisses and hugs) (n = 61, 31.9%) and practising social distancing (n = 23, 12%) • Risk factors for feeling more isolated include less education and were living without minor children • 53.8% believed they were at a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection than the general population • Worried about financial difficulties and employment |

|

Campi et al. (2020) Italy Urological |

To explore urological patients willing to defer their planned surgical interventions to offer insight of patient perspective and shared decision-making |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 2 referral centres N = 332 (171 scheduled for oncology surgery) Adults |

Primary data: interviews Hospital setting Between 24 and 27 April 2020 |

• Structured telephone interview • Frailty measured by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score • Clinical and demographic info. from hospital databases •Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Mann–Whitney tests |

• 47.9% patients would defer planned surgical intervention • 85% of them would be willing to postpone it for at least 6 months • Patients < 60 years old, frail (ASA ≥ 3), and those with underlying conditions were more willing to postpone surgery • Malignant cancer patients (33.3%) were less willing to cancel appointments compared to benign (63.4%) • 54.8% patients considered the risk COVID-19 during hospitalisation potentially more harmful than the risk of delaying surgery • Older patients were more worried about the risk of COVID-19 infection |

|

Catania et al. (2020) Italy Lung |

To better understand patients’ fears and expectations of cancer patients during the pandemic period |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 156 Adults |

Primary data: interview Hospital setting 30 April to 29 May 2020 |

• Structured interview • Desc. stats • Logistic regression • Fisher’s exact test • Odds ratio |

• 56% reported not at all/a little worsening of QoL • 40% were afraid of COVID •55.1% in Q1 and 60.3% in Q2, respectively, reported not at all/a little worried about COVID-19 • 20% in Q1 and 14.1% in Q2 reported being quite a bit/extremely worried • 57% being more worried by their lung cancer than by COVID-19 • 17% reported more worried about COVID-19 than lung cancer • 56% reported not at all/a little worsening of QoL • Patients with comorbidities experienced fear of COVID-19 • Patients who had already received (radiotherapy or surgery) experienced more fear of COVID-19 • Females experienced more fear of COVID-19 |

|

Chaix et al. (2020) France Breast |

To assess psychological distress amongst at-risk populations during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 1771 (360 = cancer) Adults |

Primary data: survey Web-based: 4 Vik chatbox 31 March to 7 April 2020 |

• A self-report questionnaire using: • PDI scale •Desc. stats • ANOVA •Binomial logistic regression |

• The mean PDI score breast cancer = 10 • 34% (123) had psychological distress with a score ≥ 14 • Risk factors for a higher PDI score include having depression (p < 0.001) • Risk factors for a higher PDI include being a woman (p = 0.004) and unemployed (< 0.001) |

|

Chia et al. (2021) China Multiple |

To explore the emotional impact of and behavioural responses to COVID-19 amongst cancer patients and their caregivers |

Patients and caregivers Qualitative N = 30 (16 patients, 14 caregivers) ≥ 21 years old |

Primary data: semi-structured interview Hospital setting 9th and 13th of March 2020 |

• A semi-structured interview •Thematic analysis |

• COVID-19 was the most prominent source of threat that elicited fear, worry, and perceptions of vulnerability • Threat was more pronounced in patients • Patients were concerned about personal vulnerability • Worried about impact on healthcare and prioritising cancer/treatment disruptions |

|

Charsouei et al. (2020) Iran Breast |

To investigate the perceived stress and its effect on the quality of life (QoL) and coping strategies of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 61 Adults |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 20 February to 21 May 2020 |

Survey using: •Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) •SF-36 questionnaire-QoL •Moos’ Coping Checklist • Desc. stats • Pearson’s correlation • ANOVA |

• High scores for problem- and emotion-focused strategies were for patients with no history of radiotherapy, and attended more than 20 chemotherapy sessions • Overall perceived stress level scores were high • Higher stress was in patients with academic degree, those with a history of mastectomy, and those who attended more than 20 chemotherapy sessions • Overall QoL scores were low • Overall score of coping strategies was high • Higher stress levels mainly used problem-focused coping strategies rather than emotional-focused strategies • High scores for problem- and emotion-focused strategies were patients > 60 years old |

|

de Joode et al. (2020) Netherlands Multiple |

To assess the impact of this pandemic on oncological care |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 5302 Adults |

Primary data: survey Web-based 29 March to 18 April 2020 |

•Online survey •Desc. stats • χ2 tests |

• 30% of all respondents experienced some consequences for their treatment or follow-up due to the pandemic • The most frequently adjusted therapies were chemotherapy and immunotherapy • The most frequently reported consequence was the conversion to consultation by phone or video (52%) • 39 of 250 patients’ treatments were postponed • 279 of 2391 patients awaiting and under treatment • 49 of 250 patients experienced treatment changes (adjustment, delay, and discontinuation of treatment), while 480 of 2391 were awaiting and under treatment • Most patients with curable disease continued their treatment unchanged • Incurable patient’s treatment was more frequently postponed • 47% of respondents were (very) concerned to be infected with COVID-19 • Among patients with delay and discontinuation of treatment, 55% and 62% of patients were concerned, respectively • Among patients who did not experience consequences yet, 24% of patients were (very) concerned about potential consequences for their treatment or follow-up • Patients with cured disease or follow-up, 87% and 83% of patients were not/slightly concerned, respectively. Incurable patients were more concerned of COVID-19 infection • Patients who were under treatment were more often (very) concerned to be infected than patients in follow-up • 19% of patients were reluctant to contact their hospitals during the pandemic |

|

Deshmukh et al. (2020) India Multiple |

1. To critically assess and quantify the response of a small single specialty cancer centre to the pandemic 2. To analyse the impact of a pandemic of this magnitude on cancer patients’ treatment |

NA Retrospective N = 1 institution N = 3 departments NA |

Secondary data: hospital records Hospital setting Pre-COVID: 22 March to 31 May 2019, 2018, 2017 Lockdown: 22 March to 31 May 2020 |

•Hospital data •Desc. stats |

• During the lockdown period: 28 patients underwent surgery, 469 underwent CT, and 56 patients underwent RT • In 2019: 929 patients underwent surgery, 7355 underwent CT, and 1037 underwent RT • Number of surgeries in 2020: 16 head and neck surgeries and 12 other malignancies • Number of surgeries in 2019: 366 head and neck surgeries and 563 other malignancies • Average number of patients treated per week in surgical department in the lockdown period dropped to 5.2 (from a range of 14 to 21 for the other 3 years) • CT and RT average number remained stable • Financial pressure of increased hospital length and COVID-19 testing |

|

Elran-Barak and Mozeikov (2020) Israel Multiple |

1. To examine how the lockdown measures impacted the self-rated health (SRH), health behaviours, and loneliness of people with chronic illnesses 2. Determine socio-demographic or medical-related factors linked to a decline in SRH |

Patient cross-sectional N = 315 (64 cancer patients) > 18 years old |

Primary data: online survey Web-based 20 to 22 April 2020 |

Online survey using: • SF-36, medical outcomes • The Challenges to Illness Management Scale • The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale • Desc. stats • T-tests • Ordinal logistic regression •ANOVA • χ2 tests |

• 47.2% reported a decline in their physical health • Changes in physical health for cancer/autoimmune by an average of 3.53 (SD = 0.78) • Changes in general health by an average of 3.08 (SD = 0.82) • 50.5% reported a decline in mental health during the first month of the COVID-19 outbreak • Sense of loneliness was statistically significant among all patients (T = 12.76, p < 0.001) • Feelings of loneliness amongst cancer/autoimmune group scored an average of 5.66 (SD = 2.15) • Changes in mental health scored an average of 3.48 (SD = 0.77) Decline in general SRH was predicted by: • Female gender (p = 0.016), • Lack of higher education (p = 0.015) • Crowded housing conditions (p = 0.001) • Illness duration (p = 0.010) |

|

Erdem and Karaman (2020) Turkey Multiple |

1. To assess the knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of patients with cancer towards the COVID-19 pandemic 2. To measure the effect of COVID-19 on cancer patients’ ongoing treatments |

Patient Prospective cross-sectional N = 300 19–92 years old |

Primary data: questionnaire survey Hospital setting 1 to 30 April 2020 |

• Survey questionnaire •Desc. stats •Kolmogorov–Smirnov test •Shapiro–Wilk test • T-test • χ2 tests • Fisher–Freeman–Halton Exact test •Fisher’s exact |

• 98% had no delay for current cancer treatments or follow-up appointments • 52.3% using nutritional supplements • One-third of patients were afraid to leave their house • One-third of patients left their house only for the hospital during this period • 96% prefer not to use public transport due to risk of COVID-19 • One-third of patients never left their house • 97% of patients did not accept visitors to their houses • Two-thirds of patients went out with a mask • 97.3% were washing their hands more often than usual • Patients over 65 years old were most prone to stay at home • Male patients were more likely to leave their home • Patients with stage 1 cancer tend to stay at home, while patients with stage 4 cancer were more likely to leave their houses for hospital visits at a higher ratio • Patients with less than high school degree were more prone to stay at home • Higher educational status was associated with better knowledge of routes COVID transmission |

|

Fox et al. (2021) UK Multiple |

To determine if there were gender differences in participants’ concerns about taking part in cancer research and anxiety levels of cancer patients during the pandemic |

Patients Cross-sectional N = 93 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Web-based 5th and 19th of June 2020 |

• Online survey using: • GAD-7 • Desc. stats • Kruskal–Wallis tests • Linear regression • χ2 tests • T-tests |

•Higher concerns of risk include previously received cancer treatment and varied by type of cancer • Females were less likely to participate, or would not participate, in research due to COVID-19 • Females had a significantly higher score for “Total concerns” category (p-0.004) and anxiety levels (p < 0.001) • Age and travel for treatment were concerns for COVID-19 risk |

|

Frey et al. (2021) USA Ovarian |

To assess coping strategies employed by women with ovarian cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Survivors Cross-sectional N = 408 NA |

Primary data: survey Secondary data: quality of life and treatment interruptions 30 March to 13 April 2020 |

• Online survey using: • Brief COPE framework •Desc. stats |

•33.9% (113) reported a delay in some component of their cancer care • 8.6% reported that their treatment was postponed •27.6% reported surgery was delayed Adaptive coping strategies: • Emotional support (39%) • Self-care (36.3%) • Hobbies (34.1%) • Humour (1.7%) • Planning (21.3%) • Positive reframing (13.2%) • Religion (12.3%) • Instrumental support (9.3%) • Acceptance (3.9%) Dysfunctional strategies: • Substance use (4.7%) • Venting (2.9%) • Behavioural disengagement (1.5%) • Self-distraction (27.2%) • Self-blame (0.5%) |

|

Frey et al. (2020) USA Ovarian |

1. To evaluate the quality of life of women with ovarian cancer during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic 2. Evaluate the effects of the pandemic on cancer-directed treatment |

Patients and survivors Cross-sectional N = 555 20–85 years old |

Primary data: survey Web-based 30 March to 13 April 2020 |

• Online survey using: • HADS scale • Cancer Worry Scale • T-test • ANOVA • Mann–Whitney U test • Kruskal–Wallis test • Linear regression |

• 16.6% worried about QoL and wellness • 33% experienced a delay in cancer care • 26.3% scheduled for surgery experienced a delay • 24% had a delayed physician appointment • 25% used telemedicine for gynaecologic oncology care • Adaption of telemedicine was associated with higher levels of cancer worry • 26.9% worried about access to care • 58% worried about COVID-19 infection • 57% worried about cancer recurrence • 89% reported significant cancer worry • Younger age, presumed immunocompromised, and delay in care were associated with a significant increase in cancer worry, anxiety, and depression • 51.4% (285) borderline or abnormal anxiety, and 26.5% (147) borderline or abnormal depression • Age < 65 years was associated with higher levels of worry • 10% were concerned about social isolation • 24.3% were concerned about the financial implications of COVID-19 |

|

Gebbia et al. (2020) Italy Multiple |

To investigate if instant messaging systems are useful to oncologists to care for patients with cancer and to mitigate patient anxieties and fears during the COVID-19 outbreak? |

Patient Observational N = 446 ≥ 18 years |

Secondary data: patient queries Hospital setting 8 to 22 March 2020 |

• Spontaneous patient queries were collected through a chat text •Desc. stats •Sentimental analysis • χ2 tests |

• 37% asked if they can postpone their appointments • 198 follow-up visits were delayed after queries or independent oncologist suggestions • 5 patients asked for a delay in adjuvant radiotherapy • A majority of delays were in patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer with programmed follow-up visit • Majority of queries came from the most prevalent cancers (breast, lung, colon, prostate) • Fear was the most common emotion • Fear, anger, and sadness most dominant negative emotions • 57% showed negative emotion • 43% showed positive emotions • 50% felt trust • Patients > 75 years old more commonly requested visit/treatment delays |

|

Gheorghe et al. (2020) Romania Multiple |

1. To describe the level of knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) related to COVID-19 among cancer patients 2. To evaluate the effectiveness of pandemic response measures |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 1585 patients, N = 7 hospitals Adults |

Primary data: questionnaire survey Hospital setting 27 April to 15 May 2020 |

• Questionnaire • Desc. stats • Regression analysis |

•Better knowledge of COVID-19 was associated with patients aged between 40 and 54 years, higher education programme, female, urban areas, profession of mental labour, higher income • 68% considered cancer as an additional risk for infection with SARS-CoV-2 • 27.8% would rather not vaccinate • 8.8% believed risk of infection justifies delaying/stopping oncological treatment • 55.5% declared being compliant with COVID protective measures • Distress of risk of COVID-19 was higher, compared to influenza virus • 32.6% were “very worried” about getting infected with the coronavirus or developing COVID-19 • 35.9% were “somewhat worried” • 11.6% feared COVID-19 infection more than cancer progression • 61.8% feared of both events in equally • Those with low income, low socioeconomic status, and higher education were more worried about COVID-19 • Very few patients would rather stop their treatment |

|

Ghosh et al. (2020) India Multiple |

To assess the mindset of patients about continuation of anticancer systemic therapy during this pandemic |

Patient Prospective observational N = 302 patients ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 1 to 10 April 2020 |

•Questionnaire-based survey •Desc. stats • χ2 tests • T-tests • Fisher’s exact test • Pearson’s correlation |

• 203 (68%) patients wanted to continue chemotherapy, 40 (13%) wanted to defer, and 56 did not know (19%) • No correlation of intent of treatment with chemotherapy willingness • Knowledge of COVID-19 was almost evenly distributed among well informed, moderately informed, and minimally informed Worried about COVID-19 infection: • Very much, 58 (19%) • Moderate, 126 (42%) • Minimal, 118 (39%) • Worry about disease progression was more common in palliative patients • Fear of COVID-19 over cancer directly correlated with higher knowledge about immunosuppression • Patients were predominantly bothered about deferring chemotherapy (45), visiting hospitals (50), both (100), or about cancer progression (104) if therapy deferred |

|

Goenka et al. (2020) USA Not specified |

Review implementation of telemedicine 1. Patient access to care 2. Billing implications |

Provider Observational N = 1 institution 22–93 years old |

Secondary data: hospital data Hospital setting 1 January to 1 May 2020 |

•Telemedicine platform • Desc. stats • Logistic regression |

• 2997 billable evaluation and management encounters occurred • 35% decrease in billable activity • In-person visits decreased from 100 to 21% • 60% were 2-way audio–video • 40% by telephone only • Older patient age was less likely to have 2-way audio–video encounters • The financial impact of the transition to telehealth must be considered including the cost of telehealth implementation and maintenance, the number of second opinion consults, the difference in reimbursement, cost savings to patients (direct and indirect), and cost savings from care coordination |

|

Greco et al. (2020) Italy Prostate renal |

To investigate the impact of postponement of surgeries due to the COVID-19 on the on HRQOL of uro-oncologic patients |

Patients Cross-sectional N = 50 Adults |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 1 March to 26 April 2020 |

• SF-36 questionnaire • Desc. stats |

• 86% reported normal physical functioning but loss of energy • Most patients reported change in emotional functioning: increase in anxiety and depression • All patients perceived a reduction in general health condition |

|

Gultekin et al. (2020) Europe Gynaecological |

To capture the patient perceptions of the COVID-19 implications and the worldwide imposed treatment modification |

Patients Prospective 16 EU countries > 18 years old |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 1 to 31 May 2020 |

• COVID-19-related questionnaire • HADs scale •Desc. stats • Logistic regression |

• 71% were concerned about cancer progression if their treatment/follow-up was cancelled/postponed • 64% had their care continued as planned • 5.1% said that their surgery was delayed • 7% said that their imaging was cancelled or disrupted • 2.8% reported a delay in their chemotherapy or radiotherapy (0.5%) appointments • 12.8% reported follow-up was postponed or delayed • Mean HADS Anxiety and Depression Scores were 8.8 and 8.1 respectively • 35.3% had an abnormal HADS Anxiety score • 30.6% had an abnormal depression score • Treatment modifications of care and concerns of care were predictors of patients’ anxiety • 7.4% patients reported not attending their treatment/follow-up appointments due to fear of COVID-19 infection • 17.5% were more afraid of COVID-19 than their pre-existing malignant diagnosis • 53.1% expressed their fear of contracting COVID-19 from the hospital • Those aged 70 years or older were more afraid of COVID-19 compared to cancer (p < 0.001) |

|

Han et al. (2020) China Multiple |

To assess the psychological status and symptoms of cancer survivors and family members compared to Chinese norms |

Survivors and family members Longitudinal N = 111 33–75 years old |

Primary data: survey Web-based T1: 14 to 24 February T2:1 to 10 April T3: 15 to 25 May 2020 |

• Online questionnaire using: • Symptom checklist 90 (SCL-90) •Desc. stats • MANOVA • T-test |

• Survivors’ mean total score of the SCL-90 for T1: 172.05 (SD = 13.30), T2: 155.91 (SD = 12.18), T3: 142.75 (SD = 11.56) • Survivors’ SCL-90 score was significantly higher than that of their family members • Family members had significantly higher SCL-90 scores than Chinese norms (T = 3.03, p = 0.001) • Somatisation, depression, anxiety, and phobic anxiety scored the highest on the SCL-90 scale for survivors |

|

Hill et al. (2021) USA Ovarian |

1. To examine the role of intolerance of uncertainty (IU) in psychological distress (PD) among women with ovarian cancer 2. Fear of COVID-19 |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 100 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Web-based 1 July and 30 October 2020 |

• Online survey using: • Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale • Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCS) • Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) • Desc. stats • Linear regression |

• Depression and anxiety models were significant • Higher levels of IU were associated with depressive symptoms • Lockdown status of the geographic area (red or yellow status) was associated with increased depressive symptoms • Fear of COVID was not significant for depressive symptoms • Fear of COVID was the strongest predictor for anxiety • Fear of COVID and Intolerance of Uncertainty were strongly correlated • Stress model was significant with IU the strongest predictor |

|

Islam et al. (2020) USA Not specified |

1. To evaluate COVID-19-related preventative measures among cancer survivors 2. To examine behaviours related to cancelling or postponing activities, specifically doctors’ appointments |

Survivors Cross-sectional N = 854 ≥ 18 years |

Secondary data: from the US COVID-19 Household Impact Survey. Primary data: interview Community based Week 1 (April 20–26, 2020), week 2 (May 4–10, 2020), week 3 (May 30–June 8, 2020) |

• Sample from the national household survey •Telephone and face-to-face interviews •Demographic details from the 2020 Current Population Survey • COVID-19 deaths were obtained from USA facts •Desc. stats •Regression analysis |

• Between April and May, the proportion of cancer survivors that cancelled a doctor or dentist's appointment increased from 35 to 52% and 36 to 49%, respectively • Preventative behaviours amongst cancer survivors compared to the general population were statistically significantly more likely to wash or sanitize their hands, social distance, wear a face mask, avoid public or crowded places, avoid some or all restaurants, avoid contact with high-risk people, and cancel pleasure, social, or recreational activities • Cancer survivors were also more likely to cancel doctor appointment or postpone a dentist or other appointment compared to the general population •Widowed/divorced/separated were less likely to cancel doctor’s appointments compared with those who were married • Those aged 18 to 29 were more likely to cancel a doctor’s appointment compared with those aged 60 years and above • H-Black survivors are less likely to cancel a doctor’s appointment when compared with NH-White survivors •Female and co-morbid survivors were more likely to cancel appointments |

|

Jeppesen et al. (2020) Denmark Multiple |

To investigate patient's quality of life (QoL), emotional functioning, and concerns about COVID-19 |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 4571 > 18 years old |

Primary data; survey Hospital setting 15 to 29 May 2020 |

• Online survey using: • EORTC QLQ-C30 instrument-Health-related quality of life •Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Linear regression model |

• 9% of all patients with cancer had refrained from consulting a doctor or the hospital due to fear of COVID-19 infection • 80% were concerned about contracting COVID-19 • Female, comorbid, conditions, incurable cancer, or receiving medical cancer treatment was associated with higher concern of contracting COVID-19 • Concerns of contracting COVID-19 infection were correlated with lower QoL and the emotional functioning scores • Higher quality of life was correlated with older age, not living alone, employed, fewer comorbidities, and not receiving treatment within the last 2 months • Patients with brain tumours, and endometrial/cervical/vulva and thoracic cancers had lower quality of life score • Better emotional functioning was correlated with male gender, older age, fewer comorbid conditions, and not receiving treatment within the last 2 months |

|

Juanjuan et al. (2020) China Breast |

To evaluate patient-reported outcome in patients with breast cancer and survivors |

Patients and survivors Cross-sectional N = 658 N = 12 cancer centres NA |

Primary data; survey Hospital setting 16 to 19 February 2020 |

• Online survey using: • GAD-7 scale • PHQ-9 scale • Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) • Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) • Desc. stats • Wilcoxon rank-sum test • Kruskal–Wallis test • Logistic regression |

• 46.2% of patients had to discontinue or modify their planned necessary anticancer treatments • Poor general condition, treatment discontinuation, and metastatic breast cancer were more likely to experience severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and distress • Mean score for GAD-7 = 6.01 (SD = 5.35) •34.0%, 13.3%, and 8.9% patients categorized into the mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively • Mean score for PHQ-9 = 5.80 (SD = 5.66) • 25.2%, 12.8%, and 9.3% patients who reported mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively • Mean score for ISI = 8.66 (SD = 6.29) • 36.2%, 12.9%, and 4.0% patients, respectively, who reported mild, moderate, and severe insomnia • IES-R total = 28.17 (SD = 18.23) • 30.7%, 31.5%, and 20.8% patients who described mild, moderate, and severe distress symptoms |

|

Kamposioras et al. (2020) England Colorectal |

1. To investigate the perception of service changes imposed by COVID-19 2. To identify the determinants of anxiety in patients with colorectal cancer |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 143 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 18 May to 1 July 2020 |

• Survey using: • GAD-7 scale •Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Fisher exact test • Logistic regression |

• 78% participants had telephone consultation (83% met needs) • 40% had radiologic scan results discussed over the phone (96% met needs) • 90% felt safe visiting their hospital • 10% participants who had their assessment scans delayed or cancelled • 18% participants were considered to have anxiety (score ≥ 5) • 5.5% scoring for moderate or severe anxiety • 80% were concerned about COVID-19 infection • 87% denied that they were more concerned about COVID-19 than their cancer • Patients concerned about COVID-19 infection, effects on mental health, and cancer care were most likely to have anxiety • 97% reported that they were well-supported by their families and friends |

|

Kim et al. (2021) South Korea Breast |

Explore whether COVID-19–related treatment changes (delays, cancellations, changes) influenced fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 154 ≥ 20 years |

Primary data: survey Web-based April to June 2020 |

• Online survey using: • Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (K-FCRI) • HAD scale • Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Fisher’s exact test • T-test • ANOVA |

• 18.8% had experienced COVID-19-related treatment changes • 24.1% had treatment plan changes • 62.1% experienced delays • Follow-up or tests were the most frequently delayed care • 31% treatments were cancelled • Fear of cancer recurrence was higher in patients receiving radiation therapy • Depression was more severe in patients receiving chemotherapy • 15% had moderate to severe levels of anxiety • 24.7% had moderate to severe levels of depression • Changes of the treatment plan had a significant correlation with depression (t = 2.000, p = .047) • Fear of cancer recurrence was high (mean score, 84.31 (SD 24.23) • 49.2% felt anxious about getting COVID-19 infection when in hospital for treatment • Participants who experienced treatment changes were younger, were not married, had no children, or lived more than 2 h from the hospital. Fear of cancer recurrence was significantly higher among unmarried and no children • Anxiety was more severe in lower income households • Depression was more severe in those who were unmarried, had no children, had a lower income • 6.21% felt an economic burden as testing for COVID-19 • Anxiety was more severe in those who reported a financial burden |

|

Košir et al. (2020) Worldwide Not specified |

1. To gather evidence of the impact of COVID-19 on AYA cancer patients’ and survivors’ psychological well-being and cancer care 2. To understand where they received the information about the pandemic and how satisfied they were with the resources on COVID-19 |

Patients and survivors Mixed methods, cross-sectional N = 177 18–39 years old |

Primary data: survey Web-based 6 April to 11 May 2020 |

• Online survey using: • PHQ-4- depression and anxiety •Desc. stats •Qualitative content analysis |

• 45% reported an impact on their cancer treatment. (postponed or cancelled, virtual care, reduced access to medicines) • Individuals undergoing treatment (or within the last 6 months) reported higher levels of psychological distress on average • 62% of respondents reported feeling more anxious than they did before the pandemic • 52% reported feeling more isolated than before the pandemic. Missed social interactions, low mood • Most common concern was contracting COVID-19 • 56% reported wanting more information about how to cope with the pandemic |

|

Leach, et al. (2021) USA Breast, Male other and female other |

To examine cancer survivor worries about treatment, infection, and finances early in the US COVID-19 pandemic |

Survivors Cross-sectional N = 972 quantitative, N = 659 for qualitative question ≥ 18 years |

Primary data; survey Web-based 25 March to 8 April 2020 |

• Online survey •Desc. stats • Logistic regression analysis • Thematic analysis |

• Female other cancers and male survivors were more worried about treatment disruption • Female breast cancer and female other cancers were more worried about health impacts • 77% were worried about risk COVID-19 infection • Longer time since last treatment was associated with less worry • Delayed appointments due to fear of getting COVID sometimes led to greater anxiety, worry about recurrence, and health complications • Fear of rationing of care as seen as not eligible for COVID treatment • Age, education, marital status, and race/ethnicity were not associated with treatment worry or COVID-19 worry • Patients reported loneliness and feelings of being isolated due to social distancing • Non-Hispanic white, married, more educated, and older were associated with less financial worry • Concerns included employment, economic downturn, inability to pay for expensive healthcare costs (refill prescriptions and insurance deductibles) |

|

Lou, et al. (2020) USA Multiple |

To compare concerns about COVID-19 among individuals undergoing cancer treatment to those with a history of cancer not currently receiving therapy and to those without a cancer history |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 543 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Web-based 3 to 11 April 2020 |

• An online survey using: • GAD-7 scale • PHQ-8 scale • χ2 tests • ANOVA • Fisher’s exact tests • T-test |

• 20% reported changes in care • 50.8% metastatic patients reported COVID-19 had negatively affected their cancer care (31% non-metastatic) • Chemotherapy delays most common • More than 90% in active treatment feared COVID infection • 40% expressed concerns about effects on their cancer-directed therapy plans • Higher levels of family distress • Anxiety and depression did not differ significantly between patients actively being treated for cancer vs no history of cancer |

|

Mahl et al. (2020) Brazil Head and neck |

To evaluate delays in care for patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) in post-treatment follow-up or palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic; i.e. self-perception of anxiety or sadness, fear of COVID-19 infection, cancer-related complications during social isolation, self-medication, diagnosis of COVID-19, and death between patients with and without delayed cancer care |

Patient cross-sectional N = 1 institution N = 31 patients NA |

Primary data: interview Secondary data: medical records Hospital setting 1 January to 30 July 2020 |

• Telephone interviews • Desc. stats • Mann–Whitney U test • Fisher’s exact test |

• 58.1% had delayed cancer care (18/31) • No report of telemedicine use • Increase in self-medicating in patients who had delayed treatment • Fear of COVID infection: 41.9% (n = 13) • Feelings of anxiety: 71.0% (n = 22) • Sadness 45.2% (n = 14) |

|

Mari et al. (2020) Italy Multiple |

1. To determine the extent the pandemic has had on surgical procedures for cancer, benign, and emergency cases 2. Perform a cost analysis |

Provider Retrospective N = 4 hospitals NA |

Secondary data: hospital data Hospital setting March, April and May 2019 and 2020 |

• Surgical volumes from surgical registries from 4 different hospitals •Desc. stats • Cost analysis of hospital revenue |

• 60.1% reduction in cancer surgeries from 403 to 161 • 81.6% reduction in overall surgeries • 57.3% reduction in state funding for cancer surgical procedures performed. Reimbursement falling from €2.3 million to €967,333 between 2019 and 2020 |

|

Massicotte et al. (2020) Canada Breast |

To examine stressors related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and their relationships with psychological symptoms (i.e. anxiety, depression, insomnia, and fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) in breast cancer patients undergoing cancer treatments) |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 36 18–80 years old |

Primary data: questionnaire Hospital setting 28 April to 29 May 2020 |

• Questionnaire using: • Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) • HAD scale • Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI). • COVID-19 Stressors Questionnaire • Desc. stats • Kendall’s Tau • Pearson’s correlation |

• Stressors that were associated with the postponement or cancellation of cancer treatment, changes in cancer care trajectory, and postponement of medical tests • 63.9% of participants experienced at least one stressor related to the COVID-19 pandemic (one: 27.8%, two: 22.2%, three: 11.1%) • Higher levels of concerns related to the experienced stressors were significantly correlated with higher levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, insomnia, and fear of cancer recurrence • A higher number of stressors experienced was significantly associated with greater levels of anxiety, depression and insomnia, but not fear of recurrence |

|

Merz et al. (2020) Italy Breast |

To assess how breast cancer survivors perceived electronic medical record–assisted telephone follow-up |

Survivors Prospective N = 137 34–89 years old |

Primary data: survey Web-based 9 March and 2 June 2020 |

• Online survey •Desc. stats • Pearson’s test • Fisher’s exact test • Mann–Whitney U test • χ2tests |

• 80.3% were satisfied with E-TFU compared to a standard FU visit • 89.8% were satisfied with the duration of the phone call • 43.8% would like to have electronic medical record assisted telephone follow-up in the future • Nearly 64% suffered from COVID-19–related anxiety about their health • Low educational level was correlated with higher COVID-19–related anxiety |

|

Miaskowski et al. (2020) USA Multiple |

To evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, levels of social isolation and loneliness, and the occurrence and severity of common symptoms between oncology patients with low vs. high levels of COVID-19 and cancer-related stress |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 187 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data; survey Web-based 27 May to 10 July, 2020 |

• Online survey using: • Karnofsky Performance Status scale • Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) • IES-R scale • Perceived Stress Scale • Connor Davidson Resilience Scale • COST scale • The Los Angeles Loneliness Scale • Social Isolation Scale •CES-D scale • Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories • General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) • Lee Fatigue Scale • Attentional Function Index • Brief pain inventory •Desc. stats • t-tests • χ2 tests • Mann–Whitney U tests |

• 31.6% were categorized in the Stressed group (score of > 24) • Perceived the Stressed group’s Impact score equates with probable PTSD • Stressed group, patients reported occurrence for depression (71.2%), anxiety (78.0%), sleep disturbance (78.0%), evening fatigue (55.9%), cognitive impairment (91.5%), and pain (75.9%) • The stressed group had lower score for financial toxicity (greater financial concerns) |

|

Mitra et al. (2020) India Multiple |

To study the challenges faced by cancer patients in India during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 36 ≥ 18 years |

Primary data: survey Web-based 1 to 15 May 2020 |

• Online questionnaire • Self-grading anxiety levels and the reason for their anxiety • Desc. stats |

• 94.4% reported lack of peer group support services and psychological counselling sessions • 41.7% reported problems with slot availability for teleconsultation, while 33% had network issues • 22% reported deferral of radiotherapy dates and long waiting hours beyond appointment time • 88.9% reported delay of advice of the nutritionist • 13.8% deferral of survey, 19.5% of tumour board deferral • 76.6% reported restrictions • 91.7% reported an increase in anxiety • 8.3% reported their anxiety remained the same • 91.7% feared infection with COVID-19 was the reason for increased anxiety • 86% reported fear of disease progression increased anxiety • 55.6% reported treatment not being optimum as the reason for their increased anxiety • 27.8% reported increased anxiety due to fear of death • 22.2% reported fear of losing jobs and financial crisis for the family members as the cause of their increased anxiety |

|

Ng. K et al. (2020) Singapore Not specified |

1. To evaluate the psychological effects of COVID-19 on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers (HCWs) 2. To evaluate the prevalence of burnout among HCWs |

Patients and caregivers Cross-sectional N = 624 patients (408 care givers, 421 HCWs) > 21 years old |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting 6 to 22 April 2020 |

•Questionnaire survey using: • GAD-7 scale • Self-reported fears related to COVID-19 • Maslach Burnout Inventory • Desc. stats • χ2 tests • Logistic regression |

• 66% of patients reported a high level of fear from COVID-19 • The greatest concern of patients was the wide community spread of COVID-19 • 19.1% of patients had anxiety (score ≥ 10) • Fear was the most common emotion, followed by anxiety • Anxiety was significantly higher in patients married, education lower than tertiary level • Patients that were non-Chinese and married had a higher level of COVID-19 fears |

|

Papautsky and Hamlish (2021) USA Breast |

1. To examine the impact of COVID-19 on health-related worry of breast cancer survivors (worry associated with: delays in cancer care, risk to general health, and risk of COVID-19) 2. To examine the role of the relationship with their cancer care team (trust, communication, planning) in models of vulnerability and worry |

Survivors Cross-sectional N = 633 Adults |

Primary data: questionnaire Web-based 2 April to 14 May 2020 |

•Questionnaire • Desc. stats • Pearson correlations • T-tests •ANCOVAs |

• Patients in active treatment, immunocompromised, and experiencing delays treatment were more worried about their cancer • Trust negatively correlated with worry • Significant positive correlations between communication and trust and negative correlations between trust and cancer-related worry |

|

Parikh et al. (2020) USA Breast |

To perform a cost analysis on the transitions to telemedicine in a radiation oncology department |

Payer and patient Descriptive study N = 1 patient NA |

Primary data: interviews and surveys of personnel Hospital setting Using a patient undergoing 28-fraction treatment course, exact timeframe not specified |

• Process maps were created for traditional in-person and telemedicine-based workflow processes • Interviews with personnel to obtain time spent and resource • Costs from the department’s financial officer • Time-driven activity-based costing |

• Majority of consultations, follow-up visits, and on-treatment visits were converted to telemedicine •Telemedicine reduced provider costs $586 compared with traditional workflow • Patients saved $170 per treatment course |

|

Philip et al. (2020) UK Lung |

To identify and explore the concerns of people with long-term respiratory conditions in the UK regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and how these concerns were affecting them |

Patients Qualitative N = 7039, 42 lung cancer patients NA |

Secondary data: online survey Web-based 1st to 8th of April 2020 |

• Data from an online survey by the Asthma UK and British Lung Foundation (AUK-BLF) •Thematic analysis |

• Four key themes were identified, which were concerns about (1) vulnerability to COVID-19 (most dominant theme), (2) anticipated experience of contracting COVID-19, (3) pervasive uncertainty, (4) inadequate national response 2. Mental health impacts: anxiety and fear |

|

Pigozzi et al. (2021) Italy Multiple |

To evaluate the psychological status of patients before and during the pandemic |

Patient Prospective N = 474 20–97 years old |

Primary data: survey Secondary: medical records Web-based 27 April to 7 June 2020 |

•Questionnaire using: •Emotional Vulnerability Index (EVI) •Desc. stats • χ2 tests |

•Chemotherapy patients reported high vulnerability • Breast cancer patients felt the most vulnerable (56%) • Prostate cancer and stomach cancer patients felt the least vulnerable. Only 28% of prostate cancer patients and 27% stomach cancer patients Pre-emergency period: • Low level of emotional distress • 39% were not able to cope with their cancers During pandemic period: • 216 (47%) reported they remained the feeling of low vulnerability • 41 (9%) increased vulnerability • 10 (2%) decreased vulnerability • 196 (42%) remained feeling of high vulnerability • 90% of respondents reported strong family support •Higher vulnerability was found in females and age ≤ 65 years old |

|

Rajan et al. (2021) India Not specified |

1. To assess the impact of COVID-19 on cancer healthcare from the patient perspective 2. Analyse any adverse effects of the pandemic |

Patient Cross‐sectional N = 310 patients > 18 years old |

Primary data: questionnaire Hospital setting 19 June to 7 August 2020 |

• Questionnaire •Desc. stats •Binary logistic regression |

• Access to care had a statistically significant difference of (34.23 ± 15.38) p < 0.001 • Education below a secondary school level and illiterate patients had more problems in healthcare access • 21% of patients were denied treatment • Anxiety domain had a statistically significant impact score of (24.95 ± 14.01), p < 0.001 • 62% had anxiety • Married participants had greater levels of anxiety • Depression domain had a statistically significant impact score of (31.24 ± 19.79), p < 0.001 • Two-thirds of patients had felt their life has become meaningless, and they could not experience a positive feeling in life • 81% of patients felt sad and helpless • Stress domain had the least effect with a score of (20.54 ± 13.53), p < 0.001 • Those earning INR < 35 K annually had more stress and depression •25% of patients suffered from insomnia • Financial status had the greatest statistically significant impact score of (59.68 ± 16.52), p < 0.001 •52% of patients experienced financial difficulties reporting a loss of their family earnings • Married participants had greater levels of financial impact • 45% of patients could not arrange finances and social support from their relatives or friends • 81% of participants do not have treatment covered under any government health scheme or insurance • Those earning INR < 35 K had less financial impact than those earning more as they were supported by government funds for their cancer treatment • Age 31–50 years, males, married, daily wagers, having a senior secondary level of education, and income of INR 35 K–100 K were most financially impacted • COVID-19 had the greatest impact on those with income INR < 35 K and 35 K–100 K, married, rural residence |

|

Shinan-Altman et al. (2020) Israel Breast |

To explore factors associated with health services utilization among breast cancer patients during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 151 patients > 18 years old |

Primary data: survey Hospital setting April 5 to April 12, 2020 |

Online survey: • Anxiety The Brief Symptom Inventory • Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support • Susceptibility to COVID-19 5-point Likert-type scale • Sense of mastery 7-point Likert scale • Desc. stats •Logistic regression •Pearson correlations |

• 31% reported cancelling a health services appointment due to the COVID-19 outbreak • 30% of the participants cancelled an appointment to the oncology or haematology clinic because of the COVID-19 outbreak. Reasons were fear to contract the virus (93%), forgetfulness (4%), and lack of urgency (3%) • Contact with healthcare professionals was rated low on questionnaire • Perceived health status of half of the participants was moderate, and 35% of the participants had other additional diseases • The mean score of perceived susceptibility was moderate, while the mean score for anxiety was relatively low. Sense of mastery and social support were relatively high • Patients with perceived bad to reasonable health status, a lower sense of mastery, and higher anxiety had more contact with healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic • Participants who did not cancel an appointment to the oncology or haematology clinic during the COVID-19 outbreak perceived their health status as being bad to reasonable and had a higher sense of mastery and higher levels of social support • Participants who cancelled an appointment to the oncology or haematology clinic during the COVID-19 outbreak had higher perceived susceptibility and higher anxiety levels. Statistical decrease was found with being in contact with HC professional • About half of the participants reported being in isolation since the COVID-19 outbreak |

|

Sigorski et al. (2020) Poland Multiple |

1. To assess the relationship between the level of cancer-related anxiety (CRA) and SARS-CoV-2-related anxiety (SRA) among patients with cancer receiving anticancer systemic therapy 2. To distinguish subgroups of patients with the highest levels of anxiety and to assess strategy of coping with cancer |

Patient Prospective, observational N = 306 > 18 years old |

Primary data; survey Hospital setting 11 and 15 May 2020 |

•Questionnaire using: • Fear of COVID-19 Scale (SRA-FCV-19S) •Numerical Anxiety Scale (SRA-NAS) • Desc. stats |

• Patients with breast cancer and treated with curative intention, as these factors are associated with a higher level of anxiety • The mean level of Fear of COVID was 18.5 (SD = 7.44), which was correlated with the Anxiety of COVID (r = 0.741, p < 0.001) • Fear of COVID was tumour type dependent • Anxiety observed in patients with breast cancer (17.63 ± 8.75) • Patients under 65 years old were associated with higher levels of anxiety • Anxiety related to cancer was higher in females |

|

Singh et al. (2020) India Not specified |

To assess the concerns and coping strategies and perspectives of patients suspected with COVID-19 at the National Cancer Institute |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 103 Adults |

Primary data: questionnaire Web-based April to May 2020 |

• Online questionnaire • Desc. stats |

• 27% were COVID-19 asymptomatic • 33% of participants responded that they did need counselling • 55.3% were worried • 43% were anxious • 33% were sad • 46.6% were mostly comfortable • 14% were not stressed at all • 12% felt that their life had become difficult during the quarantine Coping mechanisms: • 80.6% reported support from family and friends • 71% remained connected to family and friends • 70% used spirituality/prayer • 45% used music therapy • 57% maintained a daily routine as a coping strategy • 2% were unable to cope |

|

Souza et al. (2020) Brazil Breast |

To understand the experience of cancer patients coping with COVID-19 |

Patient Qualitative participatory action N = 12 ≥ 18 years old |

Primary data: virtual discussion Hospital setting June 2020 |

• Virtual culture circle • Thematic analysis |

Two themes: 1. Challenges: cancer and COVID-19-Fear of infection, difficulty completing treatment, afraid to leave quarantine for treatment, anxious and concern for their health, stress, sadness 2. Learning: rising from one’s own ashes—Made them stronger, more united family, more time with family, faith, hope, opportunity to grow |

|

Vanni et al. (2020) Italy Breast |

To estimate the impact of anxiety among patients, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Retrospective N = 160 39–80 years old |

Primary data: interview Secondary data: medical notes Hospital setting 16th of January to the 20th of March 2020 |

• Medical notes • Interviewed via telephone • Literature review •Desc. stats • T-test • Fisher’s exact test |

• Both POSTCOVID-19-Suspicious Breast Lesion and POST-COVID-19-Breast Cancer groups showed higher rates of procedure refusal and surgical refusal • Risk of COVID-19 Infection risk was the primary reason for refusal • Risk factors for surgical refusal include higher age at diagnosis, female gender, ethnicity, type of insurance, LABC (stage II and III BC), non-triple-negative breast cancer, residence areas with a low percentage of high school diplomas |

|

Wang, Y. et al. (2020) China Not specified |

To explore mental health problems in patients diagnosed with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 6213 Adults |

Primary data: interview Secondary data: electronic medical records Hospital setting 9 to 19 April 2020 |

• Interview using: • Visual Analogue Scale • WHOQOL-BRIEF scale • DSMIV-Insomnia Criteria •GAD-7 scale • PHQ-9 scale • Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) • IES-R scale • Desc. stats • Linear regression |

• 1.6% of patients were seeking help for psychological counselling • 48.1% did not pay attention to online mental health services • 11.2% considered online mental health services as helpful • Digestive system cancer and breast cancer showed a higher proportion of having mental health problems • 23.4% had depression • 17.7% had anxiety • 9.3% had PTSD •13.5% had hostility • Risk factors across different mental health problems, having a history of mental disorder, excessive alcohol consumption, having a higher frequency of worrying about cancer management due to COVID-19, feelings of overwhelming psychological pressure from COVID-19, high level of fatigue and pain • Inconvenience to go out for follow-up treatment was associated with higher risk of depression • Longer time since diagnosis, higher frequency of receiving COVID-19 information and news were associated with a higher level of PTSD symptoms • Females had a higher frequency of worrying about disease management due to COVID-19, increasing psychological pressure caused by COVID-19, and lower sleep quality • Younger age, male sex, being employed, longer time since diagnosis, receiving treatment, higher frequency of receiving COVID-19 information and news, satisfaction with personal health, good sleep quality, and having good relationships with friends were associated with lower risk of anxiety • Having been employed, longer time since diagnosis, and good sleep quality were associated with lower levels of depression • Younger age was a protective factor against hostility • Male sex, good sleep quality, and good relationships with friends were associated with lower levels of PTSD symptoms |

|

Yan et al. (2020) USA Head and neck |

1. Examine the impact of COVID-19 on head and neck cancer patients and advocacy organisations 2. Changes in patient concerns 3. Changes in HNC advocacy group programmes 3. Challenges faced |

Patient and providers Qualitative N = 4 organisations for cancer patients NA |

Primary data: interviews Organisation advocacy group Not specified |

• Semi-structured interviews via phone and email • Thematic analysis |

• Increased number of phone calls, emails, and messages on social media platforms contacting these organizations • Increased volume of calls involving COVID-19-related concerns Patient concerns: • Accessibility and/or delay of treatment • Risk of COVID-19 • Impact on cancer care • Inability to proceed with care alongside family members • Patients often may feel more isolated • Financial burden: worries about affording treatment and transportation to medical facilities |

|

Yang, G. et al. (2020) China Multiple |

To explore the effect of adverse childhood experience (ACE) on suicide ideation in young cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic |

Patient Observational and cross-sectional N = 197 18–40 years old |

Primary data; questionnaire Hospital setting January to May 2020 |

•Questionnaire using: • The self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) • The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) • The Beck Suicide Ideation Scale (BSI) • A blood biochemical examination to estimate inflammatory condition (CRP levels) •Desc. stats • Pearson correlation •Bootstrap analysis |

• Young cancer patients demonstrated high levels of anxiety symptoms and suicide ideation, and low sleep quality, during the COVID-19 pandemic • Sleep quality, anxiety symptoms, and CRP levels affect suicidal ideation • ACE directly affected suicide ideation in young cancer patients • ACE affected suicide ideation directly and was mediated by roles sleep quality, anxiety symptom and CRP • ACE significantly and positively affected anxiety symptoms, CRP, and suicide ideation, but significantly affected sleep quality negatively • Anxiety symptoms significantly affected CRP levels and suicide ideation positively but significantly and negatively affected sleep quality • Sleep quality significantly and negatively affected suicide ideation, while CRP levels significantly and positively affected suicide ideation |

|

Yang S. et al. (2020) China Lymphoma |

1. To examine the impact of disrupted cancer care on anxiety and HRQoL of patients 2. Evaluate caregiver support and an online education programme of the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 2532 subjects (1060 patients, 948 caregivers, and 524 members of the general public) > 20 years old |

Primary data: questionnaire Web-based 17 to 19 April 2020 |

• Online questionnaire using: • Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) • EORTC QLQ-C30 instrument •Desc. stats • T-test • ANOVA • χ2 tests • The Kendall tau-b correlation • Linear regression |

• 56% of patients changed their routine hospital • 9% changed to a therapy of lower intensity • 4% switched to oral anti-lymphoma drugs • 13% delayed scheduled parenteral therapy • 37% delayed or postponed scheduled hospital visits • 24% experienced reduced therapy intensity including fewer drugs, reduced drug doses, a switch from parenteral to oral drugs, and/or therapy delay or discontinuation • 52% reported no change of their medical activities including physician visits, exams, and/or therapy • 33% if lymphoma patients had anxiety • Incidence of anxiety higher in lymphoma patients and their caregivers compared to members of the general public • More than 77% of respondents had minimal/moderate anxiety • Female sex, receiving therapy, reduced therapy intensity, and hospitalised patients were associated with more anxiety • Reduced therapy intensity was associated with worse HRQoL • Those who scored caregiver support and the online patient education programme high had better HRQoL • Paradoxically, lymphoma patients during the pandemic had better HRQoL than pre-pandemic controls • 39% were concerned about treatment disruption • 50% of patients were concerned about COVID-19 infection risk • Females were associated with more anxiety • Higher education level was associated with less anxiety • Social support resources for lymphoma patients included online patient support/discussion groups. Subjects who rated the quality of these online tools high had a better HRQoL |

|

Yildirim et al. (2021) Turkey Multiple |

1. To analyse anxiety and depression amongst cancer patients 2. To investigate the correlation between treatment delays and depression and anxiety levels in cancer patients |

Patient Cross-sectional N = 637 first survey N = 595 s survey 18–76 years old |

Primary data: questionnaire; secondary: medical notes Hospital setting Pre-pandemic survey from 3 to 22 February, 2020. Pandemic survey from 14 March to 5 July 2020 |

•Questionnaire • Medical records •Telephone interview/face to face using: • The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) • The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) •Desc. stats • Kolmogorov–Smirnov test • T-test • Mann–Whitney U test • ANOVA • Pearson’s correlation |

• Depression and anxiety levels in cancer patients were found to increase during the pandemic • The increase was positively correlated with the disruption of their treatment (p = 0.000, r = 0.81) • Depression and anxiety levels and treatment delays were higher in elderly patients •Depression and anxiety levels were found to be significantly higher in females • Treatment delays were more common in patients who had to use public transportation • Elderly patients preferred to postpone their appointments for a while and stay home • Marital status, education level, social support, comorbidities, ECOG status, and stage of cancer were insignificant |

|

Zuliani et al. (2020) Italy Not specified |

To analyse how organisational changes related to SARSCoV-2 have impacted: (i) Volumes of oncological activity (compared to the same period in 2019), (ii) Hospital admissions of “active” oncological patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection |

NA Retrospective N = 1 institution, N = 241 outpatients surveyed NA |

Secondary data: health records Primary data: questionnaire Hospital setting 1 January to 31 March 2020 and 2019 |

• Medical records • Questionnaire on patient acceptance of measures • Desc. stats • T-test |

Hospital admissions: • Jan–March 2020: reduced by 8% • Average weekly admissions showed a 40% reduction in March 2020 Chemotherapy admissions: • Jan–March 2020: reduced by 6% • 14% reduction in daily average Specialist visits: • Jan–March 2020: reduced by 3%. 35% reduction daily average visits, 7 patients were COVID positive • Almost all patients felt that the organisational measures adopted to minimise the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection were clearly expressed (98%, 95%) • Acceptance of phone-based follow-ups and restaging visits, which were perceived as “not very adequate” (17%) or “not adequate at all” (18%) • Fear of accessing hospital facilities 34% • Fear that chemotherapy treatment could increase the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection 27% |

Results

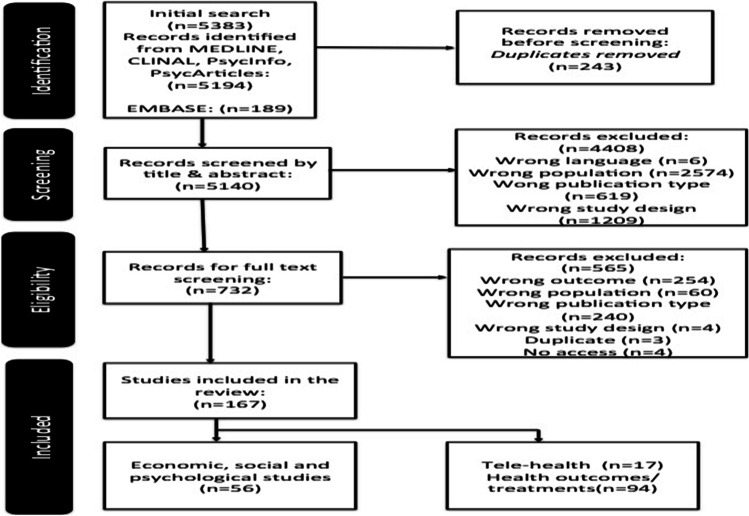

In total 5383 references were imported into Rayyan, and 243 duplicates were removed. A total of 5140 records were screened by title and abstract by reviewers in two pairs (AL and AM; AK and FJD) and independently assessed against the inclusion criteria. In sum, 732 studies were identified for full-text review; 167 were considered for inclusion of which 56 report on the economic, social, and psychological impacts of COVID-19 [6] (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of search output and results

Of these, 96% were single-country studies, predominately from the USA (20%), Italy (18%), India (11%), and China (11%). The remainder were from elsewhere in Europe (19%), Middle East (11%), Asia (4%), Brazil (4%), or Canada (2%). Most studies included patients with multiple cancer types (64%). Others focus on specific cancer sites: breast (18%), gynaecological (5%), head and neck (3.6%), lung (3.6%), thyroid (1.8%), colorectal (1.8%), or lymphoma (1.8%).

Social and psychological impacts of COVID-19 on cancer patients

Worry and fear

The most common mental health domain(s) identified were worry and/or fear around their cancer and getting COVID-19. Firstly, there was a heightened sense of fear of cancer recurrence or disease progression due to COVID-19-related disruptions or delays in cancer care [7–14]. Instruments used to measure fear and the level of fear experienced varied. For example, in a survey of 16 European countries, 71% of patients were concerned about cancer progression if their treatment/follow-up was cancelled/postponed [8]. In contrast, a survey in India reported fear of treatment delays and cancer progression as mostly moderate or minimal [10].

Secondly, there was fear and worry around getting COVID-19 amongst cancer patients [7–9, 11–13, 15–35]. A Singaporean study reported that 66% of patients had an elevated level fear of COVID-19 [36]. Gheorghe et al. [37] found that 68.5% of Romanian cancer patients were “very” or “somewhat worried” about COVID-19 compared to the influenza virus. Biagioli et al. [38] found that 37.3% of Italian cancer patients were “very or extremely” afraid of going to hospital because of an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 there, and 24.5% were “very or completely” afraid that their cancer care would become less important than being protected against COVID-19 infection, which would then have a negative impact on their prognosis. They also found that 53.8% believed they were at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection than the general population. Similarly, Erdem and Karaman [39] report that one-third of Turkish cancer patients were afraid to leave their house. These were more likely to be > 65 years, female, with stage 1 cancer, and with low education attainment. Those that did attend hospital appointments (~ 33%) were more likely to have stage 4 cancer; wore a mask (67%); and preferred not to use public transport owing to COVID-19 risk (95%). The majority (97%) did not accept visitors to their houses and washed their hands more often than usual (97.3%). Those finished treatment (radiotherapy or surgery) with co-morbidities (40%) were also afraid of COVID-19, in particular, females [7]. Higher levels of worry were found among females and older patients in Italy [16, 30], patients with comorbidities, immunocompromised and on active treatment in Denmark, the USA, and China [24, 28, 33], and amongst those with higher stress levels in Iran [40].

Patients tended to prioritise their cancer care over fear of contracting COVID-19, suggesting they were more afraid of delayed treatment and cancer progression than COVID-19 [10]. However, some sub-groups were willing to postpone/delay appointments and treatments [16, 21, 32].

Worryingly, as much as 61.8% were found to fear both COVID-19 infection and cancer progression equally [37]. In practice, the two fears/worries are intertwined, with patients reporting fear of getting COVID-19 infection when in hospital for treatment [11] and fearing that chemotherapy treatment could increase risk of COVID-19 infection (27% of Italian cancer patients sampled [41]). Disparity also existed amongst those who worried more about COVID-19 infection than their cancer, low socioeconomic groups [37], those undergoing palliative care [42], older [8, 16], frailer patients with co-morbidities [16], or those with a good understanding of immunosuppression [10].

Distress, anxiety, and depression